Subjects>Jobs & Education>Education

Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

Best Answer

Copy

日本語

Pronounced- Nihongo (Nee-hon-go)

Wiki User

∙ 11y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: How do you write the word Japanese in Japanese characters?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

- sci.lang.japan FAQ

- 5. Japanese and English

- Next: Where does the word yen come from?

|

| Barber’s sign: English «thank you cut» has been transformed into «3 (san) Q» |

|---|

この内容を日本語で

Japanese usually writes words borrowed from foreign languages in

katakana. Katakana is phonetic, so a katakana transcription of an

English word is based on how the word sounds, not how it is

spelt. This page discusses ways to search for katakana versions of

English words, and the rules for katakana transcription.

The first place to look for a Japanese version of an English word is a

dictionary, to find the usual katakana equivalent. If the word is not

in the dictionary, try to find a Japanese person to help you. Other

tricks are explained in How can I find the Japanese name of a film, person, plant, etc.?

How a word appears as katakana depends on how the word is heard by

native speakers. Japanese has fewer different sounds than English, and

it does not have many ending consonants, so words tend to gain extra

vowels. For example, the English word «cat» becomes katakana

キャット (kyatto) with an extra «o» at the end, and «dog»

becomes ドッグ (doggu) with an extra «u» at the end.

Rules for conversion

Vowels and diphthongs are usually changed into the nearest

equivalent Japanese vowel. Japanese has fewer vowels than English, so

the two different vowels in «fur» and «far» both get turned into

Japanese ファー.

Plural words often become singular, thus «pajamas» becomes

pajama (パジャマ), and «slippers» becomes

suripaa (スリパー). Here the katakana パ used to

represent the first vowel of «pajamas» is based on the spelling of the

word.

Words with existing gairaigo forms usually keep that form. For

example, «black coffee» becomes burakku kōhii (ブラックコーヒー),

even though kōhii (コーヒー) for coffee originally comes from Dutch (see

Which Japanese words come from Dutch?).

Japanese has tended to favour British pronunciations, with words like

«vitamin», becoming a British-sounding bitamin (ビタミン)

rather than American-sounding baitamin (バイタミン). The vowels

used in Japanese are usually taken from the British pronunciation

rather than the American.

The following table outlines the rules for transcribing English

sounds. The English sounds are represented in International Phonetic

Alphabet (IPA) form.

| English sound (IPA) | Japanese | Examples | Japanese transcription Capitals indicate small kana |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short vowels | |||

| ɪ | イ, i | pit | ピット (pitto) |

| ɛ | エ, e | pet | ペット (petto) |

| æ | ア, a | ham | ハム (hamu) |

| æ after k | キャ, kya | cap | キャップ (kyappu) |

| ʌ | ア, a | mug | マグ (magu) |

| ʌ spelt with an «o» | オ, o (sometimes) | monkey, front, London | モンキー, フロント, ロンドン (monkii, furonto, rondon) |

| ɒ | オ, o | socks | ソックス (sokkusu) |

| ʊ | ウ, u | book | ブック (bukku) |

| Schwa (weak vowel) | |||

| non-final ə | not fixed, based on spelling. | about, pilot, London | アバウト, パイロット, ロンドン (abauto, pairotto, rondon) |

| final position ə | aa | carrier, hamburger | キャリアー, ハンバーガー (kyariā, hambāgā) |

| Long vowels | |||

| ɑː | アー, ア aa, a | car | カー (kā) |

| iː | イー: ii | shield | シールド (shiirudo) |

| ɔː | オー: oo | horse | ホース (hōsu) |

| oa | オア: door | ドア (doa) | |

| ɜː | アー: aa | bird | バード (bādo) |

| uː | ウー ū | shoe | シュー (shū) |

| juː | ュウ yū, see What is yōon? | cube | キューブ (kyūbu) |

| Diphthongs | |||

| eɪ | エイ, ei | day | デイ (dei) |

| aɪ | アイ, ai | my | マイ (mai) |

| ɔɪ | オーイ, ōi | boy | ボーイ (bōi) |

| オイ, oi | toy | トイ (toi) | |

| əʊ | オ, o | phone | フォン (fon) |

| オー, ō | no | ノー (nō) | |

| aʊ | アウ, au | now | ナウ (nau) |

| ɪə | イア, ia | pierce | ピアス (piasu) |

| ɛə | エア, ea | hair | ヘア (hea) |

| ʊə | ウアー, uaa | tour | ツアー (tsuā) |

| Consonants | |||

| θ | シャ, シ, シュ, シェ, ショ s | think | シンク (shinku) |

| ð | z | the | ザ (za) |

| r | ラ, リ, ル, レ, ロ: r-kana | right | ライト (raito) |

| l | ラ, リ, ル, レ, ロ: r-kana | link | リンク (rinku) |

| ŋ spelt «ng» | ンガ, ンギ ng | singer | シンガー (shingā) |

| ン, n (occasionally) | Washington, surfing | ワシントン, サーフィン (washinton, sāfin) | |

| ŋ spelt «nk» or «nc» | n | sink | シンク (shinku) |

| v | b | love | ラブ (rabu) |

| ヴァ, ヴィ, ヴ, ヴェ, ヴォ: v, written as ヴ (the u katakana) plus a small vowel | visual | ヴィジュアル (vijuaru) | |

| Consonants taking small vowel kana | |||

| w | ウィ: u + small vowel kana | win | ウィン (win) |

| f | ファ, フィ, フ, フェ, フォ: hu + small vowel kana | fight | ファイト (faito) |

| Special consonant and vowel combinations | |||

| ti, di | ティ, ディ (te or de + small i) (newer method) | Disney | ディズニー (dizunii) |

| chi, ji (older method) | |||

| tu | トゥ: to + small u (newer method) | Tourette’s syndrome | トゥレットシンドローム (turettoshindorōmu) |

| ツ: tsu | two | ツー (tsū) | |

| Consonant clusters | |||

| dz | ッズ zzu | goods, kids | グッズ, キッズ (guzzu, kizzu) |

Conversions based on spelling, and other oddities

|

| Label from a children’s toy «funky monkey buggy» |

|---|

Although most of the conversion from an English word into Japanese is

based on the pronunciation, in several cases the pronunciation is

based on spelling. In particular the schwa sound, the «uh» at the end

of «doctor», has no near equivalent in Japanese and so is often

transcribed depending on the spelling of the vowel. Other cases where

spelling takes precedence include the ʌ vowel, the «u» in

«cup» and «hut», which is usually a, but when spelt with an o

becomes o. For example «monkey» is monkii rather than

mankii. Japanese also lengthens n sounds, such as

Anna (アンナ) for the English name Anna, when they are spelt

with two ns.

In some cases, a mis-reading of a word survives into Japanese. For

example, the woodworking tool «router», which should have become

rautā, is known as a rūtā, based on the

spelling.

Japanese tends to shorten three-mora constructions ending in

syllabic n (ん) into two moras. For example «stainless steel» becomes

sutenresu (ステンレス) rather than suteinresu (ステインレス).

Transcription of names

In the case of people’s names, Japanese tends to transcribe into

near-equivalent versions not based on the pronunciation. For example,

the English name Sarah is often transcribed into Sara (サラ)

rather than Sērā (セーラー). For example American politician

Sarah Palin is known as Sara Peirin (サラ・ペイリン) in

Japan. Naomi is transcribed into Naomi (ナオミ), a common

Japanese female name with a similar romanized spelling but different

pronunciation, rather than Nēomi, a much closer representation of

the pronunciation. For example British model Naomi Campbell is known

as Naomi Kyamberu (ナオミ・キャンベル) in Japan. Similarly,

Thomas is transcribed as Tōmasu using a long first vowel, and

even more extremely, Paul may be transcribed into Paoro.

- sci.lang.japan FAQ

- 5. Japanese and English

- Next: Where does the word yen come from?

Copyright © 1994-2022 Ben Bullock

If you have questions, corrections, or comments, please contact

Ben Bullock

or use the discussion forum / Privacy policy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Book reviews |

Convert |

Handwritten |

Stroke order |

Convert |

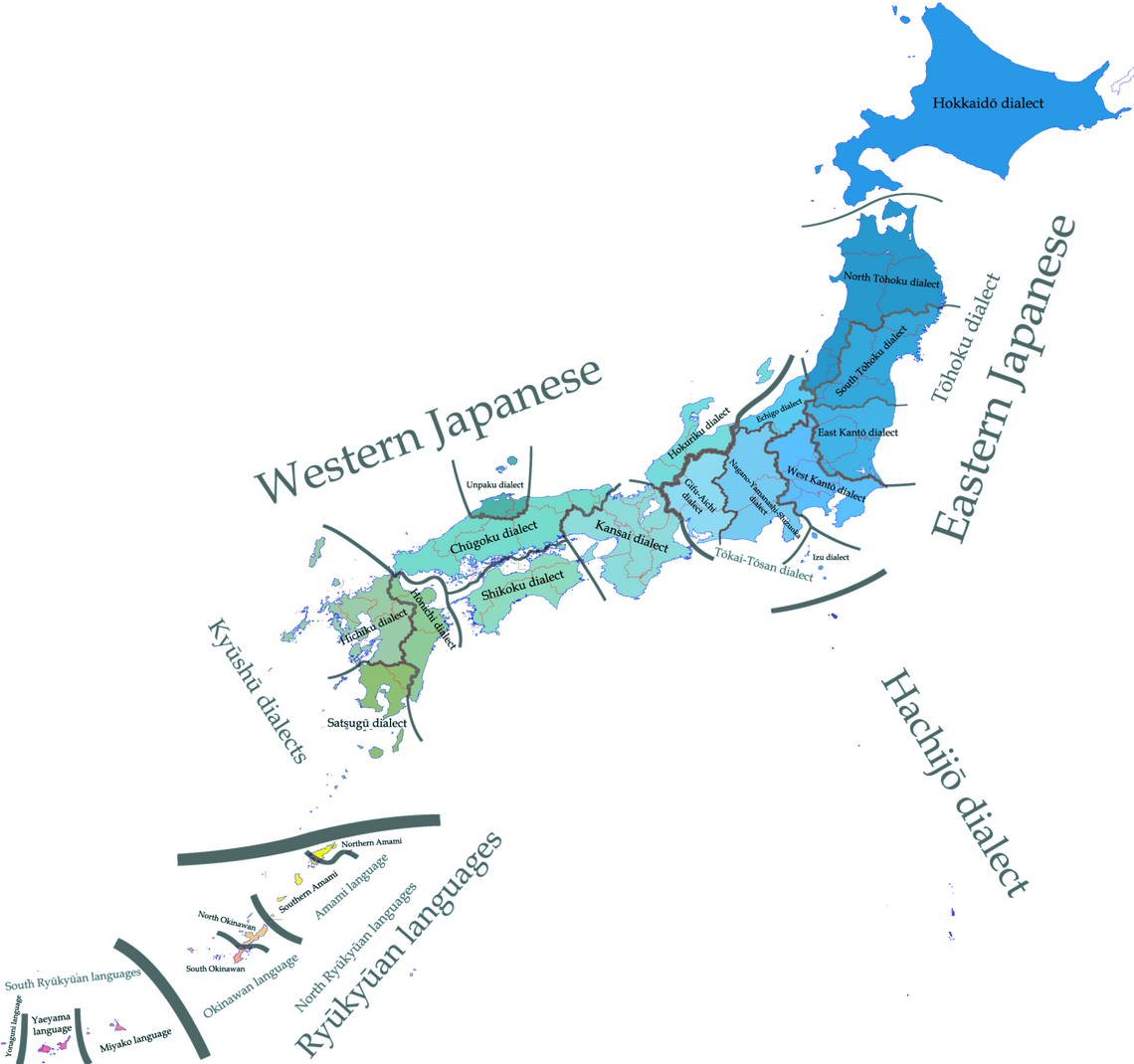

This article is about the modern writing system and its history. For an overview of the entire language, see Japanese language. For the use of Latin letters to write Japanese, see Romanization of Japanese.

| Japanese | |

|---|---|

Japanese novel using kanji kana majiri bun (text with both kanji and kana), the most general orthography for modern Japanese. Ruby characters (or furigana) are also used for kanji words (in modern publications these would generally be omitted for well-known kanji). The text is in the traditional tategaki («vertical writing») style; it is read down the columns and from right to left, like traditional Chinese. Published in 1908. |

|

| Script type |

mixed logographic (kanji), syllabic (hiragana and katakana) |

|

Time period |

4th century AD to present |

| Direction | When written vertically, Japanese text is written from top to bottom, with multiple columns of text progressing from right to left. When written horizontally, text is almost always written left to right, with multiple rows progressing downward, as in standard English text. In the early to mid-1900s, there were infrequent cases of horizontal text being written right to left, but that style is very rarely seen in modern Japanese writing.[citation needed] |

| Languages | Japanese language Ryukyuan languages |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

(See kanji and kana)

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Jpan (413), Japanese (alias for Han + Hiragana + Katakana) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode range |

U+4E00–U+9FBF Kanji U+3040–U+309F Hiragana U+30A0–U+30FF Katakana |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese words and grammatical elements; and katakana, used primarily for foreign words and names, loanwords, onomatopoeia, scientific names, and sometimes for emphasis. Almost all written Japanese sentences contain a mixture of kanji and kana. Because of this mixture of scripts, in addition to a large inventory of kanji characters, the Japanese writing system is considered to be one of the most complicated currently in use.[1][2]

Several thousand kanji characters are in regular use, which mostly originate from traditional Chinese characters. Others made in Japan are referred to as “Japanese kanji” (和製漢字, wasei kanji; also known as “country’s kanji” 国字, kokuji). Each character has an intrinsic meaning (or range of meanings), and most have more than one pronunciation, the choice of which depends on context. Japanese primary and secondary school students are required to learn 2,136 jōyō kanji as of 2010.[3] The total number of kanji is well over 50,000, though few if any native speakers know anywhere near this number.[4]

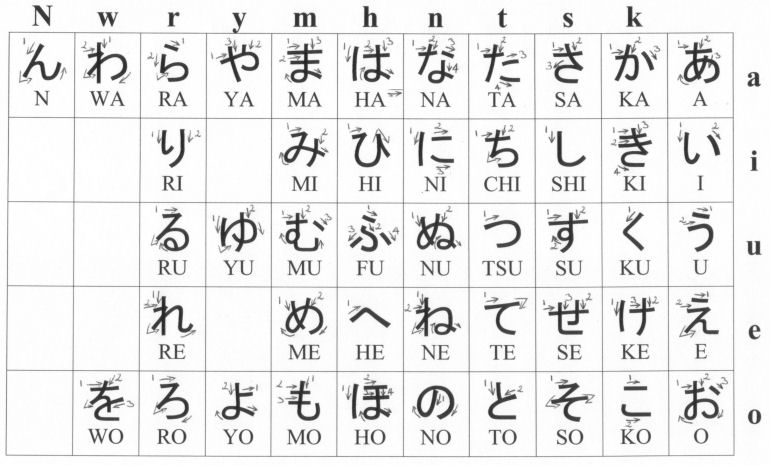

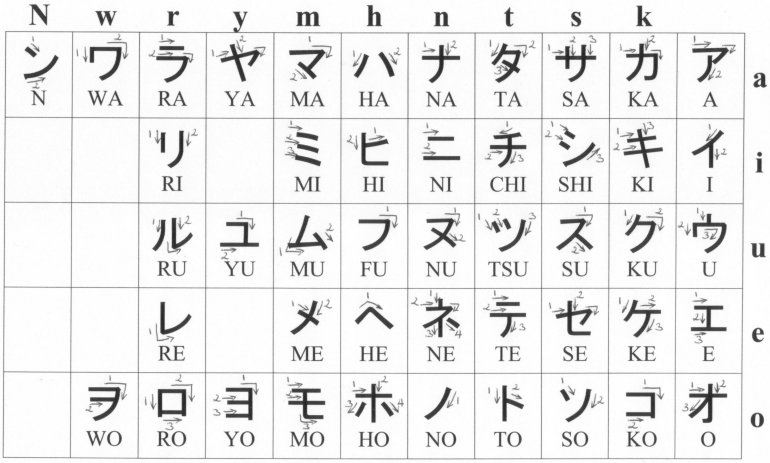

In modern Japanese, the hiragana and katakana syllabaries each contain 46 basic characters, or 71 including diacritics. With one or two minor exceptions, each different sound in the Japanese language (that is, each different syllable, strictly each mora) corresponds to one character in each syllabary. Unlike kanji, these characters intrinsically represent sounds only; they convey meaning only as part of words. Hiragana and katakana characters also originally derive from Chinese characters, but they have been simplified and modified to such an extent that their origins are no longer visually obvious.

Texts without kanji are rare; most are either children’s books — since children tend to know few kanji at an early age — or early electronics such as computers, phones, and video games, which could not display complex graphemes like kanji due to both graphical and computational limitations.[5]

To a lesser extent, modern written Japanese also uses initialisms from the Latin alphabet, for example in terms such as «BC/AD», «a.m./p.m.», «FBI», and «CD». Romanized Japanese is most frequently used by foreign students of Japanese who have not yet mastered kana, and by native speakers for computer input.

Use of scripts[edit]

Kanji[edit]

Kanji (漢字) are logographic characters (based on traditional ones) taken from Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese.

It is known from archaeological evidence that the first contacts that the Japanese had with Chinese writing took place in the 1st century AD, during the late Yayoi period. However, the Japanese people of that era probably had little to no comprehension of the script, and they would remain relatively illiterate until the 5th century AD in the Kofun period, when writing in Japan became more widespread.

They are used to write most content words of native Japanese or (historically) Chinese origin, which include the following:

- many nouns, such as 川 (kawa, «river») and 学校 (gakkō, «school»)

- the stems of most verbs and adjectives, such as 見 in 見る (miru, «see») and 白 in 白い (shiroi, «white»)

- the stems of many adverbs, such as 速 in 速く (hayaku, «quickly») and 上手 as in 上手に (jōzu ni, «masterfully»)

- most Japanese personal names and place names, such as 田中 (Tanaka) and 東京 (Tōkyō). (Certain names may be written in hiragana or katakana, or some combination of these, plus kanji.)

Some Japanese words are written with different kanji depending on the specific usage of the word—for instance, the word naosu (to fix, or to cure) is written 治す when it refers to curing a person, and 直す when it refers to fixing an object.

Most kanji have more than one possible pronunciation (or «reading»), and some common kanji have many. These are broadly divided into on’yomi, which are readings that approximate to a Chinese pronunciation of the character at the time it was adopted into Japanese, and kun’yomi, which are pronunciations of native Japanese words that correspond to the meaning of the kanji character. However, some kanji terms have pronunciations that correspond to neither the on’yomi nor the kun’yomi readings of the individual kanji within the term, such as 明日 (ashita, «tomorrow») and 大人 (otona, «adult»).

Unusual or nonstandard kanji readings may be glossed using furigana. Kanji compounds are sometimes given arbitrary readings for stylistic purposes. For example, in Natsume Sōseki’s short story The Fifth Night, the author uses 接続って for tsunagatte, the gerundive -te form of the verb tsunagaru («to connect»), which would usually be written as 繋がって or つながって. The word 接続, meaning «connection», is normally pronounced setsuzoku.

Kana[edit]

Hiragana[edit]

Hiragana (平仮名) emerged as a manual simplification via cursive script of the most phonetically widespread kanji among those who could read and write during the Heian period (794-1185). The main creators of the current hiragana were ladies of the Japanese imperial court, that used the script in the writing of personal communications and literature.

Hiragana is used to write the following:

- okurigana (送り仮名)—inflectional endings for adjectives and verbs—such as る in 見る (miru, «see») and い in 白い (shiroi, «white»), and respectively た and かった in their past tense inflections 見た (mita, «saw») and 白かった (shirokatta, «was white»).

- various function words, including most grammatical particles, or postpositions (joshi (助詞))—small, usually common words that, for example, mark sentence topics, subjects and objects or have a purpose similar to English prepositions such as «in», «to», «from», «by» and «for».

- miscellaneous other words of various grammatical types that lack a kanji rendition, or whose kanji is obscure, difficult to typeset, or considered too difficult to understand for the context (such as in children’s books).

- Furigana (振り仮名)—phonetic renderings of kanji placed above or beside the kanji character. Furigana may aid children or non-native speakers or clarify nonstandard, rare, or ambiguous readings, especially for words that use kanji not part of the jōyō kanji list.

There is also some flexibility for words with common kanji renditions to be instead written in hiragana, depending on the individual author’s preference (all Japanese words can be spelled out entirely in hiragana or katakana, even when they are normally written using kanji). Some words are colloquially written in hiragana and writing them in kanji might give them a more formal tone, while hiragana may impart a softer or more emotional feeling.[6] For example, the Japanese word kawaii, the Japanese equivalent of «cute», can be written entirely in hiragana as in かわいい, or with kanji as 可愛い.

Some lexical items that are normally written using kanji have become grammaticalized in certain contexts, where they are instead written in hiragana. For example, the root of the verb 見る (miru, «see») is normally written with the kanji 見 for the mi portion. However, when used as a supplementary verb as in 試してみる (tameshite miru) meaning «to try out», the whole verb is typically written in hiragana as みる, as we see also in 食べてみる (tabete miru, «try to eat [it] and see»).

Katakana[edit]

Katakana (片仮名) emerged around the 9th century, in the Heian period, when Buddhist monks created a syllabary derived from Chinese characters to simplify their reading, using portions of the characters as a kind of shorthand. The origin of the alphabet is attributed to the monk Kūkai.

Katakana is used to write the following:

- transliteration of foreign words and names, such as コンピュータ (konpyūta, «computer») and ロンドン (Rondon, «London»). However, some foreign borrowings that were naturalized may be rendered in hiragana, such as たばこ (tabako, «tobacco»), which comes from Portuguese. See also Transcription into Japanese.

- commonly used names of animals and plants, such as トカゲ (tokage, «lizard»), ネコ (neko, «cat») and バラ (bara, «rose»), and certain other technical and scientific terms, such as mineral names

- occasionally, the names of miscellaneous other objects whose kanji are rare, such as ローソク (rōsoku, «candle»)

- onomatopoeia, such as ワンワン (wan-wan, «woof-woof»), and other sound symbolism

- emphasis, much like italicisation in European languages.

Katakana can also be used to impart the idea that words are spoken in a foreign or otherwise unusual accent; for example, the speech of a robot.

Rōmaji[edit]

The first contact of the Japanese with the Latin alphabet occurred in the 16th century, during the Muromachi period, when they had contact with Portuguese navigators, the first European people to visit the Japanese islands. The earliest Japanese romanization system was based on Portuguese orthography. It was developed around 1548 by a Japanese Catholic named Anjirō.

The Latin alphabet is used to write the following:

- Latin-alphabet acronyms and initialisms, such as NATO or UFO

- Japanese personal names, corporate brands, and other words intended for international use (for example, on business cards, in passports, etc.)

- foreign names, words, and phrases, often in scholarly contexts

- foreign words deliberately rendered to impart a foreign flavour, for instance, in commercial contexts

- other Japanized words derived or originated from foreign languages, such as Jリーグ (jei rīgu, «J. League»), Tシャツ (tī shatsu, «T-shirt») or B級グルメ (bī-kyū gurume, «B-rank gourmet [cheap and local cuisines]»)

Arabic numerals[edit]

Arabic numerals (as opposed to traditional kanji numerals) are often used to write numbers in horizontal text, especially when numbering things rather than indicating a quantity, such as telephone numbers, serial numbers and addresses. Arabic numerals were introduced in Japan probably at the same time as the Latin alphabet, in the 16th century during the Muromachi period, the first contact being via Portuguese navigators. These numerals did not originate in Europe, as the Portuguese inherited them during the Arab occupation of the Iberian peninsula. See also Japanese numerals.

Hentaigana[edit]

Hentaigana (変体仮名), a set of archaic kana made obsolete by the Meiji reformation, are sometimes used to impart an archaic flavor, like in items of food (esp. soba).

Additional mechanisms[edit]

Jukujikun refers to instances in which words are written using kanji that reflect the meaning of the word though the pronunciation of the word is entirely unrelated to the usual pronunciations of the constituent kanji. Conversely, ateji refers to the employment of kanji that appear solely to represent the sound of the compound word but are, conceptually, utterly unrelated to the signification of the word.

Examples[edit]

Sentences are commonly written using a combination of all three Japanese scripts: kanji (in red), hiragana (in purple), and katakana (in orange), and in limited instances also include

Latin alphabet characters (in green) and Arabic numerals (in black):

Tシャツを3枚購入しました。

The same text can be transliterated to the Latin alphabet (rōmaji), although this will generally only be done for the convenience of foreign language speakers:

Tīshatsu o san—mai kōnyū shimashita.

Translated into English, this reads:

I bought 3 T-shirts.

All words in modern Japanese can be written using hiragana, katakana, and rōmaji, while only some have Kanji. Words that have no dedicated kanji may still be written with kanji by employing either ateji (like in man’yogana, から = 可良) or jukujikun, like in the title of とある科学の超電磁砲 (超電磁砲 being used to represent レールガン).

| Kanji | Hiragana | Katakana | Rōmaji | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 私 | わたし | ワタシ | watashi | I, me |

| 金魚 | きんぎょ | キンギョ | kingyo | goldfish |

| 煙草 or 莨 | たばこ | タバコ | tabako | tobacco, cigarette |

| 東京 | とうきょう | トーキョー | tōkyō | Tokyo, literally meaning «eastern capital» |

| none | です | デス | desu | is, am, to be (hiragana, of Japanese origin); death (katakana, of English origin) |

Although rare, there are some words that use all three scripts in the same word. An example of this is the term くノ一 (rōmaji: kunoichi), which uses a hiragana, a katakana, and a kanji character, in that order. It is said that if all three characters are put in the same kanji «square», they all combine to create the kanji 女 (woman/female). Another example is 消しゴム (rōmaji: keshigomu) which means «eraser», and uses a kanji, a hiragana, and two katakana characters, in that order.

Statistics[edit]

A statistical analysis of a corpus of the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun from the year 1993 (around 56.6 million tokens) revealed:[7]

|

|

Collation[edit]

Collation (word ordering) in Japanese is based on the kana, which express the pronunciation of the words, rather than the kanji. The kana may be ordered using two common orderings, the prevalent gojūon (fifty-sound) ordering, or the old-fashioned iroha ordering. Kanji dictionaries are usually collated using the radical system, though other systems, such as SKIP, also exist.

Direction of writing[edit]

Traditionally, Japanese is written in a format called tategaki (縦書き), which was inherited from traditional Chinese practice. In this format, the characters are written in columns going from top to bottom, with columns ordered from right to left. After reaching the bottom of each column, the reader continues at the top of the column to the left of the current one.

Modern Japanese also uses another writing format, called yokogaki (横書き). This writing format is horizontal and reads from left to right, as in English.

A book printed in tategaki opens with the spine of the book to the right, while a book printed in yokogaki opens with the spine to the left.

Spacing and punctuation[edit]

Japanese is normally written without spaces between words, and text is allowed to wrap from one line to the next without regard for word boundaries. This convention was originally modelled on Chinese writing, where spacing is superfluous because each character is essentially a word in itself (albeit compounds are common). However, in kana and mixed kana/kanji text, readers of Japanese must work out where word divisions lie based on an understanding of what makes sense. For example, あなたはお母さんにそっくりね。 must be mentally divided as あなた は お母さん に そっくり ね。 (Anata wa okaasan ni sokkuri ne, «You’re just like your mother»). In rōmaji, it may sometimes be ambiguous whether an item should be transliterated as two words or one. For example, 愛する, «to love», composed of 愛 (ai, «love») and する (suru, «to do», here a verb-forming suffix), is variously transliterated as aisuru or ai suru.

Words in potentially unfamiliar foreign compounds, normally transliterated in katakana, may be separated by a punctuation mark called a nakaguro (中黒, «middle dot») to aid Japanese readers. For example, ビル・ゲイツ (Bill Gates). This punctuation is also occasionally used to separate native Japanese words, especially in concatenations of kanji characters where there might otherwise be confusion or ambiguity about interpretation, and especially for the full names of people.

The Japanese full stop (。) and comma (、) are used for similar purposes to their English equivalents, though comma usage can be more fluid than is the case in English. The question mark (?) is not used in traditional or formal Japanese, but it may be used in informal writing, or in transcriptions of dialogue where it might not otherwise be clear that a statement was intoned as a question. The exclamation mark (!) is restricted to informal writing. Colons and semicolons are available but are not common in ordinary text. Quotation marks are written as 「 … 」, and nested quotation marks as 『 … 』. Several bracket styles and dashes are available.

History of the Japanese script[edit]

Importation of kanji[edit]

Japan’s first encounters with Chinese characters may have come as early as the 1st century AD with the King of Na gold seal, said to have been given by Emperor Guangwu of Han in AD 57 to a Japanese emissary.[8] However, it is unlikely that the Japanese became literate in Chinese writing any earlier than the 4th century AD.[8]

Initially Chinese characters were not used for writing Japanese, as literacy meant fluency in Classical Chinese, not the vernacular. Eventually a system called kanbun (漢文) developed, which, along with kanji and something very similar to Chinese grammar, employed diacritics to hint at the Japanese translation. The earliest written history of Japan, the Kojiki (古事記), compiled sometime before 712, was written in kanbun. Even today Japanese high schools and some junior high schools teach kanbun as part of the curriculum.

The development of man’yōgana[edit]

No full-fledged script for written Japanese existed until the development of man’yōgana (万葉仮名), which appropriated kanji for their phonetic value (derived from their Chinese readings) rather than their semantic value. Man’yōgana was initially used to record poetry, as in the Man’yōshū (万葉集), compiled sometime before 759, whence the writing system derives its name. Some scholars claim that man’yōgana originated from Baekje, but this hypothesis is denied by mainstream Japanese scholars.[9][10] The modern kana, namely hiragana and katakana, are simplifications and systemizations of man’yōgana.

Due to the large number of words and concepts entering Japan from China which had no native equivalent, many words entered Japanese directly, with a similar pronunciation to the original Chinese. This Chinese-derived reading is known as on’yomi (音読み), and this vocabulary as a whole is referred to as Sino-Japanese in English and kango (漢語) in Japanese. At the same time, native Japanese already had words corresponding to many borrowed kanji. Authors increasingly used kanji to represent these words. This Japanese-derived reading is known as kun’yomi (訓読み). A kanji may have none, one, or several on’yomi and kun’yomi. Okurigana are written after the initial kanji for verbs and adjectives to give inflection and to help disambiguate a particular kanji’s reading. The same character may be read several different ways depending on the word. For example, the character 行 is read i as the first syllable of iku (行く, «to go»), okona as the first three syllables of okonau (行う, «to carry out»), gyō in the compound word gyōretsu (行列, «line» or «procession»), kō in the word ginkō (銀行, «bank»), and an in the word andon (行灯, «lantern»).

Some linguists have compared the Japanese borrowing of Chinese-derived vocabulary as akin to the influx of Romance vocabulary into English during the Norman conquest of England. Like English, Japanese has many synonyms of differing origin, with words from both Chinese and native Japanese. Sino-Japanese is often considered more formal or literary, just as latinate words in English often mark a higher register.

Script reforms[edit]

Meiji period[edit]

The significant reforms of the 19th century Meiji era did not initially impact the Japanese writing system. However, the language itself was changing due to the increase in literacy resulting from education reforms, the massive influx of words (both borrowed from other languages or newly coined), and the ultimate success of movements such as the influential genbun itchi (言文一致) which resulted in Japanese being written in the colloquial form of the language instead of the wide range of historical and classical styles used previously. The difficulty of written Japanese was a topic of debate, with several proposals in the late 19th century that the number of kanji in use be limited. In addition, exposure to non-Japanese texts led to unsuccessful proposals that Japanese be written entirely in kana or rōmaji. This period saw Western-style punctuation marks introduced into Japanese writing.[11]

In 1900, the Education Ministry introduced three reforms aimed at improving the process of education in Japanese writing:

- standardization of hiragana, eliminating the range of hentaigana then in use;

- restriction of the number of kanji taught in elementary schools to about 1,200;

- reform of the irregular kana representation of the Sino-Japanese readings of kanji to make them conform with the pronunciation.

The first two of these were generally accepted, but the third was hotly contested, particularly by conservatives, to the extent that it was withdrawn in 1908.[12]

Pre–World War II[edit]

The partial failure of the 1900 reforms combined with the rise of nationalism in Japan effectively prevented further significant reform of the writing system. The period before World War II saw numerous proposals to restrict the number of kanji in use, and several newspapers voluntarily restricted their kanji usage and increased usage of furigana; however, there was no official endorsement of these, and indeed much opposition. However, one successful reform was the standardization of hiragana, which involved reducing the possibilities of writing down Japanese morae down to only one hiragana character per morae, which led to labeling all the other previously used hiragana as hentaigana and discarding them in daily use.[13]

Post–World War II[edit]

The period immediately following World War II saw a rapid and significant reform of the writing system. This was in part due to influence of the Occupation authorities, but to a significant extent was due to the removal of traditionalists from control of the educational system, which meant that previously stalled revisions could proceed. The major reforms were:

- gendai kanazukai (現代仮名遣い)—alignment of kana usage with modern pronunciation, replacing the old historical kana usage (1946);

- promulgation of various restricted sets of kanji:

- tōyō kanji (当用漢字) (1946), a collection of 1850 characters for use in schools, textbooks, etc.;

- kanji to be used in schools (1949);

- an additional collection of jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字), which, supplementing the tōyō kanji, could be used in personal names (1951);

- simplifications of various complex kanji letter-forms shinjitai (新字体).

At one stage, an advisor in the Occupation administration proposed a wholesale conversion to rōmaji, but it was not endorsed by other specialists and did not proceed.[14]

In addition, the practice of writing horizontally in a right-to-left direction was generally replaced by left-to-right writing. The right-to-left order was considered a special case of vertical writing, with columns one character high[clarification needed], rather than horizontal writing per se; it was used for single lines of text on signs, etc. (e.g., the station sign at Tokyo reads 駅京東).

The post-war reforms have mostly survived, although some of the restrictions have been relaxed. The replacement of the tōyō kanji in 1981 with the 1,945 jōyō kanji (常用漢字)—a modification of the tōyō kanji—was accompanied by a change from «restriction» to «recommendation», and in general the educational authorities have become less active in further script reform.[15]

In 2004, the jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字), maintained by the Ministry of Justice for use in personal names, was significantly enlarged. The jōyō kanji list was extended to 2,136 characters in 2010.

Romanization[edit]

There are a number of methods of rendering Japanese in Roman letters. The Hepburn method of romanization, designed for English speakers, is a de facto standard widely used inside and outside Japan. The Kunrei-shiki system has a better correspondence with Japanese phonology, which makes it easier for native speakers to learn. It is officially endorsed by the Ministry of Education and often used by non-native speakers who are learning Japanese as a second language.[citation needed] Other systems of romanization include Nihon-shiki, JSL, and Wāpuro rōmaji.

Lettering styles[edit]

- Shodō

- Edomoji

- Minchō

- East Asian sans-serif typeface

Variant writing systems[edit]

- Gyaru-moji

- Hentaigana

- Man’yōgana

See also[edit]

- Genkō yōshi (graph paper for writing Japanese)

- Iteration mark (Japanese duplication marks)

- Japanese typographic symbols (non-kana, non-kanji symbols)

- Japanese Braille

- Japanese language and computers

- Japanese manual syllabary

- Chinese writing system

- Okinawan writing system

- Kaidā glyphs (Yonaguni)

- Ainu language § Writing

- Siddhaṃ script (Indic alphabet used for Buddhist scriptures)

References[edit]

- ^ Serge P. Shohov (2004). Advances in Psychology Research. Nova Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-59033-958-9.

- ^ Kazuko Nakajima (2002). Learning Japanese in the Network Society. University of Calgary Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-55238-070-3.

- ^ «Japanese Kanji List». www.saiga-jp.com. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ «How many Kanji characters are there?». japanese.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ^ «How To Play (and comprehend!) Japanese Games». GBAtemp.net -> The Independent Video Game Community. Retrieved 2016-03-05.

- ^ Joseph F. Kess; Tadao Miyamoto (1 January 1999). The Japanese Mental Lexicon: Psycholinguistics Studies of Kana and Kanji Processing. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 90-272-2189-8.

- ^ Chikamatsu, Nobuko; Yokoyama, Shoichi; Nozaki, Hironari; Long, Eric; Fukuda, Sachio (2000). «A Japanese logographic character frequency list for cognitive science research». Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 32 (3): 482–500. doi:10.3758/BF03200819. PMID 11029823. S2CID 21633023.

- ^ a b Miyake (2003:8).

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2002). 韓国人の日本偽史―日本人はビックリ! (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-402716-7.

- ^ Shunpei Mizuno, ed. (2007). 韓vs日「偽史ワールド」 (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4-09-387703-9.

- ^ Twine, 1991

- ^ Seeley, 1990

- ^ Hashi (25 January 2012). «Hentaigana: How Japanese Went from Illegible to Legible in 100 Years». Tofugu. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ^ Unger, 1996

- ^ Gottlieb, 1996

Sources[edit]

- Gottlieb, Nanette (1996). Kanji Politics: Language Policy and Japanese Script. Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7103-0512-5.

- Habein, Yaeko Sato (1984). The History of the Japanese Written Language. University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 0-86008-347-0.

- Miyake, Marc Hideo (2003). Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-30575-6.

- Seeley, Christopher (1984). «The Japanese Script since 1900». Visible Language. XVIII. 3: 267–302.

- Seeley, Christopher (1991). A History of Writing in Japan. University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2217-X.

- Twine, Nanette (1991). Language and the Modern State: The Reform of Written Japanese. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00990-1.

- Unger, J. Marshall (1996). Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan: Reading Between the Lines. OUP. ISBN 0-19-510166-9.

External links[edit]

- The Modern Japanese Writing System: an excerpt from Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan, by J. Marshall Unger.

- The 20th Century Japanese Writing System: Reform and Change by Christopher Seeley

- Japanese Hiragana Conversion API by NTT Resonant

- Japanese Morphological Analysis API by NTT Resonant

In Japanese, foreign names are normally written using the phonetic katakana alphabet. To see what your name looks like in Japanese, just type it in below and click the “Translate” button. If you like, you can also choose from a few different character styles.

Notes

- This dictionary does not contain Japanese names. Japanese names are normally written using kanji characters, not katakana.

- The Japanese write foreign words phonetically, so it is not always possible to say how a name should be written in Japanese without further information. For example, the last two letters of Andrea can be pronounced like ier in the word barrier, or like ayer in the word layer. If you get results that don’t match the way you pronounce your name, you may be able to find an alternative spelling that does (e.g., Andria).

- Traditionally, some names have unusual pronunciations in Japanese. For example, the name Phoenix is often pronounced “fen-ix” instead of the more accurate “fee-nix”. In this dictionary I have opted for the spelling closest to the actual pronunciation.

- The use of an accented U to represent the sound of the letter “V” seems to be a recent innovation in Japanese writing. Earlier sources tend to use a B sound instead, so for example Kevin is often pronounced kebin rather than kevin. For the sake of consistency, I have used the more accurate notation throughout this dictionary.

- (Disclaimer) Unlike many of the other “name translators” on the web, this tool is a real dictionary containing about 3,700 names. Each one has been individually checked, and errors are extremely uncommon. However, since this is a free service, I can’t accept liability for any problems that might occur. If you’re planning on getting a Japanese tattoo, I would strongly recommend you at least study katakana first. There are plenty of resources available online.

Using the Images

The images produced by this dictionary are free for personal use. To save a picture to your hard disk, move your cursor over the picture, click the right-hand mouse button, and choose «Download Image to Disk» from the pop-up menu that appears. (Mac users: drag the image to your desktop). A link back to this page would be appreciated, but is by no means mandatory. Please don’t link directly to images in this page. They are stored in a temporary folder and are deleted after 24 hours.

Problems?

If you’re seeing an error image where your name should be, then maybe your browser isn’t working properly. This problem — among others — is discussed in the FAQ page.

Above all, this article is for those who have just started learning Japanese and do not know anything about it yet. Specifically for them, we have collected many tips to get a hold and never let go of Japanese. Let’s face it: there will be difficulties, they will begin after the first few months. But this article will help you deal with them.

The article will also be useful to those who have already reached the level of Intermediate and above. Here you will find resources that will help you to build your vocabulary, learn characters and grammar, practice listening and pronunciation.

Features of the Japanese language

- Difficult writing. The writing system in Japanese consists not only of kanji hieroglyphs but also of two syllabic alphabets — hiragana and katakana. Each of them has 46 characters. The first is used to write Japanese words, endings, particles, and other parts of speech. The second is for writing foreign words, names, and titles. Hiragana and katakana are collectively referred to as kana. The Latin alphabet is also used in Japanese, for example, for transliteration. In this case, the Latin letters are called romaji.

- Hieroglyphs have many readings. A hieroglyph in Japanese usually has more than one reading. Sometimes their number reaches 10 and even 15 for a single kanji. In addition, all readings are divided into two types: Japanese, or kunyomi, and Chinese — onyomi.

- Pitch accent. In Japanese, words are not divided into syllables, but into moras. These are rhythmic units pronounced with the same duration, so there is no stress like we are used to in English. But there is a “pitch accent”, which works by raising and lowering the voice. Each syllable-mora is pronounced in a high or low pitch, and the word acquires a unique accent outline. Moreover, Japanese, unlike Chinese, is not a tonal language. In tonal languages, the tone changes within one syllable, while in Japanese moras it doesn’t.

- Many cases. Various scholars distinguish between 10 and 15 grammatical cases in Japanese. For comparison, there are only six of them in Russian and three in English (in the latter they have been largely reduced to the use of different pronouns). In Japanese the nouns are changed by case using suffixes. Some cases can be combined and “layered” on top of each other.

- The verb is always at the end. Japanese word order is not as strict as, for example, English or Chinese. But there is still one strict rule: the predicate is always placed at the end of the sentence. In English, we say “Mary had a little lamb”, and in Japanese, it would be “A little lamb Mary had”. Therefore, beginners have to restructure their very thinking patterns to fit the Japanese word order.

- Just two tenses. In Japanese, there is no grammatical division into present and future tenses. Both are expressed in the same way. Because of this, it can be difficult for beginners to understand what the Japanese are talking about: is it their plans or what they are doing at the moment?

- Layering suffixes. In Japanese, all grammar is expressed using overlapping suffixes. Because of this, the words turn out to be very long and contain many meanings at once. For example, the word “来てほしくなかった” means “(I) didn’t want (you) to come”. It reads as “ki-te-hoshi-ku-na-katta” and has five suffixes.

- There is no indication of the plural. There is no grammatical way to show the number in Japanese. In English, for example, we can say “chair” and “chairs”, but in Japanese there is no such distinction. Whether it is many chairs or just one is clear only from the context. But some words can simply be repeated, and it turns them into plurals. For example, yama is a mountain, yama-yama is “many mountains.”

- Many Chinese borrowings. The Chinese culture has greatly influenced Japanese culture. Together with the Chinese characters, the Japanese also have borrowed words. Because of this, in the modern language, about half of all vocabulary is of Chinese origin. By the way, the same is the case in the Korean language.

- Polite language. The Japanese are known all over the world for their politeness, and this is reflected even in the language. There are three main registers of speech in Japanese. The topmost is called keigo (敬語), “polite language.” It really feels like a language within a language. It uses separate words and grammatical constructions, so even among the Japanese themselves, many do not speak it at a good level.

How do I learn Japanese on my own?

Before you start learning, remember a few simple rules:

- Learn the language comprehensively. This means practicing all aspects of the language. Learn grammar, read, listen, speak. This will help you memorize new material better and really use the language. In the case of Japanese, at the beginning of learning, it is worth learning a small selection of basic words and characters so that studying further grammar and other sections will be easier. Some resources advise you to learn 300 characters before mastering grammar, but we recommend trying at least 50-100 first.

- Make learning fun. Sincere interest is the best fuel for motivation. Think about what you like the most about Japanese language and Japanese culture. If it’s anime — watch your favorite titles with Japanese subtitles; if music, then translate the lyrics of your favorite songs. Perhaps you are fond of kendo or ikebana, in which case you can read specialized texts about these activities in Japanese.

- Learn the language every day. Constant repetition is the key to mastering any language. You can find time to study even on the busiest days — study on the subway, at lunchtime, or for 15 minutes before bed. Apps like Duolingo, Memrise, or Quizlet can help you with this.

- Take small steps. Remember the rule: before taking on something new, you should already have perfected 80% of previous material. You shouldn’t get in over your head and immediately tackle advanced grammar and complex texts. This will only waste your time. Move forward gradually, in small steps.

So what should be your first steps in learning Japanese?

Hiragana — The Japanese alphabet

Hiragana is one of the three components of the Japanese writing system. The other two are katakanaanother alphabet and kanjihieroglyphs, we’ll tell more about them later. It’s best starting with hiragana. Once you learn it, you can read and write Japanese words. In many textbooks, knowing hiragana is a prerequisite for starting classes.

The letters in hiragana denote not individual sounds, like in the English alphabet, but rather moras, rhythmic units. They differ from syllables in that they are pronounced with the same duration, and they do not always include vowels. For example, the sound [n] (ん) in Japanese is a mora, but not a syllable.

Hiragana consists of 46 characters. Learning them is not as difficult as it seems. You can do this in a week, and just learning to read can take roughly just a day. Using hiragana is quite simple: words are written as they are heard. There are exceptions, but they can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Resources for learning hiragana

Basics of Japanese pronunciation

Japanese is considered a phonetically poor language: it has fewer sounds than many others. Because of this, phonetics is usually called the easiest part of learning it. But although there are few sounds in Japanese, most of them are very different from the English ones: many English sounds don’t exist in Japanese and vice versa, there are only 5 vowels in comparison to the English 15, and so on. Therefore, it is important at the very beginning to devote time to the basics of pronunciation. At least to read hiragana in Japanese, not some other language.

Do not go too deep: in the initial stages, you should not be interested in Japanese pitch accent. Just know that it exists. But the pronunciation of the Japanese [r] sound (which is closer to [l] in [l]ip than to English [r]), the peculiarities of reading ふ つ ち し and long vowels are the things you must know.

You can read about this in more detail here.

How to type in Japanese

Some modern tutorials do away with traditional writing altogether and go straight to typing characters on a computer. This is due to the fact that situations when we have to write by hand happen less and less often. Typing in Japanese is very easy: you can master it in less than an hour. You just need to install the Japanese keyboard layout on your computer, and then you can enter Japanese characters using their Latin readings. If you have any difficulties, refer to the video below.

But learning to write hiragana is still worth it — without it, you will have a hard time with kaiji. And if you go to Japan, especially to study, you cannot avoid it: to this day, the main tools of the Japanese bureaucracy are paper and pen.

What is the Japanese hieroglyph

You will begin encountering kanji characters from the very beginning of studying, so getting around them is impossible. First of all, you need to figure out what they are. In short, a hieroglyph is a symbol. It differs from the letters of the alphabet in that it has not only reading but also meaning. A hieroglyph can be a word in itself, or it can be part of a word made up from several hieroglyphs. At the same time, each kanji has two readings — Japanese reading, or kunyomi, and Chinese — onyomi. Details about the difference in readings are given here, and about the structure of hieroglyphs — here.

First kanji and words

Once you understand the basics, you can start learning kanji. It is necessary to memorize not only the spelling and meanings of hieroglyphs, but also their readings, and the words in which they are included. This way the kanji will stay in your head for a long time.

You determine the scope of work yourself. A good learning pace is 20-30 characters and 100 words per week, but 10 kanji is also fine. How exactly you memorize hieroglyphs — by writing in a notebook or by saving in an application — is not so important. The main thing is just to do it. Though we can say from personal experience that handwritten hieroglyphs are remembered better.

Kanji is often learned later, several months after the start of studies. Learning hieroglyphs early, however, has one big advantage: once you plunge headlong into grammar, you will already have a good vocabulary to compose sentences and practice. You will immediately be able to read what is written in the textbook, therefore you won’t be distracted by unfamiliar words.

Still, you should not try to memorize all the hieroglyphs that you come across, memorize only the major ones. Words consisting of complex kanji, or conversely, lacking kanji, can be written and taught in hiragana.

Resources for learning kanji

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Wanikani | An application for memorizing kanji and words, built on mnemonics and spaced repetition. Its downside — the application is paid: it costs 9 USD per month or 89 USD per year. |

| Quizlet | One of the most popular apps, great for learning hieroglyphs and new words. Quizlet allows you to create flashcards yourself or use ready-made sets. |

| Memrise | An app for learning Japanese phrases and words. Based on the principle of spaced repetition, has a nice design, uses mnemonics. |

| Japanese Kanji Flashcards | A set of cards with the first 300 kanji. The set is very high quality, but also expensive — 36 USD excluding delivery. Suitable for those for whom the application is not enough and it is important to have its physical equivalent. However, you can make cards yourself, the old-fashioned way — with nothing more than paper, scissors, and some elbow grease. |

|

Japanese Kanji Study |

An application designed specifically for learning kanji. In it, you can not only memorize the readings and meanings of hieroglyphs but also practice writing. However, the interface may seem overly complicated. |

| Jisho.org | English-Japanese and Japanese-English online dictionary. You can search both for words and individual kanji. The kanji pages have detailed information with readings, meanings and usage examples. A mobile application is also available. |

| Tangorin | Another online dictionary. The functionality is the same as that of Jisho.org, plus a hieroglyph search by key is available. There is also a mobile application. |

| Tatoeba | A corpus dictionary. It contains examples of the use of words in context and their translation into different languages. |

Katakana

At the same time as learning kanji, you should start learning katakana. Katakana is the second of the Japanese alphabets. It is mainly used for writing foreign and loaned words. For beginners, it is usually more difficult due to the fact that it is used less often. In it, as in hiragana, there are 46 symbols that denote the same sounds. Some of the letters are similar, but most are different beyond recognition. Don’t worry, with additional resources it is not difficult to learn them.

Resources for learning katakana

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Tofugu — Learn Katakana | Memorizing katakana using mnemonic techniques. The guide teaches only to read characters, but not to write. |

| Kana | Application for learning katakana and hiragana. |

Japanese grammar

Once you have a minimal vocabulary, you can start practicing grammar. You will probably already know something about the word order and cases by then. The tutorials will help you delve into the topic. All the material in them is built according to a well-thought-out program so that the level of difficulty will increase gradually. The disadvantage of textbooks is that most of them are designed for lessons with a teacher, so they do not explain many things.

Alternatively, there are many resources devoted to grammar, and on the website Hinative, you can ask questions to native speakers. If you are learning the language on your own, make sure to check their answers in several sources.

And yet, you will surely come across topics that you won’t be able to find answers to, no matter how hard you try. In this case, it is worth hiring a tutor. Do it as early as possible, especially if you have little experience in learning foreign languages. However, do not rely entirely on the teacher. You need to learn hieroglyphs on your own (and do it consistently). The teacher will not do it for you, and they are given too little attention in the textbooks.

Japanese tutorials for beginners

| Tutorial | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Genki |

|

|

| Minna no nihongo |

|

|

| Yookoso! |

|

|

Grammar

| Resources Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| A Dictionary of Basic Japanese Grammar A | Paperback guide to Japanese grammar. Covers more topics than any other book, website, or tutorial. The explanations are clear and easy to understand, with many examples. |

| Tofugu An | A portal dedicated to the Japanese language. Lots of useful articles, including grammatical ones. |

| Kim’s Guide to Learning Japanese | A textbook and a grammar reference book. |

Reading in Japanese

By reading, you fix familiar words and expressions in your memory and learn new ones. But if you have just started to master the language, reading authentic Japanese texts will not be possible for you. You need adapted texts in either hiragana or kanji with furigana. Furigana is a kanji reading added next to it in hiragana. These can be found in textbooks, but children’s books of fairy tales are also suitable. You can also use the website Satori Reader. It has texts for different levels, and they can be adapted to suit your needs: add furigana to all the hieroglyphs or only to some, leave spaces between words, or remove them — like in a proper Japanese text. You can find a detailed guide on using the application here.

Resources for reading practice

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| Satori Reader | Collection of texts for different levels with many options for customization. The materials can not only be read, but also listened to: they are all supplemented with audio recordings. With their help, you can practice pronunciation by repeating the text word for word after the speaker. |

| Japanese fairy tales | Children’s stories written in hiragana. |

| EhonNavi | Site with Japanese books for children. The only downside is that the site itself is also in Japanese. |

| CosCom | Short news for beginners. The text can be switched between romaji, kana and kanji. |

| Kodomo Asahi | Children’s version of the famous Asahi newspaper. The vocabulary is simpler there, and the hieroglyphs are signed with furigana. |

| Matcha | Japanese travel and culture magazine. Available in a simplified version with furigana. |

| Read Real Japanese | Books for intermediate to advanced level. |

Listening in Japanese

Assignments are included in all good textbooks. You can do them both with a tutor or on your own: there is usually a script of each recording at the end of the book. True, the dialogues in the textbooks are always very similar — this is either a trip to the bank, a conversation with a teacher, or a «Sorry, I lost my wallet, can you tell me where the nearest police station is?» sort of deal. It gets boring quickly, so additional resources will come in handy.

For beginners, FluentU is great. The materials there are divided into levels, but they contain real unadapted Japanese. Therefore, classes there are a challenge, but a doable one.

You can also use children’s cartoons to practice listening. For example, Ganbare! Oden-kun (がんばれ!おでんくん) or Nihon Mukashibanashi (日本昔話). The wording in them is not very difficult, so you can study up to the Intermediate level. Particularly useful words can be written out and memorized. On your first watch, it’s best to turn off subtitles and try to understand as much as possible yourself. And then, after viewing it a few times, turn the subtitles on and check how well you understand the words.

Resources for listening

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| FluentU | Site for language learning through video and audio. The materials are divided into levels, with subtitles in English and Japanese. It is convenient for seeing the meanings of unfamiliar words and adding them to the study lists. The resource is paid, but there is a trial period. |

| JapanesePod101.com | Short audio and video lessons in Japanese for any level. |

| News in Slow Japanese | Japanese news read slowly and clearly. |

| The Japanese Page A | A resource designed specifically for beginners. Contains Japanese dialogue recordings and English explanations. |

| Learn Japanese Pod | Podcasts in English for beginners in the form of audio lessons, where teachers analyze simple Japanese conversations. The vocabulary is not complex, and the speech is slow. |

| Erin’s Challenge | Instructional videos about exchange student Erin’s adventures in Japan. Basic vocabulary, everyday situations, and funny dialogues. |

| NHK Radio Podcast | Podcasts from NHKJapanese broadcasting company for a high level of language proficiency. The vocabulary is complex and the speed of speech is unadjusted. |

Speaking Japanese

Stress in Japanese

Since we have reached the point of speaking, it’s time to say a few words about pitch accent. Contrary to popular belief, accent exists in Japanese. There it is done by raising and lowering the voice and somewhat resembles singing. Actually, that is why it is called «pitch.» The meaning of a word sometimes depends on the correct stress.

Again, at the beginner level, you should not get into the depths and try to memorize the accent outline of each word, but it is still worth learning the basic rules, especially since there are only three of them. Find detailed information here. You can check the pronunciation of a word in the OJAD dictionary.

The correct use of stress will make your Japanese speech much clearer and more beautiful than most foreigners’ (especially beginners). Favorite anime and TV series will help you to improve your pronunciation. Pay attention to the way the characters speak when you watch them. Repeat them word for word, copying the intonation. This technique is called «shadowing.» If you are a big fan of Japanese culture, you will not notice how you start to speak more naturally.

Finding opportunities to speak

You can try to find a language partner on social media or apps like Tandem or Easy Language Exchange. Another way is to enroll in courses or hire a teacher.

Create a language environment around you

The more you interact with the language, the faster you progress. So surround yourself with it as much as possible. If you are reading this article and have reached this far, you have probably already watched a huge number of anime. Passion will bring real benefits if you revisit your favorite titles with Japanese subtitles. Yes, it will be difficult, but that is why it is worth starting with what you have already watched — after all, you know perfectly well what is going on. And this time, you will definitely pick up something other than kawaii and senpai.

If you are not a fan of anime, then Japanese culture has many other interesting things to offer, from the classics of world cinema to insane TV shows. And watch more Japanese YouTube. Sometimes fascinating things are hidden where you least expect them — for example, in real estate reviews.

- A selection of the best Japanese films;

- A selection of anime;

- A selection of the best YouTube channels;

- The best Japanese TV series on Netflix.

Need to learn a language?

You can study the language not only on your own but also in courses and with a tutor. Each method has its own advantages.

Courses:

- The cost is lower than for lessons with a tutor;

- More speaking practice — the student gets used to the speech of different people;

- The ability to learn not only from your mistakes but also from others;

- Competition in the classroom can provide additional incentives for learning.

Tutor:

- The teacher will devote all the time only to you;

- You can practice at a comfortable pace for yourself, neither wait for nor try to catch up to others. This is especially relevant for the Japanese language because the groups are often composed of people with completely different levels.

The most effective way to learn a language is in its natural environment, in language courses in Japan. But it is better to go there, already knowing at least the basics. Absolute beginners will have a hard time: Japan speaks very bad English[1]. There are two good websites for finding a tutor, even a native Japanese: Preply and italkiA

Self-study resources

| Resource | Features |

|---|---|

| DuolingoPlay | Gamified language courses. |

| Memrise | Suitable for learning basic words and expressions. Poor for learning kanji and grammar. |

| LingQ | Language learning resource. The assignments and materials cover different aspects: kanji, reading, listening. |

| Learn Japanese From Zero | Tutorials on YouTube based on the book Learn Japanese from Zero. |

| Learn Japanese on Reddit | Community learning Japanese. Here you can learn about personal experiences, difficulties, and lifehacks. |

| Onomatopedia | Resource for learning onomatopoeic words. In Japanese, they play a very important role — without them, your speaking will not be natural. |

| YouTube channel JapanesePod101.com | A channel for learning Japanese. Lots of assignments and explanatory materials. |

Why learn Japanese?

Most people start learning Japanese because of their interest in the culture of the country, but not for practical reasons, unlike, for example, Chinese. Indeed, all 126 million native speakers of Japanese live in one country, so the language’s applications seem limited. Is that so?

Travel

Japanese is unlikely to be useful anywhere outside the Land of the Rising Sun — unless you work as a translator. But on the other hand, Japan itself, although not very large geographically, is surprisingly rich — both culturally and naturally. The northernmost island, Hokkaido, is located very close to the Russian Sakhalin, while the southernmost ones, Okinawa and the Ryukyu archipelago, have a climate similar to Hawaii. At the same time, unlike many countries, it is pleasant to go to Japan at any time of the year. Every season there is bright, with its own advantages: in summer — lush greenery, fireflies, and cicadas; in autumn — red maples; in winter — camellia and persimmon buds under the snow; in spring — blooming plum and sakura. Each prefecture in Japan has a rich history and traditions. Local dishes, crafts, and customs exist in many parts of Japan, even very small villages. However, outside of Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto, English is spoken rarely, if at all. So, without knowing the language, getting a complete picture of Japan will not be possible.

Japanese for studying

Education in Japan is also respected outside the country: according to QS ranking, five Japanese universities are included in the top 100-world universities. Education is not cheap, on average it costs from 7,000 USD per year. But there is an opportunity to study for free.

Every year the Japanese government holds a competition for the MEXT scholarship. It is intended for students of all levels of study: undergraduate, graduate, and PhD. The scholarship fully covers the cost of studying at a Japanese university, plus students are paid a monthly allowance of 897 USD to 1,106 USD. This will be enough for accommodation and meals. Knowledge of Japanese is not a prerequisite for the scholarship, but it will be an advantage.

Japanese for work and immigration

Many people dream of moving to Japan because of the high standards of living. The most realistic way to do this is through employment, and for this, you will definitely need the Japanese language, and at a fairly high level. To work in a Japanese company, you will have to learn not only the specialized vocabulary but also keigo (敬 語) — «polite language.» Without it, communication with customers, or within the company itself, will not be possible.

After graduation from a Japanese university, it will be easier to stay in the country. The unemployment rate in the country is very low — 2.29%[2]. The most demanded professions are IT specialists, marketing specialists, medics, engineers, and designers[3].

After five years of living in the country, you can apply for citizenship. However, the time spent in the country on a student visa is not taken into account. There are no specific language requirements for citizenship, however, the applicant is expected to have fluency in the language. The language proficiency test is not always requested[4]. Other requirements include:

- Be over 20 years old;

- Confirm the absence of a criminal record;

- Confirm the ability to support oneself;

- Renounce the citizenship of the country of origin.

Find language courses

Japanese exams — Japanese language levels

There are various tests to evaluate foreigners’ knowledge of Japanese. The most important and most common of these is JLPT, or nihongo noryoku shiken (日本語能力試験). JLPT has five levels, from N1 to N5, with N1 being the highest and N5 the lowest. The levels roughly correspond to the European CEFR scale from A1 to C1 (N5 = A1, N1 = C1). The exam tests the student’s ability to read and use hieroglyphs, as well as listening comprehension. At the same time, there are no parts with writing and speaking in the test, which is why it is constantly criticized.

The exam is taken twice a year — in December and July. JLPT costs much less than international exams in English — 25-37 USD.

The JLPT test provides official proof of Japanese language proficiency. It can be useful for several purposes:

- For studying — the minimum level for admission to a university for a Japanese-language program is N2. If you intend to study in English, Japanese is not required. But in the scholarship competitions, any level, even N5, will be an advantage.

- For work — here the minimum level is again N2, and in large companies, N1 may be required. If you are choosing a Japanese tutor, make sure that their level is also at least N2. Otherwise, there will be little purpose to the classes.

- For yourself — you can take the Japanese exam just to assess your progress and start preparing for the next level.

| Level | Number of kanji | Number of words |

|---|---|---|

| N5 | 100 | 800 |

| N4 | 300 | 1500 |

| N3 | 650 | 3700 |

| N2 | 1000 | 6000 |

| N1 | 2000 | 10000 |

Download Article

Download Article

You want to say «Japan» (日本 or にほん) in Japanese. Pronounce it as «Nippon» or «Nihon.» There is no single «correct» pronunciation, so try to take your cues from those around you. Read on for more information!

-

1

Know that Japanese uses two «alphabets.» Hiragana is used for native words when there is not a relevant kanji and katakana is used to write adapted foreign words. Both systems use characters to represent syllables.Kanji, which originated in China and still bears many similarities to Chinese writing is used in place of hiragana to specify the meaning of a written words as many words share pronunciations, e.g god and paper. Thus, you may often see the word «Japan» written as 日本 (kanji) or にほん (hiragana).[1]

- In kanji, 日, or «ni,» is the character for «sun.» 本, or «hon,» is the character for «origin.» Thus, «Japan» literally means «sun-origin,» or «The Land of the Rising Sun.»

-

2

Pronounce either にほん or 日本 as «Nihon.» The syllables sound like «knee» and «hon». Say «hon» as in «home»[2]

- «Nihon» may also sound like «Nippon.» Pronounce it «Knee-pon» – «pon» as in «poll», and with a small pause between the syllables. Either pronunciation is accepted in Japan.

Advertisement

-

3

Say «Japanese.» To say «Japanese» in Japanese, add the syllable «go» (same as English «go») to the end of «Nihon.» Pronounce it «Nihongo» or «Nee-hon-go.»[3]

-

4

Understand that the pronunciation is a matter of debate. In past centuries, the Japanese language has been subject to the influence of Chinese monks, European explorers, and various foreign merchants. There is still no full consensus about whether the name is pronounced «Nihon» or «Nippon.» «Nippon» is the older pronunciation – but a recent survey showed that 61 percent of native speakers read the word as «Nihon,» while only 37 percent read it as «Nippon.» When in doubt, take your cues from the people around you.[4]

- Some claim that traditionally, Japanese used «Nihon» to refer to their nation when communicating between themselves, and «Nippon» when speaking to outsiders. This has not been officially verified, and there is no formally «correct» pronunciation.

-

5

Listen to someone say it. The best way to learn how to pronounce the word is to hear someone say it. Once you’ve heard it, practice saying it yourself. Look online for videos or recordings of people saying «日本». If you have any friends or family members who are native Japanese speakers, ask them to pronounce the word for you.[5]

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

How do you say Regan in Japanese?

Arianna Harrell

Community Answer

You need to say ¨リーガン¨ for Regan in Japanese.

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Thanks for submitting a tip for review!

About This Article

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 64,902 times.