Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Mr. Clemens Kub

Score: 5/5

(64 votes)

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is characteristics of use of word painting?

Word painting is a compositional style of setting the melody so it vividly depicts the imagery, and actions taking place in the music. For instance words with a negative connotation such as descending, death, ground,etc. will have a melody with a downward movement of pitch.

What is the use of word painting?

Musical depiction of words in text. Using the device of word painting, the music tries to imitate the emotion, action, or natural sounds as described in the text. For example, if the text describes a sad event, the music might be in a minor key.

What is word painting in literature?

n. 1. The technique of using the phonic qualities of words to suggest or reinforce their meaning, especially in poetry.

Which genre uses word painting?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

35 related questions found

How do you describe the word painting in music?

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is the definition of word painting in music?

Word painting is when the melody of a song actually reflects the meaning of the words. The best way to learn about it is to listen.

Which of the following would be the best definition of word painting?

Word painting is when the music describes the action. … An example of word painting would be when someone is going down a hill, the music descends as well.

What is the difference between word painting and declamation?

How a text is set to music is called its declamation. Recitative and word painting are two types of musical declamation: recitative is a speech-like, declamatory singing style that emphasizes the important syllables and words of the text, while word painting is a musical illustration of a word being sung.

What is word painting give a brief example?

Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa. For example, singing the word “stop” as the music cuts out. Depending on which you write first (music or lyrics) it can be carried out in any order.

What is word painting MUS 121?

What is word painting? A musical concept in which melodies depict specific words that are sung (like notes going higher in pitch on the word «ascend»).

How do you describe the texture of a song?

Texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices.

What is the definition of word painting quizlet?

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of writing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

How did Renaissance composers use word painting in their music?

Word painting was utilized by Renaissance composers to represent poetic images musically. For example, an ascending me- lodic line would portray the text “ascension to heaven.” Or a series of rapid notes would represent running.

How is word painting used in as Vesta was descending?

“Vest” from vesta is the strong pulse. “From Latmos Hill” is always a three-note ascending motif in imitative counterpoint to illustrate a hill, and then when the voices sing “descending,” the scale reverses and descends. This is the first demonstration of word painting in this composition.

What is the tone of a painting?

In painting, tone refers to the relative lightness or darkness of a colour (see also chiaroscuro). One colour can have an almost infinite number of different tones. Tone can also mean the colour itself.

What is abstract art with words?

Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect. Wassily Kandinsky. Cossacks 1910–1. Tate. Strictly speaking, the word abstract means to separate or withdraw something from something else.

What is the definition of a chanson?

: song specifically : a music-hall or cabaret song.

Where did the word painting come from?

1300, «decorate (something or someone) with drawings or pictures;» early 14c., «put color or stain on the surface of; coat or cover with a color or colors;» from Old French peintier «to paint,» from peint, past participle of peindre «to paint,» from Latin pingere «to paint, represent in a picture, stain; embroider, …

Which is true of an aria?

What is true of recitatives? An aria is: … and extended piece for a solo singer having more musical elaboration and a steadier pulse than recitative.

Which of the following are known Madrigalists?

Some of the best known of the English madrigalists include Thomas Morley (1558-1602), Francis Pilkington (ca. 1570-1638), William Byrd (1543-1623), Orlando Gibbons(1583-1625), and Thomas Weelkes (1576-1623).

Which composer used word painting which used music to reflect the literal meaning of the words?

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Handel’s music is the use of “word-painting,” the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What is the texture of Renaissance?

The texture of Renaissance music is that of a polyphonic style of blending vocal and instrumental music for a unified effect.

What is a melismatic melody?

Melisma (Greek: μέλισμα, melisma, song, air, melody; from μέλος, melos, song, melody, plural: melismata) is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. … An informal term for melisma is a vocal run.

Для картин и других произведений искусства, включающих текст, см. Word art .

Рисование слов , также известное как рисование тонов или рисование текста , — это музыкальная техника сочинения музыки, которая отражает буквальное значение текста песни или элементов истории в программной музыке .

Историческое развитие

Тональная окраска слов восходит как минимум к григорианскому пению . Музыкальные образцы выражали в этих песнопениях как эмоциональные идеи, так и богословские значения. Например, образец фа-ми-соль-ла означает унижение и смерть Христа и Его воскресение во славе. Фа-ми означает осуждение, в то время как соль — это нота воскресения, а ла — выше воскресения, Его небесной славы (« суррексит Иисус »). Такие музыкальные слова помещаются в слова из библейского латинского текста; например, когда fa-mi-sol-la помещается в » et libera » (например, вступление к воскресенью Sexagesima ) в христианской вере, это означает, что Христос освобождает нас от греха через Свою смерть и воскресение.

Словесная живопись развивалась особенно в конце 16 века среди итальянских и английских композиторов мадригалов , до такой степени, что средства рисования слов стали называть мадригализмами . Хотя он зародился в светской музыке, он нашел свое отражение и в другой вокальной музыке того времени. Хотя эта маньеризм стала характерной чертой мадригалов конца XVI века, в том числе итальянских и английских, она встретила резкую критику со стороны некоторых композиторов. Томас Кэмпион , писавший в предисловии к своей первой книге лютневых песен в 1601 году, сказал об этом: «… там, где природа слова everie точно выражена в примечании… такое детское наблюдение слов совершенно нелепо».

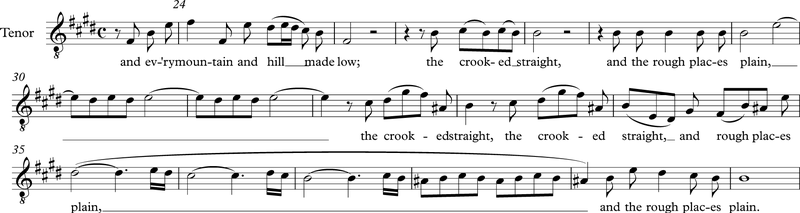

Живопись слова процветала в период музыки барокко . Один хорошо известный пример встречается в Handel «s Мессии , где тенор арию содержит настройки Генделя текста:

- Каждая долина возвысится, и все горы и холмы сделаются низкими; кривые прямые, а неровные места равнины. ( Исайя 40: 4)

В мелодии Генделя слово «долина» оканчивается на низкой ноте, «возвышенный» — восходящая фигура; «гора» образует вершину мелодии, «холм» — меньшую, а «низкая» — еще одна низкая нота. «Crooked» поется для быстрой фигуры из четырех разных нот, в то время как «Straight» поется на одной ноте, а в «грубых местах» «грубые места» поются на коротких отдельных нотах, тогда как последнее слово «plain» охватывает несколько тактов в серии длинных нот. Это можно увидеть в следующем примере:

В популярной музыке

В современной музыке есть несколько примеров словесной живописи конца 20 века.

Один из примеров встречается в песне « Friends in Low Places » Гарта Брукса . Во время припева Брукс поет слово «низкий» на низкой ноте. Точно так же в альбоме Tommy The Who песня «Smash the Mirror» содержит строчку «Rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, up, и во взлет,, и в росте, и в восходе, и в восходе …». «Каждое повторение« подъема »на полтона выше предыдущего, что делает это особенно ярким примером рисования слов.

« Аллилуйя » Леонарда Коэна включает еще один пример рисования слов. В строке «Это идет так: четвертое, пятое, незначительное падение и основной подъем, сбитый с толку король, сочиняющий аллилуйя», текст обозначает последовательность аккордов в песне.

Песня Джастина Тимберлейка «What Goes Around» — еще один популярный пример рисования текста. Слова песни

- Что происходит, идет, идет кругом

- Полностью возвращается

спуститесь на октаву, а затем вернитесь в верхнюю октаву, как если бы она двигалась по кругу.

В припеве песни » Up Where We Belong «, записанной Джо Кокером и Дженнифер Уорнс , мелодия повышается во время слов «Любовь поднимает нас».

В « Огненном кольце » Джонни Кэша есть картина перевернутого слова, где «вниз, вниз, вниз» поется на восходящие ноты, а «выше» поется с опусканием с более высокой ноты на более низкую.

В версии Джима Ривза песни Джо Эллисона и Одри Эллисон » He’ll Have to Go » голос певца падает на последнем слове строки: «Я скажу человеку, чтобы он повернул музыкальный автомат как можно ниже. . »

Когда Уоррен Зевон поет «Я думаю, что опускаюсь вниз» в своей песне « Кармелита », его голос падает на слово «вниз».

В «Моем романе» Ричарда Роджерса и Лоренца Харта мелодия перескакивает на более высокую ноту на слове «восходящий» в строке «Моему роману не нужен возвышающийся замок в Испании».

В записях песни Джорджа и Иры Гершвин «They Can’t Take That Away from Me» Элла Фицджеральд и другие намеренно поют неправильную ноту на слове «ключ» во фразе «то, как вы поете не по тональности».

Другое обратное происходит во время песни « A Spoonful of Sugar » от Мэри Поппинс , поскольку во время строки «Просто ложка сахара помогает лекарству опуститься», слова «go down» переходят с более низкой ноты на более высокую.

В начале первого припева в « Despacito » Луиса Фонси музыка замедляется, когда исполняется слово «despacito» (медленно).

В песне Secret Garden » You Raise Me Up » слова «you Raise me up» поются с возрастающей гаммой в начале припева.

Queen используют рисование слов во многих своих песнях (в частности, в песнях, написанных вокалистом Фредди Меркьюри ). В « Somebody to Love » каждый раз, когда встречается слово «Господь», оно поется как самая высокая нота в конце восходящего отрывка. В той же пьесе текст «У меня нет ритма; я просто теряю свой ритм» ложится на удары, чтобы создать впечатление, что он вне времени.

Queen также используют раскрашивание слов с помощью технологии записи музыки в своей песне » Killer Queen «, где во время слова «laser-beam» в 17-м такте на вокал добавлен эффект флэнжера .

Смотрите также

- Микки Маузинг

- Musica Reservata

- Программная музыка

- Глаз музыка

использованная литература

Источники

- М. Клемент Морин и Роберт М. Фауэллс, «Григорианские музыкальные слова», в хоровых эссе: дань уважения Роджеру Вагнеру , под редакцией Уильямса Уэллса Белана, Сан-Карлос (Калифорния): Thomas House Publications, 1993

- Сэди, Стэнли. Word Painting . Картер, Тим. Словарь музыки и музыкантов New Grove. Издание второе, т. 27.

- Как слушать и понимать отличную музыку, часть 1, диск 6, Роберт Гринберг, Музыкальная консерватория Сан-Франциско

John Ruskin’s term for the linguistic counterpart to drawing, word-painting allows viewers to capture the psychological impact that a beautiful scene or object has on them and hopefully notice the aesthetic reasons they find it beautiful. Word-painting stands opposed to dry, everyday forms of description that fail to capture the experience of encountering something beautiful: for example, whereas many British people (to Ruskin’s frustration) simply call the weather “wet and windy,” Ruskin finds this shallow description frustrating, and instead word-paints the weather with descriptions like “dawn purple, flushed, delicate. Bank of grey cloud, heavy at six. Then the lighted purple cloud showing through it, open sky of dull yellow above—all grey, and darker scud going across it obliquely, from the south-west—moving fast, yet never stirring from its place, at last melting away.”

Word-Painting Term Timeline in The Art of Travel

The timeline below shows where the term Word-Painting appears in The Art of Travel. The colored dots and icons indicate which themes are associated with that appearance.

Ruskin wanted people to not only draw but also “word-paint.” De Botton notes that people often lack the language to describe beautiful places, but Ruskin…

(full context)

Ruskin’s word-paintings were about places’ psychological effects as much as their aesthetic qualities. He personified clouds, seeing…

(full context)

De Botton then felt a desire to possess the buildings’ beauty, and he began word-painting them in psychological terms. During the day, they were normal, he felt, but at night…

(full context)

De Botton concludes that, despite his word-paintings’ middling quality, he nevertheless pursued Ruskin’s two goals for art: “to make sense of pain…

(full context)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For paintings and other art incorporating text, see Word art.

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

Historical development[edit]

Tone painting of words goes at least as far back as Gregorian chant. Musical patterns expressed both emotive ideas and theological meanings in these chants. For instance, the pattern fa-mi-sol-la signifies the humiliation and death of Christ and his resurrection into glory. Fa-mi signifies deprecation, while sol is the note of the resurrection, and la is above the resurrection, His heavenly glory («surrexit Jesus«). Such musical words are placed on words from the Biblical Latin text; for instance when fa-mi-sol-la is placed on «et libera» (e.g., introit for Sexagesima Sunday) in the Christian faith it signifies that Christ liberates us from sin through his death and resurrection.[1]

Word painting developed especially in the late 16th century among Italian and English composers of madrigals, to such an extent that word painting devices came to be called madrigalisms. While it originated in secular music, it made its way into other vocal music of the period. While this mannerism became a prominent feature of madrigals of the late 16th century, including both Italian and English, it encountered sharp criticism from some composers. Thomas Campion, writing in the preface to his first book of lute songs in 1601, said of it: «… where the nature of everie word is precisely expresst in the Note … such childish observing of words is altogether ridiculous.»[2]

Word painting flourished well into the Baroque music period. One well-known example occurs in Handel’s Messiah, where a tenor aria contains Handel’s setting of the text:[3]

- Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill made low; the crooked straight, and the rough places plain. (Isaiah 40:4)[4]

In Handel’s melody, the word «valley» ends on a low note, «exalted» is a rising figure; «mountain» forms a peak in the melody, and «hill» a smaller one, while «low» is another low note. «Crooked» is sung to a rapid figure of four different notes, while «straight» is sung on a single note, and in «the rough places plain», «the rough places» is sung over short, separate notes whereas the final word «plain» is extended over several measures in a series of long notes. This can be seen in the following example:[5]

In popular music[edit]

There are countless examples of word painting in 20th century music.

One example occurs in the song «Friends in Low Places» by Garth Brooks. During the chorus, Brooks sings the word «low» on a low note.[6] Similarly, on The Who’s album Tommy, the song «Smash the Mirror» contains the line «Rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise….» Each repetition of «rise» is a semitone higher than the last, making this an especially overt example of word-painting.[7]

«Hallelujah» by Leonard Cohen includes another example of word painting. In the line «It goes like this the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift, the baffled king composing hallelujah,» the lyrics signify the song’s chord progression.[8]

Justin Timberlake’s song «What Goes Around» is another popular example of text painting. The lyrics

- What goes around, goes around, goes around

- Comes all the way back around

descend an octave and then return to the upper octave, as though it was going around in a circle.

In the chorus of «Up Where We Belong» recorded by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes, the melody rises during the words «Love lift us up».

In Johnny Cash’s «Ring of Fire», there is an inverse word painting where «down, down, down» is sung to the notes rising, and ‘higher’ is sung dropping from a higher to a lower note.

In Jim Reeves’s version of the Joe Allison and Audrey Allison song «He’ll Have to Go,» the singer’s voice sinks on the last word of the line, «I’ll tell the man to turn the juke box way down low.»

When Warren Zevon sings «I think I’m sinking down,» on his song «Carmelita,» his voice sinks on the word «down.»

In Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s «My Romance,» the melody jumps to a higher note on the word «rising» in the line «My romance doesn’t need a castle rising in Spain.»

In recordings of George and Ira Gershwin’s «They Can’t Take That Away from Me,» Ella Fitzgerald and others intentionally sing the wrong note on the word «key» in the phrase «the way you sing off-key».[9]

Another inverse happens during the song «A Spoonful of Sugar» from Mary Poppins, as, during the line «Just a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down,» the words «go down» leap from a lower to a higher note.

In Follies, Stephen Sondheim’s first time composing the words and music together, the number «Who’s That Woman?» contains the line «Who’s been riding for a fall?» followed by a downward glissando and bass bump, and then the line «Who is she who plays the clown?» followed by mocking saxophone wobbles.

At the beginning of the first chorus in Luis Fonsi’s «Despacito», the music is slowed down when the word «despacito'»(slowly) is performed.

In Secret Garden’s «You Raise Me Up», the words «you raise me up» are sung in a rising scale at the beginning of the chorus.

Queen use word painting in many of their songs (in particular, those written by lead singer Freddie Mercury). In «Somebody to Love», each time the word «Lord» occurs, it is sung as the highest note at the end of an ascending passage. In the same piece, the lyrics «I’ve got no rhythm; I just keep losing my beat» fall on off beats to create the impression that he is out of time.

Queen also uses word painting through music recording technology in their song «Killer Queen» where a flanger effect is placed on the vocals during the word «laser-beam» in bar 17.[10]

In Mariah Carey’s 1991 single Emotions word painting is used throughout the song. The first use of word painting is in the lyric «deeper than I’ve ever dreamed of» where she sings down to the bottom of the staff, another example is also in the lyric «You make me feel so high» with the word «high» being sung with arpeggios with the last note being an E7

In Miley Cyrus’ ‘Wrecking Ball’, every time the title of the song is mentioned, all instruments engage in one huge wall of sound, therefore mimicking the sound of a wrecking ball whenever the chorus comes in.

Burt Bacharach uses word-painting in the song ‘In Between the Heartaches’ from Dionne Warwick’s Here_I_Am album. The song opens on an A-flat minor 11th chord. Dionne sings on the 11th of the chord (on the words…’In Between…’); a high E-flat briefly (on the word ‘the’); and back to the 11th and the 9th of the chord (on the word…’Heartaches…’) Those notes fall IN BETWEEN the notes of an A-flat minor triad (A-flat, C-flat, E-flat) making it a highly sophisticated example of word-painting.

See also[edit]

- Mickey Mousing

- Musica reservata

- Program music

- Eye music

References[edit]

- ^ Krasnicki, Ted. «The Introit For Sexagesima Sunday». New Liturgical Movement.

- ^ Thomas Campion, First Booke of Ayres (1601), quoted in von Fischer, Grove online

- ^ Jennens, Charles, ed. (1749). Messiah – via Wikisource.

- ^ «Isaiah#Chapter 40» . Bible (King James). 1769 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Bisson, Noël; Kidger, David. «Messiah: Listening Guide for Part I». First Nights (Literature & Arts B-51, Fall 2006, Harvard University). The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ «Word painting in songwriting…» The Song Writing Desk. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Ellul, Matthew. «How to Write Music». School of Composition. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Ellul, Matthew. «How to Write Music». School of Composition. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ «A LEVEL Performance Studies: George Gershwin» (PDF). Oxford Cambridge and RSA (Version 1): 16. September 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ «Queen: ‘Killer Queen’ from the album Sheer Heart Attack» (PDF). Pearson Schools and FE Colleges. Area of study 2: Vocal Music: 97. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

Sources[edit]

- M. Clement Morin and Robert M. Fowells, «Gregorian Musical Words», in Choral essays: A Tribute to Roger Wagner, edited by Williams Wells Belan, San Carlos (CA): Thomas House Publications, 1993

- Sadie, Stanley. Word Painting. Carter, Tim. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Second edition, vol. 27.

- How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, Part 1, Disc 6, Robert Greenberg, San Francisco Conservatory of Music

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of having the music mimic the literal meaning of a song. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

Tone painting of words goes at least as far back as Gregorian chant. Little musical patterns are musical words that express not only emotive ideas such as joy but theological meanings as well in the Gregorian. For instance, the pattern FA-MI-SOL-LA signifies the humiliation and death of Christ and His resurrection into glory. FA-MI signifies deprecation, while SOL is the note of the resurrection, and LA is above the resurrection, His heavenly glory («surrexit Jesus»). Such musical words are placed on words from the Biblical Latin text; for instance when FA-MI-SOL-LA is placed on «et libera» (e.g. introit for Sexagesima Sunday) it signifies that Christ liberates us from sin through His death and resurrection.

Composers also experimented with word painting in Italian madrigals of the 16th and 17th centuries. Word painting flourished well into the Baroque music period. One well known example occurs in Handel’s «Messiah», where a tenor aria contains Handel’s setting of the text:

:»Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill made low; the crooked straight, and the rough places plain.» (Isaiah 40:4)

In Handel’s melody, the word «valley» ends on a low note, «exalted» is a rising figure; «mountain» forms a peak in the melody, and «hill» a smaller one, while «low» is another low note. «Crooked» is sung to a rapid figure of four different notes, while «straight» is sung on a single note, and in «the rough places plain,» «the rough places» is sung over short, separate notes whereas the final word «plain» is extended over several measures in a series of long notes. This can be seen in the following example:

A modern example of word painting from the late 20th century occurs in the song «Friends in Low Places» by Garth Brooks. During the chorus, Brooks sings the word «low» on a low note. Similarly, on The Who’s album «Tommy», the song «Smash the Mirror» contains the line

:»Can you hear me? Or do I surmise»:»That you feel me? Can you feel my temper»:«Rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise….«

Each repetition of ‘rise’ is a half-step higher than the last, making this a clear example of word-painting.

Justin Timberlake’s song «What goes around» is another popular example of text painting. The lyrics

:»What goes around, goes around, goes around»:»Comes all the way back around»

descend an octave and then return back to the upper octave.

In the chorus of Up Where We Belong, the melody rises during the words «Love lift us up where we belong.»

On occasion, a composer may employ the opposite technique for a humorous effect. In the Broadway musical Once Upon a Mattress, Mary Rodgers has the lead character, Princess Winnifred, belt a brash show tune about her shyness called «Shy».

ources

*M. Clement Morin and Robert M. Fowells, «Gregorian Musical Words», in «Choral essays: A Tribute to Roger Wagner», edited by Williams Wells Belan, San Carlos (CA): Thomas House Publications, 1993

* Sadie, Stanley. «Word Painting». Carter, Tim. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Second edition, vol. 27.

* How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, Part 1, Disc 6, Robert Greenberg, San Francisco Conservatory of Music

ee also

* mickey mousing

* Musica Reservata

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

This guest post is by Elise Abram. Elise is a published author, English teacher, and former archaeologist. You can follow her blog, My Own Little Storybrooke, about the writing process and pop culture’s ties to literature. Elise is the author of Phase Shift, and is currently finishing her second novel, The Revenant.

A few years ago I taught at a high school with a strong Arts program. At the end of the school year, the fruits of students’ labour were put up for sale in a silent auction. I remember walking through the room, mouth agape and eyes bulging in awe of the talent I saw.

Later in the staff room a colleague and I, both of us English teachers, both aspiring authors, were fawning over the accomplishments of our students and I remember saying, “I wish I had talent like that.” My colleague assured me that I did. When I protested that I couldn’t even draw a wiggly line, she said to me, “You’re an artist; you paint word pictures.”

It was a moment of epiphany, one that’s stayed with me to this day.

Photo by Paul Bica

Writing Lessons from The Beatles

As writers, we draw worlds and paint scenes with our words. It is our job to carefully select the exact words that help our readers see, hear and feel what our characters see, hear and feel as our stories unfold.

I picked the first line of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” as the title of this post because it demonstrates the creativity writers must employ during the writing process. Lennon and McCartney could have said “Picture yourself in a boat on a river in autumn at sunset,” but they didn’t.

Instead, they imagined orange leaves hanging from the trees, curling over and back on themselves as they dry in the sun until they look like tangerines ripe for the picking, and a sunset with shades of yellow and orange, sky cloudy and viscous as marmalade.

The words paint a peaceful scene, what with the calmness of the river, the sweetness of the marmalade and the tangerines, juicy and full of promise. The song is not known for its run-of-the-mill lyrics, but for the words behind the iconic imagery it evokes

How to Paint Word Pictures

The next time you describe a person, place or thing, use words as your brushes.

Be conscious of when to paint in broad strokes (as in “a boat on a river”) and when to switch to a thinner brush (think “tangerine dreams” and “marmalade skies”). Rather than use commonplace colors, think in terms of paint colour palates (How many shades of white paint are available at your local hardware store?).

Appeal to the senses. Make your reader smell, see, hear, feel and taste what you imagine.

Do you try to paint word pictures when you write?

PRACTICE

Place yourself in a scene. You could be on the riverboat with Lennon and McCartney, in a place that evokes the essence of your own inner peace, or right where you’re sitting as you read this post.

Now paint a word picture. Feel free to be true to life or embellish. Appeal to as many senses as you can. What do you smell, see, hear, feel, or taste? Your goal is to paint a picture with your words vivid enough for your reader to imagine sitting right next to you in the scene.

Write for fifteen minutes. When you’re time is up, post your scene in the comments so we can travel down the river with you.

Remember: you are the artist, and your words, your paint and brushes.

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris, a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

An Essay on Word Painting1

Any meaningful attempt to appreciate a piece of vocal music must begin with its text, if it has one.2 Listener, analyst, critic and performer must all take the text as their starting point for the simple and obvious reason that that was where the composer almost invariably began. This dictum applies with equal force to solo and choral compositions, old music and new, nothing diminished by a few notable exceptions. It is now taken for granted that the analysis of a vocal work ought to take at least some account of the text that provided its raison d’être and generated much of the music’s structure and surface. However, such accounts are rarely more than cursory. In the subjective fog that usually obscures them, we have lost sight of some central issues. First, text-influence has never been taken seriously as one of the basic responsibilities of any genuinely complete analysis.3 Second, until we have written the history of text influences on music, we cannot write a truly comprehensive history of musical style. Moreover, we will never arrive at a genuine understanding of the vast vocal literature stretching from Josquin to Bach without a thorough grasp of one of the more important classes of text-influence: namely, word painting.

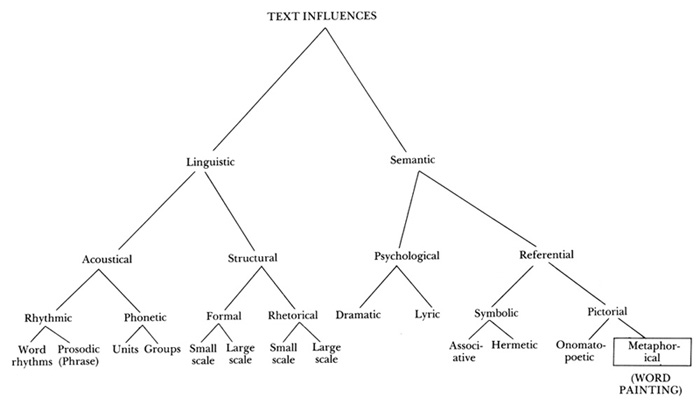

The variety of ways in which words may influence music can be formed into a surprisingly symmetrical array (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Classification of Text Influences

In this classification, word painting represents only an option of one of the eight primary surface effects (rhythmic, phonetic, formal, rhetorical, dramatic, lyrical, symbolic, pictorial). These effects rarely occur in isolation, but interact in complex and often changing relationships necessarily suppressed in the diagram. Although that regularly branching array may seem peculiarly persuasive, it does not map some inevitable fact of nature but merely one way of looking at a set of flexible compositional practices. The systematic character of the array is inherent, rather, in our habits of mind and language. For that reason, it seems reasonable to clear the air by looking at some of our assumptions.

Noise is unwanted sound—let’s get that out of the way from the start. Music is humanly organized sound, but organized with intent into a recognizable aesthetic entity. Sound consists of no more than transient disturbances of the circumambient air: rapid, minute alterations of pressure whose sum is zero and which contribute only to the entropy of the universe. From this one might easily argue that music is really nothing, leaving us to protest that some nothings are more desirable than others.

Nobody takes this sort of paradox seriously, of course; but, paradox serves rightfully as our point of departure. Notwithstanding the effort expended here to treat this subject systematically, the reader who looks for invariable principles from which to draw unassailable conclusions will find little satisfaction in what follows. Everything in music argues that such rigor is illusory, and only a musician with very limited experience would seriously pursue it. Yet, musical scholarship requires at least a degree of consistency as one of its necessary conditions. I shall attempt to reconcile that requirement with our often hopelessly paradoxical subject.

Let us pursue paradox a little further. We define word painting as the representation, through purely musical (sonorous) means, of some object, activity, or idea that lies outside the domain of music itself. But music itself (as we have «shown») is next to nothing physically; therefore, it can truly represent nothing. Music exists primarily on an aesthetic plane. It represents itself. If it communicates anything more than compulsive twitches and primal screams, it does so by some cultural agreement, by some convention less precise perhaps than that of language; but, like language, ethnocentric and ever evolving.

Language has even absorbed one musical convention so completely that we have to remind ourselves that it is purely artificial; there’s nothing in it. Speak, write, reason as we will about «high» and «low» notes in music, nothing justifies those adjectives. All notes emitted by the same source, whether high or low, issue from the same point (for all practical purposes) and radiate into the same air. They do not differ in their placements in physical space—unless we choose to quibble that the piano’s higher strings lie to the right of the lower ones. Notes have no altitude. Our stubborn belief in «high notes» and «low notes» as natural and rational expressions in the face of reality, merely emphasizes the ethnocentricity of our convention. The musicians of Classical Greece—a culture probably more obsessed with rationality than any other in recorded history—looked at things the other way around. Our «high» notes were their «low» notes; their scale ran in the opposite direction to ours.4 And with good reason unpolluted by subjective equivocation. After all, when one played the lyre, did not the string with the larger frequency (our higher note) lie closer to the ground? The modern guitarist who plays with the same configuration may well wonder if the Greeks did not have a better word for it after all.

For better or worse, our musical traditions are not those of Classical Greece, but those of the Northern barbarians. The most momentous single phenomenon in the whole history of Western Music took form, probably in the 9th century, when Frankish musical scribes began to distinguish between the sounds they were already calling «high» and «low» by some kind of vertical distinction between their alignments on the page.5 From this seed, already evident in some of the expedients of the anonymous Musica enchiriadis,6 sprang the notations of plainchant and the Ninth Symphony. And all because Charlemagne, an illiterate, wanted all his subjects to march to the same drummer (or at least the same musical liturgy). He was unable to understand why scribes could write down his words, but not the music he heard.7

The leap from Carolingian innovations to the English madrigal may seem chronologically enormous, but it’s not so great conceptually. Thus, when John Bennet, in his popular Weep, O mine eyes,8 reaches the lines, «O when, O when begin you / to swell so high that I may drown me in you?» all the parts reach their local high-point on the word «high» (their highest notes in the piece for all but the soprano), and then dip downward to the word «drown.» Bennet’s writing seems so simply and naturally expressive that no one would condemn his treatment as a mannerism or cliché. Yet this is one of two devices that come most readily to mind at the mention of the comprehensive term «madrigalism.» Throughout the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, the application of higher notes to words alluding to height or high places (sky, heaven, etc.) and lower notes to contrary meanings, became almost inescapable in mass, motet, madrigal, anthem, lute song, and opera. Almost unlimited numbers of examples testify to the prevalence of this habit which we may label the Directional Convention.

It was surely no Baroque composer who could compose the children’s round, «Row, row, row your boat gently down the stream» to an ascending melody! But, our musical instincts about what seems natural and rational suffer another blow when we look for early examples of this presumably inevitable directional convention. It seems to go back no farther than the progressive composers of the Josquin generation. In masses by earlier or more conservative composers, as often as not, ascendit meanders downward, and descendit leaps upward, while caeli et terra have their «altitudes» reversed with a regularity bordering on perversity. The word «perversity» may seem a bit harsh when we remember that the 15th century understood «high music» to mean loud, outdoor music, and «low music» to mean the softer music of the chamber. Nevertheless, the seeming indifference of such important composers as Dufay, Ockeghem, and Obrecht, to so «natural and rational» a convention brings us face to face with a serious problem in the study of word painting: How can we recognize true word painting? That is, how can we distinguish between the purposed musical realization of a text and our own fanciful reading imposed upon fortuitously conformable music? We cannot do so with complete certainty, but we must try to resolve such questions beyond a reasonable doubt, if we hope ever to write the history of one of the chief expressive and organizing features of Renaissance and Baroque style.9 Hence it seems desirable to take account of some present dangers that beset any study of word painting.

The first lies within ourselves as analysts. Even though we know better, we look for rules, laws, unbending principles in the hope that they may lead us to explanations of musical phenomena, while we tend to reject those casual rules of thumb that have the least hint of inconsistency about them. Whether or not consistent laws exist for other musical practices, they do not exist for word painting. It does not depend upon single-valued conventions for which we may compile a vocabulary of definitions. Even the most conventional gesture may have many possible interpretations, or none at all. For example, chromaticism (the other device most often associated with the term madrigalism) often expresses intensely painful emotions. Yet, no matter how widespread that use of chromaticism may have been, the various intensely chromatic keyboard pieces called Consonanze stravaganti by Giovanni de Macque,10 Gioanpietro del Buono,11 and Giovanni Maria Trabacci12 certainly intended nothing beyond the exuberance of chromatic experiment.13 Word painting, then, is not some kind of «code» that «explains» a piece of music. At best, where we happen to understand the conventions the composer has chosen to employ, it allows us a glimpse of his reading of his text—no small gain given the cultural gap that separates us from his style.

From the Romantic era we inherit yet another internal danger. The Romantics turned music into a near sacred vocation and composers into demigods who justified their elevation gloriously, whereas their musical forebears had achieved no less glory as dedicated craftsmen. The Romantics gave us the notion that only purely inspired musical creation—whatever that may be—is worthy of the admiration of the elect; that in comparison with abstractly conceived compositions, literal word painting must seem somehow inferior. Under this intimidating influence Berlioz grew ashamed of the program of his Symphonie fantastique and became the first voice of that chorus that continues to urge us to close our ears to half of its emotion. The program and the music are not incompatible; they nourish each other. Even if a Renaissance composer should have set out to «translate» his text into music, his success rested on the musical virtues of his work, not on the literalness of his translation. Literalness need not—indeed, rarely does—interfere with the musicality of the results. Just as a fine sonata must always surpass mere textbook commonplaces, a successful musical discourse must always transcend those rhetorical ingenuities which may form its substructure or animate its surface. The literalness of some of those details awakens a lurking uneasiness among some who fear it, without foundation, as a usurper of genuine musical values. Nevertheless, we who come after would be ill-advised to spurn its clues to the better understanding of a work of the past. Such scruples do not worry the world of rock, where pretentious musical illiterates peddle the «musical message» of some number according to its words, its costumes, its amps, and the staged frenzy of its performers. However remunerative such writing may be, it serves here merely to remind us that, in the search for authentic musical values, we must avoid looking for the wrong ones. We must accept word painting as a factor that contributes to musical value, but does not and cannot substitute for it.

Another caution: nothing obliges a composer to be consistent. Then as now, nothing required him to treat the same topos in the same fashion from piece to piece, or even within the same piece if it happened to recur. Still, we may not anachronistically imagine him tiring of some particular usage. («Oh, I did that once; it bores me to do it again!») The composer-craftsman of the past had a more practical respect for the techniques he had been taught or had learned for himself. We may see how he applied some of his techniques, but since we do not yet know the basis on which he chose among his options, we may actually admire his work for the wrong reasons. What we perceive as aptness, his contemporaries may have taken as conventional; where we admire inventiveness, his equally admiring colleagues may have approved his characteristic response to the implications of the text. We cannot hope to appreciate his work fully until we understand what choices he had available to him. Some decisions were made for him by the external history of the piece: the occasion, the preferences of his patron, the forces available, etc. Within these or similar constraints, he had to look at his text not very differently from the way an opera composer looks at a libretto: as a fundamental part of the composition, but always susceptible to some degree of adjustment. The composer may modify the structure of his text in several ways: he may repeat units, he may combine separate text units into a single musical unit, he may break up a unit of text into two or more musical units. As he proceeds, he must decide at every point which particular combination of voices he will assign to each word and phrase of text, with what degree of prominence and emphasis, what texture, what balance, and what particular combination of musical techniques—of which word painting is but one. Melody, rhythm, and harmony, the surface features of the music, must emerge out of this complex background of pre-conditions—or perhaps better: co-existent ideas—often rendered more complicated by the pre-existent materials of cantus firmus, paraphrase, or parody. Word-painting is one of the prominent text-music relationships that we may reasonably expect to help us make sense out of that welter of pre-conditions.

The foregoing remarks imply yet another caution: even in the work of the most doctrinaire madrigalist, word painting is not omnipresent. The presence of a text invites a composer to respond to it, but the composer—whether Ockeghem or Stravinsky—may choose to ignore it. We need to know what elements in a text induce a composer to bend his music to it, but we need to know, also, the nature of the musical situations that lead him to overrule the appeal of the text. Such matters will require years of attention from many scholars.14

The context in which we find a device of word painting raises another question. In a text that presents the words «high» and «low,» we would ordinarily expect to hear them sung on relatively higher and lower notes respectively. This usually happens in the normal conduct of word painting, but not always. Let us construct a hypothetical example using the text, «he ran about looking high, and ran about looking low,» sung all on one repeated note, except for the word «looking,» which sounds a third higher than the repeated note in the first half of the line, and a fourth lower than the repeated note at its second occurrence. If the style of the rest of the piece did not contradict us, we would deduce (probably correctly) that the composer had a textual motivation for the shape of his line. The proximity of the upward and downward leaps to words of parallel imagery seems to associate them with those meanings. But what happens if we increase the distance by placing the leaps on «ran» instead of «looking»? Or, pushing the matter further, suppose each half of the line were set to but a single note, the first a fifth higher than the second? a third higher? a step higher? We may find no difficulty in recognizing pictorial intent in every one of these examples, depending on the context in which we find them. This high-low prejudice eventually becomes so strong that, even where a composer avoids word painting in order to shift emphasis to another point in the text, I believe we may often detect a reluctance to set words like caeli et terra in reversed positions. Terra may occur only a step lower, or even on the same step, but only rarely higher than caeli.

Let us form another artificial example out of the text, «I climb to heaven, only to fall to earth»—a routine job for the practiced word-painter. He would probably look for appropriate melodies rising on «climb» to peak at «heaven,» and descending on «fall» to reach a low-point on «earth.» But suppose the line had read: «to heaven I climb, to earth I fall»? An attempt to parallel the meanings of the four key words, although not impossible, could lead the composer into awkward constructions. Faced with such a problem, the composer could set this new version of our text to the same sort of music as our first version, even though that would mean leaving «heaven» at the lower end of his upward run, and «earth» at the upper end of his downward run. Here again, the context allows reason enough to read pictorial intent in the passage: upward motion still decorates the upward image, downward motion sets the downward image, and the local discrepancies in the positions of «heaven» and «earth» lose their importance to the larger context. Obviously, one might push such interpretations beyond reasonable bounds; for example, when Ockeghem sets each noun of caeli et terra with both upward and downward motions (as in the Sanctus of his Missa Mi-mi),15 we have no right to label the conformable motions as pictorial and simply dismiss the inconvenient ones. Moreover, Ockeghem’s masses taken together do not offer consistent evidence of pictorial concern. Even allowing for the uncertainties in the underlay of the sources, a preponderance of evidence argues against pictorial interpretation.

As one last example of the role of context, let us imagine a poem of unrequited love which places the word «pain» at a verbally significant position. Suppose that position does not suit the composer musically (for whatever reason), and he decides not to apply the usual chromatic motion (or chromatic harmony) directly on the painful word. If he places the chromaticism somewhere in the same musical phrase, we may readily understand it (just as in our preceding example, regardless of what words it sets) as conventional word painting. But, let us suppose he chooses to distribute chromaticism liberally everywhere throughout the piece, but not in the key phrase. Could he possibly have intended the omission as a kind of noema, emphasizing the idea by understatement? But what of all the other chromaticisms in the piece? Do we take them as word painting in the narrow sense, as symbols of pain applied locally, or as a response to the prevailing idea of the pain of unrequited love? It takes a thoughtful reading of both poem and music if one hopes to arrive at a responsible opinion of such treatments. Since word painting can function at many levels,16 an analysis must account for all of them. It is quite possible to miss the forest for the trees; to pass over larger pictorial implications while successfully cataloguing all the local devices.

Underlay presents us with another danger. The sources that preserve older music usually fail to align the syllables of a text with their proper notes, leaving us to guess, most of the time, at what the composer may have intended. We must review all underlay critically, because whether analyzing a composition or making any judgment at all about its word painting, we do so on the assumption that the words and the music that symbolizes them are in proper alignment. As every transcriber of early music knows (or ought to know), underlay is largely an analytical problem. The theorists tell us less than we need to know, while the sources often disagree with them and with each other. This observation takes nothing away from the authority of either the theorists or sources, but it reminds us that we need all the help we can get. We have every reason to suppose that a better understanding of word painting practices would offer some help. If we knew more about the conventions appropriate to the style of the piece being transcribed, we could recognize certain fixed points in the text as sites to which a composer might apply one of the appropriate devices. If one of the common devices of that style should happen to stand not far from appropriate words, we might have reason to underlay it with them—thus reducing the areas of uncertain text placement to the distance from one fixed point to the next. Small help, perhaps, but not to be disdained.

The question of underlay raises yet another hobgoblin: the question of contrafactum which can afflict both plainsong and polyphony. The Renaissance and Baroque habit of substituting a new text for the original one in an already completed composition (in order to make it suitable for another occasion) can make a mockery of a word painting study. However, the case is not so clear-cut. Since the counterfeiter knew the conventions of his time better than we do, he could well have chosen the piece or adjusted the text in such a way as to preserve some word painting of the original—or even to make some appear where the original had none at all. Some of Bach’s adaptations of earlier cantatas seem to hold out this possibility. After the English Reformation, some formerly Latin motets acquired amazingly felicitous English texts. Strophic compositions, too, are a kind of contrafactum; in the absence of other evidence, we usually assume that the composer set only the first stanza; that assumption remains untested. Whatever the problem, the validity of our judgments about a text-music relationship hinges—as does every other kind of analysis—on our having the authentic text before us.

The perils arising from such pitfalls lead many to mistrust the subjective element that must affect this sort of study for a long time to come. However, whether in our hypotheses or in our practice, the judicious exercise of subjectivity cannot be avoided in any kind of musical analysis. It becomes abhorrent only when it masquerades as objective science.

| * | * | * | * | * | * |

What creative value can word painting possibly have had in the process of composition? Its meaning for us depends on that. It must have had considerable value for so many composers of demonstrable genius to have employed it for so many generations. To make the issues a little clearer, let us leave aside the more glamorous or dramatic applications of it in motet and madrigal, and consider a lesson we may draw from the repertory of masses.

A composer would have been likely to set the words of the Ordinary of the Mass many times in the course of his career, and the works of, say a Josquin or a Palestrina, give us reason to believe that a dedicated craftsman would always seek fresh and interesting ways to fulfill that recurrent commission—but within the vocabulary of received contemporary practices. The structure of the Mass text formed a natural basis for the structure of his music, and the conventions that might apply to each segment of text provided him, at each moment, with a set of possibilities which always included the possibility of evading the conventions. Like the sets of standard cadences and the rules of counterpoint, word painting was but one of the options conventionally available to him. If he declined them all—that is, if he embarked upon a path of «free» composition—he followed a most uncommon practice. Composition was rarely completely free in any of the arts. Most often, it made use of pre-existent models or materials in one form or another. A composition formed upon no prior melody or polyphony, and which also disregarded all conventional rhetoric would have been rare indeed. Such compositions usually spring from some constructivist principle, from canon, soggetto cavato dalle vocali, and the like. The idea of total freedom had little aesthetic meaning for a composer. It had no basis in his training or his social outlook before Romanticism reshaped the creative world. Therefore, when we find ourselves tempted to call a passage or a composition «free,» it may mean only that we don’t know what the composer is doing.

When a composer writing a mass chose some of the possibilities available to him and rejected others, he created emphasis by both his choices and his omissions from the vocabulary of standard conventions. In effect he gave his discourse an individual stamp that had meaning for his contemporaries. Today, many listeners find one 16th-century mass much like another except that the tunes of one may please them more than another. That attitude would have seemed naive in the 16th century, when paraphrase and parody techniques generated whole tangles of masses based on the same tunes. The 16th-century connoisseur undoubtedly enjoyed the tunes in such masses as well as we do, but he gave his critical attention to the fertility of imagination with which the composer renewed and invigorated the given materials, musical and textual. Just as the pre-existent musical materials could be re-worked with endless variety, so could the text of the Mass. A mass was a mass; what mattered was how a composer said his Mass (or motet, or madrigal, etc.). For us to ignore this challenge of musical aesthetics, to ignore the way a composer said his text, is as willfully ignorant and as marginally musical as listening to Schubert Lieder or Verdi operas simply to enjoy the tunes—or worse, just the voices. The fact that unlettered listeners with just such tastes make up the preponderant majority of the musical public does not discredit the assertion. If anything, it bolsters it. To take any other view would be tantamount to redefining the brilliant musical creations of our heritage according to the irresponsible whims of our own age. Of course, we cannot help being of our own time and society. But, if the art of the past has any message worth receiving, it must speak to us in its own voice, not ours. Great works of art do not reach us through movie versions of Moby Dick and Tom Jones or rock versions of the Pirates of Penzance and the Bible. Those are the voices of our culturally anaesthetized kinfolk speaking and listening only to themselves. Let us count our blessings.

Dedicated musicians and musical scholars know that we can never completely recover the past. That is not our goal, nor should it be. Our aim is to communicate with the past as well as we can in order to derive profit from its musical treasures so different from our own—riches we can only simulate. Therefore, since the composers of the past bent themselves to the task of discoursing upon a text to the best of their abilities, we must take pains to understand their responses to that text if we would truly hear their music.*

1The substance of this essay is drawn from the author’s book in progress, Music and Words: A Systematic Examination of Madrigalism and Other Text-Influences on Music. It will provide tools for the solution of a number of the problems raised below.

2For some songs truly without words see Owen Jander, «Vocalise» in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, edited by Stanley Sadie (London, 1980), 20, p. 51, to which we may add: Stravinsky’s Pastorale (1907), and Henry Cowell’s Vocalise (1937) and Toccanta (1938).

3As far as I know, the first comprehensive analytical program to allow text-influence a significant role in its scheme is Jan LaRue’s Guidelines for Style Analysis (New York: Norton, 1970). LaRue makes a good beginning, although he is concerned chiefly with instrumental music.

4See almost any standard text book. To cite but one: Donald Jay Grout, A History of Western Music, 3rd edition (New York: Norton, 1980), pp. 28 ff.

5For an investigation of the early history of this phenomenon, see: Leo Treitler, «The Early History of Music Writing in the West,» Journal of the American Musicological Society, XXXV (1982), 237-279.

6Diplomatic facsimiles of these expedients are conveniently available in the translation of Léonie Rosenstiel, Colorado College Music Press Translations, 7, Albert Seay, ed. (Colorado Springs, 1974), pp. 6 ff, et passim.

7For an account of Charlemagne’s role in this development, see: Leo Treitler, «Homer and Gregory: The Transmission of Epic Poetry and Plainchant,» The Musical Quarterly, LX (1974), 338 ff.

8Edmund H. Fellowes, The English Madrigal School, XXIII: John Bennet, Madrigals to Four Voices (1599) (London, 1922), pp. 60-62.

9See note 1.

10For a brief example see Willi Apel, The History of Keyboard Music to 1700 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1972), pp. 425.

11For a brief example see Willi Apel, op. cit., p. 493.

12Luigi Torchi, L’arte musicale in Italia, III, p. 372, and also Roland Jackson, «On Frescobaldi’s Chromaticism and Its Background,» The Musical Quarterly, LVII (1971), 257.

13Although these are keyboard rather than vocal works the argument still holds, for there are many instrumental works with comparable text associations that cannot be challenged; see note 1.

14See note 1.

15Johannes Ockeghem: Collected Works, ed. Dragan Plamenac, 2nd edition (New York, 1966), II, p. 15, mm. 29-38.

16A preliminary version of this idea (refined in the book in progress) appeared in my dissertation: Guillaume Costeley (1531-1606): Life and Works (New York University, 1969), pp.178-185.

*Special thanks are herewith offered to Martin Bernstein, who in many ways influenced the preparation of this study. Celebremus: 1984. xii. 14.

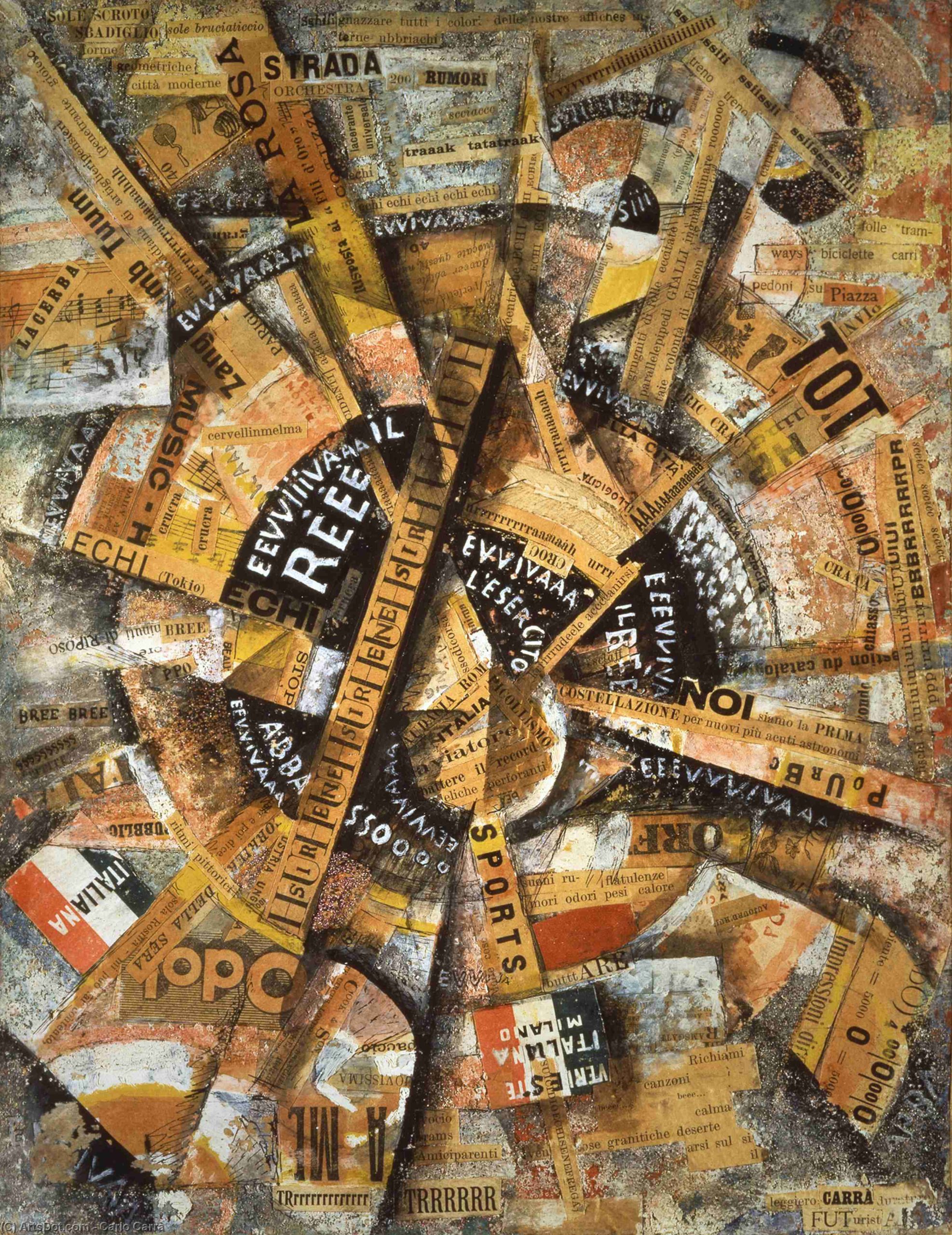

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting), 1914, tempera, pen, mica powder, and collage on cardboard, 38.5 x 30 cm (Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting), 1914, detail, 38.5 x 30 cm (Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

Created in the politically volatile days leading up to World War I, Carlo Carrà’s Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting) displays both the Italian Futurists’ avant-garde techniques and their militant nationalism. It is a collage painting that uses words as its primary element.

The composition rotates like an airplane propeller, and the word “aviator” is pasted at its heart. Dozens of pasted and painted words fan out from the center like voices shouting in a crowd. There are clippings from advertisements, Futurist poems, and newspaper articles, as well as two painted Italian flags and graffiti-like inscriptions of popular slogans supporting the Italian army and king, and condemning Austria.

Instructions from a propeller

Free word painting is a development of Filippo Marinetti’s parole in libertà — “words in freedom,” often translated as “free word poetry.” Inspired by the intensity of his experiences as a war correspondent in Libya, Marinetti first described parole in libertà as instructions emanating from an airplane propeller. The instructions included the abolition of syntax, punctuation, conjunctions, adverbs, and adjectives. Verbs must be used only in the infinitive form.

These restrictions defined a poetry largely based on conjunctions of nouns intended to directly express things and their physical qualities. For example, a section of Marinetti’s first free word poem Battle of Weight + Smell reads, “20 meters battalions-ants cavalry-spiders roads-fords general-island couriers-locusts sands-revolution howitzers-grandstands clouds-grates guns-martyrs . . .” [1]

A multi-sensory approach

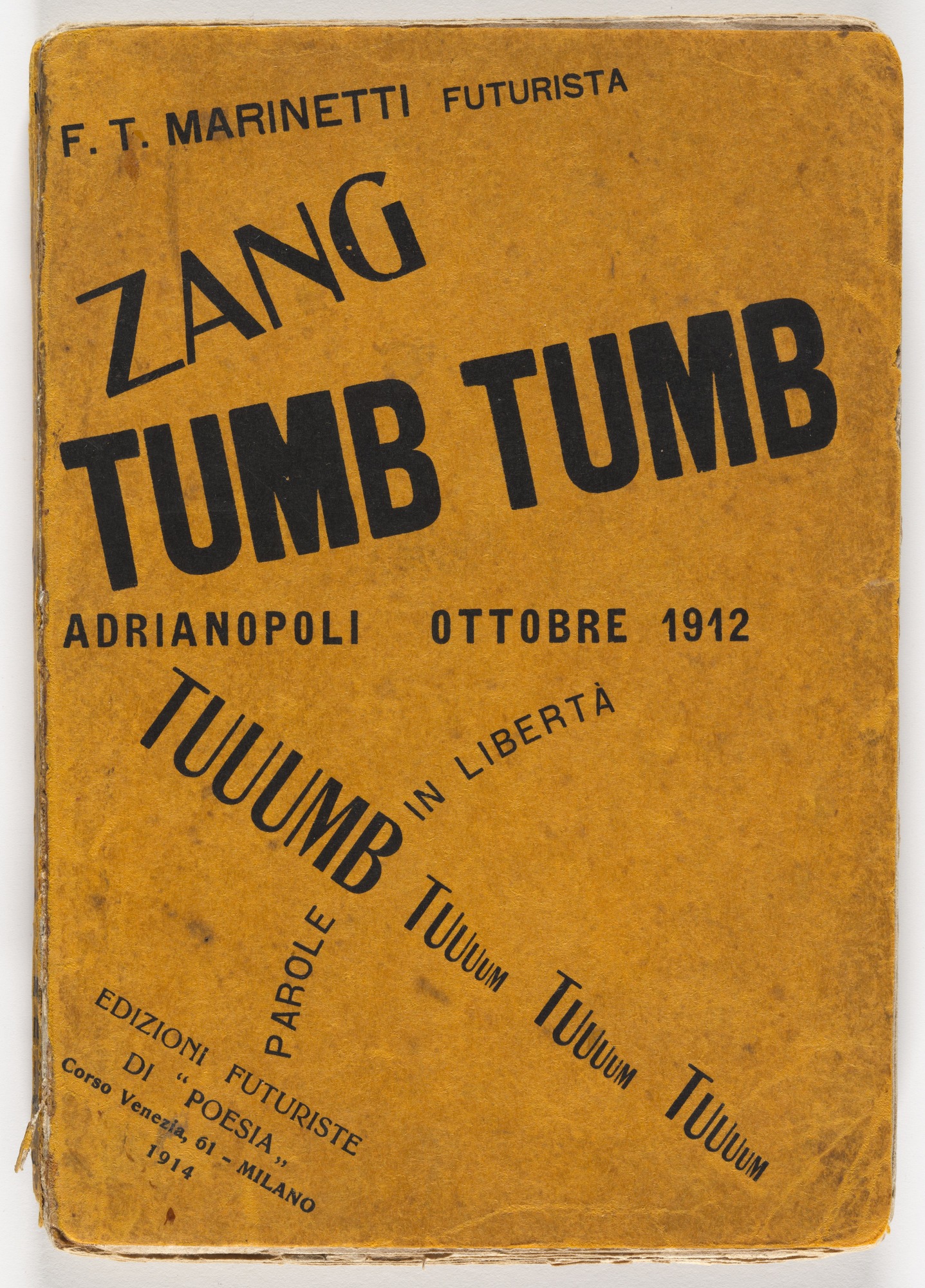

The Futurists developed multi-sensory approaches to communicate the experiences of physical reality. Instead of description, Futurist poets used onomatopoeia to convey sounds directly. The title of Marinetti’s poem ZANG TUMB TUUUM is onomatopoeic; the “words” are the successive sounds of an artillery shell firing, exploding, and reverberating.

Filippo Marinetti, Cover of ZANG TUMB TUUUM, 1914

In addition to sound, parole in libertà appealed directly to vision and instigated a revolution in typography. The cover of ZANG TUMB TUUUM uses different weights of type to signify the relative volume of different sounds and layout to convey relationships and physical movement. ZANG is on top and angles steeply upward to indicate the firing of the shell. The twice-repeated TUMB is lower and heavier to convey the booming impact of the shell and the power of the explosion. The diminishing echoes of the sonic reverberation are represented below by the steep down-sloping TUUUMBs that shrink with each repetition.

While Futurist poets added concrete aural and visual dimension to their poems, Futurist artists worked to expand the sensory appeal of their works beyond the visual. Carlo Carrà published a manifesto in which he called for painters to express sounds and smells through the use of shape and color. He claimed that all sounds and smells are dynamic vibrating intensities that provoke mental shapes and colors. This is a reference to a well-known perceptual phenomenon known as synesthesia, which can affect people in varying ways. Some people, for example, see colors when they hear music, while others smell a specific odor when they see a particular color. Synesthesia played an important role in the development of abstract painting in the early 20th century, most famously in the theories of Vasily Kandinsky.

Eliminating boundaries

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting), 1914, 38.5 x 30 cm (Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

The dynamic arrangement of words in Interventionist Demonstration creates a vortex of expressive significance that sucks the viewer into the composition. There are no still or stable places in the painting. The expanding, radiating composition, along with the inconsistent orientation of the lines of text, suggests that the sounds are coming at the viewer from all sides, dissolving the traditional boundary between viewer and artwork. This was a key goal of the Futurist painters, who wanted to create the sensation of immediacy and aimed to place the viewer in the center of the artwork.

Eliminating boundaries between the senses and between artistic media was also crucial for the Futurists. Carrà intended his painting to communicate emotion directly and synesthetically by means of color, shape, and composition, as well as by words. In addition to political slogans, most of the collaged words are references to Futurist themes, including the city and its crowds, sports and speed, sounds and music, colors and odors. There are numerous violent-sounding onomatopoeic words as well, including the title of Marinetti’s poem ZANG TUMB TUUUM pasted in the upper left.

A twirling dancer

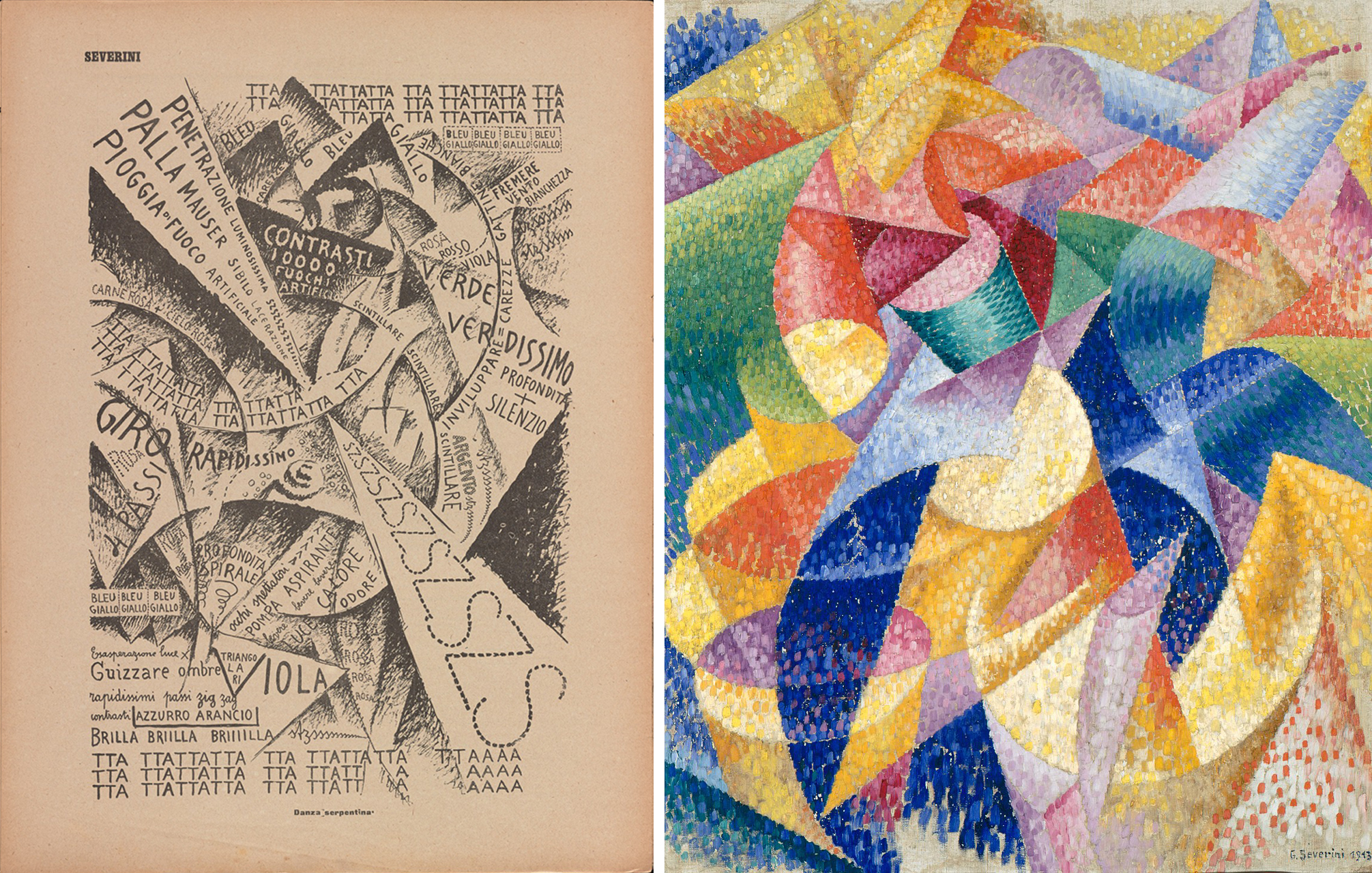

Left: Gino Severini, Serpentine Dancer, in Lacerba (July 1, 1914), p. 202; Right: Gino Severini, Sea = Dancer, 1914, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 31 11/16 inches (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

Gino Severini’s Serpentine Dancer uses an approach similar to that of Carrà’s Interventionist Demonstration. It represents the experience of watching a dancer in a nightclub. The abstract composition combines semi-circular arcs accompanied by acute triangles and stark contrasts of black and white. The forms of the drawing are comparable to Severini’s Sea = Dancer, painted only a few months earlier.

Reinforcing the equivalencies of words, sounds, and colors, the drawing includes many names of colors (verde, bleu, giallo, azzurro), as well as onomatopoeic sounds like TTATTA and SZSX. Words of different sizes are woven through the image, creating repeating patterns, echoing shapes in contrasting tones, and contributing both sound and meaning.

Severini indicated the twirling of the dancer with both repeated arcs and the words giro rapidissimo (rapid turn) and profondita spirale (deep spiral). Luce (light), calor (heat), and odore (odor) evoke the sensory experience of being in the nightclub. Piogga di fuoco artificiale (rain of fireworks), palla mauser sililo lacerazione (hissing Mauser pistol shot) and penetrazione luminosissima szszsz (luminous penetration) slash through the image in a white triangle that pierces the heart of the image. They remind us that for the Futurists any mass activity, including the pleasures of nightclubs and dancing, went hand in hand with a desire to incite violence, riot, and war.

On the battlefield

Painted a year later, Severini’s Cannon in Action uses similar techniques to communicate the experience of soldiers on the battlefield in World War I. Rather than representing the twirling of a dancer, this composition explodes out from the center in curves and arcs that convey the power and noise of a cannon firing. In keeping with the Futurists’ love of machinery, a cannon and armored vehicle dominate the scene with soldiers serving as their faceless accessories. Written words follow the painted forms, and most are informational and descriptive, just as the painting is largely representational rather than abstract. For example, the phrases written in the cloud of smoke behind the cannon are all comments on the horrible smell.

The Futurists’ parole in libertà and the development of free word painting arose from their desire to break down the divisions between different art forms to communicate feeling directly. Words, sounds, images, shapes, and colors were all used to convey the intensity of experience and bring the viewer into the heart of the action, be it participating in a crowd in a city square, dancing in a nightclub, or joining artillery men on a battlefield.

Notes:

- Translated in Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 207.

Additional resources:

Read about “words in freedom” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s Checklist blog

Read Carlo Carrà’s manifesto, The Painting of Sounds, Noises, and Odors

Read Filippo Marinetti’s Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature