Updated: June 11, 2022 by Mylene in Pronunciation Lessons ▪

Most languages employ mechanisms to highlight particular words or a group of words while speaking. Speakers tend to put more effort when pronouncing focus and informational words. These efforts vary between languages in terms of where the stress is realized, its length, and its intensity. Stress in the French language is located at the last full syllable of a word. All the other syllables in a word or in a phrase are not stressed in French. From a phonetic perspective and for the convenience of comparing French with other languages, French is a language with a fixed accent. Thus, French is considered a boundary language.

In this article, you will find out the right way to employ stress in a sentence when speaking French. In addition, we’ll go through the different types of stress in French with examples and exercises.

I will cover the following questions:

- Are French syllables stressed?

- How to use the tonic accent in French?

- Where is the stress in the French language?

- How to use the affective accent in French?

What’s accentuation in French?

French has a stress accent whenever a syllable in a word is given more emphasis. This phonetic prominence of a particular syllable is characterized by lengthening the last syllable of a word. Only the last word is accented in this example:

- Le chat

- Le petit chat

- Le très petit chat

- Le très petit chat maladroit

Are French syllables stressed?

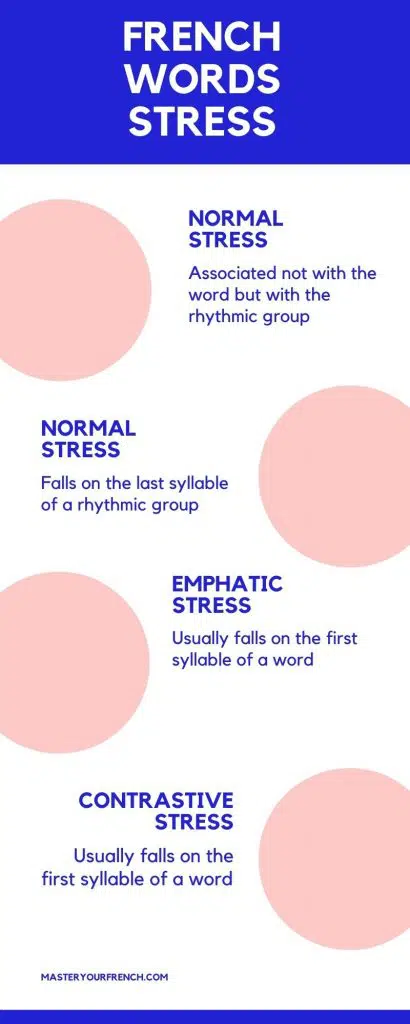

Yes, there are two types of stress in French:

- the tonic accent: it allows to determine the rhythmic groups

- the affective accent: it allows to transmit an emotion

How to use the tonic accent in French?

The French tonic accent is placed at the end of a group of words. In fact, the French tonic accent is a group accent, not a word accent. In French, there is no variation in the place of the stress nor in their numbers.

But how to determine a group of words in French?

When you speak, you are delivering a message. A message is made up of groups of breath which constitute a complete unity of meaning: a sentence. A breath group can contain several rhythm groups. The voice rises at the end of each rhythm group: this is the intonation. These rhythmic groups constitute partial units of meaning.

The tonic emphasis is always placed on the last syllable of the rhythm group. This accentuation results in an elongation of the syllable.

Example: Elles ont diné hier soir à Dijon (They had dinner last night in Dijon).

There are three rhythmic groups and therefore three stressed syllables (in bold):

- elles ont diné

- hier soir

- à Dijon

How to determine rhythmic groups in French?

The rhythmic group usually has 2 to 4 syllables and up to a maximum of 9 syllables. Then you have to breathe in order to start a new rhythmic group. The stress has a demarcating function: it makes it possible to divide easily recognizable units of meaning. These units of meaning are the rhythmic groups. In general, rhythmic groups correspond to syntactic units (subject, verb, object complement, circumstantial complement, …).

- Elles ont diné hier soir à Dijon: there are 3 syntactic units and therefore 3 stressed syllables.

The emphasis is flexible and variable. The rhythmic groups can be cut in a very flexible way:

- Elles ont diné hier soir à Dijon: there are 2 syntactic units and therefore 2 stressed syllables.

- Elles ont diné hier soir à Dijon: there are 1 syntactic units and therefore 1 stressed syllable.

Remember that there will be a maximum of 9 syllables. You must re-learn your breath!

Where is the stress in the French language?

The stress falls on the final syllable. In the case of the French tonic accent, the vowel in the final syllable is lengthened and stronger. Here are a few examples :

- Le chat

- Le chat noir

- Le joli chat noir

- Le très joli chat noir

The syllable in bold is stronger and longer than all the other syllables.

How to use the affective accent in French?

The stress is placed on a syllable that is normally not stressed. The accentuation then translates into a feeling.

The stressed syllable is on average twice longer than the unstressed syllable.

Léon 1882

When you want to add stress into a word within a sentence, you have to isolate the word. The French affective accent does not replace the French tonic accent. In reality, it is added to the normal rhythm of the sentence. It can be used for:

- contrastive stress : ce n’est pas maintenant, c’est après

- emphatic stress : c’était génial

- differentiation (accent intellectuel) : des habits d’été , d’hiver

Once again, the French affective accent does not replace the tonic accent, however, is added to the normal rhythm of the sentence. The main emphasis is on the lengthening of the first or the second pronounced syllable.

Exercises

Try to pronounce these well-known words in French:

- Le week end

- Le parking

- Le sandwich

- Bill Clinton

Speak French better

Knowing the rules is the first step in your learning. You must now practice what you have just learned. But learning the pronunciation on your own can be very complicated. You need someone to point you out and explain where your mistakes are. And that’s where Master Your French dedicated program to teach the spoken language comes into play. To go beyond all your pronunciation difficulties in French book a study session to receive personalized advice.

This is why I said «I don’t isist».

Let’s see if I make me understood with some example containing e muet and e caduc.

Let’s take those words formed by three syllables where the stress is on the last syllable and there are two pretonic «e» in open syllable.

In these words there is a stressed syllable (the last) and two «unstressed syllables, but the first has a secondary stress (countertonic syllable) while the second is totally unstressed (intertonic syllable).

épeler, élever, dépecer, dételer, déceler.

ep(ə)’le, el(ə)’ve, dep(ə)’se, del(ə)’te, des(ə)’le.

As you can see, the last syllable is stressed, the first has secondary stress, so it is pronounced [e], and the second is totally unstressed, i.e it is pronounced with e muet [ə] or dropped, e caduc. The pattern is secondary stress, unstressed, primary stress.

We find the same pattern in words like:

relever, revenue

rəl(ə)’ve, rəv(ə)’ny.

In fact, in relaxed pronunciation, which unstressed «e» is more likely to be dropped? That on the second, totally unstressed, syllable.

There are words like téléphone, where both unstressed «e» in open syllables are retained but we don’t find words with this pattern, e caduc, secondary stressed «e» in open syllable, stressed «e».

The pattern is secondary stress, unstressed, primary stress.

When Northern French speakers pronounce two words into a sentence, they will pronounce it as if it were a single word, i.e with this pattern, secondary stress, unstressed, primary stress.

So, château blanc and excusez-moi have this pattern, unstressed, secondary stress, primary stress. French speakers move the secondary stress two syllables before the stressed syllable of the prosodic group, pronouncing this part of sentence like a single word, i.e secondary stress, unstressed, primary stress, pronouncing château blanc and excusez-moi. This is the reason why tout le monde says that French speakers pronounce sentences as if they were single words.

Those people having a strong Southern French accent have a different prosody, i.e they don’t move the secondary stress of the prosodic unit (but less and less people have a strong Southern French accent).

They say château blanc and excusez-moi.

petite petite

la petite fille la petite fille

For assistance with IPA transcriptions of French for Wikipedia articles, see Help:IPA/French.

French phonology is the sound system of French. This article discusses mainly the phonology of all the varieties of Standard French. Notable phonological features include its uvular r, nasal vowels, and three processes affecting word-final sounds:

- liaison, a specific instance of sandhi in which word-final consonants are not pronounced unless they are followed by a word beginning with a vowel;

- elision, in which certain instances of /ə/ (schwa) are elided (such as when final before an initial vowel);

- enchaînement (resyllabification) in which word-final and word-initial consonants may be moved across a syllable boundary, with syllables crossing word boundaries:

An example of the above is this:

- Written: On a laissé la fenêtre ouverte.

- Meaning: «We left the window open.»

- In isolation: /ɔ̃ a lɛse la fənɛːt(ʁ) uvɛʁt/

- Together: [ɔ̃.na.lɛ.se.laf.nɛ.tʁu.vɛʁt]

ConsonantsEdit

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar/ Uvular |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | ||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ʁ | ||

| Approximant | plain | l | j | |||

| labial | ɥ | w |

Distribution of guttural r (such as [ʁ ʀ χ]) in Europe in the mid-20th century.[1]

not usual

only in some educated speech

usual in educated speech

general

Phonetic notes:

- /n, t, d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [n̪, t̪, d̪],[2][3] while /s, z/ are dentalised laminal alveolar [s̪, z̪] (commonly called ‘dental’), pronounced with the blade of the tongue very close to the back of the upper front teeth, with the tip resting behind lower front teeth.[2][4]

- Word-final consonants are always released. Generally, /b, d, ɡ/ are voiced throughout and /p, t, k/ are unaspirated.[5]

- /l/ is usually apical alveolar [l̺] but sometimes laminal denti-alveolar [l̪].[3] Before /f, ʒ/, it can be realised as retroflex [ɭ].[3]

- In current pronunciation, /ɲ/ is merging with /nj/.[6]

- The velar nasal /ŋ/ is not a native phoneme of French, but it occurs in loan words such as camping, smoking or kung-fu.[7] Some speakers who have difficulty with this consonant realise it as a sequence [ŋɡ] or replace it with /ɲ/.[8] It could be considered a separate phoneme in Meridional French, e.g. pain /pɛŋ/ (‘bread’) vs. penne /pɛn/ (‘quill’).

- The approximants /j, ɥ, w/ correspond to the close vowels /i, y, u/. While there are a few minimal pairs (such as loua /lu.a/ ‘s/he rented’ and loi /lwa/ ‘law’), there are many cases where there is free variation.[5]

- Belgian French may merge /ɥ/ with /w/ or /y/.[citation needed]

- Some dialects of French have a palatal lateral /ʎ/ (French: l mouillé, ‘wet l’), but in the modern standard variety, it has merged with /j/. [9] Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:47) See also Glides and diphthongs, below.

- The French rhotic has a wide range of realizations: the voiced uvular fricative [ʁ], also realised as an approximant [ʁ̞], with a voiceless positional allophone [χ], the uvular trill [ʀ], the alveolar trill [r], and the alveolar tap [ɾ]. These are all recognised as the phoneme /r/,[5] but [r] and [ɾ] are considered dialectal. The most common pronunciation is [ʁ] as a default realisation, complemented by a devoiced variant [χ] in the positions before or after a voiceless obstruent or at the end of a sentence. See French guttural r and map at right.

- Velars /k/ and /ɡ/ may become palatalised to [kʲ⁓c] and [ɡʲ⁓ɟ] before /i, e, ɛ/, and more variably before /a/.[10] Word-final /k/ may also be palatalised to [kʲ].[11] Velar palatalisation has traditionally been associated with the working class,[12] though recent studies suggest it is spreading to more demographics of large French cities.[11]

| Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Example | Gloss | IPA | Example | Gloss | ||

| /p/ | /pu/ | pou | ‘louse’ | /b/ | /bu/ | boue | ‘mud’ |

| /t/ | /tu/ | tout | ‘all’, ‘anything’ (possibility) | /d/ | /du/ | doux | ‘sweet’ (food, feelings), ‘gentle’ (person), ‘mild’ (weather) |

| /k/ | /ku/ | cou | ‘neck’ | /ɡ/ | /ɡu/ | goût | ‘taste’ |

| /f/ | /fu/ | fou | ‘crazy’ | /v/ | /vu/ | vous | ‘you’ |

| /s/ | /su/ | sous | ‘under’, ‘on’ (drugs), ‘in’ (packaging), ‘within’ (times) | /z/ | /zu/ | zou | ‘shoo’ |

| /ʃ/ | /ʃu/ | chou | ‘cabbage’, ‘lovely’ (person, pet) | /ʒ/ | /ʒu/ | joue | ‘cheek’ |

| /m/ | /mu/ | mou | ‘soft’, ‘weak’ (stronger: person, actions) | ||||

| /n/ | /nu/ | nous | ‘we, us’ | ||||

| /ɲ/ | /ɲu/ | gnou | ‘gnu’ (dated, /ɡnu/ in modern French) | ||||

| /ŋ/ | /kuŋ.fu/ | kung-fu | ‘kung-fu’ | ||||

| /l/ | /lu/ | loup | ‘wolf’ | ||||

| /ʁ/ | /ʁu/ | roue | ‘wheel’ |

GeminatesEdit

Although double consonant letters appear in the orthographic form of many French words, geminate consonants are relatively rare in the pronunciation of such words. The following cases can be identified.[14]

The geminate pronunciation [ʁʁ] is found in the future and conditional forms of the verbs courir (‘to run’) and mourir (‘to die’). The conditional form il mourrait [il.muʁ.ʁɛ] (‘he would die’), for example, contrasts with the imperfect form il mourait [il.mu.ʁɛ] (‘he was dying’). In some other words, most modern speakers have reduced [ʁʁ] to [ʁ], such as «il pourrait» (‘he could’). Other verbs that have a double ⟨rr⟩ orthographically in the future and conditional are pronounced with a simple [ʁ]: il pourra (‘he will be able to’), il verra (‘he will see’).

When the prefix in- combines with a base that begins with n, the resulting word is sometimes pronounced with a geminate [nn] and similarly for the variants of the same prefix im-, il-, ir-:

- inné [i(n).ne] (‘innate’)

- immortel [i(m).mɔʁtɛl] (‘immortal’)

- illisible [i(l).li.zibl] (‘illegible’)

- irresponsable [i(ʁ).ʁɛs.pɔ̃.sabl] (‘irresponsible’)

Other cases of optional gemination can be found in words like syllabe (‘syllable’), grammaire (‘grammar’), and illusion (‘illusion’). The pronunciation of such words, in many cases, a spelling pronunciation varies by speaker and gives rise to widely varying stylistic effects.[15] In particular, the gemination of consonants other than the liquids and nasals /m n l ʁ/ is «generally considered affected or pedantic».[16] Examples of stylistically marked pronunciations include addition [ad.di.sjɔ̃] (‘addition’) and intelligence [ɛ̃.tɛl.li.ʒɑ̃s] (‘intelligence’).

Gemination of doubled ⟨m⟩ and ⟨n⟩ is typical of the Languedoc region, as opposed to other southern accents.

A few cases of gemination do not correspond to double consonant letters in the orthography.[17] The deletion of word-internal schwas (see below), for example, can give rise to sequences of identical consonants: là-dedans [lad.dɑ̃] (‘inside’), l’honnêteté [lɔ.nɛt.te] (‘honesty’). The elided form of the object pronoun l’ (‘him/her/it’) is also realised as a geminate [ll] when it appears after another l to avoid misunderstanding:

- Il l’a mangé [il.lamɑ̃.ʒe] (‘He ate it’)

- Il a mangé [il.amɑ̃.ʒe] (‘He ate’)

Gemination is obligatory in such contexts.

Finally, a word pronounced with emphatic stress can exhibit gemination of its first syllable-initial consonant:

- formidable [fːɔʁ.mi.dabl] (‘terrific’)

- épouvantable [e.pːu.vɑ̃.tabl] (‘horrible’)

LiaisonEdit

Many words in French can be analyzed as having a «latent» final consonant that is pronounced only in certain syntactic contexts when the next word begins with a vowel. For example, the word deux /dø/ (‘two’) is pronounced [dø] in isolation or before a consonant-initial word (deux jours /dø ʒuʁ/ → [dø.ʒuʁ] ‘two days’), but in deux ans /døz‿ɑ̃/ (→ [dø.zɑ̃] ‘two years’), the linking or liaison consonant /z/ is pronounced.

VowelsEdit

Vowels of Parisian French, from Collins & Mees (2013:225–226). Some speakers merge /œ̃/ with /ɛ̃/ (especially in the northern half of France) and /a/ with /ɑ/. In the latter case, the outcome is an open central [ä] between the two (not shown on the chart).

Standard French contrasts up to 13 oral vowels and up to 4 nasal vowels. The schwa (in the center of the diagram next to this paragraph) is not necessarily a distinctive sound. Even though it often merges with one of the mid front rounded vowels, its patterning suggests that it is a separate phoneme (see the subsection Schwa below).

The table below primarily lists vowels in contemporary Parisian French, with vowels only present in other dialects in parentheses.

Oral

|

Nasal

|

While some dialects feature a long /ɛː/ distinct from /ɛ/ and a distinction between an open front /a/ and an open back /ɑ/, Parisian French features only /ɛ/ and just one open vowel /a/ realised as central [ä]. Some dialects also feature a rounded /œ̃/, which has merged with /ɛ̃/ in Paris.

In French French, while /ə/ is phonologically distinct, its phonetic quality tends to coincide with either /ø/ or /œ/.

Example words| Vowel | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Orthography | Gloss | |

| Oral vowels | |||

| /i/ | /si/ | si | ‘if’ |

| /e/ | /fe/ | fée | ‘fairy’ |

| /ɛ/ | /fɛ/ | fait | ‘does’ |

| /ɛː/† | /fɛːt/ | fête | ‘party’ |

| /y/ | /sy/ | su | ‘known’ |

| /ø/ | /sø/ | ceux | ‘those’ |

| /œ/ | /sœʁ/ | sœur | ‘sister’ |

| /ə/ | /sə/ | ce | ‘this’/’that’ |

| /u/ | /su/ | sous | ‘under’ |

| /o/ | /so/ | sot | ‘silly’ |

| /ɔ/ | /sɔʁ/ | sort | ‘fate’ |

| /a/ | /sa/ | sa | ‘his’/’her’ |

| /ɑ/† | /pɑt/ | pâte | ‘dough’ |

| Nasal vowels | |||

| /ɑ̃/ | /sɑ̃/ | sans | ‘without’ |

| /ɔ̃/ | /sɔ̃/ | son | ‘his’ |

| /ɛ̃/[18] | /bʁɛ̃/ | brin | ‘twig’ |

| /œ̃/† | /bʁœ̃/ | brun | ‘brown’ |

| Semi-vowels | |||

| /j/ | /jɛʁ/ | hier | ‘yesterday’ |

| /ɥ/ | /ɥit/ | huit | ‘eight’ |

| /w/ | /wi/ | oui | ‘yes’ |

| † Not distinguished in all dialects. |

Close vowelsEdit

In contrast with the mid vowels, there is no tense–lax contrast in close vowels. However, non-phonemic lax (near-close) [ɪ, ʏ, ʊ] appear in Quebec as allophones of /i, y, u/ when the vowel is both phonetically short (so not before /v, z, ʒ, ʁ/) and in a closed syllable, so that e.g. petite [pə.t͡sɪt] ‘small (f.)’ differs from petit ‘small (m.)’ [pə.t͡si] not only in the presence of the final /t/ but also in the tenseness of the /i/. Laxing always occurs in stressed closed syllables, but it is also found in other environments to various degrees.[19][20]

In French French, /i, u/ are consistently close [i, u],[21][22][23] but the exact height of /y/ is somewhat debatable as it has been variously described as close [y][21][22] and near-close [ʏ].[23]

Mid vowelsEdit

Although the mid vowels contrast in certain environments, there is a limited distributional overlap so they often appear in complementary distribution. Generally, close-mid vowels (/e, ø, o/) are found in open syllables, and open-mid vowels (/ɛ, œ, ɔ/) are found in closed syllables. However, there are minimal pairs:[21]

- open-mid /ɛ/ and close-mid /e/ contrast in final-position open syllables:

- allait [a.lɛ] (‘was going’), vs. allé [a.le] (‘gone’);

- likewise, open-mid /ɔ/ and /œ/ contrast with close-mid /o/ and /ø/ mostly in closed monosyllables, such as these:

- jeune [ʒœn] (‘young’), vs. jeûne [ʒøn] (‘fast’, verb),

- roc [ʁɔk] (‘rock’), vs. rauque [ʁok] (‘hoarse’),

- Rhodes [ʁɔd] (‘Rhodes’), vs. rôde [ʁod] (‘[I] lurk’),

- Paul [pɔl] (‘Paul’, masculine), vs. Paule [pol] (‘Paule’, feminine),

- bonne [bɔn] (‘good’, feminine), vs. Beaune [bon] (‘Beaune’, the city).

Beyond the general rule, known as the loi de position among French phonologists,[24] there are some exceptions. For instance, /o/ and /ø/ are found in closed syllables ending in [z], and only [ɔ] is found in closed monosyllables before [ʁ], [ɲ], and [ɡ].[25]

The Parisian realization of /ɔ/ has been variously described as central [ɞ][23] and centralized to [ɞ] before /ʁ/,[2] in both cases becoming similar to /œ/.

The phonemic opposition of /ɛ/ and /e/ has been lost in the southern half of France, where these two sounds are found only in complementary distribution. The phonemic oppositions of /ɔ/ and /o/ and of /œ/ and /ø/ in terminal open syllables have been lost in almost all of France, but not in Belgium or in areas with an Arpitan substrate, where pot and peau are still opposed as /pɔ/ and /po/.[26]

Open vowelsEdit

The phonemic contrast between front /a/ and back /ɑ/ is sometimes not maintained in Standard French, which leads some researchers to reject the idea of two distinct phonemes.[27] However, the distinction is still clearly maintained in other dialects such as Quebec French.[28]

While there is much variation among speakers in France, a number of general tendencies can be observed. First of all, the distinction is most often preserved in word-final stressed syllables such as in these minimal pairs:

- tache /taʃ/ → [taʃ] (‘stain’), vs. tâche /tɑʃ/ → [tɑʃ] (‘task’)

- patte /pat/ → [pat] (‘leg’), vs. pâte /pɑt/ → [pɑt] (‘paste, pastry’)

- rat /ʁa/ → [ʁa] (‘rat’), vs. ras /ʁɑ/ → [ʁɑ] (‘short’)

There are certain environments that prefer one open vowel over the other. For example, /ɑ/ is preferred after /ʁw/ and before /z/:

- trois [tʁwɑ] (‘three’),

- gaz [ɡɑz] (‘gas’).[29]

The difference in quality is often reinforced by a difference in length (but the difference is contrastive in final closed syllables). The exact distribution of the two vowels varies greatly from speaker to speaker.[30]

Back /ɑ/ is much rarer in unstressed syllables, but it can be encountered in some common words:

- château [ʃɑ.to] (‘castle’),

- passé [pɑ.se] (‘past’).

Morphologically complex words derived from words containing stressed /ɑ/ do not retain it:

- âgé /ɑʒe/ → [aː.ʒe] (‘aged’, from âge /ɑʒ/ → [ɑʒ])

- rarissime /ʁaʁisim/ → [ʁaʁisim] (‘very rare’, from rare /ʁɑʁ/ → [ʁɑʁ]).

Even in the final syllable of a word, back /ɑ/ may become [a] if the word in question loses its stress within the extended phonological context:[29]

- J’ai été au bois /ʒe ete o bwɑ/ → [ʒe.e.te.o.bwɑ] (‘I went to the woods’),

- J’ai été au bois de Vincennes /ʒe ete o bwɑ dəvɛ̃sɛn/ → [ʒe.e.te.o.bwad.vɛ̃.sɛn] (‘I went to the Vincennes woods’).

Nasal vowelsEdit

The phonetic qualities of the back nasal vowels differ from those of the corresponding oral vowels. The contrasting factor that distinguishes /ɑ̃/ and /ɔ̃/ is the extra lip rounding of the latter according to some linguists,[31] and tongue height according to others.[32] Speakers who produce both /œ̃/ and /ɛ̃/ distinguish them mainly through increased lip rounding of the former, but many speakers use only the latter phoneme, especially most speakers in northern France such as Paris (but not farther north, in Belgium).[31][32]

In some dialects, particularly that of Europe, there is an attested tendency for nasal vowels to shift in a counterclockwise direction: /ɛ̃/ tends to be more open and shifts toward the vowel space of /ɑ̃/ (realised also as [æ̃]), /ɑ̃/ rises and rounds to [ɔ̃] (realised also as [ɒ̃]) and /ɔ̃/ shifts to [õ] or [ũ]. Also, there also is an opposite movement for /ɔ̃/ for which it becomes more open and unrounds to [ɑ̃], resulting in a merger of Standard French /ɔ̃/ and /ɛ̃/ in this case.[32][33] According to one source, the typical phonetic realization of the nasal vowels in Paris is [æ̃] for /ɛ̃/, [ɑ̃] for /ɑ̃/ and [õ̞] for /ɔ̃/, suggesting that the first two are unrounded open vowels that contrast by backness (like the oral /a/ and /ɑ/ in some accents), whereas /ɔ̃/ is much closer than /ɛ̃/.[34]

In Quebec French, two of the vowels shift in a different direction: /ɔ̃/ → [õ], more or less as in Europe, but /ɛ̃/ → [ẽ] and /ɑ̃/ → [ã].[35]

In the Provence and Occitanie regions, nasal vowels are often realized as oral vowels before a stop consonant, thus reviving the ⟨n⟩ otherwise lost in other accents: quarante /kaʁɑ̃t/ → [kaʁantə].

Contrary to the oral /ɔ/, there is no attested tendency for the nasal /ɔ̃/ to become central in any accent.

SchwaEdit

When phonetically realised, schwa (/ə/), also called e caduc (‘dropped e’) and e muet (‘mute e’), is a mid-central vowel with some rounding.[21] Many authors consider it to be phonetically identical to /œ/.[36][37] Geoff Lindsey suggests the symbol ⟨ɵ⟩.[38][39] Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006) state, more specifically, that it merges with /ø/ before high vowels and glides:

- netteté /nɛtəte/ → [nɛ.tø.te] (‘clarity’),

- atelier /atəlje/ → [a.tø.lje] (‘workshop’),

in phrase-final stressed position:

- dis-le ! /di lə/ → [di.lø] (‘say it’),

and that it merges with /œ/ elsewhere.[40] However, some speakers make a clear distinction, and it exhibits special phonological behavior that warrants considering it a distinct phoneme. Furthermore, the merger occurs mainly in the French of France; in Quebec, /ø/ and /ə/ are still distinguished.[41]

The main characteristic of French schwa is its «instability»: the fact that under certain conditions it has no phonetic realization.

- That is usually the case when it follows a single consonant in a medial syllable:

- appeler /apəle/ → [ap.le] (‘to call’),

- It is occasionally mute in word-final position:

- porte /pɔʁtə/ → [pɔʁt] (‘door’).

- Word-final schwas are optionally pronounced if preceded by two or more consonants and followed by a consonant-initial word:

- une porte fermée /yn(ə) pɔʁt(ə) fɛʁme/ → [yn.pɔʁ.t(ə).fɛʁ.me] (‘a closed door’).

- In the future and conditional forms of -er verbs, however, the schwa is sometimes deleted even after two consonants[citation needed]:

- tu garderais /ty ɡaʁdəʁɛ/ → [ty.ɡaʁ.d(ə.)ʁɛ] (‘you would guard’),

- nous brusquerons [les choses] /nu bʁyskəʁɔ̃/ → [nu.bʁys.k(ə.)ʁɔ̃] (‘we will precipitate [things]’).

- On the other hand, it is pronounced word-internally when it follows more pronounced consonants that cannot be combined into a complex onset with the initial consonants of the next syllable:

- gredin /ɡʁədɛ̃/ → [ɡʁə.dɛ̃] (‘scoundrel’),

- sept petits /sɛt pəti/ → [sɛt.pə.ti] (‘seven little ones’).[42]

In French versification, word-final schwa is always elided before another vowel and at the ends of verses. It is pronounced before a following consonant-initial word.[43] For example, une grande femme fut ici, [yn ɡʁɑ̃d fam fy.t‿i.si] in ordinary speech, would in verse be pronounced [y.nə ɡʁɑ̃.də fa.mə fy.t‿i.si], with the /ə/ enunciated at the end of each word.

Schwa cannot normally be realised as a front vowel ([œ]) in closed syllables. In such contexts in inflectional and derivational morphology, schwa usually alternates with the front vowel /ɛ/:

- harceler /aʁsəle/ → [aʁ.sœ.le] (‘to harass’), with

- il harcèle /il aʁsɛl/ → [i.laʁ.sɛl] (‘[he] harasses’).[44]

A three-way alternation can be observed, in a few cases, for a number of speakers:

- appeler /apəle/ → [ap.le] (‘to call’),

- j’appelle /ʒ‿apɛl/ → [ʒa.pɛl] (‘I call’),

- appellation /apelasjɔ̃/ → [a.pe.la.sjɔ̃] (‘brand’), which can also be pronounced [a.pɛ.la.sjɔ̃].[45]

Instances of orthographic ⟨e⟩ that do not exhibit the behaviour described above may be better analysed as corresponding to the stable, full vowel /œ/. The enclitic pronoun le, for example, always keeps its vowel in contexts like donnez-le-moi /dɔne lə mwa/ → [dɔ.ne.lœ.mwa] (‘give it to me’) for which schwa deletion would normally apply (giving *[dɔ.nɛl.mwa]), and it counts as a full syllable for the determination of stress.

Cases of word-internal stable ⟨e⟩ are more subject to variation among speakers, but, for example, un rebelle /œ̃ ʁəbɛl/ (‘a rebel’) must be pronounced with a full vowel in contrast to un rebond /œ̃ ʁəbɔ̃/ → or [œ̃ʁ.bɔ̃] (‘a bounce’).[46]

LengthEdit

Except for the distinction still made by some speakers between /ɛ/ and /ɛː/ in rare minimal pairs like mettre [mɛtʁ] (‘to put’) vs. maître [mɛːtʁ] (‘teacher’), variation in vowel length is entirely allophonic. Vowels can be lengthened in closed, stressed syllables, under the following two conditions:

- /o/, /ø/, /ɑ/, and the nasal vowels are lengthened before any consonant: pâte [pɑːt] (‘dough’), chante [ʃɑ̃ːt] (‘sings’).

- All vowels are lengthened if followed by one of the voiced fricatives—/v/, /z/, /ʒ/, /ʁ/ (not in combination)—or by the cluster /vʁ/: mer/mère [mɛːʁ] (‘sea/mother’), crise [kʁiːz] (‘crisis’), livre [liːvʁ] (‘book’),[47] Tranel (1987:49–51) However, words such as (ils) servent [sɛʁv] (‘(they) serve’) or tarte [taʁt] (‘pie’) are pronounced with short vowels since the /ʁ/ appears in clusters other than /vʁ/.

When such syllables lose their stress, the lengthening effect may be absent. The vowel [o] of saute is long in Regarde comme elle saute !, in which the word is phrase-final and therefore stressed, but not in Qu’est-ce qu’elle saute bien ![48] In accents wherein /ɛː/ is distinguished from /ɛ/, however, it is still pronounced with a long vowel even in an unstressed position, as in fête in C’est une fête importante.[48]

The following table presents the pronunciation of a representative sample of words in phrase-final (stressed) position:

| Phoneme | Vowel value in closed syllable | Vowel value in open syllable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-lengthening consonant | Lengthening consonant | |||||

| /i/ | habite | [a.bit] | livre | [liːvʁ] | habit | [a.bi] |

| /e/ | — | été | [e.te] | |||

| /ɛ/ | faites | [fɛt] | faire | [fɛːʁ] | fait | [fɛ] |

| /ɛː/ | fête | [fɛːt] | rêve | [ʁɛːv] | — | |

| /ø/ | jeûne | [ʒøːn] | joyeuse | [ʒwa.jøːz] | joyeux | [ʒwa.jø] |

| /œ/ | jeune | [ʒœn] | œuvre | [œːvʁ] | — | |

| /o/ | saute | [soːt] | rose | [ʁoːz] | saut | [so] |

| /ɔ/ | sotte | [sɔt] | mort | [mɔːʁ] | — | |

| /ə/ | — | le | [lə] | |||

| /y/ | débute | [de.byt] | juge | [ʒyːʒ] | début | [de.by] |

| /u/ | bourse | [buʁs] | bouse | [buːz] | bout | [bu] |

| /a/ | rate | [ʁat] | rage | [ʁaːʒ] | rat | [ʁa] |

| /ɑ/ | appâte | [a.pɑːt] | rase | [ʁɑːz] | appât | [a.pɑ] |

| /ɑ̃/ | pende | [pɑ̃ːd] | genre | [ʒɑ̃ːʁ] | pends | [pɑ̃] |

| /ɔ̃/ | réponse | [ʁe.pɔ̃ːs] | éponge | [e.pɔ̃ːʒ] | réponds | [ʁe.pɔ̃] |

| /œ̃/ | emprunte | [ɑ̃.pʁœ̃ːt] | grunge | [ɡʁœ̃ːʒ] | emprunt | [ɑ̃.pʁœ̃] |

| /ɛ̃/ | teinte | [tɛ̃ːt] | quinze | [kɛ̃ːz] | teint | [tɛ̃] |

DevoicingEdit

In Parisian French, the close vowels /i, y, u/ and the mid front /e, ɛ/ at the end of utterances can be devoiced. A devoiced vowel may be followed by a sound similar to the voiceless palatal fricative [ç]:

- Merci. /mɛʁsi/ → [mɛʁ.si̥ç] (‘Thank you.’),

- Allez ! /ale/ → [a.le̥ç] (‘Go!’).[49]

In Quebec French, close vowels are often devoiced when unstressed and surrounded by voiceless consonants:

- université /ynivɛʁsite/ → [y.ni.vɛʁ.si̥.te] (‘university’).[50]

Though a more prominent feature of Quebec French, phrase-medial devoicing is also found in European French.[51]

ElisionEdit

The final vowel (usually /ə/) of a number of monosyllabic function words is elided in syntactic combinations with a following word that begins with a vowel. For example, compare the pronunciation of the unstressed subject pronoun, in je dors /ʒə dɔʁ/ [ʒə.dɔʁ] (‘I am sleeping’), and in j’arrive /ʒ‿aʁiv/ [ʒa.ʁiv] (‘I am arriving’).

Glides and diphthongsEdit

The glides [j], [w], and [ɥ] appear in syllable onsets immediately followed by a full vowel. In many cases, they alternate systematically with their vowel counterparts [i], [u], and [y] such as in the following pairs of verb forms:

- nie [ni]; nier [nje] (‘deny’)

- loue [lu]; louer [lwe] (‘rent’)

- tue [ty]; tuer [tɥe] (‘kill’)

The glides in the examples can be analyzed as the result of a glide formation process that turns an underlying high vowel into a glide when followed by another vowel: /nie/ → [nje].

This process is usually blocked after a complex onset of the form obstruent + liquid (a stop or a fricative followed by /l/ or /ʁ/). For example, while the pair loue/louer shows an alternation between [u] and [w], the same suffix added to cloue [klu], a word with a complex onset, does not trigger the glide formation: clouer [klue] (‘to nail’). Some sequences of glide + vowel can be found after obstruent-liquid onsets, however. The main examples are [ɥi], as in pluie [plɥi] (‘rain’), [wa], as in trois [tʁwa] (‘three’), and [wɛ̃], as in groin [gʁwɛ̃] (‘snout’).[52] They can be dealt with in different ways, as by adding appropriate contextual conditions to the glide formation rule or by assuming that the phonemic inventory of French includes underlying glides or rising diphthongs like /ɥi/ and /wa/.[53][54]

Glide formation normally does not occur across morpheme boundaries in compounds like semi-aride (‘semi-arid’).[55] However, in colloquial registers, si elle [si.ɛl] (‘if she’) can be pronounced just like ciel [sjɛl] (‘sky’), or tu as [ty.ɑ] (‘you have’) like tua [tɥa] (‘[(s)he] killed’).[56]

The glide [j] can also occur in syllable coda position, after a vowel, as in soleil [sɔlɛj] (‘sun’). There again, one can formulate a derivation from an underlying full vowel /i/, but the analysis is not always adequate because of the existence of possible minimal pairs like pays [pɛ.i] (‘country’) / paye [pɛj] (‘paycheck’) and abbaye [a.bɛ.i] (‘abbey’) / abeille [a.bɛj] (‘bee’).[57] Schane (1968) proposes an abstract analysis deriving postvocalic [j] from an underlying lateral by palatalization and glide conversion (/lj/ → /ʎ/ → /j/).[58]

| Vowel | Onset glide | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /j/ | /ɥ/ | /w/ | ||

| /a/ | /ja/ | /ɥa/ | /wa/ | paillasse, Éluard, poire |

| /ɑ/ | /jɑ/ | /ɥɑ/ | /wɑ/ | acariâtre, tuas, jouas |

| /ɑ̃/ | /jɑ̃/ | /ɥɑ̃/ | /wɑ̃/ | vaillant, exténuant, Assouan |

| /e/ | /je/ | /ɥe/ | /we/ | janvier, muer, jouer |

| /ɛ/ | /jɛ/ | /ɥɛ/ | /wɛ/ | lierre, duel, mouette |

| /ɛ̃/ | /jɛ̃/ | /ɥɛ̃/ | /wɛ̃/ | bien, juin, soin |

| /i/ | /ji/ | /ɥi/ | /wi/ | yin, huile, ouïr |

| /o/ | /jo/ | /ɥo/ | /wo/ | Millau, duo, statuquo |

| /ɔ/ | /jɔ/ | /ɥɔ/ | /wɔ/ | Niort, quatuor, wok |

| /ɔ̃/ | /jɔ̃/ | /ɥɔ̃/ | /wɔ̃/ | lion, tuons, jouons |

| /ø/ | /jø/ | /ɥø/ | /wø/ | mieux, fructueux, boueux |

| /œ/ | /jœ/ | /ɥœ/ | /wœ/ | antérieur, sueur, loueur |

| /œ̃/ | — | — | — | |

| /u/ | /ju/ | — | /wu/ | caillou, Wuhan |

| /y/ | /jy/ | — | — | feuillu |

StressEdit

Word stress is not distinctive in French, so two words cannot be distinguished based on stress placement alone. Grammatical stress is always on the final full syllable (syllable with a vowel other than schwa) of a word. Monosyllables with schwa as their only vowel (ce, de, que, etc.) are generally clitics but otherwise may receive stress.[36]

The difference between stressed and unstressed syllables in French is less marked than in English. Vowels in unstressed syllables keep their full quality, regardless of whether the rhythm of the speaker is syllable-timed or mora-timed (see isochrony).[59] Moreover, words lose their stress to varying degrees when pronounced in phrases and sentences. In general, only the last word in a phonological phrase retains its full grammatical stress (on its last full syllable).[60]

Emphatic stressEdit

Emphatic stress is used to call attention to a specific element in a given context such as to express a contrast or to reinforce the emotive content of a word. In French, this stress falls on the first consonant-initial syllable of the word in question. The characteristics associated with emphatic stress include increased amplitude and pitch of the vowel and gemination of the onset consonant, as mentioned above.[61] Emphatic stress does not replace, but occurs in tandem with, grammatical stress.[62]

- C’est parfaitement vrai. [sɛ.paʁ.fɛt.mɑ̃.ˈvʁɛ] (‘It’s perfectly true.’; no emphatic stress)

- C’est parfaitement vrai. [sɛ.ˈp(ː)aʁ.fɛt.mɑ̃.ˈvʁɛ] (emphatic stress on parfaitement)

For words that begin with a vowel, emphatic stress falls on the first syllable that begins with a consonant or on the initial syllable with the insertion of a glottal stop or a liaison consonant.

- C’est épouvantable. [sɛ.te.ˈp(ː)u.vɑ̃ˈ.tabl] (‘It’s terrible.’; emphatic stress on second syllable of épouvantable)

- C’est épouvantable ! [sɛ.ˈt(ː)e.pu.vɑ̃.ˈtabl] (initial syllable with liaison consonant [t])

- C’est épouvantable ! [sɛ.ˈʔe.pu.vɑ̃.ˈtabl] (initial syllable with glottal stop insertion)

IntonationEdit

French intonation differs substantially from that of English.[63] There are four primary patterns:

- The continuation pattern is a rise in pitch occurring in the last syllable of a rhythm group (typically a phrase).

- The finality pattern is a sharp fall in pitch occurring in the last syllable of a declarative statement.

- The yes/no intonation is a sharp rise in pitch occurring in the last syllable of a yes/no question.

- The information question intonation is a rapid fall-off from a high pitch on the first word of a non-yes/no question, often followed by a small rise in pitch on the last syllable of the question.

See alsoEdit

- History of French

- Phonological history of French

- Varieties of French

- French orthography

- Reforms of French orthography

- Phonologie du Français Contemporain

- Quebec French phonology

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Map based on Trudgill (1974:220)

- ^ a b c Fougeron & Smith (1993), p. 79.

- ^ a b c Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), p. 192.

- ^ Adams (1975), p. 288.

- ^ a b c Fougeron & Smith (1993), p. 75.

- ^ Phonological Variation in French: Illustrations from Three Continents, edited by Randall Scott Gess, Chantal Lyche, Trudel Meisenburg.

- ^ Wells (1989), p. 44.

- ^ Grevisse & Goosse (2011), §32, b.

- ^ Grevisse & Goosse (2011), §33, b.

- ^ Berns (2013).

- ^ a b Detey et al. (2016), pp. 131, 415.

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006), p. 42.

- ^ Fougeron & Smith (1993), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Tranel (1987), pp. 149–150.

- ^ Yaguello (1991), cited in Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:51).

- ^ Tranel (1987), p. 150.

- ^ Tranel (1987), pp. 151–153.

- ^ John C. Wells prefers the symbol /æ̃/, as the vowel has become more open in recent times and is noticeably different from oral /ɛ/: [1]

- ^ Walker (1984), pp. 51–60.

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006), pp. 25–6.

- ^ a b c d Fougeron & Smith (1993), p. 73.

- ^ a b Lodge (2009), p. 84.

- ^ a b c Collins & Mees (2013), p. 225.

- ^ Morin (1986).

- ^ Léon (1992), p. ?.

- ^ Kalmbach, Jean-Michel (2011). «Phonétique et prononciation du français pour apprenants finnophones». Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ «Some phoneticians claim that there are two distinct as in French, but evidence from speaker to speaker and sometimes within the speech of a single speaker is too contradictory to give empirical support to this claim».Casagrande (1984:20)

- ^ Postériorisation du / a / Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Tranel (1987), p. 64.

- ^ «For example, some have the front [a] in casse ‘breaks’, and the back [ɑ] in tasse ‘cup’, but for others the reverse is true. There are also, of course, those who use the same vowel, either [a] or [ɑ], in both words».Tranel (1987:48)

- ^ a b Fougeron & Smith (1993), p. 74.

- ^ a b c Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006), p. 33-34.

- ^ Hansen, Anita Berit (1998). Les voyelles nasales du français parisien moderne. Aspects linguistiques, sociolinguistiques et perceptuels des changements en cours (in French). Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-495-9.

- ^ Collins & Mees (2013), pp. 225–226.

- ^ Oral articulation of nasal vowel in French

- ^ a b Anderson (1982), p. 537.

- ^ Tranel (1987), p. 88.

- ^ Lindsey, Geoff (15 January 2012). «Le FOOT vowel». English Speech Services. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Lindsey, Geoff (22 August 2012). «Rebooting Buttocks». English Speech Services. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006), p. 59.

- ^ Timbre du schwa en français et variation régionale : un étude comparative retrieved 14 July 2013

- ^ Tranel (1987), pp. 88–105.

- ^ Casagrande (1984), pp. 228–29.

- ^ Anderson (1982), pp. 544–46.

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:63) for [e], TLFi, s.v. appellation for [ɛ].

- ^ Tranel (1987), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Walker (1984), pp. 25–27.

- ^ a b Walker (2001), p. 46.

- ^ Fagyal & Moisset (1999).

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006), p. 27.

- ^ Torreira & Ernestus (2010).

- ^ The [wa] correspond to orthographic ⟨oi⟩, as in roi [ʁwa] (‘king’), which contrasts with disyllabic troua [tʁu.a] (‘[he] punctured’).

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006), pp. 37–39.

- ^ Chitoran (2002), p. 206.

- ^ Chitoran & Hualde (2007), p. 45.

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006), p. 39.

- ^ Fagyal, Kibbee & Jenkins (2006:39). The words pays and abbaye are more frequently pronounced [pe.i] and [abe.i].

- ^ Schane (1968), pp. 57–60.

- ^ Mora-timed speech is frequent in French, especially in Canada, where it is very much the norm.[citation needed]

- ^ Tranel (1987), pp. 194–200.

- ^ Tranel (1987), pp. 200–201.

- ^ Walker (2001), pp. 181–2.

- ^ Lian (1980).

SourcesEdit

- Adams, Douglas Q. (1975), «The Distribution of Retracted Sibilants in Medieval Europe», Language, 51 (2): 282–292, doi:10.2307/412855, JSTOR 412855

- Anderson, Stephen R. (1982), «The Analysis of French Shwa: Or, How to Get Something for Nothing», Language, 58 (3): 534–573, doi:10.2307/413848, JSTOR 413848

- Berns, Janine (2013), «Velar variation in French», Linguistics in the Netherlands, 30 (1): 13–27, doi:10.1075/avt.30.02ber

- Casagrande, Jean (1984), The Sound System of French, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, ISBN 978-0-87840-085-0

- Chitoran, Ioana; Hualde, José Ignacio (2007), «From hiatus to diphthong: the evolution of vowel sequences in Romance» (PDF), Phonology, 24: 37–75, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.129.2403, doi:10.1017/S095267570700111X, S2CID 14947405

- Chitoran, Ioana (2002), «A perception-production study of Romanian diphthongs and glide-vowel sequences», Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 32 (2): 203–222, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.116.1413, doi:10.1017/S0025100302001044, S2CID 10104718

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2013) [First published 2003], Practical Phonetics and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students (3rd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-50650-2

- Detey, Sylvain; Durand, Jacques; Laks, Bernard; Lyche, Chantal, eds. (2016), Varieties of Spoken French, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19957371-4

- Fagyal, Zsuzsanna; Kibbee, Douglas; Jenkins, Fred (2006), French: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82144-5

- Fagyal, Zsuzsanna; Moisset, Christine (1999), «Sound Change and Articulatory Release: Where and Why are High Vowels Devoiced in Parisian French?» (PDF), Proceedings of the XIVth International Congress of Phonetic Science, San Francisco, vol. 1, pp. 309–312

- Fougeron, Cecile; Smith, Caroline L (1993), «Illustrations of the IPA:French», Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 23 (2): 73–76, doi:10.1017/S0025100300004874, S2CID 249404451

- Grevisse, Maurice; Goosse, André (2011), Le Bon usage (in French), Louvain-la-Neuve: De Boeck Duculot, ISBN 978-2-8011-1642-5

- Léon, P. (1992), Phonétisme et prononciations du français, Paris: Nathan

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996), The Sounds of the World’s Languages, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4

- Lian, A-P (1980), Intonation Patterns of French (PDF), Melbourne: River Seine Publications, ISBN 978-0-909367-21-3

- Lodge, Ken (2009), A Critical Introduction to Phonetics, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8264-8873-2

- Morin, Yves-Charles (1986), «La loi de position ou de l’explication en phonologie historique» (PDF), Revue Québécoise de Linguistique, 15 (2): 199–231, doi:10.7202/602567ar

- Schane, Sanford A. (1968), French Phonology and Morphology, Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, ISBN 978-0-262-19040-4

- Torreira, Francisco; Ernestus, Mirjam (2010), «Phrase-medial vowel devoicing in spontaneous French», Interspeech 2010, pp. 2006–2009, doi:10.21437/Interspeech.2010-568, hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-C810-3

- Tranel, Bernard (1987), The Sounds of French: An Introduction, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-31510-4

- Trudgill, Peter (1974), «Linguistic change and diffusion: Description and explanation in sociolinguistic dialect», Language in Society, 3 (2): 215–246, doi:10.1017/S0047404500004358, S2CID 145148233

- Walker, Douglas (2001), French Sound Structure, University of Calgary Press, ISBN 978-1-55238-033-8

- Walker, Douglas (1984), The Pronunciation of Canadian French (PDF), Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, ISBN 978-0-7766-4500-1

- Wells, J.C. (1989), «Computer-Coded Phonemic Notation of Individual Languages of the European Community», Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 19 (1): 31–54, doi:10.1017/S0025100300005892, S2CID 145148170

- Yaguello, Marina (1991), «Les géminées de M. Rocard», En écoutant parler la langue, Paris: Seuil, pp. 64–70

External linksEdit

- Foreign Service Institute’s freely downloadable course on French phonology

- Introduction to French Phonology (audio)

- Introduction to French Phonology (student & teacher texts)

- Large collection of recordings of French words

- mp3 Audio Pronunciation of French vowels, consonants and alphabet

- French Vowels Demonstrated by a Native Speaker (youtube)

- French Consonants Demonstrated by a Native Speaker (youtube)

In French, stress (l’accentuation) is placed on the final syllable of a word.

This is very different from the placement of stress in English which varies according to the word itself.

Notice that French stress falls on the last syllable whereas English stress may fall on any syllable

(word initial, word medial, or word final). This means that word stress is easily predicted (and learned!) in French.

| French | English | |

| NormanDIE | NORmandy | |

| MéditerranEE | MediteRRAnean | |

| AtlanTIQUE | AtlANtic | |

| CanaDA, canadiEN | CAnada, caNAdian | |

| PaRIS, parisiEN | PAris, paRIsian |

When words are strung together in French to form sentences, stress is placed on the final syllable of the phrase.

In a sense, French speakers treat a phrase like they treat a single word – they place the stress at the end.

In English, on the other hand, words retain their individual stress pattern when combined into sentences.

Compare the two languages:

| Je visite la cathéDRALE. |

| Je visite la cathédrale Notre DAME. |

| Je visite la cathédrale Notre Dame à PaRIS. |

| I’m VIsiting the caTHEdral. |

| I’m VIsiting the caTHEdral NOtre DAME. |

| I’m VIsiting the caTHEdral NOtre DAME in PAris. |

Listen and repeat.

| 1. | Je NAGE. | Je nage à la MER. | ||

| 2. | Je fais du SKI. | Je fais du ski dans les ALPES. | ||

| 3. | Je visite la BreTAGNE. | Je visite la Bretagne en voiTURE. | ||

| 4. | Je passe les vaCANCES. | Je passe les vacances à PaRIS. |

l’intonation

Good French pronunciation requires mastery of 3 elements: individual sounds (phonemes), stress placement, and intonation.

Intonation refers to the varying pitch levels of speech. Often referred to as the «melody» of a language,

intonation is associated with certain sentence types: declarative, exclamative, imperative, and interrogative (questions). Listen to each of the following examples and repeat.

Declarative Intonation

Short declarative sentences typically have a falling intonation.

| Il fait du soleil. |

| Il y a des nuages. |

Longer declarative sentences often have a rise then a fall.

Je préfère visiter un musée aujourd’hui.

Exclamative Intonation

Exclamative intonation is marked by a sharp fall in pitch.

| Quel beau chateau! |

| Quelle belle province! |

| Quelles vacances formidables! |

Imperative Intonation

Imperative intonation is similar to exclamative intonation—that is, a sharp fall at the end.

| Répétez! |

| Levez la main! |

| Ouvrez le livre! |

| Tournez à la page soixante-dix-neuf! |

Interrogative Intonation

Yes/No question are signalled by a sharp rise on the final syllable.

| Tu aimes la Provence? |

| Vous faites de la voile? |

| Est-ce que vous partez en vacances? |

Information questions begin with a high pitch on the question word (où, pourquoi, comment, etc.) and then gradually fall.

| Comment vous appelez-vous? |

| Qu’est-ce que vous faites dans la vie? |

Learn French from scratch!

Leçon 1

French Alphabet

Attention! The french alphabet is given to you in the first lesson only for a quick acquaintance because you will have to learn many french sounds first. That is what we are going to do during the next 12 lessons, and then we go back to the alphabet. These 12 lessons are called the introductory phonetic course. They do not include grammar which starts from lesson 13.

In the introductory course we will examine the French sounds, giving their approximate sound correspondence in the English language, if possible, and showing what French letters or letter combinations are used for each sound.

Sounds [а], [р], [b], [t], [d], [f], [v], [m], [n]

| French sound | Similar English sound | French letters and letter combinations | Notes |

| vowel [a] | like “ah” in English | А, а À, à |

The sign ` (a accent grave) is used to distinguish some words in writing, for example: а — to have; à — to (preposition) and other meanings. The capital letter À is more often denoted as A. |

| consonant [p] | [p] as in the word park | Р, p | Similar to English, except that in French, it’s not aspirated (no air is expelled) when it’s at the beginning of a word. |

| consonant [b] | [b] as in the word bar | В, b | |

| consonant [t] | [t] as in the word table | T, t Th, th |

Similar to English, except that its place of articulation is dental rather than alveolar. |

| consonant [d] | [d] as in the word debt | D, d | Similar to English, except that its place of articulation is dental rather than alveolar. |

| consonant [f] | [f] as in the word fact | F, f Ph, ph |

|

| consonant [v] | [v] as in the word vase | V, v W, w |

The letter W, w is rarely used, but it is pronounced as [v] in some loan words, for example, in the word warrant. |

| consonant [m] | [m] as in the word mother | M, m | |

| consonant [n] | [n] as in the word nine | N, n |

Exercise 1. Read aloud:

[ра — ba — ta — da — fa — va — ma — na].

Exercise 2. Write the transcription for a letter or a letter combination. Check yourself using the table above.

| T [] | f [] | t [] | F [] |

| d [] | p [] | à [] | a [] |

| A [] | B [] | b [] | ph [] |

| D [] | Ph [] | n [] | V [] |

| M [] | N [] | Th [] | P [] |

| m [] | v [] | th [] |

Like in English, consonant sounds at the end of words remain the same (unlike some other languages).

Exercise 3. Read aloud contrasting the final sounds:

[dap — dab], [рар — pab], [fat — fad], [tap — tab], [mat — mad].

If a word ends in the sound [v], then any stressed vowel

before it usually lengthens, for example [pa:v].

Colon in the transcription indicates the length of the vowel.

Exercise 4. Read aloud distinguishing the final [f] and [v]:

[paf — pa:v], [taf — ta:v], [baf — ba:v].

The letter е at the end of words. Stress in French. Clarity of french vowels

The letter е at the end of words in most cases is not pronounced, for example:

dame [dam] — lady, arabe [a’rab] — Arabic.

The stress in the French words falls on the last syllable, for example: papa [pa’pa] — dad. That is why it is not written in dictionaries and we will not write it in our transcription.

Unlike English, all the French vowels sound equally clear in both the stressed and the unstressed position, for example: panama [panama] — Panama [ˌpænə’mɑː].

All three French [а] are pronounced the same way, unlike English where we see three different “a”.

Exercise 5. Read aloud. Remember that the stress in French words always falls on the last syllable:

| banane [banan] — banana | papa [papa] — dad | |

| madame [madam] — madam, ma’am, Mrs. | Nana [nana] — Nana | |

| panama [panama] — Panama | (female name) |

Double consonants

Double consonants are pronounced as one sound, like in English, for example:

Anne [an] — Anna, batte [bat] — bat.

Exercise 6. Read aloud:

| date [dat] — date | patte [pat] — paw |

| datte [dat] — date (palm) | panne [pan] — breakdown |

| nappe [nap] — tablecloth | fade [fad] — tasteless; dull |

| natte [nat] — plait, braid | bave [ba:v] — spit, drool |

Sound [r]

| French sound | Similar English sound | French letters |

| consonant [r] | [r] as in the word red | R, r |

The sound [r] in Parisian pronunciation is considered to be one of the most difficult French sounds for English speakers. However, Paris is not the whole of France. The French “r” is a sound made in the back of the throat. In some cases it’s rather harsh and in others it’s softer, depending on the word and region of France. There is no shame if you are going to pronounce the French “r” like English “r”. You can learn French for fifteen or twenty years and still not quite get it. This shouldn’t be your primary focus when learning French.

In order to get your French “r” better, you need to lift up the back of your tongue to the roof of your mouth, just between your hard palate and your soft palate. It’s quite similar to the way you’d place your tongue to pronounce the sound [g] — so, you can start with that sound first. Then place a small “gargle” sound instead of the [g]. Your tongue might move back just a little bit. Remember, it’s the back of your tongue that should stick up! Not the front, like you do with the English “r.” The feeling is similar to gargling mouthwash, clearing your throat, or coughing up some… stuff… It’s better to practise.

Exercise 7. Read aloud:

| rate [rat] — spleen | rame [ram] — oar |

| arme [arm] — weapon, arm | parade [parad] — parade |

If a word ends in [r], then any stressed vowel before it usually lengthens, for example:

bar [ba:r] — bar, amarre [ama:r] — mooring rope.

Exercise 8. Read aloud:

| barbare [barba:r] — barbarian | phare [fa:r] — headlight |

| radar [rada:r] — radar | rare [ra:r] — rare |

| mare [ma:r] — pond, pool | avare [ava:r] — miserly |

Join our Telegram channel @lingust and:

Both English and French have in some broad sense the notion of «stressed» syllables, but they do it in different ways.

English has what is sometimes called lexical stress, i.e. the location of stress can be inherent in a particular word root and/or prefix/suffix. So, for example, the word «impotent» has a stress on the first syllable whereas «important» has a stress on the second syllable, and the position of this stress is essentially what defines the difference between these two words.

French to all intents and purposes doesn’t have this phenomenon of lexical stress.

In French, syllable stress essentially works at the phrase level: an utterance is divided up into ‘phrases’ of a few words in length, and the first and last syllable of each ‘phrase’ carry a stress. (Phonetically, there are differences in how precisely the first vs last syllable stress is realised, but I would suggest that’s not so vital at this stage.)

In addition, there are a few «function» words (e.g. «à», «de», «me», «le» etc) which don’t ordinarily carry stress. So when an utterance is being divided into phrases, these words cannot occur at the boundary of a phrase. For example:

Jean et Marie sont venus à huit heures moins le quart.

might be divided up as follows:

Jean et Marie sont venues | à | huit heures moins le quart.

where the syllables in bold carry a stress (and where «à» effectively sits outside any phrase).

There’s no hard-and-fast rule as to how the division into phrases is made, but as a general rule, more rapid speech will have fewer of these intonation «phrases». In more careful speech, you may end up with further division, e.g.:

Jean et Marie | sont venues | à | huit heures moins le quart.

Obviously, I’m glossing over a lot of details, but that’s a basic outline. If your library has or can get hold of it, check out the chapter on French in «Intonation Systems» by Hirst & Di Cristo for one way of modelling French intonation.

French is is often thought of as the language of love and romance. I don’t know if that is true, but one may say that the beauty of the French language comes from the diversity of its vowels, the right balance between vowels and consonants, and the monotony of its rhythm.

While this beauty may delight your ears, it also means complexity. French pronunciation has a lot of complex structures and irregularities. This guide will help you understand these nuanced structures, so you’re better equipped to face the adversities of learning how to speak French.

What This Guide Is About

Above all, this is a reference guide on French pronunciation. You will, most likely, not learn everything there is to learn in one shot. So feel free to bookmark this article and come back whenever you need it.

I will cover the multiple levels of pronunciations — namely segments (consonants and vowels), words and sentences.

This guide provides valuable content for learners on every level. Whether you are a beginner, intermediate or advanced, there is always something to learn.

Some parts of this article go more into greater detail than you may currently need. Feel free to skip an sections if you feel like this might be too advanced for you. Beginners need only the basics. Learn the foundations and circle back when you are ready. If you are an advanced learner, brush up on your basics and get ready to dive deeper.

What This Guide Is Not About

Again, this guide is not a one-shot read.

If you’re a coffee person, you may think of this guide as a nice shot of espresso. If you’re a tea person, enjoy this article like a cup of tea! Namely — slowly, or you might be burned out.

One important thing: do not get caught up in details. During my short life on this earth, I’ve had the opportunity to learn French, English, Turkish, German, Italian and Spanish (by order of mastery). One thing I’ve learned is not to fall into the trap of paralysis by analysis.

There are two extremes: people dedicating their lives to the intricacies of grammar without ever speaking and… the exact opposite.

This is NOT a grammar guide, but the same holds true for pronunciation. Both are sets of rules. Be aware of them, but do not learn them by heart (unless you have to). Let the exposure to the language be your teacher. Internalize the rules over time.

Alphabet: Sounds of the French Alphabet

French and English have the exact same alphabet, namely 26 letters of which six orthographic vowels and 20 orthographic consonants (meaning that these letters each refer to a sound).

French orthography is not easy. As you probably already know, French has a specific set of rules one has follow in order to read it. While Spanish is pretty straightforward, you’ll see that we French like to make things «a tiny bit more complex».

There are more consonants and vowels than the individual letters of the alphabet. Here come the letter combinations that will produce extra sounds… or sometimes the same ones, but in a fancier way.

Without further ado, here is the French alphabet.

a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z

I recommend you listen to the pronunciation of the whole alphabet here.

Note: Contrary to what you might think “é”, “è” or even “ç” are not different letters. We will later see that they appear in specific contexts.

How to Pronounce Vowels

Although Spanish and French both come from Latin, history has made them quite distinct. As I mentioned above, one of these distinctions is the use of letters. In Spanish, it is safe to say that one letter corresponds to a single sound. Forget that for French! Different combinations of letters result in different sounds.

It might sound scary at the beginning, but it’s really not. English is similar in many cases. Actually, it’s even worse in English; in English, the same letter combinations might produce different sounds. Classic example: through vs. though.

Now there are exceptions in French as well and sometimes the same letter combinations are pronounced differently (examen, entrée). However, these exceptions are less frequent.

What Is a Vowel?

I was trained as a linguist. I like the nerdy aspect of languages. However, I will try to provide only information that is useful to you.

If I were to ask you the definition of a vowel, what you do you say? Pretty tricky, right?

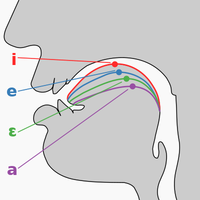

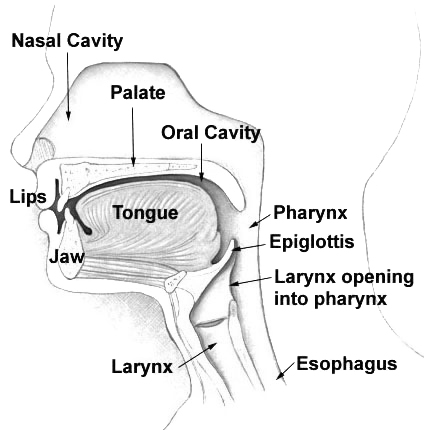

A vowel is a sound of language made with the free flowing of air through the mouth. That means you do not block the air in your mouth when pronouncing a vowel. For the sake of this guide, let’s say there are two main organs involved in the making of a vowel: the tongue and the lips.

Take a look at the following picture:

You can see from the picture that three factors influence the sound of a vowel:

- Height (how high your tongue is)

- Backness (how far back your tongue is)

- Roundedness (of the lips)

How is this useful? You obviously don’t need to learn this stuff by heart. However, you can use this knowledge and apply it to what you already know. This way, in order to make new sounds, you can use the sounds you’re already familiar with and from there adjust the position of your tongue to pronounce them like a native!

Note: In this article, you won’t encounter any atrocities such as “here’s the sound “i” like in “tree””. It’s just not accurate. Every language has different sounds, some of which cannot be “transferred” from one to another. Instead, I will refer to links to this website for each sound so you can hear it.

Individual letters

In French, the single letters «a, e, i, o, u» all refer to a single respective sound. However, these sounds are all different from the English ones.

Note: «y» is considered a vowel. It is true to the extent that it is sometimes pronounced as «i» (the French version). In other cases, it as the same function as in English.

«a» as in “oh la la!”

papa (dad), patte (animal’s leg), bas (low)

Example #1:

«Je m’appelle Jack» (My name is Jack)

Example #1:

«Quel âge as-tu» (How old are you?)

The French «a» sound is the same as the one in Spanish.

The English “a” (as in «cat») is made with the tongue pulled forward. It is almost the same sound in French, except the tongue is placed a bit lower.

Exceptions: In certain cases, you can find the “a” sound in different forms.

là, femme, violemment

Nothing to worry about though. These cases are rare and very predictable. “Là” and “femme” you can learn by heart. In other cases, “e” + “mment” will result in a “a” sound.

The “e” sound

Why is there no example up front? Because this one is tricky and the letter «e» actually refers to (at least) two different sounds.

The closed «e»

There is (at least) two kinds of «e». The first is called the closed «e», with an «accent aigu» (acute accent).

It is pronounced the Spanish way in words like these:

béton, piéton, héros

Example #1:

«Bien joué !» (Well done!)

Example #2:

«Je suis infirmier» (I am a nurse)

The reason this sounds has an acute accent on it is to indicate that it is pronounced with the mouth slightly closed.

The open «e»

The second one is the open “e”, with an «accent grave» (grave accent) because it is pronounce with the mouth open.

père, frère

This sound will also occur before two double consonants. As we see in these examples:

Example #1:

«Comment t’appelles-tu?» (What is your name?)

Example #2:

«Le sport m’intéresse» (I’m interested in sports)

“e” + “ll” will result in the “accent grave”/closed type of “e”.

The circomflex «ê» is also a closed «e».

tête, fête, bête

Everywhere else: When not specified, the “e” sound will be open, such as in:

nerf, cerf, serf

The Silent «e»

Remember these previous examples?

tête, fête, bête, père, frère

The «e» in final position is never pronounced. Unless you either are reading poetry or want to have a southern French accent.

Rather, the final «e» in French is here to indicate that you must pronounce the preceding consonant. In other words, if we take the imaginary word «têt» (from real word «tête»), the final consonant would be silent.

“i” as in “chic”

dix, lit, île

Example #1:

«Je suis infirmier/infirmière» (I am a nurse)

Example #2:

«Je suis très riche» (I am very rich)

This is an easy one. In French the “i” sound is always pronounced as in “chic” or “petite”.

There is one caveat however. As we saw earlier, vowels are always short in French. As a result there is no distinction between examples like “(to) live” and “leave”. This is why French people have a hard time differentiating “beach” and… well the other word.

So in order to pronounce the “i” sound, you will do a shorter version of the English “ee” sound.

Note: In the previous example, you might have noticed the “î” with a circomflex. This hides a lost “s” that is not pronounced anymore (example in English: island). This does not change the pronunciation.

Exceptions: You will encounter the following cases:

style, y

These are just regular “i” sounds.

The «o» sound

This one is less easy. There are two kinds of “o” sounds, just like “e”. There is a open and a closed one. This time, however, there is no accent to tell the difference. But hold on, it’s not as difficult as it sounds!

The closed «o»

First, we have the closed “o”.

Ado, chrono, opéra

Example #1:

«Quelle est ta couleur favorite ?» (What is your favorite color?)

Example #2:

«Je viens de Los Angeles» (I’m from Los Angeles)

Why do these words not look French at all? You won’t find many short words in French featuring «o» letters. Why? I don’t know, we like to complicate things. You will see in a further section that “o” can also appear as “au” and “eau”. These patterns actually appear more often.

The closed “o” will appear at the end of a syllable (if there is no pronounced consonant).

Note: This sound is not made the British or American way. This is a single sound. Your lips do NOT move!

The open «o»

Secondly, we have the open “o”, as in these examples:

Example #1:

«Il fait beau dehors…»(the weather is good outside)

Example #2:

«Où est ton ordinateur portable»(Where is your laptop?)

The open «o» appears in specific contexts, such as:

Case #1: «o» is followed by a final consonant (other than “s”) as in:

frotte (rub), sotte (stupid-FEM), glotte (glottis)

Note: the «tt» counts phonetically as one consonant.

Case #2: «o» is followed by two consonants (other than two “s”’s) as in:

porte, ordinateur, portable

Note: This sound will not be represented by letter combinations such as “au” and “eau”.

“u” as in “déjà vu”

This one is really tricky for English speakers. This is not the regular “u” sound you can find in every language. Again, we like to complicate things.

déjà vu, flûte (flute), zut (oops)

Example #1:

«Comment t’appelles-tu?» (What is your name?)

Example #2:

«Es-tu célibataire?» (Are you single?)

The trick is to pronounce an English “u” and then bring your tongue forward. You’ll get it with practice!

Exceptions are very rare. Examples are:

eu, aigüe

The former is very common so you’ll remember easily. The second one is too specific (and not that common) for me to explain it here.

Letter combinations

French has 14 vowels. That is more vowels than most languages have. Spanish for example has only 5. You can see that it is a huge number.

There are only six vowels in the alphabet. To solve this problem, French had to combine letters with each other. And now, you have to learn these combinations!

“ou” as in “en route”

You thought we didn’t have a proper “u”? We do!

route, goût (taste), nous (we)

Example:

«Ma couleur favorite est le rouge.» (My favorite color is red.)

Again, there is no long vowel in French. So the thing is to (again) make a long “u” English sound as in “route” but to keep it short.

There are very few exceptions in which «u» is actually pronounced «ou». But these words have foreign origins.

“eu” as in “queue”

As you can see, we do not pronounce this sound as in “cue”. More examples:

queue (tail), feu (fire), feutre (felt pen)

Example:

«Non elle est bleue» (No, it is blue)

We could say this is a closed “eu”. The rule is that it always appears in a open vowel (with no subsequent consonant) in a word.

“eu” as in “chef d’oeuvre”

Another one? Yep.

oeuvre, beurre, soeur

Example:

«Je suis professeur» (I am a teacher)

As you see, this “eu” can appear as both “eu” and “oeu”. It always appears in a closed syllable (with at least one consonant at the end).

“au” and “eau”

I mentioned these two sounds earlier. This is also a form of the “o” sound. Oddly enough they are also words in and of themselves.

au (to the), eau (water), auto (automobile), bâteau (boat)

Example:

«Il fait beau aujourd’hui» (The weather is nice today)

The Nasal Sounds

French is probably known for this. While most languages of the world feature sounds from the oral cavity exclusively, French uses the nasal cavity as well.

English actually does too, but only with consonants. How do you sound when you have a cold? Your “n”’s become “d”’s and your “m”’s become “b”’s. That’s because the “n”/»m» sounds are made with air coming out of the nasal cavity.

The same thing happens with vowels. We French people like to talk with our noses. We make those vowels by pronouncing them from the nose. Nasal vowels are tricky at the beginning, but you’ll get use to it with practice.

“an” as in “restaurant”

You can listen to it here.

restaurant, banc (bench), flanc (kind of pie)

Example #1:

«J’ai trente ans» (I’m thirty years old)

Try pronouncing the “an” from the English “restaurant”. Then get rid of the “n”.

This sound is also realized as “en”:

cent (hundred), lent (slow), enfant (child)

Example #2:

«Elle habite au centre ville» (She lives downtown)

It will usually be realized as “am” or “em” with a subsequent “p” or “b”:

ampoule (light bulb), empathie (empathy), ambiance (vibe)

Most of these words are transparent though and shouldn’t cause too much difficulty.

«in» as in «Hein??»

French people will say «hein?» whenever they don’t understand what you say. This sound can have many forms, namely:

“in”, “im”, “ein”, “ain”, “en”

I admit, this one is really tricky. You have to learn them by heart. Notice that “en” can also be realized as in “in” (examen).

fin, impossible, plein, pain, examen

Example #1:

«Es-tu ingénieur ?» (Are you an engineer?)

Example #2:

«Es-tu Américain ?» (Are you an American?)

Oddly enough, you can pronounce it when you exaggerate the pronunciation of “can’t” or “and”. Then only pronounce the vowel. Then slightly lower your palate.

“on” as in “garçon”

You can make this sound by first making a French “o” (remember, don’t move the lips) then by making the air flow from your nose.

garçon, chignon, champignon (mushroom)

Example:

«Où est ton ami ?» (Where is your friend?)

For a start, the American “don’t” is close enough.

Semi-Consonants: Between Vowels and Consonants

You haven’t got enough? There are also sounds which are technically between vowels and consonants. Nothing too alarming though, you also have them in English, namely “w” and “y”.

I will not cover “y” or “i” as in “Pierre” because every English speaker already knows how to do it.

“ou” as in “oui”

oui, Louis, fouet (whip)

This is just a “w” sound. When you find “ou” in front of another vowel, the “ou” sound will become a “w”. Pretty simple.

“ui” as in «huit»

Huit (eight), nuit (night), puits (well)

Another tricky one. The thing is to first make a “u” sound (not the English “u”, look up if you’ve already forgotten). Then do a “w” sound but keeping the tongue forward. You’ll get it right with a bit of training!

How to Pronounce Consonants

There are two challenges regarding consonants for English speakers: the French «r» and silent consonants. The rest is pretty much the same as in English. However, I will cover most of what works similarly in English and also the peculiarities of French consonants.

Before getting started

Before we start, I would like to clarify two things that will make everything else easier.

-

Unlike in Italian, double consonants such as «tt», «ss», etc. are always pronounced as single consonants. There is no emphasis.

-

In English, consonants like “p”, “t” and “k” are sometimes aspirated. We do NOT do that in French. That’s one of the reasons French people typically say “appy” instead of “happy”.

Let’s start with the easy stuff.

Individual letters

I have good news before we start. The following consonants are identical in both English and French. Therefore, there is no need to cover them.

b, d, f, m, n, v, w, x, y, z

For other consonants, you will see that they can be pronounced differently in different contexts. Moving on to the hard stuff.

“c” as in “café” or “cinéma”

“c” will be realized as a “k” in front of:

a, o, u, ou, an, on

and as a “s” in front of:

e, i, in, en

For concrete applications:

café, camping, cinéma, cent

Example #1 («c» as in «café»)

«Lulu préfère le thé au café» (Lulu prefers tea over coffee)

Example #1 («c» as in «cinéma»)

«Nous allons au cinéma» (We’re going to the movies)

Did you know? If you really want to get geeky on this, there is a reason why there is a shift of consonant with different vowels. See, the «s» sound is made with the tongue on the front of your palate. The «k» sound is made with the tongue on the back of the palate. What’s do «a, o, u» and «e, i» have in common? The former are made from the back while the latter is made from the front of the mouth. To make it easy on your tongue, our brains figured out a way to make the process easier. But we kept the same letter!

The «ç» (c cédille)

Take these words:

garçon, glaçon, ça

The «c» sound is pronounced here as «s». What did we say about «c» followed by «a», «o», etc? That’s why there is a cedilla on the «c», to turn it into a «s» sound.

Example

«Oui, ça va» (Yes, I’m fine)

In the old days, we used to say «garce» for girl and we still say «garçon» for boy (not for waiter). You can clearly see that the root of the word is «garc», so there is no reason to write it with an «s». That’s where the «ç» comes from.

“g” as in “garçon” or “girafe”

Same rule applies here: “g” in front of “a”, “o”, “u”, “ou”, “on”, “an”;

and as a “j” in front of “e”, “i”, “en” and “in”.

garçon, gourmet, giraffe, géant

Example #1:

«Elle regarde la télévision» (She’s watching TV)

Note: g + u will always result in “g” as in:

gui, guet, guillotine

Example #2:

«Je suis allergique» (I’m allergic)

“h” as in … nothing

I was tempted to write “h” as in “appy”. Simply put: we do not pronounce the letter h. Ever.

Hâche, hachis parmentier, haute couture

“j” as in “joie de vivre”

In English, “j” is pronounced with a “d” sound. Not in French. Only the last part is kept.

Je, joie, joli

See section on “g” to see when “g” is pronounced “j”.

«q» as in «bouquet»

Orthographically, the letter «q» is used exactly the same as in English. It is almost always found with a subsequent «u» as in:

bouquet, quête (quest), roquette (rocket)

In English, it is often pronounced «kw». It is simply pronounced «k» in French.

Two exceptions, but same sound:

Qatar, coq (cock)

The notoRRRious «r»

This is hands down the most difficult sound you will encounter in French. If you’re familiar with (Standard) German, you already know how it sounds.

If you’re an experienced gargler, you’ll know that there is something hanging at the back of your mouth. This is called the uvula.

What makes this strange «r» sound is the vibration of the uvula against the roof of your mouth. Hence this special sound you make when you gargle.

The key is to train yourself to make this sound by exaggerating it. Do the gargle sound and then slowly apply to a more light «r».

«s» as in «misérable»

You probably already know how to make a «s» sound. I will only cover the exception to the rule.

laser, phrase, misérable

Example:

«Je n’écoute pas de musique» (I don’t listen to music)

This is simple: «s» will be pronounced «z» between

two vowels.

Note: On the other hand, the «s» will be doubled (as in «ss») when pronounced as a real «s» sound.