The most

important distinguishing feature of the Germanic languages was their

word-stress. In Germanic, like in other Indo-European languages, it

was free, that is it might fall on any part of a word. Later it has

been replaced by a fixed stress falling regularly on the first

syllable. The effect of this fixed stress was considerable for

English: many important changes have taken place in unstressed

syllables. They tended to become weakened and gradually were lost.

All this led to crucial simplification in the system of English

paradigm

Periodization of the english language history

OLD

ENGLISH

from 7th

down to 1050 — the period of “full endings”

Transition

Period

from 1050 to 1150

MIDDLE

ENGLISH

from

1150 to 1500 – the period of “levelled endings”

EARLY

MODERN

ENGLISH

from 1500 to 1660

MODERN

ENGLISH

from 1700 till the present – the period of “lost endings”

(H.Sweet)

Old english vowel system

Front short

vowels: i,

e, y, æ

Back short vowels: a,

o, u

Short diphthongs: ea,

eo, ie, io

Front long

vowels: ī,

ē, y, æ

Back long vowels: ā,

ō, ū, å

Long diphthongs: ēa,

ēo, īe, īo

Front mutation (I-umlaut)

a > e

(*framian > fremman виконувати)

æ >

e

(*tælian

> telan говорити)

ā >

æ

(*lārian > læran

вчити)

o > e

(*ofstian > efstan поспішати)

ō >

ē

(*dōmian

> dēman

припускати,

думати)

u > y

(*fullian > fyllan заповнювати)

ū

>

y

(cūþian > cyþan повідомляти)

Diphthongs:

ea

> ie

(*hleahian

> hliehhan

сміятися)

ēa

> īe

(*hēarian

> hīeran

слухати)

eo

> ie

(*āfeorrian

> āfierran

знищувати,

прибирати)

ēo

> īe

(*3etrēowi

> 3etrīewe

вірний)

Back mutation (u-umlaut)

i >

io

(hira > hiora їхній,

silufr

> siolufr срібло)

e

> eo

(herot

> heorot

олень,

hefon

> heofon

небеса)

a >

ea

(saru > searu лати)

Breaking (fracture)

e >

ea

before “r+cons.”, “l+cons.”, “h+cons.”, “h” in the

final syllable (*ærm

> earm, *

æld

> eald, *

æhta

> eahta)

e >

eo

before “r+cons.”, “h+cons.”, “lc, lh,”, “h” in the

final syllable (*herte > heorte, *melcan > meolcan)

Contraction of vowel groups

1. “ah +

vowel” > ēa

(*slahan > slēan вбивати)

2. “eh

+ vowel”,

“ih

+ vowel”

> ēo

(*sehan

> sēon

бачити *tihan

> tēon

звинувачувати)

3. “oh

+ vowel

> ō

(*fohan

> fōn

хапати)

4. ē

and

ō could absorb the following vowel (*sæē

> sæ

морю)

Influence of palatalization

OE front

vowels could be diphthongized when preceded by palatal consonants 3,

c,

and other vowels – by cluster sc:

e > ie

(*3efan > 3iefan давати)

æ > ea

(*3æf

> 3eaf

дав)

æ > ēa

( *3æfon

> 3ēafon

дав)

a > ea

(*scacan > sceacan трусити)

o > eo

(*scort > sceort короткий)

.Vowel

lengthening

In the 9th

century short vowels were lengthened before the clusters nd,

mb, ld, rd:

OE: bindan

> bīndan (to bind)

climban > clīmban

(to climb)

cild > cīld

(child)

If nd,

mb, ld, rd were

followed by a third consonant the lengthening didn’t take place:

OE: cild

> cīld (child), but

cildru

(children)

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Слайд 1

Linguistic features of Germanic languages

Слайд 2

Phonetics – 1) word stress

2) vowels

3) consonants

Morphology – 1) changing of grammatical forms

2) parts of speech

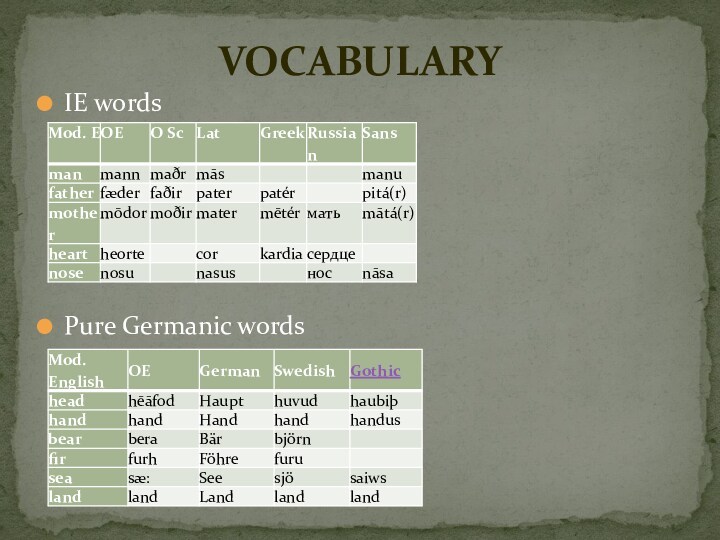

Vocabulary

CONTENTS

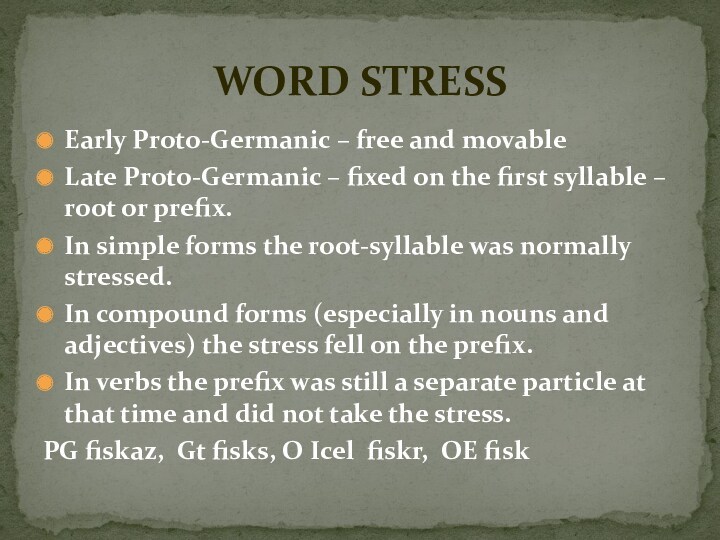

Слайд 3

Early Proto-Germanic – free and movable

Late Proto-Germanic –

fixed on the first syllable – root or prefix.

In simple forms the root-syllable was normally stressed.

In compound forms

(especially in nouns and adjectives) the stress fell on the prefix.

In verbs the prefix was still a separate particle at that time and did not take the stress.

PG fiskaz, Gt fisks, O Icel fiskr, OE fisk

WORD STRESS

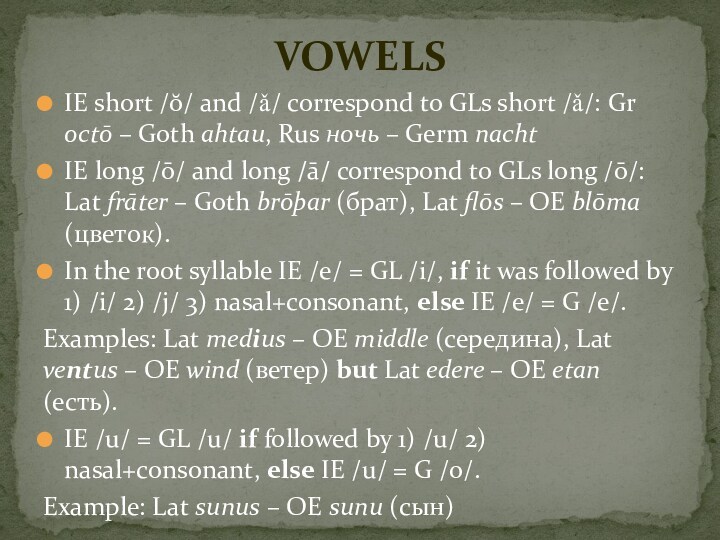

Слайд 4

IE short /ŏ/ and /ǎ/ correspond to GLs

short /ǎ/: Gr octō – Goth ahtau, Rus ночь

– Germ nacht

IE long /ō/ and long /ā/ correspond to

GLs long /ō/: Lat frāter – Goth brōþar (брат), Lat flōs – OE blōma (цветок).

In the root syllable IE /e/ = GL /i/, if it was followed by 1) /i/ 2) /j/ 3) nasal+consonant, else IE /e/ = G /e/.

Examples: Lat medius – OE middle (середина), Lat ventus – OE wind (ветер) but Lat edere – OE etan (есть).

IE /u/ = GL /u/ if followed by 1) /u/ 2) nasal+consonant, else IE /u/ = G /o/.

Example: Lat sunus – OE sunu (сын)

VOWELS

Слайд 5

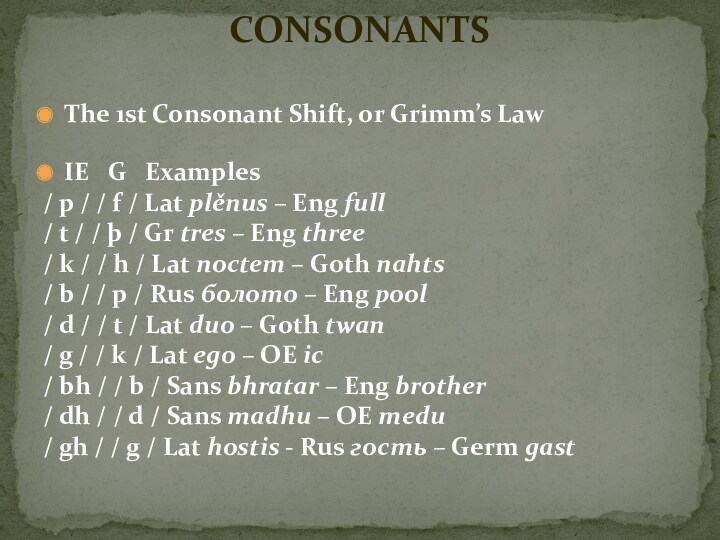

The 1st Consonant Shift, or Grimm’s Law

IE

G Examples

/ p / / f / Lat

plěnus – Eng full

/ t / / þ / Gr

tres – Eng three

/ k / / h / Lat noctem – Goth nahts

/ b / / p / Rus болото – Eng pool

/ d / / t / Lat duo – Goth twan

/ g / / k / Lat ego – OE ic

/ bh / / b / Sans bhratar – Eng brother

/ dh / / d / Sans madhu – OE medu

/ gh / / g / Lat hostis — Rus гость – Germ gast

CONSONANTS

Слайд 6

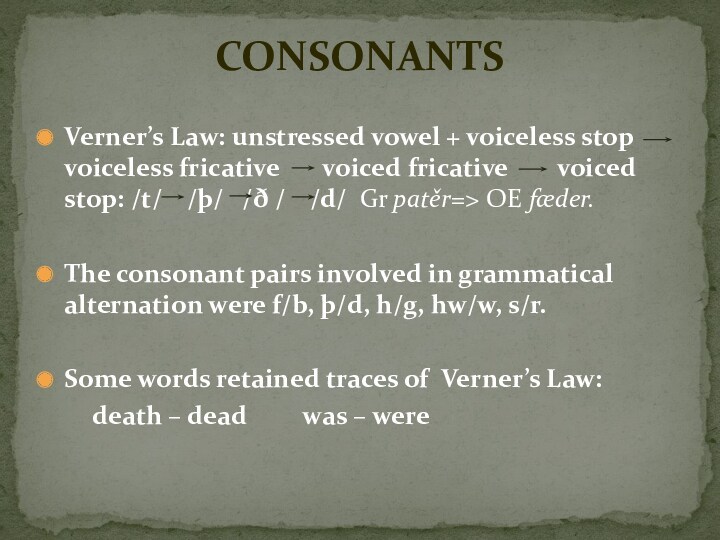

Verner’s Law: unstressed vowel + voiceless stop

voiceless fricative voiced fricative

voiced stop: /t/ /þ/ /ð /

/d/ Gr patěr=> OE fæder.

The consonant pairs involved in grammatical alternation were f/b, þ/d, h/g, hw/w, s/r.

Some words retained traces of Verner’s Law:

death – dead was – were

CONSONANTS

Слайд 7

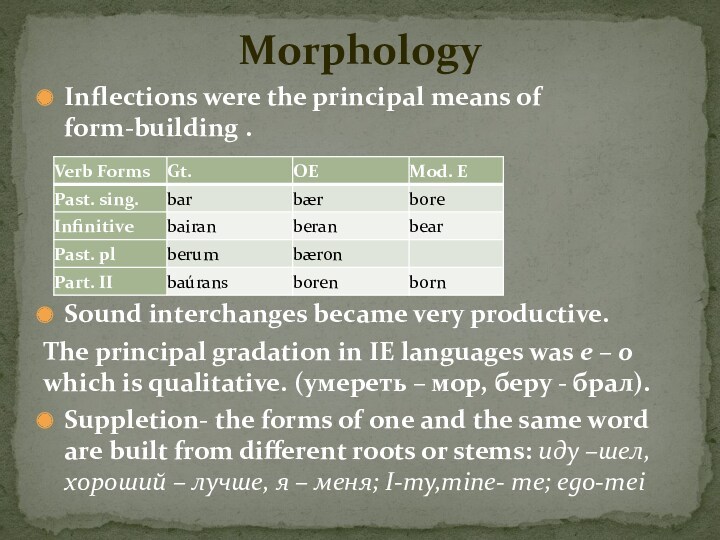

Inflections were the principal means of form-building .

Sound

interchanges became very productive.

The principal gradation in IE languages

was e – o which is qualitative. (умереть – мор,

беру — брал).

Suppletion- the forms of one and the same word are built from different roots or stems: иду –шел, хороший – лучше, я – меня; I-my,mine- me; ego-mei

Morphology

Слайд 8

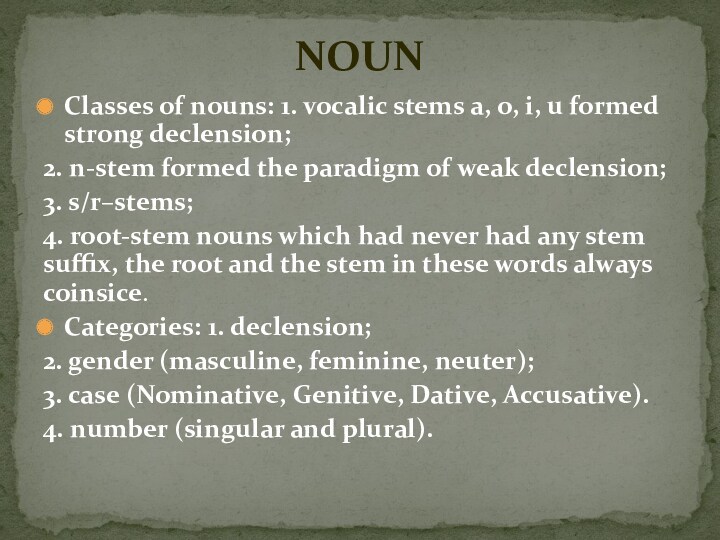

Classes of nouns: 1. vocalic stems a, o,

i, u formed strong declension;

2. n-stem formed the paradigm

of weak declension;

3. s/r–stems;

4. root-stem nouns which had never had

any stem suffix, the root and the stem in these words always coinsice.

Categories: 1. declension;

2. gender (masculine, feminine, neuter);

3. case (Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative).

4. number (singular and plural).

NOUN

Слайд 9

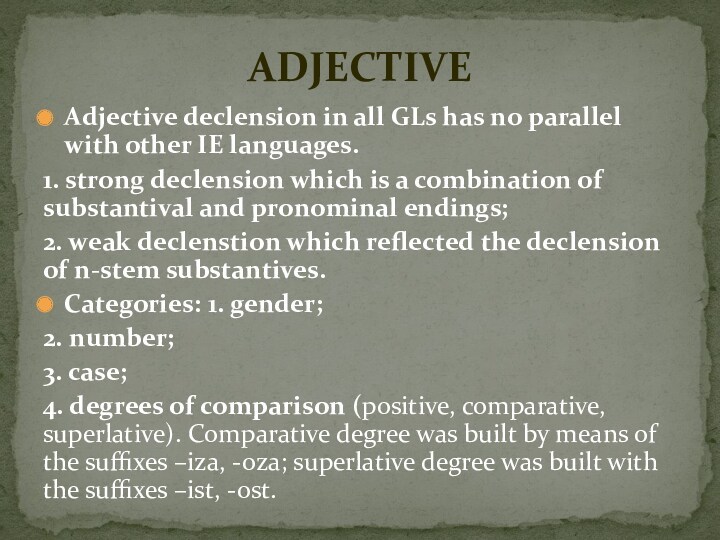

Adjective declension in all GLs has no parallel

with other IE languages.

1. strong declension which is a

combination of substantival and pronominal endings;

2. weak declenstion which reflected

the declension of n-stem substantives.

Categories: 1. gender;

2. number;

3. case;

4. degrees of comparison (positive, comparative, superlative). Comparative degree was built by means of the suffixes –iza, -oza; superlative degree was built with the suffixes –ist, -ost.

ADJECTIVE

Слайд 10

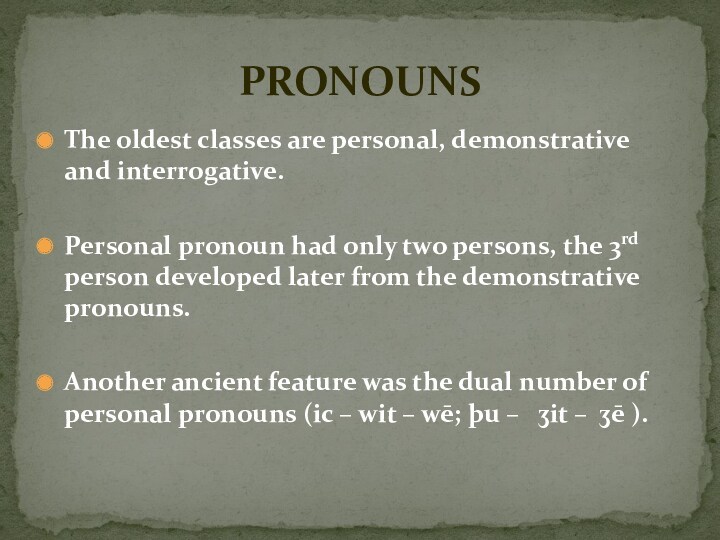

The oldest classes are personal, demonstrative and interrogative.

Personal

pronoun had only two persons, the 3rd person developed

later from the demonstrative pronouns.

Another ancient feature was the dual

number of personal pronouns (ic – wit – wē; þu – ʒit – ʒē ).

PRONOUNS

Слайд 11

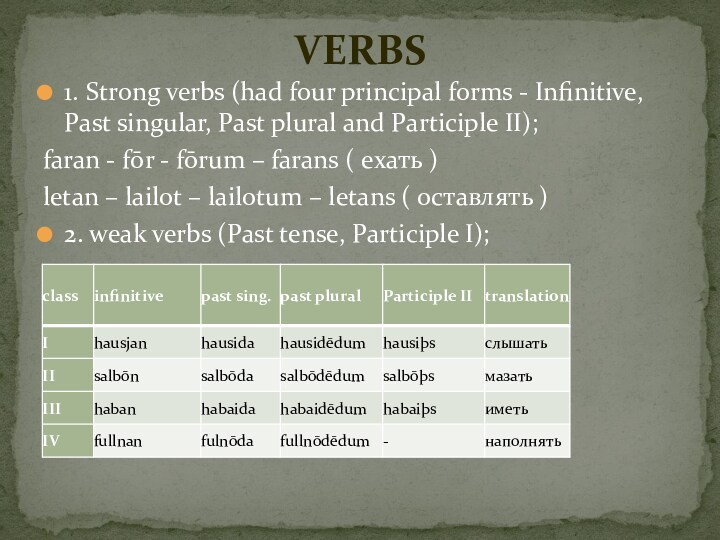

1. Strong verbs (had four principal forms —

Infinitive, Past singular, Past plural and Participle II);

faran —

fōr — fōrum – farans ( ехать )

letan –

lailot – lailotum – letans ( оставлять )

2. weak verbs (Past tense, Participle I);

VERBS

Слайд 12

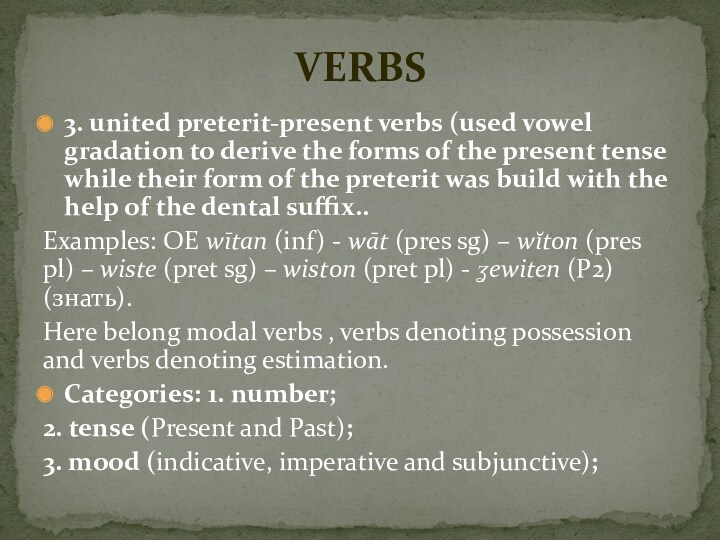

3. united preterit-present verbs (used vowel gradation to

derive the forms of the present tense while their

form of the preterit was build with the help of

the dental suffix..

Examples: OE wītan (inf) — wāt (pres sg) – wĭton (pres pl) – wiste (pret sg) – wiston (pret pl) — ʓewiten (P2) (знать).

Here belong modal verbs , verbs denoting possession and verbs denoting estimation.

Categories: 1. number;

2. tense (Present and Past);

3. mood (indicative, imperative and subjunctive);

VERBS

Слайд 13

IE words

Pure Germanic words

VOCABULARY

References

Alber, B. 1997a. Il sistema metrico dei prestiti del tedesco. Aspetti e problemi della teoria prosodica. Ph.D. thesis, University of Padova.

Alber, B. 1997b. “Quantity sensitivity as the result of constraint interaction.” In Booij, G. and van de Weijer, J. (eds.), Phonology in Progress – Progress in Phonology, HIL Phonology Papers III. Holland Academic Graphics: The Hague: 1–45.

Alber, B. 1998. “Stress preservation in German loan words.” In Kehrein and Wiese (eds.): 113–114.

Alber, B. 2001. “Maximizing first positions.” In Féry, C., Green, A. D., and van de Vijver, R. (eds.), Proceedings of HILP 5, University of Potsdam: 1–19.

Alber, B. 2005. “Clash, lapse and directionality,” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 23: 485–542.

Alber, B., DelBusso, N., and Prince, A. 2016. “From intensional properties to universal support,” Language 92.2: e88–e116.

Árnason, K. 1999. “Icelandic and Faroese.” In van der Hulst, (ed.): 567–596.

Árnason, K. 2011. The Phonology of Icelandic and Faroese. Oxford University Press.

Basbøll, H. 2005. The Phonology of Danish. Oxford University Press.

Booij, G. 1999. The Phonology of Dutch. Oxford University Press.

Bruce, G. 1999. “Swedish.” In van der Hulst (ed.): 554–567.

Burzio, L. 1994. Principles of English Stress. Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. and Halle, M. 1968. The Sound Pattern of English. Harper and Row: New York.

Deaton, K., Noske, M., and Ziolkowski, M. (eds.), CLS 26-II: Papers from the Parasession on the Syllable in Phonetics and Phonology. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Domahs, U., Plag, I., and Carroll, R. 2014. “Word stress assignment in German, English and Dutch: Quantity-sensitivity and extrametricality revisited,” The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 17: 59–96.

Domahs, U., Wiese, R., Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, I., and Schlesewsky, M. 2008. “The processing of German word stress: Evidence for the prosodic hierarchy,” Phonology 25: 1–36.

Dresher, E. 2013. “The influence of loanwords on Norwegian and English stress,” Nordlyd 40.1: 55–43.

Duden Aussprachewörterbuch 2005. 6. Auflage. Mannheim, Leipzig, Wien, and Zürich: Dudenverlag.

Eisenberg, P. 1991. “Syllabische Struktur und Wortakzent: Prinzipien der Prosodik deutscher Wörter,” Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 10: 37–64.

Féry, C. 1995. “Alignment, syllable and metrical structure in German,” SfS-Report-02–95, University of Tübingen.

Féry, C. 1998. “German word stress in Optimality Theory,” Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 2: 101–142.

Gaeta, L. 1998. “Stress and loan words in German,” Rivista di Linguistica 10.2: 355–392.

Giegerich, H. 1985. Metrical Phonology and Phonological Structure: German and English. Cambridge University Press.

Golston, C. and Wiese, R. 1998. “The structure of the German root.” In Kehrein, W. and Wiese, R. (eds.), Phonology and Morphology of the Germanic Languages. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag: 165–187.

Gordon, M. 2002. “A factorial typology of quantity-insensitive stress,” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20: 491–552.

Halle, M. and Vergnaud, J-R. 1987. An Essay on Stress. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hammond, M. 1984. Constraining Metrical Theory: A Modular Theory of Rhythm and Destressing. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Hammond, M. 1999. The Phonology of English: A Prosodic Optimality-Theoretic Approach. Oxford University Press.

Hayes, B. 1981. A Metrical Theory of Stress Rules. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Hayes, B. 1995. Metrical Stress Theory: Principles and Case Studies. University of Chicago Press.

Hulst, H. van der 1984. Syllable Structure and Stress in Dutch. Dordrecht: Foris.

Hulst, H. van der (ed.) 1999. Word Prosodic Systems in the Languages of Europe. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hulst, H. van der, Goedemans, J-R., and van Zanten, E. (eds.) 2010. A Survey of Word Accentual Patterns in the Languages of the World. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hyde, B. 2001. Metrical and Prosodic Structure in Optimality Theory. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University. ROA-476.

Hyde, B. 2002. “A restrictive theory of stress,” Phonology 19: 313–360.

Hyde, B. 2007. “Non-finality and weight-sensitivity,” Phonology 24: 287–334.

Hyde, B. 2012. “Alignment constraints,” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 30: 1–48.

Hyde, B. 2016. Layering and Directionality: Metrical Stress in Optimality Theory. London: Equinox.

Itô, J. and Mester, A. 2015. “The perfect prosodic word in Danish,” Nordic Journal of Linguistics 38.1: 5–36.

Janßen [Domahs], U. 2003. Untersuchungen zum Wortakzent im Deutschen und Niederländischen. Doctoral dissertation. University of Düsseldorf.

Janßen [Domahs], U. and Domahs, F. 2008. “Going on with optimised feet: Evidence for the interaction between segmental and metrical structure in phonological encoding from a case of primary progressive aphasia,” Aphasiology 22.11: 1157–1175.

Jessen, M. 1999. “German.” In van der Hulst, (ed.): 515–545.

Kager, R. 1989. A Metrical Theory of Stress and Destressing in English and Dutch. Ph.D. dissertation. Foris Publications, Dordrecht.

Kager, R. 1993. “Alternatives to the iambic-trochaic law,” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 11: 381–432.

Kager, R. 2007. “Feet and metrical stress.” In de Lacy, P. (ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology. Cambridge University Press: 195–227.

Kaltenbacher, E. 1994. “Typologische Aspekte des Wortakzents: Zum Zusammenhang von Akzentposition und Silbengewicht im Arabischen und Deutschen,” Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 13: 20–55.

Kehrein, W. and Wiese, R. (eds.) 1998. Phonology and Morphology of the Germanic Languages. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Knaus, J. Wiese, R., and Domahs, U. 2011. “Secondary stress is distributed rhythmically within words: an EEG study on German.” In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference of the Phonetic Sciences 2011. Hong Kong: 1114–1117.

Knaus, J. and Domahs, U. 2009. “Experimental evidence for optimal and minimal metrical structure of German word prosody.” Lingua 119.10: 1396–1413.

Kristoffersen, G. 2000. The Phonology of Norwegian. Oxford University Press.

Lacy, P. de 2007. The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology. Cambridge University Press.

Lahiri, A., Riad, T., and Jacobs, H. 1999. “Diachronic prosody.” In van der Hulst, (ed.): 335–422.

Liberman, M. and Prince, A. 1977. “On stress and linguistic rhythm,” Linguistic Inquiry 8: 249–336.

Lorentz, O. 1996. “Length and correspondence in Scandinavian,” Nordlyd 24: 111–128.

McCarthy, J. and Prince, A. 1993. “Generalized alignment,” Yearbook of Morphology 1993: 79–153.

McManus, H. 2006. Stress Parallels in Modern OT. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University.

Moulton, W. G. 1962. The Sounds of English and German. University of Chicago Press.

Pater, J. 2000. “Non-uniformity in English secondary stress: The role of ranked and lexically specific constraints,” Phonology 17: 237–274.

Prince, A. 1983. “Relating to the Grid,” Linguistic Inquiry 14: 19–100.

Prince, A. 1990. “Quantitative consequences of rhythmic organization.” In Deaton, K., Noske, M., and Ziolkowski, M. (eds.), CLS 26-II: Papers from the Parasession on the Syllable in Phonetics and Phonology. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society: 355–398.

Prince, A. and Smolensky, P. 2004 [1993]. Optimality Theory: Constraint Interaction in Generative Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Riad, T 2013. The Phonology of Swedish. Oxford University Press.

Rice, C. 1999. “Norwegian.” In van der Hulst (ed.): 545–553.

Rice, C. 2006. “Norwegian stress and quantity: The implications of loanwords,” Lingua 116: 1171–1194.

Speyer, A. 2009. “On the change of word stress in the history of German,” Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur (PBB) 131.3: 413–441.

Trommelen, M. and Zonneveld, W. 1999. “Dutch.” In van der Hulst, (ed.): 492–515.

Vennemann, T. 1990. “Syllable structure and simplex accent in Modern Standard German.” In Deaton, K., Noske, M., and Ziolkowski, M. (eds.), CLS 26-II: Papers from the Parasession on the Syllable in Phonetics and Phonology. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society: 399–412.

Wiese, R. 1996. The Phonology of German. Oxford University Press.

Wurzel, W. U. 1980. “Der deutsche Wortakzent: Fakten – Regeln – Prinzipien. Ein Beitrag zu einer natürlichen Akzenttheorie,” Zeitschrift für Germanistik 3: 299–318.

Zonneveld, W. 1999. “Word stress in West-Germanic and North-Germanic Languages: Introduction.” In van der Hulst, (ed.): 476–478.

1

Getting Proto-Germanic stress: phonetics and historic accentology Anton Zimmerling Moscow State University of Humanities/Russian State University of Humanities

2

University of Stockholm FONOLOGIKOLLOKVIUM Tisdag, den 21 Oktober 2008.

3

Voicing of intervocal I.E. stops in Proto-Germanic: Indo-Eur.Proto-Ger. I.E. voiceless stops Ger. voiceless fгicatives P, T, K, K w F, Þ, X, X w Initial stress Ger. voiceless intervocal fricatives ÁTAA-Þ-A Non-initial stress Ger. voiced intervocal fricatives ATÁA-Ð-A Old I.E. non-final fricative s Ger. fricative z or its reflexes ASÁA-Z-A > ARA

4

A diachronic correspondence does not allow for postulating stress/absence of stress on a synchronic level. NB! I.E. *pətḗr is reflected in Gothic with a voiced fricative, Goth. fadar, and it is somehow connected with the placement of I.E. word accent, but one cannot establish, whether Gothic accent remained on the 2 nd syllable or not/ whether it changed its fonetic manefistation (tonal accent mixed dynamic accent).

5

I.E.. *s, *t in Germanic I.E. final and and penultimate *- s-, *-t- after unstressed vowels Germanic final fricatives *z, *đ ÁNISIANIZ>ANR I.E. final and penultimate *s,*t after stressed vowels Germanic fricatives *s, *þ ANÍSIANIS

6

Only two pairs of fricatives о.г. s/z, þ/đ, going back to I.E. *s, *t alternate in I.E. nominal and verbal endings: other fricatives do not occur in Germanic endings.

7

Verners Law in inlaut and auslaut Voicing of medial fricatives Voicing of final fricatives Set of fricativess: z, f: v, þ :đ, χ: γ, χu : gu (5 pairs) s: z, þ: đ (2 pairs) Presence of a subsequent vowel RelevantIrrelevant Presence of stressed syllable in a word form RelevantIrrelevant Prosodic domainWord form as a wholeUnstressed part of a word form: penultimate + final syllable final reduced vowel + + penultimate syllable Possible prosodic interpretations Voicing of the onset ot the stressed syllable absence of voicing of the finale of the stressed syllable Word-final weakening & Voicing in an unstressed environment General formula for both cases Absence of the devoicing of the final of the stressed syllable

8

Balto-Slavic accent paradigms and Germanic accent Germanic verbal stems with Holzmanns Law (Verschärfung) have Balto-Slavic cognates within the mobile a.p., while Germanic verbal stems with-*j/*w and without Holzmanns Law have Balto-Slavic cognates within the immobile a.p. and root stress.. а) Rus. доить, жевать, ковать, dial. бруить, сновать, травить, блевать, immediately verify the prediction, one stem is not represented, two verbs быть and плыть, have undergone accentual shift. б) Ger. сеять, веять, шить, (у)-спеть, баять, маяться, знать, греть.

9

Lexical meanings of Holzmanns verbs from the mobile a.p.

10

Lexical meaning of verbs from the immobile a.p.

11

Germanic oxytonese Germanic formsItalo-Celtic cognates with short vowels Balto-Slavic cognates with long vowels Goth. wair, O.I. verr, O.E., O.S., O.H.G. wer Lat. Vir, viri, Ir. Fer, Wal. Gwr (pl. gwyr), Bret. Gour Latv. Vĩrs, Lith. Výras, O.Pr. Wyras; cf. O.Ind. Vīrahman, Avest. vīra-hero; Umbr. Weiro-

12

13

Old Germanic Accent and word classes Initial stressNon-initial stress: РТ vs НТ Normal / late timing (NT) Tonal and dynamic peaks on the root syllable Tonal and dynamic peaks not earlier than of the post-root vowel (NT) Early timing (ET)The tone starts before the stressed vowel (ET)

14

Conclusions I: comparative studies 1) Free stress existed after the breakup of the Ger. Protolanguage. Germanic oxytona in most cases conform to the placement of the Balto- Slavic accent. 2) In word belonging to the mobile a.p., there were regular ties between tonics and posttonics. These ties were responsible for a number of fonetic and morphonologic processes. 3) The main position for accentological mutations was the onset of a non- initial stressed syllable in words from the Baltic-Slavic mobile a.p. Germanic oxytona: voiceless fricatives got voiced in this position, diphtongic glides -j,-w got lengthened. Consonant mutations prove for the relevance of free stress in Old Germanic languages. 4) Long-vocalic roots with post-root stress could ungergo vowel shortening. Cf. words with final sonorants: Goth. sǔnus sun, mǐmz meat, wǐndswind but O.Pr. сынъ, O.Gr. Μήρος, O.I. vā́tas wind, vā́nt prpl blowing), and -j, -w-, which are reflexes of I.E. long diphtongs.

15

Conclusion II: historic fonetics Word with Verners law and voicing of intervocal fricatives had early timing т.е. anticipating tonal movement before the stress vowels: this movement affected the onset of the tonic syllable. Anticipating tonal movement characteristic of ET also affected glides –j- и –w-, which led to their lenghening and resyllabofication: : *daj-΄an > *daj-΄jan. Where neither fonologically relevant pair of fonemes nor glides were present, ET did not trigger any changes in segmental fonetics. Lexical divergences of Old Germanic languages regarding Verners law, should be explained not in terms of stress fluctuation sensu strictu, but with the fact that different Ger. Languages could generalize either variants with ET or NT in words from the mobile a.p. Obsolete cases of Verners law in forms of one and the same word in one and the same language, may reflect not the retraction of stress, but coexisting variants with NT and ET. Cf. Goth. sais-lep ~ sai-zlep (VII class pret.), and words with an intervocalic cluster fricative + voiced + stressed vowel (Goth. fidwor, izwis, izwara).

16

References-I ДЫБО В.А Сокращение долгот в кельто-италийских языках и его значение для балто-славянской и индоевропейской акцентологии // Вопросы славянского языкознания. 5, 1961 г. ДЫБО В.А.1961a. Некоторые германо-славянские акцентологические параллели // Всесоюзная конференция по вопросам славяно- германского языкознания Минск 23–30 ноября 1961 г. ДЫБО В.А. Германское сокращение индоевропейских долгот, германский «Verschärfung» (закон Хольцмана) и балтославянская акцентология // Linguistica. Zagreb, DYBO, Vladimir A. Balto-Slavic Accentology and Winters Law // Studia Linguarum, 2, 2002, ЦИММЕРЛИНГ А.В. Раннегерманское ударение. Фонетика и компаративистика. // Лингвистическая полифония. Сб. в честь юбилея проф. Р.К.Потаповой. М., 2007, ZIMMERLING, ANTON. Accentological reconstruction and feasible fonetic features // Problemy izuchenija dalnego rodstva jazykov (k 55-letiju S.A.Starostina. RGGU, March 25-28, 2008).

17

References-II VERNER, Karl. Eine Ausnahme aus der ersten Lautverschiebung // KZ, 23 (1876), WOOD, Francis Asbury. Germanic Studies, 2. I. Verners Law in Gothic. Chicago. The University of Chicago Press THURNEYSEN, Rudolf. Spirantenwechsel im Gotischen// IF 8 (1898): JESPERSEN, Otto. Voiced and Voiceless Consonants in English // Linguistica Linguistica: Selected Papers in English, French, and German (by Otto Jespersen). Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard, 1933, HIRT, Hermann Grammatisches und Etymologisches // BGDGL 23: HIRT, Hermann. Indogermanische Grammatik. Heidelberg: Carl Winters Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1929.

18

References-III HOPTMAN, Ari E. Verners Law, Stress and the Accentuation of Old Germanic Poetry. A thesis submitted to the faculty of the graduate school of the university of Minnesota. University of Minnesota, LIBERMAN, Anatoly. The phonetic organization of Early Germanic // AJGLL 2 (1990), LÜHR, Rosemarie. Germanische Resonantengemination durch Laryngal // MSzS 35 (1976): MAŃCZAK, Witold. La restriction de la règle de Verner à la position médiane et le sort du s final en germanique// HS 103 (1990): SMOCZYŃSKY, Wojciech. Hiat laryngalny w językach bałto- słowiańskich. Kraków, Wydawnictwo Universyteti Jagiellońskiego, SUZUKI, Seiichi. Final Devoicing and Elimination of the Effects of Verners Law in Gothic // IF 99 (1994):

19

Acknowledgements The research was carried out with financial support of Russian Foundation of Humanities, project RGNF a