Shakespeare’s plays are a canon of approximately 39 dramatic works written by English poet, playwright, and actor William Shakespeare. The exact number of plays—as well as their classifications as tragedy, history, comedy, or otherwise—is a matter of scholarly debate. Shakespeare’s plays are widely regarded as being among the greatest in the English language and are continually performed around the world. The plays have been translated into every major living language.

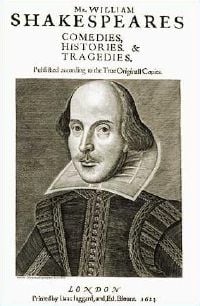

Many of his plays appeared in print as a series of quartos, but approximately half of them remained unpublished until 1623, when the posthumous First Folio was published. The traditional division of his plays into tragedies, comedies, and histories follows the categories used in the First Folio. However, modern criticism has labeled some of these plays «problem plays» that elude easy categorisation, or perhaps purposely break generic conventions, and has introduced the term romances for what scholars believe to be his later comedies.

When Shakespeare first arrived in London in the late 1570s or early 1580s, dramatists writing for London’s new commercial playhouses (such as The Curtain) were combining two strands of dramatic tradition into a new and distinctively Elizabethan synthesis. Previously, the most common forms of popular English theatre were the Tudor morality plays. These plays, generally celebrating piety, use personified moral attributes to urge or instruct the protagonist to choose the virtuous life over Evil. The characters and plot situations are largely symbolic rather than realistic. As a child, Shakespeare would likely have seen this type of play (along with, perhaps, mystery plays and miracle plays).[1]

The other strand of dramatic tradition was classical aesthetic theory. This theory was derived ultimately from Aristotle; in Renaissance England, however, the theory was better known through its Roman interpreters and practitioners. At the universities, plays were staged in a more academic form as Roman closet dramas. These plays, usually performed in Latin, adhered to classical ideas of unity and decorum, but they were also more static, valuing lengthy speeches over physical action. Shakespeare would have learned this theory at grammar school, where Plautus and especially Terence were key parts of the curriculum[2] and were taught in editions with lengthy theoretical introductions.[3]

Theatre and stage setup[edit]

Archaeological excavations on the foundations of the Rose and the Globe in the late twentieth century[4] showed that all London English Renaissance theatres were built around similar general plans. Despite individual differences, the public theatres were three stories high and built around an open space at the center. Usually polygonal in plan to give an overall rounded effect, three levels of inward-facing galleries overlooked the open center into which jutted the stage—essentially a platform surrounded on three sides by the audience, only the rear being restricted for the entrances and exits of the actors and seating for the musicians. The upper level behind the stage could be used as a balcony, as in Romeo and Juliet, or as a position for a character to harangue a crowd, as in Julius Caesar.

Usually built of timber, lath and plaster and with thatched roofs, the early theatres were vulnerable to fire, and gradually were replaced (when necessary) with stronger structures. When the Globe burned down in June 1613, it was rebuilt with a tile roof.

A different model was developed with the Blackfriars Theatre, which came into regular use on a long term basis in 1599. The Blackfriars was small in comparison to the earlier theatres, and roofed rather than open to the sky; it resembled a modern theatre in ways that its predecessors did not.

Elizabethan Shakespeare[edit]

For Shakespeare, as he began to write, both traditions were alive; they were, moreover, filtered through the recent success of the University Wits on the London stage. By the late 16th century, the popularity of morality and academic plays waned as the English Renaissance took hold, and playwrights like Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe revolutionized theatre. Their plays blended the old morality drama with classical theory to produce a new secular form.[5] The new drama combined the rhetorical complexity of the academic play with the bawdy energy of the moralities. However, it was more ambiguous and complex in its meanings, and less concerned with simple allegory. Inspired by this new style, Shakespeare continued these artistic strategies,[6] creating plays that not only resonated on an emotional level with audiences but also explored and debated the basic elements of what it means to be human. What Marlowe and Kyd did for tragedy, John Lyly and George Peele, among others, did for comedy: they offered models of witty dialogue, romantic action, and exotic, often pastoral location that formed the basis of Shakespeare’s comedic mode throughout his career.[7]

Shakespeare’s Elizabethan tragedies (including the history plays with tragic designs, such as Richard II) demonstrate his relative independence from classical models. He takes from Aristotle and Horace the notion of decorum; with few exceptions, he focuses on high-born characters and national affairs as the subject of tragedy. In most other respects, though, the early tragedies are far closer to the spirit and style of moralities. They are episodic, packed with character and incident; they are loosely unified by a theme or character.[8] In this respect, they reflect clearly the influence of Marlowe, particularly of Tamburlaine. Even in his early work, however, Shakespeare generally shows more restraint than Marlowe; he resorts to grandiloquent rhetoric less frequently, and his attitude towards his heroes is more nuanced, and sometimes more sceptical, than Marlowe’s.[9] By the turn of the century, the bombast of Titus Andronicus had vanished, replaced by the subtlety of Hamlet.

In comedy, Shakespeare strayed even further from classical models. The Comedy of Errors, an adaptation of Menaechmi, follows the model of new comedy closely. Shakespeare’s other Elizabethan comedies are more romantic. Like Lyly, he often makes romantic intrigue (a secondary feature in Latin new comedy) the main plot element;[10] even this romantic plot is sometimes given less attention than witty dialogue, deceit, and jests. The «reform of manners», which Horace considered the main function of comedy,[11] survives in such episodes as the gulling of Malvolio.

Jacobean Shakespeare[edit]

Shakespeare reached maturity as a dramatist at the end of Elizabeth’s reign, and in the first years of the reign of James. In these years, he responded to a deep shift in popular tastes, both in subject matter and approach. At the turn of the decade, he responded to the vogue for dramatic satire initiated by the boy players at Blackfriars and St. Paul’s. At the end of the decade, he seems to have attempted to capitalize on the new fashion for tragicomedy,[12] even collaborating with John Fletcher, the writer who had popularized the genre in England.

The influence of younger dramatists such as John Marston and Ben Jonson is seen not only in the problem plays, which dramatize intractable human problems of greed and lust, but also in the darker tone of the Jacobean tragedies.[13] The Marlovian, heroic mode of the Elizabethan tragedies is gone, replaced by a darker vision of heroic natures caught in environments of pervasive corruption. As a sharer in both the Globe and in the King’s Men, Shakespeare never wrote for the boys’ companies; however, his early Jacobean work is markedly influenced by the techniques of the new, satiric dramatists. One play, Troilus and Cressida, may even have been inspired by the War of the Theatres.[14]

Shakespeare’s final plays hark back to his Elizabethan comedies in their use of romantic situation and incident.[15] In these plays, however, the sombre elements that are largely glossed over in the earlier plays are brought to the fore and often rendered dramatically vivid. This change is related to the success of tragicomedies such as Philaster, although the uncertainty of dates makes the nature and direction of the influence unclear. From the evidence of the title-page to The Two Noble Kinsmen and from textual analysis it is believed by some editors that Shakespeare ended his career in collaboration with Fletcher, who succeeded him as house playwright for the King’s Men.[16] These last plays resemble Fletcher’s tragicomedies in their attempt to find a comedic mode capable of dramatising more serious events than had his earlier comedies.

Style[edit]

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth, «drama became the ideal means to capture and convey the diverse interests of the time.»[citation needed] Stories of various genres were enacted for audiences consisting of both the wealthy and educated and the poor and illiterate. Later on, he retired at the height of the Jacobean period, not long before the start of the Thirty Years’ War. His verse style, his choice of subjects, and his stagecraft all bear the marks of both periods.[17] His style changed not only in accordance with his own tastes and developing mastery, but also in accord with the tastes of the audiences for whom he wrote.[18]

While many passages in Shakespeare’s plays are written in prose, he almost always wrote a large proportion of his plays and poems in iambic pentameter. In some of his early works (like Romeo and Juliet), he even added punctuation at the end of these iambic pentameter lines to make the rhythm even stronger.[19] He and many dramatists of this period used the form of blank verse extensively in character dialogue, thus heightening poetic effects.

To end many scenes in his plays he used a rhyming couplet to give a sense of conclusion, or completion.[20] A typical example is provided in Macbeth: as Macbeth leaves the stage to murder Duncan (to the sound of a chiming clock), he says,[21]

Hear it not Duncan, for it is a knell

That summons thee to heaven or to hell.

Shakespeare’s writing (especially his plays) also feature extensive wordplay in which double entendres and rhetorical flourishes are repeatedly used.[22][23] Humour is a key element in all of Shakespeare’s plays. Although a large amount of his comical talent is evident in his comedies, some of the most entertaining scenes and characters are found in tragedies such as Hamlet and histories such as Henry IV, Part 1. Shakespeare’s humour was largely influenced by Plautus.[24]

Soliloquies in plays[edit]

Shakespeare’s plays are also notable for their use of soliloquies, in which a character, apparently alone within the context of the play, makes a speech so that the audience may understand the character’s inner motivations and conflict.[25]

In his book Shakespeare and the History of Soliloquies, James Hirsh defines the convention of a Shakespearean soliloquy in early modern drama. He argues that when a person on the stage speaks to himself or herself, they are characters in a fiction speaking in character; this is an occasion of self-address. Furthermore, Hirsh points out that Shakespearean soliloquies and «asides» are audible in the fiction of the play, bound to be overheard by any other character in the scene unless certain elements confirm that the speech is protected. Therefore, a Renaissance playgoer who was familiar with this dramatic convention would have been alert to Hamlet’s expectation that his soliloquy be overheard by the other characters in the scene. Moreover, Hirsh asserts that in soliloquies in other Shakespearean plays, the speaker is entirely in character within the play’s fiction. Saying that addressing the audience was outmoded by the time Shakespeare was alive, he «acknowledges few occasions when a Shakespearean speech might involve the audience in recognising the simultaneous reality of the stage and the world the stage is representing». Other than 29 speeches delivered by choruses or characters who revert to that condition as epilogues «Hirsh recognizes only three instances of audience address in Shakespeare’s plays, ‘all in very early comedies, in which audience address is introduced specifically to ridicule the practice as antiquated and amateurish.'»[26]

Source material of the plays[edit]

The first edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande, printed in 1577

As was common in the period, Shakespeare based many of his plays on the work of other playwrights and recycled older stories and historical material. His dependence on earlier sources was a natural consequence of the speed at which playwrights of his era wrote; in addition, plays based on already popular stories appear to have been seen as more likely to draw large crowds. There were also aesthetic reasons: Renaissance aesthetic theory took seriously the dictum that tragic plots should be grounded in history. For example, King Lear is probably an adaptation of an older play, King Leir, and the Henriad probably derived from The Famous Victories of Henry V.[27] There is speculation that Hamlet (c. 1601) may be a reworking of an older, lost play (the so-called Ur-Hamlet),[28] but the number of lost plays from this time period makes it impossible to determine that relationship with certainty. (The Ur-Hamlet may in fact have been Shakespeare’s, and was just an earlier and subsequently discarded version.)[27] For plays on historical subjects, Shakespeare relied heavily on two principal texts. Most of the Roman and Greek plays are based on Plutarch’s Parallel Lives (from the 1579 English translation by Sir Thomas North),[29] and the English history plays are indebted to Raphael Holinshed’s 1587 Chronicles. This structure did not apply to comedy, and those of Shakespeare’s plays for which no clear source has been established, such as Love’s Labour’s Lost and The Tempest, are comedies. Even these plays, however, rely heavily on generic commonplaces.

While there is much dispute about the exact chronology of Shakespeare’s plays, there is a general consensus that stylistic groupings largely reflect a chronology of three-phases:

- Histories and comedies – Shakespeare’s earliest plays tended to be adaptations of other playwrights’ works and employed blank verse and little variation in rhythm. However, after the plague forced Shakespeare and his company of actors to leave London for periods between 1592 and 1594, Shakespeare began to use rhymed couplets in his plays, along with more dramatic dialogue. These elements showed up in The Taming of the Shrew and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Almost all of the plays written after the plague hit London are comedies, perhaps reflecting the public’s desire at the time for light-hearted fare. Other comedies from Shakespeare during this period include Much Ado About Nothing, The Merry Wives of Windsor and As You Like It.

- Tragedies – Beginning in 1599 with Julius Caesar, for the next few years, Shakespeare would produce his most famous dramas, including Macbeth, Hamlet, and King Lear. The plays of this period address issues such as betrayal, murder, lust, power and egoism.

- Late romances – These plays romances, including Pericles, Prince of Tyre, Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest, are so called because they bear similarities to medieval romance literature. Among the features of these plays are a redemptive plotline with a happy ending, and magic and other fantastic elements.

Canonical plays[edit]

Except where noted, the plays below are listed, for the thirty-six plays included in the First Folio of 1623, according to the order in which they appear there, with two plays that were not included (Pericles, Prince of Tyre and The Two Noble Kinsmen) being added at the end of the list of comedies and Edward III at the end of the list of histories.

Note: Plays marked with LR are now commonly referred to as the «late romances». Plays marked with PP are sometimes referred to as the «problem plays». The three plays marked with FF were not included in the First Folio.

Dramatic collaborations[edit]

Like most playwrights of his period, Shakespeare did not always write alone, and a number of his plays were collaborative, although the exact number is open to debate. Some of the following attributions, such as for The Two Noble Kinsmen, have well-attested contemporary documentation; others, such as for Titus Andronicus, remain more controversial and are dependent on linguistic analysis by modern scholars.

- Cardenio (a lost play or one that survives only as a later adaptation, Double Falsehood) – Contemporaneous reports suggest that Shakespeare collaborated with John Fletcher.

- Cymbeline – The Yale Shakespeare suggests that a collaborator may have been responsible for parts or all of act III, scene 7, and act V, scene 2

- Edward III – Brian Vickers concluded that the play was 40% Shakespeare and 60% Thomas Kyd.

- Henry VI, Part 1 – Some scholars argue that Shakespeare wrote less than 20% of the text.

- Henry VIII – Generally considered a collaboration between Shakespeare and Fletcher.

- Macbeth – Thomas Middleton may have revised this tragedy in 1615 to incorporate extra musical sequences.

- Measure for Measure – May have undergone a light revision by Middleton.

- Pericles, Prince of Tyre – May include work by George Wilkins, either as collaborator, reviser, or revisee.

- Timon of Athens – May have resulted from collaboration between Shakespeare and Middleton.

- Titus Andronicus – May have been written in collaboration with or revised by George Peele.

- The Two Noble Kinsmen – Attributed in 1634 to Fletcher and Shakespeare.

Lost plays[edit]

- Love’s Labour’s Won – A late sixteenth-century writer, Francis Meres, and a bookseller’s list both include this title among Shakespeare’s recent works, but no play of this title has survived. It may have become lost, or it may represent an alternative title of one of the plays listed above, such as Much Ado About Nothing or All’s Well That Ends Well.

- Cardenio – Attributed to William Shakespeare and John Fletcher in a Stationers’ Register entry of 1653 (alongside a number of erroneous attributions), and often believed to have been re-worked from a subplot in Cervantes’ Don Quixote. In 1727, Lewis Theobald produced a play he called Double Falshood, which he claimed to have adapted from three manuscripts of a lost play by Shakespeare that he did not name. Double Falshood does re-work the Cardenio story, but modern scholarship has not established with certainty whether Double Falshood includes fragments of Shakespeare’s lost play.

Plays possibly by Shakespeare[edit]

Note: For a comprehensive account of plays possibly by Shakespeare or in part by Shakespeare, see the separate entry on the Shakespeare apocrypha.

- Arden of Faversham – The middle portion of the play (scenes 4–9) may have been written by Shakespeare.

- Edmund Ironside – Contains numerous words first used by Shakespeare, and, if by him, is perhaps his first play.

- The London Prodigal and A Yorkshire Tragedy – Both plays were published in quarto as works of Shakespeare, in 1605 and 1608, and were included in the Third Folio. However, stylistic analysis considers these attributions unlikely.

- Sir Thomas More – A collaborative work by several playwrights, including Shakespeare. There is a «growing scholarly consensus»[30] that Shakespeare was called in to re-write a contentious scene in the play and that «Hand D» in the surviving manuscript is that of Shakespeare himself.[31]

- The Spanish Tragedy – Additional passages included in the fourth quarto, including the «painter scene», are likely to have been written by him.[32]

Shakespeare and the textual problem[edit]

Unlike his contemporary Ben Jonson, Shakespeare did not have direct involvement in publishing his plays and produced no overall authoritative version of his plays before he died. As a result, the problem of identifying what Shakespeare actually wrote is a major concern for most modern editions.

One of the reasons there are textual problems is that there was no copyright of writings at the time. As a result, Shakespeare and the playing companies he worked with did not distribute scripts of his plays, for fear that the plays would be stolen. This led to bootleg copies of his plays, which were often based on people trying to remember what Shakespeare had actually written.

Textual corruptions also stemming from printers’ errors, misreadings by compositors, or simply wrongly scanned lines from the source material litter the Quartos and the First Folio. Additionally, in an age before standardized spelling, Shakespeare often wrote a word several times in a different spelling, and this may have contributed to some of the transcribers’ confusion. Modern editors have the task of reconstructing Shakespeare’s original words and expurgating errors as far as possible.

In some cases the textual solution presents few difficulties. In the case of Macbeth for example, scholars believe that someone (probably Thomas Middleton) adapted and shortened the original to produce the extant text published in the First Folio, but that remains the only known text of the play. In others the text may have become manifestly corrupt or unreliable (Pericles or Timon of Athens) but no competing version exists. The modern editor can only regularize and correct erroneous readings that have survived into the printed versions.

The textual problem can, however, become rather complicated. Modern scholarship now believes Shakespeare to have modified his plays through the years, sometimes leading to two existing versions of one play. To provide a modern text in such cases, editors must face the choice between the original first version and the later, revised, usually more theatrical version. In the past editors have resolved this problem by conflating the texts to provide what they believe to be a superior Ur-text, but critics now argue that to provide a conflated text would run contrary to Shakespeare’s intentions. In King Lear for example, two independent versions, each with their own textual integrity, exist in the Quarto and the Folio versions. Shakespeare’s changes here extend from the merely local to the structural. Hence the Oxford Shakespeare, published in 1986 (second edition 2005), provides two different versions of the play, each with respectable authority. The problem exists with at least four other Shakespearean plays (Henry IV, Part 1; Hamlet; Troilus and Cressida; and Othello).

Performance history[edit]

The modern reconstruction of the Globe Theatre, in London

During Shakespeare’s lifetime, many of his greatest plays were staged at the Globe Theatre and the Blackfriars Theatre.[33][34][35][36] Shakespeare’s fellow members of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men acted in his plays. Among these actors were Richard Burbage (who played the title role in the first performances of many of Shakespeare’s plays, including Hamlet, Othello, Richard III and King Lear),[37] Richard Cowley (who played Verges in Much Ado About Nothing), William Kempe, (who played Peter in Romeo and Juliet and, possibly, Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and Henry Condell and John Heminges, who are most famous now for collecting and editing the plays of Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623).

Shakespeare’s plays continued to be staged after his death until the Interregnum (1649–1660), when all public stage performances were banned by the Puritan rulers. After the English Restoration, Shakespeare’s plays were performed in playhouses with elaborate scenery and staged with music, dancing, thunder, lightning, wave machines, and fireworks. During this time the texts were «reformed» and «improved» for the stage, an undertaking which has seemed shockingly disrespectful to posterity.

Victorian productions of Shakespeare often sought pictorial effects in «authentic» historical costumes and sets. The staging of the reported sea fights and barge scene in Antony and Cleopatra was one spectacular example.[38] Too often, the result was a loss of pace. Towards the end of the 19th century, William Poel led a reaction against this heavy style. In a series of «Elizabethan» productions on a thrust stage, he paid fresh attention to the structure of the drama. In the early twentieth century, Harley Granville-Barker directed quarto and folio texts with few cuts,[39][38] while Edward Gordon Craig and others called for abstract staging. Both approaches have influenced the variety of Shakespearean production styles seen today.[40]

See also[edit]

- Chronology of Shakespeare’s plays

- Elizabethan era

- List of Shakespearean characters

- Shakespeare on screen

- Shakespeare’s late romances

- The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged)

- Music in the plays of William Shakespeare

- Returning to Shakespeare by Brian Vickers

References[edit]

- ^ Greenblatt 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Baldwin, T. W. (1944). Shakspere’s Small Latine and Less Greek. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 499–532).

- ^ Doran, Madeleine (1954). Endeavors of Art. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 160–171.

- ^ Gurr, pp. 123–131, 142–146.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Bevington, David (1969). From Mankind to Marlowe (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), passim.

- ^ Logan, Robert A. (2006). Shakespeare’s Marlowe Ashgate Publishing, p. 156.

- ^ Dillon 2006, pp. 49–54.

- ^ Ribner, Irving (1957). The English History Play in the Age of Shakespeare. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 12–27.

- ^ Waith, Eugene (1967). The Herculean Hero in Marlowe, Chapman, Shakespeare, and Dryden. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Doran 1954, pp. 220–225.

- ^ Edward Rand (1937). Horace and the Spirit of Comedy. Houston: Rice Institute Press, passim.

- ^ Kirsch, Arthur. Cymbeline and Coterie Dramaturgy

- ^ Foakes, R. A. (1968). Shakespeare: Dark Comedies to Last Plays. London: Routledge. pp. 18–40.

- ^ Campbell, O. J. (1938). Comicall Satyre and Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida. San Marino: Huntington Library. passim.

- ^ David Young (1972). The Heart’s Forest: A Study of Shakespeare’s Pastoral Plays. New Haven: Yale University Press, 130ff.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (2005). Shakespeare: The Biography. London: Chatto and Windus. pp. 472–474. ISBN 1-85619-726-3.

- ^ Wilson, F. P. (1945). Elizabethan and Jacobean. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 26.

- ^ Bentley, G. E. «The Profession of Dramatist in Shakespeare’s Time», Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115 (1971), 481.

- ^ Introduction to Hamlet by William Shakespeare, Barron’s Educational Series, 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Meagher, John C. (2003). Pursuing Shakespeare’s Dramaturgy: Some Contexts, Resources, and Strategies in His Playmaking. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0838639931.

- ^ Macbeth 2.1/76–77, Folger Shakespeare Library

- ^ Mahood, Molly Maureen (1988). Shakespeare’s Wordplay. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 9780415036993.

- ^ «Hamlet’s Puns and Paradoxes». Shakespeare Navigators. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ «Humor in Shakespeare’s Plays». Shakespeare’s World and Work. Ed. John F. Andrews. 2001. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- ^ Clemen, Wolfgang H. (1987). Shakespeare’s Soliloquies. translated by Charity S. Stokes, Routledge, p. 11.

- ^ Maurer, Margaret (2005). «Review: Shakespeare and the History of Soliloquies». Shakespeare Quarterly. 56 (4): 504. doi:10.1353/shq.2006.0027. S2CID 191491239.

- ^ a b «Shakespeare’s sources», Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Welsh, Alexander (2001). Hamlet in his Modern Guises. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 3

- ^ Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. Accessed 23 October 2005.

- ^ Woudhuysen, Henry (2010). «Shakespeare’s writing, from manuscript to print». In de Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley (eds.). The New Cambridge companion to Shakespeare (2 ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-521-88632-1.

- ^ Woudhuysen 2010, p. 70.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (12 August 2013). «Further Proof of Shakespeare’s Hand in ‘The Spanish Tragedy’«. The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Editor’s preface to A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare, Simon and Schuster, 2004, p. xl

- ^ Foakes 1968, 6.

- ^ Nagler, A. M. (1958). Shakespeare’s Stage. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 7. ISBN 0-300-02689-7

- ^ Shapiro, 131–132.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Ringler, William Jr. (1997). «Shakespeare and His Actors: Some Remarks on King Lear» from Lear from Study to Stage: Essays in Criticism edited by James Ogden and Arthur Hawley Scouten, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, p. 127.

- ^ a b Halpern, Richard (1997). Shakespeare Among the Moderns. New York: Cornell University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-8014-8418-9.

- ^ Griffiths, Trevor R. (ed.) (1996). A Midsummer Night’s Dream. William Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; introduction, 2, 38–39. ISBN 0-521-57565-6.

- ^ Bristol, Michael, and Kathleen McLuskie (eds.). Shakespeare and Modern Theatre: The Performance of Modernity. London; New York: Routledge; Introduction, 5–6. ISBN 0-415-21984-1.

Sources[edit]

- Dillon, Janette (2006). «Elizabethan comedy». In Leggatt, Alexander (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespearean Comedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–63. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521770440.004. ISBN 978-0511998577.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (2005). Will in The World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0712600981.

Further reading[edit]

- Maric, Jasminka, Filozofija u Hamletu, Alfa BK Univerzitet, Belgrade, 2015.

- Maric, Jasminka, Philosophy in Hamlet, author’s edition, Belgrade, 2018.

- Murphy, Andrew (2003). Shakespeare in Print: A History and Chronology of Shakespeare Publishing. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139439466.

External links[edit]

- Complete text of Shakespeare’s plays, listed by genre, with other options including listing of all speeches by each character

- Summaries of Shakespeare’s plays List of all 27 of Shakespeare’s plays with summaries, and images of the plays being performed.

- Complete list of shakespeare’s plays with synopsis

- Narrative and Dramatic Sources of all Shakespeare’s works Also publication years and chronology of Shakespeare’s plays

- «All Shakespeare’s works, Folger Shakespeare Library

- Modern Translations, Study Guides, context and biography of William Shakespeare, of Shakespeare’s plays, and his sonnets

- The Shakespeare Resource Center A directory of Web resources for online Shakespearean study. Includes play synopses, a works timeline, and language resources.

- Shake Sphere Summary and analysis of all the plays, including those of questionable authorship, such as Edward III, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and Cardenio.

- Shakespeare at the British Library – resource including images of original manuscripts, new articles and teaching resources.

This is a comprehensive list of Shakespeare plays, which will act as a ready reference for students, teachers, and Shakespeare lovers. William Shakespeare plays are of diverse nature and consist of comedies, tragedies, and historical plays. I have decided to list these plays in chronological order. Bookmark this Shakespeare timeline for your reference. Each of the Shakespeare plays listed here includes the short summary (synopsis), for further reading you may choose to go through a complete act-wise summary, the link for the complete summary is given along with each play.

Read: Bard’s Biography

Complete list of Shakespeare Plays with short summary Chronologically

Henry VI part 2 (1590-91)

Henry VI part 2 synopsis (Short Summary)

| First Performed | 1590-91 |

| First Printed | 1594 |

Henry VI part II is the first of three Shakespeare plays based on the life and events of King Henry the VI. Set in 15th century England against the backdrop of the famous dynastic ‘war of the roses’ it dramatizes the struggle for the English throne fought between the houses of Lancaster and the house of York.

Opening with the marriage of Henry to Margaret of Anjou, it focuses on the initial turmoil created by several major players to earn favor with the King. However, the central character besides Henry is Richard Plantagenet, the Duke of York who along with his sons, Edward and Richard the II raises an army and plots to overthrow Henry VI and name himself king.

Henry VI part 3 (1590-91)

Henry VI part 3 synopsis (Short Summary)

| First Performed | 1590-91 |

| First Printed | 1594 |

Shakespeare’s fascination for the English Royalty continues in his sequel to Henry VI part 2. With war breathing down his neck, Henry VI tries to strike a bargain with Richard the Duke of York promising to name him heir to the throne. Queen Margaret however disagrees. With the help of Lord Clifford and son Edward, Prince of Wales she wages war on Richard and his army defeating him. With Richard Killed, a new kingmaker emerges in the form of Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick, the initial intermediator between Henry and Richard.

Neville routs Margaret and Clifford’s army, seizes the throne and proclaims Edward the IV, son of Richard as the new King of England.

King Henry VI part 1 (1591-92)

Henry VI part 1 synopsis (Short Summary)

| First Performed | 1591-92 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare’s prequel to the Henry VI trilogy opens with the Young Lancastrian King Henry VI ascending the throne amid turmoil in England for power to the monarchy. Supporters of the two warring houses of Lancaster and York choose red or white roses as symbols of their loyalty. Thus begins the war of the roses.

Adding to his problems, Henry’s armies in France are defeated by French forces led by Joan of Arc.

In a bid for peace, King Henry VI sides with the house of York but confirms his monarchy. He defeats the French and Joan is burnt at the stake. His subsequent marriage to captured French noblewoman Margaret’s’ Anjou sets of a renewed struggle for power to the throne of England.

Richard III (1592-93)

Richard III synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1592-93 |

| First Printed | 1597 |

Richard III (Richard the third) could well qualify as one of the most treacherous of Shakespearean characters. This Shakespeare play is an evil depiction of the scheming villainous crimes of Richard III the Duke of Gloucester and brother of King Edward IV. Richard’s heinous act of taking over the throne is marked by several murders of his own family including Edward the Prince of Wales. After marrying the Prince’s widow Queen Anne, his plotting succeeds in him becoming King.

Richards’s victory is short-lived after his tyrannical succession is ended in defeat by Henry the Earl of Richmond who succeeds Richard as King Henry the VII.

Comedy of Errors (1592-93)

Comedy of Errors synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1592-93 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, Comedy of errors is a typical example of Shakespearean slapstick comedy. It narrates the comical drama of mistaken identities involving two sets of identical twins separated since birth. Both Antipholus of Syracuse and his servant Dromio have corresponding twins in the likeness of brothers with the same names residing in the city of Ephesus where incidentally Syracusans aren’t allowed and the penalty is death.

Comedy of errors unfolds over a series of hilarious events involving wrongful accusations, seductions, beatings and even the arrest of Antipholus of Ephesus under the charge of infidelity, thievery and insanity. The play ends on a happy note with both twins united.

Titus Andronicus (1593-94)

Titus Andronicus synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1593-94 |

| First Printed | 1594 |

Titus Andronicus is Shakespeare’s first Tragedy. Set against the backdrop of the Roman Empire, it never really gained approval in Victorian England, primarily because of its overuse of violent overtones. Titus Andronicus is the story of Roman general Titus and his thirst for bloody revenge against Tamora Queen of Goths may well qualify as the most violent of Shakespeare plays. In what appears to be a treacherous plot of mindless murder and revenge, Shakespeare’s characters namely Titus and Tamora along with their respective supporters revel in plotting a gory and macabre killing spree of each other. The play ends with most central characters dead including Tamora and Titus.

The taming of the shrew (1593-94)

The taming of the shrew synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1593-94 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

As an induction styled play common to Shakespearean literature, the main play of The taming of the shrew is enacted out for the benefit of the introductory character Christopher Sly. Sly is a drunkard who is tricked by a nobleman into believing he descends form nobility.

The ensuing play then unfolds with the comical story of Petruchio of Verona and his courtship and marriage to Katherina. The eldest of two sisters, Katrina is a head strong ill mannered shrew. The comedy depicts Petruchio’s witty but psychological treatment of Katrina in a bid to temper her obstinate behavior. He succeeds by subduing Katharina who ultimately falls in love with her husband and becomes the obedient wife.

The two gentlemen of Verona (1594-95)

The two gentlemen of Verona synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1594-95 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, The two gentlemen of Verona is a classic tale of choice between love and friendship. It portrays the story of two friends Proteus and Valentine who both fall in love with the same woman Silvia daughter of the Duke of Milan. Choosing love over friendship, Proteus betrays Valentine’s plan to elope with Silvia resulting in Valentines banishment from Milan.

Valentine becomes a leader of outlaws in the forest while Silvia attempts to flee and reunite with him. Meanwhile, the second heroine Julia, the fiancée of Proteus disguises herself as a boy to spy on Proteus. The drama ends on a happy note with the two friends resolving their differences with marriage to their respective lovers.

Love’s Labour’s Lost (1594-95)

Love’s Labour’s Lost synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1594-95 |

| First Printed | 1598 |

Shakespeare Play, Love’s Labour’s Lost is totally deceptive of its title. It follows the exploits of the King of Navarre and his three companions who swear to avoid women for three years in a bid to further academic pursuits and good health. Unfortunately their commitment coincides with the visit of the princess of Aquitaine and her ladies.

Their previous commitments forgotten, the men engage in a number of attempts to woo the ladies. A comical mix up follows with letters and messages being delivered to the wrong women.

The untimely demise of the Princess’s father dashes all hopes of marriage for the men who are instructed by the women to engage in several tasks for a year before contemplating marriage.

Romeo and Juliet (1594-95)

Romeo and Juliet synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1594-95 |

| First Printed | 1597 |

Shakespeare play, Romeo and Juliet is well known as one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy. As a popular theme for modern day love stories, the tragic tale records the story of two lovers Romeo of the house of Montague and Juliet from the house of Capulet. With love doomed to end in failure, the lovers woo each other in the wake of a warring feud between the two houses of Montague and Capulet.

A heartwarming tale ensues with the lovers finding ways and means to romance each other until their relationship is exposed. Tragic events of anger and hate end in the death of both lovers which reunite both factions overcome with remorse.

Richard II (1595-96)

Richard II synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1595-96 |

| First Printed | 1597 |

Shakespeare Play, Richard II is a historical play that depicts the common power struggle for the throne and Richard’s attempts to establish his rule. However the central plot commences with Richard II seizing the estates of John of gaunt after his death. His son Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Hereford, attempts to retrieve his inheritance from the King.

While Richard is away fighting the Welsh, Bolingbroke lobbies for supporters among the noblemen and initiates a rebellion. Bolingbroke attempts to make peace with Richard by requesting back his lands and riches to which Richard agrees. In a turn events Richard reluctantly hands over the throne to Bolingbroke who is crowned as King Henry the IV. Richard is sent to the tower where he is soon killed by conspirators.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595-96)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream synopsis (summary)

| First Performed | 1595-96 |

| First Printed | 1600 |

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is Shakespeare’s comedy at it s best. Based upon the quintessential and common theme of love, the play is set in an enchanted forest in a fictional land called Athens. It revolves around the tale of four lovers and an amateur troupe of actors whose lives are encountered and influenced by forest fairies led by their king Oberon and his estranged wife Queen Tatania.

In what appears as its most comical scene, Oberon influences Puck the mischievous sprite to cast a spell on Queen Tatania making her fall in love with one of the minstrels. For good measure, Puck has replaced his head with that of a Donkey’s.

King John (1596-97)

King John synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1596-97 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare Play, King John is a dramatized version of the historical events surrounding the reign of the 12th century monarch of England. This Shakespeare play focuses on King John’s endless war with France supported by a rebellious nephew Arthur and Cardinal Pandolph of the Catholic Church. John is excommunicated by the church who favors the French in its war against John. The English noblemen also side with the French king. The tide soon changes with Arthur’s accidental death and John making his peace with the church. The French, however, continue to wage war against John. But without the support of the church and English nobility, they ultimately relent.

King John, however, does not savor victory as he is poisoned by a monk. His son ascends the throne as King Henry III.

The Merchant of Venice (1596-97)

The Merchant of Venice synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1596-97 |

| First Printed | 1600 |

Shakespeare Play, The Merchant of Venice is a dramatic comedy that focuses more on the antics of its anti-hero a moneylender called Shylock. The story begins with a young merchant Antonio obtaining a loan from Shylock on behalf of his friend Bassanio. Bassanio requires the money to woo a wealthy heiress Portia. Shylock resenting Antonio agrees to lend the money on condition of extracting a pound of his flesh in case of default of payment. The unthinkable happens with Antonio losing his wealth falling in debt to Shylock. Meanwhile, Bassanio is successful in his attempt to win the affections of Portia.

The play climaxes in a court scene where Portia disguised as a lawyer delivers her famous “mercy” speech to win the case against shylock.

Henry IV Part 1 (1597-98)

Henry IV Part 1 synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1597-98 |

| First Printed | 1598 |

Shakespeare Play, Henry IV Part 1 is the second play of Shakespeare’s tetralogy involving Richard II and his successors. This Shakespeare play depicts the problems of King Henry IV in the likes of his wayward philandering son Hal, the Prince of Wales and his rebellious subjects led by Henry Percy nicknamed Hotspur.

Hotspur conjures up support from among sections of the nobility but disunity among the rebels leads to an unsuccessful campaign against the King. Hotspur’s army is defeated at the battle of Shrewsbury. Amidst the turmoil, Prince Hal mends his ways after the firm rebuke from King Henry and slays Hotspur in battle. However, Prince Hal’s allows his friend Falstaff to take credit.

Henry IV Part 2 (1597-98)

Henry IV Part 2 synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1597-98 |

| First Printed | 1600 |

Shakespeare Play, King Henry IV part 2 is an extension of Henry IV part I. Rebellion continues to plague Henry where rebels lead by the Archbishop of York, Lords Mowbray and Hastings wage a second attempt of war against Henry. Meanwhile Falstaff, friend of Prince Hal recruits men to fight for Henry. Henry’s second son Prince John leads the royal army to meet the rebels.

The rebels are tricked into surrendering to Prince John who has them all executed. Out of stress and poor health Henry soon succumbs to his sickness but not before forgiving Prince Hal of his misdeeds. Prince Hal vows to be a good king and ascends the throne as Henry V.

Much Ado About Nothing (1598-99)

Much Ado About Nothing synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1598-99 |

| First Printed | 1600 |

As a love comedy, Much Ado About Nothing portrays a series of comical events surrounding two sets of lovers. Claudio a young Count betrothed to marry his love Hero suspects her of infidelity and insults her at the altar. In a scheme to make Claudio make amends, her father makes him believe that a grief stricken hero has died.

Meanwhile another romantic tryst takes place between the Count Benedick and hero’s cousin Beatrice. Although well matched, they repel each other’s advances . Playing matchmaker, hero’s father brings the two together. A joint marriage is planned where Claudio is made to marry an incognito bride introduced as Beatrice’s cousin. However, she turns out to be none other than his love, the Lady Hero.

Henry V (1598-99)

Henry V synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1598-99 |

| First Printed | 1600 |

This Shakespeare Play is a historical depiction of the monarchy of Henry V revolving around the famous battle of Agincourt. Set in 15th century England, It portrays Henry V a wise and matured King as compared to his erroneous past. Henry renews his claim to the French throne but meets with defiance form France. Henry then prepares for battle traveling to France.

Henry defeats the French in the decisive but bloody battle of Agincourt fought on St Crispin’s day in 1415. While The English and French nobility discuss terms of surrender, Henry woos the French Princess Katherine making her his bride. The play is notably famous for Henry’s pre battle speech coining the epic phrase, “We Few…We Happy Few, We Band of Brothers”.

Julius Caesar (1599-1600)

Julius Caesar synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1599-1600 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

As a historical tragedy, Julius Caesar is part of Shakespeare’s three Roman plays. It dramatizes the life of Julius Caesar who has just returned victorious from his campaign against Pompey. His growing popularity invites resentment from a group of tribunes led by Cassius. Cassius succeeds in recruiting Caesar’s best friend Brutus in a plot to assassinate Caesar. Despite of several warnings from his wife Caliphurnia, Caesar goes to the capitol and is assassinated by the conspirators.

Roman general Mark Anthony also friend to Caesar swears revenge. Along with Octavius Caesar he meets Cassius’ army in battle on the fields of Philippi. Caesar’s ghost appears to Brutus the night before the battle. Mark Antony and Octavius are successful while Brutus and Cassius commit suicide.

As You Like It (1599-1600)

As You Like It synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1599-1600 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare Play, As You Like it is one of Shakespeare’s well known comedies made famous for its speech “All the world’s a stage”.

A senior Duke has been banished to the Forest of Arden by his younger brother. However his daughter Rosalind is allowed to remain but subsequently flees to join her father. Rosalind the main heroine of the play falls in love with Orlando who also flees to Arden from his elder brother’s dominance.

During their exile in the forest Rosalind disguised as a man Ganymede, befriends Orlando as a jest.

Meanwhile, the younger evil duke while marching with an army to the forest repents his ways after a religious encounter with a holy man. He turns to religion and the senior Duke has his title and lands restored.

Twelfth Night (1599-1600)

Twelfth Night synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1599-1600 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, twelfth night is a romantic comedy s about two separated twins Viola and Sebastian who make their way to the kingdom of Illyria. Viola disguises herself as a boy cesario and is employed by the reigning duke Orsino. Orsino’s love interest is the Lady Olivia who will not reciprocate the same as she is mourning the death of her father. Orsino sends viola to woo Lady Olivia on his behalf but Olivia ends up falling for viola who she believes to be Cesario. Meanwhile chance brings Sebastian to the court of Olivia who makes him marry her mistaking him for Viola aka Cesario.

A healthy rigmarole ensues till all is cleared with the duke finding new love with viola. Noteworthy among the characters is the antics of Malvolio and Sir Andrew Aguecheek.

Hamlet (1600-01)

Hamlet synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1600-1601 |

| First Printed | 1603 |

Hamlet is one of the most powerful of Shakespearean tragedies famed for its catch line “to be or not to be’’ part of the popular speech of this play. This Shakespeare play is a classic tale of betrayal, murder and revenge. Prince Hamlet of Denmark is incited by ghostly apparitions of his father who wants revenge against his murderer Claudius. Claudius also his brother seizes both the throne and marries his brother’s wife Gertrude.

The prince’s initial plot to kill Claudius fails with him killing his sweetheart Ophelia’s father instead. When prince is sent to England by Claudius, he chances upon Ophelia’s funeral instead. While Gertrude is killed by drinking poison meant for the prince, Claudius incites a duel between prince and Laertes Ophelia’s brother. Both the men are fatally wounded, but hamlet kills Claudius before succumbing to his injuries.

The Merry Wives of Windsor (1600-01)

The Merry Wives of Windsor synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1600-01 |

| First Printed | 1602 |

Shakespeare play, The Merry Wives of Windsor is a typical farce involving one of Shakespeare most significant characters, john Falstaff. Falstaff is a womanizer and a money grabber who pretends to woo two married women of Windsor Mrs. page and Mrs. Ford

Both women are wise to hid lecherous behavior and play along. Complications arise in the guise of Mr. Ford disguising himself and employing Falstaff to woo his wife and present her to him as proof of her infidelity. However both men are duped by the women on several occasions. Falstaff is led on a merry chase undergoing insult, and humiliation by the women.

This Shakespeare play also depicts the wooing of Anne page which ends in her marriage to her lover Mr. Fenton. In the end Falstaff is forgiven.

Troilus and Cressida (1601-02)

Troilus and Cressida synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1601-1602 |

| First Printed | 1609 |

One of Shakespeare’s most ambiguous and problematic plays, Troilus and Cressida is set against the backdrop of the Trojan-Greek war involving Helen.

Troilus son of Trojan King Priam is in love with Cressida daughter of Calchas a Trojan siding with the Greeks. Troilus and Cressida meet through her uncle Pandorus. In a turn of events, Cressida is sent to the Greek cam in exchange for a Trojan prisoner Antenor.

Meanwhile in the Greek camp trouble constantly brews between Agamemnon and Greek hero Achilles. During the course of battle, Hector son of Priam kills Achilles’ friend Patroclus. An enraged Achilles then slays Hector. Meanwhile Cressida is wooed by Greek prince Diomedes angering Troilus who swears revenge.

All’s Well That Ends Well (1602-03)

All’s Well That Ends Well synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1602-1603 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare Play, All’s well that ends well narrates the tale of Helena daughter of a doctor and a young count Bertram. Helena is in love with Bertram who is unaware of it. Both travel to France where Helena cures the ailing French king. For her reward she is given Bertram as the husband of her choosing but Bertram does not reciprocate her love. Bertram travels to Florence to fight in Tuscan wars.

Helena Travels incognito to Florence to find Bertram trying to seduce a widow’s daughter. She hatches a plan to win Bertram’s love. Back in the kings court Bertram believing Helena to be dead tries to marry someone else only to be apprehended by the King. Helena then reveals herself and Bertram is reconciled to his wife.

Measure for measure (1604-05)

Measure for measure synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1604-1605 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, Measure for measure is a problematic comedy whose main theme is justice, hypocrisy, love and mercy. It narrates the story of Duke Vincentio who wishes to take stock of his kingdom disguised as Friar Lodwick. He leaves the administration in charge of his deputy Angelo who initiates strict laws of morality under the penalty of death.

The main focus of this Shakespeare play revolves around the crime of Claudio who faces the death penalty for sleeping with his intended wife. His sister Isabella a nun tries to intercede on his behalf but is approached by the hypocrite Angelo for sexual favors. Thus begins a series of events overseen by the Duke aka Friar Lodwick. The play ends with Angelo’s guilt revealed. The Duke then proposes marriage to Isabella.

Othello (1604-05)

Othello Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1604-1605 |

| First Printed | 1622 |

Like Shakespeare play Hamlet, Othello is a significant and popular tragedy. Othello is a Moorish captain serving in the Venetian army. Unfortunately for him, he has several enemies the worst of whom is his most trusted ensign Iago. In what unravels as a classic narration of racism, love, betrayal, jealousy and wrongful accusation, Iago hatches a plot to wrongfully accuse his wife Desdemona of infidelity. Inflamed with passion and jealousy an enraged he kills Desdemona.

Iago’s wife Emilia informs Othello of Desdemona’s innocence revealing Iago’s dastardly plot but she to is killed by Iago. He is filled with remorse and in revenge tries to kill Iago but only wounds him. Before he can be arrested he commits suicide.

King Lear (1605-06)

King Lear Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1605-1606 |

| First Printed | 1608 |

King Lear of Britain in an attempt to avoid unrest divides his kingdom between his three daughters, each portion depending on their declaration of loyalty for him. His elder two Reagan and Goneril succeed in his affections by their hypocritical declarations of love. However Cordelia the youngest is unable to do so and is banished by Lear. Cordelia goes on to marry the King of France.

King Lear gradually sinks into manic depression at the indifferent attitude of his two elder daughters’ towards him. In a tragic twist both daughters end up dead as a result of their feuding over the affections of Edmund the bastard son of Gloucester. Edmund in his bid to take over his brother’s property imprisons Lear and executes Cordelia. Lear dies soon after out of remorse.

Macbeth Synopsis (1605-06)

Macbeth Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1605-1606 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, Macbeth is a dramatic representation of the treachery of political ambition and how it can lead to madness. General Macbeth after a victorious battle is prophesied by witches to become king. However the prophesy predicts his friend Banquo’s lineage as his successors.

Influenced By his wife, he murders Duncan the King of Scotland and ascends the throne. Fearing that Banquo suspects him, he orders Banquo to be killed in the forest but his son Fleance escapes. The witches warn him against Macduff the thane of Fife. He orders the killing of Macduff and his family however Macduff isn’t present. Meanwhile hi wife becomes insane with guilt and dies.

In revenge, Macduff and Duncan’s son Malcolm wage war on Macbeth killing him in battle. Malcolm is crowned king.

Antony and Cleopatra (1606-07)

Antony and Cleopatra synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1606-07 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, Antony and Cleopatra narrates the relationship between Mark Antony of Rome and Cleopatra the queen of Egypt. Rome is ruled by the triumvirate of Antony, Lepidus and Octavius caesar. However, Antony spends more time with Cleopatra in Egypt. He returns to Rome to successfully quell rebellion by Pompey after which he marries Octavia, Caesars widowed sister.

He soon returns to Cleopatra enraging Octavius who then declares war on Anthony in a bid to become sole ruler of Rome. Anthony is defeated in battle and accuses Cleopatra of betraying him. Later, thinking Cleopatra to be dead, Anthony mortally wounds himself and subsequently dies in Cleopatra’s arms. Octavius orders Cleopatra to be brought to Rome, but Cleopatra commits suicide by getting bitten by a poisonous Asp.

Coriolanus Synopsis (1607-08)

Coriolanus Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1607-08 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, Coriolanus is the tale of a Roman general whose victories against the Volscians led by Aufidius lead him to the political arena of Rome. However his quick temperament is unbecoming of a politician. He angers easily at the slightest provocation which brings him in disfavor with the people of Rome and he is banished from Rome.

Meanwhile Aufidius and his Volscians rebel against Rome again. Coriolanus sides with Aufidius. The Romans take fright at the alliance and implore his mother Volumnia and his wife Virgilia to ask him to spare Rome. However Coriolanus growing popularity with the Volscians angers Aufidius and a conspiracy is hatched to kill him. Aufidius repents his misdeeds and the Volscians give him a hero’s funeral.

Timon of Athens (1607-08)

Timon of Athens Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1607-1608 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, Timon of Athens is about Timon, who is an Athenian Noblemen. He is extravagant in his lavishness and generosity among his friends. Ultimately he is bankrupt and none of his so called friends help him. At one last party thrown for his friends, Timon instead showers them with stones and water revealing their ingratitude. He then leaves Athens to live in a cave by the sea.

He discovers gold in the cave which he shares with a banished Athenian captain Alcibiades and even bandits. Senators from Athens Implore Timon to return and defend Athens against Alcibiades but Timon refuses. He ultimately wanders off into the wilderness to die but not before writing his own epitaph, read in the end of the play by Alcibiades.

Pericles (1608-09)

Pericles Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1608-1609 |

| First Printed | 1609 |

Shakespeare play, Pericles is a historical play narrating the life of Pericles of Tyre. He has to flee from wrath of Antiochus after solving a riddle that revealed his incestuous relationship with his daughter. He reaches Pentapolis where he marries a noblewoman Thaisa. Returning to Tyre Thaisa appears to die in childbirth. He places her in a chest and puts it overboard whereupon she reaches Ephesus and becomes a nun.

Meanwhile Marina is captured by pirates where she is sold in Mytiline but manages to find honest work. Pericles thinking her dead arrives in Mytilene where marina is introduced to him as a maid. He is overjoyed and is soon reunited with Thaisa after seeing a vision asking him to go to the temple of Diana in Ephesus.

Cymbeline (1609-10)

Cymbeline Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1609-1610 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Cymbeline is the Celtic king of Britain whose sons were styolemn by Belarus after he was banished from court. The play however does not revolve much around him, but rather over the exploits of his daughter Innogen and her suitors posthumous and Cloten her step brother whom she rejects. Her step mother the queen attempts to poison her.

Amidst events surrounding the Roman attack of Britain in which the British emerge victorious. Cymbeline meets with Belarus who has been instrumental in the defense of Britain along with his two adopted sons Guiderius and Aviragus. They are revealed to him as his sons. Meanwhile Innogen dressed a page in the service of Lucius the Roman representative is given to him who reveals herself as Innogen.

The winter’s Tale (1610-11)

The winter’s Tale Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1610-1611 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Polixenes, king of Bohemia invites the wrath of his friend king leontes of Sicily who suspects Polixenes of infidelity with his wife Hermione. Polixenes fleas Sicily where Leontes imprisons his wife and exiles her newborn daughter who is raised by a shepherd in Bohemia. Later thinking Hermione to be dead, he repents his misdeeds.

Hermione’s daughter grows up as Perdita a shepherd girl and is wooed by Prince Florizel Polixenes son. Polixenes disapproves and the lovers elope to Sicily. They are followed by the shepherds and Polixenes. This Shakespeare play climaxes with characters appearing in Leontes court where Perditas true identity is revealed. Leontes is reunited with Hermione.

The Tempest (1611-12)

The Tempest Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1611-1612 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, The Tempest narrates the tale of Prospero, former Duke of Milan and his daughter Miranda who was usurped by his Brother Antonio and banished to an island. Prospero with his books of magic lives on the island with a savage creature Caliban and Ariel a sprite as his slaves.

Prospero watches a shipwreck from the island whose passengers were none other than Antonio the usurper, Alonso the king of Naples, his brother Sebastian and his son Prince Ferdinand.The group is washed ashore on the same island. In a series of bemusing events Ferdinand falls in love with Miranda and is married to her with Prospero’s blessings. The entire casts of characters are then brought together and Prospero’s identity is revealed. The play ends in reconciliation and celebration.

Henry VIII [8th] (1612-13)

Henry VIII (8th) Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1612-1613 |

| First Printed | 1623 |

Shakespeare play, Henry VIII or Henry 8th, is a historical play depicting King Henry’s courtship of Anne Boleyn and his subsequent separation from the Catholic Church.

Cardinal Wosley head of the church had earlier instigated the execution of Henry’s Father the duke of Buckingham. Henry Married Katherine for 20 years wants a divorce so that he can marry her lady in waiting Anne Boleyn. Both the pope and Cardinal Wosley delay permission causing Henry to initiate the divorce and marry Anne disregarding the Pope. Both Wosley and Katherine subsequently die. Wosley’s secretary is executed for attempting to murder the new Archbishop of Canterbury. Anne gives birth to a daughter Elizabeth who is prophesied to be a great Queen of England.

The two noble kinsmen (1612-13)

The two noble kinsmen Synopsis (short summary)

| First Performed | 1612-1613 |

| First Printed | 1634 |

Shakespeare play, The two noble kinsmen can also be called a tragicomedy involving the Duke Theseus of Athens, and two cousins Palamon and Arcite. Theseus marries the Amazonian queen Hippolyta and helps three queens wage war on Creon the king of Thebes.

Thebes helped by the two cousins is defeated. The cousins are imprisoned in Athens where they both fall in love with Hippolyta’s sister Emilia. After escaping they constantly feud with each other to win her affection. Theseus makes them joust each other for Emilia’s hand in marriage. After praying to the gods, the joust ends in victory for Arcite. Palamon faces death for losing but Arcite is accidentally killed after falling from his horse. His death wish is for Emilia to marry his cousin.

External Links about Shakespeare Plays for further reading:

- Shakespear-online: Complete Shakespeare Plays list with short notes.

- Britannica: Shakespeare Plays and poems.

- NosweatShakespear: Shakespeare Plays Resources.

- Royal Shakespear Company: Shakespeare Plays by genre.

- Wikipedia: About Shakespeare Plays, theatre and stage setup.

Shakespeare’s plays portray recognisable people in situations that we can all relate to — including love, marriage, death, mourning, guilt, the need to make difficult choices, separation, reunion and reconciliation. They do so with great humanity, tolerance, and wisdom. They help us to understand what it is to be human, and to cope with the problems of being so.

Click on a play to read a full synopsis.

Because Shakespeare’s plays are written to be acted, they are constantly fresh and can be adapted to the place and time they are performed. Their language is wonderfully expressive and powerful, and although it may sometimes seem hard to understand in reading, actors can bring it to vivid life for us. The plays provide actors with some of the most challenging and rewarding roles ever written. They are both entertaining and moving.

In the first Folio of 1623, the earliest edition of Shakespeare’s collected plays, they are divided into Comedies, Histories and Tragedies. Over time, these have been further divided into Romances which include The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, and Pericles. The term ‘Problem Plays’ has been used to include plays as apparently diverse as Measure for Measure, Hamlet, All’s Well that Ends Well and Troilus and Cressida.

In his history plays, Shakespeare sometimes had the same character appear over and over. For example, the character ‘Bardolph’ appears in the the most plays of any characters, including Henry IV Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, Henry V, and The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Scholars of Elizabethan drama believe that William Shakespeare wrote at least 38 plays between 1590 and 1612. These dramatic works encompass a wide range of subjects and styles, from the playful «A Midsummer Night’s Dream» to the gloomy «Macbeth.» Shakespeare’s plays can be roughly divided into three genres—comedies, histories, and tragedies—though some works, such as «The Tempest» and «The Winter’s Tale,» straddle the boundaries between these categories.

Shakespeare’s first play is generally believed to be «Henry VI Part I,» a history play about English politics in the years leading up to the Wars of the Roses. The play was possibly a collaboration between Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, another Elizabethan dramatist who is best known for his tragedy «Doctor Faustus.» Shakespeare’s last play is believed to be «The Two Noble Kinsmen,» a tragicomedy co-written with John Fletcher in 1613, three years before Shakespeare’s death.

Shakespeare’s Plays in Chronological Order

The exact order of the composition and performances of Shakespeare’s plays is difficult to prove—and therefore often disputed. The dates listed below are approximate and based on the general consensus of when the plays were first performed:

- «Henry VI Part I» (1589–1590)

- «Henry VI Part II» (1590–1591)

- «Henry VI Part III» (1590–1591)

- «Richard III» (1592–1593)

- «The Comedy of Errors» (1592–1593)

- «Titus Andronicus» (1593–1594)

- «The Taming of the Shrew» (1593–1594)

- «The Two Gentlemen of Verona» (1594–1595)

- «Love’s Labour’s Lost» (1594–1595)

- «Romeo and Juliet» (1594–1595)

- «Richard II» (1595–1596)

- «A Midsummer Night’s Dream» (1595–1596)

- «King John» (1596–1597)

- «The Merchant of Venice» (1596–1597)

- «Henry IV Part I» (1597–1598)

- «Henry IV Part II» (1597–1598)

- «Much Ado About Nothing» (1598–1599)

- «Henry V» (1598–1599)

- «Julius Caesar» (1599–1600)

- «As You Like It» (1599–1600)

- «Twelfth Night» (1599–1600)

- «Hamlet» (1600–1601)

- «The Merry Wives of Windsor» (1600–1601)

- «Troilus and Cressida» (1601–1602)

- «All’s Well That Ends Well» (1602–1603)

- «Measure for Measure» (1604–1605)

- «Othello» (1604–1605)

- «King Lear» (1605–1606)

- «Macbeth» (1605–1606)

- «Antony and Cleopatra» (1606–1607)

- «Coriolanus» (1607–1608)

- «Timon of Athens» (1607–1608)

- «Pericles» (1608–1609)

- «Cymbeline» (1609–1610)

- «The Winter’s Tale» (1610–1611)

- «The Tempest» (1611–1612)

- «Henry VIII» (1612–1613)

- «The Two Noble Kinsmen» (1612–1613)

Dating the Plays

The chronology of Shakespeare’s plays remains a matter of some scholarly debate. Current consensus is based on a constellation of different data points, including publication information (e.g. dates taken from title pages), known performance dates, and information from contemporary diaries and other records. Though each play can be assigned a narrow date range, it is impossible to know exactly in which year any one of Shakespeare’s plays was composed. Even when exact performance dates are known, nothing conclusive can be said about when each play was written.

Further complicating the matter is the fact that many of Shakespeare’s plays exist in multiple editions, making it even more difficult to determine when the authoritative versions were completed. For example, there are several surviving versions of «Hamlet,» three of which were printed in the First Quarto, Second Quarto, and First Folio. The version printed in the Second Quarto is the longest version of «Hamlet,» though it does not include over 50 lines that appear in the First Folio version. Modern scholarly editions of the play contain material from multiple sources.

Authorship Controversy

Another controversial question regarding Shakespeare’s bibliography is whether the Bard actually authored all of the plays assigned to his name. In the 19th century, a number of literary historians popularized the so-called «anti-Stratfordian theory,» which held that Shakespeare’s plays were actually the work of Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, or possibly a group of playwrights. Subsequent scholars, however, have dismissed this theory, and the current consensus is that Shakespeare—the man born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564—did, in fact, write all of the plays that bear his name.

Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that some of Shakespeare’s plays were collaborations. In 2016, a group of scholars performed an analysis of all three parts of «Henry VI» and came to the conclusion that the play does include the work of Christopher Marlowe. Future editions of the play published by Oxford University Press will credit Marlowe as co-author.

Another play, «The Two Noble Kinsmen,» was co-written with John Fletcher, who also worked with Shakespeare on the lost play «Cardenio.» Some scholars believe that Shakespeare may have also collaborated with George Peele, an English dramatist and poet; George Wilkins, an English dramatist and inn-keeper; and Thomas Middleton, a successful author of numerous stage works, including comedies, tragedies, and pageants.

The famous Chandos portrait that is believed to be of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare (Baptized April 26, 1564 – April 23, 1616) was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s preeminent dramatist. His surviving works consist of 38 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several shorter poems. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.

Shakespeare was born and lived in Stratford-upon-Avon. From 1585 until 1592 he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part owner of the acting company the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare’s private life survive, and there has been considerable speculation about his life and prodigious literary achievements.

Shakespeare’s early plays were mainly comedies and histories, genres he raised to the peak of sophistication by the end of the sixteenth century. In his following phase he wrote mainly tragedies, including Hamlet, King Lear, and Macbeth, Othello. The plays are often regarded as the summit of Shakespeare’s art and among the greatest tragedies ever written. In 1623, two of his former theatrical colleagues published the First Folio, a collected edition of his dramatic works that included all but two of the plays now recognized as Shakespeare’s.

Shakespeare’s canon has achieved a unique standing in Western literature, amounting to a humanistic scripture. His insight in human character and motivation and his luminous, boundary-defying diction have influenced writers for centuries. Some of the more notable authors and poets so influenced are Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Charles Dickens, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Herman Melville, and William Faulkner. According to Harold Bloom, Shakespeare «has been universally judged to be a more adequate representer of the universe of fact than anyone else, before or since.»[1]

Shakespeare lived during the so-called Elizabethan Settlement in which relatively moderate English Protestantism gained ascendancy. Throughout his works he explored themes of conscience, mercy, guilt, temptation, forgiveness, and the afterlife. The poet’s own religious leanings, however, are much debated. Shakespeare’s universe is governed by a recognizably Christian moral order, yet threatened and often brought to grief by tragic flaws seemingly embedded in human nature much like the heroes of Greek tragedies.

He was a respected poet and playwright in his own day, but Shakespeare’s reputation did not rise to its present heights until the nineteenth century. The Romantics, in particular, acclaimed his genius, and in the twentieth century, his work was repeatedly adopted and rediscovered by new movements in scholarship and performance. His plays remain highly popular today and are consistently performed and reinterpreted in diverse cultural and political contexts throughout the world.

Life

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England, in April 1564, the son of John Shakespeare, a successful tradesman and alderman, and of Mary Arden, a daughter of the gentry. Shakespeare’s baptismal record dates to April 26 of that year.

Shakespeare’s home in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Because baptisms were performed within a few days of birth, tradition has settled on April 23 as his birthday. This date is convenient as Shakespeare died on the same day in 1616.

As the son of a prominent town official, Shakespeare was entitled to attend King Edward VI Grammar school in central Stratford, which may have provided an intensive education in Latin grammar and literature. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway on November 28, 1582 at Temple Grafton, near Stratford. Hathaway, who was 25, was seven years his senior. Two neighbors of Anne posted bond that there were no impediments to the marriage. There was some haste in arranging the ceremony, presumably as Anne was three months pregnant.

After his marriage, Shakespeare left few traces in the historical record until he appeared on the London theatrical scene. The late 1580s are known as Shakespeare’s «Lost Years» because little evidence has survived to show exactly where he was or why he left Stratford for London. On May 26, 1583, Shakespeare’s first child, Susannah, was baptized at Stratford. Twin children, a son, Hamnet, and a daughter, Judith, were baptized on February 2, 1585. Hamnet died in 1596, Susanna in 1649, and Judith in 1662.

London and theatrical career

It is not known exactly when Shakespeare began writing, but contemporary allusions and records of performances show that several of his plays were on the London stage by 1592. He was well enough known in London by then to be attacked in print by the playwright Robert Greene:

…there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapped in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.[2]

Scholars differ on the exact meaning of these words, but most agree that Greene is accusing Shakespeare of reaching above his rank in trying to match university-educated writers, such as Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe and Greene himself.[3] The italicized line parodying the phrase «Oh, tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide» from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, part 3, along with the pun «Shake-scene,» identifies Shakespeare as Greene’s target.

|

«All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players: they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts…» |

| As You Like It, Act II, Scene 7, 139–42. |