На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

The feat represents a first crude step toward a practical atomic-scale memory where atoms would represent the bits of information that make up the words, pictures and codes read by computers.

Их исследования представляют собой первый и еще «грубый» шаг на пути к воплощению устройства памяти в масштабе атома, где сами атомы представляли бы биты информации, которые составляют слова, картинки и коды, читаемые компьютерами.

We’ll have to make up the words to this one.

I don’t make up the words.

Or sit here and make up the words

Результатов: 284100. Точных совпадений: 4. Затраченное время: 1327 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Subjects>Jobs & Education>Education

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

Best Answer

Copy

neologism

Wiki User

∙ 13y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the word that means a made up word?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

Morphemes. The Structure of the English Word Lecture 2

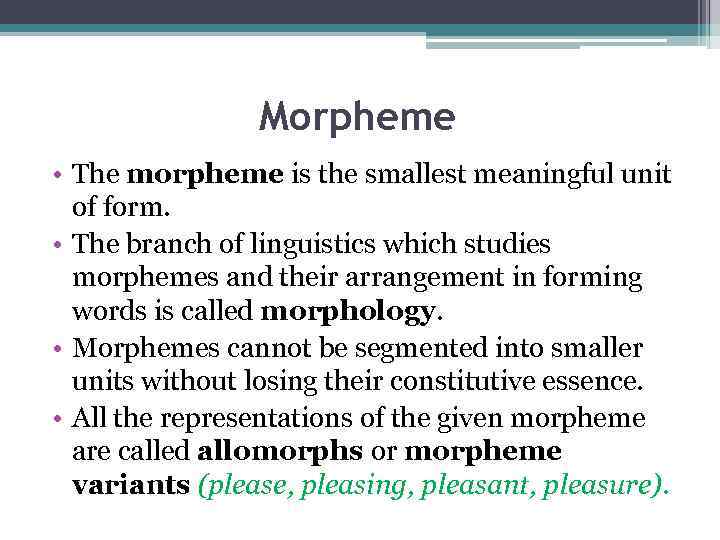

Morpheme • The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit of form. • The branch of linguistics which studies morphemes and their arrangement in forming words is called morphology. • Morphemes cannot be segmented into smaller units without losing their constitutive essence. • All the representations of the given morpheme are called allomorphs or morpheme variants (please, pleasing, pleasant, pleasure).

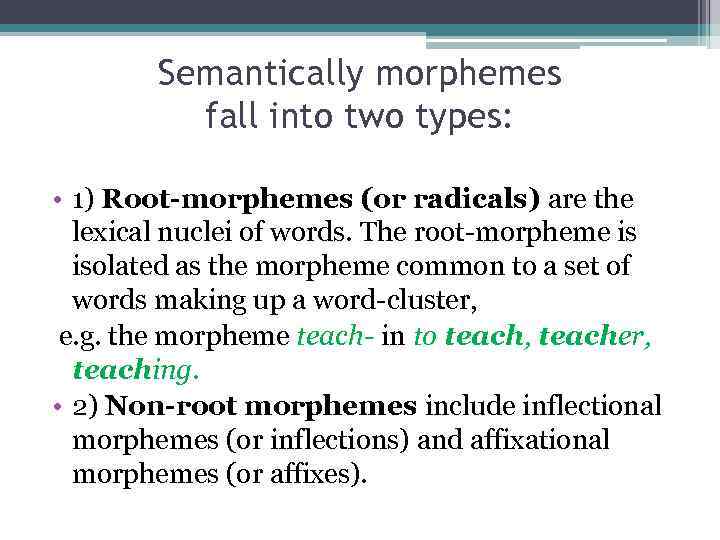

Semantically morphemes fall into two types: • 1) Root-morphemes (or radicals) are the lexical nuclei of words. The root-morpheme is isolated as the morpheme common to a set of words making up a word-cluster, e. g. the morpheme teach- in to teach, teacher, teaching. • 2) Non-root morphemes include inflectional morphemes (or inflections) and affixational morphemes (or affixes).

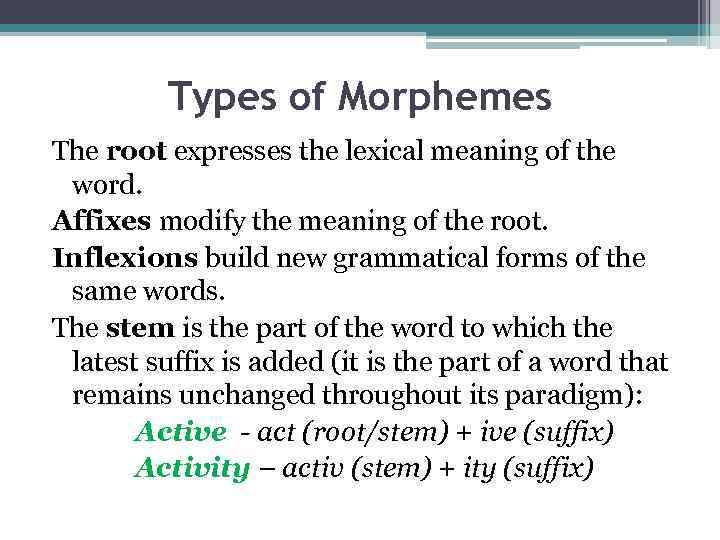

Types of Morphemes The root expresses the lexical meaning of the word. Affixes modify the meaning of the root. Inflexions build new grammatical forms of the same words. The stem is the part of the word to which the latest suffix is added (it is the part of a word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm): Active — act (root/stem) + ive (suffix) Activity – activ (stem) + ity (suffix)

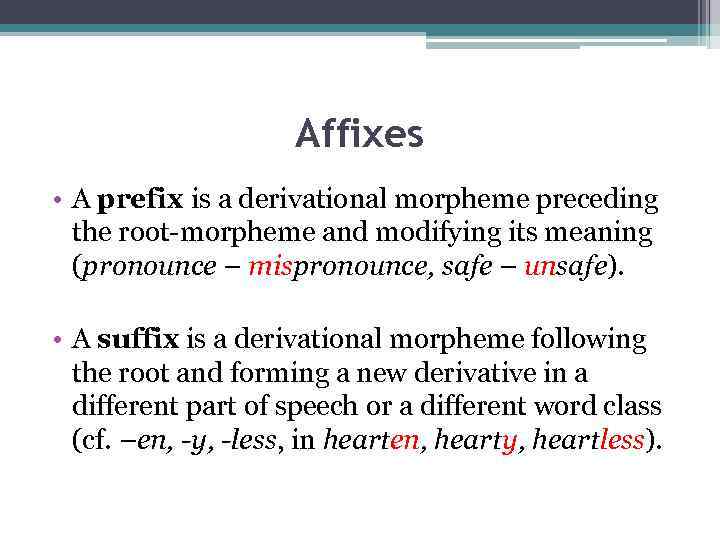

Affixes • A prefix is a derivational morpheme preceding the root-morpheme and modifying its meaning (pronounce – mispronounce, safe – unsafe). • A suffix is a derivational morpheme following the root and forming a new derivative in a different part of speech or a different word class (cf. –en, -y, -less, in hearten, hearty, heartless).

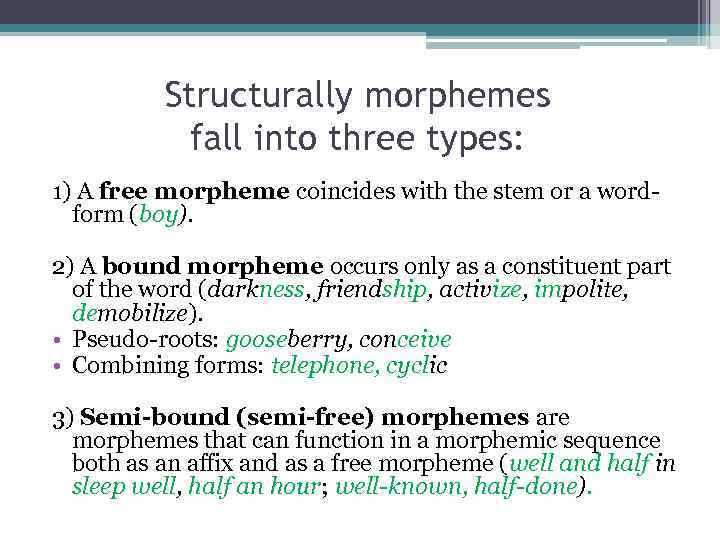

Structurally morphemes fall into three types: 1) A free morpheme coincides with the stem or a wordform (boy). 2) A bound morpheme occurs only as a constituent part of the word (darkness, friendship, activize, impolite, demobilize). • Pseudo-roots: gooseberry, conceive • Combining forms: telephone, cyclic 3) Semi-bound (semi-free) morphemes are morphemes that can function in a morphemic sequence both as an affix and as a free morpheme (well and half in sleep well, half an hour; well-known, half-done).

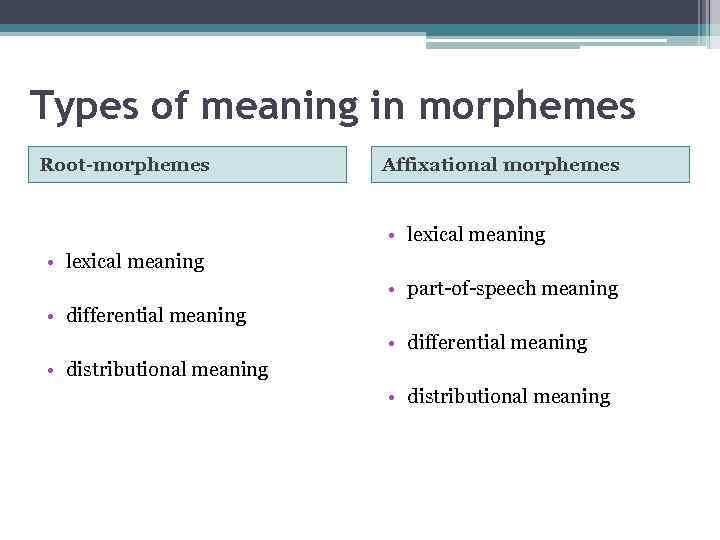

Types of meaning in morphemes Root-morphemes Affixational morphemes • lexical meaning • part-of-speech meaning • differential meaning • distributional meaning

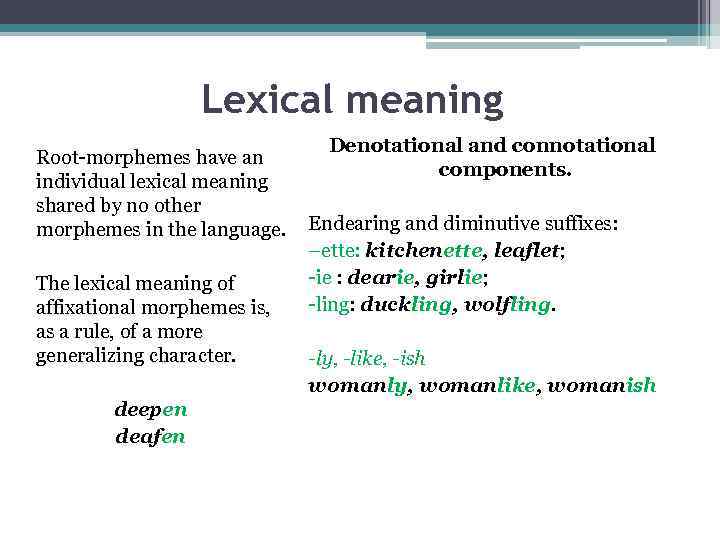

Lexical meaning Denotational and connotational Root-morphemes have an components. individual lexical meaning shared by no other morphemes in the language. Endearing and diminutive suffixes: –ette: kitchenette, leaflet; -ie : dearie, girlie; The lexical meaning of -ling: duckling, wolfling. affixational morphemes is, as a rule, of a more generalizing character. -ly, -like, -ish womanly, womanlike, womanish deepen deafen

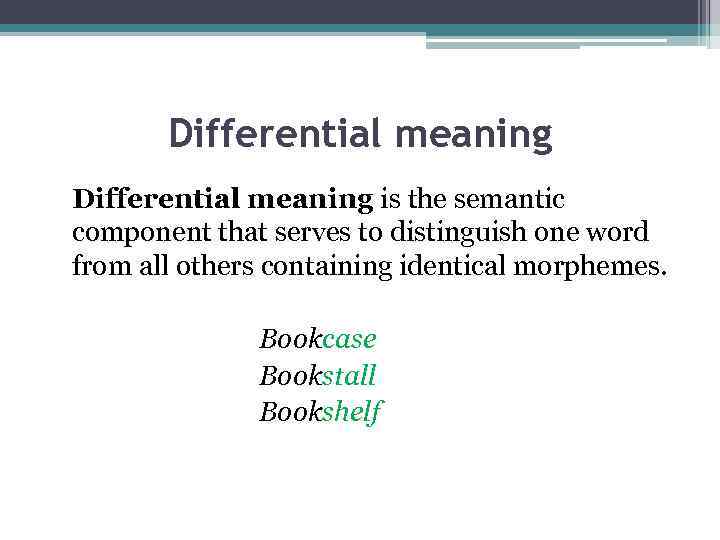

Differential meaning is the semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes. Bookcase Bookstall Bookshelf

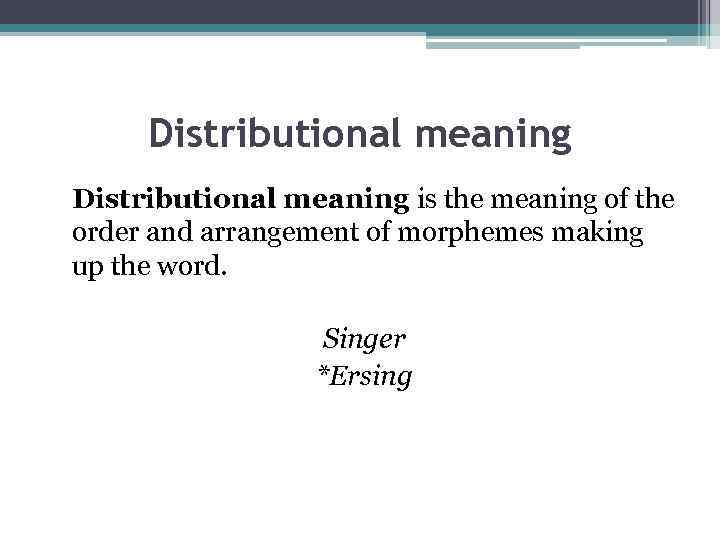

Distributional meaning is the meaning of the order and arrangement of morphemes making up the word. Singer *Ersing

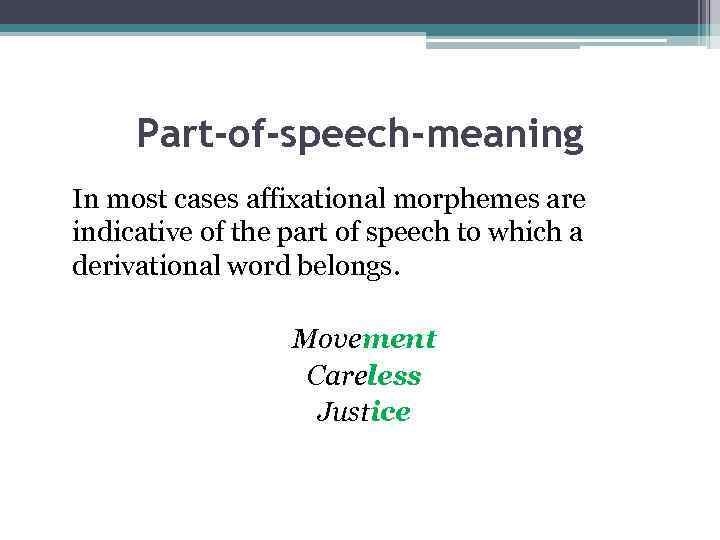

Part-of-speech-meaning In most cases affixational morphemes are indicative of the part of speech to which a derivational word belongs. Movement Careless Justice

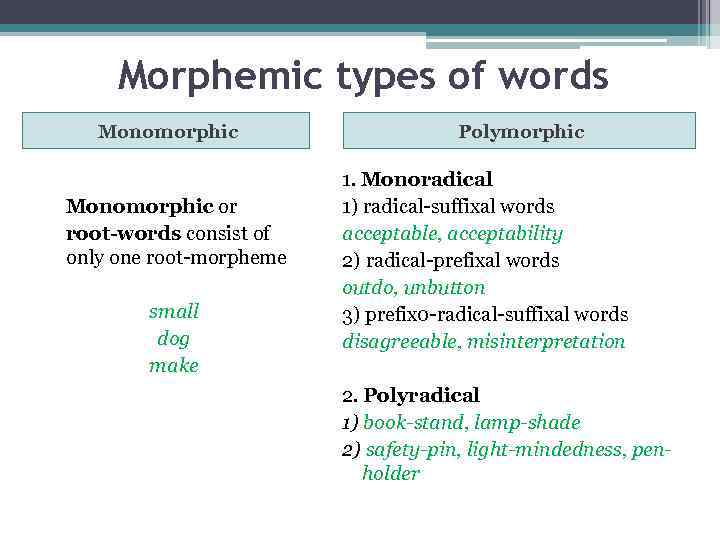

Morphemic types of words Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme small dog make Polymorphic 1. Monoradical 1) radical-suffixal words acceptable, acceptability 2) radical-prefixal words outdo, unbutton 3) prefix 0 -radical-suffixal words disagreeable, misinterpretation 2. Polyradical 1) book-stand, lamp-shade 2) safety-pin, light-mindedness, penholder

Word-segmentability • Complete segmentability • Conditional segmentability • Defective segmentability

Complete segmentability is characteristic of a great number of words, the morphemic structure of which is transparent enough, as their individual morphemes clearly stand out within the word and can be easily isolated. morphemes proper or full morphemes endless, useless an end, to end; use, to use; nameless, powerless

Conditional segmentabilty characterizes words whose segmentational morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons. pseudo-morphemes or quasi-morphemes [ri-], [di-] [-tein], [-si: v] retain, detain, receive, deceive rewrite, reorganize, decode, deorganize. retain detain receive

Defective segmentability is the property of words whose component morphemes seldom or never occur in other words. hamlet ringlet, leaflet, streamlet

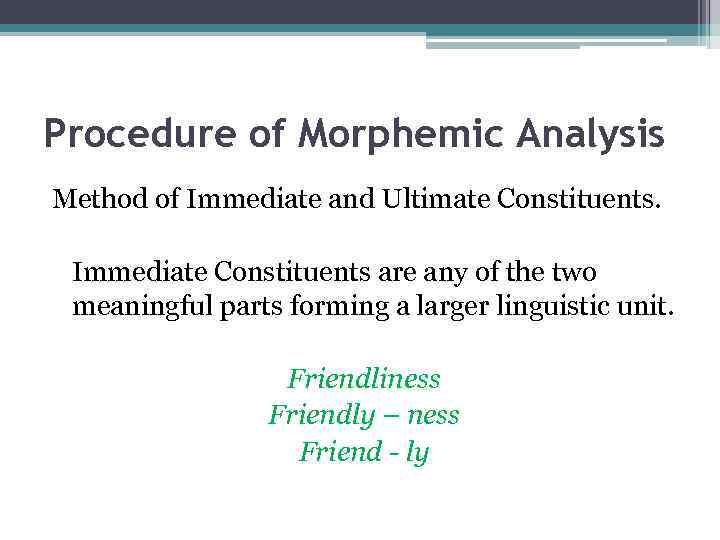

Procedure of Morphemic Analysis Method of Immediate and Ultimate Constituents. Immediate Constituents are any of the two meaningful parts forming a larger linguistic unit. Friendliness Friendly – ness Friend — ly

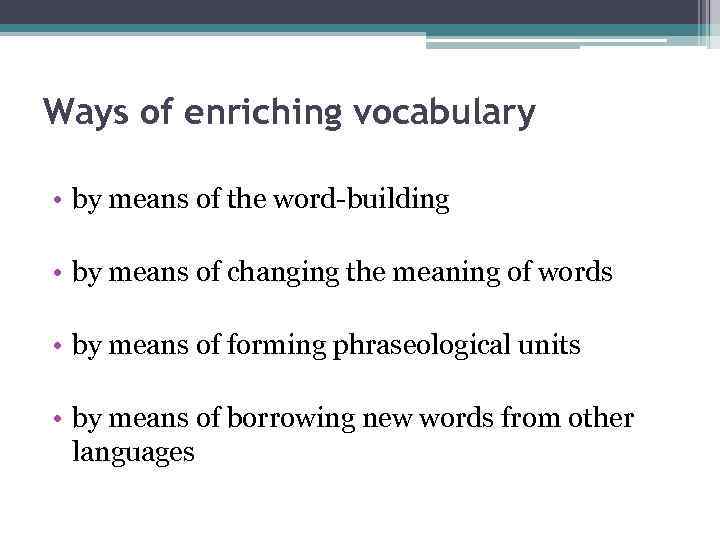

Ways of enriching vocabulary • by means of the word-building • by means of changing the meaning of words • by means of forming phraseological units • by means of borrowing new words from other languages

Enriching Vocabulary

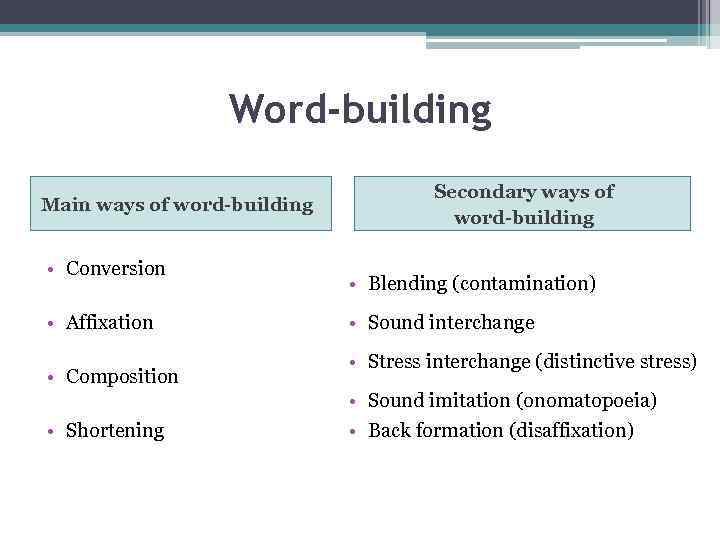

Word-building Main ways of word-building • Conversion • Affixation • Composition • Shortening Secondary ways of word-building • Blending (contamination) • Sound interchange • Stress interchange (distinctive stress) • Sound imitation (onomatopoeia) • Back formation (disaffixation)

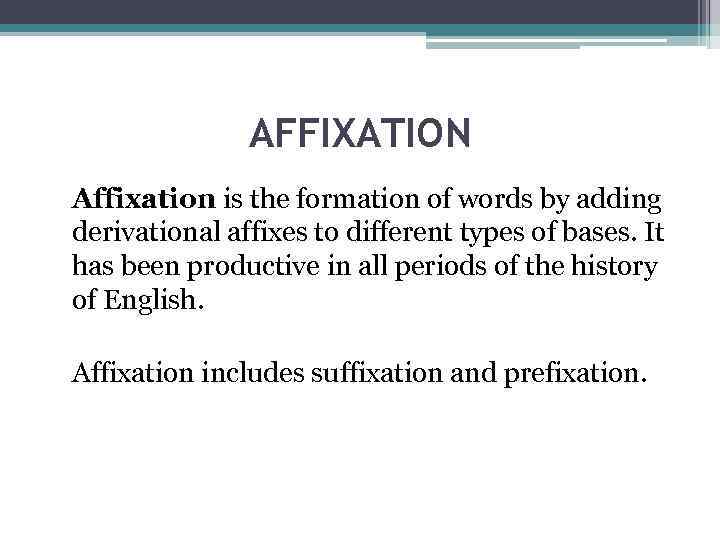

AFFIXATION Affixation is the formation of words by adding derivational affixes to different types of bases. It has been productive in all periods of the history of English. Affixation includes suffixation and prefixation.

Classification of Suffixes 1. Origin: Romanic (e. g. — age, — ment, — tion), Native (e. g. -er, -dom, — ship), Greek (e. g. -ism, -ize), etc. 2. Productivity: productive suffixes (-er, -ing, -ness, ation, -ee, -ism, -ist, -ance, -ry, -or, -ics), nonproductive suffixes (-some, -th, -hood, -ship, -ful, -ly, -en, — ous). 3. Lexico-grammatical character of the base suffixes are usually added to: deverbial suffixes (speaker, reader, agreement, suitable); denominal suffixes (hopeless, hopeful, violinist, tiresome); deadjectival suffixes (widen, quickly, reddish, loneliness).

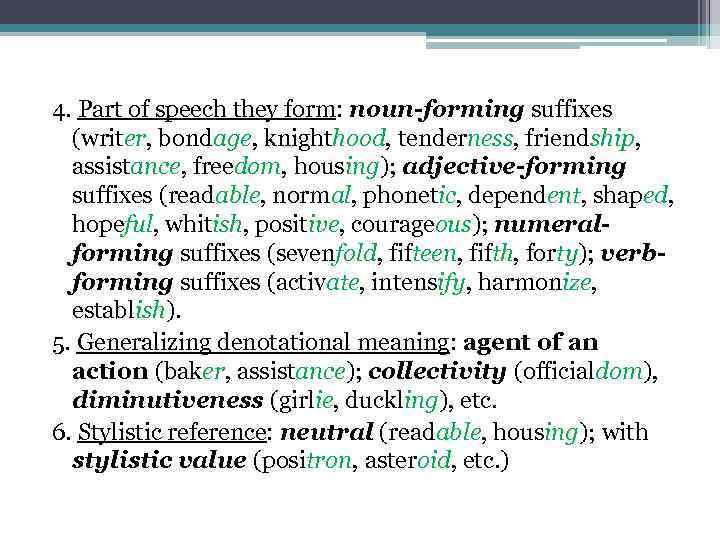

4. Part of speech they form: noun-forming suffixes (writer, bondage, knighthood, tenderness, friendship, assistance, freedom, housing); adjective-forming suffixes (readable, normal, phonetic, dependent, shaped, hopeful, whitish, positive, courageous); numeralforming suffixes (sevenfold, fifteen, fifth, forty); verbforming suffixes (activate, intensify, harmonize, establish). 5. Generalizing denotational meaning: agent of an action (baker, assistance); collectivity (officialdom), diminutiveness (girlie, duckling), etc. 6. Stylistic reference: neutral (readable, housing); with stylistic value (positron, asteroid, etc. )

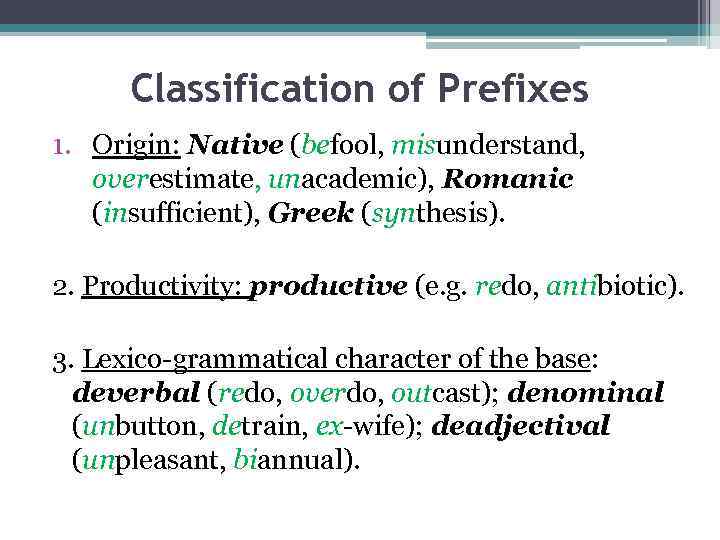

Classification of Prefixes 1. Origin: Native (befool, misunderstand, overestimate, unacademic), Romanic (insufficient), Greek (synthesis). 2. Productivity: productive (e. g. redo, antibiotic). 3. Lexico-grammatical character of the base: deverbal (redo, overdo, outcast); denominal (unbutton, detrain, ex-wife); deadjectival (unpleasant, biannual).

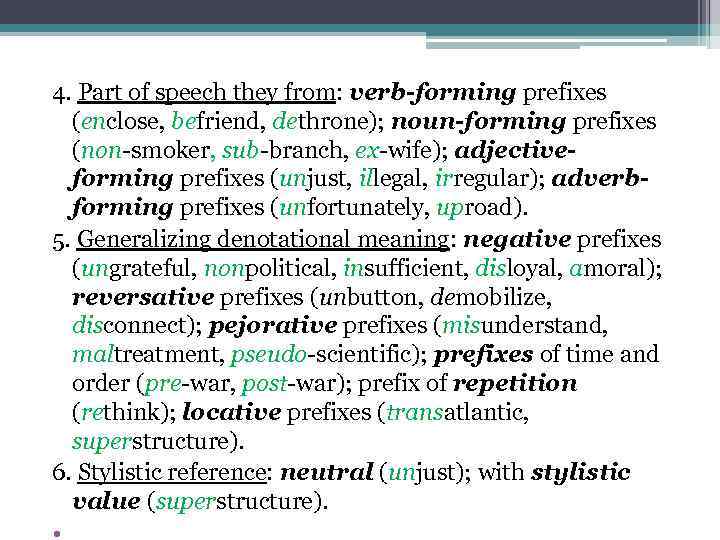

4. Part of speech they from: verb-forming prefixes (enclose, befriend, dethrone); noun-forming prefixes (non-smoker, sub-branch, ex-wife); adjectiveforming prefixes (unjust, illegal, irregular); adverbforming prefixes (unfortunately, uproad). 5. Generalizing denotational meaning: negative prefixes (ungrateful, nonpolitical, insufficient, disloyal, amoral); reversative prefixes (unbutton, demobilize, disconnect); pejorative prefixes (misunderstand, maltreatment, pseudo-scientific); prefixes of time and order (pre-war, post-war); prefix of repetition (rethink); locative prefixes (transatlantic, superstructure). 6. Stylistic reference: neutral (unjust); with stylistic value (superstructure).

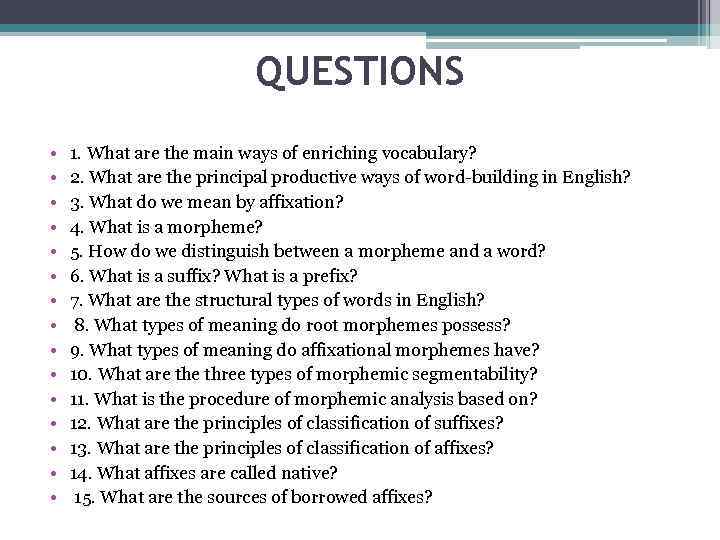

QUESTIONS • • • • 1. What are the main ways of enriching vocabulary? 2. What are the principal productive ways of word-building in English? 3. What do we mean by affixation? 4. What is a morpheme? 5. How do we distinguish between a morpheme and a word? 6. What is a suffix? What is a prefix? 7. What are the structural types of words in English? 8. What types of meaning do root morphemes possess? 9. What types of meaning do affixational morphemes have? 10. What are three types of morphemic segmentability? 11. What is the procedure of morphemic analysis based on? 12. What are the principles of classification of suffixes? 13. What are the principles of classification of affixes? 14. What affixes are called native? 15. What are the sources of borrowed affixes?

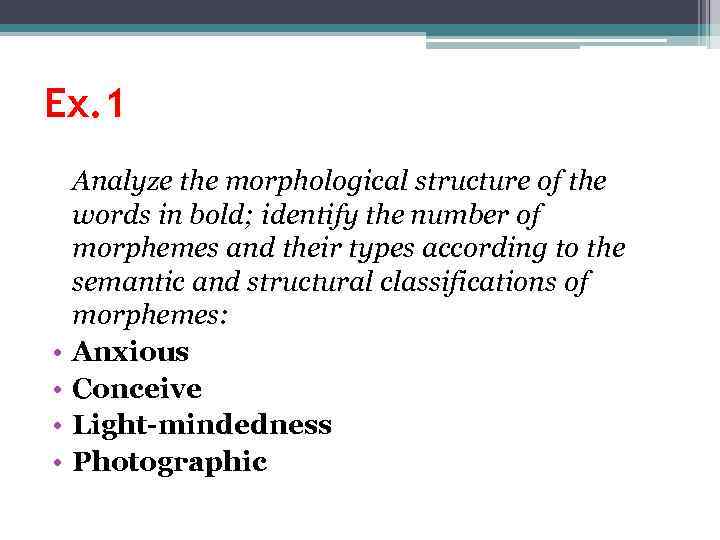

Ex. 1 • • Analyze the morphological structure of the words in bold; identify the number of morphemes and their types according to the semantic and structural classifications of morphemes: Anxious Conceive Light-mindedness Photographic

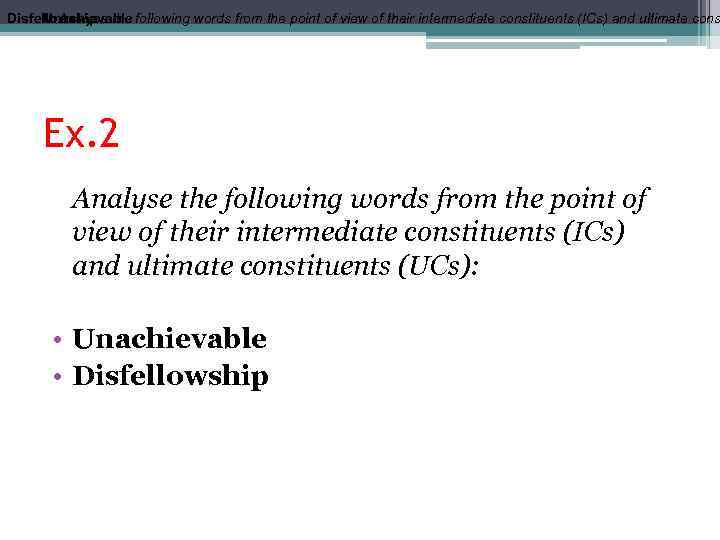

Disfellowship the following words from the point of view of their intermediate constituents (ICs) and ultimate cons Unachievable II. Analyse Ex. 2 Analyse the following words from the point of view of their intermediate constituents (ICs) and ultimate constituents (UCs): • Unachievable • Disfellowship

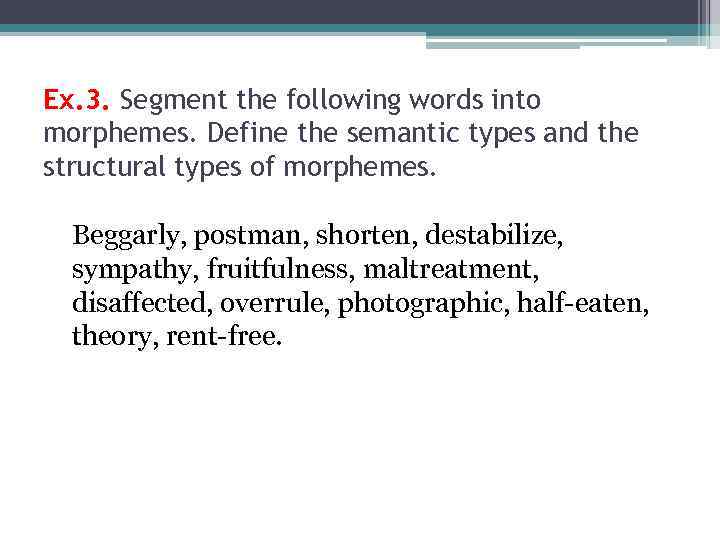

Ex. 3. Segment the following words into morphemes. Define the semantic types and the structural types of morphemes. Beggarly, postman, shorten, destabilize, sympathy, fruitfulness, maltreatment, disaffected, overrule, photographic, half-eaten, theory, rent-free.

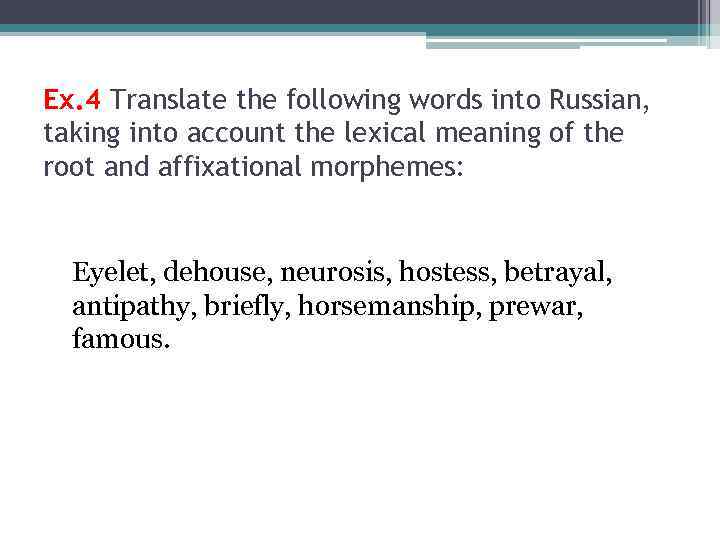

Ex. 4 Translate the following words into Russian, taking into account the lexical meaning of the root and affixational morphemes: Eyelet, dehouse, neurosis, hostess, betrayal, antipathy, briefly, horsemanship, prewar, famous.

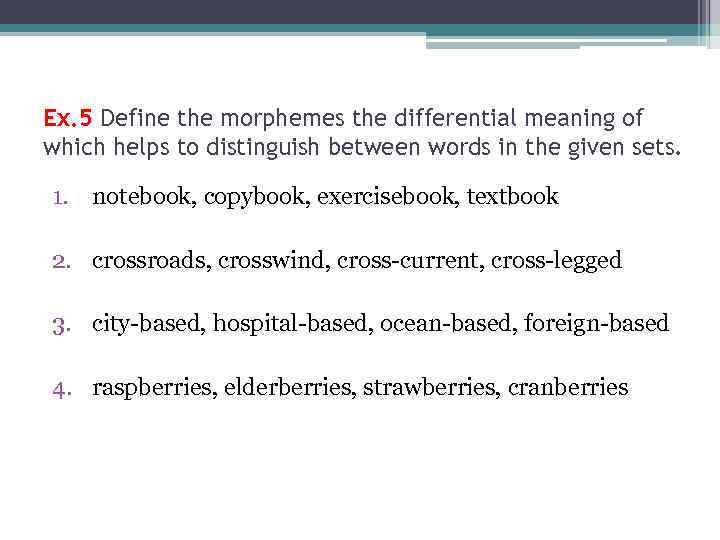

Ex. 5 Define the morphemes the differential meaning of which helps to distinguish between words in the given sets. 1. notebook, copybook, exercisebook, textbook 2. crossroads, crosswind, cross-current, cross-legged 3. city-based, hospital-based, ocean-based, foreign-based 4. raspberries, elderberries, strawberries, cranberries

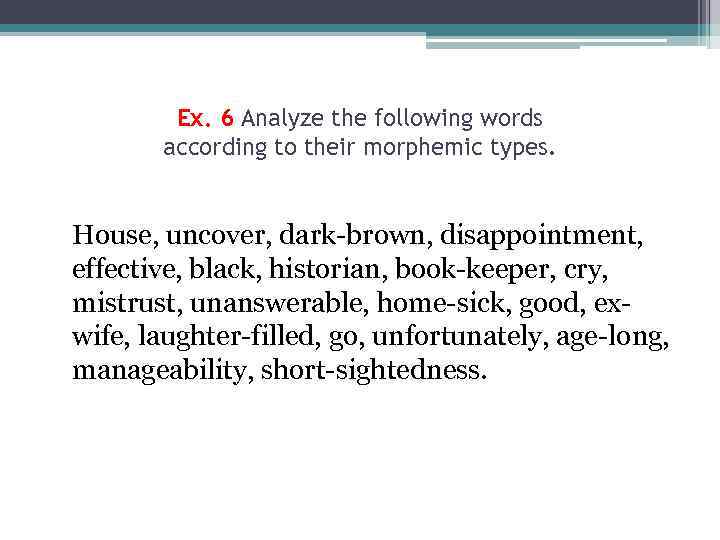

Ex. 6 Analyze the following words according to their morphemic types. House, uncover, dark-brown, disappointment, effective, black, historian, book-keeper, cry, mistrust, unanswerable, home-sick, good, exwife, laughter-filled, go, unfortunately, age-long, manageability, short-sightedness.

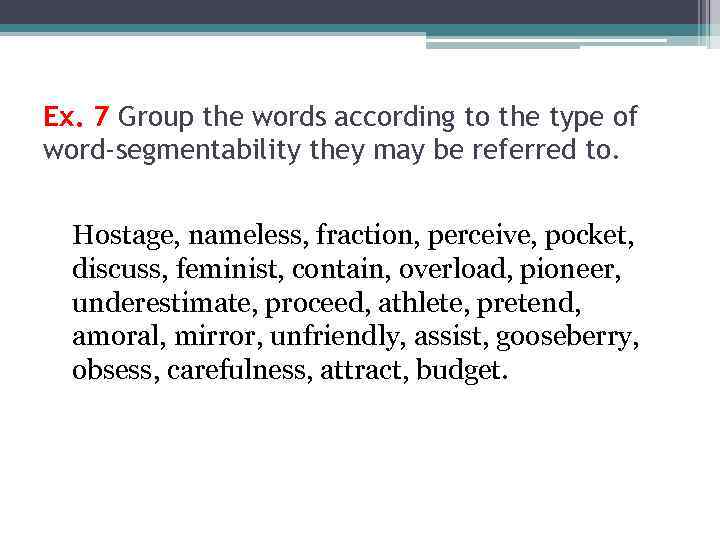

Ex. 7 Group the words according to the type of word-segmentability they may be referred to. Hostage, nameless, fraction, perceive, pocket, discuss, feminist, contain, overload, pioneer, underestimate, proceed, athlete, pretend, amoral, mirror, unfriendly, assist, gooseberry, obsess, carefulness, attract, budget.

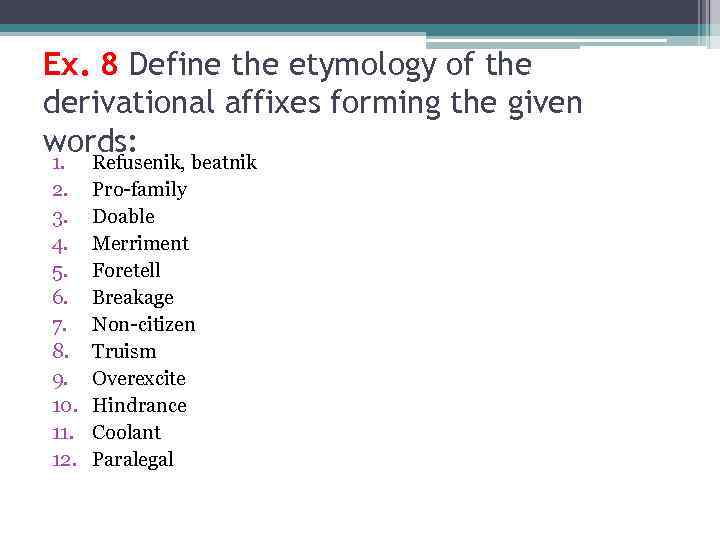

Ex. 8 Define the etymology of the derivational affixes forming the given words: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Refusenik, beatnik Pro-family Doable Merriment Foretell Breakage Non-citizen Truism Overexcite Hindrance Coolant Paralegal

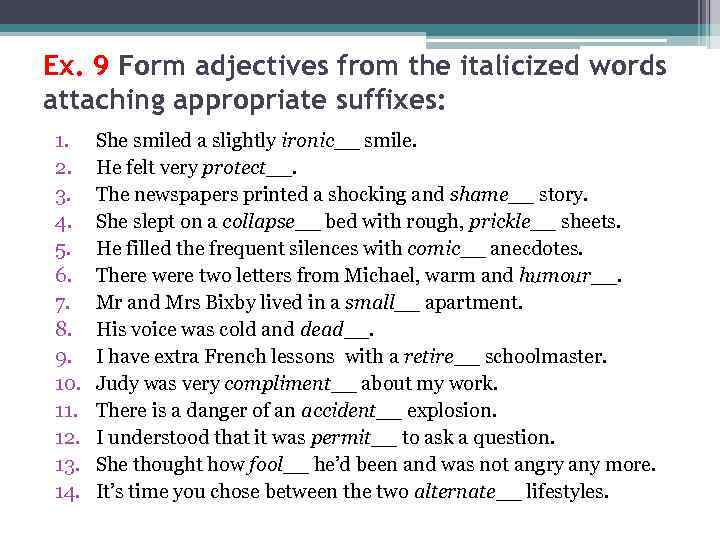

Ex. 9 Form adjectives from the italicized words attaching appropriate suffixes: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. She smiled a slightly ironic__ smile. He felt very protect__. The newspapers printed a shocking and shame__ story. She slept on a collapse__ bed with rough, prickle__ sheets. He filled the frequent silences with comic__ anecdotes. There were two letters from Michael, warm and humour__. Mr and Mrs Bixby lived in a small__ apartment. His voice was cold and dead__. I have extra French lessons with a retire__ schoolmaster. Judy was very compliment__ about my work. There is a danger of an accident__ explosion. I understood that it was permit__ to ask a question. She thought how fool__ he’d been and was not angry any more. It’s time you chose between the two alternate__ lifestyles.

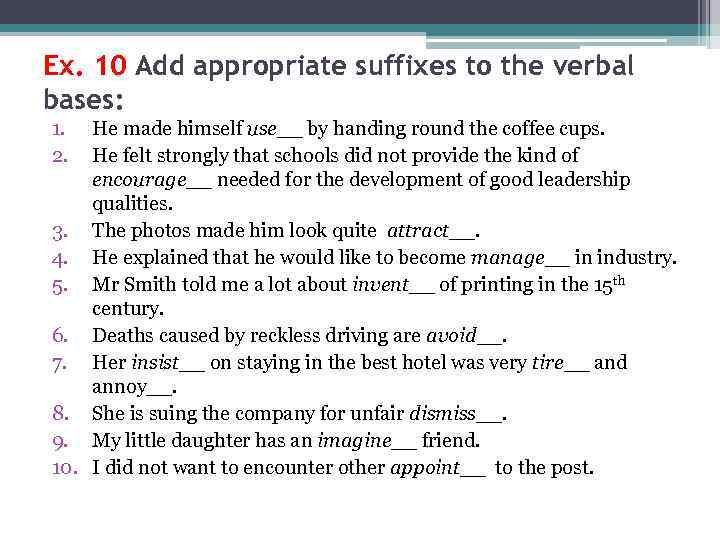

Ex. 10 Add appropriate suffixes to the verbal bases: 1. 2. He made himself use__ by handing round the coffee cups. He felt strongly that schools did not provide the kind of encourage__ needed for the development of good leadership qualities. 3. The photos made him look quite attract__. 4. He explained that he would like to become manage__ in industry. 5. Mr Smith told me a lot about invent__ of printing in the 15 th century. 6. Deaths caused by reckless driving are avoid__. 7. Her insist__ on staying in the best hotel was very tire__ and annoy__. 8. She is suing the company for unfair dismiss__. 9. My little daughter has an imagine__ friend. 10. I did not want to encounter other appoint__ to the post.

Ответы на госы по лексикологии

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 1

1. Lexicology, its aims and significance

Lexicology is a branch of linguistics which deals with a systematic description and study of the vocabulary of the language as regards its origin, development, meaning and current use. The term is composed of 2 words of Greek origin: lexis + logos. A word about words, or the science of a word. It also concerns with morphemes, which make up words and the study of a word implies reference to variable and fixed groups because words are components of such groups. Semantic properties of such words define general rules of their joining together. The general study of the vocabulary irrespective of the specific features of a particular language is known as general lexicology. Therefore, English lexicology is called special lexicology because English lexicology represents the study into the peculiarities of the present-day English vocabulary.

Lexicology is inseparable from: phonetics, grammar, and linguostylistics b-cause phonetics also investigates vocabulary units but from the point of view of their sounds. Grammar- grammatical peculiarities and grammatical relations between words. Linguostylistics studies the nature, functioning and structure of stylistic devices and the styles of a language.

Language is a means of communication. Thus, the social essence is inherent in the language itself. The branch of linguistics which deals with relations between the language functions on the one hand and the facts of social life on the other hand is termed sociolinguistics.

Modern English lexicology investigates the problems of word structure and word formation; it also investigates the word structure of English, the classification of vocabulary units, replenishment3 of the vocabulary; the relations between different lexical layers4 of the English vocabulary and some other. Lexicology came into being to meet the demands of different branches of applied linguistic! Namely, lexicography — a science and art of compiling dictionaries. It is also important for foreign language teaching and literary criticism.

2. Referential approach to meaning

SEMASIOLOGY

There are different approaches to meaning and types of meaning

Meaning is the object of semasiological study -> semasiology is a branch of lexicology which is concerned with the study of the semantic structure of vocabulary units. The study of meaning is the basis of all linguistic investigations.

Russian linguists have also pointed to the complexity of the phenomenon of meaning (Потебня, Щерба, Смирницкий, Уфимцева и др.)

There are 3 main types of definition of meaning:

(a) Analytical or referential definition

(b) Functional or contextual approach

(c) Operational or information-oriented definition of meaning

REFERENTIAL APPROACH

Within the referential approach linguists attempt at establishing interdependence between words and objects of phenomena they denote. The idea is illustrated by the so-called basic triangle:

Concept

Sound – form_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Referent

[kæt] (concrete object)

The diagram illustrates the correlation between the sound form of a word, the concrete object it denotes and the underlying concept. The dotted line suggests that there is no immediate relation between sound form and referent + we can say that its connection is conventional (human cognition).

However the diagram fails to show what meaning really is. The concept, the referent, or the relationship between the main and the concept.

The merits: it links the notion of meaning to the process of namegiving to objects, process of phenomena. The drawbacks: it cannot be applied to sentences and additional meanings that arise in the conversation. It fails to account for polysemy and synonymy and it operates with subjective and intangible mental process as neither reference nor concept belong to linguistic data.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 2

1. Functional approach to meaning

SEMASIOLOGY

There are different approaches to meaning and types of meaning

Meaning is the object of semasiological study -> semasiology is a branch of lexicology which is concerned with the study of the semantic structure of vocabulary units. The study of meaning is the basis of all linguistic investigations.

Russian linguists have also pointed to the complexity of the phenomenon of meaning (Потебня, Щерба, Смирницкий, Уфимцева и др.)

There are 3 main types of definition of meaning:

(a) Analytical or referential definition

(b) Functional or contextual approach

(c) Operational or information-oriented definition of meaning

FUNCTIONAL (CONTEXTUAL) APPROACH

The supporters of this approach define meaning as the use of word in a language. They believe that meaning should be studied through contexts. If the distribution (position of a linguistic unit to other linguictic units) of two words is different we can conclude that heir meanings are different too (Ex. He looked at me in surprise; He’s been looking for him for a half an hour.)

However, it is hardly possible to collect all contexts for reliable conclusion. In practice a scholar is guided by his experience and intuition. On the whole, this approach may be called complimentary to the referential definition and is applied mainly in structural linguistics.

2. Classification of morphemes

A morpheme is the smallest indivisible two-facet language unit which implies an association of a certain meaning with a certain sound form. Unlike words, morphemes cannot function independently (they occur in speech only as parts of words).

Classification of Morphemes

Within the English word stock maybe distinguished morphologically segment-able and non-segment-able words (soundless, rewrite – segmentable; book, car — non-segmentable).

Morphemic segmentability may be of three types:

a) Complete segmentability is characteristic of words with transparent morphemic structure (morphemes can be easily isolated, e.g. heratless).

b) Conditional segmentability characterizes words segmentation of which into constituent morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons (retain, detain, contain). Pseudo-morphemes

c) Defective morphemic segmentability is the property of words whose component morphemes seldom or never occur in other words. Such morphemes are called unique morphemes (cran – cranberry (клюква), let- hamlet (деревушка)).

· Semantically morphemes may be classified into: 1) root morphemes – radicals (remake, glassful, disorder — make, glass, order- are understood as the lexical centres of the words) and 2) non-root morphemes – include inflectional (carry only grammatical meaning and relevant only for the formation of word-forms) and affixational morphemes (relevant for building different types of stems).

· Structurally, morphemes fall into: free morphemes (coincides with the stem or a word-form. E.g. friend- of thenoun friendship is qualified as a free morpheme), bound morphemes (occurs only as a constituent part of a word. Affixes are bound for they always make part of a word. E.g. the suffixes –ness, -ship, -ize in the words darkness, friendship, to activize; the prefixes im-, dis-, de- in the words impolite, to disregard, to demobilize) and semi-free or semi-bound morphemes (can function both as affixes and free morphemes. E.g. well and half on the one hand coincide with the stem – to sleep well, half an hour, and on the other in the words – well-known, half-done).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 3

1. Types of meaning

The word «meaning» is not homogeneous. Its components are described as «types of meaning». The two main types of meaning are grammatical and lexical meaning.

The grammatical meaning is the component of meaning, recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of words (e.g. reads, draws, writes – 3d person, singular; books, boys – plurality; boy’s, father’s – possessive case).

The lexical meaning is the meaning proper to the linguistic unit in all its forms and distribution (e.g. boy, boys, boy’s, boys’ – grammatical meaning and case are different but in all of them we find the semantic component «male child»).

Both grammatical meaning and lexical meaning make up the word meaning and neither of them can exist without the other.

There’s also the 3d type: lexico-grammatical (part of speech) meaning. Third type of meaning is called lexico-grammatical meaning (or part-of-speech meaning). It is a common denominator of all the meanings of words belonging to a lexical-grammatical class (nouns, verbs, adjectives etc. – all nouns have common meaning oа thingness, while all verbs express process or state).

Denotational meaning – component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. The second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component – the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word.

2. Syntactic structure and pattern of word-groups

The meaning of word groups can be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the component words but it is not a mere additive result of all the lexical meanings of components. The meaning of the word group itself dominates the meaning of the component members (Ex. an easy rule, an easy person).

The meaning of the word group is further complicated by the pattern of arrangement of its constituents (Ex. school grammar- grammar school).

That’s why we should bear in mind the existence of lexical and structural components of meaning in word groups, since these components are independent and inseparable. The syntactic structure (formula) implies the description of the order and arrangement of member-words as parts of speech («to write novels» — verb + noun; «clever at mathematics»- adjective + preposition + noun).

As a rule, the difference in the meaning of the head word is presupposed by the difference in the pattern of the word group in which the word is used (to get + noun = to get letters / presents; to get + to + noun = to get to town). If there are different patterns, there are different meanings. BUT: identity of patterns doesn’t imply identity of meanings.

Semanticallv. English word groups are analyzed into motivated word groups and non-motivated word groups. Word groups are lexically motivated if their meanings are deducible from the meanings of components. The degree of motivation may be different.

A blind man — completely motivated

A blind print — the degree of motivation is lower

A blind alley (= the deadlock) — the degree of motivation is still less.

Non-motivated word-groups are usually described as phraseological units.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 4

1. Classification of phraseological units

The term «phraseological unit» was introduced by Soviet linguist (Виноградов) and it’s generally accepted in this country. It is aimed at avoiding ambiguity with other terms, which are generated by different approaches, are partially motivated and non-motivated.

The first classification of phraseological units was advanced for the Russian language by a famous Russian linguist Виноградов. According to the degree of idiomaticity phraseological units can be classified into three big groups: phraseological collocations (сочетания), phraseological unities (единства) and phraseological fusions (сращения).

Phraseological collocations are not motivated but contain one component used in its direct meaning, while the other is used metaphorically (e.g. to break the news, to attain success).

Phraseological unities are completely motivated as their meaning is transparent though it is transferred (e.g. to shoe one’s teeth, the last drop, to bend the knee).

Phraseological fusions are completely non-motivated and stable (e.g. a mare’s nest (путаница, неразбериха; nonsense), tit-for-tat – revenge, white elephant – expensive but useless).

But this classification doesn’t take into account the structural characteristic, besides it is rather subjective.

Prof. Смирнитский treats phraseological units as word’s equivalents and groups them into: (a) one-summit units => they have one meaningful component (to be tied, to make out); (b) multi-summit units => have two or more meaningful components (black art, to fish in troubled waters).

Within each of these groups he classifies phraseological units according to the part of speech of the summit constituent. He also distinguishes proper phraseological units or units with non-figurative meaning and idioms that have transferred meaning based on metaphor (e.g. to fall in love; to wash one’s dirty linen in public).

This classification was criticized as inconsistent, because it contradicts the principle of idiomaticity advanced by the linguist himself. The inclusion of phrasal verbs into phraseology wasn’t supported by any convincing argument.

Prof. Амазова worked out the so-called contextual approach. She believes that if 3 word groups make up a variable context. Phraseological units make up the so-called fixed context and they are subdivided into phrases and idioms.

2. Procedure of morphemic analysis

Morphemic analysis deals with segmentable words. Its procedure flows to split a word into its constituent morphemes, and helps to determine their number and type. It’s called the method of immediate and ultimate constituents. This method is based on the binary principle which allows to break morphemic structure of a word into 2 components at each stage. The analysis is completed when we arrive at constituents unable of any further division. E.g. Louis Bloomfield — classical example:

ungentlemanly

I. un-(IC/UC) +gentlemanly (IC) (uncertain, unhappy)

II. gentleman (IC) + -ly (IC/UC) (happily, certainly)

III. gentle (IC) +man (IC/UC) (sportsman, seaman)

IV. gent (IC/UC) + le (IC/UC) (gentile, genteel)

The aim of the analysis is to define the number and the type of morphemes.

As we break the word we obtain at any level only 2 immediate constituents, one of which is the stem of the given word. The morphemic analysis may be based either on the identification of affixational morphemes within a set of words, or root morphemes.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 5

1. Causes, nature and results of semantic change

The set of meanings the word possesses isn’t fixed. If approached diachronically, the polysemy reflects sources and types of semantic changes. The causes of such changes may be either extra-linguistic including historical and social factors, foreign influence and the need for a new name, or linguistic, which are due to the associations that words acquire in speech (e.g. «atom» has a Greek origin, now is used in physics; «to engage» in the meaning «to invite» appeared in English due to French influence = > to engage for a dance). To unleash war – развязать войну – but originally – to unleash dogs)

The nature of semantic changes may be of two main types: 1) Similarity of meaning (metaphor). It implies a hidden comparison (bitter style – likeness of meaning or metonymy). It is the process of associating two references, one of which is part of the other, or is closely connected with it. In other words, it is nearest in type, space or function (e.g. «table» in the meaning of “food” or “furniture” [metonymy]).

The semantic change may bring about following results: 1. narrowing of meaning (e.g. “success” – was used to denote any kind of result, but today it is onle “good results”);

2. widening of meaning (e.g. “ready” in Old English was derived from “ridan” which went to “ride” – ready for a ride; but today there are lots of meanings),

3. degeneration of meaning — acquisition by a word of some derogatory or negative emotive charge (e.g. «villain» was borrowed from French “farm servant”; but today it means “a wicked person”).

4. amelioration of meaning — acquisition by a word of some positive emotive charge (e.g. «kwen» in Old English meant «a woman» but in Modern English it is «queen»).

It is obvious that 3, 4 result illustrate the change in both denotational and connotational meaning. 1, 2 change in the denotational.

The change of meaning can also be expressed through a change in the number and arrangement of word meanings without any other changes in the semantic structure of a word.

2. Productivity of word-formation means

According to Смирницкий, word-formation is the system of derivative types of words and the process of creating new words from the material available in the language. Words are formed after certain structural and semantic patterns. The main two types of word-formation are: word-derivation and word-composition (compounding).

The degree of productivity of word-formation and factors that favor it make an important aspect of synchronic description of every derivational pattern within the two types of word-formation. The two general restrictions imposed on the derivational patterns are: 1. the part of speech in which the pattern functions; 2. the meaning which is attached to it.

Three degrees of productivity are distinguished for derivational patterns and individual derivational affixes: highly productive, productive or semi-productive and non-productive.

Productivity of derivational patterns and affixes shouldn’t be identified with frequency of occurrence in speech (e.g.-er — worker, -ful – beautiful are active suffixes because they are very frequently used. But if -er is productive, it is actively used to form new words, while -ful is non-productive since no new words are built).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 6

1. Morphological, phonetical and semantic motivation

A new meaning of a word is always motivated. Motivation — is the connection between the form of the word (i.e. its phonetic, morphological composition and structural pattern) and its meaning. Therefore a word may be motivated phonetically, morphologically and semantically.

Phonetically motivated words are not numerous. They imitate the sounds (e.g. crash, buzz, ring). Or sometimes they imitate quick movement (e.g. rain, swing).

Morphological motivation is expressed through the relationship of morphemes => all one-morpheme words aren’t motivated. The words like «matter» are called non-motivated or idiomatic while the words like «cranberry» are partially motivated because structurally they are transparent, but «cran» is devoid of lexical meaning; «berry» has its lexical meaning.

Semantic motivation is the relationship between the direct meaning of the word and other co-existing meanings or lexico-semantic variants within the semantic structure of a polysemantic word (e.g. «root»— «roots of evil» — motivated by its direct meaning, «the fruits of peace» — is the result).

Motivation is a historical category and it may fade or completely disappear in the course of years.

2. Classification of compounds

The meaning of a compound word is made up of two components: structural meaning of a compound and lexical meaning of its constituents.

Compound words can be classified according to different principles.

1. According to the relations between the ICs compound words fall into two classes: 1) coordinative compounds and 2) subordinative compounds.

In coordinative compounds the two ICs are semantically equally important. The coordinative compounds fall into three groups:

a) reduplicative compounds which are made up by the repetition of the same base, e.g. pooh-pooh (пренебрегать), fifty-fifty;

b) compounds formed by joining the phonically variated rhythmic twin forms, e.g. chit-chat, zig-zag (with the same initial consonants but different vowels); walkie-talkie (рация), clap-trap (чепуха) (with different initial consonants but the same vowels);

c) additive compounds which are built on stems of the independently functioning words of the same part of speech, e.g. actor-manager, queen-bee.

In subordinative compounds the components are neither structurally nor semantically equal in importance but are based on the domination of the head-member which is, as a rule, the second IС, e.g. stone-deaf, age-long. The second IС preconditions the part-of-speech meaning of the whole compound.

2. According to the part of speech compounds represent they fall into:

1) compound nouns, e.g. sunbeam, maidservant;

2) compound adjectives, e.g. heart-free, far-reaching;

3) compound pronouns, e.g. somebody, nothing;

4) compound adverbs, e.g. nowhere, inside;

5) compound verbs, e.g. to offset, to bypass, to mass-produce.

From the diachronic point of view many compound verbs of the present-day language are treated not as compound verbs proper but as polymorphic verbs of secondary derivation. They are termed pseudo-compounds and are represented by two groups: a) verbs formed by means of conversion from the stems of compound nouns, e.g. to spotlight (from spotlight); b) verbs formed by back-derivation from the stems of compound nouns, e.g. to babysit (from baby-sitter).

However synchronically compound verbs correspond to the definition of a compound as a word consisting of two free stems and functioning in the sentence as a separate lexical unit. Thus, it seems logical to consider such words as compounds by right of their structure.

3. According to the means of composition compound words are classified into:

1) compounds composed without connecting elements, e.g. heartache, dog-house;

2)compounds composed with the help of a vowel or a consonant as a linking element, e.g. handicraft, speedometer, statesman;

3) compounds composed with the help of linking elements represented by preposition or conjunction stems, e.g. son-in-law, pepper-and-salt.

4. According to the type of bases that form compounds the following classes can be singled out:

1) compounds proper that are formed by joining together bases built on the stems or on the word-forms with or without a linking element, e.g. door-step, street-fighting;

2) derivational compounds that are formed by joining affixes to the bases built on the word-groups or by converting the bases built on the word-groups into other parts of speech, e.g. long-legged —> (long legs) + -ed; a turnkey —> (to turn key) + conversion. Thus, derivational compounds fall into two groups: a) derivational compounds mainly formed with the help of the suffixes -ed and -er applied to bases built, as a rule, on attributive phrases, e.g. narrow-minded, doll-faced, lefthander; b) derivational compounds formed by conversion applied to bases built, as a rule, on three types of phrases — verbal-adverbial phrases (a breakdown), verbal-nominal phrases (a kill-joy) and attributive phrases (a sweet-tooth).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 7

1. Diachronic and synchronic approaches to polysemy

Diachronically, polysemy is understood as the growth and development of the semantic structure of the word. Historically we differentiate between the primary and secondary meanings of words.

The relation between these meanings isn’t only the one of order of appearance but it is also the relation of dependence = > we can say that secondary meaning is always the derived meaning (e.g. dog – 1. animal, 2. despicable person)

Synchronically it is possible to distinguish between major meaning of the word and its minor meanings. However it is often hard to grade individual meaning of the word in order of their comparative value (e.g. to get the letter — получить письмо; to get to London — прибыть в Лондон — minor).

The only more or less objective criterion in this case is the frequency of occurrence in speech (e.g. table – 1. furniture, 2. food). The semantic structure is never static and the primary meaning of a word may become synchronically one of the minor meanings and vice versa. Stylistic factors should always be taken into consideration

Polysemy of words: «yellow»- sensational (Am., sl.)

The meaning which has the highest frequency is the one representative of the whole semantic structure of the word. The Russian equivalent of «a table» which first comes to your mind and when you hear this word is ‘cтол» in the meaning «a piece of furniture». And words that correspond in their major meanings in two different languages are referred to as correlated words though their semantic structures may be different.

Primary meaning — historically first.

Major meaning — the most frequently used meaning of the word synchronically.

2. Typical semantic relations between words in conversion pairs

We can single out the following typical semantic relation in conversion pairs:

1) Verbs converted from nouns (denominal verbs):

a) Actions characteristic of the subject (e.g. ape – to ape – imitate in a foolish way);

b) Instrumental use of the object (e.g. whip — to whip – strike with a whip);

c) Acquisition or addition of the objects (e.g. fish — to fish — to catch fish);

d) Deprivation of the object (e.g. dust — to dust – remove dust).

2) Nouns converted from verbs (deverbal nouns):

a) Instance of the action (e.g. to move — a move = change of position);

b) Agent of an action (e.g. to cheat — a cheat – a person who cheats);

c) Place of the action (e.g. to walk-a walk – a place for walking);

d) Object or result of the action (e.g. to find- a find – something found).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 8

1. Classification of homonyms

Homonyms are words that are identical in their sound-form or spelling but different in meaning and distribution.

1) Homonyms proper are words similar in their sound-form and graphic but different in meaning (e.g. «a ball»- a round object for playing; «a ball»- a meeting for dances).

2) Homophones are words similar in their sound-form but different in spelling and meaning (e.g. «peace» — «piece», «sight»- «site»).

3) Homographs are words which have similar spelling but different sound-form and meaning (e.g. «a row» [rau]- «a quarrel»; «a row» [rəu] — «a number of persons or things in a more or less straight line»)

There is another classification by Смирницкий. According to the type of meaning in which homonyms differ, homonyms proper can be classified into:

I. Lexical homonyms — different in lexical meaning (e.g. «ball»);

II. Lexical-grammatical homonyms which differ in lexical-grammatical meanings (e.g. «a seal» — тюлень, «to seal» — запечатывать).

III. Grammatical homonyms which differ in grammatical meaning only (e.g. «used» — Past Indefinite, «used»- Past Participle; «pupils»- the meaning of plurality, «pupil’s»- the meaning of possessive case).

All cases of homonymy may be subdivided into full and partial homonymy. If words are identical in all their forms, they are full homonyms (e.g. «ball»-«ball»). But: «a seal» — «to seal» have only two homonymous forms, hence, they are partial homonyms.

2. Classification of prefixes

Prefixation is the formation of words with the help of prefixes. There are about 51 prefixes in the system of modern English word-formation.

1. According to the type they are distinguished into: a) prefixes that are correlated with independent words (un-, dis-), and b) prefixes that are correlated with functional words (e.g. out, over. under).

There are about 25 convertive prefixes which can transfer words to a different part of speech (E.g. embronze59).

Prefixes may be classified on different principles. Diachronically they may be divided into native and foreign origin, synchronically:

1. According to the class they preferably form: verbs (im, un), adjectives (un-, in-, il-, ir-) and nouns (non-, sub-, ex-).

2. According to the lexical-grammatical type of the base they are added to:

a). Deverbal — rewrite, overdo;

b). Denominal — unbutton, detrain, ex-president,

c). Deadjectival — uneasy, biannual.

It is of interest to note that the most productive prefixal pattern for adjectives is the one made up of the prefix un- and the base built either on adjectival stems or present and past participle, e.g. unknown, unsmiling, unseen etc.

3. According to their semantic structure prefixes may fall into monosemantic and polysemantic.

4. According to the generic-denotational meaning they are divided into different groups:

a). Negative prefixes: un-, dis-, non-, in-, a- (e.g. unemployment, non-scientific, incorrect, disloyal, amoral, asymmetry).

b). Reversative or privative60 prefixes: un-, de-, dis- (e.g. untie, unleash, decentralize, disconnect).

c). Pejorative prefixes: mis-, mal-, pseudo- (e.g. miscalculate, misinform, maltreat, pseudo-classicism).

d). Prefixes of time and order: fore-, pre-, post-, ex- (e.g. foretell, pre-war, post-war, ex-president).

e). Prefix of repetition re- (e.g. rebuild, rewrite).

f). Locative prefixes: super-, sub-, inter-, trans- (e.g. superstructure, subway, inter-continental, transatlantic).

5. According to their stylistic reference:

a). Neutral: un-, out-, over-, re-, under- (e.g. outnumber, unknown, unnatural, oversee, underestimate).

b). Stylistically marked: pseudo-, super-, ultra-, uni-, bi- (e.g. pseudo-classical, superstructure, ultra-violet, unilateral) they are bookish.

6. According to the degree of productivity: a). highly productive, b). productive, c). non-productive.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 9

.

1. Types of linguistic contexts

The term “context” denotes the minimal stretch of speech determining each individual meaning of the word. Contexts may be of two types: linguistic (verbal) and extra-linguistic (non-verbal).

Linguistic contexts may be subdivided into lexical and grammatical.

In lexical contexts of primary importance are the groups of lexical items combined with polysemantic word under consideration (e.g. adj. “heavy” is used with the words “load, table” means ‘of great weight’ ; but with natural phenomena “rain, storm, snow, wind’ it is understood as ‘abundant, striking, falling with force’; and if with “industry, artillery, arms” – ‘the larger kind of smth’). The meaning at the level of lexical contexts is sometimes described as meaning by collocation.

In grammatical meaning it is the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context that serves to determine various individual meanings of a polysemantic word (e.g. the meaning of the verb “to make” – ‘to force, to induce’ is found only in the syntactic structure “to make + prn. +verb”; another meaning ‘to become’ – “to make + adj. + noun” (to make a good teacher, wife)). Such meanings are sometimes described as grammatically bound meanings.

2. Classification of suffixes

Suffixation is the formation of words with the help of suffixes. Suffixes usually modify the lexical meaning of the base and transfer words to a different part of speech. There are suffixes, however, which do not shift words from one part of speech into another; a suffix of this kind usually transfers a word into a different semantic group, e.g. a concrete noun becomes an abstract one, as in the case with child — childhood, friend- friendship etc. Suffixes may be classified:

1. According to the part of speech they form

a). Noun-suffixes: -er, -dom, -ness, -ation (e.g. teacher, freedom, brightness, justification).

b). Adjective-suffixes: -able, -less, -ful, -ic, -ous (e.g. agreeable, careless, doubtful, poetic, courageous).

c). Verb-suffixes: -en, -fy, -ize (e.g. darken, satisfy, harmonize).

d). Adverb-suffixes: -ly, -ward (e.g. quickly, eastward).

2. According to the lexico-grammatical character of the base the suffixes are usually added to:

a). Deverbal suffixes (those added to the verbal base):-er, -ing, -ment, -able (speaker, reading, agreement, suitable).

b). Denominal suffixes (those added to the noun base):-less, -ish, -ful, -ist, -some (handless, childish, mouthful, troublesome).

c). Deadjectival suffixes (those affixed to the adjective base):-en, -ly, -ish, -ness (blacken, slowly, reddish, brightness).

3. According to the meaning expressed by suffixes:

a). The agent of an action: -er, -ant (e.g. baker, dancer, defendant), b). Appurtenance64: -an, -ian, -ese (e.g. Arabian, Elizabethan, Russian, Chinese, Japanese).

c). Collectivity: -age, -dom, -ery (-ry) (e.g. freightage, officialdom, peasantry).

d). Diminutiveness: -ie, -let, -ling (birdie, girlie, cloudlet, booklet, darling).

4. According to the degree of productivity:

a). Highly productive

b). Productive

c). Non-productive

5. According to the stylistic value:

a). Stylistically neutral:-able, -er, -ing.

b). Stylistically marked:-oid, -i/form, -aceous, -tron (e.g. asteroid)

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 10

1. Semantic equivalence and synonymy

The traditional initial category of words that can be singled out on the basis of proximity is synonyms. The degree of proximity varies from semantic equivalence to partial semantic similarity. The classes of full synonyms are very rare and limited mainly two terms.

The greatest degree of similarity is found in those words that are identical in their denotational aspect of meaning and differ in connotational one (e.g. father- dad; imitate – monkey). Such synonyms are called stylistic synonyms. However, in the major of cases the change in the connotational aspect of meaning affects in some way the denotational aspect. These synonyms of the kind are called ideographic synonyms (e.g. clever – bright, smell – odor). Differ in their denotational aspect ideographic synonyms (kill-murder, power – strength, etc.) – these synonyms are most common.

It is obvious that synonyms cannot be completely interchangeable in all contexts. Synonyms are words different in their sound-form but similar in their denotational aspect of meaning and interchangeable at least in some contexts.

Each synonymic group comprises a dominant element. This synonymic dominant is general term which has no additional connotation (e.g. famous, celebrated, distinguished; leave, depart, quit, retire, clear out).

Syntactic dominants have high frequency of usage, vast combinability and lack connotation.

2. Derivational types of words

The basic units of the derivative structure of words are: derivational basis, derivational affixes, and derivational patterns.

The relations between words with a common root but of different derivative structure are known as derivative relations.

The derivational base is the part of the word which establishes connections with the lexical unit that motivates the derivative and defines its lexical meaning. It’s to this part of the word (derivational base) that the rule of word formation is applied. Structurally, derivational bases fall into 3 classes: 1. Bases that coincide with morphological stems (beautiful, beautifully); 2. Bases that coincide with word-forms (unknown- limited mainly to verbs); 3. Bases that coincide with word groups. They are mainly active in the class of adjectives and nouns (blue-eyed, easy-going).

According to their derivational structure words fall into: simplexes (simple, non-derived words) and complexes (derivatives). Complexes are grouped into: derivatives and compounds. Derivatives fall into: affixational (suffixal and affixal) types and conversions. Complexes constitute the largest class of words. Both morphemic and derivational structure of words is subject to various changes in the course of time.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 11

1. Semantic contrasts and antonymy

The semantic relations of opposition are the basis for grouping antonyms. The term «antonym» is of Greek origin and means “opposite name”. It is used to describe words different in some form and characterised by different types of semantic contrast of denotational meaning and interchangeability at least in some contexts.

Structurally, all antonyms can be subdivided into absolute (having different roots) and derivational (of the same root), (e.g. «right»- «wrong»; «to arrive»- «to leave» are absolute antonyms; but «to fit» — «to unfit» are derivational).

Semantically, all antonyms can be divided in at least 3 groups:

a) Contradictories. They express contradictory notions which are mutually opposed and deny each other. Their relations can be described by the formula «A versus NOT A»: alive vs. dead (not alive); patient vs. impatient (not patient). Contradictories may be polar or relative (to hate- to love [not to love doesn’t mean «hate»]).

b) Contraries are also mutually opposed, but they admit some possibility between themselves because they are gradable (e.g. cold – hot, warm; hot – cold, cool). This group also includes words opposed by the presence of such components of meaning as SEX and AGE (man -woman; man — boy etc.).

c) Incompatibles. The relations between them are not of contradiction but of exclusion. They exclude possibilities of other words from the same semantic set (e.g. «red»- doesn’t mean that it is opposed to white it means all other colors; the same is true to such words as «morning», «day», «night» etc.).

There is another type of opposition which is formed with reversive antonyms. They imply the denotation of the same referent, but viewed from different points (e.g. to buy – to sell, to give – to receive, to cause – to suffer)

A polysemantic word may have as many antonyms as it has meanings. But not all words and meanings have antonyms!!! (e.g. «a table»- it’s difficult to find an antonym, «a book»).

Relations of antonymy are limited to a certain context + they serve to differentiate meanings of a polysemantic word (e.g. slice of bread — «thick» vs. «thin» BUT: person — «fat» vs. «thin»).

2. Types of word segmentability

Within the English word stock maybe distinguished morphologically segment-able and non-segmentable words (soundless, rewrite — segmentable; book, car — non-segmentable).

Morphemic segmentability may be of three types: 1. complete, 2. conditional, 3. defective.

A). Complete segmentability is characteristic of words with transparent morphemic structure. Their morphemes can be easily isolated which are called morphemes proper or full morphemes (e.g. senseless, endless, useless). The transparent morphemic structure is conditioned by the fact that their constituent morphemes recur with the same meaning in a number of other words.

B). Conditional segmentability characterizes words segmentation of which into constituent morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons (e.g. retain, detain, contain). The sound clusters «re-, de-, con-» seem to be easily isolated since they recur in other words but they have nothing in common with the morphemes «re, de-, con-» which are found in the words «rewrite», «decode», «condensation». The sound-clusters «re-, de-, con-» can possess neither lexical meaning nor part of speech meaning, but they have differential and distributional meaning. The morphemes of the kind are called pseudo-morphemes (quasi morphemes).

C). Defective morphemic segmentability is the property of words whose component morphemes seldom or never recur in other words. Such morphemes are called unique morphemes. A unique morpheme can be isolated and displays a more or less clear meaning which is upheld by the denotational meaning of the other morpheme of the word (cranberry, strawberry, hamlet).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 12

1. The main features of A.V.Koonin’s approach to phraseology

Phraseology is regarded as a self-contained branch of linguistics and not as a part of lexicology.

His classification is based on the combined structural-semantic principle and also considers the level of stability of phraseological units.

Кунин subdivides set-expressions into: phraseological units or idioms(e.g. red tape, mare’s nest, etc.), semi-idioms and phraseomatic units(e.g. win a victory, launch a campaign, etc.).

Phraseological units are structurally separable language units with completely or partially transferred meanings (e.g. to kill two birds with one stone, to be in a brown stubby – to be in low spirits). Semi-idioms have both literal and transferred meanings. The first meaning is usually terminological or professional and the second one is transferred (e.g. to lay down one’s arms). Phraseomatic units have literal or phraseomatically bound meanings (e.g. to pay attention to smth; safe and sound).

Кунин assumes that all types of set expressions are characterized by the following aspects of stability: stability of usage (not created in speech and are reproduced ready-made); lexical stability (components are irreplaceable (e.g. red tape, mare’s nest) or partly irreplaceable within the limits of lexical meaning, (e.g. to dance to smb tune/pipe; a skeleton in the cupboard/closet; to be in deep water/waters)); semantic complexity (despite all occasional changes the meaning is preserved); syntactic fixity.

Idioms and semi-idioms are much more complex in structure than phraseological units. They have a broad stylistic range and they admit of more complex occasional changes.

An integral part of this approach is a method of phraseological identification which helps to single out set expressions in Modern English.

2. Types and ways of forming words

According to Смирницкий word-formation is a system of derivative types of words and the process of creating new words from the material available in the language after certain structural and semantic patterns. The main two types are: word-derivation and word-composition (compounding).

The basic ways of forming words in word-derivation are affixation and conversion (the formation of a new word by bringing a stem of this word into a different formal paradigm, e.g. a fall from to fall).

There exist other types: semantic word-building (homonymy, polysemy), sound and stress interchange (e.g. blood – bleed; increase), acronymy (e.g. NATO), blending (e.g. smog = smoke + fog) and shortening of words (e.g. lab, maths). But they are different in principle from derivation and compound because they show the result but not the process.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 13

1. Origin of derivational affixes

From the point of view of their origin, derivational affixes are subdivided into native (e.g suf.- nas, ish, dom; pref.- be, mis, un) and foreign (e.g. suf.- ation, ment, able; pref.- dis, ex, re).

Many original affixes historically were independent words, such as dom, hood and ship. Borrowed words brought with them their derivatives, formed after word-building patterns of their languages. And in this way many suffixes and prefixes of foreign origin have become the integral part of existing word-formation (e.g. suf.- age; pref.- dis, re, non). The adoption of foreign words resulted into appearance of hybrid words in English vocabulary. Sometimes a foring stem is combined with a native suffix (e.g. colourless) and vise versa (e.g. joyous).

Reinterpretation of verbs gave rise to suffix-formation source language (e.g. “scape” – seascape, moonscape – came from landscape. And it is not a suffix.).

2. Correlation types of compounds

Motivation and regularity of semantic and structural correlation with free word-groups are the basic factors favouring a high degree of productivity of composition and may be used to set rules guiding spontaneous, analogic formation of new compound words.

The description of compound words through the correlation with variable word-groups makes it possible to classify them into four major classes: 1) adjectival-nominal, 2) verbal-nominal, 3) nominal and 4) verbal-adverbial.

I. Adjectival-nominal comprise for subgroups of compound adjectives:

1) the polysemantic n+a pattern that gives rise to two types:

a) Compound adjectives based on semantic relations of resemblance: snow-white, skin-deep, age-long, etc. Comparative type (as…as).

b) Compound adjectives based on a variety of adverbial relations: colour-blind, road-weary, care-free, etc.

2) the monosemantic pattern n+venbased mainly on the instrumental, locative and temporal relations, e.g. state-owned, home-made. The type is highly productive. Correlative relations are established with word-groups of the Ven+ with/by + N type.

3) the monosemantic num + npattern which gives rise to a small and peculiar group of adjectives, which are used only attributively, e.g. (a) two-day (beard), (a) seven-day (week), etc. The quantative type of relations.

4) a highly productive monosemantic pattern of derivational compound adjectives based on semantic relations of possession conveyed by the suffix -ed. The basic variant is [(a+n)+ -ed], e.g. long-legged. The pattern has two more variants: [(num + n) + -ed), l(n+n)+ -ed],e.g. one-sided, bell-shaped, doll-faced. The type correlates accordingly with phrases with (having) + A+N, with (having) + Num + N, with + N + N or with + N + of + N.

The three other types are classed as compound nouns. All the three types are productive.

II. Verbal-nominal compounds may be described through one derivational structure n+nv, i.e. a combination of a noun-base (in most cases simple) with a deverbal, suffixal noun-base. All the patterns correlate in the final analysis with V+N and V+prp+N type which depends on the lexical nature of the verb:

1) [n+(v+-er)],e.g. bottle-opener, stage-manager, peace-fighter. The pattern is monosemantic and is based on agentive relations that can be interpreted ‘one/that/who does smth’.

2) [n+(v+-ing)],e.g. stage-managing, rocket-flying. The pattern is monosemantic and may be interpreted as ‘the act of doing smth’.

3) [n+(v+-tion/ment)],e.g. office-management, price-reduction.

4) [n+(v + conversion)],e.g. wage-cut, dog-bite, hand-shake, the pattern is based on semantic relations of result, instance, agent, etc.

III. Nominal compounds are all nouns with the most polysemantic and highly-productive derivational pattern n+n; both bases are generally simple stems, e.g. windmill, horse-race, pencil-case. The pattern conveys a variety of semantic relations; the most frequent are the relations of purpose and location. The pattern correlates with nominal word-groups of the N+prp+N type.

IV. Verb-adverb compounds are all derivational nouns, highly productive and built with the help of conversion according to the pattern [(v + adv) + conversion].The pattern correlates with free phrases V + Adv and with all phrasal verbs of different degree of stability. The pattern is polysemantic and reflects the manifold semantic relations of result.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 14

1. Hyponymic structures and lexico-semantic groups

The grouping out of English word stock based on the principle of proximity, may be graphically presented by means of “concentric circles”.

lexico-semantic groups

lexical sets

synonyms

semantic field

The relations between layers are that of inclusion.

The most general term – hyperonym, more special – hyponym (member of the group).

The meaning of the word “plant” includes the idea conveyed by “flower”, which in its turn include the notion of any particular flower. Flower – hyperonim to… and plant – hyponym to…

Hyponymic relations are always hierarchic. If we imply substitution rules we shall see the hyponyms may be replaced be hyperonims but not vice versa (e.g. I bought roses yesterday. “flower” – the sentence won’t change its meaning).

Words describing different sides of one and the same general notion are united in a lexico-semantic group if: a) the underlying notion is not too generalized and all-embracing, like the notions of “time”, “life”, “process”; b) the reference to the underlying is not just an implication in the meaning of lexical unit but forms an essential part in its semantics.

Thus, it is possible to single out the lexico-semantic group of names of “colours” (e.g. pink, red, black, green, white); lexico-semantic group of verbs denoting “physical movement” (e.g. to go, to turn, to run) or “destruction” (e.g. to ruin, to destroy, to explode, to kill).

2. Causes and ways of borrowing

The great influx of borrowings from Latin, English and Scandinavian can be accounted by a number of historical causes. Due to the great influence of the Roman civilisation Latin was for a long time used in England as the language of learning and religion. Old Norse was the language of the conquerors who were on the same level of social and cultural development and who merged rather easily with the local population in the 9th, 10th and the first half of the 11th century. French (Norman dialect) was the language of the other conquerors who brought with them a lot of new notions of a higher social system (developed feudalism), it was the language of upper classes, of official documents and school instruction from the middle of the 11th century to the end of the 14th century.

In the study of the borrowed element in English the main emphasis is as a rule placed on the Middle English period. Borrowings of later periods became the object of investigation only in recent years. These investigations have shown that the flow of borrowings has been steady and uninterrupted. The greatest number has come from French. They refer to various fields of social-political, scientific and cultural life. A large portion of borrowings is scientific and technical terms.

The number and character of borrowed words tell us of the relations between the peoples, the level of their culture, etc.

Some borrowings, however, cannot be explained by the direct influence of certain historical conditions, they do not come along with any new objects or ideas. Such were for instance the words air, place, brave, gay borrowed from French.

Also we can say that the closer the languages, the deeper is the influence. Thus under the influence of the Scandinavian languages, which were closely related to Old English, some classes of words were borrowed that could not have been adopted from non-related or distantly related languages (the pronouns they, their, them); a number of Scandinavian borrowings were felt as derived from native words (they were of the same root and the connection between them was easily seen), e.g. drop(AS.) — drip (Scand.), true (AS.)-tryst (Scand.); the Scandinavian influence even accelerated to a certain degree the development of the grammatical structure of English.

Borrowings enter the language in two ways: through oral speech (early periods of history, usually short and they undergo changes) and through written speech (recent times, preserve spelling and peculiarities of the sound form).

Borrowings may be direct or indirect (e.g., through Latin, French).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 15

1. Types of English dictionaries

English dictionaries may all be roughly divided into two groups — encyclopaedic and linguistic.

The encyclopaedic dictionaries, (The Encyclopaedia Britannica and The Encyclopedia Americana) are scientific reference books dealing with every branch of knowledge, or with one particular branch, usually in alphabetical order. They give information about the extra-linguistic world; they deal with facts and concepts. Linguistic dictionaries are wоrd-books the subject-matter of which is lexical units and their linguistic properties such as pronunciation, meaning, peculiarities of use, etc.

Linguistic dictionaries may be divided into different categories by different criteria.

1. According to the nature of their word-listwe may speak about general dictionaries (include frequency dictionary, a rhyming dictionary, a Thesaurus) and restricted (belong terminological, phraseological, dialectal word-books, dictionaries of new words, of foreign words, of abbreviations, etc).

2. According to the information they provide all linguistic dictionaries fall into two groups: explanatory and specialized.

Explanatory dictionaries present a wide range of data, especially with regard to the semantic aspect of the vocabulary items entered (e.g. New Oxford Dictionary of English).

Specialized dictionaries deal with lexical units only in relation to some of their characteristics (e.g. etymology, frequency, pronunciation, usage)

3. According to the language of explanations all dictionaries are divided into: monolingual and bilingual.

4. Dictionaries also fall into diachronic and synchronic with regard of time. Diachronic (historical) dictionaries reflect the development of the English vocabulary by recording the history of form and meaning for every word registered (e.g. Oxford English Dictionary). Synchronic (descriptive) dictionaries are concerned with the present-day meaning and usage of words (e.g. Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English).

(Phraseological dictionaries, New Words dictionaries, Dictionaries of slang, Usage dictionaries, Dictionaries of word-frequency, A Reverse dictionary, Pronouncing dictionaries, Etymological dictionaries, Ideographic dictionaries, synonym-books, spelling reference books, hard-words dictionaries, etc.)

2. The role of native and borrowed elements in English

The number of borrowings in Old English was small. In the Middle English period there was an influx of loans. It is often contended that since the Norman Conquest borrowing has been the chief factor in the enrichment of the English vocabulary and as a result there was a sharp decline in the productivity of word-formation. Historical evidence, however, testifies to the fact that throughout its entire history, even in the periods of the mightiest influxes of borrowings, other processes, no less intense, were in operation — word-formation and semantic development, which involved both native and borrowed elements.

If the estimation of the role of borrowings is based on the study of words recorded in the dictionary, it is easy to overestimate the effect of the loan words, as the number of native words is extremely small compared with the number of borrowings recorded. The only true way to estimate the relation of the native to the borrowed element is to consider the two as actually used in speech. If one counts every word used, including repetitions, in some reading matter, the proportion of native to borrowed words will be quite different. On such a count, every writer uses considerably more native words than borrowings. Shakespeare, for example, has 90%, Milton 81%, Tennyson 88%. It shows how important is the comparatively small nucleus of native words.

Different borrowings are marked by different frequency value. Those well established in the vocabulary may be as frequent in speech as native words, whereas others occur very rarely.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 16

1. The main variants of the English language

In Modern linguistics the distinction is made between Standard English and territorial variants and local dialects of the English language.

Standard English may be defined as that form of English which is current and literary, substantially uniform and recognized as acceptable wherever English is spoken or understood. Most widely accepted and understood either within an English-speaking country or throughout the entire English-speaking world.

Variants of English are regional varieties possessing a literary norm. There are distinguished variants existing on the territory of the United Kingdom (British English, Scottish English and Irish English), and variants existing outside the British Isles (American English, Canadian English, Australian English, New Zealand English, South African English and Indian English). British English is often referred to the Written Standard English and the pronunciation known as Received Pronunciation (RP).

Local dialects are varieties of English peculiar to some districts, used as means of oral communication in small localities; they possess no normalized literary form.

Variants of English in the United Kingdom

Scottish English and Irish English have a special linguistic status as compared with dialects because of the literature composed in them.

Variants of English outside the British Isles

Outside the British Isles there are distinguished the following variants of the English language: American English, Canadian English, Australian English, New Zealand English, South African English, Indian English and some others. Each of these has developed a literature of its own, and is characterized by peculiarities in phonetics, spelling, grammar and vocabulary.

2. Basic problems of dictionary-compiling

Lexicography, the science, of dictionary-compiling, is closely connected with lexicology, both dealing with the same problems — the form, meaning, usage and origin of vocabulary units — and making use of each other’s achievements.

Some basic problems of dictionary-compiling:

1) the selection of lexical units for inclusion,

2) their arrangement,

3) the setting of the entries,

4) the selection and arrangement (grouping) of word-meanings,

5) the definition of meanings,

6) illustrative material,

7) supplementary material.

1) The selection of lexical units for inclusion.

It is necessary to decide: a) what types of lexical units will be chosen for inclusion; b) the number of items; c) what to select and what to leave out in the dictionary; d) which form of the language, spoken or written or both, the dictionary is to reflect; e) whether the dictionary should contain obsolete units, technical terms, dialectisms, colloquialisms, and so forth.

The choice depends upon the type to which the dictionary will belong, the aim the compilers pursue, the prospective user of the dictionary, its size, the linguistic conceptions of the dictionary-makers and some other considerations.

2) Arrangement of entries.

There are two modes of presentation of entries: the alphabetical order and the cluster-type (arranged in nests, based on some principle – words of the same root).

3) The setting of the entries.

Since different types of dictionaries differ in their aim, in the information they provide, in their size, etc., they of necessity differ in the structure and content of the entry.

The most complicated type of entry is that found in general explanatory dictionaries of the synchronic type (the entry usually presents the following data: accepted spelling and pronunciation; grammatical characteristics including the indication of the part of speech of each entry word, whether nouns are countable or uncountable, the transitivity and intransitivity of verbs and irregular grammatical forms; definitions of meanings; modern currency; illustrative examples; derivatives; phraseology; etymology; sometimes also synonyms and antonyms.

4) The selection and arrangement (grouping) of word-meanings.

The number of meanings a word is given and their choice in this or that dictionary depend, mainly, on two factors: 1) on what aim the compilers set themselves and 2) what decisions they make concerning the extent to which obsolete, archaic, dialectal or highly specialised meanings should be recorded, how the problem of polysemy and homonymy is solved, how cases of conversion are treated, how the segmentation of different meanings of a polysemantic word is made, etc.

There are at least three different ways in which the word meanings are arranged: a) in the sequence of their historical development (called historical order), b) in conformity with frequency of use that is with the most common meaning first (empirical or actual order), c) in their logical connection (logical order).

5) The definition of meanings.

Meanings of words may be defined in different ways: 1) by means of linguistic definitions that are only concerned with words as speech material, 2) by means of encyclopaedic definitions that are concerned with things for which the words are names (nouns, proper nouns and terms), 3) be means of synonymous words and expressions (verbs, adjectives), 4) by means of cross-references (derivatives, abbreviations, variant forms). The choice depends on the nature of the word (the part of speech, the aim and size of the dictionary).

6) Illustrative material.

It depends on the type of the dictionary and on the aim the compliers set themselves.

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 17

1. Sources of compounds

The actual process of building compound words may take different forms: 1) Compound words as a rule are built spontaneously according to productive distributional formulas of the given period. Formulas productive at one time may lose their productivity at another period. Thus at one time the process of building verbs by compounding adverbial and verbal stems was productive, and numerous compound verbs like, e.g. outgrow, offset, inlay (adv + v), were formed. The structure ceased to be productive and today practically no verbs are built in this way.

2) Compounds may be the result of a gradual process of semantic isolation and structural fusion of free word-groups. Such compounds as forget-me-not; bull’s-eye—’the centre of a target; a kind of hard, globular candy’; mainland—‘acontinent’ all go back to free phrases which became semantically and structurally isolated in the course of time. The words that once made up these phrases have lost their integrity, within these particular formations, the whole phrase has become isolated in form, «specialized in meaning and thus turned into an inseparable unit—a word having acquired semantic and morphological unity. Most of the syntactic compound nouns of the (a+n) structure, e.g. bluebell, blackboard, mad-doctor, are the result of such semantic and structural isolation of free word-groups; to give but one more example, highway was once actually a high way for it was raised above the surrounding countryside for better drainage and ease of travel. Now we use highway without any idea of the original sense of the first element.

2. Lexical differences of territorial variants of English

All lexical units may be divided into general English (common to all the variants) and locally-marked (specific to present-day usage in one of the variants and not found in the others). Different variants of English use different words for the same objects (BE vs. AE: flat/apartment, underground/subway, pavement/sidewalk, post/mail).

Speaking about lexical differences between the two variants of the English language, the following cases are of importance:

1. Cases where there are no equivalent words in one of the variant! (British English has no equivalent to the American word drive-in (‘a cinema or restaurant that one can visit without leaving one’s car’)).

2. Cases where different words are used for the same denotatum, e.g. sweets (BrE) — candy (AmE); reception clerk (BrE) — desk clerk (AmE).

3. Cases where some words are used in both variants but are much commoner in one of them. For example, shop and store are used in both variants, but the former is frequent in British English and the latter in American English.

4. Cases where one (or more) lexico-semantic variant(s) is (are) specific to either British English or American English (e.g. faculty, denoting ‘all the teachers and other professional workers of a university or college’ is used only in American English; analogous opposition in British English or Standard English — teaching staff).

5. Cases where one and the same word in one of its lexico-semantic variants is used oftener in British English than in American English (brew — ‘a cup of tea’ (BrE), ‘a beer or coffee drink’ (AmE).

Cases where the same words have different semantic structure in British English and American English (homely — ‘home-loving, domesticated, house-proud’ (BrE), ‘unattractive in appearance’ (AmE); politician ‘a person who is professionally involved in politics’, neutral, (BrE), ‘a person who acts in a manipulative and devious way, typically to gain advancement within an organisation’ (AmE).

Besides, British English and American English have their own derivational peculiarities (some of the affixes more frequently used in American English are: -ее (draftee — ‘a young man about to be enlisted’), -ster (roadster — ‘motor-car for long journeys by road’), super- (super-market — ‘a very large shop that sells food and other products for the home’); AmE favours morphologically more complex words (transportation), BrE uses clipped forms (transport); AmE prefers to form words by means of affixes (burglarize), BrE uses back-formation (burgle from burglar).

ЭКЗАМЕНАЦИОННЫЙ БИЛЕТ № 18

1. Methods and procedures of lexicological analysis

The process of scientific investigation may be subdivided into several stages:

1. Observation (statements of fact must be based on observation)

2. Classification (orderly arrangement of the data)

3. Generalization (formulation of a generalization or hypothesis, rule a law)

4. The verifying process. Here, various procedures of linguistic analysis are commonly applied: