This word set can be confusing, even for word geeks. Let’s start with the basics. A homograph is a word that has the same spelling as another word but has a different sound and a different meaning:

lead (to go in front of)/lead (a metal)

wind (to follow a course that is not straight)/wind (a gust of air)

bass (low, deep sound)/bass (a type of fish)

A homophone is a word that has the same sound as another word but has a different meaning. Homophones may or may not have the same spelling. Here are some examples:

to/two/too

there/their/they’re

pray/prey

Not so bad, right? The ending –graph means drawn or written, so a homograph has the same spelling. The –phone ending means sound or voice, so a homophone has the same pronunciation. But here’s where it gets tricky. Depending on whom you talk to, homonym means either:

A word that is spelled like another but has a different sound and meaning (homograph); a word that sounds like another but has a different spelling and meaning (homophone)

OR

A word that is spelled and pronounced like another but has a different meaning (homograph and homophone)

So does a homonym have to be both a homograph and a homophone, or can it be just one or the other? As with most things in life, it depends on whom you ask.

In the strictest sense, a homonym must be both a homograph and a homophone. So say many dictionaries. However, other dictionaries allow that a homonym can be a homograph or a homophone.

With so many notable resources pointing to the contrary, are we losing this strict meaning? What then will we call a word that is spelled and pronounced the same as another but has a different meaning? If homonym retains all these meanings, how will readers know what is actually meant?

The careful writer would do well to follow the strict sense, ensuring his meaning is understood immediately.

homograph

Use the noun homograph to talk about two words that are spelled the same but have different meanings and are sometimes pronounced differently — like sow, meaning «female pig,» and sow, «to plant seeds.» Continue reading…

homonym

Can you spot the homonyms in the sentence «The baseball pitcher drank a pitcher of water»? A homonym is a word that is said or spelled the same way as another word but has a different meaning. «Write” and “right” is a good example of a pair of homonyms. Continue reading…

homophone

A homophone is a word that sounds the same as another word but has a different meaning and/or spelling. “Flower” and “flour” are homophones because they are pronounced the same but you certainly can’t bake a cake using daffodils. Continue reading…

What are Homo phones?

phones?

Homophones are words that sound the same but have different meanings and different spellings.

The term homo has been derived from a Greek word which means same and phone which means voice.

Example:

Week Weak

There are seven days in a week. The man is very weak.

In the above mentioned examples both week/weak are pronounced the same, but week in the first sentence means a period of seven days whereas weak in the second sentence means not strong.

Uses of Homophones

Homophones are often used to create paronomasia in word plays and games. In order to deceive the players, paronomasias are created. Paronomasia is also very commonly used in poetries. Better known as puns, it is used to create humor in jokes and comedy shows. In a word play, puns are used to suggest multiple meanings of words that sound the same. When word pairs that sound alike (but not identical) are used, it becomes a homophonic pun.

Example:

The phrase used by George Carlin can be cited as an example.

Atheism is a non prophet institution. Here prophet has been used instead of its homophone profit.

Examples of Homophones

Example:

Some examples of commonly used homophones are as follows:

Sea See

The sea is blue in colour. We see with our eyes.

Example:

Wait Weight

Please wait for me! What is your weight?

Example:

Aloud Allowed

They are singing aloud. Dogs are not allowed in children’s play area.

Example:

Flour Flower

What is the price of 1kg of flour? The flower is red in colour.

Example:

Meat Meet

Karan likes to eat meat. Nice to meet you!

Homophones and Contractions

Homophones are words that sound the same but have different spellings and meanings. Shortened versions of words or groups of words are known as contractions. The missing letter in a contracted word is usually marked by a apostrophe. Some common contractions and homophones are mentioned below:

|

Contractions |

Homophones |

|

You’re |

Your |

|

There’s |

Theirs |

|

Here’s |

Hears |

|

Who’s |

Whose |

Difference Between Homophones and Homonyms

Homophones are words that are pronounced similarly but they differ in spelling and meaning. Homonyms are words that sound and spelt the same but differ in meaning. Homonyms can again be divided into three categories. They are homophone (same pronunciation but different spelling/meaning), homograph (same pronunciation and same spelling), Heteronym (same spelling but different pronunciation)

Example:

Homophone: Steel (various forms of metals), steal (to take someone’s property without permission)

Homonym: rock (a large mass of stone), rock (a kind of music)

Difference between Homophones and Homograph

Homophones are words that sound alike but have different meaning and spelling whereas words that are spelt/pronounced the same but have different meaning are called homographs.

Example:

Homophone: pear (a kind of fruit), pair (two identical things)

Homograph: fair (reasonable), fair (complexion)

Want to know more about “Homophones?” Click here to schedule live online session with e Tutor!

About eAge Tutoring:

eAgeTutor.com is the premier online tutoring provider. eAge’s world class faculty and ace communication experts from around the globe help you to improve in an all round manner. Assignments and tasks based on a well researched content developed by subject matter and industry experts can certainly fetch the most desired results for improving spoken English skills. Overcoming limitations is just a click of mouse away in this age of effective and advance communication technology. For further information on online English speaking course or to experience the wonders of virtual classroom fix a demonstration session with our tutor. Please visit www.eagetutor.com.

Contact us today to know more about our spoken English program and experience the exciting world of e-learning.

Reference Links:

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homophone

- http://www.englishclub.com/pronunciation/homophones.htm

- http://www.icteachers.co.uk/children/sats/homophones.htm

- http://www.magickeys.com/books/riddles/words.html

- http://www.dailywritingtips.com/homonyms-homophones-homographs-and-heteronyms/

Michigan-based illustrator Bruce Worden creates funny, witty illustrations of homophones – words that have the same pronunciation but different meanings, spellings, or origins.

A self-professed grammar nerd, Worden explains the differences between the words with minimalist pictograms that visualize their meanings. Over a period of five years, he has created over 300 homophone illustrations on his blog titled Homophones, Weakly (lol). Check out the best ones below.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

Share this post with a friend and voice your views in the comments below. All images © Bruce Worden.

Shutterstock

- There are lots of English language words that are spelled the same but have different meanings.

- A baseball bat and the nocturnal animal bat are good examples of a «homonym.»

- An airy wind and «to wind down» are homographs, too.

Loading

Something is loading.

Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you’re on the go.

It’s no secret that the English language can be tricky. For anyone learning the language, it’s difficult to grasp all the drastic differences a single word can have.

People most get tripped up on words that are too similar. When words are spelled the same and sound the same but have different meanings, then they are called homonyms. When they are just spelled the same but sound different and have different meanings, then they are homographs.

Here are some of the most popular homonyms and homographs in the English language.

Bat

Shutterstock

When used as a noun, a bat could be a winged, nocturnal animal or a piece of sporting equipment used in baseball. It can also be used as a verb when a player goes up to bat during a baseball game.

Compact

Shutterstock

When used as an adjective, «compact» means small, but when used as a verb, it means to make something smaller. It can also be used as a noun when talking about a small case for makeup.

Desert

Janelle Lugge/Shutterstock

As a noun, «desert» is a dry, barren area of land where little rain occurs. When used as a verb, the word means to abandon a person or cause.

Fair

ThomasPhoto/Shutterstock

The word «fair» has a few meanings when used as different parts of speech. When used as an adjective, it can describe someone as agreeable, but it can also describe someone who has light skin or hair. As a noun, a «fair» is typically a local event that celebrates a certain person, place, or historical moment.

Lie

Getty

«Lie» could mean to lay down and to tell something untruthful when used as an adjective. If used as a noun, it is a false statement.

Lead

Shutterstock

The word «lead» could be the verb that means to guide someone or something, while the noun version of the word pertains to the metal.

Minute

Maridav/Shutterstock

The word «minute» can be a measure of time or a measurement of how small something is.

Refuse

Susana Vera/Reuters

To decline or accept something is the verb form of «refuse,» while garbage is the noun form.

Project

Shutterstock

The word «project» has several meanings as a verb. It could mean to plan, to throw, or to cast an image on a surface. As a noun, it is a task or piece of work.

Second

Buda Mendes/ Getty

Like the word «minute,» «second» is another measurement of time, while it can also denote the placement of something after the first.

Fine

Flickr/Charleston’s The Digitel

The word «fine» has several meanings, including two different adjectives. First, it can be used to describe something as high quality and second, it can describe something especially thin. As a noun, «fine» means a payment for a violation.

Entrance

Danny Lawson — WPA Pool/Getty Images

When pronounced slightly differently, the word «entrance» has multiple meanings. As a noun, an entrance is a point of access and entry. It could also be used to describe a dramatic arrival, like a bride at her wedding. However, as a verb, to entrance means to bewitch and delight.

Clip

Alexander Baxevanis/Flickr

The verb form of «clip» can actually get quite confusing. The word can actually mean to cut something apart or to attach together. The word even has a noun form, which is an object that helps attach two things.

Overlook

Colin D. Young/Shutterstock

To overlook means to fail to notice something, but when the word is used as a noun, it is a place where you can look down and see from a higher vantage point.

Consult

Mandate Pictures

«Consult» is another one of those tricky words that have two different meanings and they are opposites of each other. «To consult» can mean to seek advice or to give professional advice.

Row

REUTERS/Erik De Castro

As a noun, a «row» means a fight or disagreement. It could also refer to how something is organized into a line. As a verb, «to row» means to propel a boat forward.

Discount

Mike Kemp/ Getty

As a noun, «discount» is a reduction in price and can also be used as a synonym to «on sale.» But when used as a verb, the word means to underestimate someone or something and give them no value.

Wind

Wikimedia Commons

A subtle difference in pronunciation completely changes the word «wind.» It can refer to a flow of air or it can mean to turn.

Contract

Sean Gallup/Getty Images

When used as a noun, «contract» is a written or verbal agreement, but when used as a verb, it means to acquire or to get.

Read next

Words

Spelling

More…

Homophones are words that sound the same but have different meaning and spellings. You can download and learn homophones with our A-Z List PDF. In English there are many words in that category. You should learn how to use them, most importantly understand them correctly. English words that sound same can be hard for second comers. With some English practice and using those words in context will help you greatly.

I recommend getting some help from dictionaries and using visual cards can help you a lot. You can find some most common English words that look and sound similar with example sentences. Practice can help you to tell the difference between them easily.

1. Difference between Bear-Bare

Bear is a verb. Meaning: to hold up; support; carry

-to bear the weight of the roof.

Bare is an adjective. Meaning:(of a person or part of the body) not clothed or covered.

-bare walls, bare walls

2. Difference between Break-Brake

Break is a verb. Meaning: to smash, split, or divide into parts violently; reduce to pieces or fragments

-He broke a vase.

-She broke her promise.

Brake is a noun. Meaning: anything that has a slowing or stopping effect.

-You should brake your car when you see someone on the road.

3. Difference between Coarse-Course

Coarse is a adjective. Meaning: composed of relatively large parts or particles.

-The beach had rough, coarse sand.

Course is a noun. Meaning: Course: a series of classes you take to learn about a certain subject.

-English course

4. Difference between Desert-Dessert

Desert is a noun. Meaning: a hot, dry land with little rain and few plants or people.

-The Sahara is a vast sandy desert.

Dessert is also a noun. Meaning: cake, pie, fruit, pudding, ice cream, etc., served as the final course of a meal.

-Maybe we should have vanilla ice cream for dessert.

5. Difference between Race-Raise

Race is noun. Meaning: a contest of speed, as in running, riding, driving, or sailing.

-They spent a day at the races.

Raise is a verb. Meaning: to move to a higher position; lift up; elevate.

-Raise your head

6. Difference between Price-Prize

Price is a noun. Meaning: the sum or amount of money or its equivalent for which anything is bought, sold, or offered for sale.

-Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing.

Prize is noun. Meaning: a reward for victory or superiority, as in a contest or competition.

-her invention won first prize in a national contest

7. Difference between Plain-Plane

Plain is an adjective. Meaning: not decorated or elaborate; simple or basic in character.

-good plain food

Plane is a noun. Meaning: a vehicle designed for air travel.

-flying with a plane

8. Difference between Lose-Loose

Lose is a verb. Mostly used with a object. Meaning: suffer a loss or fail to keep something in your possession

-I lose my hat everyday.

-I am losing my mind

Loose is an adjective. Meaning: free or released from fastening or attachment.

-a loose end.

Homophones A-Z List PDF

Homophones-A-Z List PDF – download

You can learn the difference between similar-sounding words in English, the context in which these words are used, along with the relevant examples.

Identical words are quite complex. They almost look alike but they differ in their meanings and contexts. We can also say that some English words have twins. When you learn English vocabulary, you come across different words that are identical, but in reality, they are very different from one another.

Synonyms are words that have very similar meanings but slightly different functions or applications. Instead of simply saying the pasta you had last night was delicious, you could spice things up by using synonyms like tasty, yummy, or even mouthwatering.

In addition to synonyms, there are words with the same spelling and pronunciation but different meanings (homonyms), words that sound the same but are spelled and used differently (homophones), and words with the same spelling but different pronunciations and meanings (homographs).

All these similar words in English are quite confusing and sometimes frustrating as well. We will explore some tips to distinguish these similar words.

1. Use a dictionary regularly

The dictionary is your best language-learning guide. If you are not sure what a word means, look it up in an English-language dictionary.

Keep in mind that a single word can have numerous meanings and applications. A good dictionary or dictionary app will list them all, with context examples. A thesaurus (which lists synonyms for any word) can also aid in the identification of words with similar meanings.

2. Create your own clues about the word

Similar English words can be very complicated, but you can create special cues and images to help you to remember which one is which.

Make an image of something familiar (a person, a thing, or an event) and connect it to the word. When you see the word again, that clue will automatically come to mind, and you will easily remember the difference.

3. Use flashcards to make notes

There are numerous ways to use flashcards as learning tools. Use the flashcard to test yourself by writing the word on one side and its meaning on the other. Flashcards are portable, enabling you to review them when you have free time. Even better, you can create and study with flashcards online.

4. Focus on learning words based on their context

If you only try to remember English words and their definitions, you will quickly become confused. There are several words that are used interchangeably. For example, the words ‘rob’ and ‘steal’ are used interchangeably but their definitions may vary in the dictionary.

The definitions of ‘rob’ and ‘steal’ in the dictionary are:

Rob: “to take personal property from someone by violence or danger”

Steal: “to take the property of another illegally”

Now the two definitions look identical but they vary in their context. To understand the contextual difference, you would need to hear native speakers in real situations. You can also learn the contextual use of English words with italki. Enroll yourself to learn English online with the best and most professional online English tutors who will improve your understanding of similar words in English.

Find Your Perfect Teacher

At italki, you can find your English tutor from all qualified and experienced teachers. Now experience the excellent language learning journey!

Book a trial lesson

The instructors will help you generate your notes for English vocabulary, parts of speech, conjunction, prepositions, and homophones in English with relevant examples and exercises.

Words having similar spellings but different meanings

Coarse/Course

Coarse: (adjective) a rough, not smooth texture.

Example: Is the upper you are wearing smooth or coarse in texture?

Course: (noun) a series of classes taken to learn about a specific subject.

Example: Are you taking any courses to improve your writing skills?

Race/Raise

Race: (verb) compete in a speed contest, such as running or cycling.

Example: My kids enjoy racing each other in school.

Raise: (verb) lift up something like your hand.

Example: If you want chocolate, raise your hand.

Desert/Dessert

Desert: (noun) a hot, dry land with few plants and people (for example, the Sahara)

Example: If you plan to visit the Sahara desert, how much water would you require?

Dessert: (noun) a sweet dish served at the end of a meal (for example, cake)

Example: Maybe we should have dessert at the end of the meal.

Bear/Bare

Bear: (verb) produce outcomes or fruit

Example: This tree will bear fruits this summer.

Bare: (verb) expose or display

Example: When we opened the gate, John’s dog ran up and started to bare its teeth at us.

Break/Brake

Break: (verb) divide something into pieces or cause it to stop working, usually after dropping or misusing it.

Example: Please do not break this expensive glass.

Brake: (verb) slow down or come to an end

Example: You should press the brake of your car at the signal.

Price/Prize

Price: (noun) the amount of money you pay for something.

Example: I did not buy the dress because its price was very high.

Prize: (noun) something offered to conquerors of a competition or contest.

Example: If you want to get first prize, you must work hard.

Lose/Loose

Lose: (verb) suffer a loss or fail to keep something in your ownership.

Example: Please do not lose these papers or you won’t be able to host the meeting.

Loose: (adjective) not tightly or properly fixed.

Example: She is very thin, and this jacket is loose for her.

Plain/Plane/Plan

Plain: (adjective) average, not decorated

Example: This top is too plain. I am not wearing it.

Plane: (noun) short form of airplane

Example: I am traveling to the USA by plane.

Plan: (noun) a thorough program of action.

Example: My plan is to travel to all the nearby places in a month.

Words in English with Similar Meanings

Rob/Steal

Rob: (verb) take something away from someone forcefully.

Example: someone tried to rob John this afternoon.

Steal: (verb) take something away illegally or without consent.

Example: if I leave my bag in the park, someone will definitely steal it.

Cut/Chop

Cut: (verb) divide something into pieces with a knife or any sharp tool.

Example: Please cut the onion into small pieces.

Chop: (verb) cut into many small pieces with recurrent strokes of a knife.

Example: You must chop the garlic before putting it into the pan.

Lend/Borrow

Lend: (verb) give someone short-term use of something in exchange for it being returned later.

Example: Do not worry if you don’t have money, I can lend you some.

Borrow: (verb) accept or demand temporary use of something in exchange for its return later.

Example: I have a Mathematics test tomorrow, can I borrow your calculator?

Hear/Listen

Hear: (verb) become conscious of a sound.

Example: Did you hear the phone ring?

Listen: (verb) pay attention or be aware of a sound.

Example: I like to listen to music when I am sad.

Ice/Snow

Ice: (noun) frozen water

Example: It is so cold that the car is covered with a layer of ice.

Snow: (noun) tiny white frozen droplets of water that fall from the sky.

Example: Snow is expected tonight.

Amount/Number

Amount: (noun) the total number or quantity, used for innumerable things.

Example: you must use this amount of baking powder in the cake.

Number: (noun) the total quantity of units, used for countable things.

Example: The number of passes sold this month is twice the previous month’s passes.

See/Watch/Look

See: (verb) identify by eye or sight

Example: Did you see him taking the book from the shelf?

Watch: (verb) observe responsively.

Example: we are all set to watch a cricket match tonight.

Look: (verb) cast your eye on

Example: Please look at this object before you start sketching.

So, these were some words that look similar and can be very confusing. We hope that the differences are clear to you now. Sometimes, we get confused while using similar words. Such as, a majority of people get confused about whether to use to or too. It requires deep observation and plenty of practice to get a command of these words.

Conclusion

If you are learning English, you must make flashcards for yourself. Practice them on daily basis in your conversations with friends and family. You can also read English books and watch English movies or web series to understand the difference between similar words in English.

Most importantly, keenly observe native speakers while they utter such words. It will help you understand the use of different words based on their context.

Want to learn a language at italki?

Here are the best resources for you!

- Home

- Baks

- Misc

- 15 Words That Sound Similar But Have Different Meaning

- Page 1

»

»

»

»

Wednesday, Jul 6, 2022, 5:55 pm

English language is one of the world’s most spoken languages. It is clean and simple. However, those who are trying to learn English always say it is the most confusing language. We have to agree that some grammar rules in English are little strange. For example, the letter ‘T’ sounds different in three different words not, natural and nation.

Adding more to confusion, some words in English language sound very similar. Some of them even have same pronunciation or spelling. Let us show you fifteen such words that sound similar but have a different meaning.

1.Weather vs. Climate

Weather and climate sound very similar. However, they are two different words.

Weather: Weather is simply the way the atmosphere behaves in a particular region for a short period of time, ranging from a few hours to a few weeks.

Example: It has been raining from morning. The weather is too bad today to go out for shopping.

Climate: Climate is a just a standard weather pattern of a particular area.

Example: When I was new to London, I always had problems adjusting to its climate.

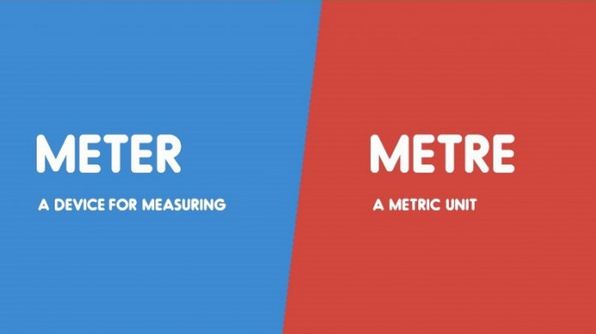

2.Meter vs. Metre

The words meter and metre confuses many people.

Meter: A meter is device that is mainly used to measure stuff. Barometer, thermometer, manometer etc are called meters. The word meter is also the American version of British English word metre.

Example: Jason hopes to find a meter that can measure people’s stupidity.

Metre: Metre is a metric unit that is used to measure distance.

Example: My school is just a few metres away from home.

3.Isle vs. Aisle

Isle and Aisle is another set of homonyms (similar sounding words) that confuses many people.

Isle: The word Isle means an Island, usually a smaller one.

Example: We had great time exploring Caribbean isles last year.

Aisle: The word aisle means a passage between rows of seats in train, airplane, theater or church.

Example: Kelly tripped and fell down while she was walking on a slippery aisle at supermarket.

Homonymy in modern English

Автор: учитель английского языка

Ермилова Елена Александровна

Introduction

Homonyms

are the words different in meaning, but similar in sound.

Homonyms

are used in stilistics as members of stylistic figures called puns.

The

meaning of homonymy is very actual in our days. The appearance of new,

homonymic meanings is one of the main trends in development of Modern English,

especially in its colloquial layer, which, in its turn at high degree is supported

by development of modern informational technologies and simplification of alive

speech.

The

abundance of homonyms is also closely connected with such a characteristic

feature of the English language as the phonetic identity of word and stem or, in

other words, the predominance of free forms among the most frequent roots. It

is quite obvious that if the frequency of words stands in some inverse

relationship to their length, the monosyllabic words will be the most frequent.

Moreover, as the most frequent words are also highly polysemantic, it is only

natural that they develop meanings, which in the coarse of time may deviate

very far from the central one.

In

general, homonymy is intentionally sought to provoke positive, negative or

awkward connotations. Concerning the selection of initials, homonymy with

shortened words serves the purpose of manipulation. The demotivated process of

a shortened word hereby leads to re-motivation. The form is homonymously

identical with an already lexicalized linguistic unit, which makes it easier to

pronounce or recall, thus standing out from the majority of acronyms. This

homonymous unit has a secondary semantic relation to the linguistic unit.

Homonymy of names functions as personified metaphor with the result

that the homonymous name leads to abstraction. The resultant new word

coincides in its phonological realization with an existing word in English.

However, there is no logical connection between the meaning of the acronym and

the meaning of the already existing word, which explains a great part of the

humor it produces.

In the coarse of time the number of homonyms on the whole increases,

although occasionally the conflict of homonyms ends in word loss.

The Object is – lexical

figures.

The Subject is – homonymy

in modern English.

The aim is —to

study homonymy in modern English.

The tasks of the work:

1) to give the determination to homonymy

2) to examine the classification of homonyms

3) to examine distinguishing homonymy and polysemy

4) to learn the literature on the subject

This work consists of: introduction, two chapters and bibliography.

Chapter Ι Homonymy as learning of homonyms

1. Determination of homonymy

Two or more words identical in sound

and spelling but different in meaning, distribution and in many cases origin

are called homonyms. The term is derived from Greek “homonymous”

(homos – “the same” and onoma – “name”) and thus expresses very well the

sameness of name combined with the difference in meaning.

Modern

English is exceptionally rich in homonymous words and word-forms. It is held

that languages where short words abound have more homonyms than those where

longer words are prevalent. Therefore it is sometimes suggested that abundance

of homonyms in Modern English is to be accounted for by the monosyllabic

structure of the commonly used English words.

Not

only words but other linguistic units may be homonymous. Here, however, we are

concerned with the homonymy of words and word-forms only, so we shall not touch

upon the problem of homonymous affixes or homonymous phrases When analyzing

different cases of homonymy we find that some words are homonymous in all their

forms, i.e. we observe full homonymy of the paradigms of two or more different

words as, e.g., in seal a sea animal and seal—a design printed on paper by

means of a stamp’.[3,p144] The paradigm «seal, seal’s, seals, seals'»

is identical for both of them and gives no indication of whether it is seal (1)

or seal (2) that we are analyzing. In other cases, e.g. seal—a sea animal’ and

(to) seal (3)—’to close tightly, we see that although some individual

word-forms are homonymous, the whole of the paradigm is not identical. Compare,

for instance, the-paradigms:

1.

(to)seal-seal-seal’s-seals-seals’

2.

seal-seals-sealed-sealing, etc.

1

Professor O. Jespersen calculated that there are roughly four times as many

monosyllabic as polysyllabic homonyms. It is easily observed that only some of

the word-forms (e.g. seal, seals, etc.) are homonymous, whereas others (e.g.

sealed, sealing) are not. In such cases we cannot speak of homonymous words but

only of homonymy of individual word-forms or of partial homonymy. This is true

of a number of other cases, e.g. compare find [faind], found [faund], found

[faund] and found [faund], founded [‘faundidj, founded [faundid]; know [nou],

knows [nouz], knew [nju:], and no [nou]; nose [nouz], noses [nouziz]; new

[nju:] in which partial homonymy is observed.

From the examples of homonymy discussed above it

follows that the bulk of full homonyms are to be found within the same parts of

speech (e.g. seal(1) n—seal(2) n), partial homonymy as a rule is observed in word-forms

belonging to different parts of speech (e.g. seal n—seal v). This is not to say

that partial homonymy is impossible within one part of speech. For instance in

the case of the two verbs Me [lai]—’to be in a horizontal or resting

position’—lies [laiz]—lay [lei]—lain [lein] and lie [lai]—’to make an untrue

statement’—lies [laiz]—lied [laid]—lied [laid] we also find partial homonymy as

only two word-forms [lai], [laiz] are homonymous, all other forms of the two

verbs are different. Cases of full homonymy may be found in different parts of

speech as, e.g., for [for]—preposition, for [fo:]—conjunction and four [fo:]

—numeral, as these parts of speech have no other word-forms.

2. Classification of homonyms

The

most widely accepted classification is that recognizing homonyms proper,

homophones and homographs.

Homonyms proper

Homonyms proper are words, as I have already mentioned, identical in

pronunciation and spelling, like fast and liver above. Other

examples are: back n ‘part of the body’ – back adv ‘away from the

front’ – back v ‘go back’; ball n ‘a gathering of people for

dancing’ – ball n ‘round object used in games’; bark n ‘the noise

made by dog’ – bark v ‘to utter sharp explosive cries’ – bark n

‘the skin of a tree’ – bark n

‘a

sailing ship’; base n ‘bottom’ – base v ‘build or place upon’ – base

a ‘mean’; bay n ‘part of the sea or lake filling wide-mouth opening of

land’ – bay n ‘recess in a house or room’ – bay v ‘bark’ – bay

n ‘the European laurel’.

The

important point is that homonyms are distinct words: not different meanings

within one word.

Homophones

Homophones are words of the same sound but of different spelling and meaning:

air –

hair; arms – alms; buy – by; him – hymn; knight – night; not – knot; or – oar;

piece – peace; rain – reign; scent – cent; steel – steal; storey – story; write

– right and many others.

In

the sentence The play-wright on my right thinks it right that some

conventional rite should symbolize the right of every man to write as he

pleases the sound complex [rait] is a noun, an adjective, an adverb and a

verb, has four different spellings and six different meanings. The difference

may be confined to the use of a capital letter as in bill and Bill, in the

following example:

“How

much is my milk bill?”

“Excuse

me, Madam, but my name is John.”

On

the other hand, whole sentences may be homophonic: The sons raise meat – The

sun’s rays meet. To understand these one needs a wider context. If you hear

the second in the course of a lecture in optics, you will understand it without

thinking of the possibility of the first.

Homographs

Homographs are words different in sound and in meaning but accidentally

identical in spelling: bow [bou] – bow [bau]; lead [li:d] – lead [led]; row

[rou] – row [rau]; sewer [‘soue] – sewer [sjue]; tear [tie] – tear [tee]; wind [wind] – wind [waind] and many

more.

It

has been often argued that homographs constitute a phenomenon that should be

kept apart from homonymy, as the object of linguistics is sound language. This

viewpoint can hardly be accepted. Because of the effects of education and

culture written English is a generalized national form of expression. An

average speaker does not separate the written and oral form. On the contrary he

is more likely to analyze the words in terms of letters than in terms of

phonemes with which he is less familiar. That is why a linguist must take into

consideration both the spelling and the pronunciation of words when analyzing

cases of identity of form and diversity of content. [10, p12]

Modern

English has a very extensive vocabulary; the number of words according to the

dictionary data is no less than 400, 000.A question naturally arises whether

this enormous word-stock is composed of separate independent lexical units, or

may it perhaps be regarded as a certain structured system made up of numerous

interdependent and interrelated sub-systems or groups of words. This problem

may be viewed in terms of the possible ways of classifying vocabulary items.

Words can be classified in various ways. Here, however, we are concerned only

with the semantic classification of words which gives us a better insight into

some aspects of the Modern English word-stock. Attempts to study the inner

structure of the vocabulary revealed that in spite of its heterogeneity the

English word-stock may be analyzed into numerous sub-systems the members of

which have some features in common, thus distinguishing them from the members

of other lexical sub-systems. Classification into monosynaptic and polysemantic

words is based on the number of meanings the word possesses. More detailed

semantic classifications are generally based on the semantic similarity (or

polarity) of words or their component morphemes. Below we give a brief survey

of some of these lexical groups of current use both in theoretical

investigation and practical class-room teaching.

Accordingly, Professor A.I. Smirnitsky classifieds homonyms into two large

classes:

a)

full homonyms

b)

partial homonyms

Full

homonyms

Full

lexical homonyms are words, which represent the same category of parts of

speech and have the same paradigm.

Match

n – a game, a contest

Match

n – a short piece of wood used for producing fire

Wren

n – a member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service

Wren

n – a bird

Partial

homonyms

Partial homonyms are subdivided into three subgroups:

A.

Simple lexico-grammatical partial homonyms are words, which belong to the same

category of parts of speech. Their paradigms have only one identical form, but

it is never the same form, as will be soon from the examples:

(to)

found v

found v (past indef., past part. of to find)

(to)

lay v

lay v (past indef. of to lie)

(to)

bound v

bound v (past indef., past part. of to bind)

B.

Complex lexico-grammatical partial homonyms are words of different categories

of parts of speech, which have identical form in their paradigms.

Rose

n

Rose

v (past indef. of to rise)

Maid

n

Made

v (past indef., past part. of to make)

Left

adj

Left

v (past indef., past part. of to leave)

Bean

n

Been

v (past part. of to be)

One

num

Won v

(past indef., past part. of to win)

C.

Partial lexical homonyms are words of the same category of parts of speech

which are identical only in their corresponding forms.

to

lie (lay, lain) v

to

lie (lied, lied) v

to

hang (hung, hung) v

to

hang (hanged, hanged) v

to

can (canned, canned)

(I)

can (could)

Chapter

ΙΙ Problems of Homonymy

1. Polysemy and homonymy: etymological

and semantic criteria

Words

borrowed from other languages may through phonetic convergence become

homonymous. Old Norse has and French race are homonymous in Modern English (cf.

race1 [reis]—’running’ and race [reis] ‘a distinct ethnical stock’). There are

four homonymic words in Modern English: sound —’healthy’ was already in Old

English homonymous with sound—’a narrow passage of water’, though

etymologically they are unrelated. Then two more homonymous words appeared in

the English language, one comes from Old French son (L. sonus) and denotes

‘that which is or may be heard’ and the other from the French sunder the

surgeon’s probe. One of the most debatable problems in semasiology is the

demarcation line between homonymy and polysemy, i.e. between different meanings

of one word and the meanings of two homonymous words. [15,p55]

If

homonymy is viewed diachronically then all cases of sound convergence of two

or, more words may be safely regarded as cases of homonymy as, e.g., sound i,

sound2, sound-e, and sound4 which can be traced back to four etymologically

different words. The transition from polysemy to homonymy is a gradual

process, so it is hardly possible to point out the precise stage at which

divergent semantic development tears asunder all ties of etymological kinship

and results in the appearance of two separate words. In the case of flower,

flour, e.g., it is mainly the resultant divergence of graphic forms that gives

us grounds to assert that the two meanings which originally made up the

semantic structure of one word are now apprehended as belonging to two

different words.

Synchronically

the differentiation between homonymy and polysemy is wholly based on the

semantic criterion. It is usually held that if a connection between the various

meanings is apprehended by the speaker, these are to be considered as making up

the semantic structure of a polysemantic word, otherwise it is a case of

homonymy, not polysemy.

Thus

the semantic criterion implies that the difference between polysemy and

homonymy is actually reduced to the differentiation between related and unrelated

meanings. This traditional semantic criterion does not seem to be reliable,

firstly, because various meanings of the same word and the meanings of two or

more different words may be equally apprehended by the speaker as

synchronically unrelated. For instance, the meaning ‘a change in the form of a

noun or pronoun’ which is usually listed in dictionaries as one of the meanings

of case!—’something that has happened’, ‘a question decided in a court of law’

seems to be just as unrelated to the meanings of this word as to the meaning of

case2 —’a box, a container’, etc

Secondly

in the discussion of lexico-grammatical homonymy it was pointed out that some

of the mean of homonyms arising from conversion (e.g. seal in—seal 3 v; paper

n—paper v) are related, so this criterion cannot be applied to a large group of

homonymous word-forms in Modern English. This criterion proves insufficient in

the synchronic analysis of a number of other borderline cases, e.g.

brother—brothers— ‘sons of the same parent’ and brethren—’fellow members of a

religious society’. The meanings may be apprehended as related and then we can

speak of polysemy pointing out that the difference in the morphological

structure of the plural form reflects the difference of meaning. Otherwise we may

regard this as a case of partial lexical homonymy. The same is true of such

cases as hang—hung—hung—’to support or be supported from above’ and

hang—hanged—hanged—’to put a person to death by hanging’ all of which are

traditionally regarded as different meanings of one polysemantic word.

It

is sometimes argued that the difference between related and unrelated meanings

may be observed in the manner in which the meanings of polysemantic words are

as a rule relatable. It is observed that different meanings of one word have

certain stable relationships which are not to be found between the meanings of

two homonymous words. A clearly perceptible connection, e.g., can be seen in

all metaphoric or metonymic meanings of one word (e.g., foot of the man— foot

of the mountain, loud voice—loud colors, etc.,1 cf. also deep well and deep

knowledge, etc.).

Such

semantic relationships are commonly found in the meanings of one word and are

considered to be indicative’ of polysemy. It is also suggested that the

semantic connection may be described in terms of such features as, e.g., form

and function (cf. horn of an animal and horn as an instrument), process and

result (to run—’move with quick steps’ and a run—act of running).

Similar

relationships, however, are observed between the meanings of two homonymic

words, e.g. to run and a run in the stocking.

Moreover

in the synchronic analysis of polysemantic words we often find meanings that

cannot be related in any way, as, e.g., the meanings of the word case discussed

above. Thus the semantic criterion proves not only untenable in theory but also

rather vague and because of this impossible in practice as it cannot be used in

discriminating between several meanings of one word and the meanings of two

different words.

A

more objective criterion of distribution suggested by some linguists is

criteria: undoubtedly helpful, but mainly increase-distribution of lexico —

grammatical and grammatical homonymy. When homonymic words of Context, belong

to different parts of speech they differ not only in their semantic structure,

but also in their syntactic function and consequently in their distribution. In

the homonymic pair paper n—(to) paper v the noun may be preceded by the article

and followed by a verb; (to) paper can never be found in identical

distribution. This formal criterion can be used to discriminate not only

lexico-grammatical but also grammatical homonyms, but it often fails the

linguists in cases of lexical homonymy, not differentiated by means of

spelling.

Homonyms

differing in graphic form, e.g. such lexical homonyms as knight—night or

flower—flour, are easily perceived to be two different lexical units as any

formal difference of words is felt as indicative of the existence of two

separate lexical units. Conversely lexical homonyms identical both in

pronunciation and spelling are often apprehended as different meanings of one

word. It is often argued that the context in which the words are used suffices

to perceive the borderline between homonymous words, e.g. the meaning of case

in several cases of robbery can be easily differentiated from the meaning of

case2 in a jewel case, a glass case. This however is true of different meanings

of the same word as recorded in dictionaries, e.g. of case as can be seen by

comparing the case will be tried in the law-court and the possessive case of

the noun. Thus, the context serves to differentiate meanings but is of little

help in distinguishing between homonymy and polysemy. Consequently we have to

admit that no formal means have as yet been found to differentiate between

several meanings of one word and the meanings of its homonyms. We must take

into consideration the note that in the discussion of the problems of polysemy

and homonymy we proceeded from the assumption that the word is the basic unit

of language.

1

It should be pointed out that there is another approach to the concept of the

basic language unit which makes the problem of differentiation between polysemy

and homonymy irrelevant.

Some

linguists hold that the basic and elementary units at the semantic level of

language are the lexico-semantic variants of the word, i.e. individual

word-meanings. In that case, naturally, we can speak only of homonymy of

individual lexico-semantic variants, as polysemy is by definition, at least on

the synchronic plane, the co-existence of several meanings in the semantic

structure of the word. The criticism of this viewpoint cannot be discussed

within the framework different semantic structure. The problem of homonymy is

mainly the problem of differentiation between two different semantic structures

of identically sounding words.

2.

Homonymy of words and homonymy of individual word-forms may be regarded as full

and partial homonymy. Cases of full homonymy are generally observed in words

belonging to the same part of speech. Partial homonymy is usually to be found

in word-forms of different parts of speech.

3.

Homonymous words and word-forms may be classified by the type of meaning that

serves to differentiate between identical sound-forms. Lexical homonyms differ

in lexical meaning, lexico-grammatical in both lexical and grammatical meaning,

whereas grammatical homonyms are those that differ in grammatical meaning only.

4.

Lexico-grammatical homonyms are not homogeneous. Homonyms arising from conversion

have some related lexical meanings in their semantic structure. Though some

individual meanings may be related the whole of the semantic structure of

homonyms is essentially different.

5.

If the graphic form of homonyms is taken into account, they are classified on

the basis of the three aspects — sound-form, graphic form and meaning — into

three big groups: homographs (identical graphic form), homophones (identical

sound-form) and perfect homonyms (identical sound- and graphic form).

6.

The two main sources of homonymy are:

1)

diverging meaning development of one polysemantic word, and

2)

convergent sound development of two or more different words. The latter is the

most potent factor in the creation of homonyms.

7.

The most debatable problem of homonymy is the demarcation line between homonymy

and polysemy, i.e. between different meanings of one word and the meanings of

two or more phonemically different words.

8.

The criteria used in the synchronic analysis of homonymy are:

1)

the semantic criterion of related or unrelated meanings;

2)

the criterion of spelling;

3)

the criterion of distribution, and

4)

the criterion of context.

In

grammatical and lexico-grammatical homonymy the reliable criterion is the

criterion of distribution. In lexical homonymy there are cases when none of the

criteria enumerated above is of any avail. In such cases the demarcation line

between polysemy and homonymy is rather fluid.’

9.

The problem of discriminating between polysemy and homonymy in theoretical

linguistics is closely connected with the problem of the basic unit at the

semantic level of analysis.

In

applied linguistics this problem is of the greatest importance in lexicography

and also in machine translation.

During

several scores of years the problem of distinction of polysemy and homonymy in

a language was constantly arising the interest of lexicologists is in many

countries.

2. Distinguishing homonymy from

polysemy

The

synchronic treatment of English homonyms brings to the forefront a set of

problems of paramount importance for different branches of applied linguistics:

lexicography, foreign language teaching and information retrieval. These

problems are: the criteria distinguishing homonymy from polysemy, the

formulation of rules for recognizing different meanings of the same homonym in

terms of distribution, and the description of difference between patterned and

non-patterned homonymy. It is necessary to emphasize that all these problems

are connected with difficulties created by homonymy in understanding the

message by the reader or listener, not with formulating one’s thoughts; they

exist for the speaker though in so far as he must construct his speech in a way

that would prevent all possible misunderstanding.

All three problems are so closely

interwoven that it is difficult to separate them. So we shall discuss them as

they appear for various practical purposes. For a lexicographer it is a problem

of establishing word boundaries. It is easy enough to see that match, as

in safety matches, is a separate word from the verb match ‘to

suit’. But he must know whether one is justified in taking into one entry match,

as in football match, and match in meet one’s match ‘one’s

equal’.

On the synchronic level, when

the difference in etymology is irrelevant, the problem of establishing the

criterion for the distinction between different words identical in sound form,

and different meanings of the same word becomes hard to solve. Nevertheless the

problem cannot be dropped altogether as upon an efficient arrangement of

dictionary entries depends the amount of time spent by readers in looking up a

word: a lexicographer will either save or waste his readers’ time and effort.

Actual solutions

differ. It is a wildly spread practice in English lexicography to combine in

one entry words of identical phonetic form showing similarity of lexical

meaning or, in other words, revealing a lexical invariant, even if they belong

to different parts of speech. In our country a different trend has settled.

Polysemy characterizes words that have more than one meaning — any dictionary

search will reveal that most words are polysemes — word itself has 12

significant senses, according to WordNet. This means that the word,

word, is used in texts scanned by lexicographers to represent twelve different

concepts.

The point is that words are

not meanings, although they can have many meanings. Lexicographers make a

clear distinction between different words by writing separate entries for each

of them, whether or not they are spelled the same way. The dictionary of Fred

W. Riggs has 5 entries for the form, bow — this shows that

lexicographers recognize this form (spelling) as a way of representing five

different words. Three of them are pronounced bo and two bau, which identifies two

homophones in this set of five homographs, each of which is a polyseme, capable

of representing more than one concept. To summarize: bow is a word-form that

stands for two different homophones and, as a homograph, represents five

different words.

Moreover, the form bow

is polysemic and can represent more than 20 concepts (its various meanings or

senses). By gratuitously putting meaning in its definition of a homograph, WordNet

can mislead readers who might think that a word is a homonym because it has

several meanings — but having one word represent more than one concept is

normal — just consider term as an example: it can not only refer to the

designator of a concept, but also the duration of something, like the school

year or a politician’s hold on office, a legal stipulation, one’s standing in a

relationship (on good terms) and many other notions — more than 17 are

identified in the dictionary edited be Fred W. Riggs. By contrast, homonyms are

different words and each of them (as a polyseme) can have multiple meanings.

To make their definitions precise, lexicographers need

criteria to distinguish different words from each other even though they are

spelled the same way. This usually hinges on etymology and, sometimes, parts of

speech. One might, for example, think that that firm ‘steadfast’ and firm

‘business unit’ are two senses of one word (polyseme). Not so! Lexicographers

class them as different words because the first evolved from a Latin stem

meaning throne or chair, and the latter from a different root in Italian

meaning signature.

Dictionaries are not uniform in their treatment of the

different grammatical forms of a word. In some of them, the adjective firm

(securely) is handled as a different word from the noun firm (to settle)

even though they have the same etymology. Fred W. Riggs isn’t persuaded such

differences justify treating grammatical classes (adjectives, nouns, and verbs)

of a word-form that belongs to a single lexeme as different words — the

precise meaning of lexeme is 1. WordNet is a Lexical Database for

English prepared by the Cognitive Science Laboratory at Princeton University.

explained below. The relevant point here is that deciding

whether or not a form identifies one or more than one lexeme does not hinge on meanings.

There is agreement that a word-form represents different words when they

evolved from separate roots, and some lexicographers treat each grammatical use

of a lexeme (noun, verb, adjective) as though it were a different word.

The etymological criterion may lead to distortion of the

present day situation. The English vocabulary of today is not a replica of the

Old English vocabulary with some additions from borrowing. It is in many

respects a different system, and this system will not be revealed if the

lexicographers guided by etymological criteria only.

A more or less simple, if not very rigorous, procedure

based on purely synchronic data may be prompted by analysis of dictionary

definitions. It may be called explanatory transformation. It is based on

the assumption that if different senses rendered by the same phonetic complex

can be defined with the help of an identical kernel word-group, they may be

considered sufficiently near to be regarded as variants of the same word; if

not, they are homonyms.

Consider the following set of examples:

1.

A child’s voice is heard.1

2.

His voice…was…annoyingly well-bred.2

3.

The voice-voicelessness

distinction…sets up some English consonants in opposed pairs…

4.

In the voice contrast of active and

passive…the active is the unmarked form.

The first variant (voice1) may be

defined as ‘sound uttered in speaking or singing as characteristic of a

particular person’, voice2 as ‘mode of uttering sounds in

speaking or singing’, voice3 as ‘the vibration of the vocal chords

in sounds uttered’. So far all the definitions contain one and the same kernel

element rendering the invariant common basis of their meaning. It is, however,

impossible to use the same kernel element for the meaning present in the fourth

example. The corresponding definition is: “Voice – that form of the verb that

expresses the relation of the subject to the action”. This failure to satisfy

the same explanation formula sets the fourth meaning apart. It may then be

considered a homonym to the polysemantic word embracing the first three

variants. The procedure described may remain helpful when the items considered

belong to different parts of speech; the verb voice may mean, for

example, ‘to utter a sound by the aid of the vocal chords’.

This brings us to the problem of patterned homonymy,

i.e. of the invariant lexical meaning present in homonyms that have developed

from one common source and belong to various parts of speech.

Is a lexicographer justified in placing the verb voice

with the above meaning into the same entry with the first three variants of

the noun? The same question arises with respect to after or before

– preposition, conjunction and adverb.

English lexicographers think it quite possible for one

and the same word to function as different parts of speech. Such pairs as act

n – act v; back n — back v; drive n – drive v;

the above mentioned after and before and the like, are all

treated as one word functioning as different parts of speech. This point of

view was severely criticized. It was argued that one and the same word could

not belong to different parts of speech simultaneously, because this would

contradict the definition of the word as a system of forms.

This viewpoint is not faultless

either; if one follows it consistently, one should regard as separate words all

cases when words are countable nouns in one meaning and uncountable in another,

when verbs can be used transitively and intransitively, etc. In this case hair1

‘all the hair that grows on a person’s head’ will be one word, an uncountable

noun; whereas ‘a single thread of hair’ will be

denoted by another word (hair2)

which, being countable, and thus different in paradigm, cannot be considered

the same word. It would be tedious to enumerate all the absurdities that will

result from choosing this path. A dictionary arranged on these lines would

require very much space in printing and could occasion much wasted time in use.

The conclusion therefore is that efficiency in lexicographic work is secured by

a rigorous application of etymological criteria combined with formalized

procedures of establishing a lexical invariant suggested by synchronic

linguistic methods.

As to those concerned with

teaching of English as a foreign language, they are also keenly interested in

patterned homonymy. The most frequently used words constitute the greatest

amount of difficulty, as may be summed up by the following jocular example: I

think that this “that” is a conjunction but that that “that” that that man used

as pronoun.

A correct understanding of this

peculiarity of contemporary English should be instilled in the pupils from the

very beginning, and they should be taught to find their way in sentences where

several words have their homonyms in other parts of speech, as in Jespersen’s

example: Will change of air cure love? To show the scope of the problem

for the elementary stage a list of homonyms that should be classified as

patterned is given below:

Above, prp, adv, a; act,

n, v; after, prp, adv, cj; age, n, v; back, n, adv, v; ball,

n, v; bank, n, v; before, prp, adv, cj; besides, prp, adv;

bill, n, v; bloom, n, v; box, n, v. The other examples

are: by, can, close, country, course, cross, direct, draw, drive, even,

faint, flat, fly, for, game, general, hard, hide, hold, home, just, kind, last,

leave, left, lie, light, like, little, lot, major, march, may, mean, might,

mind, miss, part, plain, plane, plate, right, round, sharp, sound, spare,

spell, spring, square, stage, stamp, try, type, volume, watch, well, will.

For the most part all these words

are cases of patterned lexico-grammatical homonymy taken from the minimum

vocabulary of the elementary stage: the above homonyms mostly differ within

each group grammatically but possess some lexical invariant. That is to say, act

v follows the standard four-part system of forms with a base form act,

an s-form (act-s), a Past Indefinite Tense form (acted) and an

ing-form (acting) and takes up all syntactic functions of verbs, whereas

act n can have two forms, act (sing.) and act (pl.). Semantically

both contain the most generalized component rendering the notion of doing

something.

Recent investigations have shown

that it is quite possible to establish and to formalize the differences in

environment, either syntactical or lexical, serving to signal which of the

several inherent values is to be ascribed to the variable in a given context.

An example of distributional analysis will help to make this point clear.

The distribution of a

lexico-semantic variant of a word may be represented as a list of structural

patterns in which it occurs and the data on its combining power. Some of the

most typical structural patterns for a verb are: N + V + N; N + V + Prp + N; N

+ V + A; N + V + adv; N + V + to + V and some others. Patterns for nouns are

far less studied, but for the present case one very typical example will

suffice. This is the structure: article + A + N.

In the following

extract from “A Taste of Honey” by Shelagh Delaney the morpheme laugh

occurs three times: I can’t stand people who laugh at other people. They’d

get a bigger laugh, if they laughed at themselves.

We recognize laugh

used first and last here as a verb, because the formula is N + laugh +

prp + N and so the pattern is in both cases N + V + prp + N. In the beginning

of the second sentence laugh is a noun and the pattern is article +

A + N.

This elementary example

can give a very general idea of the procedure which can be used for solving

more complicated problems.

We may sum up our

discussion by pointing out that whereas distinction between polysemy homonymy

is relevant and important for lexicography it is not relevant for the practice

of either human or machine translation. The reason for this is that different

variants of a polysemantic word are not less conditioned by context then

lexical homonyms. In both cases the identification of the necessary meaning is

based on the corresponding distribution that can signal it and must be present

in the memory either of the pupil or the machine. The distinction between

patterned and non-patterned homonymy, greatly underrated until now, is of far

greater importance. In non-patterned homonymy every unit is to be learned

separately both from the lexical and grammatical points of view. In patterned

homonymy when one knows the lexical meaning of a given word in one part of

speech, one can accurately predict the meaning when the same sound complex

occurs in some other part of speech, provided, of coarse, that there is

sufficient context to guide one.

Conclusion

We

have come to conclusion that:

1.Homonyms

are the words identical in sound and spelling, but different in meaning.

Modern

English is exceptionally rich in homonymous words and word-forms. It is held

that languages where short words abound have more homonyms than those where

longer words are prevalent. Therefore it is sometimes suggested that abundance

of homonyms in Modern English is to be accounted for by the monosyllabic

structure of the commonly used English words.

2.Homonyms

are classifiable into:

-homophones

— homographs

— homonyms proper

Homophones

are the words of the same sound but of different spelling and meaning.

Homographs

are words different in sound and in meaning, but accidentally identical in

spelling.

Homonyms

proper are words identical in pronunciation and spelling.

3. Synchronically the differentiation

between homonymy and polysemy is wholly based on the semantic criterion. It is

usually held that if a connection between the various meanings is apprehended

by the speaker, these are to be considered as making up the semantic structure

of a polysemantic word, otherwise it is a case of homonymy, not polysemy.

Thus

the semantic criterion implies that the difference between polysemy and

homonymy is actually reduced to the differentiation between related and

unrelated meanings. This traditional semantic criterion does not seem to be

reliable, firstly, because various meanings of the same word and the meanings

of two or more different words may be equally apprehended by the speaker as

synchronically unrelated.

4.Having

learned the literature , we have come to conclusion that great contribution to

lexicology was brought by: Akhmanova O.S, Potter S., Smirnitsky A.I.

Bibliography

1 Abayev

V.I. Homonyms T. O’qituvchi 1981 p. 29

2. Akhmanova

O.S. Lexicology: Theory and Method. M. 1972 p. 59

3.Arakin English Russian Dictionary

M.Russky Yazyk 1978 p. 119

4. Arnold

I.V. The English Word M. High School 1986 p. 143

5. Bloomsbury Dictionary of New Words. M. 1996 p.276

6. Buranov, Muminov

Readings on Modern English Lexicology T. O’qituvchi 1985 p. 47

7. Burchfield R.W.

The English Language. Lnd. ,1985 p.47

8. Canon G.

Historical Changes and English Wordformation: New Vocabulary items. N.Y., 1986.

p.284

9. Dubenets E.M.

Modern English Lexicology (Course of Lectures) M., Moscow State Teacher

Training University Publishers 2004 p. 31

10. Ginzburg

R.S. et al. A Course in Modern English Lexicology. M., 1979 p. 82

11 .Halliday

M.A.K. Language as Social Semiotics. Social Interpretation of Language and

Meaning. Lnd., 1979.p.53

12. Hornby

The Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English. Lnd. 1974 p. 111

13 . Howard

Ph. New words for Old. Lnd., 1980. p.311

14. Jespersen.

Linguistics. London, 1983, p. 412

15. Jespersen

,Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. Oxford, 1982 p. 249

16. Longman

Lexicon of Contemporary English. Longman. 1981p.23

17. Maurer

D.W. , High F.C. New Words — Where do they come from and where do they go.

American Speech., 1982.p.171

18. Potter

S. Modern Linguistics. Lnd., 1957 p. 54

19. Schlauch,

Margaret. The English Language in Modern Times. Warszava, 1965. p.342

20. Sheard,

John. The Words we Use. N.Y..,1954.p.3

21. Smirnitsky A.I.

Homonyms in English M.1977 p. 90

22. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English. Oxford 1964, p.147

23. Aпресян Ю.Д.Лексическая семантика. Омонимические

средства языка. М.1974. 46c.

24. Арнольд

И.В. Лексикология современного английского языка.М. Высшая школа 1959.- 212c.

25. Беляева

Т.М., Потапова И.А. Английский язык за пределами Англии. Л. Изд-во ЛГУ 150c.

26. Виноградов

В. В. Лексикология и лексикография. Избранные труды. М.

1977- .122c

Homophones are words that sound the same but are different in meaning or spelling. Homographs are spelled the same, but differ in meaning or pronunciation. Homonyms can be either or even both. To help remember, think of the etymology: homophones have the same sound (the Greek phonos), homographs have the same spelling (Greek graphein), and homonym comes from the Greek word meaning «name» (onyma).

NOT pronounced like the front of a ship.

There are many aspects of the English language that might be described as tricky, or even vexatious. Among these are the large number of words that are spelled differently but which sound the same. Or all the words which are spelled the same but don’t sound the same at all. Or the fact that there is a single word which describes these two very different types of words. Welcome to homophones, homographs, and homonyms.

Homophones vs. Homographs vs. Homonyms

Here is the simplest explanation we can give for each of these words:

Homophones are words that sound the same but are different.

Homographs are words that are spelled the same but are different.

Homonyms can be homophones, homographs, or both.

Here is a slightly less simple explanation for each of these words:

Homophones are words pronounced alike but different in meaning or derivation or spelling. These words may be spelled differently from each other (such as to, too, and two), or they may be spelled the same way (as in quail meaning ‘to cower’ and quail meaning a type of bird).

Homographs are words that are spelled alike but are different in meaning or derivation or pronunciation. Sometimes these words sound different (as in the bow of a ship, and the bow that shoots arrows), and sometimes these words sound the same (as in quail meaning ‘to cower’ and quail meaning a type of bird).

Homonym may be used to refer to either homophones or to homographs. Some people feel that the use of homonym should be restricted to words that are spelled alike but are different in pronunciation and meaning, such as the bow of a ship and the bow that shoots arrows.

Tricks for Keeping them Apart

If you would like to distinguish between these words but have trouble remembering their differences, etymology can be of assistance. All of these words are formed with the combining form homo-, meaning “one and the same; similar; alike,” and each has an additional root that sheds light on the word’s meaning. Homophone comes from the Greek -phōnos (meaning “sounding”); homograph is from the Greek graphein (“to write”); homonym is from the Greek onyma (meaning “name”).