Shawn Phillips from Rochester was looking for how to write in japanese on word mac

Mickey Thomas found the answer to a search query how to write in japanese on word mac

write my essay

how to write in japanese on word mac

how to write in japanese on word on a mac

how to write in japanese on wordpad

how to write in japanese on your computer

how to write in japanese on your iphone

how to write in japanese online

how to write in japanese symbols

how to write in japanese translate into english

how to write in japanese using english keyboard

how to write in japanese writing

how to write in japaneses

how to write in japaneset

how to write in japanesse

how to write in japanesw

how to write in japanise

how to write in japenes

how to write in japenese

how to write in japenesse

how to write in japenise

how to write in japense

how to write in japinese

how to write in japnese

how to write in java

how to write in javascript

how to write in javasribed

how to write in journal

how to write in journal format

how to write in kana

how to write in kanji

how to write in kanji characters

how to write in kanji japanese

how to write in kannada

how to write in kannada in ms word

how to write in kannada language in facebook

how to write in katakana

how to write in katakana in word

how to write in katakana on google translate

how to write in katakana on iphone

how to write in keyboard

how to write in khmer

how to write in khmer on facebook

how to write in khmer unicode

how to write in korea

how to write in korean

how to write in korean on computer

how to write in korean using english keyboard

how to write in kryptonian

how to write in kurdish

how to write in kurdish language

how to write in l33t

thesis help online

dissertation writing help

expository essay topics

do my homework

how to write an overview of a topic

how to write good case studies

journeyman roofer resume

how to write a winning college scholarship essay

latex term paper template

how to cite title of book in essay apa

how to write up a factor analysis

how to write an abap alv

Writing system

Writing system in Japanese

Let’s learn the writing system in Japanese !

- 3 writing systems

- Punctuations

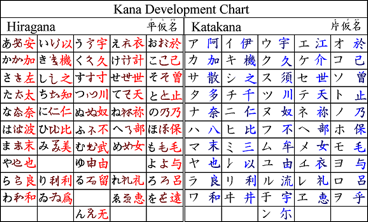

- Hiragana & katakana Chart

- Marks〝 and ゜

- Contracted sounds

- Double vowels / Double consonants

- Exception

3 writing systems

There are 3 types of writing systems in Japanese. They are called «Hiragana«, «Katakana«, and «Kanji«. Around the 5th century, Japanese people started to use Chinese characters «Kanji» to represent Japanese language. Then, around the 9th century, they simplified shapes of certain Kanji and created «Hiragana» and «Katakana» which are phonetic letters (indicating just the sounds).

Today, Japanese writing consists of these 3 kind of characters.

私 は ビールを 飲みました。

I drank a beer.

漢 Kanji

— Each kanji represents a meaning and has several different pronunciations.

— They are used for nouns, adjectives, verbs etc.

— The number of commonly used kanji in Japan is about 2000 ! Japanese children learn about 1000 kanji in primary school and another 1000 kanji in junior high school.

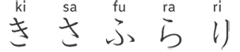

あ ア Hiragana / Katakana

— Hiragana and katakana writings are phonetic letters (indicating just the sounds). Therefore, learning hiragana and katakana means learning Japanese pronunciation as well.

— There are 46 letters of hiragana and 46 letters of katakana, both representing the same 46 sounds. That means, each sound can be written in 2 ways (hiragana and katakana).

— Katakana is mainly used for words with foreign origins.

A Rōmaji

There is an official way to transcribe Japanese sounds into the Roman alphabet (English alphabet) which is called Rōmaji. You can read all Japanese sentences on this site without having to learn the Japanese writing system, because all the Japanese sentences are transcribed in Rōmaji !

In Noriko’s Japanese Lessons, you learn hiragana, katakana, and rōmaji.

You can learn hiragana and katakana at the same time. If it’s too much, you can start with hiragana first, which is used more frequently.

Learning Hiragana is highly recommended because the verb conjugation is closely connected to the Hiragana chart. Knowing Hiragana will really help you when you learn verb conjugation !

At the beginning, the Japanese writing system may seem complicated to English speakers. But actually, it doesn’t take a long time to memorize 92 letters (46 hiragana and 46 katakana). On the other hand, remember that there is no «irregular spelling» in Japanese words. Once you master the 92 letters, you can write words just as how you pronounce them. Simple !

Don’t give up !

Punctuations

Punctuation

、 equivalent to comma , : It’s called «ten» and is used for the pause in a sentence.

あした、べんきょうします。

Tomorrow, I study.

。 equivalent to period . : It’s called «maru» and is used to mark the end of a sentence.

「」 equivalent to quotation marks » « : It’s called «kagi kakko» and is used to quote.

「いいですよ」と いいました。

I said «Alright».

( ) equivalent to parentheses ( ) : It’s called «kakko» and is used to add information.

とうきょう (にほんのしゅと)

Tokyo (Capital of Japan)

? ! aren’t used in formal Japanese writing. However, they could be used in

casual writing.

Space

In Japanese sentences, there is no space between words. But on this site, the space is

sometimes inserted between words in order to see the sentence structure more clearly.

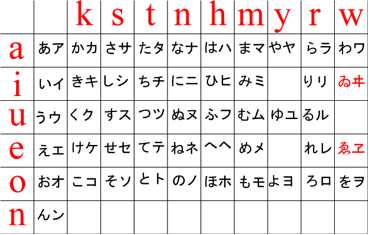

There are 5 vowels in Japanese. Basic 46 Hiragana / Katakana chart shows the 5 vowels and 41 combination of consonants and vowel sounds. Click on letters to listen to the sounds.

How do I to write hiragana and katakana?

Click on the link below to download the worksheets. These sheets will help you learn the proper stroking and the formation of each character. Let’s practice !

The following hiragana letters look different depending on the font being used. The examples are shown below. On this site, I only use the font, Handwriting style, because it most accurately represents the authentic handwriting of Japanese letters. Please use the font on this website (and my hiragana chart) as a model.

The font used on this website.

Please use this font as a model.

Some fonts show certain hiragana

letters this way.

Let’s transcribe these words in rōmaji.

Let’s transcribe these words in hiragana.

Let’s transcribe these words in katakana.

Marks and ゜

and ゜

〝

When you add the mark〝 (called «ten ten») to consonants K, S, T, H, they become G, Z, D, B.

゜

The mark ゜(called «maru») can only be added to H.

When the «maru» is added, the H becomes P.

These marks should be added on the upper right corner of each letter.

» ji » and » zu «

You have 2 choices of letters describing the sounds «ji» and «zu». For the sound, «ji», the letter じ is most often used and ぢ is used in some exceptional cases. For the sound «zu», the letter ず is most often used and づ is used in some exceptional cases.

Let’s transcribe these words in rōmaji.

Let’s transcribe these words in hiragana.

Let’s transcribe these words in katakana.

Contracted sounds

When one of the 3 letters, や(ya), ゆ(yu), よ(yo) is written small after «i» vowel letters (see below)…

They become contracted sounds.

They are pronounced as if you are pronouncing these two letters at the same time:

e.g: きゃ Try to pronounce «ki» and «ya» at the same time…! → kya

e.g: しゅ Try to pronounce «shi» and «yu» at the same time…! → shu

e.g: ちょ Try to pronounce «chi» and «yo» at the same time…! → cho

Let’s transcribe these words in rōmaji.

Let’s transcribe these words in hiragana.

Let’s transcribe these words in katakana.

Double vowels / Double consonants

Double vowels

In Japanese, there are double vowels (long vowels) and single vowels (short vowels). Double vowels are transcribed as follows:

In Rōmaji

Put a straight line mark ( ‾ ) on top of double vowels.

pronounced as «teeburu»

pronounced as «ruuru»

In Hiragana

Add a double sound vowel letter.

for double vowel «O», add う instead of お.

In Katakana

Put a straight line to transcribe the second vowel.

The distinction between double vowels and single vowels is very important because double or single vowels make a completely different word !

Double consonants

To transcribe the double consonant sound ( kk, tt, ss, pp, etc), write a small つ right before the letter of which the consonant should be doubled.This つ is not pronounced, but indicates that the following consonant is doubled. This rule applies to both hiragana and katakana.

Let’s transcribe these words in rōmaji.

Let’s transcribe these words in hiragana.

Let’s transcribe these words in katakana.

Exception

Exceptional use of hiragana for certain particles

Case 1

To transcribe the particle of subject/topic «wa», the letter は is used. In this case, は is exceptionally pronounced as «wa».

わたし は

せんせい

です

I am a teacher.

Case 2

To transcribe the particle of destination «e», the letter へ is used. In this case, へ is exceptionally pronounced as «e».

わたし は

にほんへ

いきます

I go to Japan.

Case 3

The letter を is used exclusively as the particle of the direct object. You can’t use お in this case even though the pronunciation is the same.

わたし は

パンを

たべます

I eat bread.

Other exceptional pronunciations

To transcribe foreign sounds which do not exist in Japanese, we write these vowel combinations in small letters in katakana. In rōmaji, these foreign sounds are written as follows in parentheses.

Let’s practice some more !

Let’s transcribe these words in rōmaji.

Let’s transcribe these words in hiragana.

Let’s transcribe these words in katakana.

How did you do on the Japanese writing system ?

Take your time to master them. It’s worth it !

Writing might be one of the most difficult, but also fun, parts of learning Japanese. The Japanese don’t use an alphabet. Instead, there are three types of scripts in Japanese: kanji, hiragana and katakana. The combination of all three is used for writing.

Roughly speaking, kanji represents blocks of meaning (nouns, stems of adjectives and verbs). Kanji was brought over from China around 500 C.E. and thus are based on the style of written Chinese characters at that time. The pronunciation of kanji became a mixture of Japanese readings and Chinese readings. Some words are pronounced like the original Chinese reading.

For those more familiar with Japanese, you might realize that kanji characters do not sound like their modern-day Chinese counterparts. This is because kanji pronunciation is not based on modern-day Chinese language, but the ancient Chinese spoken around 500 C.E.

In terms of pronouncing kanji, ththere are two different methods: on-reading and kun-reading. On-reading (On-yomi) is the Chinese reading of a kanji character. It is based on the sound of the kanji character as pronounced by the Chinese at the time the character was introduced, and also from the area it was imported. Kun-reading (Kun-yomi) is the native Japanese reading associated with the meaning of the word. For a clearer distinction and an explanation of how to decide between on-reading and kun-reading, read what is On-reading and Kun-reading?

Learning kanji can be intimidating as there are thousands of unique characters. Start building your vocabulary by learning the top 100 most common kanji characters used in Japanese newspapers. Being able to recognize frequently used characters in newspapers is a good introduction to practical words used every day.

Hiragana

The other two scripts, hiragana and katakana, are both kana systems in Japanese. Kana system is a syllabic phonetic system similar to the alphabet. For both scripts, each character typically corresponds with one syllable. This is unlike kanji script, in which one character can be pronounced with more than one syllable.

Hiragana characters are used to express the grammatical relationship between words. Thus, hiragana is used as sentence particles and to inflect adjectives and verbs. Hiragana is also used to convey native Japanese words that do not have a kanji counterpart, or it is used as a simplified version of a complex kanji character. In order to emphasize style and tone in literature, hiragana can take the place of kanji in order to convey a more casual tone. Additionally, hiragana is used as a pronunciation guide to kanji characters. This reading aid system is called furigana.

There are 46 characters in hiragana syllabary, consisting of 5 singular vowels, 40 consonant-vowel unions and 1 singular consonant.

The curvy script of hiragana comes from the cursive style of Chinese calligraphy popular at the time when hiragana was first introduced to Japan. At first, hiragana was looked down upon by educated elites in Japan who continued to used only kanji. Consequently, hiragana first became popular in Japan among women as women were not granted the high levels of education available to men. Because of this history, hiragana is also referred to as onnade, or «women’s writing».

For tips on how to properly write hiragana, follow these stroke-by-stroke guides.

Katakana

Like hiragana, katakana is a form of Japanese syllabary. Developed in 800 C.E. during the Heian period, katakana consists of 48 characters including 5 nucleus vowels, 42 core syllabograms and 1 coda consonant.

Katakana is used transliterate foreign names, the names of foreign places and loan words of foreign origin. While kanji are borrowed words from ancient Chinese, katakana is used to transliterate modern-day Chinese words. This Japanese script is also used for onomatopoeia, the technical scientific name of animals and plants. Like italics or boldface in Western languages, katakana is used to create emphasis in a sentence.

In literature, katakana script can replace kanji or hiragana in order to emphasize a character’s accent. For instance, if a foreigner or, like in manga, a robot is speaking in Japanese, their speech is often written in katakana.

Now that you know what katakana is used for, you can learn how to write katakana script with these numbered stroke guides.

General Tips

If you want to learn Japanese writing, start with hiragana and katakana. Once you are comfortable with those two scripts, then you can begin to learn kanji. Hiragana and katakana are simpler than kanji, and have only 46 characters each. It is possible to write an entire Japanese sentence in hiragana. Many children’s books are written in hiragana only, and Japanese children start to read and write in hiragana before making an attempt to learn some of the two thousand kanji commonly used.

Like most Asian languages, Japanese can be written vertically or horizontally. Read more about when one should write vertically versus horizontally.

Do you want to learn how to write in Japanese, but feel confused or intimidated by the script?

This post will break it all down for you, in a step-by-step guide to reading and writing skills this beautiful language.

I remember when I first started learning Japanese and how daunting the writing system seemed. I even wondered whether I could get away without learning the script altogether and just sticking with romaji (writing Japanese with the roman letters).

I’m glad I didn’t.

If you’re serious about learning Japanese, you have to get to grips with the script sooner or later. If you don’t, you won’t be able to read or write anything useful, and that’s no way to learn a language.

The good news is that it isn’t as hard as you think. And I’ve teamed up with my friend Luca Toma (who’s also a Japanese coach) to bring you this comprehensive guide to reading and writing Japanese.

By the way, if you want to learn Japanese fast and have fun while doing it, my top recommendation is Japanese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Japanese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Japanese naturally through story… not rules. It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

Don’t have time to read this now? Click here to download a free PDF of the article.

If you have a friend who’s learning Japanese, you might like to share it with them. Now, let’s get stuck in…

One Language, Two Systems, Three Scripts

If you are a complete beginner, Japanese writing may appear just like Chinese.

But if you look at it more carefully you’ll notice that it doesn’t just contain complex Chinese characters… there are lots of simpler ones too.

Take a look.

それでも、日本人の食生活も急速に変化してきています。ハンバーグやカレーライスは子供に人気がありますし、都会では、イタリア料理、東南アジア料理、多国籍料理などを出すエスニック料理店がどんどん増えています。

Nevertheless, the eating habits of Japanese people are also rapidly changing. Hamburgers and curry rice are popular with children. In cities, ethnic restaurants serving Italian cuisine, Southeast Asian cuisine and multi-national cuisine keep increasing more and more.

(Source: “Japan: Then and Now”, 2001, p. 62-63)

As you can see from this sample, within one Japanese text there are actually three different scripts intertwined. We’ve colour coded them to help you tell them apart.

(What’s really interesting is the different types of words – parts of speech – represented by each colour – it tells you a lot about what you use each of the three scripts for.)

Can you see the contrast between complex characters (orange) and simpler ones (blue and green)?

The complex characters are called kanji (漢字 lit. Chinese characters) and were borrowed from Chinese. They are what’s called a ‘logographic system’ in which each symbol corresponds to a block of meaning (食 ‘to eat’, 南 ‘south’, 国 ‘country’).

Each kanji also has its own pronunciation, which has to be learnt – you can’t “read” an unknown kanji like you could an unknown word in English.

Luckily, the other two sets of characters are simpler!

Those in blue above are called hiragana and those in green are called katakana. Katakana and hiragana are both examples of ‘syllabic systems’, and unlike the kanji, each character corresponds to single sound. For example, そ= so, れ= re; イ= i, タ = ta.

Hiragana and katakana are a godsend for Japanese learners because the pronunciation isn’t a problem. If you see it, you can say it!

So, at this point, you’re probably wondering:

“What’s the point of using three different types of script? How could that have come about?”

In fact, all these scripts have a very specific role to play in a piece of Japanese writing, and you’ll find that they all work together in harmony in representing the Japanese language in a written form.

So let’s check them out in more detail.

First up, the two syllabic systems: hiragana and katakana (known collectively as kana).

The ‘Kana’ – One Symbol, One Sound

Both hiragana and katakana have a fixed number of symbols: 46 characters in each, to be precise.

Each of these corresponds to a combination of the 5 Japanese vowels (a, i, u, e o) and the 9 consonants (k, s, t, n, h, m, y, r, w).

(Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Hiragana (the blue characters in our sample text) are recognizable for their roundish shape and you’ll find them being used for three functions in Japanese writing:

1. Particles (used to indicate the grammatical function of a word)

は wa topic marker

が ga subject marker

を wo direct object marker

2. To change the meaning of verbs, adverbs or adjectives, which generally have a root written in kanji. (“Inflectional endings”)

急速に kyuusoku ni rapidly

増えています fuete imasu are increasing

3. Native Japanese words not covered by the other two scripts

それでも soredemo nevertheless

どんどん dondon more and more

Katakana (the green characters in our sample text) are recognisable for their straight lines and sharp corners. They are generally reserved for:

1. Loanwords from other languages. See what you can spot!

ハンバーグ hanbaagu hamburger

カレーライス karee raisu curry rice

エスニック esunikku ethnic

2. Transcribing foreign names

イタリア itaria Italy

アジア ajia Asia

They are also used for emphasis (the equivalent of italics or underlining in English), and for scientific terms (plants, animals, minerals, etc.).

So where did hiragana and katakana come from?

In fact, they were both derived from kanji which had a particular pronunciation; Hiragana took from the Chinese cursive script (安 an →あ a), whereas katakana developed from single components of the regular Chinese script (阿 a →ア a ).

(Source: Wikipedia Commons)

So that covers the origins the two kana scripts in Japanese, and how we use them.

Now let’s get on to the fun stuff… kanji!

The Kanji – One Symbol, One Meaning

Kanji – the most formidable hurdle for learners of Japanese!

We said earlier that kanji is a logographic system, in which each symbol corresponds to a “block of meaning”.

食 eating

生 life, birth

活 vivid, lively

“Block of meaning” is the best phrase, because one kanji is not necessarily a “word” on its own.

You might have to combine one kanji with another in order to make an actual word, and also to express more complex concepts:

生 + 活 = 生活 lifestyle

食 + 生活 = 食生活 eating habits

If that sounds complicated, remember that you see the same principle in other languages.

Think about the word ‘telephone’ in English – you can break it down into two main components derived from Greek:

‘tele’ (far) + ‘phone’ (sound) = telephone

Neither of them are words in their own right.

So there are lots and lots of kanji, but in order to make more sense of them we can start by categorising them.

There are several categories of kanji, starting with the ‘pictographs’ (象形文字shōkei moji), which look like the objects they represent:

(Source: Wikipedia Commons)

In fact, there aren’t too many of these pictographs.

Around 90% of the kanji in fact come from six other categories, in which several basic elements (called ‘radicals’) are combined to form new concepts.

For example:

人 (‘man’ as a radical) + 木 (‘tree’) = 休 (‘to rest’)

These are known as 形声文字 keisei moji or ‘radical-phonetic compounds’.

You can think of these characters as being made up of two parts:

- A radical that tells you what category of word it is: animals, plants, metals, etc.)

- A second component that completes the character and give it its pronunciation (a sort of Japanese approximation from Chinese).

So that’s the story behind the kanji, but what are they used for in Japanese writing?

Typically, they are used to represent concrete concepts.

When you look at a piece of Japanese writing, you’ll see kanji being used for nouns, and in the stem of verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

Here are some of them from our sample text at the start of the article:

日本人 Japanese people

多国籍料理 multinational cuisine

東南 Southeast

Now, here’s the big question!

Once you’ve learnt to read or write a kanji, how do you pronounce it?

If you took the character from the original Chinese, it would usually only have one pronunciation.

However, by the time these characters leave China and reach Japan, they usually have two or sometimes even more pronunciations.

Aggh! 🙂

How or why does this happen?

Let’s look at an example.

To say ‘mountain’, the Chinese use the pictograph 山 which depicts a mountain with three peaks. The pronunciation of this character in Chinese is shān (in the first tone).

Now, in Japanese the word for ‘mountain’ is ‘yama’.

So in this case, the Japanese decided to borrow the character山from Chinese, but to pronounce it differently: yama.

However, this isn’t the end of the story!

The Japanese did decide to borrow the pronunciation from the original Chinese, but only to use it when that character is used in compound words.

So, in this case, when the character 山 is part of a compound word, it is pronounced as san/zan – clearly an approximation to the original Chinese pronunciation.

Here’s the kanji on its own:

山は… Yama wa… The mountain….

And here’s the kanji when it appears in compound words:

火山は… Kazan wa The volcano…

富士山は… Fujisan wa… Mount Fuji….

To recap, every kanji has at least two pronunciations.

The first one (the so-called訓読み kun’yomi or ‘meaning reading’) has an original Japanese pronunciation, and is used with one kanji on it’s own.

The second one (called音読み on’yomi or ‘sound-based reading’) is used in compound words, and comes from the original Chinese.

Makes sense, right? 😉

In Japan, there’s an official number of kanji that are classified for “daily use” (常用漢字joyō kanji) by the Japanese Ministry of Education – currently 2,136.

(Although remember that the number of actual words that you can form using these characters is much higher.)

So now… if you wanted to actually learn all these kanji, how should you go about it?

To answer this question, Luca’s going to give us an insight into how he did it.

How I Learnt Kanji

I started to learn kanji more than 10 years ago at a time when you couldn’t find all the great resources that are available nowadays. I only had paper kanji dictionary and simple lists from my textbook.

What I did have, however, was the memory of a fantastic teacher.

I studied Chinese for two years in college, and this teacher taught us characters in two helpful ways:

- He would analyse them in terms of their radicals and other components

- He kept us motivated and interested in the process by using fascinating stories based on etymology (the origin of the characters)

Once I’d learnt to recognise the 214 radicals which make up all characters – the building blocks of Chinese characters – it was then much easier to go on and learn the characters and the words themselves.

It’s back to the earlier analogy of dividing the word ‘telephone’ into tele and phone.

But here’s the thing – knowing the characters alone isn’t enough. There are too many, and they’re all very similar to one another.

If you want to get really good at the language, and really know how to read and how to write in Japanese, you need a higher-order strategy.

The number one strategy that I used to reach a near-native ability in reading and writing in Japanese was to learn the kanji within the context of dialogues or other texts.

I never studied them as individual characters or words.

Now, I could give you a few dozen ninja tricks for how to learn Japanese kanji. But the one secret that blows everything else out of the water and guarantees real success in the long-term, is extensive reading and massive exposure.

This is the foundation of the StoryLearning® method, where you immerse yourself in language through story.

In the meantime, there are a lot of resources both online and offline to learn kanji, each of which is based on a particular method or approach (from flashcards to mnemonic and so on).

The decision of which approach to use can be made easier by understanding the way you learn best.

Do you have a photographic memory or prefer working with images? Do you prefer to listen to audio? Or perhaps you prefer to write things by hands?

You can and should try more than one method, in order to figure out which works best for you.

(Note: You should get a copy of this excellent guide by John Fotheringham, which has all the resources you’ll ever need to learn kanji)

Summary Of How To Write In Japanese

So you’ve made it to the end!

See – I told you it wasn’t that bad! Let’s recap what we’ve covered.

Ordinary written Japanese employs a mixture of three scripts:

- Kanji, or Chinese characters, of which there are officially 2,136 in daily use (more in practice)

- 2 syllabic alphabets called hiragana and katakana, containing 42 symbols each

In special cases, such as children’s books or simplified materials for language learners, you might find everything written using only hiragana or katakana.

But apart from those materials, everything in Japanese is written by employing the three scripts together. And it’s the kanji which represent the cultural and linguistic challenge in the Japanese language.

If you want to become proficient in Japanese you have to learn all three!

Although it seems like a daunting task, remember that there are many people before you who have found themselves right at the beginning of their journey in learning Japanese.

And every journey begins with a single step.

So what are you waiting for?

The best place to start is to enrol in Japanese Uncovered. The course includes a series of lessons that teach you hiragana, katakana and kanji. It also includes an exciting Japanese story which comes in different formats (romaji, hiragana, kana and kanji) so you can practice reading Japanese, no matter what level you’re at right now.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

– – –

It’s been a pleasure for me to work on this article with Luca Toma, and I’ve learnt a lot in the process.

Now he didn’t ask me to write this, but if you’re serious about learning Japanese, you should consider hiring Luca as a coach. The reasons are many, and you can find out more on his website: JapaneseCoaching.it

– – –

Do you know anyone learning Japanese? Why not send them this article, or click here to send a tweet.

This article is about the modern writing system and its history. For an overview of the entire language, see Japanese language. For the use of Latin letters to write Japanese, see Romanization of Japanese.

| Japanese | |

|---|---|

Japanese novel using kanji kana majiri bun (text with both kanji and kana), the most general orthography for modern Japanese. Ruby characters (or furigana) are also used for kanji words (in modern publications these would generally be omitted for well-known kanji). The text is in the traditional tategaki («vertical writing») style; it is read down the columns and from right to left, like traditional Chinese. Published in 1908. |

|

| Script type |

mixed logographic (kanji), syllabic (hiragana and katakana) |

|

Time period |

4th century AD to present |

| Direction | When written vertically, Japanese text is written from top to bottom, with multiple columns of text progressing from right to left. When written horizontally, text is almost always written left to right, with multiple rows progressing downward, as in standard English text. In the early to mid-1900s, there were infrequent cases of horizontal text being written right to left, but that style is very rarely seen in modern Japanese writing.[citation needed] |

| Languages | Japanese language Ryukyuan languages |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(See kanji and kana)

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Jpan (413), Japanese (alias for Han + Hiragana + Katakana) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode range |

U+4E00–U+9FBF Kanji U+3040–U+309F Hiragana U+30A0–U+30FF Katakana |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated currently in use.[1][2]

Several thousand kanji characters are in regular use, which mostly originate from traditional Chinese characters. Others made in Japan are referred to as “Japanese kanji” (和製漢字, wasei kanji; also known as “country’s kanji” 国字, kokuji). Each character has an intrinsic meaning (or range of meanings), and most have more than one pronunciation, the choice of which depends on context. Japanese primary and secondary school students are required to learn 2,136 jōyō kanji as of 2010.[3] The total number of kanji is well over 50,000, though few if any native speakers know anywhere near this number.[4]

In modern Japanese, the hiragana and katakana syllabaries each contain 46 basic characters, or 71 including diacritics. With one or two minor exceptions, each different sound in the Japanese language (that is, each different syllable, strictly each mora) corresponds to one character in each syllabary. Unlike kanji, these characters intrinsically represent sounds only; they convey meaning only as part of words. Hiragana and katakana characters also originally derive from Chinese characters, but they have been simplified and modified to such an extent that their origins are no longer visually obvious.

Texts without kanji are rare; most are either children’s books — since children tend to know few kanji at an early age — or early electronics such as computers, phones, and video games, which could not display complex graphemes like kanji due to both graphical and computational limitations.[5]

To a lesser extent, modern written Japanese also uses initialisms from the Latin alphabet, for example in terms such as «BC/AD», «a.m./p.m.», «FBI», and «CD». Romanized Japanese is most frequently used by foreign students of Japanese who have not yet mastered kana, and by native speakers for computer input.

Use of scripts[edit]

Kanji[edit]

Kanji (漢字) are logographic characters (based on traditional ones) taken from Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese.

It is known from archaeological evidence that the first contacts that the Japanese had with Chinese writing took place in the 1st century AD, during the late Yayoi period. However, the Japanese people of that era probably had little to no comprehension of the script, and they would remain relatively illiterate until the 5th century AD in the Kofun period, when writing in Japan became more widespread.

They are used to write most content words of native Japanese or (historically) Chinese origin, which include the following:

- many nouns, such as 川 (kawa, «river») and 学校 (gakkō, «school»)

- the stems of most verbs and adjectives, such as 見 in 見る (miru, «see») and 白 in 白い (shiroi, «white»)

- the stems of many adverbs, such as 速 in 速く (hayaku, «quickly») and 上手 as in 上手に (jōzu ni, «masterfully»)

- most Japanese personal names and place names, such as 田中 (Tanaka) and 東京 (Tōkyō). (Certain names may be written in hiragana or katakana, or some combination of these, plus kanji.)

Some Japanese words are written with different kanji depending on the specific usage of the word—for instance, the word naosu (to fix, or to cure) is written 治す when it refers to curing a person, and 直す when it refers to fixing an object.

Most kanji have more than one possible pronunciation (or «reading»), and some common kanji have many. These are broadly divided into on’yomi, which are readings that approximate to a Chinese pronunciation of the character at the time it was adopted into Japanese, and kun’yomi, which are pronunciations of native Japanese words that correspond to the meaning of the kanji character. However, some kanji terms have pronunciations that correspond to neither the on’yomi nor the kun’yomi readings of the individual kanji within the term, such as 明日 (ashita, «tomorrow») and 大人 (otona, «adult»).

Unusual or nonstandard kanji readings may be glossed using furigana. Kanji compounds are sometimes given arbitrary readings for stylistic purposes. For example, in Natsume Sōseki’s short story The Fifth Night, the author uses 接続って for tsunagatte, the gerundive -te form of the verb tsunagaru («to connect»), which would usually be written as 繋がって or つながって. The word 接続, meaning «connection», is normally pronounced setsuzoku.

Kana[edit]

Hiragana[edit]

Hiragana (平仮名) emerged as a manual simplification via cursive script of the most phonetically widespread kanji among those who could read and write during the Heian period (794-1185). The main creators of the current hiragana were ladies of the Japanese imperial court, that used the script in the writing of personal communications and literature.

Hiragana is used to write the following:

- okurigana (送り仮名)—inflectional endings for adjectives and verbs—such as る in 見る (miru, «see») and い in 白い (shiroi, «white»), and respectively た and かった in their past tense inflections 見た (mita, «saw») and 白かった (shirokatta, «was white»).

- various function words, including most grammatical particles, or postpositions (joshi (助詞))—small, usually common words that, for example, mark sentence topics, subjects and objects or have a purpose similar to English prepositions such as «in», «to», «from», «by» and «for».

- miscellaneous other words of various grammatical types that lack a kanji rendition, or whose kanji is obscure, difficult to typeset, or considered too difficult to understand for the context (such as in children’s books).

- Furigana (振り仮名)—phonetic renderings of kanji placed above or beside the kanji character. Furigana may aid children or non-native speakers or clarify nonstandard, rare, or ambiguous readings, especially for words that use kanji not part of the jōyō kanji list.

There is also some flexibility for words with common kanji renditions to be instead written in hiragana, depending on the individual author’s preference (all Japanese words can be spelled out entirely in hiragana or katakana, even when they are normally written using kanji). Some words are colloquially written in hiragana and writing them in kanji might give them a more formal tone, while hiragana may impart a softer or more emotional feeling.[6] For example, the Japanese word kawaii, the Japanese equivalent of «cute», can be written entirely in hiragana as in かわいい, or with kanji as 可愛い.

Some lexical items that are normally written using kanji have become grammaticalized in certain contexts, where they are instead written in hiragana. For example, the root of the verb 見る (miru, «see») is normally written with the kanji 見 for the mi portion. However, when used as a supplementary verb as in 試してみる (tameshite miru) meaning «to try out», the whole verb is typically written in hiragana as みる, as we see also in 食べてみる (tabete miru, «try to eat [it] and see»).

Katakana[edit]

Katakana (片仮名) emerged around the 9th century, in the Heian period, when Buddhist monks created a syllabary derived from Chinese characters to simplify their reading, using portions of the characters as a kind of shorthand. The origin of the alphabet is attributed to the monk Kūkai.

Katakana is used to write the following:

- transliteration of foreign words and names, such as コンピュータ (konpyūta, «computer») and ロンドン (Rondon, «London»). However, some foreign borrowings that were naturalized may be rendered in hiragana, such as たばこ (tabako, «tobacco»), which comes from Portuguese. See also Transcription into Japanese.

- commonly used names of animals and plants, such as トカゲ (tokage, «lizard»), ネコ (neko, «cat») and バラ (bara, «rose»), and certain other technical and scientific terms, such as mineral names

- occasionally, the names of miscellaneous other objects whose kanji are rare, such as ローソク (rōsoku, «candle»)

- onomatopoeia, such as ワンワン (wan-wan, «woof-woof»), and other sound symbolism

- emphasis, much like italicisation in European languages.

Katakana can also be used to impart the idea that words are spoken in a foreign or otherwise unusual accent; for example, the speech of a robot.

Rōmaji[edit]

The first contact of the Japanese with the Latin alphabet occurred in the 16th century, during the Muromachi period, when they had contact with Portuguese navigators, the first European people to visit the Japanese islands. The earliest Japanese romanization system was based on Portuguese orthography. It was developed around 1548 by a Japanese Catholic named Anjirō.

The Latin alphabet is used to write the following:

- Latin-alphabet acronyms and initialisms, such as NATO or UFO

- Japanese personal names, corporate brands, and other words intended for international use (for example, on business cards, in passports, etc.)

- foreign names, words, and phrases, often in scholarly contexts

- foreign words deliberately rendered to impart a foreign flavour, for instance, in commercial contexts

- other Japanized words derived or originated from foreign languages, such as Jリーグ (jei rīgu, «J. League»), Tシャツ (tī shatsu, «T-shirt») or B級グルメ (bī-kyū gurume, «B-rank gourmet [cheap and local cuisines]»)

Arabic numerals[edit]

Arabic numerals (as opposed to traditional kanji numerals) are often used to write numbers in horizontal text, especially when numbering things rather than indicating a quantity, such as telephone numbers, serial numbers and addresses. Arabic numerals were introduced in Japan probably at the same time as the Latin alphabet, in the 16th century during the Muromachi period, the first contact being via Portuguese navigators. These numerals did not originate in Europe, as the Portuguese inherited them during the Arab occupation of the Iberian peninsula. See also Japanese numerals.

Hentaigana[edit]

Hentaigana (変体仮名), a set of archaic kana made obsolete by the Meiji reformation, are sometimes used to impart an archaic flavor, like in items of food (esp. soba).

Additional mechanisms[edit]

Jukujikun refers to instances in which words are written using kanji that reflect the meaning of the word though the pronunciation of the word is entirely unrelated to the usual pronunciations of the constituent kanji. Conversely, ateji refers to the employment of kanji that appear solely to represent the sound of the compound word but are, conceptually, utterly unrelated to the signification of the word.

Examples[edit]

Sentences are commonly written using a combination of all three Japanese scripts: kanji (in red), hiragana (in purple), and katakana (in orange), and in limited instances also include

Latin alphabet characters (in green) and Arabic numerals (in black):

Tシャツを3枚購入しました。

The same text can be transliterated to the Latin alphabet (rōmaji), although this will generally only be done for the convenience of foreign language speakers:

Tīshatsu o san—mai kōnyū shimashita.

Translated into English, this reads:

I bought 3 T-shirts.

All words in modern Japanese can be written using hiragana, katakana, and rōmaji, while only some have Kanji. Words that have no dedicated kanji may still be written with kanji by employing either ateji (like in man’yogana, から = 可良) or jukujikun, like in the title of とある科学の超電磁砲 (超電磁砲 being used to represent レールガン).

| Kanji | Hiragana | Katakana | Rōmaji | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 私 | わたし | ワタシ | watashi | I, me |

| 金魚 | きんぎょ | キンギョ | kingyo | goldfish |

| 煙草 or 莨 | たばこ | タバコ | tabako | tobacco, cigarette |

| 東京 | とうきょう | トーキョー | tōkyō | Tokyo, literally meaning «eastern capital» |

| none | です | デス | desu | is, am, to be (hiragana, of Japanese origin); death (katakana, of English origin) |

Although rare, there are some words that use all three scripts in the same word. An example of this is the term くノ一 (rōmaji: kunoichi), which uses a hiragana, a katakana, and a kanji character, in that order. It is said that if all three characters are put in the same kanji «square», they all combine to create the kanji 女 (woman/female). Another example is 消しゴム (rōmaji: keshigomu) which means «eraser», and uses a kanji, a hiragana, and two katakana characters, in that order.

Statistics[edit]

A statistical analysis of a corpus of the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun from the year 1993 (around 56.6 million tokens) revealed:[7]

|

|

Collation[edit]

Collation (word ordering) in Japanese is based on the kana, which express the pronunciation of the words, rather than the kanji. The kana may be ordered using two common orderings, the prevalent gojūon (fifty-sound) ordering, or the old-fashioned iroha ordering. Kanji dictionaries are usually collated using the radical system, though other systems, such as SKIP, also exist.

Direction of writing[edit]

Traditionally, Japanese is written in a format called tategaki (縦書き), which was inherited from traditional Chinese practice. In this format, the characters are written in columns going from top to bottom, with columns ordered from right to left. After reaching the bottom of each column, the reader continues at the top of the column to the left of the current one.

Modern Japanese also uses another writing format, called yokogaki (横書き). This writing format is horizontal and reads from left to right, as in English.

A book printed in tategaki opens with the spine of the book to the right, while a book printed in yokogaki opens with the spine to the left.

Spacing and punctuation[edit]

Japanese is normally written without spaces between words, and text is allowed to wrap from one line to the next without regard for word boundaries. This convention was originally modelled on Chinese writing, where spacing is superfluous because each character is essentially a word in itself (albeit compounds are common). However, in kana and mixed kana/kanji text, readers of Japanese must work out where word divisions lie based on an understanding of what makes sense. For example, あなたはお母さんにそっくりね。 must be mentally divided as あなた は お母さん に そっくり ね。 (Anata wa okaasan ni sokkuri ne, «You’re just like your mother»). In rōmaji, it may sometimes be ambiguous whether an item should be transliterated as two words or one. For example, 愛する, «to love», composed of 愛 (ai, «love») and する (suru, «to do», here a verb-forming suffix), is variously transliterated as aisuru or ai suru.

Words in potentially unfamiliar foreign compounds, normally transliterated in katakana, may be separated by a punctuation mark called a nakaguro (中黒, «middle dot») to aid Japanese readers. For example, ビル・ゲイツ (Bill Gates). This punctuation is also occasionally used to separate native Japanese words, especially in concatenations of kanji characters where there might otherwise be confusion or ambiguity about interpretation, and especially for the full names of people.

The Japanese full stop (。) and comma (、) are used for similar purposes to their English equivalents, though comma usage can be more fluid than is the case in English. The question mark (?) is not used in traditional or formal Japanese, but it may be used in informal writing, or in transcriptions of dialogue where it might not otherwise be clear that a statement was intoned as a question. The exclamation mark (!) is restricted to informal writing. Colons and semicolons are available but are not common in ordinary text. Quotation marks are written as 「 … 」, and nested quotation marks as 『 … 』. Several bracket styles and dashes are available.

History of the Japanese script[edit]

Importation of kanji[edit]

Japan’s first encounters with Chinese characters may have come as early as the 1st century AD with the King of Na gold seal, said to have been given by Emperor Guangwu of Han in AD 57 to a Japanese emissary.[8] However, it is unlikely that the Japanese became literate in Chinese writing any earlier than the 4th century AD.[8]

Initially Chinese characters were not used for writing Japanese, as literacy meant fluency in Classical Chinese, not the vernacular. Eventually a system called kanbun (漢文) developed, which, along with kanji and something very similar to Chinese grammar, employed diacritics to hint at the Japanese translation. The earliest written history of Japan, the Kojiki (古事記), compiled sometime before 712, was written in kanbun. Even today Japanese high schools and some junior high schools teach kanbun as part of the curriculum.

The development of man’yōgana[edit]

No full-fledged script for written Japanese existed until the development of man’yōgana (万葉仮名), which appropriated kanji for their phonetic value (derived from their Chinese readings) rather than their semantic value. Man’yōgana was initially used to record poetry, as in the Man’yōshū (万葉集), compiled sometime before 759, whence the writing system derives its name. Some scholars claim that man’yōgana originated from Baekje, but this hypothesis is denied by mainstream Japanese scholars.[9][10] The modern kana, namely hiragana and katakana, are simplifications and systemizations of man’yōgana.

Due to the large number of words and concepts entering Japan from China which had no native equivalent, many words entered Japanese directly, with a similar pronunciation to the original Chinese. This Chinese-derived reading is known as on’yomi (音読み), and this vocabulary as a whole is referred to as Sino-Japanese in English and kango (漢語) in Japanese. At the same time, native Japanese already had words corresponding to many borrowed kanji. Authors increasingly used kanji to represent these words. This Japanese-derived reading is known as kun’yomi (訓読み). A kanji may have none, one, or several on’yomi and kun’yomi. Okurigana are written after the initial kanji for verbs and adjectives to give inflection and to help disambiguate a particular kanji’s reading. The same character may be read several different ways depending on the word. For example, the character 行 is read i as the first syllable of iku (行く, «to go»), okona as the first three syllables of okonau (行う, «to carry out»), gyō in the compound word gyōretsu (行列, «line» or «procession»), kō in the word ginkō (銀行, «bank»), and an in the word andon (行灯, «lantern»).

Some linguists have compared the Japanese borrowing of Chinese-derived vocabulary as akin to the influx of Romance vocabulary into English during the Norman conquest of England. Like English, Japanese has many synonyms of differing origin, with words from both Chinese and native Japanese. Sino-Japanese is often considered more formal or literary, just as latinate words in English often mark a higher register.

Script reforms[edit]

Meiji period[edit]

The significant reforms of the 19th century Meiji era did not initially impact the Japanese writing system. However, the language itself was changing due to the increase in literacy resulting from education reforms, the massive influx of words (both borrowed from other languages or newly coined), and the ultimate success of movements such as the influential genbun itchi (言文一致) which resulted in Japanese being written in the colloquial form of the language instead of the wide range of historical and classical styles used previously. The difficulty of written Japanese was a topic of debate, with several proposals in the late 19th century that the number of kanji in use be limited. In addition, exposure to non-Japanese texts led to unsuccessful proposals that Japanese be written entirely in kana or rōmaji. This period saw Western-style punctuation marks introduced into Japanese writing.[11]

In 1900, the Education Ministry introduced three reforms aimed at improving the process of education in Japanese writing:

- standardization of hiragana, eliminating the range of hentaigana then in use;

- restriction of the number of kanji taught in elementary schools to about 1,200;

- reform of the irregular kana representation of the Sino-Japanese readings of kanji to make them conform with the pronunciation.

The first two of these were generally accepted, but the third was hotly contested, particularly by conservatives, to the extent that it was withdrawn in 1908.[12]

Pre–World War II[edit]

The partial failure of the 1900 reforms combined with the rise of nationalism in Japan effectively prevented further significant reform of the writing system. The period before World War II saw numerous proposals to restrict the number of kanji in use, and several newspapers voluntarily restricted their kanji usage and increased usage of furigana; however, there was no official endorsement of these, and indeed much opposition. However, one successful reform was the standardization of hiragana, which involved reducing the possibilities of writing down Japanese morae down to only one hiragana character per morae, which led to labeling all the other previously used hiragana as hentaigana and discarding them in daily use.[13]

Post–World War II[edit]

The period immediately following World War II saw a rapid and significant reform of the writing system. This was in part due to influence of the Occupation authorities, but to a significant extent was due to the removal of traditionalists from control of the educational system, which meant that previously stalled revisions could proceed. The major reforms were:

- gendai kanazukai (現代仮名遣い)—alignment of kana usage with modern pronunciation, replacing the old historical kana usage (1946);

- promulgation of various restricted sets of kanji:

- tōyō kanji (当用漢字) (1946), a collection of 1850 characters for use in schools, textbooks, etc.;

- kanji to be used in schools (1949);

- an additional collection of jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字), which, supplementing the tōyō kanji, could be used in personal names (1951);

- simplifications of various complex kanji letter-forms shinjitai (新字体).

At one stage, an advisor in the Occupation administration proposed a wholesale conversion to rōmaji, but it was not endorsed by other specialists and did not proceed.[14]

In addition, the practice of writing horizontally in a right-to-left direction was generally replaced by left-to-right writing. The right-to-left order was considered a special case of vertical writing, with columns one character high[clarification needed], rather than horizontal writing per se; it was used for single lines of text on signs, etc. (e.g., the station sign at Tokyo reads 駅京東).

The post-war reforms have mostly survived, although some of the restrictions have been relaxed. The replacement of the tōyō kanji in 1981 with the 1,945 jōyō kanji (常用漢字)—a modification of the tōyō kanji—was accompanied by a change from «restriction» to «recommendation», and in general the educational authorities have become less active in further script reform.[15]

In 2004, the jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字), maintained by the Ministry of Justice for use in personal names, was significantly enlarged. The jōyō kanji list was extended to 2,136 characters in 2010.

Romanization[edit]

There are a number of methods of rendering Japanese in Roman letters. The Hepburn method of romanization, designed for English speakers, is a de facto standard widely used inside and outside Japan. The Kunrei-shiki system has a better correspondence with Japanese phonology, which makes it easier for native speakers to learn. It is officially endorsed by the Ministry of Education and often used by non-native speakers who are learning Japanese as a second language.[citation needed] Other systems of romanization include Nihon-shiki, JSL, and Wāpuro rōmaji.

Lettering styles[edit]

- Shodō

- Edomoji

- Minchō

- East Asian sans-serif typeface

Variant writing systems[edit]

- Gyaru-moji

- Hentaigana

- Man’yōgana

See also[edit]

- Genkō yōshi (graph paper for writing Japanese)

- Iteration mark (Japanese duplication marks)

- Japanese typographic symbols (non-kana, non-kanji symbols)

- Japanese Braille

- Japanese language and computers

- Japanese manual syllabary

- Chinese writing system

- Okinawan writing system

- Kaidā glyphs (Yonaguni)

- Ainu language § Writing

- Siddhaṃ script (Indic alphabet used for Buddhist scriptures)

References[edit]

- ^ Serge P. Shohov (2004). Advances in Psychology Research. Nova Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-59033-958-9.

- ^ Kazuko Nakajima (2002). Learning Japanese in the Network Society. University of Calgary Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-55238-070-3.

- ^ «Japanese Kanji List». www.saiga-jp.com. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ «How many Kanji characters are there?». japanese.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ «How To Play (and comprehend!) Japanese Games». GBAtemp.net -> The Independent Video Game Community. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ^ Joseph F. Kess; Tadao Miyamoto (1 January 1999). The Japanese Mental Lexicon: Psycholinguistics Studies of Kana and Kanji Processing. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 90-272-2189-8.

- ^ Chikamatsu, Nobuko; Yokoyama, Shoichi; Nozaki, Hironari; Long, Eric; Fukuda, Sachio (2000). «A Japanese logographic character frequency list for cognitive science research». Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 32 (3): 482–500. doi:10.3758/BF03200819. PMID 11029823. S2CID 21633023.

- ^ a b Miyake (2003:8).

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2002). 韓国人の日本偽史―日本人はビックリ! (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-402716-7.

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2007). 韓vs日「偽史ワールド」 (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-387703-9.

- ^ Twine, 1991

- ^ Seeley, 1990

- ^ Hashi (25 January 2012). «Hentaigana: How Japanese Went from Illegible to Legible in 100 Years». Tofugu. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ^ Unger, 1996

- ^ Gottlieb, 1996

Sources[edit]

- Gottlieb, Nanette (1996). Kanji Politics: Language Policy and Japanese Script. Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7103-0512-5.

- Habein, Yaeko Sato (1984). The History of the Japanese Written Language. University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 0-86008-347-0.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo (2003). Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-30575-6.

- Seeley, Christopher (1984). «The Japanese Script since 1900». Visible Language. XVIII. 3: 267–302.

- Seeley, Christopher (1991). A History of Writing in Japan. University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2217-X.

- Twine, Nanette (1991). Language and the Modern State: The Reform of Written Japanese. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00990-1.

- Unger, J. Marshall (1996). Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan: Reading Between the Lines. OUP. ISBN 0-19-510166-9.

External links[edit]

- The Modern Japanese Writing System: an excerpt from Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan, by J. Marshall Unger.

- The 20th Century Japanese Writing System: Reform and Change by Christopher Seeley

- Japanese Hiragana Conversion API by NTT Resonant

- Japanese Morphological Analysis API by NTT Resonant

The Scripts

Japanese consists of two scripts (referred to as kana) called Hiragana and Katakana, which are two versions of the same set of sounds in the language. Hiragana and Katakana consist of a little less than 50 “letters”, which are actually simplified Chinese characters adopted to form a phonetic script.

Chinese characters, called Kanji in Japanese, are also heavily used in the Japanese writing. Most of the words in the Japanese written language are written in Kanji (nouns, verbs, adjectives). There exists over 40,000 Kanji where about 2,000 represent over 95% of characters actually used in written text. There are no spaces in Japanese so Kanji is necessary in distinguishing between separate words within a sentence. Kanji is also useful for discriminating between homophones, which occurs quite often given the limited number of distinct sounds in Japanese.

Hiragana is used mainly for grammatical purposes. We will see this as we learn about particles. Words with extremely difficult or rare Kanji, colloquial expressions, and onomatopoeias are also written in Hiragana. It’s also often used for beginning Japanese students and children in place of Kanji they don’t know.

While Katakana represents the same sounds as Hiragana, it is mainly used to represent newer words imported from western countries (since there are no Kanji associated with words based on the roman alphabet). The next three sections will cover Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji.

Intonation

As you will find out in the next section, every character in Hiragana (and the Katakana equivalent) corresponds to a [vowel] or [consonant + vowel] syllable sound with the single exception of the 「ん」 and 「ン」 characters (more on this later). This system of letter for each syllable sound makes pronunciation absolutely clear with no ambiguities. However, the simplicity of this system does not mean that pronunciation in Japanese is simple. In fact, the rigid structure of the fixed syllable sound in Japanese creates the challenge of learning proper intonation.

Intonation of high and low pitches is a crucial aspect of the spoken language. For example, homophones can have different pitches of low and high tones resulting in a slightly different sound despite sharing the same pronunciation. The biggest obstacle for obtaining proper and natural sounding speech is incorrect intonation. Many students often speak without paying attention to the correct enunciation of pitches making speech sound unnatural (the classic foreigner’s accent). It is not practical to memorize or attempt to logically create rules for pitches, especially since it can change depending on the context or the dialect. The only practical approach is to get the general sense of pitches by mimicking native Japanese speakers with careful listening and practice.

There are three types of writing systems in Japanese, and each one of them serves a specific purpose in a text.

This is one of the main reasons why the language is often touted as being one of the most notoriously difficult to master, especially when it comes to reading comprehension and written ability.

The complex list of characters can seem like a confusing blur of lines on a page, and this isn’t helped at all by the lack of spaces in written Japanese.

The three Japanese writing systems are called Kanji, Hiragana, and Katakana. While each of them uses very different characters, they are used together to form words and sentences.

While this might sound like a huge headache and a big obstacle to learning how to write in Japanese, each system is relatively straightforward to identify and can be easy to use once you know the rules.

The best Japanese tutors available

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.8 (2 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (9 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (25 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.8 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.8 (2 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (12 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.9 (9 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (25 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (11 reviews)

1st lesson free!

4.8 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

5 (6 reviews)

1st lesson free!

Let’s go

Origins of Japanese Writing Systems

Before take a look at the different types of Japanese writing, or scripts as they’re commonly known, we’re going to explore the origins of this peculiar writing tradition.

The history of the Japanese language and its writing systems is a bit of an enigma. With a written form that is so complex, it has proven difficult for linguists to pin down exactly how each script came about.

It’s one of the only languages of a major nation which has its roots shrouded in mystery, meaning there isn’t too much information about how it originally came to be.

There are many different theories and debates surrounding the history of the Japanese language, and these are divided up into the spoken and the written elements.

Many consider the modern form of Japanese writing as an adaptation from Chinese. This is because the Kanji script uses many ideographs or characters that are common in Chinese. This overlap is clearly recognisable to speakers of both Chinese and Japanese, but the origins of the other writing systems are less clear.

In fact, the first recorded examples of Japanese writing which date way back to the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. are of the Chinese language. That is to say, Chinese was written in Japan before a writing system was developed for the Japanese language. Over time, words were used to capture the nuance of the Japanese spoken word, and so the Chinese text evolved into a new one fit for the Japanese language.

Kanji can convey a lot of meaning, but the development of two other writing systems was necessary to express nuance in Japanese writing. Interestingly, Katakana was thought to have come about as a result of priests who would read Chinese texts, translate them into Japanese, and would need something to help them remember more readily.

The Hiragana writing system and the Katakana writing system fall under the label of ‘kana’, which means that they are both syllabic scripts. Curiously, while Hiragana works closely with the Kanji to form many parts of speech, Katakana is largely used for foreign borrowed words, onomatopoeia, and slang.

So to summarise, how exactly the Japanese writing systems came to be is still somewhat shrouded in mystery. However, what we do know is that the Kanji system was borrowed from Chinese, and the two kana systems were developed to fill in the gaps and capture the nuance of the Japanese language.

Japanese Kanji

The Kanji writing system in Japanese consists of characters which are borrowed from the Chinese language.

This script is made up of ideograms. Ideograms are characters which each have their own meaning, and can stand alone to represent an object, action, or concept.

As a result, if you were to only learn the Kanji in Japanese, you would still be able to understand and communicate effectively.

To mirror the fact that Kanji can have a complex meaning attached to them, each ideogram can be made up of anywhere from 2-20 strokes of the pen. This means that they will take more time to master than the kana, at least as far as memorising and writing them out goes.

It’s thought that if you know 3000 of the 45,000 or so Kanji, then you can understand the vast majority of common texts. Better still, if you just learn 100 or 200, you will be able to recognise about half of what you see in most newspapers and other everyday texts.

This is great to know, since it makes the daunting task of learning all the Kanji seem less intimidating. You can get by with just a couple hundred in the beginning, and this will serve you very well. This of course assumes that you are learning the most commonly used Kanji.

Common Uses for Kanji

Kanji are largely used to form the main parts of speech, which includes everything from nouns and verbs to adjectives and adverbs.

However, unlike in English, the Kanji often require assistance to form the words.

In many instances, the Kanji acts as the stem of the word, and the Hiragana acts as the ending.

This means you’ll need to learn the two scripts together to give yourself a real chance of solid Japanese reading comprehension and writing skills.

Japanese Hiragana

Hiragana is one of two syllabary scripts in Japanese, which together with katakana is grouped under the kana category of writing.

Unlike Kanji, the characters used in the Hiragana system of writing each correspond to a single sound or syllable, rather than an entire word or complete meaning.

While the Kanji script is responsible for the main parts of speech, the Hiragana script covers everything from suffixes to function words and particles.

There are 46 characters, with 5 vowels and 41 consonants. This will likely come as a relief to know, since there are far fewer characters than there are with the Kanji script.

It’s a good idea to think of the Hiragana script as the second most important writing system behind the Kanji.

As we touched upon earlier, if you know a few hundred Kanji, you can get by when it comes to basic reading and writing in Japanese.

If you add the most common Hiragana characters to that, then you will be well on your way to being able to communicate effectively.

Common Uses for Hiragana

The primary purpose of the Hiragana characters is as suffixes for Kanji stems.

This process, referred to in Japanese as Okurigana, accounts for the majority of instances where you will find Hiragana as you read Japanese texts.

If you find this hard to imagine, think of a verb in the present continuous, for example ‘watching’. In Japanese, the stem of the word ‘watch’ is covered by the Kanji stem, while the suffix ‘ing’ is covered by the Hiragana character.

While this may seem confusing at first, with a bit of practise you will start to recognise clearly when and how to use Hiragana in a sentence.

Japanese Katakana

The third writing system in Japanese is Katakana.

The katakana script is the least commonly used of the three, so you shouldn’t need to dedicate as much time to studying it as Kanji and Hiragana.

Nevertheless, Katakana is still very useful, and can be used to express foreign ideas and sounds.

Like Hiragana, the Katakana script is syllabary and is formed from characters that each take on a single sound like a vowel or consonant.

The characters are generally simple to write, as they often only require a few strokes at most.

There are 48 characters in total, with 5 vowels, 1 consonant, and 42 syllabograms.

A syllabogram is a sign you write for a syllable, and can be a mix of both vowels and consonants.

Common Uses for Katakana

The Katakana writing system is primarily used to refer to any words or concepts borrowed from a foreign language.

A good way to think of this is to imagine the words that would usually appear in italics in a text, as these will be the ones represented by Katakana. It is used sometimes in the same way we would use italics in a text too, that is to say to represent that something is important.

It is also used commonly for onomatopoeia, so it certainly has its place in creative writing and poetry. This is worth knowing if you plan on studying the popular Haiku, or writing your own short Japanese poems.

You will also find the Katakana used for scientific or technical terms, animals and plants, as well as slang and colloquialisms. Plus if you have ever visited Japan, you will surely have seen some written on billboards or advertisements, even if you didn’t recognise it at the time.

While these kinds of uses won’t be of interest to the beginner language-learner, later down the road they will be what helps distinguish good Japanese from great Japanese.

That means the sooner you familiarise yourself with them, the better. A good way to start is reading Japanese comics, as you’ll find plenty of onomatopoeia written in the Katakana script.

Are you learning Japanese and want to know how you can type in Japanese on your computer or smartphone? It’s easy to install a Japanese keyboard to type in hiragana, katakana and kanji. We will step you through this below and show you how to type in Japanese.

You’ll even learn some handy keyboard shortcuts and how to create kaomoji – like ╰(*´︶`*)╯♡, the text-face emoji that are popular with Japanese speakers.

We highly recommend you launch the notepad application on your phone or computer and try typing Japanese with us as we walk you through this article.

How to Install a Japanese Keyboard

To type in Japanese, the first thing you need is a Japanese keyboard. That does not mean you need to buy a real, physical Japanese keyboard with kana printed on it! Today’s computers and smartphones allow you to install a Japanese keyboard input method that lets you use your normal keyboard to ‘sound out’ the Japanese words and will convert these to hiragana, katakana and kanji for you.

In the sections below, you’ll find instructions for installing a Japanese keyboard on macOS and Windows 10, as well as iOS and Android smartphones.

If you were already done with the installation, you can skip it and go to the part “Typing in Japanese with Romaji”

Shortcuts for your device OS: macOS, Windows, iOS, Android

Install a Japanese Keyboard on Mac OS

Open System Preferences, and click on Language & Region.

In the Language & Region dialog, click on the plus + symbol underneath the Preferred languages list.

Scroll down until you see 日本語 - Japanese in the list, select it, then click Add.

You will see a prompt asking if you want to switch and use Japanese as your primary language. Select Use English for now.

You will be prompted to add an input source. Japanese is automatically selected and uses the built-in Mac OS Japanese language settings. Click Add Input Source.

If you want to tweak the settings or check which keyboard shortcuts you should use, select 日本語 - Japanese in the list of preferred languages, then click Keyboard Preferences.

The language input switcher is displayed by default in the menu bar at the top of your monitor.

Click on the input switcher A, then select one of the Japanese input options. Hiragana is the easiest to use and will automatically select kanji for words based on their context as you type.

How to switch input languages in Japanese quickly:

Instead of reaching for the mouse every time to switch input languages, you can use the keyboard shortcuts as indicated on the language input switcher menu. By default, the following shortcuts will be used.

Ctrl+Shift+;for romajiCtrl+Shift+Jfor hiraganaCtrl+Shift+Kfor katakana

(If you are wondering about the difference between hiragana and katakana, check this article.)

Install a Japanese Keyboard on Windows 10

Search for language settings in the Windows search field, and click on the top result – Language Settings in System Settings.

In the Language settings dialog, click on Add a preferred language.

Search for Japanese, select 日本語 - Japanese, then click Next.

Click Install, and then wait for Windows 10 to download and install the input method for Japanese.

To switch between your input methods/languages, press Windows + space, or use the language switcher in the system tray.

Install a Japanese Keyboard on an Apple Smartphone or Tablet

Open iOS Settings, tap on General, then on Keyboards.

Tap on Add New Keyboard, then on Japanese (you may need to scroll in the lower list to find it). Select either or both Kana or Romaji, and tap on Done<.

Now, you can switch between keyboard languages using the globe icon whenever you are entering text. Tap and hold the globe icon to bring up a list of input languages, then select which one you want to use.

Install a Japanese Keyboard on an Android Smartphone

First, download Google Japanese Input to your phone.

Click on Enable in settings, choose Google Japanese Input. If you want, select Google Japanese Input as the default input method in the Language & input settings.

Choose your theme then click on Get Started.

Now, you can switch between Japanese and English using the あ/a icon whenever you enter text. Slide your finger to the kana.

If you are more familiar with a standard romaji keyboard layout, switch to QWERTY mode in the Keyboard Layout settings.

Typing in Japanese with Romaji

Now you are ready to start typing in Japanese. Since you are typing Japanese using an English keyboard, you need to know the romaji (pronunciation) of each character in order to type it.

In fact, many Japanese people use romaji to type in Japanese too, even though they have hiragana printed on their keyboards. Becoming familiar with romaji is essential.

Type Japanese Hiragana Using Romaji

Romaji is a literal spelling or romanization of how you would pronounce the various Japanese kana. Most Japanese language input methods on both computers and smart devices accept both the Hepburn system (below) and the Kunreishiki system.

| あ | か | さ | た | な | は | ま | や | ら | わ | ん |

| a | ka | sa | ta | na | ha | ma | ya | ra | wa | nn |

| い | き | し | ち | に | ひ | み | り | |||

| i | ki | shi | chi | ni | hi | mi | ri | |||

| う | く | す | つ | ぬ | ふ | む | ゆ | る | ||

| u | ku | su | tsu | nu | fu | mu | yu | ru | ||

| え | け | せ | て | ね | へ | め | れ | |||

| e | ke | se | te | ne | he | me | re | |||

| お | こ | そ | と | の | ほ | も | よ | ろ | を | |

| o | ko | so | to | no | ho | mo | yo | ro | wo |

How to type the Japanese character ん

Be careful when typing a word with ん in it, especially when it is followed by another n- character. For example, you need to enter three n’s or minnna to type the word everything in Japanese – みんな, or onnna to type the word for woman – おんな。

To type long vowels in katakana, use a -. For example, ha-to will convert to ハート.

Typing Japanese: Contractions Using Romaji

Typing contractions works in much the same way – type how they are pronounced and the input method will automatically format the smaller characters.

| きゃ | しゃ | ちゃ | にゃ | ひゃ | みゃ | りゃ |

| kya | sha | cha | nya | hya | mya | rya |

| きゅ | しゅ | ちゅ | にゅ | ひゅ | みゅ | りゅ |

| kyu | shu | chu | nyu | hyu | myu | ryu |

| きょ | しょ | ちょ | にょ | ひょ | みょ | りょ |

| kyo | sho | cho | nyo | hyo | myo | ryo |

Form the long contractions simply by adding a u at the end. For example, kyuu will type きゅう, and nyou will type にょう.

Typing Japanese: Dakuten and Dakuten Contractions