Our languages are incredibly diverse and it is highly unlikely to find a word or a handful of words that sound the same in all languages. Except that there is a word that is shared by all human languages, according to research. Surprise, surprise..the word is ‘huh’. Weird, huh! Well, it turns out that this is probably a universal word.

Let’s explain first how this word works in more detail. Consider the following made-up conversation:

A: We decided to move to New York.

B: Where?

A: To New York.

Speaker A makes a statement, and Speaker B follows up on that by asking the question “Where?” which targets only a portion of the original statement, i.e., it is possible to infer that Speaker B had no trouble comprehending the message that they decided to move somewhere, but s/he presumably missed the final word. So, s/he requested a repetition of this information by asking “where?” and Speaker A supplied this information in his/her next turn. And this is what is termed by conversation analysts as repair.

But, what if, for some reason (i.g. extreme background noise), speaker B failed to comprehend the whole statement and wanted to request the repetition of the whole statement? How do you think the dialogue would have unfolded in this case? That’s where the word huh comes in. Take the following dialogue:

A: We decided to move to Alaska.

B: Huh?

A: We decided to move to Alaska.

Huh is a very specific repair strategy that does not traget some part of the statement but rather the statement as a whole. That is why repairs that are provided as a response for a huh are quite long and elaborate, typically reiterating the whole statement.

Now, here is the fun part. The word huh may very well be a universal word that is shared by all human languages. Conversation analysts Mark Dingemanse, Francisco Torreira and Nick Enfield, at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, conducted an interesting cross-linguistic study in which they have shown that huh is possibly a universal word. They recorded bits of informal conversation from 31 dialects across 5 continents and suggested that the word ‘huh’ (and its variants) is possibly a universal repair initiator that exists in all languages, performs the same function and sounds roughly the same across languages. Here is a sketchy illustration:

This study has had great importance in the humanities. It has enlightened us with how conversations work cross-culturally and unraveled important subtleties in human communication. That is why it is not surprising that the authors have been awarded an Ig Nobel Prize.

References:

1. Is “Huh?” a Universal Word? Conversational Infrastructure and the Convergent Evolution of Linguistic Items

2. Ig Nobel prize for MPI researchers

3.How We Talk: The Inner Workings of Conversation: N. J. Enfield: 9780465059942: Amazon.com: Books

By words we learn thoughts, and by thoughts we learn life.

Jean Baptiste Girard

READ MORE

You may have noticed that there are words in English that are very similar to, or even the same as, words in French. To describe something weird, an English-speaker could say it is bizarre. People eat at places such as restaurants and cafés in English-speaking parts of the world. My friend’s mom in New York gets the chauffeur to drive her places since she doesn’t drive herself. Both the spelling and the meaning of these words are the same in French as in English. The above words came to English via French, although some have even earlier origins in other languages, such as the words café and bizarre, which come from the Italian caffe and bizarro. With all these similarities, does it mean that French should be a breeze for those who are already familiar with English? Maybe. Let’s take a closer look.

The percentage of words shared by the English and French languages is significant. Different sources give different numbers, with Wikipedia placing this at over a third, a statistic corroborated by an article written by Françoise Armand and Érica Maraillet titled “Éducation interculturelle et diversité linguistique” for the University of Montréal’s ÉLODiL website.

Both French and English have significant Latin roots, thus accounting for the high number of cognates, words that have a common etymology. Although English draws directly from Latin in some cases, as with the word stultify, which is related to stultus, many words of Latin origin have passed into English via French. The influence of French on the English language is due in large part to the Norman invasion of England in 1066, a conquest that resulted in dialects of Old English being displaced by Norman French, particularly among the elite classes.

The use of French in English-speaking regions continued throughout the Middle Ages and was reinforced by a surge in popularity during the renaissance of French literature in the 13th and 14th centuries. Words found in many works that describe chivalry, fealty, and courtly love have French origins and are still present in the English lexicon; likewise there are many words whose Renaissance French spelling looks like that of its English counterparts. A hospital in Renaissance French is a hôpital in modern French. Likewise, a forest is a forêt and a beste is a bête.

| English | Renaissance French |

|---|---|

| forest | forêt |

| beste | bête |

The replacement of an ‘s’ appearing before a consonant by the accent circonflexe, a graphic transition that took place during the Renaissance, likely reflects a change in pronunciation from very early spoken forms of French, as well as from the Latin forms of corresponding words, as Bernard Cerquiligni notes in his 1995 work, L’Accent du souvenir. An interesting aspect of this spelling change is that it reflects phonetic changes that likely occurred around 1066, also noted by Cerquiligni. And it was only in 1740 that the Académie française formally introduced the circumflex accent into the French lexicon, with the third publication of its dictionary. A seven hundred year period of deliberating over a spelling change that would reflect a phonetic change in everyday speech illustrates the peculiar relationship French speakers have with their language. If this is the amount of thought, reflection, and argument French speakers have among themselves concerning their own language, it should not be surprising for those learning French to encounter a certain amount of skepticism and questioning as well, as they embark on this linguistic journey.

English Words with French Origins in Food

French terminology continues to be used in fields that have seen great developments within French-speaking contexts, such as cuisine, fashion, and visual art. People in English-speaking parts of the world regularly eat foods they refer to as omelettes and mousse. They may order escargots from a menu, perhaps a more appetizing term than snails. Menu is another word that has come to English via French, referring to a detailed list of components of a meal, with origins in the Latin word minutus, for smaller. In addition to food items, English speakers regularly refer to couture when talking about fashion, and describe stylish items as chic.

English Words with French Origins in Visual Arts

Visual art uses many French terms, such as trompe l’œil and aquarelle. Even the term fin de siècle is used to denote the late 19th / early 20th century time period during which France had a great influence on artistic and cultural movements. Performing arts terminology has also been influenced by French, with French terms being used for classical ballet. The origins of this dance form can be found in the French court, with the first ballet performed at the Louvre for the wedding of the duc de Joyeuse to Mlle de Vaudémont on 15 October 1581 in the grande salle du Petit-Bourbon, according to the Encyclopædia Universalis. Later, in 1661, Louis XIV founded the Académie royale de danse, which established ballet terminology as a codified vocabulary of set movements to be studied as the basis for many works that have been developed in this domain. French is indeed the lingua franca of ballet and continues to be present in ballet schools worldwide and used by choreographers as they set their works on companies around the globe.

While the similarities between words in the French and English languages seem encouraging, there are several caveats to keep in mind, not least of which are the subtle spelling changes that occur between the French and English versions of certain cognates. These include: connexion and connection, adresse and address, correspondance and correspondence, agressive and aggressive, bagage and baggage, danse and dance, mariage and marriage, futur and future, to name a few. To make things even more confusing, there are different spellings for certain cognates in different parts of the English-speaking world that correspond to the same French counterpart, e.g., license, which is used in the US for the French licence, but is spelled licence in the UK and Canada, at least when denoting the noun referring to a legal document granting permission to own, use, or do something. As a verb, the spelling license is used across the board in the English-speaking world. Such details reflect regional changes that have contributed to the development of vocabulary used by linguistic populations and illustrate the various paths these words have taken through time and geographic space.

In addition to being affected by French, the English language isn’t shy to borrow words from other languages. Words such as manga, zero, waltz, glitch, and moccasin are from Japanese, Arabic, German, Yiddish, and Algonquian, respectively. Something interesting to note is that, whereas English has borrowed words from other languages for centuries, it may now be lending more than borrowing, according to Philip Durkin, deputy chief editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, in a 3 February 2014 BBC article. This turn of events is likely linked to developments in domains such as business and technology, which have largely taken place in English-speaking contexts.

Read More:

- French Film Awards and 20+ Movie Terms that You Should Know

- Tips for Translating from French

- Structural Difficulties and Solutions when Learning French

- Follow Glossika on YouTube / Instagram / Facebook

Subscribe to The Glossika Blog

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox

- Авторы

- Руководители

- Файлы работы

- Наградные документы

Калошин Н.А. 1

1МАОУ «СОШ № 32»

Бернер А.Г. 1

1МАОУ «СОШ № 32»

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

International Words in the Russian and English Languages

Introduction

Expanding global contacts and the development of mass media, especially the Internet, result in the considerable growth of international vocabulary. All languages depend for their changes upon the cultural and social matrix in which they operate and various contacts between nations are part of this matrix reflected in vocabulary. International words play an especially prominent part in various terminological systems including the vocabulary of science, industry and art. The etymological sources of this vocabulary reflect the history of world culture.

The research question:to find out the percentage of international words used in the Lifestyle-Politics category via analysis of the news article.

The objectives of this research are:

to identify the difference between internationalisms and cognates

to study the origin of some international words

to design an educational wall poster on the top ten words in the Lifestyle-Politics category.

Topicality of the project

The percentage of internationalisms in the news articles and in the scientific texts is rather high, e.g. according to some linguists, in the Russian vocabulary there are more than 10 per cent of international words. They are the most easily recognizable and perceived when reading these kinds of texts. The study of international words and their origin can be very useful for those who are interested in politics and science.

Definitions

Internationalism – or international word in linguistics is a loanword that occurs in several languages with the same or at least similar meaning and etymology. These words exist in ‘several different languages as a result of simultaneous or successive borrowings from the ultimate source’ [http://en.academic.ru/].

Cognate — A word either descended from the same base word of the same ancestor language as the given word, or strongly believed to be a regular reflex of the same reconstructed root of proto-language as the given word [ http://en.wiktionary.org/ ].

Background information

One of the first linguists to pay attention to the existence of some similar words in European languages was Antoine Meillet, a French linguist of the early 20th century, one of the most influential comparative linguists of his time. He steadily emphasized that any attempt to account for linguistic change must recognize that language is a social phenomenon. He supported the use of an international auxiliary language and at the beginning of the 20h century he studied the origin of some international words. A lot of internationalisms were considered to have originated from Latin and Greek.

The cross-linguistic influence was the subject of investigation of Lev Shcherba, a Russian linguist and lexicographer specializing in phonetics and phonology.

Uriel Weinreich, a Polish-American linguist, first noted that learners of second languages consider linguistic forms from their first language equal to forms in the target language. However, the essential inequality of these forms leads to speech which the native speakers of the target language consider unequal.

Einar Haugen, Armin Schwegler, А.А. Bukov, L.A. Tarasova and some other linguists made a contribution to the study of cross-linguistic influence.

The rate of change in technology, political, social and artistic life has been greatly accelerated in the 20th century and so has the rate of growth of international word stock. A few examples of comparatively new words due to the progress of science will suffice to illustrate the importance of international vocabulary: algorithm, antenna, antibiotic, automation, bionics, cybernetics, entropy, gene, genetic code, graph, microelectronics, quant, quasars, pulsars, ribosome, etc.

Nowadays a great number of English words are to be found among the internationalisms e.g. bank, business, consult, design, disk, drive, hit, man, market, media, net, style, test etc. The English vocabulary penetrates into other languages. We find numerous English words in the field of sport: football, out, match, tennis, volley-ball, basketball, cricket, golf, time in different parts of the world.It is due to the prestigious of the English language and its status of a global language.

Internationalisms vs Cognates

In the 1950th it was decided to differentiate the internationalisms and the cognates. It was stated that the word could be described as international if:

no fewer than three languages use it.

its spelling and pronunciation is completely or partly similar in different languages so that the word is understandable between the different languages.

its meaning is the same in different languages.

So, Internationalism – or international word in linguistics is a loanword that occurs in several languages with the same or at least similar meaning and etymology. These words exist in ‘several different languages as a result of simultaneous or successive borrowings from the ultimate source’ [http://en.academic.ru/].

European internationalisms originate primarily from Latin or Greek, but from other languages as well. Many non-European words have also become international, often by the way of one or more European languages.

Internationalisms often spread together with the innovations they designate. Accordingly, there are semantic fields of internationalisms that are dominated by specific languages, e.g. the computing vocabulary which is mainly English with internationalisms such as computer, disk, spam. New inventions, political institutions, food stuffs, leisure activities, science, and technological advances have all generated new lexemes and continue doing it.

Internationalisms are often spread by speakers of one language living in geographical regions where other languages are spoken.

In linguistics, cognates are words that have a common etymological origin. This learned term

derives from the Latin cognatus (blood relative).

Cognates do not need to have the same meaning, which may have changed as the languages developed separately. For example, consider English starve and Dutch sterven or German sterben («to die»); these three words all derive from the same Proto-Germanic root, *sterbaną («die»). English dish and German Tisch («table»), with their flat surfaces, both come from Latin discus, but it would be a mistake to identify their later meanings.

Cognates also do not need to have obviously similar forms: e.g., English father, French père, and Armenian hayr all descend directly from Proto-Indo-European *ph₂tḗr.

So, Cognate — A word either descended from the same base word of the same ancestor language as the given word, or strongly believed to be a regular reflex of the same reconstructed root of proto-language as the given word [ http://en.wiktionary.org/ ].

Analysis of the News Article

The following article is taken from the CNN official site (homepage). The underlined words can be described either as internationalisms or cognates. Some of them are proper names, geographical names or numerals.

Ukraine crisis centerstage as Obama, EU leaders meet in Belgium

By Laura Smith-Spark, CNN

March 26, 2014 — Updated 1243 GMT (2043 HKT)

(CNN)— The rapidly unfolding crisis in Ukraine is set to be the focus of talks between U.S. PresidentBarack Obama and European Union leaders Wednesday in Brussels, Belgium.

Russia’s formal annexation last week of Ukraine’s Crimea region has sparked the biggest East-West confrontation since the end of the Cold War.

Meanwhile, Moscow’s massing of troops near Ukraine’s eastern borders has worried the interim government in Kiev, as well as causing ripples of concern in other former Soviet republics that now belong to the EU and NATO.

Wednesday’s EU-U.S. summit in Brussels comes on the heels of talks on the sidelines of a nuclear security summit in The Hague, the Netherlands.

Obama will also meet with NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen while in Brussels.

Speaking at The Hague on Tuesday, Obama said Russia had a way out of tensions over the crisis: Negotiate with Kiev and be prepared to «act responsibly» and respond to international norms, such as respecting Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

If Russia doesn’t act responsibly, «there will be additional costs» that could hurt the global economy but will affect Russia most of all, Obama said.

The U.S. president said Russia’s annexation of Crimea «is not a done deal» because it’s not internationally recognized.

But he acknowledged that the Russian military controls Crimea, and said the world can make sure, through diplomacy and sanctions, that Russia pays a price.

Ukraine: We need support

Russia insists its actions are legitimate and denies having used its armed forces in Crimea, saying the troops that took control of key installations were local «self-defense» forces.

Russia also insists the government in Kiev is illegitimate because ousted President ViktorYanukovych, a close ally of Moscow’s, was forced out in an armed coup. Yanukovych’s ouster followed months of street protests sparked by his decision to ditch an EU trade deal in favor of closer ties to Russia.

In an interview Tuesday with PBS, acting Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk said Ukraine is struggling to maintain a fighting capability after it was «deliberately dismantled» under Yanukovych.

«What we need is support from the international community. We need technology and military support to overhaul the Ukrainian military and modernize — to be ready not just to fight, but to be ready to win,» Yatsenyuk said.

With an estimated 30,000 Russian troops now positioned near Ukraine’s eastern border, Yatsenyuk repeated his pledge to defend Ukrainian territory.

His government ceded Crimea without a shot to demonstrate to the world that Russia was the aggressor, he said — but if Moscow moves against another portion of Ukraine, the duty of all Ukrainians is «to protect our country,» he said. «We will fight.»

Moscow tightens grip

The United States and EU are seeking to exert pressure on Russia through a combination of sanctions and diplomatic isolation.

But Moscow has so far doggedly pursued its own course, even as Western leaders have denounced its actions as violations of Ukraine’s sovereignty and a breach of international law.

Amid heightened tensions within Ukraine, the Russian Foreign Ministry on Wednesday accused the Ukrainianborderservice of refusing to let air crew off Aeroflot jets for rest periods after landing in Ukraine. Aeroflot is the Russian national carrier.

This «breaks the international acts in compliance with flight safety requirements,» the ministry said in an online statement.

Meanwhile, Russia is tightening its grip on Crimea.

Crimea belonged to Russia until 1954 when it was given to Ukraine, which was then part of the SovietUnion. The region has a majority ethnic Russian population and other historic ties to Russia.

A large majority of its population voted in favor of joining Russia in a controversial referendum 10 days ago. Russian lawmakers in turn swiftly voted to absorb the Black Sea peninsula, where Russia has a major naval base, into the Russian Federation, and President Vladimir Putin signed the treaty into law.

In another step to cement the process, the vice-speaker of the Crimean parliament, Sergei Tsekov, was made a senator in Russia’s upper house Wednesday, Russia’s state-run ITAR-Tass news agencyreported.

At the same time, Kiev has ordered the withdrawal of Ukrainian armed forces from Crimea, citing Russian threats to the lives of military staff and their families effectively yielding the region to Moscow’s forces. They stormed one of Kiev’s last bases there Monday.

Aleksey Chaly, often referred to as Sevastopol’s new de facto mayor, announced Tuesday the dismissal of all «self-defense» teams, saying the «enemy» was now gone, as no forces loyal to Kiev remain in the city.

«I would like to draw the attention of some commanders of the self-defense units to the fact that the revolution is over,» he said in a video published on YouTube. «This week, federal agencies are being established, and we’re beginning to live by the laws of the Russian Federation.»

The G7 group of leading industrialized countries has condemned both the Crimean vote to secede and Russia’s annexation of Crimea. As a result, Russia has now been excluded from what was the G8.

Total: 859 words

Internationalisms Appendix I

|

word |

translation |

origin |

definition |

|

|

1 |

aggressor (1) |

агрессор, нападающая сторона |

from late Latin aggredi — атака |

a person or country that attacks another first |

|

2 |

agency (1) |

агентство |

from medieval Latin agentia — агентство |

a business or organization providing a particular service on behalf of another business, person, or group |

|

3 |

annexation (3) |

аннексия |

from Latin annexus – соединение |

the action of appropriating something, especially territory |

|

4 |

action (2) |

акция, действие |

from Latin actio(n-) — действие |

the fact or process of doing something, typically to achieve an aim |

|

5 |

centre (1) |

центр |

from Latin centrum, from Greek kentron, центр |

the point from which an activity or process is directed, or on which it is focused |

|

6 |

commander (1) |

командир |

from Old French comandeor, from late Latin commandare — командир |

a person in authority, especially over a body of troops or a military operation |

|

7 |

combination (1) |

комбинация |

from late Latin combinatio(n-) – объединение |

the process of combiningdifferent parts or qualities or the state of being combined |

|

8 |

confrontation (1) |

конфронтация |

from medieval Latin confrontare – сопоставлять, сравнивать |

a hostile or argumentative situation or meeting between opposing parties |

|

9 |

control (2) |

контроль |

from medieval Latin contrarotulare – копиясвитка |

the power to influence or direct people’s behaviour or the course of events |

|

10 |

crisis (3) |

кризис |

from ancient Greek κρίσις — решение, поворотный пункт |

any event that is expected to lead to an unstable and dangerous situation affecting an individual, group, community, or whole society |

|

11 |

de facto (2) |

фактический, реальный |

from Latin, literally ‘of fact’ |

in fact, whether by right or not |

|

12 |

demonstrate (1) |

демонстрировать |

from Latin demonstrat -шоу |

clearly show the existence or truth of (something) by giving proof or evidence |

|

13 |

diplomatic (1) |

дипломатический |

from Greek diplōma, —atis– официальное письмо, грамота |

of or concerning diplomacy |

|

14 |

effectively (1) |

эффективно |

from Latin ‘efficere ‘ accomplish |

In such a manner as to achieve a desired result |

|

15 |

federal (1) |

федеральный |

from Latin foedus — договор |

having or relating to a system of government in which several states form a unity but remain independent in internal affairs |

|

16 |

federation (2) |

федерация |

from late Latin foederatio(n-), from the verb foederare ‘to ally’, from foedus ‘league’. |

a group of states with a central government but independence in internal affairs |

|

17 |

focus (1) |

фокус |

from Latin focus – очаг, центр |

the centre of interest or activity |

|

18 |

formal (1) |

формальный |

from Latin formalis – формальный |

done in accordance with convention or etiquette |

|

19 |

General (1) |

генеральный |

from Latin generalis – всеобщий |

chief or principal |

|

20 |

global (1) |

глобальный |

from Latin globus — шар |

relating to the whole world; worldwide |

|

21 |

group (1) |

группа |

from French groupe, from Italian gruppo — группа |

a number of people or things that are located, gathered, or classed together |

|

22 |

industrialize (1) |

индустриализировать |

from French industriel — промышленные |

develop industries in (a country or region) on a wide scale |

|

23 |

installation (1) |

инсталляция |

from medieval Latin installare — устанавливать |

The action of installing someone or something, or the state of being installed |

|

24 |

integrity (1) |

интеграция — связанность |

from Latin integritas – сохранность, нетронутость |

the state of being whole and undivided |

|

25 |

international (5) |

интернациональный |

from French inter – между, national — национальный |

agreed on by all or many nations |

|

26 |

interview (1) |

интервью |

from French entrevue — встреча |

a meeting of people face to face, especially for consultation. |

|

27 |

isolation (1) |

изоляция |

mid 19th century: from isolate, partly on the pattern of French isolation — изоляция |

the process or fact of being apart from others |

|

28 |

leader (3) |

лидер |

from English lead – вести за собой |

the person who leads or commands a group, organization, or country |

|

29 |

legitimate (2) |

легитимный |

from Latin legitimus — законный |

conforming to the law or to rules |

|

30 |

local (1) |

локальный |

from late Latin localis — местный |

relating or restricted to a particular area or one’s neighbourhood. |

|

31 |

military (4) |

милитаристский, военный |

from French militaire or Latin militaris — военный |

relating to or characteristic of soldiers or armed forces |

|

32 |

ministry (2) |

министерство |

from Latin ministerium – служба, должность |

a government department headed by a minister |

|

33 |

modernize (1) |

модернизировать |

from late Latin modernus — современность |

adapt (something) to modern needs or habits, typically by installing modern equipment or adoptingmodern ideas or methods |

|

34 |

norm (1) |

норма |

from Latin norma — правило |

a standard or pattern, especially of social behavior |

|

35 |

online (1) |

available on or performed using the Internet or other computer network: |

||

|

36 |

parliament (1) |

парламент |

from Old French parlement ‘speaking’, from the verb parler |

the highest legislature |

|

37 |

period (1) |

период |

via Latin from Greek periodos — период |

a length or portion of time |

|

38 |

President (4) |

президент |

from Latin praesident – ‘sitting before’ – председательствующий |

the elected head of a republican state |

|

39 |

Prime Minister (1) |

премьер-министр |

from Latin primus- первый, minister –служитель, соратник |

the head of an elected government; the principal minister of a sovereign or state |

|

40 |

position (1) |

позиция, положение |

from Old French, from Latin positio -положение |

a place where someone or something is located or has been put |

|

41 |

process (1) |

процесс |

from Latin processus ‘progression, course’ — прогресс |

a series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end |

|

42 |

protest (1) |

протест |

from Latin protestari — утверждение |

a statement or action expressing disapproval of or objection to something |

|

43 |

referendum (1) |

референдум |

mid 19th century: from Latin, gerund ( ‘referring’) or neuter gerundive ( ‘something to be brought back or referred’) of referre |

a general vote by the electorate on a single political question which has been referred to them for a direct decision |

|

44 |

region (3) |

регион |

from Latin regio(n-) ‘ – регион |

an administrative district of a city or country |

|

45 |

republic (1) |

республика |

from Latin respublica, from res – суть+publicus – народ |

a state in which supreme power is held by the people and their elected representatives |

|

46 |

result (1) |

результат |

from medieval Latin resultare — отражаться |

a thing that is caused or produced by something else; a consequence or outcome |

|

47 |

revolution (1) |

революция |

from Old French, or from late Latin revolutio(n-) — революция |

a forcible overthrow of a government or social order, in favour of a new system |

|

48 |

sanctions (2) |

санкции |

from Latin sanctio(n-) — санкция |

measures taken by a state to coerce another to conform to an international agreement or norms of conduct, typically in the form of restrictions on trade or official sporting participation |

|

49 |

Secretary (1) |

Секретарь |

from late Latin secretarius – пользующийся доверием чиновник |

an official in charge of a US government department |

|

50 |

security (1) |

секьюрити |

from Latin secures – безопасный, надежный |

the safety of a state or organization. |

|

51 |

senator (1) |

сенатор |

from Latin senator |

a member of a senate |

|

52 |

Soviet (2) |

советский |

early 20th century: from Russian совет – орган государственной власти в СССР |

of or concerning the former Soviet Union |

|

53 |

sovereignty (1) |

суверенитет |

from Old French sovereinete – суверенитет |

the authority of a state to govern itself or another state |

|

54 |

summit (2) |

саммит |

From Latin summum, neuter of summus – высочайший, главный |

a meeting between heads of government |

|

55 |

technology (1) |

технология |

from Greek tekhnologia — технология |

the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry |

|

56 |

territory (2) |

территория |

from Latin territorium – территория, область |

of or relating to the ownership of an area of land or sea |

|

57 |

vice-speaker (1) |

вице-спикер |

from Old English sprecan |

The presiding officer in a legislative assembly, especially the House of Commons |

|

58 |

video (1) |

видео |

from Latin videre — видеть |

the recording, reproducing, or broadcasting of moving visual images |

The number of internationalisms found in the text – 58. Considering that some of them are repeated more often than once, the total number of international words in the text is – 86, i.e. 10 per cent.

Cognates Appendix II

|

word |

translation |

origin |

definition |

|

|

1 |

absorb (1) |

абсорбировать, впитывать, поглощать |

from Latin absorbere, from ab- ‘from’ + sorbere ‘suck in’ — впитывать |

take control of (a smaller or less powerful entity) and make it a part of a larger one |

|

2 |

act (1) |

акт, соглашение |

from Latin actus ‘event, thing done’ |

a thing done; a legal document codifying the result of deliberations of a committee or society or legislative body |

|

3 |

base (2) |

база |

from Latin basis ‘base, pedestal’ |

A place used as a centre of operations by the armed forces or others; a headquarters |

|

border service |

пограничная служба |

a branch of State Security Service tasked with patrol of the state border |

||

|

4 |

border (3) |

бордюр, граница |

from Old French bordeure — край |

a line separating two countries, administrative divisions, or other areas |

|

5 |

service (1) |

сервис |

from Latin servitium – рабство |

a public department or organization run by the state |

|

6 |

breach (1) |

брешь, нарушение закона |

from Old French breche -нарушать |

an act of breaking or failing to observe a law, agreement, or code of conduct |

|

7 |

cement (1) |

цементировать, скреплять |

from Latin caedere — высекать |

to settle or establish firmly |

|

centerstage |

основная позиция, положение |

(mainly journalism) a position in which someone or something is attracting a lot of attention |

||

|

8 |

stage (1) |

стадия, период, этап |

based on Latin stare – стоять. Current senses of the verb date from the early 17th century. |

a scene of action or forum of debate, especially in a particular political context |

|

9 |

community (1) |

коммуна, сообщество |

from Old French comunete — сообщество |

the people of a district or country considered collectively, especially in the context of social values and responsibilities; society |

|

10 |

сontroversial (1) |

контроверсивный, спорный, противоречивый |

from late Latin controversialis – относящийсякспору |

giving rise to public disagreement |

|

11 |

course (1) |

курс |

from Latin cursus- курс |

the way in which something progresses or develops |

|

12 |

ethnic (1) |

этничский |

from Greek ethnos ‘nation’ |

relating to a population subgroup with a common national or cultural tradition |

|

13 |

favor (2) |

фавор, протекция |

from Latin favor — доброжелательность |

approval, support, or liking for someone or something: |

|

14 |

historic (1) |

исторический |

via Latin from Greek historikos |

famous or important in history, or potentially so |

|

15 |

mayor (1) |

мэр |

from the Latin adjective major ‘greater’, used as a noun in late Latin. |

the head of a town |

|

16 |

portion (1) |

порция |

from Old French porcion, from Latin portio — часть |

a part of something divided between people |

|

17 |

publish (1) |

публиковать |

from Latin publicare ‘make public |

print (something) in a book or journal so as to make it generally known |

|

18 |

report (1) |

сообщать |

from Latin reportare ‘bring back’ |

give a spoken or written account of something |

|

19 |

respect (1) |

респект, уважение |

From Latin respectus – уважение |

avoid harming or interfering with |

|

20 |

respond (1) |

отвечать, респондент –отвечающий |

from Latin respondere – отвечать |

say something in reply |

The number of cognates found in the text – 20. Considering that some of them are repeated more often than once, the total number of cognates in the text is – 24, i.e. about 3 per cent.

The definitions of some Russian words were taken from the following dictionaries:

Словарь иностранных слов.- Комлев Н.Г.,2006.

РЕСПОНДЕНТ- соц. лицо, отвечающее на анкету социологического, демографического или психологического исследования.

САММИТ — полит. встреча, переговоры глав государств; встреча в верхах.

СЕКЬЮРИТИ — государственная безопасность; контрразведка (обычно об англосаксонских странах).

Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка.- Чудинов А.Н.,1910.

БОРДЮР (франц. bordure, от bord — край). Украшение по краям чего-либо.

Толковый словарь С.И. Ожегова

II. А́КЦИЯ, -и, жен. (книжн.). Действие, предпринимаемое для достижения какой-н. цели. Дипломатическая а. Военная а.

АННЕ́КСИЯ, -и, жен. (книжн.). Насильственное присоединение государства или части его к другому государству.

КОНФРОНТА́ЦИЯ, -и, жен. (книжн.). Противостояние, противоборство. Политическая к.

ЛЕГИТИ́МНЫЙ, -ая, -ое (спец.). Признаваемый законом, соответствующий закону.

ЛОКА́ЛЬНЫЙ, -ая, -ое; -лен, -льна (книжн.). Местный, не выходящий за определённые пределы. Локальная война.

СА́НКЦИЯ, -и, жен. 2. Мера, принимаемая против стороны, нарушившей соглашение, договор, а также вообще та или иная мера воздействия по отношению к правонарушителю (спец.). Уголовные, административные, дисциплинарные санкции.

ФАВО́Р, -а, муж. (устар.). Покровительство, протекция (употр. теперь в нек-рых выражениях). Барский ф. Быть в фаворе у кого-н. (пользоваться чьим-н. покровительством; разг.). Он сейчас не в фаворе (разг.).

Толковый словарь Д.Н.Ушакова

БРЕШЬ, бреши, жен. 2. перен. Ущерб, ничем не возмещенная утрата, недостача (книжн.). Брешь в бюджете.

ИЗОЛЯ́ЦИЯ, изоляции, мн. нет, жен. 2. Состояние по гл. изолироваться; разобщенность с другими, изолированное положение (книжн.). Обвиняемый приговорен к лишению свободы со строгой изоляцией.

РЕСПЕ́КТ и (ирон. шутл.) решпект, респекта, муж. ( (устар.). Уважение, почтение.

СУВЕРЕНИТЕ́Т, суверенитета, мн. нет, муж. (полит.). || Независимость государства в его внутренних делах, право собственного законодательства.

Энциклопедический словарь 2009г.

ИНСТАЛЛЯ́ЦИЯ -и; ж. 2. Установочные работы, монтаж сооружений, проводка осветительной сети, сборка системы кондиционирования воздуха и т. п.

ИНТЕГРА́ЦИЯ [тэ], -и; ж. 1) Понятие, означающее состояние связанности отдельных дифференцированных частей и функций системы, организма в целое, а также процесс, ведущий к такому состоянию.

Proper names Appendix III

|

word |

translation |

definition |

|

|

1 |

Aeroflot (2) |

Аэрофлот |

the largest airline in Russia |

|

2 |

Aleksey Chaly (2) |

Алексей Чалый |

|

|

3 |

Anders Fogh Rasmussen (3) |

Андерс Фог Расмуссен |

|

|

4 |

Arseniy Yatsenyuk (4) |

Арсений Яценюк |

|

|

5 |

Barack Obama (6) |

Барак Обама |

|

|

6 |

Belgium (2) |

Бельгия |

|

|

7 |

Brussels (3) |

Брюссель |

the capital and largest city of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union |

|

8 |

Crimea (11) |

Крым |

the peninsula on the northern coast of the Black Sea that is almost completely surrounded by water |

|

9 |

European Union, EU (8) |

ЕС, Европейский союз |

a politico-economic union of 28 member states that are located primarily in Europe |

|

10 |

G7 (1) |

Большая Семерка |

the Group of 7 (G7) is a group consisting of the finance ministers and central bank governors of seven major advanced economies |

|

11 |

G8 (1) |

Большая Восьмерка |

|

|

12 |

ITAR-TASS (1) |

ИТАР-ТАСС |

Russian News Agency |

|

13 |

Kiev (6) |

Киев |

the capital of Ukraine |

|

14 |

Moscow (6) |

Москва |

the capital of Russia |

|

15 |

NATO (2) |

НАТО |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

|

16 |

PBS (1) |

Служба общественного вещания |

Public Broadcasting Service |

|

17 |

Russia (29) |

Россия |

|

|

18 |

Sevastopol (1) |

Севастополь |

a federal city within the Crimean Federal District |

|

19 |

The Hague (2) |

Гаага |

one of the major cities hosting the United Nation |

|

20 |

the Netherlands (1) |

Нидерланды |

|

|

21 |

Sergei Tsekov (2) |

Сергей Чехов |

|

|

22 |

Viktor Yanukovych (4) |

Виктор Янукович |

|

|

23 |

Vladimir Putin (2) |

Владимир Путин |

|

|

24 |

Ukraine (13) |

Украина |

|

|

25 |

U.S. (3) |

США |

|

|

26 |

YouTube (2) |

a video-sharing website headquartered in San Bruno, California |

The number of proper names found in the text – 26. Considering that some of them are repeated more often than once, the total number of proper names in the text is – 117, i.e. about 13 per cent.

Lexical Analysis of the News Article

All in all, in the presented article there are 227 words (26 per cent), which can be understood by speakers of different European languages. Taking the definite articles the (57 in the news article) into consideration, the number of easily understood words amounts to 33 per cent. This fact highlights how languages and societies are becoming ever more interwoven because of globalization.

The Origin of Internationalisms

Analysis of the data in appendix I demonstrates that most international words originated from Latin (38 out of 58, that is 65 per cent). The other international words originated from Old French – 11 words out of 58, that is 19 per cent; from Ancient Greek – 5 words out of 58, that is – 9 per cent; from English – 3 words out of 58, that is 5 per cent; from Russian – 1 word out of 58, that is 2 per cent.

Top Ten International Words in the Lifestyle-Politics Category

|

English |

Russian |

French |

definition |

|

annexation |

аннексия |

annexion |

the action of appropriating something, especially territory |

|

confrontation |

конфронтация |

confrontation |

a hostile or argumentative situation or meeting between opposing parties |

|

integrity |

интеграция |

intégrité |

the state of being whole and undivided |

|

international |

интернациональный |

international |

agreed on by all or many nations |

|

isolation |

изоляция |

isolation f; isolement m |

the process or fact of being apart from others |

|

protest |

протест |

protêt |

a statement or action expressing disapproval of or objection to something |

|

referendum |

референдум |

referendum |

a general vote by the electorate on a single political question which has been referred to them for a direct decision |

|

sanction |

санкция |

sanction |

measures taken by a state to coerce another to conform to an international agreement or norms of conduct, typically in the form of restrictions on trade |

|

sovereignty |

суверенитет |

souveraineté |

the authority of a state to govern itself or another state |

|

Soviet |

советский |

soviétique |

of or concerning the former Soviet Union |

Conclusion

This research work reveals that the share of international words in the Lifestyle-Politics category is considerable and amounts to 10 per cent. Most of these words originated from Latin. But with the development of communication and contacts the number of Internationalisms taken from other languages is growing.

Languages are the essential medium in which the ability to communicate across culture develops. Knowledge of one or several languages enables us to perceive new horizons, to think globally, and to increase our understanding of ourselves and of our neighbors. Languages are, then, the very lifeline of globalization: without language (or communication), there would be no globalization; and vice versa, without globalization, there would be no world languages (e.g. English, Chinese, French, Spanish, and so on).

The global language system is very much interconnected. And the existence of international words proves it.

References

Schwegler Armin Language and Globalization. University of California, Irvine, 2006

Быков А.А. Анатомия терминов 400 словообразовательных элементов из латыни и греческого. Словообразование и заимствование. http://coollib.net/b/103116/read

Тарасова Л.А. Интернациональная лексика как частный случай заимствований. http://www.rusnauka.com/23_SND_2008/Philologia/26333.doc.htm

Словарь иностранных слов.- Комлев Н.Г.,2006

Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка.- Чудинов А.Н.,1910.

Толковый словарь С.И. Ожегова

Толковый словарь Д.Н. Ушакова

Энциклопедический словарь 2009г.

http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/

http://lingvo.mail.ru/

http://useful_english.enacademic.com

http://www.globalization101.org/uploads/File/Syllabus-Lang-Globalization.pdf

15

Просмотров работы: 1898

Need to write or read in a different language? Follow these tips

Updated on October 15, 2022

What to Know

- In Windows: Choose the desired Display and Help Languages in File > Options > Word Options > Language.

- Then, select Choose Editing Options in the same section to change the editing language.

- All but the proofing language in Office for Mac are the same as those for the operating system. To change it in Word: Tools > Language.

This article explains how to change display and/or editing languages in Word for Office 365, Word 2019, Word 2016, Word 2013, Word 2010, Word Online, and Word for Mac. In Windows—but not in macOS—you can choose them independently of the language installed for your operating system.

How to Change the Display Language

The display language in Word governs the ribbon, buttons, tabs, and other controls. To force a display language in Word that’s different from that of your operating system:

-

Select File > Options.

-

In the Word Options dialog box, select Language.

-

In the Choose Display Language section, choose the Display Language and Help Language you want to use. Languages installed in Windows 10 are listed.

-

If a specific language is not listed, select Get more display and help languages from Office.com. If necessary, install a Language Accessory Pack, then close and re-launch Word. You may need to reboot your computer, as well. After a language pack loads, go to the Word Options menu and choose that pack in the Display Language and Help Language lists.

-

Select Set as Default for both the Display Language and the Help Language lists.

-

Select OK to save your changes.

How to Change the Editing Language in Word

The editing language—which governs spelling, grammar, and word sorting—can be changed in the Word Options screen. Go to the Choose Editing Languages section, and select a language from the list. If the language isn’t listed, select the Add additional editing languages drop-down arrow and choose a language.

To proofread in the selected language, highlight the text, then go to the Review tab and select Language > Set proofing language. Choose a language from the list. Word will consider the highlighted selection to be the non-default, selected language and will check the spelling and grammar accordingly.

How to Change Language in Word Online

Language options for Office Online are similar to those in desktop versions of Office. In Office Online, highlight the text for proofing in the non-default language. Select Review > Spelling and Grammar > Set Proofing Language, then choose your alternative language. All proofing in that selected block will be governed by the rules of the alternative language.

How to Change Language in Word for Mac

The display and keyboard layout languages used in Office for Mac are the same as the ones for the operating system. You cannot use separate languages for the OS and Office applications. However, you can specify a different proofing language for Office for Mac.

To change the proofing language in Office for Mac, select Tools > Language in Word or another Office application. To change the proofing language for new documents, select Default.

If you select OK instead of Default, the proofing language you chose will only apply to the current file.

Normally, Word defaults to the language of the operating system. As a rule, you should use Windows to install language files rather than rely on an application like Word to do it for you.

FAQ

-

How do you delete a page in Word?

To delete a page in Word, select View, then go to the Show section and select Navigation Pane. In the left pane, select Pages, choose the page you want to delete and tap the delete or backspace key.

-

How do I check the word count in Word?

To check the word count in Microsoft Word, look at the status bar. If you don’t see the number of words, right-click the status bar and choose Word Count.

-

How do I insert a signature in Word?

To insert a signature in Microsoft Word, scan and insert a signature image into a new Word document and type your information beneath the signature. Then, select the signature block and go to Insert > Quick Parts > Save Selection to Quick Part Gallery. Name the signature > AutoText > OK.

Thanks for letting us know!

Get the Latest Tech News Delivered Every Day

Subscribe

Excel for Microsoft 365 Word for Microsoft 365 Outlook for Microsoft 365 PowerPoint for Microsoft 365 Access for Microsoft 365 OneNote for Microsoft 365 Project Online Desktop Client Publisher for Microsoft 365 Visio Plan 2 Excel 2021 Word 2021 Outlook 2021 PowerPoint 2021 Access 2021 Project Professional 2021 Project Standard 2021 Publisher 2021 Visio Professional 2021 Visio Standard 2021 OneNote 2021 Excel 2019 Word 2019 Outlook 2019 PowerPoint 2019 Access 2019 Project Professional 2019 Project Standard 2019 Publisher 2019 Visio Professional 2019 Visio Standard 2019 Excel 2016 Word 2016 Outlook 2016 PowerPoint 2016 Access 2016 OneNote 2016 Project Professional 2016 Project Standard 2016 Publisher 2016 Visio Professional 2016 Visio Standard 2016 Excel 2013 Word 2013 Outlook 2013 PowerPoint 2013 Access 2013 OneNote 2013 Project Professional 2013 Project Standard 2013 Publisher 2013 Visio Professional 2013 Visio 2013 Excel 2010 Word 2010 Outlook 2010 PowerPoint 2010 Access 2010 OneNote 2010 Project 2010 Project Standard 2010 Publisher 2010 Visio Premium 2010 Visio 2010 Visio Standard 2010 Excel Starter 2010 Language Preferences Language Preferences 2010 Language Preferences 2013 Language Preferences 2016 More…Less

You can use the Office language options to add a language, to choose the UI display language, and to set the authoring and proofing language.

The language options are in the Set the Office Language Preferences section of the Office Options dialog box, which you can access by going to File > Options > Language. The display and authoring languages can be set independently. For example, you could have everything match the language of your operating system, or you could use a combination of languages for your operating system, authoring, and Office UI display.

The available languages depend on the language version of Office and any additional language pack, language interface pack, or ScreenTip languages that are installed on your computer.

Add a language

You can add a display language or an authoring language. A display language determines the language Office uses in the UI — ribbon, buttons, dialog boxes, etc. An authoring language influences text direction and layout for vertical, right-to-left, and mixed text. Authoring languages also include proofing tools such as dictionaries for spelling and grammar checking. (The preferred authoring language appears at the top of the list in bold. You can change this by choosing the language you want and selecting Set as Preferred.)

To add a display language:

-

Open an Office program, such as Word.

-

Select File > Options > Language.

-

Under Office display language, on the Set the Office Language Preferences, select Install additional display languages from Office.com.

-

Choose the desired language in the Add an authoring language dialog and then select Add. A browser page opens where you can download the installation file.

-

On the browser page, select Download and run the downloaded pack to complete installation.

-

The added language appears in the list of Office display languages.

To add an authoring language:

-

Open an Office program, such as Word.

-

Select File >Options >Language.

-

On the Set the Office Language Preferences, under Office authoring languages and proofing, select Add a Language….

-

Choose the desired language in the Add an authoring language dialog and then select Add. A browser page opens where you can download the installation file.

-

On the browser page, select Download and run the downloaded pack to complete installation.

-

The added language appears in the list of Office authoring languages.

If Proofing available appears next to the language name, you can obtain a language pack with proofing tools for your language. If Proofing not available is next to the language name, then proofing tools are not available for that language. If Proofing installed appears next to the language name, you’re all set.

-

To go online and get the language pack you need, select the Proofing available link.

Both kinds of Office languages (display and authoring) have a preferred language that you can set independently.

The preferred language appears in bold at the top of each language list. The order of the languages in the list is the order in which languages are used by Office. For example, if your display language order is Spanish <preferred>, German, and Japanese, and the Spanish language resources are removed from your computer, German becomes your preferred display language.

To set the preferred language:

-

Open an Office program, such as Word.

-

Select File > Options > Language.

-

Under Set the Office Language Preferences, do one or both of the following:

-

Under Office display language, choose the language you want from the list and then select Set as Preferred.

-

Under Office authoring languages and proofing, choose the language you want from the list and then select Set as Preferred.

-

You can use the Office language options to add a language or to choose the language in which the Help and ScreenTips display.

The language options are in the Set the Office Language Preferences dialog box, which you can access by going to File > Options > Language. The display and help languages can be set independently. For example, you could have everything match the language of your operating system, or you could use a combination of languages for your operating system, editing, display, and Help.

The available languages depend on the language version of Office and any additional language pack, language interface pack, or ScreenTip languages that are installed on your computer.

Add a language

You can add a language to Office programs by adding an editing language. An editing language consists of the type direction and proofing tools for that language. The proofing tools include language-specific features, such as dictionaries for spelling and grammar checking. (The default editing language appears at the top of the list in bold. You can change this by choosing the language you want and selecting Set as Default.)

-

Open an Office program, such as Word.

-

Select File > Options > Language.

-

In the Set the Office Language Preferences dialog box, under Choose Editing Languages, choose the editing language that you want to add from the Add additional editing languages list, and then select Add.

The added language appears in the list of editing languages.

If Not enabled appears in the Keyboard Layout column, do the following:

-

Select the Not enabled link.

-

Windows settings will open to the Language page. In the Add Languages dialog box of Windows settings, select Add a language, choose your language in the list, and then select Add.

-

Close the Add Languages dialog box in Windows settings. In the Office dialog box, your language should display as Enabled under Keyboard Layout in the Choose Editing Languages section.

If Not Installed appears in the Proofing column, you might need to obtain a language pack or language interface pack to obtain the proofing tools for your language.

-

To go online and get the language pack you need, select the Not installed link.

The display and Help languages are the languages used in Office for display elements, such as menu items, commands, and tabs, in addition to the Help file display language.

The default language appears in bold at the top of the list. The order of the languages in the display and Help lists is the order in which languages are used by Office. For example, if your display language order is Spanish <default>, German, and Japanese, and the Spanish language tools are removed from your computer, German becomes your default display language.

To set the default language:

-

Open an Office program, such as Word.

-

Click File > Options > Language.

-

In the Set the Office Language Preferences dialog box, under Choose Display and Help Languages, choose the language that you want to use, and then select Set as Default.

Which display language is being used for which Office program?

If you use multiple languages and have customized Office so that it fits the way that you want to work, you can review all of the Office programs to see which language is the default display language for each.

-

In the Set the Office Language Preferences dialog box, under Choose Display and Help languages, select View display languages installed for each Microsoft Office program.

Note: This feature is available only for the following Office programs: Excel, OneNote, Outlook, PowerPoint, Publisher, Visio, and Word. It is not available for Office 2016 programs.

ScreenTips are small pop-up windows that provide brief, context-sensitive help when you rest the pointer on a display element, such as a button, tab, dialog box control, or menu. Setting the ScreenTip language in one Office program sets it for all of the Office programs that you have installed.

-

Open an Office program, such as Word.

-

Select File > Options > Language.

-

In the Set the Office Language Preferences dialog box, under Choose ScreenTip Language, choose your ScreenTip language.

Notes:

-

This feature is not available in Office 2016.

-

If the language that you want is not listed, you might need to add more language services. Select How do I get more ScreenTip languages from Office.com, and then follow the download and installation instructions.

-

After you install a new ScreenTip language, it becomes your default ScreenTip language.

-

For more information about ScreenTips, see Show or hide ScreenTips.

See also

Enable or change the keyboard layout language

Check spelling and grammar in a different language

Turn on automatic language detection

Need more help?

Microsoft Word is used in different countries and many languages. For some documents such as international Agreements, you need to write the documents or just parts of the document in a different language.

To change the text language, select the text for which you want to change language and do one of the following:

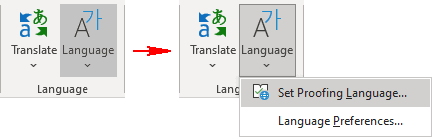

- On the Review tab, in the Language group, click the Language button, then choose Set Proofing Language…:

- On the status bar, click the Language icon:

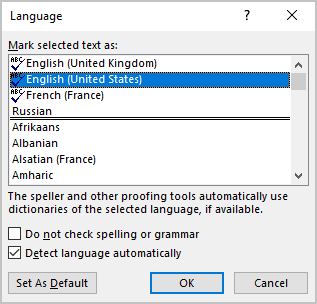

In the Language dialog box, choose the language you want to use for the selected text and click OK:

Notes:

- You can set different languages to different words, sentences, paragraphs, pages, or sections in the document.

- You can

skip some words or sentences from spelling and grammar checking or add them to the custom dictionary for some language.

Please, disable AdBlock and reload the page to continue

Today, 30% of our visitors use Ad-Block to block ads.We understand your pain with ads, but without ads, we won’t be able to provide you with free content soon. If you need our content for work or study, please support our efforts and disable AdBlock for our site. As you will see, we have a lot of helpful information to share.

As you learn a new language, it’s natural to look for words or other patterns that feel familiar or have similarities to your first language! Sometimes they are harder to find, depending on the language you’re learning, and for others the similarities will be unavoidable. Underneath the surface, there are lots of features shared by all human languages—and since all of Duolingo’s 106 courses in 41 languages are totally free, it’s easy to compare and contrast languages from around the world!

Let’s look at 10 things that all languages have in common.

1. All languages have dialects and accents

As long as people are using the language, variation is inevitable. There may be differences even within a small, homogenous community based on gender and age, and once there are a few communities using the language, you’ll have geographical dialects, too. And there can be loads of other kinds of dialects and accents, based on ethnicity, religion, bilingualism or language background, and more. This is true for both spoken and signed languages as well—language always varies!

2. All languages change over time

If people continue using a language, it will change. Actually, even languages no longer used by a community can change; Latin continues to change over time for new purposes, including brand-new combinations of Latin words for science and medical terms! Languages change over time because people, culture, and communication needs are always evolving. But other properties of language lead to change, too: to communicate successfully, there’s a push-and-pull between being really clear (more information, more precision in meaning, pronunciation, etc) and being really efficient (getting the message across quickly, taking no more time and effort than absolutely necessary). The result is always language change!

3. All languages have grammar

No matter the language—whether it’s signed or spoken, whether it has a writing system or a dictionary or an official organization—all languages have rules about how to put words together. This is true of old languages, newer ones, pidgins and creoles, and languages from every continent. Some may have stricter rules about certain kinds of word combinations, and others will have a lot of flexibility, but you can’t escape grammar!

4. All languages are learned by babies at roughly the same rate

No matter which language or languages we’re exposed to, babies take the same amount of time to master their language. Kids from all language backgrounds (including multilingual babies, too!) start babbling, producing first words, and making simple sentences at around the same time, but it actually takes more years than you might realize to figure out all the pieces of the language! For example, for English-learning kids, it’s not uncommon to be still working on some of the harder sounds, like «r,» even after they’ve started school. And some trickier grammar concepts, like the English passive (the lion was chased by the mouse), also aren’t totally mastered until well into elementary school. But learning happens on basically the same timeline, for many (many) years.

5. All languages are equally complex

There are no simple or primitive languages, or inherently sophisticated languages, so all languages are equally complex. Languages will vary in lots of ways—the number of sounds or handshapes they have, the number of verb endings and noun categories —and typically languages will have more of some and less of others. Even if a language seems «simple» in one respect, it likely has other features that will seem less so! Evaluating an entire language as simple or complex ignores variation across these different properties, at best—and at worst it could actually be a non-linguistic commentary on the people who use the language.

For example, Chinese has a huge number of written characters, even just for basic literacy, but Chinese verbs have zero conjugations. Meanwhile, Spanish has a maddening number of verb conjugations, some only used in certain countries (!), but its writing system is really transparent and predictable – once you know the rules for writing Spanish, you’ll know exactly how to pronounce any written word, no matter how obscure. Similarly, Chinese tones are a real challenge for learners whose language doesn’t have tones, but tonal languages are common throughout East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, Mexico, and Central America—and if your own language has tones, Chinese won’t seem so intimidating!

6. All languages have ways of talking about the past, present, and future

The way languages express time can vary widely, but they all have a way to communicate when something happened, is happening, or will happen. Languages might use stand-alone words to communicate time, or they might instead use endings (or prefixes!) that are added onto other words like verbs. In English, we have time words like «tomorrow» and «already» and we also have a few verb endings for time too, like the -ed we add to many verbs to show that something already happened (we talked to them about it already), and languages vary greatly in how they use grammar to express time. Even cultures that have very different concepts of time and telling time still have ways of communicating about past, present, and future!

7. All languages have ways of being polite and rude

Languages will have a mix of pronunciations, vocabulary, grammar, and conversation rules to communicate ideas more politely or more rudely. In some languages, pronouns for people might make a big difference; in others, it could be using the appropriate verb endings. In English, we often demonstrate politeness by adding a lot of extra words and euphemisms (Would you be so kind as to give me a hand with this, if it’s not too much trouble?), but there’s no reason a language couldn’t instead say Help with a formal ending!

8. All languages can communicate all ideas and feelings

You might have heard that some words are «untranslatable» or can’t be expressed in another language, but all languages have the ability to communicate any idea, whether it’s about science, technology, folklore, history, mythology, or even schadenfreude (the German word for taking pleasure from someone else’s misfortune—see! I just expressed it in English! 😛). A language might need a different number of words or different kinds of grammatical structures to translate the idea, but the languages we know don’t limit what we can think, feel, or understand. Whether our language expresses an idea in one word or six, the number itself is arbitrary—after all, most people can’t agree on how to define what counts as one «word,» in part because languages have such different rules about how words are formed and written! Some languages, like German, smush shorter words together to form really long ones, while other languages use more spaces, hyphens, and expressions, but all languages have the tools to express any idea.

9. All languages have slang

Because we use language to connect with each other and show our identities, languages all have slang and informal words. Slang in English used to include «radical» and «sick» to mean «cool,» but today you’ll hear «slaps» and «dope» instead. (That’s right—»dope» has made a comeback!) Slang and informal language can include pronunciations, vocabulary, expressions, and even grammar, and it can be used to show closeness, informality, or belonging to a particular group. The opposite is true, too: Languages all have ways of showing more formality and distance, to indicate belonging to other groups. What counts as formal and informal can change over time and vary widely across communities. Long ago, Vulgar Latin was sort of the slang of its day—the informal way people actually spoke to each other, not the Latin well represented in political and literary writing. It’s all the different, natural ways of actually speaking Latin that gave rise to today’s Romance languages!

10. All languages have value

There are lots of reasons to study, research, learn, or care about a language, and all those languages have value. Language is part of the culture, history, and tradition of a community, and that alone gives a language value—whether or not it’s used widely, leads to economic or academic gains, or is useful for travel. Every language tells us something about the amazing diversity of human communication, how we represent and convey really complex ideas, and the impressive grammatical nuances our brains are made to handle. Even constructed languages give us insights into the aspirations and ideals of language learners and the ways we’d like to connect with each other. It’s no wonder Duolingo has millions of learners all over the world!

Thanks to the language experts who contributed to this post: Dr. Isabel Deibel, Emma Gibson, Dr. James Leow, Dr. Emily Moline, Dr. Elizabeth Strong, and Dr. Hope Wilson!

When you’re creating a document that’s aimed at an international audience, using text in multiple languages, there are extra considerations to keep in mind.

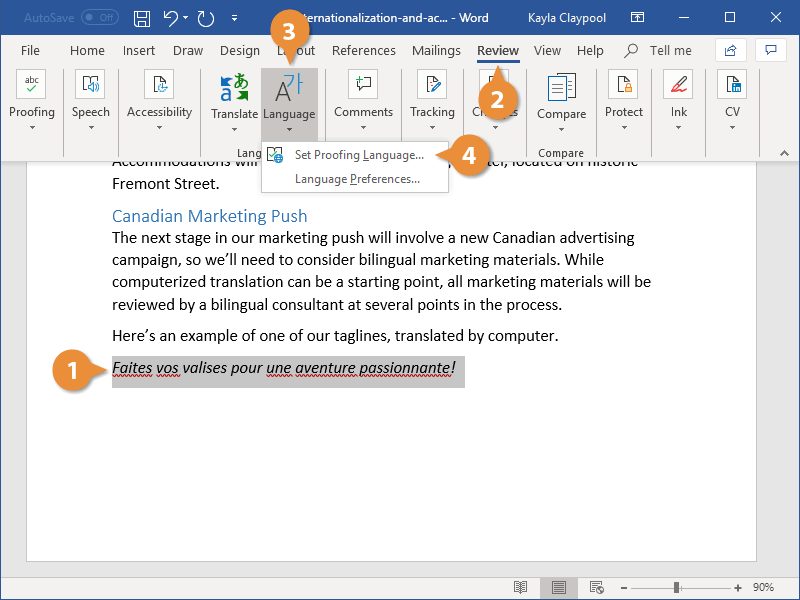

Change the Proofing Language

You can change the proofing language for all or part of a document, which sets the language for spelling and grammar check.

- Select the relevant text.

- Click the Review tab on the ribbon

- Click the Language button.

- Select Set Proofing Language.

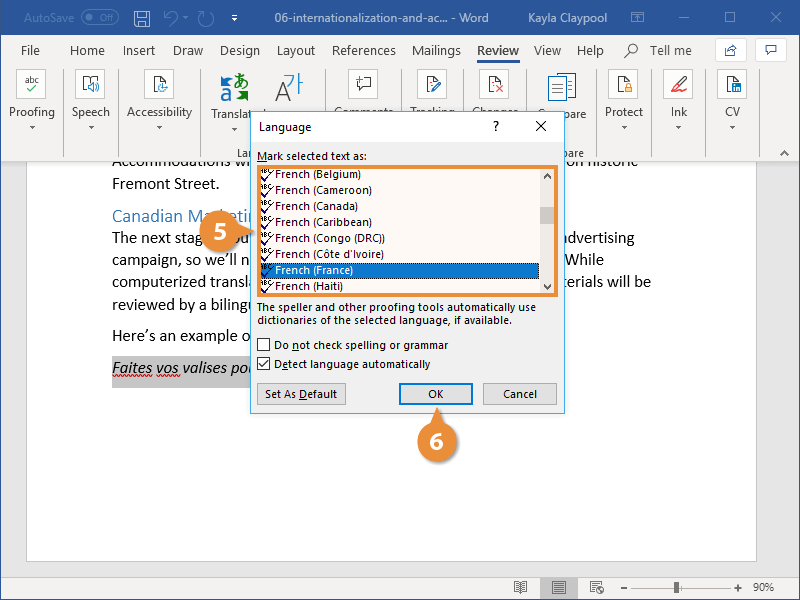

The top of the Languages window shows the languages currently in use, while the rest of the languages Word supports will be listed below it.

- Select a language from the list.

- Click OK.

The editing language for the selected paragraph is changed. Spelling and grammar check now understands the additional language. You can even view synonyms for a word in the new language.

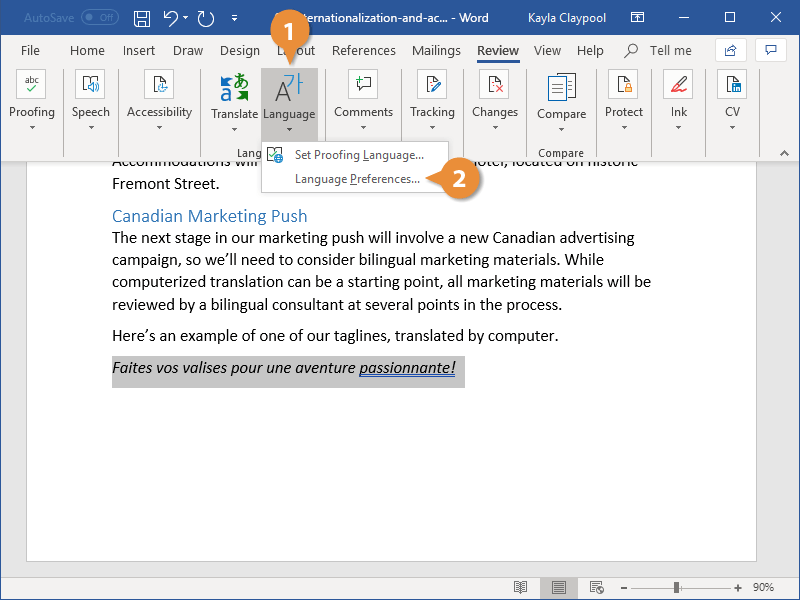

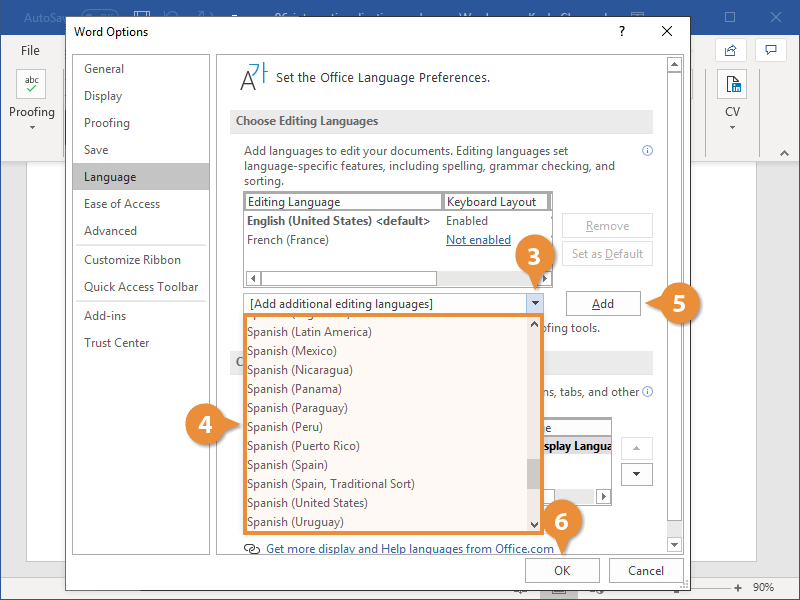

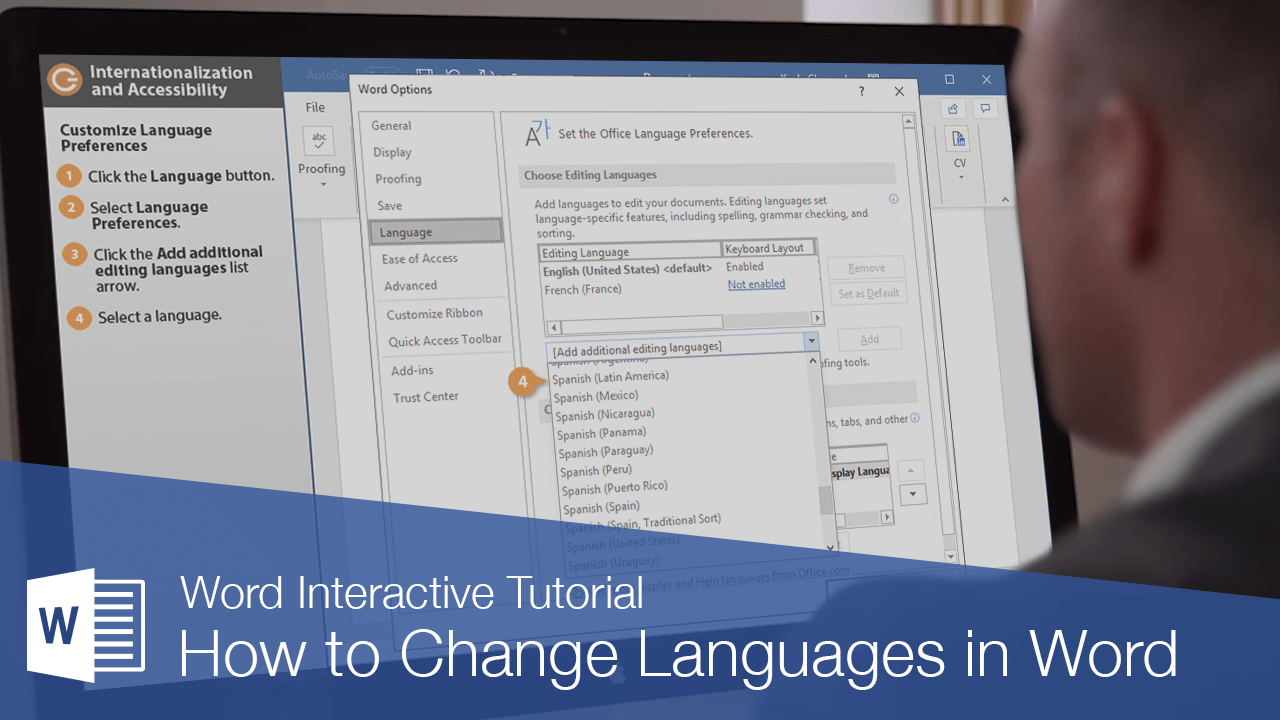

Customize Language Preferences

If you’re working with multiple languages, you can manage the list of editing languages in use in the Word Options screen.

- Click the Language button on the Review tab.

- Select Language Preferences.

Here, you can see all the editing languages currently in use and add new ones quickly.

- Click the Add additional editing languages list arrow.

- Select a language.

- Click Add.

The new language is added to the list. You can also remove languages from the editing list

Additionally, you can change the default editing language, the display language used for ribbon tabs and buttons, and the default language for help files from here.

- Click OK.

The language preferences are updated.

Best Practices for International Documents

When working on documents meant for an international, multilingual audience, there are a few best practices to keep in mind.

- Keep syntax simple. Word includes built-in translation tools that, while not perfect, work pretty well when translating something simple.

- Don’t use ambiguous date and time formats. Make sure that you don’t use date and time formats that mean different things in different regions. For example, 6/12 can mean either June 12th, or December 6th. Instead, write out the month and date to remove ambiguity.

- Use default Body and Header fonts. This way, someone viewing your document can switch font sets easily if necessary to make it easier to read.

- Globalize examples and avoid specific cultural references and colloquialism. Avoid using specific colloquialisms where, if the words translate perfectly, the meaning may not. For example, the phrase «for the birds» is simple enough to translate word-for-word, but the meaning may get changed or lost depending on the culture of the reader.?

FREE Quick Reference

Click to Download

Free to distribute with our compliments; we hope you will consider our paid training.

Yes, obviously. Just select the text and press the language button in the status bar

If your document has been written in multiple languages then things are trickier.

- If different keyboard layouts were used for typing them, but the layout doesn’t match the language name then you may use VBA to fix that.

- If you’ve typed them with the same layout (like English and French with the French layout) then sometimes Word is able to guess the language. It does have a language detection feature as you can see in the Language dialog above, but it can only detect languages in the list you specify. Notice the part highlighted by me:

Detect language automatically

In 2010, 2013, and 2016 versions of Word and Outlook

- Open a new document or email message.

- On the Review tab, in the Language group, click Language.

- Click Set Proofing Language.

- In the Language dialog box, select the Detect language automatically check box.

- Review the languages shown above the double line in the Mark selected text as list. Office can detect only those languages listed above the double line. If the languages that you use are not shown above the double line, you must enable the editing language (turn on the language-specific options) so that Office can automatically detect them.

Turn on automatic language detection

However the «Detect language automatically» feature often fails to work when you switch language during typing, or when you paste text in another language. So unfortunately you’ll still have to use some VBA to change the language. You can call some external service or use the built-in language detection feature, but with finer tuning to make the result more desireable

See also

- Specifying a Language for Text

- Check spelling and grammar in a different language

- Change spelling check language for a Document in Microsoft Word 2010