Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

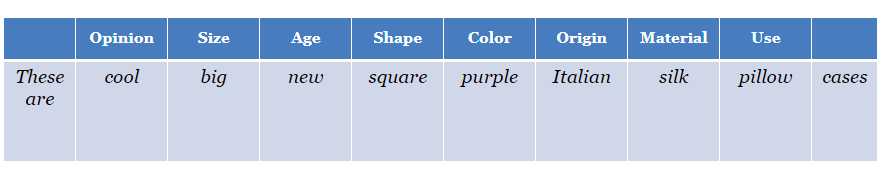

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper

Statements, or declarative sentences, can be in the form of simple, compound, or complex sentences.

This article describes standard word order in simple declarative sentences. Word order in compound sentences and complex sentences is described in Basic Word Order and Word Order in Complex Sentences in the section Grammar. Examples comparing standard word order and inverted word order can be found in Inversion in the section Miscellany.

Statements in the form of simple sentences are divided into unextended sentences and extended sentences. There are five parts of a sentence: the subject, the predicate, the object, the attribute, the adverbial modifier. The rules of word order indicate where their place in the sentence is.

Word order in simple unextended sentences

Standard word order in simple unextended declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE.

Anna teaches.

Time flies.

We are reading.

He will understand.

Word order in simple extended sentences

Standard word order in simple extended declarative sentences is SUBJECT + PREDICATE + object + adverbial modifier.

Anna teaches mathematics.

Tom has returned my books.

We are reading a story now.

He will understand it later.

Adverbial modifiers are normally placed at the end of the sentence after the object (or after the verb, if there is no object). Attributes (adjectives, numerals, pronouns) usually stand before their nouns, and attributes in the form of nouns with prepositions are placed after their nouns.

Anna has classes on the second floor.

Tom has worked here for ten years.

He wrote two interesting articles about football.

The place of the subject

The subject is placed at the beginning of the sentence and is usually expressed by a noun or a pronoun. The subject group may include an article and an attribute.

Monkeys like bananas.

He writes short stories.

That student is from Rome.

Tom and Anna live in Boston.

His little son is learning to read.

The subject is placed after the verb in the structure «there is, there are» which is used when you want to say WHAT is in some place.

There is a table in the room.

There are two books on the table.

There was a car in front of the house.

The place of the predicate

The predicate stands after the subject and is usually represented by a main verb or by the combination of an auxiliary or modal verb with a main verb. Negative forms of auxiliary verbs can be full or contracted.

She likes chocolate.

I work at a small hotel.

The children are reading and writing new words.

She does not know him.

He hasn’t bought a car yet.

You shouldn’t do it.

We are not going to buy a new house this summer.

The verb «be» as a linking verb may be followed by a noun, an adjective, a numeral, or a pronoun as part of the predicate. (The use of the verb «be» is described in The Verb BE in the section Grammar.)

I am a teacher.

Tom is young.

The tea is too hot.

She was twenty.

He isn’t a doctor.

This isn’t she.

The place of the object

There are direct objects (without a preposition) and indirect objects (with or without a preposition). The object is placed after the main verb. If there are two objects after the verb, the word order is first the direct object, then the object with preposition.

Tom collects stamps.

He likes reading.

He likes to read.

He is waiting for a bus.

She gave two books to her brother.

Liz asked the boy about his father.

She made soup, salad, and roast beef for dinner.

Some transitive verbs (for example, bring, give, offer, sell, send, show, tell) are often followed by two objects without prepositions. In this case, the order after the verb is first the indirect object (without a preposition), then the direct object. Examples:

She gave him two books.

They offered me a good job.

He sent her a present.

The teacher told the students a story.

The place of the attribute

Attributes expressed by adjectives (or by pronouns, participles, numerals, nouns in the possessive case) usually stand before their nouns, i.e., before the noun in the subject, in the object, or in the adverbial modifier. Examples:

A good writer should know many things.

My old dog liked fresh apples.

We threw out several broken chairs.

Four students passed that difficult test.

The doctor’s new house is near a large park.

If there are several adjectives before a noun, a more specific adjective is placed closer to its noun than a more general adjective.

She bought a green sweater.

She bought a nice green woolen sweater.

Chicago is a big city.

Chicago is a beautiful big clean city.

My daughter likes soft blue, gray, and green colors.

My daughter likes soft gray, green, and blue colors.

Attributes in the form of a noun with a preposition or structures with participles are placed after the noun that they modify.

She bought a silk blouse with long sleeves.

Chicago is a big city in the Midwest.

I took the bus going through Springfield.

The waiter threw out the chairs broken in yesterday’s fight.

The place of the adverbial modifier

Adverbial modifiers of place, time, frequency, manner are often expressed by adverbs or by nouns with prepositions and are placed at the end of the sentence after the main verb or after the object if there is an object.

Adverbial modifiers of place

They live on Main Street.

The bedrooms are upstairs.

I went across the bridge.

She has to go to the bank.

They spent their vacation at the lake.

Adverbial modifiers of time

I’m going to see him tomorrow.

I spoke to him an hour ago.

He saw her before leaving.

I went to work after class.

She was sick yesterday.

The meeting was at ten o’clock last Friday.

Adverbial modifiers of frequency

She visits them sometimes.

They go to concerts often.

He calls her every day.

He writes to her regularly.

She goes shopping once or twice a week.

Adverbial modifiers of manner

He drives very fast.

He closed the door slowly.

He ate the food hungrily.

We came here by train.

He opened the door with a key.

Peculiarities of the position of adverbial modifiers

Adverbial modifiers consisting of two or more words are placed at the end of the sentence after the main verb (or after the object, if any). Possible positions of adverbial modifiers of time and frequency consisting of one word are described below.

One-word adverbs of frequency

One-word adverbs of frequency «often, frequently, rarely, regularly, sometimes» are often placed between the subject and the main verb in the simple tenses but may also be placed after the main verb (or after the object, if any).

He often goes to the park.

He goes to the park often.

We rarely buy food in that store.

He frequently visited them last year.

He visited them frequently last year.

Adverbs of frequency «usually, always, never, seldom» are placed between the subject and the main verb in the simple tenses but are usually placed after the verb «be».

They seldom talk about it.

She usually buys bread, cheese, and milk in this grocery store.

He always asks me this question.

He is always late.

He is never home before seven.

One-word adverbs of time

One-word adverbs of time «already, just, never, ever» are placed between the two parts of the predicate in the perfect tenses, though «already» can also stand after the main verb.

She has already left.

She has left already.

She has just called me.

I have never been to Mexico.

Have you ever seen this film?

They had already left for London by the time he arrived in Paris.

If there are two auxiliary verbs in a tense form, the adverb is usually placed after the first auxiliary verb. «Already» may also stand after the second auxiliary verb, for example, in the Future Perfect.

He has never been asked such questions.

He may already have called them.

His plane will already have landed by the time we get to the airport.

He will have already left for London by Friday.

Some one-word adverbs of time or frequency, for example, «today, tomorrow, yesterday, sometimes, usually», are sometimes placed at the beginning of the sentence before the subject (usually for emphasis).

Yesterday I talked to Jim.

Tomorrow we are leaving.

Suddenly the rain started.

Sometimes she stays at this hotel for a few days.

Usually, she has a cheese sandwich in the morning, but today she is eating scrambled eggs for breakfast.

Two-word adverbial modifiers

Two-word adverbs and adverbial modifiers with prepositions are placed at the end of the sentence after the verb (or after the object, if any). If there are several adverbial modifiers, the adverbial modifier of place is usually placed before the adverbial modifier of time.

They stayed in his house for about an hour.

Professor Benson usually has two classes at the university every day.

My new neighbors often read a good book in their garden after breakfast.

He arrived in Vienna by train at 7:00 a.m. on Thursday.

Порядок слов в повествовательных предложениях

Повествовательные предложения могут быть в виде простых, сложносочиненных или сложноподчиненных предложений.

Эта статья описывает стандартный порядок слов в простых повествовательных предложениях. Порядок слов в сложносочиненных и сложноподчиненных предложениях описан в статьях «Basic Word Order» и «Word Order in Complex Sentences» в разделе Grammar. Примеры, сравнивающие стандартный и обратный порядок слов, можно найти в статье «Inversion» в разделе Miscellany.

Простые повествовательные предложения делятся на нераспространенные предложения и распространенные предложения. Есть пять членов предложения: подлежащее, сказуемое, дополнение, определение, обстоятельство. Правила порядка слов указывают, где их место в предложении.

Порядок слов в простых нераспространенных предложениях

Стандартный порядок слов в простых нераспространенных повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое.

Анна преподает.

Время летит.

Мы читаем.

Он поймет.

Порядок слов в простых распространенных предложениях

Стандартный порядок слов в простых распространенных повествовательных предложениях: подлежащее + сказуемое + дополнение + обстоятельство.

Анна преподает математику.

Том вернул мои книги.

Мы читаем рассказ сейчас.

Он поймет это позже.

Обстоятельства обычно ставятся в конце предложения после дополнения (или после глагола, если дополнения нет). Определения (прилагательные, числительные, местоимения) обычно стоят перед своими существительными, а определения в форме существительных с предлогами ставятся после своих существительных.

У Анны занятия на втором этаже.

Том проработал здесь десять лет.

Он написал две интересные статьи о футболе.

Место подлежащего

Подлежащее ставится в начале предложения и обычно выражено существительным или местоимением. Группа подлежащего может включать артикль и определение.

Обезьяны любят бананы.

Он пишет короткие рассказы.

Тот студент – из Рима.

Том и Анна живут в Бостоне.

Его маленький сын учится читать.

Подлежащее ставится после глагола в конструкции «there is, there are», которая употребляется, когда вы хотите сказать, ЧТО именно находится в каком-то месте.

В комнате (находится) стол.

На столе (есть) две книги.

Перед домом был автомобиль.

Место сказуемого

Сказуемое стоит за подлежащим и обычно представлено основным глаголом или комбинацией вспомогательного или модального глагола с основным глаголом. Отрицательные формы вспомогательных глаголов могут быть полными или сокращенными.

Она любит шоколад.

Я работаю в маленькой гостинице.

Дети читают и пишут новые слова.

Она не знает его.

Он еще не купил машину.

Вам не следует этого делать.

Мы не собираемся покупать новый дом этим летом.

За глаголом «be» как за глаголом-связкой может следовать существительное, прилагательное, числительное или местоимение как часть сказуемого. (Употребление глагола «be» описано в статье «The Verb BE» в разделе Grammar.)

Я (есть) учитель.

Том молодой.

Чай слишком горячий.

Ей было двадцать.

Он не врач.

Это не она.

Место дополнения

Есть прямые дополнения (без предлога) и косвенные дополнения (с предлогом или без предлога). Дополнение ставится после основного глагола. Если есть два дополнения после глагола, порядок слов такой: сначала идет прямое дополнение, затем дополнение с предлогом.

Том собирает марки.

Он любит чтение.

Он любит читать.

Он ждет автобус.

Она дала две книги своему брату.

Лиз спросила мальчика о его отце.

Она приготовила суп, салат и ростбиф на обед.

За некоторыми переходными глаголами (например, принести, дать, предложить, продать, послать, показать, рассказать) часто следуют два дополнения без предлогов. В этом случае после глагола сначала идет косвенное дополнение (без предлога), а затем прямое дополнение. Примеры:

Она дала ему две книги.

Они предложили мне хорошую работу.

Он послал ей подарок.

Учитель рассказал студентам историю.

Место определения

Определения, выраженные прилагательными (или местоимениями, причастиями, числительными, существительными в притяжательном падеже), обычно стоят перед своими существительными, т.е. перед существительным в подлежащем, дополнении или обстоятельстве. Примеры:

Хороший писатель должен знать много вещей.

Моя старая собака любила свежие яблоки.

Мы выбросили несколько сломанных стульев.

Четыре студента сдали тот трудный тест.

Новый дом доктора находится возле большого парка.

Если есть несколько прилагательных перед существительным, более конкретизирующее прилагательное ставится ближе к своему существительному, чем более общее.

Она купила зеленый свитер.

Она купила хороший зеленый шерстяной свитер.

Чикаго большой город.

Чикаго красивый большой чистый город.

Моя дочь любит мягкие голубые, серые и зеленые цвета.

Моя дочь любит мягкие серые, зеленые и голубые цвета.

Определения в виде существительного с предлогом или конструкции с причастиями ставятся после существительного, которое они определяют.

Она купила шелковую блузку с длинными рукавами.

Чикаго большой город на Среднем Западе.

Я сел на автобус, идущий через Спрингфилд.

Официант выбросил стулья, сломанные во вчерашней драке.

Место обстоятельства

Обстоятельства места, времени, частоты действия, образа действия часто выражены наречиями или существительными с предлогами и ставятся в конце предложения после основного глагола или после дополнения, если есть дополнение.

Обстоятельства места

Они живут на Главной улице.

Спальни наверху.

Я перешел через мост.

Она должна пойти в банк.

Они провели свой отпуск у озера.

Обстоятельства времени

Я собираюсь увидеться с ним завтра.

Я говорил с ним час назад.

Он виделся с ней перед уходом.

Я пошел на работу после занятия.

Она была больна вчера.

Собрание было в десять часов в прошлую пятницу.

Обстоятельства частоты действия

Она их навещает иногда.

Они ходят на концерты часто.

Он звонит ей каждый день.

Он пишет ей регулярно.

Она ходит за покупками раз или два в неделю.

Обстоятельства образа действия

Он водит (машину) очень быстро.

Он закрыл дверь медленно.

Он с жадностью съел еду.

Мы приехали сюда поездом.

Он открыл дверь ключом.

Особенности расположения обстоятельств

Обстоятельства, состоящие из двух и более слов, ставятся в конце предложения после основного глагола (или после дополнения, если оно есть). Возможные варианты расположения обстоятельств времени и частоты действия, состоящих из одного слова, описаны ниже.

Наречия частоты действия из одного слова

Состоящие из одного слова наречия частоты действия «often, frequently, rarely, regularly, sometimes» часто ставятся между подлежащим и основным глаголом в простых временах, но могут также размещаться после основного глагола (или после дополнения, если оно есть).

Он часто ходит в парк.

Он ходит в парк часто.

Мы редко покупаем еду в том магазине.

Он часто навещал их в прошлом году.

Он навещал их часто в прошлом году.

Наречия частоты действия «usually, always, never, seldom» ставятся между подлежащим и основным глаголом в простых временах, но обычно ставятся после глагола «be».

Они редко говорят об этом.

Она обычно покупает хлеб, сыр и молоко в этом продуктовом магазине.

Он всегда задает мне этот вопрос.

Он всегда опаздывает.

Его никогда нет дома раньше семи.

Наречия времени из одного слова

Состоящие из одного слова наречия времени «already, just, never, ever» ставятся между двумя частями сказуемого в перфектных временах, хотя «already» может также стоять после основного глагола.

Она уже уехала.

Она уехала уже.

Она только что мне звонила.

Я никогда не бывал в Мексике.

Вы когда-либо видели этот фильм?

Они уже уехали в Лондон к тому времени, как он прибыл в Париж.

Если во временной форме два вспомогательных глагола, наречие обычно ставится после первого. «Already» может также стоять после второго вспомогательного глагола, например, во времени Future Perfect.

Ему никогда не задавали таких вопросов.

Он, возможно, уже позвонил им.

Его самолет уже приземлится к тому времени, как мы доберемся до аэропорта.

Он уже уедет в Лондон к пятнице.

Некоторые состоящие из одного слова наречия времени и частоты действия, например, «today, tomorrow, yesterday, sometimes, usually», иногда ставятся в начале предложения перед подлежащим (обычно для эмфатического выделения).

Вчера я поговорил с Джимом.

Завтра мы уезжаем.

Неожиданно начался дождь.

Иногда она останавливается в этой гостинице на несколько дней.

Обычно она ест бутерброд с сыром утром, но сегодня она ест яичницу на завтрак.

Обстоятельства из двух слов

Наречия из двух слов и обстоятельства с предлогами ставятся в конце предложения после глагола (или после дополнения, если оно есть). Если есть несколько обстоятельств, то обстоятельство места обычно ставится впереди обстоятельства времени.

Они оставались в его доме примерно час.

Профессор Бенсон обычно имеет два занятия в университете каждый день.

Мои новые соседи часто читают хорошую книгу в своем саду после завтрака.

Он приехал в Вену поездом в семь часов утра в четверг.

Порядок слов в английском меняется редко: каждый член предложения находится на своём месте. Если переставить слова местами, носитель языка может тебя не понять. Рассказываем, как запомнить порядок слов в английском, что такое инверсия и зачем её использовать. А также дарим промокод на интенсив по лексике и разговорному английскому.

Чтобы понять, как устроен порядок слов в английском, вспомним, из чего состоит предложение.

Члены предложения в английском

Как и в русском языке, предложение в английском состоит из главных и второстепенных членов.

Главные члены предложения

- Subject (Подлежащее)

Субъект, который выполняет действие. Отвечает на вопрос Who? (Кто?) или What? (Что?).

The dog barks. — Собака лает. (the dog — подлежащее)

- Predicate (Сказуемое)

Обозначает действие, которое выполняет субъект. Выражено глаголом или глагольными конструкциями.

The dog barks. — Собака лает. (barks — сказуемое)

Второстепенные члены предложения

- Object (Дополнение)

Объект, на который направлено действие. Дополнение в английском бывает direct (прямым), indirect (косвенным беспредложным) и prepositional (косвенным предложным).

| Direct object (Прямое дополнение) | Indirect object (Непрямое дополнение) | Prepositional Object (Косвенное дополнение) |

| Whom? (Кого?) What? (Что?) | To whom? (Кому?) | About whom? (О ком?) About what? (О чём?) With whom? (С кем?) For whom? (Для кого?). |

The dog barks at me. — Собака лает на меня. (at me — косвенное дополнение)

- Attribute (Определение)

Характеристика подлежащего или дополнения. Отвечает на вопросы What? (Какой?), What kind? (Какого типа?), Which one? (Который?).

The small dog barks. — Маленькая собака лает. (small — определение)

- Adverbial modifier (Обстоятельство)

Указывает на признак, причину, время и место действия. Отвечает на вопросы When? (Когда?), How? (Как?), Where? (Где?), Why? (Почему?).

The dog barks outside. — Собака лает снаружи. (outside — обстоятельство)

В отличие от русского языка, где нет строго закреплённой позиции у того или иного слова, в английском каждому члену предложения отведено своё место. Переставлять их нельзя, потому что изменится смысл. Сравни:

Mary likes John very much. — Мэри очень нравится Джон.

John likes Mary very much. — Джону очень нравится Мэри.

Мы поменяли местами подлежащее Mary и дополнение John, и смысл предложения кардинально изменился. Поэтому запомни:

Порядок слов в английских предложениях строгий и фиксированный.

Ниже найдёшь правила и таблицы, по которым легко сможешь правильно построить предложение в английском.

Типичный порядок слов

Порядок слов в утвердительных предложениях

Обычный порядок слов в английском языке выглядит так:

Subject — Predicate (Verb) — Object

Сначала идёт подлежащее, потом сказуемое, затем дополнение. Это называется direct word order (прямой порядок слов).

The girl got the flowers. — Девушка получила цветы.

При этом, если к подлежащему относится определение, оно ставится перед ним.

The beautiful girl got the flowers. — Красивая девушка получила цветы.

Всё усложняется, если в предложении есть несколько дополнений и обстоятельств. В этом случае нужно чётко определить их вид и расположить согласно таблице:

I gave my mother the flowers with pleasure at home yesterday. — Вчера дома я с удовольствием подарил маме цветы.*

I gave the flowers to my mother. — Я подарил цветы маме.

Five minutes ago I gave the flowers to my mother with pleasure at home. — Пять минут назад дома я с удовольствием подарил цветы маме.

* Порядок слов при переводе на русский может отличаться от английского.

Обрати внимание, что обстоятельства времени или места могут стоять как в начале, так и в конце предложения.

Yesterday, he wrote a poem. — Вчера он написал стихотворение.

He wrote a poem yesterday. — Он написал стихотворение вчера.

Место прилагательных в предложении

По правилам английского, прилагательное ставится перед существительным, к которому относится. Если прилагательных больше, чем одно, их порядок определяется следующим образом:

These are cool big new square purple Italian silk pillow cases. — Это классные большие новые квадратные фиолетовые итальянские шёлковые наволочки для подушек. (pillow cases дословно — подушечные наволочки)

Место наречий в предложении

Общее правило: наречие в английском идёт после глагола, но перед прилагательным или другим наречием.

Mike acts quickly when I ask him to help. Mike is a very brave man. — Майк быстро реагирует, когда я прошу помощи. Майк очень смелый человек.

Существуют также особые правила для конкретного типа наречий.

- Наречия частоты идут перед глаголами.

My sister sometimes has her nails done by herself. — Моя сестра иногда сама делает себе маникюр.

- Наречия степени ставятся перед главными глаголами, но после вспомогательных.

I totally get what you mean. — Я точно понял, что ты имел в виду.

I don’t really get what you mean. — Я не совсем понял, что ты имел в виду.

- Наречия места и времени обычно идут в конце предложения.

Mike will be here at 6 pm. — Майк будет здесь в шесть вечера.

- Наречия, которые относятся ко всему предложению, идут в начале.

Unfortunately I cannot come to you party. — К сожалению, я не смогу прийти на твою вечеринку.

Если в предложении несколько наречий, они расставляются по правилу:

наречие образа действия — наречие места — наречие времени

She looked prettily in her new dress that day. — Она выглядела мило в новом платье в тот день.

Если в предложении есть глагол движения (to go, to come, to leave), наречия идут так:

наречие места — наречие образа действия — наречие времени.

He left for Paris suddenly yesterday. — Вчера он внезапно уехал в Париж.

Порядок слов в отрицательных предложениях

В отрицательных предложениях сохраняется прямой порядок слов Subject — Predicate (Verb) — Object, а частица not ставится после вспомогательного глагола.

The girl did not get the flowers. — Девушка не получила цветы.

At the moment, I do not have my phone. — Сейчас у меня нет с собой телефона.

Порядок слов в вопросительных предложениях

Вопросительные предложения в английском строятся по следующим правилам:

- В общих вопросах вспомогательный (to have, to be, to do) или модальный глагол ставится перед подлежащим, далее сохраняется прямой порядок слов.

Can I take your book? — Могу я взять твою книгу?

Do you have a book? — У тебя есть книга?

Is it your book? — Это твоя книга?

- Вопросительное слово всегда ставится в начале.

Why do you have that book? — Почему у тебя есть та книга?

- В вопросах к определению любого члена предложения за вопросительным словом ставится существительное.

What book do you have? — Какая у тебя есть книга?

- Если вопросительное слово идёт с предлогом, тот ставится после сказуемого. Если в вопросе есть дополнение, предлог ставится после него.

What are you reading about? — О чём читаешь?

Если ты уже очумел от непонятных правил и грамматических конструкций, набил шишек на временах и предлогах, пришло время разобраться с английской грамматикой раз и навсегда. Наши пособия «Grammar Is All You Need» и «12-in-1 Tenses Handbook» тебе в этом помогут. В них нет никаких занудных правил и сложных примеров, всё чётко и по фану!

Нетипичный порядок слов в английском

Когда мы хотим сделать акцент в предложении на определённой идее или добавить ей эмоциональности, можно нарушить прямой порядок слов и применить инверсию (Inversion). Это значит — поменять местами подлежащее и сказуемое.

Самый простой пример инверсии в английском — это вопросительные предложения. О них мы рассказали выше. Но существуют и более сложные случаи её употребления.

Тему инверсии обычно проходят на уровне Upper-Intermediate. Чтобы определить свой уровень английского, пройди наш короткий тест.

Наречия отрицания

Если в предложении есть наречия never (никогда), seldom (изредка), rarely (редко), scarcely (вряд ли), hardly (едва), in vain (напрасно), no sooner (не раньше), можно применить инверсию, чтобы эмоционально усилить отрицание.

Сравни:

They had never been to New York. — Они никогда не были в Нью-Йорке.

Never had they been to New York. — Никогда они не были в Нью-Йорке.

У этих двух предложений один и тот же смысл, только второй вариант на английском звучит выразительнее. Образуется такая инверсия по схеме:

Adverb — Auxiliary Verb — Subject — Verb

Seldom can he visit his grandparents. — Изредка он может навещать своих дедушку и бабушку.

Rarely does it snow in Africa. — Редко бывает, что снег идёт в Африке.

Это же правило относится и к наречию little с отрицательным значением.

Little did they know what to do. — Они совсем не знали, что делать.

Наречия с not

Если предложение начинается с not since (с тех пор как, ни разу), not till/until (пока не), инверсия происходит в главном предложении.

Not till I called him did I calm down. — Пока я ему не позвонил, я не успокоился.

Устойчивые выражения с no

В английском инверсию можно применять в предложениях с выражениями on no account (ни в коем случае), under no circumstances (ни при каких обстоятельствах), in no way (никоим образом), at no time (никогда).

Under no circumstances should you go outside. — Ни при каких обстоятельствах не выходи на улицу.

In no way did he want to hurt you. — Никоим образом он не хотел тебя обидеть.

Only

Также инверсия в английском используется в предложениях после указателей времени со словом only (только).

Only once before have I lost my keys. — Лишь однажды я терял свои ключи.

Only when he left did I remember about present to him. — Только когда он ушёл, я вспомнил про подарок для него.

Here и there

Инверсия может применяться после слов here (вот, здесь, тут) и there (там), когда они являются обстоятельством места, а подлежащее выражено существительным.

Here comes the sun! — Вот выходит солнце!

I looked back and there stood Benjamin, all covered in paint. — Я оглянулся, и там стоял Бенджамин, весь перемазанный в краске.

Если подлежащее выражено местоимением, это правило не работает.

Here are we. Here we are. — Вот и мы.

So.. that, such… that

Подчеркнуть чьё-либо качество можно также с помощью инверсии.

She was so beautiful that I couldn’t take my eyes off. — Она была настолько красивой, что я не мог отвести глаз.

Инверсия: So beautiful was she that I couldn’t take my eyes off.

Условные предложения

Инверсию можно использовать во всех типах условных предложений, кроме нулевого. Для этого следует убрать if (если) и вынести в начало предложения вспомогательный глагол. Как образуются условные наклонения, сколько их и чем они отличаются, объяснили на примерах из фильма «Джокер».

Should you have any questions, feel free to contact me. — Если у вас будут вопросы, свяжитесь со мной.

Хочешь научиться свободно использовать инверсию в своей речи, а также научиться увлекательно излагать свои мысли и рассказывать истории? Записывайся на интенсив «Думай и говори как носитель» с Веней Паком и Тикеей Дей. По промокоду HERECOMES тебя ждёт скидка в 10 $ на любой тариф курса.

Что почитать:

Современные учебники английского для самостоятельного изучения языка

Таблица неправильных глаголов в английском и советы по их изучению

Словообразование в английском: таблица английских суффиксов и префиксов

Как выучить все английские времена

План по совершенствованию английского: пять простых шагов

Тайм-менеджмент в изучении английского языка

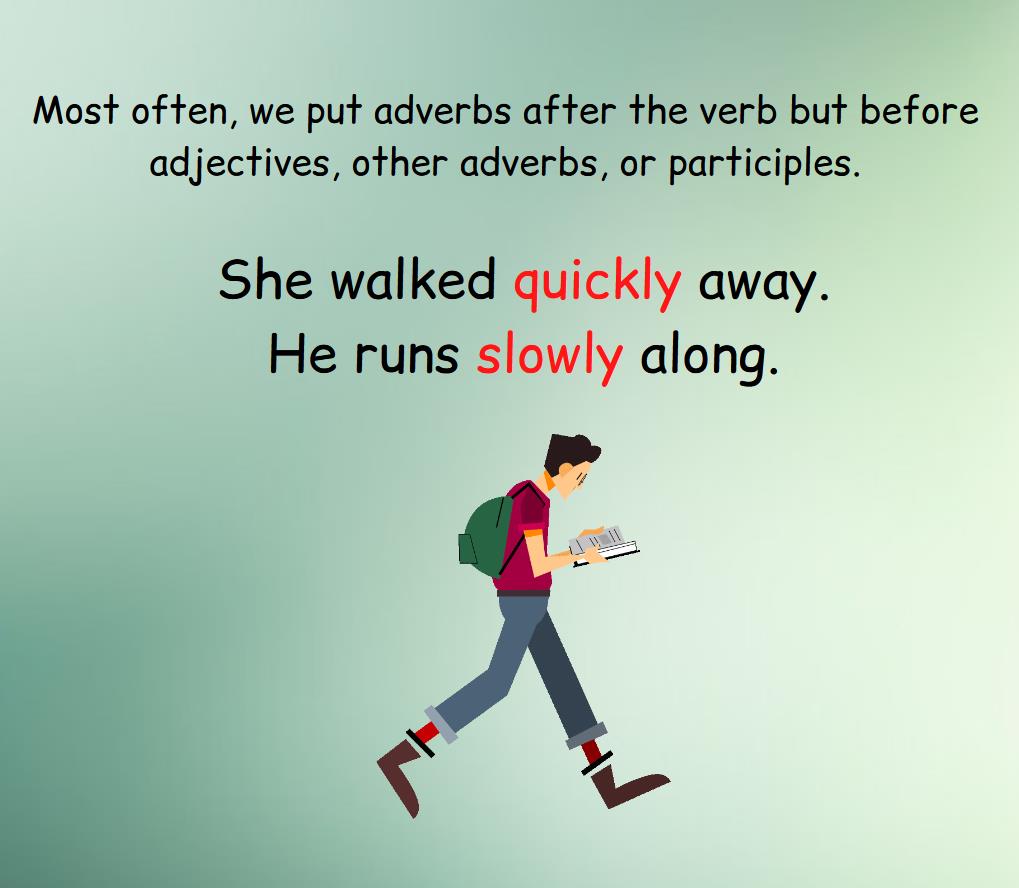

Adverbs can take different positions in a sentence. It depends on the type of sentence and on what role the adverb plays and what words the adverb defines, characterizes, describes.

Most often, we put adverbs after the verb but before adjectives, other adverbs, or participles.

She walked quickly away.

He runs slowly along.

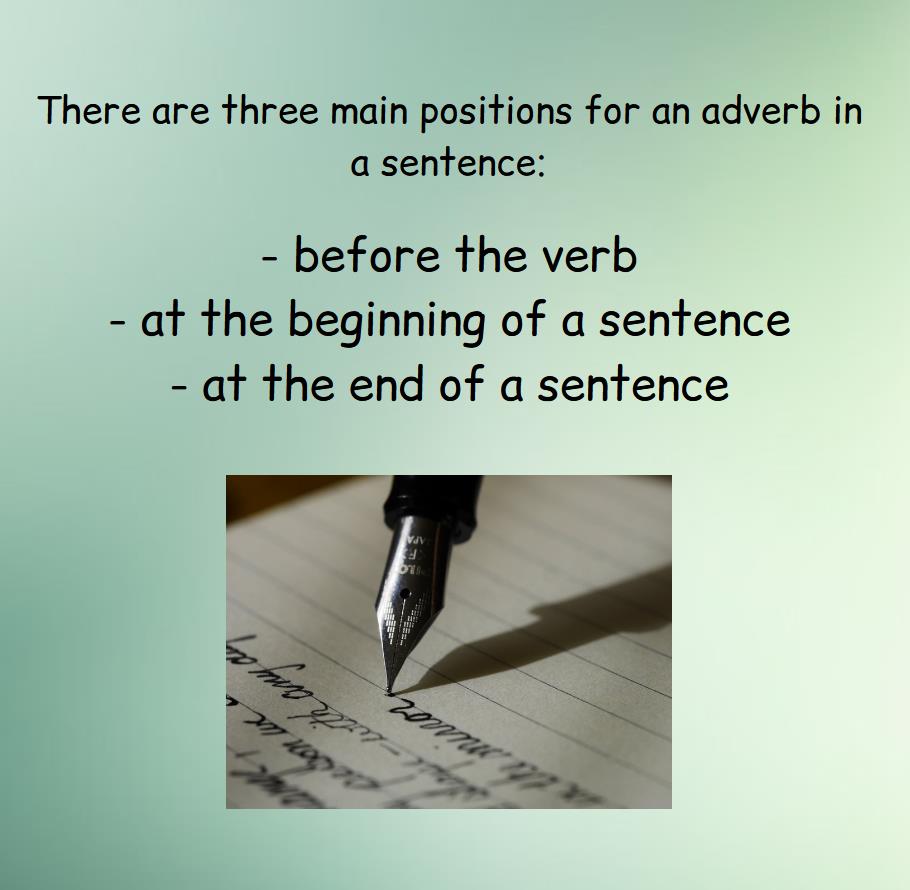

Adverb and three main positions

There are three main positions for an adverb in a sentence:

- before the verb

- at the beginning of a sentence

- at the end of a sentence

Let’s look at these positions separately.

At the end

We put an Adverb at the end of a sentence after the predicate and the object.

The water is rising fast.

At the beginning

We put an adverb at the beginning of a sentence before the subject.

Today I have a piano lesson.

In the middle

Most often, we put an adverb in the middle of a sentence. But “middle” is not an accurate concept. Where exactly this middle is located, it depends on the words next to which we use the adverb.

- In interrogative sentences, we put an adverb between the subject and the main verb.

Did he often go out like that?

- If the predicate in the sentence is only one verb, then we put the adverb before the verb.

You rarely agree with me.

- If the predicate contains more than one word, then we put the adverb after the modal verb or after the auxiliary verb (if there is a modal verb or auxiliary verb).

You must never do this again.

There are adverbs that we can put before a modal verb or an auxiliary verb.

He surely can prepare for this.

Adverb placement depending on the type of adverb

The place of an adverb depends on what type of adverbs it belongs to. Different adverbs can appear in different places.

Adverbs of manner

We usually use Adverbs of manner:

- before main verbs

- after auxiliary verbs

- at the end of the sentence

- If the verb is in the Passive Voice, then we use an adverb between the auxiliary verb and the verb in the third form.

- We usually use Adverbs of manner after the verb or after the Object.

- We can NOT use an Adverb of manner between the verb and direct object. If the sentence has a verb and a direct object, then we use an adverb of manner before the verb or after the object.

- Usually we put an adverb of manner that answers the question HOW after the verb or after the verb and the object.

She held the baby gently.

We are running slowly.

- We usually put the adverbs well, fast, quickly, immediately, slowly at the end of a sentence.

I wrote him an answer immediately.

The truck picked up speed slowly.

Adverbs of Frequency

Adverbs of frequency are adverbs that indicate how often, with what frequency an action occurs.

Adverbs of frequency answer the question “How often?“

- Most often we put Adverbs of frequency before the main verb.

- We can use normally, occasionally, sometimes, usually at the beginning of a sentence or at the end of a sentence.

- We usually put Adverbs of frequency that accurately describe the time (weekly, every day, every Saturday) at the end of a sentence.

We have another board meeting on Monday.

I wish we could have fried chicken every week.

Maybe we could do this every month.

- We put Adverbs of frequency after the verb to be if the sentence contains the verb to be in the form of Present Simple or Past Simple.

My routine is always the same.

- We often use usually, never, always, often, sometimes, ever, rarely in the middle of a sentence.

I often wish I knew more about gardening.

- We can use usually at the beginning of a sentence.

Usually, I keep it to myself.

Adverbs of degree

Adverbs of degree express the degree to which something is happening. These are such adverbs as:

- almost

- absolutely

- completely

- very

- quite

- extremely

- rather

- just

- totally

- We put Adverbs of degree in the middle of a sentence.

- We put Adverbs of degree after Auxiliary Verbs.

- We put Adverbs of degree after modal verbs.

I feel really guilty about that.

- We put Adverbs of degree before adjectives.

When guns speak it is too late to argue.

- We put Adverbs of degree before other adverbs.

He loses his temper very easily.

- Sometimes we put Adverbs of degree before modal verbs and before auxiliary verbs. Usually, we use such adverbs as:

- certainly

- definitely

- really

- surely

You definitely could have handled things better.

I think I really could have won.

- The adverb enough is an exception to this rule. We put the Adverb enough after the word it characterizes.

I have lived long enough.

Adverbs of place and time

Let’s see where we use the adverbs of place and adverbs of time.

- Most often we put the adverb of place and time at the end of the sentence.

I thought you didn’t have family nearby.

They found her place in Miami yesterday.

- We put monosyllabic adverbs of time (for example, such as now, then, soon) before main verbs but after auxiliary verbs including the verb to be.

Now imagine you see another woman.

Yes, he is now a respectable man.

- We can use adverbs of place and time at the very beginning of a sentence when we want to make the sentence more emotional.

Today, we have to correct his mistakes.

- We put the adverbs here and there at the end of the sentence.

Independent thought is not valued there.

- Most often we put adverbs of place and time after the verb or verb + object.

I can’t change what happened yesterday.

You have to attend my wedding next month.

- Most often we put such adverbs as towards, outside, backward, everywhere, nearby, downstairs, southward, at the end of the sentence or in the middle of the sentence, but immediately after the verb.

I made iced tea and left it downstairs.

With this speaker, you can hear everything outside.

I can run backward!

- We put adverbs of time that accurately define the time (for example, yesterday, now, tomorrow) at the end of the sentence.

The ship is going to be back tomorrow.

He wants it to happen now.

If we want to emphasize time, we can put an adverb that accurately specifies the time at the beginning of the sentence.

Tomorrow I’m moving to Palais Royal.

Adverbs that show the speaker’s degree of confidence.

Let’s talk about the place in the sentence occupied by Adverbs that show the speaker’s degree of confidence in what the speaker is saying.

- We can put at the beginning of the sentence such adverbs as:

- definitely

- perhaps

- probably

- certainly

- clearly

- maybe

- obviously

Certainly, you have an opinion about that.

Definitely think twice before correcting one of your mistakes again.

Maybe someone else was in her apartment that night.

We can also put adverbs like this in the middle of a sentence:

They’ll probably name a street after me.

This assumption is clearly no longer valid.

Adverbs that emphasize the meaning of the word they describe

The next group of adverbs is adverbs that emphasize the meaning of the word they describe.

- Look at the following adverbs:

- very

- really

- terribly

- extremely

- almost

- quite

- pretty

We usually put such adverbs in the middle of the sentence before the word that these adverbs characterize.

He is very tired.

She found it extremely difficult to get a job.

I’m quite happy to wait for you here.

Adverbs defining a verb

- We put an adverb after the verb to be. If the adverb defines the verb to be in one of its forms.

He was never a good man.

- If an adverb defines another adverb or adjective, then we put such an adverb most often before the word that it defines.

I can see it quite clearly.

They walked rather slowly.

Adverbs connecting sentences

Adverbs can connect sentences in a logical sequence.

Such adverbs can appear at the beginning of the sentence or in the middle of the sentence. These are such adverbs as:

- next

- anyway

- however

- besides

- next

Adverbs that explain the speaker’s point of view

Let’s take a look at Adverbs that explain the speaker’s point of view in what he says.

- fortunately

- surprisingly

- personally

We most often put them at the beginning of the sentence.

Honestly, I wish I had time to do more reading.

Often their homes are their only major material possession.

We can put some of these adverbs at the end of a sentence.

I know what you’ve done for me, honestly.

Always, Never, and Only

Now let’s talk about some adverbs separately. These are very popular adverbs that we often use in English.

- Always and never.

We usually put always and never in the middle of the sentence before the verb they define.

The bread always falls buttered side down.

Love is never paid but with true love.

- Only.

Only is an incredibly popular adverb. Most often, we put only before the word that the adverb only characterizes.

Wisdom is only found in truth.

A man can only die once.

Additional tips

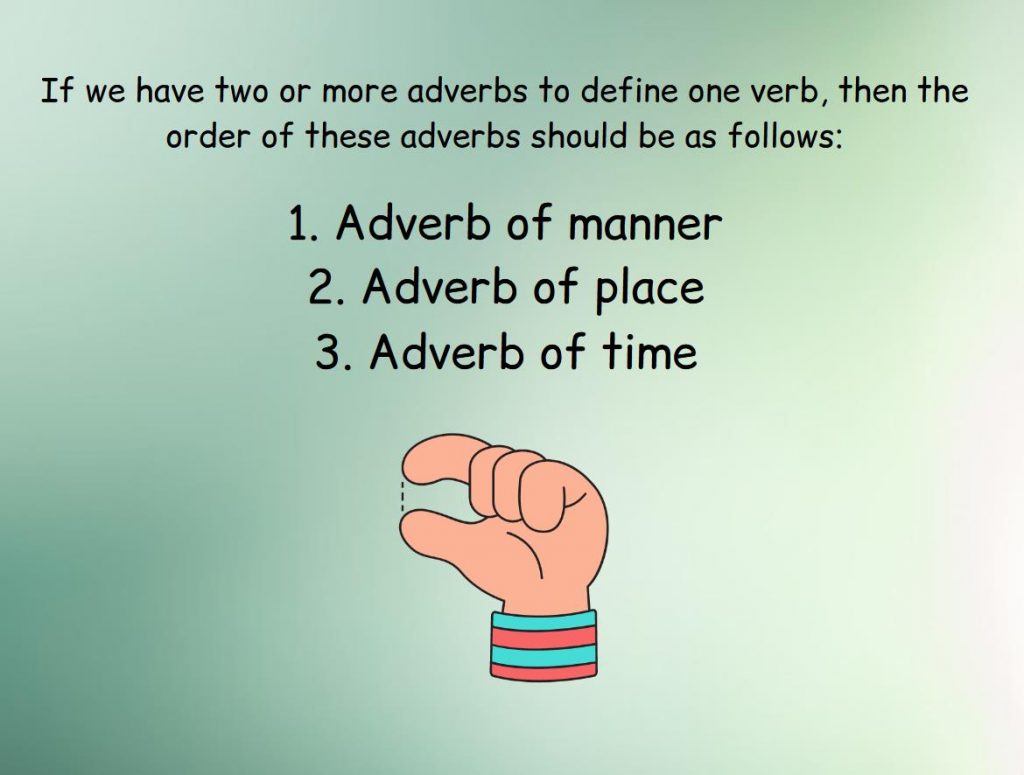

If we have two or more adverbs to define one verb, then the order of these adverbs should be as follows:

- Adverb of manner

- Adverb of place

- Adverb of time

Did I help you? Buy me a coffee 🙂

I live in Ukraine. Now, this website is the only source of money I have. If you would like to thank me for the articles I wrote, you can click Buy me a coffee. Thank you! ❤❤❤

Welcome to the ELB Guide to English Word Order and Sentence Structure. This article provides a complete introduction to sentence structure, parts of speech and different sentence types, adapted from the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences. I’ve prepared this in conjunction with a short 3-video course, currently in editing, to help share the lessons of the book to a wider audience.

You can use the headings below to quickly navigate the topics:

- Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

- Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

- Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

- Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

- Parts of Speech

- Nouns, Determiners and Adjectives

- Pronouns

- Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Adverbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Clauses, Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

There are lots of ways to break down sentences, for different purposes. This article covers the systems I’ve found help my students understand and form accurate sentences, but note these are not the only ways to explore English grammar.

I take three approaches to introducing English grammar:

- Studying overall patterns, grouping sentence components by their broad function (subject, verb, object, etc.)

- Studying different word types (the parts of speech), how their phrases are formed and their places in sentences

- Studying groupings of phrases and clauses, and how they connect in simple, compound and complex sentences

Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

English belongs to a group of just under half the world’s languages which follows a SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT order. This is the starting point for all our basic clauses (groups of words that form a complete grammatical idea). A standard declarative clause should include, in this order:

- Subject – who or what is doing the action (or has a condition demonstrated, for state verbs), e.g. a man, the church, two beagles

- Verb – what is done or what condition is discussed, e.g. to do, to talk, to be, to feel

- Additional information – everything else!

In the correct order, a subject and verb can communicate ideas with immediate sense with as little as two or three words.

- Gemma studies.

- It is hot.

Why does this order matter? We know what the grammatical units are because of their position in the sentence. We give words their position based on the function we want them to convey. If we change the order, we change the functioning of the sentence.

- Studies Gemma

- Hot is it

With the verb first, these ideas don’t make immediate sense and, depending on the verbs, may suggest to English speakers a subject is missing or a question is being formed with missing components.

- The alien studies Gemma. (uh oh!)

- Hot, is it? (a tag question)

If we don’t take those extra steps to complete the idea, though, the reversed order doesn’t work. With “studies Gemma”, we couldn’t easily say if we’re missing a subject, if studies is a verb or noun, or if it’s merely the wrong order.

The point being: using expected patterns immediately communicates what we want to say, without confusion.

Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

Understanding this basic pattern is useful for when we start breaking down more complicated sentences; you might have longer phrases in place of the subject or verb, but they should still use this order.

| Subject | Verb |

| Gemma | studies. |

| A group of happy people | have been quickly walking. |

After subjects and verbs, we can follow with different information. The other key components of sentence patterns are:

- Direct Object: directly affected by the verb (comes after verb)

- Indirect Objects: indirectly affected by the verb (typically comes between the verb and a direct object)

- Prepositional phrases: noun phrases providing extra information connected by prepositions, usually following any objects

- Time: describing when, usually coming last

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Gemma | studied | English | in the library | last week. | |

| Harold | gave | his friend | a new book | for her birthday | yesterday. |

The individual grammatical components can get more complicated, but that basic pattern stays the same.

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Our favourite student Gemma | has been studying | the structure of English | in the massive new library | for what feels like eons. | |

| Harold the butcher’s son | will have given | the daughter of the clockmaker | an expensive new book | for her coming-of-age festival | by this time next week. |

The phrases making up each grammatical unit follow their own, more specific rules for ordering words (covered below), but overall continue to fit into this same basic order of components:

Subject – Verb – Indirect Object – Direct Object – Prepositional Phrase – Time

Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

Subject-Verb-Object is a starting point that covers positive, declarative sentences. These are the most common clauses in English, used to describe factual events/conditions. The type of verb can also make a difference to these patterns, as we have action/doing verbs (for activities/events) and linking/being verbs (for conditions/states/feelings).

Here’s the basic patterns we’ve already looked at:

- Subject + Action Verb – Gemma studies.

- Subject + Action Verb + Object – Gemma studies English.

- Subject + Action Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object – Gemma gave Paul a book.

We might also complete a sentence with an adverb, instead of an object:

- Subject + Action Verb + Adverb – Gemma studies hard.

When we use linking verbs for states, senses, conditions, and other occurrences, the verb is followed by noun or adjective phrases which define the subject.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Noun Phrase – Gemma is a student.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Phrase – Gemma is very wise.

These patterns all form positive, declarative sentences. Another pattern to note is Questions, or interrogative sentences, where the first verb comes before the subject. This is done by adding an auxiliary verb (do/did) for the past simple and present simple, or moving the auxiliary verb forward if we already have one (to be for continuous tense, or to have for perfect tenses, or the modal verbs):

- Gemma studies English. –> Does Gemma study English?

- Gemma is very wise. –> Is Gemma very wise?

For more information on questions, see the section on verbs.

Finally, we can also form imperative sentences, when giving commands, which do not need a subject.

- Study English!

(Note it is also possible to form exclamatory sentences, which express heightened emotion, but these depend more on context and punctuation than grammatical components.)

Parts of Speech

General patterns offer overall structures for English sentences, while the broad grammatical units are formed of individual words and phrases. In English, we define different word types as parts of speech. Exactly how many we have depends on how people break them down. Here, we’ll look at nine, each of which is explained below. Either keep reading or click on the word types to go to the sections about their word order rules.

- Nouns – naming words that define someone or something, e.g. car, woman, cat

- Pronouns – words we use in place of nouns, e.g. he, she, it

- Verbs – doing or being words, describing an action, state or experience e.g. run, talk, be

- Adjectives – words that describe nouns or pronouns, e.g. cheerful, smelly, loud

- Adverbs – words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, sentences themselves – anything other nouns and pronouns, basically, e.g. quickly, curiously, weirdly

- Determiners – words that tell us about a noun’s quantity or if it’s specific, e.g. a, the, many

- Prepositions – words that show noun or noun phrase positions and relationships, e.g. above, behind, in, on

- Conjunctions – words that connect words, phrases or clauses e.g. and, but

- Interjections – words that express a single emotion, e.g. Hey! Ah! Oof!

For more articles and exercises on all of these, be sure to also check out ELB’s archive covering parts of speech.

Noun Phrases, Determiners and Adjectives

Subjects and objects are likely to be nouns or noun phrases, describing things. So sentences usually to start with a noun phrase followed by a verb.

- Nina ate.

However, a noun phrase may be formed of more than word.

We define nouns with determiners. These always come first in a noun phrase. They can be articles (a/an/the – telling us if the noun is specific or not), or can refer to quantities (e.g. some, much, many):

- a dog (one of many)

- the dog in the park

- many dogs

After determiners, we use adjectives to add description to the noun:

- The fluffy dog.

You can have multiple adjectives in a phrase, with orders of their own. You can check out my other article for a full analysis of adjective word order, considering type, material, size and other qualities – but a starting rule is that less definite adjectives go first – more specific qualities go last. Lead with things that are more opinion-based, finish with factual elements:

- It is a beautiful wooden chair. (opinion before fact.)

We can also form compound nouns, where more than one noun is used, e.g. “cat food”, “exam paper”. The earlier nouns describe the final noun: “cat food” is a type of food, for cats; an “exam paper” is a specific paper. With compound nouns you have a core noun (the last noun), what the thing is, and any nouns before it describe what type. So – description first, the actual thing last.

Finally, noun phrases may also include conjunctions joining lists of adjectives or nouns. These usually come between the last two items in a list, either between two nouns or noun phrases, or between the last two adjectives in a list:

- Julia and Lenny laughed all day.

- a long, quick and dangerous snake

Pronouns

We use pronouns in the place of nouns or noun phrases. For the most part, these fit into sentences the same way as nouns, in subject or object positions, but don’t form phrases, as they replace a whole noun phrase – so don’t use describing words or determiners with pronouns.

Pronouns suggest we already know what is being discussed. Their positions are the same as nouns, except with phrasal verbs, where pronouns often have fixed positions, between a verb and a particle (see below).

Verbs

Verb phrases should directly follow the subject, so in terms of parts of speech a verb should follow a noun phrase, without connecting words.

As with nouns and noun phrases, multiple words may make up the verb component. Verb phrases depend on your tenses, which follow particular forms – e.g. simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous. The specifics of verb phrases are covered elsewhere, for example the full verb forms for the tenses are available in The English Tenses Practical Grammar Guide. But in terms of structure, with standard, declarative clauses the ordering of verb phrases should not change from their typical tense forms. Other parts of speech do not interrupt verb phrases, except for adverbs.

The times that verb phrases do change their structure are for Questions and Negatives.

With Yes/No Questions, the first verb of a verb phrase comes before the subject.

- Neil is running. –> Is Neil running?

This requires an auxiliary verb – a verb that creates a grammatical function. Many tenses already have an auxiliary verb – to be in continuous tenses (“is running”), or to have in perfect tenses (have done). For these, to make a question we move that auxiliary in front of the subject. With the past and present simple tenses, for questions, we add do or did, and put that before the subject.

- Neil ran. –> Did Neil run?

We can also have questions that use question words, asking for information (who, what, when, where, why, which, how), which can include noun phrases. For these, the question word and any noun phrases it includes comes before the verb.

- Where did Neil Run?

- At what time of day did Neil Run?

To form negative statements, we add not after the first verb, if there is already an auxiliary, or if there is not auxiliary we add do not or did not first.

- Neil is running. –> Neil is not

- Neil ran. Neil did not

The not stays behind the subject with negative questions, unless we use contractions, where not is combined with the verb and shares its position.

- Is Neil not running?

- Did Neil not run?

- Didn’t Neil run?

Phrasal Verbs

Phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs, often with very specific meanings. They include at least a verb and a particle, which usually looks like a preposition but functions as part of the verb, e.g. “turn up“, “keep on“, “pass up“.

You can keep phrasal verb phrases all together, as with other verb phrases, but they are more flexible, as you can also move the particle after an object.

- Turn up the radio. / Turn the radio up.

This doesn’t affect the meaning, and there’s no real right or wrong here – except with pronouns. When using pronouns, the particle mostly comes after the object:

- Turn it up. NOT Turn up it.

For more on phrasal verbs, check out the ELB phrasal verbs master list.

Adverbs

Adverbs and adverbial phrases are really tricky in English word order because they can describe anything other than nouns. Their positions can be flexible and they appear in unexpected places. You might find them in the middle of verb phrases – or almost anywhere else in a sentence.

There are many different types of adverbs, with different purposes, which are usually broken down into degree, manner, frequency, place and time (and sometimes a few others). They may be single words or phrases. Adverbs and adverb phrases can be found either at the start of a clause, the end of a clause, or in a middle position, either directly before or after the word they modify.

- Graciously, Claire accepted the award for best student. (beginning position)

- Claire graciously accepted the award for best student. (middle position)

- Claire accepted the award for best student graciously. (end position)

Not all adverbs can go in all positions. This depends on which type they are, or specific adverb rules. One general tip, however, is that time, as with the general sentence patterns, should usually come last in a clause, or at the very front if moved for emphasis.

With verb phrases, adverbs often either follow the whole phrase or come before or after the first verb in a phrase (there are regional variations here).

For multiple adverbs, there can be a hierarchy in a similar way to adjectives, but you shouldn’t often use many adverbs together.

The largest section of the Word Order book discusses adverbs, with exercises.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, generally, demonstrate relationships between noun phrases (e.g. by, on, above). They mostly come before a noun phrase, hence the name pre-position, and tend to stick with the noun phrase they describe, so move with the phrase.

- They found him [in the cupboard].

- [In the cupboard,] they found him.

In standard sentence structure, prepositional phrases often follow verbs or other noun phrases, but they may also be used for defining information within a noun phrases itself:

- [The dog in sunglasses] is drinking water.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions connect lists in noun phrases (see nouns) or connect clauses, meaning they are found between complete clauses. They can also come at the start of a sentence that begins with a subordinate clause, when clauses are rearranged (see below), but that’s beyond the standard word order we’re discussing here. There’s more information about this in the article on different sentence types.

As conjunctions connect clauses, they come outside our sentence and word type patterns – if we have two clauses following subject-verb-object, the conjunction comes between them:

|

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

Conjunction |

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

|

He |

washed |

the car |

while |

she |

ate |

a pie. |

Interjections

These are words used to show an emotion, usually something surprising or alarming, often as an interruption – so they can come anywhere! They don’t normally connect to other words, as they are either used to get attention or to cut off another thought.

- Hey! Do you want to go swimming?

- OH NO! I forgot my homework.

Clauses and Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

While a phrase is any group of words that forms a single grammatical unit, a clause is when a group of words form a complete grammatical idea. This is possible when we follow the patterns at the start of this article, for example when we combine a subject and verb (or noun phrase and verb phrase).

A single clause can follow any of the patterns we’ve already discussed, using varieties of the word types covered; it can be as simple a two-word subject-verb combo, or it may include as many elements as you can think of:

- Eric sat.

- The boy spilt blue paint on Harriet in the classroom this morning.

As long as we have one main verb and one main subject, these are still single clauses. Complete with punctuation, such as a capital letter and full stop, and we have a complete sentence, a simple sentence. When we combine two or more clauses, we form compound or complex sentences, depending on the clauses relationships to each other. Each type is discussed below.

Simple Sentences

A sentence with one independent clause is what we call a simple sentence; it presents a single grammatically complete action, event or idea. But as we’ve seen, just because the sentence structure is called simple it does not mean the tenses, subjects or additional information are simple. It’s the presence of one main verb (or verb phrase) that keeps it simple.

Our additional information can include any number of objects, prepositional phrases and adverbials; and that subject and verb can be made up of long noun and verb phrases.

Compound Sentences

We use conjunctions to bring two or more clauses together to create a compound sentence. The clauses use the same basic order rules; just treat the conjunction as a new starting point. So after one block of subject-verb-object, we have a conjunction, then the next clause will use the same pattern, subject-verb-object.

- [Gemma worked hard] and [Paul copied her].

See conjunctions for another example.

A series of independent clauses can be put together this way, following the expected patterns, joined by conjunctions.

Compound sentences use co-ordinating conjunctions, such as and, but, for, yet, so, nor, and or, and do not connect the clauses in a dependent way. That means each clause makes sense on its own – if we removed the conjunction and created separate sentences, the overall meaning would remain the same.

With more than two clauses, you do not have to include conjunctions between each one, e.g. in a sequence of events:

- I walked into town, I visited the book shop and I bought a new textbook.

And when you have the same subject in multiple clauses, you don’t necessarily need to repeat it. This is worth noting, because you might see clauses with no immediate subject:

- [I walked into town], [visited the book shop] and [bought a new textbook].

Here, with “visited the book shop” and “bought a new textbook” we understand that the same subject applies, “I”. Similarly, when verb tenses are repeated, using the same auxiliary verb, you don’t have to repeat the auxiliary for every clause.

What about ordering the clauses? Independent clauses in compound sentences are often ordered according to time, when showing a listed sequence of actions (as in the example above), or they may be ordered to show cause and effect. When the timing is not important and we’re not showing cause and effect, the clauses of compound sentences can be moved around the conjunction flexibly. (Note: any shared elements such as the subject or auxiliary stay at the front.)

- Billy [owned a motorbike] and [liked to cook pasta].

- Billy [liked to cook pasta] and [owned a motorbike].

Complex Sentences

As well as independent clauses, we can have dependent clauses, which do not make complete sense on their own, and should be connected to an independent clause. While independent clauses can be formed of two words, the subject and verb, dependent clauses have an extra word that makes them incomplete – either a subordinating conjunction (e.g. because, when, since, if, after and although), or a relative pronoun, (e.g. that, who and which).

- Jim slept.

- While Jim slept,

Subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns create, respectively, a subordinate clause or a relative clause, and both indicate the clause is dependent on more information to form a complete grammatical idea, to be provided by an independent clause:

- While Jim slept, the clowns surrounded his house.

In terms of structure, the order of dependent clauses doesn’t change from the patterns discussed before – the word that comes at the front makes all the difference. We typically connect independent clauses and dependent clauses in a similar way to compound sentences, with one full clause following another, though we can reverse the order for emphasis, or to present a more logical order.

- Although she liked the movie, she was frustrated by the journey home.

(Note: when a dependent clause is placed at the beginning of a sentence, we use a comma, instead of another conjunction, to connect it to the next clause.)

Relative clauses, those using relative pronouns (such as who, that or which), can also come in different positions, as they often add defining information to a noun or take the place of a noun phrase itself.

- The woman who stole all the cheese was never seen again.

- Whoever stole all the cheese is going to be caught one day.

In this example, the relative clause could be treated, in terms of position, in the same way as a noun phrase, taking the place of an object or the subject:

- We will catch whoever stole the cheese.

For more information on this, check out the ELB guide to simple, compound and complex sentences.

That’s the end of my introduction to sentence structure and word order, but as noted throughout this article there are plenty more articles on this website for further information. And if you want a full discussion of these topics be sure to check out the bestselling guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook on this site and from all major retailers in paperback format.

Get the Complete Word Order Guide

This article is expanded upon in the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook and paperback.

If you found this useful, check out the complete book for more.

1. What is Word Order?

Word order is important: it’s what makes your sentences make sense! So, proper word order is an essential part of writing and speaking—when we put words in the wrong order, the result is a confusing, unclear, and an incorrect sentence.

2.Examples of Word Order

Here are some examples of words put into the correct and incorrect order:

I have 2 brothers and 2 sisters at home. CORRECT

2 brothers and 2 sisters have I at home. INCORRECT

I am in middle school. CORRECT

In middle school I am. INCORRECT

How are you today? CORRECT

You are how today? INCORRECT

As you can see, it’s usually easy to see whether or not your words are in the correct order. When words are out of order, they stand out, and usually change the meaning of a sentence or make it hard to understand.

3. Types of Word Order

In English, we follow one main pattern for normal sentences and one main pattern for sentences that ask a question.

a. Standard Word Order

A sentence’s standard word order is Subject + Verb + Object (SVO). Remember, the subject is what a sentence is about; so, it comes first. For example:

The dog (subject) + eats (verb) + popcorn (object).

The subject comes first in a sentence because it makes our meaning clear when writing and speaking. Then, the verb comes after the subject, and the object comes after the verb; and that’s the most common word order. Otherwise, a sentence doesn’t make sense, like this:

Eats popcorn the dog. (verb + object + subject)

Popcorn the dog eats. (object + subject + verb)

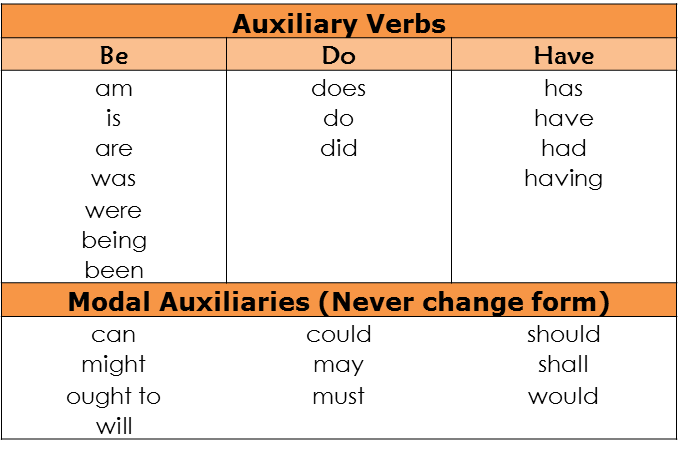

B. Questions

When asking a question, we follow the order auxiliary verb/modal auxiliary + subject + verb (ASV). Auxiliary verbs and modal auxiliaries share meaning or function, many which are forms of the verb “to be.” Auxiliary verbs can change form, but modal auxiliaries don’t. Here’s a chart to help you:

As said, questions follow the form ASV; or, if they have an object, ASVO. Here are some examples:

Can he cook? “Can” (auxiliary) “he” (subject) “cook” (verb)

Does your dog like popcorn? “Does” (A) “your dog” (S) “like” (V) “popcorn” (O)

Are you burning the popcorn? “Are” (A) “you” (S) “burning” (V) “popcorn” (O)

4. Parts of Word Order

While almost sentences need to follow the basic SVO word order, we add other words, like indirect objects and modifiers, to make them more detailed.

a. Indirect Objects

When we add an indirect object, a sentence will follow a slightly different order. Indirect objects always come between the verb and the object, following the pattern SVIO, like this:

I fed the dog some popcorn.

This sentence has “I” (subject) “fed” (verb) “dog” (indirect object) “popcorn” (direct object).

b. Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases also have special positions in sentences. When we use the prepositions like “to” or “for,” then the indirect object becomes part of a prepositional phrase, and follows the order SVOP, like this:

I fed some popcorn to the dog.

Other prepositional phrases, determining time and location, can go at either the beginning or the end of a sentence:

He ate popcorn at the fair. -Or- At the fair he ate popcorn.

In the morning I will go home. I will go home in the morning.

c. Adverbs

Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs, adding things like time, manner, degree; and often end in ly, like “slowly,” “recently,” “nearly,” and so on. As a rule, an adverb (or any modifier) should be as close as possible to the thing it is modifying. But, adverbs are special because they can usually be placed in more than one spot in the sentence and are still correct. So, there are rules about their placement, but also many exceptions.

In general, when modifying an adjective or adverb, an adverb should go before the word it modifies:

The dog was extremely hungry. CORRECT adverb modifies “hungry”

Extremely, the dog was hungry. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

The extremely dog was hungry. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

The dog was hungry extremely. INCORRECT misplaced adverb

As you can see, the word “extremely” only makes sense just before the adjective “hungry.” In this situation, the adverb can only go in one place.

When modifying a verb, an adverb should generally go right after the word it modifies, as in the first sentence below. BUT, these other uses are also correct, though they may not be the best:

The dog ran quickly to the fair. CORRECT * BEST POSITION

Quickly the dog ran to the fair. CORRECT

The dog quickly ran to the fair. CORRECT

The dog ran to the fair quickly. CORRECT

For adverbs expressing frequency (how often something happens) the adverb goes directly after the subject:

The dog always eats popcorn.

He never runs slowly.

I rarely see him.

Adverbs expressing time (when something happens) can go at either the beginning or of the end of the sentence, depending what’s important about the sentence. If the time isn’t very important, then it goes at the beginning of the sentence, but if you want to emphasize the time, then the adverb goes at the end of the sentence:

Now the dog wants popcorn. Emphasis on “the dog wants popcorn”

The dog wants popcorn now. Emphasis on “now”

5. How to Use Avoid Mistakes with Word Order

Aside from following the proper SVO pattern, it’s important to write and speak in the way that is the least confusing and the most clear. If you make mistakes with your word order, then your sentences won’t make sense. Basically, if a sentence is hard to understand, then it isn’t correct. Here are a few key things to remember:

- The subject is what a sentence is about, so it should come first.

- A modifier (like an adverb) should generally go as close as possible to the thing it is modifying.

- Indirect objects can change the word order from SVO to SVIO

- Prepositional phrases have special positions in sentences

Finally, here’s an easy tip: when writing, always reread your sentences out loud to make sure that the words are in the proper order—it is usually pretty easy to hear! If a sentence is clear, then you should only need to read it once to understand it.

GRAMMAR

Mid

position is the usual position for adverbs of indefinite frequency,

adverbs of degree, adverbs of certainty, one-word adverbs of time,

even

and only:

|

Adverbs |

Always, |

|

Adverbs |

Absolutely, |

|

Adverbs |

Certainly, |

|

One-word |

Already, |

With

a simple verb we put the adverb between the subject and the verb, but

with simple forms of be

the adverb goes after the verb:

e.g.

She always

arrives

by taxi and she is

always

on time.

If

there is a modal verb or an auxiliary verb we put the adverb after

the (first) auxiliary verb.

e.g.

You

can

just

see the coast. Sea eagles have

occasionally

been seen around Loch Lomond.

These

adverbs go after do

or not:

e.g.

They don’t

really

understand my point of view.

NB

But we put sometimes,

still, certainly, definitely

and probably

before a negative auxiliary:

e.g.

I sometimes don’t understand his arguments. He still hasn’t

convinced me.

In

spoken English, if we want to emphasise an auxiliary verb or a simple

form of be,

we can put a mid position adverb before it. The auxiliary verb

(underlined) is usually stressed. Compare:

e.g.

I