“Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things,” believed renowned management coach and author Peter F. Drucker. He used the quote to demonstrate the difference between management and leadership.

Often, it is believed that a good manager is always a good leader. However, that is not true because behaviours that make a person a good manager are often not in favour of innovation. Continue reading to know what leadership is and how it is different from management.

“The action of leading a group of people or an organisation.”

That’s how the Oxford Dictionary defines leadership. In simple words, leadership is about taking risks and challenging the status quo. Leaders motivate others to achieve something new and better. Interestingly, leaders do what they do to pursue innovation, not as an obligation. They measure success by looking at the team’s achievements and learning.

In contrast, management is about delegating responsibilities and getting people to follow the rules to reduce risk and deliver predictable outcomes. A manager is responsible for completing four critical functions: planning, organising, leading, and controlling.

Unlike leaders, managers do not challenge the status quo. Instead, they strive to maintain it. They evaluate success by seeing if the team has achieved what was expected.

Leadership vs. Management: What’s the Difference?

Leaders and managers apply different approaches to achieve their goals. For example, managers seek compliance to rules and procedures, whereas leaders thrive on breaking the norm and challenging the status quo. Here’s how leadership and management are different from each other.

-

Vision

Leaders and managers have different visions. Leaders are visionaries, whereas managers are implementers. Leaders set goals for their team. Managers ensure that the goal set by their superiors is achieved.

-

Organising vs. Aligning

Managers achieve their goals by delegating responsibilities among the team. They tactically distribute work among subordinates and organise available resources required to reach the goal.

Meanwhile, leaders motivate people. They concentrate on the personal development of their team besides working towards achieving organizational goals. They envision their team’s future growth and work towards achieving that.

-

Analysing and Assessing

A leader analyses and assesses every situation to achieve new and better results. Whereas a manager does not analyse or evaluate, they emphasise on questions like how and when, which assists them in achieving the goals. They accept and strive to achieve the status quo.

What Do Leaders Do?

Leaders are not always people who hold higher ranks in an organization. But they are people who are known for their beliefs and work ethics. A leader is passionate about their work, and they pass on their enthusiasm to their fellow workers, enabling them to achieve their goals. If you feel you do not possess the relevant skills currently, you can consider taking up one of the leadership courses or a leadership training programme.

What Are the Different Types of Leadership?

All leaders have a unique style that sets them apart from others. Hence, these different types of leadership styles will help you decide which type of leader you want to be. Accordingly, you would be able to hone your skills with the best leadership training programme. Read on.

-

Autocratic leadership

A leader who has complete control over his team is called an autocratic leader. They never bend their beliefs and rules for anyone. Additionally, their team has no say in the business decisions. Moreover, the team is expected to follow the path directed by the leader.

This archaic style of leadership has very few takers because it discourages change. And modern leaders are changing the definition of leadership and redefining what leadership is with their path-breaking decisions.

-

Laissez-Faire leadership

Laissez-Faire is derived from a French word that means ‘allow to do’. “The practice of non-interference in the affairs of others, especially with reference to individual conduct or freedom of action,’ defines dictionary.com. In this type of leadership, team members have the freedom to perform their job according to their will. They are given the freedom to bring in their perspective and intelligence in performing business functions. If you take up a leadership course, you’d get to learn about it in detail.

-

Democratic leadership

In this type of leadership, team members and leaders equally contribute to actualising business goals. Furthermore, they work together and motivate each other to achieve their personal goals too. This type of leadership leads to a positive working environment.

-

Bureaucratic leadership

In this type of leadership, leaders strictly adhere to organisational rules and policies. They make sure that their team members do the same. Bureaucratic leaders are often organised and self-motivated.

There is no right or wrong leadership style. Therefore, it is up to you to decide the kind of leader you wish to become.

What Are the Qualities of a Good Leader?

1. Honesty and Integrity: Leaders value virtuousness and honesty. They have people who believe in them and their vision.

2. Inspiration: Leaders are self-motivating, and this makes them great influencers. They are a good inspiration to their followers. They help others to understand their roles in a bigger context.

3. Communication skills: Leaders possess great communication skills. They are transparent with their team and share failures and successes with them.

4. Vision: Leaders are visionaries. They have a clear idea of what they want and how to achieve it. Being good communicators, leaders can share their vision with the team successfully.

5. Never give-up spirit: Leaders challenge the status quo. Hence, they never give up easily. They also have unique ways to solve a problem.

6. Intuitive: Leadership coach Hortense le Gentil believes that leaders should rely on intuition for making hard decisions. Especially because intuition heavily relies on a person’s existing knowledge and life learnings, which proves to be more useful in complex situations.

7. Empathy: A leader should be an emotional and empathetic fellow because it will help them in developing a strong bond with their team. Furthermore, these qualities will help a leader in addressing the problems, complaints, and aspirations of his team members.

8. Objective: Although empathy is an important quality a leader must imbibe, getting clouded by emotions while making an important business decision is not advisable. Hence, a good leader should be objective.

9. Intelligence: A good leader must be intelligent enough to arrive at business solutions to difficult problems. Furthermore, a leader should be analytical and should weigh the pros and cons before making a decision. This quality can be polished with an all-inclusive leadership training program.

10. Open-mindedness and creativity: A good leader is someone who is open to new ideas, possibilities, and perspectives. Being a good leader means understanding that there is no right way to do things. Therefore, a good leader is always ready to listen, observe, and be willing to change. They are also out-of-the-box thinkers and encourage their teams to do so. If you enrol for a leadership course, all these things will be a part of the curriculum.

11. Patient: A good leader understands that a business strategy takes time to develop and bear results. Additionally, they also believe that ‘continuous improvement and patient’ leads to success.

12. Flexible: Since leaders understand the concept of ‘continuous improvement, they also know that being adaptable will lead them to success. Nothing goes as per plan. Hence, being flexible and intuitive helps a manager to hold his ground during complex situations.

Explore Leadership Training Programmes

A good organisation needs both effective managers and leaders. The key is to match the skillset with a high-quality education degree. Emeritus believes in providing high-quality and affordable online courses across various domains, including leadership and management. They have collaborated with top-tier universities across the globe to offer quality education.

Emeritus India hosts a series of leadership courses that offer insight into the real world and help you know more about leadership. Therefore, if you wish to pursue a degree that gives you insight into becoming a good leader, enrol for an all-inclusive leadership programme.

There is no right way to determine whether someone is a good manager or a leader because the roles and responsibilities of both a manager and a leader are different. However, a good leader and a manager are the fellows who learn from their mistakes. They work on themselves and motivate others to do so. Hence, always remember the most important quality for any manager or leader is self-belief.

An APEC leader setting the tone for the 2013 APEC CEO summit with an opening speech

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to «lead», influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word «leadership» often gets viewed as a contested term.[1][2] Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the concept, sometimes contrasting Eastern and Western approaches to leadership, and also (within the West) North American versus European approaches.

U.S. academic environments define leadership as «a process of social influence in which a person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common and ethical task».[3][4] In other words, leadership can be defined as an influential power-relationship in which the power of one party (the «leader») promotes movement/change in others (the «followers»).[5] Some have challenged the more traditional managerial views of leadership (which portray leadership as something possessed or owned by one individual due to their role or authority), and instead advocate the complex nature of leadership which is found at all levels of institutions, both within formal[6] and informal roles.[7][need quotation to verify]

Studies of leadership have produced theories involving (for example) traits,[8] situational interaction, function, behavior,[9] power, vision[10]

and values,[11][need quotation to verify] charisma, and intelligence, among others.[4]

Historical views[edit]

In the field of political leadership, the Chinese doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven postulated the need for rulers to govern justly and the right of subordinates to overthrow emperors who appeared to lack divine sanction.[12]

Pro-aristocracy thinkers[13]

have postulated that leadership depends on one’s «blue blood» or genes.[14]

Monarchy takes an extreme view of the same idea, and may prop up its assertions against the claims of mere aristocrats by invoking divine sanction (see the divine right of kings). On the other hand, more democratically inclined theorists have pointed to examples of meritocratic leaders, such as the Napoleonic marshals profiting from careers open to talent.[15]

In the autocratic/paternalistic strain of thought, traditionalists recall the role of leadership of the Roman pater familias. Feminist thinking, on the other hand, may object to such models as patriarchal and posit against them «emotionally attuned, responsive, and consensual empathetic guidance, which is sometimes associated with matriarchies».[16][17]

«Comparable to the Roman tradition, the views of Confucianism on ‘right living’ relate very much to the ideal of the (male) scholar-leader and his benevolent rule, buttressed by a tradition of filial piety.»[18]

Leadership is a matter of intelligence, trustworthiness, humaneness, courage, and discipline … Reliance on intelligence alone results in rebelliousness. Exercise of humaneness alone results in weakness. Fixation on trust results in folly. Dependence on the strength of courage results in violence. Excessive discipline and sternness in command result in cruelty. When one has all five virtues together, each appropriate to its function, then one can be a leader. — Jia Lin, in commentary on Sun Tzu, Art of War[19]

Machiavelli’s The Prince, written in the early-16th century, provided a manual for rulers («princes» or «tyrants» in Machiavelli’s terminology) to gain and keep power.

Prior to the 19th century, the concept of leadership had less relevance than today—society expected and obtained traditional deference and obedience to lords, kings, master-craftsmen and slave-masters. (Note that the Oxford English Dictionary traces the word «leadership» in English only as far back as 1821.[20])

Historically, industrialization, opposition to the ancien regime and the phasing out of chattel slavery meant that some newly developing organizations (nation-state republics, commercial corporations) evolved a need for a new paradigm with which to characterize elected politicians and job-granting employers — thus the development and theorizing of the idea of «leadership».[21]

The functional relationship between leaders and followers may remain,[22]

but acceptable (perhaps euphemistic) terminology has changed.

From the 19th century too, the elaboration of anarchist thought called the whole concept of leadership into question. One response to this denial of élitism came with Leninism — Lenin (1870-1924) demanded an élite group of disciplined cadres to act as the vanguard of a socialist revolution, bringing into existence the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Other historical views of leadership have addressed the seeming contrasts between secular and religious leadership. The doctrines of Caesaro-papism have recurred and had their detractors over several centuries. Christian thinking on leadership has often emphasized stewardship of divinely-provided resources—human and material—and their deployment in accordance with a Divine plan. Compare servant leadership.[23]

For a more general view on leadership in politics, compare the concept of the statesperson.

Theories[edit]

Early western history[edit]

The search for the characteristics or traits of leaders has continued for centuries. Philosophical writings from Plato’s Republic[24] to Plutarch’s Lives have explored the question «What qualities distinguish an individual as a leader?» Underlying this search was the early recognition of the importance of leadership[25] and the assumption that leadership is rooted in the characteristics that certain individuals possess. This idea that leadership is based on individual attributes is known as the «trait theory of leadership».

A number of works in the 19th century – when the traditional authority of monarchs, lords and bishops had begun to wane – explored the trait theory at length: note especially the writings of Thomas Carlyle and of Francis Galton, whose works have prompted decades of research. In Heroes and Hero Worship (1841), Carlyle identified the talents, skills, and physical characteristics of men who rose to power. Galton’s Hereditary Genius (1869) examined leadership qualities in the families of powerful men. After showing that the numbers of eminent relatives dropped off when his focus moved from first-degree to second-degree relatives, Galton concluded that leadership was inherited. In other words, leaders were born, not developed. Both of these notable works lent great initial support for the notion that leadership is rooted in characteristics of a leader.

Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902) believed that public-spirited leadership could be nurtured by identifying young people with «moral force of character and instincts to lead», and educating them in contexts (such as the collegiate environment of the University of Oxford) which further developed such characteristics. International networks of such leaders could help to promote international understanding and help «render war impossible». This vision of leadership underlay the creation of the Rhodes Scholarships, which have helped to shape notions of leadership since their creation in 1903.[26]

Rise of alternative theories[edit]

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a series of qualitative reviews of these studies (e.g., Bird, 1940;[27] Stogdill, 1948;[28] Mann, 1959[29]) prompted researchers to take a drastically different view of the driving forces behind leadership. In reviewing the extant literature, Stogdill and Mann found that while some traits were common across a number of studies, the overall evidence suggested that people who are leaders in one situation may not necessarily be leaders in other situations. Subsequently, leadership was no longer characterized as an enduring individual trait, as situational approaches (see alternative leadership theories below) posited that individuals can be effective in certain situations, but not others. The focus then shifted away from traits of leaders to an investigation of the leader behaviors that were effective. This approach dominated much of the leadership theory and research for the next few decades.

Reemergence of trait theory[edit]

New methods and measurements were developed after these influential reviews that would ultimately reestablish trait theory as a viable approach to the study of leadership. For example, improvements in researchers’ use of the round robin research design methodology allowed researchers to see that individuals can and do emerge as leaders across a variety of situations and tasks.[30] Additionally, during the 1980s statistical advances allowed researchers to conduct meta-analyses, in which they could quantitatively analyze and summarize the findings from a wide array of studies. This advent allowed trait theorists to create a comprehensive picture of previous leadership research rather than rely on the qualitative reviews of the past. Equipped with new methods, leadership researchers revealed the following:

- Individuals can and do emerge as leaders across a variety of situations and tasks.[30]

- Significant relationships exist between leadership emergence and such individual traits as:

-

- Intelligence[31]

- Adjustment[31]

- Extraversion[31]

- Conscientiousness[32][33][34]

- Openness to experience[33][35]

- General self-efficacy[36][37]

While the trait theory of leadership has certainly regained popularity, its reemergence has not been accompanied by a corresponding increase in sophisticated conceptual frameworks.[38]

Specifically, Zaccaro (2007)[38] noted that trait theories still:

- Focus on a small set of individual attributes such as the «Big Five» personality traits, to the neglect of cognitive abilities, motives, values, social skills, expertise, and problem-solving skills.

- Fail to consider patterns or integrations of multiple attributes.

- Do not distinguish between the leadership attributes that are generally not malleable over time and those that are shaped by, and bound to, situational influences.

- Do not consider how stable leader attributes account for the behavioral diversity necessary for effective leadership.

Attribute pattern approach[edit]

Considering the criticisms of the trait theory outlined above, several researchers have begun to adopt a different perspective of leader individual differences—the leader attribute pattern approach.[37][39][40][41][42] In contrast to the traditional approach, the leader attribute pattern approach is based on theorists’ arguments that the influence of individual characteristics on outcomes is best understood by considering the person as an integrated totality rather than a summation of individual variables.[41][43] In other words, the leader attribute pattern approach argues that integrated constellations or combinations of individual differences may explain substantial variance in both leader emergence and leader effectiveness beyond that explained by single attributes, or by additive combinations of multiple attributes.

Behavioral and style theories[edit]

In response to the early criticisms of the trait approach, theorists began to research leadership as a set of behaviors, evaluating the behavior of successful leaders, determining a behavior taxonomy, and identifying broad leadership styles.[44] David McClelland, for example, posited that leadership takes a strong personality with a well-developed positive ego. To lead, self-confidence and high self-esteem are useful, perhaps even essential.[45]

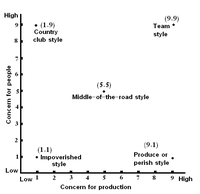

A graphical representation of the managerial grid model

Kurt Lewin, Ronald Lipitt, and Ralph White developed in 1939 the seminal work on the influence of leadership styles and performance. The researchers evaluated the performance of groups of eleven-year-old boys under different types of work climate. In each, the leader exercised his influence regarding the type of group decision making, praise and criticism (feedback), and the management of the group tasks (project management) according to three styles: authoritarian, democratic, and laissez-faire.[46]

In 1945, Ohio State University conducted a study which investigated observable behaviors portrayed by effective leaders. They would then identify if these particular behaviors are reflective of leadership effectiveness. They were able to narrow their findings to two identifiable distinctions[47] The first dimension was identified as «initiating structure», which described how a leader clearly and accurately communicates with the followers, defines goals, and determines how tasks are performed. These are considered «task oriented» behaviors. The second dimension is «consideration», which indicates the leader’s ability to build an interpersonal relationship with their followers, to establish a form of mutual trust. These are considered «social oriented» behaviors.[48]

The Michigan State Studies, which were conducted in the 1950s, made further investigations and findings that positively correlated behaviors and leadership effectiveness. Although they had similar findings as the Ohio State studies, they also contributed an additional behavior identified in leaders: participative behavior (also called «servant leadership»), or allowing the followers to participate in group decision making and encouraged subordinate input. This entails avoiding controlling types of leadership and allows more personal interactions between leaders and their subordinates.[49]

The managerial grid model is also based on a behavioral theory. The model was developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton in 1964 and suggests five different leadership styles, based on the leaders’ concern for people and their concern for goal achievement.[50]

Positive reinforcement[edit]

B. F. Skinner is the father of behavior modification and developed the concept of positive reinforcement. Positive reinforcement occurs when a positive stimulus is presented in response to a behavior, increasing the likelihood of that behavior in the future.[51] The following is an example of how positive reinforcement can be used in a business setting. Assume praise is a positive reinforcer for a particular employee. This employee does not show up to work on time every day. The manager decides to praise the employee for showing up on time every day the employee actually shows up to work on time. As a result, the employee comes to work on time more often because the employee likes to be praised. In this example, praise (the stimulus) is a positive reinforcer for this employee because the employee arrives at work on time (the behavior) more frequently after being praised for showing up to work on time. Positive reinforcement coined by Skinner enables a behavior to be repeated in a positive manner, and on the other hand a negative reinforcer is repeated in a way that is not as plausible as the positive.[52]

The use of positive reinforcement is a successful and growing technique used by leaders to motivate and attain desired behaviors from subordinates. Organizations such as Frito-Lay, 3M, Goodrich, Michigan Bell, and Emery Air Freight have all used reinforcement to increase productivity.[53] Empirical research covering the last 20 years suggests that reinforcement theory has a 17 percent increase in performance. Additionally, many reinforcement techniques such as the use of praise are inexpensive, providing higher performance for lower costs.

Situational and contingency theories[edit]

Situational theory also appeared as a reaction to the trait theory of leadership. Social scientists argued that history was more than the result of intervention of great men as Carlyle suggested. Herbert Spencer (1884) (and Karl Marx) said that the times produce the person and not the other way around.[54] This theory assumes that different situations call for different characteristics; according to this group of theories, no single optimal psychographic profile of a leader exists. According to the theory, «what an individual actually does when acting as a leader is in large part dependent upon characteristics of the situation in which he functions.»[55]

Some theorists started to synthesize the trait and situational approaches. Building upon the research of Lewin et al., academics began to normalize the descriptive models of leadership climates, defining three leadership styles and identifying which situations each style works better in. The authoritarian leadership style, for example, is approved in periods of crisis but fails to win the «hearts and minds» of followers in day-to-day management; the democratic leadership style is more adequate in situations that require consensus building; finally, the laissez-faire leadership style is appreciated for the degree of freedom it provides, but as the leaders do not «take charge», they can be perceived as a failure in protracted or thorny organizational problems.[56] Thus, theorists defined the style of leadership as contingent to the situation, which is sometimes classified as contingency theory. Three contingency leadership theories appear more prominently in recent years: Fiedler contingency model, Vroom-Yetton decision model, and the path-goal theory.

The Fiedler contingency model bases the leader’s effectiveness on what Fred Fiedler called situational contingency. This results from the interaction of leadership style and situational favorability (later called situational control). The theory defined two types of leader: those who tend to accomplish the task by developing good relationships with the group (relationship-oriented), and those who have as their prime concern carrying out the task itself (task-oriented).[57] According to Fiedler, there is no ideal leader. Both task-oriented and relationship-oriented leaders can be effective if their leadership orientation fits the situation. When there is a good leader-member relation, a highly structured task, and high leader position power, the situation is considered a «favorable situation». Fiedler found that task-oriented leaders are more effective in extremely favorable or unfavorable situations, whereas relationship-oriented leaders perform best in situations with intermediate favorability.

Victor Vroom, in collaboration with Phillip Yetton (1973)[58] and later with Arthur Jago (1988),[59] developed a taxonomy for describing leadership situations, which was used in a normative decision model where leadership styles were connected to situational variables, defining which approach was more suitable to which situation.[60] This approach was novel because it supported the idea that the same manager could rely on different group decision making approaches depending on the attributes of each situation. This model was later referred to as situational contingency theory.[61]

The path-goal theory of leadership was developed by Robert House (1971) and was based on the expectancy theory of Victor Vroom.[62] According to House, the essence of the theory is «the meta proposition that leaders, to be effective, engage in behaviors that complement subordinates’ environments and abilities in a manner that compensates for deficiencies and is instrumental to subordinate satisfaction and individual and work unit performance».[63] The theory identifies four leader behaviors, achievement-oriented, directive, participative, and supportive, that are contingent to the environment factors and follower characteristics. In contrast to the Fiedler contingency model, the path-goal model states that the four leadership behaviors are fluid, and that leaders can adopt any of the four depending on what the situation demands. The path-goal model can be classified both as a contingency theory, as it depends on the circumstances, and as a transactional leadership theory, as the theory emphasizes the reciprocity behavior between the leader and the followers.

Functional theory[edit]

General Petraeus talks with U.S. soldiers serving in Afghanistan.

Functional leadership theory (Hackman & Walton, 1986; McGrath, 1962; Adair, 1988; Kouzes & Posner, 1995) is a particularly useful theory for addressing specific leader behaviors expected to contribute to organizational or unit effectiveness. This theory argues that the leader’s main job is to see that whatever is necessary to group needs is taken care of; thus, a leader can be said to have done their job well when they have contributed to group effectiveness and cohesion (Fleishman et al., 1991; Hackman & Wageman, 2005; Hackman & Walton, 1986). While functional leadership theory has most often been applied to team leadership (Zaccaro, Rittman, & Marks, 2001), it has also been effectively applied to broader organizational leadership as well (Zaccaro, 2001). In summarizing literature on functional leadership (see Kozlowski et al. (1996), Zaccaro et al. (2001), Hackman and Walton (1986), Hackman & Wageman (2005), morge (2005), Klein, Zeigert, Knight, and Xiao (2006) observed five broad functions a leader performs when promoting organization’s effectiveness. These functions include environmental monitoring, organizing subordinate activities, teaching and coaching subordinates, motivating others, and intervening actively in the group’s work.

A variety of leadership behaviors are expected to facilitate these functions. In initial work identifying leader behavior, Fleishman (1953) observed that subordinates perceived their supervisors’ behavior in terms of two broad categories referred to as consideration and initiating structure. Consideration includes behavior involved in fostering effective relationships. Examples of such behavior would include showing concern for a subordinate or acting in a supportive manner towards others. Initiating structure involves the actions of the leader focused specifically on task accomplishment. This could include role clarification, setting performance standards, and holding subordinates accountable to those standards.

Integrated psychological theory[edit]

The Integrated Psychological Theory of leadership is an attempt to integrate the strengths of the older theories (i.e. traits, behavioral/styles, situational and functional) while addressing their limitations, introducing a new element – the need for leaders to develop their leadership presence, attitude toward others and behavioral flexibility by practicing psychological mastery. It also offers a foundation for leaders wanting to apply the philosophies of servant leadership and authentic leadership.[64]

Integrated psychological theory began to attract attention after the publication of James Scouller’s Three Levels of Leadership model (2011).[65]

Scouller argued that the older theories offer only limited assistance in developing a person’s ability to lead effectively.[66]

He pointed out, for example, that:

- Traits theories, which tend to reinforce the idea that leaders are born not made, might help us select leaders, but they are less useful for developing leaders.

- An ideal style (e.g. Blake & Mouton’s team style) would not suit all circumstances.

- Most of the situational/contingency and functional theories assume that leaders can change their behavior to meet differing circumstances or widen their behavioral range at will, when in practice many find it hard to do so because of unconscious beliefs, fears or ingrained habits. Thus, he argued, leaders need to work on their inner psychology.

- None of the old theories successfully address the challenge of developing «leadership presence»; that certain «something» in leaders that commands attention, inspires people, wins their trust and makes followers want to work with them.

Scouller proposed the Three Levels of Leadership model, which was later categorized as an «Integrated Psychological» theory on the Businessballs education website.[67] In essence, his model aims to summarize what leaders have to do, not only to bring leadership to their group or organization, but also to develop themselves technically and psychologically as leaders.

The three levels in his model are public, private and personal leadership:

- The first two – public and private leadership – are «outer» or behavioral levels. These are the behaviors that address what Scouller called «the four dimensions of leadership». These dimensions are: (1) a shared, motivating group purpose; (2) action, progress and results; (3) collective unity or team spirit; (4) individual selection and motivation. Public leadership focuses on the 34 behaviors involved in influencing two or more people simultaneously. Private leadership covers the 14 behaviors needed to influence individuals one to one.

- The third – personal leadership – is an «inner» level and concerns a person’s growth toward greater leadership presence, knowhow and skill. Working on one’s personal leadership has three aspects: (1) Technical knowhow and skill (2) Developing the right attitude toward other people – which is the basis of servant leadership (3) Psychological self-mastery – the foundation for authentic leadership.

Scouller argued that self-mastery is the key to growing one’s leadership presence, building trusting relationships with followers and dissolving one’s limiting beliefs and habits, thereby enabling behavioral flexibility as circumstances change, while staying connected to one’s core values (that is, while remaining authentic). To support leaders’ development, he introduced a new model of the human psyche and outlined the principles and techniques of self-mastery, which include the practice of mindfulness meditation.[68]

Transactional and transformational theories[edit]

Bernard Bass and colleagues developed the idea of two different types of leadership, transactional that involves exchange of labor for rewards and transformational which is based on concern for employees, intellectual stimulation, and providing a group vision.[69][70]

The transactional leader (Burns, 1978)[71] is given power to perform certain tasks and reward or punish for the team’s performance. It gives the opportunity to the manager to lead the group and the group agrees to follow his lead to accomplish a predetermined goal in exchange for something else. Power is given to the leader to evaluate, correct, and train subordinates when productivity is not up to the desired level, and reward effectiveness when expected outcome is reached.

Leader–member exchange theory[edit]

Leader–member exchange (LMX) theory addresses a specific aspect of the leadership process,[72] which evolved from an earlier theory called the vertical dyad linkage (VDL) model.[73] Both of these models focus on the interaction between leaders and individual followers. Similar to the transactional approach, this interaction is viewed as a fair exchange whereby the leader provides certain benefits such as task guidance, advice, support, and/or significant rewards and the followers reciprocate by giving the leader respect, cooperation, commitment to the task and good performance. However, LMX recognizes that leaders and individual followers will vary in the type of exchange that develops between them.[74] LMX theorizes that the type of exchanges between the leader and specific followers can lead to the creation of in-groups and out-groups. In-group members are said to have high-quality exchanges with the leader, while out-group members have low-quality exchanges with the leader.[75]

In-group members[edit]

In-group members are perceived by the leader as being more experienced, competent, and willing to assume responsibility than other followers. The leader begins to rely on these individuals to help with especially challenging tasks. If the follower responds well, the leader rewards him/her with extra coaching, favorable job assignments, and developmental experiences. If the follower shows high commitment and effort followed by additional rewards, both parties develop mutual trust, influence, and support of one another. Research shows the in-group members usually receive higher performance evaluations from the leader, higher satisfaction, and faster promotions than out-group members.[74] In-group members are also likely to build stronger bonds with their leaders by sharing the same social backgrounds and interests.

Out-group members[edit]

Out-group members often receive less time and more distant exchanges than their in-group counterparts. With out-group members, leaders expect no more than adequate job performance, good attendance, reasonable respect, and adherence to the job description in exchange for a fair wage and standard benefits. The leader spends less time with out-group members, they have fewer developmental experiences, and the leader tends to emphasize his/her formal authority to obtain compliance to leader requests. Research shows that out-group members are less satisfied with their job and organization, receive lower performance evaluations from the leader, see their leader as less fair, and are more likely to file grievances or leave the organization.[74]

Emotions[edit]

Leadership can be perceived as a particularly emotion-laden process, with emotions entwined with the social influence process.[76] In an organization, the leader’s mood has some effects on his/her group. These effects can be described in three levels:[77]

- The mood of individual group members. Group members with leaders in a positive mood experience more positive mood than do group members with leaders in a negative mood. The leaders transmit their moods to other group members through the mechanism of emotional contagion.[77] Mood contagion may be one of the psychological mechanisms by which charismatic leaders influence followers.[78]

- The affective tone of the group. Group affective tone represents the consistent or homogeneous affective reactions within a group. Group affective tone is an aggregate of the moods of the individual members of the group and refers to mood at the group level of analysis. Groups with leaders in a positive mood have a more positive affective tone than do groups with leaders in a negative mood.[77]

- Group processes like coordination, effort expenditure, and task strategy. Public expressions of mood impact how group members think and act. When people experience and express mood, they send signals to others. Leaders signal their goals, intentions, and attitudes through their expressions of moods. For example, expressions of positive moods by leaders signal that leaders deem progress toward goals to be good. The group members respond to those signals cognitively and behaviorally in ways that are reflected in the group processes.[77]

In research about client service, it was found that expressions of positive mood by the leader improve the performance of the group, although in other sectors there were other findings.[79]

Beyond the leader’s mood, her/his behavior is a source for employee positive and negative emotions at work. The leader creates situations and events that lead to emotional response. Certain leader behaviors displayed during interactions with their employees are the sources of these affective events. Leaders shape workplace affective events. Examples – feedback giving, allocating tasks, resource distribution. Since employee behavior and productivity are directly affected by their emotional states, it is imperative to consider employee emotional responses to organizational leaders.[80] Emotional intelligence, the ability to understand and manage moods and emotions in the self and others, contributes to effective leadership within organizations.[79]

Neo-emergent theory[edit]

The neo-emergent leadership theory (from the Oxford Strategic Leadership Programme[81])

sees leadership as an impression formed through the communication of information by the leader or by other stakeholders,[82]

not through the true actions of the leader himself.[citation needed] In other words, the reproduction of information or stories form the basis of the perception of leadership by the majority. It is well known by historians that the naval hero Lord Nelson often wrote his own versions of battles he was involved in, so that when he arrived home in England, he would receive a true hero’s welcome.[83] In modern society, the press, blogs and other sources report their own views of leaders, which may be based on reality, but may also be based on a political command, a payment, or an inherent interest of the author, media, or leader. Therefore, one can argue that the perception of all leaders is created and in fact does not reflect their true leadership qualities at all. Hence the historical function of belief in (for example) royal blood as a proxy for belief in or analysis of effective governing skills.

Constructivist analysis[edit]

Some constructivists question whether leadership exists, or suggest that (for example) leadership «is a myth equivalent to a belief in UFOs».[84][85]

Leadership emergence[edit]

Many personality characteristics were found to be reliably associated with leadership emergence.[86] The list includes, but is not limited to (following list organized in alphabetical order): assertiveness, authenticity, Big Five personality factors, birth order, character strengths, dominance, emotional intelligence, gender identity, intelligence, narcissism, self-efficacy for leadership, self-monitoring and social motivation.[86]

Other areas of study in relation to how and why leaders emerge include narcissistic traits, absentee leaders, and participation. While there are many personality traits that be considered in determining why a leader emerges it is important to not look at these in isolation. Today’s sophisticated research methods look at personality characteristics in combination to determine patterns of leadership emergence.[87]

Leadership emergence is the idea that people born with specific characteristics become leaders, and those without these characteristics do not become leaders. People like Mahatma Gandhi, Abraham Lincoln, and Nelson Mandela all share traits that an average person does not. This includes people who choose to participate in leadership roles, as opposed to those who do not. Research indicates that up to 30% of leader emergence has a genetic basis.[88]

There is no current research indicating that there is a “leadership gene”, instead we inherit certain traits that might influence our decision to seek leadership. Both anecdotal, and empirical evidence support a stable relationship between specific traits and leadership behavior.[89] Using a large international sample researchers found that there are three factors that motivate leaders; affective identity (enjoyment of leading), non-calculative (leading earns reinforcement), and social-normative (sense of obligation).[90]

Assertiveness[edit]

The relationship between assertiveness and leadership emergence is curvilinear; individuals who are either low in assertiveness or very high in assertiveness are less likely to be identified as leaders.[91]

Authenticity[edit]

Individuals who are more aware of their personality qualities, including their values and beliefs, and are less biased when processing self-relevant information, are more likely to be accepted as leaders.[92] See authentic leadership.

Big Five personality factors[edit]

Those who emerge as leaders tend to be more (order in strength of relationship with leadership emergence): extroverted, conscientious, emotionally stable, and open to experience, although these tendencies are stronger in laboratory studies of leaderless groups.[33] However, introversion – extroversion appears to be the most influential quality in leadership emergence, specifically leaders tend to be high in extroversion.[87] Introversion — extroversion is also the quality that can be judged most easily of the Big Five Traits.[87] Agreeableness, the last factor of the Big Five personality traits, does not seem to play any meaningful role in leadership emergence.[33]

Birth order[edit]

Those born first in their families and only children are hypothesized to be more driven to seek leadership and control in social settings. Middle-born children tend to accept follower roles in groups, and later-borns are thought to be rebellious and creative.[86]

Character strengths[edit]

Those seeking leadership positions in a military organization had elevated scores on a number of indicators of strength of character, including honesty, hope, bravery, industry, and teamwork.[93]

Dominance[edit]

Individuals with dominant personalities – they describe themselves as high in the desire to control their environment and influence other people, and are likely to express their opinions in a forceful way – are more likely to act as leaders in small-group situations.[94]

Emotional intelligence[edit]

Individuals with high emotional intelligence have increased ability to understand and relate to people. They have skills in communicating and decoding emotions and they deal with others wisely and effectively.[86] Such people communicate their ideas in more robust ways, are better able to read the politics of a situation, are less likely to lose control of their emotions, are less likely to be inappropriately angry or critical, and in consequence are more likely to emerge as leaders.[95]

Intelligence[edit]

Individuals with higher intelligence exhibit superior judgement, higher verbal skills (both written and oral), quicker learning and acquisition of knowledge, and are more likely to emerge as leaders.[86] Correlation between IQ and leadership emergence was found to be between .25 and .30.[96] However, groups generally prefer leaders that do not exceed intelligence prowess of average member by a wide margin, as they fear that high intelligence may be translated to differences in communication, trust, interests and values[97]

Self-efficacy for leadership[edit]

An individual’s belief in their ability to lead is associated with an increased willingness to accept a leadership role and find success in its pursuit.[98]

There are no set conditions for this characteristic to become emergent—it must be sustained by an individual’s belief that they have the ability to learn and improve it with time. This characteristic can be internally or externally initiated; individuals partly evaluate their own capabilities by observing others. Working with a superior who is seen as an effective leader may help the individual develop a belief that he or she can perform in a similar manner.[99]

Self-monitoring[edit]

High self-monitors are more likely to emerge as the leader of a group than are low self-monitors, since they are more concerned with status-enhancement and are more likely to adapt their actions to fit the demands of the situation[100]

[edit]

Individuals who are both success-oriented and affiliation-oriented, as assessed by projective measures, are more active in group problem-solving settings and are more likely to be elected to positions of leadership in such groups[101]

Narcissism, hubris and other negative traits[edit]

A number of negative traits of leadership have also been studied. Individuals who take on leadership roles in turbulent situations, such as groups facing a threat or ones in which status is determined by intense competition among rivals within the group, tend to be narcissistic: arrogant, self-absorbed, hostile, and very self-confident.[102]

Absentee leader[edit]

Existing research has shown that absentee leaders — those who rise into power, but not necessarily because of their skills, and are marginally engaging with their role — are actually worse than destructive leader, because it takes longer to pinpoint their mistakes.[103]

Willingness to Participate[edit]

A willingness to participate in a group can indicate a person’s interest as well as their willingness to take responsibility for how the group performs.[87] Those who do not say much during a group meeting are less likely to emerge as a leader than those who speak up.[87] There is however some debate over whether the quality of participation in a group matters more than the quantity.

A hypothesis termed, the ‘babble effect’ or the ‘babble hypotheses’ has been studied as a factor in the emergence of leaders.[104] It is believed that leader emergence is highly correlated with the quantity of speaking time, specifically those who provide a large quantity are more likely to become a leader in a group setting.[105] It is also believed that the quantity of participation is more important that the quality of these contributions when it comes to leader emergence.[87]

Research has shown the largest contributor to discussion in a group is more likely to become the leader.[104] However, some studies indicate that there must be some element of quality combined with quantity to support leader emergence. Thus, while sheer quantity does matter to leadership, when the contributions made are also of high-quality leader emergence is further facilitated.[106]

Leadership styles[edit]

A leadership style is a leader’s style of providing direction, implementing plans, and motivating people. It is the result of the philosophy, personality, and experience of the leader. Rhetoric specialists have also developed models for understanding leadership (Robert Hariman, Political Style,[107] Philippe-Joseph Salazar, L’Hyperpolitique. Technologies politiques De La Domination[108]).

Different situations call for different leadership styles. In an emergency when there is little time to converge on an agreement and where a designated authority has significantly more experience or expertise than the rest of the team, an autocratic leadership style may be most effective; however, in a highly motivated and aligned team with a homogeneous level of expertise, a more democratic or laissez-faire style may be more effective. The style adopted should be the one that most effectively achieves the objectives of the group while balancing the interests of its individual members.[109]

A field in which leadership style has gained strong attention is that of military science, recently expressing a holistic and integrated view of leadership, including how a leader’s physical presence determines how others perceive that leader. The factors of physical presence are military bearing, physical fitness, confidence, and resilience. The leader’s intellectual capacity helps to conceptualize solutions and acquire knowledge to do the job. A leader’s conceptual abilities apply agility, judgment, innovation, interpersonal tact, and domain knowledge. Domain knowledge for leaders encompasses tactical and technical knowledge as well as cultural and geopolitical awareness.[110]

[edit]

Under the autocratic leadership style, all decision-making powers are centralized in the leader, as with dictators.

Autocratic leaders do not ask or entertain any suggestions or initiatives from subordinates. The autocratic management has been successful as it provides strong motivation to the manager. It permits quick decision-making, as only one person decides for the whole group and keeps each decision to him/herself until he/she feels it needs to be shared with the rest of the group.[109]

Participative or democratic[edit]

The democratic leadership style consists of the leader sharing the decision-making abilities with group members by promoting the interests of the group members and by practicing social equality. This has also been called shared leadership.

Laissez-faire or free-rein leadership[edit]

In laissez-faire or free-rein leadership, decision-making is passed on to the subordinates. This style of leadership is known as «laissez faire» which means no interference in the affairs of others. (The phrase laissez-faire is French and literally means «let them do»). Subordinates are given the complete right and power to make decisions to establish goals and work out the problems or hurdles.[111]

The followers are given a high degree of independence and freedom to formulate their own objectives and ways to achieve them.

Task-oriented and relationship-oriented[edit]

Task-oriented leadership is a style in which the leader is focused on the tasks that need to be performed in order to meet a certain production goal. Task-oriented leaders are generally more concerned with producing a step-by-step solution for given problem or goal, strictly making sure these deadlines are met, results and reaching target outcomes.

Relationship-oriented leadership is a contrasting style in which the leader is more focused on the relationships amongst the group and is generally more concerned with the overall well-being and satisfaction of group members.[112] Relationship-oriented leaders emphasize communication within the group, show trust and confidence in group members, and show appreciation for work done.

Task-oriented leaders are typically less concerned with the idea of catering to group members, and more concerned with acquiring a certain solution to meet a production goal. For this reason, they typically are able to make sure that deadlines are met, yet their group members’ well-being may suffer. These leaders have absolute focus on the goal and the tasks cut out for each member. Relationship-oriented leaders are focused on developing the team and the relationships in it. The positives to having this kind of environment are that team members are more motivated and have support. However, the emphasis on relations as opposed to getting a job done might make productivity suffer

Paternalism[edit]

Paternalism leadership styles often reflect a father-figure mindset. The structure of team is organized hierarchically where the leader is viewed above the followers. The leader also provides both professional and personal direction in the lives of the members.[113] There is often a limitation on the choices that the members can choose from due to the heavy direction given by the leader.

The term paternalism is from the Latin pater meaning «father». The leader is most often a male. This leadership style is often found in Russia, Africa, and Pacific Asian Societies.[113]

Servant leadership[edit]

With the transformation into a knowledge society, the concept of servant leadership has become more popular, notably through modern technology management styles such as Agile. In this style, the leadership is externalized from the leader who serves as a guardian of the methodology and a «servant» or service provider to the team they lead. The cohesion and common direction of the team is dictated by a common culture, common goals and sometimes a specific methodology. This style is different from the laissez-faire in that the leader constantly works towards reaching the common goals as a team, but without giving explicit directions on tasks.

Leadership differences affected by gender[edit]

Another factor that covaries with leadership style is whether the person is male or female. When men and women come together in groups, they tend to adopt different leadership styles. Men generally assume an agentic leadership style. They are task-oriented, active, decision focused, independent and goal oriented. Women, on the other hand, are generally more communal when they assume a leadership position; they strive to be helpful towards others, warm in relation to others, understanding, and mindful of others’ feelings. In general, when women are asked to describe themselves to others in newly formed groups, they emphasize their open, fair, responsible, and pleasant communal qualities. They give advice, offer assurances, and manage conflicts in an attempt to maintain positive relationships among group members. Women connect more positively to group members by smiling, maintaining eye contact and respond tactfully to others’ comments. Men, conversely, describe themselves as influential, powerful and proficient at the task that needs to be done. They tend to place more focus on initiating structure within the group, setting standards and objectives, identifying roles, defining responsibilities and standard operating procedures, proposing solutions to problems, monitoring compliance with procedures, and finally, emphasizing the need for productivity and efficiency in the work that needs to be done. As leaders, men are primarily task-oriented, but women tend to be both task- and relationship-oriented. However, it is important to note that these sex differences are only tendencies, and do not manifest themselves within men and women across all groups and situations.[87] Meta-analyses show that people associate masculinity and agency more strongly with leadership than femininity and communion.[114] Such stereotypes may have an effect on leadership evaluations of men and women.[115][116]

In times of crisis, women tend to lead better than men due to a show of empathy and confidence during briefings and other forms of communication. This has been critical during the COVID-19 pandemic as female governed states showed fewer deaths than male led states.[117]

Barriers for non-western female leaders[edit]

Many reasons can contribute to the barriers that specifically affect women’s entrance into leadership. These barriers also change according to different cultures. Despite the increasing number of female leaders in the world, only a small fraction come from non-westernized cultures. It is important to note that although the barriers listed below may be more severe in non-western culture, it does not imply that westernized cultures do not have these barriers as well. This aims to compare the differences between the two.

Research and Literature

Although there have been many studies done on leadership for women in the past decade, very little research has been done for women in paternalistic cultures. The literature and research done for women to emerge into a society that prefers males is lacking. This ultimately hinders women from knowing how to reach their individual leadership goals, and fails to educate the male counterparts in this disparity.[118]

Maternity Leave

Studies have shown the importance of longer paid maternity leave and the positive effects it has on a female employee’s mental health and return to work. In Sweden, it was shown that the increased flexibility in timing for mothers to return to work decreased the odds of poor mental health reports. In non-western cultures that mostly follow paternalism, lack of knowledge on the benefits of maternity leave impacts the support given to the women during an important time in their life.[119]

Society and Laws

Certain countries that follow paternalism, such as India, still allow for women to be treated unjustly. Issues such as child marriage and minor punishments for perpetrators in crimes against women shape society’s view on how women should be treated. This can prevent women from feeling comfortable speaking out in personal and professional settings.[120]

Glass Ceilings and Glass Cliffs

Women who work in a very paternalistic culture or industry (e.g. the oil or engineering industry), often deal with limitations in their career that prevent them from moving up any further. This association is often due to the mentality that only males carry leadership characteristics. The term glass cliff refers to undesired projects that are often given to women because they have an increase in risk of failure. These undesired projects are given to female employees where they are more likely to fail and leave the organization.[121]

Performance[edit]

In the past, some researchers have argued that the actual influence of leaders on organizational outcomes is overrated and romanticized as a result of biased attributions about leaders (Meindl & Ehrlich, 1987). Despite these assertions, however, it is largely recognized and accepted by practitioners and researchers that leadership is important, and research supports the notion that leaders do contribute to key organizational outcomes[122][need quotation to verify][123]

To facilitate successful performance it is important to understand and accurately measure leadership performance.

Job performance generally refers to behavior that is expected to contribute to organizational success (Campbell, 1990). Campbell identified a number of specific types of performance dimensions; leadership was one of the dimensions that he identified. There is no consistent, overall definition of leadership performance (Yukl, 2006). Many distinct conceptualizations are often lumped together under the umbrella of leadership performance, including outcomes such as leader effectiveness, leader advancement, and leader emergence (Kaiser et al., 2008). For instance, «leadership performance» may refer to the career success of the individual leader, performance of the group or organization, or even leader emergence. Each of these measures can be considered conceptually distinct. While these aspects may be related, they are different outcomes and their inclusion should depend on the applied or research focus.[124][125]

«Another way to conceptualize leader performance is to focus on the outcomes of the leader’s followers, group, team, unit, or organization. In evaluating this type of leader performance, two general strategies are typically used. The first relies on subjective perceptions of the leader’s performance from subordinates, superiors, or occasionally peers or other parties. The other type of effectiveness measures are more objective indicators of follower or unit performance, such as measures of productivity, goal attainment, sales figures, or unit financial performance (Bass & Riggio, 2006, p. 47).»

[126]

A toxic leader is someone who has responsibility over a group of people or an organization, and who abuses the leader–follower relationship by leaving the group or organization in a worse-off condition than when he/she joined it.[127]

Measuring leadership[edit]

Measuring leadership has proven difficult and complex — even impossible.[128]

Attempts to assess leadership performance via group performance bring in multifarious different factors. Different perceptions of leadership itself may lead to differing measuring methods.[129]

Nevertheless, leadership theoreticians have proven perversely reluctant to abandon the vague subjective qualitative popular concept of «leaders».[130]

Traits[edit]

Most theories in the 20th century argued that great leaders were born, not made. Current studies have indicated that leadership is much more complex and cannot be boiled down to a few key traits of an individual. Years of observation and study have indicated that one such trait or a set of traits does not make an extraordinary leader. What scholars have been able to arrive at is that leadership traits of an individual do not change from situation to situation; such traits include intelligence, assertiveness, or physical attractiveness.[131] However, each key trait may be applied to situations differently, depending on the circumstances. The following summarizes the main leadership traits found in research by Jon P. Howell, business professor at New Mexico State University and author of the book Snapshots of Great Leadership.

Determination and drive include traits such as initiative, energy, assertiveness, perseverance and sometimes dominance. People with these traits often tend to wholeheartedly pursue their goals, work long hours, are ambitious, and often are very competitive with others. Cognitive capacity includes intelligence, analytical and verbal ability, behavioral flexibility, and good judgment. Individuals with these traits are able to formulate solutions to difficult problems, work well under stress or deadlines, adapt to changing situations, and create well-thought-out plans for the future. Howell provides examples of Steve Jobs and Abraham Lincoln as encompassing the traits of determination and drive as well as possessing cognitive capacity, demonstrated by their ability to adapt to their continuously changing environments.[131]

Self-confidence encompasses the traits of high self-esteem, assertiveness, emotional stability, and self-assurance. Individuals who are self-confident do not doubt themselves or their abilities and decisions; they also have the ability to project this self-confidence onto others, building their trust and commitment. Integrity is demonstrated in individuals who are truthful, trustworthy, principled, consistent, dependable, loyal, and not deceptive. Leaders with integrity often share these values with their followers, as this trait is mainly an ethics issue. It is often said that these leaders keep their word and are honest and open with their cohorts. Sociability describes individuals who are friendly, extroverted, tactful, flexible, and interpersonally competent. Such a trait enables leaders to be accepted well by the public, use diplomatic measures to solve issues, as well as hold the ability to adapt their social persona to the situation at hand. According to Howell, Mother Teresa is an exceptional example who embodies integrity, assertiveness, and social abilities in her diplomatic dealings with the leaders of the world.[131]

Few great leaders encompass all of the traits listed above, but many have the ability to apply a number of them to succeed as front-runners of their organization or situation.

Ontological-phenomenological model[edit]

One of the more recent definitions of leadership comes from Werner Erhard, Michael C. Jensen, Steve Zaffron, and Kari Granger who describe leadership as «an exercise in language that results in the realization of a future that was not going to happen anyway, which future fulfills (or contributes to fulfilling) the concerns of the relevant parties…». This definition ensures that leadership is talking about the future and includes the fundamental concerns of the relevant parties. This differs from relating to the relevant parties as «followers» and calling up an image of a single leader with others following. Rather, a future that fulfills on the fundamental concerns of the relevant parties indicates the future that was not going to happen is not the «idea of the leader», but rather is what emerges from digging deep to find the underlying concerns of those who are impacted by the leadership.[132]

Contexts[edit]

Organizations[edit]

An organization that is established as an instrument or means for achieving defined objectives has been referred to by sociologists as a formal organization. Its design specifies how goals are subdivided and reflected in subdivisions of the organization.[133] Divisions, departments, sections, positions, jobs, and tasks make up this work structure. Thus, the formal organization is expected to behave impersonally in regard to relationships with clients or with its members. According to Weber’s model, entry and subsequent advancement is by merit or seniority. Employees receive a salary and enjoy a degree of tenure that safeguards them from the arbitrary influence of superiors or of powerful clients. The higher one’s position in the hierarchy, the greater one’s presumed expertise in adjudicating problems that may arise in the course of the work carried out at lower levels of the organization. This bureaucratic structure forms the basis for the appointment of heads or chiefs of administrative subdivisions in the organization and endows them with the authority attached to their position.[134]

In contrast to the appointed head or chief of an administrative unit, a leader emerges within the context of the informal organization that underlies the formal structure.[135] The informal organization expresses the personal objectives and goals of the individual membership. Their objectives and goals may or may not coincide with those of the formal organization. The informal organization represents an extension of the social structures that generally characterize human life—the spontaneous emergence of groups and organizations as ends in themselves.

In prehistoric times, humanity was preoccupied with personal security, maintenance, protection, and survival.[136] Now humanity spends a major portion of waking hours working for organizations. The need to identify with a community that provides security, protection, maintenance, and a feeling of belonging has continued unchanged from prehistoric times. This need is met by the informal organization and its emergent, or unofficial, leaders.[137][138][need quotation to verify]

Leaders emerge from within the structure of the informal organization.[139] Their personal qualities, the demands of the situation, or a combination of these and other factors attract followers who accept their leadership within one or several overlay structures. Instead of the authority of position held by an appointed head or chief, the emergent leader wields influence or power. Influence is the ability of a person to gain co-operation from others by means of persuasion or control over rewards. Power is a stronger form of influence because it reflects a person’s ability to enforce action through the control of a means of punishment.[137]

A leader is a person who influences a group of people towards a specific result. In this scenario, leadership is not dependent on title or formal authority.[140] Ogbonnia (2007) defines an effective leader «as an individual with the capacity to consistently succeed in a given condition and be viewed as meeting the expectations of an organization or society».[page needed] John Hoyle argues that leaders are recognized by their capacity for caring for others, clear communication, and a commitment to persist.[141] An individual who is appointed to a managerial position has the right to command and enforce obedience by virtue of the authority of their position. However, she or he must possess adequate personal attributes to match this authority, because authority is only potentially available to him/her. In the absence of sufficient personal competence, a manager may be confronted by an emergent leader who can challenge her/his role in the organization and reduce it to that of a figurehead. However, only authority of position has the backing of formal sanctions. It follows that whoever wields personal influence and power can legitimize this only by gaining a formal position in a hierarchy, with commensurate authority.[137] Leadership can be defined as one’s ability to get others to willingly follow. Every organization needs leaders at every level.[142][need quotation to verify]

Management[edit]

Over the years the terms «management» and «leadership» have, in the organizational context, been used both as synonyms and with clearly differentiated meanings. Debate is fairly common about whether the use of these terms should be restricted, and reflects an awareness of the distinction made by Burns (1978) between «transactional» leadership (characterized by emphasis on procedures, contingent reward, management by exception) and «transformational» leadership (characterized by charisma, personal relationships, creativity).[71] Leaders are the very role that can try to deal with the trust issues and issues derived from lacking trust.[143]

Group[edit]

In contrast to individual leadership, some organizations have adopted group leadership. In this so-called shared leadership, more than one person provides direction to the group as a whole. It is furthermore characterized by shared responsibility, cooperation and mutual influence among team members.[144] Some organizations have taken this approach in hopes of increasing creativity, reducing costs, or downsizing. Others may see the traditional leadership of a boss as costing too much in team performance. In some situations, the team members best able to handle any given phase of the project become the temporary leaders. Additionally, as each team member has the opportunity to experience the elevated level of empowerment, it energizes staff and feeds the cycle of success.[145]

Leaders who demonstrate persistence, tenacity, determination, and synergistic communication skills will bring out the same qualities in their groups. Good leaders use their own inner mentors to energize their team and organizations and lead a team to achieve success.[146]

According to the National School Boards Association (US):[citation needed]

These Group Leaderships or Leadership Teams have specific characteristics:

Characteristics of a Team

- There must be an awareness of unity on the part of all its members.

- There must be interpersonal relationship. Members must have a chance to contribute, and learn from and work with others.

- The members must have the ability to act together toward a common goal.

Ten characteristics of well-functioning teams:

- Purpose: Members proudly share a sense of why the team exists and are invested in accomplishing its mission and goals.

- Priorities: Members know what needs to be done next, by whom, and by when to achieve team goals.

- Roles: Members know their roles in getting tasks done and when to allow a more skillful member to do a certain task.

- Decisions: Authority and decision-making lines are clearly understood.

- Conflict: Conflict is dealt with openly and is considered important to decision-making and personal growth.

- Personal traits: members feel their unique personalities are appreciated and well utilized.

- Norms: Group norms for working together are set and seen as standards for every one in the groups.

- Effectiveness: Members find team meetings efficient and productive and look forward to this time together.

- Success: Members know clearly when the team has met with success and share in this equally and proudly.

- Training: Opportunities for feedback and updating skills are provided and taken advantage of by team members.

Self-leadership[edit]

Self-leadership is a process that occurs within an individual, rather than an external act. It is an expression of who we are as people.[147][need quotation to verify] Self-leadership is having a developed sense of who you are, what you can achieve, what are your goals coupled with the ability to affect your emotions, behaviors and communication. At the center of leadership is the person who is motivated to make the difference. Self-leadership is a way toward more effectively leading other people.[148][need quotation to verify]

Biology and evolution of leadership[edit]

Mark van Vugt and Anjana Ahuja in Naturally Selected: The Evolutionary Science of Leadership (2011) present cases of leadership in non-human animals, from ants and bees to baboons and chimpanzees. They suggest that leadership has a long evolutionary history and that the same mechanisms underpinning leadership in humans appear in other social species, too.[149] They also suggest that the evolutionary origins of leadership differ from those of dominance. In a study, Mark van Vugt and his team looked at the relation between basal testosterone and leadership versus dominance. They found that testosterone correlates with dominance but not with leadership. This was replicated in a sample of managers in which there was no relation between hierarchical position and testosterone level.[150]

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, in Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence (1996), present evidence that only humans and chimpanzees, among all the animals living on Earth, share a similar tendency for a cluster of behaviors: violence, territoriality, and competition for uniting behind the one chief male of the land.[151] This position is contentious.[citation needed] Many animals apart from apes are territorial, compete, exhibit violence, and have a social structure controlled by a dominant male (lions, wolves, etc.), suggesting Wrangham and Peterson’s evidence is not empirical. However, we must examine other species as well, including elephants (which are matriarchal and follow an alpha female), meerkats (which are likewise matriarchal), sheep (which «follow» in some sense castrated bellwethers), and many others.

By comparison, bonobos, the second-closest species-relatives of humans, do not unite behind the chief male of the land. Bonobos show deference to an alpha or top-ranking female that, with the support of her coalition of other females, can prove as strong as the strongest male. Thus, if leadership amounts to getting the greatest number of followers, then among the bonobos, a female almost always exerts the strongest and most effective leadership. (Incidentally, not all scientists agree on the allegedly peaceful nature of the bonobo or with its reputation as a «hippie chimp».[152])

Myths[edit]

Leadership, although largely talked about, has been described as one of the least understood concepts across all cultures and civilizations. Over the years, many researchers have stressed the prevalence of this misunderstanding, stating that the existence of several flawed assumptions, or myths, concerning leadership often interferes with individuals’ conception of what leadership is all about (Gardner, 1965; Bennis, 1975).[153][154]

Leadership is innate[edit]

According to some, leadership is determined by distinctive dispositional characteristics present at birth (e.g., extraversion; intelligence; ingenuity). However, according to Forsyth (2009) there is evidence to show that leadership also develops through hard work and careful observation.[155] Thus, effective leadership can result from nature (i.e., innate talents) as well as nurture (i.e., acquired skills).

Leadership is possessing power over others[edit]