Non-native English speakers sometimes find it difficult to differentiate between the pronunciation of “teen” numbers (13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19) and “ten” numbers (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90). This can be confusing for both speakers and listeners.

Because these numbers sound similar, native English speakers use stress to differentiate them. Listen to the following sentences and see if you can figure out where the stress is.

Niles is 13 years old

I gained fifteen pounds my freshman year.

Their score was 18 at the end of the game

Click to learn the rule

Stress both syllables of “teen” numbers..

I rode my bike 60 miles yesterday.

My ninety-year-old grandmother goes dancing every weekend.

The weather forecast calls for a low temperature of 40.

Click to learn the rule

Stress the first syllable of “ten” numbers.

Xue moved to the United States when she was fourteen.

Gabriel will graduate in 2019.

Suji is getting married on May 16th.

Click to learn the rule

Stress the second syllable of “teen” numbers at the end of a phrase or sentence.

Listen to the following sentences and click on the box indicating whether you hear a “teen” number or a “ten” number. Then click on the link below to see the sentences and read each one out loud.

Practice 1

-

Click for the answer

Your total comes to $7.17.

-

Click for the answer

Mariko invited 50 people to her birthday party.

-

Click for the answer

Last night, Roberto wrote 40 pages of his novel.

-

Click for the answer

Derek’s paper had 16 citations.

-

Click for the answer

The art museum purchased 30 paintings last year.

-

Click for the answer

Did you take the stairs or ride the elevator up 13 flights?

-

Click for the answer

Many Americans get their driver’s license when they turn 16.

-

Click for the answer

Julie and her husband have been married for 19 years.

-

Click for the answer

There were eighteen seconds left on the countdown clock as I crossed the street

-

Click for the answer

I spent eighty dollars on my new textbook.

Practice 2

Listen to these sentences and repeat them; then, create your own sentences using important locations for you.

Nicole’s Fondue Shop is located at 19 West 15th Street.

Alex’s Cat Cafe can be found at 60 East 90th Street.

Carolyn’s Coffee Shop is at 14th Avenue and 40th St.

What do you do now?

You can practice saying your and your friends’ phone numbers and addresses, and practice verbally explaining quantitative problems or analyses.

-

#1

Dictionaries say numeral words from 13 to 19 have only one primary stress on the second syllable. But everytime I hear one of them, I feel like there was a secondary stress on the first syllable; and if there was, the word would be easier to pronounce. It’s not like words for numbers divisible by 10, I agree they only have one stress on the first syllable. What do you think?

Last edited: Feb 2, 2014

-

#2

The two syllables are stressed equally. There’s no primary stress and, hence, no secondary stress, either. As far as I know, this is called level stress.

-

#3

Hullo, Fumiko.

«But everytime I hear one of them, …«

It’s

quite possible. In fact these numbers in isolation have normally one stress on the second syllable (e.g. thir’teen, etc.), but when they’re accompanied by a Noun there’s a shift of the stress, which moves to the first syllable and becomes secondary, while the primary stress will fall on the following Noun: e.g. ,thirteen ‘people.

By the same token, a word like «Prin’cess», normally stressed on the second syllable», will see its stress moved to the first syllable in, e.g., «,Princess Di’ana».

GS

Last edited: Feb 2, 2014

-

#4

In fact these numbers in isolation have normally one stress on the second syllable (e.g. thir’teen, etc.)

…….a word like «Prin’cess», normally stressed on the second syllable

I disagree on both counts. The numbers are stressed on the first syllable, or (as Schimmelreiter said) have equal stress on both syllables. Princess is stressed on the first syllable.

-

#6

I agree with Gorgio too. I’d say:

He was born in thirteen-thirteen.

How old are you? Thirteen. Same stress pattern as in Berlin.

I’ve got thirteen apples.

She’s a princess.

Princess Anne is coming.

Perhaps it’s a BE/AE thing.

-

#7

I do as Giorgio does (post 3). In addition, if for some reason I needed to count aloud from one to twenty, I’d say thirteen,

four

teen, fifteen …. .

Last edited: Feb 2, 2014

-

#8

I don’t think there is much stress on the -teen. People often say, «Did you say thirteen or thirty?»1 It is the natural lack of stress on -teen that causes this confusion.

1 Also for the other numbers

-

#9

I agree with Gorgio too. I’d say:

He was born in thirteen-thirteen.

How old are you? Thirteen. Same stress pattern as in Berlin.

I’ve got thirteen apples.

She’s a princess.

Princess Anne is coming.

Perhaps it’s a BE/AE thing.

Having thought it over, with more time than I had available this morning, I agree with rhitagawr concerning numbers. However, I still say that

Prin

cess Anne (the

Prin

cess Royal) is a

prin

cess. (Do you say lion

ess

or tigr

ess

? I don’t.)

-

#10

RM1 and I speak the same language.

-

#11

Hullo, RM1.

Well, as for the two felines above , I suspect traditional RP (British English «Received Pronunciation») has both ‘lioness and lio’ness, whereas — strangely enough — it seems to have only ‘tigress.

GS

-

#12

I’d say the Princess Royal and tigress. I’d probably say lioness, although I wouldn’t think lioness was wrong. I’d say actress and manageress. There’s a lot of inconsistency — at least on the eastern side of the Atlantic. But we are talking about the English language, after all.

-

#13

There’s no need to get stressed out over this. Pronunciation, like much besides, depends on context.

Obviously, when you’re counting, you need to distinguish what’s different between consecutive numbers, so you stress the parts that are different: … fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, …

I think in most «neutral» contexts (I’m taking the Fifth and declining to specify exactly what that means) the syllables receive equal stress.

Sometimes poetry-like meter (even outside of poetry) demands a shift of stress, and I find rhita’s thirteen thirteen (for the year 1313) a very convincing illustration.

I don’t think I would ever say princess except in a context where it is necessary to distinguish her from her male counterpart.

When saying the title of the fairy tale, would you not all say «The Princess and the Pea«? But this is again probably more down to meter than anything else, as it would be when complementing a mother on how lovely her little girl looks: Isn’t she just a sweet little princess!You would never normally say actress either, always actress. But (true story): In junior high a teacher once asked a kid in my class who his favourite actor was, and he replied «Marilyn Monroe». The teacher was delighted at having caught the kid out on this technicality, and repeated the question, to which the same answer was given. Then the teacher pointed out that MM wasn’t an actor but an actress.

Stress for Numbers

Many non-native speakers of English have difficulty hearing and saying the differences between numbers such as 13 and 30. The solution is quite simple, and once you become aware of the rule, it is an easy error to fix. There are two important differences in the pronunciation: syllable stress and pronunciation of the letter t.

Syllable Stress

Every word in English has one stressed syllable that is said louder and held longer.

- thir in thirteen is the unstressed syllable. It is short and quick. thirTEEN

- thir in thirty is the stressed syllable. It is long and clear. THIRty

Pronunciation of t

The pronunciation of t is also tied to syllable stress in American English. Since the t in -teen is in a stressed syllable, it is pronounced clearly as /t/. Since the t in -ty is in an unstressed syllable, it’s pronounced /d/. You can think of it as thir-D, four-D, fif-D, six-D….

| Stress “teen” | Stress 1st syllable | Pronounced |

| ThirTEEN | THIRty | THIRdy |

| FourTEEN | FORty | FORdy |

| FifTEEN | FIFty | FIFdy |

| SixTEEN | SIXty | SIXdy |

| SevenTEEN | SEVenty | SEVendy |

| EighTEEN | EIGHty | EIGHdy |

| nineTEEN | NINEty | NINEdy |

Usually -teen is stressed. However, stress shifts to the first syllable:

- When counting: THIRteen, FOURteen, FIFteen

- When showing contrast: I have SEVenteen and he has FIFteen.

Can you hear and say the differences between –teen and –ty in sentences? Stress the correct syllable. Remember to say a /d/ instead of /t/.

- Put sixteen candles on the cake.

- We drove 60 miles yesterday.

- The bus leaves at 9:15.

- The book cost $9.50.

- She has fourteen cats.

- I live at 40 Katz Road.

Want to be more fluid, natural and secure in your speaking skills? Contact us to learn how.

What did you get for Christmas? Did Reza get a scarf, a pair of gloves, some socks and a wallet from his mum? Has Craig got his bathroom finished yet?

Gramática: 1st and 2nd conditional.

If you study hard, you will learn a lot of English (1st conditional – If + present simple + will)

Use the 1st conditional to talk about possible/probable things.

If you stick to your diet, you will lose weight.

If you don’t do exercise, you’ll put on weight.

Unless you do exercise, you’ll put on weight.

You will learn a lot if you listen to this podcast.

If you bought a lottery ticket, you would/might possible win. (2nd conditional) – If + past simple + would

If I win the lottery, I will (I’ll) travel around the world. (1st conditional)

if I won the lottery, I would (I’d) travel around the world (2nd conditional)

If I were/was Prime Minister, I’d lower taxes.

If Craig were Mickey Mouse he would go to the pub with Scooby Doo. Reza, on the other hand, would prefer to have a beer with Bugs Bunny.

Estudiar los condicionales en nuestro curso intermedio:

http://www.mansioningles.com/cursointer/cursointer11_5.htm

http://www.mansioningles.com/cursointer/cursointer15_5.htm

http://www.mansioningles.com/cursointer/cursointer16_6.htm

Pronunciación: Word stress in numbers:

14 – 40 – fourteen / forty

70 – 17 – seventy / seventeen

30 – 13 – thirty / thirteen

16 – 60 – sixteen / sixty

¡OJO! – Except when we’re counting! 13, 14, 15, 16 etc.

Phrasal verb: Put up

Many people put up Christmas decorations (montar)

I’m going to put up a couple of photos on the wall. (colgar)

Would you mind putting me up for the weekend? (hospedar, dar alojamiento)

The boxer lost the match but he put up a fight.

You can put up money for something – How much money did they put up to build the airport in Castellon?

Put up or shut up! Act or be quiet.

Put up something for sale on eBay.

We try to put up a new podcast episode every week.

Craig puts up with Reza’s Mickey Mouse comments (suportar, aguantar)

Craig has to put up with Reza every week!

Vocabulary Corner: New Year’s Resolution – Resolución de Año Nuevo

8% of people who MAKE New Year’s Resolutions actually KEEP them.

TOP TEN NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTIONS

The most popular resolutions are:

- lose weight – (put on weight) and do more exercise

- eat more healthily

- save money

- get a better job

- spend more time with family and friends

- travel more

- stop smoking and drinking (alcohol)

- get organised

- learn something new

- 10.Read more books

Are you going to make any New Year’s Resolutions this year?

Send us an email, or a sound file (mensaje de voz en mp3) to mansionteachers@yahoo.es and tell us.

Reza’s Top Tip: Self check spelling

accommodation

regrettable

unstoppable

which / witch (bruja)

Craig and Reza recommend Oxford and Collins dictionaries, and wordreference.com

The music in this podcast is by Pitx. The track is called See You Later – licensed by creative commons under a by-nc license at ccmixter.org.

Si quieres mandarnos un comentario sobre este podcast o una pregunta sobre el inglés, puedes ponerse en contacto con Reza a belfastreza@gmail.com y a con Craig a mansionteachers@yahoo.es.

FULL TRANSCRIPTION (kindly contributed by Patricia Alonso)

C: Hello and welcome to episode 11 of Aprender Inglés con Reza y Craig. Hello Reza!

R: Hi Craig and hi listeners! I hope you’re doing well.

C: And we hope you got fantastic presents for Christmas and you had a lovely Christmas holiday with your family. We’re actually recording this before Christmas but you’ll probably be listening to it, we hope, after Christmas. So, what do you think you got for Christmas, Reza?

R: I think I got a pair of gloves, as always, a scarf, socks and I hope I get a new wallet which I asked my mum for.

C: A new pair of sleepers perhaps? A new scarf?

R: That would be handy. What about you? What were you hoping for?

C: What I was hoping for? Emm… I wasn’t hoping for anything in particular.

R: A new bathroom? Has it been completed, I wonder?

C: I’m sure, as this episode is released, my bathroom will still be unfinished, I’m sure. I don’t think Father Christmas came and put my sink in my bathroom over Christmas, but who knows? Maybe in the new year, the bathroom will be finished and I will be able to wash my face in comfort.

R: Craig, when you were a kid did they tell you, it was a tradition to leave milk and cookies for Father Christmas, isn’t that right? Milk and biscuits or leave them a treat.

C: Yeah, the funny thing is we used to leave some milk and biscuits next to the fireplace but we had the fireplace closed with bricks and I always wondered when I was small how he got down the chimney, hoy Father Christmas came into the house to leave the presents when we’d close the fireplace.

R: Well, you know, to finish your bathroom off I think Father Christmas is gonna want a lot more than milk and cookies, he’ll probably want several hundred euros, I would imagine.

C: If he is anything like the Spanish builders we’ve employed, he’s gonna want a lot more than milk and cookies, let me tell you that. Reza, what are you going to speak about this episode in our grammar section, la gramática?

R: Well. Craig, two related points; the first conditional and the second conditional Shal I get cracking?

C: Go for it. First conditional and second conditional, if sentences, sentences with if…

R: That’s right, sentences with if. Well, you know Craig, a lot of people as you know make Ney Year’s resolutions, you’ll probably gonna talk about that later, right?

C: Mmm.

R: So, we could say, to get people an idea of preparing for the coming year, if you study hard and practise your English, you will learn a lot, if you study hard and practise you will learn a lot of English. That is called first conditional sentences.

C: First conditional.

R: First conditional. We have the word if followed by a conditional, if you study hard and practise, that’s the condition. So, for the consequence and result, you will learn English or you will learn a lot of English, you have future will plus the verb, that is for the consequence or result. So, just to recap, a first conditional sentence, the grammatical structure is this: if plus present simple, that’s the condition, if you study hard and practise, and then we have will with infinitive, you will learn a lot of English, that is for the consequence or result. And we use the first conditional to talk about things which are possible for the future. Maybe even probable, if you study hard and practise you will learn a lot of English, believe me.

C: If you listen to this podcast your English will improve.

R: It will, it is probable, it is a real possible, indeed, probable future consequence of listening, is improvement of your English. Let’s give you another example. Since it’s the new year and people want to change their lifestyle, if you stick to a diet you will lose weight, but the condition is you must stick to your diet, if you stick to your diet you’ll lose weight.

C: Are you saying then if I eat less chocolate I’ll lose weight?

R: You will, if everything else remains the same you will.

C: And if I do more exercise I’ll probably feel better.

R: You will, and if you don’t do exercise you will put on weight, you’ll gain weight. You can have negatives in first conditionals as well, if you don’t do exercise you will put on weight, or we could say unless you do exercise you will put on weight, unless means if not, if you don’t do exercise, unless you do exercise.

C: Si no.

R: Yeah, si no, you will lose weight, so unless equals if not.

C: Can I change the order? I can say I’ll put on weight if I don’t do exercise.

R: Exactly, and you can also say you will learn a lot if you listen to our podcast, so put the consequence before the condition. So, let’s say it can be A,B or B,A, the order, it doesn’t matter, as long as you get one thing right listeners, put if with the condition or unless the condition.

C: Because many Spanish speakers put will with the wrong clause, don’t they?

R: Exactly.

C: They say “if I will see you I’ll say hello”.

R: And that’s wrong. It’s gotta be if with the present simple, that’s the condition. If you study hard and practise, then for the consequence we have will, you will learn a lot of English.

C: If I win the lottery I’ll buy a new microphone.

R: Yeah, and you can reverse the order. I’ll buy a new microphone if I win the lottery, just reverse the order. That’s the first conditional.

C: But that’s if I buy a ticket, if I buy a lottery ticket there’s a possibility I win.

R: It’s a real possibility.

C: So, how can I express that if I don’t buy a lottery ticket and there’s no chance I’ll win.

R: Well, you could…

C: Is that the second conditional?

R: Exactly, you could use the second conditional. For example, we could say if you bought a lottery ticket, you would possibly win. If you bought, that’s the past simple, but we’re not talking about the past, we’re talking about un unreal or an unlikely situation. We use the past simple but we’re not taking about the past, we’re talking about in present or future time, if you bought a lottery ticket you would possibly win.

C: So, in Spanish you’d use el subjuntivo.

R: El subjuntivo. Si compararas la lotería, if you bought a lottery ticket, you would possibly win, ganarías posiblemente. We could also say if you bought a lottery ticket, you might win you can change the word would for might to how that the consequence is only possible but not certain. If you bought a lottery ticket you would possibly win or you might win.

C: So, let me see if I understand, so If I, with the example of the lottery ticket, if I win the lottery, I’ll travel around the world, first conditional.

R: Yeah.

C: I buy a ticket, if I won the lottery, I would travel around the world, subjuntivo, second conditional.

R: Second conditional, because it’s unlikely or improbable or completely unreal because you’re never gonna buy a lottery ticket so we’re only imagining. The second conditional is to imagine things. The first conditional, that’s with the present simple and will, is for a real possibility, maybe even a probability, but the second conditional, if you won the lottery, you would travel around the world, that is for something which is unlikely or improbable or even unreal because it’s not gonna happen because you never do the lottery.

C: So, if a politician would possibly say, if I win the elections I’ll lower taxes, but you would say or I would say, we’re not politicians, if I were prime minister I would lower taxes.

R: Exactly. We have to say if I were because it’s unreal because we can’t possibly be prime minister. Because we’re not gonna run an election, so we must use the second conditional to show that it’s unreal. In other words, the second conditional is for things which are more remote, more distant, more unreal, more imaginary, whereas a first conditional really could happen. The weird thing is for English speakers when we learn Spanish to find that in Spanish you have this subjunctive which we find very complicated, which you use in the second conditional. The subjunctive in Spanish I think tends to be used to show that things are unreal, unlikely, so…

C: I find that incredibly difficult, I have problems with the subjunctive.

R: We just use the past simple. Si compraras, if you bought, so if you bought a lottery ticket, you might win, podrías quizás ganar.

C: I’ve got a question, cause we used the example if I were prime minister I would lower taxes. Do you think it’s correct to say if I was? If I was prime minister?

R: Yes, that’s, in fact the listeners may be thinking why didn’t he say if I was? Was is the past simple of the verb to be. Yes, but in conditional sentences, second conditional sentences, when we use the past simple of the verb to be, it’s considered better English to say, rather than I was, to say I were, and rather than he/she/it was, he/she/it were.

C: Yeah.

R: But it’s also acceptable to say I was and he was, but it’s considered let’s say better English to say if I were prime minister or if he were prime minister.

C: If I were you…

R: I guess in English, technically speaking, that’s our subjunctive, the normal past simple, the indicative, el indicative, is, I was, but the subjunctive past, el subjuntivo, is I were, that’s really the English subjunctive. But you don’t need to think like that, just think of it as a special use of second conditionals, but really it’s the subjunctive. Craig, I have a question for you, if I bought you a drink…

C: I would be very happy.

R: Would you sing the Mickey Mouse tune? In a future podcast.

C: Jaja, if you bought me a drink or two, I would possibly sing the Missie, the Mickey Mouse song.

R: Not the MIssie or the Minnie Mouse, the Mickey Mouse…

C: On one conditional. Not the first conditional, not the second conditional, but on the condition you sing with me.

R: I would?

C: You would?

R: If you sang I would sing with you.

C: Let’s make a promise to our listeners that in 2014 to begin the new year we will sing live on this podcast the Mickey Mouse song.

R: But I will sing only if Craig sings, I’m not going to sing alone.

C: Have you heard me sing?

R: Mmmm…. No, I don’t think I have.

C: If you had (third conditional?)…

R: That’s a third conditional, oh, don’t confuse the listeners.

C: Next episode.

R: yes, third conditional is coming next episode, so don’t…

C: So, here’s a preview and a teaser, if you had heard me sing you wouldn’t have asked me to sing with you. We’ll study that in the next episode.

R: And tell me, Craig, just one more example to practise an unreal situation, something which cannot possibly be true, because it’s unreal, second conditional. Craig, if you were Mickey Mouse, which cartoon character would you hang out with? Who would you spend time with? Imagine, if you were Mickey Mouse, who would you hang out with? Donald Duck, Goofy, Pluto… who?

C: Possibly Goofy, I’ve always had a soft spot, I’ve always liked Goofy, but I think if I had to chose I would hang out and go to a pub and have a beer with Scooby Doo.

R: Oh yes? Why not?

C: Which is another one of my favourite songs.

R: Scooby dooby… No, save it for the next podcast.

C: Save it for the next podcast.

R: Ok, listeners, so you get the message, Craig, although he would love to be Mickey Mouse, he isn’t Mickey Mouse, it’s not real, so we have to say if you were Mickey Mouse, si fueras, el ratón Mickey, which cartoon character would you hang out with, con qué otro personaje del mundo de la animación pasarías tiempo.

C: Throw the same question back to you, Reza, if you were Mickey Mouse who would you hang out with? Which cartoon character would you have a drink with?

R: Well, I should, not would eh? I should, debería, I should only have a drink with Minnie Mouse who would be my wife.

C: Yeah, but you know, you go to the pub, you wanna hang out with a male, you wanna talk football, maybe sex, who would you go with?

R: Errr.. Bugs Bunny I think.

C: Bugs Bunny.

R: Yeah, I would have a drink with Bugs Bunny. Just Bugs Bunny or my wife Minnie Mouse.

C: I’m all ears…

C: Moving on to the pronunciation section on the episode, and this episode I’d like to speak about word stress in numbers. Last episode we spoke about word stress in words and I’d like you to write down on a piece of paper the following two numbers. Ready? Fourteen, forty. Now I hope that you wrote in this order catorce, cuarenta. But sometimes it’s difficult to know the difference between the number “teens” (fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen) and numbers in the “tens” (forty, fifty, sixty, seventy). The way to distinguish, the way to know, la forma de saber, is the stress. Usually, the lower number, the number in the teens, fourteen, has the stress on the second syllable, so it would be de DA, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, etc. The numbers in the tens, forty, fifty, sixty, seventy, have the stress on the first syllable, so it would be DA de, forty, fifty, sixty, etc. OJO, when we are counting numbers, the stress changes, so listen, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, the stress has changed to the first syllable, but numbers in isolation, “How old is your daughter? She’s fourteen”, the stress is on the second syllable for numbers in the teens.

R: Craig, do you often ask people how old their daughters are?

C: No, jaja.

R: You’d better be careful, you might well receive a punch as the answer.

C: I used to, but now I ask them how old their grandmothers are, jaja.

C: Moving on to our phrasal verb, put up.

R: Put up. Listeners, I imagine that quite a few of you put up Christmas decorations, didn’t you? Did you put up a Christmas tree, with little stars on it, maybe an angel at the top, little balls and Father Christmases and things like that? So, to put up Christmas decorations means to put up, to erect, to hang up.

C: ¿Montar? Like a Christmas tree?

R: Perhaps, montar. It could also be colgar, as well.

C: Because you can put up photos on the wall, put up pictures.

R: Exactly, put up on display, so that people see. For example, in the Soviet Union, in the USSR, they put up many statues of Lenin, they put up many statues, they erected.

Another meaning for put up is for accommodation, for example, Craig, you who are having your bathroom renovated at the minute, do you remember when I was having my bathroom renovated and you put me up for a few days?

C: Yeah, I put you up in the flat, you stayed here a couple of days, I gave you a bed, I fed you, I put you up.

R: He gave me accommodation, he put me up.

C: ¿Hospedar?

R: Put me up, yeah. It generally means for free, so you don’t say that a hotel puts you up, you pay to stay in a hotel, it’s when you go to a friend’s house or a charity, or something like that and they offer you accommodation, that’s put up.

C: Can you put me up next weekend?

R: Sure, I can.

C: Good.

R: You might need to come with your bathroom renovation, right?

C: Exactly.

R: Ok, another meaning of put up is to put up a fight, put up a struggle, for example “The boxer lost the match, but he was very brave, he put up a fight, he tried, he put up a fight, he put up a struggle. A struggle is STRUGGLE, una lucha, luchó.

Another use of put up it to put up money. To put up money is to contribute money for a specific purpose, for example imagine they want to build a new airport, it’s gonna costa a lot of money, so the government are gonna put up some money but then the banks will have to put up the rest, to contribute money for a specific purpose.

C: I wonder how much money they put up to build the airport in Castellón for not being used.

R: Castellón, the airport with no flights! I would like to work there as an air traffic controller (jaja). They earn a lot of money and it doesn’t matter how many flights there are, sorry, it doesn’t matter how many flights they have. Can you imagine, air traffic controller in Castellón, I would watch Mickey Mouse cartoons all day.

Ok, another meaning of put up is a fixed expression: to put up or shut up.

C: Put up or shut up.

R: What does that mean to you Craig? To put up or shut up.

C: Mmm… Hazlo o collate.

R: Exactly, great translation. In other words, act or be quiet, do something or don’t speak, put up or shut up.

C: Take action or don’t do anything or don’t speak.

R: Exactly, so shut up means cerrar el pico.

And, another couple of meanings. To put something up for sale, on the internet, these days people often put up things on ebay, they put them up for sale.

C: That’s right.

R: They put them up for sale. That means you publicly announce or make it known that you want to sell something. A more traditional way is at an auction. Auction is when people say: “So who will buy this Picasso painting? Do I have 500.000? 500.000. 600? 600.000. This gentleman 700.000, anymore? 800.000, sold for 800.000”. You can put things up at an auction. Ebay is really an auction but it’s an auction on the internet.

C: So, I suppose I could say that every week or every ten days we put up a new episode of this podcast.

R: Exactly, to put up, to make something public, to make it publicly available, we put up an episode, yeah. Craig, I have one more point of putting up, it’s a question for you, at the last minute, or put up.

C: Go ahead.

R: Are you going to put up with my comments about Mickey Mouse this year?

C: But that’s put up with.

R: Ah, very observant, yes, slightly different. If we add the preposition with, to put up with means aguantar. Are you going to tolerate, are you going to soportar, are you going to put up with my comments or are you going to crack and get really angry?

C: Well, I think I’m going to have to put with your comments about Mickey Mouse because let’s face it Reza, I put up with you every episode.

R: That is true, that’s true.

C: Moving on to our vocabulary corner, and because it’s New Year 2014, I thought it would be suitable to speak about New Year’s resolutions, resolución del año nuevo, you know, when the new year comes around, when the new year appears, we like to promise ourselves we are going to change, we’re going to do things better, we’re going to improve our situation, so I have a top ten of the most popular resolutions, Reza, and I’d like you to try to guess without looking at my paper, see how many of these ten popular resolutions you can guess that people make. Now, bear in mind, remember 8% of people who make resolutions actually keep them, so these are resolutions that people popularly make, often make, but only 8% of these are actually kept.

R: 8%, that’s not much, is it?

C: It’s not much, is it? And every year we do the same. So, what do you think? Have a guess of some of these resolutions.

R: So top ten, this is worldwide yeah?

C: Worldwide.

R: Ok, let’s see, go on a diet, that’s gonna be in the top ten.

C: That’s number one, lose weight is number one.

R: Mmmm… stop drinking alcohol?

C: That’s number seven, along with stop smoking, stops smoking, stop drinking alcohol, good, that’s two, you got two so far.

R: Do more exercise?

C: That’s again with number one, lose weight, do more exercise, good.

R: I don’t know here if it’s on the list Craig, but I think our listeners should put as number one study and practise more English, is it on the list?

C: I agree, it’s not on the list but I think it should be, especially for our audience.

R: Should be number one. What else is on the list, Craig?

C: I’ll tell you, number one is losing weight and do more exercise, number two eat more healthily, change your diet, healthy food.

R: Would that exclude dulce de leche?

C: Mmmm… Everything’s ok with moderation, if you take dulce de leche of your life you really aren’t gonna be happy, are you?

R: Un poquito.

C: Un poquito de dulce de leche. Number three is save money, saving money is another resolution. Get a better job number four, improve your job situation. Spend more time with family and friends number five, travel more number six, stop smoking and drinking, you correctly guessed, and number eight get organised, organise your life, organise your work, organise everything, and number nine learn something new, which could be your suggestion to improve your English. And number ten read more books, possibly in English, but just read more. So, those are the ten most popular resolutions. Are you gonna make any resolutions this year? Do you usually make them?

R: Well, I have one resolution which I’ve had for many years and it’s on this list, Craig. For me can you guess what’s number one? Craig, if, let me ask you a question.

C: Get a better job.

R: If you could choose, which would you choose as your number one resolution of this ten? That’s a second conditional by the way, listeners.

C: If I could choose one, I would choose get organised, I’m not happy with the way I organise my work, my life, so I probably try to get organised in 2014.

R: Well, for me the most important thing is learn something new.

C: What would you learn?

R: I don’t know, but something new. The dulce de leche recipe, I don’t know.

C: We’ll ask you in the new year if you’d made that resolution.

C: Do you have a tip for us today, Reza?

R: Yes, just a quick tip this week. The tip is, every once in a while, check yourself for spelling.

C: Self-check yourself… How would you do that?

R: Well, think of words which you find difficult to spell, classics, that means los típicos, err… accommodation.

C: Double c, double m?

R: Double c, double m, some people write double c, one m, some people double m, on c… Double c, double m, accommodation. Other ones are for example regrettable, is one t, double t? Tell me.

C: One t.

R: Double t.

C: Is it double t? Jaja.

R: Unstoppable, one t, one p or double p, unstoppable?

C: My students have problems with which, not bruja, the other which, they always forget the h.

R: Exactly, you should compare them, so that was, you took the words out of my mouth, the next thing I was gonnna say is write words which sound similar, in fact, they may even sound exactly the same. They may be homophones, like which and witch. The first which is pronoun and the second witch is bruja, and see if you can spell them correctly.

C: And the trick with bruja is that is the hat of witch.

R: That’s a good way to remember yeah, that’s a good way to remember. So, tricky words, words which you know you have difficulty with, don’t pick easy words because then there’s no point, words which you know are hard for you or hard in general. Write them down and then later go to the dictionary and check your spelling. Use a good dictionary, be very careful about some dictionaries online, they can’t all be trusted.

C: Let me put you on the spot and ask you a recommendation for a paper dictionary and an online dictionary.

R: Well, paper dictionary Oxford is good, Collins is not bad either.

C: I like Colllins, I use Collins English-Spanish, yeah.

R: Yeah. Cambridge also. My personal reference is Oxford and no, listeners, honestly we do not get money, we really should start charging these companies.

C: We should, shouldn’t we? We should get commission for this.

R: And online, well, it depends if you’re prepared to pay or not.

C: Yeah, well, let’s say not paying because I’m a cheapskate, I like to save my money.

R: Cheapskate listeners is un rácano, un tacaño. Me too, so I would never buy one online. I have some free CDs but normally you have to buy the paper dictionary to get the CD anyway. But, online free I would say wordreference.

C: I was hoping you to say that because I use wordreference.com every single day when I’m writing material and I find it very good, very useful and almost always correct. Wordreference.com.

R: Well, that’s my tip for today, be careful with spelling.

C: Thank you very much and thank you all of you who have listened to this episode. Remember if you want to contact us you can send us an email or a sound file, un fichero de sonido con tu voz en mp3, an mp3 file attached to an email and send your comments and your questions to mansionteachers@yahoo.es.

And if you’re making any New Years resolutions send us your resolutions and we will speak about them on the episode.

Thanks you for listening, thank you to Reza and we’ll see you next episode.

R: Have a great 2014, bye bye!

C: Happy New Year!

By Shirley Jones

Why is it easy to understand the difference between 13 and 30 when you read them, but it’s difficult when you hear them?

How often do you ask ‘is that three zero, or one three?’ Or ‘just send me an email’?

Have you noticed that in English some things about numbers are very different compared to your language? For example, how you say large numbers, or prices, or dates?

If you’re like the people I teach, you’ve probably had similar problems, no matter what your level of English.

This article will explain the biggest problems with using and understanding numbers in English, and how you can avoid and correct them.

So why do numbers matter?

Numbers are an essential part of our lives – negotiating a price, checking dates and times for a meeting, writing down a telephone number – just to mention a few examples.

It’s not hard to imagine how situations like these could lead to disaster…

You arrive late at the airport to hear the final announcement for your flight

“Would remaining passengers please report immediately to gate fifteen” (15)

You understand fifty (50) and you miss your flight.

You see a handbag for $10,000 and think you are getting an amazing bargain for $10.00. There will be a nasty shock when the credit card bill arrives!

You are invited to a party on 2/3. You arrive a month late.

Was that February, 3rd (month, day) or the 2nd of March (day, month)?

You should have checked if your host was American or British!

Hopefully you have never been in any of these situations. But how did they happen?

The 5 problems

Learners typically have 5 main difficulties with numbers in English:

- Pronouncing and understanding spoken numbers

- How to use the thousand separator and the decimal point

- Where to say ‘and’ in numbers

- Saying decimals and prices correctly

- The date

Now let’s look at each topic, so you will understand and eliminate each problem.

—

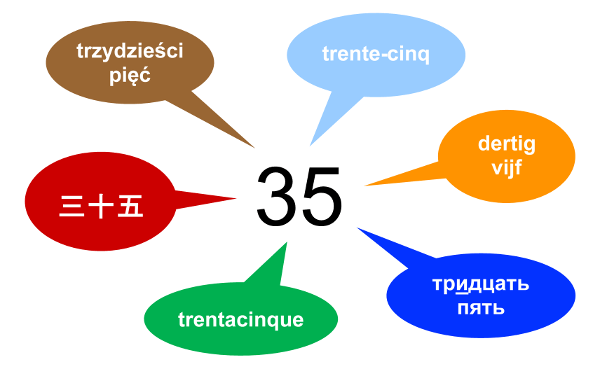

Part 1: Saying and understanding spoken numbers

The first difficulty we all experience when learning numbers in a foreign language is to make a visual link between the number and the sounds we hear in words.

When we are growing up, our brains connect the sounds of our native language with numeric symbols such as 1, 2, 3, etc. It can be very difficult to link familiar numeric symbols with unfamiliar words, particularly when the individual sounds do not exist in your own language.

Let’s try a quick test with two numbers you might find particularly difficult to distinguish between – 40 and 30. Can you hear the difference?

https://blog.tjtaylor.net/content/uploads/How-to-pronounce-forty.mp3

https://blog.tjtaylor.net/content/uploads/How-to-pronounce-thirty.mp3

Many people find it difficult to hear the difference between these two numbers. Let me explain why.

Sounds ‘aw’ and ‘er’

Try to make these two sounds. Pay special attention to the shape of your mouth and the position of your lips

‘aw’ like…

|

horse |

‘er’ like…

|

bird |

In some languages (for example Italian) these two sounds don’t exist, and so it is difficult to distinguish between them.

Now let’s look again at those two numbers. Do you notice what they have in common with horse and bird? That’s right – they contain the same sounds.

and

Say these two numbers aloud a few times and focus on hearing the difference.

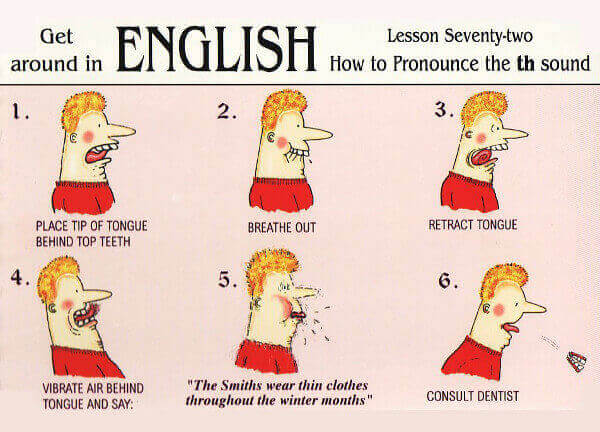

Was that ‘t’, ‘f’ or ‘th’?

Hearing the difference between these 3 sounds can be hard for non-native English speakers:

This is particularly true for the sound ‘th’, because it might not exist in your language.

Now let’s have a look at some numbers with the same sounds:

| 10 | ten | |

| 4 | four | |

| 3 | three (not tree or free) |

Learners often pronounce three, thirteen, thirty, thousand in the same way as ten – with a ‘t’ or an ‘f’ sound at the beginning instead of a ‘th’ sound.

Now that you have practised the sounds ‘aw’, ‘th’ and ‘er’, listen again to those two numbers:

https://blog.tjtaylor.net/content/uploads/How-to-pronounce-forty.mp3

https://blog.tjtaylor.net/content/uploads/How-to-pronounce-thirty.mp3

Is it easier now to hear the difference between forty (40) and thirty (30)?

Stress!

You should not be stressed about numbers in English – but you do need to know where to put the stress.

In a word that has two or more syllables, one syllable always has more emphasis or stress. Here are a couple of examples:

| ■ □ | □ ■ | |

| STUdent NUMber |

PreFER PerCENT |

Now look at these pairs of numbers:

| ■ □ | □ ■ | |

| 30 THIRty 40 FORty |

13 thirTEEN 14 fourTEEN |

As you can see, where you put the stress communicates a lot of meaning.

Tip: make a note of the numbers or pairs of numbers that you find difficult e.g. 40 vs. 30, 15 vs. 50, 6 vs. 7. Do they have sounds that don’t exist in your language?

A very good way to improve your listening skills is to ask your teacher or another proficient English speaker to dictate some numbers to you. e.g. telephone numbers, street addresses, credit card numbers etc.

—

Part 2: Thousand separator vs. decimal point

How do you say this price?

$10,000

If you said ten dollars, don’t worry – it’s a very common mistake!

The correct answer is ten thousand dollars.

The correct way to write ten dollars is like this:

$10.00

The confusion is caused by the thousand separator (,) and the decimal point (.) which are used in the opposite way in many languages.

Thousand separator

To make numbers easier to read, numbers can be divided into groups using a ‘thousand separator’. The thousand separator is used to separate groups of hundreds, thousands and millions.

In English-speaking countries, a comma (,) is used:

1,000 one thousand

10,000 ten thousand

100,000 one hundred thousand

1,000,000 one million

1,000,000,000 one billion

In other languages, a comma (in Italian for example) or a space (in French for example) is used:

1.000 or 1 000

Decimal point

A decimal point separates the whole number on the left from the part on the right that is less than 1.

In English-speaking countries, the decimal is represented with the symbol (.)

1.5 one point five

10.7 ten point seven

In other countries, the decimal point is represented with a comma (,)

1,5

10,7

Point, dot, full-stop or period?

They all use the symbol (.) but the word you use depends on the situation.

We use point for numbers:

15.2 fifteen point two

But the same symbol changes name when it is used with letters and is called dot. For example, with email addresses or website addresses:

[email protected] = jane dot doe at xyzcorp dot com

xyzcorp.com = xyzcorp dot com

When it is used at the end of a sentence it is called a full-stop (British English) or a period (American English).

Tip: if you work or study in an international environment, it is very important to check the standard format used for numbers. For example, if you work for an American company in Milan, company documents will probably use the English-speaking format. Computer programs, for example Microsoft Excel, automatically format numbers according to the regional settings of your computer, which you can adjust under ‘system preferences’.

—

Part 3: ‘And’ in numbers

Have you ever felt confused about where to say AND in numbers? You are most certainly not alone!

1 , 0 0 0 thousands

1 0 0 hundreds

▼1 0 tens

1 units

▼ where to say ‘and’

There are 3 important points you should know about AND in numbers:

- AND is only used in numbers above 100:

1▼10 one hundred AND ten

- AND is used after the first digit in every group of 3 numbers (hundreds) that contain tens or units:

1▼55 one hundred AND fifty-five

3▼01 three hundred AND one - For large numbers, say AND in every group of 3 numbers after the first digit. Don’t say ‘and’ to represent the thousand separator:

1,5▼50 one thousand five hundred AND fifty

1,5▼05 one thousand five hundred AND five

7▼26,9▼03 seven hundred AND twenty-six thousand, nine hundred AND three

2,9▼02,3▼47 two million, nine hundred AND two thousand, three hundred AND forty-seven

Now look at these numbers. What do you notice?

1,500 one thousand, five hundred

700,100 seven hundred thousand, one hundred

There is no AND! Do you know why?

It’s because these numbers have no tens or units. Also, don’t say ‘and’ for the thousand separator.

Tip: remember that AND is used in every group of three numbers that contains tens or units. To help you visualise this, AND is a link between the hundreds and the tens or units.

You might occasionally hear native speakers omitting AND in numbers. However, to many people, it sounds wrong. The correct use of AND in numbers is an international standard.

—

Part 4: Saying prices and decimals

Probably the most difficult area for my students to get right is to distinguish between decimals and prices.

12.673% (a decimal)

$35.67 (a price)

The first thing to know – prices are decimals.

First we’ll look at decimals and then prices.

As we have already seen, the decimal point (.) separates the whole number on the left from the part on the right that is less than 1.

However, there are some important differences between the way we say a decimal and the way we say a price.

Decimals

First, let’s take a look at decimals. How would you say this number?

12.673

a. twelve point six hundred and seventy-three

b. twelve and six hundred and seventy-three

c. twelve point six seven three

d. twelve dot six hundred and seventy-three

If you chose a, b, or d – you would be making a very common mistake, but the correct answer is c.

To read decimals correctly follow these steps:

| 1. Say the complete number before the decimal point | twelve |

| 2. For the decimal, say ‘point’ (not ‘dot’) | point |

| 3. Read the number on the right after the decimal point as single digits (not six hundred and seventy-three) | six seven three |

| 4. If you need to say what you are measuring, say it at the end, e.g. %, ml, kg, etc. |

Prices

Now try this price:

$35.67

Do you say:

a. thirty-five dollar and sixty-seven cent

b. thirty-five dollars point sixty-seven cents

c. dollar thirty-five six seven cents

d. thirty-five dollars sixty-seven

If you chose answer d. congratulations!

If not, don’t worry, let’s break it down into steps and try again.

Follow these 4 steps to say a price correctly in English:

| 1. Say the complete number on the left before the decimal point | thirty-five |

| 2. Next, say the currency. If more than 1, the currency is usually plural | dollarS |

| 3. Don’t say the decimal point. Don’t say ‘and’ | |

| 4. Say the complete number on the right after the decimal (this is different from a normal decimal number). You don’t need to say cents or pence, etc. | sixty-seven |

Let’s try another price…

€146.90

| 1. Say the complete number on the left before the decimal point | one hundred AND forty six |

| 2. Next, say the currency | euroS |

| 3. Don’t say the decimal point. Don’t say ‘and’ | |

| 4. Say the complete number on the right after the decimal | ninety |

Simplified numbers

In presentations and news reports, instead of a number like this: $35,643,782 you will often see it written like this:

$35.6 m (thirty-five point six million dollars)

When an exact number is not necessary, we can simplify it or round it to 2 or 3 significant numbers.

Do you notice something about this simplified number?

$35.6 m

The thousand separator (,) in the long number has become a decimal (.) in the simplified number.

We also say the currency at the end.

Thirty-five point six million dollars

This is because .6m represents part of the whole number and is not a decimal (the part that is less than 1).

Review

Make sure you understand the 6 key differences between the way we read decimals and prices:

- For decimals, say ‘point’. For prices say nothing. Never say ‘and’ to represent the decimal:

3.5 three point five

£3.50 three pounds fifty - For decimals, say complete numbers before the decimal point (.) and single numbers after. For prices, say complete numbers both before and after the decimal:

42.655 forty-two point six five five

$42.65 forty-two dollars sixty five - For decimals, we say what we are measuring at the end. For prices, we say the currency after the first number:

42.6% forty-two point six percent

$42.65 forty-two dollars sixty five - For prices, if the number before the (.) is more than 1, the currency is usually plural:

$5.50 five dollarS fifty.

But note, some currencies are never plural e.g. Yen, Rand, Real, Pence

- Remember the difference between the thousand separator (,) and the decimal point(.)

- …and finally, don’t forget when you need to say AND in the numbers.

That’s a lot to remember – so let’s try a quick quiz (with answers!) to review the key points about prices, decimals and simplified numbers.

How do you read these numbers?

- $78.40

- €399.60

- ¥10,000

- $6,152.75

- $142,523

- 89.223%

- €678.8 m

(And here are the answers: 1. seventy-eight dollars forty 2. three hundred AND ninety-nine euros sixty 3. ten thousand yen 4. six thousand one hundred AND fifty-two dollars seventy-five 5. one hundred AND forty-two thousand, five hundred AND twenty-three dollars 6. eighty-nine point two two three percent 7. six hundred AND seventy-eight point eight million euros)

—

Part 5: The date

The problems with dates in English is not only that we say and write them differently, but the way we say and write them also depends on where we are in the world!

Days and dates

Do you know the difference between cardinal and ordinal numbers?

Cardinal numbers show quantity, whereas ordinal numbers show the position in a series:

| There are three boxes | □ □ □ | |

| The first box is black | ■ □ □ |

So what does this have to do with dates?

In many languages, cardinal numbers (1, 2, 3) are used for dates. In English, we use ordinal numbers (first, second, third):

His birthday is on the 3rd (third) of September

not

3 (three) September

The first three ordinal numbers have special names:

1 – First

2 – Second

3 – Third

For all other ordinal numbers, we add a ‘th‘ sound:

4 – Fourth

6 – Sixth

For multiples of ten (20, 30, etc.), we remove y and add -ieth:

20 – Twenty = Twentieth

30 – Thirty = Thirtieth

Remember after 20, we say:

22 – twenty second, not twenty-twoth!

Years

In English, we normally read years in pairs of numbers. Do not say ‘and’. For zero, we often say ‘oh’ (like the letter O):

| 1987 | Nineteen | eighty-seven |

| 1709 | Seventeen | oh-nine |

| 1800 | Eighteen | hundred |

We don’t usually read years in thousands (unlike many other languages).

The exception (in English there’s always an exception!) is the years after the millennium to 2009. When the year is read in thousands, include AND:

| 2000 | Two thousand |

| 2002 | Two thousand AND two |

However, from 2010 onwards, most people return to pairs of numbers:

American or British?

Imagine you receive an email from abroad. “Let’s meet 5/6/19”.

You might wonder – is that the 5th of June or the 6th of May? An important question, I am sure you would agree.

Well, the answer depends on who you are talking to.

Your American friend says the month and then the day, so 5/6 is May, 6th.

On the other hand your British friend says the day and then the month, so 5/6 is 5th of June.

You may see the date written in the following ways:

American format:

September, 3 2018

September, 3rd 2018

09/03/2018

British format:

3 September 2018

3rd September 2018

03/09/2018

Now, let’s try a quiz! How would you say these dates?

- 25/11/18 (British Format)

- 03/02/16 (American Format)

- 04/05/02 (British format)

- 04/05/10 (American format)

And the answers:

- The twenty-fifth of November, twenty eighteen

- March the second, twenty sixteen

- The fourth of May, two thousand AND two

- April the fifth, twenty ten.

Tip: always check that you’ve understood the date correctly.

For example:

Alex: So that meeting is on 2/3 – you mean the 2nd of March, right?

Jo: No – February the 3rd.

Alex: Phew, I am VERY glad I checked!

—

In summary

So those are the 5 most common problems with numbers in English. Here is a summary of the most important pitfalls to avoid:

- Focus on the sounds in numbers that don’t exist in your own language (e.g. ‘aw’, ‘er’ and ‘th’). Practise them regularly until you get them right.

- Understand the importance of word stress. With numbers, the position of the stress can sometimes completely change the meaning of the word.

- Are the thousand separator (,) and the decimal point (.) used differently in your language?

- Learn where to say AND in numbers.

- Note the different ways we read prices and decimals.

- Remember to use ordinal numbers for dates.

- Always check if the date is in American format (month, day) or British format (day, month).

Conclusion

The key to confidence with numbers in English is to practise using them as often as possible.

Make a note of the numbers you find particularly difficult, and practise saying them with your teacher or another proficient English speaker. After a few weeks, you will notice a difference.

In some situations, a number may be the most important part of your conversation – for example a date, a time, a telephone number, a price. If you are unsure, it’s always a good idea to repeat back to check you’ve understood correctly, or even write it down.

Have you had any problems with numbers in English? Which numbers cause you the most problems? Was there anything in the article that you need explained more?

Let us know in the comments below!

Cardinal and ordinal numbers in English

You might think that it makes no sense to study numerals in English. Indeed, it is easier to write the necessary numbers on a piece of paper and just show them to an English-speaking friend (and to any other friend who passed the numbers at school).

But what to do if a situation arises when there is no piece of paper at hand or there is no way at all to draw something on the sand / napkin / other surfaces. For example, when you speak to a business partner on the phone or call the automated call center at London Airport.

And in general, knowledge of numbers in English will not be superfluous.

You didn’t think, when you learned the English alphabet, about its need, but you took it for granted. Moreover, this process is simple and interesting.

Numbers in English (quantitative numerators)

• What is easiest to memorize? Rhymed poetry. The British seem to have specially invented numbers that are easy to rhyme. Meaning quantitative numerals. That is, those with which you can count objects. We take numbers from 1 to 12 and memorize simple rhymes:

One, two, three, four, five, six, seven,

Eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve.

We repeat this mantra 10 times and consider that the first stage has been passed.

• The second step is to learn the cardinal numbers from 13 to 19. If we were talking about a person’s age, then many would call people from 13 to 19 years old teenagers. And it is no coincidence. It’s just that at the end of each of these numbers there is the same ending. —teen… And here is the confirmation:

thirteen

fourteen

fifteen

sixteen

seventeen

eighteen

nineteen

• Let’s go further? We take dozens. They are very similar to the numbers 13 through 19, but they have an important difference. Instead of a teenage ending, we add –Ty.

Twenty

thirty

forty

fifty

sixty

seventy

eighty

ninety

• Do you think it will be more difficult further? Don’t even hope. How do we speak Russian 21? The same in English:

twenty one

Fine, fine. Have noticed. Yes, a hyphen is placed between ten and one. But otherwise, everything is the same. Take a look:

Thirty-four, fifty-seven, eighty-two.

• Let’s not waste time on trifles. And let’s move on to more impressive numbers.

Hundred — 100

Thousand — 1000

Million — 1000000

If this is not enough for us, then we can make 200 (two hundred) or 3000 (three thousand), or even immediately 5000000 (five million).

It is surprising that the British did not complicate anything here. Note that a hundred, a thousand, a million are not plural. Everything is in one.

• Still, let’s try something more complicated. Let’s look at composite numbers. For example, 387. We place bets, gentlemen, who will pronounce this number how? And now the correct answer is:

three hundred AND eighty-seven.

The only difference from the Russian is the appearance of the union “and” between hundreds and tens.

What about 5234? We place our bets again. Correct answer:

Five thousand two hundred and thirty-four.

Ordinal numerators

• Cardinal numbers did a good job as a warm-up. It’s time to move on to ordinal in English. That is, to those numerals that denote the order of objects: first, second, third twenty-fourth, the calculation is over!

And here one little surprise awaits us. All ordinal numbers are obtained in the same way: the article is simply added to them the front and —th at the end of a word. And all the cases.

the fourth

the fifth

the sixth

the seventh

the eighth

the ninth

tenth

the forty-seventh

But English wouldn’t be so interesting if it weren’t for the exceptions to the rule. And, of course, these exceptions are the most commonly used numerals.

the first

second

the third

Who has not guessed yet, this is the very first, second and third.

• For dessert. A little more theory for the most curious. This is no longer as necessary as knowledge of cardinal and ordinal numbers, but it will help you show yourself to be very educated in the environment of English-speaking interlocutors.

Phone number. How do you say in Russian 155-28-43? Yeah: one hundred fifty five, twenty eight, forty three. And in English you will call each number in turn. And a little nuance: when there are 2 identical digits in a row, you need to say double and name the number. In this example: one double five two eight four three.

Year. For example, 1843. In Russian: one thousand eight hundred and forty-third. That is, as a number, and even ordinal. And the British are not bastard. Their years are pronounced in dozens at once: eighteen forty-three. That is, also numbers, but quantitative, without any –Th.

Rooms.

Source: https://iloveenglish.ru/theory/anglijskaya_grammatika/chislitelnie_kolichestvennie_i_poryadkovie

Lesson 5. Numbers in English

Daria SorokinaLinguist-translator, teacher of foreign languages.

In English, as in Russian, there are two types of numerals: quantitative and ordinal. Quantitative are those that answer the question How much? and ordinal — to questions what?which? which? which?

Cardinal numbers

The numbers from 1 to 12 need to be memorized and known very well, but then it will be easier for you, because when forming two-digit numbers, there are already hint rules that will help you to facilitate the formation of numbers.

Take a close look at the table with numbers and try to find the common in the formation of round numbers. In the note, you will be shown the very tips that we talked about above.

0 — oh or zero [ou], [‘zɪərəu]

1 — one [wʌn]

2 — two [tuː]

3 — three [θriː]

4 — four [fɔː]

5 — five [faɪv]

6 — six [sɪks]

7 — seven [‘sev (ə) n]

8 — eight [eɪt]

9 — nine [naɪn]

10 — ten [ten]

11 — eleven [ɪ’lev (ə) n]

12 — twelve [twelv]

13 — thirteen [θɜː’tiːn]

14 — fourteen [ˌfɔː’tiːn]

15 — fifteen [ˌfɪf’tiːn]

16 — sixteen [ˌsɪk’stiːn]

17 — seventeen [ˌsev (ə) n’tiːn]

18 — eighteen [ˌeɪ’tiːn]

19 — nineteen [ˌnaɪn’tiːn]

20 — twenty [‘twentɪ]

21 — twenty-one [ˌtwentɪ’wʌn]

30 — thirty [‘θɜːtɪ]

40 — forty [‘fɔːtɪ]

50 — fifty [‘fɪftɪ]

60 — sixty [‘sɪkstɪ]

70 — seventy [‘sev (ə) ntɪ]

80 — eighty [‘eɪtɪ]

90 — ninety [‘naɪntɪ]

100 — one hundred [wʌn] [‘hʌndrɪd]

101 — one hundred and one

200 — two hundred

1000 — one thousand [wʌn] [‘θauz (ə) nd]

1000000 — one million [wʌn] [‘mɪljən]

Note:

1) To form numbers from 13 to 19, the suffix is used —teen, however, some numbers are formed in a special way:

13 — root —three— changes to —thir—

15 — root —five— changes to —fif—

18 — only one letter t

2) To form numbers from 20 to 90, the suffix is used —ty, however, some numbers are formed in a special way:

20 — the form of the word changes completely

30 — root —three— changes to —thir—

40 — root —four — changes to —for—

50 — root —five— changes to —fif—

18 — only one letter t

3) Numbers from 21 to 99 are hyphenated in words

4) Word hundredweight remains in the singular, regardless of the number in front of it. The same for words thousands и million.

Ordinals

Ordinal numbers are formed by adding a definite article the before the numeral and suffix —th… However, there are exceptions to this rule, these are numbers from one to five. Look at the table of formation of ordinal numbers:

1st — (the) first [fɜːst]

2st — (the) second [‘sek (ə) nd]

3st — (the) third [θɜːd]

4th — (the) fourth [fɔːθ]

5st — (the) fifth [fɪfθ]

9st — (the) nineth

10th — (the) tenth

16th — (the) sixteenth

29th — (the) twenty-ninth

73rd — (the) seventy-third

In this lesson, we will learn with you not only to greet our interlocutor, but also to ask how he is doing. Look at the words for the dialogue, the dialogue itself and its translation.

New words:

how [haʊ] — how

good [gʊd] — good

fine [faɪn] — ok

thanks / thank you [θæŋks] — thanks

goodbye / bye [gʊd’baɪ] — goodbye, bye

Source: https://linguistpro.net/chislitelnye-v-angliyskom-yazyke

Cardinal numbers in English

English cardinal numbers in form are divided into several varieties: simple, derivatives and compound.

Simples consist of one root, they are not formed from other numbers, so they should be well remembered. Simple numbers include all numerals from 0 to 12, as well as numerals-nouns one hundred, one thousand, one million, billion.

Derivatives consist of one word, formed from simple numbers with the addition of suffixes.

For numbers from 12 to 19, add the suffix -teen to the root. The resulting words have double stress on the first and second syllables, which makes it possible to distinguish them by ear from dozens. The second stress in a word is pronounced stronger than the first.

To form tens, denoting the numbers 20, 30, 40, and so on, add the suffix -ty to the stem. The stress in such numbers is placed on the first syllable.

Compound numbers are made up of multiple numbers. Dozens with ones in English are hyphenated, and hundreds are written separately. In each digit in British English, it is customary to put the union and after a hundred, but in the American version it is omitted.

Two hundred and sixteen = two hundred sixteen

Hundred, thousand, million, and milliard / billion are not plural in compound numbers. But if they are used as nouns without other numerals, for example, in the meaning of «hundred», then they can be put in the plural. In the singular, before them, the use of the article is mandatory.

Five thousand people — five thousand people

Thousands of people — thousands of people

Table with examples of cardinal numbers in English

| Simple | Derivatives | Composite | |

| 0-12, 100, 1000, 1000000 | 13-19 | 20-90 | Other |

| ZeroOneTwoThreeFourHundredThousandMillionMilliard / billion | + teenThirteenFourteenFifteen |

Source: https://lingua-airlines.ru/kb-article/kolichestvennye-chislitelnye-v-anglijskom/

Numbers in English with transcription in the table from 1 to 10:

| Digit / Number | Word with transcription |

| 1 | one [wʌn] |

| 2 | two [tuː] |

| 3 | three [θriː] |

| 4 | four [fɔː] |

| 5 | five [faɪv] |

| 6 | six [seks] |

| 7 | seven [‘sev (ə) n] |

| 8 | eight [eɪt] |

| 9 | nine [naɪn] |

| 10 | ten[ten] |

If you do not know English transcription and you need Russian transcription, listen to how numbers and numbers are read in English:

/audio/english-vocabulary-numbers.mp3 Download mp3

The number 0 is written like this: nought [nɔːt], zero [‘zɪərəu]

Numbers 11 to Million

More numbers in English from 11 to 20 and from 21 to 100:

| 11 | eleven [ɪ’lev (ə) n] |

| 12 | twelve [twelv] |

| 13 | thirteen [θɜː’tiːn] |

| 14 | fourteen [ˌfɔː’tiːn] |

| 15 | fifteen [ˌfɪf’tiːn] (note: “f”, not “v”) |

| 16 | sixteen [ˌsɪk’stiːn] |

| 17 | seventeen [ˌsev (ə) n’tiːn] |

| 18 | eighteen [ˌeɪ’tiːn] (only one «t») |

| 19 | nineteen [ˌnaɪn’tiːn] |

| 20 | twenty [‘twentɪ] |

| 21 | twenty-one [ˌtwentɪ’wʌn] (numbers from 21 to 99 are hyphenated in words) |

| 30 | thirty [‘θɜːtɪ] |

| 40 | forty [‘fɔːtɪ] (no letter “u”) |

| 50 | fifty [‘fɪftɪ] (note: “f”, not “v”) |

| 60 | sixty [‘sɪkstɪ] |

| 70 | seventy [‘sev (ə) ntɪ] |

| 80 | eighty [‘eɪtɪ] (only one «t») |

| 90 | ninety [‘naɪntɪ] (there is a letter “e”) |

| 100 | one hundred [wʌn] [‘hʌndrəd], [-rɪd] |

| 101 | one hundred and one |

| 200 | two hundred (the word hundred remains in the singular, regardless of the number in front of it) |

| 1000 | one thousand [wʌn] [‘θauz (ə) nd] (also true for thousands: two thousand) |

| 1,000,000 | one million [wʌn] [‘mɪljən] (also true for a million: two million) |

Cardinal and ordinal numbers

There are two types of numerals:

- quantitative (cardinal)

- ordinal (ordinal)

Everything is clear with the first group. Quantitative (cardinal) numerals are our one, two, three one hundred (one, two, three hundred).

But ordinal (ordinal) numerals are a bit tricky. Pointing to the order of the position or course of action (first, second, third hundredth), they are formed according to a certain rule, which was not without exceptions. Let’s consider the rule.

To form an ordinal number, it is necessary to add the ending -TH to the cardinal number.

If “four” is oven, then the «fourth» will be the fourth. «Six — sixth» — «six — thesixth ”.

Pay attention! Ordinal numbers are used with the article “The“.

And what about the exceptions? They are words «First, second, third, fifth»that need to be learned by heart:

| 1 | — the | first |

| 2 | second | |

| 3 | third | |

| 5 | fifth |

Ordinal numbers will be useful to us in order to name the date of your birth. (birthday).

Mu birthday is on the second (tenth, seventeenth) of May (January, June).

Use “on» to indicate the day and «Of» before the month name. By the way, historically, the names of calendar months are written with a capital letter. Remember this!

Ordinal numbers in English

| Number | Word |

| 1st | the first [ðiː] [fɜːst] |

| 2nd | the second [ðiː] [‘sek (ə) nd] |

| 3rd | the third [ðiː] [θɜːd] |

| 4th | the fourth [ðiː] [fɔːθ] |

| 5th | the fifth [ðiː] [fɪfθ] |

| 6th | the sixth [ðiː] [sɪksθ] |

| 7th | the seventh [ðiː] [‘sev (ə) nθ] |

| 8th | the eighth |

| 9th | the ninth |

| 10th | tenth |

| 11th | the eleventh |

| 12th | the twelfth |

| 13th | the third |

| 14th | the fourteenth |

| 15th | the fifteenth |

| 16th | the sixteenth |

| 17th | the seventeenth |

| 18th | the eighteenth |

| 19th | the nineteenth |

| 20th | the twentieth |

| 21st | the twenty-first |

| 30th | the third |

| 40th | the fortune |

| 50th | the fiftieth |

| 60th | the sixtieth |

| 70th | the seventies |

| 80th | the eightieth |

| 90th | the ninetieth |

| 100th | the hundredth |

| 101st | the hundred and first |

| 1000th | the thousandth |

Source: https://englishtexts.ru/english-grammar/english-numerals

Numerals in English. Numbers and numbers in English

Numbers in English have two functions:

- are responsible for counting objects: indicate the size, quantity;

- indicate the order in which items are counted — sequence.

Are they important; and if important, how much? It is easy not only to imagine, but also to check it yourself. For at least one day, try not to mention the exact information regarding:

- dates, times and deadlines;

- prices;

- telephone numbers and addresses;

- age;

- weights and distances.

Eventually, even talking about the weather gets a lot harder without mentioning temperature:

— How is it on the street?

— Coldly.

— How cold?

— Colder than yesterday!

— How cold was it yesterday ?!

— Colder than the day before yesterday !!!

So, without delaying or putting it on the back burner, we get down to numbers and numbers in English.

Cardinal numbers in English

Cardinal numbers, following their name, indicate the number of things (objects). At the same time, they answer the question — «how much?» (how many?).

dragonflies have four wings. — Dragonflies have 4 wings.

The company purchased ninety tons of coal. — The company purchased 90 tons of coal.

Simple numbers in English

They determine the score from 1 to 12.

Numbers in English

The figures — symbols used to write all numbers: whole, fractional, large and small. Without getting into higher mathematics and not counting punctuation marks (period, comma, slash), there are only 10 characters that we operate with for:

- counting: addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, etc.;

- designations of quantities: mass, time, temperature, etc.

These are the so-called «Arabic numerals» used in the vast majority of countries in the world to write numbers in the decimal system.

Source: https://englishboost.ru/tsifry-na-anglijskom/

Ordinal numbers English pronunciation — Secrets of a

Ordinal numbers English pronunciation

Let’s take a look at how ordinal numbers are written and pronounced in English. As always, this will require you to remember one simple rule and a few exceptions and peculiarities. They are more related to the written part. I will show the word, its transcription and pronunciation with translation. We will also discuss the rule for each number from 1 to 100. Ordinal numbers in English are pronunciation.

Ordinal numbers call things in order. Imagine cups.

The first cup is white, the second cup is black, the third cup is red, the fourth cup is blue, the fifth cup is green, and the sixth cup is yellow. A cup of this shape (or mug) is called a mug.

The first, second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth are ordinal numbers. They show in what order the circles are.

Rule: the article the is always used with ordinal numbers.

Rule: numerals do not change by gender. «First» and «first» will be denoted by the same word.

1. First, first or first, first will the first | fəːst |… Listen

The first circle is white. The first mug is white.

2. Second, second, second, second — the second — | ˈSɛk (ə) nd | Listen

The second mug is black. — The second circle is black.

3. Third, third, third, third — the third [θɜːd] Listen

The third mug is red. — The third circle is red. Could you give me the third mug, please? — Bring the third mug, please.

So, these three words «the first, the second, the third» are an exception, because they do not look like their «brothers», the words «one, two, three — one, two, three». They need to be remembered !!!

How to memorize words can be viewed click here

The rest of the words are derived from quantitative.

The rule is this. In most cases, you need to add — th to the end of the word to the cardinal number to get an ordinal number.

4. Fourth, fourth, fourth, fourth — The fourth [fɔːθ] Listen

He lives in the fourth house on the right of the street. — He lives in the fourth house on the right side of the street.

The smiths are the fourth who live in this house. “The Smiths are the fourth to live in this house.

Practice:

- So the word four is four. How do you say «fourth»? See the rule above. Add — th and don’t forget about the article the at the beginning. Fourth — the fourth. It’s not difficult, is it? )))

5. Fifth, fifth, fifth, fifth— the fifth — [fɪfθ] Listen

Rule: Ordinal numbers English pronunciation — in the word five, when forming an ordinal number, the final -e disappears, and the letter -v- changes to -f-

It will look like -fif-. Add the previous rules — the article and the ending -th. Fifth — the fifth

Why such a rule, you ask? This is due to phonetics. The -th ending is a dull sound [θ]. And the letter -v- sounds sonorous (remember the paired consonants in voicing — deafness from the first grade of school) in-f. Since the final sound is deaf, the previous sound must also be deaf, so we replace the letter: vf

I am the fifth child in the family — I am the fifth child in the family.

Do not confuse the words “forth” (“come forth”) and “fourth”. They sound the same.

Ordinal numbers English pronunciation

6. Sixth, sixth, sixth, sixth — the sixth [sɪksθ] Listen

He started his sixth year at school. — He started his sixth year at school.

Rule: the article the can be replaced with possessive pronouns according to the meaning (my — my, his — his, her — her, their — their, our — our)

my sixth bike — My sixth bike (Can’t my the sixth bike)

I’ve broken my sixth bike this year — I crashed my sixth bike this year.

7. Seventh, seventh, seventh, seventh — the seventh [ˈSevnθ] Listen

The their seventh wedding anniversary they are going to Paris. “They are going to Paris for their seventh wedding anniversary.

8. Eighth, eighth, eighth, eighth — the eighth [eɪtθ] Listen

Rule: When writing the eighth, the letter t is removed from the word eight so that there is no repetition (the + eight + th)

9. Ninth, ninth, ninth, ninth — the ninth[naɪnθ] Listen

Rule: if the number at the end is -e, it is removed in the ordinal number.

estatee-the ninth — nine — ninth

10. Tenth, tenth, tenth, tenth — the tenth [tenθ] Listen

Song about Ordinal numbers English pronunciation

| Quantitative | Ordinal | Transcription | Transfer |

| eleven | eleventh | [ɪˈlevnθ] | eleventh |

| twelve | Twelfth (rule) | [twelfθ] | twelfth |

| thirteen | thirteenth | [ˌΘɜːˈtiːnθ] | thirteenth |

| fourteen | fourteenth | [ˌFɔːˈtiːnθ] | fourteenth |

| fifteen | Fifteenth (rule) | [ˌFɪfˈtiːnθ] | fifteenth |

| sixteen | sixteenth | [siːkˈstiːnθ] | sixteenth |

| seventeen | seventeenth | [ˌSevnˈtiːnθ] | seventeenth |

| eighteen | eighteenth | [ˌEɪˈtiːnθ] | eighteenth |

| nineteen | nineteenth | [ˌNaɪnˈtiːnθ] | nineteenth |

11. Twentieth, twentieth, twentieth, twentieth [ˈtwentɪəθ] Listen

Rule: When forming an ordinal from twenty — twenty, the letter y changes to -ie-: twenty — the + twent + ie + th

Practice: how to say twenty-first — 21 th? Only the last number changes. Word twenty remains quantitative. twenty. And the word one changes to the first word — the first. In this case, the article is placed from the very beginning of the word «twenty-first». There is a hyphen between tens and ones. The + twenty + — + first.

The twenty-first [ˈtwɛntiˈfɜrst] Listen

| Quantitative | Ordinal | Transcription | Transfer |