From Typewriters to Word Processors

Before we consider the special tools that the UNIX environment provides for text processing, we need to think about the underlying changes in the process of writing that are inevitable when you begin to use a computer.

The most important features of a computer program for writers are the ability to remember what is typed and the ability to allow incremental changes—no more retyping from scratch each time a draft is revised. For a writer first encountering word-processing software, no other features even begin to compare. The crudest command structure, the most elementary formatting capabilities, will be forgiven because of the immense labor savings that take place.

Writing is basically an iterative process. It is a rare writer who dashes out a finished piece; most of us work in circles, returning again and again to the same piece of prose, adding or deleting words, phrases, and sentences, changing the order of thoughts, and elaborating a single sentence into pages of text.

A writer working on paper periodically needs to clear the deck—to type a clean copy, free of elaboration. As the writer reads the new copy, the process of revision continues, a word here, a sentence there, until the new draft is as obscured by changes as the first. As Joyce Carol Oates is said to have remarked: “No book is ever finished. It is abandoned.”

Word processing first took hold in the office as a tool to help secretaries prepare perfect letters, memos, and reports. As dedicated word processors were replaced with low-cost personal computers, writers were quick to see the value of this new tool. In a civilization obsessed with the written word, it is no accident that WordStar, a word-processing program, was one of the first best sellers of the personal computer revolution.

As you learn to write with a word processor, your working style changes. Because it is so easy to make revisions, it is much more forgivable to think with your fingers when you write, rather than to carefully outline your thoughts beforehand and polish each sentence as you create it.

If you do work from an outline, you can enter it first, then write your first draft by filling in the outline, section by section. If you are writing a structured document such as a technical manual, your outline points become the headings in your document; if you are writing a free-flowing work, they can be subsumed gradually in the text as you flesh them out. In either case, it is easy to write in small segments that can be moved as you reorganize your ideas.

Watching a writer at work on a word processor is very different from watching a writer at work on a typewriter. A typewriter tends to enforce a linear flow—you must write a passage and then go back later to revise it. On a word processor, revisions are constant—you type a sentence, then go back to change the sentence above. Perhaps you write a few words, change your mind, and back up to take a different tack; or you decide the paragraph you just wrote would make more sense if you put it ahead of the one you wrote before, and move it on the spot.

This is not to say that a written work is created on a word processor in a single smooth flow; in fact, the writer using a word processor tends to create many more drafts than a compatriot who still uses a pen or typewriter. Instead of three or four drafts, the writer may produce ten or twenty. There is still a certain editorial distance that comes only when you read a printed copy. This is especially true when that printed copy is nicely formatted and letter perfect.

This brings us to the second major benefit of word-processing programs: they help the writer with simple formatting of a document. For example, a word processor may automatically insert carriage returns at the end of each line and adjust the space between words so that all the lines are the same length. Even more importantly, the text is automatically readjusted when you make changes. There are probably commands for centering, underlining, and boldfacing text.

The rough formatting of a document can cover a multitude of sins. As you read through your scrawled markup of a preliminary typewritten draft, it is easy to lose track of the overall flow of the document. Not so when you have a clean copy—the flaws of organization and content stand out vividly against the crisp new sheets of paper.

However, the added capability to print a clean draft after each revision also puts an added burden on the writer. Where once you had only to worry about content, you may now find yourself fussing with consistency of margins, headings, boldface, italics, and all the other formerly superfluous impedimenta that have now become integral to your task.

As the writer gets increasingly involved in the formatting of a document, it becomes essential that the tools help revise the document’s appearance as easily as its content. Given these changes imposed by the evolution from typewriters to word processors, let’s take a look at what a word-processing system needs to offer to the writer.

▪ A Workspace ▪

One of the most important capabilities of a word processor is that it provides a space in which you can create documents. In one sense, the video display screen on your terminal, which echoes the characters you type, is analogous to a sheet of paper. But the workspace of a word processor is not so unambiguous as a sheet of paper wound into a typewriter, that may be added neatly to the stack of completed work when finished, or torn out and crumpled as a false start. From the computer’s point of view, your workspace is a block of memory, called a buffer, that is allocated when you begin a word-processing session. This buffer is a temporary holding area for storing your work and is emptied at the end of each session.

To save your work, you have to write the contents of the buffer to a file. A file is a permanent storage area on a disk (a hard disk or a floppy disk). After you have saved your work in a file, you can retrieve it for use in another session.

When you begin a session editing a document that exists on file, a copy of the file is made and its contents are read into the buffer. You actually work on the copy, making changes to it, not the original. The file is not changed until you save your changes during or at the end of your work session. You can also discard changes made to the buffered copy, keeping the original file intact, or save multiple versions of a document in separate files.

Particularly when working with larger documents, the management of disk files can become a major effort. If, like most writers, you save multiple drafts, it is easy to lose track of which version of a file is the latest.

An ideal text-processing environment for serious writers should provide tools for saving and managing multiple drafts on disk, not just on paper. It should allow the writer to

- work on documents of any length;

- save multiple versions of a file;

- save part of the buffer into a file for later use;

- switch easily between multiple files;

- insert the contents of an existing file into the buffer;

- summarize the differences between two versions of a document.

Most word-processing programs for personal computers seem to work best for short documents such as the letters and memos that offices churn out by the millions each day. Although it is possible to create longer documents, many features that would help organize a large document such as a book or manual are missing from these programs.

However, long before word processors became popular, programmers were using another class of programs called text editors. Text editors were designed chiefly for entering computer programs, not text. Furthermore, they were designed for use by computer professionals, not computer novices. As a result, a text editor can be more difficult to learn, lacking many on-screen formatting features available with most word processors.

Nonetheless, the text editors used in program development environments can provide much better facilities for managing large writing projects than their office word-processing counterparts. Large programs, like large documents, are often contained in many separate files; furthermore, it is essential to track the differences between versions of a program.

UNIX is a pre-eminent program development environment and, as such, it is also a superb document development environment. Although its text editing tools at first may appear limited in contrast to sophisticated office word processors, they are in fact considerably more powerful.

▪ Tools for Editing ▪

For many, the ability to retrieve a document from a file and make multiple revisions painlessly makes it impossible to write at a typewriter again. However, before you can get the benefits of word processing, there is a lot to learn.

Editing operations are performed by issuing commands. Each word-processing system has its own unique set of commands. At a minimum, there are commands to

- move to a particular position in the document;

- insert new text;

- change or replace text;

- delete text;

- copy or move text.

To make changes to a document, you must be able to move to that place in the text where you want to make your edits. Most documents are too large to be displayed in their entirety on a single terminal screen, which generally displays 24 lines of text. Usually only a portion of a document is displayed. This partial view of your document is sometimes referred to as a window.* If you are entering new text and reach the bottom line in the window, the text on the screen automatically scrolls (rolls up) to reveal an additional line at the bottom. A cursor (an underline or block) marks your current position in the window.

There are basically two kinds of movement:

- scrolling new text into the window

- positioning the cursor within the window

When you begin a session, the first line of text is the first line in the window, and the cursor is positioned on the first character. Scrolling commands change which lines are displayed in the window by moving forward or backward through the document. Cursor-positioning commands allow you to move up and down to individual lines, and along lines to particular characters.

After you position the cursor, you must issue a command to make the desired edit. The command you choose indicates how much text will be affected: a character, a word, a line, or a sentence.

Because the same keyboard is used to enter both text and commands, there must be some way to distinguish between the two. Some word-processing programs assume that you are entering text unless you specify otherwise; newly entered text either replaces existing text or pushes it over to make room for the new text. Commands are entered by pressing special keys on the keyboard, or by combining a standard key with a special key, such as the control key (CTRL).

Other programs assume that you are issuing commands; you must enter a command before you can type any text at all. There are advantages and disadvantages to each approach. Starting out in text mode is more intuitive to those coming from a typewriter, but may be slower for experienced writers, because all commands must be entered by special key combinations that are often hard to reach and slow down typing. (We’ll return to this topic when we discuss vi, a UNIX text editor.)

Far more significant than the style of command entry is the range and speed of commands. For example, though it is heaven for someone used to a typewriter to be able to delete a word and type in a replacement, it is even better to be able to issue a command that will replace every occurrence of that word in an entire document. And, after you start making such global changes, it is essential to have some way to undo them if you make a mistake.

A word processor that substitutes ease of learning for ease of use by having fewer commands will ultimately fail the serious writer, because the investment of time spent learning complex commands can easily be repaid when they simplify complex tasks.

And when you do issue a complex command, it is important that it works as quickly as possible, so that you aren’t left waiting while the computer grinds away. The extra seconds add up when you spend hours or days at the keyboard, and, once having been given a taste of freedom from drudgery, writers want as much freedom as they can get.

Text editors were developed before word processors (in the rapid evolution of computers). Many of them were originally designed for printing terminals, rather than for the CRT-based terminals used by word processors. These programs tend to have commands that work with text on a line-by-line basis. These commands are often more obscure than the equivalent office word-processing commands.

However, though the commands used by text editors are sometimes more difficult to learn, they are usually very effective. (The commands designed for use with slow paper terminals were often extraordinarily powerful, to make up for the limited capabilities of the input and output device.)

There are two basic kinds of text editors, line editors and screen editors, and both are available in UNIX. The difference is simple: line editors display one line at a time, and screen editors can display approximately 24 lines or a full screen.

The line editors in UNIX include ed, sed, and ex. Although these line editors are obsolete for general-purpose use by writers, there are applications at which they excel, as we will see in Chapters 7 and 12.

The most common screen editor in UNIX is vi. Learning vi or some other suitable editor is the first step in mastering the UNIX text-processing environment. Most of your time will be spent using the editor.

UNIX screen editors such as vi and emacs (another editor available on many UNIX systems) lack ease-of-learning features common in many word processors—there are no menus and only primitive on-line help screens, and the commands are often complex and nonintuitive—but they are powerful and fast. What’s more, UNIX line editors such as ex and sed give additional capabilities not found in word processors—the ability to write a script of editing commands that can be applied to multiple files. Such editing scripts open new ranges of capability to the writer.

▪ Document Formatting ▪

Text editing is wonderful, but the object of the writing process is to produce a printed document for others to read. And a printed document is more than words on paper; it is an arrangement of text on a page. For instance, the elements of a business letter are arranged in a consistent format, which helps the person reading the letter identify those elements. Reports and more complex documents, such as technical manuals or books, require even greater attention to formatting. The format of a document conveys how information is organized, assisting in the presentation of ideas to a reader.

Most word-processing programs have built-in formatting capabilities. Formatting commands are intermixed with editing commands, so that you can shape your document on the screen. Such formatting commands are simple extensions of those available to someone working with a typewriter. For example, an automatic centering command saves the trouble of manually counting characters to center a title or other text. There may also be such features as automatic pagination and printing of headers or footers.

Text editors, by contrast, usually have few formatting capabilities. Because they were designed for entering programs, their formatting capabilities tend to be oriented toward the formats required by one or more programming languages.

Even programmers write reports, however. Especially at AT&T (where UNIX was developed), there was a great emphasis on document preparation tools to help the programmers and scientists of Bell Labs produce research reports, manuals, and other documents associated with their development work.

Word processing, with its emphasis on easy-to-use programs with simple on-screen formatting, was in its infancy. Computerized phototypesetting, on the other hand, was already a developed art. Until quite recently, it was not possible to represent on a video screen the variable type styles and sizes used in typeset documents. As a result, phototypesetting has long used a markup system that indicates formatting instructions with special codes. These formatting instructions to the computerized typesetter are often direct descendants of the instructions that were formerly given to a human typesetter—center the next line, indent five spaces, boldface this heading.

The text formatter most commonly used with the UNIX system is called nroff. To use it, you must intersperse formatting instructions (usually one- or two-letter codes preceded by a period) within your text, then pass the file through the formatter. The nroff program interprets the formatting codes and reformats the document “on the fly” while passing it on to the printer. The nroff formatter prepares documents for printing on line printers, dot-matrix printers, and letter-quality printers. Another program called troff uses an extended version of the same markup language used by nroff, but prepares documents for printing on laser printers and typesetters. We’ll talk more about printing in a moment.

Although formatting with a markup language may seem to be a far inferior system to the “what you see is what you get” (wysiwyg) approach of most office word-processing programs, it actually has many advantages.

First, unless you are using a very sophisticated computer, with very sophisticated software (what has come to be called an electronic publishing system, rather than a mere word processor), it is not possible to display everything on the screen just as it will appear on the printed page. For example, the screen may not be able to represent boldfacing or underlining except with special formatting codes. WordStar, one of the grandfathers of word-processing programs for personal computers, represents underlining by surrounding the word or words to be underlined with the special control character ^S (the character generated by holding down the control key while typing the letter S). For example, the following title line would be underlined when the document is printed:

^Sword Processing with WordStar^S

Is this really superior to the following nroff construct?

.ul

Text Processing with vi and nroff

It is perhaps unfair to pick on WordStar, an older word-processing program, but very few word-processing programs can complete the illusion that what you see on the screen is what you will get on paper. There is usually some mix of control codes with on-screen formatting. More to the point, though, is the fact that most word processors are oriented toward the production of short documents. When you get beyond a letter, memo, or report, you start to understand that there is more to formatting than meets the eye.

Although “what you see is what you get” is fine for laying out a single page, it is much harder to enforce consistency across a large document. The design of a large document is often determined before writing is begun, just as a set of plans for a house are drawn up before anyone starts construction. The design is a plan for organizing a document, arranging various parts so that the same types of material are handled in the same way.

The parts of a document might be chapters, sections, or subsections. For instance, a technical manual is often organized into chapters and appendices. Within each chapter, there might be numbered sections that are further divided into three or four levels of subsections.

Document design seeks to accomplish across the entire document what is accomplished by the table of contents of a book. It presents the structure of a document and helps the reader locate information.

Each of the parts must be clearly identified. The design specifies how they will look, trying to achieve consistency throughout the document. The strategy might specify that major section headings will be all uppercase, underlined, with three blank lines above and two below, and secondary headings will be in uppercase and lowercase, underlined, with two blank lines above and one below.

If you have ever tried to format a large document using a word processor, you have probably found it difficult to enforce consistency in such formatting details as these. By contrast, a markup language—especially one like nroff that allows you to define repeated command sequences, or macros—makes it easy: the style of a heading is defined once, and a code used to reference it. For example, a top-level heading might be specified by the code .H1, and a secondary heading by .H2.

Even more significantly, if you later decide to change the design, you simply change the definition of the relevant design elements. If you have used a word processor to format the document as it was written, it is usually a painful task to go back and change the format.

Some word-processing programs, such as Microsoft WORD, include features for defining global document formats, but these features are not as widespread as they are in markup systems.

▪ Printing ▪

The formatting capabilities of a word-processing system are limited by what can be output on a printer. For example, some printers cannot backspace and therefore cannot underline. For this discussion, we are considering four different classes of printers: dot matrix, letter quality, phototypesetter, and laser.

A dot-matrix printer composes characters as a series of dots. It is usually suitable for preparing interoffice memos and obtaining fast printouts of large files.

This paragraph was printed with a dot-matrix printer. It uses a print

head containing 9 pins, which are adjusted to produce the shape of each

character. More sophicated dot-matrix printers have print heads

containing up to 24 pins. The greater the number of pins, the finer

the dots that are printed, and the more possible it is to fool the eye

into thinking it sees a solid character. Dot matrix printers are also

capable of printing out graphic displays.

A letter-quality printer is more expensive and slower. Its printing mechanism operates like a typewriter and achieves a similar result.

This paragraph was printed with a letter-

quality printer. It is essentially a

computer-controlled typewriter and, like a

typewriter, uses a print ball or wheel

containing fully formed characters.

A letter-quality printer produces clearer, easier-to-read copy than a dot-matrix printer. Letter-quality printers are generally used in offices for formal correspondence as well as for the final drafts of proposals and reports.

Until very recently, documents that needed a higher quality of printing than that available with letter-quality printers were sent out for typesetting. Even if draft copy was word-processed, the material was often re-entered by the typesetter, although many typesetting companies can read the files created by popular word-processing programs and use them as a starting point for typesetting.

This paragraph, like the rest of this book, was phototypeset. In photo-typesetting, a photographic technique is used to print characters on film or photographic paper. There is a wide choice of type styles, and the characters are much more finely formed that those produced by a letter-quality printer. Characters are produced by an arrangement of tiny dots, much like a dot-matrix printer—but there are over 1000 dots per inch.

There are several major advantages to typesetting. The high resolution allows for the design of aesthetically pleasing type. The shape of the characters is much finer. In addition, where dot-matrix and letter-quality type is usually constant width (narrow letters like i take up the same amount of space as wide ones like m), typesetters use variable-width type, in which narrow letters take up less space than wide ones. In addition, it’s possible to mix styles (for example, bold and italic) and sizes of type on the same page.

Most typesetting equipment uses a markup language rather than a wysiwyg approach to specify point sizes, type styles, leading, and so on. Until recently, the technology didn’t even exist to represent on a screen the variable-width typefaces that appear in published books and magazines.

AT&T, a company with its own extensive internal publishing operation, developed its own typesetting markup language and typesetting program—a sister to nroff called troff (typesetter-roff). Although troff extends the capabilities of nroff in significant ways, it is almost totally compatible with it.

Until recently, unless you had access to a typesetter, you didn’t have much use for troff. The development of low-cost laser printers that can produce near typeset-quality output at a fraction of the cost has changed all that.

This paragraph was produced on a laser printer. Laser printers produce high-resolution characters—300 to 500 dots per inch—though they are not quite as finely formed as phototypeset characters. Laser printers are not only cheaper to purchase than phototypesetters, they also print on plain paper, just like Xerox machines, and are therefore much cheaper to operate. However, as is always the case with computers, you need the proper software to take advantage of improved hardware capabilities.

Word-processing software (particularly that developed for the Apple Macintosh, which has a high-resolution graphics screen capable of representing variable type fonts) is beginning to tap the capabilities of laser printers. However, most of the microcomputer-based packages still have many limitations. Nonetheless, a markup language such as that provided by troff still provides the easiest and lowest-cost access to the world of electronic publishing for many types of documents.

The point made previously, that markup languages are preferable to wysiwyg systems for large documents, is especially true when you begin to use variable size fonts, leading, and other advanced formatting features. It is easy to lose track of the overall format of your document and difficult to make overall changes after your formatted text is in place. Only the most expensive electronic publishing systems (most of them based on advanced UNIX workstations) give you both the capability to see what you will get on the screen and the ability to define and easily change overall document formats.

▪ Other UNIX Text-Processing Tools ▪

Document editing and formatting are the most important parts of text processing, but they are not the whole story. For instance, in writing many types of documents, such as technical manuals, the writer rarely starts from scratch. Something is already written, whether it be a first draft written by someone else, a product specification, or an outdated version of a manual. It would be useful to get a copy of that material to work with. If that material was produced with a word processor or has been entered on another system, UNIX’s communications facilities can transfer the file from the remote system to your own.

Then you can use a number of custom-made programs to search through and extract useful information. Word-processing programs often store text in files with different internal formats. UNIX provides a number of useful analysis and translation tools that can help decipher files with nonstandard formats. Other tools allow you to “cut and paste” portions of a document into the one you are writing.

As the document is being written, there are programs to check spelling, style, and diction. The reports produced by those programs can help you see if there is any detectable pattern in syntax or structure that might make a document more difficult for the user than it needs to be.

Although many documents are written once and published or filed, there is also a large class of documents (manuals in particular) that are revised again and again. Documents such as these require special tools for managing revisions. UNIX program development tools such as SCCS (Source Code Control System) and diff can be used by writers to compare past versions with the current draft and print out reports of the differences, or generate printed copies with change bars in the margin marking the differences.

In addition to all of the individual tools it provides, UNIX is a particularly fertile environment for writers who aren’t afraid of computers, because it is easy to write command files, or shell scripts, that combine individual programs into more complex tools to meet your specific needs. For example, automatic index generation is a complex task that is not handled by any of the standard UNIX text-processing tools. We will show you ways to perform this and other tasks by applying the tools available in the UNIX environment and a little ingenuity.

We have two different objectives in this book. The first objective is that you learn to use many of the tools available on most UNIX systems. The second objective is that you develop an understanding of how these different tools can work together in a document preparation system. We’re not just presenting a UNIX user’s manual, but suggesting applications for which the various programs can be used.

To take full advantage of the UNIX text-processing environment, you must do more than just learn a few programs. For the writer, the job includes establishing standards and conventions about how documents will be stored, in what format they should appear in print, and what kinds of programs are needed to help this process take place efficiently with the use of a computer. Another way of looking at it is that you have to make certain choices prior to beginning a project. We want to encourage you to make your own choices, set your own standards, and realize the many possibilities that are open to a diligent and creative person.

In the past, many of the steps in creating a finished book were out of the hands of the writer. Proofreaders and copyeditors went over the text for spelling and grammatical errors. It was generally the printer who did the typesetting (a service usually paid by the publisher). At the print shop, a typesetter (a person) retyped the text and specified the font sizes and styles. A graphic artist, performing layout and pasteup, made many of the decisions about the appearance of the printed page.

Although producing a high-quality book can still involve many people, UNIX provides the tools that allow a writer to control the process from start to finish. An analogy is the difference between an assembly worker on a production line who views only one step in the process and a craftsman who guides the product from beginning to end. The craftsman has his own system of putting together a product, whereas the assembly worker has the system imposed upon him.

After you are acquainted with the basic tools available in UNIX and have spent some time using them, you can design additional tools to perform work that you think is necessary and helpful. To create these tools, you will write shell scripts that use the resources of UNIX in special ways. We think there is a certain satisfaction that comes with accomplishing such tasks by computer. It seems to us to reward careful thought.

What programming means to us is that when we confront a problem that normally submits only to tedium or brute force, we think of a way to get the computer to solve the problem. Doing this often means looking at the problem in a more general way and solving it in a way that can be applied again and again.

One of the most important books on UNIX is The UNIX Programming Environment by Brian W. Kernighan and Rob Pike. They write that what makes UNIX effective “is an approach to programming, a philosophy of using the computer.” At the heart of this philosophy “is the idea that the power of a system comes more from the relationships among programs than from the programs themselves.”

When we talk about building a document preparation system, it is this philosophy that we are trying to apply. As a consequence, this is a system that has great flexibility and gives the builders a feeling of breaking new ground. The UNIX text-processing environment is a system that can be tailored to the specific tasks you want to accomplish. In many instances, it can let you do just what a word processor does. In many more instances, it lets you use more of the computer to do things that a word processor either can’t do or can’t do very well.

*Some editors, such as emacs, can split the terminal screen into multiple windows. In addition, many high-powered UNIX workstations with large bit-mapped screens have their own windowing software that allows multiple programs to be run simultaneously in separate windows. For purposes of this book, we assume you are using the vi editor and an alphanumeric terminal with only a single window.

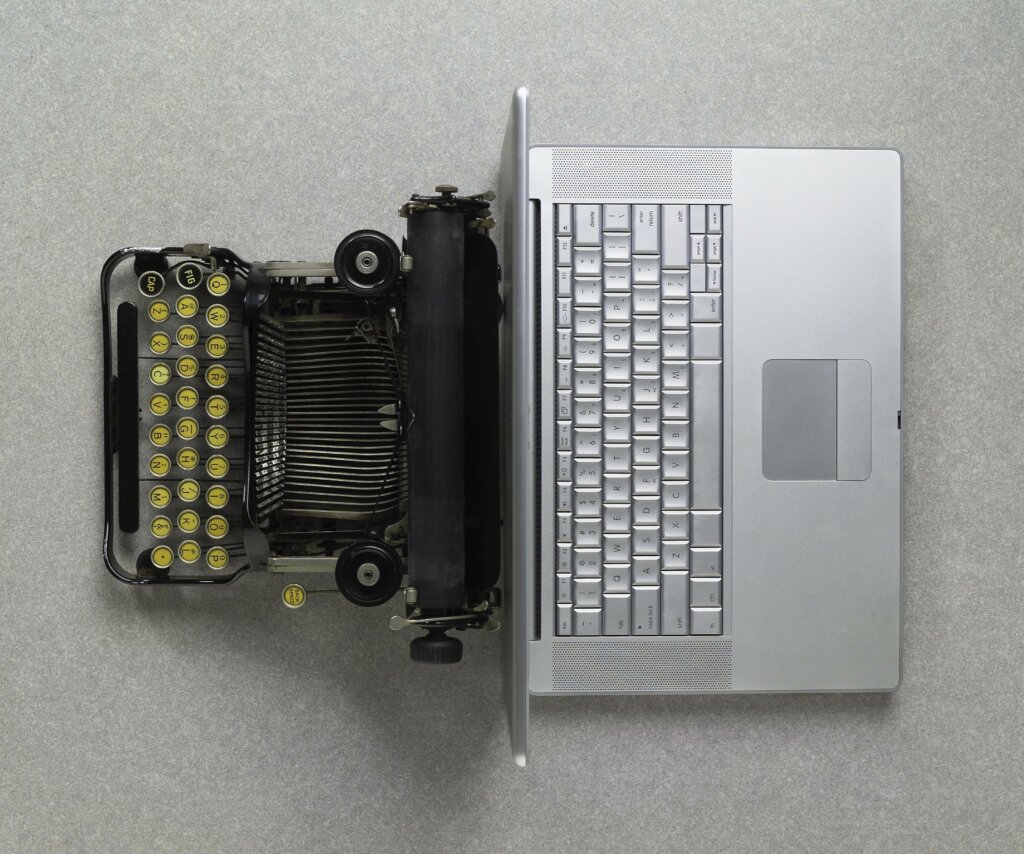

Both typewriters and word processors create texts with characteristics of print (as opposed to handwriting). They also share some mechanics for doing so, such as a similar keyboard with “return” and “enter” keys, shift keys, a space bar and, ultimately, some error correction.

The similarities and differences between typewriters and word processors can be identified through a brief history of the typewriter. Prior to the invention of the typewriter, people had to develop clear handwriting for the purpose of creating important documents. The Declaration of Independence, for example, is handwritten, as is the U.S. Constitution. During the 19th century, businesses proliferated with the Industrial Revolution, and the typewriter became a desirable invention. While many people believe that the QWERTY keyboard was developed to get around the problems of a manual typewriter, it was created to help transcribers of Morse code. Typewriters even had some basic error correction features such as on the IBM Selectric where bad text could be overstruck with a special masking ribbon. Word processors began with typewriter features, such as the purpose of the machine and much of the layout of the keyboard. Yet word processors went beyond the basic form and function of a typewriter. For example, a text in a word processor can be edited and corrected in a much more efficient way than with a typewriter. Further, a modern word processor can handle advanced tasks such as the creation of a table of contents from a document. The word processor, then, derives from the typewriter and because of this, the two share some characteristics.

MORE FROM REFERENCE.COM

Posted by John in Uncategorized.

trackback

Differences and Similarities between Type Writers and Word Processors

By John M. Bowling

What do you use to place your thoughts on paper? Do the differences between word processors and type writers ever cross your mind? There are many differences between word processors and type writers. Likewise, type writers were very popular during the early and mid twentieth century. They were used by many scholars. Today, word processors (such as Microsoft Word) are used in many colleges, schools, and businesses. But today, you will learn the many differences and similarities between the two.

Thereafter, there are many similarities between word processors and type writers. Both are able to transform thoughts onto paper. In result, it creates a legible document. Moreover, both have a full key board suitable for typing. This includes all the main keys and letters of the alphabet. One unique feature on both is that they are able to center the text. This feature solved a problem when people wrote essays by hand. After that, you can’t forget one of the more important features. Both word processors and type writers can print out a quality document on paper. In result, you can turn your work in to your desired place (such as turning it in to a teacher or professor).

In conclusion, type writers and word processors are great inventions of the century. You can’t forget word processors were inspired by typewriters. In result to that, we never would have had word processors without type writers. It is all like a puzzle, humanity advances over time with each great invention inspired by another. In this case, both inventions brought us a little closer to the real future.

Updated: 07/06/2021 by

Sometimes abbreviated as WP, a word processor is a software program capable of creating, storing, and printing typed documents. Today, the word processor is one of the most frequently used software programs on a computer, with Microsoft Word being a popular choice.

Word processors can create multiple types of files, including text files (.txt), rich text files (.rtf), HTML files (.htm & .html), and Word files (.doc & .docx). Some word processors can also be used to create XML files (.xml).

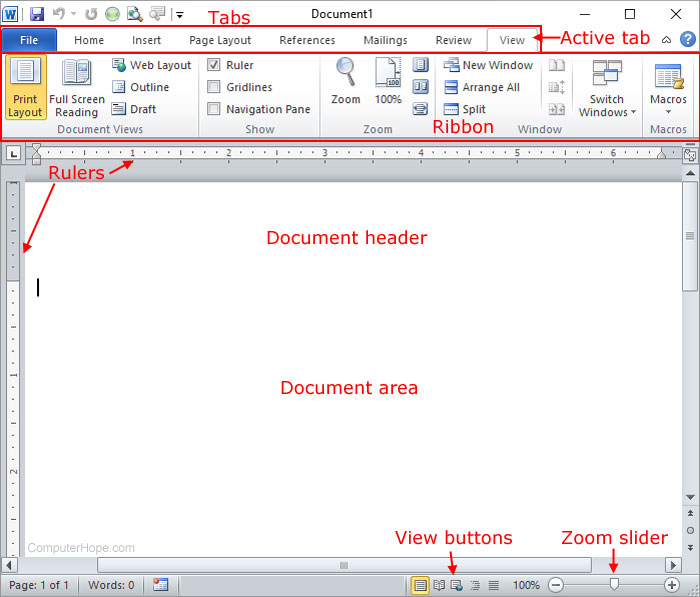

Overview of Word

In a word processor, you are presented with a blank white sheet as shown below. The text is added to the document area and after it has been inserted formatted or adjusted to your preference. Below is an example of a blank Microsoft Word window with areas of the window highlighted.

Features of a word processor

Unlike a basic plaintext editor, a word processor offers several additional features that can give your document or other text a more professional appearance. Below is a listing of popular features of a word processor.

Note

Some more advanced text editors can perform some of these functions.

- Text formatting — Changing the font, font size, font color, bold, italicizing, underline, etc.

- Copying, cutting, and pasting — Once text is entered into a document, it can be copied or cut and pasted in the current document or another document.

- Multimedia — Insert clip art, charts, images, pictures, and video into a document.

- Spelling and Grammar — Checks for spelling and grammar errors in a document.

- Adjust the layout — Capable of modifying the margins, size, and layout of a document.

- Find — Word processors give you the ability to quickly find any word or text in any size of the document.

- Search and Replace — You can use the Search and Replace feature to replace any text throughout a document.

- Indentation and lists — Set and format tabs, bullet lists, and number lists.

- Insert tables — Add tables to a document.

- Word wrap — Word processors can detect the edges of a page or container and automatically wrap the text using word wrap.

- Header and footer — Being able to adjust and change text in the header and footer of a document.

- Thesaurus — Look up alternatives to a word without leaving the program.

- Multiple windows — While working on a document, you can have additional windows with other documents for comparison or move text between documents.

- AutoCorrect — Automatically correct common errors (e.g., typing «teh» and having it autocorrected to «the»).

- Mailers and labels — Create mailers or print labels.

- Import data — Import and format data from CSV, database, or another source.

- Headers and footers — The headers and footers of a document can be customized to contain page numbers, dates, footnotes, or text for all pages or specific pages of the document.

- Merge — Word processors allow data from other documents and files to be automatically merged into a new document. For example, you can mail merge names into a letter.

- Macros — Setup macros to perform common tasks.

- Collaboration — More modern word processors help multiple people work on the same document at the same time.

Examples and top uses of a word processor

A word processor is one of the most used computer programs because of its versatility in creating a document. Below is a list of the top examples of how you could use a word processor.

- Book — Write a book.

- Document — Any text document that requires formatting.

- Help documentation — Support documentation for a product or service.

- Journal — Keep a digital version of your daily, weekly, or monthly journal.

- Letter — Write a letter to one or more people. Mail merge could also be used to automatically fill in the name, address, and other fields of the letter.

- Marketing plan — An overview of a plan to help market a new product or service.

- Memo — Create a memo for employees.

- Report — A status report or book report.

- Résumé — Create or maintain your résumé.

Examples of word processor programs

Although Microsoft Word is popular, there are other word processor programs. Below is a list of some popular word processors in alphabetical order.

- Abiword.

- Apple iWork — Pages.

- Apple TextEdit — Apple macOS included word processor.

- Corel WordPerfect.

- Dropbox Paper (online and free).

- Google Docs (online and free).

- LibreOffice -> Writer (free).

- Microsoft Office -> Microsoft Word.

- Microsoft WordPad.

- Microsoft Works (discontinued).

- SoftMaker FreeOffice -> TextMaker (free).

- OpenOffice -> Writer (free).

- SSuite -> WordGraph (free).

- Sun StarOffice (discontinued).

- Textilus (iPad and iPhone).

- Kingsoft WPS Office -> Writer (free).

Word processor advantages over a typewriter

See our typewriter page for a listing of advantages a computer with a word processor has over a typewriter.

Computer acronyms, Doc, Microsoft Word, Software terms, Untitled, Word processing, Word processor terms, WordStar, Write

This article is about stand-alone word processing machines. For the computer program, see Word processor program. For the general concept, see Word processor.

A word processor is an electronic device (later a computer software application) for text, composing, editing, formatting, and printing.

A Xerox 6016 Memorywriter Word Processor

The word processor was a stand-alone office machine developed in the 1960s, combining the keyboard text-entry and printing functions of an electric typewriter with a recording unit, either tape or floppy disk (as used by the Wang machine) with a simple dedicated computer processor for the editing of text.[1] Although features and designs varied among manufacturers and models, and new features were added as technology advanced, the first word processors typically featured a monochrome display and the ability to save documents on memory cards or diskettes. Later models introduced innovations such as spell-checking programs, and improved formatting options.

As the more versatile combination of personal computers and printers became commonplace, and computer software applications for word processing became popular, most business machine companies stopped manufacturing dedicated word processor machines. As of 2009 there were only two U.S. companies, Classic and AlphaSmart, which still made them.[2][needs update] Many older machines, however, remain in use. Since 2009, Sentinel has offered a machine described as a «word processor», but it is more accurately a highly specialised microcomputer used for accounting and publishing.[3]

Word processing was one of the earliest applications for the personal computer in office productivity, and was the most widely used application on personal computers until the World Wide Web rose to prominence in the mid-1990s.

Although the early word processors evolved to use tag-based markup for document formatting, most modern word processors take advantage of a graphical user interface providing some form of what-you-see-is-what-you-get («WYSIWYG») editing. Most are powerful systems consisting of one or more programs that can produce a combination of images, graphics and text, the latter handled with type-setting capability. Typical features of a modern word processor include multiple font sets, spell checking, grammar checking, a built-in thesaurus, automatic text correction, web integration, HTML conversion, pre-formatted publication projects such as newsletters and to-do lists, and much more.

Microsoft Word is the most widely used word processing software according to a user tracking system built into the software.[citation needed] Microsoft estimates that roughly half a billion people use the Microsoft Office suite,[4] which includes Word. Many other word processing applications exist, including WordPerfect (which dominated the market from the mid-1980s to early-1990s on computers running Microsoft’s MS-DOS operating system, and still (2014) is favored for legal applications), Apple’s Pages application, and open source applications such as OpenOffice.org Writer, LibreOffice Writer, AbiWord, KWord, and LyX. Web-based word processors such as Office Online or Google Docs are a relatively new category.

CharacteristicsEdit

Word processors evolved dramatically once they became software programs rather than dedicated machines. They can usefully be distinguished from text editors, the category of software they evolved from.[5][6]

A text editor is a program that is used for typing, copying, pasting, and printing text (a single character, or strings of characters). Text editors do not format lines or pages. (There are extensions of text editors which can perform formatting of lines and pages: batch document processing systems, starting with TJ-2 and RUNOFF and still available in such systems as LaTeX and Ghostscript, as well as programs that implement the paged-media extensions to HTML and CSS). Text editors are now used mainly by programmers, website designers, computer system administrators, and, in the case of LaTeX, by mathematicians and scientists (for complex formulas and for citations in rare languages). They are also useful when fast startup times, small file sizes, editing speed, and simplicity of operation are valued, and when formatting is unimportant. Due to their use in managing complex software projects, text editors can sometimes provide better facilities for managing large writing projects than a word processor.[7]

Word processing added to the text editor the ability to control type style and size, to manage lines (word wrap), to format documents into pages, and to number pages. Functions now taken for granted were added incrementally, sometimes by purchase of independent providers of add-on programs. Spell checking, grammar checking and mail merge were some of the most popular add-ons for early word processors. Word processors are also capable of hyphenation, and the management and correct positioning of footnotes and endnotes.

More advanced features found in recent word processors include:

- Collaborative editing, allowing multiple users to work on the same document.

- Indexing assistance. (True indexing, as performed by a professional human indexer, is far beyond current technology, for the same reasons that fully automated, literary-quality machine translation is.)

- Creation of tables of contents.

- Management, editing, and positioning of visual material (illustrations, diagrams), and sometimes sound files.

- Automatically managed (updated) cross-references to pages or notes.

- Version control of a document, permitting reconstruction of its evolution.

- Non-printing comments and annotations.

- Generation of document statistics (characters, words, readability level, time spent editing by each user).

- «Styles», which automate consistent formatting of text body, titles, subtitles, highlighted text, and so on.

Later desktop publishing programs were specifically designed with elaborate pre-formatted layouts for publication, offering only limited options for changing the layout, while allowing users to import text that was written using a text editor or word processor, or type the text in themselves.

Typical usageEdit

Word processors have a variety of uses and applications within the business world, home, education, journalism, publishing, and the literary arts.

Use in businessEdit

Within the business world, word processors are extremely useful tools. Some typical uses include: creating legal documents, company reports, publications for clients, letters, and internal memos. Businesses tend to have their own format and style for any of these, and additions such as company letterhead. Thus, modern word processors with layout editing and similar capabilities find widespread use in most business.

Use in homeEdit

While many homes have a word processor on their computers, word processing in the home tends to be educational, planning or business related, dealing with school assignments or work being completed at home. Occasionally word processors are used for recreational purposes, e.g. writing short stories, poems or personal correspondence. Some use word processors to create résumés and greeting cards, but many of these home publishing processes have been taken over by web apps or desktop publishing programs specifically oriented toward home uses. The rise of email and social networks has also reduced the home role of the word processor as uses that formerly required printed output can now be done entirely online.

HistoryEdit

Word processors are descended from the Friden Flexowriter, which had two punched tape stations and permitted switching from one to the other (thus enabling what was called the «chain» or «form letter», one tape containing names and addresses, and the other the body of the letter to be sent). It did not wrap words, which was begun by IBM’s Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter (later, Magnetic Card Selectric Typewriter).

IBM SelectricEdit

Expensive Typewriter, written and improved between 1961 and 1962 by Steve Piner and L. Peter Deutsch, was a text editing program that ran on a DEC PDP-1 computer at MIT. Since it could drive an IBM Selectric typewriter (a letter-quality printer), it may be considered the first-word processing program, but the term word processing itself was only introduced, by IBM’s Böblingen Laboratory in the late 1960s.[citation needed]

In 1969, two software based text editing products (Astrotype and Astrocomp) were developed and marketed by Information Control Systems (Ann Arbor Michigan).[8][9][10] Both products used the Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-8 mini computer, DECtape (4” reel) randomly accessible tape drives, and a modified version of the IBM Selectric typewriter (the IBM 2741 Terminal). These 1969 products preceded CRT display-based word processors. Text editing was done using a line numbering system viewed on a paper copy inserted in the Selectric typewriter.

Evelyn Berezin invented a Selectric-based word processor in 1969, and founded the Redactron Corporation to market the $8,000 machine.[11] Redactron was sold to Burroughs Corporation in 1976, where the Redactron-II and -III were sold both as standalone units and as peripherals to the company’s mainframe computers.[12]

By 1971 word processing was recognized by the New York Times as a «buzz word».[13] A 1974 Times article referred to «the brave new world of Word Processing or W/P. That’s International Business Machines talk … I.B.M. introduced W/P about five years ago for its Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter and other electronic razzle-dazzle.»[14]

IBM defined the term in a broad and vague way as «the combination of people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed communications,» and originally used it to include dictating machines and ordinary, manually operated Selectric typewriters.[15] By the early seventies, however, the term was generally understood to mean semiautomated typewriters affording at least some form of editing and correction, and the ability to produce perfect «originals». Thus, the Times headlined a 1974 Xerox product as a «speedier electronic typewriter», but went on to describe the product, which had no screen,[16] as «a word processor rather than strictly a typewriter, in that it stores copy on magnetic tape or magnetic cards for retyping, corrections, and subsequent printout».[17]

Mainframe systemsEdit

In the late 1960s IBM provided a program called FORMAT for generating printed documents on any computer capable of running Fortran IV. Written by Gerald M. Berns, FORMAT was described in his paper «Description of FORMAT, a Text-Processing Program» (Communications of the ACM, Volume 12, Number 3, March, 1969) as «a production program which facilitates the editing and printing of ‘finished’ documents directly on the printer of a relatively small (64k) computer system. It features good performance, totally free-form input, very flexible formatting capabilities including up to eight columns per page, automatic capitalization, aids for index construction, and a minimum of nontext [control elements] items.» Input was normally on punched cards or magnetic tape, with up to 80capital letters and non-alphabetic characters per card. The limited typographical controls available were implemented by control sequences; for example, letters were automatically converted to lower case unless they followed a full stop, that is, the «period» character. Output could be printed on a typical line printer in all-capitals — or in upper and lower case using a special («TN») printer chain — or could be punched as a paper tape which could be printed, in better than line printer quality, on a Flexowriter. A workalike program with some improvements, DORMAT, was developed and used at University College London.[citation needed]

Electromechanical paper-tape-based equipment such as the Friden Flexowriter had long been available; the Flexowriter allowed for operations such as repetitive typing of form letters (with a pause for the operator to manually type in the variable information),[18] and when equipped with an auxiliary reader, could perform an early version of «mail merge». Circa 1970 it began to be feasible to apply electronic computers to office automation tasks. IBM’s Mag Tape Selectric Typewriter (MT/ST) and later Mag Card Selectric (MCST) were early devices of this kind, which allowed editing, simple revision, and repetitive typing, with a one-line display for editing single lines.[19] The first novel to be written on a word processor, the IBM MT/ST, was Len Deighton’s Bomber, published in 1970.[20]

Effect on office administrationEdit

The New York Times, reporting on a 1971 business equipment trade show, said

- The «buzz word» for this year’s show was «word processing», or the use of electronic equipment, such as typewriters; procedures and trained personnel to maximize office efficiency. At the IBM exhibition a girl typed on an electronic typewriter. The copy was received on a magnetic tape cassette which accepted corrections, deletions, and additions and then produced a perfect letter for the boss’s signature …[13]

In 1971, a third of all working women in the United States were secretaries, and they could see that word processing would affect their careers. Some manufacturers, according to a Times article, urged that «the concept of ‘word processing’ could be the answer to Women’s Lib advocates’ prayers. Word processing will replace the ‘traditional’ secretary and give women new administrative roles in business and industry.»[13]

The 1970s word processing concept did not refer merely to equipment, but, explicitly, to the use of equipment for «breaking down secretarial labor into distinct components, with some staff members handling typing exclusively while others supply administrative support. A typical operation would leave most executives without private secretaries. Instead one secretary would perform various administrative tasks for three or more secretaries.»[21] A 1971 article said that «Some [secretaries] see W/P as a career ladder into management; others see it as a dead-end into the automated ghetto; others predict it will lead straight to the picket line.» The National Secretaries Association, which defined secretaries as people who «can assume responsibility without direct supervision», feared that W/P would transform secretaries into «space-age typing pools». The article considered only the organizational changes resulting from secretaries operating word processors rather than typewriters; the possibility that word processors might result in managers creating documents without the intervention of secretaries was not considered—not surprising in an era when few managers, but most secretaries, possessed keyboarding skills.[14]

Dedicated modelsEdit

In 1972, Stephen Bernard Dorsey, Founder and President of Canadian company Automatic Electronic Systems (AES), introduced the world’s first programmable word processor with a video screen. The real breakthrough by Dorsey’s AES team was that their machine stored the operator’s texts on magnetic disks. Texts could be retrieved from the disks simply by entering their names at the keyboard. More importantly, a text could be edited, for instance a paragraph moved to a new place, or a spelling error corrected, and these changes were recorded on the magnetic disk.

The AES machine was actually a sophisticated computer that could be reprogrammed by changing the instructions contained within a few chips.[22][23]

In 1975, Dorsey started Micom Data Systems and introduced the Micom 2000 word processor. The Micom 2000 improved on the AES design by using the Intel 8080 single-chip microprocessor, which made the word processor smaller, less costly to build and supported multiple languages.[24]

Around this time, DeltaData and Wang word processors also appeared, again with a video screen and a magnetic storage disk.

The competitive edge for Dorsey’s Micom 2000 was that, unlike many other machines, it was truly programmable. The Micom machine countered the problem of obsolescence by avoiding the limitations of a hard-wired system of program storage. The Micom 2000 utilized RAM, which was mass-produced and totally programmable.[25] The Micom 2000 was said to be a year ahead of its time when it was introduced into a marketplace that represented some pretty serious competition such as IBM, Xerox and Wang Laboratories.[26]

In 1978, Micom partnered with Dutch multinational Philips and Dorsey grew Micom’s sales position to number three among major word processor manufacturers, behind only IBM and Wang.[27]

Software modelsEdit

In the early 1970s, computer scientist Harold Koplow was hired by Wang Laboratories to program calculators. One of his programs permitted a Wang calculator to interface with an IBM Selectric typewriter, which was at the time used to calculate and print the paperwork for auto sales.

In 1974, Koplow’s interface program was developed into the Wang 1200 Word Processor, an IBM Selectric-based text-storage device. The operator of this machine typed text on a conventional IBM Selectric; when the Return key was pressed, the line of text was stored on a cassette tape. One cassette held roughly 20 pages of text, and could be «played back» (i.e., the text retrieved) by printing the contents on continuous-form paper in the 1200 typewriter’s «print» mode. The stored text could also be edited, using keys on a simple, six-key array. Basic editing functions included Insert, Delete, Skip (character, line), and so on.

The labor and cost savings of this device were immediate, and remarkable: pages of text no longer had to be retyped to correct simple errors, and projects could be worked on, stored, and then retrieved for use later on. The rudimentary Wang 1200 machine was the precursor of the Wang Office Information System (OIS), introduced in 1976. It was a true office machine, affordable by organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily learned and operated by secretarial staff.

The Wang was not the first CRT-based machine nor were all of its innovations unique to Wang. In the early 1970s Linolex, Lexitron and Vydec introduced pioneering word-processing systems with CRT display editing. A Canadian electronics company, Automatic Electronic Systems, had introduced a product in 1972, but went into receivership a year later. In 1976, refinanced by the Canada Development Corporation, it returned to operation as AES Data, and went on to successfully market its brand of word processors worldwide until its demise in the mid-1980s. Its first office product, the AES-90,[28] combined for the first time a CRT-screen, a floppy-disk and a microprocessor,[22][23] that is, the very same winning combination that would be used by IBM for its PC seven years later.[citation needed] The AES-90 software was able to handle French and English typing from the start, displaying and printing the texts side-by-side, a Canadian government requirement. The first eight units were delivered to the office of the then Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, in February 1974.[citation needed]

Despite these predecessors, Wang’s product was a standout, and by 1978 it had sold more of these systems than any other vendor.[29]

The phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based machines similar to the AES 90. Numerous machines of this kind emerged, typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as IBM, Lanier (marketing AES Data machines, re-badged), CPT, and NBI.[30]

All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, priced around $10,000. Cheap general-purpose computers were still for hobbyists.

Some of the earliest CRT-based machines used cassette tapes for removable-memory storage until floppy diskettes became available for this purpose — first the 8-inch floppy, then the 5¼-inch (drives by Shugart Associates and diskettes by Dysan).

Printing of documents was initially accomplished using IBM Selectric typewriters modified for ASCII-character input. These were later replaced by application-specific daisy wheel printers, first developed by Diablo, which became a Xerox company, and later by Qume. For quicker «draft» printing, dot-matrix line printers were optional alternatives with some word processors.

WYSIWYG modelsEdit

Examples of standalone word processor typefaces c. 1980–1981

Brother WP-1400D editing electronic typewriter (1994)

Electric Pencil, released in December 1976, was the first word processor software for microcomputers.[31][32][33][34][35] Software-based word processors running on general-purpose personal computers gradually displaced dedicated word processors, and the term came to refer to software rather than hardware. Some programs were modeled after particular dedicated WP hardware. MultiMate, for example, was written for an insurance company that had hundreds of typists using Wang systems, and spread from there to other Wang customers. To adapt to the smaller, more generic PC keyboard, MultiMate used stick-on labels and a large plastic clip-on template to remind users of its dozens of Wang-like functions, using the shift, alt and ctrl keys with the 10 IBM function keys and many of the alphabet keys.

Other early word-processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys labelled «copy» or «bold». (In fact, many early PCs lacked cursor keys; WordStar famously used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond» for cursor navigation, and modern vi-like editors encourage use of hjkl for navigation.) However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as VisiCalc, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software soon became serious competition for the dedicated machines. Word processing became the most popular use for personal computers, and unlike the spreadsheet (dominated by Lotus 1-2-3) and database (dBase) markets, WordPerfect, XyWrite, Microsoft Word, pfs:Write, and dozens of other word processing software brands competed in the 1980s; PC Magazine reviewed 57 different programs in one January 1986 issue.[32] Development of higher-resolution monitors allowed them to provide limited WYSIWYG—What You See Is What You Get, to the extent that typographical features like bold and italics, indentation, justification and margins were approximated on screen.

The mid-to-late 1980s saw the spread of laser printers, a «typographic» approach to word processing, and of true WYSIWYG bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), PostScript, and graphical user interfaces (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor which was commercialised in the Xerox Star product range). Standalone word processors adapted by getting smaller and replacing their CRTs with small character-oriented LCD displays. Some models also had computer-like features such as floppy disk drives and the ability to output to an external printer. They also got a name change, now being called «electronic typewriters» and typically occupying a lower end of the market, selling for under US$200.

During the late 1980s and into the 1990s the predominant word processing program was WordPerfect.[36] It had more than 50% of the worldwide market as late as 1995, but by 2000 Microsoft Word had up to 95% market share.[37]

MacWrite, Microsoft Word, and other word processing programs for the bit-mapped Apple Macintosh screen, introduced in 1984, were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people until the introduction of Microsoft Windows. Dedicated word processors eventually became museum pieces.

See alsoEdit

- Amstrad PCW

- Authoring systems

- Canon Cat

- Comparison of word processors

- Content management system

- CPT Word Processors

- Document collaboration

- List of word processors

- IBM MT/ST

- Microwriter

- Office suite

- TeX

- Typography

LiteratureEdit

- Matthew G. Kirschenbaum Track Changes — A Literary History of Word Processing Harvard University Press 2016 ISBN 9780674417076

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «TECHNOWRITERS» Popular Mechanics, June 1989, pp. 71-73.

- ^ Mark Newhall, Farm Show

- ^ StarLux Illumination catalog

- ^ «Microsoft Office Is Right at Home». Microsoft. January 8, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ «InfoWorld Jan 1 1990». January 1990.

- ^ Reilly, Edwin D. (2003). Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781573565219.

- ^ UNIX Text Processing, O’Reilly.

Nonetheless, the text editors used in program development environments can provide much better facilities for managing large writing projects than their office word-processing counterparts.

- ^ «Information Control Systems Inc. (ICS) | Ann Arbor District Library».

- ^ «Secretaries Get a Computer of their Own to Automate Typing» (PDF). Computers and Automation. January 1969. p. 59. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ «Computer Aided Typists Produce Perfect Copies». Computer World. November 13, 1968. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Pozzi, Sandro (12 December 2018). «Muere Evelyn Berezin, creadora del primer procesador digital de textos» [Evelyn Berezin dies, creator of the first digital text processor]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

Berezin diseñó el primer sistema central de reservas de United Airlines cuando trabajaba para Teleregister y otro similar para gestionar la contabilidad de la banca a nivel nacional. En 1968 empezó a trabajar en la idea de un ordenador que procesara textos, utilizando pequeños circuitos integrados. Al año decidió dejar la empresa para crear la suya propia, que llamó Redactron Corporation.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (2018-12-10). «Evelyn Berezin, 93, Dies; Built the First True Word Processor». The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ a b c Smith, William D. (October 26, 1971). «Lag Persists for Business Equipment». The New York Times. p. 59.

- ^ a b Dullea, Georgia (February 5, 1974). «Is It a Boon for Secretaries—Or Just an Automated Ghetto?». The New York Times. p. 32.

- ^ «IBM Adds to Line of Dictation Items». The New York Times. September 12, 1972. p. 72. reports introduction of «five new models of ‘input word processing equipment’, better known in the past as dictation equipment» and gives IBM’s definition of WP as «the combination of people, procedures, and equipment which transforms ideas into printed communications». The machines described were of course ordinary dictation machines recording onto magnetic belts, not voice typewriters.

- ^ Miller, Diane Fisher (1997) «My Life with the Machine»: «By Sunday afternoon, I urgently want to throw the Xerox 800 through the window, then run over it with the company van. It seems that the instructor forgot to tell me a few things about doing multi-page documents … To do any serious editing, I must use both tape drives, and, without a display, I must visualize and mentally track what is going onto the tapes.»

- ^ Smith, William D. (October 8, 1974). «Xerox Is Introducing a Speedier Electric Typewriter». The New York Times. p. 57.

- ^ O’Kane, Lawrence (May 22, 1966). «Computer a Help to ‘Friendly Doc’; Automated Letter Writer Can Dispense a Cheery Word». The New York Times. p. 348.

Automated cordiality will be one of the services offered to physicians and dentists who take space in a new medical center…. The typist will insert the homey touch in the appropriate place as the Friden automated, programmed «Flexowriter» rattles off the form letters requesting payment… or informing that the X-ray’s of the patient (kidney) (arm) (stomach) (chest) came out negative.

- ^ Rostky, Georgy (2000). «The word processor: cumbersome, but great». EETimes. Retrieved 2006-05-29.

- ^ Kirschenbaum, Matthew (March 1, 2013). «The Book-Writing Machine: What was the first novel ever written on a word processor?». Slate. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ Smith, William D. (December 16, 1974). «Electric Typewriter Sales Are Bolstered by Efficiency». The New York Times. p. 57.

- ^ a b Thomas, David (1983). Knights of the New Technology. Toronto: Key Porter Books. p. 94. ISBN 0-919493-16-5.

- ^ a b CBC Television, Venture, «AES: A Canadian Cautionary Tale» Broadcast date February 4, 1985, minute 3:50.

- ^ Thomas, David «Knights of the New Technology». Key Porter Books, 1983, p. 97 & p. 98.

- ^ “Will success spoil Steve Dorsey?”, Industrial Management magazine, Clifford/Elliot & Associates, May 1979, pp. 8 & 9.

- ^ “Will success spoil Steve Dorsey?”, Industrial Management magazine, Clifford/Elliot & Associates, May 1979, p. 7.

- ^ Thomas, David «Knights of the New Technology». Key Porter Books, 1983, p. 102 & p. 103.

- ^ «1970–1979 C.E.: Media History Project». University of Minnesota. May 18, 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ^ Schuyten, Peter J. (1978): «Wang Labs: Healthy Survivor» The New York Times December 6, 1978 p. D1: «[Market research analyst] Amy Wohl… said… ‘Since then, the company has installed more of these systems than any other vendor in the business.»

- ^ «NBI INC Securities Registration, Form SB-2, Filing Date Sep 8, 1998». secdatabase.com. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ Pea, Roy D. and D. Midian Kurland (1987). «Cognitive Technologies for Writing». Review of Research in Education. 14: 277–326. JSTOR 1167314.

- ^ a b Bergin, Thomas J. (Oct–Dec 2006). «The Origins of Word Processing Software for Personal Computers: 1976–1985». IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 28 (4): 32–47. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2006.76. S2CID 18895790.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul (1982-05-10). «Electric Pencil, first micro word processor». InfoWorld. p. 12. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

- ^ Shrayer, Michael (November 1984). «Confessions of a naked programmer». Creative Computing. p. 130. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel [in Spanish] (1992). «Word Processing (History of)». Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science (PDF). Vol. 49. New York: Dekker. pp. 268–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2019.

- ^ Brinkley, Joel (2000-09-21). «It’s a Word World, Or Is It?». The New York Times.

External linksEdit

- FOSS word processors compared: OOo Writer, AbiWord, and KWord by Bruce Byfield

- History of Word Processing

- «Remembering the Office of the Future: Word Processing and Office Automation before the Personal Computer» — A comprehensive history of early word processing concepts, hardware, software, and use. By Thomas Haigh, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 28:4 (October–December 2006):6-31.

- «A Brief History of Word Processing (Through 1986)» by Brian Kunde (December, 1986)

- «AES: A Canadian Cautionary Tale» by CBC Television (Broadcast date: February 4, 1985, link updated Nov. 2, 2012)

According to Frank Bruni, a columnist for the New York Times, one of the most influential classes he ever took was not the one where he first read Plato or discovered The Great Gatsby or learned to appreciate Modern Art or Bach Sonatas. The class that so influenced Bruni was—drum roll please—the summer school program he attended as a teenager to learn how to type.

In an essay titled “What I Learned in Secretarial School,” Bruni extolled the drudgery and humility that was entailed in learning how to properly place one’s hands on a typewriter’s keyboard and type, without looking at the keys, phrases like “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.”

According to Bruni, who has been a Times White House reporter, Rome bureau chief and restaurant critic and is the author of three best-selling books—his ability to get started as a writer owed much to his fluid abilities as a typist. “I developed a reputation as a fleet writer when really I was a fleet typist. The talents were somehow intertwined. Confidence in my typing gave me confidence in everything else.”

Fast forward nearly four decades, and you might be asking “Why wasn’t he allowed to look at the keys?” or “Who cares about the quick fox and the lazy dog?” or even more fundamentally, “What’s a typewriter?”

Read next: Behind the orange icon: the history of PowerPoint

Going back to Gutenberg

To get the answers to those questions, you need to know a bit more about the history of typing and the history of word processing, including the history of word processing software (and inevitably Microsoft Word). And for all of that, even in this brief history of word processing, it’s helpful to very briefly go back a few centuries to when Johannes Gutenberg in 1439 invented moveable type.

Before Gutenberg, all books were completely handwritten. There was no printing as we know it today. Making a second copy of a book involved hiring a scribe to copy the entire book again by hand. Gutenberg essentially invented the printing industry by replacing handwritten letters with blocks of type. Setting the type was laborious, but once it was done the pages could be reproduced much faster, cheaper and in much larger quantities. A Bible Gutenberg completed in 1455 cost the equivalent of three years’ wages of the average clerk—expensive, but a fraction of the cost of hiring a scribe. Books and pamphlets began to fly off the presses, helping to usher in the Reformation, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment or really the world as we know it today.

The invention of the typewriter

Still, someone had to write the text in the first place which required putting pen or pencil to paper. It took more than four centuries for that to change, but eventually it did with the development in the late 1800s of the first successful typewriters. Now someone could sit at a typewriter, insert a blank piece of paper and perfectly formed letters would appear on a page as you pressed each key against an inked ribbon inside the typewriter. Typewriters took off in the business world. Instead of handwritten letters or contracts, in which penmanship might lead to errors or legal issues, the cleanly written pages that flew out of typewriters greased the wheels of commerce.

As typewriters became essential in the business world, the demand grew for fast, accurate typists. Training programs similar to the one Bruni attended proliferated. Practicing phrases like “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” were helpful because they were a way to train your hands to correctly hit all the right keys without looking (which would slow you down). Businesses employed thousands of typists.

Being a good typist was about more than just speed

However, to be a good typist, you had to be more than just fast. You had to know…

- How to insert the paper in the typewriter so each page started in the same place.

- How to correctly set the line spacing and the margins—especially the right margin where, when you reached it, a bell would ring warning you to hit the carriage return to move down a line and back to the left margin. (Woe to you if you ignored the bell).

- Also, because business documents followed specific formats—especially business letters—a major part of your training was to learn that template: the placement of the date, your contact information, the recipient’s information, the salutation, the body of the letter, the closing, etc. The worst thing you could do was get the formatting wrong and go back and retype everything.

Typewriters had no memory capabilities, making retyping documents a fact of life. But that began to change in the 1960s with typewriters like the hugely popular IBM Selectric series that essentially launched the era of word processing. These new memory typewriters could store information on magnetic tapes and later cards. When a mistake was made, the typist would simply backspace the typewriter and retype the correct text over the original error. The typewriter could remember the correct version so when the typist would insert a new blank sheet, the typewriter would automatically print out a flawless version of the desired text.

In the 1970s, the invention of larger storage devices (the first floppy disks) and cheaper computer memory led to word processing solutions capable of storing and managing whole documents. That was followed by the addition of cathode ray tube (CRT) screens and computerized printers. Now you could easily view the entire page as you were typing, go back and forth to make edits and instantly print out the results. The modern era of word processing took off.