By

Last updated:

January 30, 2022

Do You Know the Origins of English? 16 English Words with Cool Life Stories

What if we told you that there’s a way to learn multiple English words at the same time?

All you have to do is learn one little English word and—poof!—you now know two, three or ten new words. Wow!

No, it’s not magic. All you have to do is learn a word’s origin along with its definition.

The origin of a word is the language it originally came from. English has many words that originally came from other languages. Some have been changed over years, others have stayed pretty much the same. When you learn a word, you should learn where it came from too!

But how will this help you double or triple your English vocabulary learning?

Often, when a foreign word is adopted by English, it takes on many new forms in the English language. This one new English word is put together with other English words, and these combinations create many more new words. However, these combinations are all related to the original word! If you know the original word, you’ll understand all of the combinations.

The more origins and original meanings you learn, the more you’ll see these words used and reused in English.

Through just one additional step to the vocabulary learning process—learning word origins—you can improve your understanding of English as a whole. Now that’s magical.

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

English Is Always Growing

Last December, the Oxford English Dictionary added 500 new words and phrases to the dictionary. Not 500 words for the year—the English language gained 500 officially recognized words and phrases in just three months!

English is a living language. That means it’s always growing and changing. Many things influence the English language and its growth, but no matter how new or old a word is, you can probably trace it back to an original word or the moment when it was accepted into the language.

Whether the word is fleek (meaning “nice,” from 2003) or fleet (meaning a group of military ships, from the year 1200), most English words came from somewhere else.

Some words are borrowed from other languages and turn into English words with few or no changes, like the Italian words for pizza and zucchini. Other words are changed a lot more and become barely recognizable, like the Latin word pax which turned into peace in English.

No matter how different a word is from its origin, though, knowing where it came from can help you become a better English learner.

How Learning Word Origins Can Improve Your English

When you learn a new word, do you remember to learn its different forms and tenses as well? After all, knowing the word “to see” isn’t enough when you want to talk about something you saw last week. You’ll need to say “to see” in different forms and tenses, such as “I see,” “I saw,” “I’m going to see” and “you’ve seen.” You can apply the same idea to word origins.

When you learn the origin of a word, you might see it again in another word. When that happens, you might be able to get a basic understanding of the new word.

For example, look at these words:

Transport

Transgress

Transaction

Notice anything similar about them? They all have the word trans in them, which comes from the Latin word meaning “across.” Now even if you don’t know the full meaning of the words you can figure out that they deal with something going across.

Now look at the original meanings of the other parts of the words:

Port — To carry

So, it makes sense that to transport something means that you carry something across a space. For example, a bus might transport people from one city to another. A plane might transport people from one country to another.

Gress — To go

To transgress means that you cross a boundary, rule or law.

Action — To do

A transaction usually involves an exchange or trade of some kind. For example, when you give money to a cashier to buy a new shirt, this is a transaction.

You can probably figure out what the words mean from this information. See how much we knew before you even thought about opening a dictionary? It’s all thanks to knowing word origins!

Roots, Prefixes and Suffixes

English words are often made from root words, with prefixes and suffixes joined to them.

A prefix is added to the beginning of a word. The bi in bicycle is a prefix that means “two” (as in two wheels).

A suffix is added to the end of a word. The less in endless is a suffix that means “without” (which is why endless means “without an end”).

Once you remove all the prefixes and suffixes on a word, you’re left with its root, which is the part of the word that gives its main meaning. The words cycle and end in the above words are roots.

Different prefixes and suffixes are added to a root to change its meaning and create new words. For example, the root word hand can become unhand (to let go), handout (something you give for free) or even handsome (good looking).

All three words have different meanings, but they’re all related in one way or another to hand. The first two words seem related to hand, but how is handsome related to hand? A long time ago, the word used to mean “easy to handle” and then later became a term you use to show appreciation for someone.

Understanding roots and word origins like this will make it easier to understand new words, and even why they mean what they mean. The next time you see a word that has hand in it, you’ll be one step closer to understanding it before you even look it up.

Below are just 16 words. From these 16 words, you’ll learn the meanings of more than 30 other words! Once you know each word’s origin, you’ll begin to notice it in other words.

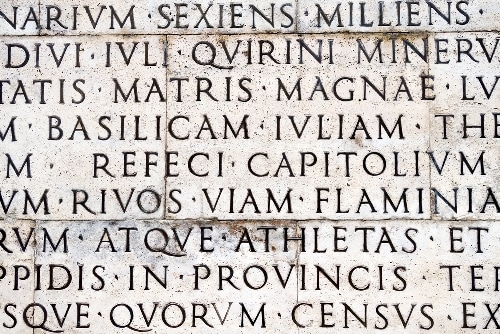

A majority of English word roots come from Latin and Greek. Even English words that come from other languages like French or German are sometimes originally Latin anyway—so they were Latin first, then became French or German and then they became English.

Many words on this list have gone through a few languages before getting to English, but in this post we’ll focus on just one main origin.

The “related words” sections give a sample of the other words you can learn using these origins, but there are many, many more out there. Most related words are broken down into their own origins, which are defined and then pointed out in parentheses (like these).

For example, if you see the words “together (sym),” you’ll know that the root sym means together. Simple!

And now, the words!

Greek

1. Phone

Meaning: A phone is a device that’s used to communicate with people from a distance (you might be using a phone to read this!).

Origin: The English word phone is actually short for telephone, which comes from the Greek words for sound (phon) and far away (tele).

Related words: Homophones are words that sound (phon) the same (homo) but are spelled differently, like hear and here. If you like hearing nice things you might enjoy a symphony, which is when many instruments play together (sym) to make a beautiful sound (phon)… usually.

2. Hyper

Meaning: Someone who is hyper is very energetic and lively.

Origin: Hyper actually a shortening of the word hyperactive, which combines the Greek word meaning “over, beyond” (hyper) and the Latin word for something that’s done (act).

Related words: When someone tells you they’re so hungry they could eat a horse, you know they’re just exaggerating by using a hyperbole—stretching the truth, like throwing (bole) something too far (hyper). No matter how exciting someone’s hyperbole is, try not to hyperventilate! That means to breathe or blow out air (ventilate) too much (hyper) in a way that makes you dizzy.

3. Sync

Meaning: When a few things happen at the same time or in the same way, they’re in sync. This word is a shortening of the word synchronize, but it’s used alone nowadays as a verb (your phone apps might even sync to make sure your files are up to date).

Origin: Sync comes from a Greek word that means to be together (sym or syn).

Related words: A synopsis is a summary of something like a movie or a play. It’s a way for everyone to see (opsis) the meaning together (syn). Synopsis and summary are actually synonyms, which are words that share the same (syn) meaning but have a different sound or name (onym).

Stay away from a play if the synopsis says the actors lip-sync. That means they move their lips (lip) together (syn) with the music without actually creating the sounds themselves.

4. Air

Meaning: Air is all around us. It’s the invisible gas that creates our atmosphere. Without air, we wouldn’t be able to breathe!

Origin: The word air has gone through a few languages before ending up in English, but it probably comes from the Greek word aer, which means to blow or breathe. You can actually find words that use both aer and air.

Related words: An airplane is a relatively flat object (plane) that flies in the air (air). Airplanes are aerodynamic, which means they use the air (aer) to power (dynamic) their flight. Don’t forget to look down when you’re in that plane, since aerial (of the air) views are pretty amazing!

Latin

5. Dense

Meaning: Something dense is packed tightly or very thick. For example, a fog can be so dense, or thick, that you can’t see much through it.

Origin: Dense comes from the Latin for “thick” (densus).

Related words: You can see condensation when evaporated water molecules join together (con) and becomes thick (dens) enough to form droplets. Density is the measure of how thickly packed (dens) something is, like people or things in one space.

6. Finish

Meaning: To finish something means to be done with it. In a few seconds you’ll be finished reading this sentence.

Origin: Finish comes from the Latin word finis which means “end.” In many words, this is shortened to fin.

Related words: You’ve probably defined a lot of vocabulary words in your English learning, which means you’ve looked up what the words mean. You could say that you’ve brought an end (both de and fin), to your lack of understanding! Don’t worry, there’s a finite number of words in English, which is a noun (ite) that means something that has a limit or end (fin). If English were infinite, or without (in) a limit, we would be learning it forever!

7. Form

Meaning: The form of something is its shape. As a verb, the word to form means to create something in a specific shape.

Origin: The word form comes from the Latin words for a mold (forma) and the Latin verb to form or to create (formare).

Related words: Many jobs and schools require people to wear a uniform, which is clothing that all looks the same or has one (uni) style (form). When places don’t have strict rules about what clothes to wear, they’re informal, or without (in) a specific shape (form).

8. Letter

Meaning: A letter is a symbol that represents a sound in a language, like a, b, c, or the rest of the alphabet. A letter is also a message you write and send to someone. Emails are digital letters!

Origin: In Latin, a letter was called a littera, and the lit and liter parts of this word appear in many English words that are related to letters.

Related words: If you’re reading this, you’re literate—you know how to read (liter). You probably read literature (books) and hopefully don’t take fiction too literally (seriously and exactly). All these words are forms of the stem liter, but their suffixes turn them into someone who reads (literate), something that exists (literature), and someone who does things to the letter (literally).

9. Part

Meaning: A part is a piece of a whole, something that isn’t complete. In verb form, the word to part means to divide or remove something.

Origin: This word comes from the Latin partire or partiri, which means to divide or share among others.

Related words: Somebody impartial has no (im) opinion about something (they take no part in the debate). You can be impartial about whether you live in a house or an apartment. An apartment is the result (ment) of dividing a building into smaller spaces (part). Wherever you live, make sure it’s safe—you wouldn’t want to put your family in jeopardy, which is a dangerous situation or, according to the original definition, an evenly divided (part) game (jeo).

10. Voice

Meaning: Your voice is the sound you use to speak. You can also voice, or state, an opinion.

Origin: The Latin word for voice is vox, and the word for “to call” is vocare. These two related words are the origin of a number of English words related to speech or voices. They usually include the root voc or vok.

Related words: An advocate is someone who calls (voc) others to help him (ate) support a cause or a person. Even someone who means well might end up provoking someone who doesn’t agree with them. To provoke someone means to call someone (vok) forward (pro) and challenge them in a way that usually makes them angry.

Old Norse

11. Loft

Meaning: A loft is a room right under the roof or very high up in a building. The loft in a house is usually used for storage, but building lofts are rented out as (usually smaller) living spaces.

Origin: The Old Norse word for air or sky was lopt, which is written as loft in English.

Related words: Something aloft is up in (a) the air (loft). If something is very tall, you would say it’s lofty, which is the adjective form of loft. In the same way, someone lofty has a very high (loft) opinion of themselves, which makes them act proud or snobbish.

French

12. Question

Meaning: Asking a question means trying to get information about something. Questions end in question marks (?).

Origin: Originally from Latin, English borrowed the Old French word question and never gave it back. The word means “to ask” or “to seek,” and it shows up in a number of ways in other words, from quire to quest. This one can be tough to spot since it switches between using the French and Latin versions of the word.

Related words: Some fantasy books have the main characters going on a quest, or a long and difficult search (quest) for something. Maybe you’re more interested in murder mystery books, which often have an inquest, or an official investigation (quest) into (in) someone’s suspicious death. If these types of books sound interesting, you can inquire, or ask (quest) about (in) them at your local library.

13. Peace

Meaning: Peace is a calm state of being. It means no wars or troubles. Peace is a wonderful thing!

Origin: The Latin pax and Old French pais both mean peace, and English words use both as prefixes and suffixes. Look for words with pac or peas in them (just not the kind of peas you eat. That’s a whole other word).

Related words: To pacify means to make (ify) someone calmer (pac). To calm someone, you can try to appease them, which means to (a) bring them peace (peas) by giving them what they want.

14. Liberty

Meaning: Liberty is the state of being free. The Statue of Liberty in New York is a symbol of freedom.

Origin: Another originally Latin word, liberty found its way into English through the Old French liberete, usually shortened to lib.

Related words: A liberator is a person (ator) who sets others free (lib) from a situation like slavery, jail or a bad leader. Becoming free means being open to changes, so it helps if you’re liberal—someone with a personality (al) that’s open to (lib) new ideas or ways of thinking.

Italian

15. Gusto

Meaning: Doing something with gusto means really enjoying it and being enthusiastic about it.

Origin: The Italian word gusto actually means taste, and comes from the Latin for taste, gustus.

Related words: You won’t do something with gusto if you find it disgusting. That’s the negative feeling you get about something you think is unpleasant—literally, without (dis) taste (gust).

Arabic

16. Check

Meaning: To check means to take a close look at something, or to make sure of something (verify it). For example, before you leave for work in the morning you might check that you have everything you need. Check can also be used as a verb that means to stop or slow something down.

Origin: The word check has an interesting history, moving from language to language and changing its meaning a little with each one. The word is originally from Persian and then Arabic, where it meant “king.” Over time, the word started being used in the game of chess and was defined as “to control.” Eventually the word’s meaning changed to what it is today. So much history in such a small word!

Related words: Leaving something unchecked means leaving something without (un) limits or control (check). If you leave weeds to grow unchecked in your yard, for example, they’ll take over and destroy your other plants. The word check on its own also refers to a piece of paper worth a certain amount of money (you write checks to pay bills). A raincheck used to be a ticket given to people attending outdoor events that had to be stopped because of rain. Today a raincheck is just a promise to do something another time.

The more roots and word origins you know, the easier it will become to learn new words.

Don’t stop learning here! Can you find words that use the related roots, too?

There are always new words to discover, and now you know exactly what to look for!

Download:

This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you

can take anywhere.

Click here to get a copy. (Download)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

According to surveys,[1][2] the percentage of modern English words derived from each language group are as follows:

| Latin | ≈29% |

| French | ≈29% |

| Germanic | ≈26% |

| Greek | ≈5% |

| Others | ≈10% |

The following are lists of words in the English language that are known as «loanwords» or «borrowings,» which are derived from other languages.

For Old English-derived words, see List of English words of Old English origin.

- English words of African origin

- List of English words of Afrikaans origin

- List of South African English regionalisms

- List of South African slang words

- List of English words from indigenous languages of the Americas

- List of English words of Arabic origin

- List of Arabic star names

- List of English words of Australian Aboriginal origin

- List of English words of Brittonic origin

- Lists of English words of Celtic origin

- List of English words of Chinese origin

- List of English words of Czech origin

- List of English words of Dravidian origin (Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu)

- List of English words of Dutch origin

- List of English words of Afrikaans origin

- List of South African slang words

- List of place names of Dutch origin

- Australian places with Dutch names

- List of English words of Etruscan origin

- List of English words of Finnish origin

- List of English words of French origin

- Glossary of ballet, mostly French words

- List of French expressions in English

- List of English words with dual French and Anglo-Saxon variations

- List of pseudo-French words adapted to English

- List of English Latinates of Germanic origin

- List of English words of Gaulish origin

- List of German expressions in English

- List of pseudo-German words adapted to English

- English words of Greek origin (a discussion rather than a list)

- List of Greek morphemes used in English

- List of English words of Hawaiian origin

- List of English words of Hebrew origin

- List of English words of Hindi or Urdu origin

- List of English words of Hungarian origin

- List of English words of Indian origin

- List of English words of Indonesian origin, including from Javanese, Malay (Sumatran) Sundanese, Papuan (West Papua), Balinese, Dayak and other local languages in Indonesia

- List of English words of Irish origin

- List of Irish words used in the English language

- List of English words of Italian origin

- List of Italian musical terms used in English

- List of English words of Japanese origin

- List of English words of Korean origin

- List of Latin words with English derivatives

- List of English words of Malay origin

- List of English words of Māori origin

- List of English words of Niger-Congo origin

- List of English words of Old Norse origin

- List of English words of Persian origin

- List of English words of Philippine origin

- List of English words of Polish origin

- List of English words of Polynesian origin

- List of English words of Portuguese origin

- List of English words of Romani origin

- List of English words of Romanian origin

- List of English words of Russian origin

- List of English words of Sami origin

- List of English words of Sanskrit origin

- List of English words of Scandinavian origin (incl. Danish, Norwegian)

- List of English words of Scots origin

- List of English words of Scottish Gaelic origin

- List of English words of Semitic origin

- List of English words of Spanish origin

- List of English words of Swedish origin

- List of English words of Turkic origin

- List of English words of Ukrainian origin

- List of English words of Welsh origin

- List of English words of Yiddish origin

- List of English words of Zulu origin

See also[edit]

- Anglicisation

- English terms with diacritical marks

- Inkhorn term

- Linguistic purism in English

- List of Germanic and Latinate equivalents in English

- List of Greek and Latin roots in English

- List of proposed etymologies of OK

- List of Latin legal terms

References[edit]

- ^ Finkenstaedt, Thomas; Dieter Wolff (1973). Ordered profusion; studies in dictionaries and the English lexicon. C. Winter. ISBN 3-533-02253-6.

- ^ Joseph M. Williams (1986) [1975]. Origins of the English Language. A social and linguistic history. Free Press. ISBN 0029344700.[page needed]

External links[edit]

- Ancient Egyptian Loan-Words in English

- List of etymologies of English words

Etymology – the study of word origins – is a fantastically interesting discipline that yields some incredible facts about where the hugely diverse array of words that make up the English language come from.

Whether you’re a native speaker or currently learning English, you’ll be amazed at some of the stories behind words you use every day. From tales of frenzied Viking warriors to a theatre-owner’s bet to get people using a made-up word, a little-thought-about history lies waiting to be discovered. Knowing more about the words we use makes studying English even more fun, so here are fourteen of our favourite word origins – and we’ve barely scratched the surface!

1. Dunce

The origins of this derogatory word for someone considered incapable of learning (the opposite of a “bright” student) are surprisingly old, dating to the time of one John Duns Scotus, who was born around 1266 and died in 1308. Scotus was a Scottish Franciscan philosopher and theologian whose works on metaphysics, theology, grammar and logic were so popular that they earned him the honour of a papal accolade. His followers became known as ‘Duns’. So how did this word come to be associated with academic ineptitude? Well, the Renaissance came along and poor Duns’ theories and methods were widely discredited by Protestant and Humanist scholars, while Duns’ supporters clung to his ideas; subsequently, the word “Dunsman” or “Dunce” (which arises from the way in which “Duns” was pronounced in Medieval times) was used in a derogatory fashion to describe those who continued to support outdated ideas. The word gradually became used in a more general sense to refer to someone considered slow-witted. Interestingly, though his name is now used disparagingly, Duns’ teaching is still held in high regard by the Catholic Church, and he was beatified as recently as 1993.

2. Quiz

The story behind the origins of the word “quiz” is so good that we really wish it was true – but it probably isn’t. Legend has it that a Dublin theatre-owner made a bet that he could introduce a new word into the English language within a day or two (the amount of time differs in different tellings of the story), and that the people of Dublin would make up the meaning of the word themselves. So he wrote the nonsense word “quiz” on some pieces of paper and got a gang of street urchins to write it on walls across Dublin. The next day everyone was talking about it, and it wasn’t long before it became incorporated into everyday language, meaning a sort of “test”, because this is what the people thought the mysterious word was supposed to be. According to the telling of the story recorded in Gleanings and Reminiscences by F.T. Porter (written in 1875), the events of this humorous tale unfolded in 1791, and this is where the story becomes less convincing. The word “quiz” is attested earlier than this date, used to refer to someone who is eccentric or odd (hence the word “quizzical”); it was also the name of a yo-yo-like toy popular in 1790. That said, it’s still difficult to find a compelling explanation for the origins of this word, so perhaps there is an element of truth in this excellent story after all.

3. Berserk

When someone “goes berserk”, they go into a frenzy, run amok, perhaps even destroying things. Picture someone going berserk and it’s not difficult to imagine the ancient Norse warriors to whom the word “berserker” originally referred. The word “berserk” conjured up the fury of these men and the untamed ferocity with which they fought, and it’s thought that the word came from two other Old Norse words, “bjorn”, meaning “bear” and “serkr”, meaning “coat”. An alternative explanation, now widely discredited, says that rather than “bjorn”, the first part of the word comes from “berr” meaning “bare” – that is, not wearing armour. Some have said that the “berserkers” were so uncontrollably ferocious due to being in an almost trance-like state, either by working themselves up into a frenzy before battle, or by ingesting hallucinogenic drugs. So, next time you use the expression “going berserk” to describe someone acting irrationally, remember those battle-crazed Vikings and be glad that you’re not on the receiving end of the wrath of a real “berserker”!

4. Nightmare

It sounds as though it refers to a female horse, but in fact the “mare” part of the word “nightmare” (a terrifying dream) comes from Germanic folklore, in which a “mare” is an evil female spirit or goblin that sits upon a sleeper’s chest, suffocating them and/or giving them bad dreams. The same Germanic word – “marōn” – gives rise to similar words in many Scandinavian and European languages. Interestingly, in Germanic folklore, it was believed that this “mare” did more than just terrorise human sleepers. It was thought that it rode horses in the night, leaving them sweaty and exhausted next day, and it even wreaked havoc with trees, twisting their branches.

5. Sandwich

The nation’s favourite lunchtime snack gets its name from the 4th Earl of Sandwich, John Montagu. The story goes that 250 years ago, the 18th-century aristocrat requested that his valet bring him beef served between two slices of bread. He was fond of eating this meal whilst playing card games, as it meant that his hands wouldn’t get greasy from the meat and thus spoil the cards. Observing him, Montagu’s friends began asking for “the same as Sandwich”, and so the sandwich was born. Though people did eat bread with foods such as cheese and meat before this, these meals were known as “bread and cheese” or “bread and meat”. The sandwich is now the ultimate convenience food.

6. Malaria

You wouldn’t have thought that a word we primarily associate with Africa would have originated in the slightly more forgiving climate of Rome. It comes from the medieval Italian words “mal” meaning “bad” and “aria” meaning “air” – so it literally means “bad air”. The term was used to describe the unpleasant air emanating from the marshland surrounding Rome, which was believed to cause the disease we now call malaria (and we now know that it’s the mosquitoes breeding in these conditions that cause the disease, rather than the air itself).

7. Quarantine

The word “quarantine” has its origins in the devastating plague, the so-called Black Death, which swept across Europe in the 14th century, wiping out around 30% of Europe’s population. It comes from the Venetian dialect form of the Italian words “quaranta giorni”, or “forty days”, in reference to the fact that, in an effort to halt the spread of the plague, ships were put into isolation on nearby islands for a forty-day period before those on board were allowed ashore. Originally – attested by a document from 1377 – this period was thirty days and was known as a “trentine”, but this was extended to forty days to allow more time for symptoms to develop. This practice was first implemented by the Venetians controlling the movement of ships into the city of Dubrovnik, which is now part of Croatia but was then under Venetian sovereignty. We now use the word “quarantine” to refer to the practice of restricting the movements, for a period of time, of people or animals who seem healthy, but who might have been exposed to a harmful disease that could spread to others.

8. Clue

Who knew that the word “clue” derives from Greek mythology? It comes from the word “clew”, meaning a ball of yarn. In Greek mythology, Ariadne gives Theseus a ball of yarn to help him find his way out of the Minotaur’s labyrinth. Because of this, the word “clew” came to mean something that points the way. Appropriately enough, Theseus unravelled the yarn behind him as he went into the maze, so that he could work his way back out in reverse. Thus the word “clew” can be understood in this context and in the context of a detective working his way backwards to solve a crime using “clues”. The word gained its modern-day spelling in the 15th century, a time when spelling was rather more fluid than it is today.

9. Hazard

Our word for danger or risk is thought to have its origins in 13th-century Arabic, in which the word “al-zahr” referred to the dice used in various gambling games. There was a big element of risk inherent in these games, not just from the gambling itself but from the danger of dishonest folk using weighted dice. Thus the connotations of peril associated with the word, which got back to Britain because the Crusaders learnt the dice games whilst on campaign in the Holy Land.

10. Groggy

We’ve all felt “groggy” at one time or another – lethargic, sluggish, perhaps through lack of sleep. It originated in the 18th century with a British man named Admiral Vernon, whose sailors gave him the nickname “Old Grog” on account of his cloak, which was made from a material called “grogram”, a weatherproof mixture of silk and wool. In 1740, he decreed that his sailors should be served their rum diluted with water, rather than neat. This was called “grog”, and the feeling experienced by sailors when they’d drunk too much of it was thus called “groggy”.

11. Palace

The word “palace” is another English word with origins in Rome. It comes from one of Rome’s famous ‘Seven Hills’, the Palatine, upon which the Emperor resided in what grew into a sprawling and opulent home. In Latin, the Palatine Hill was called the “Palatium”, and the word “Palatine” came to refer to the Emperor’s residence, rather than the actual hill. The word has reached us via Old French, in which the word “palais” referred to the Palatine Hill. You can see the word “Palatine” more easily in the form “palatial”, meaning palace-like in size.

12. Genuine

The word “genuine” comes from the Latin word “genuinus”, meaning “innate”, “native” or “natural”, itself derived, somewhat surprisingly, from the Latin word “genu”, meaning “knee”. This unlikely origin arises from a Roman custom in which a father would place a newborn child on his knee in order to acknowledge his paternity of the child. This practice also gave rise to an association with the word “genus”, meaning “race” or “birth”. In the 16th century the word “genuine” meant “natural” or “proper”, and these days we use it to mean “authentic”.

13. Ketchup

It’s hard to believe that this British and American staple started life in 17th-century China as a sauce of pickled fish and spices. Known in the Chinese Amoy dialect as kôe-chiap or kê-chiap, its popularity spread to what is now Singapore and Malaysia in the early 18th century, where it was encountered by British explorers. In Indonesian-Malaysian the sauce was called “kecap”, the pronunciation of which, “kay-chap”, explains where we got the word “ketchup”. It wasn’t until the 19th century that tomato ketchup was invented, however; people used to think that tomatoes were poisonous, and the sauce didn’t catch on in America until later that century. One couldn’t imagine chips or burgers without it now!

14. Ostracise

The word “ostracise” and the concept of democracy were both born in Ancient Greece, where the practice of a democratic vote extended to citizens voting to decide whether there were any dangerous individuals who should be banished (because they were becoming too powerful, thus posing a threat to democracy). Those who were eligible to vote exercised this privilege by writing their vote on a sherd of broken pottery – an “ostrakon”. If the vote came back in favour of banishing the individual, they were “ostracised” (from the Ancient Greek verb “ostrakizein”, meaning “to ostracise”). The word has nothing to do with ostriches, the flightless birds – similar though the words are!

As we said at the start of this article, this selection of fascinating word origins barely even scratches the surface of the endlessly interesting world of etymology. Whether you’re a seasoned English speaker or trying to learn this challenging language for the first time, you’re bound to find out some useful facts to help you memorise new words simply by exploring their origins. What remarkable word histories will you discover the next time you find out what a word really means?

Image credits: banner; Duns; berserker; sandwich; dice game; Rome; ketchup.

-

The etymological composition of ME.

-

The native and borrowed elements of the EV.

-

Classification of borrowings according to the language.

-

Etymological doublets.

-

International words.

Etymology

(from Greek etymon

«truth»

+ logos

«learning»)

is a branch

of linguistics that studies the origin and history of words tracing

them to

their earliest determinable source.

The following list provides a sample set of words that have been

incorporated into English:

French:

cuisine,

army, elite, saute, cul-de-sac, raffle.

Latin:

cup,

fork, pound, vice versa.

Greek:

polysemy,

synonymy, chemistry, physics, phenomenon.

Native

American languages: caucus,

pecan, raccoon, pow-wow.

Spanish:

junta,

siesta, cigar.

German:

rucksack,

hamburger, frankfurter, seminar.

Scandinavian

languages: law,

saga, ski, them, they, their.

Italian: piano, soprano, confetti, spaghetti, vendetta.

South

Asian languages: bungalow,

jungle, sandal, thug.

Yiddish:

goy,

knish, schmuck.

Dutch:

cruise,

curl, dock, leak, pump, scum, yacht.

Chinese:

mandarin,

tea, serge.

Japanese:

bonsai,

hara-kiri, kimono, tycoon, karate, judo.

English is

generally regarded as the richest of the world’s languages. It owes

its exceptionally

large vocabulary to its ability to borrow and absorb words from

outside. Atomic,

cybernetics, jeans, khaki, sputnik, perestroika are

just

a few of the many words that have come into use during XX century.

They

have been taken from Italian, Hindi, Greek and Russian.

«The

English

language», observed Ralph Waldo Emerson, «is the sea which

receives

tributaries from every region under heaven.» (в

презентацию)

The English

vocabulary has been enriched throughout its history by

borrowings from foreign languages. A

borrowing

(a

loan word) is a word

taken over from another language and modified in phonemic shape,

spelling, paradigm or meaning according to the standards of the

English language.

The process

of borrowing words from other languages has been going on for more

than 1,000 years. The fact that up

to 80 per cent of the English vocabulary consists of borrowed words

is due to the specific conditions of the English language

development.

When the Normans crossed over from France to

conquer England in 1066, most of the English people spoke Old

English, or Anglo-Saxon — a language of about 30,000 words. The

Normans spoke a language that was a mixture of Latin and French. It

took about three centuries for the languages to blend into one that

is the ancestor of the English spoken today. The

Normans bestowed on English words such us duchess,

city, mansion, and

palace. The

Anglo-Saxon gave English ring

and town.

Latin and Greek have been a

fruitful source of vocabulary since the 16th

century. The Latin word mini,

its converse maxi

and the Greek word micro

have become popular adjectives to

describe everything from bikes to fashion. Perhaps the most important

influence in terms of vocabulary comes from what are called Latinate

words,

that is, words that are originally Latin. Latinate words are common

in English: distinct,

describe, transport, evidence, animal, create, act, generation,

recollection, confluence, etc.

There are practically no limits to the kinds of

words that are borrowed. Words are employed as symbols for every part

of culture. When cultural elements are borrowed from one culture by

another, the words for such cultural features often accompany the

feature. Also, when a cultural feature of one society is like that of

another, the word of a foreign language may be used to designate this

feature in the borrowing society. In

English, a material culture word rouge

was

borrowed from French, a social culture word republic

from

Latin, and a religious culture word baptize

from

Greek.

Such words become completely absorbed into the

system, so that they are not recognized by speakers of the language

as foreign. Few people realize that garage

is borrowed from French, that thug

comes from Hindustani, and that tomato

is of Aztec origin.

However, some words and phrases have retained

their original

spelling, pronunciation and foreign identity, for example:

rendezvous,

coup, gourmet, detente (French);

status quo,

ego, curriculum vitae, bona fide (Latin);

patio,

macho (Spanish);

kindergarten,

blitz (German);

kowtow, tea

Chinese,);

incognito,

bravo (Italian).

We may distinguish different types of borrowing

from one foreign language by another:

(1) when the two languages

represent different social,

economic, and political units and

(2)

when the two languages are

spoken by those within the same social, economic, and political unit.

the

borrowing of linguistic forms by one language or dialect from another

when both occupy a single geographical or cultural community.

The

first of these types has been usually called «cultural

borrowing»

while the second type has been termed «intimate

borrowing«.

Another

principal type is between dialects of the same language. This is

called «dialect

borrowing»

(в

презентацию).

Sometimes the

idea of a word rather than the word is borrowed. When

we talk about life

science instead

of

biology, it

is a type of borrowing the

meaning of the Greek derivative, but not the actual morpheme. This

type of borrowing is rather extensive, particularly in scientific

vocabulary

and trade languages as, for example, in Pidgin English in the South

Pacific.

A

number of words in English have originated from the names of people:

boycott,

braille, hooligan, mentor, saxophone, watt. Quite

a few names

of types of clothing originate from the people who invented them:

bowler,

cardigan, Wellingtons, mackintosh. A

number of names of different

kinds of cloth originate from place names: angora,

denim, satin, tweed,

suede. A

number of other words in English come from place names:

bedlam,

spartan, gypsy.

There are

many words that have changed their meaning in English, e.g.

mind

originally

meant «memory», and this meaning survives in the

phrases «to keep in mind», «time out of mind»,

etc. The word brown

preserves

its old meaning of «gloomy» in the phrase «in a brown

study».

There are instances when a word acquires a meaning opposite to

its original one, e.g. nice

meant

«silly» some hundreds of years ago.

Thus, there

are two main problems connected with the vocabulary of a language:

(1) the

origin of

the words, (2) their

development

in the language.

The

etymological structure of the English vocabulary consists of the

native element (Indo-European and Germanic) and the borrowed

elements.

By

the

Native

Element we

understand words that are not borrowed from

other languages. A

native word is a word that belongs to the Old English word-stock. The

Native Element constitutes

only up to 20-25% of the English vocabulary.

Old English,

or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English

language. It was spoken from about a.d.

600

until about a.d.

1100,

and most of its words had been part of a still earlier form of the

language.

Many

of the common words of modern English, like home,

stone,

and

meat

are

native,

or Old English, words. Most of the irregular verbs

in English derive from Old English (speak,

swim, drive, ride, sing), as

do most of the English shorter numerals (two,

three, six, ten) and

most of

the pronouns (I,

you, we, who).

Many Old

English words can be traced back to Indo-European, a prehistoric

language that was the common ancestor of many languages.

Others came into Old English as it was becoming a separate language.

(a)

Indo-European

Element:

since English belongs to the Germanic branch

of the Indo-European group of languages, the oldest words in English

are of Indo-European origin. They form part of the basic word stock

of all Indo-European languages. There are several semantic groups:

-

words

expressing family relations: brother,

daughter, father, mother,

son; -

names

of parts of the human body: foot,

eye, ear, nose, tongue;

-

names

of trees, birds, animals: tree,

birch, cow, wolf, cat; -

names

expressing basic actions: to

come, to know, to sit, to work; -

words

expressing qualities: red,

quick, right, glad, sad; -

numerals:

one,

two, three, ten, hundred, etc.

There are many more words of

Indo-European origin in the basic stock of the English

vocabulary.

(b) Common

Germanic

words are not to be found in other Indo-European languages but the

Germanic. They constitute a very large layer

of the vocabulary:

-

nouns:

hand,

life, sea, ship, meal, winter, ground, coal, goat; -

adjectives:

heavy,

deep, free, broad, sharp, grey; -

verbs:

to

buy, to drink, to find, to forget, to go, to have, to live, to make; -

pronouns: all,

each, he, self, such; -

adverbs:

again,

forward, near; ‘ -

prepositions:

after,

at, by, over, under, from, for.

The rest of the English vocabulary are borrowed

words, or loan

words.

Some scientists point out three periods of Latin borrowings in old

English:

-

Latin-Continental borrowings,

-

Latin-Celtic borrowings,

-

Latin borrowings connected with the Adoption of Christianity.

To the first period belong

military terms (wall,

street, etc.),

trade terms (pound,

inch), names

of containers (cup,

dish), names

of food (butter,

cheese), words

connected with building (chalk,

pitch), etc.

These were

concrete words that were adopted in purely oral manner, and they were

fully assimilated in the language. Roman influence was felt in the

names

of towns, e.g. Manchester,

Lancaster, etc.

from the Latin word caster

— лагерь.

Such

words as

port, fountain and

mountain

were

borrowed from Latin through

Celtic.

With

the Adoption of Christianity mostly religious or clerical terms were

borrowed: dean,

cross, alter, abbot (Latin); church, devil, priest, anthem,

school, martyr (Greek).

Latin and Greek borrowings of

the Middle English period are connected

with the Great Revival of Learning and are mostly scientific words:

formula,

inertia, maximum, memorandum, veto, superior, etc.

They

were

not fully assimilated, they retained their grammar forms.

Many words from Greek, the other major source of

English words, came

into English by way of French and Latin. Others were borrowed in

the sixteenth century when interest in classic culture was at its

height. Directly

or indirectly, Greek contributed athlete,

acrobat, elastic, magic, rhythm,

and many

others.

There are some classical

borrowings in Modern English as well: anaemia,

aspirin, iodin, atom, calorie, acid, valency, etc.

There are words formed

with the help of Latin and Greek morphemes (roots or affixes): tele,

auto, etc.

Latin and Greek words are

used to denote names of sciences, political and philosophic trends;

these borrowings usually have academic or literary associations (per

capita, dogma, drama, theory, and

pseudonym).

Many other

Latin words came into English through French.

French

is the

language that had most influence on the vocabulary of English; it

also influenced its spelling.

After the Norman invasion in 1066, English was

neglected by the Latin-writing and French-speaking authorities.

Northern French became the official language in England. And for the

next three hundred years, French was the language of the ruling

classes in England. During this period, thousands of new words came

into English, many of them relating to upper class pursuits: baron,

attorney, luxury.

There are several semantic groups of French borrowings:

-

government terms: to

govern, to administer, assembly, record, parliament; -

words connected with

feudalism: peasant,

servant, control, money, rent, subsidy; -

military terms: assault,

battle, soldier, army, siege, defence, lieutenant; -

words

connected with jury: bill,

defendant, plaintiff, judge, fine; -

words connected with art,

amusement, fashion, food: dance,

pleasure,

lace, pleat, supper, appetite, beauty, figure, etc.

During the seventeenth

century there was a change in the character of the borrowed words.

From French, English has taken lots of words to do with cooking, the

arts, and a more sophisticated lifestyle in general (chic,

prestige, leisure,

repertoire, resume, cartoon, critique, cuisine, chauffeur,

questionnaire,

coup, elite, avant-garde, bidet, detente, entourage).

In addition to independent words, English borrowed

from Greek, Latin, and French a number of word parts for use as

affixes and roots, for example prefixes like поп-,

de-, anti— that

may appear in hundreds of different words.

English has continued to borrow words from French

right down to the present, with the result that over

a third of modern English vocabulary derives from French.

Scandinavian Borrowings

are connected with the Scandinavian

Conquest of the British Isles, which took place at the end of the 8th

century. Scandinavians belonged to

the same group of peoples as Englishmen and the two languages were

similar.

The impact of Old Norwegian on the English

language is hard to evaluate.

Nine hundred words — for example, take,

leg, hit, skin, same —

are of Scandinavian origin. There

are probably hundreds more we cannot account for definitely, and in

the old territory of the Danelaw in

Northern England words like beck

(stream)

and garth

(yard)

survive in regional use. Words

beginning with sk

like sky

are Norse (the Danes — also called

Norsemen — conquered northern France, and finally England).

In many cases Scandinavian borrowings stood

alongside their English

equivalents. The Scandinavian skirt

originally

meant the same as the English shirt.

The Norse deyja

(to die) joined its Anglo-Saxon

synonym,

the English steorfa

(which

ends up as starve).

Other

synonyms include:

wish

and

want,

craft and

skill,

rear and

raise.

However,

many words were borrowed into English, e.g. cake,

egg, kid,

window, ill, happy, ugly, to call, to give, to get, etc.

Pronouns and pronominal forms were also borrowed from Scandinavian:

same,

both, though,

they, them, their.

In the modern period, English has borrowed from every important

language in the world

Over 120 languages are on

record as sources of the English vocabulary. From Japanese

come

karate,

judo, hara-kiri, kimono,

and tycoon; from

Arabic,

algebra,

algorithm, fakir, giraffe, sultan,

harem, mattress; from

Turkish,

yogurt,

kiosk, tulip; from

Farsi,

caravan,

shawl, bazaar, sherbet; from

Eskimo,

kayak,

igloo, anorak; from

Yiddish,

goy,

knish, latke, schmuck; from

Hindi,

thug,

punch, shampoo;

from

Amerindian

languages,

toboggan,

wigwam, Chicago, Missouri,

opossum. From

Italian

come words

connected with music and

the plastic arts, such as

piano, alto, incognito, bravo, ballerina, as

well as

motto,

casino, mafia, artichoke, etc.

German

expressions

in English have been coined either by tourists bringing back words

for new things they saw or by philosophers or historians describing

German concepts or experiences (kindergarten,

blitz, hamburger, pretzel, delicatessen, poodle, waltz, seminar). The

borrowings from other languages usually relate to things, which

English speakers experienced

for the first time abroad (Portuguese:

marmalade,

cobra; Spanish:

junta,

siesta, patio, mosquito, comrade, tornado, banana, guitar, marijuana,

vigilante; Dutch:

dock,

leak, pump, yacht, easel, cruise,

cole slaw, smuggle, gin, cookie, boom; Finnish:

sauna;

Russian:

bistro,

szar, balalaika, tundra, robot).

Although borrowing has been a very rich source of new words in

English, it is noteworthy that loan words are least common among the

most frequently used vocabulary items.

Most of the

borrowed words at once undergo the process of assimilation.

Assimilation of borrowed words is their adaptation to the system

of the receiving language in pronunciation, in grammar and in

spelling.

There are completely assimilated borrowings that correspond to

all the standards of the language (travel,

sport, street), partially

assimilated

words (taiga,

phenomena, police) and

unassimilated words (coup d’état,

tête-à-tête, ennui, éclat).

Borrowed words can be classified according to

the aspect which is borrowed. We can subdivide all borrowings into

the following groups:

-

phonetic

borrowings (table,

chair, people); -

translation

loans (Gospel,

pipe of peace, masterpiece); -

semantic

borrowings (pioneer); -

morphemic

borrowings (beautiful,

uncomfortable).

Language is a universal tool for every person in this world. It is the connecting link between nations, ethnicities, and people sharing a common background. The world of language is colorful and diverse and provides a glimpse into the very origins of humanity and civilizations. But languages from across the globe are all unique and mutually unintelligible. That’s why a lingua franca is necessary, a common language that all can learn and understand, and use across the planet. In modern times, that language is English. People everywhere can understand it and speak it, even if just a little. But do we ever stop to think about the origins of the English language? Where did it begin, how did it develop, and what makes it so universal to most of the people living on the planet today?

The first folio of the heroic epic poem Beowulf, written primarily in the West Saxon dialect of the Old English language by an anonymous early English poet. ( Public domain )

The Historic Root of the English Language: Anglo-Saxon

When we begin the story of the English language and its source, we need to reflect upon the history of England, i.e., Britain. Because it was the many turbulent episodes of the nation of England that have shaped the language that we know today. Different peoples coming in contact with Britain have all left their mark on the English language. For language is like a sponge: it soaks in all the foreign additions that suit it, which makes it better and easier to use.

Of course, English gets its name from the Germanic Anglo-Saxons that settled in England in mid-5th century AD and shaped the very future of what we know as English today. Around 410 AD, the Romans withdrew from Britain , leaving the area open for settlement by new peoples, in this case, the Germanic Anglo-Saxon tribes.

However, the land of Britain was not empty of language. The remaining Romano-British (Brythonic) Celtic peoples still lived there, but they were now largely influenced by the Romans. It is proposed by scholars that they spoke British Latin at this point, a vulgar Latin dialect that formed through contact with the Celts. To the north, in modern-day Scotland, were the Picts and the Scots, both speaking their own distinct insular Celtic languages.

When the Anglo-Saxon tribes arrived from northern Europe, however, they came by invitation. Ancient chronicles state that Vortigern, King of the Britons, invited these Germanic tribes in 449 AD, in order to repel the Picts who were invading from the north. But the land was too good for the Angles and the Saxons, and they chose to stay for good. From then on, their Germanic language became rooted in Britain, and gradually became the chief language used on the island, which is the English language.

The Anglo Saxons, pictured, brought a new language to Britain. Source: Archivist / Adobe Stock

The Anglo-Saxons Built the Foundations of the English Language

Still, the original or earlier languages of a conquered nation can never fully be eradicated. Even with the Anglo-Saxons firmly rooted in Britain, there were still plenty of words in use that were of Celtic or Latin origin. Many words, like street, wine, mile, kitchen, have their origins in Latin. Both the Brythonic Celts and the Germanic tribes were in contact with the Romans for centuries, and thus these words found their way into the English language from both sides.

However, we can also observe the Celtic words in England, mostly in place names. Places like Kent, Dover, Avon, and hundreds of others retained their original Celtic names over the centuries. Still, commonly used words such as loch, crumpet, gull, lawn, penguin, coombe, all have their roots in the Celtic languages of Britain.

The English language was also heavily influenced by old medieval Latin, especially via Christianity. Shown here is an ancient Catholic Latin inscription. ( alehnia / Adobe Stock)

As the Anglo-Saxons solidified their rule in Britain, forming their kingdoms, the so-called “ Old English ” language developed across England. Today, we know it as the earliest recorded form of the English language. It was divided into closely-related dialects: Mercian, Kentish, Northumbrian, and West Saxon , all of which were named for the separate kingdoms they established. The Anglo-Saxons grew powerful, and their language quickly overshadowed the Celtic and Latin that was spoken before. The Celtic speakers were pushed to the margins of the island, and their languages, such as Welsh and Cornish, are still confined to these areas of Britain today.

Although the earliest form of the English language, Old English sounds almost totally alien to what we know and use today. Here’s a snippet of a text written in Old English during the Anglo-Saxon period, with a modern translation. The differences are immense.

“Ac hē hit on him swīþe wræc, ond hīe him swā lāðe wǣron þæt hē oft wȳscte þæt ealle Rōmāne hæfden ǣnne swēoran, þæt hē hine raþost forceorfan meahte. Ond mid ungemete mǣnde þæt þǣr þā næs swelc sacu swelc þǣr oft ǣr wæs; ond hē self fōr oft on ōþra lond ond wolde gewin findan, ac hē ne meahte būton sibbe.”

Translation: “But he took severe revenge upon them, and they were hateful that he often wished that all Romans possessed a single neck so that he could most quickly cut through it. And with lack of moderation complained that there was no strife as there often formerly was; and he would often go into another land and would find battle, but he would not accept peace.”

The language of the Vikings and their rune letters gave English its grammatical basis. ( Pshenichka / Adobe Stock)

English Language Development: from 450 AD to the Present Day

On the whole, the English language is separated into following stages of development:

Old English: 450-1150 AD

Middle English : 1150-1500 AD

Early Modern English: 1500-1700 AD

Modern English: 1700 AD-present day

By the 6th century AD, Christianity had spread to Britain, and new, ecclesiastical words from Latin became an inseparable part of the English language. These included hymn, abbot, altar, priest, paper, school, bishop , and many other words. In the end, more than 400 such words were introduced. And that was just the beginning!

Just a couple of centuries later a new period of English history began with the arrival of the Vikings. Scandinavian seafarers raided Anglo-Saxon kingdoms from the 8th to 10th centuries AD, establishing many settlements in the process. Over time, the contact between them and the English left the most important and longest-lasting changes on the English language.

The Vikings introduced crucial new words into English , such as egg, call, crave, bask, keel, ill, fellow, leg, screech, odd, thrive, slaughter, berserk, ransack, husband, steak, skill, bug, wings, muck, myre anger, bag, sky, and hundreds of other commonly used words.

Changes to the language itself also appear during this period. The Old English word endings disappear, and a switch to a stricter word order appears, all under the influence of the Old Norse grammar. All of this points to the close contact between the Vikings and the English, and the fact that a language can never truly stop developing and accepting new features that make it better.

The Norman French language became the spoken language of the British elites who then added many French words to the everyday common people’s English vocabulary. ( Serge Aubert / Adobe Stock)

The French Normans Also Influenced The English Language

The next major change in the English language came with the Normans . In 1066 AD, the Norman leader William the Bastard won the critical Battle of Hastings, ushering in the era of Norman rule in Britain. Norman French became the main language of the nobility from that point onward and many French words were tightly woven into the English language as we know it. During this time, English was the language of the common folk, while the elites spoke the Anglo-Norman language. Norman itself had roots in Old Norse and introduced words that were both French and Norse in origin. Many of the Norman words that ended up as English words are connected to law or the military. Examples include archer, bailiff, chivalry, curfew, crime, judge, government, felony, fraud, injury, grief, dungeon, custard, baron, servant, messenger, story, and many more.

Borrowings from French occurred in two phases. The first one, as we said, was during the Norman period, mainly from 1066 to 1250. Then, from 1250 to 1500, the second phase took place. Only this time, it was the French speakers that started speaking English!

The reason for this historic conundrum is simple: the ruling French-speaking elite of Britain was finding it difficult to preserve the Anglo-Norman language over the centuries. So, the elites also gradually shifted to speaking English, the language of everyone else in the country. This is a simple process of assimilation.

As the elites shifted to English, they introduced further French words into the common, day-to-day vocabulary. And in the process they expanded and enriched the English language even more. Some words from this period are scandal, tavern, coward, vision, damage, aim, apply, serve, prefer, refuse, common, firm, sudden .

Scan of the Canterbury Tales Ellesmere manuscript from the 14th century AD show the first page of the Knight’s Tale, written in an English few can understand today. (Geoffrey Chaucer / Public domain )

The English Language as a Sponge

Still, even though the English language shifted from Anglo-Saxon Old English to the much different Middle English, it would nonetheless appear quite odd to the speakers of modern English. One great example surviving from this period is the work of Chaucer, a celebrated English poet. Here’s a snippet — written in Middle English from his 14th-century work, the “ Canterbury Tales .”

“Whan that aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of march hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

Tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the ram his halve cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

(so priketh hem nature in hir corages);

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;”

During the Early Modern Period of the English language, which is dated from the 1500s onwards, the Renaissance period begins to establish itself in Britain. Scholars and other learned men started a great influx of foreign words into English, many of them scholarly Greek and Latin terms. But that was not all.

England began its colonial expansions in this era, which resulted in lasting relationships with other European nations. Thus, more foreign words root entered the English language vocabulary. From Latin and Greek, we have words such as abdomen, anatomy, agile, atmosphere, catastrophe, ecstasy, history, critic, janitor, meditate, ultimate, and so on. However, words such as alcove, algebra, zenith, algorithm, amber, orange, admiral, azimuth, alchemy, and others, all come from Arabic, borrowed from Spanish and other Romance languages.

The British Empire covered 25% of the world, as shown in this 1898 Canadian stamp, and this also gave English lots of new words over the centuries. ( Spiroview Inc. / Adobe Stock)

Britain’s Global Colonial Era Introduced More New Words

The expansion of the English language continued steadily from the 1700s as English developed into its modern form. The English language was influenced by major colonial expansions across the globe, by the industrial revolution, literature, and mass immigration to America and elsewhere.

French continued to be a major influence on English, introducing new words associated with the latest trends of the era. Ballet, champagne, chic, salon, bastion, brigade, infantry, grenade, grotesque, shock, niche and other words we use today were introduced during this time.

From Spanish we have armada, canyon, barricade, guitar, mosquito, vigilante; from Italian broccoli, balcony, arsenal, fresco, cupola, piano, opera, viola, umbrella, macaroni, pantaloons.

As the English settled in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, and elsewhere, they introduced many new words adopted from the local inhabitants. Most of these were words for things the English never had: tattoo, pajamas, didgeridoo, boomerang, kangaroo, taboo, bamboo, tsunami, cacao, cannibal, chipmunk, hammock, skunk, squash, tomato, and hundreds of other words.

Today, the English language is the lingua franca of the modern world, spoken by roughly 1.35 billion people! ( nito / Adobe Stock)

The Universal Language of the World!

So, as we can see, the English language was constantly changing as it developed. Its origins lie in the migrations of ancient cultures to the British Isles. As they met, clashed, and lived together, their languages melted into one unified, diverse form of speech that is known as English today.

When it comes to its immense popularity across the world, the English language undoubtedly owes a lot to the British Empire period, which in 1924 covered almost 25% of planet Earth. During the colonial period, Englishmen spread to many corners of the world. And this is how the English language established itself as a global lingua franca , a common tongue that all can use, no matter where they are!

Top image: Monk chronicler writes an ancient manuscript. Source: Nejron Photo / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

References

Blake, N. 1996. A History of the English Language. Macmillan International Higher Education.

Burnley, D. 2014. The History of the English Language: A Sourcebook. Routledge.

Gelderen, E. 2014. A History of the English Language: Revised edition. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Strang, B. 2015. A History Of English. Routledge.

Various, 1992. The Cambridge History of the English Language. Cambridge University Press.