Puzzles are a relatively recent addition to daily newspapers. The first crossword puzzle appeared in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World only 106 years ago. Here’s a look at how your favorite pastime developed over the years.

The origin of many of today’s newspaper puzzles was a game that was played in China as early as 190 years B.C. Various versions used numbers and symbols and require users to arrange them in a certain order. They called it «Magic Squares.«

In the version played in ancient Pompeii, a player was given a group of words — in Latin, of course — and had to arrange them on a grid so that the words would read the same way across and down.

Among early Americans who were fascinated by Magic Squares: Benjamin Franklin, who created one that was first published in 1767.

1783

Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler devises a game he calls «Latin Squares.» He describes it as a «new kind of Magic Squares.» It’s a grid in which each numeral or symbol can appear only once in each direction. This will evolve into today’s Sudoku.

DEC. 21, 1913

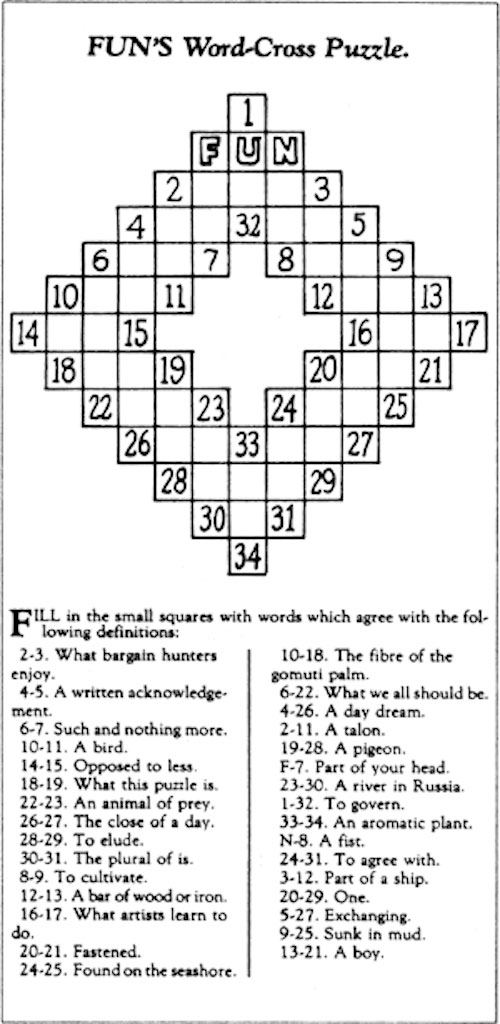

The first crossword puzzle — created by Arthur Wynne and called «Word-Cross» — appears in the New York World.

Wynne, a violinist for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, moved to New York to work for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World — at the time, the world’s most visually-oriented newspaper, with pictures, illustrations, infographics and cartoons.

Wynne is asked to come up with a new type of puzzle. He draws inspiration from Magic Squares, turning the game on its ear: He discards the anagram-like aspect and places the words on the page himself — but then hides the words, giving readers clues on how the missing letters are to be filled in.

APRIL 1924

Dick Simon and Lincoln Schuster publish «The Cross Word Puzzle Book» — a collection of puzzles that had run in the New York World and the first-ever book-length collection of crossword puzzles.

By the end of that year, they will have sold more than a million copies — so many that it sets Simon and Schuster on the road to becoming a publishing giant.

NOV. 17, 1924

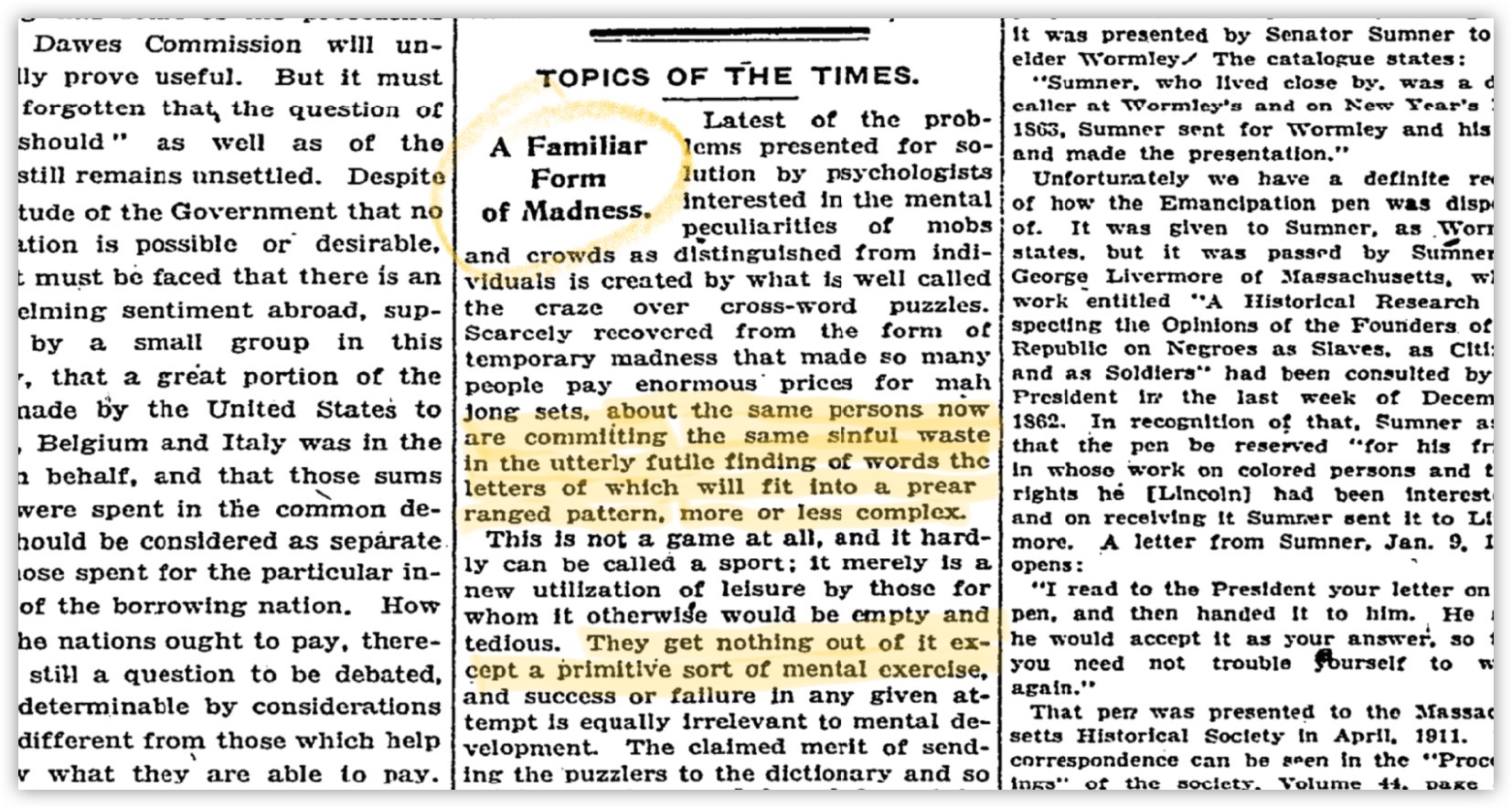

The New York Times notes the crossword craze overtaking the city and calls them a «primitive sort of mental exercise» and «a sinful waste» of time. «This is not a game at all,» the Times writes, «and it can hardly be called a sport; it merely is a new utilization of leisure by those for whom it would otherwise be empty and tedious.»

FEB. 3, 1925

The New York Evening World runs a story that tells readers «Cross-word puzzles have captivated and possessed New York completely.» It reports that crosswords are a great «brain exercise» and urges readers to give them a try.

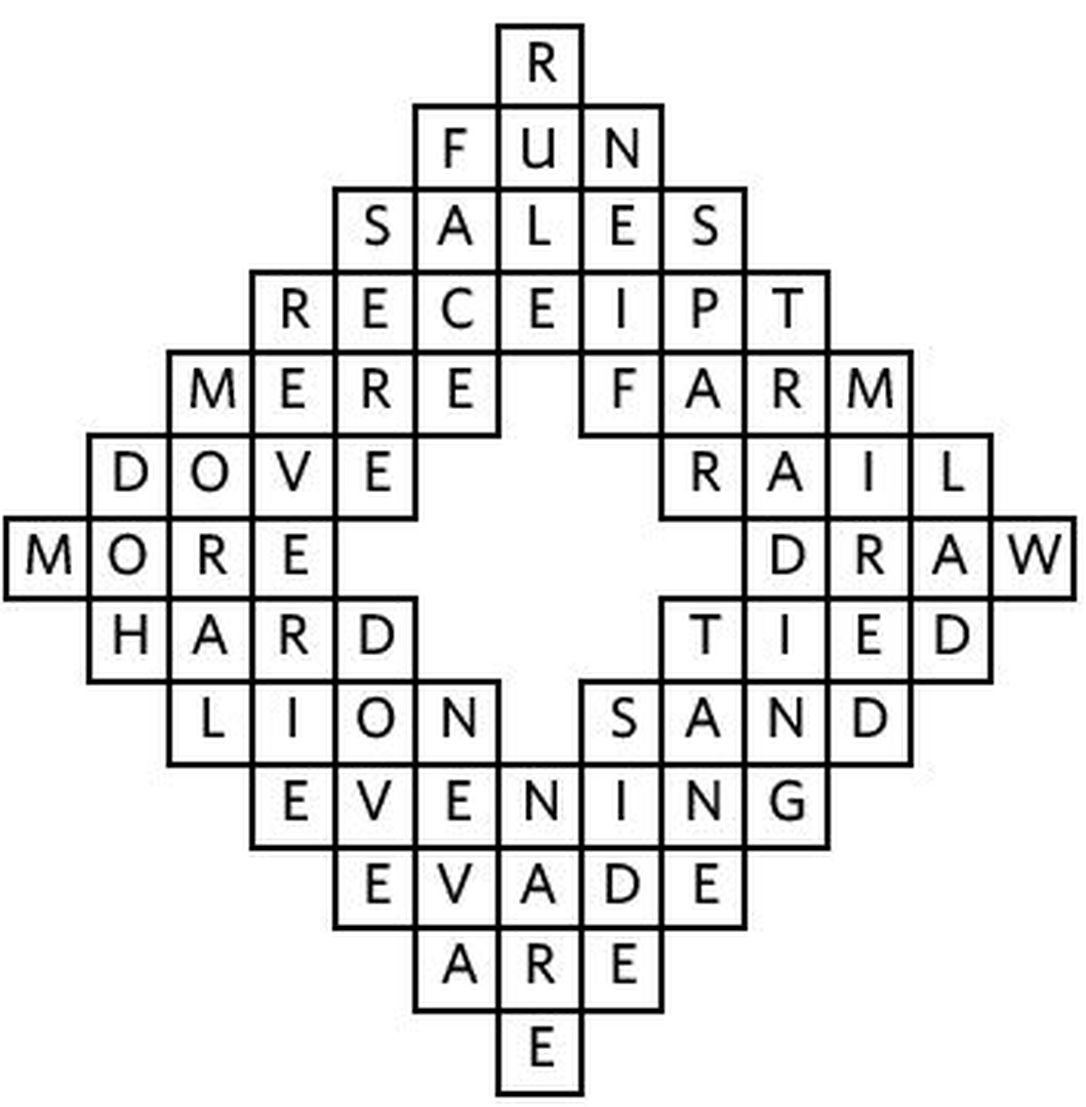

The World’s First Crossword Puzzle

Dec. 21, 1913 — New York World

1931

Dell Crossword Puzzles magazine begins publishing crosswords and other puzzles.

FEB. 15, 1942

The New York Times publishes its first crossword puzzle.

NOV. 11, 1950

The New York Times begins publishing a daily crossword puzzle.

1954

Comic book artist Martin Nadel — best known for creating the «golden age» version of the Green Lantern in 1940 — creates the first illustrated «Scramble» puzzle — a series of scrambled words that, when arranged properly, matches a cartoon-illustrated clue.

Nadel would eventually change the feature’s name to «Jumble» and, in 1962, hand off to Henri Arnold and Bob Lee, who would write and draw the puzzle for the next 30 years.

Nadel would go to work for the Leo Burnett advertising agency, where he would play a key role in creating the Pillsbury Doughboy.

March 1, 1968

Norman E. Gibat creates and publishes the first Word Search puzzle in his weekly advertising digest, Selenby (say it out loud: «Sell ’n’ buy»), in Norman, Oklahoma. That first puzzle contained only 34 words — of locations in Oklahoma.

His switchboard lights up as teachers call, wanting extra copies to use in their classes.

1979

Dell begins running new puzzles it calls «Number Place.» It will take them a few years — and a change of name — before they catch on.

1984

Japanese publisher Nikoli takes the Number Place puzzles, makes a few small changes and renames them «Sudoku» — short for the expression «Sūji wa dokushin ni kagiru»: «The digits are limited to one occurrence.»

Sudoku becomes a big hit in Japan, where the alphabet isn’t really suited for crossword puzzles.

March 1997

New Zealand-born retired judge Wayne Gould visits Tokyo, finds a book of Sudoku puzzles and sees potential in the concept. Over the next six years, he develops a computer program he calls Pappocom Sudoku that automatically generates Sudoku puzzles.

Nov. 12, 2004

Gould’s Sudoku puzzle first appear in the Sunday Times of London.

July 2006

Gould publishes his first Sudoku puzzle in the U.S. — in the Daily Sun of Conway, New Hampshire.

Gould’s idea for marketing Sudoku in the U.S.: Give the puzzle away for free to newspapers in exchange for plugging his computer applications and books.

By the end of the year, Gould will have sold more than 4 million Sudoku books.

THE CREATORS OF YOUR FAVORITE PUZZLES

These puzzles The Spokesman-Review brings you don’t grow on trees, you know. They’re created by some of the most clever… well, we hesititate to call them «evil geniuses,» but that’s pretty much what we’re talking about, right?

Tricky Ricky Kane

Wordy Gurdy

«Tricky Ricky Kane» is a pen name for longtime puzzle creator Mark Danna, assistant to the puzzle editor for the Wall Street Journal. He’s published more than 20 word search books and more than 200 crossword puzzles, including two for The Sunday New York Times and he’s the co-writer of Mensa’s Page-A-Day Puzzle Calendar. He also worked as a staff writer for Who Wants to be a Millionaire. Previously, Danna was a professional Frisbee player and won three national Frisbee championships and a national disc golf championship.

David L. Hoyt

Jumble

Word Roundup

Hoyt gave up a career in finance in 1993 to become a full-time puzzle maker. In addition to his most popular feature, Word Roundup, he also creates Jumble Crosswords, TV Jumble, Pat Sajak’s Lucky Letters and USA Today’s Up & Down Words. Hoyt, who lives in Chicago, has created game apps for phones and casino slot machines and scratch-off lottery games. He’s also sold board games to Hasbro and Mattel.

Jeff Knurek

Jumble

Word Roundup

Cartoonist Jeff Knurek is best-known, perhaps, for illustrating the daily Jumble feature — which you can usually find at the bottom right of page two of your daily Spokesman-Review section. Tribune syndicate says the duo reaches more than 70 million readers every day. Knurek lives in Fishers, Indiana, and created the game Spikeball.

Jacqueline E. Mathews

The Daily Commuter

Mathews spent 30 years working for Dell Magazines’ puzzle publications. She founded her own puzzle syndication agency in 1989 and has written four books of word puzzles. The idea behind «The Daily Commuter» puzzle: Clues are more «straightforward» to make this easier for commuters on a bus or train. Mathews also tries to use a bit more humor in her clues. She lives in Everett, Washington.

Will Shortz

The New York Times

Shortz sold his first crossword puzzle at age 14. Two years later, he became a regular contributor to Dell puzzle publications. Shortz attended law school at the University of Virginia but upon graduation, decided to become a full-time puzzle creator instead. He became the crossword editor for The New York Times in 1993. He wrote riddles for the film «Batman Forever» in 1995 and guest-starred in a 2008 episode of «The Simpsons«. He owns and operates the largest table tennis facility in the U.S. near his home in Pleasantville, New York.

Christopher York

7 Little Words

York created his first word game at age 15 with an Atari home computer. He later created 7 Little Words as an electronic game for mobile devices. Apple’s App Store featured the app, which has now been downloaded more than 5 million times. In 2011, 7 Little Words was adapted for use in newspapers. York lives in Caribou, Maine.

Solution for the 1913 Word-Cross Puzzle

Sources:

The New York Times, The Guardian, Bangor Daily News, Time magazine, Andrews McMeel Syndication, Tribune Content Agency, Harper Collins Publishers, WillShortz.com, Sudoku.com, Jumble.com, crosswordtournament.com, RecMath.org, TownePost.com, SporcleBlog, simpsonswiki.com

The New York Times crossword puzzle is a daily American-style crossword puzzle published in The New York Times, online on the newspaper’s website, syndicated to more than 300 other newspapers and journals, and on mobile apps.[1][2][3][4][5]

The puzzle is created by various freelance constructors and has been edited by Will Shortz since 1993. The crosswords are designed to increase in difficulty throughout the week, with the easiest puzzle on Monday and the most difficult on Saturday.[6] The larger Sunday crossword, which appears in The New York Times Magazine, is an icon in American culture; it is typically intended to be as difficult as a Thursday puzzle.[6] The standard daily crossword is 15 by 15 squares, while the Sunday crossword measures 21 by 21 squares.[7][8]

History[edit]

Although crosswords became popular in the early 1920s, The New York Times (which initially regarded crosswords as frivolous, calling them «a primitive form of mental exercise») did not begin to run a crossword until 1942, in its Sunday edition.[9][10] The first puzzle ran on Sunday, February 15, 1942. The motivating impulse for the Times to finally run the puzzle (which took over 20 years even though its publisher, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, was a longtime crossword fan) appears to have been the bombing of Pearl Harbor; in a memo dated December 18, 1941, an editor conceded that the puzzle deserved space in the paper, considering what was happening elsewhere in the world and that readers might need something to occupy themselves during blackouts.[10] The puzzle proved popular, and Sulzberger himself authored a Times puzzle before the year was out.[10]

In 1950, the crossword became a daily feature. That first daily puzzle was published without an author line, and as of 2001 the identity of the author of the first weekday Times crossword remained unknown.[11]

There have been four editors of the puzzle: Margaret Farrar from the puzzle’s inception until 1969; Will Weng, former head of the Times‘ metropolitan copy desk, until 1977; Eugene T. Maleska until his death in 1993; and the current editor, Will Shortz. In addition to editing the Times crosswords, Shortz founded and runs the annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament as well as the World Puzzle Championship (where he remains captain of the US team), has published numerous books of crosswords, sudoku, and other puzzles, authors occasional variety puzzles (also known as «Second Sunday puzzles») to appear alongside the Sunday Times puzzle, and serves as «Puzzlemaster» on the NPR show «Weekend Edition Sunday».[12][13]

The puzzle’s popularity grew over the years, until it came to be considered the most prestigious of the widely circulated U.S. crosswords. Many celebrities and public figures have publicly proclaimed their liking for the puzzle, including opera singer Beverly Sills,[10] author Norman Mailer,[14] baseball pitcher Mike Mussina,[15] former President Bill Clinton,[16] conductor Leonard Bernstein,[10] TV host Jon Stewart,[15] and music duo the Indigo Girls.[15]

The Times puzzles have been collected in hundreds of books by various publishers, most notably Random House and St. Martin’s Press, the current publisher of the series.[17] In addition to appearing in the printed newspaper, the puzzles also appear online on the paper’s website, where they require a separate subscription to access.[18] In 2007, Majesco Entertainment released The New York Times Crosswords game, a video game adaptation for the Nintendo DS handheld. The game includes over 1,000 Times crosswords from all days of the week. Various other forms of merchandise featuring the puzzle have been created, including dedicated electronic crossword handhelds that just contain Times crosswords, and a variety of Times crossword-themed memorabilia, including cookie jars, baseballs, cufflinks, plates, coasters, and mousepads.[17]

Style and conventions[edit]

Will Shortz does not write the Times crossword himself; a wide variety of contributors submit puzzles to him. A full specification sheet listing the paper’s requirements for crossword puzzle submission can be found online or by writing to the paper.

The Monday–Thursday puzzles and the Sunday puzzle always have a theme, some sort of connection between at least three long (usually Across) answers, such as a similar type of pun, letter substitution, or alteration in each entry. Another theme type is that of a quotation broken up into symmetrical portions and spread throughout the grid. For example, the February 11, 2004, puzzle by Ethan Friedman featured a theme quotation: ANY IDIOT CAN FACE / A CRISIS IT’S THIS / DAY-TO-DAY LIVING / THAT WEARS YOU OUT.[19] (This quotation has been attributed to Anton Chekhov, but that attribution is disputed and the specific source has not been identified.) Notable dates such as holidays or anniversaries of famous events are often commemorated with an appropriately themed puzzle, although only two are routinely commemorated annually: Christmas and April Fool’s Day.[20]

The Friday and Saturday puzzles, the most difficult, are usually themeless and «wide open», with fewer black squares and more long words. The maximum word count for a themed weekday puzzle is normally 78 words, while the maximum for a themeless Friday or Saturday puzzle is 72; Sunday puzzles must contain 140 words or fewer.[8] Given the Times‘s reputation as a paper for a literate, well-read, and somewhat arty audience, puzzles frequently reference works of literature, art, or classical music, as well as modern TV, movies, or other touchstones of popular culture.[8]

The puzzle follows a number of conventions, both for tradition’s sake and to aid solvers in completing the crossword:

- Nearly all the Times crossword grids have rotational symmetry: they can be rotated 180 degrees and remain identical. Rarely, puzzles with only vertical or horizontal symmetry can be found; yet rarer are asymmetrical puzzles, usually when an unusual theme requires breaking the symmetry rule. Starting in January 2020, diagonal symmetry began appearing in Friday and Saturday puzzles. This rule has been part of the puzzle since the beginning; when asked why, initial editor Margaret Farrar is said to have responded, «Because it is prettier.»[10]

- Any time a clue contains the tag «abbr.» or an abbreviation more significant than «e.g.», the answer will be an abbreviation (e.g., M.D. org. = AMA).[6]

- Any time a clue ends in a question mark, the answer is a play on words.[6] (e.g., Fitness center? = CORE)

- Occasionally, themed puzzles will require certain squares to be filled in with a symbol, multiple letters, or a word, rather than one letter (so-called «rebus» puzzles). This symbol/letters/word will be repeated in each themed entry. For example, the December 6, 2012, puzzle by Jeff Chen featured a rebus theme based on the chemical pH scale used for acids and bases, which required the letters «pH» to be written together in a single square in several entries (in the middle of entries such as «triumpH» or «sopHocles»).[21]

- French-, Spanish-, or Latin-language answers, and more rarely answers from other languages are indicated either by a tag in the clue giving the answer language (e.g., ‘Summer: Fr.’ = ETE) or by the use in the clue of a word from that language, often a personal or place name (e.g. ‘Friends of Pierre’ = AMIS or ‘The ocean, e.g., in Orleans’ = EAU).[6]

- Clues and answers must always match in part of speech, tense, number, and degree. Thus a plural clue always indicates a plural answer (and the same for singular), a clue in the past tense will always be matched by an answer in the same tense, and a clue containing a comparative or superlative will always be matched by an answer in the same degree.[6]

- The answer word (or any of the answer words, if it consists of multiple words) will not appear in the clue itself. Unlike in some easier puzzles in other outlets, the number of words in the answer is not given in the clue—so a one-word clue can have a multiple-word answer.[22]

- The theme, if any, will be applied consistently throughout the puzzle; e.g., if one of the theme entries is a particular variety of pun, all the theme entries will be of that type.[8]

- In general, any words that might appear elsewhere in the newspaper, such as well-known brand names, pop culture figures, or current phrases of the moment, are fair game.[23]

- No entries involving profanity, sad or disturbing topics, or overly explicit answers should be expected, though some have sneaked in. The April 3, 2006, puzzle contained the word SCUMBAG (a slang term for a condom), which had previously appeared in a Times article quoting people using the word. Shortz apologized and said the term would not appear again.[24][25] PENIS also appeared once in a Shortz-edited puzzle in 1995, clued as «The __ mightier than the sword.»[26]

- Spoken phrases are always indicated by enclosure in quotation marks, e.g., «Get out of here!» = LEAVE NOW.[22]

- Short exclamations are sometimes clued by a phrase in square brackets, e.g., «[It’s cold!]» = BRR.[22]

- When the answer can only be substituted for the clue when preceding a specific other word, this other word is indicated in parentheses. For example, «Think (over)» = MULL, since «mull» only means «think» when preceding the word «over» (i.e., “think over” and «mull over» are synonymous, but «think» and «mull» are not necessarily synonymous otherwise). The point here is that the single word «think» can be replaced by the single word «mull», but only when the following word is «over».

- When the answer needs an additional word in order to fit the clue, this other word is indicated with the use of «with». For example, «Become understood, with in» = SINK, since «Sink in» (but not «Sink» alone) means «to become understood.» The point here is that the single phrase «become understood» can be replaced with the single phrase «sink in», regardless of whether it is followed by anything else.

- Times style is to always capitalize the first letter of a clue, regardless of whether the clue is a complete sentence or whether the first word is a proper noun. On occasion, this is used to deliberately create difficulties for the solver; e.g., in the clue «John, for one», it is ambiguous whether the clue is referring to the proper name John or to the slang term for a bathroom.[22]

Variety puzzles[edit]

Second Sunday puzzles[edit]

In addition to the primary crossword, the Times publishes a second Sunday puzzle each week, of varying types, something that the first crossword editor, Margaret Farrar, saw as a part of the paper’s Sunday puzzle offering from the start; she wrote in a memo when the Times was considering whether or not to start running crosswords that «The smaller puzzle, which would occupy the lower part of the page, could provide variety each Sunday. It could be topical, humorous, have rhymed definitions or story definitions or quiz definitions. The combination of these two would offer meat and dessert, and catch the fancy of all types of puzzlers.»[10] Currently, every other week is an acrostic puzzle authored by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon, with a rotating selection of other puzzles, including diagramless crosswords, Puns and Anagrams, cryptics (a.k.a. «British-style crosswords»), Split Decisions, Spiral Crosswords, word games, and more rarely, other types (some authored by Shortz himself—the only puzzles he has created for the Times during his tenure as crossword editor).[18] Of these types, the acrostic has the longest and most interesting history, beginning on May 9, 1943, authored by Elizabeth S. Kingsley, who is credited with inventing the puzzle type, and continued to write the Times acrostic until December 28, 1952.[27] From then until August 13, 1967, it was written by Kingsley’s former assistant, Doris Nash Wortman; then it was taken over by Thomas H. Middleton for a period of over 30 years, until August 15, 1999, when the pair of Cox and Rathvon became just the fourth author of the puzzle in its history.[27] The name of the puzzle also changed over the years, from «Double-Crostic» to «Kingsley Double-Crostic,» «Acrostic Puzzle,» and finally (since 1991) just «Acrostic.»[27]

Other puzzles[edit]

As well as a second word puzzle on Sundays, the Times publishes a KenKen numbers puzzle (a variant of the popular sudoku logic puzzles) each day of the week.[18] The KenKen and second Sunday puzzles are available online at the New York Times crosswords and games page, as are «SET!» logic puzzles, a word search variant called «Spelling Bee» in which the solver uses a hexagonal diagram of letters to spell words of four or more letters in length, and a monthly bonus crossword with a theme relating to the month.[18] The Times Online also publishes a daily «mini» crossword by Joel Fagliano, which is 5×5 Sunday through Friday and 7×7 on Saturdays and is significantly easier than the traditional daily puzzle. Other «mini» and larger 11×11 «midi» puzzles are sometimes offered as bonuses.

Records and puzzles of note[edit]

Fans of the Times crossword have kept track of a number of records and interesting puzzles (primarily from among those published in Shortz’s tenure), including those below. (All puzzles published from November 21, 1993, on are available to online subscribers to the Times crossword.)[18]

- Fewest words in a daily 15×15 puzzle: 50 words, on Saturday, June 29, 2013, by Joe Krozel;[28] in a Sunday puzzle: 120 words on August 21, 2022, by Brooke Husic and Will Nediger.[29][30]

- Most words in a daily puzzle: 86 words on Tuesday, December 23, 2008, by Joe Krozel;[28][31] in a 21×21 Sunday puzzle: 150 words, on June 26, 1994, by Nancy Nicholson Joline and on November 21, 1993, by Peter Gordon (the first Sunday puzzle edited by Will Shortz)[29]

- Fewest black squares (in a daily 15×15 puzzle): 17 blocks, on Friday, July 27, 2012, by Joe Krozel[32][33]

- Most prolific author: Manny Nosowsky is the crossword constructor who has been published most frequently in the Times under Shortz, with 241 puzzles (254 including pre-Shortz-era puzzles, published before 1993), although others may have written more puzzles than that under prior editors. The record for most Sunday puzzles is held by Jack Luzzato, with 119 (including two written under pseudonyms);[35] former editor Eugene T. Maleska wrote 110 himself, including 8 under other names.[35]

- Youngest constructor: Daniel Larsen, aged 13 years and 4 months.[36]

- Oldest constructor: Bernice Gordon was 100 on August 11, 2014, when her final Times crossword was published.[37] (She died in 2015 at the age of 101.)[38] Gordon published over 150 crosswords in the Times since her first puzzle was published by Margaret Farrar in 1952.[39]

- Greatest difference in ages between two constructors of a single puzzle: 83, a puzzle by David Steinberg (age 16) and Bernice Gordon (age 99) with the theme AGE DIFFERENCE.[40][41]

- 15-letter-word stacks: On December 29, 2012, Joe Krozel stacked five 15-letter entries, something never before or since achieved. Krozel, Martin Ashwood-Smith, George Barany and Erik Agard have stacked four 15-letter entries in a puzzle. Since 2010, Krozel, Ashwood-Smith, Kevin G. Der, and Jason Flinn have stacked two sets of four 15-letter entries in a puzzle.[42]

- Lowest word count for a debut puzzle: 62 words, on Saturday, June 1, 2019, by Ari Richter.

A few crosswords have achieved recognition beyond the community of crossword solvers. Perhaps the most famous is the November 5, 1996, puzzle by Jeremiah Farrell, published on the day of the U.S. presidential election, which has been featured in the movie Wordplay and the book The Crossword Obsession by Coral Amende, as well as discussed by Peter Jennings on ABC News, featured on CNN, and elsewhere.[12][13][43][44] The two leading candidates that year were Bill Clinton and Bob Dole; in Farrell’s puzzle one of the long clue/answer combinations read «Title for 39-Across next year» = MISTER PRESIDENT. The remarkable feature of the puzzle is that 39-Across could be answered either CLINTON or BOB DOLE, and all the Down clues and answers that crossed it would work either way (e.g., «Black Halloween animal» could be either BAT or CAT depending on which answer you filled in at 39-Across; similarly «French 101 word» could equal LUI or OUI, etc.).[43] Constructors have dubbed this type of puzzle a Schrödinger or quantum puzzle after the famous paradox of Schrödinger’s cat, which was both alive and dead at the same time. Since Farrell’s invention of it, 16 other constructors—Patrick Merrell, Ethan Friedman, David J. Kahn, Damon J. Gulczynski, Dan Schoenholz, Andrew Reynolds, Kacey Walker and David Quarfoot (in collaboration), Ben Tausig, Timothy Polin, Xan Vongsathorn, Andrew Kingsley and John Lieb (in collaboration), Zachary Spitz, David Steinberg and Stephen McCarthy have used a similar trick.[45]

In another notable Times crossword, 27-year-old Bill Gottlieb proposed to his girlfriend, Emily Mindel, via the crossword puzzle of January 7, 1998, written by noted crossword constructor Bob Klahn.[46][47] The answer to 14-Across, «Microsoft chief, to some» was BILLG, also Gottlieb’s name and last initial. 20-Across, «1729 Jonathan Swift pamphlet», was A MODEST PROPOSAL. And 56-Across, «1992 Paula Abdul hit», was WILL YOU MARRY ME. Gottlieb’s girlfriend said yes. The puzzle attracted attention in the AP, an article in the Times itself, and elsewhere.[47] Other Times crosswords with a notable wedding element include the June 25, 2010, puzzle by Byron Walden and Robin Schulman, which has rebuses spelling I DO throughout, and the January 8, 2020, puzzle by Joon Pahk and Amanda Yesnowitz, which was used at the latter’s wedding reception.

On May 7, 2007, former U.S. president Bill Clinton, a self-professed long-time fan of the Times crossword, collaborated with noted crossword constructor Cathy Millhauser on an online-only crossword in which Millhauser constructed the grid and Clinton wrote the clues.[16][48] Shortz described the President’s work as «laugh out loud» and noted that he as editor changed very little of Clinton’s clues, which featured more wordplay than found in a standard puzzle.[16][48] Clinton made his print constructing debut on Friday, May 12, 2017, collaborating with Vic Fleming on one of the co-constructed puzzles celebrating the crossword’s 75th Anniversary.[49]

The Times crossword of Thursday, April 2, 2009, by Brendan Emmett Quigley,[50] featured theme answers that all ran the gamut of movie ratings—beginning with the kid-friendly «G» and finishing with adults-only «X» (now replaced by the less crossword-friendly «NC-17»). The seven theme entries were GARY GYGAX, GRAND PRIX, GORE-TEX, GAG REFLEX, GUMMO MARX, GASOLINE TAX, and GENERATION X. In addition, the puzzle contained the clues/answers of «‘Weird Al’ Yankovic’s ‘__ on Jeopardy‘» = I LOST and «I’ll take New York Times crossword for $200, __» = ALEX. What made the puzzle notable is that the prior night’s episode of the US television show Jeopardy! featured video clues of Will Shortz for five of the theme answers (all but GARY GYGAX and GENERATION X) which the contestants attempted to answer during the course of the show.

Controversies[edit]

The Times crossword has been criticized for a lack of diversity in its constructors and clues. Major crosswords like those in the Times have historically been largely written, edited, fact-checked, and test-solved by older white men.[51] Less than 30% of puzzle constructors in the Shortz Era have been women.[52] In the 2010s, only 27% of clued figures were female, and 20% were of minority racial groups.[53]

In January 2019, the Times crossword was criticized for including the racial slur «BEANER» (clued as «Pitch to the head, informally», but also a derogatory slur for Mexicans).[54] Shortz apologized for the distraction this may have caused solvers, claiming that he had never heard the slur before.[55]

In 2022, the Times was criticized after many readers claimed that its December 18 crossword grid resembled a Nazi swastika.[56] Some were particularly upset that the puzzle was published on the first night of Hanukkah.[57] In a statement, the Times said the resemblance was unintentional, stemming from the grid’s rotational symmetry.[58] The Times was also criticized in 2017 and 2014 for crossword grids that resembled a swastika, which it both times defended as a coincidence.[56][59]

See also[edit]

- Wordplay, a 2006 documentary about the crossword

References[edit]

- ^ «New York Times News Service/Syndicate». October 18, 2006. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ New York Times Crosswords for BlackBerry

- ^ «Official New York Times Crossword Puzzle Game Released – TouchArcade». Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ New York Times Crosswords for Kindle Fire

- ^ New York Times Crosswords for Barnes and Noble Nook

- ^ a b c d e f Shortz, Will (April 8, 2001). «ENDPAPER: HOW TO; Solve The New York Times Crossword Puzzle». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ «Crossword Puzzle Archive — 1999 — Premium — NYTimes.com». www.nytimes.com. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d «New York Times Specification Sheet». www.cruciverb.com. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ (Unsigned Editorial) «Topics of the Times» The New York Times, November 17, 1924. Retrieved on March 13, 2009. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g Richard F. Shepard «Bambi is a Stag and Tubas Don’t Go ‘Pah-Pah’: The Ins and Outs of Across and Down» The New York Times Magazine, February 16, 1992. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ Will Shortz «150th Anniversary: 1851–2001; The Addiction Begins» The New York Times, November 14, 2001. Retrieved on 2009-13-13.

- ^ a b Author unknown. «A Puzzling Occupation: Will Shortz, Enigmatologist» Biography of Will Shortz from American Crossword Puzzle Tournament homepage, dated March 1998. Retrieved on 2009-03-13.

- ^ a b Leora Baude «Nice Work if You Can Get It», Indiana University College of Arts and Sciences, January 19, 2001. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ Will Shortz «CROSSWORD MEMO; What’s in a Name? Five Letters or Less» The New York Times, March 9, 2003. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c David Germain «Crossword guru Shortz brings play on words to Sundance» Associated Press, January 23, 2006. Retrieved on March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c «Bill Clinton pens NY Times’ crossword puzzle» Reuters 2007-05-07. Retrieved on 2009-03-13.

- ^ a b New York Times store – crossword books

- ^ a b c d e The New York Times crossword puzzle online (subscription required)

- ^ «Thumbnails». XWordInfo. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Account of 2008 presentation by Will Shortz. Retrieved on 2009-03.13]

- ^ Amlen, Deb (December 5, 2012). «Theme of this Puzzle». «Wordplay» blog. The New York Times. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Amlen, Deb (November 30, 2017). «How to Solve the New York Times Crossword». The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ Hiltner, Stephen (August 1, 2017). «Will Shortz: A Profile of a Lifelong Puzzle Master». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ New York Times Crossword Forum, April 4, 2006

- ^ Sheidlower, Jesse (April 6, 2006). «The dirty word in 43 Down». Slate Magazine. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ «New York Times crossword for August 27, 1995». Xwordinfo.com. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c History of the Times acrostic puzzle Archived February 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Xwordinfo.com

- ^ a b Xwordinfo.com

- ^ «Sun Aug 21, 2022 NYT crossword by Brooke Husic & Will Nediger». Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ record high 86-word puzzle (subscription required)

- ^ July 27, 2012 puzzle with record low black square count (subscription required)

- ^ .Xwordinfo.com

- ^ Xwordinfo.com

- ^ a b New York Times Crossword «Database»

- ^ Shortz, Will (February 14, 2017). «The Youngest Crossword Constructor in New York Times History». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- ^ Amlen, Deb (January 14, 2014). «Location, Location, Location». Wordplay: The Crossword Blog of The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (January 30, 2015). «Bernice Gordon, Crossword Creator for The Times, Dies at 101». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ^ Mucha, Peter. «Construction worker Bernice Gordon, 95, has been coming across with downright nifty crossword puzzles for 60 years». The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- ^ «New York Times, Wednesday, June 26, 2013». XWord Info. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Amlen, Deb (June 25, 2013). «Four Score and Three». Wordplay, The Crossword Blog of the New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Horne, Jim. «Stacks». XWordInfo. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Amende, Coral (1996) The Crossword Obsession, Berkley Books: New York ISBN 978-0756790868

- ^ Ali Velshi «Business Unusual: Will Shortz», CNN

- ^ «Quantum». xwordinfo.com. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ January 7, 1998 wedding proposal crossword (subscription required)

- ^ a b James Barron «Two Who Solved the Puzzle of Love», The New York Times, January 8, 1998. Retrieved on October 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Cathy Millhauser (constructor) and Bill Clinton (clues); edited by Will Shortz «Twistin’ the Oldies» The New York Times (web only) 2005-05-07. Retrieved on 2009-03-13. (Bill Clinton’s Times crossword, available via PDF or Java applet.)

- ^ «Friday, May 12, 2017 crossword by Bill Clinton and Victor Fleming». www.xwordinfo.com. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ April 2, 2009 puzzle featured on «Jeopardy!» (subscription required)

- ^ Last, Natan (March 18, 2020). «The Hidden Bigotry of Crosswords». The Atlantic. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ «XWord Info». www.xwordinfo.com. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ «Who’s in the Crossword?». The Pudding. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Flood, Brian (January 2, 2019). «New York Times apologizes for including racial slur in crossword puzzle: ‘It is simply not acceptable’«. Fox News. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Welk, Brian (January 2, 2019). «NY Times Crossword Editor Apologizes for ‘Slur’ in New Year’s Day Puzzle». TheWrap. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Kilander, Gustaf (December 19, 2022). «New York Times responds after readers accuse paper of swastika-shaped crossword puzzle». The Independent. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Silverstein, Joe (December 18, 2022). «NY Times Sunday crossword puzzles readers with swastika shape on Hanukkah: ‘How did this get approved’«. Fox News. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (December 19, 2022). «The New York Times speaks out on claims its crossword resembles swastika». Newsweek. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ «‘NYT’ Response to Prior Crossword Swastika Accusations Resurfaces». MSN. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

External links[edit]

- Official website (subscription required)

- «New York Times Crossword Archive». The New York Times. From before 2000c.

- «New York Times Crossword Solver». (Unaffiliated). Archive from 1980 forward.

About New York Times Games

Since the launch of The Crossword in 1942, The Times has captivated solvers by providing engaging word and logic games. In 2014, we introduced The Mini Crossword — followed by Spelling Bee, Letter Boxed, Tiles and Vertex. In early 2022, we proudly added Wordle to our collection. We strive to offer puzzles for all skill levels that everyone can enjoy playing every day.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

New York Times Games

- The Crossword

- The Mini Crossword

- Spelling Bee

- Wordle

- Tiles

- Letter Boxed

- Vertex

- Sudoku

- All Games

Crosswords

- Crossword Archives

- Statistics

- Leaderboards

- Submit a Crossword

Community

- Gameplay Stories

- Spelling Bee Forum

- Games Twitter

Learn More

- FAQs

- Gift Subscriptions

- Shop the Games Collection

- Download the App

- Contact Us

- © 2023 The New York Times Company

- NYTimes.com

- Sitemap

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

When crossword puzzles first swept across North America in the mid-1920s, the New York Times sneered, calling them “a familiar form of madness”and the next fad after MahJong. Claims these puzzles were good mental exercise and a way to expand one’s personal lexicon, via a dictionary, were dismissed.

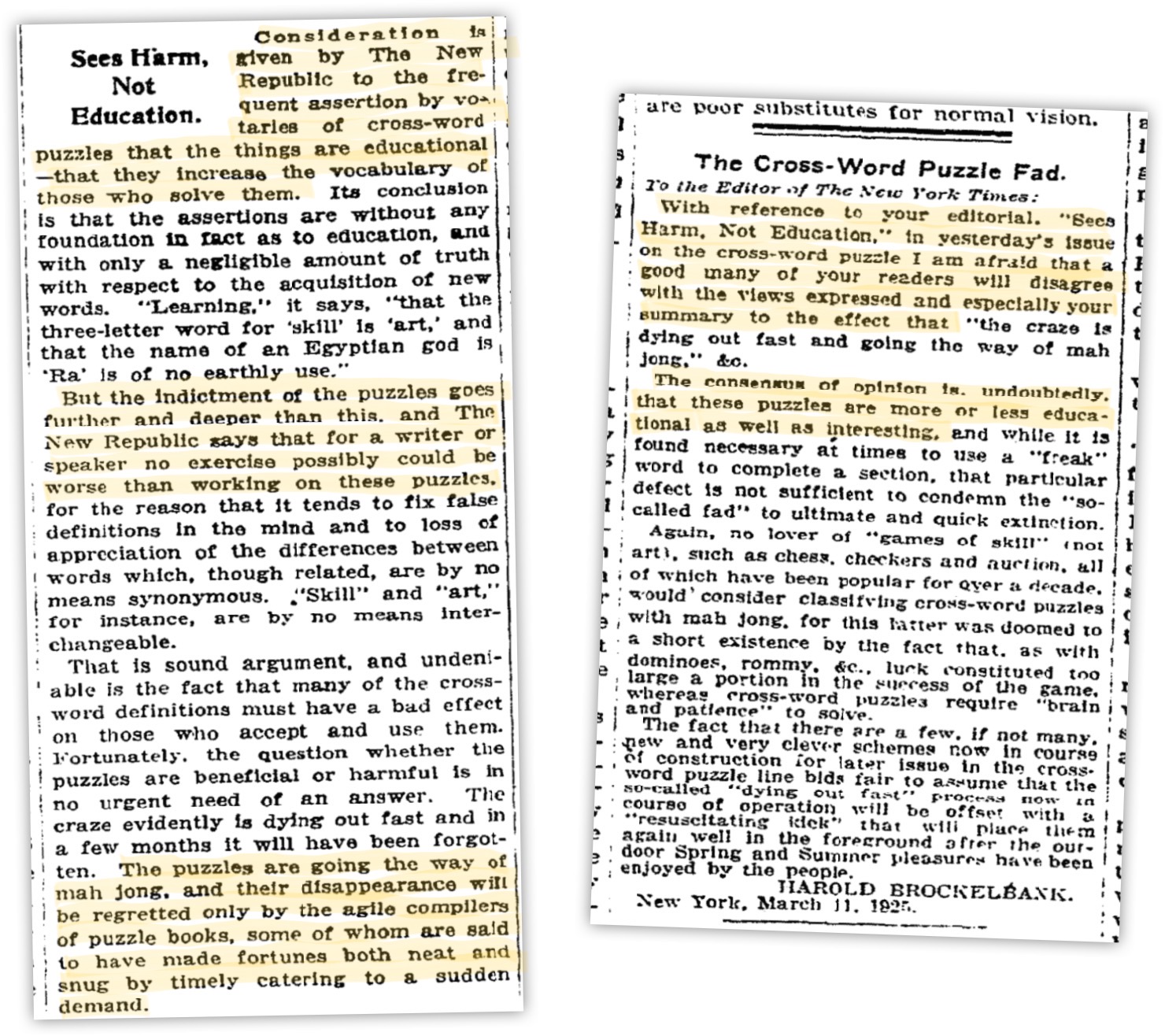

In another piece published the following year titled “See Harm Not Education,” The Times argued that learning obscure three-letter words was useless — but it didn’t stop there. “The indictment of the puzzles goes further and deeper,” it said, citing The New Republic, which posited that there wasn’t a worse exercise for writers and speakers due to it fixing “false definitions in the mind.”

This piece prompted a letter to the editor by a reader who retorted, “I am afraid that a good many of your readers will disagree with the views expressed,” pointing out that it was generally agreed that crosswords were educational.

Crossword puzzles: a national menace

This animosity makes more sense when you understand the origins of crossword puzzles in America: They were popularized via the pages of the original tabloid, The New York World, the “new media” of the day. As far as the journalistic establishment was concerned, crosswords were another mindless fad used as a substitute for good editorial, to keep readers coming back — much like Buzzfeed quizzes were in the 2010s. Tabloids were looked upon as trashy, childish, and plebeian and were labeled the “yellow press” after one of the numerous comic strips contained within them. The New York Times would refuse to publish crosswords for another two decades.

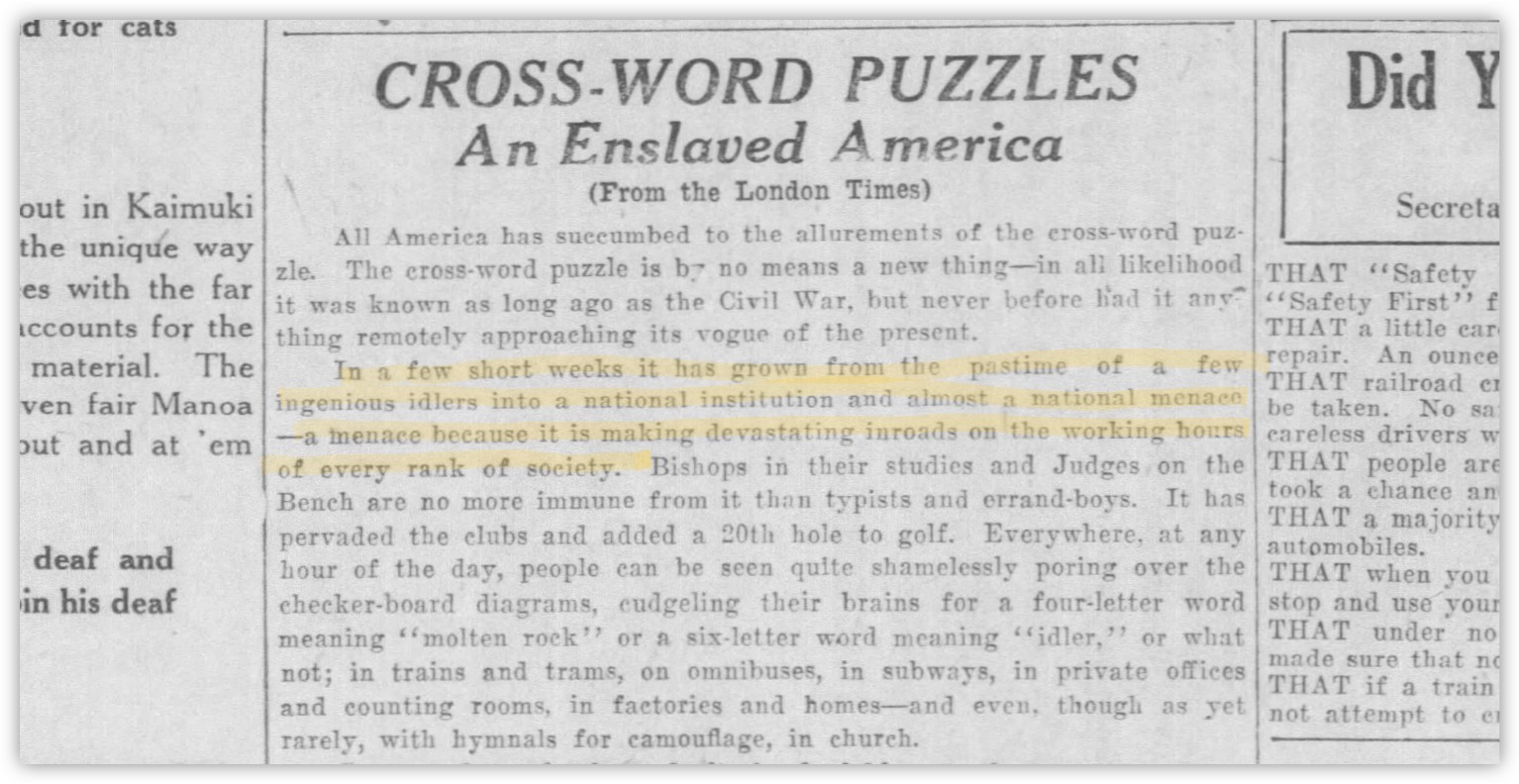

Across the Atlantic in the United Kingdom, the Times of London reported on the U.S. crossword craze with similar disdain, using an ironically tabloidesque headline “An Enslaved America.” Published in 1924, it read:

“All America has succumbed to the allurements of the cross-word puzzle. In a few short weeks it has grown from the pastime of a few ingenious idlers into a national institution and almost a national menace: a menace because it is making devastating inroads on the working hours of every rank of society.”

The omnipresence of crosswords in the U.S. was described in detail. This “fad” was “in trains and trams on omnibuses, in subways, in private offices and counting rooms, in factories and homes, and even — though as yet rarely — with hymnals for camouflage, in church.” Along with other modern trends, the crossword had supposedly “dealt the final blow to the art of conversations.”

Crossword puzzles: an invasive weed

In its estimate, over ten million people spent half an hour each day working out the puzzles when they should be working, noting “this loss to productive activity of far more time than is lost by labor strikes.” It even compared them to an invasive weed, stating “The cross-word puzzle threatens to be the wild hyacinth of American industry.”

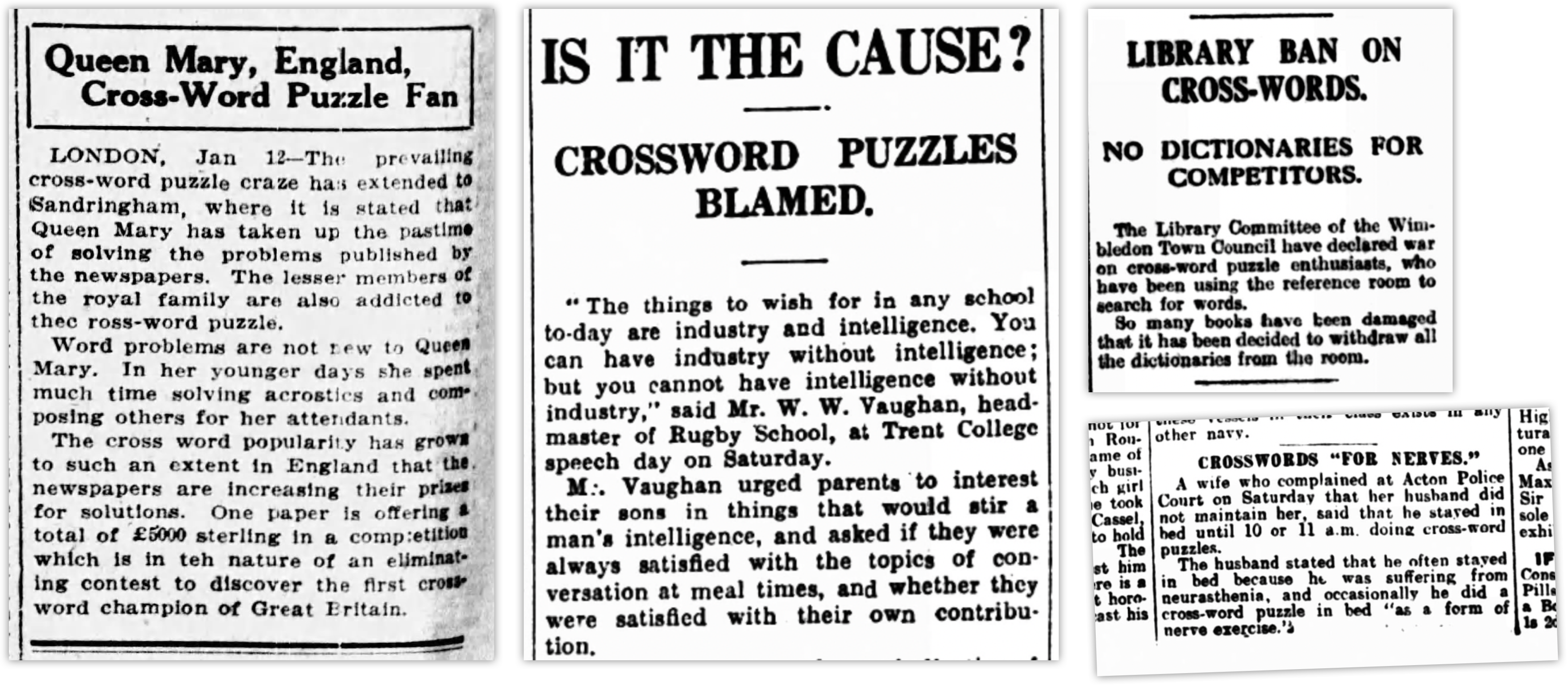

Subscribe for counterintuitive, surprising, and impactful stories delivered to your inbox every Thursday

Judging by reports at the time, this proverbial “wild hyacinth” had invaded the UK by the following year, when reports of Queen Mary — wife of King George V — taking up the pastime appeared. Headmasters scorned them as the “the laziest occupation” and an “unsociable habit.” One British wife took her husband to court for staying in bed until 11 am doing crosswords. Public libraries fought a “war on crosswords” by blotting out the games in their freely available newspapers and limiting access to dictionaries within reading rooms.

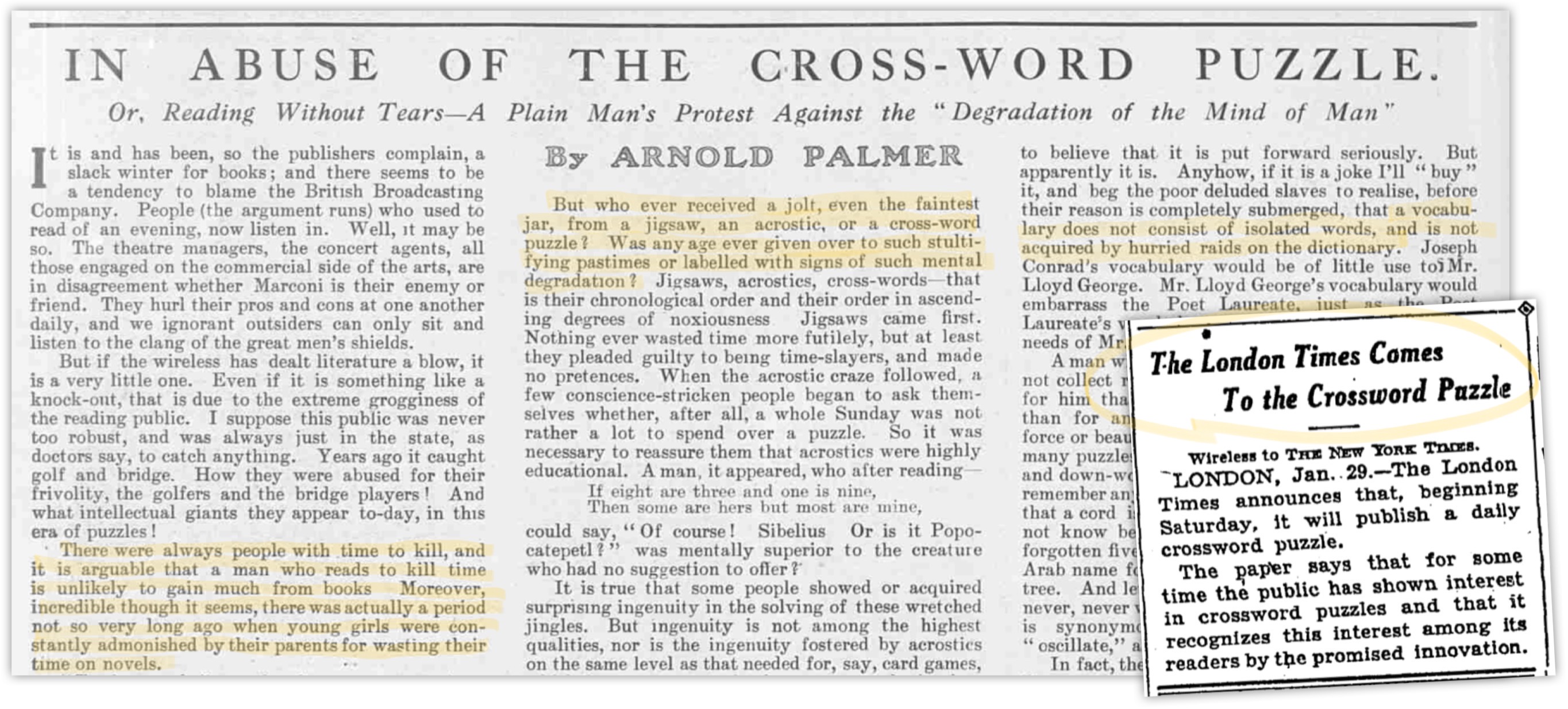

An essay titled “In Abuse of the Cross-Word Puzzle” noted that early adopters of golf and bridge were abused for their frivolity but now appeared intellectual giants “in this era of puzzles!” — failing to learn a lesson from history, namely, that crosswords would eventually be seen as intellectual too. “Incredible though it may seem,” it also noted, novel reading was scorned by parents not long ago too. Crossword puzzles (and jigsaws) were different according to the author: “Was any age ever given over to such stultifying pastimes or labeled with signs of such mental degradation?”

Less than five years after it derided them, the Times of London would give in and print its first crossword puzzle.

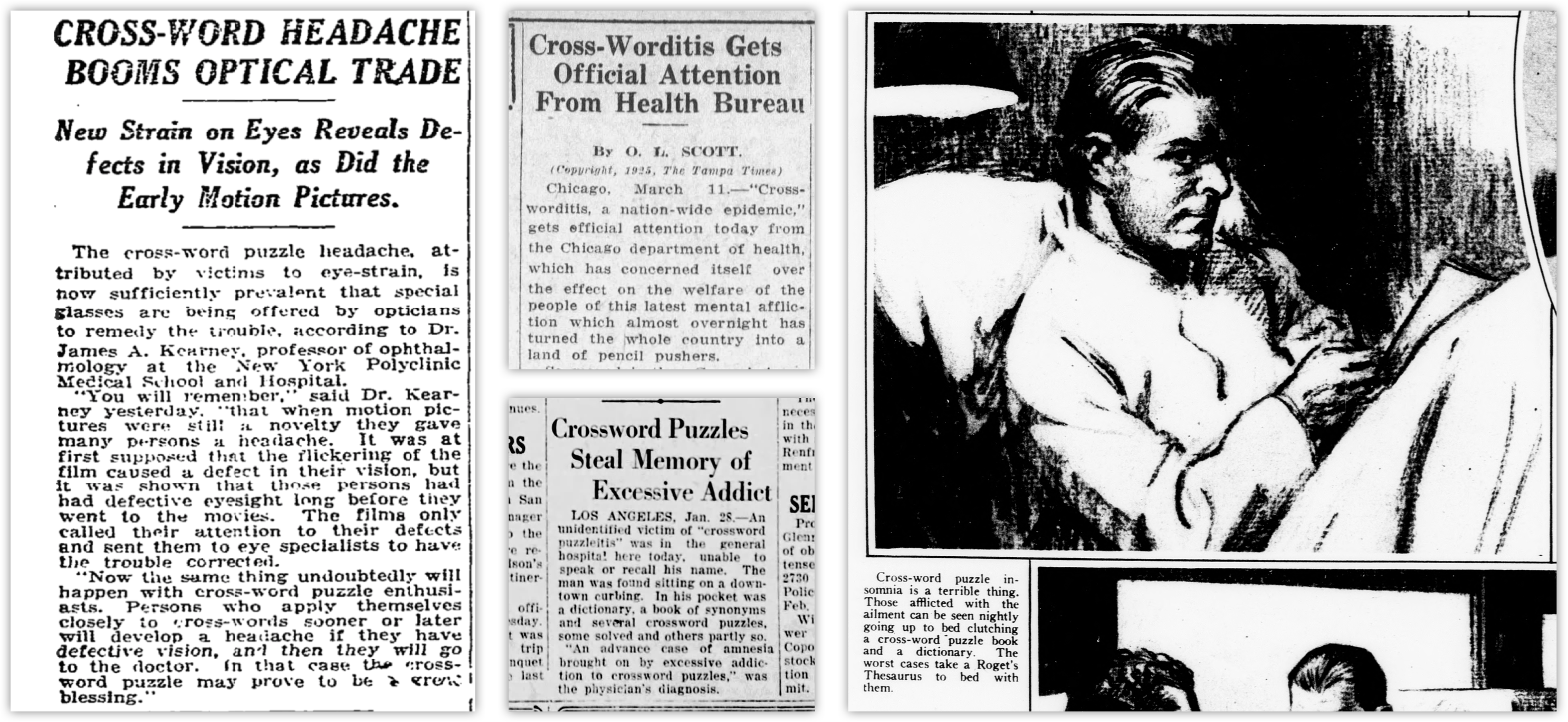

A mental illness called “crossword puzzleitis”

Back in the U.S., the crossword puzzle habit was being pathologized and medicalized, and the term “crossword puzzleitis” was coined — likely in jest — but it would eventually get attention from medical authorities and physicians. One doctor concluded “crossword puzzleitis” “stole” the memories of his patient. “Crossword insomnia” was another phenomenon reported, akin to late-night smartphone fiddling. Optometrists claimed the habit caused headaches and weakened eyesight.

Magistrates lambasted court attendants, policemen, lawyers, and their clients for “clogging up the wheels of justice” by pondering over the puzzles. Academics made similar complaints about their students, and the University of Michigan instituted an outright ban in lecture halls.

Crosswords, the cause of all societal problems

Crosswords were cited as a reason for divorce in more than one case, receiving widespread press attention, including from the New York Times, which ran the headline “Crossword Mania Breaks Up Homes.” Other papers published amusing cartoons featuring weeping grooms and puzzle-engrossed brides.

American libraries had the same complaints as British ones in regard to their effect on library habits, and when the U.S. district attorney was two hours late to a speaking engagement, he blamed a crossword puzzle that he started on the train ride. Physical assault and even murder-suicide were blamed on the crossword puzzle too.

Ironically, many of these sensationalist reports appeared in the very papers printing them, sometimes right next to the crosswords themselves.

Newspaper editors defended them, insisting they were beneficial, but it was unconvincing since they were financially benefiting from the craze. Eventually the New York Times relented, as the U.S. entered World War II — editors decided people needed a distraction and escape. The Gray Lady printed its first in February 1942, and it would become the most famous and coveted crossword in the world.

Welcome, Wordle

A century later, word game manias are still happening. Scrabble saw a renaissance on the web and then mobile via Words with Friends in the 2010s. Earlier last year saw the indomitable rise of Wordle — a familiar madness — first gaining mainstream coverage in the New York Times. It was praised as free from the pressures of the hyper-capitalist attention economy. Its constraint of one game per day was held up as enforced digital moderation, ignoring its Pavlovian-esque nature. It was supposedly fun for the sake of fun, not profit and attention.

Then on January 31st, the New York Times announced they had bought Wordle for a figure in the “low seven figures” from its creator, promising to keep it free “initially.” Regarding the acquisition, The Times called games an “essential part of its strategy” to increase subscriptions: fun and moreish brain teasers to make the New York Times a part of one’s daily routine, just like the New York World did almost a century ago.