Tools to Unleash Your Students’ Word Power

Research consistently shows the power of vocabulary in determining academic destiny. Students with weak vocabularies tend to decline academically, while students with stronger vocabularies tend to learn faster. VocabularySpellingCity, in partnership with McREL International, released a report showing direct vocabulary instruction, coupled with engaging word and vocabulary study activities, builds critical vocabulary skills necessary to ensure academic success.

“Since we have a large ESOL population, our school-wide focus is on increasing vocabulary development. VocabularySpellingCity has helped support this initiative with its specific activities.”

Shawn Allen, Principal, Lloyd Estates Elementary, Oakland Park, FL

Effective teaching of vocabulary study requires:

- Showing how words are formed.

- Showing how words are used in context.

- Selecting words critical to overall reading comprehension.

Educational research on the importance of vocabulary development has proven:

- This explicit, direct approach has a positive effect on a student’s learning potential.

- Students need between 12 and 15 exposures to a new word in order for it to become rooted into long-term memory.

- Teachers should explicitly teach between 400 and 700 words per year as part of their vocabulary study program.

Effects of Spaced Practice

“VocabularySpellingCity is amazing. It allows me to assign multiple vocabulary lists every week. With differentiated lists, my students’ needs are better addressed. I love that VocabularySpellingCity allows students the individual time they need for tests, gives the students immediate feedback, grades the tests, and keeps all the data organized and logged for me.”

E. Glass, Teacher, Loma Vista Elementary School, Salinas, CA

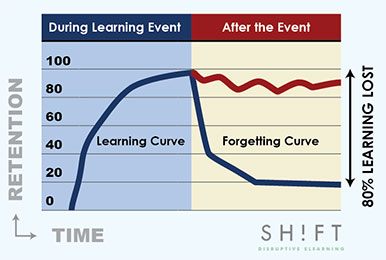

This chart illustrates the ‘spacing effect’: the top trend line represents the learning curve over time using spaced practice while teaching vocabulary study, and the bottom trend line represents the learning curve over time after a single instance of learning.

How can teachers accommodate a learning cycle of practice, review, and revisit with the challenges of a classroom schedule?

This is where VocabularySpellingCity comes to the rescue, providing meaningful practice for teachers to integrate into their existing curriculum for teaching vocabulary study. After you explicitly teach the vocabulary words, students use our site to hear, say, read, write, and play with their words through engaging learning activities, leading to better vocabulary retention. VocabularySpellingCity knows the importance of vocabulary development, and we help teachers provide more effective vocabulary instruction than ever before!

Research-Based for Effectiveness and Better Outcomes in Student Achievement

Educational researchers Robert Marzano and Dr. Joe Lockavitch say learning vocabulary is critical to reading comprehension, writing, and other literacy and communication skills. The National Research Council reported in a 1998 study that in fourth grade, 70 percent of the reading comprehension problem is students’ lack of vocabulary. Blachowicz, Fisher, Ogle and Watts-Taffe’s (2006) review of the research found that this connection can be partly explained by how deeper vocabulary knowledge helps make connections, and a broad verbal ability may be fundamental to all learning.

| Best Practice | How VocabularySpellingCity Supports the Practice |

|---|---|

| Daily Practice | VocabularySpellingCity is a web and app-based productivity tool that students access directly for supplemental vocabulary study practice, whether at school, home, or on the go via computer, Chromebook, tablet, or smartphone. User-based, unlimited access enables teachers to assign student tasks that are tailored to specific word lists and tracked over time, with records of students’ activities and progress, making VocabularySpellingCity a valuable tool when teaching vocabulary study. |

| Strategic Word Selection | Strategic word selection is imperative if teachers are to differentiate word lists. VocabularySpellingCity has leveled lists that support learning high-frequency words and general academic as well as domain-specific vocabulary. When words are selected with students’ needs in mind, students can systematically increase their vocabulary which impacts their academic success and fosters more effective vocabulary instruction. |

| Spaced Practice | Teachers are challenged with managing a cycle in which students practice, review, and revisit vocabulary words. Using VocabularySpellingCity as a productivity tool allows teachers to more easily manage the instructional cycle and allows students to practice their vocabulary words beyond this cycle, leading to better vocabulary retention. |

| Multiple Modalities | VocabularySpellingCity’s learning activities deliver content through audio and visual modalities. Additionally, VocabularySpellingCity’s learning activities provide practice with both open-ended and closed responses, enhancing teaching of vocabulary study. |

| Integrated Practice | VocabularySpellingCity allows teachers to integrate meaningful practice into their existing curriculum. Whether importing a ready-made list or creating a new list, it is easy to select or edit a word’s definition, part of speech, and sentence. |

| Audio Support and Immediate Feedback | Students benefit from both audio support and immediate feedback, while using VocabularySpellingCity. When students hear a word, its syllables, its sounds, its definition and the word being used in context, word knowledge accelerates. Immediate feedback corrects students’ thinking, guides their thought process, and celebrates success, improving the effectiveness of their vocabulary instruction. |

| Students Responsible for Own Learning through Formative Assessments | Students who learn from mistakes take ownership of their learning. Holding students responsible for their results becomes an exercise in metacognition. VocabularySpellingCity provides opportunities for students to receive immediate feedback during practice and after assessments. The immediacy of this feedback allows students to take responsibility for their own learning and take part in making their own instructional decisions. These formative assessments, whether from a practice test or a learning activity, are used by teachers to drive instruction and provide appropriate practice, and by students for self-evaluation and additional vocabulary study practice. |

Read MoreRead Less

Marzano, co-author of Building Academic Vocabulary: Teacher’s Manual, recommends allowing students to generate their own explanation or description of a word, rather than copying the teacher’s description, for stronger comprehension and retention. He adds that playing games with words is a “brain-compatible strategy” for reinforcing learning and is of high importance to vocabulary development.

“Games seem to engage students at a high level and have a powerful effect on students’ recall of the terms,” Marzano says. “Games not only add fun to the teaching and learning process, but also provide an opportunity to review the terms in a non-threatening way. After the class has played a vocabulary game, the teacher should invite students to identify difficult terms and go over the crucial aspects of those terms in a whole-class discussion.”

According to Lockavitch, author of Failure Free Reading:

- Exposure to oral language improves vocabulary growth;

- Repetition improves vocabulary acquisition;

- Computer-assisted multimedia programs impact reading comprehension and standardized test scores.

Lockavitch and other educational researchers say that providing multiple engagements with new words over an extended period is necessary to commit them to long-term memory. Word exposures should be done in ways that engage different senses: The student should read the word, write the word, hear the word, and say the word. To tap into multiple modalities in vocabulary study, Steven A. Stahl (1999) found that teachers must include definitional, contextual, and usage information when explicitly teaching word study. After reading new words, students must be able to access the phonological processes that give those words meaning, by hearing and speaking new words in addition to reading them (University of Michigan, 2016). Marzano reinforced this finding, asserting that as students hear phonemes while seeing corresponding letters in the new words, the brain makes deeper connections leading to retention. Finally, a study by McKeown, Beck, Omanson, & Pople (1985) noted that once students encounter a word 12 times or more, they are better able to comprehend it, and then integrate it into their writing, speech, and play, where it can now become a part of their personal word bank.

Help your students achieve vocabulary growth from year to year. Sample these games from more than 35 activities:

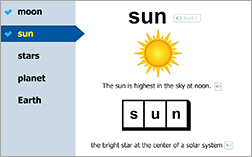

Word Study, when played with a K-2 Number word list, helps build literacy skills with word building and recognition, multiple exposures to words, and vocabulary development and acquisition.

WhichWord? Sentences, when played with a 3rd-5th grade Antonyms word list, helps build literacy skills that increase word knowledge by providing opportunities that apply the ability to make effective choices for meaning.

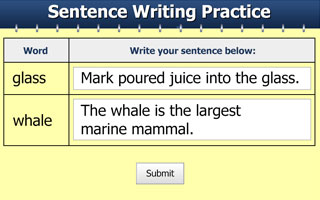

Sentence Writing Practice activity, when completed with a middle school Homophones word list, helps build literacy skills by providing opportunities to apply acquired writing and language skills in context. This is a great activity to apply what is learned by students when teaching vocabulary study.

To request a quote, call 800-357-2157 or email us at sales@spellingcity.com.

Download Article

Download Article

Vocabulary words are tough to memorize at the last minute. Even if you don’t have much time left, however, the right approach will go a long way. Here are many options for studying vocabulary in your native language or a foreign tongue.

-

1

Choose paper or electronic flash cards. Paper flash cards are easy to carry around, and writing by hand may help you memorize the words more than typing.[1]

On the other hand, you can’t lose a phone app or online tool. Some flash card software even lets you speak the words aloud, then writes the cards for you.[2]

- If using paper cards, try to find something small that you can carry in your pocket. Cutting index cards in half works well.[3]

- If using paper cards, try to find something small that you can carry in your pocket. Cutting index cards in half works well.[3]

-

2

Create the cards. Write the vocabulary word on one side of the card. On the other side, write the definition. Optionally, write out how to pronounce the word, and an example sentence using the word.

- You can find example sentences by searching for the word online. Try to find an online news article or book, since those are more likely to use the word correctly.

- Your flashcards don’t need to be fancy as long as they help you learn new words.[4]

Advertisement

-

3

Color code the cards (optional). Color coding can help you sort cards if you’re studying a large number at once. Pull out your highlighters and color the word side of the card. Here are a few systems you could use:

- One color for each vocabulary lesson or chapter.

- One color for each topic (food words, traveling words, etc.).

- One color for each part of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.).

-

4

Sort the cards as you test yourself. To test yourself, shuffle the cards and look at the top one. Read the word aloud, then say what you think the definition is. Turn it over and check yourself. Put cards you got right in one pile, and cards you got wrong in another pile.

- If you’re testing yourself on the go, bring along rubber bands to hold the two piles.

- Most electronic apps have the option to test yourself like this. They may also have games and alternate tests you can use.

-

5

Keep testing yourself. Reread the pile of cards you got wrong, on both sides. Shuffle them and test yourself in the same way. Keep setting aside the cards you get wrong, so you can repeat this until there are no cards left. The length of time to do this will vary depending on how many cards you have.[5]

-

6

Wait 30–60 minutes and test yourself again. Shuffle all the cards again, but wait a while before testing yourself again. You might be surprised how many you forget. Waiting a short time between tests can help commit the words to your long-term memory.

- Try tackling 20-50 new words per week if you’re learning a new language. Focus on most general and essential words before moving on to more specific ones.[6]

- Try tackling 20-50 new words per week if you’re learning a new language. Focus on most general and essential words before moving on to more specific ones.[6]

Advertisement

-

1

Test yourself with a list. If you’re only studying a small number of words, write them down in a vertical list. Write the definition on the same line as each word, on the opposite side of the page. Test yourself by covering the definitions with a folder or book. Read each word aloud and say the definition, then slide the folder down to see whether you got it right.[7]

-

2

Memorize by writing or typing. Write or type the word and the definition as many times as you can. Writing usually works better than typing. The muscle memory will help this stick, but keep in mind that this won’t help your pronunciation or ability to use the word in a sentence.[8]

-

3

Label everything in your house. If you’re learning a foreign language, write the name of household objects on a sticky note, in that language. Over the next few days or weeks, say the name aloud each time you see or use that object.[9]

- Every once in a while, take down the labels you no longer need and put more labels on other objects.

-

4

Make connections between the words and definitions. You’ll find it easier to remember a word if you connect it to something else in your mind. It doesn’t matter how silly it is; you can use anything that will make you think of the definition.

- For example, the word «thespian» means «actor.» Think of an actor asked to play a spy, doing «the spying’.»

- This works for foreign languages as well, especially ones closely related to your own language. For example, the Spanish word «cine» means «movie theater,» just like «cinema» in English.

-

5

Write in shaving cream. Write the word and definition on a chalk board by dragging your finger through a layer of shaving cream. Wipe the surface flat again and try to write it from memory. Repeat many times.

- This is mostly useful for teaching someone else, but the physical sensation may help some people learn.

-

6

Create new sentences. Write five sentences for each vocabulary word you’re having trouble with. You’ll get used to using it in a sentence and thus will be more likely to remember the word.[10]

- If you need to memorize words in a certain order, write a story that uses the words in that order.

Advertisement

Add New Question

-

Question

What is the best way to memorize new words?

Tian Zhou is a Language Specialist and the Founder of Sishu Mandarin, a Chinese Language School in the New York metropolitan area. Tian holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL) from Sun Yat-sen University and a Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) from New York University. Tian also holds a certification in Foreign Language (&ESL) — Mandarin (7-12) from New York State and certifications in Test for English Majors and Putonghua Proficiency Test from The Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. He is the host of MandarinPod, an advanced Chinese language learning podcast.

Language Specialist

Expert Answer

Don’t try to memorize every unknown word at once, especially if you’re learning a new language. The task of memorizing every new word is way too daunting, and can do more harm than good in the learning process.

-

Question

How can I improve my speaking vocabulary in another language?

Tian Zhou is a Language Specialist and the Founder of Sishu Mandarin, a Chinese Language School in the New York metropolitan area. Tian holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL) from Sun Yat-sen University and a Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) from New York University. Tian also holds a certification in Foreign Language (&ESL) — Mandarin (7-12) from New York State and certifications in Test for English Majors and Putonghua Proficiency Test from The Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. He is the host of MandarinPod, an advanced Chinese language learning podcast.

Language Specialist

Expert Answer

Try an activity called «language plank,» where you reply to an open-ended question for a specific amount of time. You might start with a 10-30 second timer and work your way up to a 1-2 minute timer.

-

Question

What if I have to learn really hard words and I have a quiz tomorrow?

Make flashcards. Study them as much as you can on your own, or ask someone to quiz you. Don’t tell yourself that it’s too hard. If you believe in yourself, you can learn the words.

See more answers

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

Video

-

Start studying at least three days before your quiz or test. Cramming at the last minute leaves you tired, and doesn’t give your brain enough time to learn them.[11]

Instead, study for at least fifteen to thirty minutes before bed each night, so your brain thinks them over as you sleep. -

Studying is more fun with a friend.[12]

Have a friend test you using your vocabulary list or flash cards. -

When learning a foreign language, try to connect the words to their meanings, not just the translation in your own language. For instance, when you see the German word Apfel, imagine an actual apple, not just the English word «apple.»

Advertisement

References

About This Article

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 57,503 times.

Reader Success Stories

-

Michael Loop

Jan 13, 2020

«I was lost, but found my way. The article gave me tips to accomplish my mission in improving my vocabulary.»

Did this article help you?

1 Vocabulary Development and Word Study Instruction: Keys for Success in Learning to Read Timothy Rasinski 330-672-0649 Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 1. Students learn 1,000 to 4,000 new words each year. 2. Vocabulary involves a depth component as well as a breadth component. 3. Vocabulary learning involves connotative (inferred/implied) and denotative (literal) meanings of words . 4. Why teach Vocabulary ? a. Improves reading comprehension b. Improves writing. c. Aids in word recognition or decoding.

2 D. Increases general intelligence. 5. Vocabulary is least well learned under the following conditions: a. Mindless repetition and defining of words b. words that are too difficult c. words that have no connection to students lives, their studies, their interests, or to other words and concepts they may know. 6. Best ways to learn/teach words a. Direct life experiences. b. Indirect life experiences Read! c. Direct instruction that includes the following characteristics: 1) Makes connections to what students lives, studies, and interests.

3 2) Makes connections/relationships to/with other words . 3) Involves analysis through compare and contrast. 4) Involves categorization and classification. 5) Involves stories about words . 6) Helps students detect meaningful patterns in words . 7) Provides for a degree of personal ownership.

4 12) Use word knowledge to construct meaning while reading (comprehension) Page 1 Selected Statistics for Major Sources of Spoken and Written Language Text Number of Rare (uncommon) words per 1000 Adult Speech, Expert Witness Testimony Adult Speech, College Graduates to Friends Mr. Rogers and Sesame Street Children s Books — Preschoolers Children s Books — Elementary Comic Books Popular Magazines

5 Newspapers Adult Books Abstracts of Scientific Articles Adapted from Hayes & Ahrens (1988). Journal of Child Language, 15, 395-410. Source: Cunningham, & Stanovich, (1998, Spring-Summer). What reading does for the mind. American Educator, 22, 8-15.

6 Page 2 Vocabulary Development — Concept Map Purpose: To help students develop definitional knowledge in relation to other words and concepts. Procedure: 1. Begin with a key word or words you want students to learn. If it is a word they have some familiarity with they can create the concept map. If it is a word students are probably unfamiliar with, teachers can present a completed concept map to students. 2. Working alone or in small groups, students discuss and choose words , concepts, and phrases that fit the definitional categories of the key word.

7 The definitional categories can include hierarchical concept, comparison/contrast concept, synonymous concepts, characteristics of the key word, and examples of the key concept. 3. If working in groups, students can share they group definition with the class and compare how different groups came up with different responses to the various definitional categories. The various maps can be placed on display for student analysis and comparison. Page 3 GRAMMATICAL CLASS CONCEPT MAP IMPORTANT CHARACTERISTICS IMAGE/ ICON SYNONYMS CATEGORY OR CLASS CONTRASTING IDEA EXAMPLE EXAMPLE EXAMPLE OR TYPE OR TYPE

8 OR TYPE Page 4 Vocabulary Development — List Group Label, Word Sorts Purpose: To brainstorm words related to a particular topic or theme; and to sort those words into various categories. To build background knowledge related to a particular topic. Procedure: 1. Select a topic or theme. This can be a topic to be studied in a subject area, a time of year or holiday, a topic to be read about in an upcoming text. 2. Individually or in small or large groups, students brainstorm word related to the topic.

9 The teacher may also contribute words to this list. 3. Once words are brainstormed, students group 2 or more words and list them together. They also create a label that defines or describes the categorization. 4. Once words are categorized (grouped and labeled), new words can be added to each category (This shows how once randomly listed words are organized, the brain can begin to include other words related to the category, but not originally listed). Students discuss their rationale for organizing and grouping the words .

10 5. Grouped and labeled words can be transformed into a semantic web or an informational outline. Word Sorts 1. Word sorts activities are done is much the same way, except the words and categories are usually predefined by the teacher. 2. In some cases you may have a sort in which the words are already sorted, or categorized. Students are challenged to think of the category names for the sorted words 3. As with List Group Label the actual work of Word Sorts should be accompanied by explanatory discussion.

1. Word Wall

To help your students get more engaged in vocabulary development, you need to nurture word consciousness. This means raising students’ awareness of, and interest in all sorts of words and their meanings.

A Word Wall can help you achieve this. This is a collection of words that are displayed in large visible letters on a wall, bulletin board, or other display surfaces in a classroom.

Source: ELL STRATEGIES & MISCONCEPTIONS

So, set this wall and encourage your students ‘to walk the wall’ and hang their favourite words, new or unknown, on it.

Then, invite their classmates to add sticky notes with pictures or graphics, synonyms, antonyms, or related words. Then, student partners walk along the wall to quiz each other on the words (Graves & Watts-Taffe,2008).

Use the Word Wall one or more times a week. You’ll help your students make connections between new and known words.

Since this is an ongoing activity during the whole year, you can keep observational notes of those students who are posting, responding to their words and those who are not adding words to the wall.

This will help you better understand what your students need to expand their vocabulary.

2. Word Box

Word Box is one of the strategies for teaching vocabulary. This is a weekly strategy that can help students retain and use words more effectively.

Students select words to submit to the word box on Friday. These are words they find interesting or ones they want to understand better. They either use the word in their own sentence or take the same sentence where this word was found.

Then, select five words to teach the following week.

Monday: Introduce the five words in context, explain them, then tack them to the Word Wall.

Tuesday: Ask students to create a non-linguistic representation of the words.

Wednesday: Discuss the meaning of the words allowing think-pair-shares.

Thursday: Ask students to write sentences using those words.

Friday: This is the day to assess students’ learning of the five words using this activity.

Ask one student to answer fill-ins for five words. Give students three cards that can hold up: green cards show they agree with the student’s answer, yellow they are unsure and red ones they disagree.

For assessing, use a checklist with the vocabulary running horizontally across the top margin and the class list running vertically down the side. (Adapted from Grant et al., 2015, p.195)

3. Vocabulary Notebooks

Ask your students to maintain vocabulary notebooks throughout the year where they write the meaning of the new words.

You can introduce a new word each week and work together with students to explore its meaning. Then, ask them to sketch a picture to illustrate the word and present their drawings to the class at the end of the week.

Another way to use vocabulary notebooks :

Students create a chart. The first column indicates the word, where it was found, and the sample sentence in which it appeared.

The other columns depend on your students’ needs.

You can include a column for meaning ( where students define the word or add a synonym), for word parts and related word forms (where they identify the parts and list any other words related to it), a picture, other occurrences (if they have seen or heard this word before, they describe where) and for practice or how they used this word. (Lubliner, 2005)

4. Semantic Mapping

These are maps or webs of words that can help visually display the meaning-based connections between a word or phrase and a set of related words or concepts.

Teach your students how to use semantic mapping. Pick a word you intend to explain, draw a map or web on the board ( or on Zoom whiteboard or any digital tool in case you’re teaching online) and put this word in the centre of the map. Then, ask students to add related words or phrases similar in meaning to the new word. (see the example below)

Source:weebly.com

5. Word Cards

Word cards can help students review frequently learned words and so improve retention.

On one side of the card, students write the target word and its part of speech (whether it’s a verb, noun, adjective, etc.).

On the top half of the other side, they write the word’s definition (in English and/ or a translation). They also write an example and a description of its pronunciation. The bottom half of the card can be used for additional notes once they start using the word.

Ask students to add more information about the word each time they practise or observe it (sentences, collocations, etc.).

Yet, advise them not to add too much information in order to facilitate more reviewing the cards.

Devote regularly class time for students to bring their word cards to class. Involve them in activities such as describing the new words, quizzing one another, categorizing them according to subject or part of speech.

Also, show your students how to store and organize those cards. This is, for instance, by putting them into a box with the categories they select or ordering them in terms of difficulty. (Schmitt & Schmitt, 2005)

6. Word Learning Strategies

Our students often have only partial knowledge of the words they learn in the classroom. This is so since a word can have different meanings which they may not be familiar with.

Therefore, teaching students word learning strategies is important to help them become independent word learners. This is by teaching, modelling and providing a variety of strategies that serve different purposes.

Here are some examples of word-learning strategies.

a) Using word parts

Breaking words into meaningful parts facilitates decoding. So, studying words’ parts can help students guess the meaning of new words from context.

There are three basic ways that word parts are combined in English: prefixing, suffixing, and compounding.

Teach those parts. But, focus on the most occurrent ones.

Providing explanations about their use and meanings with illustration is necessary. Yet, it is still not enough.

You need to provide opportunities for students to experiment with word-building skills.

For instance, you can hand out a list of productive prefixes and have students compile a list of words using them. Then, ask them to compare the function of the prefixes in the various examples.

However, consider your students’ level since word parts are more useful to students with larger vocabularies. For instance, a student who doesn’t know the meaning of the adjective content cannot guess the word discontent.

Remember also that learning word parts is an ongoing process. So, encourage your students to continue experimenting with them. (Zimmerman, 2009a)

b) Asking questions about word

Knowing a word means knowing about its many aspects: its meaning(s), collocations, grammatical function, derivations, and register.

So, you can encourage your students to explore a new word’s meaning(s) by asking them to address detailed questions about those features and answer them.

Students will ask questions like these :

• Are there certain words that often occur before or after the word ? (collocation)

• Are there any grammatical patterns that occur with the word ? (grammar).

• Are there any familiar roots or affixes for this word ? (word parts)

• Is the word used by both men and women? (register/appropriateness)

• Is the word used in both speaking and writing?

(register/appropriateness)

• Could it be used to refer to people? Animals?Things? (meaning)

• Does it have any positive or negative connotations? (meaning) (Zimmerman,2009a)

c) Reflecting

When students learn new words it does not necessarily mean they’ll use them. Students may avoid using words in writing because they are unsure of the spelling. When they speak, they may not be willing to use certain words as they roughly understand them in context.

Encouraging students to self-assess their knowledge of each new word they learn can help them focus on areas needing practices. Here is an example of a self-assessment scale students can use.

Besides these 6 engaging strategies for teaching vocabulary, here are some essential tips to follow while using them :

1) Identify the potential list of words to be taught. Keep the number of words to a minimum (three to five words in one lesson) to ensure there is ample time for in-depth vocabulary instruction, yet enough time for students to practise them.

2) Expose students to multiple contexts in which the new words can be used. This will support them to develop a deeper understanding of these words and how they’re used flexibly.

You can do so by giving students frequent opportunities to hear the meaning of the words, read content where these words are included, and also use them in speaking and writing.

3) Encourage extensive reading because this gives students repeated or multiple exposures to words and is also one of the means by which students see vocabulary in rich contexts.

So, for rich vocabulary development, use a variety of strategies for teaching vocabulary and provide the necessary support and guided practice. Besides, assess vocabulary learning and encourage students to learn more words outside the classroom.

What other Strategies For Teaching Vocabulary would you suggest? I would love to hear from you.

References

Grant, K..B., Golden, S.E., & Wilson, N.S.(2015). Literacy Assessment and Instructional Strategies: Connecting to the Common Core. USA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2002). The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program. In A.E. Farstrup 1 S.J.Samuels (Eds.), what research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp.140-165). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2008). For the love of words: Fostering word consciousness in young readers. The Reading Teacher, 62 (3), 185-193.

Hulstijn, J. & Laufer, B.(2001). Some empirical evidence for the involvement load hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition. Language Learning 51/3:539-58.

Lubliner, SH.(2005). Getting into Words: Vocabulary Instruction That Strengthens Comprehension. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing.

Schmitt, D., & Schmitt, N.(2005). Focus on Vocabulary. New York: Longman.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009a). Word Knowledge: A vocabulary teacher’s handbook. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009b).(ed.). Inside Reading: The Academic Word List in Context. Four Levels. New York: Oxford University Press.

Listen to the interview with Angela Peery:

Sponsored by Google for Education’s Applied Digital Skills and fastIEP

I’ve been an educator for 36 years, and if there’s one thing I think every educator can agree on, it’s that increasing the number of words our students know is a good thing. Period.

This is supported by decades of research:

- A rich vocabulary supports content knowledge in all disciplines. Conceptual understanding, along with both general and specific word knowledge, impacts learning at every age level, starting with oral language development in preschool. When older students know the meaning of specific words and are able to put related words together during a unit of study, they can connect to new content more readily and remember more (Marzano & Simms, 2013).

- Word knowledge is key for reading comprehension. Kindergarten students’ word knowledge predicts reading comprehension in second grade (Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomblin, 1999; Roth, Speece, & Cooper, 2002), and this persists through fourth grade (Wagner, Muse, & Tannenbaum, 2007). Even more surprisingly, Cunningham and Stanovich (1997) find that first-grade students’ vocabulary knowledge predicts their reading comprehension level much later, in the eleventh grade.

- Students who are deficient in vocabulary face numerous obstacles, including having much lower reading comprehension. Their reading range is thus limited, their writing lacks specificity and voice, and their spoken language lacks range of word choice. They risk reading less (both in volume and frequency), not understanding content-area texts or concepts well, writing lackluster essays and reports, and not being able to express themselves as well verbally.

This is why all teachers should address vocabulary instruction head-on.

But what words should be taught? In English language arts/reading classrooms, explicit vocabulary instruction should focus on general academic words (Beck, McKeown & Kucan, 2013). These words cut across disciplines and help students speak, read, and write well in all the academic settings in which they’ll find themselves. In every discipline, there are also domain-specific terms students need to understand and learn.

8 Vocabulary-Building Strategies

Good vocabulary instruction can and should happen throughout the school day. This can happen through incidental learning, when students talk with and listen to others, watch videos, play games, and read independently, through explicit instruction, which are more structured activities, or with the help of digital tools.

The strategies that follow, most of which require very little preparation time, come from three of my books, shown below:

Amazon | Bookshop Amazon Amazon | Bookshop

Strategy 1: Informal Conversations

One of the most powerful things teachers (and adults in the home) can do is to have rich conversations with children. Recent research on conversational turns (LENA, 2017) indicates that the more turns a young child takes in conversation with an adult, the more they grow their vocabulary and verbal acuity in general.

So asking questions of a student, receiving their responses, adding information, and asking them to reflect or add more information—in other words, keeping the conversation going—is important in vocabulary development. This idea has great potential for non-instructional segments of the preschool elementary day like snack time, lining up to go to lunch, and restroom breaks. It also has potential for older students.

Strategy 2: Anchored Word Learning

Anchored Word Learning (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2002) is ideal to use with elementary students where read-alouds are typically part of the daily routine. It can also be used in the upper grades, especially with complex text that is being read aloud and discussed together as a whole class.

For young children, picture books provide excellent sources of higher-level, sophisticated words that are important for expanding vocabulary. They expose students to words they would not typically read within leveled books or on their own. For older children, excerpts from novels, nonfiction texts of various types, and content-area texts can all be used for anchored word learning.

Isabel Beck suggests selecting three general academic words each time the teacher reads aloud a picture book or trade book; these should not be esoteric or archaic terms, but words likely to come up in other academic texts. Older students may be able to handle more words during a read-aloud and class discussion, but teachers are cautioned not to select too many words for one lesson. Three to five words is usually sufficient.

Prior to reading, teachers need to complete three simple preparation steps:

- Select a read-aloud. Choose from books by favorite authors, recommended books, new books, old favorites, picture books, trade books, and content-area texts that impart critical information.

- Identify three to five words for direct instruction. Select words which will expand students’ vocabulary and will likely appear in varied contexts—or focus on words critically important to the content being taught. “Nice to know” words don’t have a place here. The idea is to teach important words that are likely to appear in various contexts or words you really want students to know.

- Mark the words in the text with a sticky note or with a highlighter and annotations if the text is on paper.

Once this preparation is complete, follow these steps with students:

- Read the entire text aloud. Don’t stop in the first reading to discuss the words at length. Students need to hear complex texts being read aloud fluently—especially a first reading—so they can start to process the story itself or the complicated ideas present in many nonfiction and content-specific texts.

- After reading the text through once, go back and bring attention to each targeted word. You may want to reread the sentences and/or paragraphs in which each word appears.

- Have students say each word aloud.

- Write each word so it’s visible to students. You may want to have students write the words down as well (or use their fingers and “write” the words in the air or in the palms of their hands). With younger students, spell the word as you write it. Call attention to any interesting spelling feature, such as double letters, silent E, prefixes, etc.

- Provide a student-friendly definition of each word. You may want to repeat this several times.

- Provide examples for each word beyond the context of the text. Encourage children to provide examples of their own so they personalize the word, relating it to their own context. This is a great time to use think-pair-share or turn-and-talk.

- If desired, post these words on your academic word wall. If you’re an ELA/reading teacher, you may want to have a section of the word wall dedicated to words from read-alouds.

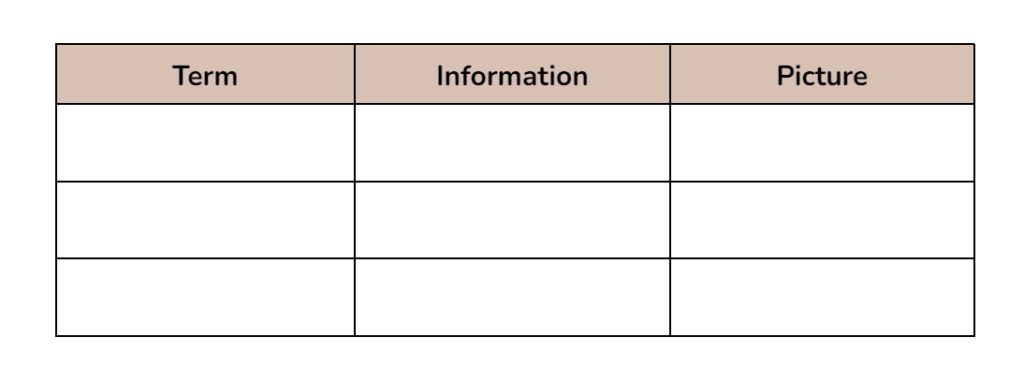

Strategy 3: TIP Chart

This adaptation of a word wall features a visual in addition to a brief definition. TIP stands for term, information, and picture. Basically, a TIP Chart (Rollins, 2014) is a three-column poster displayed so students can quickly use it to remind them of the meaning of an important content-area (tier three) word. In essence, it’s a vocabulary anchor chart.

Unlike the well-known Frayer Model, the TIP Chart is useful for words that are fairly straightforward in meaning—not ones with heavy conceptual weight. Once completed, the TIP Chart serves as an “at a glance” reference for important disciplinary terms; this purpose must be kept in mind if the strategy is to be most beneficial.

TIP charts are displayed prominently for the whole class to see, but students can also keep personal TIP charts in their notebooks or digital files as well. The teacher can first model how to create the chart, and later, students can be involved in deciding what information to record and what picture to draw to go with each word.

The best time to use the strategy is when beginning a new chunk of instruction, like a chapter or unit. With the chart ready, announce the first word and call students’ attention to the importance of this word in the current segment of instruction. Write the word in column one. Then share the formal and full definition, which ideally would also be printed in the text or on a screen or board in the classroom. Along with students, from this full definition, develop a short, student-friendly definition or a brief list that you write in the middle column. Do not write the full, formal definition in column two. Lastly, provide or co-create a simple visual in column three.

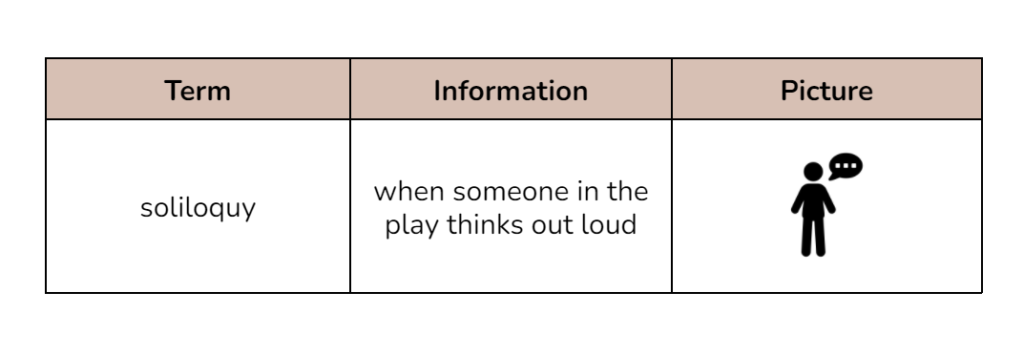

So, for the term soliloquy in my 9th grade English class, I would first give the formal definition: A long, usually serious speech that a character in a play makes to an audience and that reveals the character’s thoughts. We might talk for a minute about the fact that playwrights use soliloquies so the audience understands what a character is thinking. So, in the middle column, we might write the student-friendly, casual definition: When someone in the play thinks out loud. And, to emphasize the fact that this kind of speech is usually given with the character standing alone on the stage, I might then draw a single stick figure with lines or a speech bubble emanating from its face to indicate that he or she is speaking.

The TIP Chart in my class might look something like this:

Here’s a social studies example. For the term “monopoly,” the full definition might be “the exclusive possession or control of the supply or trade in a commodity or service.” It is assumed that the teacher is also teaching the term “commodity” along with “monopoly.” In column two for “monopoly,” the teacher may write “control of a product or service.” In the third column, he or she might draw a large square that surrounds smaller squares, thus showing the dominance of the one provider. Students might also suggest something that symbolizes a monopoly to them, like an iPhone surrounded by other types of cell phones, but the iPhone appears much larger or more prominent, or the other phones are crossed out.

Teachers can gradually do less in whole-class fashion with TIP charts and encourage students to create their own in hard-copy notebooks or digital notebooks using Google Docs, LiveBinders, or OneNote. Students might preview the first part of each chapter or unit (in any class) and try to complete a personal TIP chart to be kept in their organizational system. They could also collaborate with other students to create TIP charts, so that if any individual is confused about a word, they can get ideas from others. This is a portable strategy students can use with any content area and any textbook from elementary school well into college.

Strategy 4: Save the Last Word for Me

Save the Last Word for Me (Beers, 2003) is an ideal strategy to promote peer conversation, increase engagement, and promote deeper processing about vocabulary and content. Although it’s usually applied to conversations about literature, its clearly defined structure is perfect for reviewing vocabulary and gaining deeper understanding of specific terms.

It is fairly typical for teachers to provide guided review activities before a unit test, midterm, or final exam. Let’s say the instructional unit includes about 25 terms which students must recognize and understand how to use correctly within context. Save the Last Word for Me serves as an engaging vehicle for students to practice doing so in preparation for an assessment.

The steps for employing this strategy are as follows; the first three need to be completed ahead of time:

- Print multiple sets of cards with a target word on one side and the definition on the reverse side (one set for each group of students).

- Print the directions for the activity (see below).

- Place the printed directions and terms in a plastic bag or manila envelope for each group of students.

- Divide students into groups of three to five. It’s important that groups are small so each student has an opportunity to discuss. The goal is for students to review and deepen understanding about concepts and specific terms, so making sure they clarify their thinking aloud is important.

To begin, one student draws a card from the deck and another student defines the term. Moving around the circle, each student adds to the definition, refining and adding examples along the way. The person who draws the cards gets the “last word” and can add to the definition or revise it before students agree upon a definition. You may want to model the process in whole-class fashion first or by having a small group model the process as the rest of the class watches.

Sometimes, if the bank of terms is large, I suggest simply printing one master deck of cards and place five or six cards in each bag. After a few minutes, signal the groups to trade bags of terms and, in so doing, each group gets new terms to review.

While Save the Last Word for Me is low-tech, sometimes simpler is better. It delivers by supporting interaction and engagement, deeper conversations, and higher-level processing.

Student Directions for Save the Last Word for Me

- One student selects a card from the deck and says the term aloud with the other group members.

- On a piece of paper, each student jots down what they know about the term. (This can also be “in your head” and each person takes about 30 seconds to think about what they know about the meaning.)

- When everyone is finished, each person takes a turn sharing their reflections/responses. As each participant shares their thoughts, other students can share thoughts and responses.

- The student who drew the card gets the last word by sharing their reflections/reactions or by stating a fresh view if the responses of others have altered their original thinking.

- If students are unsure or need clarification, they refer to the text, notes, and/or handouts for clarification.

- Another student draws a new card, and the process is repeated.

Strategy 5: SNAP Minilessons

Setting aside specific time daily, weekly, or periodically to explicitly teach general academic vocabulary through minilessons (of 5 to 15 minutes each) is another way you can provide explicit instruction.

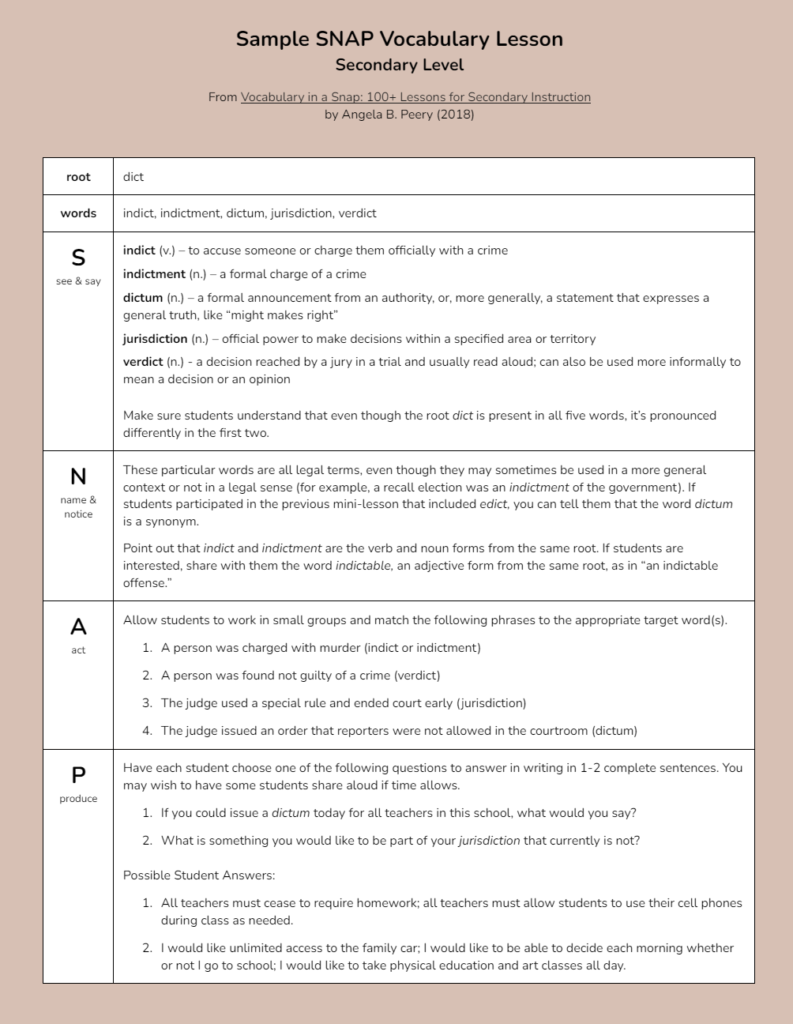

Each minilesson in my books contains four core components or steps, which the acronym SNAP in the title represents:

S: Seeing and saying each word

N: Naming a category or group each word belongs to or noticing connections to related words or word families

A: Acting on the words (engaging in a brief task or conversation about the words)

P: Producing an individual, original application of the words

The example below is intended for secondary students.

Strategy 6: Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy

The primary purpose of the Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy (VSS) (Haggard, 1986) is to help students generate a list of words to be learned based on their prior knowledge and experience with reading and texts. This strategy can stimulate word growth and independence as students read texts and select vocabulary which they deem important to understanding the content.

VSS includes the following steps:

- Selecting words

- Defining words

- Finalizing word lists

- Extending word knowledge

The strategy can be used to support general word learning from one’s environment or to support vocabulary learning from assigned and self-selected texts.

A colleague of mine routinely used this strategy to support general word learning with college freshmen. Every week, students “collected” three words from their environment (watching, listening, and reading) that they thought important to learn. For each word, students included the following information

- An accurate definition

- Where they heard or read the word including a bit of the context

- A justification for why they thought the word was important to learn

Words were shared and discussed in class at an established time each week. Students also recorded their words in personal vocabulary notebooks. VSS engaged students in lively discussions and specifically raised word consciousness, a critical goal of word learning.

Another way VSS can be implemented is to specifically support word acquisition from content-area text. To support content learning, students can work in cooperative groups and read a chapter from a textbook (or any text). As they read, they identify words they think should be studied and mastered. During class discussion, groups then share their words and why they think the terms are important to mastering content. Additional steps can include developing a class list that contains one word from each group, creating TIP charts with the words, and having students teach minilessons focused on the words to each other.

Strategy 7: Word Talks

Word talks were derived from a similar strategy called book talks, in which students give a brief (less than five minutes) presentation about a book they recommend to their peers for independent reading. Word talks are similar in that they require a student to give a brief presentation on one or several words that they feel are important for their peers to know. This strategy is, like some others in this chapter, excellent for general academic words, not highly specialized, domain-specific words. Also, it can be easily combined with the Vocabulary Self-Collection strategy discussed earlier.

Some teachers who use word talks schedule a certain day a week or a certain day per month on which several students get up and do their word talks. Other teachers schedule a rotation so that a few times a week, one student is doing a word talk that day. Because the word talks consist of a student teaching their peers, it’s important to make time for this, because students tend to find the periods in which their classmates are leading discussion much more memorable than when the teacher is; students often have a way of saying something that “clicks” with their peers just because it’s said in a kid-friendly way.

What kind of words should students share in word talks? Many students share from their independent reading and their media and technology use. Teachers can ask students to provide a rationale for each word chosen if they like, but they can also allow students to share any word that might be interesting. I find myself thinking of the character Sam in the Netflix series Atypical as a high school student. He would have certainly loved to share words related to penguins and Antarctica in word talks.

In a word talk in one of my high school classes, a student selected the following words to share: ascent, descent, decompression, and recompression. Can you tell what the student was learning to do outside of school? Scuba diving. This student was studying for her initial scuba certification and thought these words would be good to share because although they have scuba-specific meanings, they also have application to non-scuba situations.

Word talks are great opportunities for some students to showcase their interests and expertise, but most importantly, they make clear that continual word learning is important.

Strategy 8: Digital Tools for Independent Practice

The following websites/programs offer support for you as a teacher as well as independent practice activities for students:

Flocabulary

This robust program includes hip-hop type videos to help students learn new terminology.

Freerice

This site has an addictive vocabulary game with five difficulty levels, with levels one and two being appropriate for students in grades three and up.

Vocabador

This game allows students to study SAT vocabulary words, choose an avatar, and “get into the ring” to play against other virtual wrestlers.

There’s nothing negative that comes about when anyone grows their vocabulary—and for students, there are many, many positives. By adding even a few of these strategies to your repertoire, you’ll help students build vocabularies that will support them no matter what path they choose to pursue.

References

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Beers, K. (2003). When kids can’t read, what teachers can do: A guide for teachers 6–12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Zhang, X., & Tomblin, J. B. (1999). Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(4), 331–361.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 934–945.

Haggard, M. R. (1986). The vocabulary self-collection strategy: Using student interest and world knowledge to enhance vocabulary growth. Journal of Reading, 29(7), 634–642.

LENA. 2017. Proving the Power of Talk: 10 Years of Research on the Impact of Language on Young Children. Available at https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3975639/Research_Summary.pdf?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lena.org%2F.

Marzano, R. J., & Simms, J. A. (2013). Vocabulary for the Common Core. Bloomington, IN: Marzano Research.

Rollins, S. P. (2014). Learning in the fast lane: 8 ways to put all students on the road to academic success. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wagner, R. K., Muse, A. E., & Tannenbaum, K. R. (Eds.). (2007). Vocabulary acquisition: Implications for reading comprehension. New York: Guilford Press.

Come back for more.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.