-

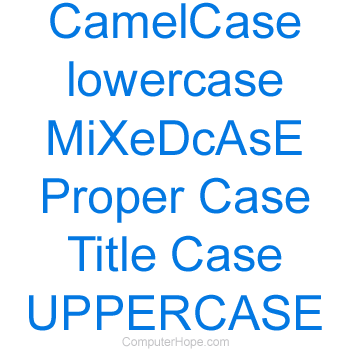

Capitalization Writing the first letter of a word in uppercase, and the rest of the letters in lowercase.

-

Title Case All words are capitalized, except non-initial articles like “a, the, and”, etc. Used for…um, titles.

-

lowercase All letters in all words are lowercase.

-

Sentence case Capitalization just like a standard English sentence, e.g. “The damn has broken.” Many sub-titles use this case format.

-

ALL CAPS All letters in every word are capitalized. Used for extreme emphasis and considered rude when used over the Internet.

-

SMALL CAPS Only capital letters are used for all letters in all words, but the letters are the size of lowercase letters of the font, not the uppercase.

-

CamelCase Words are written without spaces, and the first letter of each word is capitalized. Also called Upper Camel Case or Pascal Casing.

-

lowerCamelCase A variation of Camel Case in which the fist letter of the word is lowercase, e.g. iPhone, iPad, etc.

-

SNAKE_CASE Punctuation is removed and spaces are replaced by a single underscore. Can be done with either upper or lowercase, but whichever is used should continue to be used.

-

Leet Substitutes numbers for some letters that are most similar, e.g. 3’s for E’s, 1’s for I’s, etc.

-

StudlyCaps or StickyCaps Random capitalization within a word, or sometimes nonrandom capitalization, but not where it should be, e.g. cAPITALIZING the wrong part of a word because the CAPS LOCK is on.

::

This article is written for users of the following Microsoft Word versions: 97, 2000, 2002, and 2003. If you are using a later version (Word 2007 or later), this tip may not work for you. For a version of this tip written specifically for later versions of Word, click here: Applying the All Caps Format.

Written by Allen Wyatt (last updated March 4, 2023)

This tip applies to Word 97, 2000, 2002, and 2003

Word provides a formatting option to show text as uppercase, even when it is not. You apply this option by choosing the All Caps check box on the Font dialog box. (See Figure 1.) (To display the dialog box, choose Tools | Font.) This formatting feature is helpful if you have a selection you want to print as all uppercase, but you may well decide to convert it back to normal upper- and lowercase text later.

Figure 1. The Font dialog box.

If you use this formatting feature quite a bit, it can get bothersome to continually pull up the Font dialog box and click on the All Caps check box. A faster way is to simply select the text you want to affect and then press Ctrl+Shift+A.

WordTips is your source for cost-effective Microsoft Word training.

(Microsoft Word is the most popular word processing software in the world.)

This tip (1449) applies to Microsoft Word 97, 2000, 2002, and 2003. You can find a version of this tip for the ribbon interface of Word (Word 2007 and later) here: Applying the All Caps Format.

Author Bio

With more than 50 non-fiction books and numerous magazine articles to his credit, Allen Wyatt is an internationally recognized author. He is president of Sharon Parq Associates, a computer and publishing services company. Learn more about Allen…

MORE FROM ALLEN

Turning the Legend On and Off

When you create a chart in Excel, the program may automatically add a legend that explains the contents of the chart. In …

Discover More

Searching Comments

Need to find that misplaced comment in your worksheet? It’s easy to do using the Find and Replace capabilities of Excel.

Discover More

Putting Something in Every Cell of a Table

Need to make sure that all the cells of a table have something in them? It’s easy to do with a handy little macro.

Discover More

Прописная буква. Краткий толковый словарь по полиграфии.2010.

UPPERCASE

режим набора в верхнем регистре, заглавными буквами

UPPERCASE

заголовна; прописна верхнього регістра (про букви)

UPPERCASE

полигр. заглавный, прописной (о литере, шрифте)

UPPERCASE

(UC) заглавная, верхнего регистра (о буквах).

UPPERCASE

(U заглавная, верхнего регистра (о буквах)

UPPERCASE

верхній регістррегістр великих букв

UPPERCASE

UPPERCASE

UPPERCASE ALPHABET

алфавит верхнего регистра

UPPERCASE ALPHABET

алфавит верхнего регистра

UPPERCASE ALPHABET

1) прописной алфавит2) прописной шрифт

UPPERCASE ALPHABET

Прописной алфавит; Прописной шрифт. Краткий толковый словарь по полиграфии.2010.

UPPERCASE BIT

Найстарший (найвищий) біт

UPPERCASE BIT

найстарший (найвищий) біт

UPPERCASE LETTER

Велика буквазнак верхнього регіструбуква верхнього регістру

UPPERCASE LETTER

Велика [заголовна] літера

UPPERCASE LETTER

прописная [заглавная] буква, буква верхнего регистра ср. lowercase letter

UPPERCASE LETTER

1) прописная буква, заглавная буква 2) знак верхнего регистра

UPPERCASE LETTER

прописная (заглавная, большая) буква

UPPERCASE LETTER

прописная [ заглавная ] буква; знак верхнего регистра

UPPERCASE LETTER

UPPERCASE LETTER

прописная (заглавная, большая) буква

UPPERCASE LETTER

велика буквазнак верхнього регістру буква верхнього регістру

UPPERCASE LETTER

UPPERCASE SHIFT

Перемикання (перехід) на верхній регістр

UPPERCASE SHIFT

перемикання (перехід) на верхній регістр

UPPERCASE TOOLS

— front-end tools инструментальные средства [САПР ПО] верхнего уровня (для автоматизации первых этапов разработки) см. тж. lowercase tools

UPPERCASE TOOLS

верхнеуровневые инструментальные средства проектирования (для автоматизации первых этапов разработки ПО в рамках САПР )

UPPERCASE TOOLS

верхнеуровневые инструментальные средства проектирования ( для автоматизации первых этапов разработки ПО в рамках САПР )

Uppercase

Alternatively known as caps and capital, and sometimes abbreviated as UC, uppercase is a typeface of larger characters. For example, typing a, b, and c shows lowercase, and typing A, B, and C shows uppercase. To type in uppercase, you can use either the Caps Lock key or the Shift key on the keyboard.

It’s bad etiquette to have everything you type in ALL UPPERCASE CHARACTERS. When reading anything typed in all caps, most readers assume you are YELLING or find the text hard to read.

When talking about a computer keyboard key, CAPS may be used to label the CapsLock key.

Why is capitalization important?

Passwords

Passwords are case-sensitive to add an extra level of security. If your caps lock key is enabled while creating your password, but not when you log in the next day, you won’t be able to access your account.

File names, directories, and paths

When dealing with file names, directories, and paths in many operating systems and paths, they are case-sensitive. For example, in Microsoft Windows nothing is case-sensitive. However, when uploading a file to the Internet, the files and directories become case-sensitive. For example, the file name of this web page is «uppercase.htm» and must be typed in all lowercase in the URL while online. However, if you were viewing the file locally on a Windows computer, the capitalization would not matter.

Measurements

When dealing with computer measurements and other measurements, capitalization is important for identifying the exact type of measurement. For example, «Mb» (short for megabit) and «MB» (short for megabyte) are two different types of measurements with different values.

Commands

Command line commands in operating systems like Linux are case-sensitive, which means if you typed «Ls» to list file you would get an error since the ls command is all lowercase.

Programming functions

In earlier programming languages like FORTRAN, the keywords and the names of data objects needed to be uppercase because punch card machines did not have a Shift key.

Acronyms

To help differentiate an acronym from other words in a sentence, they are typed in uppercase. For example, the acronym RAM is typed in all uppercase to help identify the word as an acronym.

Using the uc function

Many programming and scripting languages use the uc function to convert a variable into uppercase. For example, in the example below is how the uc and ucfirst functions can be used in Perl.

In the above example, the $example variable is set to all lowercase. The third line uppercases the first character making the text «Hello world,» and the fifth line uppercases the whole string making the text «HELLO WORLD.»

What is the difference between capitalize and uppercase?

Capitalize is used when you’re describing the first letter of a word or a single letter. For example, the first letter in this sentence is capitalized. Uppercase describes a word with every letter being capitalized. For example, the acronym CPU is in uppercase.

When should I capitalize text?

Below is a list of some of the general rules that should be followed when capitalizing words.

- Always capitalize the first word of a sentence.

- If the word is a proper noun or derived from a proper noun, the first letter should be capitalized. For example, a name, book, brand, movie, place, product, and trademark are proper nouns and should be capitalized.

- Capitalize the first letter of a quote unless it is part of the sentence.

- Roads and streets should be capitalized.

- A person’s title (not occupation) before their name should be capitalized.

Below is a list of times capitalization should not be used.

- Never user uppercase for emphasis. Instead, italicize any text you want to emphasize.

- When writing the full form of an acronym, each word of the acronym should be lowercase unless it is a proper noun.

- Do not capitalize the word the when used before a proper noun.

Should titles and headings be capitalized?

With formal writing, the titles and headings should use title case. All other forms of writing should follow the rules set by the used style guide. For example, Computer Hope follows the Microsoft Manual of Style and uses sentence case for its headings.

Should I use «uppercase» or «upper case» in my writing?

Both «uppercase» and «upper case» are correct. However, only use one form in your writing. According to The Associated Press Stylebook and the Microsoft Manual of Style, write «uppercase» as one word when used as an adjective and as a noun.

CSS: заглавные буквы

CSS заглавные буквы помогают разбить монотонность однотипного дизайна, тексты которого выглядят одинаково от начала до конца.

Буквицы раньше и сейчас

Летописцы использовали заглавные буквы в рукописях, которые писались от руки, некоторые из них относятся еще к V веку. Прописные буквы продолжали использоваться с VIII по XV век, когда типографские станки позволили вывести печать на промышленный уровень. И рукописные, и печатные буквицы размещались в начале текста. Часто их украшали декоративным рисунком, который располагался вокруг буквы.

Поднятые и опущенные буквы все еще используются в наши дни. Их можно встретить в газетах, журналах и книгах, а также в цифровой типографии. Поднятые литеры иногда называются вытянутыми. Они размещаются на одном уровне с нижней частью текста, который следует за ними. Опущенные буквы размещаются на одном уровне с верхней частью текста, иногда в слое позади основной части текстового контента, или остальной текст обтекает их.

Поднятые буквы задаются намного проще, так они находятся на одном уровне с остальным текстом, и обычно для этого не нужно менять обтекание внешних полей. Опущенные буквы требуют более тонкой настройки. Вам будет проще разобраться с этим, если сначала вы поймете, как обрабатываются поднятые литеры.

Использование классов

Дизайнеры, которые уже имеют представление о CSS , знают, что нужно создать отдельный класс CSS для первой буквы заглавной.

Код CSS для элемента абзаца и класса, создающего букву, будет выглядеть следующим образом:

А HTML-код будет выглядеть так:

Кажется, слишком просто? На самом деле вам придется вносить коррективы в зависимости от конкретных поднятых букв, так как каждая заглавная литера требует специального кернинга. После выбора шрифта для поднятых букв и для основного текста, нужно создавать отдельные классы для каждой поднятой литеры. В приведенном ниже CSS-классе .myinitialcapsi поле справа имеет отрицательное значение, чтобы уменьшить расстояние между I и n .

В зависимости от разрешения экрана в приведенном выше примере I и n могут выглядеть так, будто они слились вместе. Это происходит из-за засечек на концах букв. Поэтому, прежде чем выбирать окончательный вариант стилей CSS , протестируйте сайт на различных устройствах, чтобы посмотреть, как на них выглядит текст заглавными буквами CSS .

Цитаты и другие частные случаи

Можно увеличить не только буквы в начале текста. Вы можете реализовать еще один класс, чтобы создать увеличенную версию кавычек, которые будут выводиться рядом с буквой. В нашем случае для кавычек не подходит ни класс буквы с размером 48, ни класс текста в 20 пикселей. Скорее, это будет что-то среднее — 30 пикселей. Кавычки мы подвинем вниз на 4 пикселя, чтобы оптически выровнять их с I :

Нужно очень внимательно задавать каждую из CSS заглавных букв вместе с кавычками, чтобы их кернинг и выравнивание соответствовали окружающей разметке. Например, букву Т нужно будет сместить влево, немного за край абзаца, чтобы ее поперечная линия визуально вписывалась в макет. Аналогично нужно будет поступить и с круглыми буквами, такими как C , G , O и Q . В этом примере использованы размеры шрифтов 20, 30 и 48. Но вам нужно будет подобрать размеры, исходя из специфики шрифтов, которые вы выбрали. А также размеров и разрешений экранов, на которых будет просматриваться сайт.

Псевдоэлементы и псевдоклассы

С помощью псевдоэлемента CSS можно легко создать поднятую букву, добавив ::first-letter к элементу абзаца. Используйте :first-letter ( с одним двоеточием ) для устаревших браузеров:

HTML-код , который содержит классы CSS , учитывающие кернинг букв N и B , будет выглядеть следующим образом.

Даже с учетом преимуществ, которые предоставляют псевдоэлементы, нам пришлось добавить много кода, чтобы определить отдельные классы для обработки проблем, связанных с кернингом и отступами. Но этот метод преобразует первую букву каждого нового абзаца в CSS заглавную букву. Для кого-то он может не подойти, потому что не нужно преобразовать первую букву каждого абзаца.

Объединение псевдоклассов и псевдоэлементов для создания смарт-макета

Добавление псевдокласса :first-child помогает решить проблему ненужного преобразования первых букв:

Объединив этот код с HTML :

Преимущество использования псевдоклассов заключается в возможности обрабатывать различные частные случаи. А что насчет недостатков? Существует много различных псевдоклассов, и их можно объединить таким количеством способов, что от этого может пойти кругом голова. Например, псевдоклассы :first-child и :first-of-type могут давать одинаковые результаты. Также можно применить псевдокласс не только к абзацу, но и к элементам <section> или <div>. Например, как показано в приведенном ниже примере с поднятым буквами в шрифте Didot . Обратите внимание, как атрибут margin был добавлен справа от буквы А . Иначе она » склеилась » бы с буквой s в начале раздела:

И вместе с HTML :

Если вы чувствуете тягу к экспериментам, то можете исследовать различные методы в дополнение к :first-child и :first-of-type . Например, такие как :nth-of-type или :nth-of-child , чтобы посмотреть, как те или другие типы псевдоклассов можно использовать для текста заглавными буквами CSS . Независимо от того, будете ли вы следовать изложенным в этой статье принципам или начнете копать глубже, когда вы научитесь работать с псевдоклассами CSS first-child , :first-of-type и :first-letter , вы сможете правильно применять их к элементам HTML .

Подводя черту

Использование отдельных классов вместе с псевдоклассами для обработки различных букв — это процесс проб и ошибок, вычислений положительных и отрицательных отступов. И это требует большого терпения. Для таких букв, как F , G , O , P , Q , T , W , V и Y также потребуются отдельные классы кернинга.

Но самое интересное начинается тогда, когда вы на практике начинаете тестировать различные сочетания шрифтов и создавать поднятые буквы, которые будут привлекать внимание ваших читателей и выделять ваш сайт из общей массы.

Дайте знать, что вы думаете по этой теме материала в комментариях. За комментарии, дизлайки, подписки, отклики, лайки низкий вам поклон!

Quickly convert text to uppercase

Updated on December 19, 2020

When you’re working on a Microsoft Word document and have a string of lowercase text that should be in uppercase, don’t retype it. Instead, use the Word Change Case tool to change some or all of the text to a different case, such as all caps.

Instructions in this article apply to Word for Microsoft 365, Word 2019, Word 2016, Word 2013, and Word 2010.

Microsoft Word Uppercase Shortcut Key

The fastest way to change text to all caps is to highlight the text and press the keyboard shortcut Shift+F3.

Press Ctrl+A to highlight all the text on the page.

You may need to press the shortcut combination a few times because the text in the document might be in another case such as sentence case or all lowercase.

On Word for Mac, select the text you want to change to uppercase, then press ⌘+SHIFT+K.

Change to Uppercase Using the Ribbon

Another way to change the text case is to go to the Home tab on the ribbon.

-

Select the text you want to change to uppercase, then go to the Home tab.

-

In the Font group, select the Change Case drop-down arrow.

-

Choose UPPERCASE to change the selected text to all uppercase letters.

Word Online doesn’t have a shortcut that changes the case of the selected text. Either edit the text manually or open the document in the desktop version of Word to change the case.

Word offers other ways to change the text case:

- Sentence Case: Capitalize the first letter of each selected sentence and change the remaining text to lower case.

- lowercase: Change the selected text to lowercase.

- Capitalize Each Word: Change the first letter of each selected word to uppercase format.

- tOGGLE cASE: Change the first letter of every word to lowercase and the remaining letters to uppercase.

Any time you change the case format of text in Word, use the Ctrl+Z shortcut to undo it.

Don’t Have Microsoft Word?

Though it’s simple to do this in Microsoft Word, you don’t have to use Word to change the text to all caps. There are online services that perform the same function. For example, go to the Convert Case website or Capitalize My Title website and paste the text into the text field and choose from a variety of cases. Select from uppercase, lowercase, sentence case, capitalized case, alternating case, title case, and inverse case. After the conversion, copy the text and paste it where you need it.

Thanks for letting us know!

Get the Latest Tech News Delivered Every Day

Subscribe

Sandy G

-

#1

For some reason my keyboard has started typing in all caps. I can’t get an

apostrophe it shows the quote marks instead. I checked in Word-Tools-Options

and the all caps is not checked in word. Please help asap. Thank you.

Advertisements

Bob I

Another Brian

-

#3

Make sure that the caps lock key is not stuck in the down position.

Sandy G

-

#4

It doesn’t appear it is stuck in the down position.

Bob I

-

#5

If you press the number keys across the top of the keyboard what do you

get? If not numbers, then check the Accessibility options in Control

Panel for Sticky Keys set to lock on, otherwise the Shift key is shorted

or broken.

Sandy G

-

#6

Thanks Bob. The number key pad won’t work. The num lock is on but the

numbers won’t work. I kind of suspected it may be the keyboard. I’ll swap

out keyboards and see what happens. Thanks.

Advertisements

Bob I

-

#7

You’re welcome, have a good day.

Want to reply to this thread or ask your own question?

You’ll need to choose a username for the site, which only take a couple of moments. After that, you can post your question and our members will help you out.

Ask a Question

RH24

-

#1

Microsoft Word 2003 seems to want to type in all caps. The caps lock button

is not on, but it’s still typing in caps!

Does anyone know what I can do?!

Advertisements

Herb Tyson [MVP]

-

#2

It could be that the font setting is set to All caps (or Small caps). Press

Ctrl+D and see if either of those is checked.

If either is checked, and if the problem is happening all the time, then you

probably accidentally changed the default. Remove the check(s), then click

Default in the Font dialog box.

Graham Mayor

-

#3

Or you could have an all Capitals font set as default font.

—

<>>< ><<> ><<> <>>< ><<> <>>< <>><<>

Graham Mayor — Word MVP

My web site www.gmayor.com

<>>< ><<> ><<> <>>< ><<> <>>< <>><<>

Advertisements

jia.khangura

-

#4

Thank you. It worked for me.

Want to reply to this thread or ask your own question?

You’ll need to choose a username for the site, which only take a couple of moments. After that, you can post your question and our members will help you out.

Ask a Question

The lower-case «a» and upper-case «A» are the two case variants of the first letter in the English alphabet.

Letter case is the distinction between the letters that are in larger uppercase or capitals (or more formally majuscule) and smaller lowercase (or more formally minuscule) in the written representation of certain languages. The writing systems that distinguish between the upper and lowercase have two parallel sets of letters, with each letter in one set usually having an equivalent in the other set. The two case variants are alternative representations of the same letter: they have the same name and pronunciation and are treated identically when sorting in alphabetical order.

Letter case is generally applied in a mixed-case fashion, with both upper and lowercase letters appearing in a given piece of text for legibility. The choice of case is often prescribed by the grammar of a language or by the conventions of a particular discipline. In orthography, the uppercase is primarily reserved for special purposes, such as the first letter of a sentence or of a proper noun (called capitalisation, or capitalised words), which makes the lowercase the more common variant in regular text.

In some contexts, e.g., academic, it is conventional to use one case only. For example, engineering design drawings are typically labelled entirely in uppercase letters, which are easier to distinguish individually than the lowercase when space restrictions require that the lettering be very small. In mathematics, on the other hand, uppercase and lower case letters denote generally different mathematical objects, which may be related when the two cases of the same letter are used; for example, x may denote an element of a set X.

Terminology[edit]

Divided upper and lower type cases with cast metal sorts

Layout for type cases

The terms upper case and lower case may be written as two consecutive words, connected with a hyphen (upper-case and lower-case – particularly if they pre-modify another noun[1]), or as a single word (uppercase and lowercase). These terms originated from the common layouts of the shallow drawers called type cases used to hold the movable type for letterpress printing. Traditionally, the capital letters were stored in a separate shallow tray or «case» that was located above the case that held the small letters.[2][3]

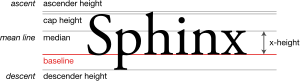

Majuscule (, less commonly ), for palaeographers, is technically any script whose letters have very few or very short ascenders and descenders, or none at all (for example, the majuscule scripts used in the Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209, or the Book of Kells). By virtue of their visual impact, this made the term majuscule an apt descriptor for what much later came to be more commonly referred to as uppercase letters.

Minuscule refers to lower-case letters. The word is often spelled miniscule, by association with the unrelated word miniature and the prefix mini-. This has traditionally been regarded as a spelling mistake (since minuscule is derived from the word minus[4]), but is now so common that some dictionaries tend to accept it as a nonstandard or variant spelling.[5] Miniscule is still less likely, however, to be used in reference to lower-case letters.

Typographical considerations[edit]

The glyphs of lowercase letters can resemble smaller forms of the uppercase glyphs restricted to the baseband (e.g. «C/c» and «S/s», cf. small caps) or can look hardly related (e.g. «D/d» and «G/g»). Here is a comparison of the upper and lower case variants of each letter included in the English alphabet (the exact representation will vary according to the typeface and font used):

| Uppercase | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowercase | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

(Some lowercase letters have variations e.g. a/ɑ)

Typographically, the basic difference between the majuscules and minuscules is not that the majuscules are big and minuscules small, but that the majuscules generally have the same height (although, depending on the typeface, there may be some exceptions, particularly with Q and sometimes J having a descending element; also, various diacritics can add to the normal height of a letter).

Ascenders (as in «h») and descenders (as in «p») make the height of lower-case letters vary.

There is more variation in the height of the minuscules, as some of them have parts higher (ascenders) or lower (descenders) than the typical size. Normally, b, d, f, h, k, l, t [note 1] are the letters with ascenders, and g, j, p, q, y are the ones with descenders. In addition, with old-style numerals still used by some traditional or classical fonts, 6 and 8 make up the ascender set, and 3, 4, 5, 7 and 9 the descender set.

Bicameral script[edit]

Adyghe Latin alphabet, used between 1927 and 1938, was based on Latin script, but did not have capital letters, being unicameral (small caps include ᴀ, ʙ, ᴣ, ʀ, ⱪ, ᴘ, and .

A minority of writing systems use two separate cases. Such writing systems are called bicameral scripts. Languages that use the Latin, Cyrillic, Greek, Coptic, Armenian, Adlam, Warang Citi, Cherokee, Garay, Zaghawa, and Osage scripts use letter cases in their written form as an aid to clarity. Another bicameral script, which is not used for any modern languages, is Deseret. The Georgian alphabet has several variants, and there were attempts to use them as different cases, but the modern written Georgian language does not distinguish case.[7]

All other writing systems make no distinction between majuscules and minuscules – a system called unicameral script or unicase. This includes most syllabic and other non-alphabetic scripts.

In scripts with a case distinction, lowercase is generally used for the majority of text; capitals are used for capitalisation and emphasis when bold is not available. Acronyms (and particularly initialisms) are often written in all-caps, depending on various factors.

Capitalisation[edit]

Capitalisation is the writing of a word with its first letter in uppercase and the remaining letters in lowercase. Capitalisation rules vary by language and are often quite complex, but in most modern languages that have capitalisation, the first word of every sentence is capitalised, as are all proper nouns.[citation needed]

Capitalisation in English, in terms of the general orthographic rules independent of context (e.g. title vs. heading vs. text), is universally standardised for formal writing. Capital letters are used as the first letter of a sentence, a proper noun, or a proper adjective. The names of the days of the week and the names of the months are also capitalised, as are the first-person pronoun «I»[8] and the vocative particle «O». There are a few pairs of words of different meanings whose only difference is capitalisation of the first letter. Honorifics and personal titles showing rank or prestige are capitalised when used together with the name of the person (for example, «Mr. Smith», «Bishop O’Brien», «Professor Moore») or as a direct address, but normally not when used alone and in a more general sense.[9][10] It can also be seen as customary to capitalise any word – in some contexts even a pronoun[11] – referring to the deity of a monotheistic religion.

Other words normally start with a lower-case letter. There are, however, situations where further capitalisation may be used to give added emphasis, for example in headings and publication titles (see below). In some traditional forms of poetry, capitalisation has conventionally been used as a marker to indicate the beginning of a line of verse independent of any grammatical feature. In political writing, parody and satire, the unexpected emphasis afforded by otherwise ill-advised capitalisation is often used to great stylistic effect, such as in the case of George Orwell’s Big Brother.

Other languages vary in their use of capitals. For example, in German all nouns are capitalised (this was previously common in English as well, mainly in the 17th and 18th centuries), while in Romance and most other European languages the names of the days of the week, the names of the months, and adjectives of nationality, religion, and so on normally begin with a lower-case letter.[12] On the other hand, in some languages it is customary to capitalise formal polite pronouns, for example De, Dem (Danish), Sie, Ihnen (German), and Vd or Ud (short for usted in Spanish).

Informal communication, such as texting, instant messaging or a handwritten sticky note, may not bother to follow the conventions concerning capitalisation, but that is because its users usually do not expect it to be formal.[8]

Exceptional letters and digraphs[edit]

- The German letter «ß» formerly existed only in lower case. The orthographical capitalisation does not concern «ß», which generally does not occur at the beginning of a word, and in the all-caps style it has traditionally been replaced by the digraph «SS». Since June 2017, however, capital ẞ is accepted as an alternative in the all-caps style.[13]

- The Greek upper-case letter «Σ» has two different lower-case forms: «ς» in word-final position and «σ» elsewhere. In a similar manner, the Latin upper-case letter «S» used to have two different lower-case forms: «s» in word-final position and » ſ » elsewhere. The latter form, called the long s, fell out of general use before the middle of the 19th century, except for the countries that continued to use blackletter typefaces such as Fraktur. When blackletter type fell out of general use in the mid-20th century, even those countries dropped the long s.[citation needed]

- The treatment of the Greek iota subscript with upper-case letters is complicated.

- Unlike most languages that use Latin-script and link the dotless upper-case «I» with the dotted lower-case «i», Turkish as well as some forms of Azeri have both a dotted and dotless I, each in both upper and lower case. Each of the two pairs («İ/i» and «I/ı») represents a distinctive phoneme.

- In some languages, specific digraphs may be regarded as single letters, and in Dutch, the digraph «IJ/ij» is even capitalised with both components written in uppercase (for example, «IJsland» rather than «Ijsland»).[14] In other languages, such as Welsh and Hungarian, various digraphs are regarded as single letters for collation purposes, but the second component of the digraph will still be written in lower case even if the first component is capitalised. Similarly, in South Slavic languages whose orthography is coordinated between the Cyrillic and Latin scripts, the Latin digraphs «Lj/lj», «Nj/nj» and «Dž/dž» are each regarded as a single letter (like their Cyrillic equivalents «Љ/љ», «Њ/њ» and «Џ/џ», respectively), but only in all-caps style should both components be in upper case (e.g. Ljiljan–LJILJAN, Njonja–NJONJA, Džidža–DŽIDŽA).[citation needed] Unicode designates a single character for each case variant (i.e., upper case, title case and lower case) of the three digraphs.[15]

- Some English surnames such as fforbes are traditionally spelt with a digraph instead of a capital letter (at least for ff).

- In the Hawaiian orthography, the ʻokina is a phonemic symbol that visually resembles a left single quotation mark. Representing the glottal stop, the ʻokina can be characterised as either a letter[16] or a diacritic.[17] As a unicase letter, the ʻokina is unaffected by capitalisation; it is the following letter that is capitalised instead. According to the Unicode standard, the ʻokina is formally encoded as U+02BB ʻ MODIFIER LETTER TURNED COMMA,[18] but it is not uncommon to substitute this with a similar punctuation character, such as the left single quotation mark or an apostrophe.[19]

[edit]

Similar orthographic and graphostylistic conventions are used for emphasis or following language-specific or other rules, including:

- Font effects such as italic type or oblique type, boldface, and choice of serif vs. sans-serif.

- In mathematical notation lower-case and upper-case letters have generally different meanings, and other meanings can be implied by the use of other typefaces, such as boldface, fraktur, script typeface, and blackboard bold.

- Some letters of the Arabic and Hebrew alphabets and some jamo of the Korean hangul have different forms depending on placement within a word, but these rules are strict and the different forms cannot be used for emphasis.

- In the Arabic and Arabic-based alphabets, letters in a word are connected, except for several that cannot connect to the following letter. Letters may have distinct forms depending on whether they are initial (connected only to the following letter), medial (connected to both neighboring letters), final (connected only to the preceding letter), or isolated (connected to neither a preceding nor a following letter).

- In the Hebrew alphabet, five letters have a distinct form (see Final form) that is used when they are word-final.

- In Georgian, some authors use isolated letters from the ancient Asomtavruli alphabet within a text otherwise written in the modern Mkhedruli in a fashion that is reminiscent of the usage of upper-case letters in the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets.

- In the Japanese writing system, an author has the option of switching between kanji, hiragana, katakana, and rōmaji. In particular, every hiragana character has an equivalent katakana character, and vice versa. Romanised Japanese sometimes uses lowercase letters to represent words that would be written in hiragana, and uppercase letters to represent words that would be written in katakana. Some kana characters are written in smaller type when they modify or combine with the preceding sign (yōon) or the following sign (sokuon).

Stylistic or specialised usage[edit]

In English, a variety of case styles are used in various circumstances:

- Sentence case

- «The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog»

A mixed-case style in which the first word of the sentence is capitalised, as well as proper nouns and other words as required by a more specific rule. This is generally equivalent to the baseline universal standard of formal English orthography. - In computer programming, the initial capital is easier to automate than the other rules. For example, on English-language Wikipedia, the first character in page titles is capitalised by default. Because the other rules are more complex, substrings for concatenation into sentences are commonly written in «mid-sentence case», applying all the rules of sentence case except the initial capital.

- Title case (capital case, headline style)

- «The Quick Brown Fox Jumps over the Lazy Dog»

A mixed-case style with all words capitalised, except for certain subsets (particularly articles and short prepositions and conjunctions) defined by rules that are not universally standardised. The standardisation is only at the level of house styles and individual style manuals. (See further explanation below at § Headings and publication titles.) - Start case (First letter of each word capitalized)

- «The Quick Brown Fox Jumps Over The Lazy Dog»

Start case or initial caps is a simplified variant of title case. In text processing, title case usually involves the capitalisation of all words irrespective of their part of speech. - All caps (all uppercase)

- «THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG»

A unicase style with capital letters only. This can be used in headings and special situations, such as for typographical emphasis in text made on a typewriter. With the advent of the Internet, the all-caps style is more often used for emphasis; however, it is considered poor netiquette by some to type in all capitals, and said to be tantamount to shouting.[20] Long spans of Latin-alphabet text in all upper-case are more difficult to read because of the absence of the ascenders and descenders found in lower-case letters, which aids recognition and legibility. In some cultures it is common to write family names in all caps to distinguish them from the given names, especially in identity documents such as passports. Certain musicians—such as Willow and Finneas, who are both known mononymously—have their names stylised in all caps. Additionally, it is common for bands with vowelless names (a process colourfully known as «disemvoweling») to use all caps, a trend that was possibly started by indie rock band MGMT. Other prominent examples include STRFKR, MSTRKRFT, PWR BTTM, SBTRKT, JPNSGRLS (now known as Hotel Mira), BLK JKS, MNDR, and DWNTWN. - Small caps

- «The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog«

Similar in form to capital letters but roughly the size of a lower-case «x», small caps can be used instead of lower-case letters and combined with regular caps in a mixed-case fashion. This is a feature of certain fonts, such as Copperplate Gothic. According to various typographical traditions, the height of small caps can be equal to or slightly larger than the x-height of the typeface (the smaller variant is sometimes called petite caps and may also be mixed with the larger variant).[21] Small caps can be used for acronyms, names, mathematical entities, computer commands in printed text, business or personal printed stationery letterheads, and other situations where a given phrase needs to be distinguished from the main text. - All lowercase

- «the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog»

- A unicase style with no capital letters. This is sometimes used for artistic effect, such as in poetry. Also commonly seen in computer languages, and in informal electronic communications such as SMS language and instant messaging (avoiding the shift key, to type more quickly). Examples in music are relatively common. For example, several of Taylor Swift’s albums, including reputation, folklore, and evermore, were all stylised in lowercase. Bands such as Weezer and Silverchair were also stylised in lowercase for multiple albums during their respective careers, with the former consistently using lowercase in their logo since their first studio album. Billie Eilish’s debut studio album—When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?—has all of its tracks stylised in lowercase.

| Case style | Example | Description | |||||||

| All-caps | THE | VITAMINS | ARE | IN | MY | FRESH | CALIFORNIA | RAISINS | All letters uppercase |

| Start case | The | Vitamins | Are | In | My | Fresh | California | Raisins | All words capitalised regardless of function |

| Title case | The | Vitamins | Are | in | My | Fresh | California | Raisins | The first word and all other words capitalised except for articles and short prepositions and conjunctions |

| German-style sentence case | The | Vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | California | Raisins | The first word and all nouns capitalised |

| Sentence case | The | vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | California | raisins | The first word, proper nouns and some specified words capitalised |

| Mid-sentence case | the | vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | California | raisins | As above but excepting special treatment of the first word |

| All-lowercase | the | vitamins | are | in | my | fresh | california | raisins | All letters lowercase (unconventional in English prose) |

Headings and publication titles[edit]

In English-language publications, various conventions are used for the capitalisation of words in publication titles and headlines, including chapter and section headings. The rules differ substantially between individual house styles.

The convention followed by many British publishers (including scientific publishers like Nature and New Scientist, magazines like The Economist, and newspapers like The Guardian and The Times) and many U.S. newspapers is sentence-style capitalisation in headlines, i.e. capitalisation follows the same rules that apply for sentences. This convention is usually called sentence case. It may also be applied to publication titles, especially in bibliographic references and library catalogues. An example of a global publisher whose English-language house style prescribes sentence-case titles and headings is the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

For publication titles it is, however, a common typographic practice among both British[22] and U.S. publishers to capitalise significant words (and in the United States, this is often applied to headings, too). This family of typographic conventions is usually called title case. For example, R. M. Ritter’s Oxford Manual of Style (2002) suggests capitalising «the first word and all nouns, pronouns, adjectives, verbs and adverbs, but generally not articles, conjunctions and short prepositions».[23] This is an old form of emphasis, similar to the more modern practice of using a larger or boldface font for titles. The rules which prescribe which words to capitalise are not based on any grammatically inherent correct–incorrect distinction and are not universally standardised; they differ between style guides, although most style guides tend to follow a few strong conventions, as follows:

- Most styles capitalise all words except for short closed-class words (certain parts of speech, namely, articles, prepositions, and conjunctions); but the first word (always) and last word (in many styles) are also capitalised, regardless of their part of speech. Many styles capitalise longer prepositions such as «between» and «throughout», but not shorter ones such as «for» and «with».[24] Typically, a preposition is considered short if it has up to three or four letters.

- A few styles capitalise all words in title case (the so-called start case), which has the advantage of being easy to implement and hard to get «wrong» (that is, «not edited to style»). Because of this rule’s simplicity, software case-folding routines can handle 95% or more of the editing, especially if they are programmed for desired exceptions (such as «FBI» rather than «Fbi»).

- As for whether hyphenated words are capitalised not only at the beginning but also after the hyphen, there is no universal standard; variation occurs in the wild and among house styles (e.g., «The Letter-Case Rule in My Book»; «Short-term Follow-up Care for Burns»). Traditional copyediting makes a distinction between temporary compounds (such as many nonce [novel instance] compound modifiers), in which every part of the hyphenated word is capitalised (e.g. «How This Particular Author Chose to Style His Autumn-Apple-Picking Heading»), and permanent compounds, which are terms that, although compound and hyphenated, are so well established that dictionaries enter them as headwords (e.g., «Short-term Follow-up Care for Burns»).

Title case is widely used in many English-language publications, especially in the United States. However, its conventions are sometimes not followed strictly – especially in informal writing.

In creative typography, such as music record covers and other artistic material, all styles are commonly encountered, including all-lowercase letters and special case styles, such as studly caps (see below). For example, in the wordmarks of video games it is not uncommon to use stylised upper-case letters at the beginning and end of a title, with the intermediate letters in small caps or lower case (e.g., ArcaniA, ArmA, and DmC).

Multi-word proper nouns[edit]

Single-word proper nouns are capitalised in formal written English, unless the name is intentionally stylised to break this rule (such as the first or last name of danah boyd).

Multi-word proper nouns include names of organisations, publications, and people. Often the rules for «title case» (described in the previous section) are applied to these names, so that non-initial articles, conjunctions, and short prepositions are lowercase, and all other words are uppercase. For example, the short preposition «of» and the article «the» are lowercase in «Steering Committee of the Finance Department». Usually only capitalised words are used to form an acronym variant of the name, though there is some variation in this.

With personal names, this practice can vary (sometimes all words are capitalised, regardless of length or function), but is not limited to English names. Examples include the English names Tamar of Georgia and Catherine the Great, «van» and «der» in Dutch names, «von» and «zu» in German, «de», «los», and «y» in Spanish names, «de» or «d'» in French names, and «ibn» in Arabic names.

Some surname prefixes also affect the capitalisation of the following internal letter or word, for example «Mac» in Celtic names and «Al» in Arabic names.

Unit symbols and prefixes in the metric system[edit]

In the International System of Units (SI), a letter usually has different meanings in upper and lower case when used as a unit symbol. Generally, unit symbols are written in lower case, but if the name of the unit is derived from a proper noun, the first letter of the symbol is capitalised. Nevertheless, the name of the unit, if spelled out, is always considered a common noun and written accordingly in lower case.[25] For example:

- 1 s (one second) when used for the base unit of time.

- 1 S (one siemens) when used for the unit of electric conductance and admittance (named after Werner von Siemens).

- 1 Sv (one sievert), used for the unit of ionising radiation dose (named after Rolf Maximilian Sievert).

For the purpose of clarity, the symbol for litre can optionally be written in upper case even though the name is not derived from a proper noun.[25] For example, «one litre» may be written as:

- 1 l, the original form, for typefaces in which «digit one» ⟨1⟩, «lower-case ell» ⟨l⟩, and «upper-case i» ⟨I⟩ look different.

- 1 L, an alternative form, for typefaces in which these characters are difficult to distinguish, or the typeface the reader will be using is unknown. A «script l» in various typefaces (e.g.: 1 l) has traditionally been used in some countries to prevent confusion; however, the separate Unicode character which represents this, U+2113 ℓ SCRIPT SMALL L, is deprecated by the SI.[26] Another solution sometimes seen in Web typography is to use a serif font for «lower-case ell» in otherwise sans-serif material (1 l).

The letter case of a prefix symbol is determined independently of the unit symbol to which it is attached. Lower case is used for all submultiple prefix symbols and the small multiple prefix symbols up to «k» (for kilo, meaning 103 = 1000 multiplier), whereas upper case is used for larger multipliers:[25]

- 1 ms, millisecond, a small measure of time («m» for milli, meaning 10−3 = 1/1000 multiplier).

- 1 Ms, megasecond, a large measure of time («M» for mega, meaning 106 = 1 000 000 multiplier).

- 1 mS, millisiemens, a small measure of electric conductance.

- 1 MS, megasiemens, a large measure of electric conductance.

- 1 mm, millimetre, a small measure of length.

- 1 Mm, megametre, a large measure of length.

Use within programming languages[edit]

Some case styles are not used in standard English, but are common in computer programming, product branding, or other specialised fields.

The usage derives from how programming languages are parsed, programmatically. They generally separate their syntactic tokens by simple whitespace, including space characters, tabs, and newlines. When the tokens, such as function and variable names start to multiply in complex software development, and there is still a need to keep the source code human-readable, Naming conventions make this possible. So for example, a function dealing with matrix multiplication might formally be called:

- SGEMM(*), with the asterisk standing in for an equally inscrutable list of 13 parameters (in BLAS),

- MultiplyMatrixByMatrix(Matrix x, Matrix y), in some hypothetical higher level manifestly typed language, broadly following the syntax of C++ or Java,

- multiply-matrix-by-matrix(x, y) in something derived from LISP, or perhaps

- (multiply (x y)) in the CLOS, or some newer derivative language supporting type inference and multiple dispatch.

In each case, the capitalisation or lack thereof supports a different function. In the first, FORTRAN compatibility requires case-insensitive naming and short function names. The second supports easily discernible function and argument names and types, within the context of an imperative, strongly typed language. The third supports the macro facilities of LISP, and its tendency to view programs and data minimalistically, and as interchangeable. The fourth idiom needs much less syntactic sugar overall, because much of the semantics are implied, but because of its brevity and so lack of the need for capitalization or multipart words at all, might also make the code too abstract and overloaded for the common programmer to understand.

Understandably then, such coding conventions are highly subjective, and can lead to rather opinionated debate, such as in the case of editor wars, or those about indent style. Capitalisation is no exception.

Camel case[edit]

Camel case: «theQuickBrownFoxJumpsOverTheLazyDog» or «TheQuickBrownFoxJumpsOverTheLazyDog»

Spaces and punctuation are removed and the first letter of each word is capitalised. If this includes the first letter of the first word (CamelCase, «PowerPoint», «TheQuick…», etc.), the case is sometimes called upper camel case (or, illustratively, CamelCase), Pascal case in reference to the Pascal programming language[27] or bumpy case.

When the first letter of the first word is lowercase («iPod», «eBay», «theQuickBrownFox…»), the case is usually known as lower camel case or dromedary case (illustratively: dromedaryCase). This format has become popular in the branding of information technology products and services, with an initial «i» meaning «Internet» or «intelligent»[citation needed], as in iPod, or an initial «e» meaning «electronic», as in email (electronic mail) or e-commerce (electronic commerce).

Snake case[edit]

Snake case: «the_quick_brown_fox_jumps_over_the_lazy_dog»

Punctuation is removed and spaces are replaced by single underscores. Normally the letters share the same case (e.g. «UPPER_CASE_EMBEDDED_UNDERSCORE» or «lower_case_embedded_underscore») but the case can be mixed, as in OCaml variant constructors (e.g. «Upper_then_lowercase»).[28] The style may also be called pothole case, especially in Python programming, in which this convention is often used for naming variables. Illustratively, it may be rendered snake_case, pothole_case, etc. When all-upper-case, it may be referred to as screaming snake case (or SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE) or hazard case.[29]

Kebab case[edit]

Kebab case: «the-quick-brown-fox-jumps-over-the-lazy-dog»

Similar to snake case, above, except hyphens rather than underscores are used to replace spaces. It is also known as spinal case, param case, Lisp case in reference to the Lisp programming language, or dash case (or illustratively as kebab-case). If every word is capitalised, the style is known as train case (TRAIN-CASE).[citation needed]

In CSS, all property names and most keyword values are primarily formatted in kebab case.

Studly caps[edit]

Studly caps: e.g. «tHeqUicKBrOWnFoXJUmpsoVeRThElAzydOG»

Mixed case with no semantic or syntactic significance to the use of the capitals. Sometimes only vowels are upper case, at other times upper and lower case are alternated, but often it is simply random. The name comes from the sarcastic or ironic implication that it was used in an attempt by the writer to convey their own coolness (studliness).[citation needed] It is also used to mock the violation of standard English case conventions by marketers in the naming of computer software packages, even when there is no technical requirement to do so – e.g., Sun Microsystems’ naming of a windowing system NeWS. Illustrative naming of the style is, naturally, random: stUdlY cAps, StUdLy CaPs, etc.

Case folding and case conversion[edit]

In the character sets developed for computing, each upper- and lower-case letter is encoded as a separate character. In order to enable case folding and case conversion, the software needs to link together the two characters representing the case variants of a letter. (Some old character-encoding systems, such as the Baudot code, are restricted to one set of letters, usually represented by the upper-case variants.)

Case-insensitive operations can be said to fold case, from the idea of folding the character code table so that upper- and lower-case letters coincide. The conversion of letter case in a string is common practice in computer applications, for instance to make case-insensitive comparisons. Many high-level programming languages provide simple methods for case conversion, at least for the ASCII character set.

Whether or not the case variants are treated as equivalent to each other varies depending on the computer system and context. For example, user passwords are generally case sensitive in order to allow more diversity and make them more difficult to break. In contrast, case is often ignored in keyword searches in order to ignore insignificant variations in keyword capitalisation both in queries and queried material.

Unicode case folding and script identification[edit]

Unicode defines case folding through the three case-mapping properties of each character: upper case, lower case, and title case (in this context, «title case» relates to ligatures and digraphs encoded as mixed-case single characters, in which the first component is in upper case and the second component in lower case[30]). These properties relate all characters in scripts with differing cases to the other case variants of the character.

As briefly discussed in Unicode Technical Note #26,[31] «In terms of implementation issues, any attempt at a unification of Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic would wreak havoc [and] make casing operations an unholy mess, in effect making all casing operations context sensitive […]». In other words, while the shapes of letters like A, B, E, H, K, M, O, P, T, X, Y and so on are shared between the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets (and small differences in their canonical forms may be considered to be of a merely typographical nature), it would still be problematic for a multilingual character set or a font to provide only a single code point for, say, uppercase letter B, as this would make it quite difficult for a wordprocessor to change that single uppercase letter to one of the three different choices for the lower-case letter, the Latin b (U+0062), Greek β (U+03B2) or Cyrillic в (U+0432). Therefore, the corresponding Latin, Greek and Cyrillic upper-case letters (U+0042, U+0392 and U+0412, respectively) are also encoded as separate characters, despite their appearance being identical. Without letter case, a «unified European alphabet» – such as ABБCГDΔΕЄЗFΦGHIИJ…Z, with an appropriate subset for each language – is feasible; but considering letter case, it becomes very clear that these alphabets are rather distinct sets of symbols.

Methods in word processing[edit]

Most modern word processors provide automated case conversion with a simple click or keystroke. For example, in Microsoft Office Word, there is a dialog box for toggling the selected text through UPPERCASE, then lowercase, then Title Case (actually start caps; exception words must be lowercased individually). The keystroke ⇧ Shift+F3 does the same thing.

Methods in programming[edit]

In some forms of BASIC there are two methods for case conversion:

UpperA$ = UCASE$("a") LowerA$ = LCASE$("A")

C and C++, as well as any C-like language that conforms to its standard library, provide these functions in the file ctype.h:

char upperA = toupper('a'); char lowerA = tolower('A');

Case conversion is different with different character sets. In ASCII or EBCDIC, case can be converted in the following way, in C:

int toupper(int c) { return islower(c) ? c – 'a' + 'A' : c; } int tolower(int c) { return isupper(c) ? c – 'A' + 'a' : c; }

This only works because the letters of upper and lower cases are spaced out equally. In ASCII they are consecutive, whereas with EBCDIC they are not; nonetheless the upper-case letters are arranged in the same pattern and with the same gaps as are the lower-case letters, so the technique still works.

Some computer programming languages offer facilities for converting text to a form in which all words are capitalised. Visual Basic calls this «proper case»; Python calls it «title case». This differs from usual title casing conventions, such as the English convention in which minor words are not capitalised.

History[edit]

Papyrus fragment with old Roman cursive script from the reign of Claudius (41–54 CE)

Combined case with capital letters above small letters

Late 19th-century mixed cases

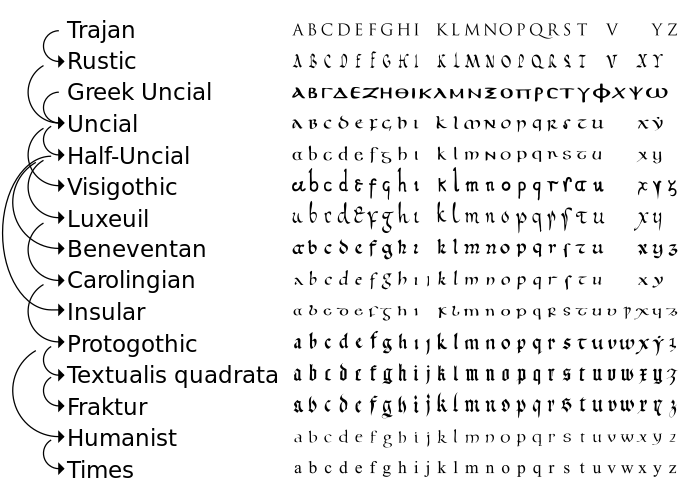

Originally alphabets were written entirely in majuscule letters, spaced between well-defined upper and lower bounds. When written quickly with a pen, these tended to turn into rounder and much simpler forms. It is from these that the first minuscule hands developed, the half-uncials and cursive minuscule, which no longer stayed bound between a pair of lines.[32] These in turn formed the foundations for the Carolingian minuscule script, developed by Alcuin for use in the court of Charlemagne, which quickly spread across Europe. The advantage of the minuscule over majuscule was improved, faster readability.[citation needed]

In Latin, papyri from Herculaneum dating before 79 CE (when it was destroyed) have been found that have been written in old Roman cursive, where the early forms of minuscule letters «d», «h» and «r», for example, can already be recognised. According to papyrologist Knut Kleve, «The theory, then, that the lower-case letters have been developed from the fifth century uncials and the ninth century Carolingian minuscules seems to be wrong.»[33] Both majuscule and minuscule letters existed, but the difference between the two variants was initially stylistic rather than orthographic and the writing system was still basically unicameral: a given handwritten document could use either one style or the other but these were not mixed. European languages, except for Ancient Greek and Latin, did not make the case distinction before about 1300.[citation needed]

The timeline of writing in Western Europe can be divided into four eras:[citation needed]

- Greek majuscule (9th–3rd century BCE) in contrast to the Greek uncial script (3rd century BCE – 12th century CE) and the later Greek minuscule

- Roman majuscule (7th century BCE – 4th century CE) in contrast to the Roman uncial (4th–8th century CE), Roman half uncial, and minuscule

- Carolingian majuscule (4th–8th century CE) in contrast to the Carolingian minuscule (around 780 – 12th century)

- Gothic majuscule (13th and 14th century), in contrast to the early Gothic (end of 11th to 13th century), Gothic (14th century), and late Gothic (16th century) minuscules.

Traditionally, certain letters were rendered differently according to a set of rules. In particular, those letters that began sentences or nouns were made larger and often written in a distinct script. There was no fixed capitalisation system until the early 18th century. The English language eventually dropped the rule for nouns, while the German language keeps it.

Similar developments have taken place in other alphabets. The lower-case script for the Greek alphabet has its origins in the 7th century and acquired its quadrilinear form (that is, characterised by ascenders and descenders[34]) in the 8th century. Over time, uncial letter forms were increasingly mixed into the script. The earliest dated Greek lower-case text is the Uspenski Gospels (MS 461) in the year 835.[35] The modern practice of capitalising the first letter of every sentence seems to be imported (and is rarely used when printing Ancient Greek materials even today).[citation needed]

Simplified relationship between various scripts leading to the development of modern lower case of standard Latin alphabet and that of the modern variants Fraktur (used in Germany until 1940s) and Gaelic (used in Ireland). Several scripts coexisted such as half-uncial and uncial, which derive from Roman cursive and Greek uncial, and Visigothic, Merovingian (Luxeuil variant here) and Beneventan. The Carolingian script was the basis for blackletter and humanist minuscule. What is commonly called «Gothic writing» is technically called blackletter (here textualis quadrata) and is completely unrelated to Visigothic script. The letter j is i with a flourish, u and v are the same letter in early scripts and were used depending on their position in insular half-uncial and caroline minuscule and later scripts, w is a ligature of vv, in insular the rune wynn is used as a w (three other runes in use were the thorn (þ), ʻféʼ (ᚠ) as an abbreviation for cattle/goods and maðr (ᛘ) for man). The letters y and z were very rarely used, in particular þ was written identically to y so y was dotted to avoid confusion, the dot was adopted for i only after late-caroline (protogothic), in beneventan script the macron abbreviation featured a dot above. Lost variants such as r rotunda, ligatures and scribal abbreviation marks are omitted; long s is shown when no terminal s (the only variant used today) is preserved from a given script. Humanist script was the basis for Venetian types which changed little until today, such as Times New Roman (a serifed typeface).

Type cases[edit]

The individual type blocks used in hand typesetting are stored in shallow wooden or metal drawers known as «type cases». Each is subdivided into a number of compartments («boxes») for the storage of different individual letters.[citation needed]

The Oxford Universal Dictionary on Historical Advanced Proportional Principles (reprinted 1952) indicates that case in this sense (referring to the box or frame used by a compositor in the printing trade) was first used in English in 1588. Originally one large case was used for each typeface, then «divided cases», pairs of cases for majuscules and minuscules, were introduced in the region of today’s Belgium by 1563, England by 1588, and France before 1723.

The terms upper and lower case originate from this division. By convention, when the two cases were taken out of the storage rack and placed on a rack on the compositor’s desk, the case containing the capitals and small capitals stood at a steeper angle at the back of the desk, with the case for the small letters, punctuation, and spaces being more easily reached at a shallower angle below it to the front of the desk, hence upper and lower case.[36]

Though pairs of cases were used in English-speaking countries and many European countries in the seventeenth century, in Germany and Scandinavia the single case continued in use.[36]

Various patterns of cases are available, often with the compartments for lower-case letters varying in size according to the frequency of use of letters, so that the commonest letters are grouped together in larger boxes at the centre of the case.[36] The compositor takes the letter blocks from the compartments and places them in a composing stick, working from left to right and placing the letters upside down with the nick to the top, then sets the assembled type in a galley.[36]

See also[edit]

- All caps

- Alternating caps

- Camel case

- Capitalization

- Capitalization in English

- Initial, or drop cap

- Grammatical case

- Punctuation

- Roman cursive

- Roman square capitals

- Shift key

- Small caps

- Text figures

- Unicase

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ «The School’s Manual of Style». Johns Hopkins, Bloomberg School of Public Health. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ Hansard, Thomas Curson (1825). Typographia, an Historical Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Art of Printing. pp. 408, 4806. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Marc Drogin (1980). Medieval Calligraphy: Its History and Technique. Courier Corporation. p. 37. ISBN 9780486261423.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis (1890). «Minusculus». An Elementary Latin Dictionary. New York, Cincinnati, and Chicago: American Book Company.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. 2000. ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

- ^ Nesbitt, Alexander (1957). The History and Technique of Lettering (1st ed.). New York City: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20427-8.

- ^ Březina, David (2012). «Challenges in multilingual type design»: 14 – via University of Reading Department of Typography and Design.

- ^ a b Dennis Oliver. «Using Capital Letters (#1)». Dave’s ESL Cafe. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Nancy Edmonds Hanson (25 August 2008). «AP Style: Courtesy and Professional Titles». Minnesota State University. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ «Capitalizing Titles of People». English Plus. 1997–2006. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ «Capitalization». The Chicago Manual of Style Online. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ «Citing Sources: Capitalization and Personal Names in Foreign Languages». Waidner-Spahr Library. Dickinson. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Cf. Güthert, Kerstin (2017), PRESSEMITTEILUNG 29.6.2017 Amtliches Regelwerk der deutschen Rechtschreibung aktualisiert (PDF), Council for German Orthography, p. 1, retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ^ «Ijsland / IJsland». Taalunie. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ «Latin Extended-B» (PDF). Unicode. U+01C4, U+01C5, U+01C6, U+01C7, U+01C8, U+01C9, U+01CA, U+01CB, U+01CC. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ «Why I Spell it Hawai’i and not Hawaii, and Why You Should, Too». Blond Voyage. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ «Hawaiian Language Online». The University of Hawai‘i. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ «Spacing Modifier Letters» (PDF). Unicode. U+02BB. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ «‘Ōlelo Hawai’i on the WWW: A.K.A., How To Give Good ‘Okina». KeolaDonaghy.com. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ RFC 1855 «Netiquette Guidelines»

- ^ «Registered features – definitions and implementations». OpenType Layout tag registry. Microsoft. Tag:’pcap’, Tag: ‘smcp’. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ «The Guardian and Observer Style Guide». TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ R. M. Ritter, ed. (2002). Oxford Manual of Style. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Currin Berdine. «What to Capitalize in a Title». AdminSecret. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (2006). «The International System of Units» (PDF). Organisation Intergouvernementale de la Convention du Mètre. pp. 121, 130–131. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ «Letterlike symbols». Charts (Beta). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ «History around Pascal Casing and Camel Casing».

- ^ «Caml programming guidelines». caml.inria.fr. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ^ «Ruby Style Guide». GitHub. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ «Character Properties, Case Mappings & Names FAQ». Unicode. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ «Unicode Technical Note #26: On the Encoding of Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, and Han». Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ David Harris (2003). The Calligrapher’s Bible. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s. ISBN 0-7641-5615-2.

- ^ Knut Kleve (1994). «The Latin Papyri in Herculaneum». Proceedings of the 20th International Congress of Papyrologists, Copenhagen, 23–29 August 1992. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- ^ «Roman Writing Systems – Medieval Manuscripts». Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ The earliest known biblical manuscript is a palimpsest of Isajah in Syriac, written in 459/460. Bruce M. Metzger & Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament (Oxford University Press: 2005), p. 92.

- ^ a b c d David Bolton (1997). «Type Cases». The Alembic Press. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

Further reading[edit]

- Hamilton, Frederick W. (1918). Capitals: A Primer of Information About Capitalization with Some Practical Typographic Hints as to the Use of Capitals – via Project Gutenberg.