It goes without saying that writers are drawn to language, but because we love words so much, the English language is filled with word play. By interrogating the complexities of language—homophones, homographs, words with multiple meanings, sentence structures, etc.—writers can explore new possibilities in their work through a play on words.

It’s easiest to employ word play in poetry, given how many linguistic possibilities there are in poetry that are harder to achieve in prose. Nonetheless, the devices listed in this article apply to writers of all genres, styles, and forms of writing.

After examining different word play examples—such as portmanteaus, malapropisms, and oxymorons—we’ll look at opportunities for how these devices can propel your writing. But first, let’s establish what we mean when we’re talking about a play on words.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Wordplay Definition

Word play, also written as wordplay, word-play, or a play on words, is when a writer experiments with the sound, meaning, and/or construction of words to produce new and interesting meanings. In other words, the writer is twisting language to say something unexpected, with the intent of entertaining or provoking the reader.

Wordplay definition: Experimentation with the sounds, definitions, and/or constructions of words to produce new and interesting meanings.

It should come as no surprise that many word play examples were written by Shakespeare. One such example comes from Hamlet. Some time after Polonius is killed, Hamlet’s uncle, Claudius, asks him where Polonius is. The below exchange occurs:

KING CLAUDIUS

Now, Hamlet, where’s Polonius?

HAMLET

At supper.

KING CLAUDIUS

At supper! where?

HAMLET

Not where he eats, but where he is eaten: a certain

convocation of politic worms are e’en at him. Your

worm is your only emperor for diet: we fat all

creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for

maggots: your fat king and your lean beggar is but

variable service, two dishes, but to one table:

that’s the end.

The line “Not where he eats, but where he is eaten” is a play on words, drawing the audience’s attention to Polonius’ death. He is not eating, but being consumed by the worms. This play on the meaning of “eat” utilizes the verb’s multiple definitions—to consume versus to decompose. (It is also an example of synchysis, and of polyptoton, a type of repetition device.)

The most common of word play examples is the pun. A pun directly plays with the sounds and meanings of words to create new and surprising sentences. For example, “The incredulous cat said you’ve got to be kitten me right meow!” puns on the words “kidding” (kitten) and “now” (meow).

To learn more about puns, check out our article on Pun Examples in Literature. Some of the play on words examples in this article can also count as puns, but because we’ve covered puns in a previous blog, this article covers different and surprising possibilities for twisting and torturing language.

Examples of a Play on Words: 10 Literary Devices

Word play isn’t just a way to have fun with language, it’s also a means of creating new and surprising meanings. By experimenting with the possibilities of sound and meaning, writers can create new ideas that traditional language fails to encompass.

Let’s see word play in action. The following examples of a play on words all come from published works of literature.

1. Word Play Examples: Anthimeria

Anthimeria is a type of word play in which a word is employed using a different part of speech than what is typically associated with that word. (For reference, the parts of speech are: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, articles, interjections, conjunctions, and prepositions.)

Most commonly, a writer using anthimeria will make a verb a noun (nominalization), or make a noun a verb (verbification). It would be much harder to employ this device using other parts of speech: using an adjective as a pronoun, for example, would be difficult to read, even for the reader familiar with anthimeria.

Here are some word play examples using anthimeria:

Nouns to Verbs

The thunder would not peace at my bidding.

—From King Lear, (IV, vi.) by Shakespeare

The word “peace” is being used as a verb, meaning “to calm down.” Many anthimeria examples come to us from Shakespare, in part because of his genius with language, and in part because he needed to use certain words that would preserve the meter of his verse.

“I’ll unhair thy head.”

—From Antony and Cleopatra (II, v.) by Shakespeare

Of course, “unhair” isn’t a word at all. But, it’s using “hair” as a verb, and then using the opposite of that verb, to express scalping someone’s hair off.

Up from my cabin, My sea-gown scarf’d about me, in the dark

Groped I to find out them; had my desire.

—From Hamlet, (V, ii.) by Shakespeare

Shakespeare is using “scarf” as a verb, meaning “to wrap around.” Nowadays, the use of “scarf” as a verb is recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary, but at the time, this was a very new usage of the word.

Verbs to Nouns

It’s difficult to find examples of nominalization in literature, mostly because it’s not a wise decision in terms of writing style. Verbs are the strongest parts of speech: they provide the action of your sentences, and can also provide necessary description and characterization in far fewer words than nouns and adjectives can. Using a verb as a noun only hampers the power of that verb.

Nonetheless, we use verbs as nouns all the time in everyday conversation. If you “hashtag” something on social media, you’re using the noun hashtag as a verb. Or, if you “need a good drink,” you’re noun-ing the verb “drink.” Often, nouns become acceptable dictionary entries for verbs because of the repeated use of nominalizations in everyday speech.

Nouns and Verbs to Adjectives

“The parishioners about here,” continued Mrs. Day, not looking at any living being, but snatching up the brown delf tea-things, “are the laziest, gossipest, poachest, jailest set of any ever I came among.”

—From Under the Greenwood Tree by Thomas Hardy

The words “gossipest, poachest, jailest” might seem silly or immature. But, they’re fun and striking uses of language, and they help characterize Mrs. Day through dialogue.

“I’ll get you, my pretty.”

—From The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

By using the adjective “pretty” as a noun, the witch’s use of anthimeria in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz strikes a chilling note: it’s both pejorative and suggests that the witch could own Dorothy’s beauty.

Anthimeria isn’t just a form of language play, it’s also a means of forging neologisms, which eventually enter the English lexicon. Many words began as anthimerias. For example, the word “typing” used to be a new word, as people didn’t “employ type” until the invention of typing devices, like typewriters. The word “ceiling” comes from an antiquated word “ceil,” meaning sky: “ceiling” means to cover over something, and that verb eventually became the noun we use today.

2. Word Play Examples: Double Entendre

A double entendre is a form of word play in which a word or phrase is used ambiguously, meaning the reader can interpret it in multiple ways. A double entendre usually has a literal meaning and a figurative meaning, with both meanings interacting with each other in some surprising or unusual way.

In everyday speech, the double entendre is often employed sexually. Indeed, writers often use the device lasciviously, and bawdry bards like Shakespeare won’t hesitate when it comes to dirty jokes.

Nonetheless, here a few examples of double entendre that are a little more PG:

“Marriage is a fine institution, but I’m not ready for an institution.”

—Mae West, quoted in The 2,548 Best Things Anybody Ever Said by Robert Byrne

The repeated use of “institution” suggests a double meaning. While marriage is, literally, an institution, West is also suggesting that marriage is an institution in a different sense—like a prison or a psychiatric hospital, one that she’s not ready to commit to.

“What ails you, Polyphemus,” said they, “that you make such a noise, breaking the stillness of the night, and preventing us from being able to sleep? Surely no man is carrying off your sheep? Surely no man is trying to kill you either by fraud or by force?”But Polyphemus shouted to them from inside the cave, “No man is killing me by fraud; no man is killing me by force.”

“Then,” said they, “if no man is attacking you, you must be ill; when Jove makes people ill, there is no help for it, and you had better pray to your father Neptune.”

—Odyssey by Homer

In Homer’s Odyssey, the hero, Odysseus, tells the cyclops Polyphemus that his name is “no man.” Then, when Odysseus blinds Polyphemus, the cyclops is enraged and tells people that “no man” did this, suggesting that his blindness is an affliction from the gods. In this instance, Polyphemus means one thing but communicates another, causing humorous ambiguity for the audience.

On the contrary, Aunt Augusta, I’ve now realized for the first time in my life the vital importance of being Earnest.

—The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People by Oscar Wilde

In Oscar Wilde’s play, the protagonist Jack Worthing leads a double life: to his lover in the countryside, he’s Jack, while he’s Ernest to his lover in the city. The play follows this character’s deceptions, as well as his realization of the necessity of being true to himself. Thus, in this final line of the play, Jack realizes the importance of being “earnest,” a pun and double entendre on “Ernest.”

3. Word Play Examples: Kenning

The kenning is a type of metaphor that was popular among medieval poets. It is a phrase, usually two nouns, that describes something figuratively, often using words only somewhat related to the object being described.

If you’ve read Beowulf, you’ve seen the kenning in action—and you know that, in translation, some kennings are easier understood than others. For example, the ocean is often described as the “whale path,” which makes sense. But a dragon is described as a “mound keeper,” and if you don’t know that dragons in literature tend to hoard piles of gold, it might be harder to understand this kenning.

A kenning is constructed with a “base word” and a “determinant.” The base word has a metaphoric relationship with the object being described, and the determinant modifies the base word. So, in the kenning “whale path,” the “path” is the base word, as it’s a metaphor for the sea. “Whale” acts as a determinant, cluing the reader towards the water.

The kenning is a play on words because it uses marginally related nouns to describe things in new and exciting language. Here are a few examples:

Kenning In Beowulf

At some point in the text of Beowulf, the following kennings occur:

- Battle shirt — armor

- Battle sweat — blood

- Earth hall — burial mound

- Helmet bearer — warrior

- Raven harvest — corpse

- Ring giver — king

- Sail road — the sea

- Sea cloth — sail

- Sky candle — the sun

- Sword sleep — death

Don’t be too surprised by all of the references to fighting and death. Most of Beowulf is a series of battles, and given that the story developed across centuries of Old English, much of the epic poem explores God, glory, and victory.

Kenning Elsewhere in Literature

The majority of kennings come from Old English poetry, though some contemporary poets also employ the device in their work. Here are a few more kenning word play examples.

So the earth-stepper spoke, mindful of hardships,

of fierce slaughter, the fall of kin:

Oft must I, alone, the hour before dawn

lament my care. Among the living

none now remains to whom I dare

my inmost thought clearly reveal.

I know it for truth: it is in a warrior

noble strength to bind fast his spirit,

guard his wealth-chamber, think what he will.

—”The Wanderer” (Anonymous)

“The Wanderer” is a poem anonymously written and preserved in a codex called The Exeter Book, a manuscript from the late 900s. It contains approximately ⅙ of the Old English poetry we know about today. In this poem, an “earth-stepper” is a person, and a “wealth-chamber” is the wanderer’s mind or heart—wherever it is that he stores his immaterial virtues.

No, they’re sapped and now-swept as my sea-wolf’s love-cry.

—from “Cuil Cliffs” by Ian Crockatt

Ian Crockatt is a contemporary poet and translator from Scotland, and his work with Old Norse poetry certainly influences his own poems. “Sea wolf” is a kenning for “sailor,” and a “love cry” is a love poem.

There is a singer everyone has heard,Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again.

He says that leaves are old and that for flowers

Mid-summer is to spring as one to ten.

He says the early petal-fall is past

When pear and cherry bloom went down in showers

On sunny days a moment overcast;

And comes that other fall we name the fall.

He says the highway dust is over all.

The bird would cease and be as other birds

But that he knows in singing not to sing.

The question that he frames in all but words

Is what to make of a diminished thing.

—“The Oven Bird” by Robert Frost

In this Frost sonnet, the speaker employs the kenning “petal-fall” to describe the autumn. The full text of the poem has been included, not for any particular reason, other than it’s simply a lovely, striking poem.

4. Word Play Examples: Malapropism

A malapropism is a device primarily used in dialogue. It is employed when the correct word in a sentence is replaced with a similar-sounding word or phrase that has an entirely different meaning.

For example, the word “assimilation” sounds a lot like the phrase “a simulation.” Employing a malapropism, I might have a character say “Everything is programmed. We all live in assimilation.”

For the most part, malapropisms are humorous examples of a play on words. They often make fun of people who use pretentious language to sound intelligent. But, in everyday speech, we probably employ more malapropisms than we think, so this device also emulates real speech.

The name “malapropism” comes from the play The Rivals by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. In it, the character Mrs. Malaprop often uses words with opposite meanings but similar sounds to the word she intends. Here’s an example from the play:

“He is the very pineapple of politeness!” (Instead of pinnacle.)

Malapropisms are also known as Dogberryisms (from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing), or as acyrologia. Though this word play device is employed humorously, it also demonstrates the complex relationship our brain has with language, and how easy it is to mix words up phonetically.

5. Word Play Examples: Metalepsis

Metalepsis is the use of a figure of speech in a new or surprising context, creating multiple layers of meaning. In other words, the writer takes a figure of speech and employs it metaphorically, using that figure of speech to reference something that is otherwise unspoken.

This is a tricky literary device to define, so let’s look at an example right away:

As he swung toward them holding up the handHalf in appeal, but half as if to keep

The life from spilling…

—“Out, Out” by Robert Frost

The expected phrase here would be “the blood from spilling.” But, in this excerpt, “life” replaces the word “blood.” The word life, then, becomes a metonymy for “blood,” and as this displacement occurs in the common phrase “spilled blood,” “life” becomes a metalepsis.

So, there are two layers of meaning going on here. One is the meaning derived from the phrase “spilled blood,” and the other comes from the use of “life” to represent “blood.” In any metalepsis, there are multiple layers of meaning occurring, as a metaphor or metonymy is employed to modify a figurative phrase, adding complexity to the phrase itself.

This is a tricky, advanced example of word play, and it primarily occurs in poetry. Here are a few other examples in literature:

“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium?”

—Dr. Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Here, the face in question is that of Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman in the world (according to The Iliad and the Odyssey). Helen is claimed by Paris, a prince of Troy, and when he takes Helen home with him, it incites the Trojan war—thus the references to a thousand ships and the towers of Ilium. So, the face refers to Helen, and Faustus describes the beauty of that face tangentially, referencing the magnitude of the Trojan War.

“And I also have given you cleanness of teeth in all your cities.”

—The Book of Amos (4:6)

In this Biblical passage, the phrase “cleanness of teeth” is actually referencing hunger. By having nothing to eat, the people have nothing to stain their teeth with. Thus, the figurative image of clean teeth becomes a metalepsis for starvation.

“To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

—Macbeth (V; v), by Shakespeare

This is a complex extended metaphor and metalepsis. Instead of saying “to the ends of time,” Shakespeare modifies this phrase to “the last syllable of recorded time.” He then extends this idea by saying that life is “a walking shadow, a poor player”—in other words, that which speaks the syllables of recorded time, and then never speaks again. By describing life as an idiot which signifies nothing, Macbeth is saying that life has no inherent value or meaning, and that all men are fools who exist at the whim of a random universe.

Note: this soliloquy arrives after the death of Macbeth’s wife, and it clues us towards Macbeth’s growing madness. So, yes, it’s a very dark passage, but dark for a reason.

To summarize: a metalepsis is a type of word play in which the writer describes something using a tangentially related image or figure of speech. It is, put most succinctly, a metonymy of a metonymy. There is also a narratological device called metalepsis, but it has nothing to do with this particular literary device.

6. Word Play Examples: Oxymoron

An oxymoron is a self-contradictory phrase. It is usually just two words long, with each word’s definition contrasting the other one’s, despite the apparent meaning of the words themselves. It is a play on words because opposing meanings are juxtaposed to form a new, seemingly-impossible idea.

A common example of this is the phrase “virtual reality.” Well, if it’s virtual, then it isn’t reality, just a simulation of a new reality. Nonetheless, we employ those words together all the time, and in fact, the juxtaposition of these incompatible terms creates a new, interesting meaning.

Oxymorons occur all the time in everyday speech. “Same difference,” “Only option,” “live recording,” and even the genre “magical realism.” In any of these examples, a new meaning forms from the placement of these incongruous words.

Here are a few examples from literature:

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.”

—Romeo and Juliet (II; ii), by Shakespeare

“No light; but rather darkness visible”

—Paradise Lost by John Milton

“Their traitorous trueness, and their loyal deceit.”

—“The Hound of Heaven” by Francis Thompson

Note: an oxymoron is not self-negating, but self-contradictory. The use of opposing words should mean that each word cancels the other out, but in a good oxymoron, a new meaning is produced amidst the contradictions. So, you can’t just put two opposing words together: writing “the healthy sick man,” for example, doesn’t mean anything, unless maybe it’s placed into a very specific context. An oxymoron should produce new meaning on its own.

7. Word Play Examples: Palindrome

The palindrome is a word play device not often employed in literature, but it is language at its most entertaining, and can provide interesting challenges to the daring poet or storyteller.

A palindrome is a word or phrase that is spelled the exact same forwards and backwards (excluding spaces). The word “racecar,” for example, is spelled the same in both directions. So is the phrase “Able was I ere I saw Elba.” So is the sentence “A man, a plan, a canal, Panama.”

The longer a palindrome gets, the less likely it is to make sense. Take, for example, the poem “Dammit I’m Mad” by Demetri Martin. It’s a perfect palindrome, but, although there are some striking examples of language (for example, “A hymn I plug, deified as a sign in ruby ash”), much of the word choice is nonsensical.

Because of this, there are also palindromes that occur at the line-level. Meaning, the words cannot be read forwards and backwards, but the lines of a poem are the same forwards and backwards. The poem “Doppelganger” by James A. Lindon is an example.

Want to challenge yourself? Write a palindrome that tells a cohesive story. You’ll be playing with both the spellings of words and with the meanings that arise from unconventional word choice. Good luck!

8. Word Play Examples: Paraprosdokian

A paraprosdokian is a play on words where the writer diverts from the expected ending of a sentence. In other words, the writer starts a sentence with a predictable ending, but then supplies a new, unexpected ending that complicates the original meanings of the words and surprises the reader.

Here’s an example sentence: “Is there anything that mankind can’t accomplish? We’ve been to the moon, eradicated polio, and made grapes that taste like cotton candy.” This last clause is a paraprosdokian: the reader expects the list to contain great, life-altering achievements, but ending the list with something a bit more trivial, like cotton candy grapes, is a humorous and unexpected twist.

With the paraprosdokian, writers contort the expected endings of sentences to create surprising juxtapositions, playing with both words and sentence structures. Here are a few literary examples, with the paraprosdokian in bold:

By the time you swear you’re his,

Shivering and sighing,

And he vows his passion is

Infinite, undying—

Lady, make a note of this:

One of you is lying.

—“Unfortunate Coincidence” by Dorothy Parker

“By the wide lake’s margin I mark’d her lie –The wide, weird lake where the alders sigh –

A young fair thing, with a shy, soft eye;

And I deem’d that her thoughts had flown …

All motionless, all alone.

Then I heard a noise, as of men and boys,

And a boisterous troop drew nigh.

Whither now will retreat those fairy feet?

Where hide till the storm pass by?

On the lake where the alders sigh …

For she was a water-rat.”

—“Shelter” by Charles Stuart Calverley

9. Word Play Examples: Portmanteau

A portmanteau is a word which combines two distinct words in both sound and meaning. “Smog,” for example, is a portmanteau of both “smoke” and “fog,” because both the sounds of the words are combined as well as the definition of each word.

The portmanteau has become a popular marketing tactic in recent years. A portmanteau is also, often, an example of a neologism—a coined word for which new language is necessary to describe new things.

Here are a few portmanteaus that have recently entered the English lexicon:

- Fanzine (fan + magazine)

- Telethon (telephone + marathon)

- Camcorder (camera + recorder)

- Blog (web + log)

- Vlog (video + blog)

- Staycation (stay + vacation)

- Bromance (brother + romance)

- Webinar (web + seminar)

- Hangry (hungry + angry)

- Cosplay (costume + play)

Lewis Carroll popularized the portmanteau, but a work of fiction that’s rife with this word play is Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce. The novel—which is notoriously difficult to read due to its use of foreign words, as well as its disregard for conventional spelling and syntax—has coined portmanteaus like “ethiquetical” (ethical + etiquette), “laysense” (layman + sense), and “fadograph” (fading + photograph).

10. Word Play Examples: Spoonerism

A spoonerism occurs when the initial sounds of two neighboring words are swapped. For instance, the phrase “blushing crow” is a spoonerism of “crushing blow.”

Often, spoonerisms are slips of the tongue. We might confuse our syllables when we speak, which is a natural result of our brains’ relationships to language.

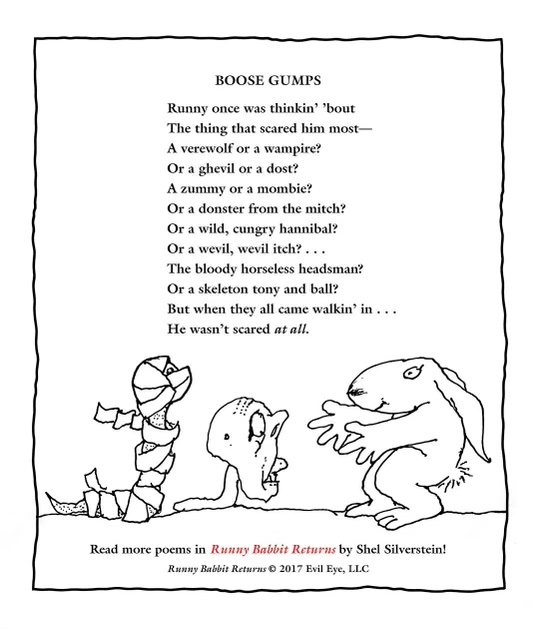

Spoonerisms can be literary examples of a play on words. But they’re also just ways to have fun with language. An example is Shel Silverstein’s posthumous collection of children’s poems Runny Babbit: A Billy Sook.

How to Use a Play on Words in Your Writing

Writers can utilize word play for two different strategies: literary effect, and creative thinking.

When it comes to literary effect, a play on words can surprise, delight, provoke, and entertain the reader. Devices like oxymoron, metalepsis, and kenning offer new, innovative possibilities in language, and a strong example of these devices can move the reader in a way that ordinary language cannot.

Word play can also stimulate your own creativity. If you experiment with language using literary devices, you might stumble upon the following:

- A title for your work.

- Character names.

- Witty dialogue.

- Interesting or provocative description.

- The core idea of a poem or short story.

I’ll give a personal example. Once, in a fiction course, I was struggling to come up with an idea for a short story. A friend and I ended up bouncing words around and came up with the phrase “psychic psychiatrist” (an example of alliteration and polyptoton). Just playing with words like this was enough to inspire me to write a story about exactly that, a psychiatrist who predicts the future for their clients without realizing it.

Titles like The Importance of Being Earnest (a self-referential pun), “Dammit I’m Mad” (palindrome), or Back to the Future (oxymoron) all use word play to frame and guide the story or poem. You might find inspiration for your own work by considering, with careful attention and an appreciation for language, the many possibilities of a play on words.

Experiment with Word Play at Writers.com

The instructors at Writers.com are masters of word play. Not only do we love words, we love to mess with them in surprising and innovative ways. If you want to formulate new ideas for your work, take a look at our upcoming online writing classes, where you’ll receive expert instruction on all the work you write and submit.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Word play or wordplay[1] (also: play-on-words) is a literary technique and a form of wit in which words used become the main subject of the work, primarily for the purpose of intended effect or amusement. Examples of word play include puns, phonetic mix-ups such as spoonerisms, obscure words and meanings, clever rhetorical excursions, oddly formed sentences, double entendres, and telling character names (such as in the play The Importance of Being Earnest, Ernest being a given name that sounds exactly like the adjective earnest).

Word play is quite common in oral cultures as a method of reinforcing meaning. Examples of text-based (orthographic) word play are found in languages with or without alphabet-based scripts, such as homophonic puns in Mandarin Chinese.

Techniques[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

Some techniques often used in word play include interpreting idioms literally and creating contradictions and redundancies, as in Tom Swifties:

- «Hurry up and get to the back of the ship,» Tom said sternly.

Linguistic fossils and set phrases are often manipulated for word play, as in Wellerisms:

- «We’ll have to rehearse that,» said the undertaker as the coffin fell out of the car.

Another use of fossils is in using antonyms of unpaired words – «I was well-coiffed and sheveled,» (back-formation from «disheveled»).

Examples[edit]

This business’s sign is written in both English and Hebrew. The large character is used to make the ’N’ in Emanuel and the ‘מ’ in עמנואל. This is an example of orthographic word play.

Most writers engage in word play to some extent, but certain writers are particularly committed to, or adept at, word play as a major feature of their work . Shakespeare’s «quibbles» have made him a noted punster. Similarly, P.G. Wodehouse was hailed by The Times as a «comic genius recognized in his lifetime as a classic and an old master of farce» for his own acclaimed wordplay.[citation needed] James Joyce, author of Ulysses, is another noted word-player. For example, in his Finnegans Wake Joyce’s phrase «they were yung and easily freudened» clearly implies the more conventional «they were young and easily frightened»; however, the former also makes an apt pun on the names of two famous psychoanalysts, Jung and Freud.

An epitaph, probably unassigned to any grave, demonstrates use in rhyme.

- Here lie the bones of one ‘Bun’

- He was killed with a gun.

- His name was not ‘Bun’ but ‘Wood’

- But ‘Wood’ would not rhyme with gun

- But ‘Bun’ would.

Crossword puzzles often employ wordplay to challenge solvers. Cryptic crosswords especially are based on elaborate systems of wordplay.

An example of modern word play can be found on line 103 of Childish Gambino’s «III. Life: The Biggest Troll».

H2O plus my D, that’s my hood, I’m living in it

Rapper Milo uses a play on words in his verse on «True Nen»[2]

- Keep any heat by the fine China dinner set

- Your man’s caught the chill and it ain’t even winter yet

A farmer says, «I got soaked for nothing, stood out there in the rain bang in the middle of my land, a complete waste of time. I’ll like to kill the swine who said you can win the Nobel Prize for being out standing in your field!».

Eminem is known for the extensive wordplay in the lyrics of his music.

The Mario Party series is known for its mini-game titles that usually are puns and various plays on words; for example: «Shock, Drop, and Roll», «Gimme a Brake», and «Right Oar Left». These mini-game titles are also different depending on regional differences and take into account that specific region’s culture.

[edit]

Word play can enter common usage as neologisms.

Word play is closely related to word games; that is, games in which the point is manipulating words. See also language game for a linguist’s variation.

Word play can cause problems for translators: e.g. in the book Winnie-the-Pooh a character mistakes the word «issue» for the noise of a sneeze, a resemblance which disappears when the word «issue» is translated into another language.

See also[edit]

- Etymology

- False etymology

- Figure of speech

- List of forms of word play

- List of taxa named by anagrams

- Metaphor

- Phono-semantic matching

- Simile

- Pun

References[edit]

- ^ «wordplay: definition of wordplay in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)». Askoxford.com. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.[dead link]

- ^ Scallops hotel – True Nen, retrieved 3 December 2021

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Word play.

- A categorized taxonomy of word play composed of record-holding words

Definition of Word Play

Word play is a literary device, used as a form of wit. In this device, words are used in such a way that they become the main subject of conversation for entertainment and amusement. There are different types of wordplays. It is also called play upon words or play-on-words. Different dictionaries define word play as the exploitation of wit through changing places, contexts, and uses of a word in a way that creates laughter. Word play is also used as a compound word as well as a hyphen such as word-play is hyphenated and wordplay is a compound word. In both cases, it is correct. For example, Merriam-Webster defines this word as “the witty exploitation of meanings and ambiguities of words, especially in puns.” It also states that the word is used as a noun in the sense of cutting jokes.

Types of Word Play

Some of the best word plays include;

- Pun

- Alliteration

- Ambigrams

- Palindrome

- Spoonerism

- Oxymoron

- Anagrams

- Pangrams

- Tongue twisters

Examples of Word Play in Literature

Example #1

Summer Moonshine by P. G. Wodehouse

“A certain critic — for such men, I regret to say, do exist — made the nasty remark about my last novel that it contained ‘all the old Wodehouse characters under different names.’ He has probably by now been eaten by bears, like the children who made mock of the prophet Elisha: but if he still survives he will not be able to make a similar charge against Summer Lightning. With my superior intelligence, I have out-generalled the man this time by putting in all the old Wodehouse characters under the same names. Pretty silly it will make him feel, I rather fancy.”

Although Wodehouse has not used puns, his use of Wodehouse characters, the same names, and specifically, out-generalled show his wit. All these words have been placed at the most suitable places and in the most suitable contexts to cause laughter among his readers. They show how Wodehouse plays with words to amuse his readers.

Example #2

Julius Caesar from William Shakespeare

It would become me better than to close

In terms of friendship with thine enemies.

Pardon me, Julius! Here wast thou bayed, brave hart;

Here didst thou fall; and here thy hunters stand,

Signed in thy spoil, and crimsoned in thy Lethe.

O world, thou wast the forest to this hart,

And this indeed, O world, the heart of thee!

How like a deer, strucken by many princes,

Dost thou here lie!

Master of word play, Shakespeare has beautifully used the words hart, forest, and deer to show that Antony is playing upon words. He has two objects; first to save himself from the enemies of Caesar so that he could exact revenge later, and second to show the people how the rebels have killed Caesar. Readers can easily spot the use of heart and heart in the last three lines full of irony and sarcasm only because of this wordplay.

Example #3

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Give me leave. Here lies the water; good: here

stands the man; good; if the man go to this water,

and drown himself, it is, will he, nill he, he

goes,–mark you that; but if the water come to him

and drown him, he drowns not himself: argal, he

that is not guilty of his own death shortens not his own life.

Although Hamlet is full of puns, these lines uttered by the First Clown show that Shakespeare is at his best when it comes to word play. If you read carefully, you find that the clown has used will, nill, good, water, drown, life, and death in a way that they all seem to contain some metaphysical quibblings and questions that are very hard to answer. In a way, they are also amusing that such a person could use words in such a way that they create serious concern as well as laughter.

Example #4

Rhyme PUNishment from Adventures Word Play by Brian P. Clearly

“Jamaica Sandwich?” Grandma asked,

and I replied, “I ate

some Chile from a China bowl

and Turkey from a plate.

Although these four verses by Brian Clearly show the use of different words in a different way, they also show a very interesting truth about different countries how they are named after things and things are named after them. He has used Jamaica, Chile, China, and Turkey for sandwiches, chili, and turkey for foods commonly known and used in the United States as well as across the globe. This is a beautiful wordplay. In fact, this entire book of Brian Clearly comprises different word plays.

Functions of Word Play

Based on different types, a word-play plays different functions. The first function is to create a sort of joke or fun for the readers so that they should enjoy reading such as Wodehouse has shown, using a portmanteau, out-generalled. The second purpose is to create ambiguity to make people feel that the person is different from what he is speaking. Shakespeare has done the same thing in his play, Julius Caesar. The third is to present some universal truths or metaphysical dilemmas to the public to think deeply such as stated by the clown of Hamlet. The fourth is to make children and people have deeper meanings than are universally accepted in some other way. Brian Clearly has done this in his poetry.

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Wordplay

- Quiz

I. What is Wordplay?

Wordplay (or word play, and also called play-on-words) is the clever and witty use of words and meaning. It involves using literary devices and techniques like consonance, assonance, spelling, alliteration, onomatopoeia, rhyme, acronym, pun, and slang (to name a few) to form amusing and often humorous written and oral expressions. Using wordplay techniques relies on several different aspects of rhetoric, like spelling, phonetics (sound and pronunciation of words), and semantics (meaning of words).

Here are some simple jokes that use wordplay for their humor:

Q: What did the ram say to his wife?

A: I love ewe.

Puns are some of the most frequently used forms of wordplay. Here, when spoken aloud, “I love ewe” sounds like “I love you.” But, the word “ewe” is the term for a female sheep.

Q: What did the mayonnaise say when the girl opened the refrigerator?

A: Close the door, I’m dressing!

This joke relies on two meanings of the word “dressing” for its humor—one for “dressing” as in putting on clothes, and one for mayonnaise being a type of salad “dressing.”

III. Wordplay Techniques

Here we will outline some primary wordplay techniques. However, this represents only a small selection; in truth, the actual list includes hundreds of techniques!

a. Acronym

Acronyms are abbreviations of terms formed by using parts or letters of the original words, like saying “froyo” instead of frozen yogurt or “USA” for United States of America. The use of acronyms is increasingly common in our culture today—both formal and informal—and has risen in popularity over the past decade as texting has become commonplace (think of BRB and TTYL!). We use acronyms for all kinds of things, though—for example, the recent news about Great Britain’s exit from the European Union has come to be referred to as “Brexit,” combining parts of the words “Britain” and “Exit.”

b. Alliteration

Alliteration is a technique expressed by repeating the same first consonant sound in a series of words. You’re probably pretty familiar with this device, as it is a distinguishing feature of many nursery rhymes and tongue twisters. For example, “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers.”

c. Assonance and Consonance

Assonance is the matching of vowel sounds in language, while consonance is the matching of consonant sounds. These techniques can create some very catchy and interesting wordplay.

Assonance creates a rhyming effect, for example, “the fool called a duel with a mule.” Consonance has a pleasing sound, for example, “the shells she shucks are delicious.”

d. Double Entendre

Double entendre is the double interpretation of a word or phrase, with the secondary meaning usually being funny or risqué. Naturally, double entendres rely on wordplay for their success, because the words used have a literal and a figurative meaning. For example, if you said “The baker has great buns,” it could be understood in two ways!

e. Idiom

Idioms are popular, culturally understood phrases that generally have a figurative meaning. The English language alone is said to have more than 25,000 idioms. Common examples are almost endless, but to name a few, “it’s raining cats and dogs,” “butterflies in my stomach,” “catch a cold,” “rise and shine,” and “chill out” are some idioms that you probably hear every day.

f. Malapropism

Malapropism is incorrect use of a word or phrase when you mean to use another word or phrase that sounds similar. For example, on Modern Family, Gloria says “Don’t give me an old tomato” instead of “Don’t give me an ultimatum”

g. Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia are words that phonetically imitate sounds. Some common examples are boom, achoo, pow, whoosh, bam, tick-tock, click, meow, woof, tweet, and ribbit, just to name a few.

h. Pun

A pun is the ultimate form of wordplay and probably the most popular and widely used. In fact, many would define it as wordplay in general! Puns uses multiple meanings and the similar sounds of words to create a humorous affect. For example, “love at first bite” is a food pun for the idiom “love at first sight,” or, “spilling that glue made a real sticky situation!” uses glue’s main property (stickiness) to make a joke out of the common phrase “sticky situation,” which means a difficult situation.

i. Spelling

Using spelling for wordplay is a tricky but fun technique that obviously works best when you can see it in written form. One great example is the web-sensation pig “Chris P. Bacon,” whose name sounds like “Crispy Bacon”!

j. Rhyming

As you probably know rhyming is the matching and repetition of sounds. It’s an especially popular form of wordplay for poetry, nursery rhymes, and children’s literature because of its catchy and rhythmic style. There are all different rhyme schemes that writers use, from rhyming every word to just rhyming the first or last word of a line. For example, Roses are red/Violets are blue/ Sugar is sweet/ And so are you! follows the scheme ABCB.

k. Slang

Slang is the use of casual and unique language and expressions, and varies depending on age, location, field of work or study, and many other factors. Localized slang and pop culture lingo often rely on wordplay for meaning, and are often filled with idioms (see above).

IV. Importance of Wordplay

Wordplay’s use extends far beyond jokes and humor. It makes language more unique, more interesting, and more witty and amusing than using standard words and phrases. It has had an important role in rhetoric going as far back as the classics of literature and philosophy, from Plato to Shakespeare to Mark Twain. What’s more, it is a huge part of all languages and cultures around the globe, used not only by talented writers, speakers, and storytellers, but by all people of all ages. As soon as kids start telling jokes, they starting using wordplay!

V. Examples of Wordplay in Literature

Example 1

Everybody knows Dr. Seuss for his completely unique wordplay and rhymes. Often a bit nutty, his stories are one-of-a-kind with creative and often totally strange language. While most authors would choose words to fit their rhyme schemes, Dr. Seuss often just makes up new words altogether. Here’s an example from a book you probably know very well, One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish:

At our house we open cans.

We have to open many cans.

And that is why we have a Zans.

A Zans for cans is very good.

Have you a Zans for cans?

You should.

Here, Dr. Seuss needed a creature that rhymes with the word “cans,” so he decided to create one called a “Zans.” You can see the author’s wordplay clearly here—he uses not only made-up words, but rhyming as well; the signature Dr. Seuss style!

Example 2

Shakespeare was a master of language and wordplay, and his puns are particularly well known. Here’s an example from Romeo and Juliet:

Mercutio: “Nay, gentle Romeo, we must have you dance.”

Romeo: “Not I, believe me. You have dancing shoes

With nimble soles; I have a soul of lead

So stakes me to the ground I cannot move.”

Here, Romeo uses wordplay to speak about both dancing and his broken heart. First, he refers to Mercurio’s shoes’ “nimble soles,” but says he himself has a “soul of lead”—this means he both has a heavy heart, but also shoe soles of lead would “stake” him to the ground so that he “cannot move,” making it impossible to dance.

Example 3

In Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, the Weasley twins Fred and George open their own magic joke shop. Some of the advertisements for their products use some pretty funny wordplay, like this:

Why Are You Worrying About You-Know-Who?

You SHOULD Be Worrying About

U-NO-POO —

the Constipation Sensation That’s Gripping the Nation!

In the series, the evil Lord Voldemort is sometimes called You-Know-Who because it’s considered bad luck to speak his real name. Here, Fred and George make a risky joke about Voldemort by referring to him in their ad for a trick candy that causes constipation. They use rhyming lines with assonance, and the pun “You-No-Poo” to make their advertisement comedic and appealing to fellow jokesters.

VI. Examples in Popular Culture

Example 1

The comic book style TV series iZOMBIE is filled with comedic wordplay about brains and zombie life. In fact, even the protagonist’s name, “Liv Moore,” is a play-on-words (she “lives more” even though she is a zombie). Some of the most notable instances of wordplay come in the chapter titles, which each feature a pun based on a combo of popular culture references and brains. Here are some examples from the episode “Even Cowgirls Get the Black and Blues,” which is a pun, too!

Pawn of the Dead

This chapter titles makes a pun out of the well-known horror flick “Dawn of the Dead” as Liv and her partner enter a pawn shop.

Weapons of Glass Destruction

This chapter title makes a pun out of “Weapons of Mass Destruction.”

Seattle PDA

This chapter title, picturing Liv’s cop partner and member of the Seattle Police Department (Seattle PD) makes the pun “Seattle PDA.”

Example 2

In Winnie the Pooh, Pooh often confuses the sounds of words with their real meaning. In this clip, Owl is using the word “issue,” and Pooh soon thinks he has a cold…

Winnie the Pooh: Owl’s Cold Clip

Here, Pooh mistakes Owl’s use of the word “issue” as the sound “achoo,” which as you know is associated with sneezing. As Owl tries to explain, Pooh continues to tell him that he might need to go lay down. This cute and clever wordplay is a signature feature of Pooh’s thinking.

Example 3

The comedy series Modern Family is renowned for its use of all kinds of clever and hilarious wordplay. In particular, the character Gloria is known for her mispronunciations and malapropisms when speaking English, which is her second language. In this clip, her husband Jay points out some of the silly mistakes that she makes when speaking:

Baby Jesus Sneak Peek — Modern Family

Here, we learn some of Gloria’s errors: “Doggy dog world” instead of “Dog-eat-dog world,” “blessings in the skies” instead of “blessings in disguise,” and so on. The clip ends with her final mistake—she accidentally ordered Jay a box of baby Jesus’ instead of a box of baby cheeses!

VII. Related Terms

Figure of Speech

A figure of speech is a word or phrase that has a figurative (not literal) meaning. Many types of wordplay will use figures of speech, and vice versa. Some types of figures of speech include metaphors, similes, irony, oxymorons, and so on.

VIII. Conclusion

In all, wordplay is a wonderful rhetorical device that can serve all kinds of purposes across all kinds of genres and styles. It can be used by writers and everyday people alike to create interesting and memorable language that often quickly gains popularity and becomes widely understood. Wordplay never goes out of style and never stops changing and growing, and therefore, it’s an essential and important part of the English language for writers and speakers of all ages.

Abstract:

Wordplay occupies a significant position in several important conceptions and theories of literature, principally because it has both a performative and a critical function in relation to language and cognition. This article describes the various uses and understandings of wordplay and their origins in its (Whose?) unique flexibility, which involves an interaction between a semiotic deficit and a semantic surplus. Furthermore, the article illustrates different methods of incorporating theories of wordplay into literature and literary theory, and finally, it demonstrates the ways in which the use of wordplay often leads to the use of metaphors and figurative language.

Introduction

Puns and wordplay occupy a significant position in literature as well as in various ways of reflecting on and conceptualizing literature. They can be used to produce and perform a poetic function with language and they can be used critically, which entails considering them from a distance(?) as utterances that undermine meaning and sense and that ultimately accomplish a deconstructive performance. A dictionary definition of the word pun illustrates that both homonymy (when two words with unrelated meanings have the same form) and polysemy (when one word form has two or more, related, meanings) can properly be used to form puns: “a play on words, sometimes on different senses of the same word and sometimes on the similar sense or sound of different words” (American Heritage College Dictionary 1997, Third Edition). However, this definition could also be extended to embrace the term wordplay, mainly because pun seems to cover only single words. [1] So a more precise definition of pun might be “a play on words, sometimes on different senses of the same expression and sometimes on the similar senses or sounds of different words” (This is between inverted commas. Where is the citation?).

The various uses and understandings of wordplay originate from a flexibility which this article attempts to identify and describe from both a historical and a contemporary perspective. Wordplay involves an interaction between a semiotic deficit and a semantic surplus and is therefore primarily understood and used in two different ways in literature and literary theory. Literary scholar Geoffrey Hartman succinctly articulated this interaction in an essay titled “The Voice of the Shuttle: Language from the Point of View of Literature” (1970) I don’t know which system of citation the author is using. If it is APA, this citation is wrong: “You can define a pun as two meanings competing for the same phonemic space or as one sound bringing forth semantic twins, but, however you look at it, it’s a crowded situation” (1970: 347). The semiotic deficit is caused by one sign or expression signifying at least two meanings. The semantic surplus, on the other hand, refers to the cognitive event happening in the individual (in literature, the reader) experiencing the play on words. The article describes these two features of wordplay with the help of a few examples of wordplay in literature and literary theory, and it also demonstrates that the use of puns and wordplay often leads to the use of metaphor and figurative language – or a semantic surplus like Hartman’s “twins”. Furthermore, the article presents an argument for distinguishing between exploring the intention behind the use of wordplay and exploring wordplay itself. In the previous paragraph, the author talked about “an essay” by Hartman. Is he/she still referring to that essay when he/she talks about “the article”?

Paranomasia and traductio

“In the beginning was the pun” (1957: 65), writes Samuel Beckett in his novel Murphy from 1938 The citation is wrong, according to APA standards, but although puns and wordplay as such may have been with us from the very beginning (of what?) Beckett is paraphrasing the Bible), actual descriptions of wordplay do not appear until the rhetorical studies of Cicero and Quintilian. Parts of Plato’s Cratylus do; however, bear a superficial resemblance to wordplay because Socrates makes fun of etymological argumentation, showing the reader how language can lead to sophistic blind alleys and dead ends, which can be deceptive to those who are not familiar with the well-known schism between the world of ideas and the world of phenomena. Moreover, in Phaedrus, Socrates argues that “in the written word there is necessarily much which is not serious” (277E) It wasn’t written by Socrates, but by Plato. It is this argumentation which Jacques Derrida later criticizes in “Plato’s Pharmacy” (1998) the system of citation does not seem to be consistent. Names of books are alternatively written in bold type, without inverted commas, or in normal type, with inverted commas, in which Derrida attempts to demonstrate the erosion of Plato’s argumentation through the two-sidedness and ambiguity of the word pharmakon and through the way Plato plays on the multiple meanings of this word. Writing is both a remedy and a poison, producing both science and magic. Plato’s antidote to sophism is episteme, or, in Derrida’s view, mental or epistemological repression. Derrida’s text demonstrates an interesting and intimate connection between writing, wordplay, oblivion and memory, but since this is a perspective a bit outside the framework of this article I will carry on a more historical view.. [2]

Over time, wordplay has been linked to the rhetorical terms of traductio and adnominatio. The anonymous Rhetoric to Herennius (Rhetorica ad Herennium), written in the period 86-82 BC and ascribed to Cicero until the fifteenth century, states that “[t]ransplacement [traductio] makes it possible for the same word to be frequently reintroduced, not only without offence to good taste, but even so as to render the style more elegant” (1954: 279) The work of Derrida was not cited like this. Traductio is classified below figures of diction and is compared to other figures of repetition. Common to these figures is “an elegance which the ear can distinguish more easily than words can explain.” (1954: 281). Identifying wordplay as traductio, however, may not entirely correspond with the understanding we have of wordplay today, although the lack of explanatory words within this rhetorical figure is comparable to the above-mentioned thesis. Today, we would perhaps rather characterize wordplay as adnominatio [called paranomasia in the English translation]. The Rhetoric to Herennius states that wordplays should be used in moderation because they reveal the speaker’s labour and compromise his ethos:

Such endeavours, indeed, seem more suitable for a speech of entertainment that for use in an actual cause. Hence the speaker’s credibility, impressiveness, and seriousness are lessened by crowding these figures together. Furthermore, apart from destroying the speaker’s authority, such a style gives offence because these figures have grace and elegance, but not impressiveness and beauty. (1954: 309) I have indented this, according to APA norms.

Wordplay must therefore be used economically so as not to seem childish or to monopolize the listener’s attention. In addition, the author of the Rhetoric points to the fact that one very quickly becomes too clever by half?? if the frequency of paronomasia is too high.

In Quintilian’s treatise on rhetoric, The Orator’s Education (Institutio Oratoria), wordplay is reckoned among figures of speech (9.13). Another style of citation. Quintilian divides these into two types, the first of which concerns innovations in language, while the second concerns the arrangement of the words. The first type is, according to Quintilian, more grammatically based, while the latter is more rhetorically based, but with indistinct limits. At the same time, the first one protects the speaker against stereotypical language.

Wordplay belongs to what Quintilian refers to as figures which depend on their sound; other figures depend on alteration, addition, subtraction or succession. Quintilian treats wordplay immediately following the chapter on addition and subtraction, thereby suggesting its status as something which neither subtracts nor adds. Otherwise his conception of wordplay is similar to that of the Rhetorica ad Herennium: wordplay should be used with cautiousness and only if it to some extent strengthens a point, in which case it can have a convincing effect. [3]

What we can learn by reading these passages on wordplay in Quintillian and the Rhetorica ad Herennium is that ever since the beginning of literary studies our understanding of wordplay has oscillated between at least two different extremes: traductio and adnominatio / paranomasia, or, one could say, between an outer understanding concerned with the context and an inner understanding mostly concerned with language itself. This could also be one of the main reasons why literary theory has tended to describe puns and wordplay in two ways: either as magical (iconic) language use or as critical language use. Magical language use has much in common with wordplay as a rhetorical figure, and thus also with the way wordplay was used in antiquity and in the romantic era, between which periods the literature of Shakespeare creates an important link. For instance, it is quite remarkable that at first Shakespeare was admonished for his plays on words. In Germany, the Enlightenment poet and translator of Shakespeare, C.M. Wieland citation?, also complains about the wisecracks. He calls them albern (silly) and ekelhaft (disgusting). When A.W. Schlegel citation?, on the other hand, gets hold of Shakespeare’s texts, he is much more attentive to and respectful of the latter’s excesses in language. Schlegel is in debt to Herder citation?, who is one of the first in Germany to appreciate the poetry in Shakespeare’s works (their rhythm, melody and other more formal qualities) (cf. Larson (1989)). We can’t carry out this comparison, because the works have not been properly cited.

By using the rather odd term magical language, this article aims to carry on colloquial a German tradition of treating wordplay as Sprachmagie. Walter Benjamin, for instance, construes language as magical or self-endorsing citation?. [4] Critical language use, however, is more comparable to the use of wordplay and the discussion of wit in the Age of Enlightenment, and thus more generally to humour, including, for instance, the joke and the anecdote (whereas in relation to magical language use, wordplay should be regarded as akin to the riddle, the rebus and the mystery). Much literary theory may therefore have adopted these two ways of dealing with and understanding wordplay: it is treated as exceptionally poetic and almost magical precisely because it is untranslatable, or as something which can be used in a general critique of language in which this “untranslatableness” is used as an argument for the arbitrariness of the relationship between signifié and signifiant .citation?The words were not coined by the author of this paper.

Wordplay as part of language criticism

The work of the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure citation may be seen as a prism for the two understandings of wordplay throughout the twentieth century. On the one hand, there is the scholar Saussure, who later became famous for his hypothesis of the arbitrary relationship between signifié and signifiant and for his statement that language only contains differences without positive terms. On the other hand, there is the “other” Saussure, who, besides his more official scholarship, occupies himself with anagrams in Latin texts (cf. Starobinski 1979). In his private scholarship Saussure considers the sign highly motivated, which stands in contrast to his thesis of the arbitrariness of the sign in his official scholarship. Saussure’s remarkable occupation with language alternates between an almost desperate confidence in language and a growing distrust of its epistemological value. The discussion in the last part of this article will be based on this distrust, orienting it toward Nietzsche and Freud, since they represent two of the most predominant views on language and thus wordplay in several important literary theories of the twentieth century, not least Russian Formalism and deconstruction.

Franz Fürst (1979) wrongly cited, according to APA norms mentions that wordplay changes character during the nineteenth century. First, the romantic age idealizes it, changing its characteristics. Wordplay is not only connected to wit, but also to – in my free translation from Bernhardi’s Sprachlehre (1801-1803) citation – the eternal consonance of the universe through its heterogeneous homogeneity. [5] The coherence between sound and meaning was therefore at first considered deeper than might be expected, but the coherence, as the future would show, also had another side displaying a quite different function of wordplay. Fürst explains:

Aus einer ähnlichen Bemühung um die Wiederherstellung der engen Wort-Ding-Beziehung, jedoch mit karikaturistischer Absicht, entstand eine neue Technik des Wortspiels, die von Brentano und ihm folgend von Heine und Nietzsche verwendet wurde. Diese Technik verzichtet auf das Urwort und begnügt sich mit der Wortentstellung, der Karikatur eines ehemals organisch-sinnvollen Wortes zur Bezeichnung einer entstellten Wirklichkeit. (1979: 49)

We need a translation of this.

In Fürst’s view, from pointing out a deeper coherence, wordplay now stands at the service of a distorted reality. It becomes an example of the play of falseness and designates a disfigured reality, especially concerning epistemological questions. The connection with this deeper coherence is therefore eliminated from language and discarded. For example, wordplay and other rhetorical figures which build upon likeness, like the metaphor, are denigrated in Nietzsche’s work from 1873, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense” citation , when he proclaims that the truth is only “[a] mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms – in short, a sum of human relations which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically” (1982: 46-47). Martin Stingelin points out that Nietzsche’s wordplay “gewinnt (…) seine reflexive Qualität gerade durch Entstellung” (1988: 348) Translation, citation. Precisely because everything is rhetoric anyway, we must turn the sting of language against itself. In this connection, wordplay is the least convincing example of false resemblances made by language and can therefore participate reflectively and ironically in such an Enstellung (distortion). The failure to convince should indicate, and thereby ironically convince us, that there is something inherently wrong with language and the epistemological cognition it attends to for us.

Besides Nietzsche’s critique, we also find Freud’s general distrust of language in the beginning of the twentieth century. Most relevant to wordplay is his work The Joke and Its Relation to the Unconscious. Date, citation.With this as a starting point, it is possible to make some more general remarks about the fundamental importance of the relationship between wordplay and metaphor in the different ways in which wordplay is understood and used in twentieth-century literary theory.

Freud believes that “play on words is nothing but condensation without substitute-formation; condensation is still the overriding category. A tendency to parsimony predominates in all these techniques. Everything seems to be a matter of economy, as Hamlet says (‘Thrift, thrift, Horatio!)” Speech marks (2003: 32). Freud’s interest in wordplay therefore goes by way of the joke, which is primarily characterized by economization and condensation. [6] A substitution is omitted; in other words, wordplay is not a translation of something unconscious, but a translation which more precisely takes place in language. This is also one of the definitions that Walter Redfern arrives at (1997: 265). Redfern’s study of wordplay is without doubt the most comprehensive yet in a literary context, but the many metaphorical classifications – for instance, ubiquity, equality, fissiparity, double-talk, intoxication (2000: 4) or “bastard, a melting-pot, a hotchpotch, a potlatch, potluck” (2000: 217) – are characteristic of the relationship between wordplay and metaphor. Wordplay therefore has to do with something fundamentally poetic in language, or as Roman Jakobson puts it, poetry is precisely characterized by being untranslatable:

In poetry, verbal equations become a constructive principle of the text. Syntactic and morphological categories, roots, and affixes, phonemes and their components (distinctive features) – in short, any constituents of the verbal code – are confronted, juxtaposed, brought into contiguous relation according to the principle of similarity and contrast and carry their own autonomous signification. Phonemic similarity is sensed as semantic relationship. The pun, or to use a more erudite and perhaps more precise term – paronomasia, reigns over poetic art, and whether its rule is absolute or limited, poetry by definition is untranslatable. (1987: 434)

If wordplay may be characterized as a translation in language, metaphor may be considered a translation with language, and each time this “inner” translation or untranslatability of a pun or wordplay is translated, words for this translation are lacking.

Arguably, this is exactly where metaphor helps, like a Band-Aid for a small wound. For this lack or deficit of words produces a poetic surplus which is precisely able to express itself in metaphors and figurative language in general. The latter is an attempt to explain the translation or translate it to something more comprehensible. Whereas the metaphor gives the sense of an effective blend between two semantic fields which together create a third one, wordplay gives a very different impression. The “third place” which the wordplay creates in its expression is not intellectually comprehensible, but rather inscribed in the form of its own manifestation, a distinctive blend of sound and sense. The incomprehensibleness is an argument for both of its general understandings, partly according to a view which considers language something which can reveal the nonsense of a truth (language criticism) and partly according to a certain kind of nonsensical truth, the idea that language contains more than we are aware of (magical language use). Consequently, it is not so odd that metaphor is useful for describing wordplay: metaphor creates a convergence between several semantic fields by covering up the differences between them and in so doing often makes poetry happen. Wordplay, on the other hand, fixes the difference in the mind, thus maintaining the convergence in its very expression. Take, for instance, the literary example of Shakespeare’s Sonnet CXXXII:

THINE eyes I love, and they, as pitying me,

Knowing thy heart torment me with disdain,

Have put on black and loving mourners be,

Looking with pretty ruth upon my pain.

And truly not the morning sun of heaven

Better becomes the grey cheeks of the east,

Nor that full star that ushers in the even,

Doth half that glory to the sober west,

As those two mourning eyes become thy face:

O! let it then as well beseem thy heart

To mourn for me since mourning doth thee grace,

And suit thy pity like in every part.

Then will I swear beauty herself is black,

And all they foul that thy complexion lack.

The sonnet is replete with wordplay and puns, especially on the words “I” and “eye”, and morning and mourning no inverted commas here?, but also and perhaps less importantly on the words “ruth” and “truth”. Appropriately, the sonnet contains two instances of the word “I”, punningly mirroring the two eyes. But an expression and a metaphor like “the grey cheeks of the east” would simply not emerge without the existence of the pun between morning and mourning. The poem develops and invents a vocabulary and uses expressions which would simply not exist or appear without the puns and plays on words. It actually manages to connect blackness with beauty because of the pun between mourning and morning – which also connects the sun with the “full star” and in this manner with the night. Hence, everything that the “I” in the sonnet lays eyes on is “polluted” by a look of mourning and pity.

The connection mentioned above causes most scholars to describe wordplay as a potential metaphor; even Freud (especially read in the perspective of Jacques Lacan citation [7] ) indicates that we should understand wordplay this way. However, no one has shown that metaphor is a potential wordplay. The question must be whether the connection goes both ways or if wordplay simply is a “more initial” metaphor? In any case, following Lakoff and Johnson’s now classic theory (1980), it is easy to suspect that so-called dead metaphors can be played on more easily than other words – for example, the word “leg”, which is used in connection with chairs, tables and human beings, or words like “root” or “rose”, which function in countless contexts. The ambiguity is most severe in connection with some of the key examples provided by Lakoff and Johnson, such as our value-laden and metaphorical organization of space in up and down, in and out, and so forth. The reason for this is probably not that these expressions are metaphorical, but rather that they belong to the trite vocabulary which often activates wordplay – makes it alert, as Redfern citation writes.

In other words, a revitalizing process in language takes place between wordplay and metaphor. Wordplay is not more original than metaphor, nor is the reverse true, for that matter. Experience has shown that wordplay has a tendency to generate metaphors when we attempt describe what they exactly mean and that dead metaphors have a tendency to generate wordplay. Regarding the latter, the same applies to dead language in general, such as hackneyed proverbs, phrases and clichés. Along with the dead metaphors, these expressions make up an un-sensed language which often activates wordplay.

The more remarkable of these two relations is without doubt the first one, which I will therefore focus on. The relation between wordplay and metaphor outlined above corresponds with the one that Maureen Quilligan (1992) identifies between wordplay and allegory. Below, we will examine Quilligan’s understanding of their connection.

Wordplay and allegory

Quilligan tries to redefine allegory as a genre in which wordplay plays a central part due to its ambiguousness, or as Quilligan writes, “[a] sensitivity to the polysemy in words is the basic component of the genre of allegory” (1992: 33). Quilligan sees wordplay as initiating the unfolding of the relationship of the text to itself. The text comments on itself, not discursively, but narratively. In this way an author does the same thing with allegory as the literary critic, but the difference is that the author makes commentary on – that is, enacts an allegoresis of – his own text, which is due to the fact that language is self-reflexive. But this self-reflexivity is only brought about through the reader, who therefore constantly plays an important role in Quilligan’s reading and re-evaluation of allegory. Self-reflexivity is, however, potentially inscribed in the text through certain traces, especially through polysemy, which expresses itself on the most fundamental literal level – specifically, in the sounds of the words – and it is in this respect that wordplay enters the picture alongside allegory.

Quilligan uses Quintilian to differentiate between allegory and allegoresis. Allegoresis is literary interpretation or critique of a text, and it was this concept that Quintilian was referring to when he wrote that allegory means one thing at the linguistic level and another at the semantic level; in other words, as a figure, allegory could retain a separation between several semantic levels for a long time – for example, between a literal and a figurative level. However, the “other” which the word allegory points towards with its allos is not someone floating somewhere above the text, but the possibility of an otherness, a polysemy, says Quilligan, on the page and in the text. The allegory designates the fact that language can mean numerous things at once. This very redefinition causes Quilligan to turn towards wordplay. Besides, Quilligan wants to escape from a vertical understanding of allegory such as it has been inherited from Dante, who organized his Divine Comedy according to the Bible, which he believed had four layers of meaning. Quilligan suggests that allegory works horizontally, so that the meaning is increased serially by connecting the verbal surface before moving to another level – for example, beyond or above the literal level. And this other level which she refers to has to be located in the reader, who will gradually become aware of the way he or she creates the meaning of the text. Out of this awareness comes a consciousness, not just of how the text is read, but also of the human response to the narrative. Self-reflexivity occurs, and, finally, out of this a relation is established to the other (allos) towards which the allegory leads its reader through the allegoresis. This sensation of the real meaning can be called sacred. Quilligan aims to grasp allegory in its pure form before it becomes allegoresis. Through her readings, she tries to identify a more undetermined conception of allegory on a linguistic level before it gets determined by and in the reader. Quilligan could have used Quintilian’s definition of allegory as a continued metaphor (III, 2001, 8:6: 44) to establish a relation between allegory, metaphor and wordplay. In my view she thus misses something essential in the contiguous relationship between wordplay, allegory and allegoresis, and this is the making of metaphors. The relation between wordplay and metaphor constitutes a more intimate bond than that between wordplay and allegory, or, as James Brown puts it: “The pun is the first step away from the transparent word, the first step towards the achievement of symbolic metaphor” (1956:18). But this does not mean that wordplay is some sort of metaphor, as Brown seems to suggest. More accurately, it would be reasonable to suggest that wordplay gives rise to creative language usage, including metaphors and figurative language use in general. This very use is an attempt to translate the relative untranslatability of wordplay, and thereby to satisfy a natural human desire for understanding.

Russian formalism vs. deconstruction

By treating the text as described above, Quilligan can read several texts in a new and constructive manner inspired by the way that early literary works such as The Faerie Queene way of writing titles deal with language. But it is principally Quilligan’s starting point and to a lesser degree her treatment of the text that I aim to pinpoint with my focus on wordplay. This article does not claim that the twentieth century should only be understood in the light of wordplay, but rather that in some periods wordplay was used with very specific intentions, and that it offers an understanding of language which several literary theories benefit from.

Wordplay stands out particularly in two twentieth-century literary theories – namely, Russian formalism and literary deconstruction in the wake of Jacques Derrida citation – but it is used in very different ways in these theories. In Russian formalism, wordplay involves a revitalization of language, [8] parallel to the concept of skaz, [9] which refers to an illusion of a kind of orality or even realism in literary language. In contrast, in deconstruction, wordplay is often tied to writing’s influence on language in general – to a grammatology, to borrow Derrida’s term. From a deconstructive perspective, wordplay deals with the inadvertent or unintended in the intended (cf. Gordon C.F. Bearn 1995a: 2), or with absence in presence; the exact opposite is true in Russian formalism, which deals with puns and wordplay as a form of oral presence in writing, likening this to a kind of absence. Here, as in other cases, wordplay is involved in a fundamental shift in perspective between a semiotic deficit and a semantic surplus in what may be called a constructive and deconstructive construction of meaning.

An example of this problematic is a book by Howard Felperin citation problems with the symptomatic title Beyond Deconstruction. The Uses and Abuses of Literary Theory. In this book, Felperin differentiates between what he calls the enactment and counter-enactment of wordplay, emphasizing counter-enactment at the expense of enactment:

If the figures of enactment, of “speaking in effect” in Shakespeare’s phrase, work cumulatively to integrate the jigsaw puzzle of language into concrete replica of the sensory world, the pun is precisely that piece of language which will fit into several positions in the puzzle and thereby confound attempts to reconstruct the puzzle into a map or picture with any unique or privileged reliability or fidelity of reference. Whereas metaphor and onamatopeia attempt to bridge the precipitate fissures between signs and their meaning, paronomasia [or wordplay; Felperin does not make a distinction] effectively destabilizes further whatever conventional stability the relation between sign and meaning may be thought to possess. (1985: 185) (My addition)