Recommended textbook solutions

Biology

1st Edition•ISBN: 9780133669510 (3 more)Kenneth R. Miller, Levine

2,591 solutions

Human Resource Management

15th Edition•ISBN: 9781337520164John David Jackson, Patricia Meglich, Robert Mathis, Sean Valentine

249 solutions

Clinical Reasoning Cases in Nursing

7th Edition•ISBN: 9780323527361Julie S Snyder, Mariann M Harding

2,512 solutions

Human Resource Management

15th Edition•ISBN: 9781337520164John David Jackson, Patricia Meglich, Robert Mathis, Sean Valentine

249 solutions

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a matching sheet?

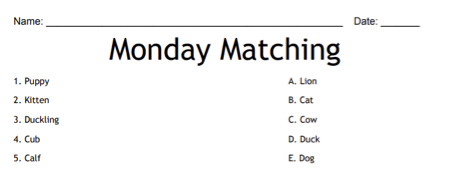

A matching sheet, or a matching quiz, is a sheet with two columns. In the first column there will be a word, statement or question, and in the second column are the answers, jumbled around in a different order.

Students will then match the items in column A with the related answers in column B. Here is an example of a simple matching sheet where students would match up the name of the baby animal in column A with the adult name of the same animal in column B:

Who can play matching sheets?

Matching sheets are so customisable that teachers can create matching quizzes for any different age and education level. Your matching test template can be as simple as single word associations, or as complicated as difficult equations to solve.

With over 8,000 pre-made matching quiz templates available on WordMint, you can select and customise one of the existing templates or start fresh and create your own.

How do I create a matching worksheet template?

Simply log in to your WordMint account and use our template builders to create your own custom matching quiz templates. You can write your own titles, and then create your question and answers.

For easily adding multiple lines of questions and answers at once, you can use the ‘add multiple clues’ option where you can create all of your matching sheet lines at one time.

What is WordMint?

WordMint is your go to website for creating quick and easy templates for word searches, crosswords, matching sheets, bingo and countless other puzzles. With over 500,000 pre-made puzzles, you can select one of our existing templates, or create your own.

Do you have printable matching quiz templates?

Absolutely! All of our templates can be exported into Microsoft Word to easily print, or you can save your work as a PDF to print for the entire class. Your puzzles get saved into your account for easy access and printing in the future, so you don’t need to worry about saving them at work or at home!

Do you have matching sheet templates in other languages?

Yes! We have full support for matching quiz templates in Spanish, French and Japanese with diacritics including over 100,000 images. You can use other languages just for your titles and instructions, or create an entire matching worksheet in another language. Matching sheets can be a fantastic tool for students learning new languages!

Can I convert my matching quiz template into other puzzles?

With WordMint you can create a template and then use it to convert into a variety of other executions — word search, word scramble, crosswords or many more.

Are matching sheets good for kids?

The teachers that use WordMint love that they are able to create matching quiz templates that challenge their students cognitive abilities, and test their comprehension in a new and interesting way.

You can theme your matching sheet, and the ability to use different languages means that you can work language learning into your lessons as well. Because WordMint templates are totally custom, you can create a matching quiz for kids that suits their age and education level.

Presentation on theme: «Лексикология. Лекция 3. Морфологическая структура.»— Presentation transcript:

1

Лексикология. Лекция 3. Морфологическая структура.

M o r p h e m e s the smallest indivisible meaningful language units Allomorphs (m o r p h e m e v a r i a n t s) — all the representations of the given morpheme that manifest alteration please, pleas -ing, pleas -ure, pleas –ant Stem — the part of the word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm. The stem of the paradigm hearty — heartier — (the) heartiest is hearty-. .

2

Simple Derived Free Bound STEM

3

Stem When a derivational or functional affix is stripped from the word, what remains is a stem (or astern base). The stem expresses the lexical and the part of speech meaning. For the paradigm heart (sing.) —hearts (pl.) the stem may be represented as heart-. This stem is a single morpheme, it contains nothing but the root, so it is a simple stem. It is also a free stem because it is homonymous to the word heart. A stem may also be defined as the part of the word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm. The stem of the paradigm hearty — heartier — (the) heartiest is hearty-. It is a free stem, but as it consists of a root morpheme and an affix, it is not simple but derived.

4

Classification of stems

Bound stems are especially characteristic of loan words. The point may be illustrated by the following French borrowings: arrogance, charity, courage, coward, distort, involve, notion, legible and tolerable. After the affixes of these words are taken away the remaining elements are: arrog-, char-, cour-, cow-, -tort, -volve, not-, leg-, toler-, which do not coincide with any semantically related independent words.

5

The Word and the Morpheme

The correlation between the word and the morpheme is problematic There is a set of intermediary units (half-words — half-morphemes) Jack’s, a boy, have done.

6

This approach to treating various lingual units is known in linguistics as “a field approach”: polar phenomena possessing the unambiguous characteristic features of the opposed units constitute “the core”, or “the center” of the field, while the intermediary phenomena combining some of the characteristics of the poles make up “the periphery” of the field; e.g.: functional words make up the periphery of the class of words since their functioning is close to the functioning of morphemes

7

Semi-affixes Semi-affixes are morphemes that are bound but which retain a word-like quality. Examples are: anti-, counter-, -like and -worthy. So we can have: anti-clockwise or anticlockwise counter-example or counterexample bird-like or birdlike note-worthy or noteworthy

8

COMBINING FORM A combining form is a type of word component based on an independent word that has been modified to be joined with another word or combining form to create a compound word. 1.Every combining form has its own semantic meaning, but unlike their source words, combining forms generally cannot stand alone as complete words by themselves. 2. Combining forms are part of many English words and are especially common in areas such as science, medicine, and technological terms.

9

COMBINING FORM 3. In English and many other European languages, combining forms are frequently based on Latin or classical Greek words, and so compound words made from them are commonly called classical compounds. 4. The English versions can sometimes be several steps removed from their original language. For example, the suffix -graphy originated as the English version of the French -graphie, which comes from the Latin -graphia. The Latin term, in turn, comes from the Greek graphein, which means to write.

10

Combining forms 5. Combining forms are even more word-like than semi-affixes and frequently occur in technical literature, for instance Indo-European or gastro-enteritis. 6. Some words can be made up entirely from bound forms, but without a free morpheme, e.g. Francophile.

11

Combining forms kilometer: kilo- (comb. f.) metro (word).

autotroph: auto- (comb. f.) -troph (comb. f.). electrocardiogram: electro- (comb. f.) cardio- (comb. f.) -gram (comb. f.). hydroxylic: hydro- (comb. f.) ox- (comb. f.) -yl (comb. f.) –ic (suffix). chloride: chlor- (comb. f.) -ide (suffix). diathermy: dia- (prefix) -thermy (comb. f.).

12

Combining forms • There are combining forms that always precede another lexical element, therm- / thermo- (precedes): thermo-electric, thermo-dynamic, thermometer, thermo-nuclear. others always follow them, -gram (follows): dactylogram — отпечаток пальцев, histogram — гистограмма and finally there are combining forms that can precede or follow a word: phono- / phon- o –phone (precedes or follows): tele-phone, allo-phone, phono-graph, phono-logy • The origin of most of them is Greek or Latin, though there are some exceptions, as atto- and femto-, from Norwegian and Danish.

13

Three types of morphemic segmentability

c o m p l e t e (живое членение слов) , c o n d i t i o n a l (условное членение слов) d e f e c t i v e (дефектное членение слов) .

14

words segmentable fearless Non-segmentable girl

15

C o n d i t i o n a l morphemic segmentability

characterises words whose segmentation into the constituent morphemes is doubtful for semantic reasons. pseudo-morphemes or quasi-morphemes cf. retain, detain or receive, deceive, re-organise, deorganise, decode

16

D e f e c t i v e morphemic segmentability

the property of words whose component morphemes seldom or never recur in other words. a unique morpheme cf. lionet, cellaret – pocket ringlet, leaflet – hamlet

17

Classification of morphemes

root-morphemes (roots) Roots express the concrete, “material” part of the meaning of the word and constitute its central part affixal (derivational) morphemes (affixes). Affixes express the specificational part of the meaning of the word: they specify, or transform the meaning of the root.

18

An affix is not-root or a bound morpheme that modifies the meaning and / or syntactic category of the stem in some way. Affixes are classified into prefixes, suffixes, infixes, interfixes.

19

THE SEMANTIC CRITERION

lexical, or word-building (derivational) affixes together with the root constitute the stem of the word grammatical, or word-changing affixes express different morphological categories, such as number, case, tense and others.

20

Classification of morphemes

Prefixes in English are only lexical: the word underestimate is derived from the word estimate with the help of the prefix under-.

21

Classification of morphemes

A suffix is a morpheme following the root forming a new derivative in a different word class (-en, -y, -less in heart-en, heart-y, heart-less) or expressing different morphological categories

22

Classification of morphemes

Suffixes in English lexical or grammatical (inflexions, inflections, inflectional endings) underestimates: -ate is a lexical suffix, because it is used to derive the verb estimate (v) from the noun esteem (n), –s is a grammatical suffix making the 3rd person, singular form of the verb to underestimate.

23

Grammatical suffixes Grammatical suffixes in English have certain peculiarities: since they are the remnants of the old inflectional system, there are few (only six) remaining word-changing suffixes in English: -(e)s, -ed, — ing, — er, — est, — en; most of them are homonymous, e.g. -(e)s is used to form the plural of the noun (dogs), the genitive of the noun (my friend’s), and the 3rd person singular of the verb (works); some of them have lost their inflectional properties and can be attached to units larger than the word, e.g.: his daughter Mary’s arrival.

24

Suffixes can be classified into different types in accordance with different principles:

According to the lexical-grammatical character of the base suffixes are usually added to, they may be: deverbal suffixes (those added to the verbal base): -er (builder); -ing (writing); denominal suffixes (those added to the nominal base): — less (timeless); -ful (hopeful); -ist (scientist); -some (troublesome); deajectival suffixes (those added to the adjectival base): — en (widen); -ly (friendly); -ish (whitish); -ness (brightness).

25

According to the part of speech formed suffixes fall into several groups:

noun-forming suffixes: -age (breakage, bondage); -ance/- ence (assistance, reference); -dom (freedom, kingdom); — er (teacher, baker); -ess (actress, hostess); -ing (building, wasing); adjective-forming suffixes: -able/-ible/-uble (favourable, incredible, soluble); -al (formal, official); -ic (dynamic); — ant/-ent (repentant, dependent); numeral-forming suffixes: -fold (twofold); -teen (fourteen); -th (sixth); -ty (thirty); verb-forming suffixes: -ate (activate); -er (glimmer); -fy/- ify (terrify, specify); -ize (minimize); -ish (establish); adverb-forming suffixes: -ly (quickly, coldly); -ward/- wards (backward, northwards); -wise (likewise).

26

Semantically suffixes fall into:

Monosemantic: the suffix -ess has only one meaning ‘female’ – tigress, taloress; Polysemantic: the suffix -hood has two meanings: ‘condition or quality’ – falsehood, womanhood; ‘collection or group’ – brotherhood.

27

According to their generalizing denotational meaning suffixes may fall into several groups. E.g., noun-suffixes fall into those denoting: the agent of the action: -er (baker); -ant (accountant); appurtenance: -an/-ian (Victorian, Russian); -ese (Chinese); collectivity: -dom (officialdom); -ry (pleasantry); diminutiveness:-ie (birdie); -let (cloudlet); -ling (wolfling).

28

According to their stylistic reference suffixes may be classified into:

those characterized by neutral stylistic reference: -able (agreeable); -er (writer); — ing (meeting); those having a certain stylistic value: -oid (asteroid); -tron (cyclotron). These suffixes occur usually in terms and are bookish.

29

Classification of morphemes

A prefix is a derivational morpheme preceding the root-morpheme and modifying its meaning (understand – mis-understand, correct – in-correct).

30

Prefixes can be classified according to different principles

According to the lexico-grammatical character of the base prefixes are usually added to, they may be: deverbal (those added to the verbal base): re- (rewrite); over- (overdo); out- (outstay); denominal (those added to the nominal base): — (unbutton); de- (detrain); ex- (ex-president); deadjectival (those added to the adjectival base): un- (uneasy); bi- (biannual). deadverbial (those added to the adverbial base): un- (unfortunately); in- independently).

31

adverb-forming prefixes: un- (unfortunately); up- (uphill).

According to the class of words they preferably form prefixes are divided into: verb-forming prefixes: en-/em- (enclose, embed); be- (befriend); de- (dethrone); noun-forming prefixes: non- (non-smoker); sub- (sub- (subcommittee); ex- (ex- husband) adjective-forming prefixes: un- (unfair); il- (illiterate); ir- (irregular); adverb-forming prefixes: un- (unfortunately); up- (uphill).

32

Semantically prefixes fall into:

Monosemantic: the prefix ex- has only one meaning ‘former’ – ex-boxer; Polysemantic; the prefix dis- has four meanings: ‘not’ (disadvantage); ‘reversal or absence of an action or state’ (diseconomy, disaffirm); ‘removal of’ (to disbranch); ‘completeness or intensification of an unpleasant action’ (disgruntled).

33

According to their generalizing denotational meaning prefixes fall into:

negative prefixes: un- (ungrateful); non- (nonpolotical); in- (incorrect); dis- (disloyal); a- (amoral); reversative prefixes: un2- (untie); de- (decentralize); dis2- (disconnect); pejorative prefixes: mis- (mispronounce); mal- (maltreat); pseudo- (pseudo-scientific); prefixes of time and order: fore- (foretell); pre- (pre-war); post- (post-war), ex- (ex-president); prefix of repetition: re- (rebuild, rewrite); locative prefixes: super- (superstructure), sub- (subway), inter- (inter-continental), trans- (transatlantic).

34

These prefixes are of a literary-bookish character.

According to their stylistic reference prefixes fall into: those characterized by neutral stylistic reference: over- (oversee); under- (underestimate); un-(unknown); those possessing quite a definite stylistic value: pseudo- (pseudo-classical); super- (superstructure); ultra- (ultraviolet); uni- (unilateral); bi- (bifocal). These prefixes are of a literary-bookish character.

35

4. PRODUCTIVE AND NON-PRODUCTIVE AFFIXES

The word-forming activity of affixes may change in the course of time. This raises the question of productivity of derivational affixes, i.e. the ability of being used to form new, occasional or potential words, which can be readily understood by the language-speakers. Thus, productive affixes are those used to form new words in this particular period of language development.

36

Some productive affixes

Noun-forming suffixes: -er (manager), -ing (playing), -ness (darkness), -ism1 (materialism), -ist (parachutist), -ism (realism), — -ancy (redundancy), -ry (gimmickry), -or (reactor), -ics (cybernetics). Adjective-forming suffixes -y (tweedy), -ish (smartish), -ed (learned), -able (tolerable), -less (jobless), -ic (electronic). Adverb-forming suffixes -ly (equally) Verb-forming suffixes -ize/-ise (realise), -ate (oxidate), -ify (qualify). Prefixes un- (unhappy), re- (reconstruct), dis- (disappoint)

37

Noun-forming suffixes

Non-productive affixes are the affixes which are not able to form new words in this particular period of language development Noun-forming suffixes -th (truth), -hood (sisterhood), -ship (scholarship). Adjective-forming suffixes -ly (sickly), -some (tiresome), -en (golden), -ous (courageous), -ful (careful) Verb-forming suffix -en (strengthen)

38

The productivity of an affix should not be confused with its frequency of occurrence that is understood as the existence in the vocabulary of a great number of words containing the affix in question. An affix may occur in hundreds of words, but if it is not used to form new words, it is not productive, for instance, the adjective suffix –ful.

39

INFIX regular vowel interchange which takes place inside the root and transforms its meaning “from within” can be treated as an infix, e.g.: a lexical infix – blood – to bleed; a grammatical infix – tooth – teeth.

40

Infixes Grammatical infixes are also defined as inner inflections as opposed to grammatical suffixes which are called outer inflections. Since infixation is not a productive (regular) means of word-building or word-changing in modern English, it is more often seen as partial suppletivity. Full suppletivity takes place when completely different roots are paradigmatically united, e.g.: go – went.

41

INTERFIX An interfix is an affix with little meaning that occurs between two contentful morphemes: Sportsman Linguodidactic Speedometre

There

exist linguistic forms which in modern languages are used as bound

forms although in Greek and Latin from which they are borrowed they

functioned

as independent words. They

constitute

a specific type of linguistic units.

Combining

forms

are particularly frequent in the specialised vocabularies of arts and

sciences. They have long become familiar in the international

scientific terminology. Many of them attain widespread currency

in everyday language:

astron

− star

→ astronomy;

autos

− self

→ automatic;

bios

− life

→ biology;

electron

−

amber → electronics;

ge

− earth

→ geology;

graph

−

to

write → typography;

hydor

−

water

→hydroelectric;

logos

−

speech

→

physiology;

oikos

− house,

habitat →

1) economics,

2)

ecological

system;

philein

− love

→

philology’

phone

− sound,

voice →

telephone;

photos

− light

→

photograph;

skopein

− to

view →

microscope;

tēle

− far

→

telescope.

It

is obvious from the above list that combining forms mostly occur

together with other combining forms and not with native roots. Almost

all of the above examples are international words, each entering a

considerable word-family:

autobiography,

autodiagnosis, automobile, autonomy, autogeni,

autopilot,

autoloader;

bio-astronautics,

biochemistry, bio-ecology, bionics, biophysics;

economics,

economist, economise,

eco-climate, eco-activist, eco-type, eco-catastrophe;

geodesy,

geometry, geography;

hydrodynamic,

hydromechanic, hydroponic, hydrotherapeutic.

hydrography,

phonograph, photograph, telegraph.

lexicology, philology,

phonology.

4. Word — composition. Classification of compound words.

Word — composition

is another type of word-building which is highly productive. That is

when new words are produced by combining two or more stems. The bulk

of compound words is motivated and the semantic relations between the

two components are transparent. This

type of word-building, in which new words are produced by combining

two or more stems, is one of the three most productive types in

Modern English, the other two are conversion and affixation.

Compounds, though certainly fewer in quantity than derived or root

words, still represent one of the most typical and specific features

of English word-structure.

The

great variety of compound types brings about a great variety of

classifications. Compound words may be classified according to the

type of composition and

the linking element;

according to the

part of speech

to which the compound belongs; and within each part of speech

according to the

structural pattern.

It is also possible to subdivide compounds according to other

characteristics, i.e. semantically,

into motivated

and

idiomatic

compounds

(in the motivated ones the meaning of the constituents can be either

direct

or figurative).

Structurally, compounds are distinguished as endocentric

(Eng.

beetroot,

ice—cold,

knee—deep,

babysit,

whitewash.

UA.

землеустрій, сівозміна, літакобудування)

and

exocentric

(Eng.

scarecrow

—

something

that

scares

crows,

UA.

гуртожиток,

склоріз, самопал)

with

the

subgroup

of

bahuvrihi

(Eng.

lazy—bones,

fathead,

bonehead,

readcoat

UA.

шибайголова,

одчайдух, жовтобрюх)

and

syntactic

and

asyntactic

combinations

(Which

of those fellows do you like to command a search-and-destroy

mission? (King); “Now come along, Bridget. I don’t want any

silliness”, she said in her Genghis-Khan-at-height-of-evil

voice (Fielding); Kurtz caught sight of Permutter’s sunken,

I-fooled-you

grin in the wide rearview mirror (King)).

A

classification according to the

type of the syntactic phrase

with which the compound is correlated has also been suggested. Even

so there remain some miscellaneous types that defy classification,

such as phrase

compounds,

reduplicative

compounds,

pseudo-compounds

and quotation

compounds.

The

classification according to the type of composition

establishes the following groups:

1)

The predominant type is a mere juxtaposition without connecting

elements: heartache

n,

heart-beat

n,

heart-break

n,

heart-breaking

adj,

heart-broken

adj,

heart-felt

adj.

2)

Composition with a vowel or a consonant as a linking element. The

examples are very few: electromotive

adj,

speedometer

n,

Afro-Asian

adj,

handicraft

n,

statesman

n.

3)

Compounds with linking elements represented by preposition or

conjunction stems: down-and-out

n,

matter-of-fact

adj,

son-in-law

n,

pepper-and-salt

adj,

wall-to-wall

adj,

up-to-date

adj,

on

the up-and-up adv

(continually improving), up-and-coming,

as

in the following example: No

doubt he’d

had the pick of some up-and-coming jazzmen

in Paris (Wain).

There

are also a few other lexicalised phrases like devil-may-care

adj,

forget-me-not

n,

pick-me-up

n,

stick-in-the-mud

n,

what’s-her

name n.

The

classification of compounds according to the structure of immediate

constituents

distinguishes:

1) compounds

consisting of simple stems: film-star.

Compounds

formed by joining together stems of words already available in the

language and the two ICs of which are stems of notional words are

also called compounds

proper:

ice-cold

(N+A),

ill-luck

(A+N); (UA.

диван-ліжко,

матч-реванш,

лікар-терапевт)

2)

compounds

where at least one of the constituents is a derived stem:

chain-smoker;

3)

compounds

where at least one of the constituents is a clipped stem:

maths-mistress

(in

British English) and math-mistress

(in

American English). The subgroup will contain abbreviations like H-bag

(handbag) or

Xmas

(Christmas), whodunit n (for

mystery novels) considered substandard;

4)

compounds where at least one of the constituents is a compound stem:

wastepaper-basket.

In coordinative

compounds

neither of the components dominates the other, both are structurally

and semantically independent and constitute two structural

and semantic centres, e.g. breath-taking,

self-discipline, word-for ma it on.

Compounds are not

homogeneous in structure. Traditionally three types are

distinguished:

neutral,

morphological

and syntactic.

In neutral

compounds

the process of compounding is realised without any linking elements,

by a mere juxtaposition of two stems, as in blackbird,

shop-window, sunflower, bedroom, tallboy, etc.

There are three subtypes of neutral compounds depending on the

structure of the constituent stems.

The examples above represent

the subtype which may be described as simple

neutral compounds:

they consist of simple affixless stems.

Compounds which have affixes

in their structure are called derived

or

derivational

compounds (compound-derivatives).

E. g. absent-mindedness,

blue-eyed, golden-haired, broad-shouldered, lady-killer, film-goer,

music-lover, honey-mooner, first-nighter, late-comer, newcomer,

early-riser, evildoer.

The productivity of this

type is confirmed by a considerable number of comparatively recent

formations, such as teenager,

babysitter, strap-hanger, fourseater (car

or boat with four seats), doubledecker

(a ship or

bus with two decks). Numerous nonce-words are coined on this pattern

which is another proof of its high productivity: e. g. luncher-out

(a person

who habitually takes his lunch in restaurants and not at home),

goose-flesher

(murder

story).

In

the coining of the derivational compounds two types of word-formation

are at work. The essence of the derivational compounds will be clear

if we compare them with derivatives and compounds proper that possess

a similar structure. Take, for example, brainstraster,

honeymooner and

mill-owner.

The

ultimate constituents of all three are: noun

stem +

noun

stem+-er.

Analysing into immediate constituents, we see that the immediate

constituents (IC’s) of the compound mill-owner

are

two noun stems, the first simple, the second derived: mill+owner,

of

which the last, the determinatum, as well as the whole compound,

names a person. For the word honeymooner

no

such division is possible, since mooner

does

not exist as a free stem. The IC’s are honeymoon+-er,

and

the suffix -er

signals

that the whole denotes a person: the structure is (honey+moon)+-er.

The

process of word-building in these seemingly similar words is

different: mill-owner

is

coined by composition, honeymooner

—

by

derivation

from the compound honeymoon.

Honeymoon being

a compound, honeymooner

is

a derivative. Now brains

trust “a

group of experts” is a phrase, so brainstruster

is

formed by two simultaneous processes —

by

composition and by derivation and may be called a derivational

compound. Its IC’s are (brains+

trust)+-еr.

The

suffix -er

is

one of the productive suffixes in forming derivational compounds.

Other examples of the same pattern are:

backbencher

− an

M.P. occupying the back bench,

do-gooder

− (ironically

used in AmE),

eye-opener

− enlightening

circumstance,

first-nighter

− habitual

frequenter of the first performance of plays,

go-getter

− (colloq.)

a pushing person,

late-comer,

left-hander

− left-handed

person or blow.

Another

frequent type of derivational compounds are the possessive compounds

of the type kind-hearted:

adjective

stem+noun stem+ -ed.

Its

IC’s are a noun phrase kind

heart and

the suffix -ed

that

unites the elements of the phrase and turns them into the elements of

a compound adjective. Similar examples are extremely numerous.

Compounds of this type can be coined very freely to meet the

requirements of different situations.

Very

few go back to Old English, such as one-eyed

and

three-headed,

most

of the cases are coined in Modern English. Examples are practically

unlimited, especially in words describing personal appearance or

character:

-

absent-minded,

bare-legged,

black-haired,

blue-eyed,

cruel-hearted,

light-minded,

ill-mannered,

many-sided,

narrow-minded,

shortsighted,

etc.

The

first element may also be a noun stem: bow-legged,

heart-shaped and

very often a numeral: three-coloured.

The

derivational compounds often become the basis of further derivation.

Cf.

war-minded

→

war-mindedness;

whole-hearted

→

whole-heartedness

→

whole-heartedly,

schoolboyish

→

schoolboyishness;

do-it-yourselfer

→

do-it-yourselfism.

The

process is also called phrasal

derivation:

mini-skirt

→

mini-skirted,

nothing

but →

nothingbutism,

dress

up →

dressuppable,

Romeo-and-Julietishness,

or

quotation

derivation

as when an unwillingness to do anything is characterised as

let-George-do-it-ity.

All

these are nonce-words, with some ironic or jocular connotation.

The third subtype of neutral

compounds is called contracted

compounds.

These

words have a shortened (contracted) stem in their structure: TV-set

(-program, -show, -canal, etc.),

V-day

(Victory day), G-man (Government man “FBI

agent”), H-bag

(handbag), T-shirt, etc.

Morphological compounds

are few in number. This type is non-productive. It is represented by

words in which two compounding stems are combined by a linking vowel

or consonant, e. g. Anglo-Saxon,

Franko-Prussian, handiwork, handicraft, craftsmanship, spokesman,

statesman.

Syntactic compounds

(the term is arbitrary) are formed from segments of speech,

preserving in their structure numerous traces of syntagmatic

relations typical of speech: articles, prepositions, adverbs, as in

the nouns lily-of-the-valley,

Jack-of-all-trades, good-for-nothing, mother-in-law, sit-at-home.

Syntactical

relations and grammatical patterns current in present-day English can

be clearly traced in the structures of such compound nouns as

pick-me-up,

know-all, know-nothing, go-between, get-together, whodunit. The

last word (meaning “a detective story”) was obviously coined from

the ungrammatical variant of the word-group who

(has) done it.

In reduplication

new words

are made by doubling a stem, either without any phonetic changes as

in bye-bye

(coll, for

good-bye)

or with a

variation of the root-vowel or consonant as in

ping-pong, chit-chat (this

second type is called gradational

reduplication).

This type of word-building

is greatly facilitated in Modern English by the vast number of

monosyllables. Stylistically speaking, most words made by

reduplication represent informal groups: colloquialisms and slang:

walkie-talkie − a

portable radio;

riff-raff − the

worthless or disreputable element of society;

chi-chi − sl.

for chic as

in a chi-chi

girl.

In a modern novel an angry

father accuses his teenager son of doing

nothing but dilly-dallying all over the town.

(dilly-dallying

—

wasting time,

doing nothing, loitering)

Another example of a word

made by reduplication may be found in the following quotation from

The

Importance of Being Earnest by

O. Wilde:

Lady Bracknell.

I think it is high time that Mr. Bunbury made up his mind whether he

was going to live or to die. This shilly-shallying with the question

is absurd. (shilly-shallying

—

irresolution,

indecision)

The structure of most

compounds is transparent, as it were, and clearly betrays the origin

of these words from word-combinations: leg-pulling,

what-iffing,

what-iffers,

up-to-no-gooders,

breakfast-in-the-bedder

(“a

person who prefers to have his breakfast in bed”), etc.

There

are two

important peculiarities distinguishing compounding in English from

compounding in other languages.

Firstly, both immediate constituents of an English compound are free

forms, i.e. they can be used as independent words with a distinct

meaning of their own. The conditions of distribution will be

different but the sound pattern the same, except for the stress. The

point may be illustrated by a brief list of the most frequently used

compounds studied in every elementary course of English: afternoon,

anyway, anybody, anything, birthday, day-off, downstairs, everybody,

fountain-pen, grown-up, ice-cream, large-scale, looking-glass,

mankind,

mother-in-law, motherland, nevertheless, notebook, nowhere,

post-card,

railway, schoolboy, skating-rink, somebody, staircase, Sunday.

The combining elements in Russian and Ukrainian

are as a rule bound forms

руководство,

жовто-блакитний,

соціально-політичний, землекористування,

харчоблок, but

in English combinations like

Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Soviet, Indo-European

socio-political

or politico-economical

or medicochirurgical

where the first elements are bound

forms, occur very rarely and seem to be avoided. They are coined on

the neo-Latin pattern.

In Ukrainian compound

adjectives of the type

соціально-політичний,

історико-філологічний, народно-демократичний,

are very

productive, have no equivalent compound adjectives in English and are

rendered by two adjectives:

газонафтова

компанія — gas

and oil company

фінансово-політична

група — financial

political group

військово-промисловий

комплекс —

military

industrial complex

The

second feature

that should attract attention is that the regular pattern for the

English language is a two-stem compound, as is clearly testified by

all the preceding examples. An exception to this rule is observed

when the combining element is represented by a form-word stem, as

in mother-in-law,

bread-and-butter, whisky-and-soda, deaf-and-dumb, good-for-nothing,

man-of-war, mother-of-pearl, stick-in-the-mud.

If,

however, the number of stems is more than two, so that one of the

immediate constituents is itself a compound, it will be more often

the determinant than the determinatum. Thus aircraft-carrier,

waste-paper-basket

are

words, but baby

outfit, village schoolmaster, night watchman

and

similar combinations are syntactic groups with two stresses, or even

phrases with the conjunction and:

book-keeper and typist.

The

predominance of two-stem structures in English compounding

distinguishes it from the German language which can coin

monstrosities like the anecdotal

Vierwaldstatterseeschraubendampfschiffgesellschaft

or

Feuer-

and Unfallversicherungsgesellschaft.

One

more specific feature

of English compounding is the important role the attributive

syntactic function can play in providing a phrase with structural

cohesion and turning it into a compound. Compare:

…

we’ve

done last-minute changes before …(

Priestley)

we

changed it at the

last minute more than once.

four-year

course, pass-fail basis (a

student passes or fails but is not graded).

It

often happens that elements of a phrase united by their attributive

function become further united phonemically by stress and graphically

by a hyphen, or even solid spelling. Cf.

common

sense →

common-sense

advice;

old

age →

old-age

pensioner;

the

records are out of date →

out-of-date

records;

the

let-sleeping-dogs-lie approach (Priestley).

→

Let

sleeping dogs lie (a

proverb).

This

last type is also called quotation

compound

or holophrasis.

The speaker/or writer

creates those combinations freely as the need for them arises: they

are originally nonce-compounds. In the course of time they may become

firmly established in the language:

the ban-the-bomb voice,

round-the-clock duty.

Other

syntactical functions unusual for the combination can also provide

structural cohesion:

working

class →

He

wasn’t

working-class enough.

The

function of hyphenated spelling in these cases is not quite clear. It

may be argued that it serves to indicate syntactical relationships

and not structural cohesion, e. g. keep-your-distance

chilliness. It

is then not a word-formative but a phrase-formative device.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- Identify word parts in medical terms.

- Examine the rules for building medical terms.

Word Parts

Medical terms are built from word parts. Those word parts are , , , and . When a word root is combined with a combining form vowel the word part is referred to as a .

Identifying Word Parts in Medical Terms

By the end of this book, you will have identified hundreds of word parts within medical terms. Let’s start with some common medical terms that many non-medically trained people may be familiar with.

Osteoarthritis

Oste/o/arthr/itis – Inflammation of bone and joint.

Oste/o is a that means bone

arthr/o is a that means joint

-itis is a that means inflammation

Intravenous

Intra/ven/ous – Pertaining to within a vein.

Intra- is a that means within

ven/o – is a that means vein

-ous is a that means pertaining to

Notice, when breaking down words that you place slashes between word parts and a slash on each side of a .

Language Review

Before we begin analyzing the rules let’s complete a short language review that will assist with pronunciation and spelling.

Short Vowels

a, e, i, o, u, and sometimes y are indicated by lower case.

Long Vowels

A, E, I, O, U are indicated by upper case.

Consonants

Consonants are all of the other letters in the alphabet. b, c, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, q, r, s, t, v, w, x, and z.

Language Rules

Language rules are a good place to start when building a medical terminology foundation. Many medical terms are built from word parts and can be translated . At first, literal translations sound awkward. Once you build a medical vocabulary and become proficient at using it, the awkwardness will slip away. For example, suffixes will no longer be stated and will be assumed. The definition of intravenous then becomes within the vein.

Since you are at the beginning of building your medical terminology foundation, stay literal when applicable. It should be noted that as with all language rules there are always exceptions and we refer to those as .

Language Rules for Building Medical Terms

- When combining two , you keep the .

- When combining a with a that begins with a consonant, you keep the .

Gastr/o/enter/o/logy – The study of the stomach and the intestines

- Following rule 1, when we join combining form gastr/o (meaning stomach) with the combining form enter/o (meaning intestines) we keep the combining form vowel o.

- Following rule 2, when we join the combining form enter/o (meaning intestines) with the suffix -logy (that starts with a suffix and means the study of) we keep the combining form vowel o.

- When combining a with a that begins with a vowel, you drop the .

- A goes at the beginning of the word and no is used.

Intra/ven/ous – Pertaining to within the vein

- Following rule 3, notice that when combining the combining form ven/o (meaning vein) with the suffix -ous ( that starts with a vowel and means pertaining to) we drop the combining form vowel o.

- Following rule 4, the prefix intra- (meaning within) is at the beginning of the medical term with no combining form vowel used.

- When defining a medical word, start with the first and then work left to right stating the word parts. You may need to add words. As long as the filler word does not change the meaning of the word you may use it for the purpose of building a medical vocabulary. Once you start to apply the word in the context of a sentence it will be easier to decide which filler word(s) to choose.

Intra/ven/ous – Pertaining to within the vein or Pertaining to within a vein.

- Following rule 5, notice that I start with the suffix -ous (that means pertaining to) then we work left to right starting with the prefix Intra- (meaning within) and the combining form ven/o (meaning vein).

- Notice that we have used two different definitions that mean the same thing.

- In these examples we do not have the context of a full sentence. For the purpose of building a medical terminology foundation either definition is accepted.