Where a prepositions placed in a sentence?

Usually, prepositions connect things to other sentence components – objects, ideas, anything typically created by a noun phrase. As such, they usually come before a noun.

- There was a spider on her back.

- It was cold at the top of the hill.

- They met in the old barn.

As a general rule, the preposition should come directly before its complement. This means the preposition is essentially part of its noun phrase, and can be moved as part of a noun phrase.

- We had coffee on the beach. OR On the beach, we had coffee.

- There was mud in my eyes. In my eyes!

- The young squirrel buried her nuts under a pile of leaves last autumn. I looked under the pile of leaves. Under the pile of leaves there were nuts.

Note that because the preposition shows a connection, if you replace the rest of a noun phrase with a pronoun you still need the preposition:

- Under the pile of leaves. becomes Under it.

Prepositions do not always move with their complement, however, and can be found at the end of a clause. This is more typical in informal language.

- This is the book I was looking for.

- Who would you like to talk to?

- I don’t know what that film was about.

There are four main situations where this happens, question words, passive structures, relative clauses, and infinitives, which are covered below.

Prepositions in Questions

Questions formed with question words, where the question word replaces the object of the preposition, often have the preposition at the end of the clause.

- Where did they go to?

- Who are you talking about?

- When are you staying until?

- How much did you buy that for?

This also happens with indirect questions.

- I don’t know where we are going to.

- It was unclear who they were talking about.

Questions can also be formed with only a question word and preposition, when the verb is understood. In this case, the preposition normally comes after the question word, but can often be reversed:

- Where to? / To where?

- What with? / With what?

- How much for? / For how much?

In formal language, prepositions are often placed further forwards in questions, coming before the question word.

- For whom was this dinner made?

- About which opera are you talking?

This is less common and can sound quite unnatural, and with some question forms (such as what…for and where…to) it is especially uncommon.

Prepositions in Passive Structures

In passive structures, the preposition stays with the verb.

- He stayed in the hotel. The hotel was stayed in.

- They fell on the mat. The mat was fallen on.

If you create a passive structure from an active structure and keep the original subject (as an object), it will follow the preposition.

- My father walked on the hill. The hill was walked on by my father.

Even in formal language, in passive structures prepositions stay with verbs.

- The lady was spoken about in hushed tones. (NOT The lady about which was spoken…)

Prepositions in Relative Clauses

Prepositions normally go at the end of a relative clause.

- That’s the girl I danced with.

- I found the book I was looking for.

This may be considered informal. In formal use, the preposition can come earlier, before a relative pronoun.

- That’s the girl with whom I danced.

- I found the book for which I was looking.

As with formal questions, this use is less common.

Prepositions in Infinitive Structures

When infinitives are used as complements, for example following stative verbs (to be), they can be followed by a preposition.

- She was not prepared to swim on.

- The king is a delightful man to talk with.

Placing the preposition before an infinitive structure is very formal.

- The king is a delightful man with whom to talk.

This guide has been taken from my grammar book, Word Order in English Sentences – if you’d like to learn more about the components of English sentences and how they fit together structurally, check out the rest of the book!

Essential grammar

in use

Word order Adverbs Prepositions of Time

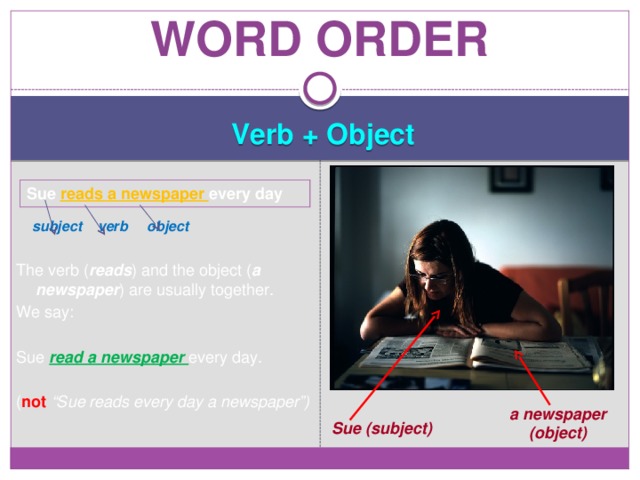

Word order

Verb + Object

subject verb object

The verb ( reads ) and the object ( a newspaper ) are usually together.

We say:

Sue read a newspaper every day.

( not “Sue reads every day a newspaper”)

Sue reads a newspaper every day

a newspaper (object)

Sue (subject)

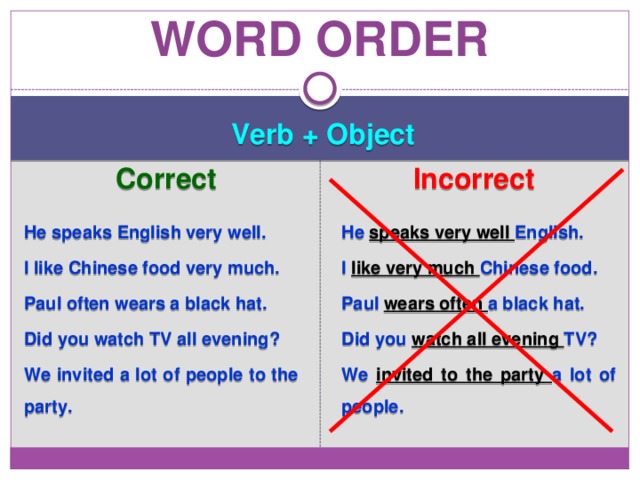

Word order

Verb + Object

Correct

Incorrect

He speaks English very well.

He speaks very well English.

I like Chinese food very much.

I like very much Chinese food.

Paul often wears a black hat.

Paul wears often a black hat.

Did you watch TV all evening?

Did you watch all evening TV?

We invited a lot of people to the party.

We invited to the party a lot of people.

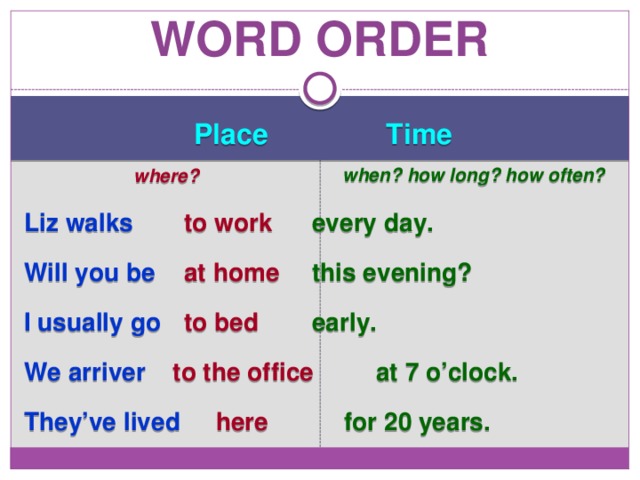

Word order

Place and Time

place time

Place ( to a party ) is usually before time ( last night ).

We say:

We went to a party last night .

( not “We went last night to a party”)

We went to a party last night .

Word order

Place Time

when? how long? how often?

where?

Liz walks to work every day.

Will you be at home this evening?

I usually go to bed early.

We arriver to the office at 7 o’clock.

They’ve lived here for 20 years.

Word order

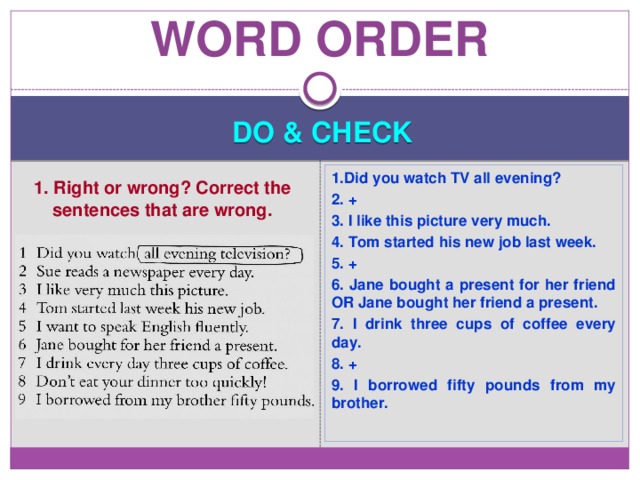

DO & CHECK

1.Did you watch TV all evening?

2. +

3. I like this picture very much.

4. Tom started his new job last week.

5. +

6. Jane bought a present for her friend OR Jane bought her friend a present.

7. I drink three cups of coffee every day.

8. +

9. I borrowed fifty pounds from my brother.

1. Right or wrong? Correct the sentences that are wrong.

Word order

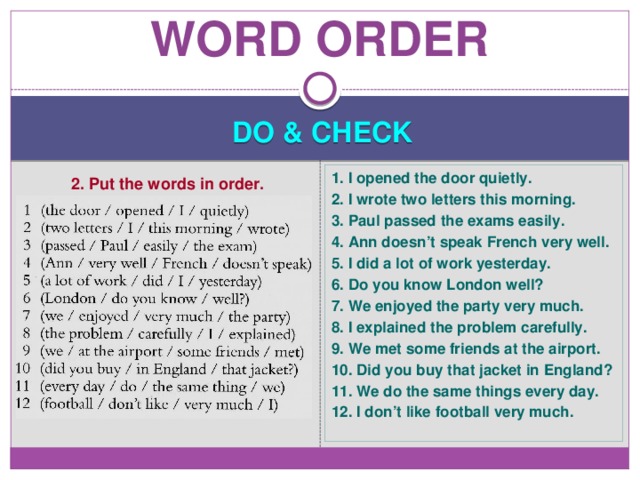

DO & CHECK

1. I opened the door quietly.

2. I wrote two letters this morning.

3. Paul passed the exams easily.

4. Ann doesn’t speak French very well.

5. I did a lot of work yesterday.

6. Do you know London well?

7. We enjoyed the party very much.

8. I explained the problem carefully.

9. We met some friends at the airport.

10. Did you buy that jacket in England?

11. We do the same things every day.

12. I don’t like football very much.

2. Put the words in order.

Word order

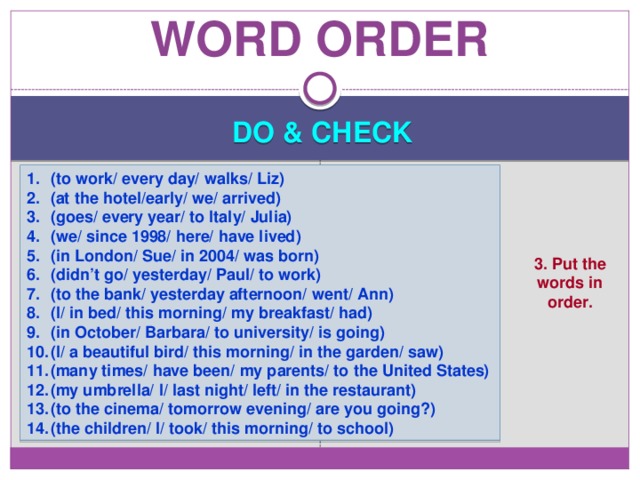

DO & CHECK

- (to work/ every day/ walks/ Liz)

- (at the hotel/early/ we/ arrived)

- (goes/ every year/ to Italy/ Julia)

- (we/ since 1998/ here/ have lived)

- (in London/ Sue/ in 2004/ was born)

- (didn’t go/ yesterday/ Paul/ to work)

- (to the bank/ yesterday afternoon/ went/ Ann)

- (I/ in bed/ this morning/ my breakfast/ had)

- (in October/ Barbara/ to university/ is going)

- (I/ a beautiful bird/ this morning/ in the garden/ saw)

- (many times/ have been/ my parents/ to the United States)

- (my umbrella/ I/ last night/ left/ in the restaurant)

- (to the cinema/ tomorrow evening/ are you going?)

- (the children/ I/ took/ this morning/ to school)

3. Put the words in order.

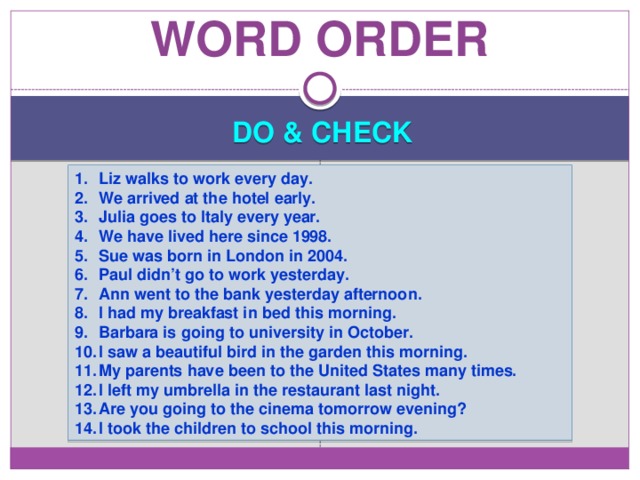

Word order

DO & CHECK

- Liz walks to work every day.

- We arrived at the hotel early.

- Julia goes to Italy every year.

- We have lived here since 1998.

- Sue was born in London in 2004.

- Paul didn’t go to work yesterday.

- Ann went to the bank yesterday afternoon.

- I had my breakfast in bed this morning.

- Barbara is going to university in October.

- I saw a beautiful bird in the garden this morning.

- My parents have been to the United States many times.

- I left my umbrella in the restaurant last night.

- Are you going to the cinema tomorrow evening?

- I took the children to school this morning.

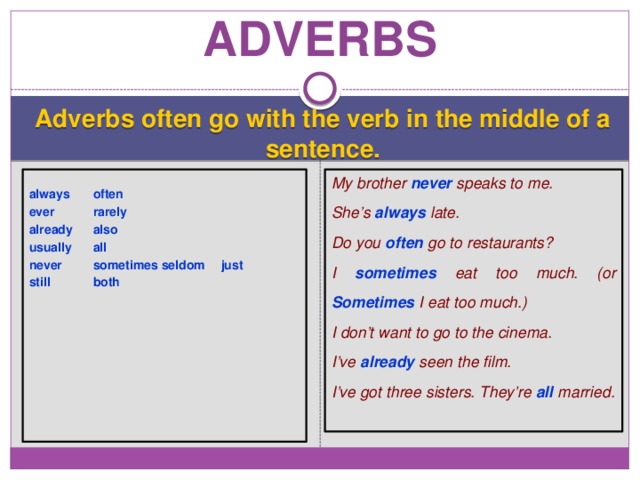

adverbs

Adverbs often go with the verb in the middle of a sentence.

My brother never speaks to me.

always often

She’s always late.

ever rarely

Do you often go to restaurants?

already also

I sometimes eat too much. (or Sometimes I eat too much.)

usually all

I don’t want to go to the cinema.

never sometimes seldom just

I’ve already seen the film.

still both

I’ve got three sisters. They’re all married.

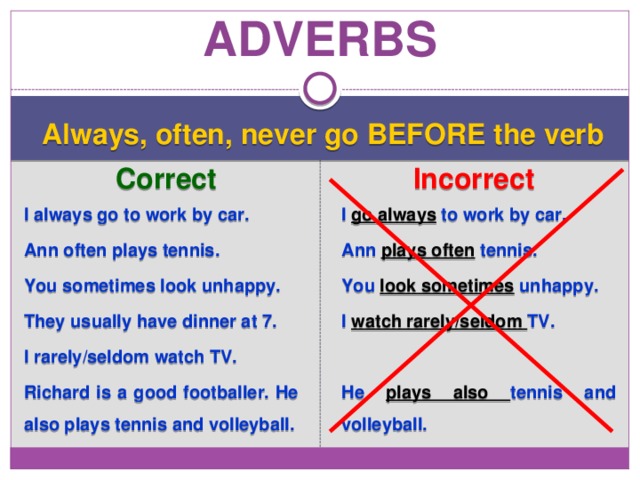

adverbs

Always, often, never go BEFORE the verb

Correct

Incorrect

I always go to work by car.

I go always to work by car.

Ann often plays tennis.

Ann plays often tennis.

You sometimes look unhappy.

You look sometimes unhappy.

They usually have dinner at 7.

I watch rarely/seldom TV.

I rarely/seldom watch TV.

He plays also tennis and volleyball.

Richard is a good footballer. He also plays tennis and volleyball.

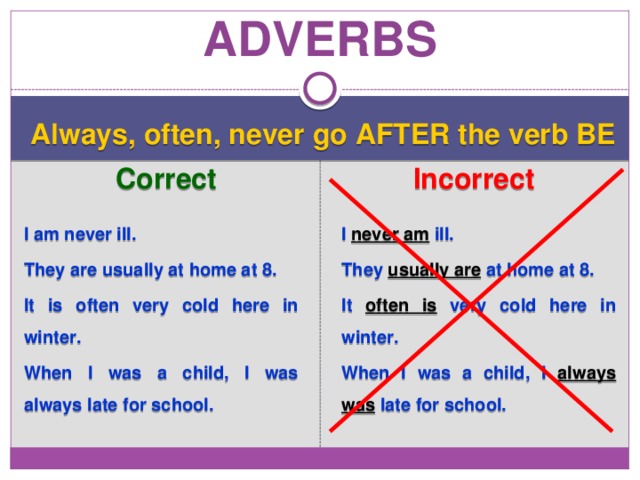

adverbs

Always, often, never go AFTER the verb BE

Correct

Incorrect

I am never ill.

I never am ill.

They are usually at home at 8.

They usually are at home at 8.

It is often very cold here in winter.

It often is very cold here in winter.

When I was a child, I was always late for school.

When I was a child, I always was late for school.

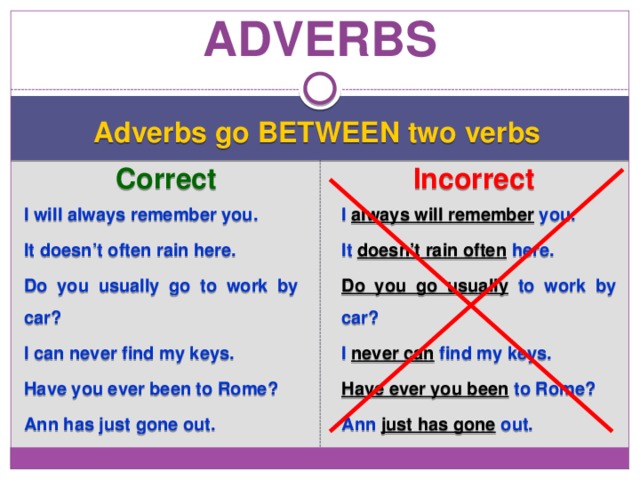

adverbs

Adverbs go BETWEEN two verbs

Correct

Incorrect

I will always remember you.

I always will remember you.

It doesn’t often rain here.

It doesn’t rain often here.

Do you usually go to work by car?

Do you go usually to work by car?

I can never find my keys.

I never can find my keys.

Have you ever been to Rome?

Have ever you been to Rome?

Ann just has gone out.

Ann has just gone out.

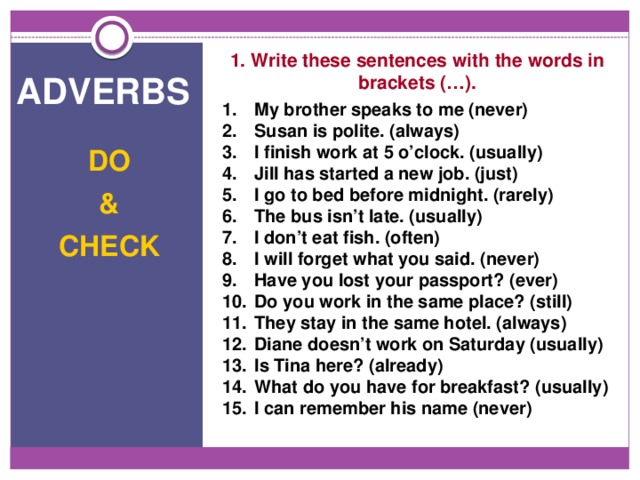

1. Write these sentences with the words in brackets (…).

adverbs

1. My brother speaks to me (never)

2. Susan is polite. (always)

3. I finish work at 5 o’clock. (usually)

4. Jill has started a new job. (just)

5. I go to bed before midnight. (rarely)

6. The bus isn’t late. (usually)

7. I don’t eat fish. (often)

8. I will forget what you said. (never)

9. Have you lost your passport? (ever)

10. Do you work in the same place? (still)

11. They stay in the same hotel. (always)

12. Diane doesn’t work on Saturday (usually)

13. Is Tina here? (already)

14. What do you have for breakfast? (usually)

15. I can remember his name (never)

DO

&

CHECK

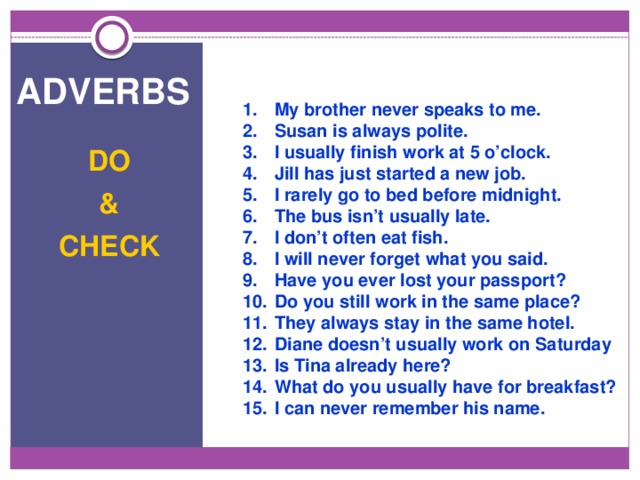

adverbs

1. My brother never speaks to me.

2. Susan is always polite.

3. I usually finish work at 5 o’clock.

4. Jill has just started a new job.

5. I rarely go to bed before midnight.

6. The bus isn’t usually late.

7. I don’t often eat fish.

8. I will never forget what you said.

9. Have you ever lost your passport?

10. Do you still work in the same place?

11. They always stay in the same hotel.

12. Diane doesn’t usually work on Saturday

13. Is Tina already here?

14. What do you usually have for breakfast?

15. I can never remember his name.

DO

&

CHECK

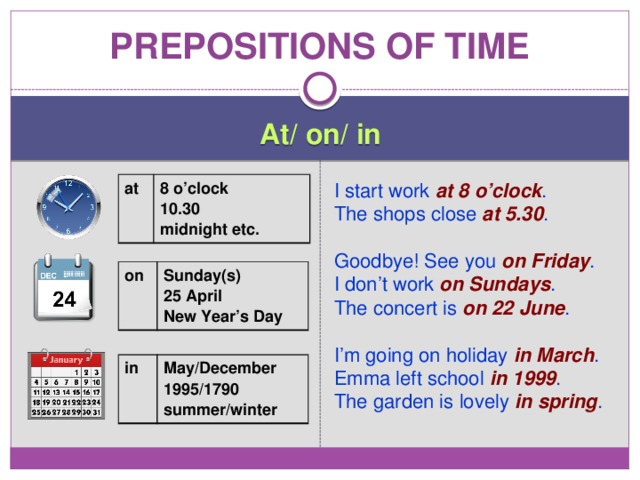

Prepositions of time

At/ on/ in

I start work at 8 o’clock .

The shops close at 5.30 .

Goodbye! See you on Friday .

I don’t work on Sundays .

The concert is on 22 June .

at

8 o’clock

I’m going on holiday in March .

10.30

Emma left school in 1999 .

midnight etc.

The garden is lovely in spring .

on

Sunday(s)

25 April

New Year’s Day

in

May/December

1995/1790

summer/winter

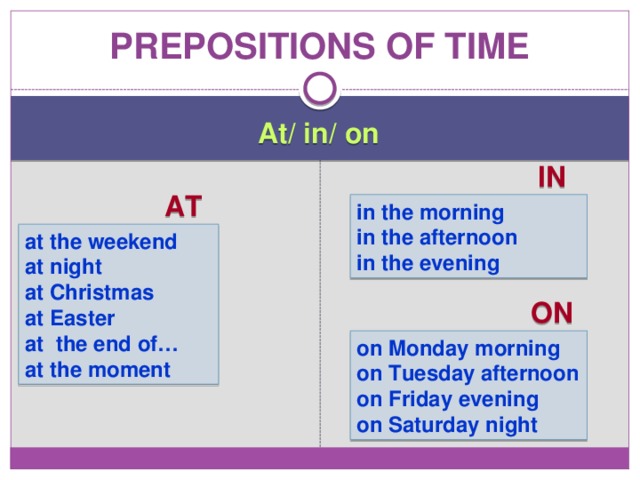

Prepositions of time

At/ in/ on

IN

AT

in the morning

in the afternoon

in the evening

at the weekend

at night

at Christmas

at Easter

at the end of…

at the moment

ON

on Monday morning

on Tuesday afternoon

on Friday evening

on Saturday night

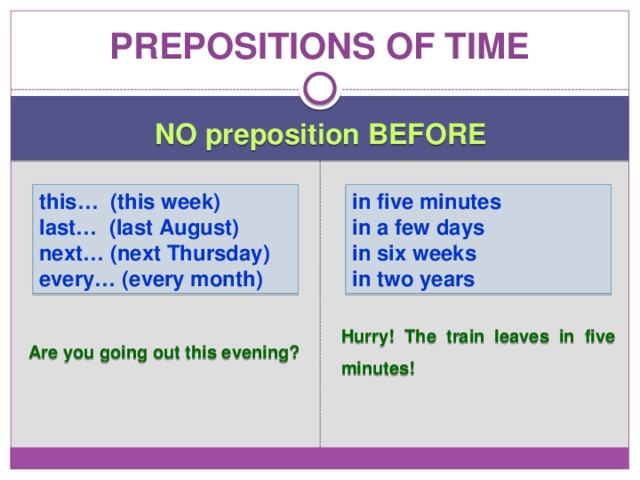

Prepositions of time

NO preposition BEFORE

this… (this week)

in five minutes

last… (last August)

in a few days

next… (next Thursday)

in six weeks

every… (every month)

in two years

Hurry! The train leaves in five minutes!

Are you going out this evening?

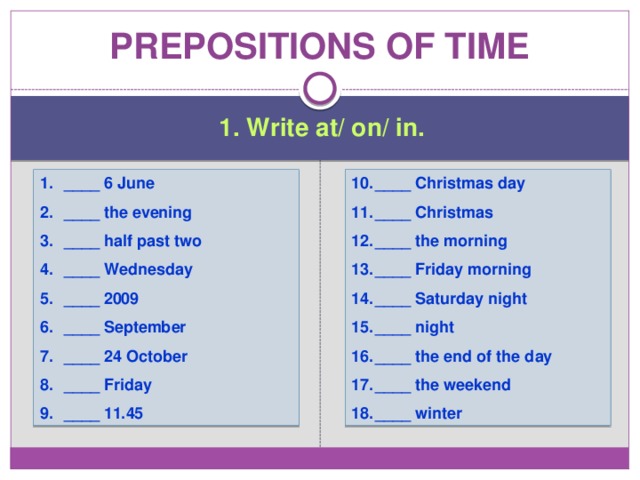

Prepositions of time

1. Write at/ on/ in.

- ____ 6 June

- ____ the evening

- ____ half past two

- ____ Wednesday

- ____ 2009

- ____ September

- ____ 24 October

- ____ Friday

- ____ 11.45

- ____ Christmas day

- ____ Christmas

- ____ the morning

- ____ Friday morning

- ____ Saturday night

- ____ night

- ____ the end of the day

- ____ the weekend

- ____ winter

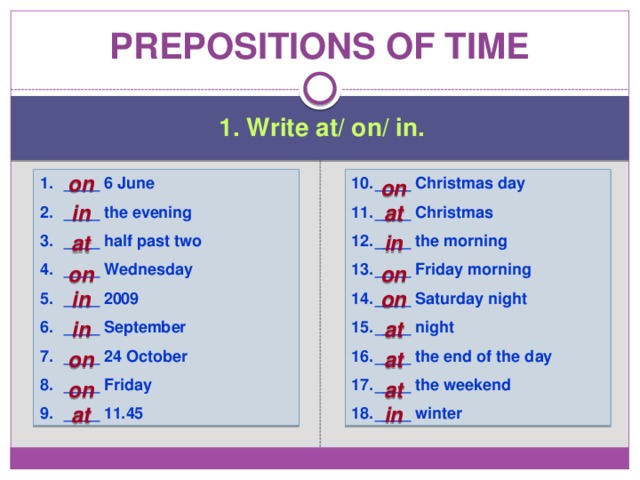

Prepositions of time

1. Write at/ on/ in.

- ____ 6 June

- ____ the evening

- ____ half past two

- ____ Wednesday

- ____ 2009

- ____ September

- ____ 24 October

- ____ Friday

- ____ 11.45

- ____ Christmas day

- ____ Christmas

- ____ the morning

- ____ Friday morning

- ____ Saturday night

- ____ night

- ____ the end of the day

- ____ the weekend

- ____ winter

on

on

at

in

at

in

on

on

in

on

at

in

on

at

on

at

at

in

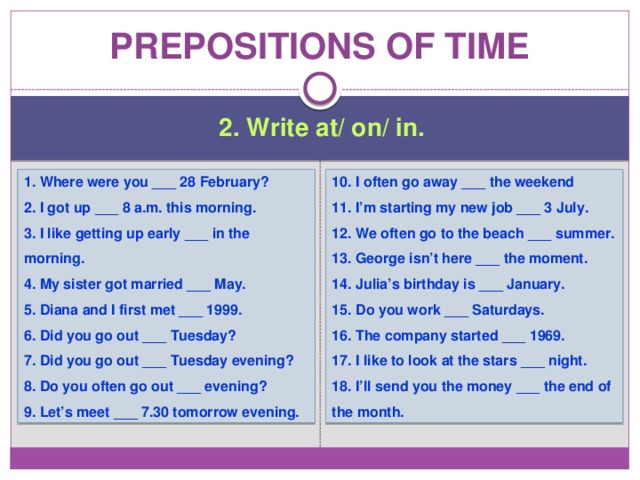

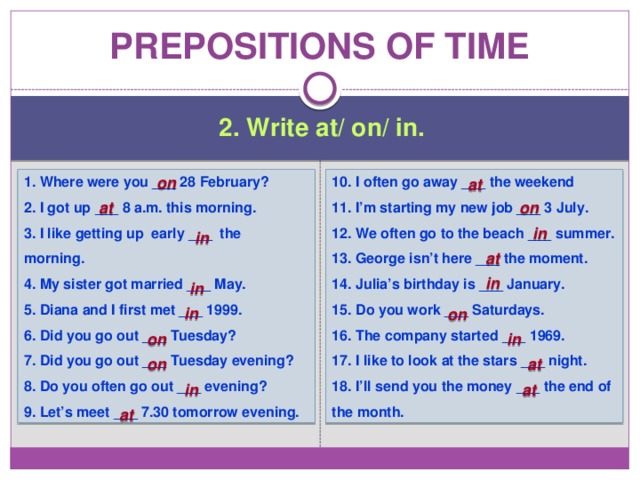

Prepositions of time

2. Write at/ on/ in.

1. Where were you ___ 28 February?

10. I often go away ___ the weekend

2. I got up ___ 8 a.m. this morning.

11. I’m starting my new job ___ 3 July.

3. I like getting up early ___ in the morning.

12. We often go to the beach ___ summer.

13. George isn’t here ___ the moment.

4. My sister got married ___ May.

5. Diana and I first met ___ 1999.

14. Julia’s birthday is ___ January.

6. Did you go out ___ Tuesday?

15. Do you work ___ Saturdays.

16. The company started ___ 1969.

7. Did you go out ___ Tuesday evening?

17. I like to look at the stars ___ night.

8. Do you often go out ___ evening?

9. Let’s meet ___ 7.30 tomorrow evening.

18. I’ll send you the money ___ the end of the month.

Prepositions of time

2. Write at/ on/ in.

1. Where were you ___ 28 February?

10. I often go away ___ the weekend

2. I got up ___ 8 a.m. this morning.

11. I’m starting my new job ___ 3 July.

on

12. We often go to the beach ___ summer.

3. I like getting up early ___ the morning.

4. My sister got married ___ May.

13. George isn’t here ___ the moment.

5. Diana and I first met ___ 1999.

14. Julia’s birthday is ___ January.

15. Do you work ___ Saturdays.

6. Did you go out ___ Tuesday?

16. The company started ___ 1969.

7. Did you go out ___ Tuesday evening?

8. Do you often go out ___ evening?

17. I like to look at the stars ___ night.

18. I’ll send you the money ___ the end of the month.

9. Let’s meet ___ 7.30 tomorrow evening.

at

at

on

in

in

at

in

in

in

on

on

in

on

at

at

in

at

Prepositions of time

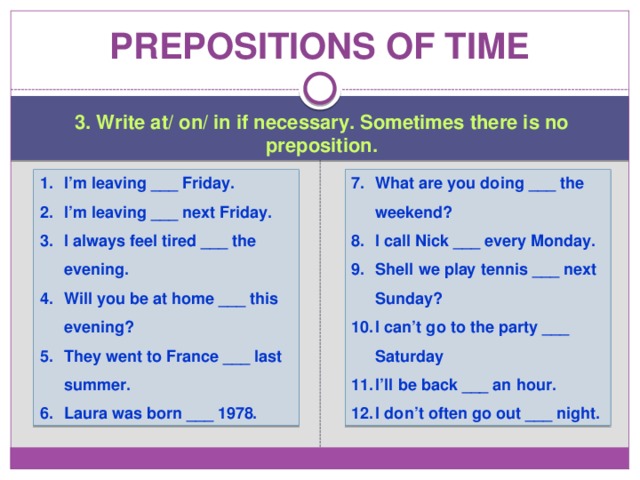

3. Write at/ on/ in if necessary. Sometimes there is no preposition.

- I’m leaving ___ Friday.

- I’m leaving ___ next Friday.

- I always feel tired ___ the evening.

- Will you be at home ___ this evening?

- They went to France ___ last summer.

- Laura was born ___ 1978.

- What are you doing ___ the weekend?

- I call Nick ___ every Monday.

- Shell we play tennis ___ next Sunday?

- I can’t go to the party ___ Saturday

- I’ll be back ___ an hour.

- I don’t often go out ___ night.

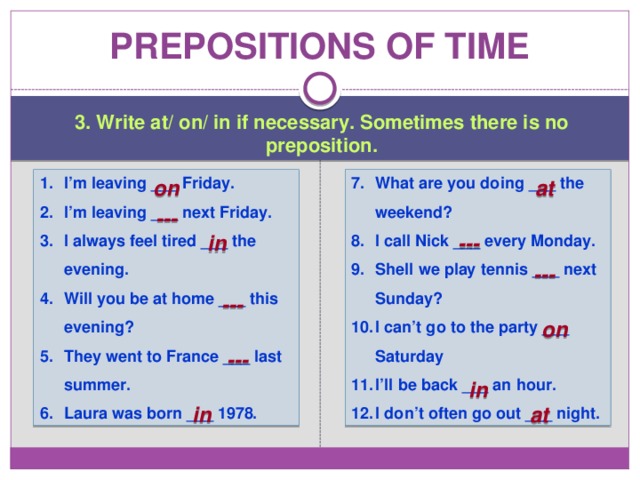

Prepositions of time

3. Write at/ on/ in if necessary. Sometimes there is no preposition.

- I’m leaving ___ Friday.

- I’m leaving ___ next Friday.

- I always feel tired ___ the evening.

- Will you be at home ___ this evening?

- They went to France ___ last summer.

- Laura was born ___ 1978.

- What are you doing ___ the weekend?

- I call Nick ___ every Monday.

- Shell we play tennis ___ next Sunday?

- I can’t go to the party ___ Saturday

- I’ll be back ___ an hour.

- I don’t often go out ___ night.

on

at

—

in

—

—

—

on

—

in

in

at

Авторская страничка

За основу использовано учебное пособие

- Murphy Raymond, Essential Grammar In Use, Cambridge University Press, 2000

Изображения:

- http://cdn1.iconfinder.com/data/icons/general12/png/256/calendar.png

- http://contently.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/calendar_icon3.png

- http://clipartist.net/RSS/openclipart.org/Unity/clock_wall_paper_art-555px.png

Составила:

Левенцева Т.А.,

учитель английского языка

МОУ «Гимназия №3» г.Воркуты

2013г.

Теория

| 1. | General information about prepositions | |

| 2. | Structure types of prepositions | |

| 3. | Prepositions of place | |

| 4. | Prepositions of place | |

| 5. | Prepositions of place: in | |

| 6. | Prepositions of place: on | |

| 7. | Prepositions of place: at | |

| 8. | Prepositions of movement and direction | |

| 9. | Prepositions of time | |

| 10. | Prepositions of time: in | |

| 11. | Prepositions of time: on | |

| 12. | Prepositions of time: at | |

| 13. | Prepositions of agent and instrument | |

| 14. | Prepositions ‘for’ and ‘since’ | |

| 15. | Prepositions ‘between’, ‘among’ | |

| 16. | Prepositions ‘in’, ‘on’, ‘at’ with the verb ‘arrive’ | |

| 17. | Expressions ‘in time’, ‘on time’ | |

| 18. | Expressions ‘at / in the beginning’, ‘at / in the end’ | |

| 19. | Verb + preposition |

Задания

| 1. |

Grammar. Prepositions. Structural types of prepositions

Сложность: |

1 |

| 2. |

Grammar. Prepositions. Types of prepositions according to their meaning

Сложность: |

1,5 |

| 3. |

Grammar. Prepositions. Word order

Сложность: |

1,5 |

| 4. |

Grammar. Prepositions of time

Сложность: |

2 |

| 5. |

Grammar. Prepositions of time — 2

Сложность: |

2 |

| 6. |

Grammar. Prepositions of place

Сложность: |

2 |

| 7. |

Grammar. Prepositions. Verb + preposition

Сложность: |

4 |

| 8. |

Grammar. Prepositions ‘in’, ‘on’, ‘at’ with the verb ‘arrive’

Сложность: |

3,5 |

| 9. |

Grammar. Prepositions. All rules

Сложность: |

4 |

Тесты

| 1. |

Training test. Types of prepositions, word order

Сложность: лёгкое |

4 |

| 2. |

Training test. Prepositions of time and place

Сложность: среднее |

4 |

Материалы для учителей

| 1. | Методическое описание |

Frequently asked questions about prepositions

FAQ’s

A preposition is used to link noun, pronouns and phrases to other words in a sentence. The word or phrase that the preposition introduces is called the object of the preposition. A preposition is used to indicate the temporal, spatial or logical relationship of its object to the rest of the sentence. Here are some examples:

The pencil is on the desk.

The pencil is beneath the desk.

The pencil is leaning against the desk.

The pencil is on the floor beside the desk.

He held the pencil over the desk.

He wrote with the pencil during class.

You may have noticed that in each of the preceding sentences, the preposition located the noun «pencil» in space or in time.

Here are some general rules regarding prepositions:

• It is permissible to end a sentence with a preposition.

• A preposition is followed by a noun.

• A preposition is never followed by a verb.

• It is permissible to begin a sentence with a preposition, or a prepositional phrase, but be very careful when you do so.*

• A prepositional phrase always begins with a preposition and ends with a noun or pronoun called the OBJECT of the preposition.

• The subject of the sentence can never be part of a prepositional phrase.

• A verb can never be a part of a prepositional phrase.

There is a so-called “rule” about never ending a sentence with a preposition and it comes from Latin grammar. In Latin grammar, the word order of a sentence didn’t matter; subjects and verbs and direct objects could appear in any sequence. However, the placement of prepositions was very important. A Latin sentence would quickly become confusing if the preposition did not appear immediately before the object of the preposition, so it became a stylistic rule for Latin writers to have objects always and immediately following prepositions. This Latin grammar «rule» meant that a sentence would never end with a preposition.

When English grammarians in the 1500s and 1600s starting writing grammar books, they tended to apply Latin rules to English, even though those rules had never been applicable before. I believe that they wanted to make English a more scholarly language, like Latin.

Here is a list of some prepositions:

| aboard | about | above | absent | according to |

| across | after | against | ahead of | all over |

| along | along side | amid/amidst | among | around |

| as | as of | as to | aside | astride |

| at | away from | except | bar | barring |

| because of | before | behind | below | beneath |

| beside(s) | between | beyond | but | by |

| by the time of | circa | close by | close to | concerning |

| considering | despite | down | due to | during |

| except for | excepting | excluding | failing | for |

| from | in | in between | in front of | in spite of |

| in view of | including | inside | instead of | into |

| less | like | minus | near | near to |

| next to | notwithstanding | of | off | on |

| on top of | onto | opposite | out | out of |

| outside | over | past | pending | per |

| plus | regarding | respecting | round | save |

| saving | similar to | since | than | through |

| throughout | till | to | toward(s) | under |

| underneath | unlike | until | unto | up |

| upon | versus | via | wanting | while |

| with | within | without |

* This is a “rule” that been questioned for many years. Many writers actually do start sentences with prepositions and many college professors have no problems with it. The reason for the “rule” was that a preposition usually indicates the temporal, spatial or logical relationship of its object to the rest of the sentence. Therefore if you start a sentence with a preposition it can appear that you are in the middle of a sentence or thought. If you are careful however, you can start a sentence with a prepostion. The problem is that most people are not careful. Here is an example of a sentence that starts with a prepostition that works: Before going to the store, I always check my list. Many people use prepositions incorrectly at the beginning of a sentence, therefore, the “rule” came to be. You can think of it as more of a “suggestion” than a rule. When you are writing a paper for a school project, it is safer to use the rule.

There is a right way and a wrong way to start a sentence with a preposition. Many authors and writers start some of their sentences with prepositions and it works very well for them. You simply have to be careful when starting a sentence with a prepostion, that the sentence does not become fragmented as a reuslt.

Here is an example with the preposition up.

Correct usage: We ran up the hill.

Incorrect: Up the hill we ran.

Here is an example with the preposition over.

Correct: The rabbit jumped over the log.

incorrect: Over the log the rabbit jumped.

Here is an example with the preposition aboard.

Correct: We got aboard the train to ride down to San Diego.

Incorrect: Aboard the train we got to ride down to San Diego.

Examples of prepositions at the beginning of a sentence:

Despite the rain, we still went jogging.

Barring any setbacks, the quarterback will play in the next game.

In spite of all the harm it causes, people still smoke cigarettes.

Remember that prepositions are connecting words and are generally used to connect a noun or pronoun to another word in a sentence.

Beware of the phrase “in terms of” and do not use it. This phrase is a sloppy use of prepositions that should be avoided. Strunk & White, in their book The Elements of Style recommend that this phrase should not be used. They give this example: The job was unattractive in terms of salary. Instead use: The salary made the job unattractive.

Frequently asked questions about prepositions

FAQ’s

Have a question or comment about “prepositions?”

Touch the button below to send Steven P. Wickstrom an e-mail:

1. Defining the values

This map shows the order of adposition and noun phrase. The two primary types of adpositions are prepositions and postpositions: prepositions precede the noun phrase they occur with, as in English and in the Boumaa Fijian (Austronesian) example in (1a), while postpositions follow the noun phrase they occur with, as in the Lezgian (Nakh-Daghestanian; Russia) example in (1b).

(1)

a.

Boumaa Fijian (Dixon 1988: 216)

au

na

talai

Elia

i

’Orovou

1sg

fut

send

Elia

to

’Orovou

Prep

NP

‘I’ll send Elia to ’Orovou.’

b.

Lezgian (Haspelmath 1993: 218)

duxtur-r-in

patariw

fe-na

doctor-pl-gen

to

go-aor

NP

Postp

‘She went to doctors.’

A word is treated here as an adposition (preposition or postposition) if it combines with a noun phrase and indicates the grammatical or semantic relationship of that noun phrase to the verb in the clause. Some languages also employ adpositions to indicate a relationship of a noun phrase to a noun (especially in a genitive/possessive relationship); however, if the only candidates in a language for adpositions are in the genitive construction, they are not treated as adpositions here.

In some languages, some or all of the functions of adpositions are carried by case affixes on nouns, as in the example in (2) from Ngalakan (Gunwinyguan; Northern Territory, Australia).

(2) Ngalakan (Merlan 1983: 46)

ŋañjuḷa-ŋini-ʔwala

ŋu-yerk-gaŋiñ

eye-1sg.poss—from

1sg.3sg-come.out-caus.pst.punct

‘I removed it from my eye.’

Case affixes and adpositions can be referred to together as case markers. While some linguists occasionally apply the terms preposition or postposition to case affixes with meanings corresponding to prepositions in European languages, case affixes are not treated as adpositions on this map (see Map 51A on case affixes). On the other hand, many languages have case markers which are not separate words phonologically but whose position is still determined syntactically. The most common instances of this are case markers that are clitics which attach phonologically to the first or last word in the noun phrase, as illustrated by the postpositional clitic in (3) from Kunuz Nubian (Nilo-Saharan; Egypt).

(3) Kunuz Nubian (Abdel-Hafiz 1988: 283)

[esey

kursel]=lo

uski-takki-s-i

[village

old]=loc

born-pass-pst-1sg

‘I was born in an old village.’

Such clitic case markers, which attach to modifiers of the noun if they are at the beginning or end of the noun phrase, are treated here as instances of adpositions since they combine syntactically with noun phrases, even though they are not separate phonological words. A number of languages in which modifiers always precede the noun, and in which the case marker always occurs at the end of the noun phrase (and hence on the noun), are in principle ambiguous as to whether the case marker should be treated as a case suffix or a postpositional clitic; for the purposes of this map, I treat such case markers as case suffixes and not as postpositional clitics.

The map also shows a rare third type of adposition, what I will call inpositions, adpositions which occur or can occur inside the noun phrase they accompany. In Anindilyakwa (isolate; Northern Territory, Australia) the inpositions are second-position clitics within the noun phrase, attaching phonologically to the end of the first word in the noun phrase, as in (4), in which the inposition attaches to the word for ‘small’ in the noun phrase meaning ‘small stick’.

(4) Anindilyakwa (Groote Eylandt Linguistics-langwa 1993: 202)

…narri-ng-akbilyang-uma

[eyukwujiya=manja

eka]

…nc₁.pl-nc₂-stick.to.end-ta

[small=loc

stick]

‘… they stuck them (the feathers) to a little stick.’

In Tümpisa Shoshone (Uto-Aztecan; California), the inpositions appear immediately after the noun and before any postnominal modifiers (if there are any), as in (5).

(5) Tümpisa Shoshone (Dayley 1989b: 257)

[ohipim

ma

natii’iwantü-nna]

tiyaitaiha

satü

[cold.obj

from

mean-obj]

died

that

‘He died from a mean cold.’

In (5), the inposition ma ‘from’ appears between the head noun ohipim ‘cold’ and its postnominal modifier natti’iwantünna ‘mean’. Note that the inpositions in Tümpisa Shoshone govern the objective case on pronouns, nouns and their modifiers (though the case is often null, as in the noun ohipim ‘cold’), as shown on the postnominal modifier in (5). This shows that despite appearing inside the noun phrase, the inposition still determines the case inflection of words in that noun phrase. Only eight languages are shown on the map as having inpositions as the dominant adposition type, seven of them in Australia.

Some languages have both prepositions and postpositions. While there are some languages in which specific adpositions can be used either as prepositions or as postpositions, in most languages of mixed adposition type, some of the adpositions are always prepositions while others are always postpositions. In some languages with both prepositions and postpositions, one type is considered dominant if there are considerably more adpositions of one type than the other or if there is reason to believe that one type is considerably more common in usage (see “Determining Dominant Word Order”). In Koyra Chiini (Songhay; Mali), for example, there are more than twice as many postpositions as prepositions and the prepositions have more specialized meanings (like ‘without’), while some of the postpositions have fairly basic meanings, suggesting that postpositions are probably much more common in usage (Heath 1999b: 103, 108). If neither type can be considered dominant, then the language is shown on the map as more than one adposition type with none dominant, though this also includes rare instances of languages with both postpositions and inpositions, such as Hanis Coos (Oregon Coast family; Frachtenberg 1922b). For example, Koromfe (Gur, Niger-Congo; Burkina Faso and Mali) has only two prepositions and an unclear number of postpositions (but greater than two); however, one of the prepositions has very broad meaning and appears to occur with high frequency, so Koromfe is treated as a language lacking a dominant adposition type (Rennison 1997: 73, 77, 294).

The final type consists of languages which do not have adpositions, or at least appear not to. Some such languages only employ case affixes as case markers, as in Yidiny (Pama-Nyungan; Queensland, Australia; Dixon 1977a); others lack case markers altogether, as in Kutenai (isolate; western North America). This type is underrepresented on the map because grammars do not generally say if a language lacks adpositions and one can only infer the absence of adpositions from a thorough grammar. Some languages only have one minor adposition. For example, Wardaman (Yangmanic; Northern Territory, Australia) has only one postposition, meaning ‘like’, as in (6).

(6) Wardaman (Merlan 1994: 99)

mernden

marrajbi

ya-wurr-yanggan

white.abs

like

3.subj-3nsg.obj-go.potential

‘They have to be like white people.’

The words analysed here as prepositions or postpositions are often referred to by authors of grammars by some other label. For example, what are treated here as clitic postpositions are often referred to as case suffixes in descriptions of languages, and many grammars do not mention that the so-called case suffixes attach to modifiers of the noun rather than to the noun if the modifier is the last element in the noun phrase. Even among adpositions which are not clitics, the words that count here as adpositions are often referred to by some other term. In some grammars, for example, they are called relators (e.g. Derbyshire 1985 in reference to postpositions in Hixkaryana). In many languages, the words treated here as adpositions share grammatical properties with nouns or verbs and are often for that reason referred to in grammars as nouns or verbs. These shared properties generally reflect the fact that it is common for nouns and verbs to grammaticalize as adpositions, while often still retaining grammatical properties reflecting their grammaticalization source. For example, in Jakaltek (Mayan; Guatemala), prepositions inflect for their object with the same set of pronominal prefixes that indicate possessors on nouns, and the structure of prepositional phrases is the same as that of noun phrases with possessors. Thus the construction in (7a) mirrors that in (7b).

(7) Jakaltek (Craig 1977: 110, 106)

a.

y-ul

te’

n̈ah

3-in

the.clf

house

‘in the house’

b.

y-ixal

naj

pel

3-wife

clf

Peter

‘Peter’s wife’

Such situations can either be described by saying that prepositions share certain properties with nouns or by saying that prepositions are a subclass of nouns. It is assumed here that the difference between these two ways of describing the situation is terminological. In fact, while Craig (1977) refers to words like ul ‘in’ in (7a) as prepositions, Day (1973: 82), in a different description of the same language, characterizes them as nouns. Thus, the fact that a set of words with adpositional meaning arguably constitute a subclass of some other class, such as nouns or verbs, is not considered here as a reason not to treat them as adpositions.

On the other hand, the fact that certain nouns (or verbs) in a language sometimes translate into prepositions in English is not sufficient for them to be treated here as adpositions. There must be some reason to believe that they have grammaticalized to some extent, that they are to some extent grammatically distinct from other nouns (or verbs). For example, in languages with serial verb constructions, the equivalent of an instrumental adposition is often expressed by a verb meaning ‘use’, as in the example in (8) from Mandarin.

(8) Mandarin (Li and Thompson 1981: 597)

tāmen

yòng

shǒu

chī-fan

3pl

use

hand

eat-food

‘They eat with their hands.’

But in the absence of evidence of grammaticalization, an example like that in (8) is not sufficient to conclude that the word yòng ‘use’ functions as anything but a normal verb. Conversely, in Maybrat (West Papuan; Papua, Indonesia), there is a word ae ‘at’ which is morphologically and syntactically a verb. The example in (9a) illustrates it functioning as a main verb, while the example in (9b) illustrates it functioning prepositionally.

(9) Maybrat (Dol 1999: 87, 88)

a.

y-ae

Sorong

3sg.m-at

Sorong

‘He is in Sorong.’

b.

ait

y-amo

m-ae

amah

3sg.m

3sg.m-go

3sg.f-at

house

‘He goes home.’

However, when ae is used prepositionally, as in (9b), it always occurs with a third person singular feminine subject prefix regardless of the person, number, and gender of the subject, indicating that it is grammatically distinct from normal verbs. It thus counts as a preposition for the purposes of this map.

2. Geographical distribution

Because adposition type correlates strongly with the order of object and verb (see Chapter 95), the distribution of prepositions and postpositions on this map resembles the distribution of object and verb on Map 83A. Prepositions predominate in the following areas: (i) Europe, North Africa and the Middle East; (ii) central and southern Africa; (iii) a large area extending from Southeast Asia, through Indonesia, the Philippines and the Pacific; (iv) the Pacific Northwest in Canada and the United States; and (v) Mesoamerica. Postpositions predominate (i) in most of Asia, except in Southeast Asia; (ii) in New Guinea, except in the northwest; (iii) in North America, except in the two areas noted above; and (iv) in most of South America. Postpositions are more common than prepositions in much of Australia, especially among Pama-Nyungan languages, but in the northern part of Northern Territory, both types occur with comparable frequency. In fact, for many Australian languages, especially Pama-Nyungan, there is no evidence of adpositions of any sort. While prepositions predominate in Africa as a whole, there are still many languages with postpositions, including an area in West Africa and one to the northeast. There is one area in Africa stretching from Sudan and Ethiopia southwest into the northeastern corner of the Democratic Republic of the Congo where the map is quite complex. Languages with no adpositions are most common in Australia and North America.