Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Mr. Clemens Kub

Score: 5/5

(64 votes)

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is characteristics of use of word painting?

Word painting is a compositional style of setting the melody so it vividly depicts the imagery, and actions taking place in the music. For instance words with a negative connotation such as descending, death, ground,etc. will have a melody with a downward movement of pitch.

What is the use of word painting?

Musical depiction of words in text. Using the device of word painting, the music tries to imitate the emotion, action, or natural sounds as described in the text. For example, if the text describes a sad event, the music might be in a minor key.

What is word painting in literature?

n. 1. The technique of using the phonic qualities of words to suggest or reinforce their meaning, especially in poetry.

Which genre uses word painting?

Word painting is a device used frequently in Renaissance vocal music, especially madrigals—although it certainly also appeared in church music—in which the musical events are designed to illustrate or reflect the text.

35 related questions found

How do you describe the word painting in music?

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

What is the definition of word painting in music?

Word painting is when the melody of a song actually reflects the meaning of the words. The best way to learn about it is to listen.

Which of the following would be the best definition of word painting?

Word painting is when the music describes the action. … An example of word painting would be when someone is going down a hill, the music descends as well.

What is the difference between word painting and declamation?

How a text is set to music is called its declamation. Recitative and word painting are two types of musical declamation: recitative is a speech-like, declamatory singing style that emphasizes the important syllables and words of the text, while word painting is a musical illustration of a word being sung.

What is word painting give a brief example?

Word painting is the technique of creating lyrics that reflect literally alongside the music of a song and vice versa. For example, singing the word “stop” as the music cuts out. Depending on which you write first (music or lyrics) it can be carried out in any order.

What is word painting MUS 121?

What is word painting? A musical concept in which melodies depict specific words that are sung (like notes going higher in pitch on the word «ascend»).

How do you describe the texture of a song?

Texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices.

What is the definition of word painting quizlet?

Word painting (also known as tone painting or text painting) is the musical technique of writing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

How did Renaissance composers use word painting in their music?

Word painting was utilized by Renaissance composers to represent poetic images musically. For example, an ascending me- lodic line would portray the text “ascension to heaven.” Or a series of rapid notes would represent running.

How is word painting used in as Vesta was descending?

“Vest” from vesta is the strong pulse. “From Latmos Hill” is always a three-note ascending motif in imitative counterpoint to illustrate a hill, and then when the voices sing “descending,” the scale reverses and descends. This is the first demonstration of word painting in this composition.

What is the tone of a painting?

In painting, tone refers to the relative lightness or darkness of a colour (see also chiaroscuro). One colour can have an almost infinite number of different tones. Tone can also mean the colour itself.

What is abstract art with words?

Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect. Wassily Kandinsky. Cossacks 1910–1. Tate. Strictly speaking, the word abstract means to separate or withdraw something from something else.

What is the definition of a chanson?

: song specifically : a music-hall or cabaret song.

Where did the word painting come from?

1300, «decorate (something or someone) with drawings or pictures;» early 14c., «put color or stain on the surface of; coat or cover with a color or colors;» from Old French peintier «to paint,» from peint, past participle of peindre «to paint,» from Latin pingere «to paint, represent in a picture, stain; embroider, …

Which is true of an aria?

What is true of recitatives? An aria is: … and extended piece for a solo singer having more musical elaboration and a steadier pulse than recitative.

Which of the following are known Madrigalists?

Some of the best known of the English madrigalists include Thomas Morley (1558-1602), Francis Pilkington (ca. 1570-1638), William Byrd (1543-1623), Orlando Gibbons(1583-1625), and Thomas Weelkes (1576-1623).

Which composer used word painting which used music to reflect the literal meaning of the words?

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Handel’s music is the use of “word-painting,” the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics. For example, ascending scales would accompany lyrics about going up; slow, dark music would accompany lyrics about death.

What is the texture of Renaissance?

The texture of Renaissance music is that of a polyphonic style of blending vocal and instrumental music for a unified effect.

What is a melismatic melody?

Melisma (Greek: μέλισμα, melisma, song, air, melody; from μέλος, melos, song, melody, plural: melismata) is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. … An informal term for melisma is a vocal run.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For paintings and other art incorporating text, see Word art.

Word painting, also known as tone painting or text painting, is the musical technique of composing music that reflects the literal meaning of a song’s lyrics or story elements in programmatic music.

Historical development[edit]

Tone painting of words goes at least as far back as Gregorian chant. Musical patterns expressed both emotive ideas and theological meanings in these chants. For instance, the pattern fa-mi-sol-la signifies the humiliation and death of Christ and his resurrection into glory. Fa-mi signifies deprecation, while sol is the note of the resurrection, and la is above the resurrection, His heavenly glory («surrexit Jesus«). Such musical words are placed on words from the Biblical Latin text; for instance when fa-mi-sol-la is placed on «et libera» (e.g., introit for Sexagesima Sunday) in the Christian faith it signifies that Christ liberates us from sin through his death and resurrection.[1]

Word painting developed especially in the late 16th century among Italian and English composers of madrigals, to such an extent that word painting devices came to be called madrigalisms. While it originated in secular music, it made its way into other vocal music of the period. While this mannerism became a prominent feature of madrigals of the late 16th century, including both Italian and English, it encountered sharp criticism from some composers. Thomas Campion, writing in the preface to his first book of lute songs in 1601, said of it: «… where the nature of everie word is precisely expresst in the Note … such childish observing of words is altogether ridiculous.»[2]

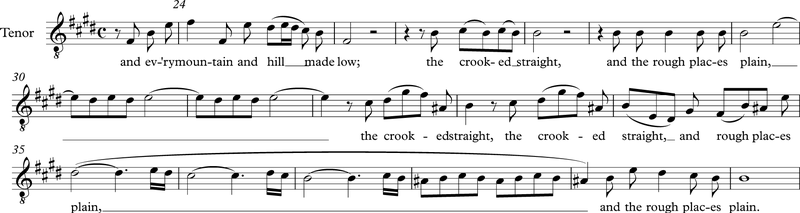

Word painting flourished well into the Baroque music period. One well-known example occurs in Handel’s Messiah, where a tenor aria contains Handel’s setting of the text:[3]

- Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill made low; the crooked straight, and the rough places plain. (Isaiah 40:4)[4]

In Handel’s melody, the word «valley» ends on a low note, «exalted» is a rising figure; «mountain» forms a peak in the melody, and «hill» a smaller one, while «low» is another low note. «Crooked» is sung to a rapid figure of four different notes, while «straight» is sung on a single note, and in «the rough places plain», «the rough places» is sung over short, separate notes whereas the final word «plain» is extended over several measures in a series of long notes. This can be seen in the following example:[5]

In popular music[edit]

There are countless examples of word painting in 20th century music.

One example occurs in the song «Friends in Low Places» by Garth Brooks. During the chorus, Brooks sings the word «low» on a low note.[6] Similarly, on The Who’s album Tommy, the song «Smash the Mirror» contains the line «Rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise, rise….» Each repetition of «rise» is a semitone higher than the last, making this an especially overt example of word-painting.[7]

«Hallelujah» by Leonard Cohen includes another example of word painting. In the line «It goes like this the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift, the baffled king composing hallelujah,» the lyrics signify the song’s chord progression.[8]

Justin Timberlake’s song «What Goes Around» is another popular example of text painting. The lyrics

- What goes around, goes around, goes around

- Comes all the way back around

descend an octave and then return to the upper octave, as though it was going around in a circle.

In the chorus of «Up Where We Belong» recorded by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes, the melody rises during the words «Love lift us up».

In Johnny Cash’s «Ring of Fire», there is an inverse word painting where «down, down, down» is sung to the notes rising, and ‘higher’ is sung dropping from a higher to a lower note.

In Jim Reeves’s version of the Joe Allison and Audrey Allison song «He’ll Have to Go,» the singer’s voice sinks on the last word of the line, «I’ll tell the man to turn the juke box way down low.»

When Warren Zevon sings «I think I’m sinking down,» on his song «Carmelita,» his voice sinks on the word «down.»

In Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s «My Romance,» the melody jumps to a higher note on the word «rising» in the line «My romance doesn’t need a castle rising in Spain.»

In recordings of George and Ira Gershwin’s «They Can’t Take That Away from Me,» Ella Fitzgerald and others intentionally sing the wrong note on the word «key» in the phrase «the way you sing off-key».[9]

Another inverse happens during the song «A Spoonful of Sugar» from Mary Poppins, as, during the line «Just a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down,» the words «go down» leap from a lower to a higher note.

In Follies, Stephen Sondheim’s first time composing the words and music together, the number «Who’s That Woman?» contains the line «Who’s been riding for a fall?» followed by a downward glissando and bass bump, and then the line «Who is she who plays the clown?» followed by mocking saxophone wobbles.

At the beginning of the first chorus in Luis Fonsi’s «Despacito», the music is slowed down when the word «despacito'»(slowly) is performed.

In Secret Garden’s «You Raise Me Up», the words «you raise me up» are sung in a rising scale at the beginning of the chorus.

Queen use word painting in many of their songs (in particular, those written by lead singer Freddie Mercury). In «Somebody to Love», each time the word «Lord» occurs, it is sung as the highest note at the end of an ascending passage. In the same piece, the lyrics «I’ve got no rhythm; I just keep losing my beat» fall on off beats to create the impression that he is out of time.

Queen also uses word painting through music recording technology in their song «Killer Queen» where a flanger effect is placed on the vocals during the word «laser-beam» in bar 17.[10]

In Mariah Carey’s 1991 single Emotions word painting is used throughout the song. The first use of word painting is in the lyric «deeper than I’ve ever dreamed of» where she sings down to the bottom of the staff, another example is also in the lyric «You make me feel so high» with the word «high» being sung with arpeggios with the last note being an E7

In Miley Cyrus’ ‘Wrecking Ball’, every time the title of the song is mentioned, all instruments engage in one huge wall of sound, therefore mimicking the sound of a wrecking ball whenever the chorus comes in.

Burt Bacharach uses word-painting in the song ‘In Between the Heartaches’ from Dionne Warwick’s Here_I_Am album. The song opens on an A-flat minor 11th chord. Dionne sings on the 11th of the chord (on the words…’In Between…’); a high E-flat briefly (on the word ‘the’); and back to the 11th and the 9th of the chord (on the word…’Heartaches…’) Those notes fall IN BETWEEN the notes of an A-flat minor triad (A-flat, C-flat, E-flat) making it a highly sophisticated example of word-painting.

See also[edit]

- Mickey Mousing

- Musica reservata

- Program music

- Eye music

References[edit]

- ^ Krasnicki, Ted. «The Introit For Sexagesima Sunday». New Liturgical Movement.

- ^ Thomas Campion, First Booke of Ayres (1601), quoted in von Fischer, Grove online

- ^ Jennens, Charles, ed. (1749). Messiah – via Wikisource.

- ^ «Isaiah#Chapter 40» . Bible (King James). 1769 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Bisson, Noël; Kidger, David. «Messiah: Listening Guide for Part I». First Nights (Literature & Arts B-51, Fall 2006, Harvard University). The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ «Word painting in songwriting…» The Song Writing Desk. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Ellul, Matthew. «How to Write Music». School of Composition. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ Ellul, Matthew. «How to Write Music». School of Composition. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ «A LEVEL Performance Studies: George Gershwin» (PDF). Oxford Cambridge and RSA (Version 1): 16. September 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ «Queen: ‘Killer Queen’ from the album Sheer Heart Attack» (PDF). Pearson Schools and FE Colleges. Area of study 2: Vocal Music: 97. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

Sources[edit]

- M. Clement Morin and Robert M. Fowells, «Gregorian Musical Words», in Choral essays: A Tribute to Roger Wagner, edited by Williams Wells Belan, San Carlos (CA): Thomas House Publications, 1993

- Sadie, Stanley. Word Painting. Carter, Tim. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Second edition, vol. 27.

- How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, Part 1, Disc 6, Robert Greenberg, San Francisco Conservatory of Music

-

#1

<<I like its word painting feature.>>

I’m trying to describe with one word (if possible) a kind of Internet graphic feature where the letters of a text are «painted out,» one letter at a time, in a continuous fashion. «Word painting» can be used to describe certain features of vocal music also, can’t it? Thanks in advance!

-

#2

«Word painting» can be used to describe certain features of vocal music also, can’t it?

Yes.

<<I like its word painting feature.>>

I’m trying to describe with one word (if possible) a kind of Internet graphic feature where the letters of a text are «painted out,» one letter at a time, in a continuous fashion.

The term should make sense to somebody who has seen this feature in a graphics application before and is familiar with what the feature does. If somebody is not familiar with the feature, I like its word painting feature will make little if any sense.

-

#3

A variation on that phrase is sometimes used to describe writers.

Despite all his faults as an author, Steven King could paint as vivid of a word picture of a scene as any other author I’ve read.

-

#4

If somebody is not familiar with the feature, I like its word painting feature will make little if any sense.

It makes no sense to me.

I’m trying to describe with one word (if possible) a kind of Internet graphic feature where the letters of a text are «painted out,» one letter at a time, in a continuous fashion.

This makes no sense to me either. What does «painted out» mean?

«Word painting» can be used to describe certain features of vocal music also, can’t it?

Is «vocal music» a new subject, or the same subject? Is this a different meaning of «word painting», or the same meaning?

Getting more and more confused…

-

#5

I used to “white out” words or letters when I used a typewriter. But on the computer I just delete it or use a

strike through.

-

#6

<<Getting more and more confused…>>

I think owlman5 understood the substance of «‘Word painting’ can be used to describe certain features of vocal music also, can’t it?»:

«Word painting» can be used to describe certain features of vocal music also, can’t it?

Yes.

-

#7

<<I like its word—painting feature.>>

A hyphen clears matters up.

However, it is not the correct term for

I’m trying to describe with one word (if possible) a kind of Internet graphic feature where the letters of a text are «painted out,» one letter at a time,

You need a phrase:

I like the way that the letters, one by one, spell out the words.

-

#8

The following video was approved by Cagey and Florentia52. I hope it exemplifies well the technique I was trying to identify above.

-

#9

That’s a movie of someone writing with a pen. No painting. The letters appearing one at a time is also not painting.

-

#10

«Word painting» (the musical kind) also has no «painting.» My understanding of figurative language (also called figures of speech) is that it describes expressions that are not «to be taken literally» as exact representations of the object/idea(s) described. (When Jesus called Herod a «fox,» my guess is that he was using what we call figurative language.)

Last edited: Aug 5, 2022

-

#11

«Word painting» (the musical kind) also has no «painting.»

I would take that to mean a metaphorical «painting a picture with words» via poetic imagery. Using it to describe literally drawing with a pen is like calling an apple a banana.

For each of the following sentences, identify the underlined word or word group by writing above it ADV for adverb, AP for adverb phrase, or AC for adverb clause. Then, circle the word or words the adverb, adverb phrase, or adverb clause modifies.

I raised my hand because I knew the answer‾underline{text{because I knew the answer}}.

681 reviews499 followers

Mostly a waste of time—

There are some useful advice and exercises, I admit, but after about page 100, it loses focus and starts to ramble on about topics that are MUCH better dealt by other books, such as characters, point of view, setting, and plot. It actually made me angry and frustrated to be reading about something that, to me, had little to do with «description.»

Her useful advice can be listed as follows:

-Use descriptive, not explanatory or labeling words

-Use sensory, concrete details

-Describe an object in motion; if not try using active verbs

-Consider describing something by negation and try to find something surprising about the object you are describing

-Try providing sensory details other than visual

That’s the gist of the book. On second thought, her useful tips and pointers are pretty commonsensical and I doubt it’s worth the price to be reminded of.

The first four chapters are the most relevant, the fifth chapter on metaphors is pretty much impractical (try finding your «constellation of images»), the subjects of Chapters Six and Seven are much better treated by Orson Scot Card in his Characters and Viewpoint, Chapter Eight is mostly useless, Chapter Nine presented a few useful techniques (quickening the pace by adding sensory details, sprinkling details for effect, and delaying revealing details to increase tension), and the last Chapter is a sustained rumble on mood, tone, psychic distance, and The Big Ear, which we are encouraged to cultivate.

Another minor yet personally important grievance involves her absurd claim that «physical description of a character is such an important element of most fiction» (p.119) and I must say that, au contraire, physical description is the LEAST important element. Who the hell cares what the main guy’s nose looks like (ahem, Maltese Falcon) or the color of his or her eyes or hair? Those are the LEAST memorable, too.

I’m more of a believer in showing characters through action (Card seems to think so too). Another example: Heinrich von Kleist, one of famous German writers/playwrights, did away with physical description and showed them through their action. And his stories are dramatic and riveting.

Don’t waste your time or money on this.

- japan_jul07-aug11 writing_reference

Author 1 book14 followers

This was an excellent guide for someone like me, who has always been much better at writing action and dialogue and plot than at description. If you’re one of those people who always has to pare down your writing, then this may not be for you.

You can tell right off the bat that McClanahan is a poet. I’m not overly fond of much poetry, but to read a writing book from the perspective of a poet was immensely helpful in taking me outside of my usual habits and prejudices so that I could actually learn how to be a better writer. McClanahan is thorough in her analysis of descriptive writing, and for me that thoroughness was entirely necessary to drill into my head that I need. To. Write. More. Descriptively.

One of the best ideas that McClanahan hit on over and over was the idea of the «fictional dream.» When a reader comes upon your book or poem or essay, he is allowing himself to be overcome by this fictional dream. However, you need to maintain this dream through the detail and nuance of your writing — otherwise he may snap out of it, which nobody wants. As a go through to write the second draft of my current work in progress, I will certainly keep the idea of the «fictional dream» in my mind at all times.

Again, I highly recommend this book to any writers who, like me, struggle to really flesh out their worlds and characters. It can get repetitive at times, but it’s been well worth it for me.

Author 27 books6 followers

Rebecca McLanahan has produced a book that is both useful to writers and a great pleasure to read for its own sake. She manages this partly by her judicious selection of examples, but perhaps even more so by her graceful descriptions of her own writing techniques, subtly toned and coloured with touches of autobiography.

She gets the details right too. Consider, for example, this modest little paragraph:

‘Much of our writing energy is expended not in illuminating the deep mysteries of theme and symbol but in simply performing the physical tasks of the story, such as moving a character from the bed to the refrigerator. Or describing a small black button.’

She nails the writing task so well there. As writers, even when (or especially when) we know the things we do, we get a thrill to see them expressed so insightfully.

Reviewer David Williams has a regular writer’s blog http://writerinthenorth.blogspot.com

99 reviews10 followers

Absolutely stellar; I would recommend this to all writers of all genres looking to add that extra and necessary “something” to their works. McClanahan expertly imparts her wisdom on the beauty and vibrancy of description—or as she calls it, Word Painting.

- writing

Author 40 books7 followers

Overwhelming at first, but extremely practical by the time I finished. Slow reading if you do the exercises. Now to apply all I learned…

154 reviews58 followers

A decent book with a lot of good advice, but man can it be long-winded at times. It starts to drag about halfway through and entirely loses focus by the end, delving into territory that’s covered much better, and in greater detail, by other books.

Honestly, if this book were half as long it would’ve been twice as good, because the beginning is actually pretty great. I loved the section on metaphor, simile, and other figures of speech, for instance, but the absolute best thing I took away from this book is «the proper and special name of a thing» which is something McClanahan stole from Aristotle, though I do not begrudge her for it because she lays it out so perfectly and so clearly (and also because she flat-out admits that fact right away). It is the relatively simple and, one might think, obvious idea that naming something, properly, does more to implant the image of that thing in the reader’s mind than a paragraph of description would.

That concept, and phrase, which is almost like a mantra, just clicked with me in a way that so few things do, and I will never, ever forget it.

- writing-and-creativity

171 reviews

Inspiring, helpful, clear as well as encouraging poetic and sensory description, McClanahan’s own writing is never dull. The examples she uses are from books I was mostly unaware of, which was great. I could not put this down as it was so pleasurable to read, a lovely journey from one section to the next and I could’t wait to try the exercises or improvise them into my work before the day’s editing.

- novels poetry

40 reviews6 followers

Tough to get through but there are some gems in there if you want to improve your writing.

134 reviews54 followers

The book, valuable for writers who want to write more descriptively, is worth reading for the examples alone. Definitely new takeaways for me. My chief issues: 1) the author, at times, forced quotes about writing into arguments they weren’t well suited to; 2) I accidentally read the older edition, and so I can’t speak to whether the non-woke passages have since been revamped.

533 reviews30 followers

My fav quotes (not a review):

-Page 7 |

«the pneumatic wheeze as a bus rounds the corner, the rhythmic clackclackclack of a roller skater counting each sidewalk seam.»

-Page 7 |

«the world of the book I am reading has become, for the moment at least, more real than the world at my elbow. Books this good should carry a warning: Your quiche might burn, your child escape his playpen, the morning glory vine strangle your roses, and you’ll never know.»

-Page 10 |

«Theoretically speaking, description is one-third of the storytelling tripod. Exposition and narration are the other legs on which a story stands. Exposition supplies background information while narration supplies the story line, the telling of events, leaving description to paint the story’s word pictures.»

-Page 17 |

«Amazing grace, it appears, is bestowed not on the perpetually sighted but on those who «once were blind but now can see.» Just as youth is wasted on the young, eyes are wasted on those of us who see. Or think we see.»

-Page 26 |

«quiet attention or «looking with awe and wonder.» She says that if she looks long enough and hard enough at a painting—even one she doesn’t like at all—it begins to take on a life of its own and she is able to see why it’s considered a great work of art. I imagine what she’s seeing with her imaginative eye is something akin to Hopkins’s «inscape.»»

-Page 33 |

«If I’m a passenger, I record my images on paper; if I’m driving, I record them on cassette. The car is my floating studio, though the view passes more quickly than Monet’s view and is more tightly framed. If you want to engage your gliding eye, set up a floating studio or set yourself in motion while the world rushes by.»

-Page 34 |

«Man’s maturity, wrote Nietzsche, is «to regain the seriousness that he had as a child at play.»»

-Page 38 |

«Blow-by-blow descriptions of dreams are interesting only to the teller. If you don’t believe this, try recounting last night’s dream to your co-worker while you wait in line at the copy machine, and watch his eyes glaze over. Suddenly he glances at his watch, remembers a meeting he just has to attend, and is out of there—and just when you were getting to the good part, too.»

-Page 39 |

«For literary examples, read Theodore Roethke’s «Child on Top of a Greenhouse,» William Carlos Williams’s «Nantucket,» or James Wright’s «Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota.»»

-Page 48 |

«The short i is a bantamweight vowel, the lightest, most childlike sound in our language. A more weighty choice would have been a word like stone or root or nobody. Is there a vowel more heavy or sad than the long o?»

-Page 69 |

«For instance, instead of writing, «I feel a heavy guilt every time I go home,» you could write, «Guilt comes in the door with me, dragging its heavy suitcase.»»

-Page 72 |

«Smell is why real estate agents advise sellers to bake something—preferably bread or chocolate chip cookies—before a prospective buyer comes to call.»

-Page 82 |

«First, following Aristotle’s suggestion, she accurately names the objects of the story’s world: rattail comb, little teeth, bristles, strand, tiny nylon nails. Then she describes, patiently and precisely, the act itself. The hair isn’t merely brushed and combed; it is tugged, parted, scored, separated, nipped, untangled, lifted. The writer breaks one broad generic act into its specific and significant steps,»

-Page 83 |

«During the preliminary parting and scoring, the sentences are broken into short segments. Then, as the brushing continues and the narrator gives in to the sensual experience, the sentences grow longer, more leisurely, suggesting the rhythms of sex—which happens to be the subject of a subsequent section of Adams’s novel.»

-Page 85 |

«My favorite was plinkle, which the boy invented for a story about his sister plucking violin strings. When I questioned him about why he didn’t use pluck, he shook his head adamantly. «Pluck is too deep,» he said. «Hers is more like the way an angel would do it. You know, plinkle.»»

-Page 88 |

«What does a sun look like going down over the ocean? It’s like touching a rose after it has rained.»

-Page 89 |

«Freedom is like putting three strawberries in your mouth at a time, touching the wet coldness of it, looking at the redness, hearing the crisp wonder in the air. Tiffany, 3rd grade»

-Page 93 |

«Keep a sensory journal for a month, devoting each weekday to one of the five senses. For example, if you choose Monday as «scent day,» then every Monday during the month you’ll describe in detail three things you smelled that day. If Tuesday is «sound day,» describe in detail three sounds you heard that day.»

-Page 94 |

«Visualize the egg. Then ask yourself questions about it. Where is it? In a straw basket lined with dish towels? Beneath a broody hen? On the top branch of a tree? On the embroidered panel of a child’s Easter dress?»

-Page 95 |

«Describe a place or a person by mixing two or more smells—like my description of my college boyfriend, who smelled of motor oil, cigarettes and Dial soap.»

-Page 95 |

«Employ synesthesia. Describe an object, place, person or idea by using one sense to suggest another. What color is the silence in your bedroom? What is the shape of your grandmother’s laughter? What smell emanates from fear?»

-Page 96 |

«Reality is a cliche from which we escape by metaphor —Wallace Stevens, from Opus Posthumous»

-Page 99 |

«It derives from the Greek metaphora, which breaks into two parts: meta («over») and pherein («to carry»). Moving vans in Greece are often marked with the word Metaphora to suggest the transfer of items from one place to another.»

-Page 106

«In metonymy, we refer to something not by its own name but by something closely related to it. The President is «the White House.» «From birth to death» becomes «from cradle to grave.» And who’s watching the baby? Not a mother, but «the hand that rocks the cradle.»»

-Page 108

«Anna Karenina throws herself under the wheels of a train, Cinderella’s stepsister slices off her toes so her foot can fit into the slipper, and Hemingway’s Kino finds the pearl of great price.»

-Page 123

«Wideman’s description also passes the third test of «the proper and special naming of a thing.» It is musically appropriate. «Spiked,» «bristle,» and «clipped» appeal to our ear as well as to our eye. The repetition of «i» provides musical unity, while the harsh, brittle consonants reinforce the brusque treatment both the grass and the prisoners receive.»

-Page 124

«For instance, from the list above you might combine nibble and kites to form «kites nibble at the sky.» Blossom, sorrow and song might form «Sorrow blossoms into song.» Once the metaphorical connection is made, you can reword your metaphor: «Yellow kites take bites of the sky» or «Sorrow’s song is a blossom.»»

-Page 144

«Those of us who write for the page can travel to places a camera can never travel, the internal landscape and mindscape of our characters and ourselves.»

-Page 145

«Reading Kundera, I always feel I’m living inside the characters rather than watching them move, bodily, through the world.»

-Page 159

«It’s as if the forest is alive, wrapping itself around both speaker and reader. The two sentences that follow, on the other hand, are objectively reported, as if spoken by someone totally removed from the scene. The psychic distance between the two voices is staggering. Any shift in point of view—in visual perspective, psychic distance or a shift from the vantage point of one character to another—must be carefully executed.»

-Page 177

«Since a godlike narrator is capable of infinite knowledge, it seems natural that he would want to impart this knowledge to his readers. Exposition appeals more to the mind than to the senses;»

-Page 177

«Generally speaking, description shows; exposition tells.»

305 reviews17 followers

This is a fantastic read. McClanahan has created a readable, informative and practical guide to improving a writer’s descriptive power. I was attracted to the title and cover, «Word Painting» and a reproduction of Manet’s impressionist look at Monet and his wife on a boat. I had never connected writing to painting. While admitting that they are both a form of art, I was always too intimidated to consider painting, I can’t even draw a nice stick figure person. Anyway, as I started to read I realized that not only is the information in the book extremely well thought out, nicely organized and very practical, I noticed that her writing style uses all of her advice throughout the book. She is a poet so her prose feels very lyrical, but she also utilizes descriptive techniques she teaches.

McClanahan discusses point of view, physical and psychical distance, Aristotle’s ideas of active description, how to have your full work have plenty of description in the appropriate places (not in chunky blocks or just dropped in because you feel you need some description here), using all of our senses in describing, being a careful and obsessive observer, warnings about cliches, problems with tone and attitude and a great review of literary devices (theme, motif, atmosphere), and figurative language such as simile, metaphor, symbol, metonymy, etc.

Reading this list may make it seem as though her attention is scattered around the literary world, but it isn’t. Everything goes back to description. She also provides exercises at the back of each chapter. I read it straight through but I am keeping it as a reference guide.

Author 22 books134 followers

This book offers an in-depth study of how to write an effective description. And there’s no single way of accomplishing the task. Though the author provides some basic “rules” such as avoiding filter words and passive sentences, most of the book takes a deeper look at descriptive writing, including but not limited to, how point of view impacts description, the use of simile and metaphor, establishing tone, and how to write active versus static passages. Numerous examples from well-known books illustrate each descriptive technique.

This is not a quick read, but it is thorough, and a good “textbook” for the serious writer. At the end of each chapter are numbered suggestions for both broadening and pinpointing a writer’s observational skills and for practicing the techniques presented in the text. I read this as a kindle book, but with the advantage of hindsight, recommend the paperback version for writers intending to refer back to the text for ideas or practice at a later time.

153 reviews1 follower

There were a few really good tidbits, but you have to slog through so much abstract wordiness to get to them, nothing sticks.

I bought this book because «writing descriptively» is one my favorite aspects of writing. But the 260 pages of flowery theory were a chore to get through. Sometimes it seemed so abstract or off-topic that it went over my head, and sometimes it seemed so duh that I wonder if that was actually going over my head too.

As much as I love a creative comparison or original description, the over-enthusiasm in this book felt, to me, like the author had a list of all these clever metaphors that she had to use up somewhere, and a list of book passages to rave about, so she splattered them all together on a wall and called it a painting.

- nonfiction writing writing-wordcraft

45 reviews32 followers

When the student is ready, the master appears. I started this book several years ago but never got through it. Fast forward, I decided to start over on this about a month ago and I can say the wisdom imparted in this book is something that will stay with me for the remainder of life. It’s beautifully written for one, also it gives you all the tools and techniques you need to start writing more thoughtfully, lovingly and descriptively.

- craft-of-writing

Author 100 books2,182 followers

This just took too long to say things, and when she did it was things that I already knew, which was probably why I was bored.

I do wish I’d read this a year ago, but the things in this book are the things that my editors have beat into my head.

I do think new writers would learn a lot from this book, but they would need to be patient with long-winded discussions.

- research-for-writing

24 reviews

This book is geared more toward the budding writer. Experienced authors won’t find anything new here. On a side note… the fact this author chose passages using the N word is unacceptable. I also noticed the author has a major problem with “fat” people as she uses the term or passage examples repeatedly. Same goes for sex. Her own “word painting” told a tale of a woman with many prejudices.

106 reviews9 followers

‘Like painters, writers are the receptors of sensations from the real world and the world of the imagination, and effective description demands that we sharpen our instruments of perception.‘

Rebecca McClanahan is the author of ten books — ranging across poetry, fiction, memoir and non-fiction — and has won a list of prizes for her works. She is also an educator in creative writing, as an instructor at the MFA program in Queens University of Charlotte, North Carolina. She was approached by the editors of Writer’s Digest Books in 1998 to write a book on description. ‘Word Painting‘ is the resultant text.

Writing description is hard. Writing in my journal, I’m more at ease in the harvesting of self-reflection or the prognostication of speculation. But this is a narrow way to be in relationship with the world. The dimensions of people and the contours of the world are exciting, but my writing, although touching on events, never feels truly comfortable in their relaying (or at least, until I picked up this book). To keep a journal that records events does not necessarily require a descriptive oomph, as can be seen in David Sedaris’s ‘Theft by Finding: Diaries (1977–2002)‘. His entries are enjoyable, detailing his life in Chicago and New York, without the need for scintillating description. A contrast to this is Sylvia Plath’s Journals, who writes at such length per entry and with such density of imagery and description that one can only resign themselves to an exhalation and a nod of the head in respect for her ability. I would like to be somewhere in the middle. Mainly, I want to enjoy describing meeting up with friends, and sketching the ordinariness of the everyday. I want there to be a creative fulfillment to it and to be surprised by the outpouring of my scribbling pen. ‘Word Painting‘ and Natalie Goldberg’s excellent ‘Writing Down the Bones‘, have greatly helped in this wish.

What separates McClanahan’s book from other texts that I’ve read on writing is its focus on description, which the title ‘Word Painting‘ is a synonym for. This part of writing is mentioned in passing in Stephen King’s ‘On Writing‘, and is barely touched on deliberately in William Strunk’s classic, ‘The Elements of Style‘. Having a book then dedicated to this component is invaluable. The first five chapters offer a definition of description, visual description, the essential usage of the other senses and figurative language. For those interested, the chapters are:

‘Chapter One: What is Description?

Chapter Two: The Eye of the Beholder

Chapter Three: From Eye to Word: The Description

Chapter Four: The Nose and Mouth and Hand and Ear of the Beholder

Chapter 5: Figuratively Speaking: A «Perception of Resemblances»‘

Given my aim outlined above, I am at this stage less interested in the second half of the book. The author dedicates this to the makeup of writing fiction and components like POV, the development of characters, setting and plot. This part still offered excellent perspectives on writing fiction, which I haven’t found elsewhere. For completion, the chapters are:

‘Chapter Six: Bringing Characters to Life Through Description

Chapter Seven: The Eye of the Teller: How Point of View Affects Description

Chapter Eight: The Story Takes Its Place: Descriptions of Setting

Chapter Nine: Plot and Place: How Description Shapes the Narrative Line

Chapter Ten: The Big Picture‘

As there are so many different exercises that I enjoyed and employ in my own writing. I will list some of them below with a small comment:

If there is a payment for good description, it is attention. A scene does not reveal itself all at once:

‘Description begins in the beholder’s eye, and it requires attention. If we look closely enough at something and stay in that moment long enough, we may be granted new eyes. Or ears. On his album Noel, Paul Stookey (of Peter, Paul and Mary fame) discusses his process of writing songs: “Sometimes,” he says, “if you sit in one place long enough, you get used. You become the instrument for what it is that wants to be said.”‘

As an exercise in attention, McClanahan gives us an exercise in using our naked eye (which she distinguishes from the imaginative eye):

‘To train your naked eye to see more intently, try this exercise in observation. Choose an ordinary object in your home. It might be something you use every day—a comb, a blanket, a salad bowl. Or it might be an object that’s been around forever but is seldom used—your mother’s wedding pearls, a hammer hanging on a Peg-Board, the avocado-green fondue pot from your first marriage. Set a timer for ten minutes, and don’t move until the time is up. During these ten minutes, your only job is to study the object. Stare at it. Notice every detail—its color, its shape, each part that contributes to the whole.‘

The advice that has most altered my own writing is the so-called imaginative eye. McClanahan tells us that rather than view, say, a coffee shop only with our naked eye — whose contents could feasibly be jotted down by several observant onlookers — we must launch our imagination to unlock more of the scene. She writes that this is achieved by engaging in associative thinking and seizing the bodies of memories. Additionally, she gives us another excellent activity that inhibits the tendency to see only what is in front of us:

‘After you’ve described the object’s qualities in concrete, sensory terms, you may wish to explore qualities only your imaginative eye can see. During your ten minutes of observation, did your mind wander? Did the object remind you of something else? Did you recall a memory associated with the object? Meditation often takes us into reverie, memory, digression, and even dreamlike states.‘

‘After studying a photograph, describe it as precisely as possible, using concrete and specific detail to show what your naked eye sees. Then engage your imaginative eye. Employ negative space, describing what you can’t see. What might lie outside the borders of the image? Who do you

imagine took the photo? Who or what is missing from the scene? What happened right before the photograph was snapped, or right after?‘

‘Another focusing activity is the “third eye” exercise I learned from Kenneth Koch’s Wishes, Lies, and Dreams. At first I used the exercise only with children in my poetry-in-the-schools work, but I discovered that the third eye concept works equally well for adults. Imagine that you have a third eye in the middle of your head, an eye that sees only what your other two eyes cannot see. Your third eye can see into any dimension of time and space, penetrating unseen mysteries. It possesses unlimited power. Well, almost unlimited. Remember, it can’t see what the naked eye sees. The only way to engage your third eye is to refuse to use images perceived through the naked eye. Sometimes the best way to describe our world is with our eyes closed. Daily life clouds our sight and our insight, especially when we spend time before televisions and various computer devices, where the visual world is frantic and fragmented, breaking into images lasting only seconds. Overwhelmed by visual stimuli, we can take in no more. The world has become a blur, each color and shape vying for our attention. Our naked eye becomes so filled that our inner eye refuses to see.‘

Another very practical exercise is to change visual POV in a scene. Rather than look at the layout of the coffee shop from one’s POV, look at it from the POV of the steaming mug or from the row of delectable cakes that sit next to the till:

‘Change your visual point of view. Stare at the same scene from several different focal points—lying flat on your back and looking up, peering through a peephole, looking down from a mountain, airplane, or diving board. Or frame an ordinary scene in new ways. Look through a window. Roll a sheet of paper into a tube and study the scene through a new lens. Distort a realistic view by looking through prisms, kaleidoscopes, or 3-D glasses. Then describe the scene through the lens of each eyepiece.

Deconstruct a ‘whole’ into its parts. We tend to see people or objects as unitary things but McClanahan encourages us to break that tendency:

‘One way to focus on details is to describe the various parts that make up the whole. A tangerine, for instance, consists of rind, juice, seeds, fruit, pulp, grainy membranes, stem, blossoms, and leaves. Describing each of these parts will force you to notice details you might otherwise overlook, what Chekhov called the “little particulars.”‘

Following an excerpt from Jane Brox’s essay, ‘Bread‘, McLanahan emphasises the need to properly name things and use strong verbs. One only needs to read Sylvia Plath’s collection of ‘Ariel‘ to see that someone as gifted as she repeatedly employ strong verbs and the specific names of objects:

‘More basic even than Brox’s strong verbs and sensory detail is her use of concrete, specific nouns. By naming the items of the baker’s world accurately and precisely, providing what Aristotle called “the proper and special name of a thing,” she invites us into the literary dream: flour, dough, enamel scale, disk, oven towels, muslin, olive, fresh cheese, slice of lamb. Each noun anchors us, keeping us firmly planted in the world being described.‘

On the chapter on figurative language, McClanahan gives us two exercises which allows us to make more metaphorical leaps and personify the abstract:

‘The object of the exercise is to trick your mind into making metaphorical leaps. Once you’ve filled your word basket, select at random four or five cards, spread them out on your desk, and combine two or more to form a simile, metaphor, or other figure of speech. For instance, from the list above you might combine nibble and kites to form “kites nibble at the sky.” Blossom, sorrow, and song might form “Sorrow blossoms into song.” Once the metaphorical connection is made, you can reword your metaphor: “Yellow kites take bites of the sky” or “Sorrow’s song is a blossom.”‘

‘Write a description of a natural object, idea, or emotion using personification or animism. Again, verbs are natural entries into both figures of speech. If you’re animating greed, for instance, ask yourself how greed moves or acts. Does it grab, clutch, or seize? Does it devour? The verbs might be enough to suggest personification or animism, or you can allow the verbs to lead you further in the writing process. If greed grabs, perhaps it has tentacles. If it devours, it might have a mouth. What kind of mouth? Using paradox, write a description of one of your characters. You can apply the paradox to a physical description of your character or to your character’s motives or emotions. In either case, choose two qualities that seem to be contradictory; then place them side by side. For instance, you might write that Eloise’s face was “scarred and beautiful” or “beautifully scarred.”‘

Lastly, McLanahan gives an excellent metaphor for why we can’t rely solely on the visual sense, and the importance of the other four:

‘Yet to ignore the other four senses in your writing is comparable to sitting in a gourmet restaurant wearing earplugs, work gloves, and a surgical mask over your nose and mouth. Sure, you can still read the menu. You can even enjoy the artist’s palette, the purple radicchio curled on top of the mixed greens. You can hold your wineglass to the light and admire its fluted stem. But you can’t hear the clink when you raise the glass for a toast. Or the sibilant intimacies from the couple in the next booth. And what about the hot, crusty roll the waiter just placed with a tong on your bread plate? It looks hot, it looks crusty, but how will you know unless you pick it up with your bare hands, feel its weight and shellacked surface, break it open, and feel the steam escaping from the soft center? You swirl the butter knife in the white crock, spread a smear of herb-speckled butter on the bread, lift it to your mouth. Were you not wearing a mask, you might detect the scent of rosemary even before the bread touches your lips.‘

I had been longing after a book on how to write description, and McClanahan’s surpassed my expectations. In my own writing, I wanted to be surprised more often, to gawk at unplanned directions or word choices that can emerge from the practice. This book has given me the tools to do that. A big thank you to the author for accepting that request all those years ago!

- 2021 writing

435 reviews9 followers

As a writer of fantasy, it can be easy to turn one’s nose up at literary fiction and, by extension, writing books that focus on literary fiction (McClanahan does include some passing references to sci-fi/fantasy and historical fiction, but it’s clear this is far outside her area of expertise). However, learning to write vivid, precise descriptions of people, places, and things can help set good fantasy apart from the merely mediocre, and thus writers of genre fiction can certainly benefit from opening this book. Some of the writing exercises have already proved useful.

One thing I particularly liked about Word Painting was that McClanahan fills her book with examples of authors who write well. I feel that it is entertaining, but also all too easy, to fill one’s ‘how-to-write’ book with examples of how NOT to write. While it is fun to laugh at the mistakes and foibles of beginning writers, it doesn’t teach you how to do it better. But McClanahan has chosen genuinely good examples of the points she wants to make, and readers and writers alike benefit from her thoughtful analysis.

Author 4 books12 followers

This book was a pleasure to read. Not only was it informative, it was well written. Although aimed more towards the literary, there is no reason why the well structured advice cannot be applied to genre fiction. In fact, genre fiction is probably where it is most needed. How many times have we read a good thriller or crime novel that keeps us turning the page because of intrigue or action, only to feel detached from the characters, or get that icky feeling when the emotion of a scene jars with the setting or tone? Then the novel comes across as unpolished even though it might be technically error free. This book goes beyond the nuts and bolts of writing, and for some, will open up a world of true creation and inspiration. It shows why good writing is a craft. I highly recommend it to anyone who enjoys writing, whether they intend to publish or not. There are multitudes of examples of the topics discussed and numerous writing exercises to help a writer develop.

34 reviews2 followers

If you read one book on writing, this should be it!

Word Painting goes beyond just «painting» a scene for your readers using adjectives. The author goes into great detail of how to use language itself to demonstrate to readers your theme, setting, atmosphere, everything a good story will need. The book even delves into how to use the art of what remains unsaid, the tool of silence, in writing to convey a description.

Bring a highlighter and your journal along while reading this book. Word Painting is not just a «how to write» book; it’s also an inspirational manual as well. If you’re a writer, you’ll itch to try out some of the techniques in your own style. Furthermore, there are plenty of opportunities to flex your writing muscles with great exercises at the end of each chapter. I can’t wait to do some of them for myself.

Overall, a great book that teaches how to use language in an artful way. If you’re a writer, I recommend this book ten times over.

- owned writing-art

376 reviews10 followers

Without a doubt, Word Painting is worth reading if you want to continue working on your descriptive writing techniques and development of Setting. There is a lot of useful information and the exercises are well thought out and helpful. McClanahan is an enjoyable author to read and uses a lot of personal stories to create analogous relationships to writing.

The book still has problems. It rambles, structurally at times it is incoherent, and the analysis of som writing could be better. Since this is a book on writing it becomes a big deal. Is it worth the read? Sure. But don’t feel bad flipping through areas that feel mundane (for me the last chapter was almost pointless, but that may also just be me)

187 reviews7 followers

It has taken me three tries to finally finish this book.

The advice is great. It is obvious from the start (with the description of apples) that the author knows her stuff. But as the book progresses, it becomes more and more difficult to keep engaged with the words.

The first half is absolutely useful. I learned a lot from it.

The second half… not so much. The author starts going on tangents and giving abstract explanations instead of the precise simple ones she was giving at the beginning.

Not a bad book, comparable to Description by Monica Wood, although I liked that one better only because it kept me reading without needing three tries to finish it.

- 2018 books-on-writing non-fiction

27 reviews1 follower

Great advice. The author sounds like a literary author from her style, seems to write «literary type things» and often quotes literary type authors (like the total snob Gardner blech) but she is not at all rude about genre fiction when it is mentioned. Basically, she offers a lot of good advice for if you want to have the richer, deeper descriptions that are found in literary works more often than in genre fiction, but doesn’t put down genre writers. It is really refreshing to see this, and I’m glad for it, being a genre writer who enjoys rich description

- writing

58 reviews

This is a good book about writing, particularly fiction writing.

Author of the book details the important challenges one feel in writing like description, role of five senses, using the right word, influence of author’s point of view.

This book tries to point out all the challenges one feels subconsciously while writing.

Though too much examples are derailing the concentration. One thing I dislike about books is the exercise, and this book has at the and of each chapter.

At the end of the book, author placed a very good list of book references categorized into Eye, Word, Story

Author 29 books85 followers

This was an excellent read. For those looking to improve the descriptive quality of their writing—both fiction and non-fiction—this is a must read. I initially read through it for a Creative Writing class, but I will definitely be revisiting this writing guide. The book contains many useful tips as well as helpful exercises to practice what you have learned in each chapter. It’s worth every penny spent on it!

- favorites owned writing-related

24 reviews

This book is geared more toward the budding writer. Experienced authors won’t find anything new here. On a side note… the fact this author chose passages using the N word is unacceptable. I also noticed the author has a major problem with “fat” people as she uses the term or passage examples repeatedly. Same goes for sex. Her own “word painting” told a tale of a woman with many prejudices.

Author 28 books233 followers

Best book about writing description. Get it!

Author 11 books59 followers

Interesting look at writing via descriptions. I’ll use the suggestions to bring freshness into writing.

Дорогой друг! Эта статья рассказывает о том, как описать картину на английском языке, а вот где можно научиться описывать картинку или фотографию.!

Describe a painting according to the plan:

- the subject of a painting (what is depicted in it)

- the composition (how space is arranged) and the colours

- the details

- the impression made by the picture

USE THE TOPICAL VOCABULARY:

1. To begin with, you should say that the painting belongs to a particular genre. It can be

- the portrait

- the landscape (seascape, townscape)

- the still life

- the genre scene

- the historical/ mythological painting

To begin with, this painting is a portrait which belongs to the brush of (…. the name of the painter)

1.1. If you remember some information about the painter, say it then.

This artist lived in the ……century and worked in the style known as Classicism, Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism, Surrealism, Cubism, Expressionism, Abstract Art.

1.2. Give your opinion about the painting. Use adjectives:

- lifelike = true to life

- dreamlike = work of imagination

- confusing

- colourful

- romantic

- lyrical

- powerful

- outstanding

- heart-breaking

- impressive

To my mind, it is a … picture, which shows (….say what you see)

2. Mention the colours and the composition

2.1. Colours can be:

- warm/ cold colours

- bold colours

- oppressive colours

- bright colours

- deep colours

- light colours

- soft and delicate colours

The picture is painted in …… colours. These colours contrast very well.

The dominating colours are ….

The colours contrast with each other.

2.2. Mention the composition/ the space:

The space of the picture is symmetrically/ asymmetrically divided.

2.3. Try to describe what you can see in general

- In the centre/middle of the painting we can see a ….

- In the foreground there is a….

- In the background there are….

- In the far distance we can make out the outline of a…

- On the left/ right stands/ sits…

Use we can use the following structures in turn:

there is/there are/ there stands/ sits/ lies/

Use participle clauses:

a woman wearing a white dress

a man dressed as a monk

3. Give some details

- At first glance, it looks strange/ confusing/ depressing/ …

- But if you look closely, you can see…

- It looks like ….

- The artists managed to capture the sitter’s impression/ the atmosphere of a…../ the mood of the moment, etc.

3.1. Make guesses about the situation:

They might be talking about…

She may have just woken up…

It looks as if …

4. In the end, give your impression. Use the words and phrases:

- Well, I feel that I am unable to put into words what I feel looking at the painting.

- To my mind, it is a masterpiece that could stand the test of time.

- Well, it seems to me that I couldn’t put into words the impression made on me by this painting.

- I feel extremely impressed by this painting.

- It is brilliant, amazing. It is a real masterpiece by (….. the painter).

The Task

Describe the painting by Josepf Turner and send it to [email protected]

The best descriptions will be published on the website. Good luck!

Страница 42 из 167

Ответы к странице 49

3d. Vocabulary & Speaking — Словарь и Разговор

4A. Read the box. What are the equivalents in your language? — Прочитайте текст в рамке. Есть ли эквиваленты этим выражениям на вашем языке?

must/can’t + infinitive without to = we are sure about sth — конструкция must/can’t + инфинитив без частицы to = мы уверены в чем-то;

may + infinitive without to = we aren’t sure about sth — конструкция may + инфинитив без частицы to = мы не уверены в чем-то.

Ответ:

1. This picture must be very old. (I’m sure it’s very old.) — Эта картина, должно быть, очень старая. (Я уверен, что она очень старая).

2. It can’t be an original. (I’m sure it isn’t an original.) — Не может быть, чтобы это был подлинник. (Я уверен, что это не подлинник).

3. This picture may be expensive. (I’m not sure if it’s expensive; it’s possible.) — Эта картина, возможно, дорогая. (Я не уверен, что она дорогая, но это возможно).

4B. Look at the painting and find the correct word in each sentence. — Посмотрите на картину и найдите корректное слово для каждого предложения.

1. The painting may/can’t be oil on canvas. — Картина, возможно, написана маслом на холсте.

2. The painting must/can’t be quite old. — Картина, должно быть, довольно старая.

3. The room may/must be the kitchen. — Изображенная комната, должно быть, кухня.

4. The woman may/must be married. — Женщина, возможно, замужем.

5. She must/can’t be rich. — Она (женщина) не может быть богатой.

6. She may/must be making breakfast. — Она, возможно, готовит завтрак.

Describing Paintings — Описание картин

When describing a painting, describe it as fully as possible, as if describing it to someone who can’t see it. You should mention the style, colours, subject, location, season/weather, etc. as well as describe what is in the foreground/background.

Когда вы описываете картину, опишите ее как можно более полно, так, как если бы ее описывали кому-то, кто не может ее увидеть. Вы должны отметить стиль, цвета, объекты, локацию, время года/погоду, а также опишите, что изображено на переднем и на заднем фоне.

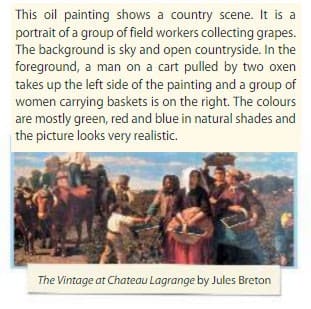

5. Look at the painting and read the description. Is the description detailed? What is mentioned about: the people? the place? the colours? the style? — Посмотрите на картину и прочитайте описание. Это описание сделано детально? Что сказано о: людях? месте? цветах? стиле?

Эта картина, нарисованная маслом (масляными красками), показывает сцену из деревенской жизни. На картине изображена группа работников, собирающих урожай. На заднем фоне показано небо и открытые просторы сельской местности. На переднем плане у левого края картины мы видим мужчину в повозке, запряженной двумя быками, а справа — группу женщин, несущих корзинки. Цветовая гамма преимущественно зеленая, красная и голубая естественных оттенков. Картина смотрится очень реалистично.

Возможный ответ:

The description is quite detailed. The people are a group of field workers collecting grapes. «There is a man on a cart on the left of the painting and a group of women carrying baskets on the right». We can add we can see not one but two men on a cart and not only women with baskets full of grapes but a boy helping them as well. «The place is in the open countryside». We can add that it’s not only the countryside, but it’s also a vineyard near the Chateau Lagrange. The colours are natural shades of green, red and blue. The picture is realistic.

Описание довольно подробное. Люди — это группа работников, собирающих виноград. «Мужчина на повозке, изображенный на картине слева и группа женщин с корзинами справа». Мы можем добавить, что мы видим не одного, а двух мужчин на повозке и не только женщин с корзинами, полными винограда, но и мальчика, помогающего им. «Это место в открытой сельской местности». Мы можем добавить, что это не только сельская местность, но и виноградник рядом с замком Лагранж. Цвета с естественными оттенками зеленого, красного и синего. Картина реалистична.

6. Describe this painting as fully as possible. — Опишите картину настолько детально, как только возможно.

Возможный ответ: Чтобы детально описать картину «Прогулка воскресной школы» художника Альберта Анкера, мы нашли ее в хорошем качестве и большем разрешении.

На этой картине швейцарского художника мы видим изображение сцены из деревенской жизни. Сейчас воскресенье. Уроки в воскресной школе закончились, класс вместе с учителем вышел на прогулку. На переднем плане мы видим более двух десятков маленьких детей примерно 7-10 лет, одетых в простую, но красочную крестьянскую одежду. Дети одеты по-разному: кто-то в обуви, кто-то нет, кто-то с головным убором, кто-то без. Видимо, деревня небольшая, поскольку дети разного возраста учатся в одном классе. Группу детей ведет учительница в строгом черном платье. Она держит в руках желтую шляпку. Дети идут нестройными рядами, не торопясь. Вероятно, они ощущают радость. Босоногий мальчик идет задом наперед и пританцовывает, и девочка перед ним тоже танцует. У нескольких девочек в руках мы видим букеты из полевых цветов. На заднем плане мы видим деревенские дома и поле. Художник изобразил ясное голубое небо с несколькими белыми облаками. Картина получилась очень яркой, с большим разнообразием цветов. Мы можем увидеть богатые и сочные красные, синие, зеленые, черные, белые и коричневые цвета. Картина написана в реалистичном стиле.

7. Listen to two friends trying to decide where to go on Saturday afternoon. Where do they decide to go? — Послушайте двух друзей, пытающихся решить, куда пойти субботним днем. Куда они решили пойти?

A: Let’s do something interesting this Saturday afternoon. — Давай займемся чем-нибудь интересным в эту субботу.

B: That’s a great idea. What do you suggest? — Хорошая идея. Что ты предлагаешь?

A: Well, how about going to the art exhibition at the museum since we both like art. Also, it’s good to have a bit of culture in our lives every now and then. — Ну, как насчет того, чтобы посетить художественную выставку в музее, раз уж мы оба любим искусство. Было бы неплохо привносить немного культуры в нашу жизнь время от времени.

B: Yes, you’re right, but I don’t really want to do that today. Why don’t we go to the film festival that I saw advertised at the Odeon? — Да, ты права, но я совсем не хочу делать это в тот день. Почему бы нам не сходить на кинофестиваль, который как рекламировали, пройдет в Одеоне?

A: Hmm. No, I don’t think so. — Хм. Нет, не думаю.

B: Why not? — Почему нет?

A: Because I don’t really feel like watching a film. We could go and see a dance performance. — Потому что я совсем не хочу смотреть кино. Мы могли бы сходить и посмотреть на танцевальное шоу.

B: Well, only if it’s a modern dance performance like hip hop. — Хорошо, если только это современное танцевальное шоу типа хип-хопа.

A: No, it’s a ballroom. — Нет, это балльные танцы.

B: In that case, certainly not. Why don’t we go and see a play then? Watching a play is cultural! There are lots of great plays on at the moment. — В таком случае, однозначно нет. Почему бы нам тогда не пойти и не посмотреть пьесу. Это же так культурно! Сейчас идет так много классных пьес.

A: All right. That’s a good idea. — Ладно. Это хорошая идея.

Ответ:

Friends decided to go and see a play. — Друзья решили пойти и посмотреть пьесу.

8. You are discussing what arts event your class should organise to raise money for charity. These are your options: — Вы обсуждаете какое культурное событие должен организовать ваш класс, чтобы собрать деньги на благотворительность. Вот несколько вариантов.

a photographic exhibition — фотовыставка

a demonstration by a well-known local artist — представление хорошо известного местного артиста

a classical music concert — концерт классической музыки

a painting competition — конкурс художников

Act out your dialogue. You can use the audioscript for Ex.7 as a model. Make sure you discuss all the options befor deciding on one. — Разыграйте ваш диалог. Вы можете использовать расшифровку аудиозаписи из упражнения 7 в качестве модели. Убедитесь, что вы обсудили все варианты, прежде чем определиться с одним.

Возможный вариант диалога:

A: We have to raise money for charity so we have five minutes to decide what art event our class should organise. Any ideas? — Мы должны собрать деньги на благотворительность, так что у нас есть пять минут, чтобы решить, какое художественное мероприятие следует организовать нашему классу. Есть идеи?

B: Why do we talk about an art event? Let’s organise sports action instead. — Почему мы говорим о художественном мероприятии? Давайте вместо этого проведем спортивную акцию.

A: No sports events! Visitors of sports actions usually don’t have enough money to donate to charity. That’s why we talk about the art event. Only art can attract rich people, I think. What do you think about a photographic exhibition? — Никаких спортивных мероприятий! Посетителям спортивных мероприятий обычно не хватает денег, чтобы жертвовать на благотворительность. Вот почему мы говорим о художественном мероприятии. Думаю, только искусство может привлечь богатых людей. Что ты думаете о выставке фотографий?

B: Well done! Are you kidding? You’ll have five or six visitors a day who are real art photo connoisseurs. — Ага, отлично! Ты шутишь? У тебя будет по пять или шесть посетителей в день, которые действительно ценят искусство фотографии.

A: Probably you’re right. What about painting competition? — Возможно, ты прав. А как же конкурс живописи?

B: Between two evils it’s not worth choosing. — Хрен редьки не слаще.

A: A classical music concert must be very attractive to deep pockets… — Концерт классической музыки должен быть очень привлекательным для толстосумов…

B: You’d better kill me here and now or I’ll be bored to death! We could think about modern music performance? — Лучше убей меня здесь и сейчас, или я помру от скуки! Мы могли бы подумать о представлении с современной музыкой?

A: One more «Gangnam Style» party? Certainly not. We won’t be able to rise money if we organise an event for white trashes or K-pop children. — Еще одна вечеринка в стиле Гангнам? Однозначно, нет. Мы не сможем собрать деньги, если организуем мероприятие для гопников или Кей-поп детишек.

B: I didn’t mean like this. I know one local violin trio band. They play beautiful classical music in a modern style. I can organise a live audition especially for you. — Я не это имел в виду. Я знаю одну местную группу — скрипичное трио. Они играют прекрасную классическую музыку в современном стиле. Я могу организовать прослушивание специально для тебя.

A: Perfect. I agree. — Отлично. Я согласен.

Painting is an art form that allows for a great deal of creativity and self-expression. When creating a painting, an artist has the opportunity to use a variety of colors, textures, and brushstrokes to create a work of art that is truly unique.

There are many different adjectives that can be used to describe a painting. Some of these adjectives are listed below

1. Abstract

2. Atmospheric

3. Bold

4. Bright

5. Captivating

6. Colorful

7. Creative

8. Delicate

9. Dramatic

10. Eclectic

11. Elegant

12. Expressive

13. Fascinating

14. Fluid

>>> Read Also: ” Adjectives For Culture ”

15. Focused

16. Intricate

17. Layered

18. Luminous

19. Majestic

20. Opaque

21. Organic

22. Original

23. Passionate

24. Powerful

25. Precise

26. Radiant

27. Reflective

28. Relaxing

29. Rollercoaster

30. Serene

31. Stunning

32. Subtle

33. Therapeutic

34. Vibrant

35. Whimsical

36. Wild

37. Zesty

Negative Adjectives for Painting

A few negative adjectives that could be used to describe a painting include: dull, uninspired, bland, and lifeless.

Positive Adjectives for Painting:

A few positive adjectives that could be used to describe a painting include: beautiful, creative, expressive, and stunning.

Derived adjectives for Painting:

A few derived adjectives for painting include: painterly, painted, and paintable.

Two adjectives for Painting:

Some possible adjectives for painting include creative and expressive.

>>> Read More: “Adjectives for Sight “

FAQs

Describing painting with examples

The painting is a beautiful, fluid work of art with bold strokes of blue and green. The colors are very creative and original, and the overall effect is stunning. The artist has used a variety of techniques to create this masterpiece, including layering different colors to create a sense of depth and dimension.

How to Describe Paint Texture?

The texture of the paint can be described as smooth, rough, or somewhere in between. The brushstrokes may be light or heavy, and the paint may be applied in a variety of ways to create different effects.

How do you compliment a Painting?

A few possible compliments that could be given to a painting include: beautiful, creative, expressive, and stunning.

I am James Jani here, a frequent Linguist, English Enthusiast & a renowned Grammar teacher, would love you share with you about my learning experience. Here I share with my community, students & with everyone on the internet, my tips & tricks to learn adjectives fast.

Reader Interactions

Words to Describe Art

valentinrussanov/Getty Images

To talk about paintings, and art in general, you need the vocabulary to describe, analyze, and interpret what you’re seeing. Thinking of the right words becomes easier the more art terms you know, which is where this list comes in. The idea isn’t to sit and memorize it, but if you consult the word bank regularly, you’ll start to remember more and more terms.

The list is organized by topic. First, find the aspect of a painting you wish to talk about (the colors, for instance), and then see which words match or fit with what you’re thinking. Start by putting your thoughts into a simple sentence such as this: The [aspect] is [quality]. For example, The colors are vivid or The composition is horizontal. It’ll probably feel awkward at first, but with practice, you’ll find it gets easier and more natural, and you’ll eventually be able to produce more complicated sentences.

Color

Think about your overall impression of the colors used in the painting, how they look and feel, how the colors work together (or not), how they fit with the subject of the painting, and how the artist has mixed them (or not). Are there any specific colors or color palettes you can identify?

- Natural, clear, compatible, distinctive, lively, stimulating, subtle, sympathetic

- Artificial, clashing, depressing, discordant, garish, gaudy, jarring, unfriendly, violent

- Bright, brilliant, deep, earthy, harmonious, intense, rich, saturated, strong, vibrant, vivid

- Dull, flat, insipid, pale, mellow, muted, subdued, quiet, weak

- Cool, cold, warm, hot, light, dark

- Blended, broken, mixed, muddled, muddied, pure

- Complementary, contrasting, harmonious

Tone

Don’t forget to consider the tone or values of the colors, too, plus the way tone is used in the painting as a whole.

- Dark, light, mid (middle)

- Flat, uniform, unvarying, smooth, plain

- Varied, broken

- Constant, changing

- Graduated, contrasting

- Monochromatic

Composition

Look at how the elements in the painting are arranged, the underlying structure (shapes) and relationships between the different parts, and how your eye moves around the composition.

- Arrangement, layout, structure, position

- Landscape format, portrait format, square format, circular, triangular

- Horizontal, vertical, diagonal, angled

- Foreground, background, middle ground