1. What is the word processing?

Word processing is the use of computers to type, edit, and print letters, reports, articles, and other documents.

2. What are the main types of equipment?

Three main types of equipment are personal computers, dedicated word processors, and electronic typewriters.

3. Do personal computers need special instructions?

Personal computers need special instructions called programs or software to perform word processing.

4. What does the computer provide?

The computer provides limited word processing capabilities, such as the ability to store and automatically type a small amount of text.

5. What do personal computers and dedicated word processors display on a computer screen?

Personal computers and dedicated word processors display characters on a computer screen as the user types them.

Word processing generally means the task of creating printed materials like letters, reports, thesis, books and so on. It involves the tasks such as entering text, editing, formatting, proofing, and printing.

Word processing nowadays is the use of computer to produce documents consisting primarily of text or words (as distinguished from numbers). Word processor is a general application software used for producing such text documents.

In the initial days of development, the computer was primarily used for performing mathematical calculations. The documents produced on computers consisted of recording the results of the calculation with a very little textual material. With the development, special computers and computer software were developed to produce documents such as letters and reports. Such computers were used in the printing industry for composing the material for printing.

These days, it is common that the computers are used extensively for word processing, and has almost replaced conventional typewriters across the world.

Of all computer applications, word processing is probably the most common. To perform word processing, you need a computer, a special program called a word processor, and a printer. A word processor enables you to create a document, store it electronically on a disk, display it on a screen, modify it by entering commands and characters from the keyboard, and print it on a printer.

The great advantage of word processing over using a typewriter is that you can make changes without retyping the entire document. If you make a typing mistake, you simply back up the cursor and correct your mistake. If you want to delete a paragraph, you simply remove it, without leaving a trace. It is equally easy to insert a word, sentence, or paragraph in the middle of a document. Word processors also make it easy to move sections of text from one place to another within a document, or between documents. When you have made all the changes you want, you can send the file to a printer to get a hard-copy or disk to store for future purpose.

Basic Features of Word Processors

There are various Word processors, but all word processors support the following basic features:

- Insert text: Lets you to insert text anywhere in the document.

- Delete text: You can remove characters, words, lines, or pages from document easily and without leaving any trace.

- Cut and paste : It has facilities to move the selected text by removing (cut) it from one place of document and inserting (paste) it somewhere else.

- Copy : Supports creating duplicate of a selection of text without any trouble.

- Page size and margins : It has options to define and change among various page sizes and margins, and the word processor will automatically readjust the text so that it fits in new layout.

- Search and replace : Allows you to search for a particular word or phrase in document. You can also replace one text with another and optionally everywhere that the match occurs.

- Word wrap : Word processor has this feature to automatically moves to the next line after you complete a line. This is also known as soft line break or auto line break. Word wrap also readjust text if you change the margins, paper orientation or page size.

- Print: Word processor supports various printers to send a document for printout.

Word processors that support only these features (and maybe a few others) are called text editors. Most word processors, however, support additional features that enable you to manipulate and format documents in more sophisticated ways. These more advanced word processors are sometimes called full-featured word processors.

Additional Features of Full-featured Word Processors

- File management : Many word processors contain file management capabilities that allow you to create, delete, move, and search for files. File menu is MS Word has commands for this task.

- Font specifications: Allows you to change typeface (fonts) within a document. You can specify font, font size, font styles such as bold, italics, and underlining and different effects like superscript, subscript, outline, strike-through etc.

- Footnotes and cross-references: Automates the numbering and placement of footnotes and enables you to easily cross-reference other sections of the document.

- Graphics: Allows you to embed illustrations (images) and graphs into a document. Some word processors let you create the illustrations within the word processor (using autoshapes and drawing tools); others let you insert an illustration produced by a different program.

- Headers , footers , and page numbering: Allows you to specify customized headers and footers that the word processor will place at the top and bottom of every page. It can keeps track of page numbers so that the correct number appears on each page.

- Layout : Supports different page size, margins and page orientation within a single document. It also has facility to apply various indentation to paragraphs.

- Macros : A macro is a character or word that represents a series of keystrokes. The keystrokes can represent text or commands. The ability to define macros allows you to save yourself a lot of time by replacing common combinations of keystrokes.

- Merges: Allows you to merge text from one file into another file. This is particularly useful for generating many files that have the same format and structure but different data. Generating mailing labels is the classic example of using merges.

- Spell checker : A utility that allows you to check the spelling of words. It will mark any word having spelling mistake or that it does not recognize. Spell checkers have ability to produce a list of suggested word to make you easier to correct mistakes.

- Table of contents and indexes: Word processors have features to automatically create a table of contents and index based on special codes that you insert in the document.

- Thesaurus: Word processors have a built-in thesaurus that allows you to search for synonyms without leaving the document.

- Windows : Lets you to edit two or more documents at the same time. Each document appears in a separate window. This is particularly valuable when working on a large project that consists of several different files.

- WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get): With WYSIWYG, a document appears on the display screen exactly as it will look when printed.

Word Processors And Desktop Publishing Systems

Desktop publishing is as good as having a mini-printing press within a personal computer. Publishing software helps design the page layout for each document. Tools in desktop publishing applications can help the user to configure the layout, where things are printed in the final design and how things are printed.

The line dividing word processors from desktop publishing (DTP) systems is constantly shifting. In general, though, desktop publishing applications support finer control over layout, and more support for full-color documents.

Both word processing and desktop publishing are similar in many ways but different in areas that cover the publication of documents.

Similarities between Word Processors and Desktop Publishing Systems

- Both the word processor and DTP systems deal with text that can be formatted.

- Word processors and desktop publishing systems work with tables and pictures.

- Both tools have many similar features like WordArt, Clip Art, and text styles.

The differences between Word Processors and DTP Systems

Word processing involves creation, editing, and printing of text while desktop publishing involves production of documents that combine text with graphics.

- Word processing is difficult to layout and design as compared to desktop publishing. Thus, desktop publishing is used to work on things like newsletters, magazines, adverts, and brochures where layout is important. Word processing documents are common for simple memos, letters, manuscripts, and resumes.

- When creating a desktop publisher, the first page is blank and a text frame must be added to add text. This is unlike the word processing in which text can be directly entered into the blank page.

- With desktop publishing, users can easily manipulate text and graphics and try new ideas. In contrast to this, word processing tools are adding more page layout features. Thus, the line that draws the difference between the two hardly exists now.

- Though there are many differences between the two, more word processing applications are coming out with enhanced features that mimic many of the desktop publishing tools on the market today. So, whether you choose to use word processing or desktop publishing software all depends on your document publishing needs and what application your are most comfortable using

Types of Word Processing

Word Processing applications are organized into a number of categories according to their complexity: Simple programs that manipulate ASCII are called Text Editors. More complex programs that feature formatting commands are called Word Processors. Some word processors are included in integrated application packages, which also feature other application programs. Such packages are convenient, but may not have all the features of larger programs. Full – featured word processing programs contain many options for formatting text and documents. They also might contain special utilities for more complex formatting and composition. Desktop publishing programs are designed for more complex formatting, especially the integration of text and graphics.

Text Editors

The simplest programs that do word processing are known as text editors. These programs are designed to be small, simple, and cheap. Almost every operating system comes with at least one text editor built in. Most text editors save files in a special format called ASCII. The biggest advantage of this scheme is that almost any program can read and write ASCII text.

The biggest advantage of text editors is the price. There is probably already one or more installed on your computer. You can find a number of text editors for free on the Internet. The ability to write ASCII text is the biggest benefit of text editors. It is a very good way of storing text information, but it has no way of handling more involved formatting. Text editors generally do not allow you to do things like change font sizes or styles, spell checking, or columns.

Windows: Notepad, DOS: Edit, Macintosh: SimpleText etc are some common text editor programs:

Integrated Packages

An integrated package is a huge program that contains a word processor, a spreadsheet, a database tool, and other software applications in the same program. The advantages of an integrated package derive from the fact that all the applications are part of the same program, and were written by the same company. Since they were presumably written together, they should all have the same general menu structure, and similar commands. The word processor built into an integrated package is probably more powerful than a typical text editor.

Integrated packages have some disadvantages. With the advent of GUI and modern operating systems, programs have become more and more standard even if they were written by completely different companies. The programmers had to make some compromises in order to make all the applications fit in one program. Word processing programs that are part of integrated packages generally have their own special code for storing text information, although they can usually read and write ASCII as well. However, if you choose to save in ASCII, you cannot save all the special formatting commands.

Microsoft Works, Microsoft Office Suite, Lotus Works, Claris Works are some examples of integrated packages.

High-end Word Processors

Word processing programs have evolved a great deal from the early days of computing. A modern word processing program can do many things besides simply handling text.

Since the early ’90s, most word processors feature a WYSIWYG interface. This feature is important because the real strength of word processors is in the formatting they allow. Formatting is the manipulation of characters, paragraphs, pages, and documents.

Modern word processors also are designed to have numerous features for advanced users. Some of the additional features that one can expect to find on a modern word processor are spelling and grammar checkers, ability to handle graphics, tables, and mathematical formulas, and outline editors.

These full-featured word processors sound wonderful, and they are. You might wonder if they have any drawbacks.

- Word processing programs as I have described often cost hundreds of dollars.

- Many of the features of full – fledged word processors are not needed by casual users.

- High-end word processing programs almost always save documents in special proprietary codes rather than as ASCII code. This makes the document incompatible with other applications. If you write a document in WordPerfect, you may not be able to read it in Word.

WordPerfect, Microsoft Word are some examples of commercial Word Processing packages

Desktop Publishing

Another classification of word processing you should know about has an uncertain future. These programs are called desktop publishing applications. Desktop publishing is taking the text that already been created, and applying powerful formatting features to that text. Traditionally, applications that allowed the integration of text and graphics, and allowed the development of style sheets were thought of as desktop publishing. Such a program makes it easy to create other kinds of documents than plain pages. With a desktop publisher, there are already style sheets developed to help you create pamphlets, cards, signs, and other types of documents that you wouldn’t be able to create on a typewriter.

The higher end word processing programs give you most of the features you could want in a desktop publishing program. It is possible to do many of the same things. Desktop Publishers are still very popular in certain specialty fields (graphic arts, printing, and publishing,) but the effects can be duplicated with skillful use of a word processing program.

Adobe Pagemaker, Adobe Illustrator, Microsoft Publisher are the example of some common Desktop Publishing programs.

Sign / Banner Programs

Another level of desktop publishing that has become very popular is the advent of specialty printing programs such as ‘The Print Shop’ or ‘Print Master +.’ These programs are designed specifically to help the user create signs, banners, and greeting cards. They are very easy to use, and much less expensive than full-feature desktop publishing applications, but again the effects can be duplicated with a higher end word processor.

Points to Remember

- Word processing did not develop out of computer technology. It evolved from the needs of writers rather than those of mathematicians, only later merging with the computer field

- The term word processing was invented by IBM in the late 1960s.

- A word processor is a computer application used for the production (including composition, editing, formatting, and possibly printing) of any sort of printable material.

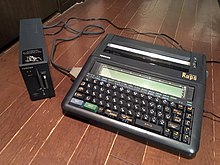

- Word processor may also refer to a type of stand-alone office machine, popular in the 1970s and 1980s, combining the keyboard text-entry and printing functions of an electric typewriter with a dedicated processor (like a computer processor) for the editing of text.

- Microsoft Word is the most widely used word processing software. Many other word processing applications exist, including WordPerfect (which dominated the market from the mid-1980s to early-1990s on computers running MS-DOS operating system) and open source applications OpenOffice.org Writer, LibreOffice Writer, AbiWord, KWord, and LyX. Web-based word processors, such as Office Web Apps or Google Docs, are a relatively new category.

- Desktop publishing applications support finer control over layout and more support for full-color documents where as the word processing systems focus on editing and formatting of text.

- Text Editors, Integrated Packages, High-end Word Processors, Desktop Publishing, Sign / Banner Programs are the different types of word processors.

References:

- Webopedia – http://www.webopedia.com

- Wikipedia – http://en.wikipedia.org

- Bright Hub – http://www.brighthub.com

- IUPUI, Department of Computer and Information Science – http://cs.iupui.edu/

Recommended Reading:

- A brief history of WordProcessing

- WordProcessors: Stupid and Inefficient by Allin Cottrell

- Desktop Publishing: by Szu-chia Wang

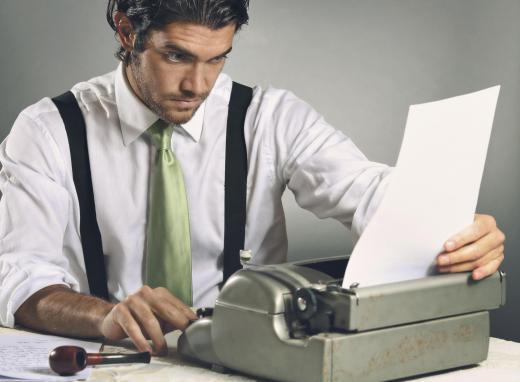

Word processing is the process of adding text to a word processing unit such as a computer or typewriter. The typed words are stored in the computer or word processor temporarily to allow for editing before a hard copy of the document. The term «word processing» is a fairly general term, so it may refer to several types of writing without the use of pen and paper. Typewriters, for example, process words directly onto a paper without storing the data, while computers use specific programs to store the typed data before printing.

Modified typewriters have been commonly used in the past for word processing. The typewriter would store the data — usually with the use of a computer chip — before printing the words onto a page. The person using the word processor could then check the writing for errors before printing the final draft. When computers became common in the workplace and at home, word processors became mostly obsolete, though some models are still used for a wide range of purposes, including as educational devices for students with special needs.

Computers have generally taken over word processing duties. The computers feature specific programs in which a person can type manuscripts of any length. The data is stored as an electronic document that can be opened, closed, saved, and edited at any time. This allows the user to make corrections or changes to a document multiple times before printing out a hard copy of the document. In many cases, the document is not printed out onto hard copy paper at all; instead, it can be used on the internet, in e-mails, or for other digital purposes.

Simpler programs, such as text editors or notepads, can be used to record text quickly without excess formatting options, such as multiple fonts or font sizes. Such programs are easy to use and do not come loaded with formatting features, such as color, multiple fonts, line spacing options, and so on. They are meant to be used for quick word processing that will not need to be formatted for presentation.

Word processing software often includes several features unavailable on typewriters or older word processors. Such features may include the ability to manipulate the layout of the text, the size and color of the font, the type of font used, line spacing, margin adjustments, and the ability to insert photos, web links, graphs, charts, and other objects directly into the document.

Word Processing

Andrew Prestage, in Encyclopedia of Information Systems, 2003

I. An Introduction to Word Processing

Word processing is the act of using a computer to transform written, verbal, or recorded information into typewritten or printed form. This chapter will discuss the history of word processing, identify several popular word processing applications, and define the capabilities of word processors.

Of all the computer applications in use, word processing is by far the most common. The ability to perform word processing requires a computer and a special type of computer software called a word processor. A word processor is a program designed to assist with the production of a wide variety of documents, including letters, memoranda, and manuals, rapidly and at relatively low cost. A typical word processor enables the user to create documents, edit them using the keyboard and mouse, store them for later retrieval, and print them to a printer. Common word processing applications include Microsoft Notepad, Microsoft Word, and Corel WordPerfect.

Word processing technology allows human beings to freely and efficiently share ideas, thoughts, feelings, sentiments, facts, and other information in written form. Throughout history, the written word has provided mankind with the ability to transform thoughts into printed words for distribution to hundreds, thousands, or possibly millions of readers around the world. The power of the written word to transcend verbal communications is best exemplified by the ability of writers to share information and express ideas with far larger audiences and the permanency of the written word.

The increasingly large collective body of knowledge is one outcome of the permanency of the written word, including both historical and current works. Powered by decreasing prices, increasing sophistication, and widespread availability of technology, the word processing revolution changed the landscape of communications by giving people hitherto unavailable power to make or break reputations, to win or lose elections, and to inspire or mislead through the printed word.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0122272404001982

Computers and Effective Security Management1

Charles A. Sennewald, Curtis Baillie, in Effective Security Management (Sixth Edition), 2016

Word Processing

Word processing software can easily create, edit, store, and print text documents such as letters, memoranda, forms, employee performance evaluations (such as those in Appendix A), proposals, reports, security surveys (such as those in Appendix B), general security checklists, security manuals, books, articles, press releases, and speeches. A professional-looking document can be easily created and readily updated when necessary.

The length of created documents is limited only by the storage capabilities of the computer, which are enormous. Also, if multiple copies of a working document exist, changes to it should be promptly communicated to all persons who use the document. Specialized software, using network features, can be programmed to automatically route changes to those who need to know about updates.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128027745000241

Globalization

Jennifer DeCamp, in Encyclopedia of Information Systems, 2003

II.D.2.c. Rendering Systems

Special word processing software is usually required to correctly display languages that are substantially different from English, for example:

- 1.

-

Connecting characters, as in Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Hindi, and Hebrew

- 2.

-

Different text direction, as in the right-to-left capability required in Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and Hindi, or the right-to-left and top-to-bottom capability in formal Chinese

- 3.

-

Multiple accents or diacritics, such as in Vietnamese or in fully vowelled Arabic

- 4.

-

Nonlinear text entry, as in Hindi, where a vowel may be typed after the consonant but appears before the consonant.

Alternatives to providing software with appropriate character rendering systems include providing graphic files or elaborate formatting (e.g., backwards typing of Arabic and/or typing of Arabic with hard line breaks). However, graphic files are cumbersome to download and use, are space consuming, and cannot be electronically searched except by metadata. The second option of elaborate formatting often does not look as culturally appropriate as properly rendered text, and usually loses its special formatting when text is added or is upgraded to a new system. It is also difficult and time consuming to produce. Note that Microsoft Word 2000 and Office XP support the above rendering systems; Java 1.4 supports the above rendering systems except for vertical text.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0122272404000800

Text Entry When Movement is Impaired

Shari Trewin, John Arnott, in Text Entry Systems, 2007

15.3.2 Abbreviation Expansion

Popular word processing programs often include abbreviation expansion capabilities. Abbreviations for commonly used text can be defined, allowing a long sequence such as an address to be entered with just a few keystrokes. With a little investment of setup time, those who are able to remember the abbreviations they have defined can find this a useful technique. Abbreviation expansion schemes have also been developed specifically for people with disabilities (Moulton et al., 1999; Vanderheiden, 1984).

Automatic abbreviation expansion at phrase/sentence level has also been investigated: the Compansion (Demasco & McCoy, 1992; McCoy et al., 1998) system was designed to process and expand spontaneous language constructions, using Natural Language Processing to convert groups of uninflected content words automatically into full phrases or sentences. For example, the output sentence “John breaks the window with the hammer” might derive from the user input text “John break window hammer” using such an approach.

With the rise of text messaging on mobile devices such as mobile (cell) phones, abbreviations are increasingly commonplace in text communications. Automatic expansion of many abbreviations may not be necessary, however, depending on the context in which the text is being used. Frequent users of text messaging can learn to recognize a large number of abbreviations without assistance.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123735911500152

Case Studies

Brett Shavers, in Placing the Suspect Behind the Keyboard, 2013

Altered evidence and spoliation

Electronic evidence in the form of word processing documents which were submitted by a party in litigation is alleged to have been altered. Altered electronic evidence has become a common claim with the ability to determine the changes becoming more difficult. How do you know if an email has been altered? What about a text document?

Case in Point

Odom v Microsoft and Best Buy, 2006

The Odom v Microsoft and Best Buy litigation primarily focused on Internet access offered to customers in which the customers were automatically billed for Internet service without their consent. One of the most surprising aspects of this case involved the altering of electronic evidence by an attorney for Best Buy. The attorney, Timothy Block, admitted to altering documents prior to producing the documents in discovery to benefit Best Buy.

Investigative Tips: All evidence needs to be validated for authenticity. The weight given in legal hearings depends upon the veracity of the evidence. Many electronic files can be quickly validated through hash comparisons. An example seen in Figure 11.4 shows two files with different file names, yet their hash values are identical. If one file is known to be valid, perhaps an original evidence file, any file matching the hash values would also be a valid and unaltered copy of the original file.

Figure 11.4. Two files with different file names, but having the same hash value, indicating the contents of the files are identical.

Alternatively, Figure 11.5 shows two files with the same file name but having different hash values. If there were a claim that both of these files are the same original files, it would be apparent that one of the files has been modified.

Figure 11.5. Two files with the same file names, but having different hash values, indicating the contents are not identical.

Finding the discrepancies or modifications of an electronic file can only be accomplished if there is a comparison to be made with the original file. Using Figure 11.5 as an example, given that the file having the MD5 hash value of d41d8cd98f00b204e9800998ecf8427e is the original, and where the second file is the alleged altered file, a visual inspection of both files should be able to determine the modifications. However, when only file exists, proving the file to be unaltered is more than problematic, it is virtually impossible.

In this situation of having a single file to verify as original and unaltered evidence, an analysis would only be able to show when the file was modified over time, but the actual modifications won’t be known. Even if the document has “track changed” enabled, which logs changes to a document, that would only capture changes that were tracked, as there may be more untracked and unknown changes.

As a side note to hash values, in Figure 11.5, the hash values are completely different, even though the only difference between the two sample files is a single period added to the text. Any modification, no matter how minor, results in a drastic different hash value.

The importance in validating files in relation to the identification of a suspect that may have altered a file is that the embedded metadata will be a key point of focus and avenue for case leads. As a file is created, copied, modified, and otherwise touched, the file and system metadata will generally be updated.

Having the dates and times of these updates should give rise to you that the updates occurred on some computer system. This may be on one or more computers even if the file existed on a flash drive. At some point, the flash drive was connected to a computer system, where evidence on a system may show link files to the file. Each of these instances of access to the file is an opportunity to create a list of possible suspects having access to those systems in use at each updated metadata fields.

In the Microsoft Windows operating systems, Volume Shadow Copies may provide an examiner with a string of previous versions of a document, in which the modifications between each version can be determined. Although not every change may have been incrementally saved by the Volume Shadow Service, such as if the file was saved to a flash drive, any previous versions that can be found will allow to find some of the modifications made.

Where a single file will determine the outcome of an investigation or have a dramatic effect on the case, the importance of ‘getting it right’ cannot be overstated. Such would be the case of a single file, modified by someone in a business office, where many persons had common access to the evidence file before it was known to be evidence. Finding the suspect that altered the evidence file may be simple if you were at the location close to the time of occurrence. Interviews of the employees would be easier as most would remember their whereabouts in the office within the last few days. Some may be able to tell you exactly where other employees were in the office, even point the suspect out directly.

But what if you are called in a year later? How about 2 or more years later? What would be the odds employees remembering their whereabouts on a Monday in July 2 years earlier? To identify a suspect at this point requires more than a forensic analysis of a computer. It will probably require an investigation into work schedules, lunch schedules, backup tapes, phone call logs, and anything else to place everyone somewhere during the time of the file being altered.

Potentially you may even need to examine the hard drive of a copy machine and maybe place a person at the copy machine based on what was copied at the time the evidence file was being modified. When a company’s livelihood is at stake or a person’s career is at risk, leave no stone unturned. If you can’t place a suspect at the scene, you might be able to place everyone else at a location, and those you can’t place, just made your list of possible suspects.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781597499859000113

When, How, and Why Do We Trust Technology Too Much?

Patricia L. Hardré, in Emotions, Technology, and Behaviors, 2016

Trusting Spelling and Grammar Checkers

We often see evidence that users of word processing systems trust absolutely in spelling and grammar checkers. From errors in business letters and on resumes to uncorrected word usage in academic papers, this nonstrategy emerges as epidemic. It underscores a pattern of implicit trust that if a word is not flagged as incorrect in a word processing system, then it must be not only spelled correctly but also used correctly. The overarching error is trusting the digital checking system too much, while the underlying functional problem is that such software identifies gross errors (such as nonwords) but cannot discriminate finer nuances of language requiring judgment (like real words used incorrectly). Users from average citizens to business executives have become absolutely comfortable with depending on embedded spelling and grammar checkers that are supposed to autofind, trusting the technology so much that they often do not even proofread. Like overtrust of security monitoring, these personal examples are instances of reduced vigilance due to their implicit belief that the technology is functionally flawless, that if the technology has not found an error, then an error must not exist.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128018736000054

Establishing a C&A Program

Laura Taylor, Matthew Shepherd Technical Editor, in FISMA Certification and Accreditation Handbook, 2007

Template Development

Certification Packages consist of a set of documents that all go together and complement one another. A Certification Package is voluminous, and without standardization, it takes an inordinate amount of time to evaluate it to make sure all the right information is included. Therefore, agencies should have templates for all the documents that they require in their Certification Packages. Agencies without templates should work on creating them. If an agency does not have the resources in-house to develop these templates, they should consider outsourcing this initiative to outside consultants.

A template should be developed using the word processing application that is the standard within the agency. All of the relevant sections that the evaluation team will be looking for within each document should be included. Text that will remain constant for a particular document type also should be included. An efficient and effective C&A program will have templates for the following types of C&A documents:

- ▪

-

Categorization and Certification Level Recommendation

- ▪

-

Hardware and Software Inventory

- ▪

-

Self-Assessment

- ▪

-

Security Awareness and Training Plan

- ▪

-

End-User Rules of Behavior

- ▪

-

Incident Response Plan

- ▪

-

Security Test and Evaluation Plan

- ▪

-

Privacy Impact Assessment

- ▪

-

Business Risk Assessment

- ▪

-

Business Impact Assessment

- ▪

-

Contingency Plan

- ▪

-

Configuration Management Plan

- ▪

-

System Risk Assessment

- ▪

-

System Security Plan

- ▪

-

Security Assessment Report

The later chapters in this book will help you understand what should be included in each of these types of documents. Some agencies may possibly require other types of documents as required by their information security program and policies.

Templates should include guidelines for what type of content should be included, and also should have built-in formatting. The templates should be as complete as possible, and any text that should remain consistent and exactly the same in like document types should be included. Though it may seem redundant to have the exact same verbatim text at the beginning of, say, each Business Risk Assessment from a particular agency, each document needs to be able to stand alone and make sense if it is pulled out of the Certification Package for review. Having similar wording in like documents also shows that the packages were developed consistently using the same methodology and criteria.

With established templates in hand, it makes it much easier for the C&A review team to understand what it is that they need to document. Even expert C&A consultants need and appreciate document templates. Finding the right information to include the C&A documents can by itself by extremely difficult without first having to figure out what it is that you are supposed to find—which is why the templates are so very important. It’s often the case that a large complex application is distributed and managed throughout multiple departments or divisions and it can take a long time to figure out not just what questions to ask, but who the right people are who will know the answers.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781597491167500093

Speech Recognition

John-Paul Hosom, in Encyclopedia of Information Systems, 2003

I.B. Capabilities and Limitations of Automatic Speech Recognition

ASR is currently used for dictation into word processing software, or in a “command-and-control” framework in which the computer recognizes and acts on certain key words. Dictation systems are available for general use, as well as for specialized fields such as medicine and law. General dictation systems now cost under $100 and have speaker-dependent word-recognition accuracy from 93% to as high as 98%. Command-and-control systems are more often used over the telephone for automatically dialing telephone numbers or for requesting specific services before (or without) speaking to a human operator. Telephone companies use ASR to allow customers to automatically place calls even from a rotary telephone, and airlines now utilize telephone-based ASR systems to help passengers locate and reclaim lost luggage. Research is currently being conducted on systems that allow the user to interact naturally with an ASR system for goals such as making airline or hotel reservations.

Despite these successes, the performance of ASR is often about an order of magnitude worse than human-level performance, even with superior hardware and long processing delays. For example, recognition of the digits “zero” through “nine” over the telephone has word-level accuracy of about 98% to 99% using ASR, but nearly perfect recognition by humans. Transcription of radio broadcasts by world-class ASR systems has accuracy of less than 87%. This relatively low accuracy of current ASR systems has limited its use; it is not yet possible to reliably and consistently recognize and act on a wide variety of commands from different users.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0122272404001647

Prototyping

Rex Hartson, Pardha Pyla, in The UX Book (Second Edition), 2019

20.7 Software Tools for Making Wireframes

Wireframes can be sketched using any drawing or word processing software package that supports creating and manipulating shapes. While many applications suffice for simple wireframing, we recommend tools designed specifically for this purpose. We use Sketch, a drawing app, to do all the drawing. Craft is a plug-in to Sketch that connects it to InVision, allowing you to export Sketch screen designs to InVision to incorporate hotspots as working links.

In the “Build mode” of InVision, you work on one screen at a time, adding rectangular overlays that are the hotspots. For each hotspot, you specify what other screen you go to when someone clicks on that hotspot in “Preview mode.” You get a nice bonus using InVision: In the “operate” mode, you, or the user, can click anywhere in an open space in the prototype and it highlights all the available links. These tools are available only on Mac computers, but similar tools are available under Windows.

Beyond this discussion, it’s not wise to try to cover software tools for making prototypes in this kind of textbook. The field is changing fast and whatever we could say here would be out of date by the time you read this. Plus, it wouldn’t be fair to the numerous other perfectly good tools that didn’t get cited. To get the latest on software tools for prototyping, it’s better to ask an experienced UX professional or to do your research online.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128053423000205

Design Production

Rex Hartson, Partha S. Pyla, in The UX Book, 2012

9.5.3 How to Build Wireframes?

Wireframes can be built using any drawing or word processing software package that supports creating and manipulating shapes, such as iWork Pages, Keynote, Microsoft PowerPoint, or Word. While such applications suffice for simple wireframing, we recommend tools designed specifically for this purpose, such as OmniGraffle (for Mac), Microsoft Visio (for PC), and Adobe InDesign.

Many tools and templates for making wireframes are used in combination—truly an invent-as-you-go approach serving the specific needs of prototyping. For example, some tools are available to combine the generic-looking placeholders in wireframes with more detailed mockups of some screens or parts of screens. In essence they allow you to add color, graphics, and real fonts, as well as representations of real content, to the wireframe scaffolding structure.

In early stages of design, during ideation and sketching, you started with thinking about the high-level conceptual design. It makes sense to start with that here, too, first by wireframing the design concept and then by going top down to address major parts of the concept. Identify the interaction conceptual design using boxes with labels, as shown in Figure 9-4.

Take each box and start fleshing out the design details. What are the different kinds of interaction needed to support each part of the design, and what kinds of widgets work best in each case? What are the best ways to lay them out? Think about relationships among the widgets and any data that need to go with them. Leverage design patterns, metaphors, and other ideas and concepts from the work domain ontology. Do not spend too much time with exact locations of these widgets or on their alignment yet. Such refinement will come in later iterations after all the key elements of the design are represented.

As you flesh out all the major areas in the design, be mindful of the information architecture on the screen. Make sure the wireframes convey that inherent information architecture. For example, do elements on the screen follow a logical information hierarchy? Are related elements on the screen positioned in such a way that those relationships are evident? Are content areas indented appropriately? Are margins and indents communicating the hierarchy of the content in the screen?

Next it is time to think about sequencing. If you are representing a workflow, start with the “wake-up” state for that workflow. Then make a wireframe representing the next state, for example, to show the result of a user action such as clicking on a button. In Figure 9-6 we showed what happens when a user clicks on the “Related information” expander widget. In Figure 9-7 we showed what happens if the user clicks on the “One-up” view switcher button.

Once you create the key screens to depict the workflow, it is time to review and refine each screen. Start by specifying all the options that go on the screen (even those not related to this workflow). For example, if you have a toolbar, what are all the options that go into that toolbar? What are all the buttons, view switchers, window controllers (e.g., scrollbars), and so on that need to go on the screen? At this time you are looking at scalability of your design. Is the design pattern and layout still working after you add all the widgets that need to go on this screen?

Think of cases when the windows or other container elements such as navigation bars in the design are resized or when different data elements that need to be supported are larger than shown in the wireframe. For example, in Figures 9-5 and 9-6, what must happen if the number of photo collections is greater than what fits in the default size of that container? Should the entire page scroll or should new scrollbars appear on the left-hand navigation bar alone? How about situations where the number of people identified in a collection are large? Should we show the first few (perhaps ones with most number of associated photos) with a “more” option, should we use an independent scrollbar for that pane, or should we scroll the entire page? You may want to make wireframes for such edge cases; remember they are less expensive and easier to do using boxes and lines than in code.

As you iterate your wireframes, refine them further, increasing the fidelity of the deck. Think about proportions, alignments, spacing, and so on for all the widgets. Refine the wording and language aspects of the design. Get the wireframe as close to the envisioned design as possible within the constraints of using boxes and lines.

Read full chapter

URL:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123852410000099

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

WordPerfect, a word processor first released for minicomputers in 1979 and later ported to microcomputers, running on Windows XP

A word processor (WP)[1][2] is a device or computer program that provides for input, editing, formatting, and output of text, often with some additional features.

Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to the function, but current word processors are word processor programs running on general purpose computers.

The functions of a word processor program fall somewhere between those of a simple text editor and a fully functioned desktop publishing program. However, the distinctions between these three have changed over time and were unclear after 2010.[3][4]

Background[edit]

Word processors did not develop out of computer technology. Rather, they evolved from mechanical machines and only later did they merge with the computer field.[5] The history of word processing is the story of the gradual automation of the physical aspects of writing and editing, and then to the refinement of the technology to make it available to corporations and Individuals.

The term word processing appeared in American offices in early 1970s centered on the idea of streamlining the work to typists, but the meaning soon shifted toward the automation of the whole editing cycle.

At first, the designers of word processing systems combined existing technologies with emerging ones to develop stand-alone equipment, creating a new business distinct from the emerging world of the personal computer. The concept of word processing arose from the more general data processing, which since the 1950s had been the application of computers to business administration.[6]

Through history, there have been three types of word processors: mechanical, electronic and software.

Mechanical word processing[edit]

The first word processing device (a «Machine for Transcribing Letters» that appears to have been similar to a typewriter) was patented by Henry Mill for a machine that was capable of «writing so clearly and accurately you could not distinguish it from a printing press».[7] More than a century later, another patent appeared in the name of William Austin Burt for the typographer. In the late 19th century, Christopher Latham Sholes[8] created the first recognizable typewriter although it was a large size, which was described as a «literary piano».[9]

The only «word processing» these mechanical systems could perform was to change where letters appeared on the page, to fill in spaces that were previously left on the page, or to skip over lines. It was not until decades later that the introduction of electricity and electronics into typewriters began to help the writer with the mechanical part. The term “word processing” (translated from the German word Textverarbeitung) itself was created in the 1950s by Ulrich Steinhilper, a German IBM typewriter sales executive. However, it did not make its appearance in 1960s office management or computing literature (an example of grey literature), though many of the ideas, products, and technologies to which it would later be applied were already well known. Nonetheless, by 1971 the term was recognized by the New York Times[10] as a business «buzz word». Word processing paralleled the more general «data processing», or the application of computers to business administration.

Thus by 1972 discussion of word processing was common in publications devoted to business office management and technology, and by the mid-1970s the term would have been familiar to any office manager who consulted business periodicals.

Electromechanical and electronic word processing[edit]

By the late 1960s, IBM had developed the IBM MT/ST (Magnetic Tape/Selectric Typewriter). This was a model of the IBM Selectric typewriter from the earlier part of this decade, but it came built into its own desk, integrated with magnetic tape recording and playback facilities along with controls and a bank of electrical relays. The MT/ST automated word wrap, but it had no screen. This device allowed a user to rewrite text that had been written on another tape, and it also allowed limited collaboration in the sense that a user could send the tape to another person to let them edit the document or make a copy. It was a revolution for the word processing industry. In 1969, the tapes were replaced by magnetic cards. These memory cards were inserted into an extra device that accompanied the MT/ST, able to read and record users’ work.

In the early 1970s, word processing began to slowly shift from glorified typewriters augmented with electronic features to become fully computer-based (although only with single-purpose hardware) with the development of several innovations. Just before the arrival of the personal computer (PC), IBM developed the floppy disk. In the early 1970s, the first word-processing systems appeared which allowed display and editing of documents on CRT screens.

During this era, these early stand-alone word processing systems were designed, built, and marketed by several pioneering companies. Linolex Systems was founded in 1970 by James Lincoln and Robert Oleksiak. Linolex based its technology on microprocessors, floppy drives and software. It was a computer-based system for application in the word processing businesses and it sold systems through its own sales force. With a base of installed systems in over 500 sites, Linolex Systems sold 3 million units in 1975 — a year before the Apple computer was released.[11]

At that time, the Lexitron Corporation also produced a series of dedicated word-processing microcomputers. Lexitron was the first to use a full-sized video display screen (CRT) in its models by 1978. Lexitron also used 51⁄4 inch floppy diskettes, which became the standard in the personal computer field. The program disk was inserted in one drive, and the system booted up. The data diskette was then put in the second drive. The operating system and the word processing program were combined in one file.[12]

Another of the early word processing adopters was Vydec, which created in 1973 the first modern text processor, the «Vydec Word Processing System». It had built-in multiple functions like the ability to share content by diskette and print it.[further explanation needed] The Vydec Word Processing System sold for $12,000 at the time, (about $60,000 adjusted for inflation).[13]

The Redactron Corporation (organized by Evelyn Berezin in 1969) designed and manufactured editing systems, including correcting/editing typewriters, cassette and card units, and eventually a word processor called the Data Secretary. The Burroughs Corporation acquired Redactron in 1976.[14]

A CRT-based system by Wang Laboratories became one of the most popular systems of the 1970s and early 1980s. The Wang system displayed text on a CRT screen, and incorporated virtually every fundamental characteristic of word processors as they are known today. While early computerized word processor system were often expensive and hard to use (that is, like the computer mainframes of the 1960s), the Wang system was a true office machine, affordable to organizations such as medium-sized law firms, and easily mastered and operated by secretarial staff.

The phrase «word processor» rapidly came to refer to CRT-based machines similar to Wang’s. Numerous machines of this kind emerged, typically marketed by traditional office-equipment companies such as IBM, Lanier (AES Data machines — re-badged), CPT, and NBI. All were specialized, dedicated, proprietary systems, with prices in the $10,000 range. Cheap general-purpose personal computers were still the domain of hobbyists.

Japanese word processor devices[edit]

In Japan, even though typewriters with Japanese writing system had widely been used for businesses and governments, they were limited to specialists who required special skills due to the wide variety of letters, until computer-based devices came onto the market. In 1977, Sharp showcased a prototype of a computer-based word processing dedicated device with Japanese writing system in Business Show in Tokyo.[15][16]

Toshiba released the first Japanese word processor JW-10 in February 1979.[17] The price was 6,300,000 JPY, equivalent to US$45,000. This is selected as one of the milestones of IEEE.[18]

Toshiba Rupo JW-P22(K)(March 1986) and an optional micro floppy disk drive unit JW-F201

The Japanese writing system uses a large number of kanji (logographic Chinese characters) which require 2 bytes to store, so having one key per each symbol is infeasible. Japanese word processing became possible with the development of the Japanese input method (a sequence of keypresses, with visual feedback, which selects a character) — now widely used in personal computers. Oki launched OKI WORD EDITOR-200 in March 1979 with this kana-based keyboard input system. In 1980 several electronics and office equipment brands entered this rapidly growing market with more compact and affordable devices. While the average unit price in 1980 was 2,000,000 JPY (US$14,300), it was dropped to 164,000 JPY (US$1,200) in 1985.[19] Even after personal computers became widely available, Japanese word processors remained popular as they tended to be more portable (an «office computer» was initially too large to carry around), and become necessities in business and academics, even for private individuals in the second half of the 1980s.[20] The phrase «word processor» has been abbreviated as «Wa-pro» or «wapuro» in Japanese.

Word processing software[edit]

The final step in word processing came with the advent of the personal computer in the late 1970s and 1980s and with the subsequent creation of word processing software. Word processing software that would create much more complex and capable output was developed and prices began to fall, making them more accessible to the public. By the late 1970s, computerized word processors were still primarily used by employees composing documents for large and midsized businesses (e.g., law firms and newspapers). Within a few years, the falling prices of PCs made word processing available for the first time to all writers in the convenience of their homes.

The first word processing program for personal computers (microcomputers) was Electric Pencil, from Michael Shrayer Software, which went on sale in December 1976. In 1978 WordStar appeared and because of its many new features soon dominated the market. However, WordStar was written for the early CP/M (Control Program–Micro) operating system, and by the time it was rewritten for the newer MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System), it was obsolete. Suddenly, WordPerfect dominated the word processing programs during the DOS era, while there was a large variety of less successful programs.

Early word processing software was not as intuitive as word processor devices. Most early word processing software required users to memorize semi-mnemonic key combinations rather than pressing keys such as «copy» or «bold». Moreover, CP/M lacked cursor keys; for example WordStar used the E-S-D-X-centered «diamond» for cursor navigation. However, the price differences between dedicated word processors and general-purpose PCs, and the value added to the latter by software such as “killer app” spreadsheet applications, e.g. VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3, were so compelling that personal computers and word processing software became serious competition for the dedicated machines and soon dominated the market.

Then in the late 1980s innovations such as the advent of laser printers, a «typographic» approach to word processing (WYSIWYG — What You See Is What You Get), using bitmap displays with multiple fonts (pioneered by the Xerox Alto computer and Bravo word processing program), and graphical user interfaces such as “copy and paste” (another Xerox PARC innovation, with the Gypsy word processor). These were popularized by MacWrite on the Apple Macintosh in 1983, and Microsoft Word on the IBM PC in 1984. These were probably the first true WYSIWYG word processors to become known to many people.

Of particular interest also is the standardization of TrueType fonts used in both Macintosh and Windows PCs. While the publishers of the operating systems provide TrueType typefaces, they are largely gathered from traditional typefaces converted by smaller font publishing houses to replicate standard fonts. Demand for new and interesting fonts, which can be found free of copyright restrictions, or commissioned from font designers, occurred.

The growing popularity of the Windows operating system in the 1990s later took Microsoft Word along with it. Originally called «Microsoft Multi-Tool Word», this program quickly became a synonym for “word processor”.

From early in the 21st century Google Docs popularized the transition to online or offline web browser based word processing, this was enabled by the widespread adoption of suitable internet connectivity in businesses and domestic households and later the popularity of smartphones. Google Docs enabled word processing from within any vendor’s web browser, which could run on any vendor’s operating system on any physical device type including tablets and smartphones, although offline editing is limited to a few Chromium based web browsers. Google Docs also enabled the significant growth of use of information technology such as remote access to files and collaborative real-time editing, both becoming simple to do with little or no need for costly software and specialist IT support.

See also[edit]

- List of word processors

- Formatted text

References[edit]

- ^ Enterprise, I. D. G. (1 January 1981). «Computerworld». IDG Enterprise. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Waterhouse, Shirley A. (1 January 1979). Word processing fundamentals. Canfield Press. ISBN 9780064537223. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Amanda Presley (28 January 2010). «What Distinguishes Desktop Publishing From Word Processing?». Brighthub.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «How to Use Microsoft Word as a Desktop Publishing Tool». PCWorld. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ Price, Jonathan, and Urban, Linda Pin. The Definitive Word-Processing Book. New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1984, page xxiii.

- ^ W.A. Kleinschrod, «The ‘Gal Friday’ is a Typing Specialist Now,» Administrative Management vol. 32, no. 6, 1971, pp. 20-27

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. The Tech Ninja. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ See also Samuel W. Soule and Carlos Glidden.

- ^ The Scientific American, The Type Writer, New York (August 10, 1872)

- ^ W.D. Smith, “Lag Persists for Business Equipment,” New York Times, 26 Oct. 1971, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Linolex Systems, Internal Communications & Disclosure in 3M acquisition, The Petritz Collection, 1975.

- ^ «Lexitron VT1200 — RICM». Ricomputermuseum.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Hinojosa, Santiago (1 June 2016). «The History of Word Processors». The Tech Ninja’s Dojo. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «Redactron Corporation. @ SNAC». Snaccooperative.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ «日本語ワードプロセッサ». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ «【シャープ】 日本語ワープロの試作機». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^ 原忠正 (1997). «日本人による日本人のためのワープロ». The Journal of the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan. 117 (3): 175–178. Bibcode:1997JIEEJ.117..175.. doi:10.1541/ieejjournal.117.175.

- ^ «プレスリリース;当社の日本語ワードプロセッサが「IEEEマイルストーン」に認定». 東芝. 2008-11-04. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ^

«【富士通】 OASYS 100G». IPSJコンピュータ博物館. Retrieved 2017-07-05. - ^ 情報処理学会 歴史特別委員会『日本のコンピュータ史』ISBN 4274209334 p135-136