Teachers frequently debate this question: What’s the difference between a root, base word, and stem? The reason teachers are forced to debate this question is that their textbooks present a model that quickly falls apart in the real world.

If teachers are confused, their students will also be confused. By the end of this page, you won’t be confused. To end this confusion, we will look at two systems:

1. The Traditional Root and Base-Word System for Kids

2. A Modern System of Morphemes, Roots, Bases, and Stems from Linguistics

The Traditional Root and Base-Word System for Kids

Here is a problem-filled system that, unfortunately, some students still learn.

Students learn that ROOTS are Greek and Latin roots. Most of these roots cannot stand alone as words when we remove the prefixes and suffixes.

Q e.g., Word: justify Latin Root: jus (law)

Students also learn that BASE WORDS can stand alone as words when we remove all of the prefixes and suffixes. Students learn that if it cannot stand alone when we remove all of the prefixes and suffixes, then it is not a base word.

Q e.g., Word: kindness Base Word: kind

The problem comes later in the day when the teacher is teaching verb tenses.

Q Teacher: Look at these two verbs: responded and responding. What’s the base word?

Q Student #1: Respond.

Q Teacher: Correct!

Q Student #2: Isn’t re- a prefix? If re- is a prefix, then respond can’t be a base word. I suspect that spond is a Latin root. Is it?

Q Teacher: I’m not sure. Let me research this. Yes, the word respond has the prefix re- attached to the Latin root spond. The Latin root spond comes from sponder, which means to pledge.

Although the teacher was looking for the answer “respond,” Student #2’s answer was the correct answer according to this Traditional System. That’s how easily the Traditional System falls apart. And the problems get worse from here.

Are you an elementary or middle school teacher? Have you taken a look at Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay on the homepage?

Modern Linguistics

I looked at a few current student textbooks from major publishers, and most of them don’t mention the terms base or base word. They only use the term root in their basic word studies. I suspect that this is because modern linguistics has created a new meaning for the term base.

In case you are not aware, modern linguistics and modern grammar fix many of the broken models from centuries past—i.e., models and definitions that quickly fall apart when you question them. These days, most books on linguistics and morphology present a somewhat standardized model. In English Word-Formation (1983), Laurie Bauer explains this model succinctly and definitively. Let’s take a look.

English Word-Formation (1983) by Laurie Bauer

As you can see below, Bauer acknowledges the root/stem/base problem and then explains a model that removes the ambiguity.

The Problem: “‘Root’, ‘stem’ and ‘base’ are all terms used in the literature to designate that part of a word that remains when all affixes have been removed. Of more recent years, however, there has been some attempt to distinguish consistently between these three terms.”

Root: “A root is a form which is not further analysable, either in terms of derivational or inflectional morphology. It is that part of word-form that remains when all inflectional and derivational affixes have been removed… In the form ‘untouchables’ the root is ‘touch’.”

Stem: “A stem is of concern only when dealing with inflectional morphology. In the form ‘untouchables’ the stem is ‘untouchable’.” [In short, when you remove the inflectional suffixes, you have the stem.]

Base: “A base is any form to which affixes of any kind can be added. This means that any root or any stem can be termed a base… ‘touchable’ can act as a base for prefixation to give ‘untouchable’.”

This model holds up across the curriculum. This model is the foundation of what I teach my students.

My Perfect Model: Roots, Stems, and Bases

I always like to have a complete model in mind that holds up across the curriculum. This lets me find teaching moments and ensures that I can answer my students’ questions clearly and consistently. Although I may not teach my students the entire model, at least the concepts are straight in my mind.

For this reason, I created this “Perfect Model of Roots, Stems, and Bases.” To be clear, this model is an interpretation and fuller explanation of what you might find in a linguistics book. Let me explain it to you. It all begins with morphemes.

Keep in mind that teachers don’t need to teach their students this entire model. In fact, most teachers will want to keep their morphology lessons simple and focus on roots, prefixes, and suffixes. But all teachers will want to understand this entire model.

Do you teach beginning writers or struggling writers? If you do, be sure to check out Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay on the homepage! It is the fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph writing… Guaranteed!

Morphemes

The term morpheme unifies the concepts of roots, prefixes, and suffixes, and therefore, it is an extremely valuable word. In short, words are composed of parts called morphemes, and each morpheme contributes meaning to the word. Morphemes are the smallest unit of language that contains meaning. Roots, prefixes, and suffixes all have one thing in common—they are all single morphemes. In contrast, stems and bases can be composed of one or many morphemes.

Root / Root Morpheme

When I use the term root, I always mean the root morpheme. The root is always the main morpheme that carries the main meaning of a word. Since a morpheme is the smallest unit of language that contains meaning, we can’t divide or analyze the root morpheme any further. Although a root can be a stand-alone word, to avoid confusion, I never use the term “root word.” I use the term root, and I use the term root morpheme to reinforce what a root is.

We have two types of root morphemes:

1. Dependent (bound) Roots: These roots cannot stand alone as words. These roots are usually Greek and Latin roots. Here are a few examples:

-

- liberty root: liber (free)

- interrupt root: rupt (break)

- similar root: sim (like)

2. Independent (free) Roots: These roots are stand-alone words. Practically speaking, these roots are almost always single-syllable words. You know the ones. It seems to me that most multi-syllable words can be further divided and further analyzed. With a little research, one finds that an ancient prefix or suffix has merged with a root. In short, most multi-syllable words are not root morphemes.

Here is what they thought 150 years ago. Although modern linguistics does not agree with these statements, it’s still food for thought. My point is that most of the independent roots that we deal with inside of the classroom are single-syllable words.

Q “All languages are formed from roots of one syllable.” – New Englander Magazine (1862)

Q “All words of all languages can be reduced to one-syllable roots.” – New Jerusalem Magazine (1853)

Here are a few examples:

-

- replaced root: place

- mindfulness root: mind

- carefully root: care

The Terms: Dependent Root and Independent Root

Modern linguistics use the term bound (for dependent) and free (for independent) to classify morphemes. Since teachers spend so much time teaching students about dependent clauses and independent clauses, I transfer this knowledge and terminology over to morphemes. Put simply: independent morphemes CAN stand alone; dependent morphemes CAN’T stand alone.

Q PREFIXES and SUFFIXES are almost always dependent morphemes—i.e., they can’t stand alone as words.

Q ROOTS are either dependent or independent morphemes.

Now, we will examine words that contain one root and words that contain two roots. As you examine these words, pay special attention to the dependent root and independent root aspect.

One Root: Many words have just one root. That one root may be a Dependent Root or an Independent Root. Remember, the root carries the main meaning of the word.

Q Word: justify Dependent Root: jus

Q Word: kindness Independent Root: kind

Two Roots: Some words have two roots. The roots may be Dependent Roots or Independent Roots. With two roots, each root contributes near equal meaning to the word.

Two Dependent Roots

Q Word: geography Dependent Root: geo (earth) Root: graph (write)

Q Word: carnivore Dependent Root: carn (flesh) Dependent Root: vor (swallow)

Q Word: cardiovascular Dependent Root: cardi (heart) Dependent Root: vas (vessel)

Two Independent Roots

Q Word: bathroom Independent Root: bath Independent Root: room

Q Word: downfall Independent Root: down Independent Root: fall

Q Word: popcorn Independent Root: pop Independent Root: corn

Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay! Put simply, it works.

Stem

I use the term stem just as Bauer does. To find the stem, simply remove the inflectional suffixes. It’s that simple.

When to Use the Term Stem: The term stem is quite unnecessary in many classrooms, as all stems are bases. For this reason, teachers can always use the term base instead of stem. However, the concept of stems is helpful in teaching students about inflectional suffixes. Inflectional suffixes are different from derivational affixes (derivational prefixes and derivational suffixes).

Q Word: reddest Stem: red

Q Word: girls’ Stem: girl

Q Word: boats Stem: boat

Q Word: preapproved Stem: preapprove

Q Word: justifying Stem: justify

Q Word: responded Stem: respond

Q Word: unjustifiable Stem: no stem

Q Word: kindness Stem: no stem

Base / Base Word

Bauer says, “A base is any form to which affixes of any kind can be added. This means that any root or any stem can be termed a base.”

In the table below, I use two labels to show how base and root relate to each other. Sometimes a base is a root (marked Q Base/Root), and sometimes it is not a root (marked Q Base).

To be clear, we can add a prefix or suffix to every base even if it already has a prefix or suffix. Furthermore, if we can add a prefix or suffix to something, we can call it a base.

Word: reread Q Base/Root: read

Word: unhelpful Q Base: helpful Q Base/Root: help

Word: justifying Q Base: justify Q Base/Root: jus

Word: unreliable Q Base: reliable Q Base/Root: rely

Word: preponderance Q Base: ponderance (uncommon) Q Base/Root: ponder

Word: responded Q Base: respond Q Base/Root: spond

Word: preapproved Q Base: preapprove Q Base: approve Q Base: approved Q Base: proved Q Base/Root: prove

Base vs. Base Word: To keep things simple, teachers should probably strike the term “base word” from their vocabulary. However, if the base is a complete word that can stand alone, teachers may choose to (or through force of habit) refer to it as a base word. If the base can’t stand alone, be sure not to call it a base word.

When to Use the Term Base: The term base is somewhat of a generic term for when we are not interested in or concerned with the root morpheme. As an example, we may choose to use the term base when we are ADDING prefixes and suffixes. When we are adding prefixes and suffixes, we often are unconcerned with finding or discussing the root morpheme. (Remember, we often add prefixes and suffixes to words that already contain prefixes and suffixes.) We may also choose to use the term base when removing a single, specific prefix or suffix, as the word may still contain other prefixes or suffixes.

Putting It All Together

Here is a table to help get you started in your word analysis studies related to root, stem, and base.

| Example Word | Stem | Root: Dependent | Root: Independent | Base |

| 1. undeniable | deny ** | deny; deniable | ||

| 2. reinvented | reinvent | ven/vent | ven/vent; invent; reinvent | |

| 3. deforestation | forest *** | forest; forestation | ||

| 4. interacted | interact | act * | act; interact | |

| 5. demographics | demographic | demo | graph * | demo; graph; demographic |

| 6. responding | respond | spond | spond; respond | |

| 7. preserving | preserve | serv | serv; preserve | |

| 8. hopefully | hope | hope; hopeful |

The Asterisks: The asterisks may be the most important part of this table. They help illustrate that every word has a unique history that often makes analysis and classification complicated and debatable.

* act and graph are also Latin roots

** deny is from Latin denegare = de (away) + negare (to refuse; to say no); since deny technically

has a Latin prefix (de-), you may choose to classify the word differently.

*** forest is from Latin foris meaning outdoors, and unlike the word deny, cannot be analyzed as

having a prefix or suffix attached.

I thought to quote from two websites that aided me, but to facilitate reading, I edit slightly and eschew blockquotes (>). The first quote is written with plainer and simpler diction and so ought to be read before the second with more formal diction.

1 of 2 quotes

Bases, stems, and roots are the main components of words, just like cells, atoms, and protons are the main components of matter.

In linguistics, the words «roots» is the core of the word. It is the morpheme that comprises the most important part of the word. It is also the primary unit of the family of the same word. Keep in mind that the root is mono-morphemic, or made of just one «chunk», or morpheme. Without the root, the word would not have any meaning. If you take the root away, all that you have left is affixes either before or after it. Such affixes do not have a lexical meaning on their own.

An example of a root is the word «act».

Now let’s look at what is a stem and a base and apply them to the root «act» so that you can see how they differ and interconnect to transform a lexical word altogether.

The stem occurs after affixes have been added to the root, for example:

Re-act ↝ Re-act-ion

Hence a stem is a form to which affixes (prefixes or suffixes) have been added. It is important to differentiate it from a root, because the root alone cannot be applied in discourse, whereas the stem exists precisely to be applied to discourse.

A base is the same as a root except that the root has no lexical meaning while the base does: «to act» is the infinitive of «act» and is structured with the base «act». In many words in our language, a word can be all three: a root, base, and stem (eg: «deer»). They differ in how they are applied during discourse (stem, base) and whether, on their own, they have any lexical meaning (stem, base) or no lexical meaning whatsoever (root).

An example of root, base and stem joined together is the word «refrigerator»:

The Latin root is frīg, which has no meaning in English on its own, and which requires a change in spelling for suffixes.

⟹ refrigerāre = Latin prefix + root + suffix, with no meaning in English of its own yet.

⟹ re- + friger + -ate + -tor = prefix + root + 2 suffixes.

The 2 suffices now produce lexical meaning = stem; spelling changes are required for suffixes.

[The links included with the answer contain the Glossary of Linguistic Terminology for further information.]

Sources: http://www-01.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/WhatIsABoundRoot.htm

http://www-01.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/WhatIsAStem.htm

2 of 2 quotes

Root, stem, base

Taken from: […] English [W]ord-[F]ormation […] by Laurie Bauer, 1983 (published by Cambridge University Press).

‘Root’, ‘stem’ and ‘base’ are all terms used in the literature to designate that part of a word that remains when all affixes have been removed.

A root is a form which is not further analysable, either in terms of derivational or inflectional morphology. It is that part of word-form that remains when all inflectional and derivational affixes have been removed. A root is the basic part always present in a lexeme. In the form ‘untouchables’ the root is ‘touch’, to which first the suffix ‘-able’, then the prefix ‘un-‘ and finally the suffix ‘-s’ have been added. In a compound word like ‘wheelchair’ there are two roots, ‘wheel’ and ‘chair’.

A stem is of concern only when dealing with inflectional morphology.

In the form ‘untouchables’ the stem is ‘untouchable’, although in the form ‘touched’ the stem is ‘touch’; in the form ‘wheelchairs’ the stem is ‘wheelchair’, even though the stem contains two roots.

A base is any form to which affixes of any kind can be added. This means that any root or any stem can be termed a base, but the set of bases is not exhausted by the union of the set of roots and the set of stems: a derivationally analysable form to which derivational affixes are added can only be referred to as a base. That is, ‘touchable’ can act as a base for prefixation to give ‘untouchable’, but in this process ‘touchable’ could not be referred to as a root because it is analysable in terms of derivational morphology, nor as a stem since it is not the adding of inflectional affixes which is in question.

Complex

words such as annotation,

builder, professor,

and others have internal structure. It is necessary not only to

identify each component of the morphemes but also to classify them

according to their contribution to the meaning and function of

complex words. Typically, complex words consist of a root

and one or more affixes.

The root constitutes the core of the word and carries the major

component of its meaning. Roots belong to a lexical category such as

noun (N), verb (V), adjective (Adj), adverb (Adv), and preposition

(P). Unlike roots, affixes are bound morphemes, and they do not

belong to a lexical category. Affixes are subdivided into prefixes

and suffixes. For example, when the suffix –er

combines with the root

build,

the noun builder is

coined to denote ‘one who builds.’ The internal structure of

this word can be shown in a diagram, which O’Grady,

Archibald, Aronoff, and Rees-Miller call “a tree structure” (p.

135). When an affix is attached to the root, the form is called a

base

or a stem

(The terms base

and stem

may be used interchangeably). Sometimes a base

corresponds to the

word’s root;

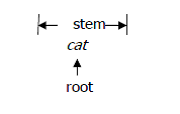

for example, in cat,

the root is cat,

and it is also a base.

4.2.3 Stems

A stem

is the actual form to which an affix (a suffix or a prefix) is added.

In blacken,

for example, the affix -en

is added to the root black.

Sometimes, an affix can be added to the form, which is larger than a

root, e.g., authorization

(n).

4.2.4 Types of affixes

We can distinguish three types of

affixes in terms of their position relative to the stem. An affix,

which is attached to the front of the stem, is called a prefix, and

an affix,

which is attached to the end of the stem, is called a suffix.

Some English prefixes and

suffixes

|

Prefixes |

Suffixes |

|

de+base de+cease dis+prove im+part im+bibe in+tone inter+fere in+trepid pre+fix pre+judge pre+side |

employ+ment enjoy+ment frang+ible frenz+y fulmin+ate gorge+ous grate+ful hunt+er nation+al+ize profess+or prob+ation |

A

less common type of affix is an infix,

which occurs within another morpheme. Although it is common in some

languages, in English it appears with expletives, which provide extra

emphasis to the word. One might point to certain usages on the

American frontier such as guaran-damn-tee

, abso-bloody-lutely,

and others.

4.2.5 Derivational and Functional Affixes

Functional affixes serve to

convey grammatical meaning. They build different forms of one and

the same word. Instead of creating a new word, functional affixes

modify the form of the word in order to mark the grammatical subclass

to which it belongs. A word form is defined as one of the different

aspects a word may take as a result of inflection. Complete sets of

all the various forms of a word when considered as inflectional

patterns, such as plurality, declension and conjugation, are termed

paradigms. A paradigm is defined as the system of grammatical forms

characteristic of a word, e.g., work, work+s, work+ing, and work+ed.

Plurality inflection

|

Singular |

Plural |

|

computer judge country dress fox buzz fly |

computer+s judge+s countr+ies dresses foxes buzzes flies |

Tense Inflection

|

Present |

Past |

|

play rule cry fix kiss dress |

played ruled cried fixed kissed dressed |

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

April 2, 2012 by wiegecko

Steam, Base, and Root

- Root

Root is the irreducible core of a word, with absolutely nothing else attached to it. Roots can be free morpheme or a word element which the other new words grow, usually through addition prefixes and suffixes.

Example : unhappy, root : happy.

- Steam

Steam is a word element to which grammatical or inflectional suffixes can be added. Every word that end with inflectional suffixes, we called it ‘steam’.

Inflectional suffixes :

- –s (plural)

- –s (possessive)

- –s (third singular person)

- –ed (past tense)

- –en (past participle)

- –ing (present participle)

- –er (comparative)

- –est (superlative)

Example :

Bag (root) – bag(s) = bags (steam)

Play (root) – play(er)(base)+(s) = players (steam)

- Base

Base I any unit to which affixes of any kind derivational/lexical affixes can be added. All roots are bases. Bases are called steams only in the context of inflectional morphology.

Example :

Like (root) + -dis = dislike(base)+ -ed (inflectional suffixes) = disliked( steam)

It means that stem ‘disliked’ come from base ‘dislike’

Affixes

Affixes is a morpheme (bound morpheme) which only occurs when attached to some other morphemes such as a root, steam or base. There are three kinds of affixes which are as follow :

- Prefix is an affix attached before a root, steam or base, like : re-,un-, -in, etc.

- Suffixe is an affix attached after a root, steam, base, like : -ly, -er, -ist, -s, -ing, and –ed.

- Infix ia an affix inserted into the root itself.

Example :

Write(root)+ (re-) = rewrite(base)+ (-ed) = rewrited (steam)

Posted in english | Leave a Comment

ROOTS, AFFIXES, STEMS AND BASES

ROOTS

A root is the irreducible core of a Word, with absolutely nothing else attached to it. It is the part that is always present, possibly with some modification, in the various manifestations of a lexeme. For example, walk is a root and it a appears in the set of word-forms that instantiate the lexeme WALK such as walk, walks, walking and walked.

The only situation where this is not true is when suppletion takes place. In that case, word-forms that represent the same morpheme do not share a common root morpheme. Thus, although both the word –forms good and better realise the lexeme GOOD, only good is phonetically similar to GOOD.

Many words contain a root standing on its own. Roots which are capable of standing independently are called free morphemes, for example:

Free morphemes

- Man book tea sweet cook

- Bet very aardvark pain walk

AFIXES

An affix is a morpheme which only occurs when attached to some other morpheme such as a root or stem or base. Obviously, by definition affixes are bound morphemes. No word may contain only an affix standing on its own, like *-s or * -al or even a number of affixes strung together like *-al-s.

There are three types of affixes. We will consider them in turn.

PREFIXES

A prefix is an affix attached before a root or stem or base like re-, un- and in-.

- Re-make un-kind in-decnt

- Re-read un-tidy in-accurate

SUFFIXES

A suffix is an affix attached after a root (or stem base) like –ly, -er, ist, -s, -ing and –ed.

- Kind-ly wait-er book-s walk-ed jump-ed

- Quick-ly play-er mat-s jump-ed

INFIXES

An infix is an affix inserted into the root itself. Infixes are very common in Semitic language like Arabic and Hebrew. But infixing is somewhere rare in English. Sloat and Taylor (1978) suggest that the only infix that occurs in English morphology is /-n-/ which is inserted before the last consonant of the root in a few words of Latin origin, on what appears to be an arbitrary basis.

This infix undergoes place of articulation assimilation. Thus, the root –cub- meaning “lie in, on or upon” occurs without [m] before the [b] in some words containing that root, e.g. incubate, incubus, concubine and succubus. But [m] is infixed before that same root in some other words like incumbent, succumb, and decumbent. This infix is a frozen historical relic from Latin.

In fact, infixation of sorts still happens in contemporary English. Example.

a. Kalamazu (places name) → Kalama-goddam-zoo

Instantiate (verb) → in-fuckin-stantiate

b. Kangaroo → kanga-bloody-roo

Impossible → in-fuckin-possible

Guarantee → guaran-friggin-tee

(Recall that the arrow → means “becomes” or is “re-written as”.)

As you can see, in present-day English infixation, not of an affix morpheme but of an entire word (which may have more than one morpheme, blood-y, fuck-ing) is actively used to form words. Curiously, this infixation is virtually restricted to inserting expletives into words in expressive language that one would probably not use in polite company.

ROOTS, STEMS AND BASES

The stem is that part of a word that is in existence before any inflectional affixes (those affixes whose presence is required by the syntax such as markers of singular and plural number in nouns, tense in verbs, etc.) have been added. Inflection is discussed in section. For the moment a few examples should suffice.

Cat -s

Worker -s

In the word-form cats, the plural inflectional suffix –s is attached to the simple stem cat, which is a bare root, the irreducible core of the word.

In workers the same inflectional -s suffix comes after a slightly more complex stem consisting of the root work plus the suffix -er which is used to the form nouns from verbs (with the meaning “someone who does the action designated by the verb (worker). Here work is the root, but worker is the stem to which -s is attached.

Finally a base is any unit whatsoever to which affixes of any kind can be added. The affixes attached to a base may be inflectional affixes selected for syntactic reasons or derivational affixes which alter the meaning or grammatical category of the base. An unadorned root like boy can be a base since it can have attached to it inflectional affixes like -s to form the plural boys or derivational affixes like -ish to turn the noun boy into the adjective boyish. In other words, all roots are bases. Bases are called stems only in the context of inflectional morphology.

STEM EXTENDERS

In the last chapter we saw that languages sometimes have word-building elements that are devoid of content. Such empty formatives are often referred to, somewhat inappropriately, as empty morphs.

In English empty formatives are interposed between the root, base or stem and an affix. For instance, while the irregular plural allomorph -en is attached directly to the stem ox to form ox-en, in the formation of chil-r-nen and breth-r-en it can only be added after the stem has been extended by attaching —r— to child— and breth-. Hence, the name stem extender for this type of formative.

The use of stem extenders may not be entirely arbitrary. There may be a good historical reason for the use of particular stem extenders before certain affixes. To some extent, current word-formation rules reflect the history of the language.

The history of stem extender -r- is instructive. A small number of nouns in Old English formed their plural by adding –er. The word “child” was cild in the singular and cilder in the plural (a form that has survived in some conservative North of England dialects, and is spelled childer). But later, -en was added as an additional plural ending. Eventually -er lost its value as a marker of plural and it simply became a stem extender:

Plural New Singular Plural

Cild “child” cild-er cilder cilder-en

This topic is very interesting but also very complicated and we consider the part of morphemes, suffixes and affixes is the most important morphology.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

MODERN LINGUISTICS

MORPHOLOGY

FRANCIS KATAMBA

EDITORS: PALGRAVE.

A. morpheme

The smallest meaningful unit in a language. A morpheme cannot be divided without altering or destroying its meaning. For example, the English word kind is a morpheme. If the d is removed, it changes to kin, which has a different meaning. Some words consist of one morpheme, e.g. kind, others of more than one. For example, the English word unkindness consists of three morphemes: the STEM1 kind, the negative prefix un-, and the noun-forming suffix -ness. Morphemes can have grammatical functions. For example, in English the –s in she talks is a grammatical morpheme which shows that the verb is the third-person singular present-tense form.

B. allomorph

any of the different forms of a MORPHEME. For example, in English the plural morpheme is often shown in writing by adding -s to the end of a word, e.g. cat /kæt/ – cats /kæts/. Sometimes this plural morpheme is pronounced /z/, e.g. dog /díg/ – dogs /dígz/, and sometimes it is pronounced /Iz/, e.g. class /klæs/ – classes /`klæsız/. /s/, /z/, and /Iz/ all have the same grammatical function in these examples, they all show plural; they are all allomorphs of the plural morpheme.

C. root

also base form

a MORPHEME which is the basic part of a word and which may, in many languages, occur on its own (e.g. English: man, hold, cold, rhythm). Roots may be joined to other roots (e.g. English: house _ hold → household) and/or take AFFIXes (e.g. manly, coldness) or COMBINING FORMs (e.g. biorhythm).

D. base form

another term for ROOT OR STEM1.

For example, the English word helpful has the base form help.

E. stem1

also base form

that part of a word to which an inflectional AFFIX is or can be added. For example, in English the inflectional affix -s can be added to the stem work to form the plural works in the works of Shakespeare. The stem of a word may be:

a. a simple stem consisting of only one morpheme (ROOT), e.g. work

b. a root plus a derivational affix, e.g. work _ -er _ worker

c. two or more roots, e.g. work _ shop _ workshop.

Thus we can have work _ -s _ works, (work _ -er) _ workers, or

(work _ shop) _ -s _ workshops.

F. Stem versus roots

STEM and ROOT are used to refer to the ‘base’ of a word. The part to which affixes attach. The distinction between them is based on the distinction between inflectional and derivational.

Consider a word like ‘kickers’, it contains two suffixes, one derivational (-er), the other inflectional (-s). strip both affixes off and you are left with kick, which we call a ROOT. Add back on the derivational suffix –er and you get kicker, we call the STEM.

More generally, a root is any single morpheme which is not an affix. Normally, you can find a root by removing all the affixes (both derivational and inflectional) from a word. The stem of a word, on other hand, is found by removing all the inflectional affixes, but leaving any derivational affixes in place.

A root is always a single morpheme. A stem on the other hand, may consists of more than one morpheme. Many stems, like cat consists of only a single root. The stem and the root are identical.

other stems consists of two or more roots, as in view-point. Neither view nor point is an affix and both are single morphemes. So they are both considered to be roots.

a stem containing more than one root is called a COMPOUND STEM or simply a COMPOUND; the process of forming such stems is called COMPOUNDING.

Compounding may, in some cases, involve derivational affixes too, as in rabble-rouser-r; this stem consists of two roots plus a derivational suffix.

and stem may contain more than one derivational affix, as in interlinearizer (a type of computer program that is used by linguists for inserting interlinear word-by-word or morpheme-by-morpheme glosses in a text)

thus, a stem consist of one or more roots, plus zero or more derivational affixes. A root, in contrast, is always a single morpheme.

All stems serve as the base to which inflectional affixes attach. So, for example, all the nouns mentioned above have plural forms.

a. cat-s

b. kicker-s

c. viewpoint-s

d. rabble-rouser-s

e. interlinearizer-s

virtually all roots are also stems and the simplest stems (those consisting of only one morpheme) are also roots.

In English grammar and morphology, a stem is the form of a word before any inflectional affixes are added. In English, most stems also qualify as words.

The term base is commonly used by linguists to refer to any stem (or root) to which an affix is attached.

Identifying a Stem

«A stem may consist of a single root, of two roots forming a compound stem, or of a root (or stem) and one or more derivational affixes forming a derived stem.»

(R. M. W. Dixon, The Languages of Australia. Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Combining Stems

«The three main morphological processes are compounding, affixation, and conversion. Compounding involves adding two stems together, as in the above window-sill — or blackbird, daydream, and so on. … For the most part, affixes attach to free stems, i.e., stems that can stand alone as a word. Examples are to be found, however, where an affix is added to a bound stem — compare perishable, where perish is free, with durable, where dur is bound, or unkind, where kind is free, with unbeknown, where beknown is bound.»

(Rodney D. Huddleston, English Grammar: An Outline. Cambridge University Press, 1988)

Stem Conversion

«Conversion is where a stem is derived without any change in form from one belonging to a different class. For example, the verb bottle (I must bottle some plums) is derived by conversion from the noun bottle, while the noun catch (That was a fine catch) is converted from the verb.»

(Rodney D. Huddleston, English Grammar: An Outline. Cambridge University Press, 1988)

The Difference Between a Base and a Stem

«Base is the core of a word, that part of the word which is essential for looking up its meaning in the dictionary; stem is either the base by itself or the base plus another morpheme to which other morphemes can be added. [For example,] vary is both a base and a stem; when an affix is attached the base/stem is called a stem only. Other affixes can now be attached.»

(Bernard O’Dwyer, Modern English Structures: Form, Function, and Position. Broadview, 2000)

The Difference Between a Root and a Stem

«The terms root and stem are sometimes used interchangeably. However, there is a subtle difference between them: a root is a morpheme that expresses the basic meaning of a word and cannot be further divided into smaller morphemes. Yet a root does not necessarily constitute a fully understandable word in and of itself. Another morpheme may be required. For example, the form struct in English is a root because it cannot be divided into smaller meaningful parts, yet neither can it be used in discourse without a prefix or a suffix being added to it (construct, structural, destruction, etc.) »

«A stem may consist of just a root. However, it may also be analyzed into a root plus derivational morphemes … Like a root, a stem may or may not be a fully understandable word. For example, in English, the forms reduce and deduce are stems because they act like any other regular verb—they can take the past-tense suffix. However, they are not roots, because they can be analyzed into two parts, -duce, plus a derivational prefix re- or de-.»

«So some roots are stems, and some stems are roots. ., but roots and stems are not the same thing. There are roots that are not stems (-duce), and there are stems that are not roots (reduce). In fact, this rather subtle distinction is not extremely important conceptually, and some theories do away with it entirely.»

(Thomas Payne, Exploring Language Structure: A Student’s Guide. Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Irregular Plurals

«Once there was a song about a purple-people-eater, but it would be ungrammatical to sing about a purple-babies-eater. Since the licit irregular plurals and the illicit regular plurals have similar meanings, it must be the grammar of irregularity that makes the difference.»

«The theory of word structure explains the effect easily. Irregular plurals, because they are quirky, have to be stored in the mental dictionary as roots or stems; they cannot be generated by a rule. Because of this storage, they can be fed into the compounding rule that joins an existing stem to another existing stem to yield a new stem. But regular plurals are not stems stored in the mental dictionary; they are complex words that are assembled on the fly by inflectional rules whenever they are needed. They are put together too late in the root-to-stem-to-word assembly process to be available to the compounding rule, whose inputs can only come out of the dictionary.»

(Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. William Morrow, 1994)