English word Rome comes from Proto-Germanic *Rūmō (Rome.), Late Latin Roma

Detailed word origin of Rome

| Dictionary entry | Language | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| *Rūmō | Proto-Germanic (gem-pro) | Rome. |

| Roma | Late Latin (LL) | |

| Rum | Old English (ang) | |

| Rome | Old English (ang) | Rome. |

| Rome | English (eng) | A city on the Tiber River on the Italian peninsula, the capital of a former empire and of the modern region of Lazio and nation of Italy.. Ancient Rome; the former Roman Empire; Roman civilization.. The Church of Rome, the Roman Catholic Church generally.. The Holy See, the leadership of the Roman Catholic Church, particularly prior to the establishment of the Vatican City in the 19th century. |

Words with the same origin as Rome

English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- Rom, Roome, Room, Rhoome, Romme, Rowme, Roym, Rum (archaic)

- Roma (uncommon)

Etymology[edit]

From Middle English Rome, from Old English Rōm, Rūm, from Proto-Germanic *Rūmō and influenced by Late Latin Rōma (“Rome, Constantinople”), from Classical Latin Rōma (“Rome”). In Roman mythology, the name was said to derive from Romulus, one of the founders of the city and its first king.

The name appears in a wide range of forms in Middle English, including Rom, Room, Roome, and Rombe as well as Rome; by early modern English, it appeared as Rome, Room, and Roome, with the spelling Rome occurring in Shakespeare and common from the early 18th century on. The final spelling was influenced by Norman, Middle French, Anglo-Norman, and Old French Rome.[1]

Pronunciation[edit]

- (UK), enPR: rōm, IPA(key): /ɹəʊm/, (archaic, dialectal) IPA(key): /ɹum/

- (US), enPR: rōm, IPA(key): /ɹoʊm/

- Rhymes: -əʊm

- Homophones: roam, Rom

Proper noun[edit]

Rome

- A city on the Tiber River on the Italian peninsula; ancient capital of the Roman Empire; capital city of Italy; capital city of the region of Lazio.

-

1599 (first performance), William Shakespeare, “The Tragedie of Iulius Cæsar”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act I, scene ii], line 157:

-

When could they say (till now) that talk’d of Rome,

That her wide Walles incompast but one man?

Now is it Rome indeed, and Roome enough

When there is in it but one onely man.

-

- 1866 December 8, ‘Filius Ecclesiæ’, Notes & Queries, «Rome:Room», 456 1:

- Within the last thirty weeks I have heard the word Rome pronounced Room by several old-fashioned people in the north of Ireland, some of my own relations among the number. On remonstrating with one of these, she said, «It was always Room when I was at school (say about 1830), and I am too old to change it now.»

-

- A metropolitan city of Lazio, Italy.

- (metonymically) The Italian government.

-

2016, Tiedtke, Per, chapter 2, in Germany, Italy and the International Economy 1929–1936: Co-operation or Rivalries at Times of Crisis?[1], Europe: Tectum Verlag, →ISBN, page 99:

-

At first, Berlin tried to amend the agreement to restore a German trade surplus, but Rome refused.

-

-

- Ancient Rome; the former Roman Empire; Roman civilization.

-

c. 1588–1593 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Lamentable Tragedy of Titus Andronicus”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act I, scene i], line 82:

-

These that suruiue, let Rome reward with loue.

-

-

1709, [Alexander Pope], An Essay on Criticism, London: […] W. Lewis […], published 1711, →OCLC, page 39:

-

Learning and Rome alike in Empire grew,

And Arts still follow’d where her Eagles flew;

From the same Foes [viz., Tyranny and Superstition], at last, both felt their Doom,

And the same Age saw Learning fall, and Rome.

-

-

1821, Lord Byron, Marino Faliero, Doge of Venice. An Historical Tragedy, in Five Acts. […], London: John Murray, […], →OCLC, Act V, scene i, page 149:

-

A wife’s dishonour unking’d Rome for ever.

-

-

- The Holy See, the leadership of the Roman Catholic Church, particularly prior to the establishment of the Vatican City in the 19th century.

- 1537 January 26, T. Starkey, letter:

- The wych you perauenture wyl impute to thys defectyon from Rome.

-

1591 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The First Part of Henry the Sixt”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act III, scene ii]:

- 1537 January 26, T. Starkey, letter:

- The Church of Rome, the Roman Catholic Church generally.

-

c. 1596 (date written), William Shakespeare, “The Life and Death of King Iohn”, in Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies […] (First Folio), London: […] Isaac Iaggard, and Ed[ward] Blount, published 1623, →OCLC, [Act V, scene ii], line 7:

-

- A number of places in the United States:

- An unincorporated community in Covington County, Alabama.

- A city, the county seat of Floyd County, Georgia.

- A census-designated place in Peoria County, Illinois.

- An unincorporated community in Perry County, Indiana.

- A village in Henry County, Iowa.

- A ghost town in Ellis County, Kansas.

- An unincorporated community in Sumner County, Kansas.

- An unincorporated community in Daviess County, Kentucky.

- A town in Kennebec County, Maine.

- An unincorporated community in Sunflower County, Mississippi.

- An unincorporated community in Douglas County, Missouri.

- A city in Oneida County, New York.

- A village in Green Township, Adams County, Ohio.

- Synonym: Stout (the name of the post office)

- An unincorporated community in Delaware County, Ohio.

- A ghost town in Morrow County, Ohio.

- An unincorporated community in Richland County, Ohio.

- An unincorporated community in Malheur County, Oregon.

- A borough in Bradford County, Pennsylvania.

- An unincorporated community in Smith County, Tennessee.

- A town and unincorporated community in Adams County, Wisconsin.

- A census-designated place in Jefferson County, Wisconsin.

- A surname.

Synonyms[edit]

- (archaic) Romeburg, Romeburgh, Romeland, Romelede, Romethede, Rome town

- (dated) Rome city

- Istanbul, Constantinople (new Rome)

- Moscow (third Rome, new Rome)

Derived terms[edit]

- Romes

- Roman

- Rome rule, Rome Rule

- when in Rome, do as the Romans do

- Rome was not built in a day

- do not sit in Rome and strive with the Pope

- all roads lead to Rome

- go to Rome with a mortar on one’s head

- (dated) Romish

Descendants[edit]

- → Georgian: რომი (romi)

- → Hindi: रोम (rom)

- → Thai: โรม (room)

Translations[edit]

city, capital of Italy

- Afrikaans: Rome (af)

- Aghwan: 𐕆𐕙𐕒𐕌 (hrom)

- Albanian: Romë

- Amharic: ሮማ (roma)

- Arabic: رُومَا f (rūmā), رُومِيَة (ar) f (rūmiya)

- Egyptian Arabic: روما f (ruma)

- Hijazi Arabic: روما f (rōma)

- Armenian: Հռոմ (hy) (Hṙom)

- Asturian: Roma f

- Azerbaijani: Roma (az)

- Bashkir: Рим (Rim)

- Basque: Erroma (eu)

- Belarusian: Рым m (Rym)

- Bengali: রোম (bn) (rōm)

- Breton: Roma (br)

- Bulgarian: Рим m (Rim)

- Burmese: ရောမ (my) (rau:ma.)

- Catalan: Roma (ca) f

- Chechen: Рим (Rim)

- Cherokee: ᎶᎻ (lomi), ᎶᎹ (loma)

- Chinese:

- Cantonese: 羅馬/罗马 (lo4 maa5)

- Hakka: 羅馬/罗马 (Lò-mâ)

- Mandarin: 羅馬/罗马 (zh) (Luómǎ)

- Min Dong: 羅馬/罗马 (Lò̤-mā)

- Min Nan: 羅馬/罗马 (Lô-má)

- Wu: 羅馬/罗马 (lu ma)

- Coptic:

- Bohairic: ⲣⲱⲙⲏ (rōmē)

- Sahidic: ϩⲣⲱⲙⲏ (hrōmē)

- Czech: Řím (cs) m

- Danish: Rom (da)

- Dutch: Rome (nl) n

- Egyptian: (hrm m)

- Esperanto: Romo (eo)

- Estonian: Rooma (et)

- Farefare: Dooma, Doom

- Faroese: Róm (fo) f, Rómaborg f

- Finnish: Rooma (fi)

- French: Rome (fr) f

- Friulian: Rome

- Galician: Roma (gl) f

- Georgian: რომი (romi)

- German: Rom (de) n

- Gothic: 𐍂𐌿𐌼𐌰 f (ruma)

- Greek: Ρώμη (el) f (Rómi)

- Ancient: Ῥώμη f (Rhṓmē)

- Gujarati: રોમ (rom)

- Hawaiian: Loma

- Hebrew: רוֹמָא (he) f (róma)

- Hindi: रोम (hi) (rom), रोमक (hi) m (romak)

- Hungarian: Róma (hu)

- Icelandic: Róm f, Rómaborg f

- Ido: Roma (io)

- Indonesian: Roma

- Irish: an Róimh f

- Italian: Roma (it) f

- Japanese: ローマ (ja) (Rōma), 羅馬 (ja) (Rōma) (dated)

- Kalmyk: Рим (Rim)

- Kannada: ರೋಮ್ (rōm)

- Kazakh: Рим (Rim)

- Khmer: រ៉ូម (km) (roum)

- Korean: 로마 (ko) (Roma), 나마(羅馬) (ko) (Nama) (dated), 라마(羅馬) (ko) (Rama) (dated, North Korea)

- Kurdish:

- Northern Kurdish: Roma (ku)

- Kyrgyz: Рим (Rim)

- Lao: ໂລມ (lōm), ໂຣມ (rōm)

- Latin: Rōma (la) f

- Latvian: Roma (lv) f

- Lithuanian: Roma (lt) f

- Macedonian: Рим m (Rim)

- Malay: Rom

- Malayalam: റോം (ṟōṃ)

- Maltese: Ruma

- Manx: Yn Raue f

- Maori: Rōma (mi)

- Maranao: Roma

- Marathi: रोम n (rom)

- Middle English: Rome, Roome

- Mongolian:

- Cyrillic: Ром (Rom)

- Nepali: रोम (rom)

- Norwegian:

- Bokmål: Roma (no), Rom (no)

- Nynorsk: Roma

- Occitan: Roma (oc)

- Old Church Slavonic:

- Cyrillic: Римъ (Rimŭ)

- Glagolitic: Ⱃⰹⰿⱏ m (Rimŭ)

- Old East Slavic: Римъ m (Rimŭ)

- Old English: Rōm f, Rōmeburh f

- Old Norse: Róm n, Róma f, Rómaborg f

- Old Occitan: Roma

- Old Portuguese: Roma

- Oriya: ରୋମ (or) (romô)

- Ossetian: Ром (Rom)

- Ottoman Turkish: قزل المه (Qızıl Elma)

- Pashto: روم (ps) m (rom), روما f (romã)

- Persian: رم (fa) (rom)

- Middle Persian: 𐭧𐭫𐭥𐭬 (ḥlʿm /hrōm/)[[Category:|ROME]]

- Polish: Rzym (pl) m

- Portuguese: Roma (pt) f

- Punjabi: ਰੋਮ (rom)

- Romanian: Roma (ro) f

- Russian: Рим (ru) m (Rim)

- Rusyn: Рим m (Rym)

- Sanskrit: रोम (sa) (roma), रोमक (sa) m (romaka), रोमकः (sa) m (romakaḥ), रोमकपुर (sa) n (romakapura), रोमकपत्तन (sa) n (romakapattana)

- Saterland Frisian: Room

- Scots: Roum

- Scottish Gaelic: an Ròimh f

- Serbo-Croatian:

- Cyrillic: Ри̑м m

- Roman: Rȋm (sh) m

- Silesian: Rzim m

- Sinhalese: රෝමය (rōmaya)

- Slovak: Rím (sk) m

- Slovene: Rím (sl) m

- Somali: Roma

- Sorbian:

- Lower Sorbian: Rom m

- Upper Sorbian: Rom m

- Spanish: Roma (es) f

- Swahili: Roma

- Swedish: Rom (sv)

- Tagalog: Roma

- Tajik: Рим (Rim), Рум (Rum)

- Tamil: உரோம் (urōm)

- Tatar: Рим (Rim)

- Telugu: రోమ్ (rōm)

- Thai: โรม (th) (room)

- Tibetan: རོ་མ (ro ma)

- Turkish: Roma (tr)

- Turkmen: Rim

- Ukrainian: Рим m (Rym)

- Urdu: روم (ur) (rom)

- Uyghur: رىم (rim)

- Uzbek: Rim

- Vietnamese: Rôma (vi), La Mã (vi) (dated)

- Volapük: Roma, (seven hills) Vellubelazif

- Welsh: Rhufain

- West Frisian: Rome

- Yiddish: רוים n (roym)

- Zhuang: Lozmaj

- Zulu: eRoma

metropolitan city in Lazio, Italy

- Finnish: Rooma (fi)

metonym for the Italian government

- Finnish: Rooma (fi)

empire

- Aghwan: 𐕆𐕙𐕒𐕌 (hrom)

- Arabic: رُومَا f (rūmā), الرُّوم (ar) f (ar-rūm)

- Armenian: Հռոմ (hy) (Hṙom)

- Old Armenian: please add this translation if you can

- Catalan: Roma (ca) f

- Czech: Řím (cs) m

- Danish: Romerriget, Det Romerske Kejserrige

- Esperanto: Romio

- Finnish: Rooma (fi), Rooman valtakunta (fi)

- Greek: ρωμαϊκή αυτοκρατορία f (romaïkí aftokratoría)

- Hebrew: רוֹמִי (he) f (rómi)

- Hindi: रोम (hi) m (rom), रोमक (hi) m (romak)

- Italian: impero romano m, Roma (it) f

- Japanese: ローマ帝国 (Rōma teikoku)

- Khmer: រ៉ូម (km) (room)

- Macedonian: Рим m (Rim)

- Maltese: Ruman

- Marathi: रोम n (rom)

- Persian: روم (fa) (rum)

- Middle Persian: 𐭧𐭫𐭥𐭬 (ḥlʿm /hrōm/)[[Category:|ROME]]

- Portuguese: Roma (pt) f

- Russian: Рим (ru) m (Rim)

- Vietnamese: La Mã (vi)

number of places in USA

- Finnish: Rome (fi)

See also[edit]

- Roma

- Romania

- romance, romantic

- Romulan

References[edit]

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. «Rome, n.»

Anagrams[edit]

- -more, Mero, More, Omer, Orem, Orme, erom, mero, mero-, moer, more, omer

Dutch[edit]

Etymology[edit]

- (capital of Italy) From Middle Dutch rome.

- (Maasdriel) First attested as Rome in 1830-1855. Named after the Italian city, allegedly because many Roman artefacts were found there.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈroː.mə/

- Hyphenation: Ro‧me

- Rhymes: -oːmə

Proper noun[edit]

Rome n

- Rome (the capital city of Italy)

- Rome (a metropolitan city of Lazio, Italy)

- A hamlet in Maasdriel, Gelderland, Netherlands.

Descendants[edit]

- Afrikaans: Rome

References[edit]

- van Berkel, Gerard; Samplonius, Kees (2018) Nederlandse plaatsnamen verklaard (in Dutch), Mijnbestseller.nl, →ISBN

Anagrams[edit]

- moer, more, roem

Finnish[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From English Rome.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈrome/, [ˈro̞me̞]

- IPA(key): /ˈrou̯m/, [ˈro̞u̯m]

- Rhymes: -ome

- Syllabification(key): ro‧me

Proper noun[edit]

Rome

- Rome (any of a number of localities in USA or elsewhere)

Declension[edit]

| Inflection of Rome (Kotus type 8/nalle, no gradation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| nominative | Rome | — | |

| genitive | Romen | — | |

| partitive | Romea | — | |

| illative | Romeen | — | |

| singular | plural | ||

| nominative | Rome | — | |

| accusative | nom. | Rome | — |

| gen. | Romen | ||

| genitive | Romen | — | |

| partitive | Romea | — | |

| inessive | Romessa | — | |

| elative | Romesta | — | |

| illative | Romeen | — | |

| adessive | Romella | — | |

| ablative | Romelta | — | |

| allative | Romelle | — | |

| essive | Romena | — | |

| translative | Romeksi | — | |

| instructive | — | — | |

| abessive | Rometta | — | |

| comitative | See the possessive forms below. |

| Possessive forms of Rome (type nalle) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

French[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From Old French Rome, from Latin Rōma.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ʁɔm/

- Homophones: rhum, ROM

Proper noun[edit]

Rome f

- Rome (the capital city of Italy)

- Rome (a metropolitan city of Lazio, Italy)

Derived terms[edit]

- à Rome, fais comme les Romains

- Nouvelle Rome

- Rome antique

- Rome ne s’est pas faite en un jour

- tous les chemins mènent à Rome

Descendants[edit]

- Guianese Creole: Ròm

- Haitian Creole: Wòm

- Lao: ໂຣມ (rōm)

Anagrams[edit]

- more, More, orme

Friulian[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Rome f

- Rome

[edit]

- roman

- romanesc

Italian[edit]

Proper noun[edit]

Rome f

- plural of Roma

- le due Rome, the two Romes

Anagrams[edit]

- -mero, Remo, ermo, mero, more, orme, remo, remò

Middle English[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- Roome, Rombe, Rume, Room, Rom

Etymology[edit]

From Old English Rōm, from Proto-West Germanic *Rūmu, from Proto-Germanic *Rūmō, from Latin Rōma.

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ˈroːm(ə)/, /ˈrɔːm(ə)/

- Rhymes: -oːm(ə), -ɔːm(ə)

Proper noun[edit]

Rome

- Rome (a city, the capital of the Papacy; ancient capital of the Roman Empire)

-

c. 1382 (date written), Geffray Chaucer [i.e., Geoffrey Chaucer], “Boetius de consolatione Philosophie. The Fyrst Boke.”, in [William Thynne], editor, The Workes of Geffray Chaucer Newlye Printed, […], [London: […] Richard Grafton for] Iohn Reynes […], published 1542, →OCLC, folio ccxxxv, recto, column 1:

-

But now I am removed from the cyte of Rome almoſt .V.C.M. paas, I am wythoute defence dampned to pꝛoscrepcion and to deathe […]

- But now I’ve been sent almost 500,000 paces from the city of Rome; I am without defence, sentenced to exile and death.

-

-

c. 1386–1388 (date written), Geffray Chaucer [i.e., Geoffrey Chaucer], “The Legende of Good Women: The Legende of Lucresse of Rome”, in [William Thynne], editor, The Workes of Geffray Chaucer Newlye Printed, […], [London: […] Richard Grafton for] Iohn Reynes […], published 1542, →OCLC, folio ccxxv, verso, column 2:

-

Ne never was ther king in Rome towne / Syns thilke day, ⁊ ſhe was holden there […]

- There was never a king in Rome after that day, and she was seen there […]

-

-

- The Roman Empire.

Descendants[edit]

- English: Rome

- Scots: Roum, Rome

References[edit]

- “Rọ̄me, n.”, in MED Online, Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, 2007, retrieved 2018-04-01.

Old French[edit]

Alternative forms[edit]

- Rume, Rumme (Anglo-Norman)

Etymology[edit]

From Latin Rōma.

Proper noun[edit]

Rome

- Rome (a city, the capital of the Papacy; ancient capital of the Roman Empire)

Descendants[edit]

- French: Rome

- Guianese Creole: Ròm

- Haitian Creole: Wòm

- Lao: ໂຣມ (rōm)

- Norman: Rome

- Picard: Rome

- Walloon: Rome

Walloon[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

- IPA(key): /ʀɔm/

Proper noun[edit]

Rome

- Rome (the capital city of Italy)

For as long as I can remember, I heard Rome was named after Romulus and that the naming was done by Romulus himself after he killed his brother Remus. This made sense to me as even in today’s English you can see the connection between the words Romulus and Rome. I did think Rome was named after Romulus, mostly because that’s what I had been told for years, but I’ve recently changed my mind on this after reviewing the information below.

It turns out that the leading theory on the etymology of Romulus is that his name means “of Rome”. This etymology struck me as odd, given that for Romulus to acquire his name, this city of which he is named after would already have to have a name. Given this etymology, the idea that Romulus named the city or that the city was named after Romulus cannot be true, as he is named after the city. But from where does the name of the city originate?

Enrique Cabrejas is of the opinion that Rome (Roma/RO-ma) can be translated as “by Force” or “God’s Hand”. He says that Romulus and Remus are nicknames given to the characters due to their stories and personalities. Romulus can be translated as “Lionforce” or “The strong lion” and Remus can be translated as “Backsliding” on “guilt”, “blame”, or “misfortune”.[1]

The idea of Roma meaning “of Force” or “God’s Hand” is backed up by the writings of Plutarch. “This great name of Rome, with much glory has spread among all men, (…) and -the force- the weapons given this name to the city, that means Rome.” Parallel Lives: Romulus. Plutarch. The story of the “Rape of the Sabines” also may add to the idea that Rome means “by Force”, as the women were abducted and taken to Rome to help populate the city. I think the translation from Cabrejas is warranted, but I wanted to dig deeper into the theories abou which words Rome might descend from (and so I did).

Roma, Romulus, and Remus are Latin names. The Latin words in this case are based upon Greek words. In Greek, “Rome” [Ρώμη] means “power,” “force,” “fighting army” and “speed tactics”. H. G. Liddell and R. Scot argue that the Latin Roma stems from a Greek verb, roomai, which among other things means “to rush/rush on”.[2] I note here that the English word “rush” shares a similar sound to the word Rasna (or Rasenna), which is what the Etruscans called themselves. Rasenna currently has an unknown etymology. It is also close to the word Rus, which is where the word Russia finds its root. The similarity in sound and spelling is not highly significant in and of itself, but given more variables, the idea of a deeper connectedness appears to me to gain more gravity. I explore this more below. Keep in mind that in the legend, when Romulus and Remus were babies, they were abandoned and thrown into the River Tiber.

Out of all the rivers in Europe, of which there are many, the Volga is the longest one. It has a length of about 2,193 miles (3529 kilometers). It starts in the Valdai Hills, northwest of Moscow, Russia, and it ends in the Caspian Sea (which is the world’s largest inland body of water). The Volga is also popularly considered the National River of Russia.

F. Knauer (Moscow, 1901) traced the etymology of Rus to the Persian name for the Volga, which is ولگا. Prof. George Vernadsky suggested that it stems from the Aryan word for water/moisture. Both etymologies are associated with water, thus, Rus is associated with water, same as the origin of Romulus and Remus. Another idea is that it can be traced to Rosh from the Biblical book of Ezekial. Additionally, there are claims that the word Rus stems from an Old Norse term for “men who row”.[3] Altogether, these ideas lead me to conclude that the original word that inspired Rus was used to refer to people who navigated the rivers. I also now think that Rus and Rome may share a similar root word. Another possibility might be that this is explained by both of their origin stories involving the existence of a mighty river.

Personally, I couldn’t help but notice that the Persian name for Volga looks somewhat similar to a reverse writing of the Greek name for Rome. Note the way Romulus and Remus’ names are written on the mosaic in the header image. The PW is somewhat separated from the rest of their names. Whether this is coincidence or something more is for someone else to decide, I just wanted to point it out in light of drawing connections between all these words with obscure origins.

Reportedly, the name Remus descends from a word meaning “twin”. The Latin Remus could also descend from the Ancient Greek words eretmós (oar) or erétēs, (rower).[4], [5] I think these are both reasonable ancestor words for Remus, as Romulus and him were twins and both survived the river. Another note to make is that while rowing with one oar can help you navigate the waters, rowing with two oars is where the magic happens.

The word rower (which Remus is arguably based on) can be defined as “a person who rows”. This is the singular version of the definition for the word from which Rus stems. I think the idea of seafaring or traveling on rivers is inseparable from the creation of the Latin word Roma, and that this also provides insight into the history of the word Rus, and potentially Rasenna as well.

The other “founder” of Rome, Aeneas, may also play a role here, given his legendary voyages prior to founding the city. The etymology for his name is obscure and mysterious. Possibly it means “”praise-worthy,” from ainos “tale, story, saying, praise” (related to enigma); or perhaps related to ainos “horrible, terrible.””[6] Whatever the case may be, both foundation stories (that of Aeneas and that of the twins) both feature an important part involving navigating the waters.

I think a more exhaustive study on the origins of the words Rome, Romulus, and Remus (as well as Rus and Rasenna) will need to be conducted before generating any serious convictions on the topic. Right now, I think the best explanation as to how the characters obtained their names is that the name were assigned to them later on as nicknames to be remembered by. The words from which these nicknames descend is still debatable. This article sums up my preliminary observations.

Click here to see how Romulus and Remus have been depicted in art throughout the centuries.

References:

[1] – Cabrejas, Enrique. “Rome. The Etymological Origins” (2016). http://ispcjournal.org/journals/2016-16/Cabrejas_16.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1-u55Xx56g3sCuSORChhXvCAKArSIGE6ygjAH94jcXMnT_JBRtj_DVUDg. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

[2] – “Etymology of Rome” (12 Apr. 2019). https://ewonago.blogspot.com/2009/04/etymology-of-rome.html. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

[3] – Wiejack, Marta. “Here’s Why Russia Is Called Russia” (18 Jun. 2018). https://theculturetrip.com/europe/russia/articles/heres-why-russia-is-called-russia/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

[4] – https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Remus. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

[5] – https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/remus. Accessed 9 Dec. 2019.

[6] – https://www.etymonline.com/word/aeneas. Accessed 9 Sept. 2020.

Gain access to exclusive Ctruth activities, benefits, and content @

Help support Ctruth directly @

What does Rome mean?

a city in and the capital of Italy in the central part on the Tiber: ancient capital of the Roman Empire site of Vatican City seat of authority of the Roman Catholic Church. … the ancient Italian kingdom republic and empire whose capital was the city of Rome. the Roman Catholic Church.

What is the meaning of ancient Rome?

In historiography ancient Rome describes Roman civilization from the founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD in turn encompassing the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC) Roman Republic (509–27 BC) and Roman Empire (27 BC–476 AD) until the …

What type of word is Rome?

A province of Latium Italy. A city the capital of the province of Latium and also of Italy. The Roman Empire.

What is another word for Rome?

Rome Synonyms – WordHippo Thesaurus.

…

What is another word for Rome?

| Constantinople | Istanbul |

|---|---|

| Romeburgh | Rome city |

| Romeland | Romelede |

| Romethede | Rome town |

See also what is a jina

Is Rome a word?

No rome is not in the scrabble dictionary.

How did Rome get its name?

Legend of Rome origin

The origin of the city’s name is thought to be that of the reputed founder and first ruler the legendary Romulus. … The brothers argued Romulus killed Remus and then named the city Rome after himself.

Who are called Romans?

The Romans (Latin: Rōmānī Ancient Greek: Ῥωμαῖοι romanized: Rhōmaîoi) were a cultural group variously referred to as an ethnicity or a nationality that in classical antiquity from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD came to rule the Near East North Africa and large parts of Europe through conquests made …

Are there still Romans today?

There are no Romans per se today. Their own success and colossal expansion in Europe and elsewhere meant that they became a minority in their own empire and gradually mixed with many other populations that they assimilated and intermarried with.

How old is Rome?

Rome’s history spans 28 centuries. While Roman mythology dates the founding of Rome at around 753 BC the site has been inhabited for much longer making it a major human settlement for almost three millennia and one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in Europe.

What’s the opposite of Roman?

What is the opposite of roman?

| italic | oblique |

|---|---|

| slanted | sloping |

| cursive | aslant |

| aslope |

What are Roman symbols?

The Symbols

The Roman numeral system uses only seven symbols: I V X L C D and M. I represents the number 1 V represents 5 X is 10 L is 50 C is 100 D is 500 and M is 1 000. Different arrangements of these seven symbols represent different numbers.

What is the capital of Italian?

Rome

How do u spell Rome?

Correct spelling for the English word “rome” is [ɹˈə͡ʊm] [ɹˈəʊm] [ɹ_ˈəʊ_m] (IPA phonetic alphabet).

What is Roman in Latin?

From Latin Rōmānus from rōmānus (“Roman of Rome” adjective).

Who built Rome?

According to legend Ancient Rome was founded by the two brothers and demigods Romulus and Remus on 21 April 753 BCE. The legend claims that in an argument over who would rule the city (or in another version where the city would be located) Romulus killed Remus and named the city after himself.

See also what to put in a geocache container

Does Rome have a nickname?

The Eternal City is one of the most popular nicknames for Rome for excellent reasons.

Who started Roman?

According to tradition on April 21 753 B.C. Romulus and his twin brother Remus found Rome on the site where they were suckled by a she-wolf as orphaned infants.

Why is Italy not called Rome?

The identity of ‘Roman’ was no longer connected to the Italian peninsula in any way and so ‘Rome’ never came to refer to the entire peninsula. Instead like the Romans post-Augustus they referred to the peninsula as a whole as Italy.

Are Romans Greek or Italian?

So to sum up Romans were originally Italians. But their last part of the empire which lasted many centuries was Greek speaking. Romans were Greek speakers.

What color were Romans?

No the ancient greeks and romans were not “black” in the modern sense of the word. They were white.

When did Romans become Italian?

Italians (tribes of people on the Italian peninsula) became “Roman” citizens when Rome expanded and enfranchised them in the fifth through first centuries BCE. Then they were “Roman” through the 4th century CE.

Why did the Rome fall?

Invasions by Barbarian tribes

The most straightforward theory for Western Rome’s collapse pins the fall on a string of military losses sustained against outside forces. Rome had tangled with Germanic tribes for centuries but by the 300s “barbarian” groups like the Goths had encroached beyond the Empire’s borders.

What language did Romans speak?

Classical Latin

Classical Latin the language of Cicero and Virgil became “dead” after its form became fixed whereas Vulgar Latin the language most Romans ordinarily used continued to evolve as it spread across the western Roman Empire gradually becoming the Romance languages.

What is Rome sister city?

Since 9 April 1956 Rome and Paris have been exclusively and reciprocally twinned with each other following the motto: “Only Paris is worthy of Rome only Rome is worthy of Paris.” Within Europe town twinning is supported by the European Union.

When did Rome fall?

395 AD

Who were the original Romans?

The Romans are the people who originated from the city of Rome in modern day Italy. Rome was the centre of the Roman Empire – the lands controlled by the Romans which included parts of Europe (including Gaul (France) Greece and Spain) parts of North Africa and parts of the Middle East.

How do you use Rome in a sentence?

Rome sentence example

- If you visit Rome and make your way to the Forum nearby you will see the Arch of Titus. …

- I read the histories of Greece Rome and the United States. …

- All Rome was in terror.

See also what is geography class

What is the opposite of being wrong?

Right is a direction the opposite of left. Most people are right-handed. Right is also correct: the opposite of wrong. … You can be morally correct or “in the right.” You can right a wrong by making up for an injustice.

Is Rome a noun?

Rome (proper noun)

What is Rome known for?

Rome is known for its stunning architecture with the Colleseum Pantheon and Trevi Fountain as the main attractions. It was the center of the Roman Empire that ruled the European Continent for several ages. And you’ll find the smallest country in the world in Rome Vatican City.

What is 4 as a Roman numeral?

Roman Numerals

| # | RN |

|---|---|

| 3 | III |

| 4 | IV |

| 5 | V |

| 6 | VI |

How do you write 99 in Roman numerals?

Roman Numbers 1 to 100. Roman Numbers 100 to 1000. Roman Letters. Rules to write Roman Numerals.

…

Roman Numerals 1 to 100.

| Roman Numeral | XXXIX |

|---|---|

| Roman Numeral | LIX |

| Roman Numeral | LXXIX |

| Number | 99 |

| Roman Numeral | XCIX |

What was Italy called before it was called Italy?

Whilst the lower peninsula of what is now known as Italy was known is the Peninsula Italia as long ago as the first Romans (people from the City of Rome) as long about as 1 000 BCE the name only referred to the land mass not the people.

Who rules Rome today?

Rome is the largest of Italy’s 8101 comuni and is governed by a mayor and a city council. The seat of the comune is in on the Capitoline Hill the historic seat of government in Rome.

Ancient Rome 101 | National Geographic

The Roman Empire – 5 Things You Should Know – History for Kids – Rome

ROMAN EMPIRE | Educational Video for Kids.

Roma and Diana are playing with slimes | Fun games with dad

|

Rome Roma (Italian) |

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city and comune |

|

| Roma Capitale | |

|

Clockwise from top: the Colosseum; St. Peter’s Basilica; Castel Sant’Angelo; Ponte Sant’Angelo; Trevi Fountain; and the Pantheon. |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Etymology: Possibly Etruscan: Rumon, lit. ‘river’ (See Etymology). | |

| Nickname(s):

Urbs Aeterna (Latin) Caput Mundi (Latin) Throne of St. Peter |

|

The territory of the comune (Roma Capitale, in red) inside the Metropolitan City of Rome (Città Metropolitana di Roma, in yellow). The white spot in the centre is Vatican City. |

|

|

Rome Location within Italy Rome Location within Europe |

|

| Coordinates: 41°53′36″N 12°28′58″E / 41.89333°N 12.48278°ECoordinates: 41°53′36″N 12°28′58″E / 41.89333°N 12.48278°E | |

| Country | Italy[a] |

| Region | Lazio |

| Metropolitan city | Rome Capital |

| Founded | 753 BC |

| Founded by | King Romulus (legendary)[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Roberto Gualtieri (PD) |

| • Legislature | Capitoline Assembly |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,285 km2 (496.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 21 m (69 ft) |

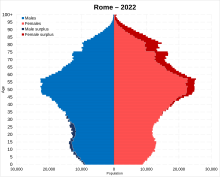

| Population

(31 December 2019) |

|

| • Rank | 1st in Italy (3rd in the EU) |

| • Density | 2,236/km2 (5,790/sq mi) |

| • Comune | 2,860,009[2] |

| • Metropolitan City | 4,342,212[3] |

| Demonym(s) | Italian: romano(i) (masculine), romana(e) (feminine) English: Roman(s) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| CAP code(s) |

00100; 00118 to 00199 |

| Area code | 06 |

| Website | comune.roma.it |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | Historic Centre of Rome, the Properties of the Holy See in that City Enjoying Extraterritorial Rights and San Paolo Fuori le Mura |

| Reference | 91 |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th Session) |

| Area | 1,431 ha (3,540 acres) |

Rome City Centre

Metro station, use fullscreen to show Termini

Point of interest

Rome (Italian and Latin: Roma [ˈroːma] (listen)) is the capital city of Italy. It is also the capital of the Lazio region, the centre of the Metropolitan City of Rome, and a special comune named Comune di Roma Capitale. With 2,860,009 residents in 1,285 km2 (496.1 sq mi),[2] Rome is the country’s most populated comune and the third most populous city in the European Union by population within city limits. The Metropolitan City of Rome, with a population of 4,355,725 residents, is the most populous metropolitan city in Italy.[3] Its metropolitan area is the third-most populous within Italy.[4] Rome is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, within Lazio (Latium), along the shores of the Tiber. Vatican City (the smallest country in the world)[5] is an independent country inside the city boundaries of Rome, the only existing example of a country within a city. Rome is often referred to as the City of Seven Hills due to its geographic location, and also as the «Eternal City».[6] Rome is generally considered to be the «cradle of Western civilization and Christian culture», and the centre of the Catholic Church.[7][8][9]

Rome’s history spans 28 centuries. While Roman mythology dates the founding of Rome at around 753 BC, the site has been inhabited for much longer, making it a major human settlement for almost three millennia and one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in Europe.[10] The city’s early population originated from a mix of Latins, Etruscans, and Sabines. Eventually, the city successively became the capital of the Roman Kingdom, the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and is regarded by many as the first-ever Imperial city and metropolis.[11] It was first called The Eternal City (Latin: Urbs Aeterna; Italian: La Città Eterna) by the Roman poet Tibullus in the 1st century BC, and the expression was also taken up by Ovid, Virgil, and Livy.[12][13] Rome is also called «Caput Mundi» (Capital of the World). After the fall of the Empire in the west, which marked the beginning of the Middle Ages, Rome slowly fell under the political control of the Papacy, and in the 8th century, it became the capital of the Papal States, which lasted until 1870. Beginning with the Renaissance, almost all popes since Nicholas V (1447–1455) pursued a coherent architectural and urban programme over four hundred years, aimed at making the city the artistic and cultural centre of the world.[14] In this way, Rome became first one of the major centres of the Renaissance[15] and then the birthplace of both the Baroque style and Neoclassicism. Famous artists, painters, sculptors, and architects made Rome the centre of their activity, creating masterpieces throughout the city. In 1871, Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, which, in 1946, became the Italian Republic.

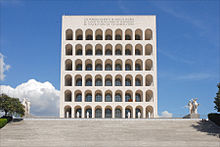

In 2019, Rome was the 14th most visited city in the world, with 8.6 million tourists, the third most visited city in the European Union, and the most popular tourist destination in Italy.[16] Its historic centre is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.[17] The host city for the 1960 Summer Olympics, Rome is also the seat of several specialised agencies of the United Nations, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The city also hosts the Secretariat of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union for the Mediterranean[18] (UfM) as well as the headquarters of many international businesses, such as Eni, Enel, TIM, Leonardo, and banks such as BNL. Numerous companies are based within Rome’s EUR business district, such as the luxury fashion house Fendi located in the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana. The presence of renowned international brands in the city has made Rome an important centre of fashion and design, and the Cinecittà Studios have been the set of many Academy Award–winning movies.[19]

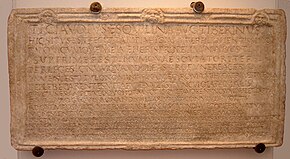

Etymology

According to the Ancient Romans’ founding myth,[20] the name Roma came from the city’s founder and first king, Romulus.[1]

However, it is possible that the name Romulus was actually derived from Rome itself.[21] As early as the 4th century, there have been alternative theories proposed on the origin of the name Roma. Several hypotheses have been advanced focusing on its linguistic roots which however remain uncertain:[22]

- From Rumon or Rumen, archaic name of the Tiber, which in turn is supposedly related to the Greek verb ῥέω (rhéō) ‘to flow, stream’ and the Latin verb ruō ‘to hurry, rush’;[b]

- From the Etruscan word 𐌓𐌖𐌌𐌀 (ruma), whose root is *rum- «teat», with possible reference either to the totem wolf that adopted and suckled the cognately named twins Romulus and Remus, or to the shape of the Palatine and Aventine Hills;

- From the Greek word ῥώμη (rhṓmē), which means strength.[c]

History

Earliest history

While there have been discoveries of archaeological evidence of human occupation of the Rome area from approximately 14,000 years ago, the dense layer of much younger debris obscures Palaeolithic and Neolithic sites.[10] Evidence of stone tools, pottery, and stone weapons attest to about 10,000 years of human presence. Several excavations support the view that Rome grew from pastoral settlements on the Palatine Hill built above the area of the future Roman Forum. Between the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, each hill between the sea and the Capitol was topped by a village (on the Capitol Hill, a village is attested since the end of the 14th century BC).[23] However, none of them yet had an urban quality.[23] Nowadays, there is a wide consensus that the city developed gradually through the aggregation («synoecism») of several villages around the largest one, placed above the Palatine.[23] This aggregation was facilitated by the increase of agricultural productivity above the subsistence level, which also allowed the establishment of secondary and tertiary activities. These, in turn, boosted the development of trade with the Greek colonies of southern Italy (mainly Ischia and Cumae).[23] These developments, which according to archaeological evidence took place during the mid-eighth century BC, can be considered as the «birth» of the city.[23] Despite recent excavations at the Palatine hill, the view that Rome was founded deliberately in the middle of the eighth century BC, as the legend of Romulus suggests, remains a fringe hypothesis.[24]

Legend of the founding of Rome

Traditional stories handed down by the ancient Romans themselves explain the earliest history of their city in terms of legend and myth. The most familiar of these myths, and perhaps the most famous of all Roman myths, is the story of Romulus and Remus, the twins who were suckled by a she-wolf.[20] They decided to build a city, but after an argument, Romulus killed his brother and the city took his name. According to the Roman annalists, this happened on 21 April 753 BC.[25] This legend had to be reconciled with a dual tradition, set earlier in time, that had the Trojan refugee Aeneas escape to Italy and found the line of Romans through his son Iulus, the namesake of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.[26]

This was accomplished by the Roman poet Virgil in the first century BC. In addition, Strabo mentions an older story, that the city was an Arcadian colony founded by Evander. Strabo also writes that Lucius Coelius Antipater believed that Rome was founded by Greeks.[27][28]

Monarchy and republic

After the foundation by Romulus according to a legend,[25] Rome was ruled for a period of 244 years by a monarchical system, initially with sovereigns of Latin and Sabine origin, later by Etruscan kings. The tradition handed down seven kings: Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus.[25]

The Ancient-Imperial-Roman palaces of the Palatine, a series of palaces located in the Palatine Hill, express power and wealth of emperors from Augustus until the 4th century.

In 509 BC, the Romans expelled the last king from their city and established an oligarchic republic. Rome then began a period characterised by internal struggles between patricians (aristocrats) and plebeians (small landowners), and by constant warfare against the populations of central Italy: Etruscans, Latins, Volsci, Aequi, and Marsi.[29] After becoming master of Latium, Rome led several wars (against the Gauls, Osci-Samnites and the Greek colony of Taranto, allied with Pyrrhus, king of Epirus) whose result was the conquest of the Italian peninsula, from the central area up to Magna Graecia.[30]

The third and second century BC saw the establishment of Roman hegemony over the Mediterranean and the Balkans, through the three Punic Wars (264–146 BC) fought against the city of Carthage and the three Macedonian Wars (212–168 BC) against Macedonia.[31] The first Roman provinces were established at this time: Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, Hispania, Macedonia, Achaea and Africa.[32]

From the beginning of the 2nd century BC, power was contested between two groups of aristocrats: the optimates, representing the conservative part of the Senate, and the populares, which relied on the help of the plebs (urban lower class) to gain power. In the same period, the bankruptcy of the small farmers and the establishment of large slave estates caused large-scale migration to the city. The continuous warfare led to the establishment of a professional army, which turned out to be more loyal to its generals than to the republic. Because of this, in the second half of the second century and during the first century BC there were conflicts both abroad and internally: after the failed attempt of social reform of the populares Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus,[33] and the war against Jugurtha,[33] there was a civil war from which the general Sulla emerged victorious.[33] A major slave revolt under Spartacus followed,[34] and then the establishment of the first Triumvirate with Caesar, Pompey and Crassus.[34]

The Imperial fora belong to a series of monumental fora (public squares) constructed in Rome by the emperors. Also seen in the image is Trajan’s Market.

The conquest of Gaul made Caesar immensely powerful and popular, which led to a second civil war against the Senate and Pompey. After his victory, Caesar established himself as dictator for life.[34] His assassination led to a second Triumvirate among Octavian (Caesar’s grandnephew and heir), Mark Antony and Lepidus, and to another civil war between Octavian and Antony.[35]

Empire

In 27 BC, Octavian became princeps civitatis and took the title of Augustus, founding the principate, a diarchy between the princeps and the senate.[35] During the reign of Nero, two thirds of the city was ruined after the Great Fire of Rome, and the persecution of Christians commenced.[36][37][38] Rome was established as a de facto empire, which reached its greatest expansion in the second century under the Emperor Trajan. Rome was confirmed as caput Mundi, i.e. the capital of the known world, an expression which had already been used in the Republican period. During its first two centuries, the empire was ruled by emperors of the Julio-Claudian,[39] Flavian (who also built an eponymous amphitheatre, known as the Colosseum),[39] and Antonine dynasties.[40] This time was also characterised by the spread of the Christian religion, preached by Jesus Christ in Judea in the first half of the first century (under Tiberius) and popularised by his apostles through the empire and beyond.[41] The Antonine age is considered the zenith of the Empire, whose territory ranged from the Atlantic Ocean to the Euphrates and from Britain to Egypt.[40]

The Roman Empire at its greatest extent in 117 AD, approximately 6.5 million km2 (2.5 million sq mi)[42] of land surface

The Roman Forum are the remains of those buildings that during most of ancient Rome’s time represented the political, legal, religious and economic centre of the city and the neuralgic centre of all the Roman civilisation.[43]

After the end of the Severan Dynasty in 235, the Empire entered into a 50-year period known as the Crisis of the Third Century during which there were numerous putsches by generals, who sought to secure the region of the empire they were entrusted with due to the weakness of central authority in Rome. There was the so-called Gallic Empire from 260 to 274 and the revolts of Zenobia and her father from the mid-260s which sought to fend off Persian incursions. Some regions – Britain, Spain, and North Africa – were hardly affected. Instability caused economic deterioration, and there was a rapid rise in inflation as the government debased the currency in order to meet expenses. The Germanic tribes along the Rhine and north of the Balkans made serious, uncoordinated incursions from the 250s–280s that were more like giant raiding parties rather than attempts to settle. The Persian Empire invaded from the east several times during the 230s to 260s but were eventually defeated.[44] Emperor Diocletian (284) undertook the restoration of the State. He ended the Principate and introduced the Tetrarchy which sought to increase state power. The most marked feature was the unprecedented intervention of the State down to the city level: whereas the State had submitted a tax demand to a city and allowed it to allocate the charges, from his reign the State did this down to the village level. In a vain attempt to control inflation, he imposed price controls which did not last. He or Constantine regionalised the administration of the empire which fundamentally changed the way it was governed by creating regional dioceses (the consensus seems to have shifted from 297 to 313/14 as the date of creation due to the argument of Constantin Zuckerman in 2002 «Sur la liste de Verone et la province de grande armenie, Melanges Gilber Dagron). The existence of regional fiscal units from 286 served as the model for this unprecedented innovation. The emperor quickened the process of removing military command from governors. Henceforth, civilian administration and military command would be separate. He gave governors more fiscal duties and placed them in charge of the army logistical support system as an attempt to control it by removing the support system from its control. Diocletian ruled the eastern half, residing in Nicomedia. In 296, he elevated Maximian to Augustus of the western half, where he ruled mostly from Mediolanum when not on the move.[44] In 292, he created two ‘junior’ emperors, the Caesars, one for each Augustus, Constantius for Britain, Gaul, and Spain whose seat of power was in Trier and Galerius in Sirmium in the Balkans. The appointment of a Caesar was not unknown: Diocletian tried to turn into a system of non-dynastic succession. Upon abdication in 305, the Caesars succeeded and they, in turn, appointed two colleagues for themselves.[44]

After the abdication of Diocletian and Maximian in 305 and a series of civil wars between rival claimants to imperial power, during the years 306–313, the Tetrarchy was abandoned. Constantine the Great undertook a major reform of the bureaucracy, not by changing the structure but by rationalising the competencies of the several ministries during the years 325–330, after he defeated Licinius, emperor in the East, at the end of 324. The so-called Edict of Milan of 313, actually a fragment of a letter from Licinius to the governors of the eastern provinces, granted freedom of worship to everyone, including Christians, and ordered the restoration of confiscated church properties upon petition to the newly created vicars of dioceses. He funded the building of several churches and allowed clergy to act as arbitrators in civil suits (a measure that did not outlast him but which was restored in part much later). He transformed the town of Byzantium into his new residence, which, however, was not officially anything more than an imperial residence like Milan or Trier or Nicomedia until given a city prefect in May 359 by Constantius II; Constantinople.[45]

Christianity in the form of the Nicene Creed became the official religion of the empire in 380, via the Edict of Thessalonica issued in the name of three emperors – Gratian, Valentinian II, and Theodosius I – with Theodosius clearly the driving force behind it. He was the last emperor of a unified empire: after his death in 395, his sons, Arcadius and Honorius divided the empire into a western and an eastern part. The seat of government in the Western Roman Empire was transferred to Ravenna in 408, but from 450 the emperors mostly resided in the capital city, Rome.[46]

Rome, which had lost its central role in the administration of the empire, was sacked in 410 by the Visigoths led by Alaric I,[47] but very little physical damage was done, most of which was repaired. What could not be so easily replaced were portable items such as artwork in precious metals and items for domestic use (loot). The popes embellished the city with large basilicas, such as Santa Maria Maggiore (with the collaboration of the emperors). The population of the city had fallen from 800,000 to 450–500,000 by the time the city was sacked in 455 by Genseric, king of the Vandals.[48] The weak emperors of the fifth century could not stop the decay, leading to the deposition of Romulus Augustus on 22 August 476, which marked the end of the Western Roman Empire and, for many historians, the beginning of the Middle Ages.[45] The decline of the city’s population was caused by the loss of grain shipments from North Africa, from 440 onward, and the unwillingness of the senatorial class to maintain donations to support a population that was too large for the resources available. Even so, strenuous efforts were made to maintain the monumental centre, the palatine, and the largest baths, which continued to function until the Gothic siege of 537. The large baths of Constantine on the Quirinale were even repaired in 443, and the extent of the damage exaggerated and dramatised.[49] However, the city gave an appearance overall of shabbiness and decay because of the large abandoned areas due to population decline. The population declined to 500,000 by 452 and 100,000 by 500 AD (perhaps larger, though no certain figure can be known). After the Gothic siege of 537, the population dropped to 30,000 but had risen to 90,000 by the papacy of Gregory the Great.[50] The population decline coincided with the general collapse of urban life in the West in the fifth and sixth centuries, with few exceptions. Subsidized state grain distributions to the poorer members of society continued right through the sixth century and probably prevented the population from falling further.[51] The figure of 450,000–500,000 is based on the amount of pork, 3,629,000 lbs. distributed to poorer Romans during five winter months at the rate of five Roman lbs per person per month, enough for 145,000 persons or 1/4 or 1/3 of the total population.[52] Grain distribution to 80,000 ticket holders at the same time suggests 400,000 (Augustus set the number at 200,000 or one-fifth of the population).

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, Rome was first under the control of Odoacer and then became part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom before returning to East Roman control after the Gothic War, which devastated the city in 546 and 550. Its population declined from more than a million in 210 AD to 500,000 in 273[53] to 35,000 after the Gothic War (535–554),[54] reducing the sprawling city to groups of inhabited buildings interspersed among large areas of ruins, vegetation, vineyards and market gardens.[55] It is generally thought the population of the city until 300 AD was 1 million (estimates range from 2 million to 750,000) declining to 750–800,000 in 400 AD, 450–500,000 in 450 AD and down to 80–100,000 in 500 AD (though it may have been twice this).[56]

The Bishop of Rome, called the Pope, was important since the early days of Christianity because of the martyrdom of both the apostles Peter and Paul there. The Bishops of Rome were also seen (and still are seen by Catholics) as the successors of Peter, who is considered the first Bishop of Rome. The city thus became of increasing importance as the centre of the Catholic Church.

After the Lombard invasion of Italy (569–572), the city remained nominally Byzantine, but in reality, the popes pursued a policy of equilibrium between the Byzantines, the Franks, and the Lombards.[57] In 729, the Lombard king Liutprand donated the north Latium town of Sutri to the Church, starting its temporal power.[57] In 756, Pepin the Short, after having defeated the Lombards, gave the Pope temporal jurisdiction over the Roman Duchy and the Exarchate of Ravenna, thus creating the Papal States.[57] Since this period, three powers tried to rule the city: the pope, the nobility (together with the chiefs of militias, the judges, the Senate and the populace), and the Frankish king, as king of the Lombards, patricius, and Emperor.[57] These three parties (theocratic, republican, and imperial) were a characteristic of Roman life during the entire Middle Ages.[57] On Christmas night of 800, Charlemagne was crowned in Rome as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Leo III: on that occasion, the city hosted for the first time the two powers whose struggle for control was to be a constant of the Middle Ages.[57]

In 846, Muslim Arabs unsuccessfully stormed the city’s walls, but managed to loot St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s basilica, both outside the city wall.[58] After the decay of Carolingian power, Rome fell prey to feudal chaos: several noble families fought against the pope, the emperor, and each other. These were the times of Theodora and her daughter Marozia, concubines and mothers of several popes, and of Crescentius, a powerful feudal lord, who fought against the Emperors Otto II and Otto III.[59] The scandals of this period forced the papacy to reform itself: the election of the pope was reserved to the cardinals, and reform of the clergy was attempted. The driving force behind this renewal was the monk Ildebrando da Soana, who once elected pope under the name of Gregory VII became involved into the Investiture Controversy against Emperor Henry IV.[59] Subsequently, Rome was sacked and burned by the Normans under Robert Guiscard who had entered the city in support of the Pope, then besieged in Castel Sant’Angelo.[59]

During this period, the city was autonomously ruled by a senatore or patrizio. In the 12th century, this administration, like other European cities, evolved into the commune, a new form of social organisation controlled by the new wealthy classes.[59] Pope Lucius II fought against the Roman commune, and the struggle was continued by his successor Pope Eugenius III: by this stage, the commune, allied with the aristocracy, was supported by Arnaldo da Brescia, a monk who was a religious and social reformer.[60] After the pope’s death, Arnaldo was taken prisoner by Adrianus IV, which marked the end of the commune’s autonomy.[60] Under Pope Innocent III, whose reign marked the apogee of the papacy, the commune liquidated the senate, and replaced it with a Senatore, who was subject to the pope.[60]

In this period, the papacy played a role of secular importance in Western Europe, often acting as arbitrators between Christian monarchs and exercising additional political powers.[61][62][63]

In 1266, Charles of Anjou, who was heading south to fight the Hohenstaufen on behalf of the pope, was appointed Senator. Charles founded the Sapienza, the university of Rome.[60] In that period the pope died, and the cardinals, summoned in Viterbo, could not agree on his successor. This angered the people of the city, who then unroofed the building where they met and imprisoned them until they had nominated the new pope; this marked the birth of the conclave.[60] In this period the city was also shattered by continuous fights between the aristocratic families: Annibaldi, Caetani, Colonna, Orsini, Conti, nested in their fortresses built above ancient Roman edifices, fought each other to control the papacy.[60]

Pope Boniface VIII, born Caetani, was the last pope to fight for the church’s universal domain; he proclaimed a crusade against the Colonna family and, in 1300, called for the first Jubilee of Christianity, which brought millions of pilgrims to Rome.[60] However, his hopes were crushed by the French king Philip the Fair, who took him prisoner and killed him in Anagni.[60] Afterwards, a new pope faithful to the French was elected, and the papacy was briefly relocated to Avignon (1309–1377).[64] During this period Rome was neglected, until a plebeian man, Cola di Rienzo, came to power.[64] An idealist and a lover of ancient Rome, Cola dreamed about a rebirth of the Roman Empire: after assuming power with the title of Tribuno, his reforms were rejected by the populace.[64] Forced to flee, Cola returned as part of the entourage of Cardinal Albornoz, who was charged with restoring the Church’s power in Italy.[64] Back in power for a short time, Cola was soon lynched by the populace, and Albornoz took possession of the city. In 1377, Rome became the seat of the papacy again under Gregory XI.[64] The return of the pope to Rome in that year unleashed the Western Schism (1377–1418), and for the next forty years, the city was affected by the divisions which rocked the Church.[64]

Early modern history

Almost 500 years old, this map of Rome by Mario Cartaro (from 1575) shows the city’s primary monuments.

Castel Sant’Angelo, or Hadrian’s Mausoleum, is a Roman monument radically altered in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance built in 134 AD and crowned with 16th and 17th-century statues.

In 1418, the Council of Constance settled the Western Schism, and a Roman pope, Martin V, was elected.[64] This brought to Rome a century of internal peace, which marked the beginning of the Renaissance.[64] The ruling popes until the first half of the 16th century, from Nicholas V, founder of the Vatican Library, to Pius II, humanist and literate, from Sixtus IV, a warrior pope, to Alexander VI, immoral and nepotist, from Julius II, soldier and patron, to Leo X, who gave his name to this period («the century of Leo X»), all devoted their energy to the greatness and the beauty of the Eternal City and to the patronage of the arts.[64]

During those years, the centre of the Italian Renaissance moved to Rome from Florence. Majestic works, as the new Saint Peter’s Basilica, the Sistine Chapel and Ponte Sisto (the first bridge to be built across the Tiber since antiquity, although on Roman foundations) were created. To accomplish that, the Popes engaged the best artists of the time, including Michelangelo, Perugino, Raphael, Ghirlandaio, Luca Signorelli, Botticelli, and Cosimo Rosselli.

The period was also infamous for papal corruption, with many Popes fathering children, and engaging in nepotism and simony. The corruption of the Popes and the huge expenses for their building projects led, in part, to the Reformation and, in turn, the Counter-Reformation. Under extravagant and rich popes, Rome was transformed into a centre of art, poetry, music, literature, education and culture. Rome became able to compete with other major European cities of the time in terms of wealth, grandeur, the arts, learning and architecture.

The Renaissance period changed the face of Rome dramatically, with works like the Pietà by Michelangelo and the frescoes of the Borgia Apartments. Rome reached the highest point of splendour under Pope Julius II (1503–1513) and his successors Leo X and Clement VII, both members of the Medici family.

In this twenty-year period, Rome became one of the greatest centres of art in the world. The old St. Peter’s Basilica built by Emperor Constantine the Great[65] (which by then was in a dilapidated state) was demolished and a new one begun. The city hosted artists like Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli and Bramante, who built the temple of San Pietro in Montorio and planned a great project to renovate the Vatican. Raphael, who in Rome became one of the most famous painters of Italy, created frescoes in the Villa Farnesina, the Raphael’s Rooms, plus many other famous paintings. Michelangelo started the decoration of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and executed the famous statue of the Moses for the tomb of Julius II.

Its economy was rich, with the presence of several Tuscan bankers, including Agostino Chigi, who was a friend of Raphael and a patron of arts. Before his early death, Raphael also promoted for the first time the preservation of the ancient ruins. The War of the League of Cognac caused the first plunder of the city in more than five hundred years since the previous sack; in 1527, the Landsknechts of Emperor Charles V sacked the city, bringing an abrupt end to the golden age of the Renaissance in Rome.[64]

Beginning with the Council of Trent in 1545, the Church began the Counter-Reformation in response to the Reformation, a large-scale questioning of the Church’s authority on spiritual matters and governmental affairs. This loss of confidence led to major shifts of power away from the Church.[64] Under the popes from Pius IV to Sixtus V, Rome became the centre of a reformed Catholicism and saw the building of new monuments which celebrated the papacy.[66] The popes and cardinals of the 17th and early 18th centuries continued the movement by having the city’s landscape enriched with baroque buildings.[66]

This was another nepotistic age; the new aristocratic families (Barberini, Pamphili, Chigi, Rospigliosi, Altieri, Odescalchi) were protected by their respective popes, who built huge baroque buildings for their relatives.[66] During the Age of Enlightenment, new ideas reached the Eternal City, where the papacy supported archaeological studies and improved the people’s welfare.[64] But not everything went well for the Church during the Counter-Reformation. There were setbacks in the attempts to assert the Church’s power, a notable example being in 1773 when Pope Clement XIV was forced by secular powers to have the Jesuit order suppressed.[64]

Late modern and contemporary

The rule of the Popes was interrupted by the short-lived Roman Republic (1798–1800), which was established under the influence of the French Revolution. The Papal States were restored in June 1800, but during Napoleon’s reign Rome was annexed as a Département of the French Empire: first as Département du Tibre (1808–1810) and then as Département Rome (1810–1814). After the fall of Napoleon, the Papal States were reconstituted by a decision of the Congress of Vienna of 1814.

In 1849, a second Roman Republic was proclaimed during a year of revolutions in 1848. Two of the most influential figures of the Italian unification, Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, fought for the short-lived republic.

Rome then became the focus of hopes of Italian reunification after the rest of Italy was united as the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 with the temporary capital in Florence. That year Rome was declared the capital of Italy even though it was still under the Pope’s control. During the 1860s, the last vestiges of the Papal States were under French protection thanks to the foreign policy of Napoleon III. French troops were stationed in the region under Papal control. In 1870 the French troops were withdrawn due to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. Italian troops were able to capture Rome entering the city through a breach near Porta Pia. Pope Pius IX declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican. In 1871 the capital of Italy was moved from Florence to Rome.[67] In 1870 the population of the city was 212,000, all of whom lived with the area circumscribed by the ancient city, and in 1920, the population was 660,000. A significant portion lived outside the walls in the north and across the Tiber in the Vatican area.

Bombardment of Rome by Allied planes, 1943

Soon after World War I in late 1922 Rome witnessed the rise of Italian Fascism led by Benito Mussolini, who led a march on the city. He did away with democracy by 1926, eventually declaring a new Italian Empire and allying Italy with Nazi Germany in 1938. Mussolini demolished fairly large parts of the city centre in order to build wide avenues and squares which were supposed to celebrate the fascist regime and the resurgence and glorification of classical Rome.[68] The interwar period saw a rapid growth in the city’s population which surpassed one million inhabitants soon after 1930. During World War II, due to the art treasuries and the presence of the Vatican, Rome largely escaped the tragic destiny of other European cities. However, on 19 July 1943, the San Lorenzo district was subject to Allied bombing raids, resulting in about 3,000 fatalities and 11,000 injuries, of whom another 1,500 died.[69] Mussolini was arrested on 25 July 1943. On the date of the Italian Armistice 8 September 1943 the city was occupied by the Germans. The Pope declared Rome an open city. It was liberated on 4 June 1944.

Rome developed greatly after the war as part of the «Italian economic miracle» of post-war reconstruction and modernisation in the 1950s and early 1960s. During this period, the years of la dolce vita («the sweet life»), Rome became a fashionable city, with popular classic films such as Ben Hur, Quo Vadis, Roman Holiday and La Dolce Vita filmed in the city’s iconic Cinecittà Studios. The rising trend in population growth continued until the mid-1980s when the comune had more than 2.8 million residents. After this, the population declined slowly as people began to move to nearby suburbs.

Government

Local government

Rome constitutes a comune speciale, named «Roma Capitale»,[70] and is the largest both in terms of land area and population among the 8,101 comuni of Italy. It is governed by a mayor and a city council. The seat of the comune is the Palazzo Senatorio on the Capitoline Hill, the historic seat of the city government. The local administration in Rome is commonly referred to as «Campidoglio», the Italian name of the hill.

Administrative and historical subdivisions

Since 1972, the city has been divided into administrative areas, called municipi (sing. municipio) (until 2001 named circoscrizioni).[71] They were created for administrative reasons to increase decentralisation in the city. Each municipio is governed by a president and a council of twenty-five members who are elected by its residents every five years. The municipi frequently cross the boundaries of the traditional, non-administrative divisions of the city. The municipi were originally 20, then 19,[72] and in 2013, their number was reduced to 15.[73]

Rome is also divided into differing types of non-administrative units. The historic centre is divided into 22 rioni, all of which are located within the Aurelian Walls except Prati and Borgo. These originate from the 14 regions of Augustan Rome, which evolved in the Middle Ages into the medieval rioni.[74] In the Renaissance, under Pope Sixtus V, they again reached fourteen, and their boundaries were finally defined under Pope Benedict XIV in 1743.

A new subdivision of the city under Napoleon was ephemeral, and there were no serious changes in the organisation of the city until 1870 when Rome became the third capital of Italy. The needs of the new capital led to an explosion both in the urbanisation and in the population within and outside the Aurelian walls. In 1874, a fifteenth rione, Esquilino, was created on the newly urbanised zone of Monti. At the beginning of the 20th century other rioni were created (the last one was Prati – the only one outside the Walls of Pope Urban VIII – in 1921). Afterwards, for the new administrative subdivisions of the city, the term «quartiere» was used. Today all the rioni are part of the first Municipio, which therefore coincides completely with the historical city (Centro Storico).

Metropolitan and regional government

Rome is the principal town of the Metropolitan City of Rome, operative since 1 January 2015. The Metropolitan City replaced the old provincia di Roma, which included the city’s metropolitan area and extends further north until Civitavecchia. The Metropolitan City of Rome is the largest by area in Italy. At 5,352 km2 (2,066 sq mi), its dimensions are comparable to the region of Liguria. Moreover, the city is also the capital of the Lazio region.[75]

National government

Rome is the national capital of Italy and is the seat of the Italian Government. The official residences of the President of the Italian Republic and the Italian Prime Minister, the seats of both houses of the Italian Parliament and that of the Italian Constitutional Court are located in the historic centre. The state ministries are spread out around the city; these include the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is located in Palazzo della Farnesina near the Olympic stadium.

Geography

Location

Rome is in the Lazio region of central Italy on the Tiber (Italian: Tevere) river. The original settlement developed on hills that faced onto a ford beside the Tiber Island, the only natural ford of the river in this area. The Rome of the Kings was built on seven hills: the Aventine Hill, the Caelian Hill, the Capitoline Hill, the Esquiline Hill, the Palatine Hill, the Quirinal Hill, and the Viminal Hill. Modern Rome is also crossed by another river, the Aniene, which flows into the Tiber north of the historic centre.

Although the city centre is about 24 km (15 mi) inland from the Tyrrhenian Sea, the city territory extends to the shore, where the south-western district of Ostia is located. The altitude of the central part of Rome ranges from 13 m (43 ft) above sea level (at the base of the Pantheon) to 139 m (456 ft) above sea level (the peak of Monte Mario).[76] The Comune of Rome covers an overall area of about 1,285 km2 (496 sq mi), including many green areas.

Topography

Throughout the history of Rome, the urban limits of the city were considered to be the area within the city’s walls. Originally, these consisted of the Servian Wall, which was built twelve years after the Gaulish sack of the city in 390 BC. This contained most of the Esquiline and Caelian hills, as well as the whole of the other five. Rome outgrew the Servian Wall, but no more walls were constructed until almost 700 years later, when, in 270 AD, Emperor Aurelian began building the Aurelian Walls. These were almost 19 km (12 mi) long, and were still the walls the troops of the Kingdom of Italy had to breach to enter the city in 1870. The city’s urban area is cut in two by its ring-road, the Grande Raccordo Anulare («GRA»), finished in 1962, which circles the city centre at a distance of about 10 km (6 mi). Although when the ring was completed most parts of the inhabited area lay inside it (one of the few exceptions was the former village of Ostia, which lies along the Tyrrhenian coast), in the meantime quarters have been built which extend up to 20 km (12 mi) beyond it.[citation needed]

The comune covers an area roughly three times the total area within the Raccordo and is comparable in area to the entire metropolitan cities of Milan and Naples, and to an area six times the size of the territory of these cities. It also includes considerable areas of abandoned marshland which is suitable neither for agriculture nor for urban development.[citation needed]

As a consequence, the density of the comune is not that high, its territory being divided between highly urbanised areas and areas designated as parks, nature reserves, and for agricultural use.[citation needed]

Climate

Rome has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa),[77] with hot, dry summers and mild, humid winters.

Its average annual temperature is above 21 °C (70 °F) during the day and 9 °C (48 °F) at night. In the coldest month, January, the average temperature is 12.6 °C (54.7 °F) during the day and 2.1 °C (35.8 °F) at night. In the warmest month, August, the average temperature is 31.7 °C (89.1 °F) during the day and 17.3 °C (63.1 °F) at night.

December, January and February are the coldest months, with a daily mean temperature of approximately 8 °C (46 °F). Temperatures during these months generally vary between 10 and 15 °C (50 and 59 °F) during the day and between 3 and 5 °C (37 and 41 °F) at night, with colder or warmer spells occurring frequently. Snowfall is rare but not unheard of, with light snow or flurries occurring on some winters, generally without accumulation, and major snowfalls on a very rare occurrence (the most recent ones were in 2018, 2012 and 1986).[78][79][80]

The average relative humidity is 75%, varying from 72% in July to 77% in November. Sea temperatures vary from a low of 13.9 °C (57.0 °F) in February to a high of 25.0 °C (77.0 °F) in August.[81]

| Climate data for Rome Urbe Airport (altitude: 24 m sl, 7 km north from Colosseum satellite view) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

33.1 (91.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.0 (104.0) |

39.6 (103.3) |

37.6 (99.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.7 (89.1) |

27.5 (81.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |