Poets have many tools that they can use to create their poems. The one you might be most familiar with is the effect of sound. When words are spoken aloud, they have lots of great sound qualities that poets can incorporate into their poems.

The most recognizable sound effect used in poems is rhyme. When two words rhyme, they have a similar ending sound. Words that end in the same letters, such as «take» and «make» rhyme, or words with different endings but the same sound rhyme, such as «cane» and «pain.» Poetry also makes use of near rhymes (or slant rhymes), which are words that almost rhyme, but not quite — such as «bear» and «far.»

Other sound effects make use of repeating letters or combinations of letters. Consonance is repeating the same consonants in words that are near each other. The statement «mummy’s mommy was no common dummy» is an example of consonance because the letter m is repeated. If the repeated letters appear only at the beginning of the words, this is known as alliteration. For example, «the big brown bear bit into a blueberry» is an example of alliteration because several words close together begin with the letter b.

If the letters or sounds that are repeated are vowels instead of consonants — as in «I might like to fight nine pirates at a time» — it is known as assonance. Assonance can be pretty subtle sometimes, and more difficult to identify than consonance or alliteration.

Sometimes a poet might want to make you imagine you’re hearing something. This is part of a concept called auditory imagery, or giving an impression of how something sounds. One common way to create auditory imagery is through the use of onomatopoeia. Think about words that describe a sound — words like buzz, clap or meow. When you say them aloud, they kind of sound like what they are describing. For example, the «zz» in the word buzz kind of sounds like the noise a bee makes.

There are many other types of sound effects that a poet can use, but these are just a few of the most common ones. Now that you understand how poets choose which words to use, let’s look at how poets put these words together by choosing to (or not to) follow a structure.

© 2023 Prezi Inc.

Terms & Privacy Policy

Today we are continuing our talk on prosody, or sound, in poetry. While many poems rhyme, they don’t all rhyme in the same way. Take the following excerpts of famous poems, for example. In all honesty, posting only the first verse of these poems isn’t fair, since often times the meter and form can only be seen when the poem is read in its entirety. But I simply want you to listen to how you read these poems and how they create rhythm in your head. See if you can figure out whether they have rising or falling rhythm, which we talked about last week.

Casey at the Bat by Ernest Lawrence Thayer

The Outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day:

The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play.

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A sickly silence fell upon the patrons of the game.

The Highwayman by Alfred Noyes

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees.

The moon was a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas.

The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor,

And the highwayman came riding—

Riding—riding—

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.

The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Mary’s Lamb

Mary had a little lamb,

Its fleece was white as snow,

And every where that Mary went

The lamb was sure to go;

He followed her to school one day—

That was against the rule,

It made the children laugh and play,

To see a lamb at school.

Alliteration

Alliteration is the repetition of the same consonant sounds within close proximity. This usually happens in consecutive words that are in the same line. In The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe, the author uses alliteration in pairs of words. See if you can find the word pairs in each line below.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping.

In Lord Byron’s poem, She Walks in Beauty, he uses alliteration twice in the second line.

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

In Birches by Robert Frost, the “b” sound is repeated. Doing so brings emphasis to those words and the poem’s theme.

When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.

But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay.

Tongue twisters can take alliteration to the extreme.

Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. A peck of pickled peppers Peter Piper picked. If Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers, how many pickled peppers did Peter Piper pick?

Assonance

Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds in a line. This also happens with words in close proximity to one another. Take the lyrics from the song “The Rain in Spain” from the musical My Fair Lady, for example. “The rain in Spain stays mainly on the plain.” The repetition of the long “a” sound is assonance. And in the final stanza of Annabel Lee, Edgar Allan Poe uses the repetition of the long “i” sound.

And so all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride”

Consonance

Consonance is the repetition of the same consonant sounds. Like assonance, the repetition should be close enough for the ear to make the connection. Listen for the repeated “L” sound in this line from Mary Oliver’s Wild Geese.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.

Here is a great example of consonance (and alliteration) from V for Vendetta by Alan Moore.

“However, this valorous visitation of a bygone vexation stands vivified and has vowed to vanquish these venal and virulent vermin vanguarding vice and vouchsafing the violently vicious and voracious violation of volition!”

Rhyme

Rhyming is another way to choose words in order to repeat certain sounds. There are two types of rhyming. Exact rhyme repeats the exact combination of vowel and consonant sound. Words like “bad, sad, glad, and mad” are exact rhymes because the “a” and the following “d” are identical in each word. Near rhymes (also called slant rhymes) have a repeated sound that is not exactly the same. Words like “back, sick, deck, and speak” are near rhymes because they all end in a K sound. Words like blame and foam are also near rhymes because they have the same “m” sound, even though the vowel sounds are different.

Rhyme Schemes

Rhyme schemes are used to create patterns of sounds through repetition. There are a wide variety of rhyme schemes that can be used. Most often, the last word in a line is meant to rhyme with the last word in another line. Sometimes the last word of every line has the same rhyme sound. Sometimes it’s the first and third lines that rhyme. Sometimes the second and fourth. It’s really up to you. In the poem below by Robert Frost, I used capital letters at the end of each line to match rhymes and identify the pattern used. Lines marked with (A) all rhyme. Lines marked with (B) rhyme. And so on.

Neither Out Far Nor In Deep by Robert Frost

The people along the sand (A)

All turn and look one way. (B)

They turn their back on the land. (A)

They look at the sea all day. (B)

As long as it takes to pass (C)

A ship keeps raising its hull; (D)

The wetter ground like glass (C)

Reflects a standing gull. (D)

The land may vary more; (E)

But wherever the truth may be— (F)

The water comes ashore, (E)

And the people look at the sea. (F)

They cannot look out far. (G)

They cannot look in deep. (H)

But when was that ever a bar (G)

To any watch they keep? (H)

Then consider the rhyme scheme of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star by Donald Barthelme

Twinkle, twinkle, little star, (A)

How I wonder what you are. (A)

Up above the world so high, (B)

Like a diamond in the sky. (B)

Twinkle, twinkle little star (A)

How I wonder what you are (A)

Little Jack Horner by Mother Goose

Little Jack Horner (A)

Sat in the corner, (A)

Eating a Christmas pie; (B)

He put in his thumb, (C)

And pulled out a plum, (C)

And said, “What a good boy am I!” (B)

Limericks are poems of five lines that are usually humorous. They have an AABBA rhyme scheme. Also, the first, second, and fifth line have the same meter, while the third and fourth lines have a shorter, identical meter.

There Once Was a Man From Nantucket by Dayton Voorhees

There once was a man from Nantucket (A)

Who kept all his cash in a bucket. (A)

But his daughter, named Nan, (B)

Ran away with a man (B)

And as for the bucket, Nantucket. (A)

There are many different types of rhyme schemes. You can find a long list of them in this Wikipedia article.

Poetry Challenge

Today’s poetry challenge is to write a new stanza of four lines. This could be a new poem or you could add a second stanza to your poem from last week. This time, however, you must first use one of: alliteration, assonance, or consonance. Then second, you must create a rhyme scheme. Post your poem in the comments, but don’t say what acoustics or rhyme scheme you used. Let your fellow poets see if they can figure it out. Have fun!

Sound devices are sometimes referred to as musical devices and are concerned with examples of euphony, cacophony, dissonance, and assonance. When a writer wants to create sound in a piece of writing, they use a wide variety of techniques. Repetition is one of the most important. They can repeat syllables, words, individual letter sounds, and more. Sound is one type of imagery in poetry. It appeals to the reader’s sense of hearing and should help the piece of writing feel more real and more interesting.

Definition of Sound Devices

Sound devices are techniques writers use to make them sound more prominent in a piece of wiring. It’s these devices that make poetic writing sound different than prose writing. Through examples of anaphora, alliteration, assonance, consonance, and more, writers make the sound of a piece of writing more important. Sound devices can create a feeling of unity between lines or even create a specific atmosphere (which may be light-hearted, gloomy, etc.).

Examples of Sound Devices in Poetry

Sonnet 130 by William Shakespeare

Rhyme is one of the most important ways that writers emphasize sound in poetry. It’s perhaps the best way to do so. There are numerous types of rhyme in poetry, but perfect end-rhymes are the easiest to recognize. In this Shakespearean sonnet, the poet makes use of a regular rhyme scheme that is used throughout his 154 sonnets. Consider these lines:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

In the first four lines of ‘Sonnet 130,’ the poet uses the end rhymes “sun” and “dun” and “red” and “head.” These are perfect end rhymes that set up the rest of the pattern. The entire poem rhymes ABABCDCDEFEFGG. This is an alternate rhyme scheme that ends with a couplet. Often, the couplet summarizes the poem or presents the reader with an alternative point of view. This is known as the turn. The rhyme in this poem is most effective when read out loud. It evokes a musical feeling that is traditionally associated with poetic writing.

The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe

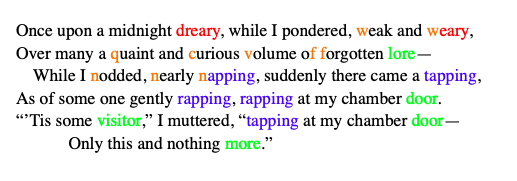

When considering sound devices, euphony is crucial for understanding how writers create specific feelings. It is a literary device that refers to the musical, or pleasing, qualities of words. In ‘The Raven,’ readers can find a few good examples of euphony. It’s created through the use of repetition, rhyme, meter, and more. The poem’s subject matter is dark, mysterious, and disturbing. But, Poe’s skilled use of euphony makes the poem a pleasure to read. Consider these lines:

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.

While end rhymes can be effective, internal rhymes are also quite important when creating rhyme and euphony. For example, “dreary” and “weary” in the first line. Alliteration is also present as an important sound device in this poem. For instance, “nearly napping” and “nodding” in the third line and “weak and weary” in line one.

Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll

In this famed Lewis Carroll poem, the poet uses several good examples of cacophony, one of the most important sound devices. It is his best-known poem and is often cited as the best example of nonsense language in contemporary verse. Consider these lines and how sound is used:

Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!

His use of loud and harsh-sounding words in this passage creates a jarring noise and conveys the danger that the Jabberwock poses. In many cases, the use of consonant sounds like “k” and “ch” make up examples of cacophony.

Cacophony and Euphony

These two literary terms are connected to one another, but readers should be aware of how different they are from one another. Euphony refers to the quality of sound in a piece of writing. It, along with cacophony, are ways of describing what the sound in a piece feels like. A cacophonous piece of writing lacks melody or harmony. It’s often unpleasant to hear/read. A euphonious piece of writing is the opposite. It is pleasing to the ear and uses unified-feeling vowel sounds, repetition, and perfect rhymes.

Why Do Writers Use Sound Devices?

Writers use sound devices when they want to give their poetry a specific feeling, make it sound more musical, and unite elements. They are used most commonly in poetry but can also be found in prose. Usually, it is sound devices and the use of syntax that set verse apart from prose. When used well, sound devices can make writing a pleasure to read. They create emotion through the use of rhyme, rhythm, alliteration, meter, and more. Sound devices are also an important part of a writer’s ability to create imagery.

FAQs

What are sound devices?

Sound devices are techniques poets use to make their work sound more pleasing or displeasing to the ear. It can create a sense of unity and make a poem, or even a piece of prose, feel more musical.

How are sound devices used?

Sound devices are used when the writer wants to make their work sound more musical. They are most common in poetry but can also be found in prose. Sound devices are generally what set poetry apart from prose.

Why is sound important in poetry?

Sound is important because it allows readers to better envision scenes and feel moods the writer was interested in. It can create an interesting atmosphere and make a poem more engaging.

How to identify sound devices?

Look for examples of repetition, count syllables, and read the text out loud.

- Internal rhyme: occurs in the middle of lines of poetry. It refers to words that rhyme in the middle of the same line or across multiple lines.

- Assonance: occurs when two or more words that are close to one another use the same vowel sound.

- Consonance: the repetition of a consonant sound in words, phrases, sentences, or passages in prose and verse writing.

- Eye Rhyme: a literary device used in poetry. It occurs when two words are spelled the same or similar but are pronounced differently.

- Exact Rhyme: a literary device that’s used in poetry. It occurs when the writer uses the same stressed vowel or consonant sounds.

- Repetition: an important literary technique that sees a writer reuse words or phrases multiple times.

Other Resources

- Listen: Rhyme and Rhyme Scheme in Poetry

- Watch: Internal Rhyme in Rap

- Watch: Why we love repetition in music

What do the words “anaphora,” “enjambment,” “consonance,” and “euphony” have in common? They are all literary devices in poetry—and important poetic devices, at that. Your poetry will be greatly enriched by mastery over the items in this poetic devices list, including mastery over the sound devices in poetry.

This article is specific to the literary devices in poetry. Before you read this article, make sure you also read our list of common literary devices across both poetry and prose, which discusses metaphor, juxtaposition, and other essential figures of speech.

We will be analyzing and identifying poetic devices in this article, using the poetry of Margaret Atwood, Louise Glück, Shakespeare, and others. We also examine sound devices in poetry as distinct yet essential components of the craft.

Check Out Our Poetry Writing Courses!

(Live Workshop) Poetry as Sacred Attention

with Nadia Colburn

June 6th, 2023

Poetry asks us to slow down, listen, and pay attention. In this meditative workshop, we’ll open ourselves to the beauty and mystery of poetry.

Literary Devices in Poetry: Poetic Devices List

Let’s examine the essential literary devices in poetry, with examples. Try to include these poetic devices in your next finished poems!

1. Anaphora

Anaphora describes a poem that repeats the same phrase at the beginning of each line. Sometimes the anaphora is a central element of the poem’s construction; other times, poets only use anaphora in one or two stanzas, not the whole piece.

Consider “The Delight Song of Tsoai-talee” by N. Scott Momaday.

I am a feather on the bright sky

I am the blue horse that runs in the plain

I am the fish that rolls, shining, in the water

I am the shadow that follows a child

I am the evening light, the lustre of meadows

I am an eagle playing with the wind

I am a cluster of bright beads

I am the farthest star

I am the cold of dawn

I am the roaring of the rain

I am the glitter on the crust of the snow

I am the long track of the moon in a lake

I am a flame of four colors

I am a deer standing away in the dusk

I am a field of sumac and the pomme blanche

I am an angle of geese in the winter sky

I am the hunger of a young wolf

I am the whole dream of these things

You see, I am alive, I am alive

I stand in good relation to the earth

I stand in good relation to the gods

I stand in good relation to all that is beautiful

I stand in good relation to the daughter of Tsen-tainte

You see, I am alive, I am alive

This poem is an experiment in metaphor: how many ways can the self be reproduced after “I am”? The simple “I am” anaphora draws attention towards the poet’s increasing need to define himself, while also setting the poet up for a series of well-crafted poetic devices.

Anaphora describes a poem that repeats the same phrase at the beginning of each line.

The self shapes the core of Momaday’s poem, as emphasized by the anaphora. Still, our eye isn’t drawn to the column of I am’s, but rather to Momaday’s stunning metaphors for selfhood.

2. Conceit

A conceit is, essentially, an extended metaphor. Which, when you think about it, it’s kind of stuck-up to have a fancy word for an extended metaphor, so a conceit is pretty conceited, don’t you think?

In order for a metaphor to be a conceit, it must run through the entire poem and be the poem’s central device. Consider the poem “The Flea” by John Donne. The speaker uses the flea as a conceit for physical relations, arguing that two bodies have already intermingled if they’ve shared the odious bed bug. With the flea as a conceit for intimacy, Donne presents a poem both humorous and strangely erotic.

A conceit must run through the entire poem as the poem’s central device.

The conceit ranks among the most powerful literary devices in poetry.In your own poetry, you can employ a conceit by exploring one metaphor in depth. For example, if you were to use matchsticks as a metaphor for love, you could explore love in all its intensity: love as a stroke of luck against a matchbox strip, love as wildfire, love as different matchbox designs, love as phillumeny, etc.

3. Apostrophe

Don’t confuse this with the punctuation mark for possessive nouns—the literary device apostrophe is different. Apostrophe describes any instance when the speaker talks to a person or object that is absent from the poem. Poets employ apostrophe when they speak to the dead or to a long lost lover, but they also use apostrophe when writing an Ode to a Grecian Urn or an Ode to the Women in Long Island.

Apostrophe is often employed in admiration or longing, as we often talk about things far away in wistfulness or praise. Still, try using apostrophe to express other emotions: express joy, grief, fear, anger, despair, jealousy, or ecstasy, as this poetic device can prove very powerful for poetry writers.

4. Metonymy & Synecdoche

Metonymy and synecdoche are very similar poetic devices, so we’ll include them as one item. A metonymy is when the writer replaces “a part for a part,” choosing one noun to describe a different noun. For example, in the phrase “the pen is mightier than the sword,” the pen is a metonymy for writing and the sword is a metonymy for fighting.

Metonymy: a part for a part.

In this sense, metonymy is very similar to symbolism, because the pen represents the idea of writing. The difference is, a pen is directly related to writing, whereas symbols are not always related to the concepts they represent. A dove might symbolize peace, but doves, in reality, have very little to do with peace.

Synecdoche is a form of metonymy, but instead of “a part for a part,” the writer substitutes “a part for a whole.” In other words, they represent an object with only a distinct part of the object. If I described your car as “a nice set of wheels,” then I’m using synecdoche to refer to your car. I’m also using synecdoche if I call your laptop an “overpriced sound system.”

Synecdoche: a part for a whole.

Since metonymy and synecdoche are forms of symbolism, they appear regularly in poetry both contemporary and classic. Take, for example, this passage from Shakespeare’s A Midsommar Night’s Dream:

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Shakespeare makes it seem like the poet’s pen gives shape to airy wonderings, when in fact it’s the poet’s imagination. Thus, the pen becomes metonymous for the magic of poetry—quite a lofty comparison which only a bard like Shakespeare could say.

5. Enjambment & End-Stopped Lines

Poets have something at their disposal which prose writers don’t: the mighty line break. Line breaks and stanza breaks help guide the reader through the poem, and while these might not be hardline “literary devices in poetry,” they’re important to understanding the strategies of poetry writing.

Line breaks can be one of two things: enjambed or end-stopped. End-stopped lines are lines which end on a period or on a natural break in the sentence. Enjambment, by contrast, refers to a line break that interrupts the flow of a sentence: either the line usually doesn’t end with punctuation, and the thought continues on the next line.

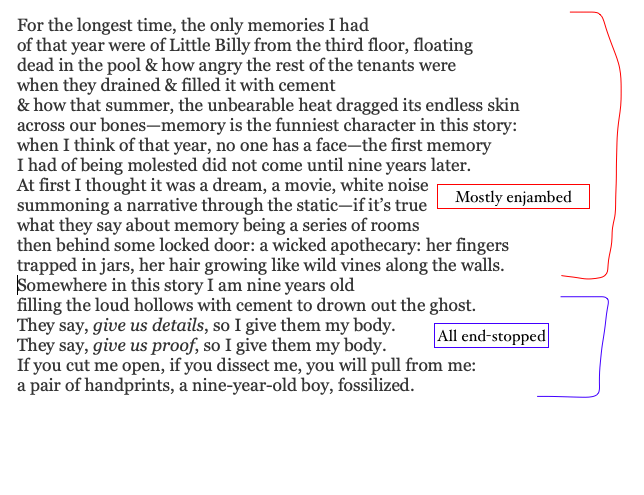

Let’s see enjambed and end-stopped lines in action, using “The Study” by Hieu Minh Nguyen.

Most of the poem’s lines are enjambed, using very few end-stops, perhaps to mirror the endless weight of midsummer. Suddenly, the poem shifts to end-stops at the end, and the mood of the poem transitions: suddenly the poem is final, concrete in its horror, horrifying perhaps for its sincerity and surprising shift in tone.

Line breaks and stanza breaks help guide the reader through the poem.

Enjambment and end-stopping are ways of reflecting and refracting the poem’s mood. Spend time in your own poetry determining how the mood of your poems shift and transform, and consider using this poetry writing strategy to reflect that.

6. Zeugma

Zeugma (pronounced: zoyg-muh) is a fun little device you don’t see often in contemporary poetry—it was much more common in ancient Greek and Latin poetry, such as the poetry of Ovid. This might not be an “essential” device, but if you use it on your own poetry, you’ll stand out for your mastery of language and unique stylistic choices.

A zeugma occurs when one verb is used to mean two different things for two different objects. For example, I might say “He ate some pasta, and my heart out.” To eat pasta and eat someone’s heart out are two very different definitions for ate: one consumption is physical, the other is conceptual. The key here is to only use “ate” once in the sentence, as a zeugma should surprise the reader.

Now, take this excerpt from Ovid’s Heroides 7:

You are then resolved to depart, and abandon unhappy Dido;

the same winds will bear away your promises and sails.

You are resolved, Aeneas, to weigh your anchor and your vows,

and go in quest of Italy, a land to which you are wholly a stranger.

Can you identify the zeugmas? “Bear” and “weigh” are both used literally and figuratively, bearing weight to the speaker’s laments.

Zeugmas are a largely classical device, because the constraints of ancient poetic meter were quite strict, and the economic nature of Latin encouraged the use of zeugma. Nonetheless, try using it in your own poetry—you might surprise yourself!

7. Repetition

Strategic repetition of certain phrases can reinforce the core of your poem.

Last but not least among the topliterary devices in poetry, repetition is key. We’ve already seen repetition in some of the aforementioned poetic devices, like anaphora and conceit. Still, repetition deserves its own special mention.

Strategic repetition of certain phrases can reinforce the core of your poem. In fact, some poetry forms require repetition, such as the villanelle. In a villanelle, the first line must be repeated in lines 6, 12, and 18; the third line must be repeated in lines 9, 15, and 19.

See this repetition in action in Sylvia Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song.” Notice how the two repeated lines reinforce the subjects of both love and madness—perhaps finding them indistinguishable? Take note of this masterful repetition, and see where you can strategically repeat lines in your own poetry, too.

Sound Devices in Poetry

The other half of this article analyzes the different sound devices in poetry. These poetic sound devices are primarily concerned with the musicality of language, and they are powerful poetic devices for altering the poem’s mood and emotion—often in subtle, surprising ways.

What are sound devices in poetry, and how do you use them? Let’s explore these other literary devices in poetry, with examples.

8. Internal & End Rhyme

When you think about poetry, the first thing you probably think of is “rhyme.” Yes, many poems rhyme, especially poetry in antiquity. However, contemporary poetry largely looks down upon poetry with strict rhyme schemes, and you’re far more likely to see internal rhyming than end rhyming.

Internal rhyme is just what it sounds like: two rhyming words juxtaposed inside of the line, rather than at the end of the line. See internal rhyme in action Edgar Allan Poe’s famous “The Raven”:

Each of the rhymes have been assigned their own highlighted color. I’ve also highlighted examples of alliteration, which this article covers next.

Despite “The Raven’s” macabre, dreary undertones, the play with language in this poem is entertaining and, quite simply, fun. Not only does it draw readers into the poem, it makes the poem memorable—after all, poetry used to rhyme because rhyme schemes helped people remember the poetry, long before people had access to pen and paper.

Why does contemporary poetry frown at rhyme schemes? It’s not the rhyming itself that’s odious; rather, contemporary poetry is concerned with fresh, unique word choice, and rhyme schemes often limit the poet’s language, forcing them to use words which don’t quite fit.

contemporary poetry is concerned with fresh, unique word choice, and rhyme schemes often limit the poet’s language

If you can write a rhyming poem with precise, intelligent word choice, you’re an exception to the rule—and far more skilled at poetry than most. Perhaps you should have been born a bard in the 16th century, blessed with the king’s highest graces, splayed dramatically on a decadent chaise longue with maroon upholstery, dining on grapes and cheese.

9. Alliteration

Alliteration is a powerful, albeit subtle, means of controlling the poem’s mood.

One of the more defining sound devices in poetry, alliteration refers to the succession of words with similar sounds. For example: this sentence, so assiduously steeped in “s” sounds, was sculpted alliteratively.

Alliteration is a powerful, albeit subtle, means of controlling the poem’s mood. A series of s’es might make the poem sound sinister, sneaky, or sharp; by contrast, a series of b’s, d’s, and p’s will give the poem a heavy, percussive sound, like sticks against a drum.

Emily Dickenson puts alliteration to play in her brief poem “Much Madness.” The poem is a cacophonous mix of s, m, and a sounds, and in this cacophony, the reader gets a glimpse into the mad array of the poet’s brain.

Alliteration can be further dissected; in fact, we could spend this entire article talking about alliteration if we wanted to. What’s most important is this: playing with alliterative sounds is a crucial aspect of poetry writing, helping readers experience the mood of your poetry.

10. Consonance & Assonance

Along with alliteration, consonance and assonance share the title for most important sound devices in poetry. Alliteration refers specifically to the sounds at the beginning: consonance and assonance refer to the sounds within words. Technically, alliteration is a form of consonance or assonance, and both can coexist powerfully on the same line.

Consonance refers to consonant sounds, whereas assonance refers to vowel sounds. You are much more likely to read examples of consonance, as there are many more consonants in the English alphabet, and these consonants are more highly defined than vowel sounds. Though assonance is a tougher poetic sound device, it still shows up routinely in contemporary poetry.

In fact, we’ve already seen examples of assonance in our section on internal rhyme! Internal rhymes often require assonance for the words to sound similar. To refer back to “The Raven,” the first line has assonance with the words “dreary,” “weak,” and “weary.” Additionally, the third line has consonance with “nodded, nearly napping.”

These poetic sound devices point towards one of two sounds: euphony or cacophony.

11. Euphony & Cacophony

Poems that master musicality will sound either euphonious or cacophonous. Euphony, from the Greek for “pleasant sounding,” refers to words or sentences which flow pleasantly and sound sweetly. Look towards any of the poems we’ve mentioned or the examples we’ve given, and euphony sings to you like the muses.

Cacophony is a bit harder to find in literature, though certainly not impossible. Cacophony is euphony’s antonym, “unpleasant sounding,” though the effect doesn’t have to be unpleasant to the reader. Usually, cacophony occurs when the poet uses harsh, staccato sounds repeatedly. Ks, Qus, Ls, and hard Gs can all generate cacophony, like they do in this line from “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” from Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

agape they heard me call.

Reading this line might not be “pleasant” in the conventional sense, but it does prime the reader to hear the speaker’s cacophonous call. Who else might sing in cacophony than the emotive, sea-worn sailor?

12. Meter

What’s something you still remember from high school English? Personally, I’ll always remember that Shakespeare wrote in iambic pentameter. I’ll also remember that iambic pentameter resembles a heartbeat: “love is a smoke made with the fumes of sighs.” ba-dum, ba-dum, ba-dum.

Metrical considerations are often reserved for classic poetry. When you hear someone talking about a poem using anapestic hexameter or trochaic tetrameter, they’re probably talking about Ovid and Petrarch, not Atwood and Gluck.

Still, meter can affect how the reader moves and feels your poem, and some contemporary poets write in meter.

Before I offer any examples, let’s define meter. All syllables in the English language are either stressed or unstressed. We naturally emphasize certain syllables in English based on standards of pronunciation, so while we let words like “love,” “made,” and “the” dangle, we emphasize “smoke,” “fumes,” and “sighs.”

Depending on the context, some words can be stressed or unstressed, like “is.” Assembling words into metrical order can be tricky, but if the words flow without hesitation, you’ve conquered one of the trickiest sound devices in poetry.

Common metrical types include:

- Iamb: repetitions of unstressed-stressed syllables

- Anapest: repetitions of unstressed-unstressed-stressed syllables

- Trochee: repetitions of stressed-unstressed syllables

- Dactyl: repetitions of stressed-unstressed-unstressed syllables

Finding these prosodic considerations in contemporary poetry is challenging, but not impossible. Many poets in the earliest 20th century used meter, such as Edna St. Vincent Millay. Her poem, “Renascence,” built upon iambic tetrameter. Still, the contemporary landscape of poetry doesn’t have many poets using meter. Perhaps the next important metrical poet is you?

Mastering the Literary Devices in Poetry

Every element of this poetic devices list could take months to master, and each of the sound devices in poetry requires its own special class. Luckily, the instructors at Writers.com know just how to sculpt poetry from language, and they’re ready to teach you, too. Take a look at our upcoming poetry courses, and take the next step in mastering the literary devices in poetry.

Poetry is a special form of writing that allows a student to express ideas, emotions, or experiences directly through words in verse. It is probably the most artistic of all genres of writing because of the delicate juggling act of (a) rhythms, (b) sound devices, and (c) subject matter.

The sounds of the words in a line of poetry make a rhythm that is similar to the rhythm in music. This rhythm is established by stressed and unstressed syllables. The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a poem is called its meter. It’s important to pay attention to rhythm because it’s key to understanding the full effect of a poem.

Some poets use sound devices as a strategy to create an emotional response by the listener. Sound devices are special tools the poet can use to create certain effects in the poem to convey and reinforce meaning through sound. The four most common sound devices are repetition, rhyme, alliteration, and assonance.

Subject matter for any form of poetry writing is limitless. Subject matter is the topic that is being written about and serves as the foundation for the text.

Are you aware that incorporating poetry lessons throughout the school year can actually improve your students’ writing in other genres? Poetry writing helps students develop language, vocabulary, and word choice skills. Each word in a poem is packed with meaning to show instead of tell, so good poets carefully choose each word for the effect its meaning and sound will have on the listener. They choose words that will bring about sensory images in the imagination and emotional responses in the heart.

Personally, I think couplets are a fun way to begin teaching students about the basics of rhythm and rhyme, using any subject matter of interest. A couplet refers to two successive lines of poetry that rhyme and have the same meter. A couplet can consist of only two lines, or it can have multiple rhyming stanzas, consisting of two lines each.

Take a look at these examples:

I do not like green eggs and ham

I do not like them Sam I am.

— Green Eggs and Ham, Dr. Seuss

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again!

— Nursery Rhyme

Here’s some more information you need to understand about couplets: Couplets may be formal or run-on. A formal (or closed) couplet has a grammatical pause at the end of each line or verse. On the other hand, a run-on (or open) couplet allows the meaning of the first line to continue to the second line. This is also called enjambment.

Couplet Writing Activity:

Divide into small groups. Each group selects a subject based on the current season. (For example, if the season is fall, a group could select Halloween, football, falling leaves, etc.) Each member of the group writes a couplet with multiple rhyming stanzas, consisting of two lines each to declare the chosen subject matter.

Then, each group creates a mural or collage to celebrate the chosen subject matter. Each group tells about its subject in both the poem and artwork. Discuss the artwork and couplets and how they made you feel about the selected subject matter. Be sure to follow the Rules for Discussion and the Guidelines for an Oral Presentation:

Of all the areas in literary analysis, writing about sound is probably one of the most challenging.

Why is it so difficult?

For starters, it’s hard work.

First, you need to read the poem aloud (something not everyone is willing to do). Then, you have to discern the ‘sounds’ in the poem, identify the ‘type(s)’ of sound and the corresponding terms for them, and finally, write the actual analysis in which you consider how the sound conveys a message or serves the purpose of a text.

As you can tell, this process is not for the faint-hearted, or the ‘can’t-be-ars-ed’.

But precisely because most people won’t want to put in the hard work required for sound analysis (in this respect, it’s similar to rhythm analysis, which I break down for you here), engaging with sound devices is a fantastic way to give yourself an edge when it comes to writing English literature essays and commentaries.

A quick note on ‘easy sound’ in poetry

When you first started learning poetry, you probably came across the complicatedly spelt but easily graspable term of “onomatopoeia”, which basically just means –

The sound of the thing being described

So ‘moo’ would be an example of onomatopoeia for cows, whereas ‘achoo’ mimics the sound of people sneezing.

Among all the sound devices, onomatopoeia is arguably the easiest – because it’s the most obvious.

The others ones, which we’ll look at in this post, are alliteration, assonance and consonance. Like paradox and oxymoron (which you can learn all about here), these sound devices are related, but different – and sometimes, confusingly so.

But unlike paradox and oxymoron, which are semantic devices (i.e. related to the meaning of words), alliteration and assonance are sonic devices, and this makes it considerably harder to analyse in terms of their contribution to the themes and meaning of a given text.

Hopefully, this post will make it easier for you!

Alliteration, assonance and consonance explained

First, let’s get the basics out of the way –

-

- Alliteration:

The repetition of a) consonant sounds (anything that isn’t ‘aeiou’), b) emitted from the first letter / stressed syllable, and c) placed in close proximity with one another

-

- Assonance:

The repetition of a) vowel sounds (‘aeiou’), b) placed in close proximity with one another. First letter / stressed syllable placement is NOT necessary.

-

- Consonance:

The repetition of a) consonant sounds b) placed in close proximity with one another. First letter / stressed syllable placement is NOT necessary.

Here’s a diagram to help visualise:

To illustrate with examples –

-

- Alliteration:

Sally said she would make Sam a salami sandwich on Sunday.

-

- Assonance:

Sally said she was mad that Sam got canned tuna from the groceryman again.

-

- Consonance:

Sally was dissatisfied with the unreasonable requests she kept receiving from Sam, especially the one for minced sardine sandwiches, which she thought to be an exceptional waste of time.

Silly as these sentences may sound (see what I did there), I hope they clarify for you the relationship between these important devices.

Notice, by the way, that alliteration, assonance and consonance all fall under the broad umbrella of repetition (which I write about at length here).

What are the different types of alliteration?

Now that we’ve got the macro distinctions out of the way, it’s time to dive into the specifics and look at the different types of alliteration.

As mentioned, alliteration refers to the repetition of consonant sounds (which is not necessarily a repetition of the same letter, e.g. the ‘c’ in ‘centre’ would alliterate with the ‘s’ in ‘silly’, not ‘c’ in ‘crazy’).

Minus the 5 vowels ‘a, e, i, o, u’, that means there are 21 consonant sounds that can be alliterated.

But instead of saying “the alliteration of the ‘b’ sound” or the “alliteration of the ‘f’ sound”, we can be a bit more technical by using the terms below:

In general, short, abrupt sounds tend to be harsher on the ear, and the longer, smoother ones less so.

If you try pronouncing a consonant letter and it follows with a natural stop (e.g. you can’t extend a ‘b’ sound – the lips smack, the sound comes out, and boom, that’s it), then you’re looking at any one of the four types on the left column.

On the other hand, if you pronounce a consonant and it allows you to drag on audibly, then it most likely belongs to a type listed in the right column.

We need to know how to describe these sounds, too. Below is a selection of words for the two broad alliterative groups, depending on the context in and frequency with which they are repeated:

Given the similar nature of consonance and alliteration, then, these alliterative types and descriptive words would also apply to any analysis on the use of consonance.

Is assonance basically just another kind of rhyme?

Kind of. Yes.

In fact, we can think of assonance as a sort of ‘scattered’ rhyme – a combination of slant rhyme and half rhyme.

On the contrary, regular rhyme usually follows a set pattern, such as

- End rhyme: the last words in each line sound similar to each other),

- Alternate rhyme: the last words in every other line sound similar to each other

- Chain rhyme: the last word in one stanza sounds similar to the last words in the next stanza

- Rhyming couplet: the last word in successive lines sound similar to each other)

etc.

Assonance, then, is structurally freer, and so the impression is one of holistic, rather than regular, sonic harmony. It’s more organic, in a sense.

It’s very important to remember, however, that simply being able to trot out the terms and identify types won’t’ suffice to make for great analysis.

This is why the following section is muy importante, so read on.

How to write a killer analysis on alliteration – reading ‘Pied Beauty’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Statistically, I’ve come to realise that it’s actually quite hard not to find alliteration in most poems, so what makes this literary device worth analysing usually rests on how much alliteration there is in a given poem.

First, before we even get into the technical specifics, it’s important that we gain an overall sense of what a poem sounds like.

On a most basic level, does it sound pleasant or noisy?

When you read it aloud, do you feel like the words are short and abrupt, or do the syllables seem to drag out without much friction on the tongue?

Then, refer to the table on the ‘two main sound camps’ I’ve outlined above. Most likely, if a poem sounds ‘noisy’ (not necessarily in a ‘harsh’ sense, but loud), then there would be more plosives, fricatives, affricates and nasals; if a poem sounds mellifluous, then you’d probably find more sibilants, semivowels, laterals and rhotics.

As a caveat, this is not a hard and fast rule, just a general guide to get you started on thinking about poetic sounds in a more schematic way.

One of the most well-known alliterative poems (which is different from the Medieval alliterative verse) is Gerard Manley Hopkins’ ‘Pied Beauty’, which was written in 1877 but published posthumously in 1918.

‘Pied Beauty’s’ message is rather straightforward: we should celebrate God for having created “all things” on Earth, regardless of whether these things are ordinary, beautiful, weird, or imperfect. What makes this poem such a work of wonder, though, is in Hopkins’ skilful use of alliteration.

Hopkins’ ‘Pied Beauty’ is overwhelmingly ‘noisy’, to say the least. If you don’t read this poem aloud, then I’d argue that you’ve not read this poem at all. The way it sounds is arguably just as important as what it says:

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

In the first sestet, plosive words dominate, followed by fricatives. Even in the three sibilants that we can find (“skies”, “stipple”, “swim”), two of them are conjugated with plosive sounds (“sk-“ and “st-“).

There’s a wide variety in the range of plosive consonants featured, such as ‘b’ (“brinded”), ‘c’ (“couple-colour”), ‘d’ (“dappled”), ‘g’ (“Glory be to God”), ‘p’ (“plotted and pieced”, “plough”) and ‘t’ (“tackle”), while the use of fricatives are mostly focused on the ‘f’ sound (“fresh-firecoal”, “chestnut-falls”, “finches”, “fold”, fallow”) and ‘th’ sound (“things”, “that”, “their”). There’s also consonance weaved in, specifically in “upon” and “firecoal”.

You can see, then, that this isn’t so much a stanza as it is a symphony composed in words; it is less poetry than music.

The bigger point is that beauty lies not just in what’s pleasing to the ear and the eye, but paradoxically, also in what’s jarring, odd, discordant and unconventional. The mixture of sounds may seem “counter” to what we’re normally used to, but it is “original”, and for that, it is to be celebrated.

In the forceful push of the tongue when we read “Glory be to God”, the happy jig of the rhythm in “couple-colour as a brinded cow”, and the freeing flit of the lips from reading “fresh-firecoal” and “finches wings”, we are encouraged to experience these moments of vitality, which are vicariously delivered through a vibrant string of alliterative combinations.

As we move into the cinquain (i.e. a five-line stanza), however, Hopkins tones down on the plosives and features more sibilants. And yet, the poem’s not much quieter for that:

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

“Swift, slow; sweet, sour”: sonically, these are similar sounds; but semantically, they are opposite concepts. Is the idea that even with all the stark differences around us, harmony can still exist at large? That God’s all-encompassing hand of creation is a generous one, one that accepts deviations – “whatever is fickle, freckled” – and transmutes them into “beauty [that’s] past change”, because change isn’t necessary by nature of being God’s work?

The central paradox is clear: what may seem humanly imperfect is always perfect to God, because whatever He has created is perfect per se.

This radical re-imagination of aesthetics, then, grants us a more forgiving approach to looking at the world, and should, in turn, give us greater reason to appreciate all the more whatever seems mundane and strange – to see ‘beauty’ in what’s ‘pied’.

in each line sound similar to each other), alternate rhyme (i.e. the last words in every other line sound similar to each other), chain rhyme (i.e. the last word in one stanza sounds similar to the last words in the next stanza), rhyming couplet (i.e. the last word in successive lines sound similar to each other) etc.

Assonance, then, is structurally freer, and so the impression is one of holistic, rather than regular, sonic harmony. In that sense, assonance is more organic, whereas rhyme is comparative more stilted and artificial.

How to write a killer analysis on assonance – reading ‘The Road and the End’ by Carl Sandburg

In general, it’s worth remembering that there is always a dichotomy to assonance. What this means is that on the one hand, assonance’s resemblance to rhyme creates a sense of uniformity, but the lack of pattern in which it appears also conveys a degree of randomness.

The structural tension inherent in assonance, then, makes it ideal for poetry about struggle and conflict, especially the sort between self and society, or inner and outer worlds.

Carl Sandburg’s ‘The Road and the End’ is a good example of this.

In his poem, Sandburg’s speaker expresses his desire to go on a journey by foot – “I shall foot it”, during which he expects to come into close contact with nature.

This desire for solitary freedom, however, isn’t born entirely without guilt. As the poem begins–

I shall foot it

Down the roadway in the dusk,

Where shapes of hunger wander

And the fugitives of pain go by.

Already, we see the first inklings of assonance in “it/fugitives”, “shapes/pain” and “hunger/wander”. But what of it? Despite this scene being a yet-to-be-realised future (“shall”), the speaker tells us that he knows what to expect, at least at the start of his journey – his pursuit for individual freedom with begin with him seeing signs of human tragedy “down the roadway”.

For all the unknowns that will await him in this journey, he understands that to witness “shapes of hunger wander” and “the fugitives of pain” is a regular occurrence in life, one which past travellers have come across, and which future travellers like himself will also encounter.

Compared to the pain and deprivation in the human world, however, the regular patterns in nature are not quite as depressing.

To the speaker, they convey freedom, courage and empowerment, all of which restore a semblance of harmony in a mind conflicted –

I shall foot it

In the silence of the morning,

See the night slur into dawn,

Hear the slow great winds arise

Where tall trees flank the way

And shoulder toward the sky.The broken boulders by the road

Shall not commemorate my ruin.[…]

As the speaker’s visualisation of his journey takes clearer form, elements of nature come together in subtle sonic harmony.

We hear the ‘ee’ (‘in’) sound in “In… morning… into dawn”, the ‘a’ (ey) sound and the ‘ai’ sound in “great winds arise/Where tall trees flank the way/And shoulder toward the sky”; the ‘o’ sound in “shoulder… broken boulders… road”.

Haphazard as the positioning of these assonant words may be, their euphonious sounds pose a moderating counterforce against the descriptions of potential danger by great winds, tall trees, and broken boulders.

As the poem proceeds, the speaker’s internal state moves closer towards the spirit of the external world he sees –

Regret shall be the gravel under foot.

I shall watch for

Slim birds swift of wing

That go where wind and ranks of thunder

Drive the wild processionals of rain.

There’s even more evidence of assonance here: “Regret/gravel”, “slim/swift/wing/wind”, “go/processionals”, “drive/wild” – the overall impression is one of man and nature coming together as one.

Perhaps the speaker is inspired by the fearlessness with which nature embraces the unknown, such as the fragile, but determined, birds headed for a wild thunderstorm. He is, in turn, infected by this demonstration of courage, which he lacks to actually embark on the journey he’s imagining, to remove the future tense of “shall” and realise it in the very present.

He’s aware that there is no room for regret, and is determined to crush it as “gravel under [his] foot”.

And from the way Sandburg ends his poem with a neat assonant pair in the last two-line stanza, we see the speaker’s desire come full circle –

The dust of the travelled road

Shall touch my hands and face.

“The dust/Shall touch”: this parallelism of the “uh” sound is a satisfying one.

In the speaker’s mind, he already sees – to borrow Macbeth’s defining words – ‘the future in the instant’. But instead of death, his future is one of rebirth, of being able to finally be out there in the wild and feel nature blowing against his flesh as a free man.

I hope this post helps you with sound analysis, which you can apply to either poetry or prose.

Let me know in the comment section if you found this useful, and what else you’d like me to write about in the future!