I know there are several parts of speech:

- Noun

- Verb

- Pronoun

- Adjective

- Adverb

- Preposition

- Conjunction

- Interjection

There might be others as well. Sometimes a word, depending on how it is used, can fulfill more than one of these classes. For example, the word «run» can be a verb:

I run fast.

or it can be a noun:

Let’s go for a run!

What word, taking into account all its definitions, can fulfill the most word classes?

Daniel

57.1k75 gold badges256 silver badges377 bronze badges

asked Oct 25, 2011 at 16:54

10

Well is an interjection, adjective, adverb, noun, and verb. That’s five.

Business is going well. [adverb]

All is well with us. [adjective]

Well, who would have thought he could do it? [interjection]

The well was drilled fifty meters deep. [noun]

Tears well up in my eyes. [verb]

There’s also round, with five, if you count when it is used to mean around:

Give me a round figure. [adjective]

Shall we play another round of cards? [noun]

He had a look round before he kept going. [adverb]

They walked round the tree. [preposition]

The floor function rounds down. [verb]

answered Oct 25, 2011 at 17:43

DanielDaniel

57.1k75 gold badges256 silver badges377 bronze badges

5

Damn fits five of the categories.

-a verb: Damn you!

-a noun: I don’t give a damn.

-an adjective: The damn rain won’t stop.

-an adverb: That was damn close.

-an interjection: Damn! That was close.

answered Oct 25, 2011 at 17:57

1

The OED has definitions for but as 6 parts of speech: conjunction, preposition, adverb, noun, verb, adjective and pronoun.

- conjunction — «I would go to the store, but it’s raining».

- preposition — «everything but the dog»

- adverb — «Bring but a bottle o’ Primrose wine» (from OED) (synonymous with ‘only’)

- noun (archaic or Scots dialect) — «I found him settled in this but and ben.» (OED) (inside of a house)

- verb — «Nay, but me no buts» (OED)

- adjective — «He conducted me to the but end of the mansion.» (OED) (the very end)

- pronoun — «Not a man but felt the terror in his hair.» (OED) sort of a negative ‘who’

Mitch

70.1k28 gold badges137 silver badges260 bronze badges

answered Oct 25, 2011 at 17:42

Barrie EnglandBarrie England

139k10 gold badges240 silver badges400 bronze badges

13

How about the word down?

- Noun: His pillow is made of down.

- Verb: The quarterback downed the ball.

- Preposition: He lives down the street.

- Adjective: His coat is made of down feathers.

- Adverb: He fell down.

- Interjection: Down, Fido!

MetaEd

28.1k17 gold badges83 silver badges135 bronze badges

answered Jan 26, 2012 at 20:44

JohnJohn

511 silver badge1 bronze badge

1

I assume you’re just asking for amusement — I don’t see a practical application of an answer. Frankly, I think a question like this could quickly get bogged down in questions of definition and application.

Like, a candidate that occurs to me is «and», if I’m allowed to include the use of the word as a boolean operation, as in mathematics and computers:

conjunction (the obvious use): Bob walked AND talked.

adjective: We performed on AND operation on the two variables.

verb: We ANDed the two variables together.

noun: Put an AND in the expression here.

And of course almost any word can be used as an interjection: «AND! AND, you say! I would say BUT!»

answered Oct 25, 2011 at 17:45

JayJay

35.6k3 gold badges57 silver badges105 bronze badges

2

Both «buffalo» and «police» serve as enough different parts of speech to enable us to form entire sentences by simply repeating the word.

Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.

and

Police police police police police police police police.

although these are basically just adjectives, verbs, and nouns.

EDIT:

These two sentences have identical structure (with some Buffalo capitalized because they refer to the city of Buffalo, NY). Below, the bold words are the subject and their action (buffalo from Buffalo, or «Buffalo buffalo»), the italics are another set of buffalo from Buffalo acting on those buffalo, and the plaintext is the buffalo being buffaloed (intimidated) by the original subject.

Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo bufallo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.

Or, more clearly,

Bison from New York, who are intimidated by bison from New York, intimidate bison from New York.

I hope I’ve made it clear.

Note: In the «police» version, the structure is identical, but we are discussing «police police», or police that police other police, policing other police police while being policed by police police.

answered Oct 25, 2011 at 18:22

yoozer8yoozer8

8,7128 gold badges46 silver badges88 bronze badges

4

What part of speech a particular word in a particular sentence is often going to be a matter of dispute. This answer is probably valid according to some.

verb: Don’t her me, I’m a guy.

noun: Is that a him or a her?

pronoun: Say hi to her.

determiner: I see her car.

adjective: We got his and her towels. The his towel is on the rack, and the her towel is in the laundry.

interjection: Her! Her! Stop calling me him.

adverb: I passed her the salt.

answered Jan 27, 2012 at 16:30

msh210msh210

4,2821 gold badge21 silver badges51 bronze badges

7

‘like’ can be up to nine! POS, props to Ron Powell (he only claimed seven…).

Below as taxonomized by Maggie Balistreri: «The Evasion-English Dictionary» (2003) + essay on ‘like’, or Wikipedia on ‘like’. See also ‘whatever’.

Five of these are standard usage…

- Verb ‘I like you’

- Noun ‘We will never see the like of him again’

- Adjective ‘using a like design to the iPhone’

- Preposition ‘He left early like his friend’

- Conjunction ‘Act like it’s fun’

…then there are these four colloquialisms, as taxonomized:

- Adverb ‘They, like, hate you!’

- Interjection ‘I didn’t say anything, like.’ ‘Like, get out of my way, biatch!’

- Quotative ‘I was like, «Who do they think they are?’

- Hedge (if you accept that) ‘I have, like, no money’

Wikipedia: non-traditional usage of the word has been around at least since the 1950s, introduced through beat and jazz culture…. also cites Scooby Doo (started 1969) : Shaggy: «Like, let’s get out of here, Scoob!»

answered May 14, 2012 at 0:50

smcismci

1,98512 silver badges15 bronze badges

1

LOVE is a basic answer, even though I can only put it in 5 categories. They are:

- Noun: Love grows old.

- Verb: She loves him.

- Adjective: The love birds have disappeared.

- Pronoun: Give me the drink,love.

- Interjection: Love! That all you need in life.

answered Jun 28, 2013 at 15:29

Either this belongs in English Language Learners or the answer lies with Frank’s tank, or both.

Frank was a soldier in charge of a very valuable radio set which sadly, he dropped off the back of a truck.

A moment later, a tank came round the corner and squashed the radio flat and what did Frank say, d’you suppose?

Fuck me; the fucking fucker’s fucking well fucked.

In any language, what word is anything remotely like so flexible?

answered Sep 23, 2017 at 1:54

Robbie GoodwinRobbie Goodwin

2,3581 gold badge9 silver badges21 bronze badges

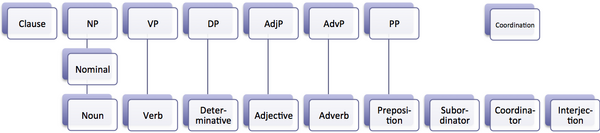

In grammar, a part of speech or part-of-speech (abbreviated as POS or PoS, also known as word class[1] or grammatical category[2]) is a category of words (or, more generally, of lexical items) that have similar grammatical properties. Words that are assigned to the same part of speech generally display similar syntactic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphological behavior in that they undergo inflection for similar properties and even similar semantic behavior. Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

Other terms than part of speech—particularly in modern linguistic classifications, which often make more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word class, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer only to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be function words, such as pronouns. The term form class is also used, although this has various conflicting definitions.[3] Word classes may be classified as open or closed: open classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) acquire new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages have the word classes noun and verb, but beyond these two there are significant variations among different languages.[4] For example:

- Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a class of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages do not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or between adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[4]

History[edit]

The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[5]

India[edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[6]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammar of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to have been written around 2nd century CE,[7] classifies Tamil words as peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[8]

Western tradition[edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, «sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]».[9] Aristotle added another class, «conjunction» [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, but also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[10]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[11]

- ‘Name’ (ónoma) translated as «Noun«: a part of speech inflected for case, signifying a concrete or abstract entity. It includes various species like nouns, adjectives, proper nouns, appellatives, collectives, ordinals, numerals and more.[12]

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without case inflection, but inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activity or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the noun

- Article (árthron): a declinable part of speech, taken to include the definite article, but also the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a part of speech placed before other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a part of speech without inflection, in modification of or in addition to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech binding together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding «article» (since the Latin language, unlike Greek, does not have articles) but adding «interjection».[13][14]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, noun adjective and noun numeral. Later[15] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English word noun came to be applied to substantives only.

Classification[edit]

Works of English grammar generally follow the pattern of the European tradition as described above, except that participles are now usually regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a separate part of speech, and numerals are often conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., «one», and collective numerals, e.g., «dozen»), adjectives (ordinal numerals, e.g., «first», and multiplier numerals, e.g., «single») and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., «once», and distributive numerals, e.g., «singly»). Eight or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- noun

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article* or (more recently) determiner

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

Some traditional classifications consider articles to be adjectives, yielding eight parts of speech rather than nine. And some modern classifications define further classes in addition to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries:

- Noun (names)

- a word or lexical item denoting any abstract (abstract noun: e.g. home) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. house); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified as count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The most common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns make sentences shorter and clearer since they replace nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a noun or pronoun (big, brave). Adjectives make the meaning of another word (noun) more precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of being (be). Without a verb, a group of words cannot be a clause or sentence.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a word that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another word in the sentence.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, but). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or exclamation (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not always listed among the parts of speech. It is considered by some grammarians to be a type of adjective[16] or sometimes the term ‘determiner’ (a broader class) is used.

English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties. In English, most words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that exist are mostly ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal past tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may mark a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may mark a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that ending, while many adjectives do have it (e.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.g. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more than one part of speech. Words like neigh, break, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, even words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, «We must look to the hows and not just the whys.» The process whereby a word comes to be used as a different part of speech is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification[edit]

Linguists recognize that the above list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[17] For example, «adverb» is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have even argued that the most basic of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[18] or not applicable to certain languages.[19][20] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set defined by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that will usually be closed classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Within a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more precise grammatical properties. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

Many modern descriptions of grammar include not only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and so on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes[edit]

Word classes may be either open or closed. An open class is one that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is one to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes normally contain large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open classes found in English and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open class, though less familiar to English speakers,[21][22][b] and are often open to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[24]

The open–closed distinction is related to the distinction between lexical and functional categories, and to that between content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[25] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[26][27][28] are closed classes, usually consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these form a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same ways as other words in its class.[29] A closed class may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen as part of the core language and is not expected to change. In English, for example, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to become accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a need for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies between languages, even assuming that corresponding word classes exist. Most conspicuously, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than a few hundred simple verbs, a great deal of which are archaic. (Some twenty Persian verbs are used as light verbs to form compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[30] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[31] though these are quite large, with about 700 adjectives,[32][33] and verbs have opened slightly in recent years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a sentence, for instance). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru (する, to do) to a noun, as in undō suru (運動する, to (do) exercise), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na (〜な) when an adjectival noun modifies a noun phrase, as in hen-na ojisan (変なおじさん, strange man). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru (〜る) to a noun or using it to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).[34] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was almost entirely borrowed as nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed class include Swahili,[28] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open class and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent example is jibun (自分, self), now used by some young men as a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct class is disputed,[by whom?] however, with some considering it only a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[35]

Some word classes are universally closed, however, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[35]

See also[edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-speech tagging

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yes and no are sometimes classified as interjections.

- ^ Ideophones do not always form a single grammatical word class, and their classification varies between languages, sometimes being split across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word class, based on derivation, but may be considered part of the category of «expressives»,[21] which thus often form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, «[i]n the vast majority of cases, however, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs.»[23]

References[edit]

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2007). «Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. Wiley. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00030.x. ISSN 1749-818X. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Payne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: a guide for field linguists. Cambridge. ISBN 9780511805066.

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). General Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^

Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the world: India’s contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3). - ^ Mahadevan, I. (2014). Early Tamil Epigraphy — From the Earliest Times to the Sixth century C.E., 2nd Edition. p. 271.

- ^

Ilakkuvanar S (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher. - ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (11. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A word is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a complete thought.

The class of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in form is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ The term ‘onoma’ at Dionysius Thrax, Τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), 14. Περὶ ὀνόματος translated by Thomas Davidson, On the noun

- καὶ αὐτὰ εἴδη προσαγορεύεται· κύριον, προσηγορικόν, ἐπίθετον, πρός τι ἔχον, ὡς πρός τι ἔχον, ὁμώνυμον, συνώνυμον, διώνυμον, ἐπώνυμον, ἐθνικόν, ἐρωτηματικόν, ἀόριστον, ἀναφορικὸν ὃ καὶ ὁμοιωματικὸν καὶ δεικτικὸν καὶ ἀνταποδοτικὸν καλεῖται, περιληπτικόν, ἐπιμεριζόμενον, περιεκτικόν, πεποιημένον, γενικόν, ἰδικόν, τακτικόν, ἀριθμητικόν, ἀπολελυμένον, μετουσιαστικόν.

- also called Species: proper, appellative, adjective, relative, quasi-relative, homonym, synonym, pheronym, dionym, eponym, national, interrogative, indefinite, anaphoric (also called assimilative, demonstrative, and retributive), collective, distributive, inclusive, onomatopoetic, general, special, ordinal, numeral, participative, independent.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria reads: «Our own language (Note: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn’t have articles), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must be added to those already mentioned.»]

- ^ «Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I».

- ^ See for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata … (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). «What part of speech is «the»«. Language Log. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

…the school tradition about parts of speech is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). «The Iconicity of the Universal Categories ‘Noun’ and ‘Verbs’«. In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). «Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs». Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, «African ideophones», in Sound Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ «Sample Entry: Function Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics».

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-470-65531-3.

- ^ Dixon, Robert M. W. (1977). «Where Have all the Adjectives Gone?». Studies in Language. 1: 19–80. doi:10.1075/sl.1.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. W. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Language Development. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Class Categories, «p. 54».

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-18). «Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier».

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links[edit]

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

- The parts of speech

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. «Word Classes and Parts of Speech.» In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

A part of speech is a term used in traditional grammar for one of the nine main categories into which words are classified according to their functions in sentences, such as nouns or verbs. Also known as word classes, these are the building blocks of grammar.

Parts of Speech

- Word types can be divided into nine parts of speech:

- nouns

- pronouns

- verbs

- adjectives

- adverbs

- prepositions

- conjunctions

- articles/determiners

- interjections

- Some words can be considered more than one part of speech, depending on context and usage.

- Interjections can form complete sentences on their own.

Every sentence you write or speak in English includes words that fall into some of the nine parts of speech. These include nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections. (Some sources include only eight parts of speech and leave interjections in their own category.)

Learning the names of the parts of speech probably won’t make you witty, healthy, wealthy, or wise. In fact, learning just the names of the parts of speech won’t even make you a better writer. However, you will gain a basic understanding of sentence structure and the English language by familiarizing yourself with these labels.

Open and Closed Word Classes

The parts of speech are commonly divided into open classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) and closed classes (pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles/determiners, and interjections). The idea is that open classes can be altered and added to as language develops and closed classes are pretty much set in stone. For example, new nouns are created every day, but conjunctions never change.

In contemporary linguistics, the label part of speech has generally been discarded in favor of the term word class or syntactic category. These terms make words easier to qualify objectively based on word construction rather than context. Within word classes, there is the lexical or open class and the function or closed class.

Read about each part of speech below and get started practicing identifying each.

Noun

Nouns are a person, place, thing, or idea. They can take on a myriad of roles in a sentence, from the subject of it all to the object of an action. They are capitalized when they’re the official name of something or someone, called proper nouns in these cases. Examples: pirate, Caribbean, ship, freedom, Captain Jack Sparrow.

Pronoun

Pronouns stand in for nouns in a sentence. They are more generic versions of nouns that refer only to people. Examples: I, you, he, she, it, ours, them, who, which, anybody, ourselves.

Verb

Verbs are action words that tell what happens in a sentence. They can also show a sentence subject’s state of being (is, was). Verbs change form based on tense (present, past) and count distinction (singular or plural). Examples: sing, dance, believes, seemed, finish, eat, drink, be, became

Adjective

Adjectives describe nouns and pronouns. They specify which one, how much, what kind, and more. Adjectives allow readers and listeners to use their senses to imagine something more clearly. Examples: hot, lazy, funny, unique, bright, beautiful, poor, smooth.

Adverb

Adverbs describe verbs, adjectives, and even other adverbs. They specify when, where, how, and why something happened and to what extent or how often. Examples: softly, lazily, often, only, hopefully, softly, sometimes.

Preposition

Prepositions show spacial, temporal, and role relations between a noun or pronoun and the other words in a sentence. They come at the start of a prepositional phrase, which contains a preposition and its object. Examples: up, over, against, by, for, into, close to, out of, apart from.

Conjunction

Conjunctions join words, phrases, and clauses in a sentence. There are coordinating, subordinating, and correlative conjunctions. Examples: and, but, or, so, yet, with.

Articles and Determiners

Articles and determiners function like adjectives by modifying nouns, but they are different than adjectives in that they are necessary for a sentence to have proper syntax. Articles and determiners specify and identify nouns, and there are indefinite and definite articles. Examples: articles: a, an, the; determiners: these, that, those, enough, much, few, which, what.

Some traditional grammars have treated articles as a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars, however, more often include articles in the category of determiners, which identify or quantify a noun. Even though they modify nouns like adjectives, articles are different in that they are essential to the proper syntax of a sentence, just as determiners are necessary to convey the meaning of a sentence, while adjectives are optional.

Interjection

Interjections are expressions that can stand on their own or be contained within sentences. These words and phrases often carry strong emotions and convey reactions. Examples: ah, whoops, ouch, yabba dabba do!

How to Determine the Part of Speech

Only interjections (Hooray!) have a habit of standing alone; every other part of speech must be contained within a sentence and some are even required in sentences (nouns and verbs). Other parts of speech come in many varieties and may appear just about anywhere in a sentence.

To know for sure what part of speech a word falls into, look not only at the word itself but also at its meaning, position, and use in a sentence.

For example, in the first sentence below, work functions as a noun; in the second sentence, a verb; and in the third sentence, an adjective:

- Bosco showed up for work two hours late.

- The noun work is the thing Bosco shows up for.

- He will have to work until midnight.

- The verb work is the action he must perform.

- His work permit expires next month.

- The attributive noun [or converted adjective] work modifies the noun permit.

Learning the names and uses of the basic parts of speech is just one way to understand how sentences are constructed.

Dissecting Basic Sentences

To form a basic complete sentence, you only need two elements: a noun (or pronoun standing in for a noun) and a verb. The noun acts as a subject and the verb, by telling what action the subject is taking, acts as the predicate.

- Birds fly.

In the short sentence above, birds is the noun and fly is the verb. The sentence makes sense and gets the point across.

You can have a sentence with just one word without breaking any sentence formation rules. The short sentence below is complete because it’s a command to an understood «you».

- Go!

Here, the pronoun, standing in for a noun, is implied and acts as the subject. The sentence is really saying, «(You) go!»

Constructing More Complex Sentences

Use more parts of speech to add additional information about what’s happening in a sentence to make it more complex. Take the first sentence from above, for example, and incorporate more information about how and why birds fly.

- Birds fly when migrating before winter.

Birds and fly remain the noun and the verb, but now there is more description.

When is an adverb that modifies the verb fly. The word before is a little tricky because it can be either a conjunction, preposition, or adverb depending on the context. In this case, it’s a preposition because it’s followed by a noun. This preposition begins an adverbial phrase of time (before winter) that answers the question of when the birds migrate. Before is not a conjunction because it does not connect two clauses.

V.V. Vinogradov

|

Notional |

Functional |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Henry Sweet

|

Declinable |

Indeclinable |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Otto Jespersen

-

Substantives

(including proper names) -

Adjectives

-

Pronouns

(including numerals and pronominal adverbs) -

Verbs

-

Particles

-

adverbs,

-

prepositions

-

conjunctions

-

Interjections j.C. Nesfield

-

-

A Noun

is a word used for naming some person or thing. -

A

Pronoun

is a word used instead of a noun or noun-equivalent. -

An

Adjective

is a word used to qualify a noun. -

A Verb

is

a word used for saying something about some person or thing. -

A

Preposition

is a word placed before a noun or noun-equivalent to show in

what relation the person or thing denoted by the noun stands to

something else. -

A

Conjunction

is a word used to join words or phrases together, or one clause to

another clause. -

An

Adverb

is a word used to qualify any part of speech except a noun or

pronoun. -

An

Interjection

is a word or sound thrown into a sentence to express some feeling

of the mind.

-

Noun, its categories.

The noun is

the central lexical unit of language. It is the main nominative unit

of speech. As any other part of speech, the noun can be characterised

by three criteria: semantic (the meaning), morphological (the form

and grammatical categories) and syntactical (functions,

distribution).

Semantic

features of the noun. The noun possesses the grammatical meaning of

thingness, substantiality. According to different principles of

classification, nouns fall into several subclasses:

According

to the type of nomination they may be proper and common;

According

to the form of existence they may be animate and inanimate. Animate

nouns in their turn fall into human and non-human.

According

to their quantitative structure nouns can be countable and

uncountable.

This set of

subclasses cannot be put together into one table because of the

different principles of classification.

Morphological

features of the noun. In accordance with the morphological structure

of the stems all nouns can be classified into: simple, derived (stem

+ affix, affix + stem — thingness); compound (stem+ stem —

armchair ) and composite (the Hague). The noun has morphological

categories of number and case. Some scholars admit the existence of

the category of gender.

Syntactic

features of the noun. The noun can be used in the sentence in all

syntactic functions but predicate. Speaking about noun combinability,

we can say that it can go into right-hand and left-hand connections

with practically all parts of speech. That is why practically all

parts of speech but the verb can act as noun determiners. However,

the most common noun determiners are considered to be articles,

pronouns, numerals, adjectives and nouns themselves in the common and

genitive case.

According

to their morphological composition nouns can be divided into simple,

derived, and compound.

Simple

nouns consist of only one root-morpheme.

Derived

nouns (derivatives) are composed of one root-morpheme and one or more

derivational morphemes (prefixes or suffixes).

Compound

nouns consist of at least two stems. The meaning of a compound is not

a mere sum of its elements. The main types of compound nouns are:

Noun stem +

noun stem: e.g. airmail

Adjective

stem + noun stem: e.g. blackbird

Verb stem +

noun stem: e.g. pickpocket

Gerund +

noun stem: e.g. dancing-hall

Noun stem +

prepositions + noun stem: e.g. mother-in-law

Substantivised

phrases: e.g. forget-me-not

Nouns fall

under two classes: (A) proper nouns; (B) common nouns.

1 The name

proper is from Lat. proprius ‘one’s own’. Hence a proper name

means one’s own individual name, as distinct from a common name,

that can be given to a class of individuals. The name common is from

Lat. communis and means that which is shared by several things or

individuals possessing some common characteristic.

A. Proper

nouns are individual names given to separate persons or things. As

regards their meaning proper nouns may be personal names (Mary,

Peter, Shakespeare), geographical names (Moscow, London, the

Caucasus), the names of the months and of the days of the week

(February, Monday), names of ships, hotels, clubs etc.

A large

number of nouns now proper were originally common nouns (Brown,

Smith, Mason).

Proper

nouns may change their meaning and become common nouns:

George went

over to the table and took a sandwich and a glass of

champagne.

(Aldington)

В. Common

nouns are names that can be applied to any individual of a class of

persons or things (e. g. man, dog, book), collections of similar

individuals or things regarded as a single unit (e. g. peasantry,

family), materials (e. g. snow, iron, cotton) or abstract notions (e.

g. kindness, development).

Thus there

are different groups of common nouns: class nouns, collective nouns,

nouns of material and abstract nouns.

Nouns may

also be classified from another point of view: nouns denoting things

(the word thing is used in a broad sense) that can be counted are

called countable nouns; nouns denoting things that cannot be counted

are called uncountable nouns.

1. Class

nouns denote persons or things belonging to a class. They are

countables and have two numbers: sinuglar and plural. They are

generally used with an article.1

1 On the

use of articles with class nouns see Chapter II, § 2, 3.

“Well,

sir,” said Mrs. Parker, “I wasn’t in the shop above a great

deal.”

(Mansfield)

He goes to

the part of the town where the shops are. (Lessing)

2.

Collective nouns denote a number or collection of similar individuals

or things regarded as a single unit.

Collective

nouns fall under the following groups:

(a) nouns

used only in the singular and denoting a number of things collected

together and regarded as a single object: foliage, machinery.

It was not

restful, that green foliage. (London)

Machinery

new to the industry in Australia was introduced for preparing

land.

(Agricultural Gazette)

(b) nouns

which are singular in form though plural in meaning: police, poultry,

cattle, people, gentry. They are usually called nouns of multitude.

When the subject of the sentence is a noun of multitude the verb used

as predicate is in the plural:

I had no

idea the police were so devilishly prudent. (Shaw)

Unless

cattle are in good condition in calving, milk production will never

reach a

high level. (Agricultural Gazette)

The weather

was warm and the people were sitting at their doors. (Dickens)

(c) nouns

that may be both singular and plural: family, crowd, fleet, nation.

We can think of a number of crowds, fleets or different nations as

well as of a single crowd, fleet, etc.

A small

crowd is lined up to see the guests arrive. (Shaw)

Accordingly

they were soon afoot, and walking in the direction of the scene of

action,

towards which crowds of people were already pouring from a variety

of

quarters. (Dickens)

3. Nouns of

material denote material: iron, gold, paper, tea, water. They are

uncountables and are generally used without any article.1

1 On the

use of articles with nouns of material see Chapter II, § 5, 6, 7.

There was a

scent of honey from the lime-trees in flower. (Galsworthy)

There was

coffee still in the urn. (Wells)

Nouns of

material are used in the plural to denote different sorts of a given

material.

…that his

senior counted upon him in this enterprise, and had consigned a

quantity of select wines to him… (Thackeray)

Nouns of

material may turn into class nouns (thus becoming countables) when

they come to express an individual object of definite shape.

C o m p a r

e:

To the left

were clean panes of glass. (Ch. Bronte)

“He came

in here,” said the waiter looking at the light through the tumbler,

“ordered

a glass of this ale.” (Dickens)

But the

person in the glass made a face at her, and Miss Moss went out.

(Mansfield)

4. Abstract

nouns denote some quality, state, action or idea: kindness, sadness,

fight. They are usually uncountables, though some of them may be

countables (e. g. idea, hour).2

2 On the

use of articles with abstract nouns see Chapter II, § 8, 9, 10, 11.

Therefore

when the youngsters saw that mother looked neither frightened nor

offended,

they gathered new courage. (Dodge)

Accustomed

to John Reed’s abuse — I never had an idea of replying to it.

(Ch.

Bronte)

It’s

these people with fixed ideas. (Galsworthy)

Category of

number

The

grammatical category of number is the linguistic representation of

the objective category of quantity. The number category is realized

through the opposition of two form-classes: the plural form :: the

singular form.

There are

different approaches to defining the category of number. Thus, some

scholars believe that the category of number in English is restricted

in its realization because of the dependent implicit grammatical

meaning of countableness/uncountableness. The category of number is

realized only within subclass of countable nouns, i.e. nouns having

numeric (discrete) structure. Uncountable nouns have no category of

number, for they have quantitative (indiscrete) structure. Two

classes of uncountables can be distinguished: singularia tantum (only

singular) and pluralia tantum (only plural). M. Blokh, however, does

not exclude the singularia tantum subclass from the category of

number. He calls such forms absolute singular forms comparable to the

‘common’ singular of countable nouns.

In

Indo-European languages there are lots of nouns that don’t fit into

the traditional definition of the category based on the notion of

quantity. A word can denote one object, but it has the plural form.

Or a noun can denote more than one thing, but its form is singular.

There is a definition of the category of number that overcomes this

inconsistency. It was worked out by prof. Isachenko. According to

him, the category of number denotes marked and unmarked discreteness

(not quantity). A word in a singular form denotes unmarked

discreteness whether it is a book, or a sheep, or sheep. If an object

is perceived as a discrete thing, it has the form of the plural

number. Thus, trousers and books are perceived as discrete object

whereas a flock of sheep is seen as a whole. This definition is

powerful because it covers nearly all nouns while the traditional

definition excludes many words.

The

grammatical meaning of number may not coincide with the notional

quantity: the noun in the singular does not necessarily denote one

object while the plural form may be used to denote one object

consisting of several parts. The singular form may denote:

oneness

(individual separate object — a cat);

generalization

(the meaning of the whole class — The cat is a domestic animal);

indiscreteness

(HepacnneHeHHOCTb or uncountableness — money, milk).

The plural

form may denote:

the

existence of several objects (cats);

the inner

discreteness (BHyipeHHaa pacnneHeHHOCTb, pluralia tantum,

jeans).

To sum it

up, all nouns may be subdivided into three groups:

The nouns

in which the opposition of explicit

discreteness/indiscreteness

is expressed: cat::cats;

The nouns

in which this opposition is not expressed explicitly but is

revealed by

syntactical and lexical correlation in the context. There are two

groups

here:

Singularia

tantum. It covers different groups of nouns: proper names, abstract

nouns, material nouns, collective nouns;

Pluralia

tantum. It covers the names of objects consisting of several parts

(jeans), names of sciences (mathematics), names of diseases, games,

etc.

The nouns

with homogenous number forms. The number opposition here is not

expressed formally but is revealed only lexically and syntactically

in the context: e.g. Look! A sheep is eating grass. Look! The sheep

are eating grass

The

category of case.

Case

expresses the relation of a word to another word in the word-group or

sentence (my sister’s coat). The category of case correlates with

the objective category of possession. The case category in English is

realized through the opposition: The Common Case :: The Possessive

Case (sister :: sister’s). However, in modern linguistics the term

“genitive case” is used instead of the “possessive case”

because the meanings rendered by the “`s” sign are not only those

of possession. The scope of meanings rendered by the Genitive Case is

the following :

Possessive

Genitive : Mary’s father – Mary has a father,

Subjective

Genitive: The doctor’s arrival – The doctor has arrived,

Objective

Genitive : The man’s release – The man was released,

Adverbial

Genitive : Two hour’s work – X worked for two hours,

Equation

Genitive : a mile’s distance – the distance is a mile,

Genitive of

destination: children’s books – books for children,

Mixed

Group: yesterday’s paper

Nick’s

school cannot be reduced to one nucleus

John’s

word

To avoid

confusion with the plural, the marker of the genitive case is

represented in written form with an apostrophe. This fact makes

possible disengagement of –`s form from the noun to which it

properly belongs. E.g.: The man I saw yesterday’s son, where -`s is

appended to the whole group (the so-called group genitive). It may

even follow a word which normally does not possess such a formant, as

in somebody else’s book.

There is no

universal point of view as to the case system in English. Different

scholars stick to a different number of cases.

There are

two cases. The Common one and The Genitive;

There are

no cases at all, the form `s is optional because the same relations

may be expressed by the ‘of-phrase’: the doctor’s arrival –

the arrival of the doctor;

There are

three cases: the Nominative, the Genitive, the Objective due to the

existence of objective pronouns me, him, whom;

Case

Grammar. Ch.Fillmore introduced syntactic-semantic classification of

cases. They show relations in the so-called deep structure of the

sentence. According to him, verbs may stand to different relations to

nouns. There are 6 cases:

Agentive

Case (A) John opened the door;

Instrumental

case (I) The key opened the door; John used the key to open the door;

Dative Case

(D) John believed that he would win (the case of the animate being

affected by the state of action identified by the verb);

Factitive

Case (F) The key was damaged ( the result of the action or state

identified by the verb);

Locative

Case (L) Chicago is windy;

Objective

case (O) John stole the book.

The Problem

of Gender in English

In

Indo-European languages the category of gender is presented with

flexions. It is not based on sex distinction, but it is purely

grammatical.

According

to some language analysts (B.Ilyish, F.Palmer, and E.Morokhovskaya),

nouns have no category of gender in Modern English. Prof. Ilyish

states that not a single word in Modern English shows any

peculiarities in its morphology due to its denoting male or female

being. Thus, the words husband and wife do not show any difference in

their forms due to peculiarities of their lexical meaning. The

difference between such nouns as actor and actress is a purely

lexical one. In other words, the category of sex should not be

confused with the category of gender, because sex is an objective

biological category. It correlates with gender only when sex

differences of living beings are manifested in the language

grammatically (e.g. tiger — tigress).

Gender

distinctions in English are marked for a limited number of nouns. In

present-day English there are some morphemes which present

differences between masculine and feminine (waiter — waitress,

widow — widower). This distinction is not grammatically universal.

It is not characterized by a wide range of occurrences and by a

grammatical level of abstraction. Only a limited number of words are

marked as belonging to masculine, feminine or neuter. The morpheme on

which the distinction between masculine and feminine is based in

English is a word- building morpheme, not form-building.

Still,

other scholars (M.Blokh, John Lyons) admit the existence of the

category of gender. Prof. Blokh states that the existence of the

category of gender in Modern English can be proved by the correlation

of nouns with personal pronouns of the third person (he, she, it).

Accordingly, there are three genders in English: the neuter

(non-person) gender, the masculine gender, the feminine gender.

1) The

theory of positional cases

(J.C. Nesfield, M. Deutschbein, M. Bryant)

CASES:

nominative,

genitive, vocative, dative and accusative,

and only the genitive

case is an inflexional one.

The

Nominative case (subject to a verb) Rain

falls.

The

Genitive case. I saw John’s

father.

The

Vocative case

(address) Are

you coming, my friend?

The

Dative case

(indirect object to a verb) I

gave John

a penny.

The

accusative case

(direct object, and also object to a preposition) The

man killed a

rat.

2)

The

theory

of prepositional cases

(G. Curme)

Cases:

dative

case (to

+ noun, for + noun) and genitive

case

(of + noun)

3)

The

limited case theory

(H. Sweet, O. Jespersen, A.I. Smirnitsky, L.S. Barkhudarov)

Cases:

nominative

case (weak

member) and possessive

(strong member of the opposition)

4)

The

theory

of the possessive postposition

or

postpositional theory (G.N.

Vorontsova) According to G.N. Vorontsova, there

are no cases at all

and ‘s

is the postpositional element, which can be transformed: somebody

else’s daughter – the

daughter

of someone else.

Here is a list of some of the most important words which belong to different parts of speech. Note that it is the function or use which determines which part of speech a particular word belongs to.

About

About can be used as an adverb or a preposition. As an adverb, about modifies the verb. As a preposition, it connects a noun or pronoun with some other word in the sentence. Study the examples given below.

They wandered about the town. (Here the word about modifies the verb wandered and hence it acts as an adverb.)

There was something affable about him. (Preposition)

Above

The word above can be used as an adverb, a preposition, an adjective or a noun.

Study the examples given below.

The heavens are above. (Adverb)

The moral code of conduct is above the civil code of conduct. (Preposition)

Read the sentence given above. (Adjective)

Our blessings come from above. (Noun)

After

The word after can be used as an adverb, a preposition, an adjective and a conjunction.

He left soon after. (Adverb)

She takes after her mother. (Preposition)

I went to bed after I had dinner. (Conjunction)

All

All children need love. (Adjective)

She lives all alone in a small hut. (Adverb)

She lost all she owned. (Noun)

Any

Have you got any pens? (Adjective)

Is he any better? (Adverb)

‘Did you get any strawberries?’ ‘There wasn’t any left.’ (Pronoun)

As

We walked as fast as we could. (Adverb)

As he was late, we went without him. (Conjunction)

She likes the same color as I do. (Relative pronoun)