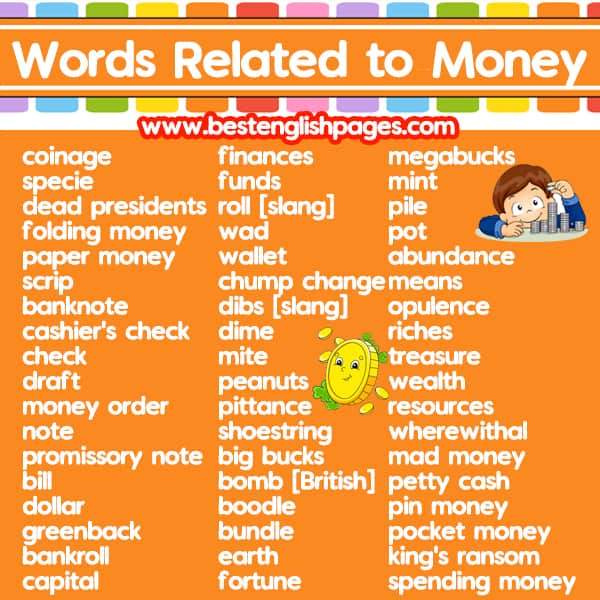

Some people often ask these questions: what are words related to money? what is another slang word for money? what do you call someone who is too careful with money? what are some positive words to describe money? In fact, this post will shed light on nouns, verbs, adjectives, and some slang words associated with money.

Money is a pretty important aspect of our lives, that is why there are plenty of different words and phrases to talk about money. For example:

- cash

- check

- fund

- pay

- property

- salary

- wage

- wealth

- banknote

- bread

- coin

- hard cash

Most people work hard to get money. We need money to buy clothes, food, etc. We can use a credit card, check or cash to buy things. Therefore, how do I talk about money in English? How can u describe money? Below is a chart that will help you boost your money vocabulary words. Also, money words example sentences will be listed to clarify the meaning of every word.

Money Words: Synonyms For Money With Example Sentences

| Synonyms For Money | Money Example Sentences |

| cash | Sabina went to the ATM to get some cash. |

| funds | Last month, our family’s funds were a little low. |

| bill | In the United States, the $5 bill has a picture of Abraham Lincoln. |

| capital | The starting capital of the new firm was around 100.000 $ |

| check | Bankers claim that new forms of check fraud raised lately. |

| salary | Pete is on a salary of $ 20.000 |

| banknote | They illegally forged banknotes. |

| currency | Carl doesn’t like coins, he prefers to carry only paper currency. |

| bread | father will buy that bike for his kids when he gets some bread. |

| silver | Anna needs $ 1 in silver for the parking meter. |

| change | I didn’t have any change for the phone. |

| property | Property prices in downtown have enormously dropped. |

| pay | Bill’s job is hard work, that is why he gets a pay raise. |

| wealth | Mr. Richardson’s wealth is estimated at around $ 250 million |

| wage | The company pays wages on Saturdays. |

| chips | He needed some chips for the parking meter. |

| payment | He prefers cash as a method of payment. |

| dough | Brother spent a lot of dough on his new tablet. |

| finances | Finance for health comes from taxpayers. |

| bankroll | The family’s bankroll right now is a total of $ 5.000 |

| bucks | The stereo costs $ 10 bucks. |

| coin | The young man moved to the big city seeking work that pays a lot of coins. |

| gravy | The ten percent profit is gravy for our business. |

| coinage | They collect gold and silver coinage. |

| gold | Gold does never buy happiness. |

| loot | Thieves have stolen a big amount of loot. |

| greenbacks | She needs 5 greenbacks to buy the notebook. |

| pesos | The poor couple had only a few pesos to buy food for the children. |

| resources | Bianca doesn’t have enough resources to buy a used car. |

| riches | Her father was pretty lucky to have a business that has brought him great riches. |

| treasure | They discovered treasures buried in the old backyard. |

| wherewithal | Antony has the wherewithal to pay cash for the new house. |

| hard cash | Do you have any hard cash? |

| wad | She gave them a thick wad of $ 20 notes. |

| legal tender | This type of coin is no longer considered legal tender. |

| long green | Where did Janet get the long green to afford a car like that? |

| exchange | That bank offers the best exchange rate. |

What Is Another Slang Word for Money? 100 Slang Words For Money

Actually, money is a major thing that most people cannot do without or live without. Money has a vast and rich bank of terms and vocabulary items. thus, What is another slang word for money? This is an interesting chart that compiles 100+ slang terms for money.

| Tender | Resources | Gold | Frogskin | Rack | Folding stuff |

| Sawbucks | Bacon | Franklins | Salad | Gouda | C note |

| Cheddar | Hamilton | Scratch | Figgas | Cheese | Pesos |

| Skrilla | Nickel | Chips | Moola | Riches | Bucks |

| Loot | Bread | Large | Bank | Five spot | Lucci |

| Ten spot | G “grand” | K | Lucre | Nuggets | Brass (UK) |

| Fins | Tamales | Cha-ching | Quid | Gelt | Jackson |

| Simoleon | Long green | Paper | Funds | Lettuce | Fiver |

| Tenners | Cabbage | Gwop | Ones | Bills | Chalupa |

| Wonga | Stash | Chump change | Dollar dollar bill y’all | Smackers | Dough |

| Boodle | Dosh | M | Clams | MM (or MN) | Stacks |

| Yard | Treasure | Bankroll | Spondulix | Greenbacks | Bones |

| Ducketts | Cream | Wampum | Cake | Wad | Dime |

| Green | Guap | Buckaroos | Yaper | Coin | Mil |

| Knots | cash money | Grand | Dubs | Doubloons | Celery |

| Hundies | Chump change | Blue cheddar | Bones | Grant | Grease |

| Bean | Dead presidents | Plunder | Capital | Bookoo bucks | Fetti |

| Mega bucks | Scrilla | Ducats | Five-spot | Benjamins | Benji |

| Green | Big ones | Payola | Dinero | Gwala | Commas |

What do you call someone who is too careful with money?

There are many words in English for someone who is very careful with money and doesn’t like to spend it. For instance, we can use such terms as a miser, cheapskate, scrooge, etc. However, all of these words are used in a derogative way, and none can be guaranteed not to offend or bother others. These are words you can use in a negative and insulting way to describe someone who doesn’t like to spend money.

- mean

- miser

- stingy

- sparing

- pinchpenny

- scrooge

- cheap

- stinting

- parsimonious

- penny-pinching

- tight

- Ungenerous

- tightfisted

- uncharitable

- ungenerous

- penny-pincher

- skinflint

- Piker

- Avaricious

- curmudgeon

- tightwad

- Penurious

- cheapskate

- chintzy

- close

- tightfisted

- Cheese-paring

- closefisted

- mingy

- miserly

- niggard

- penurious

- pinching

- spare

- niggardly

On the other hand, if we want to say nicely that someone doesn’t waste money, in this case, adjectives will work better. These are words to use to nicely describe a person who doesn’t like to spend money.

- frugal

- penny-wise

- thrifty

- economical

- economizing

- provident

- scrimping

- sparing

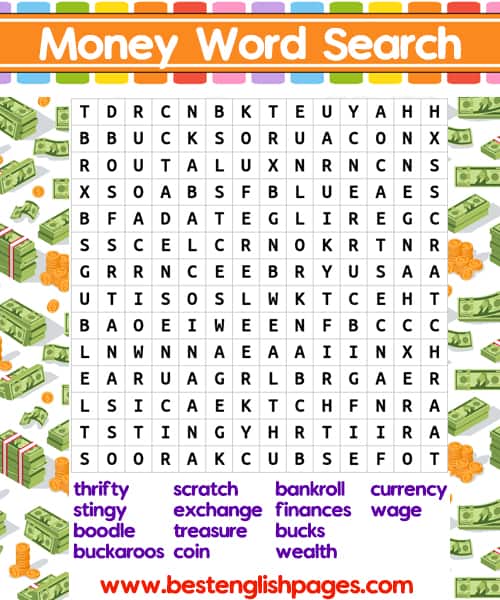

Word Search Money Vocabulary

Do you like word search games? Have fun finding Money Vocabulary with this word search. Enjoy solving it with your kids or students.

“It’s all about the Benjamins,” sang Puff Daddy. But despite what you may have mistakenly thought, the legendary American rapper wasn’t singing about a good friend named Ben. Nope. Sean John Combs, a.k.a P. Diddy, was kindly explaining a simple truth about our capitalist society: It’s all about the money.

Actually, money is so important that people came up with dozens of ways to talk about it throughout the ages. Emerging in the US, the UK or elsewhere, slang words for money became a huge part of the language we use. But how well do you know them?

Well, luckily for you, we’ve listed the most common nicknames for money to add a playful element to your conversation, your eCommerce website, your news article, the dialogues of your novels—and of course, your next rap hit. Here are 100 slang words and terms for money:

01. Bacon

Perhaps because it is so beloved, money is often referred to as this breakfast treat. Most commonly used as part of the phrase “bring[ing] home the bacon”.

02. Bank

The connection between bank and money needs no explanation. Use it to gossip about your friend’s salary increase: “Since he started working at the bank, Benjamin’s been making bank.”

03. Bankroll

Meant literally to supply money, it can also be used to refer to money itself, like: “I need some bankroll to get my bread business off the ground.”

04. Bean

An archaic term for a dollar; it’s not commonly used any more.

05. Benjamins

This one we covered above. The name references the appearance of founding father Benjamin Franklin on the one-hundred-dollar bill.

06. Benji

A nickname for our dear friend whose mug appears on the $100 bill.

07. Big ones

Like “grand” and “large”, which you’ll see below, each “big one” means $1,000. So if you’re buying a car for 10 big ones, you’re paying $10,000.

08. Bills

Another term with an obvious connection to money, this is most commonly used to refer to one-hundred-dollar bills.

09. Bones

Can be used in exchange for “dollars”, as in: “These grills cost 100 bones.”

10. Boodle

A term for shady cash, like counterfeit, stolen or bribe money.

11. Brass (UK)

This is a Northern British slang term for money, believed to have originated from the region’s scrap dealers scrounging for materials that were valuable, like brass. It’s related to the phrase “Where there’s muck, there’s brass.”

12. Bread

A synonym for food in general, this has meant money since at least the 19th century. Like bacon, it’s something you “bring in”: “She’s selling bread online in order to bring in the bread.”

13. Bucks

Perhaps the most commonly used slang term for dollars, it is believed to originate from early American colonists who would often trade deerskins, or buckskins.

14. C note

C equals 100 in the Roman numeral system and stands for the latin word centum, which means “a hundred” (and which also originated the word cent). Thus, a C note is a $100 bill.

15. Cabbage

When all those green bills are packed together, don’t they resemble cabbage? Ludacris thinks so: “Hustle real hard, gotta stack that cabbage / I’m addicted to money.”

16. Cake

Even better than bread or dough is a food that has icing and is served at parties.

17. Cash (or cash money)

Perhaps an obvious one, but still useful.

18. Capital

Not necessarily a slang term when employed in a business context, but can also be used as slang to refer to any kind of money, not just capital. Does that make cents? (See what I did there?)

19. Celery

Like cabbage and lettuce, this green veggie also means money. If you don’t believe me, take it from Jeezy, who boasts about a “pocket full of celery” in his 2009 hit “Put On” featuring Kanye West.

20. Cha-ching

It’s the best sound in the world to some—the cash register completing a sale. It’s also been used as a replacement term for money.

21. Chalupa

This mostly means a deliciously spicy Mexican taco, but is also slang for money.

22. Cheddar

If someone has the cheddar, it means they must be making bank.

23. Cheese

A nickname for money because Americans used to receive cheese as a welfare benefit.

24. Chips

A reference to poker chips, it now just means money.

25. Chump change

This refers to a small amount of money, like the amount of cash a chump would have.

26. Clams

Means “dollars”, as in: “Karen raised my rent by 100 clams.”

27. Cream

This is an acronym of “Cash Rules Everything Around Me” and was popularized by the Wu-Tang Clan in the 90s: “Cash rules everything around me / C.R.E.A.M. / Get the money / Dollar, dollar bill y’all.” The song encouraged listeners to not make the mistake of chasing money by selling drugs.

28. Coin

Looking to borrow money from a friend? Ask her: “Can I borrow some coin?”

29. Dead presidents

American currency acts as a who’s who of dead presidents. (Plus Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin, who were never presidents but appear on the $10 and $100 bills, respectively.) Use this term to let people know you’re no sell out, like Eminem.

30. Dime

In the US, a dime is the coin worth ten cents, but the term can be used to mean money or an expense in general. For example, if your employee is sitting on social media instead of working, you can dramatically exclaim: “Not on my dime!”

31. Dinero

Because who doesn’t love the sound of Spanish? Dinero is the Spanish word for “money” and was first popularized in the Old West as early as the mid-19th century.

32. Dollar dollar bill y’all

Okay, this one is mostly an excuse to link to this rap classic from 2009. You’re welcome.

33. Dosh (UK)

A British slang term for money.

34. Dough

Another very commonly used term for money, it’s been around for a while. It likely became common as a branch off from “bread”, but the Oxford Dictionary found the term used as early as 1851, in a Yale publication: “He thinks he will pick his way out of the Society’s embarrassments, provided he can get sufficient dough.”

35. Dubs (or doubles or double sawbuck)

This term means a twenty-dollar bill, so two dubs refers to 40 bucks.

36. Ducats

A gold or silver coin that was used in Europe, mostly in Venice, starting from the Middle Ages.

37. Ducketts

The very American pronunciation of the previous word is used to refer to poker chips—but also money.

38. Fetti

A gross mispronunciation of the Spanish word feria, which in Mexico is used to mean coins. But maybe the term is also the result of the confetti-like image of money pouring from the sky when someone “makes it rain”.

39. Figgas

A hip-hop term to describe the number of figures in an amount of money.

40. Fins

A slang term for five-dollar bills. The source is likely from the German/Yiddish word for five: German—Funf, Yiddish—Finnif.

41. Five spot

A five-dollar bill.

42. Fiver

Another term for the five-dollar bill, as in: “I make about a fiver on each t-shirt I sell.”

43. Folding stuff

This refers to the stuff that folds, i.e. paper money. “I can’t believe you spent so much folding stuff on that lemon of a car.”

44. Franklins

And once again, we are back to our friend Benjamin, who appears on that much-beloved one-hundred-dollar bill.

45. Frogskin

An archaic term for dollar bills, perhaps related to the term “greenback”.

46. Funds

“I’d plan a trip to Hawaii, but I got no funds.”

47. G

Short for “grand”, this refers to $1,000 dollars. Having five G in the bank shouldn’t cause you to worry about cellphone towers, but should result in a celebration for having “dollar dollar bill y’all”. (Not to confuse with G, which is also short for “gangster”, as in “Benjamin Franklin was a real G”.)

48. Gelt

A Yiddish term meaning “gold” and is most commonly used to refer to the money (chocolate or real) given by parents on the Jewish festival of Hanukkah.

49. Gold

Does this need any explanation?

50. Gouda

Rapper E-40 coined this term for money in his hit “Gouda”. The slang king then goes on to explain the meaning by using many of the other terms listed here: “The definition of Gouda, what’s the definition? / Chalupa, scrilla, scratch, paper, yaper, capital…”

51. Grand

Refers to $1,000 since the mob coined the term (no pun intended) in the early 1900s. Back then $1,000 was a “grand” amount of money, and they wanted to be discreet.

52. Grant

A $50 bill, in reference to President Ulysses S. Grant, whose face is featured. (Speaking of Uly, did you know that the S doesn’t stand for anything?)

53. Grease

If you grease someone’s palm or someone’s pockets, it means you gave them some money, usually as a bribe.

54. Green

A reference to the color of American money. Can be used like in: “I’m all out of green, so I’ll pay you back next week.”

55. Greenbacks

A form of American currency printed in the Civil War. The front of the bill was printed in black while the back was printed in green.

56. Guap

Same pronunciation as gwop, this refers to a large amount of money.

57. Gwala

Another related term to guap and gwop that means a stack of cash, as in: “Grease his pockets with a little gwala.”

58. Gwop

This slang term for money is actually an acronym of “George Washington On Paper”—referring to the first US president, who appears on the one-dollar bill.

59. Hamilton

Even though he wasn’t a president, the Founding Father without a father got a lot farther by being on the ten-dollar bill.

60. Jackson

Not as expensive as a Franklin or a Benjamin, this refers to President Andrew Jackson who appears on the twenty-dollar bill.

61. K

Refers to the prefix kilo, i.e. one thousand. So 500K means $500,000.

62. Large

Similar to grand, this term also refers to $1,000.

63. Lettuce

Like cabbage and celery, this is an old slang term that means “money” or “currency”.

64. Long green

Another slang term for “cash” that references the color and shape of that dollar dollar bill y’all.

65. Loot

Referring to money, you can tell your customer to “Hand over the loot”—but you probably shouldn’t.

66. Lucci

An Italian sounding word that rappers like to use to talk about money, but it’s not Italian for anything so it’s unclear why. (Some people believe it’s slang for lucre.)

67. Lucre

Often used in the phrase filthy lucre to refer to a “shameful gain”, according to Merriam-Webster. While the term has taken on a slang-like connotation, it’s a legit word and is related to lucrative.

68. M

This one can actually be confusing. While M is the Roman numeral for a thousand, when used with money, it usually means a million. So $3M equals $3,000,000.

69. MM (or MN)

Many banks will use this to refer to millions of dollars.

70. Mil

This is another popular abbreviation of million, when talking dollars.

71. Moola (or moolah)

This is another age-old slang term for money, but nobody seems to really know where it originated. Merriam-Webster says the word was first used to mean money in 1936.

72. Nickel

The metal that makes up a crucial element of the Earth’s core is also used to make five-cent coins. Used as slang, this term can mean $5 or $500 worth of something—particularly when talking about gambling or drugs.

73. Nuggets

A term for money that probably refers to gold nuggets, but may as well refer to the many other valuable things that come in the form of nuggets: chicken, wisdom, truth, Denver’s basketball team, etc.

74. Ones

Means one-dollar bills. If you’re all out of ones, you’ll need to ask for change to buy a can of coke from the machine.

75. Paper

The material used to print that dollar dollar bill y’all. Chasin’ that paper is just a part of “living your life”, according to this 2008 classic by Rihanna and T.I.

76. Pesos

The official currency of Mexico can be used in American slang to refer to dollars as well.

78. Quid (UK)

The origin of this slang term for the British pound (or sterling) is uncertain, but it’s been around since the late 1600s, according to Merriam-Webster.

79. Rack

$1,000 or more in cash.

80. Resources

Use it to sound fancy but also street: “Ain’t got the resources to pay for that activity at the moment.”

81. Riches

An especially useful word to refer to money when you’re trying to sound like you have lots of it. Technically speaking, a gorgeous example of a synecdoche.

82. Salad

If lettuce, cabbage, celery and beans all mean money, you might as well put it all together and dress it.

83. Sawbucks

A ten-dollar bill. The source of this term comes from the sawhorse that resembles the Roman numeral X (for “10”) that was found on the back of the 10-dollar bill. The word then evolved to sawbuck because “buck” means “dollar”.

84. Scratch

This word has been used to mean money since the beginning of the 20th century, but we don’t seem to know why. Some believe it’s a reference to the phrase “starting from scratch” to imply that everything starts with money.

84. Shekels

A biblical currency that is also used presently in Israel. The word shekel is rooted in the Hebrew term for “weight”.

85. Simoleon

Slang for “dollar” associated with old-timey American gangsters.

86. Skrilla (or scrilla or scrill)

The origin of this term to mean money or cash is also unknown, but it was used in rap music starting in the 1990s.

87. Smackers

An East Coast way of saying dollars, especially if you’re a 60+ year-old man betting on a football game: “I’ll bet ya 100 smackers that the Jets find a way to lose this one.” It usually refers to enough cash to smack someone in the face with.

88. Spondulix

A 19th-century term for money, you can also spell it spondulicks, spondoolicks, spondulacks, spondulics, and spondoolics. Be really hip and refer to it as spondoolies.

89. Stacks

Similar to racks, this term also means $1,000. “I had to get my car fixed and it cost me 3 stacks.”

90. Stash

Refers mostly to money you have hidden away.

91. Tamales

Nobody really uses this term anymore, but it was a common term to mean dollars.

92. Ten spot

A ten-dollar bill.

93. Tender

From the longer (and more boring sounding) term legal tender.

94. Tenners

Ten-dollar bills, as in: “Can I get two tenners for one of these dubs?”

95. Treasure

This is an especially useful term for money if you’re a pirate.

96. Wad

A bunch of cash, enough that you can roll it up into a wad.

97. Wampum

Polished shells worn by Native Americans and sometimes used as a form of currency. The term was popular as slang for money for a while, but now is mostly used to refer to marijuana.

98. Wonga (UK)

A Romani word that means “coal”, which was another term used by Brits to refer to money.

99. Yaper

Usually refers to drug money.

100. Yard

Usually refers to $100, but apparently can also be used to mean $1 billion—just in case that’s an amount of money you and your friends chat about.

Looking to create a blog? Wix has got your covered with thousands of design features, built-in SEO and marketing tools, that will allow you to scale your content, your brand and your business.

Mendy Shlomo, eCommerce Blogger at Wix

Mendy is the manager of Wix’s eCommerce Blog. A journalism survivor, he’s transitioned into the rich world of online selling, content marketing and SEO. His parents are thrilled.

Today, you’re going to increase your money vocabulary with 42 words and phrases about money. Also check out Maths Vocabulary in English: Do You Know the Basics?

Like it or not, money is a big part of most of our lives.

So it’s important to be able to talk about it, right?

Here are 42 usfeul words and phrases to help you talk about money in English.

Words to describe physical money

Note

This is British English, and it basically means “a piece of paper money.” It’s short for “bank note.”

“I found a ten-pound note in the street the other day.”

“I tried to buy a sandwich with a fifty-pound note, but the shopkeeper wouldn’t accept it.”

Bill

“Bill” is the American word for “note.”

So we can talk about ten-pound notes, but we usually say ten-dollar bill.

My main question is “Who’s Bill?”

Coins

The money that isn’t notes — those shiny metal things? Those are coins.

Here’s something I’ve noticed about travelling:

In some countries, you end up with loads and loads of coins in your pocket. They just have so many of them.

The UK is one of those countries.

Shrapnel

This word actually means the small pieces of metal that explode out of a bomb or a grenade.

But when we’re talking about money, it’s a very informal way to describe coins.

But there’s a difference in how we use “shrapnel.”

The word “coin” is countable:

“How many coins have you got in your pocket?”

But the word “shrapnel” is uncountable:

“How much shrapnel have you got on you? I need to get a ticket, and the machine doesn’t accept notes.”

Change

When we pay for something, we do it one of two ways.

We can give the exact change: if the toothbrush you’re buying costs £1, and you give the shopkeeper £1, you’ve given the exact change.

But if you don’t have any shrapnel on you, you might want to pay with a five-pound note.

Then the shopkeeper gives you £4 in change.

Or perhaps you only have a fifty-pound note. So you try to pay for the toothbrush with that.

The shopkeeper just shakes his head and says, “Sorry, mate. I can’t break a fifty.”

What does it mean?

If the shopkeeper can’t give you the correct change for the fifty pounds because he doesn’t have it, then he can’t break the fifty-pound note.

And you don’t get a toothbrush.

Coppers

Most countries have very, very low-value coins.

What colour are they in your country?

Probably, they’re this dark orange colour — or copper colour.

That’s why we call them coppers.

Words to describe amounts of money

Fiver

This is British English, and it means “five-pound note.”

Easy, right?

Tenner

OK, you’ve guessed this one, haven’t you?

Yep — it means “ten-pound note.”

This only works for five pounds and ten pounds. We can’t say, for example, a twentier. It just sounds weird.

A lot of people I know (including myself) use these words when we’re outside the UK to talk about ten lira or ten lev or ten euros or whatever the currency is where we are.

K

I wrote about this in my big post on how to say numbers in English.

If you add “K” to a number in English, it means “thousand.”

Here’s an example for you to see how it works (and also to see how ridiculously overpriced things are in the UK).

These are beach huts:

They’re cute things that you’ll often find on the beach in the UK.

The idea is that you buy one and then you have a little room to change your clothes in, drink tea in and even have a nap in when you’re at the beach.

This one in the photo is in Brighton, my hometown.

Want to buy one? Well — they’re pretty expensive.

These guys cost over 20K.

Ridiculous, isn’t it?

Grand

“Grand” is exactly the same as “K.”

It means “thousand.”

“I still can’t believe those beach huts are going for over 20 grand each.”

Cash

Cash is real money — not virtual money.

If you’ve got bank notes or coins, then you’ve got cash.

If you’re using your card (or cheques, like it’s the ‘80s), then you’re not using cash.

Also — Johnny Cash. Because there’s never a bad time for Johnny Cash.

Words to describe currencies and denominations

Pound

I’m sure you know this one. It’s the currency used in the UK.

But just one thing: you don’t need to say “sterling.” No one uses it!

In fact, I had no idea what it meant until I was an adult.

Quid

You’ll hear this one a lot in the UK.

This is British English, and it means “pound.”

But be careful!

The plural of “quid” is “quid” (not “quids”).

So your kettle might cost one quid or fifty quid.

Which is really expensive for a kettle. Even a nice electric one with flashy green lights and everything.

Don’t buy it!

Bucks

This is originally American English, and it means “dollars.”

When I visited Australia back in February, I was pleased to hear that they use “bucks” there, too. A lot.

It feels good to say, right?

“That’ll be seven bucks, please.”

p

This is short for “pence.”

There are 100 pence in a pound.

It’s also the same in the singular and plural — so something could be 1p or 50p.

But prices can get a little tricky to say when they get more complicated. Click here for more on how to say prices correctly — it’s harder than you think!

Ways to talk about using the ATM

ATM

OK. What’s this?

Yep — it’s an ATM.

Cash machine

OK. What about this?

Yep — it’s an ATM.

But we can also call it a cash machine.

Hole-in-the-wall

And this? What’s this?

Yep — it’s an ATM or a cash machine or, if you’re talking to someone from the UK, a hole-in-the-wall.

But what can you do with it?

Withdraw

OK. You’ve got no cash on you, and you need to buy that amazing teapot — and you need to buy it NOW!

So you go to the cash machine and withdraw the cash you need.

Take out

“Withdraw” is quite a formal word.

In most situations it’s nice to use this phrasal verb instead:

“Give me five minutes — I’ve just got to go to the ATM and take out a bit of cash.”

Deposit

So we can use the ATM to withdraw money, but we can also use it to do the opposite.

When you deposit money, you take the real money you have in your hand, let the machine eat it up and watch the money get added to your bank account.

Put into

So “withdraw” is quite formal and “take out” is quite informal.

Also “deposit” is quite formal and “put into” is quite informal.

“Someone’s put about four grand into my account! Where did it come from?”

Ways to describe the money you get

Payday

This is, surprisingly, the day you get paid.

Maybe it’s every Monday.

Or maybe it’s on the first of the month.

Or maybe it’s NEVER! (That job was awful.)

Salary

Usually when people talk about their salary, they’re describing how much they get paid every year or every month or, sometimes, every hour — but only two of these are technically correct.

A salary is how much you get paid every year.

However, you’ll often hear people talk about a “monthly salary.”

And that’s fine, as the monthly salary is calculated based on how much you make in a year.

Wage

So how do we describe the amount of money you get per hour?

That’s when “wage” comes in.

A wage is usually used to describe the money you get for one hour’s work.

Most countries have a minimum wage, which is the smallest amount of money a company can legally pay their workers.

Income

This is the money you get over a period of time.

So we can talk about a weekly income, a monthly income or a yearly income.

But we actually use this word in lots of others ways.

For example, a way to describe poor families or rich families is by using the term “low-income household” or “high-income household.”

This is often used by people who work in sales. Probably because when you’re trying to sell stuff to people, it’s good to avoid the words “rich” and “poor.”

We can also use the phrase “on a six-figure income” (an income with six numbers, e.g., $500,000).

It’s basically a way to say you’re rich:

“50 quid for a kettle? No problem — I’m on a six-figure income.”

Words to describe paying less

Discount

Here’s it is — your dream toaster:

It not only makes toast, but can filter coffee, travel through time and also make your enemies do embarrassing things in public.

But there’s a problem. A predictable one.

It’s really expensive — completely out of your price range.

Then, one day, the shop decides to sell it at a much cheaper price.

In fact, they cut the price by 80%.

That’s an 80% discount.

Now you can afford it!

Go get that toaster!

Sales

There are some times of the year when the shops go crazy with discounts.

In the USA, there’s an event called Black Friday. And it’s absolutely mental and ridiculous.

Just for one day, the shops discount everything — a lot.

As a result, people start queuing outside stores one, two, even three days before the special day.

When the doors open, everyone tries to kill each other (almost) to get to the cheap, heavily discounted, stuff:

via GIPHY

(Really — is stuff that important?)

Anyway, Black Friday is a massive sale — a period of time when a shop, or lots of shops, have big discounts.

You also have closing-down sales, when shops are about to close down, and they want to sell everything they have left.

When you buy something at a discount because it was part of a sale, you can say it was “on sale.”

“Do you really want to buy that?”

“Yeah — I think so. Anyway, it’s on sale.”

Mates’ rates

Sometimes shops give discounts.

But so do friends.

Let’s say you’ve got a good friend who does awesome tattoos.

Everyone wants her to do their tattoos.

In fact, she’s the most popular tattoo artist in town and, as a result, she charges a lot of money for them.

But not to you — you’re one of her best friends.

You can get a tattoo from her at a much cheaper price.

She’s your friend, so she charges you less.

She does that tattoo at mates’ rates — a discount for friends.

Ways of describing having no money

We’ve all been there, right?

That time when you just have no money to spend.

There are a few ways of describing this.

Skint

This is British English and basically means “without money — at least for now.”

It’s an adjective:

“Coming to the pub?”

“Not tonight, mate. I’m skint at the moment.”

Remember — it’s usually a temporary situation (like the day before payday). It’s different from being poor, which is something more permanent.

Broke

This is basically the same as “skint” but, it’s used outside the UK.

Flat broke

This means “very broke — really — I have literally NO money!”

Ways of describing how much stuff costs

Pricey

You know that feeling, right?

You’re in a new city, and you’re hungry.

You see a restaurant that looks quite good — not too posh, so probably not expensive.

You sit down and look at the menu … and the prices.

Now — if the menu was really expensive you’d just leave, right?

But what if it’s only a bit expensive?

Just a little bit more than it should cost?

Well — you’d probably stay, wouldn’t you?

Even though the menu’s a bit pricey — a little bit more expensive than it should be. But only a little bit.

A waste of money

OK. All of a sudden, you’ve got a grand.

Quick! What do you spend it on?

You could spend it on a trip around the world.

Or you could put it in the bank and save it.

Or you could renovate your kitchen — it really needs it.

All good ideas, right?

Or you could buy that giant dog statue you saw yesterday.

Not such a good idea, right?

What? You went for the dog statue? Seriously?

You’ve spent the money on something stupid! It’s a complete waste of money!

A bargain

When you buy something, and you get a great deal. It’s much cheaper than expected.

Perhaps it’s a skiing holiday in France for less than 100 bucks.

Or a beautiful teapot for just a quid.

Whatever it is, enjoy it — it’s a bargain!

Ways of describing spending money

Splash out

Awesome! You’ve received a bonus 200 quid in your salary this month.

What are you going to do with the extra cash?

Well — you could save it.

Or you could splash out on that dream toaster you’ve always wanted.

“Splash out” basically means “spend freely.”

It’s usually for a special treat — something you wouldn’t usually buy because it’s a little pricey. But just this once. This is a special occasion! Why not?

Blow it all

You decide to sell your car because you realise that bikes are way better. (They are!)

So you sell it, and you get a good deal for it.

One day you have loads of money in your pocket.

So you take all your friends out for a big meal.

The next day you wake up and check how much is left.

Nothing! Not a penny!

You’ve blown it all!

When you blow your money on something, it means you spend a lot of money on something useless.

“When he was fired, the company gave him 20 grand. Guess what? He blew it all on a golden toaster. Unbelievable!”

Break the bank

This means “spend more than you should” or “spend more than you can afford.”

However, it’s often used in the negative to give a good reason for buying something:

“Well — it looks fun … and the tickets are only five quid.”

“Yeah! Let’s do it! It’s not exactly going to break the bank!”

Ways of describing not spending money

Stingy

Here’s Tony. You may remember him from my post on negative personality adjectives:

He hates sharing his stuff.

And he most certainly will NOT be buying you a drink anytime soon.

He’s stingy!

It’s basically the opposite of “generous.”

Tight-fisted

This is basically the same as “stingy.”

We can also shorten it and just say “tight.”

“Hey, Tony! Can you lend me a couple of quid? I haven’t got enough on me for the ticket.”

“No. Buy your own ticket!”

“Come on! Don’t be so tight!”

On a tight budget

Money’s a funny thing, isn’t it?

Sometimes there are good times, and we feel like we can afford pretty much anything.

And sometimes there are … not-so-good times.

Times when we need to be careful about what we spend.

Times when even spending a quid or two on a cup of tea can break the bank.

That’s when we’re on a tight budget.

On a shoestring budget

This is similar to “on a tight budget,” but we use it when we’re describing how much money there is for a specific thing.

I have a friend who decided to cycle from Istanbul to Manchester on a shoestring budget.

Some of the best films were made on a shoestring budget.

Get the idea?

OK, so that was a lot of money vocabulary — 42 words and phrases to talk about money in English.

But what did I miss?

What other words and phrases about money can you think of?

Let me know in the comments!

Did you like this post? Then be awesome and share by clicking the blue button below.

Few things get more attention it seems than money. People use it every day—sometimes multiple times a day.

People plan where they live around money, where they travel around money, where they work around money, and where they retire around money.

Since money is an essential tool that most people cannot live without, it has developed a rich and colorful bank of slang terms in which to be described.

Who says writing about money has to be boring? Finance, currency, legal tender? Incorporate some change into your financial writing.

What is slang for money? Here is a list of 80+ slang terms for money. Some of the terms are similar to each other; some are even derivatives of each other, but they all relate back to money.

This is not an exhaustive list. I’m sure there are some terms I missed, and I’m sure more terms will be coined in the years to come. In any event, this is a fun list to get your brains rolling.

Slang for Money List:

- Bacon: Money in general; bring home the bacon.

- Bands: Paper money held together by a rubber band. Usually $10,000 or more.

- Bank: Money; Obviously related to banks that hold money.

- Bankrolls: Roll of paper money.

Benjamins: Reference to Benjamin Franklin, whose portrait is on the one hundred dollar bill.

- Big bucks: Large amounts of money; generally used in reference to payment or employment compensation.

- Bills: A banknote; piece of paper money.

- Biscuits: Money in general; origin unknown.

- Bisquick: Money in general; origin unknown.

- Blue cheese: Reference to the new U.S. 100-dollar bill introduced in 2009, which has a blue hue to it.

- Blue cheddar: See blue cheese.

- Bookoo bucks: See big bucks.

- Bones: Dollars (origin unknown).

- Bread: Money in general. The analogy being that bread is a staple of life. Food is a common theme for slang money terms.

- Brick: A bundled or shrink-wrapped amount of money, usually in amounts of $1,000 or $10,000. A reference to the rectangular shape that looks like a brick.

- Broccoli: Paper money, reference to its color.

- Buckaroos: Money in general.

- Bucks: Dollars; Thought to be a reference to deer skins used for trading.

- C-note: One hundred dollars; a reference to the Roman Numeral for 100.

- Cabbage: Paper money. In reference to the color of U.S. currency.

- Cake: Money in general; similar to bread and dough.

- Cash: Money in general.

- Cash money: see cash.

- Cheese: Money in general (origin unknown).

- Cheddar: Money in general (origin unknown).

- Chits: Money in general; originally a signed note for money owed for food, drink, etc.

- Chips: Money in general; reference to poker chips.

- Chump change: A small amount of money.

- Clams: Money in general; Possible origin is thought to be clamshells that were once used as a form of currency by Native American Indians in California.

- Coin: Money in general, paper or coin.

- Commas: Money in general, reference to increasing amounts of money; moving from one comma to two commas as in from 10,000 to 1,000,000.

- CREAM: Acronym meaning “cash rules everything around me.”

- Dead presidents: Paper money; a reference to the presidential portraits that most U.S. currency adorns.

- Dinero: Money in general; originally the currency of the Christian states of Spain.

- Dime: Another reference to coin, specifically the dime.

- Doubloons: Money in general; reference to gold doubloons.

- Dough: Money in general (origin unknown).

- Fetti: Money in general; originates from feria, the Spanish term for money.

- Five-spot: Five-dollar bill.

- Fivers: Five dollar bills.

Franklins: Hundred dollar bills. Benjamin Franklin is one the U.S. hundred dollar bill.

- Frog: $50 bill in horse racing.

- Frog skins: Money in general.

- Gold: Money in general; reference to gold as being a tangible product for thousands of years.

- Green: Paper money, referencing its color.

- Greenbacks: Paper money; Greenbacks were U.S. current in the Civil War.

- Gs: Shorthand term for “grand,” which is a thousand dollars.

- Grand: One thousand dollars. In the early 1900s, one thousand dollars was thought to be a “grand” sum of money, hence grand.

- Guac: Money in general; reference to guacamole’s green appearance.

- Guineas: A coin minted in England from 1663-1813.

- Gwop: Money in general.

- Half-yard: Fifty dollars.

- Hundies: Hundred dollar bills.

- Jacksons: Twenty dollar bills. Andrew Jackson is one the U.S. twenty dollar bill.

- Knots: A wad of paper money.

- Large: Similar use as “grand.” Twenty large would be the same as saying twenty grand.

- Lincolns: Five dollar bills. Abraham Lincoln is one the U.S. five dollar bill.

- Long green: Paper money, from its shape and color.

- Lolly: Money in general; origin unknown.

- Loot: Large sum of money; originally money received from stolen plunder or other illicit means.

- Lucci: Money in general; loot; possibly stemming from term lucre.

- Lucre: Money that has been acquired through ill-gotten means.

- Mega bucks: See big bucks.

- Monkey: British slang for 500 pounds sterling; originates from soldiers returning from India, where the 500 rupee note had a picture of a monkey on it.

- Moola: Money in general (origin unknown) Also spelled moolah.

- Notes: Money in general; reference to banknotes from a bank.

- Nugget: Referencing gold, but a general term for money of any kind.

- OPM: Other people’s money; accounting term.

Paper: Paper bills of any kind.

- Payola: Money in general, specifically money earned as compensation for labor; a paycheck.

- Pesos: Money in general; Pesos are the official currency of Mexico.

- Plunder: Stolen money.

- Quid: One pound (100 pence) in British currency.

- Rack: Synonym for dollars when talking about thousands. Five thousand racks. Ten racks.

- Rock: Million dollars

- Roll: Shortened term for bankroll.

- Sawbuck: Ten-dollar bill. Originated from a sawbuck device, which is a device for holding wood to be cut into pieces. Its shape is that of an “X” form at each end, which are joined by cross bars below the intersections of the X’s. The “X” shape resembles the Roman Numeral for ten, hence sawbuck.

- Scratch: Money in general (origin unknown).

- Scrilla: Money in general (Possibly formed from analogy to another slang money term: paper. Paper once came in the form of a scroll. Scroll became scrilla.).

- Shekels: Money in general (biblical currency; also modern day currency of Israel).

Singles: Single one-dollar bills.

- Smackers: Dollars (origin unknown).

- Stacks: Multiples of one thousand dollars.

- Ten-spot: Ten-dollar bill.

- Tenners: Ten-dollar bills.

- Turkey: Money in general; sometimes referred to in the phrase let’s talk turkey.

- Wad: Large sum of money; usually a bundled sum carried in your pockets.

- Wonga: English Romany word for money.

- Yard: One hundred dollars.

Summary: Slang for Cash

Until then, I will be here documenting them as they appear on the literary scene.

If you see any easy terms that I missed in my list, tweet me at @Writing_Class, and I will add them to the list.

People really love money since it is needed to buy just about everything. Perhaps the fact that money is so important may help to explain why there are so many different ways to say it. These 95 slang words for money and their meanings are really worth taking a look at. This list not only contains the countless ways to speak, write or say the word money, but also what are the meanings behind each phrase or term.

Money is by far one of those words that has more slangs or terms for it than any others. This proves that cash or money, does not have be boring when speaking about it. Just keep in mind that these slang synonyms are in plural form. They are also words mostly used for US currency. Lastly, remember to never use any of these slangs for money if you are doing formal writing.

Interested in money? Then check out Great Money Management and Saving Tips for Students

The Slang Words For Money List

- Benjamins – This reference to money comes from the face of Benjamin Franklin which is found on the 100 dollar bill.

- Bacon – No this is not about food. Bringing ‘home the bacon’ means just that, you are bringing home the money.

- Bank – Using this term when speaking about money is never about the banking institution

- Bands – Since most people with large rolls of cash need rubber bands to hold them together, this where the word comes from.

- Big Ones – In reference to having multiple thousands.

- Bankrolls – Oh, the joy of having rolls of paper money.

- Bills – If you have a lot of one hundred dollar bills, then this is the term to use.

- Big Bucks – When referring to receiving employment compensation or payments, this is where the term applies.

- Biscuits – No, we are not referring to cookies here. This is what you call money in slang. Unknow origin.

- Bisquick – Same as above, only getting money at a faster clip.

- Bones – Skeletons need not apply to this term, only dollars. Unknown origin.

- Bread – Since cash is the staple of life, the term bread is applied well here.

- Bookoo Bucks – Same as big bucks.

- Broccoli – Since the vegetable is green, just like cash, the slang fits.

- Buckaroos – All cash money in general.

- Cabbage – Cash money is green, so is cabbage.

- Cheddar – Cheese is often distributed by the government to welfare recipients. The origin of this is unknown, but most seem to agree that this is where the term came from.

- Chedda – Another way of saying cheddar.

- Cake – Since cake is the same as bread or dough, then it means money.

- Cash – Nuff said.

- Cash Money – See above.

- Chits – This originated from signed notes for money owed on drinks, food or anything else.

- Chips – Since having a large sum of poker chips means you have money.

- CREAM – This word is an acronym which means “Cash Rules Everything Around Me.”

- Clams – If you got clams, then you got money.

- Coin – Whether paper or coin, if you got it, then you got cash.

- Chump Change – This refers to money, but only small sums of it.

- Cs or C-notes – The Roman symbol for one hundred is C so this goes back to that.

- Dead Presidents – This is reference to all the presidents which appear on the US currency.

- Dime – When you have multiple sums of ten dollar bills, you got a lot of dimes.

- Dinero – Meaning money is Latin, this originated from the currency of Christian states in Spain.

- Doubloons – Gold doubloons equals money.

- Dough – If you got the dough, then you definitely have some cash.

- Doubles – In reference to 20 dollar bills.

- Dubs – Same as above

- Ducats – In reference to the Italian coin.

- Fins – Not the fish, but the five dollar bills.

- Five Spots – $5.00 dollar bills.

- Fivers – Same as above.

- Fetti – This term originated from the Spanish term ‘Feria’ which means money, of course.

- Franklins – Benjamin Franklin is very popular in the slang world. This is in reference to him and the $100.00 bill.

- Frog – Unclear of origin, meaning a $50 bet on a horse.

- Frog Skins – Cash money in general.

- Folding Stuff – Reference to paper money being able to be folded.

- Greenbacks – Term from the color of the ink on the money.

- Grand – This term dates back to the early 1900’s when having a thousand dollars was considered to be very grand or a grand sum of money.

- G’s – If you got G’s, then you got a lot of cash – Reference to thousands.

- Gold – In any language, gold equals money since it is a tangible product for countless of years.

- Green – This is in reference to the color of money being green in paper money.

If you like to write and make some cash then check out Make Money Writing by Using These Websites

- Guineas – Term used due to the coin which was minted in England during the years 1663 to 1813.

- Guac – Guacamoles are green in color so this is where the short version comes from.

- Gwop – Currency in general.

- Half-yard – In terms of the fifty dollar bill.

- Hundies – All about the hundred dollar bills.

- Jacksons – The president Andrew Jackson is on the $20 bill. If you got ‘Jacksons,’ then you got cash!

- Knots – Wads of money are usually in knots.

- Large – Term used for the thousand dollar bill.

- Lettuce – Another green vegetable with a green color which means paper money.

- Long Green – This comes from the paper money’s color and shape.

- Lucre – Derives from the biblical term ‘Filthy lucre’ which means ‘money gained illicitly’.

- Loot – This term originally came from reference of spoils of war or other money earned unlawfully.

- Lolly – The origin is unknown but it is in reference to money in general.

- Lucci – This can be another version of lucre – although real origin unknown.

- Mega Bucks – Same as big bucks

- Monkey – This originated from the British slang for 500 pounds of sterling. When soldiers returned from India, they had a 500 rupee note which had an image of a monkey.

- Moola – Also spelled moolah, the origin of this word is unknown. It is about money in general terms.

- Notes – Just like C-notes, this refers to bank notes from a financial institution.

- Nuggets – The reference is from gold being a term of money.

- Nickel – Based on the five dollar bill. This refers to multiplying the value of the five-cent coin.

- Ones – Dollar bills, same as fives, tens and so on.

- OPM – Acronym for Other People’s Money.

- Paper – Money in paper bills of any kind.

- Pesos – Latin for money or dollars. The peso is the currency in Mexico and sevaral other latin countries.

- Payola – This is reference to money earned via a paycheck or for labor done.

- Plunder – Just like the real word and its meaning, stolen money.

- Quid – Reference to British currency which means one pound or 100 pence.

- Quarter – Referring to twenty five dollars. This goes back to multiplying the value of the coin for 25 cents.

- Rack – This refers to money when talking about thousands. Each rack is synonymous for dollars.

- Rock – If you got the rock, you got a million dollars.

- Roll – Short term which refers to bankroll one may have.

- Scratch – Refers to money in general. The origin is unknown though.

- Scrilla (Also spelled Skrilla) – Slang possibly formed from other terms such as scrolls (meaning paper) and paper meaning money.

- Sawbucks – This terms is in reference to the Roman symbol for ten – X – or a sawhorse.

- Shekels – Derives from the biblical terms, meaning dollars.

- Smackers – Reference to dollars. Origin unknown.

- Singles – Dollar bills equals money in singles.

- Simoleons – Used from the slang from British sixpence, napoleon from French currency and the American dollar combination.

- Spondulix – Derives from the Greek word ‘Spondylus’ which was a shell used a form of currency once.

- Stacks – Referring to having multiple stacks of thousand dollars.

- Ten-spot – Meaning ten dollar bills.

- Tenners – Same as above.

- Two-bits – A reference to the divisible sections of a Mexican ‘real’ or dollar. Also twenty five cents.

- Wad – Have a bundle of paper money.

- Wonga – This derives from the English Romany word for money.

- Yard – Meaning one hundred dollars.

With dictionary look up. Double click on any word for its definition.

This section is in advanced English and is only intended to be a guide, not to

be taken too seriously!

Slang money words, meanings and origins

While the origins of these slang terms are many and various, certainly a lot of English money slang is rooted in various London communities, which for different reasons liked to use language only known in their own circles, notably wholesale markets, street traders, crime and the underworld, the docks, taxi-cab driving, and the immigrant communities. London has for centuries been extremely cosmopolitan, both as a travel hub and a place for foreign people to live and work and start their own busineses. This contributed to the development of some ‘lingua franca’ expressions, i.e., mixtures of Italian, Greek, Arabic, Yiddish (Jewish European/Hebrew dialect), Spanish and English which developed to enable understanding between people of different nationalities, rather like a pidgin or hybrid English. Certain lingua franca blended with ‘parlyaree’ or ‘polari’, which is basically underworld slang.

Backslang also contributes several slang money words. Backslang reverses the phonetic (sound of the) word, not the spelling, which can produce some strange interpretations, and was popular among market traders, butchers and greengrocers.

Here are the most common and/or interesting British slang money words and expressions, with meanings, and origins where known. Many are now obsolete; typically words which relate to pre-decimalisation coins, although some have re-emerged and continue to do so.

Some non-slang words are included where their origins are particularly interesting, as are some interesting slang money expressions which originated in other parts of the world, and which are now entering the English language.

A to Z of Money Slang

archer = two thousand pounds (£2,000), late 20th century, from the Jeffrey Archer court case in which he was alleged to have bribed call-girl Monica Coughlan with this amount.

ayrton senna/ayrton = tenner (ten pounds, £10) — cockney rhyming slang created in the 1980s or early 90s, from the name of the peerless Brazilian world champion Formula One racing driver, Ayrton Senna (1960-94), who won world titles in 1988, 90 and 91, before his tragic death at San Marino in 1994.

bag/bag of sand = grand = one thousand pounds (£1,000), seemingly recent cockney rhyming slang, in use from around the mid-1990s in Greater London; perhaps more widely too.

bar = a pound, from the late 1800s, and earlier a sovereign, probably from Romany gypsy ‘bauro’ meaning heavy or big, and also influenced by allusion to the iron bars use as trading currency used with Africans, plus a possible reference to the custom of casting of precious metal in bars.

bender = sixpence (6d) Another slang term with origins in the 1800s when the coins were actually solid silver, from the practice of testing authenticity by biting and bending the coin, which would being made of near-pure silver have been softer than the fakes.

beer tokens = money. Usually now meaning one pound coins. From the late 20th century. Alternatively beer vouchers, which commonly meant pound notes, prior to their withdrawal.

beehive = five pounds (£5). Cockney rhyming slang from 1960s and perhaps earlier since beehive has meant the number five in rhyming slang since at least the 1920s.

bees (bees and honey) = money. Cockney rhyming slang from the late 1800s. Also shortened to beesum (from bees and, bees ‘n’, to beesum).

bice/byce = two shillings (2/-) or two pounds or twenty pounds — probably from the French bis, meaning twice, which suggests usage is older than the 1900s first recorded and referenced by dictionary sources. Bice could also occur in conjunction with other shilling slang, where the word bice assumes the meaning ‘two’, as in ‘a bice of deaners’, pronounced ‘bicerdeaners’, and with other money slang, for example bice of tenners, pronounced ‘bicertenners’, meaning twenty pounds.

big ben — ten pounds (£10) the sum, and a ten pound note — cockney rhyming slang.

biscuit = £100 or £1,000. Initially suggested (Mar 2007) by a reader who tells me that the slang term ‘biscuit’, meaning £100, has been in use for several years, notably in the casino trade (thanks E). I am grateful also (thanks Paul, Apr 2007) for a further suggestion that ‘biscuit’ means £1,000 in the casino trade, which apparently is due to the larger size of the £1,000 chip. It would seem that the ‘biscuit’ slang term is still evolving and might mean different things (£100 or £1,000) to different people. I can find no other references to meanings or origins for the money term ‘biscuit’.

bob = shilling (1/-), although in recent times now means a pound or a dollar in certain regions. Historically bob was slang for a British shilling (Twelve old pence, pre-decimalisation — and twenty shillings to a pound). No plural version; it was ‘thirty bob’ not ‘thirty bobs’. Prior to 1971 bob was one of the most commonly used English slang words. Now sadly gone in the UK for this particular meaning, although lots of other meanings remain (for example the verb or noun meaning of pooh, a haircut, and the verb meaning of cheat). Usage of bob for shilling dates back to the late 1700s. Origin is not known for sure. Possibilities include a connection with the church or bell-ringing since ‘bob’ meant a set of changes rung on the bells. This would be consistent with one of the possible origins and associations of the root of the word Shilling, (from Proto-Germanic ‘skell’ meaning to sound or ring). There is possibly an association with plumb-bob, being another symbolic piece of metal, made of lead and used to mark a vertical position in certain trades, notably masons. Brewer’s 1870 Dictionary of Phrase and Fable states that ‘bob’ could be derived from ‘Bawbee’, which was 16-19th century slang for a half-penny, in turn derived from: French ‘bas billon’, meaning debased copper money (coins were commonly cut to make change). Brewer also references the Laird of Sillabawby, a 16th century mintmaster, as a possible origin. Also perhaps a connection with a plumb-bob, made of lead and used to mark a vertical position in certain trades, notably masons. ‘Bob a nob’, in the early 1800s meant ‘a shilling a head’, when estimating costs of meals, etc. In the 18th century ‘bobstick’ was a shillings-worth of gin. In parts of the US ‘bob’ was used for the US dollar coin. I am also informed (thanks K Inglott, March 2007) that bob is now slang for a pound in his part of the world (Bath, South-West England), and has also been used as money slang, presumably for Australian dollars, on the Home and Away TV soap series. A popular slang word like bob arguably develops a life of its own. Additionally (ack Martin Symington, Jun 2007) the word ‘bob’ is still commonly used among the white community of Tanzania in East Africa for the Tanzanian Shilling.

boodle = money. There are many different interpretations of boodle meaning money, in the UK and the US. Boodle normally referred to ill-gotten gains, such as counterfeit notes or the proceeds of a robbery, and also to a roll of banknotes, although in recent times the usage has extended to all sorts of money, usually in fairly large amounts. Much variation in meaning is found in the US. The origins of boodle meaning money are (according to Cassells) probably from the Dutch word ‘boedel’ for personal effects or property (a person’s worth) and/or from the old Scottish ‘bodle’ coin, worth two Scottish pence and one-sixth of an English penny, which logically would have been pre-decimalisation currency.

bottle = two pounds, or earlier tuppence (2d), from the cockney rhyming slang: bottle of spruce = deuce (= two pounds or tuppence). Spruce probably mainly refers to spruce beer, made from the shoots of spruce fir trees which is made in alcoholic and non-alcoholic varieties. Separately bottle means money generally and particularly loose coinage, from the custom of passing a bottle for people to give money to a busker or street entertainer. I am also informed (ack Sue Batch, Nov 2007) that spruce also referred to lemonade, which is perhaps another source of the bottle rhyming slang: «… around Northants, particularly the Rushden area, Spruce is in fact lemonade… it has died out nowadays — I was brought up in the 50s and 60s and it was an everyday word around my area back then. As kids growing up we always asked for a glass of spruce. It was quite an accepted name for lemonade…»

brass = money. From the 16th century, and a popular expression the north of England, e.g., ‘where there’s muck there’s brass’ which incidentally alluded to certain trades involving scrap, mess or waste which offered high earnings. This was also a defensive or retaliatory remark aimed at those of middle, higher or profesional classes who might look down on certain ‘working class’ entrepreneurs or traders. The ‘where there’s much there’s brass’ expression helped maintain and spread the populairity iof the ‘brass’ money slang, rather than cause it. Brass originated as slang for money by association to the colour of gold coins, and the value of brass as a scrap metal.

bread (bread and honey) = money. From cockney rhyming slang, bread and honey = money, and which gave rise to the secondary rhyming slang ‘poppy’, from poppy red = bread. Bread also has associations with money, which in a metaphorical sense can be traced back to the Bible. Bread meaning money is also linked with with the expression ‘earning a crust’, which alludes to having enough money to pay for one’s daily bread.

brown = a half-penny or ha’penny. An old term, probably more common in London than elsewhere, used before UK decimalisation in 1971, and before the ha’penny was withdrawn in the 1960s.

bunce = money, usually unexpected gain and extra to an agreed or predicted payment, typically not realised by the payer. Earlier English spelling was bunts or bunse, dating from the late 1700s or early 1800s (Cassells and Partridge). Origins are not certain. Bunts also used to refer to unwanted or unaccounted-for goods sold for a crafty gain by workers, and activity typically hidden from the business owner. Suggestions of origin include a supposed cockney rhyming slang shortening of bunsen burner (= earner), which is very appealing, but unlikely given the history of the word and spelling, notably that the slang money meaning pre-dated the invention of the bunsen burner, which was devised around 1857. (Thanks R Bambridge)

bung = money in the form of a bribe, from the early English meaning of pocket and purse, and pick-pocket, according to Cassells derived from Frisian (North Netherlands) pung, meaning purse. Bung is also a verb, meaning to bribe someone by giving cash.

cabbage = money in banknotes, ‘folding’ money — orginally US slang according to Cassells, from the 1900s, also used in the UK, logically arising because of the leaf allusion, and green was a common colour of dollar notes and pound notes (thanks R Maguire, who remembers the slang from Glasgow in 1970s).

carpet = three pounds (£3) or three hundred pounds (£300), or sometimes thirty pounds (£30). This has confusing and convoluted origins, from as early as the late 1800s: It seems originally to have been a slang term for a three month prison sentence, based on the following: that ‘carpet bag’ was cockney rhyming slang for a ‘drag’, which was generally used to describe a three month sentence; also that in the prison workshops it supposedly took ninety days to produce a certain regulation-size piece of carpet; and there is also a belief that prisoners used to be awarded the luxury of a piece of carpet for their cell after three year’s incarceration. The term has since the early 1900s been used by bookmakers and horse-racing, where carpet refers to odds of three-to-one, and in car dealing, where it refers to an amount of £300.

caser/case = five shillings (5/-), a crown coin. Seems to have surfaced first as caser in Australia in the mid-1800s from the Yiddish (Jewish European/Hebrew dialect) kesef meaning silver, where (in Australia) it also meant a five year prison term. Caser was slang also for a US dollar coin, and the US/Autralian slang logically transferred to English, either or all because of the reference to silver coin, dollar slang for a crown, or the comparable value, as was.

chip = a shilling (1/-) and earlier, mid-late 1800s a pound or a sovereign. According to Cassells chip meaning a shilling is from horse-racing and betting. Chip was also slang for an Indian rupee. The association with a gambling chip is logical. Chip and chipping also have more general associations with money and particularly money-related crime, where the derivations become blurred with other underworld meanings of chip relating to sex and women (perhaps from the French ‘chipie’ meaning a vivacious woman) and narcotics (in which chip refers to diluting or skimming from a consignment, as in chipping off a small piece — of the drug or the profit). Chipping-in also means to contributing towards or paying towards something, which again relates to the gambling chip use and metaphor, i.e. putting chips into the centre of the table being necessary to continue playing.

chump change = a relatively insiginificant amount of money — a recent expression (seemingly 2000s) originating in the US and now apparently entering UK usage. (Thanks M Johnson, Jan 2008)

clod = a penny (1d). Clod was also used for other old copper coins. From cockney rhyming slang clodhopper (= copper). A clod is a lump of earth. A clodhopper is old slang for a farmer or bumpkin or lout, and was also a derogatory term used by the cavalry for infantry foot soldiers.

coal = a penny (1d). Also referred to money generally, from the late 1600s, when the slang was based simply on a metaphor of coal being an essential commodity for life. The spelling cole was also used. Common use of the coal/cole slang largely ceased by the 1800s although it continued in the expressions ‘tip the cole’ and ‘post the cole’, meaning to make a payment, until these too fell out of popular use by the 1900s. It is therefore unlikely that anyone today will use or recall this particular slang, but if the question arises you’ll know the answer. Intriguingly I’ve been informed (thanks P Burns, 8 Dec 2008) that the slang ‘coal’, seemingly referring to money — although I’ve seen a suggestion of it being a euphemism for coke (cocaine) — appears in the lyrics of the song Oxford Comma by the band Vampire weekend: «Why would you lie about how much coal you have? Why would you lie about something dumb like that?…»

cock and hen = ten pounds (thanks N Shipperley). The ten pound meaning of cock and hen is 20th century rhyming slang. Cock and hen — also cockerel and hen — has carried the rhyming slang meaning for the number ten for longer. Its transfer to ten pounds logically grew more popular through the inflationary 1900s as the ten pound amount and banknote became more common currency in people’s wages and wallets, and therefore language. Cock and hen also gave raise to the variations cockeren, cockeren and hen, hen, and the natural rhyming slang short version, cock — all meaning ten pounds.

cockeren — ten pounds, see cock and hen.

commodore = fifteen pounds (£15). The origin is almost certainly London, and the clever and amusing derivation reflects the wit of Londoners: Cockney rhyming slang for five pounds is a ‘lady’, (from Lady Godiva = fiver); fifteen pounds is three-times five pounds (3x£5=£15); ‘Three Times a Lady’ is a song recorded by the group The Commodores; and there you have it: Three Times a Lady = fifteen pounds = a commodore. (Thanks Simon Ladd, Jun 2007)

coppers = pre-decimal farthings, ha’pennies and pennies, and to a lesser extent 1p and 2p coins since decimalisation, and also meaning a very small amount of money. Coppers was very popular slang pre-decimalisation (1971), and is still used in referring to modern pennies and two-penny coins, typically describing the copper (coloured) coins in one’s pocket or change, or piggy bank. Pre-decimal farthings, ha’pennies and pennies were 97% copper (technically bronze), and would nowadays be worth significantly more than their old face value because copper has become so much more valuable. Decimal 1p and 2p coins were also 97% copper (technically bronze — 97% copper, 2.5% zinc, 0.5% tin ) until replaced by copper-plated steel in 1992, which amusingly made them magnetic. The term coppers is also slang for a very small amount of money, or a cost of something typically less than a pound, usually referring to a bargain or a sum not worth thinking about, somewhat like saying ‘peanuts’ or ‘a row of beans’. For example: «What did you pay for that?» …… «Coppers.»

cows = a pound, 1930s, from the rhyming slang ‘cow’s licker’ = nicker (nicker means a pound). The word cows means a single pound since technically the word is cow’s, from cow’s licker.

daddler/dadla/dadler = threepenny bit (3d), and also earlier a farthing (quarter of an old penny, ¼d), from the early 1900s, based on association with the word tiddler, meaning something very small.

deaner/dena/denar/dener = a shilling (1/-), from the mid-1800s, derived from association with the many European dinar coins and similar, and derived in turn and associated with the Roman denarius coin which formed the basis of many European currencies and their names. The pronunciation emphasis tends to be on the long second syllable ‘aah’ sound. The expression is interpreted into Australian and New Zealand money slang as deener, again meaning shilling.

deep sea diver = fiver (£5), heard in use Oxfordshire (thanks Karen/Ewan) late 1990s, this is rhyming slang dating from the 1940s.

deuce = two pounds, and much earlier (from the 1600s) tuppence (two old pence, 2d), from the French deus and Latin duos meaning two (which also give us the deuce term in tennis, meaning two points needed to win).

dibs/dibbs = money. Dib was also US slang meaning $1 (one dollar), which presumably extended to more than one when pluralised. Origins of dib/dibs/dibbs are uncertain but probably relate to the old (early 1800s) children’s game of dibs or dibstones played with the knuckle-bones of sheep or pebbles. Also relates to (but not necessairly derived from) the expression especially used by children, ‘dibs’ meaning a share or claim of something, and dibbing or dipping among a group of children, to determine shares or winnings or who would be ‘it’ for a subsequent chasing game. In this sort of dipping or dibbing, a dipping rhyme would be spoken, coinciding with the pointing or touchung of players in turn, eliminating the child on the final word, for example:

- ‘dip dip sky blue who’s it not you’ (the word ‘you’ meant elimination for the corresponding child)

- ‘ibble-obble black bobble ibble obble out’ (‘out’ meant elimination)

- ‘one potato two potato three potato four

five potato six potato seven potato more’ (‘more’ meant elimination)

(In this final dipping/dibbing game the procedure was effectively doubled because the spoken rhythm matched the touching of each contestant’s two outstretched fists in turn with the fist of the ‘dipper’ — who incidentally included him/herself in the dipping by touching their own fists together twice, or if one of their own fists was eliminated would touch their chin. The winner or ‘it’ would be the person remaining with the last untouched fist. Players would put their fists behind their backs when touched, and interstingly I can remember that as children we would conform to the rules so diligently that our fists would remain tightly clenched behind our backs until the dipping game had finished. I guess this wouldn’t happen today because each child would need at least one hand free for holding their mobile phone and texting.)

dinarly/dinarla/dinaly = a shilling (1/-), from the mid-1800s, also transferred later to the decimal equivalent 5p piece, from the same roots that produced the ‘deaner’ shilling slang and variations, i.e., Roman denarius and then through other European dinar coins and variations. As with deanar the pronunciation emphasis tends to be on the long second syllable ‘aah’ sound.

dollar = slang for money, commonly used in singular form, eg., ‘Got any dollar?..’. In earlier times a dollar was slang for an English Crown, five shillings (5/-). From the 1900s in England and so called because the coin was similar in appearance and size to the American dollar coin, and at one time similar in value too. Brewer’s dictionary of 1870 says that the American dollar is ‘..in English money a little more than four shillings..’. That’s about 20p. The word dollar is originally derived from German ‘Thaler’, and earlier from Low German ‘dahler’, meaning a valley (from which we also got the word ‘dale’). The connection with coinage is that the Counts of Schlick in the late 1400s mined silver from ‘Joachim’s Thal’ (Joachim’s Valley), from which was minted the silver ounce coins called Joachim’s Thalers, which became standard coinage in that region of what would now be Germany. All later generic versions of the coins were called ‘Thalers’. An ‘oxford’ was cockney rhyming slang for five shillings (5/-) based on the dollar rhyming slang: ‘oxford scholar’.

dosh = slang for a reasonable amount of spending money, for instance enough for a ‘night-out’. Almost certainly and logically derived from the slang ‘doss-house’, meaning a very cheap hostel or room, from Elizabethan England when ‘doss’ was a straw bed, from ‘dossel’ meaning bundle of straw, in turn from the French ‘dossier’ meaning bundle. Dosh appears to have originated in this form in the US in the 19th century, and then re-emerged in more popular use in the UK in the mid-20th century.

doubloons = money. From the Spanish gold coins of the same name.

dough = money. From the cockney rhyming slang and metaphoric use of ‘bread’.

dunop/doonup = pound, backslang from the mid-1800s, in which the slang is created from a reversal of the word sound, rather than the spelling, hence the loose correlation to the source word.

farthing = a quarter of an old penny (¼d) — not slang, a proper word in use (in slightly different form — feorthung) since the end of the first millenium, and in this list mainly to clarify that the origin of the word is not from ‘four things’, supposedly and commonly believed from the times when coins were split to make pieces of smaller value, but actually (less excitingly) from Old English feortha, meaning fourth, corresponding to Old Frisian fiardeng, meaning a quarter of a mark, and similar Germanic words meaning four and fourth. The modern form of farthing was first recorded in English around 1280 when it altered from ferthing to farthing.

fiver = five pounds (£5), from the mid-1800s. More rarely from the early-mid 1900s fiver could also mean five thousand pounds, but arguably it remains today the most widely used slang term for five pounds.

fin/finn/finny/finnif/finnip/finnup/finnio/finnif = five pounds (£5), from the early 1800s. There are other spelling variations based on the same theme, all derived from the German and Yiddish (European/Hebrew mixture) funf, meaning five, more precisely spelled fünf. A ‘double-finnif’ (or double-fin, etc) means ten pounds; ‘half-a-fin’ (half-a-finnip, etc) would have been two pounds ten shillings (equal to £2.50).

flag = five pound note (£5), UK, notably in Manchester (ack Michael Hicks); also a USA one dollar bill; also used as a slang term for a money note in Australia although Cassells is vague about the value (if you know please contact us). The word flag has been used since the 1500s as a slang expression for various types of money, and more recently for certain notes. Originally (16th-19thC) the slang word flag was used for an English fourpenny groat coin, derived possibly from Middle Low German word ‘Vleger’ meaning a coin worth ‘more than a Bremer groat’ (Cassells). Derivation in the USA would likely also have been influenced by the slang expression ‘Jewish Flag’ or ‘Jews Flag’ for a $1 bill, from early 20th century, being an envious derogatory reference to perceived and stereotypical Jewish success in business and finance.

flim/flimsy = five pounds (£5), early 1900s, so called because of the thin and flimsy paper on which five pound notes of the time were printed.

florin/flo = a two shilling or ‘two bob’ coin (florin is actually not slang — it’s from Latin meaning flower, and a 14th century Florentine coin called the Floren). Equivalent to 10p — a tenth of a pound. A ‘flo’ is the slang shortening, meaning two shillings.