English Word Jokes With Explanations: A Humorous Approach to Language Learning

7 min

Created: March 21st, 2023Last updated: April 12th, 2023

Contents

What did the pirate say when he turned 80? Aye, matey! See, this is one of our favorite wordplay jokes in English. And we will tell you much more than just this one since we believe the language-studying process shouldn’t be boring.

Non-native speakers often limit themselves to humor for fear of saying something wrong. But the point is that jokes are a great way to boost your language level and self-confidence. This article provides tips and types of tricky humor in English to make the most out of it. So, please, make yourself comfortable and forget about tedious rules because today we are just going to have fun.

Why Play-On-Words Jokes Are A Great Way To Improve Your English

The main reason why people give up their language-learning goals is simple – they become bored. Sometimes, it is not enough to learn the rules. And in such cases, studying through funny word jokes seems like the perfect way to enhance your fluency level. Here are only a few reasons that explain the benefits of wordplay humor:

- A fun way to expand vocabulary. Most play-on-words jokes are based on idioms, puns, and other forms of figurative language. Hence, the more gags you use in daily conversations or hear from your interlocutors, the more new words and phrases you remember.

- The main way to understand English humor. Do you know how many “knock-knock” jokes are out there? Well, nobody knows that, but we are confident that there are millions of them. They are one of the whales that maintain English comedy and are primarily based on word plays. Hence, learning such jokes is a key to understanding natives and their sense of humor.

- Major confidence booster. A good joke is a great ice-breaker – you can use it to start a conversation, smooth out an awkward silence, or defuse a tense situation. And when you hear other people laughing at your jokes, your confidence goes above and beyond.

And we will not even start with other advantages of funny play-on-words jokes, like boosting memory or enhancing comprehension and pronunciation skills. We want you to see them all by yourself. So, without further ado, let’s move on to the next topic.

7

Types of Wordplay Jokes

Since there are many kinds of word jokes, it is essential to understand the difference between them all. Therefore, here are the most common types of wordplay jokes you can hear from native speakers:

- Puns. According to Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a pun is a joke that exploits the multiple meanings of a word or phrase for humorous effect.

- Spoonerisms. It is a type of wordplay where two words’ initial sounds or letters are switched to create a new phrase.

- Double entendres. It is a phrase or statement with a double interpretation, often with one meaning being suggestive or inappropriate.

- Tom Swifty. It is a type of pun where an adverb is used to modify a quote or statement humorously.

Now you know a bit more about variations of the wordplay jokes. And it means it’s time to finally have a good laugh and check out our favorite puns, spoonerisms, and double entendres.

Some think understanding humor in a non-native language is the final step to fluency. And we can’t argue with that! Therefore, here are some famous gags to make you giggle and help you with your studying at the same time.

- Why is the six afraid of the seven? Because 7 8 9.

If you don’t get this one, try to read it aloud. This way, you will see that the poor six is afraid because it doesn’t want to be eaten by her hungry neighbor (seven ate nine).

- Why did the tomato turn red? Because it saw the salad dressing.

It is another excellent pun based on the two meanings of the word “dressing” (like the condiment and the process of putting on clothes).

- My kids like chilled grease sandwiches I make for them.

It is an example of spoonerism – the initial letters of the words grilled cheese were switched, and instead of a tasty sandwich, poor kids got, well, a funny joke.

- Why didn’t the skeleton go to the party? He had no body to go with.

Here is another excellent tip for making a guru and telling the best wordplay jokes. The simpler and sillier it sounds, the better the effect will be. Like this pun – it is so bad that it is actually very good.

- Why do the Promova tutors wear sunglasses to their lessons? Because their students are very bright.

One more tip for you – jokes don’t have to be rude or offensive. Occasionally, they can be silly little compliments to make someone smile. Like this one – the point is in the double meaning of the word bright (literal one – bright like the sun, and the second one – bright as intelligent).

- I used to be a baker, but I couldn’t make enough dough.

Last but not least, a joke on our list is also based on double meanings (apparently, these are our favorites). In this case, the word dough has two meanings – literal, as a substance for making bread, and slang as a description of slang for money.

Funny Word Play Examples

Alright, we know that you want more than that. Therefore, here is another list of hilarious wordplay jokes. But this time, we didn’t add any captions or explanations – try to practice and understand the point yourself.

- Did you hear about the guy who lost his left arm and leg in a car crash? He’s all right now.

- I used to play piano by ear, but now I use my hands.

- What’s the difference between a poorly-dressed man on a trampoline and a well-dressed man on a trampoline? Attire.

- I’m trying to organize a hide-and-seek competition, but finding good players is hard.

- Why did the bicycle fall over? Because it was two tired.

- Why do seagulls fly over the sea? Because if they flew over the bay, they’d be bagels.

- What do you call a can opener that doesn’t work? A can’t opener.

And that’s it! Congratulations, you are probably now fluent in English if you got those jokes right. And if not – don’t worry because most of them are confusing. Instead, write your favorite wordplay jokes in the comments section. You know that we are always up for a good laugh.

Mastering Humor and Fluency with Promova

As much as English jokes might be fun for native speakers, they can confuse language learners. Hence, reaching some proficiency level to joke and understand puns and spoonerisms is essential. And if you are struggling with finding the best studying option, say no more. Here, at Promova, we know exactly what to offer you.

But before that, what is Promova? It is an international language-learning platform available for students from all over the world. After visiting the official website, you can choose from several options to get started.

- Personal and group lessons with experienced tutors. Our team of professionals is always ready to help you achieve your studying goals. You can start your 1-to-1 lessons or join a group of up to six people from different countries to have more fun.

- Convenient mobile application. If you prefer studying alone, you can do so from the comfort of your bed. Just install the Promova application from the App Store or Google Play and access unique lessons suitable for your needs.

- Conversation Club. What is the best way to practice wordplay jokes? Only telling them to other people. And if you don’t have English speakers in your surroundings, we invite you to our free Conversation Club! Here you can discuss exciting topics, meet new friends, and simply have fun.

And, of course, we couldn’t forget about the Promova Blog! Here you will find dozens of thrilling articles that will help you learn valuable information, tips, popular language-learning trends, and much more. And guess what? It is also entirely free! So please, don’t waste another minute – visit the official Promova website now and find the studying plan of your dream.

Conclusion

Okay, we got the last one for you. Why did the pregnant woman start screaming, “Isn’t, can’t, I’m” in the middle of the street? Because she was having contractions. And that’s it for today! We hope that this article helps you broaden your humor horizons because jokes are the perfect way to feel fluent and confident when speaking a foreign language. And don’t forget – studying English doesn’t have to be tedious. Together, we can make it fun.

FAQ

What are homophone jokes?

Homophone wordplay jokes are the ones created by using homophones – words that spell differently but sound the same. For example, what do you call a deer with no eyes? No idea (no e- d r). Homophone jokes are very popular among people of different ages because they can have both innocent and inappropriate contexts.

Are there any differences between puns and double entendres?

Yes, there is a difference. Even though both types of wordplay jokes are based on double meanings, they differ in context. Puns are just simple, silly gags that have no sexual undertone. Double entendres, on the other hand, also have two meanings, but one interpretation is usually risqué.

Is it always a good time to say wordplay jokes?

Unfortunately, it is not. Many people don’t like such jokes and even find them annoying. Therefore, you need to be sure you have the right audience before telling your puns. Also, there are many situations where any joke might be considered inappropriate. You need to be careful and analyze the circumstances to avoid any misunderstandings.

What are some common tips for memorizing wordplay jokes?

Some common tips for memorizing wordplay jokes include practicing them beforehand, writing them down for later reference, and using mnemonic devices to help remember them. Additionally, it’s helpful to think about the structure of the joke and how the words play off each other, which can aid in recall.

Hear it from the experts

Let our global subject matter experts broaden your perspective with timely insights and opinions you

can’t find anywhere else.

Subscribe to unlock this article

Try unlimited access

Try full digital access and see why over 1 million readers subscribe to the FT

Only

$1 for 4 weeks

Explore our subscriptions

Individual

Find the plan that suits you best.

Group

Premium access for businesses and educational institutions.

Cookies on FT Sites

We use

cookies

and other data for a number of reasons, such as keeping FT Sites reliable and secure,

personalising content and ads, providing social media features and to

analyse how our Sites are used.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer or company.

Wordplay: The sport of a wordsmith.

In hip-hop, the greatest rappers to have ever touched a mic and spit their truth have dabbled in this art. Some have done it more smoothly than others, who—in their own right—have made the obvious a bit more clear.

Wordplay can come about in a multitude of directions, but the overall goal is to execute a pun or pop culture reference through word alterations and the flipping of meanings. A few methods include: internal rhyme schemes; varying pronunciations; synonyms; synonyms juxtaposed by antonyms; syllable breakdowns; double, triple, and even quadruple entendres; and spelling.

With Eminem releasing his latest album Kamikaze, there’s been some internet buzz about who the best to ever do it is. Some of these debates already exist on the archives of the internet—I’m sure we can trace back to some examples existing in REVOLT’s content alone.

To be clear, this article is not attempting to throw its two cents in the debate of who the best wordplay-ist is, but rather go lyric by lyric on some of the top-notch, heavy-hitter examples hip-hop has ever delivered to the culture.

Starting with easy one-liners:

“She almost got cut short—you know, scissors” — Slick Rick, “Mona Lisa” (1988)

An easy one with the answer right in the lyric! The slickest to ever do it, Slick Rick recalls meeting this tempting beauty, named after the painting, at a pizza parlor. In the middle of their conversation, he almost interrupts her (“cut short”). And “you know,” what do scissors do? It’s almost a shame he didn’t describe her haircut.

“Real Gs move in silence like lasagna” — Lil Wayne, “6 Foot, 7 Foot” (2011)

Simple play here: The letter “g” is in the word “lasagna.” The “G” will always remain silent no matter how many times you try to pronounce it. Hustlas (aka “G’s”), like Lil Wayne, know how to remain in silence about their moves.

“I’m not gay, I just wanna boogie to some Marvin” — Tyler, The Creator, “Yonkers” (2011)

Let’s stir the pot with a pop culture reference. Here, Tyler is addressing rumors about his sexuality but simultaneously acknowledging a legend, Marvin Gay(e), whose style of music has a “boogie” groove to it.

Now to the ones that S-P-E-L-L out T-H-E M-E-A-N-I -N-G:

“I’m the L-I-L to the K-I-M / And not B-I-G, R.I.P. ba-by” — Lil’ Kim, “Spell Check” (2005)

One of the best to ever do it, Lil’ Kim immediately gets to the point on the first line off The Naked Truth. She spells out her name in the introduction and notes how opposites attract in size. The “not” deads all criticisms that “Biggie wrote her shit,” but she makes sure to show love and respect to her mentor, who has taught her a thing or two about spelling.

“Ride the dick like a BMX, no nigga wanna Be My eX” — Cardi B, “Motorsport” (2017)

While the Queen Bee of Rap directed her spelling at critics, the Empress warned rejected suitors with her wordplay, while in full costume. She equates her kamasutra to the X Games sport. God forbid her partner messes up, and crashes to ex territory, as she phonetically spells out with “Be My Ex.” (An honorable mention has to go to Remy Ma’s “Nigga you can Be my eX, that’s where I’m from” on “Money Showers” (2017), which rather nods to the Bronx.)

Now that we’ve warmed up to wordplay, it’s time to take a Kurtis Blow moment with some noteworthy chorus examples, because these are the…

“Brakes on a bus, brakes on a car / Breaks to make you a superstar / Breaks to win and breaks to lose / But these here breaks will rock your shoes / And these are the breaks / Break it up, break it up, break it up!” — Kurtis Blow, “The Breaks” (1980)

What made “The Breaks” one of hip-hop’s first commercial success stories is its relatability factor in the storytelling. Kurtis Blow had delivered rap’s version of the facts of life. Breaks, the device on a vehicle, are meant to stop motion. Sometimes life is interrupted by unfortunate breaks. In fact, these so-called “breaks” do happen to appear in a monthly schedule, at least the amount of times they appear in this hook.

“You niggas want word play, I’m ’bout birdplay / First of the month, yeah, we call that bird day (Look at ’em fly)” — Jeezy, “Word Play” (2008)

Flash forward to 38 years after “The Breaks,” and the genre of trap—specifically from the Southern hemisphere of America spanning from Atlanta to New Orleans—had taken over hip-hop. Still, there were the skeptics of this sound that complained about a lack of crafty lyricism resembling the Golden Age. At the forefront of the commercial movement, Jeezy responds to his critics via an appropriately titled song from his album The Recession. Jeezy claims he’s all about being a dope rapper in this line, hence “birdplay,” a slang for slinging drugs. However, “look at em fly” acknowledges how words can still effortlessly roll off his tongue.

“I can’t even roll in peace (why?) / Everybody notice me (yeah) / I can’t even go to sleep (why?) / I’m rolling on a bean (yeah) / They tried to give me eight / Got on my knees like “Jesus please” / He don’t even believe in Jesus / Why you got a Jesus piece?” — Kodak Black, “Roll In Peace” (2017)

As a protege of Jeezy, Kodak Black offers a hook that’s both morose and addictive, and a standout amongst this new generation of rappers. First, “Roll In Peace” spells out RIP to match the graveyard music. Jesus is associated depending on what religious burial is taking place, or when you’re being sentenced to time, who you pray to last minute. Second, “roll” could mean the action for a blunt, as well as tripping out on a pill (“bean”).

Now for the bars that mix in snapshots of pop culture:

“Ha, holla cross from the land of the lost / Behold the pale horse, off course (off course)” — Method Man, Wu-Tang Clan’s “Gravel Pit” (2000)

Method Man stands tall amongst the greats who, if you don’t pay attention to every detail in their verses, the references will go over your head. That’s just how smooth he is. Now this opening verse is often disputed: Is he saying “ha, holla cross,” or “ha holocaust”? Either way, each interpretation still ties into a religious allusion, albeit the latter is more gruesome, to say the least. Now, “Gravel Pit” returns to Wu-Tang’s underground sound, as RZA mentions in the intro, but it’s somewhat lost musically in the new millennium climate. Wu-Tang Clan still remained holy figures in rap regardless, bringing prophetic wisdom and blessings to the game. On this journey, Method Man brings a pale horse into the conversation, who just so happens to be “off course” in “the land of lost.” This horse also happens to know one of Mr. Ed’s—America’s first sitcom horse—theme song, which starts “a horse is a horse, of course, of course.” See: smooth word play!

“Now, pan right for the angle / I got away with murder, no scandal, cue the violins and Violas” — Janelle Monae, “Django Jane” (2018)

On a song titled after the female equivalent to Jamie Foxx’s slave revolting superhero, Janelle Monae pushes against perceptions media has placed on the black image. She also celebrates them, like in this line, directing her next punchline’s “angle” (with a “pan right”). She salutes the Shondaland Thursday primetime line-up for ABC (“How To GetAway With Murder” and “Scandal”), before instructing the strings players of her band to play the instrument sharing a name with the HTGAWM lead actress.

“Niggas talkin’ shit, ‘Ye—how do you respond? / Poop, scoop! / Whoop! Whoopty-whoop!” — Pusha T and Kanye West, “What Would Meek Do?” (2018)

Pusha T asks him a question and Kanye responds with his infamous lines from “Lift Yourself.” Of course we don’t have to point out the obvious synonyms, but what a great alley-oop-oop-oop-oopty-oop through collaboration.

Here are some examples of musical terminology and rapping ability tied to double meanings:

“Rappers, I monkey flip ’em with the funky rhythm I be kickin’ / Musician inflictin’ composition of pain” — Nas, “New York State of Mind” (1994)

Simply the best to utilize wordplay, the examples from Nas are endless. But this informal introduction to the power of his skill takes the cake. A monkey flip is a wrestling and breakdancing move that requires the person to kick. A monkey flip in the ring of the WWF (or WCW, WWE depending on which generation you associate), in particular, flips the opponent over. Sounds painful. Musicians and rappers make “compositions” through “rhythms.” Of course, Nas’ wordplay is some of the most lethal.

“Listen, you should buy a sixteen, ’cause I write it good / That 808 WOOF WOOF, ’cause I ride it good / And bitches can’t find they man, ’cause I ride it good / I’m the wolf, where is Little Red Riding Hood?” — Nicki Minaj, “Itty Bitty Piggy” (2009)

One aspect that can’t be denied with Nicki’s craft is her ability to ride a beat. That’s exhibited well in her flow and deuce set of sixteen bars from her mixtape days. She interchanges “write” and “ride” with similar pronunciation. Nicki’s exemplary wordplay is ran by her “rrr’s” and “w’s.” The “woof woof” shows onomatopoeia tying into the “wolf,” but also the sound of the beat’s 808. Little Red Riding Hood is a pop culture reference that ties back into the variations of “ride” and “write.”

“Crack off nigga, I’m squeezing empty ’til the shell break / Fuck my image I need to drop, I need to, Blank Face” — ScHoolboy Q, “Blank Face” (2016)

With this bar, ScHoolboy Q masks his wordplay to create a vivid image. He mentions his gun “cracking off,” which directs attention to what a shell can do once it “breaks.” There’s also the shell of a gun which will “break” after he empties the clip, or possibly an AK-47. “I need to drop” could mean two things: killing thy enemies on sight and/or disappearing after committing the act—hence the need for a discreet “blank face.” But there’s one last meaning: his album being named Blank Face would also “need to drop” in time for the scheduled release. Maybe the West Coast rapper is tying all this into annihilating the game with his rapid and energetic delivery.

If there are three legendary emcees from the Golden Age with OG wordplay, look no further:

“Eric be easy on the cut, no mistakes allowed / ‘Cause to me, MC means move the crowd / I made it easy to dance to this / But can you detect what’s coming next from the flex of the wrist? / Say ‘indeed’ and I’ll proceed ’cause my man made a mix / If he bleed he won’t need no band-aid to fix / His fingertips sew a rhyme until there’s no rhymes left / I hurry up because the cut will make ’em bleed to death” — Rakim, “Eric B Is President” (1987)

With Rakim on wax, it’s like you’re in conversation, and every time he speaks there’s not just one message, but quite a few. There is a large serving of wordplay here so let’s digest this bite by bite: “Eric b(e)” is of course a play on of his DJ partner in crime who is the muse behind this song and its lyrics. Rakim is requesting precision from Eric B so that he can “MC,” or rather move the crowd, efficiently. “Man made a mix” plays on the homophone of “manmade,” that which hip-hop ultimately is a manmade art. “Band aid” simply makes you ask, “what DJ ever needed a band to fix their mistakes or hand them a band-aid should they ever bleed?” Finally, Eric B is “sewing” together the production behind Rakim, helping to stitch his rhymes together. For the slam dunk, Rakim loops back into “cut” which means the cut of music or at the turntables, and a physical cut that would make “em bleed to death.”

“Rappers stepping to me / They want to get some / But I’m the Kane so, yo, you know the outcome / Another victory / They can’t get with me / So pick a BC date because you’re history.” — Big Daddy Kane, “Ain’t No Half Steppin’” (1988)

It’s only fair that a great who has felt imitated by others would compare himself to the first human ever born, the biblical figure Cain. Cain existed in the BC time period, while this song was released during the AD (where it seems other MCs can’t presently hang with Big Daddy Kane). Not only is he telling them they’re old news, he calls it all “history.”

“Who da freshest motherfucker in rap? / You better dig in your crates, who lives what they state? / Who’s the most consistent to date? / If you’re talking 2Pac or B.I.G., you late (KRS!)” — KRS-One, “Who Da Best” (2010)

Being one of hip-hop’s titan truthsayers, KRS-One’s arsenal of puns and punchlines are endless. Take this example where he has to quickly remind the new school of his legendary status on an alchemical EP called Back to the L.A.B. (Lyrical Ass Beating). While many will say “da freshest in rap” are either of the “late” greats “2Pac or B.I.G.,” KRS-One tells us to go look at the records and vinyls in the “crates” before their time. There is also the juxtaposition of “live” and “late,” as KRS is freshly “stating” his case while alive.

Okay, this one’s a Biggie:

“Now check it: I got more mack than Craig, and in the bed / Believe me, sweetie, I got enough to feed the needy /No need to be greedy, I got mad friends with Benzes /C-notes by the layers, true fuckin’ players” — The Notorious B.I.G., “Big Poppa” (1994)

Being the G.O.A.T., Biggie had the ability to highlight luxury and materialism to give his verses the charismatic life they packed. There’s the name drop of his Bad Boy label mate, Craig Mack which he uses the last name to compare his sexual prowess (mack could also tie into that obscenity before “players”). Then we get to his rich friends, who also happen to be musicians or “players” who have dealt with “C-notes,” wads of $100 bills and on the music scale. Mercedes Benz has a C-class of cars which are considered to be some of the highest for the luxury car market. But back to the “now check it,” usually the rich write checks to “feed the needy,” through charity.

Rarely mentioned gems from some top class elite MCs.

“I father, I Brooklyn Dodger them / I jack, I rob, I sin / Aww man, I’m Jackie Robinson / ‘Cept when I run base, I dodge the pen” — JAY-Z, “Brooklyn (Go Hard)” (2008)

For the Notorious soundtrack, JAY-Z salutes his and B.I.G.’s home borough through an old-school reference. Jackie Robinson became the first black player of the MLB, competing for the Brooklyn Dodgers. The phonetic breakdown of “jack,” “rob,” and “sin”—with “I” in front of each word—sets up the first analogy. Here, JAY is also discussing criminal activity, drawing back to his days of “running base” in the streets, and not the kind Jackie Robinson ran on the fields. The “dodge the pen” not only completes “Brooklyn Dodger,” but alludes to two points: JAY can avoid jail time when he’s selling drugs and his skill of not having to write down verses.

“Streets don’t fail me now, they tell me it’s a new gang in town / From Compton to Congress, set trippin’ all around / Ain’t nothin’ new, but a flu of new Demo-Crips and Re-Blood-licans / Red state versus a blue state, which one you governin’?” — Kendrick Lamar, “Hood Politics” (2015)

Systematic oppression is what created gang life as a means of survival in the first place, so leave it to Kendrick to eloquently bring that up. He associates Washington, D.C. government with the same “trippin’” behavior as the gangs banging out in his hometown Compton. He renames the Democratic Party after the blue repping Crips, and the Republican Party after the red riding Bloods. At the end, he ask listeners “which one you governin’,” or basically what state are they living in relation to these matters.

Most importantly, some Kaepernick play action:

“In case my lack of reply had you catchin’ them feelings / Know you’ve been on my mind like Kaepernick kneelin’” — J. Cole, Miguel’s “Come Through and Chill” (2017)

Earlier in this Miguel collaboration, J. Cole—who has been a front and center proponent for Kaepernic—left his love interest on red. He returns back a few verses later to finish his thought. Here’s an allusion to Kaepernick focused on the act of “catchin’,” either the actual football he throws or the NFL fans mulling over their feelings regarding his protesting.

“Feed me to the wolves, now I lead the pack and shit / You boys all cap, I’m more Colin Kaepernick” — Big Sean, “Big Bank” (2018)

Simple here: “wolves” come in a “pack.” Kaepernick himself is a quarterback who has to lead his team of players. “Cap” is also the salary limit in major league sports, which Big Sean claims he’s above just like Colin Kaepernick, as he’s not currently associating with the rules of the NFL for a payday.

Some Kamikaze wordplay, because relevancy is also key:

“You play your cards, I reverse on you all / And I might just drop 4 like a Uno” — Joyner Lucas, Eminem’s “Lucky You” (2018)

As one of the standout features on Kamikaze, Joyner Lucas shoots rapid fire while relating the game to the Uno card game. There’s a “reverse” card which changes the game’s rotation (as both men attempt to do on this song), and a Draw 4 is rephrased to “drop 4.” Lucas then proceeds to drop 4 bars right after this wordplay.

“Levels to this shit, I got an elevator / You could never say to me I’m not a fuckin’ record breaker / I sound like a broken record every time I break a record / Nobody could ever take away the legacy, I made a navigator” — Eminem, “Lucky You” (2018)

While many claim to be the master of wordplay, Eminem seamlessly takes that skill to another “level” just like an “elevator.” After seeing many multi-platinum albums—two going diamond—he, for sure, is a “record breaker” who then flips the script into “break a record.” Then there’s “I made a navigator,” which indicates he can show you the direction to take hip-hop, but he also navigated some of its present “legacy” with the contributions he “made.”

“I’m in the court of public opinion, ready to click and spray / Light Jay Elec ass up, that’s my Exhibit A / Bitch kill my vibe is what you wanna get into / Drown ’em all in a swimming pool, full of phlegm and drool” — Joe Budden, “Lost Control (Freestyle)” (2013)

Many are doubting if Joe Budden could ever hold his own on wax again, instead of on a podcast. Here’s a reminder to how he responded to Kendrick Lamar’s “Control” verse without even being mentioned. His “Exhibit A” of “lighting” up an “Electronic” monikered rapper ties into being “in the court of public opinion.” Then he drops some Kendrick references: “Bitch Don’t Kill My Vibe” and “Swimming Pools (Drank).” “Phlegm and drool” also point out how Budden’s spitting is creating a pool of lyrics that rappers can’t recover from and will ultimately drown in—just more evidence in the case.

“Now tell me, what do you stand for? (what?) / I know you can’t stand yourself (no) / Tryin’ to be the old you so bad you Stan yourself (ha)” – Machine Gun Kelly on “Rap Devil” (2018)

As the first to officially respond to Eminem’s litany of attacks, Machine Gun Kelly already plays on Em’s “Rap God” by calling himself the “Devil” in the title. Here he uses multiple meanings of “stand” including beliefs being held, and tolerating or liking oneself. Then there’s the punchline: “Stan,” the term for an obsessive fan that Eminem coined in his old days of rap— a flow and energy Em attempts to bring back on Kamikaze.

And for those who felt like they were snubbed from this list, don’t worry. This was a warm-up. The saga will continue…

More from Da’Shan Smith:

It goes without saying that writers are drawn to language, but because we love words so much, the English language is filled with word play. By interrogating the complexities of language—homophones, homographs, words with multiple meanings, sentence structures, etc.—writers can explore new possibilities in their work through a play on words.

It’s easiest to employ word play in poetry, given how many linguistic possibilities there are in poetry that are harder to achieve in prose. Nonetheless, the devices listed in this article apply to writers of all genres, styles, and forms of writing.

After examining different word play examples—such as portmanteaus, malapropisms, and oxymorons—we’ll look at opportunities for how these devices can propel your writing. But first, let’s establish what we mean when we’re talking about a play on words.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Wordplay Definition

Word play, also written as wordplay, word-play, or a play on words, is when a writer experiments with the sound, meaning, and/or construction of words to produce new and interesting meanings. In other words, the writer is twisting language to say something unexpected, with the intent of entertaining or provoking the reader.

Wordplay definition: Experimentation with the sounds, definitions, and/or constructions of words to produce new and interesting meanings.

It should come as no surprise that many word play examples were written by Shakespeare. One such example comes from Hamlet. Some time after Polonius is killed, Hamlet’s uncle, Claudius, asks him where Polonius is. The below exchange occurs:

KING CLAUDIUS

Now, Hamlet, where’s Polonius?

HAMLET

At supper.

KING CLAUDIUS

At supper! where?

HAMLET

Not where he eats, but where he is eaten: a certain

convocation of politic worms are e’en at him. Your

worm is your only emperor for diet: we fat all

creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for

maggots: your fat king and your lean beggar is but

variable service, two dishes, but to one table:

that’s the end.

The line “Not where he eats, but where he is eaten” is a play on words, drawing the audience’s attention to Polonius’ death. He is not eating, but being consumed by the worms. This play on the meaning of “eat” utilizes the verb’s multiple definitions—to consume versus to decompose. (It is also an example of synchysis, and of polyptoton, a type of repetition device.)

The most common of word play examples is the pun. A pun directly plays with the sounds and meanings of words to create new and surprising sentences. For example, “The incredulous cat said you’ve got to be kitten me right meow!” puns on the words “kidding” (kitten) and “now” (meow).

To learn more about puns, check out our article on Pun Examples in Literature. Some of the play on words examples in this article can also count as puns, but because we’ve covered puns in a previous blog, this article covers different and surprising possibilities for twisting and torturing language.

Examples of a Play on Words: 10 Literary Devices

Word play isn’t just a way to have fun with language, it’s also a means of creating new and surprising meanings. By experimenting with the possibilities of sound and meaning, writers can create new ideas that traditional language fails to encompass.

Let’s see word play in action. The following examples of a play on words all come from published works of literature.

1. Word Play Examples: Anthimeria

Anthimeria is a type of word play in which a word is employed using a different part of speech than what is typically associated with that word. (For reference, the parts of speech are: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, articles, interjections, conjunctions, and prepositions.)

Most commonly, a writer using anthimeria will make a verb a noun (nominalization), or make a noun a verb (verbification). It would be much harder to employ this device using other parts of speech: using an adjective as a pronoun, for example, would be difficult to read, even for the reader familiar with anthimeria.

Here are some word play examples using anthimeria:

Nouns to Verbs

The thunder would not peace at my bidding.

—From King Lear, (IV, vi.) by Shakespeare

The word “peace” is being used as a verb, meaning “to calm down.” Many anthimeria examples come to us from Shakespare, in part because of his genius with language, and in part because he needed to use certain words that would preserve the meter of his verse.

“I’ll unhair thy head.”

—From Antony and Cleopatra (II, v.) by Shakespeare

Of course, “unhair” isn’t a word at all. But, it’s using “hair” as a verb, and then using the opposite of that verb, to express scalping someone’s hair off.

Up from my cabin, My sea-gown scarf’d about me, in the dark

Groped I to find out them; had my desire.

—From Hamlet, (V, ii.) by Shakespeare

Shakespeare is using “scarf” as a verb, meaning “to wrap around.” Nowadays, the use of “scarf” as a verb is recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary, but at the time, this was a very new usage of the word.

Verbs to Nouns

It’s difficult to find examples of nominalization in literature, mostly because it’s not a wise decision in terms of writing style. Verbs are the strongest parts of speech: they provide the action of your sentences, and can also provide necessary description and characterization in far fewer words than nouns and adjectives can. Using a verb as a noun only hampers the power of that verb.

Nonetheless, we use verbs as nouns all the time in everyday conversation. If you “hashtag” something on social media, you’re using the noun hashtag as a verb. Or, if you “need a good drink,” you’re noun-ing the verb “drink.” Often, nouns become acceptable dictionary entries for verbs because of the repeated use of nominalizations in everyday speech.

Nouns and Verbs to Adjectives

“The parishioners about here,” continued Mrs. Day, not looking at any living being, but snatching up the brown delf tea-things, “are the laziest, gossipest, poachest, jailest set of any ever I came among.”

—From Under the Greenwood Tree by Thomas Hardy

The words “gossipest, poachest, jailest” might seem silly or immature. But, they’re fun and striking uses of language, and they help characterize Mrs. Day through dialogue.

“I’ll get you, my pretty.”

—From The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

By using the adjective “pretty” as a noun, the witch’s use of anthimeria in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz strikes a chilling note: it’s both pejorative and suggests that the witch could own Dorothy’s beauty.

Anthimeria isn’t just a form of language play, it’s also a means of forging neologisms, which eventually enter the English lexicon. Many words began as anthimerias. For example, the word “typing” used to be a new word, as people didn’t “employ type” until the invention of typing devices, like typewriters. The word “ceiling” comes from an antiquated word “ceil,” meaning sky: “ceiling” means to cover over something, and that verb eventually became the noun we use today.

2. Word Play Examples: Double Entendre

A double entendre is a form of word play in which a word or phrase is used ambiguously, meaning the reader can interpret it in multiple ways. A double entendre usually has a literal meaning and a figurative meaning, with both meanings interacting with each other in some surprising or unusual way.

In everyday speech, the double entendre is often employed sexually. Indeed, writers often use the device lasciviously, and bawdry bards like Shakespeare won’t hesitate when it comes to dirty jokes.

Nonetheless, here a few examples of double entendre that are a little more PG:

“Marriage is a fine institution, but I’m not ready for an institution.”

—Mae West, quoted in The 2,548 Best Things Anybody Ever Said by Robert Byrne

The repeated use of “institution” suggests a double meaning. While marriage is, literally, an institution, West is also suggesting that marriage is an institution in a different sense—like a prison or a psychiatric hospital, one that she’s not ready to commit to.

“What ails you, Polyphemus,” said they, “that you make such a noise, breaking the stillness of the night, and preventing us from being able to sleep? Surely no man is carrying off your sheep? Surely no man is trying to kill you either by fraud or by force?”But Polyphemus shouted to them from inside the cave, “No man is killing me by fraud; no man is killing me by force.”

“Then,” said they, “if no man is attacking you, you must be ill; when Jove makes people ill, there is no help for it, and you had better pray to your father Neptune.”

—Odyssey by Homer

In Homer’s Odyssey, the hero, Odysseus, tells the cyclops Polyphemus that his name is “no man.” Then, when Odysseus blinds Polyphemus, the cyclops is enraged and tells people that “no man” did this, suggesting that his blindness is an affliction from the gods. In this instance, Polyphemus means one thing but communicates another, causing humorous ambiguity for the audience.

On the contrary, Aunt Augusta, I’ve now realized for the first time in my life the vital importance of being Earnest.

—The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People by Oscar Wilde

In Oscar Wilde’s play, the protagonist Jack Worthing leads a double life: to his lover in the countryside, he’s Jack, while he’s Ernest to his lover in the city. The play follows this character’s deceptions, as well as his realization of the necessity of being true to himself. Thus, in this final line of the play, Jack realizes the importance of being “earnest,” a pun and double entendre on “Ernest.”

3. Word Play Examples: Kenning

The kenning is a type of metaphor that was popular among medieval poets. It is a phrase, usually two nouns, that describes something figuratively, often using words only somewhat related to the object being described.

If you’ve read Beowulf, you’ve seen the kenning in action—and you know that, in translation, some kennings are easier understood than others. For example, the ocean is often described as the “whale path,” which makes sense. But a dragon is described as a “mound keeper,” and if you don’t know that dragons in literature tend to hoard piles of gold, it might be harder to understand this kenning.

A kenning is constructed with a “base word” and a “determinant.” The base word has a metaphoric relationship with the object being described, and the determinant modifies the base word. So, in the kenning “whale path,” the “path” is the base word, as it’s a metaphor for the sea. “Whale” acts as a determinant, cluing the reader towards the water.

The kenning is a play on words because it uses marginally related nouns to describe things in new and exciting language. Here are a few examples:

Kenning In Beowulf

At some point in the text of Beowulf, the following kennings occur:

- Battle shirt — armor

- Battle sweat — blood

- Earth hall — burial mound

- Helmet bearer — warrior

- Raven harvest — corpse

- Ring giver — king

- Sail road — the sea

- Sea cloth — sail

- Sky candle — the sun

- Sword sleep — death

Don’t be too surprised by all of the references to fighting and death. Most of Beowulf is a series of battles, and given that the story developed across centuries of Old English, much of the epic poem explores God, glory, and victory.

Kenning Elsewhere in Literature

The majority of kennings come from Old English poetry, though some contemporary poets also employ the device in their work. Here are a few more kenning word play examples.

So the earth-stepper spoke, mindful of hardships,

of fierce slaughter, the fall of kin:

Oft must I, alone, the hour before dawn

lament my care. Among the living

none now remains to whom I dare

my inmost thought clearly reveal.

I know it for truth: it is in a warrior

noble strength to bind fast his spirit,

guard his wealth-chamber, think what he will.

—”The Wanderer” (Anonymous)

“The Wanderer” is a poem anonymously written and preserved in a codex called The Exeter Book, a manuscript from the late 900s. It contains approximately ⅙ of the Old English poetry we know about today. In this poem, an “earth-stepper” is a person, and a “wealth-chamber” is the wanderer’s mind or heart—wherever it is that he stores his immaterial virtues.

No, they’re sapped and now-swept as my sea-wolf’s love-cry.

—from “Cuil Cliffs” by Ian Crockatt

Ian Crockatt is a contemporary poet and translator from Scotland, and his work with Old Norse poetry certainly influences his own poems. “Sea wolf” is a kenning for “sailor,” and a “love cry” is a love poem.

There is a singer everyone has heard,Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again.

He says that leaves are old and that for flowers

Mid-summer is to spring as one to ten.

He says the early petal-fall is past

When pear and cherry bloom went down in showers

On sunny days a moment overcast;

And comes that other fall we name the fall.

He says the highway dust is over all.

The bird would cease and be as other birds

But that he knows in singing not to sing.

The question that he frames in all but words

Is what to make of a diminished thing.

—“The Oven Bird” by Robert Frost

In this Frost sonnet, the speaker employs the kenning “petal-fall” to describe the autumn. The full text of the poem has been included, not for any particular reason, other than it’s simply a lovely, striking poem.

4. Word Play Examples: Malapropism

A malapropism is a device primarily used in dialogue. It is employed when the correct word in a sentence is replaced with a similar-sounding word or phrase that has an entirely different meaning.

For example, the word “assimilation” sounds a lot like the phrase “a simulation.” Employing a malapropism, I might have a character say “Everything is programmed. We all live in assimilation.”

For the most part, malapropisms are humorous examples of a play on words. They often make fun of people who use pretentious language to sound intelligent. But, in everyday speech, we probably employ more malapropisms than we think, so this device also emulates real speech.

The name “malapropism” comes from the play The Rivals by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. In it, the character Mrs. Malaprop often uses words with opposite meanings but similar sounds to the word she intends. Here’s an example from the play:

“He is the very pineapple of politeness!” (Instead of pinnacle.)

Malapropisms are also known as Dogberryisms (from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing), or as acyrologia. Though this word play device is employed humorously, it also demonstrates the complex relationship our brain has with language, and how easy it is to mix words up phonetically.

5. Word Play Examples: Metalepsis

Metalepsis is the use of a figure of speech in a new or surprising context, creating multiple layers of meaning. In other words, the writer takes a figure of speech and employs it metaphorically, using that figure of speech to reference something that is otherwise unspoken.

This is a tricky literary device to define, so let’s look at an example right away:

As he swung toward them holding up the handHalf in appeal, but half as if to keep

The life from spilling…

—“Out, Out” by Robert Frost

The expected phrase here would be “the blood from spilling.” But, in this excerpt, “life” replaces the word “blood.” The word life, then, becomes a metonymy for “blood,” and as this displacement occurs in the common phrase “spilled blood,” “life” becomes a metalepsis.

So, there are two layers of meaning going on here. One is the meaning derived from the phrase “spilled blood,” and the other comes from the use of “life” to represent “blood.” In any metalepsis, there are multiple layers of meaning occurring, as a metaphor or metonymy is employed to modify a figurative phrase, adding complexity to the phrase itself.

This is a tricky, advanced example of word play, and it primarily occurs in poetry. Here are a few other examples in literature:

“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium?”

—Dr. Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Here, the face in question is that of Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman in the world (according to The Iliad and the Odyssey). Helen is claimed by Paris, a prince of Troy, and when he takes Helen home with him, it incites the Trojan war—thus the references to a thousand ships and the towers of Ilium. So, the face refers to Helen, and Faustus describes the beauty of that face tangentially, referencing the magnitude of the Trojan War.

“And I also have given you cleanness of teeth in all your cities.”

—The Book of Amos (4:6)

In this Biblical passage, the phrase “cleanness of teeth” is actually referencing hunger. By having nothing to eat, the people have nothing to stain their teeth with. Thus, the figurative image of clean teeth becomes a metalepsis for starvation.

“To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

—Macbeth (V; v), by Shakespeare

This is a complex extended metaphor and metalepsis. Instead of saying “to the ends of time,” Shakespeare modifies this phrase to “the last syllable of recorded time.” He then extends this idea by saying that life is “a walking shadow, a poor player”—in other words, that which speaks the syllables of recorded time, and then never speaks again. By describing life as an idiot which signifies nothing, Macbeth is saying that life has no inherent value or meaning, and that all men are fools who exist at the whim of a random universe.

Note: this soliloquy arrives after the death of Macbeth’s wife, and it clues us towards Macbeth’s growing madness. So, yes, it’s a very dark passage, but dark for a reason.

To summarize: a metalepsis is a type of word play in which the writer describes something using a tangentially related image or figure of speech. It is, put most succinctly, a metonymy of a metonymy. There is also a narratological device called metalepsis, but it has nothing to do with this particular literary device.

6. Word Play Examples: Oxymoron

An oxymoron is a self-contradictory phrase. It is usually just two words long, with each word’s definition contrasting the other one’s, despite the apparent meaning of the words themselves. It is a play on words because opposing meanings are juxtaposed to form a new, seemingly-impossible idea.

A common example of this is the phrase “virtual reality.” Well, if it’s virtual, then it isn’t reality, just a simulation of a new reality. Nonetheless, we employ those words together all the time, and in fact, the juxtaposition of these incompatible terms creates a new, interesting meaning.

Oxymorons occur all the time in everyday speech. “Same difference,” “Only option,” “live recording,” and even the genre “magical realism.” In any of these examples, a new meaning forms from the placement of these incongruous words.

Here are a few examples from literature:

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.”

—Romeo and Juliet (II; ii), by Shakespeare

“No light; but rather darkness visible”

—Paradise Lost by John Milton

“Their traitorous trueness, and their loyal deceit.”

—“The Hound of Heaven” by Francis Thompson

Note: an oxymoron is not self-negating, but self-contradictory. The use of opposing words should mean that each word cancels the other out, but in a good oxymoron, a new meaning is produced amidst the contradictions. So, you can’t just put two opposing words together: writing “the healthy sick man,” for example, doesn’t mean anything, unless maybe it’s placed into a very specific context. An oxymoron should produce new meaning on its own.

7. Word Play Examples: Palindrome

The palindrome is a word play device not often employed in literature, but it is language at its most entertaining, and can provide interesting challenges to the daring poet or storyteller.

A palindrome is a word or phrase that is spelled the exact same forwards and backwards (excluding spaces). The word “racecar,” for example, is spelled the same in both directions. So is the phrase “Able was I ere I saw Elba.” So is the sentence “A man, a plan, a canal, Panama.”

The longer a palindrome gets, the less likely it is to make sense. Take, for example, the poem “Dammit I’m Mad” by Demetri Martin. It’s a perfect palindrome, but, although there are some striking examples of language (for example, “A hymn I plug, deified as a sign in ruby ash”), much of the word choice is nonsensical.

Because of this, there are also palindromes that occur at the line-level. Meaning, the words cannot be read forwards and backwards, but the lines of a poem are the same forwards and backwards. The poem “Doppelganger” by James A. Lindon is an example.

Want to challenge yourself? Write a palindrome that tells a cohesive story. You’ll be playing with both the spellings of words and with the meanings that arise from unconventional word choice. Good luck!

8. Word Play Examples: Paraprosdokian

A paraprosdokian is a play on words where the writer diverts from the expected ending of a sentence. In other words, the writer starts a sentence with a predictable ending, but then supplies a new, unexpected ending that complicates the original meanings of the words and surprises the reader.

Here’s an example sentence: “Is there anything that mankind can’t accomplish? We’ve been to the moon, eradicated polio, and made grapes that taste like cotton candy.” This last clause is a paraprosdokian: the reader expects the list to contain great, life-altering achievements, but ending the list with something a bit more trivial, like cotton candy grapes, is a humorous and unexpected twist.

With the paraprosdokian, writers contort the expected endings of sentences to create surprising juxtapositions, playing with both words and sentence structures. Here are a few literary examples, with the paraprosdokian in bold:

By the time you swear you’re his,

Shivering and sighing,

And he vows his passion is

Infinite, undying—

Lady, make a note of this:

One of you is lying.

—“Unfortunate Coincidence” by Dorothy Parker

“By the wide lake’s margin I mark’d her lie –The wide, weird lake where the alders sigh –

A young fair thing, with a shy, soft eye;

And I deem’d that her thoughts had flown …

All motionless, all alone.

Then I heard a noise, as of men and boys,

And a boisterous troop drew nigh.

Whither now will retreat those fairy feet?

Where hide till the storm pass by?

On the lake where the alders sigh …

For she was a water-rat.”

—“Shelter” by Charles Stuart Calverley

9. Word Play Examples: Portmanteau

A portmanteau is a word which combines two distinct words in both sound and meaning. “Smog,” for example, is a portmanteau of both “smoke” and “fog,” because both the sounds of the words are combined as well as the definition of each word.

The portmanteau has become a popular marketing tactic in recent years. A portmanteau is also, often, an example of a neologism—a coined word for which new language is necessary to describe new things.

Here are a few portmanteaus that have recently entered the English lexicon:

- Fanzine (fan + magazine)

- Telethon (telephone + marathon)

- Camcorder (camera + recorder)

- Blog (web + log)

- Vlog (video + blog)

- Staycation (stay + vacation)

- Bromance (brother + romance)

- Webinar (web + seminar)

- Hangry (hungry + angry)

- Cosplay (costume + play)

Lewis Carroll popularized the portmanteau, but a work of fiction that’s rife with this word play is Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce. The novel—which is notoriously difficult to read due to its use of foreign words, as well as its disregard for conventional spelling and syntax—has coined portmanteaus like “ethiquetical” (ethical + etiquette), “laysense” (layman + sense), and “fadograph” (fading + photograph).

10. Word Play Examples: Spoonerism

A spoonerism occurs when the initial sounds of two neighboring words are swapped. For instance, the phrase “blushing crow” is a spoonerism of “crushing blow.”

Often, spoonerisms are slips of the tongue. We might confuse our syllables when we speak, which is a natural result of our brains’ relationships to language.

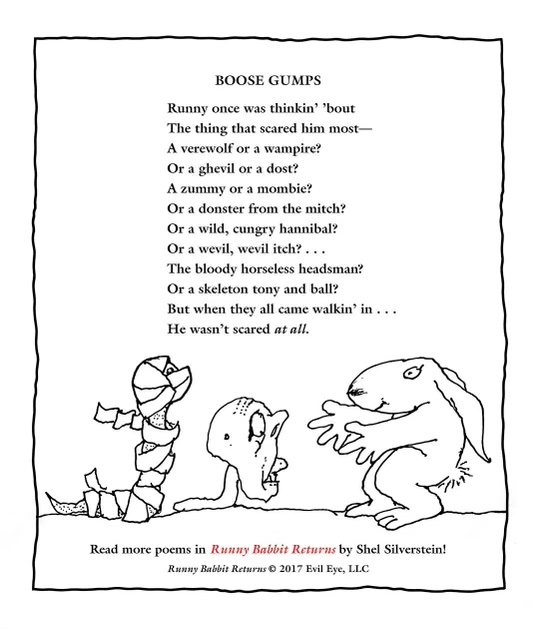

Spoonerisms can be literary examples of a play on words. But they’re also just ways to have fun with language. An example is Shel Silverstein’s posthumous collection of children’s poems Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook.

How to Use a Play on Words in Your Writing

Writers can utilize word play for two different strategies: literary effect, and creative thinking.

When it comes to literary effect, a play on words can surprise, delight, provoke, and entertain the reader. Devices like oxymoron, metalepsis, and kenning offer new, innovative possibilities in language, and a strong example of these devices can move the reader in a way that ordinary language cannot.

Word play can also stimulate your own creativity. If you experiment with language using literary devices, you might stumble upon the following:

- A title for your work.

- Character names.

- Witty dialogue.

- Interesting or provocative description.

- The core idea of a poem or short story.

I’ll give a personal example. Once, in a fiction course, I was struggling to come up with an idea for a short story. A friend and I ended up bouncing words around and came up with the phrase “psychic psychiatrist” (an example of alliteration and polyptoton). Just playing with words like this was enough to inspire me to write a story about exactly that, a psychiatrist who predicts the future for their clients without realizing it.

Titles like The Importance of Being Earnest (a self-referential pun), “Dammit I’m Mad” (palindrome), or Back to the Future (oxymoron) all use word play to frame and guide the story or poem. You might find inspiration for your own work by considering, with careful attention and an appreciation for language, the many possibilities of a play on words.

Experiment with Word Play at Writers.com

The instructors at Writers.com are masters of word play. Not only do we love words, we love to mess with them in surprising and innovative ways. If you want to formulate new ideas for your work, take a look at our upcoming online writing classes, where you’ll receive expert instruction on all the work you write and submit.

Here in the UK, we love a good pun.

You’ll probably notice them in tabloid newspaper headlines, but you might also hear them in everyday conversation, emails, social media, television and any number of other situations in which the speaker wishes to present themselves as comical or witty. They’re not the only prevalent form of wordplay you’ll encounter in the English language though; there are plenty more plays on words that contribute to the richness of the spoken and written language. In this article, we start with an introduction to English puns and wordplay and then take you through some of our favourite examples.

What is a pun?

A pun is a form of wordplay that creates humour through the use of a word or series of words that sound the same but that have two or more possible meanings. Puns often make use of homophones – words that sound the same, and are sometimes spelt the same, but have a different meaning. Puns are generally jokes – but not always; we tend to write “no pun intended” in brackets if we’ve inadvertently chosen our words in a way that could be construed as a pun.

As with any kind of comedy, timing is crucial to the telling of a good pun, and if you’re able to think of one on the spot then you’re bound to get a laugh for your ready wit (it won’t look so good if you take several minutes to think of one, by which time the conversation has moved on!). For example, you might be having a conversation about what you had for breakfast, and your friend tells you that they had boiled eggs for breakfast. You could then retort with “were they eggstraordinary?” – accompanied by a cheeky grin in acknowledgement of the poor joke, of course. More subtle and sophisticated puns don’t modify words in this way, but make use of homophones. For example, in a conversation about cooking fish for a dinner party, one might say “do you think we should scale back on the number of guests?” (playing on a fish’s scales and the expression “scale back”, which means to reduce).

Puns have a slightly poor reputation as forms of humour go, and often elicit a groan from the person on the receiving end of one (though that might just be because they wish they’d thought of something that witty to say). They’re generally considered to be a fairly basic form of humour, though they can also be very sophisticated and funny. Shakespeare was famously pretty big on puns; perhaps, it’s recently been suggested, even more so than previously thought; apparently if you read Shakespeare in an Elizabethan accent, you spot many more puns. These days the tabloids are known for their use of puns in headlines; for example, you might see a headline like “Otter Devastation” in an article detailing the decline of the otter (this plays on the similarities between the words “otter” and “utter”).

Other forms of English wordplay

Puns aren’t the only form of English wordplay – they’re just one of the most popular. Here are some of the other kinds of wordplay you might encounter when you’re learning English, whether in everyday conversation, in the newspapers or in works of English literature.

Acronyms

Acronyms involve making a word using the first letters of a series of other words. This type of wordplay is popular in company names. You might not have known, for example, that the popular budget furniture shop IKEA is actually an acronym; it stands for Ingvar Kamprad, Elmtaryd, Agunnaryd. The first two words are the founder’s name, the third the farm on which he spent his childhood, and the fourth his Swedish hometown. “IKEA” has become such a common word in everyday use that very few people know that it stands for something.

Spoonerisms

We accidentally use spoonerisms all the time, to the point where it’s debateable whether they can legitimately classed as ‘wordplay’, with the connotations of intentional wit that that word entails. A spoonerism – named after a chap named Reverend Spooner, who supposedly fell foul of this slip of the tongue frequently – is when you switch some of the letters between two words. For example, you might say “a slight of fairs” instead of “a flight of stairs”. There’s a joke that relies on Spoonerisms:

Question: Why did the butterfly flutter by?

Answer: Because it saw the dragonfly drink the flagon dry.

While this isn’t exactly a laugh-out-loud witticism, it’s an excellent example of the Spoonerism.

Internet abbreviations

Originally intended to make typing a bit quicker, internet abbreviations have almost become a language in their own right – and some abbreviations have actually entered the spoken English language as well. Perhaps the most famous example is “lol”, which means “laughing out loud”. Some people – particularly among the younger generation – now say “lol” out loud, pronouncing it as “loll” (traditionalists frown upon such behaviour, however, so you’re advised to avoid it if you want to be taken seriously).

Portmanteaus

Take part of one word and its meaning, and combine it with another word and its meaning, and you have a portmanteau. For example, the word “brunch” is a portmanteau that combines “breakfast” and “lunch” to create a word for a meal one has in between, and often instead of, breakfast and lunch. Portmanteaus are very popular with tacky gossip magazines, who use them to refer to celebrity couples, such as “Brangelina” for Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie. They were actually popularised by Lewis Carroll, who used the word “portmanteau” for the first time in Alice Through the Looking-Glass.

Alliteration and onomatopoeia

Alliteration is when you use two or more words in a row beginning with the same letter or using the same sounds, and it tends to be used for emphasis or to make something more memorable. You might hear it in a brand name – such as the Automobile Association (AA) – or newspaper headlines, such as “Persecuted for Praying”. You’ll also see it used in English literature, particularly poetry, as it can be helpful for emphasising a point or creating a particular sound. For instance, a piece of writing about a snake might use words beginning with or containing the letter ‘s’, because, when spoken aloud, this echoes the sound a snake makes when it hisses: “the sly snake slithered stealthily”. A similar concept in wordplay is onomatopoeia, which is where a word sounds like what it describes. For example, animal noises are usually onomatopoeic, such as “oink” to describe the noise a pig makes, “moo” for a cow, “woof” for a dog, and so on. This type of wordplay is also common in poetry, as it means that the poet can create certain sounds to add meaning to what they are writing; a poem about fireworks, for example, might allude to the sounds a firework makes using onomatopoeic words, such as “bang”, “crash”, “fizz”, “whoosh”, and so on.

Jokes, headlines and other witticisms involving puns and wordplay

Finally, we give you some more examples of how cunning use of words can make great jokes and newspaper headlines. Puns are particularly popular in tabloid newspaper headlines because they are eye-catching and memorable, drawing attention to a story that might otherwise not spark the curiosity of a passerby.

“Why did the scarecrow…”

Question: Why did the scarecrow win a Nobel Prize?

Answer: For being outstanding in his field!

This excellent joke makes use of clever wordplay to great comic effect, centered around the word “outstanding”. Clearly Nobel laureates are outstanding in their field of expertise, but you wouldn’t expect a scarecrow would be – these are, after all, simply effigies put in fields to scare birds away from crops. But the word “outstanding”, when separated into two words, takes on a different meaning: the scarecrow is “out standing in his field”, meaning that he is “outside, standing in his field”.

A Queen-based headline

A newspaper headline did the rounds on social media a while ago for its clever play on lyrics from the song Bohemian Rhapsody by the rock band Queen in a story about hikes in rail prices. This is explained below with the original lyrics included in italics beneath the headline words.

Is this the rail price?

Is this the real life?

Is this just fantasy?

Is this just fantasy?

Caught up in land buys

Caught in a landslide,

No escape from bureaucracy!

No escape from reality.

This example illustrates an example of witty wordplay that doesn’t involve homophones, and it’s been hailed as headline writing at its very best!

“I wondered why the baseball…”

The joke goes like this: “I was wondering why the baseball was getting bigger. Then it hit me.” The punchline rests on two meanings of the word “hit”. It can mean physically being hit by something being thrown at you, but it can also mean a thought or realisation suddenly occurring to you.

“Why did the fly fly?”

This one’s a staple of the Christmas cracker and makes use of homophones.

Question: Why did the fly fly?

Answer: Because the spider spied her.

The question exploits two meanings of the word “fly”; it’s a small, irritating buzzing insect, but it’s also a verb – “to fly” – meaning to be airborne. The answer relies on the fact that “spied her” – meaning “saw her” – sounds like “spider”.

“What do you call a small midget fortune teller…”

Here’s a joke that’s both groan-worthy and quite clever wordplay.

Question: What do you call a midget fortune teller who just escaped from prison?

Answer: A small medium at large!

The comedy here hinges on the fact that the answer includes the common sizes of small, medium and large, but they all mean different things. A midget is a small person; another word for a fortune teller is “medium”, as in a psychic medium; and when someone has escaped from prison, they’re described as being “at large”.

“A cigarette lighter”

Three men are on board a boat and they have four cigarettes, but nothing to light them with. What do they do? They throw one overboard… so that they become a cigarette lighter!

The humour here relies on the two different interpretations of “cigarette lighter”. Clearly it’s something used to light a cigarette, but the boat itself can also said to be “a cigarette lighter” in weight, because it has shed the weight of one cigarette.

A long joke to end with

Let’s end with a longer joke that relies on clever wordplay for its punchline. This is a popular joke and comes in a number of versions; this particular rendition comes from here.

“The big chess tournament was taking place at the Plaza in New York. After the first day’s competition, many of the winners were sitting around in the foyer of the hotel talking about their matches and bragging about their wonderful play. After a few drinks they started getting louder and louder until finally, the desk clerk couldn’t take any more and kicked them out.

The next morning the Manager called the clerk into his office and told him there had been many complaints about his being so rude to the hotel guests….instead of kicking them out, he should have just asked them to be less noisy. The clerk responded, “I’m sorry, but if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s chess nuts boasting in an open foyer.”

The punchline at the end – “chess nuts boasting in an open foyer” – is a play on the words of a famous “Christmas Song”, which begins “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire”. “Chess nuts” are people who are “nuts” or crazy about chess; boasting rhymes with roasting; and the “open foyer” that sounds like “open fire” is another word for a reception area. We bet you didn’t realise you could do such clever things with the English language when you first started learning!