From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For paintings and other art incorporating text, see Word art.

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

Historical development[edit]

Tone painting of words goes at least as far back as Gregorian chant. Musical patterns expressed both emotive ideas and theological meanings in these chants. For instance, the pattern fa-mi-sol-la signifies the humiliation and death of Christ and his resurrection into glory. Fa-mi signifies deprecation, while sol is the note of the resurrection, and la is above the resurrection, His heavenly glory («surrexit Jesus«). Such musical words are placed on words from the Biblical Latin text; for instance when fa-mi-sol-la is placed on «et libera» (e.g., introit for Sexagesima Sunday) in the Christian faith it signifies that Christ liberates us from sin through his death and resurrection.[1]

Word painting developed especially in the late 16th century among Italian and English composers of madrigals, to such an extent that word painting devices came to be called madrigalisms. While it originated in secular music, it made its way into other vocal music of the period. While this mannerism became a prominent feature of madrigals of the late 16th century, including both Italian and English, it encountered sharp criticism from some composers. Thomas Campion, writing in the preface to his first book of lute songs in 1601, said of it: «… where the nature of everie word is precisely expresst in the Note … such childish observing of words is altogether ridiculous.»[2]

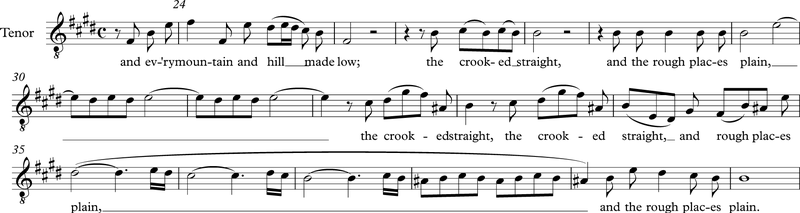

Word painting flourished well into the Baroque music period. One well-known example occurs in Handel’s Messiah, where a tenor aria contains Handel’s setting of the text:[3]

- Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill made low; the crooked straight, and the rough places plain. (Isaiah 40:4)[4]

In Handel’s melody, the word «valley» ends on a low note, «exalted» is a rising figure; «mountain» forms a peak in the melody, and «hill» a smaller one, while «low» is another low note. «Crooked» is sung to a rapid figure of four different notes, while «straight» is sung on a single note, and in «the rough places plain», «the rough places» is sung over short, separate notes whereas the final word «plain» is extended over several measures in a series of long notes. This can be seen in the following example:[5]

In popular music[edit]

There are countless examples of word painting in 20th century music.

One example occurs in the song «Friends in Low Places» by Garth Brooks. During the chorus, Brooks sings the word «low» on a low note.[6] Similarly, on The Who’s album Tommy, the song «Smash the Mirror» contains the line «Rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise….» Each repetition of «rise» is a semitone higher than the last, making this an especially overt example of word-painting.[7]

«Hallelujah» by Leonard Cohen includes another example of word painting. In the line «It goes like this the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift, the baffled king composing hallelujah,» the lyrics signify the song’s chord progression.[8]

Justin Timberlake’s song «What Goes Around» is another popular example of text painting. The lyrics

- What goes around, goes around, goes around

- Comes all the way back around

descend an octave and then return to the upper octave, as though it was going around in a circle.

In the chorus of «Up Where We Belong» recorded by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes, the melody rises during the words «Love lift us up».

In Johnny Cash’s «Ring of Fire», there is an inverse word painting where «down, down, down» is sung to the notes rising, and ‘higher’ is sung dropping from a higher to a lower note.

In Jim Reeves’s version of the Joe Allison and Audrey Allison song «He’ll Have to Go,» the singer’s voice sinks on the last word of the line, «I’ll tell the man to turn the juke box way down low.»

When Warren Zevon sings «I think I’m sinking down,» on his song «Carmelita,» his voice sinks on the word «down.»

In Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s «My Romance,» the melody jumps to a higher note on the word «rising» in the line «My romance doesn’t need a castle rising in Spain.»

In recordings of George and Ira Gershwin’s «They Can’t Take That Away from Me,» Ella Fitzgerald and others intentionally sing the wrong note on the word «key» in the phrase «the way you sing off-key».[9]

Another inverse happens during the song «A Spoonful of Sugar» from Mary Poppins, as, during the line «Just a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down,» the words «go down» leap from a lower to a higher note.

In Follies, Stephen Sondheim’s first time composing the words and music together, the number «Who’s That Woman?» contains the line «Who’s been riding for a fall?» followed by a downward glissando and bass bump, and then the line «Who is she who plays the clown?» followed by mocking saxophone wobbles.

At the beginning of the first chorus in Luis Fonsi’s «Despacito», the music is slowed down when the word «despacito'»(slowly) is performed.

In Secret Garden’s «You Raise Me Up», the words «you raise me up» are sung in a rising scale at the beginning of the chorus.

Queen use word painting in many of their songs (in particular, those written by lead singer Freddie Mercury). In «Somebody to Love», each time the word «Lord» occurs, it is sung as the highest note at the end of an ascending passage. In the same piece, the lyrics «I’ve got no rhythm; I just keep losing my beat» fall on off beats to create the impression that he is out of time.

Queen also uses word painting through music recording technology in their song «Killer Queen» where a flanger effect is placed on the vocals during the word «laser-beam» in bar 17.[10]

In Mariah Carey’s 1991 single Emotions word painting is used throughout the song. The first use of word painting is in the lyric «deeper than I’ve ever dreamed of» where she sings down to the bottom of the staff, another example is also in the lyric «You make me feel so high» with the word «high» being sung with arpeggios with the last note being an E7

In Miley Cyrus’ ‘Wrecking Ball’, every time the title of the song is mentioned, all instruments engage in one huge wall of sound, therefore mimicking the sound of a wrecking ball whenever the chorus comes in.

Burt Bacharach uses word-painting in the song ‘In Between the Heartaches’ from Dionne Warwick’s Here_I_Am album. The song opens on an A-flat minor 11th chord. Dionne sings on the 11th of the chord (on the words…’In Between…’); a high E-flat briefly (on the word ‘the’); and back to the 11th and the 9th of the chord (on the word…’Heartaches…’) Those notes fall IN BETWEEN the notes of an A-flat minor triad (A-flat, C-flat, E-flat) making it a highly sophisticated example of word-painting.

See also[edit]

- Mickey Mousing

- Musica reservata

- Program music

- Eye music

References[edit]

- ^ Krasnicki, Ted. «The Introit For Sexagesima Sunday». New Liturgical Movement.

- ^ Thomas Campion, First Booke of Ayres (1601), quoted in von Fischer, Grove online

- ^ Jennens, Charles, ed. (1749). Messiah – via Wikisource.

- ^ «Isaiah#Chapter 40» . Bible (King James). 1769 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Bisson, Noël; Kidger, David. «Messiah: Listening Guide for Part I». First Nights (Literature & Arts B-51, Fall 2006, Harvard University). The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ «Word painting in songwriting…» The Song Writing Desk. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Ellul, Matthew. «How to Write Music». School of Composition. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Ellul, Matthew. «How to Write Music». School of Composition. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ «A LEVEL Performance Studies: George Gershwin» (PDF). Oxford Cambridge and RSA (Version 1): 16. September 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ «Queen: ‘Killer Queen’ from the album Sheer Heart Attack» (PDF). Pearson Schools and FE Colleges. Area of study 2: Vocal Music: 97. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

Sources[edit]

- M. Clement Morin and Robert M. Fowells, «Gregorian Musical Words», in Choral essays: A Tribute to Roger Wagner, edited by Williams Wells Belan, San Carlos (CA): Thomas House Publications, 1993

- Sadie, Stanley. Word Painting. Carter, Tim. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Second edition, vol. 27.

- How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, Part 1, Disc 6, Robert Greenberg, San Francisco Conservatory of Music

Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Mr. Clemens Kub

Score: 5/5

(64 votes)

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is characteristics of use of word painting?

Word painting is a compositional style of setting the melody so it vividly depicts the imagery, and actions taking place in the music. For instance words with a negative connotation such as descending, death, ground,etc. will have a melody with a downward movement of pitch.

What is the use of word painting?

Musical depiction of words in text. Using the device of word painting, the music tries to imitate the emotion, action, or natural sounds as described in the text. For example, if the text describes a sad event, the music might be in a minor key.

What is word painting in literature?

n. 1. The technique of using the phonic qualities of words to suggest or reinforce their meaning, especially in poetry.

Which genre uses word painting?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

35 related questions found

How do you describe the word painting in music?

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is the definition of word painting in music?

Word painting is when the melody of a song actually reflects the meaning of the words. The best way to learn about it is to listen.

Which of the following would be the best definition of word painting?

Word painting is when the music describes the action. … An example of word painting would be when someone is going down a hill, the music descends as well.

What is the difference between word painting and declamation?

How a text is set to music is called its declamation. Recitative and word painting are two types of musical declamation: recitative is a speech-like, declamatory singing style that emphasizes the important syllables and words of the text, while word painting is a musical illustration of a word being sung.

What is word painting give a brief example?

Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa. For example, singing the word “stop” as the music cuts out. Depending on which you write first (music or lyrics) it can be carried out in any order.

What is word painting MUS 121?

What is word painting? A musical concept in which melodies depict specific words that are sung (like notes going higher in pitch on the word «ascend»).

How do you describe the texture of a song?

Texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices.

What is the definition of word painting quizlet?

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of writing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

How did Renaissance composers use word painting in their music?

Word painting was utilized by Renaissance composers to represent poetic images musically. For example, an ascending me- lodic line would portray the text “ascension to heaven.” Or a series of rapid notes would represent running.

How is word painting used in as Vesta was descending?

“Vest” from vesta is the strong pulse. “From Latmos Hill” is always a three-note ascending motif in imitative counterpoint to illustrate a hill, and then when the voices sing “descending,” the scale reverses and descends. This is the first demonstration of word painting in this composition.

What is the tone of a painting?

In painting, tone refers to the relative lightness or darkness of a colour (see also chiaroscuro). One colour can have an almost infinite number of different tones. Tone can also mean the colour itself.

What is abstract art with words?

Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect. Wassily Kandinsky. Cossacks 1910–1. Tate. Strictly speaking, the word abstract means to separate or withdraw something from something else.

What is the definition of a chanson?

: song specifically : a music-hall or cabaret song.

Where did the word painting come from?

1300, «decorate (something or someone) with drawings or pictures;» early 14c., «put color or stain on the surface of; coat or cover with a color or colors;» from Old French peintier «to paint,» from peint, past participle of peindre «to paint,» from Latin pingere «to paint, represent in a picture, stain; embroider, …

Which is true of an aria?

What is true of recitatives? An aria is: … and extended piece for a solo singer having more musical elaboration and a steadier pulse than recitative.

Which of the following are known Madrigalists?

Some of the best known of the English madrigalists include Thomas Morley (1558-1602), Francis Pilkington (ca. 1570-1638), William Byrd (1543-1623), Orlando Gibbons(1583-1625), and Thomas Weelkes (1576-1623).

Which composer used word painting which used music to reflect the literal meaning of the words?

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Handel’s music is the use of “word-painting,” the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What is the texture of Renaissance?

The texture of Renaissance music is that of a polyphonic style of blending vocal and instrumental music for a unified effect.

What is a melismatic melody?

Melisma (Greek: μέλισμα, melisma, song, air, melody; from μέλος, melos, song, melody, plural: melismata) is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. … An informal term for melisma is a vocal run.

Word painting in songwriting…

Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa.

For example, singing the word “stop” as the music cuts out.

Depending on which you write first (music or lyrics) it can be carried out in any order.

It’s a fantastic songwriting concept that adds depth and sophistication to your music. As well as being extremely effective when trying to drive home a point, it can also be wonderfully satisfying for an attentive listener. It doesn’t always have to be the lyrical relationship to the music either. It may be the way you sing something to place importance on a particular word or phrase.

For example, Garth Brooks sings the word “low” much deeper than the rest of the lyrics in the track “Friends in Low Places”.

The truth is there are infinite ways of going about word painting, it all depends on your song.

A great word painting is one that creates a “moment” in a song. A brief play on music and lyrics that makes an impression on the listener acting like a sort of treat thrown into the mix. Created “moments” in songs are signs of a well-rounded songwriter. They present an understanding that the relationship between music and lyrics is often more important than a lot of people think.

Let’s take a look at some popular examples and go through why they work so well. Once you have a firm grip on the concept of word painting you can start applying the lyrical and musical technique to your own songs…

MC Hammer — U cant touch this

Perhaps one of the most clean-cut examples of word painting. MC Hammer says “stop” as the music stops.

This particular word painting has become etched into our brains. The result no doubt would have been less memorable if the music carried on as he said “stop”.

Here he has shown a solid understanding that sometimes its the silence in-between the notes that have the most impact.

Queen — Another one bites the dust

One of our favorite examples occurs in this song. At 0:39, shortly after Mercury sings a line about machine guns and bullets ripping, the snare drum mimic’s the sound of a machine gun firing.

This creates intensity and evokes imagery perfectly. This is used a couple of times throughout the song.

On a side note, although not strictly a word painting, Queen has picked a very deliberate sharp and clean-cut drum groove here. The harsh snare coincides perfectly with the urgent pronunciation of “another one bites the dust”.

Genius work from them.

Nancy Sinatra — Bang Bang (My baby shot me down)

As Sinatra sings the chorus, the guitar follows with descending slides. This adds to the feeling of her being shot down and hitting the ground.

This whole song in-fact is an example of music and lyrics perfectly intertwined, almost as if it were a duet. The guitar being one performer and Nancy the other, each responding and reacting to one another.

Jeff Buckley — Hallelujah

Another stunning example of a word painting is in the song “Hallelujah” (every version).

The lyrics describe what chord is being played as they are sung.

“It goes like this,

The fourth,

The fifth,

The minor fall,

And the major lift,”

This is sophisticated songwriting. This word painting lasts much longer than most word paintings out there and is masterfully done, especially when you take into account the rhyme’s that are achieved here. It’s elegant and deliberate. Perfectly matching the feel of this classic.

Owl City- Fireflies

Not only does the music sound like what you would imagine fireflies look like fluttering in the night sky, here he has also sung the word “slowly” in a drawn-out way.

As well as this, after the line “ a disco ball just hanging by a thread” the music stops completely. Almost suggesting that it snaps and falls as the beat returns.

These give the song character and playfulness which encapsulates the vibe of the song well.

Jack Johnson- Never know

Here the side stick snare follows along when Jack sings “knock-knock” at 2:22 as if someone is actually knocking on a door.

This lends it’s self to the smooth sound of the track, subtly playing around with the music and lyrics.

Mötley Crüe — Shout at the devil

Aside from being a particularly aggressive track to begin with. Here the word “shout” have been shouted. Placing deeper importance on those particular words.

The Mackayz — Tea strike

Here is an example of a word painting achieved through lyrics rather than both music and lyrics. At 0:45 the backing vocals sing the word “high” in an ascending way, moving from a low note ending on a higher one.

This creates a moment unlike any other throughout the track, filling your ears with musical candy that gives the track attitude and style.

These are just a few examples that have been used but there are many many more scattered throughout popular music. Keep an ear out for them as they can become quite addicting to try and find. Use them cleverly within your music. Be sure not to overdo them. Less seems to be more here, as they can become predictable if overused. They can serve as memorable parts to great music however, so mess around and enjoy trying to create them.

Get painting!

- Home

- Tips and Techniques

- Word painting

›

›

Asked by: Dr. Torrey Casper I

Score: 5/5

(10 votes)

Word painting is when the melody of a song actually reflects the meaning of the words. The best way to learn about it is to listen.

What is word painting give a brief example?

Musical depiction of words in text. Using the device of word painting, the music tries to imitate the emotion, action, or natural sounds as described in the text. For example, if the text describes a sad event, the music might be in a minor key. Conversely, if the text is joyful, the music may be set in a major key.

Which genre uses word painting?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

What is characteristics of use of word painting?

Word painting is a compositional style of setting the melody so it vividly depicts the imagery, and actions taking place in the music. For instance words with a negative connotation such as descending, death, ground,etc. will have a melody with a downward movement of pitch.

What is paint music?

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

45 related questions found

What is the difference between word painting and declamation?

How a text is set to music is called its declamation. Recitative and word painting are two types of musical declamation: recitative is a speech-like, declamatory singing style that emphasizes the important syllables and words of the text, while word painting is a musical illustration of a word being sung.

How did Renaissance composers use word painting in their music?

Word painting was utilized by Renaissance composers to represent poetic images musically. For example, an ascending me- lodic line would portray the text “ascension to heaven.” Or a series of rapid notes would represent running.

What is word painting MUS 121?

What is word painting? A musical concept in which melodies depict specific words that are sung (like notes going higher in pitch on the word «ascend»).

When did word painting become popular?

This word painting became very popular during renaissance era, but it died out in baroque era as many composers thought it was artificial and childish way to express emotions. Then we saw this technique again in Bach’s music. Bach adopts word painting in order to help people to reflect on the divine.

How is word painting used in as Vesta was descending?

“Vest” from vesta is the strong pulse. “From Latmos Hill” is always a three-note ascending motif in imitative counterpoint to illustrate a hill, and then when the voices sing “descending,” the scale reverses and descends. This is the first demonstration of word painting in this composition.

What is a Organa in music?

organum, plural Organa, originally, any musical instrument (later in particular an organ); the term attained its lasting sense, however, during the Middle Ages in reference to a polyphonic (many-voiced) setting, in certain specific styles, of Gregorian chant.

Which composer used word painting which used music to reflect the literal meaning of the words?

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Handel’s music is the use of “word-painting,” the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What is the definition of word painting quizlet?

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of writing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What does through composed mean in music?

of a song. : having new music provided for each stanza — compare strophic.

Which is true of an aria?

What is true of recitatives? An aria is: … and extended piece for a solo singer having more musical elaboration and a steadier pulse than recitative.

What is the German word for art song?

Songs in classical music are usually called «art songs.» In German, art songs are called Lieder. Franz Schubert was a master of writing Lieder.

What is it called when a singer goes up and down?

Vibrato (Italian, from past participle of «vibrare», to vibrate) is a musical effect consisting of a regular, pulsating change of pitch. It is used to add expression to vocal and instrumental music.

What is musical tone painting composition?

Tone painting is the technique of shaping vocal music according to the meaning of the words. For example, we’d write a melody that goes up on words such as ‘rising’, ‘uphill’ and ‘climbing’ or have the music go really quiet on words such as ‘soft’, ‘peaceful’ and ‘calm’.

What is the tone of a painting?

In painting, tone refers to the relative lightness or darkness of a colour (see also chiaroscuro). One colour can have an almost infinite number of different tones. Tone can also mean the colour itself.

What is abstract art with words?

Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect. Wassily Kandinsky. Cossacks 1910–1. Tate. Strictly speaking, the word abstract means to separate or withdraw something from something else.

What does the word melisma mean?

1 : a group of notes or tones sung on one syllable in plainsong. 2 : melodic embellishment. 3 : cadenza.

What is the difference between English and Italian madrigals?

The English madrigals were more humorous and lighter, with simpler harmony and melody than the Italian madrigals. Italian also madrigals often had way more word painting to convey the deep emotion that it had. … The text in this poem also very lighthearted especially compared to the Italian madrigal.

What does Madrigalism mean?

MA-dri-gahl-izm. [English] A term used to describe the illustrative devices used particularly in madrigals. This includes text painting, for example: changing the texture, tone, range, or volume to musically depict what the text is describing.

“There’s no love song finer, but how strange the change from major to minor, everytime we say goodbye.”

In the line above from Cole Porter’s “Every Time We Say Goodbye,” we’re moved from the happiness of love to the sadness of parting, and so too do the chords change, from major to minor, thus subtly changing the mood of the song. The technique is a clever example of a songwriting method called “word painting,” or prosody, when lyrics are accompanied by a rhythmic, melodic, or harmonic shift that complements their meaning. We hear it in pop music all the time, drawing our attention to significant moments, and shaping the emotional impact of words and phrases.

The word “Stop,” for example, appears over and over in pop music, as the video above from David Bennett shows, accompanied by a full stop from the band. Spanish-language hit “Despacito” (which means “slowly”) slows the tempo while the titular word is sung. There are innumerable examples of melodies rising and falling to lyrics like “high, up, down” and “low.” A more sophisticated example of word paining comes from Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” which tells us exactly what the music’s doing — “It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall, the major lift.”

As ingenious as these moves are, Bennett goes on to show us how word painting can be “even more nuanced” in classics like The Doors’ “Riders on the Storm.” As Ray Manzarek himself explains in an interview clip, his keyboard part led to an onomatopoeia effect: lyrics, melody, and sound effects all coming together to express the entire theme. Bennett shows in his second word painting video, above, how studio effects can also be used to sync music and lyrics, such as the murky eq effect applied to Billie Eilish’s voice on the word “underwater” in her song “Everything I Wanted.”

Examples of effects like this date back at least to Jimi Hendrix, who pioneered the studio as a songwriting tool, but word painting as a songwriting method requires no special technology. The Jackson Five’s “ABC,” for instance, lands on E♭ and C during the line “I before E except after C,” and the famous chorus is sung to the notes A♭, B♭m7, and C. Here, the notes themselves tell the story, simple but undoubtedly effective. All of the examples Bennett adduces may come from popular music, but word painting is as old as poetry, which was once inseparable from song. For as long as humans have communicated with literary epics, funeral rites, tragedies, comedies, and love songs, we have used prosody to shape words with music, and music according to the meaning of our words.

Related Content:

Tom Petty Takes You Inside His Songwriting Craft

Nakedly Examined Music Podcast Explores Songwriting with Cracker, King Crimson, Cutting Crew, Jill Sobule & More

How David Bowie Used William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Method to Write His Unforgettable Lyrics

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Which of the following is an example of word painting?

Word painting is when the music describes the action. Word painting was popular in 16th century secular music. An example of word painting would be when someone is going down a hill, the music descends as well. Thomas Weelkes uses word painting in As Vesta was from Latmos Hill Descending.

What are the types of word painting?

Painting can be a verb or a noun – Word Type.

Word painting is when the melody of a song actually reflects the meaning of the words.

How do you make a word painting?

Is the word paintings a common noun?

A lamp, chair, couch, TV, window, painting, pillow, candle – all of these items are named using common nouns. Common nouns are everywhere, and you use them all the time, even if you don’t realize it.

What kind of noun is painting?

[uncountable] the act of putting paint onto the surface of objects, walls, etc.

What period is use of word painting in texts and music?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

How do composers use word painting?

Using the device of word painting, the music tries to imitate the emotion, action, or natural sounds as described in the text. For example, if the text describes a sad event, the music might be in a minor key. Conversely, if the text is joyful, the music may be set in a major key.

Where does the word painting originated from?

1300, “decorate (something or someone) with drawings or pictures;” early 14c., “put color or stain on the surface of; coat or cover with a color or colors;” from Old French peintier “to paint,” from peint, past participle of peindre “to paint,” from Latin pingere “to paint, represent in a picture, stain; embroider, …

Does Handel use word painting?

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Handel’s music is the use of “word-painting,” the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics.

Why do madrigal composers use word painting?

Madrigals are secural. One of the strongest, and most recognizable characteristics used in madrigal is word painting. Word painting is a compositional style of setting the melody so it vividly depicts the imagery, and actions taking place in the music.

Is word painting Baroque?

Composers also experimented with word painting in Italian madrigals of the 16th and 17th centuries. Word painting flourished well into the Baroque music period.

What is the word painting in the Hallelujah Chorus?

Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa.

Is melisma a word painting?

This example can also be described as “word painting”. Handel uses the melisma to make it sound like someone shaking something. Melismas are used a lot in music from many different cultures.

What is the form of hallelujah chorus?

The Hallelujah chorus is written in the key of D major and includes big instruments like trumpets and timpani. The form is through-composed (which basically just means it’s random), but it does have a refrain – when the voices sing “hallelujah”. The text from this part is from the Book of Revelations, 19:6.

What is the definition of word painting quizlet?

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of writing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What is Handel’s Messiah an example of?

Handel’s ‘Messiah’ is a triumphant example of ‘word painting‘

What is expressed by the music when the word exalted is sung in EV Ry Valley?

Handel continues with this uplifting mood and tone in the first aria of Messiah, “Ev’ry Valley Shall Be Exalted.” The words for this aria also come from Isaiah. They relate to the people the coming of the Lord. This piece announces that no mountain or valley shall stand in the way of the coming of the Messiah.

What is a castrato quizlet?

castrato. A male singer who was castrated before puberty so that his voice would remain high. Castratos often sang hero roles in baroque operas and were hired by the Catholic Church, which did not want women to sing in the church services. Chorus.

How is the madrigal is best defined?

The madrigal is best described as: a popular genre of secular vocal music, originating in Italy, in which four or five voices sing love poems. Identify the correct definition for “word painting.” the process of depicting the text in music, be it subtly, overtly, or even jokingly, by means of expressive musical devices.

What do we mean when we say melismatic?

(mə-lĭz′mə) pl. me·lis·ma·ta (-mə-tə) or me·lis·mas. A passage of multiple notes sung to one syllable of text, as in Gregorian chant. [Greek, melody, from melizein, to sing, from melos, song.]

Did castrati received the highest fees of any musicians?

Castrati received the highest fees of any musicians. 1600 to 1800; it was usually done with the consent of impoverished parents who hoped their sons would become highly paid opera stars. combined the lung power of a man with the vocal range of a woman.

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is an example of word painting?, Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa. For example, singing the word “stop” as the music cuts out. … For example, Garth Brooks sings the word “low” much deeper than the rest of the lyrics in the track “Friends in Low Places”.

Furthermore, What is use of word painting in texts and music?, Word–painting (Ger.

The use of musical gesture(s) in a work with an actual or implied text to reflect, often pictorially, the literal or figurative meaning of a word or phrase. A common example is a falling line for ‘descendit de caelis’ (‘He came down from heaven’).

Finally, What’s the meaning of painting?, Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a surface. The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and airbrushes, can be used. In art, the term painting describes both the act and the result of the action.

Frequently Asked Question:

What is word painting and in which form of Renaissance music is it used?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

What does word painting mean in music?

Word–painting (Ger.

The use of musical gesture(s) in a work with an actual or implied text to reflect, often pictorially, the literal or figurative meaning of a word or phrase.

What is word painting in Renaissance vocal music?

In the context of Renaissance vocal music, word painting refers to a device often utilized in events and is usually created to reflect or illustrate the text.

How did Renaissance composers use word painting?

Using the device of word painting, the music tries to imitate the emotion, action, or natural sounds as described in the text. … Conversely, if the text is joyful, the music may be set in a major key. This device was used often in madrigals and other works of the Renaissance and Baroque.

What is word painting give examples of word painting?

Word painting is the musical technique of writing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What is the meaning of painting?

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the “matrix” or “support”). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and airbrushes, can be used.

What is the meaning of painting in art?

Painting is the application of pigments to a support surface that establishes an image, design or decoration. In art the term “painting” describes both the act and the result. Most painting is created with pigment in liquid form and applied with a brush.

What is another word for painting?

other words for painting

- art.

- canvas.

- composition.

- depiction.

- landscape.

- picture.

- portrait.

- sketch.

What is the importance of painting in life?

Painting sharpens the mind through conceptual visualization and implementation, plus, boosts memory skills. People using creative outlets such as writing, painting and drawing have less chance of developing memory loss illnesses when they get older.

What does word painting mean in music?

Word–painting (Ger.

The use of musical gesture(s) in a work with an actual or implied text to reflect, often pictorially, the literal or figurative meaning of a word or phrase.

What is word painting and in which form of Renaissance music is it used?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

Which is an example of word painting?

Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa. For example, singing the word “stop” as the music cuts out. … For example, Garth Brooks sings the word “low” much deeper than the rest of the lyrics in the track “Friends in Low Places”.

What is word painting in Renaissance vocal music?

In the context of Renaissance vocal music, word painting refers to a device often utilized in events and is usually created to reflect or illustrate the text.

How do you describe a painting?

Word–painting (Ger.

The use of musical gesture(s) in a work with an actual or implied text to reflect, often pictorially, the literal or figurative meaning of a word or phrase. A common example is a falling line for ‘descendit de caelis’ (‘He came down from heaven’).

What is word painting and in which form of Renaissance music is it used?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

What is word painting in Renaissance vocal music?

In the context of Renaissance vocal music, word painting refers to a device often utilized in events and is usually created to reflect or illustrate the text.

Which of the following would be the best definition of word painting?

Word painting is when the music describes the action. Word painting was popular in 16th century secular music. An example of word painting would be when someone is going down a hill, the music descends as well. … It became popular during the rise of instrumental music in the Renaissance.

Both piece of music are based on texts, aimed to set musing to the settings of the poem. They portray lyrics with music and strive to portray the mood of the poem based on their interpretations.

To achieve this aim, both Schubert and Copland incorporated word painting in their music. “Word painting is musical depiction of words in text” (OnMusic Dictionary). As it is used to reflect the literal meaning of text, this technique is most fitting in its participation of the two music. Two usages of word painting would be used for each piece as examples.

In Der Erlkönig, word painting is used to portray the terrifying and gloomy mood of the poem Der Erlkönig. In m.18-19, word painting is used to describe the sentence “Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind?”. This sentence is a question that can be translated into “Who rides there so late through the night dark and [wind]?”. To portray the wind and the mood of the poem, Schubert uses a leap of fifth to create an abrupt rise in note. This illustrate the sentence as a question but more importantly portray the movement of blowing wind.

Also, at the end of the lied, Schubert adds another word painting to the sentence “In seinen Armen das kind war tot”(translated into ). In here Schubert emphasizes the fact that the child was dead (Kind war tot) through the use of recitative, dynamics, rests, and accidentals.

First of all, recitative was used to minimize the accompaniment and emphasize the vocal line (m.146). Dynamic also contributes to this, having pianissimo and piano (m.146-147). Then the rest is put at m.147 to separate the sentence emphasizing the words. The use of musical elements above aims to signify the disconnect between the father and the child through death. The use of accidental C sharp creates a minor tone, creating a negative mood.

Similar usage can be seen in Copland’s the Chariot. In m.14, word painting is used to sentence “We slowly drove”. As a result, the tempo becomes More slowly (♩=66) from With quiet grace (♩=72-76). Also, the pattern of the dotted notes is expanded. Previously, the dotted rhythm of vocal line was made with dotted eighth note and sixteenth note (m.6), but it is expanded to dotted quarter note and eighth note (m.18).

At the end of the piece, word painting is used to portray one of the main theme of the poem and set the mood. In measure 55, the last syllable of the word eternity is extended over a long period of time. This represents the literal meaning of the word eternity by extending the F note as if it lasts forever. This effect is maximized through the use of poco rit. and fermata, which extends the note. The dynamic (piano) adds to the mood of the music closely resembling quiet mood of the poem.

Both composers have used word painting in their pieces to bring the text into life through music. The texts are illustrated vividly through the use of word painting and the mood of the poem is set nicely by it. I noted that word painting is used at position near the start and at the end. This means that word painting is used to set the music close to the text from the start to the end of the music.

Word painting is when the melody of a song actually reflects the meaning of the words. The best way to learn about it is to listen.

Why do musicians use word painting?

Musical depiction of words in text. Using the device of word painting, the music tries to imitate the emotion, action, or natural sounds as described in the text. For example, if the text describes a sad event, the music might be in a minor key. Conversely, if the text is joyful, the music may be set in a major key.

Which of the following is an example of word painting?

Word painting is when the music describes the action. Word painting was popular in 16th century secular music. An example of word painting would be when someone is going down a hill, the music descends as well. Thomas Weelkes uses word painting in As Vesta was from Latmos Hill Descending.

Which best defines the term word painting?

Identify the correct definition for “word painting.” the process of depicting the text in music, be it subtly, overtly, or even jokingly, by means of expressive musical devices (the musical reflection of the text).

When it comes to the Madrigal What is word painting?

Madrigals are secural. One of the strongest, and most recognizable characteristics used in madrigal is word painting. Word painting is a compositional style of setting the melody so it vividly depicts the imagery, and actions taking place in the music.

What is the difference between word painting and declamation?

How a text is set to music is called its declamation. Recitative and word painting are two types of musical declamation: recitative is a speech-like, declamatory singing style that emphasizes the important syllables and words of the text, while word painting is a musical illustration of a word being sung.

What is the best description of text painting in music?

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is the golden age of acapella music?

The Renaissance period became known as the golden age of a cappella choral music because choral music did not require an instrumental accompaniment.

What is word painting and how was it used in music?

How was word painting used?

Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa. For example, singing the word “stop” as the music cuts out. For example, Garth Brooks sings the word “low” much deeper than the rest of the lyrics in the track “Friends in Low Places”.

What is an example of word painting?

A modern example of word painting from the late 20th century occurs in the song “Friends in Low Places” by Garth Brooks. During the chorus, Brooks sings the word “low” on a low note. Similarly, on The Who’s album Tommy, the song “Smash the Mirror” contains the line.

What is the word painting in music?

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is word painting music?

Word painting. Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What is text painting in modern music?

text painting. Text painting is a technique of music composition in which the composer deliberately illustrates aspects of the words in the text with localized aspects of the music. It is also called madrigalism (after the Renaissance madrigals who popularized it), word-painting, and less frequently as musica reservata.

An Essay on Word Painting1

Any meaningful attempt to appreciate a piece of vocal music must begin with its text, if it has one.2 Listener, analyst, critic and performer must all take the text as their starting point for the simple and obvious reason that that was where the composer almost invariably began. This dictum applies with equal force to solo and choral compositions, old music and new, nothing diminished by a few notable exceptions. It is now taken for granted that the analysis of a vocal work ought to take at least some account of the text that provided its raison d’être and generated much of the music’s structure and surface. However, such accounts are rarely more than cursory. In the subjective fog that usually obscures them, we have lost sight of some central issues. First, text-influence has never been taken seriously as one of the basic responsibilities of any genuinely complete analysis.3 Second, until we have written the history of text influences on music, we cannot write a truly comprehensive history of musical style. Moreover, we will never arrive at a genuine understanding of the vast vocal literature stretching from Josquin to Bach without a thorough grasp of one of the more important classes of text-influence: namely, word painting.

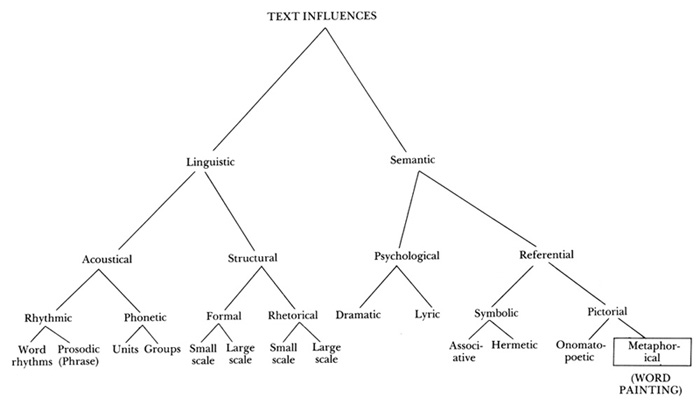

The variety of ways in which words may influence music can be formed into a surprisingly symmetrical array (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Classification of Text Influences

In this classification, word painting represents only an option of one of the eight primary surface effects (rhythmic, phonetic, formal, rhetorical, dramatic, lyrical, symbolic, pictorial). These effects rarely occur in isolation, but interact in complex and often changing relationships necessarily suppressed in the diagram. Although that regularly branching array may seem peculiarly persuasive, it does not map some inevitable fact of nature but merely one way of looking at a set of flexible compositional practices. The systematic character of the array is inherent, rather, in our habits of mind and language. For that reason, it seems reasonable to clear the air by looking at some of our assumptions.

Noise is unwanted sound—let’s get that out of the way from the start. Music is humanly organized sound, but organized with intent into a recognizable aesthetic entity. Sound consists of no more than transient disturbances of the circumambient air: rapid, minute alterations of pressure whose sum is zero and which contribute only to the entropy of the universe. From this one might easily argue that music is really nothing, leaving us to protest that some nothings are more desirable than others.

Nobody takes this sort of paradox seriously, of course; but, paradox serves rightfully as our point of departure. Notwithstanding the effort expended here to treat this subject systematically, the reader who looks for invariable principles from which to draw unassailable conclusions will find little satisfaction in what follows. Everything in music argues that such rigor is illusory, and only a musician with very limited experience would seriously pursue it. Yet, musical scholarship requires at least a degree of consistency as one of its necessary conditions. I shall attempt to reconcile that requirement with our often hopelessly paradoxical subject.

Let us pursue paradox a little further. We define word painting as the representation, through purely musical (sonorous) means, of some object, activity, or idea that lies outside the domain of music itself. But music itself (as we have «shown») is next to nothing physically; therefore, it can truly represent nothing. Music exists primarily on an aesthetic plane. It represents itself. If it communicates anything more than compulsive twitches and primal screams, it does so by some cultural agreement, by some convention less precise perhaps than that of language; but, like language, ethnocentric and ever evolving.

Language has even absorbed one musical convention so completely that we have to remind ourselves that it is purely artificial; there’s nothing in it. Speak, write, reason as we will about «high» and «low» notes in music, nothing justifies those adjectives. All notes emitted by the same source, whether high or low, issue from the same point (for all practical purposes) and radiate into the same air. They do not differ in their placements in physical space—unless we choose to quibble that the piano’s higher strings lie to the right of the lower ones. Notes have no altitude. Our stubborn belief in «high notes» and «low notes» as natural and rational expressions in the face of reality, merely emphasizes the ethnocentricity of our convention. The musicians of Classical Greece—a culture probably more obsessed with rationality than any other in recorded history—looked at things the other way around. Our «high» notes were their «low» notes; their scale ran in the opposite direction to ours.4 And with good reason unpolluted by subjective equivocation. After all, when one played the lyre, did not the string with the larger frequency (our higher note) lie closer to the ground? The modern guitarist who plays with the same configuration may well wonder if the Greeks did not have a better word for it after all.

For better or worse, our musical traditions are not those of Classical Greece, but those of the Northern barbarians. The most momentous single phenomenon in the whole history of Western Music took form, probably in the 9th century, when Frankish musical scribes began to distinguish between the sounds they were already calling «high» and «low» by some kind of vertical distinction between their alignments on the page.5 From this seed, already evident in some of the expedients of the anonymous Musica enchiriadis,6 sprang the notations of plainchant and the Ninth Symphony. And all because Charlemagne, an illiterate, wanted all his subjects to march to the same drummer (or at least the same musical liturgy). He was unable to understand why scribes could write down his words, but not the music he heard.7

The leap from Carolingian innovations to the English madrigal may seem chronologically enormous, but it’s not so great conceptually. Thus, when John Bennet, in his popular Weep, O mine eyes,8 reaches the lines, «O when, O when begin you / to swell so high that I may drown me in you?» all the parts reach their local high-point on the word «high» (their highest notes in the piece for all but the soprano), and then dip downward to the word «drown.» Bennet’s writing seems so simply and naturally expressive that no one would condemn his treatment as a mannerism or cliché. Yet this is one of two devices that come most readily to mind at the mention of the comprehensive term «madrigalism.» Throughout the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, the application of higher notes to words alluding to height or high places (sky, heaven, etc.) and lower notes to contrary meanings, became almost inescapable in mass, motet, madrigal, anthem, lute song, and opera. Almost unlimited numbers of examples testify to the prevalence of this habit which we may label the Directional Convention.

It was surely no Baroque composer who could compose the children’s round, «Row, row, row your boat gently down the stream» to an ascending melody! But, our musical instincts about what seems natural and rational suffer another blow when we look for early examples of this presumably inevitable directional convention. It seems to go back no farther than the progressive composers of the Josquin generation. In masses by earlier or more conservative composers, as often as not, ascendit meanders downward, and descendit leaps upward, while caeli et terra have their «altitudes» reversed with a regularity bordering on perversity. The word «perversity» may seem a bit harsh when we remember that the 15th century understood «high music» to mean loud, outdoor music, and «low music» to mean the softer music of the chamber. Nevertheless, the seeming indifference of such important composers as Dufay, Ockeghem, and Obrecht, to so «natural and rational» a convention brings us face to face with a serious problem in the study of word painting: How can we recognize true word painting? That is, how can we distinguish between the purposed musical realization of a text and our own fanciful reading imposed upon fortuitously conformable music? We cannot do so with complete certainty, but we must try to resolve such questions beyond a reasonable doubt, if we hope ever to write the history of one of the chief expressive and organizing features of Renaissance and Baroque style.9 Hence it seems desirable to take account of some present dangers that beset any study of word painting.

The first lies within ourselves as analysts. Even though we know better, we look for rules, laws, unbending principles in the hope that they may lead us to explanations of musical phenomena, while we tend to reject those casual rules of thumb that have the least hint of inconsistency about them. Whether or not consistent laws exist for other musical practices, they do not exist for word painting. It does not depend upon single-valued conventions for which we may compile a vocabulary of definitions. Even the most conventional gesture may have many possible interpretations, or none at all. For example, chromaticism (the other device most often associated with the term madrigalism) often expresses intensely painful emotions. Yet, no matter how widespread that use of chromaticism may have been, the various intensely chromatic keyboard pieces called Consonanze stravaganti by Giovanni de Macque,10 Gioanpietro del Buono,11 and Giovanni Maria Trabacci12 certainly intended nothing beyond the exuberance of chromatic experiment.13 Word painting, then, is not some kind of «code» that «explains» a piece of music. At best, where we happen to understand the conventions the composer has chosen to employ, it allows us a glimpse of his reading of his text—no small gain given the cultural gap that separates us from his style.

From the Romantic era we inherit yet another internal danger. The Romantics turned music into a near sacred vocation and composers into demigods who justified their elevation gloriously, whereas their musical forebears had achieved no less glory as dedicated craftsmen. The Romantics gave us the notion that only purely inspired musical creation—whatever that may be—is worthy of the admiration of the elect; that in comparison with abstractly conceived compositions, literal word painting must seem somehow inferior. Under this intimidating influence Berlioz grew ashamed of the program of his Symphonie fantastique and became the first voice of that chorus that continues to urge us to close our ears to half of its emotion. The program and the music are not incompatible; they nourish each other. Even if a Renaissance composer should have set out to «translate» his text into music, his success rested on the musical virtues of his work, not on the literalness of his translation. Literalness need not—indeed, rarely does—interfere with the musicality of the results. Just as a fine sonata must always surpass mere textbook commonplaces, a successful musical discourse must always transcend those rhetorical ingenuities which may form its substructure or animate its surface. The literalness of some of those details awakens a lurking uneasiness among some who fear it, without foundation, as a usurper of genuine musical values. Nevertheless, we who come after would be ill-advised to spurn its clues to the better understanding of a work of the past. Such scruples do not worry the world of rock, where pretentious musical illiterates peddle the «musical message» of some number according to its words, its costumes, its amps, and the staged frenzy of its performers. However remunerative such writing may be, it serves here merely to remind us that, in the search for authentic musical values, we must avoid looking for the wrong ones. We must accept word painting as a factor that contributes to musical value, but does not and cannot substitute for it.

Another caution: nothing obliges a composer to be consistent. Then as now, nothing required him to treat the same topos in the same fashion from piece to piece, or even within the same piece if it happened to recur. Still, we may not anachronistically imagine him tiring of some particular usage. («Oh, I did that once; it bores me to do it again!») The composer-craftsman of the past had a more practical respect for the techniques he had been taught or had learned for himself. We may see how he applied some of his techniques, but since we do not yet know the basis on which he chose among his options, we may actually admire his work for the wrong reasons. What we perceive as aptness, his contemporaries may have taken as conventional; where we admire inventiveness, his equally admiring colleagues may have approved his characteristic response to the implications of the text. We cannot hope to appreciate his work fully until we understand what choices he had available to him. Some decisions were made for him by the external history of the piece: the occasion, the preferences of his patron, the forces available, etc. Within these or similar constraints, he had to look at his text not very differently from the way an opera composer looks at a libretto: as a fundamental part of the composition, but always susceptible to some degree of adjustment. The composer may modify the structure of his text in several ways: he may repeat units, he may combine separate text units into a single musical unit, he may break up a unit of text into two or more musical units. As he proceeds, he must decide at every point which particular combination of voices he will assign to each word and phrase of text, with what degree of prominence and emphasis, what texture, what balance, and what particular combination of musical techniques—of which word painting is but one. Melody, rhythm, and harmony, the surface features of the music, must emerge out of this complex background of pre-conditions—or perhaps better: co-existent ideas—often rendered more complicated by the pre-existent materials of cantus firmus, paraphrase, or parody. Word-painting is one of the prominent text-music relationships that we may reasonably expect to help us make sense out of that welter of pre-conditions.

The foregoing remarks imply yet another caution: even in the work of the most doctrinaire madrigalist, word painting is not omnipresent. The presence of a text invites a composer to respond to it, but the composer—whether Ockeghem or Stravinsky—may choose to ignore it. We need to know what elements in a text induce a composer to bend his music to it, but we need to know, also, the nature of the musical situations that lead him to overrule the appeal of the text. Such matters will require years of attention from many scholars.14

The context in which we find a device of word painting raises another question. In a text that presents the words «high» and «low,» we would ordinarily expect to hear them sung on relatively higher and lower notes respectively. This usually happens in the normal conduct of word painting, but not always. Let us construct a hypothetical example using the text, «he ran about looking high, and ran about looking low,» sung all on one repeated note, except for the word «looking,» which sounds a third higher than the repeated note in the first half of the line, and a fourth lower than the repeated note at its second occurrence. If the style of the rest of the piece did not contradict us, we would deduce (probably correctly) that the composer had a textual motivation for the shape of his line. The proximity of the upward and downward leaps to words of parallel imagery seems to associate them with those meanings. But what happens if we increase the distance by placing the leaps on «ran» instead of «looking»? Or, pushing the matter further, suppose each half of the line were set to but a single note, the first a fifth higher than the second? a third higher? a step higher? We may find no difficulty in recognizing pictorial intent in every one of these examples, depending on the context in which we find them. This high-low prejudice eventually becomes so strong that, even where a composer avoids word painting in order to shift emphasis to another point in the text, I believe we may often detect a reluctance to set words like caeli et terra in reversed positions. Terra may occur only a step lower, or even on the same step, but only rarely higher than caeli.

Let us form another artificial example out of the text, «I climb to heaven, only to fall to earth»—a routine job for the practiced word-painter. He would probably look for appropriate melodies rising on «climb» to peak at «heaven,» and descending on «fall» to reach a low-point on «earth.» But suppose the line had read: «to heaven I climb, to earth I fall»? An attempt to parallel the meanings of the four key words, although not impossible, could lead the composer into awkward constructions. Faced with such a problem, the composer could set this new version of our text to the same sort of music as our first version, even though that would mean leaving «heaven» at the lower end of his upward run, and «earth» at the upper end of his downward run. Here again, the context allows reason enough to read pictorial intent in the passage: upward motion still decorates the upward image, downward motion sets the downward image, and the local discrepancies in the positions of «heaven» and «earth» lose their importance to the larger context. Obviously, one might push such interpretations beyond reasonable bounds; for example, when Ockeghem sets each noun of caeli et terra with both upward and downward motions (as in the Sanctus of his Missa Mi-mi),15 we have no right to label the conformable motions as pictorial and simply dismiss the inconvenient ones. Moreover, Ockeghem’s masses taken together do not offer consistent evidence of pictorial concern. Even allowing for the uncertainties in the underlay of the sources, a preponderance of evidence argues against pictorial interpretation.

As one last example of the role of context, let us imagine a poem of unrequited love which places the word «pain» at a verbally significant position. Suppose that position does not suit the composer musically (for whatever reason), and he decides not to apply the usual chromatic motion (or chromatic harmony) directly on the painful word. If he places the chromaticism somewhere in the same musical phrase, we may readily understand it (just as in our preceding example, regardless of what words it sets) as conventional word painting. But, let us suppose he chooses to distribute chromaticism liberally everywhere throughout the piece, but not in the key phrase. Could he possibly have intended the omission as a kind of noema, emphasizing the idea by understatement? But what of all the other chromaticisms in the piece? Do we take them as word painting in the narrow sense, as symbols of pain applied locally, or as a response to the prevailing idea of the pain of unrequited love? It takes a thoughtful reading of both poem and music if one hopes to arrive at a responsible opinion of such treatments. Since word painting can function at many levels,16 an analysis must account for all of them. It is quite possible to miss the forest for the trees; to pass over larger pictorial implications while successfully cataloguing all the local devices.

Underlay presents us with another danger. The sources that preserve older music usually fail to align the syllables of a text with their proper notes, leaving us to guess, most of the time, at what the composer may have intended. We must review all underlay critically, because whether analyzing a composition or making any judgment at all about its word painting, we do so on the assumption that the words and the music that symbolizes them are in proper alignment. As every transcriber of early music knows (or ought to know), underlay is largely an analytical problem. The theorists tell us less than we need to know, while the sources often disagree with them and with each other. This observation takes nothing away from the authority of either the theorists or sources, but it reminds us that we need all the help we can get. We have every reason to suppose that a better understanding of word painting practices would offer some help. If we knew more about the conventions appropriate to the style of the piece being transcribed, we could recognize certain fixed points in the text as sites to which a composer might apply one of the appropriate devices. If one of the common devices of that style should happen to stand not far from appropriate words, we might have reason to underlay it with them—thus reducing the areas of uncertain text placement to the distance from one fixed point to the next. Small help, perhaps, but not to be disdained.

The question of underlay raises yet another hobgoblin: the question of contrafactum which can afflict both plainsong and polyphony. The Renaissance and Baroque habit of substituting a new text for the original one in an already completed composition (in order to make it suitable for another occasion) can make a mockery of a word painting study. However, the case is not so clear-cut. Since the counterfeiter knew the conventions of his time better than we do, he could well have chosen the piece or adjusted the text in such a way as to preserve some word painting of the original—or even to make some appear where the original had none at all. Some of Bach’s adaptations of earlier cantatas seem to hold out this possibility. After the English Reformation, some formerly Latin motets acquired amazingly felicitous English texts. Strophic compositions, too, are a kind of contrafactum; in the absence of other evidence, we usually assume that the composer set only the first stanza; that assumption remains untested. Whatever the problem, the validity of our judgments about a text-music relationship hinges—as does every other kind of analysis—on our having the authentic text before us.

The perils arising from such pitfalls lead many to mistrust the subjective element that must affect this sort of study for a long time to come. However, whether in our hypotheses or in our practice, the judicious exercise of subjectivity cannot be avoided in any kind of musical analysis. It becomes abhorrent only when it masquerades as objective science.

| * | * | * | * | * | * |

What creative value can word painting possibly have had in the process of composition? Its meaning for us depends on that. It must have had considerable value for so many composers of demonstrable genius to have employed it for so many generations. To make the issues a little clearer, let us leave aside the more glamorous or dramatic applications of it in motet and madrigal, and consider a lesson we may draw from the repertory of masses.

A composer would have been likely to set the words of the Ordinary of the Mass many times in the course of his career, and the works of, say a Josquin or a Palestrina, give us reason to believe that a dedicated craftsman would always seek fresh and interesting ways to fulfill that recurrent commission—but within the vocabulary of received contemporary practices. The structure of the Mass text formed a natural basis for the structure of his music, and the conventions that might apply to each segment of text provided him, at each moment, with a set of possibilities which always included the possibility of evading the conventions. Like the sets of standard cadences and the rules of counterpoint, word painting was but one of the options conventionally available to him. If he declined them all—that is, if he embarked upon a path of «free» composition—he followed a most uncommon practice. Composition was rarely completely free in any of the arts. Most often, it made use of pre-existent models or materials in one form or another. A composition formed upon no prior melody or polyphony, and which also disregarded all conventional rhetoric would have been rare indeed. Such compositions usually spring from some constructivist principle, from canon, soggetto cavato dalle vocali, and the like. The idea of total freedom had little aesthetic meaning for a composer. It had no basis in his training or his social outlook before Romanticism reshaped the creative world. Therefore, when we find ourselves tempted to call a passage or a composition «free,» it may mean only that we don’t know what the composer is doing.

When a composer writing a mass chose some of the possibilities available to him and rejected others, he created emphasis by both his choices and his omissions from the vocabulary of standard conventions. In effect he gave his discourse an individual stamp that had meaning for his contemporaries. Today, many listeners find one 16th-century mass much like another except that the tunes of one may please them more than another. That attitude would have seemed naive in the 16th century, when paraphrase and parody techniques generated whole tangles of masses based on the same tunes. The 16th-century connoisseur undoubtedly enjoyed the tunes in such masses as well as we do, but he gave his critical attention to the fertility of imagination with which the composer renewed and invigorated the given materials, musical and textual. Just as the pre-existent musical materials could be re-worked with endless variety, so could the text of the Mass. A mass was a mass; what mattered was how a composer said his Mass (or motet, or madrigal, etc.). For us to ignore this challenge of musical aesthetics, to ignore the way a composer said his text, is as willfully ignorant and as marginally musical as listening to Schubert Lieder or Verdi operas simply to enjoy the tunes—or worse, just the voices. The fact that unlettered listeners with just such tastes make up the preponderant majority of the musical public does not discredit the assertion. If anything, it bolsters it. To take any other view would be tantamount to redefining the brilliant musical creations of our heritage according to the irresponsible whims of our own age. Of course, we cannot help being of our own time and society. But, if the art of the past has any message worth receiving, it must speak to us in its own voice, not ours. Great works of art do not reach us through movie versions of Moby Dick and Tom Jones or rock versions of the Pirates of Penzance and the Bible. Those are the voices of our culturally anaesthetized kinfolk speaking and listening only to themselves. Let us count our blessings.

Dedicated musicians and musical scholars know that we can never completely recover the past. That is not our goal, nor should it be. Our aim is to communicate with the past as well as we can in order to derive profit from its musical treasures so different from our own—riches we can only simulate. Therefore, since the composers of the past bent themselves to the task of discoursing upon a text to the best of their abilities, we must take pains to understand their responses to that text if we would truly hear their music.*

1The substance of this essay is drawn from the author’s book in progress, Music and Words: A Systematic Examination of Madrigalism and Other Text-Influences on Music. It will provide tools for the solution of a number of the problems raised below.

2For some songs truly without words see Owen Jander, «Vocalise» in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie (London, 1980), 20, p. 51, to which we may add: Stravinsky’s Pastorale (1907), and Henry Cowell’s Vocalise (1937) and Toccanta (1938).

3As far as I know, the first comprehensive analytical program to allow text-influence a significant role in its scheme is Jan LaRue’s Guidelines for Style Analysis (New York: Norton, 1970). LaRue makes a good beginning, although he is concerned chiefly with instrumental music.

4See almost any standard text book. To cite but one: Donald Jay Grout, A History of Western Music, 3rd edition (New York: Norton, 1980), pp. 28 ff.

5For an investigation of the early history of this phenomenon, see: Leo Treitler, «The Early History of Music Writing in the West,» Journal of the American Musicological Society, XXXV (1982), 237-279.

6Diplomatic facsimiles of these expedients are conveniently available in the translation of Léonie Rosenstiel, Colorado College Music Press Translations, 7, Albert Seay, ed. (Colorado Springs, 1974), pp. 6 ff, et passim.

7For an account of Charlemagne’s role in this development, see: Leo Treitler, «Homer and Gregory: The Transmission of Epic Poetry and Plainchant,» The Musical Quarterly, LX (1974), 338 ff.

8Edmund H. Fellowes, The English Madrigal School, XXIII: John Bennet, Madrigals to Four Voices (1599) (London, 1922), pp. 60-62.

9See note 1.

10For a brief example see Willi Apel, The History of Keyboard Music to 1700 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1972), pp. 425.

11For a brief example see Willi Apel, op. cit., p. 493.

12Luigi Torchi, L’arte musicale in Italia, III, p. 372, and also Roland Jackson, «On Frescobaldi’s Chromaticism and Its Background,» The Musical Quarterly, LVII (1971), 257.

13Although these are keyboard rather than vocal works the argument still holds, for there are many instrumental works with comparable text associations that cannot be challenged; see note 1.

14See note 1.

15Johannes Ockeghem: Collected Works, ed. Dragan Plamenac, 2nd edition (New York, 1966), II, p. 15, mm. 29-38.

16A preliminary version of this idea (refined in the book in progress) appeared in my dissertation: Guillaume Costeley (1531-1606): Life and Works (New York University, 1969), pp.178-185.

*Special thanks are herewith offered to Martin Bernstein, who in many ways influenced the preparation of this study. Celebremus: 1984. xii. 14.