Word Order in Complex Sentences

There are five parts of a sentence: the subject, the predicate, the attribute, the object, and the adverbial modifier. Accordingly, there are five types of subordinate clauses: the subject clause, the predicative clause, the attributive clause, the object clause, and several types of adverbial clauses.

Subordinate clauses are also called dependent clauses because they can’t be used without the main clause. Word order in subordinate clauses is first the subject, then the verb. Compare these pairs of simple and complex sentences:

I bought a book on history.

I bought the book that you asked for.

I know the way to his house.

I know where he lives.

He went home after work.

He went home after he had finished work.

The subject clause

The subject clause functions as the subject of the sentence. Subject clauses are introduced by the words «who, what, how, when, where, that, whether».

Who brought the roses is a secret.

What you told me was interesting.

How it happened is not clear.

The subject clause is often placed after the predicate, and the formal subject «It» is used in such sentences.

It is not known who brought the roses.

It is not clear how it happened.

It is doubtful that he will come back today.

The predicative clause

The predicative clause functions as part of the predicate and usually stands after the linking verb BE.

The problem is that he is rude.

The question is where I can find enough money for my project.

This is what he said to her.

This is how it happened.

The attributive clause

The attributive clause performs the function of an attribute and stands after the noun that it modifies. Attributive clauses are introduced by the words «who, whom, whose, which, that, when, where, why».

The man who helped her was Dr. Lee.

The bag that he bought cost forty dollars.

Here’s the book that I am talking about.

The place where she lives is not far from here.

The time when they were friends is gone.

The object clause

Object clauses function as objects. (Object clauses are described more fully in Sequence of Tenses in the section Grammar.)

He told us that he had already bought a car.

I know where we can find him.

I asked how I could help him.

Types of adverbial clauses

Adverbial clauses function as adverbial modifiers. Adverbial clauses include several types of clauses that indicate time, place, purpose, cause, result, condition, concession, manner, comparison.

The adverbial clause of place

He went where I told him to go.

This cat sleeps wherever it wants.

Go down this street and stop where the road turns right.

The adverbial clause of time

When she arrived, they went home.

She left while he was sleeping.

He hasn’t called me since he arrived.

He left before I returned.

Call me as soon as you receive the report.

No future tense is used in subordinate clauses of time referring to the future (after the conjunctions «when, till, until, after, before, as soon as, as long as, by the time», and some others). The present tense, usually the Simple Present, is used instead of the future in clauses of time.

He will call you when he returns.

I’ll help you after I have dinner.

I will wait until he finishes his work.

I said that I would wait until he finished his work.

The adverbial clause of condition

We will go to the lake on Saturday if the weather is good.

If the plane left on time, they should be in New York now.

If he has already seen the report, he knows about our plans.

No future tense is used in subordinate clauses of condition referring to the future (after the conjunctions «if, unless, in case, on condition that», and some others).

If he calls, tell him the truth.

I will talk to him if I see him.

I won’t be able to go with you unless I finish this work soon enough.

The adverbial clause of purpose

He works hard so that he can buy a house for his family.

He gave her detailed directions so that she could find his house easily.

They should call her in advance so that she may prepare for their visit.

We left early in order that we might get there before the beginning of the wedding ceremony.

The adverbial clause of result

My car was repaired on Thursday so that on Friday I was able to leave.

I have so much work this week that I won’t be able to go to the concert.

It was so cold that I stayed home.

He was so tired that he fell asleep.

The adverbial clause of reason

I can’t come to the party because I have a cold.

I went home because I was tired.

I called you because I needed money.

Since she didn’t know anyone there, she stayed in her room most of the time.

As there are several possible answers to this question, let’s discuss all of them.

The adverbial clause of comparison

He works as quickly as he can.

Tom is older than I am.

It looks as if it is going to snow.

You sound as if you have a sore throat.

Note that after «as if; as though», the subjunctive mood is used in cases expressing unreality.

He looks as if he were old and sick.

She described it as if she had seen it all with her own eyes.

She loves them as though they were her children.

(See more examples with «as if, as though» at the end of Subjunctive Mood Summary in the section Grammar.)

The adverbial clause of concession

Though he was tired, he kept working.

Although it was already dark, he could still see the shapes of the trees.

He didn’t convince them, although he tried very hard.

No matter what she says, call me at nine o’clock.

Whatever happens, you must help each other.

Find him, whatever happens.

Note: Commas

A comma is generally not used between the main clause and the adverbial subordinate clause if the subordinate clause stands after the main clause. But a comma is used between them if the subordinate clause stands at the beginning of the sentence before the main clause. Compare:

She went for a walk in the park after she had finished her work on the report.

After she had finished her work on the report, she went for a walk in the park.

A comma is used before the adverbial subordinate clause if the subordinate clause refers to the whole main clause (not only to the verb in it). Such situations often occur in the case of the clauses beginning with «though, although, whatever, no matter what» and «because». Compare:

She was absent because she was ill.

They must have been sleeping, because there was no light in their windows.

Types of subordinate clauses in English sources

There are some differences in the way English and Russian linguistic sources describe subordinate clauses, which may present some difficulty for language learners.

In English grammar materials, subordinate clauses are divided into three main types: noun clauses, adjective clauses, and adverb clauses. Adjective clauses (attributive clauses) and adverb clauses (adverbial clauses) are described similarly in English and Russian materials.

Noun clauses are described differently in English materials. Noun clauses include three types of subordinate clauses described in Russian materials: the subject clause, the predicative clause, and the object clause.

Noun clauses

Noun clauses function as nouns. A noun clause can serve as the subject of the sentence, as a predicative noun, or as an object.

What he said was really funny. (Noun clause «What he said» is the subject.)

This is not what I meant. (Noun clause «what I meant» is in the function of predicative noun.)

She says that he will come back tomorrow. (Noun clause «that he will come back tomorrow» is a direct object.)

He is not interested in what she is doing. (Noun clause «what she is doing» is a prepositional object.)

Relative clauses

The term «relative clauses» in English materials refers to noun clauses and adjective clauses introduced by the relative pronouns «who (whom, whose), which, that, what».

Relative clauses in the form of noun clauses are introduced by the relative pronouns «who (whom, whose), which, what».

Who will be able to do it is still a question.

I don’t know which of these bags belongs to her.

I didn’t hear what he said.

Relative clauses in the form of adjective clauses are introduced by the relative pronouns «who (whom, whose), which, that». «Who» refers to persons; «which» refers to things»; «that» refers to things or persons. To avoid possible mistakes, language learners should use «who» (not «that») when referring to people.

The boy who is standing by the door is her nephew. Or: The boy standing by the door is her nephew.

The man to whom she is speaking is her doctor. Or: The man she is speaking to is her doctor.

The house in which he lived was too far from the center of the city. Or: The house he lived in was too far from the city center.

The people whose house he bought moved to Boston.

I lost the pen that you gave me. Or: I lost the pen which you gave me. Or: I lost the pen you gave me.

She likes the stories that he writes. Or: She likes the stories which he writes. Or: She likes the stories he writes.

Relative clauses that have parenthetical character (i.e., nonrestrictive clauses) are separated by commas. Such clauses are usually introduced by the relative pronouns «which» and «who» (whom, whose), but not by «that».

She lost his book, which made him angry.

She doesn’t study hard, which worries her parents.

My brother, who now lives in Greece, invited us to spend next summer at his place.

The war, which lasted nearly ten years, brought devastation and suffering to both countries.

Порядок слов в сложноподчиненных предложениях

Есть пять членов предложения: подлежащее, сказуемое, определение, дополнение, обстоятельство. Соответственно, есть пять типов придаточных предложений: придаточное подлежащее, придаточное сказуемое, придаточное определительное, придаточное дополнительное и несколько типов обстоятельственных придаточных.

Придаточные предложения также называют зависимыми предложениями, т.к. они не могут употребляться без главного предложения. Порядок слов в придаточных – сначала подлежащее, затем глагол. Сравните эти пары простых и сложноподчиненных предложений:

Я купил книгу по истории.

Я купил книгу, которую вы просили.

Я знаю дорогу к его дому.

Я знаю, где он живет.

Он пошел домой после работы.

Он пошел домой после того, как закончил работу.

Придаточное предложение подлежащее

Придаточное предложение подлежащее выполняет функцию подлежащего в предложении. Придаточные подлежащие вводятся словами «who, what, how, when, where, that, whether».

Кто принес розы, секрет.

Что вы мне рассказали, было интересно.

Как это случилось, неясно.

Придаточное подлежащее часто ставится после сказуемого, и в таких предложениях употребляется формальное подлежащее «It».

Неизвестно, кто принес розы.

Неясно, как это случилось.

Сомнительно, что он вернется сегодня.

Придаточное предложение сказуемое

Придаточное предложение сказуемое выполняет функцию именной части составного сказуемого и обычно стоит после глагола-связки BE.

Проблема в том, что он груб.

Вопрос в том, где я могу найти достаточно денег для моего проекта.

Это то, что он ей сказал.

Вот как это случилось.

Определительное придаточное предложение

Определительное придаточное предложение выполняет функцию определения и стоит после существительного, которое оно определяет. Определительные придаточные предложения вводятся словами «who, whom, whose, which, that, when, where, why».

Человек, который помог ей, был доктор Ли.

Сумка, которую он купил, стоила сорок долларов.

Вот книга, о которой я говорю.

Место, где она живет, недалеко отсюда.

Время, когда они были друзьями, ушло.

Дополнительное придаточное предложение

Дополнительные придаточные предложения выполняют функцию дополнения. (Дополнительные придаточные предложения описаны более полно в статье Sequence of Tenses в разделе Grammar.)

Он сказал нам, что уже купил машину.

Я знаю, где мы можем его найти.

Я спросил, как я могу помочь ему.

Типы обстоятельственных придаточных предложений

Обстоятельственные придаточные предложения выполняют функцию обстоятельства. Они включают в себя несколько типов придаточных предложений, которые указывают время, место, цель, причину, результат, условие, уступку, образ действия, сравнение.

Придаточное предложение места

Он пошел (туда), куда я ему сказал.

Этот кот спит (там), где захочет.

Идите по этой улице и остановитесь (там), где дорога поворачивает направо.

Придаточное предложение времени

Когда она приехала, они пошли домой.

Она ушла, когда он спал.

Он не звонил мне с тех пор, как приехал.

Он ушел до того, как я вернулся.

Позвоните мне, как только получите доклад.

Не употребляется будущее время в придаточных предложениях времени, относящихся к будущему (после союзов «when, till, until, after, before, as soon as, as long as, by the time» и некоторых других). Настоящее время, обычно Simple Present (Простое настоящее), употребляется вместо будущего в придаточных предложениях времени.

Он позвонит вам, когда вернется.

Я помогу вам после того, как пообедаю.

Я подожду, пока он не закончит свою работу.

Я сказал, что подожду, пока он не закончит свою работу.

Придаточное предложение условия

Мы поедем к озеру в субботу, если погода будет хорошая.

Если самолет вылетел вовремя, они должны быть в Нью-Йорке сейчас.

Если он уже видел доклад, (то) он знает о наших планах.

Не употребляется будущее время в придаточных предложениях условия, относящихся к будущему времени (после союзов «if, unless, in case, on condition that» и некоторых других).

Если он позвонит, скажите ему правду.

Я поговорю с ним, если увижу его.

Я не смогу пойти с вами, если только не закончу эту работу достаточно скоро.

Придаточное предложение цели

Он много работает, чтобы он мог купить дом для своей семьи.

Он дал ей детальные указания (пути), чтобы она могла легко найти его дом.

Им следует позвонить ей заранее, чтобы она могла подготовиться к их визиту.

Мы выехали пораньше, чтобы мы могли приехать туда до начала свадебной церемонии.

Придаточное предложение результата

Мою машину починили в четверг, так что в пятницу я смог уехать.

У меня столько работы на этой неделе, что я не смогу пойти на концерт.

Было так холодно, что я остался дома.

Он так устал, что заснул.

Придаточное предложение причины

Я не могу прийти на вечеринку, потому что у меня простуда.

Я пошел домой, потому что устал.

Я позвонил вам, так как мне были нужны деньги.

Поскольку она никого там не знала, она оставалась в своей комнате большую часть времени.

Поскольку есть несколько возможных ответов на этот вопрос, давайте обсудим их все.

Придаточное предложение сравнения

Он работает так быстро, как может.

Том старше, чем я.

Выглядит так, как будто пойдет снег.

Вы звучите так, как будто у вас больное горло.

Обратите внимание, что после «as if; as though» употребляется сослагательное наклонение в случаях, выражающих нереальность.

Он выглядит так, как будто он старый и больной.

Она описала это так, как если бы она видела все это своими собственными глазами.

Она любит их так, как будто они ее дети.

(Посмотрите еще примеры с союзами «as if, as though» в конце статьи Subjunctive Mood Summary в разделе Grammar.)

Уступительное придаточное предложение

Хотя он устал, он продолжал работать.

Хотя было уже темно, он все еще мог видеть очертания деревьев.

Он не убедил их, хотя он очень старался.

Что бы она ни говорила, позвоните мне в девять часов.

Что бы ни случилось, вы должны помогать друг другу.

Найди его, что бы ни случилось.

Примечание: Запятые

Запятая обычно не ставится между главным предложением и обстоятельственным придаточным предложением, если придаточное предложение стоит после главного предложения. Но запятая ставится между ними, если придаточное предложение стоит в начале предложения перед главным предложением. Сравните:

Она пошла на прогулку в парк после того, как закончила свою работу над докладом.

После того, как она закончила свою работу над докладом, она пошла на прогулку в парк.

Запятая ставится перед обстоятельственным придаточным предложением, если придаточное предложение относится ко всему главному предложению (а не только к глаголу в нем). Такие ситуации часто возникают в случае придаточных предложений, начинающихся с «though, although, whatever, no matter what» и «because». Сравните:

Она отсутствовала, потому что она была больна.

Они, должно быть, спали, потому что в их окнах не было света.

Типы придаточных предложений в английских источниках

Есть некоторые различия в том, как английские и русские лингвистические источники описывают придаточные предложения, что может представлять трудность для изучающих язык.

В английских материалах по грамматике, придаточные предложения делятся на три основных типа: noun clauses, adjective clauses и adverb clauses. Adjective clauses (attributive clauses) и adverb clauses (adverbial clauses) описываются похожим образом в английских и русских материалах.

Noun clauses описываются по-другому в английских материалах. Noun clauses включают в себя три типа придаточных предложений, описываемых в русских материалах: придаточное предложение подлежащее, придаточное предложение сказуемое и дополнительное придаточное предложение.

Придаточные предложения существительные

Noun clauses выполняют функцию существительных. Noun clause может служить как подлежащее, как именная часть составного сказуемого или как дополнение.

Что он сказал, было действительно смешно. (Noun clause «What he said» – подлежащее.)

Это не то, что я имел в виду. (Noun clause «what I meant» выполняет функцию именной части составного сказуемого.)

Она говорит, что он вернется завтра. (Noun clause «that he will come back tomorrow» – прямое дополнение.)

У него нет интереса к тому, что она делает. (Noun clause «what she is doing» – предложное дополнение.)

Относительные придаточные предложения

Термин «relative clauses» в английских материалах имеет в виду noun clauses и adjective clauses, вводимые относительными местоимениями «who (whom, whose), which, that, what».

Относительные придаточные предложения в виде noun clauses вводятся относительными местоимениями «who (whom, whose), which, what».

Кто сможет это сделать, по-прежнему вопрос.

Я не знаю, которая из этих сумок принадлежит ей.

Я не слышал, что он сказал.

Относительные придаточные предложения в виде adjective clauses вводятся относительными местоимениями «who (whom, whose), which, that». «Who» относится к людям; «which» относится к вещам; «that» относится к вещам или людям. Во избежание возможных ошибок, изучающим язык следует употреблять «who» (а не «that») в отношении людей.

Мальчик, который стоит у двери, ее племянник. Или: Мальчик, стоящий у двери, ее племянник.

Мужчина, с которым она разговаривает, ее врач.

Дом, в котором он жил, был слишком далеко от центра города.

Люди, чей дом он купил, переехали в Бостон.

Я потерял ручку, которую вы мне дали.

Ей нравятся рассказы, которые он пишет.

Относительные придаточные предложения, имеющие характер вводного элемента (т.е. не ограничительные), отделяются запятыми. Такие придаточные предложения обычно вводятся относительными местоимениями «which, who (whom, whose)», но не «that».

Она потеряла его книгу, что разозлило его.

Она мало занимается, что беспокоит ее родителей.

Мой брат, который теперь живет в Греции, пригласил нас провести следующее лето у него.

Война, которая длилась почти десять лет, принесла разорение и страдания обеим странам.

Можно ли использовать вопросительный порядок слов в утвердительных предложениях? Как построить предложение, если в нем нет подлежащего? Об этих и других нюансах читайте в нашей статье.

Прямой порядок слов в английских предложениях

Утвердительные предложения

В английском языке основной порядок слов можно описать формулой SVO: subject – verb – object (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение).

Mary reads many books. — Мэри читает много книг.

Подлежащее — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит в начале предложения (кто? — Mary).

Сказуемое — это глагол, который стоит после подлежащего (что делает? — reads).

Дополнение — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит после глагола (что? — books).

В английском отсутствуют падежи, поэтому необходимо строго соблюдать основной порядок слов, так как часто это единственное, что указывает на связь между словами.

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| My mum | loves | soap operas. | Моя мама любит мыльные оперы. |

| Sally | found | her keys. | Салли нашла свои ключи. |

| I | remember | you. | Я помню тебя. |

Глагол to be в утвердительных предложениях

Как правило, английское предложение не обходится без сказуемого, выраженного глаголом. Так как в русском можно построить предложение без глагола, мы часто забываем о нем в английском. Например:

Mary is a teacher. — Мэри — учительница. (Мэри является учительницей.)

I’m scared. — Мне страшно. (Я являюсь напуганной.)

Life is unfair. — Жизнь несправедлива. (Жизнь является несправедливой.)

My younger brother is ten years old. — Моему младшему брату десять лет. (Моему младшему брату есть десять лет.)

His friends are from Spain. — Его друзья из Испании. (Его друзья происходят из Испании.)

The vase is on the table. — Ваза на столе. (Ваза находится/стоит на столе.)

Подведем итог, глагол to be в переводе на русский может означать:

- быть/есть/являться;

- находиться / пребывать (в каком-то месте или состоянии);

- существовать;

- происходить (из какой-то местности).

Если вы не уверены, нужен ли to be в вашем предложении в настоящем времени, то переведите предложение в прошедшее время: я на работе — я была на работе. Если в прошедшем времени появляется глагол-связка, то и в настоящем он необходим.

Предложения с there is / there are

Когда мы хотим сказать, что что-то где-то есть или чего-то где-то нет, то нам нужно придерживаться конструкции there + to be в начале предложения.

There is grass in the yard, there is wood on the grass. — На дворе — трава, на траве — дрова.

Если в таких типах предложений мы не используем конструкцию there is / there are, то по-английски подобные предложения будут звучать менее естественно:

There are a lot of people in the room. — В комнате много людей. (естественно)

A lot of people are in the room. — Много людей находится в комнате. (менее естественно)

Обратите внимание, предложения с there is / there are, как правило, переводятся на русский с конца предложения.

Еще конструкция there is / there are нужна, чтобы соблюсти основной порядок слов — SVO (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение):

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| There | is | too much sugar in my tea. | В моем чае слишком много сахара. |

Более подробно о конструкции there is / there are можно прочитать в статье «Грамматика английского языка для начинающих, часть 3».

Местоимение it

Мы, как носители русского языка, в английских предложениях забываем не только про сказуемое, но и про подлежащее. Особенно сложно понять, как перевести на английский подобные предложения: Темнеет. Пора вставать. Приятно было пообщаться. В английском языке во всех этих предложениях должно стоять подлежащее, роль которого будет играть вводное местоимение it. Особенно важно его не забыть, если мы говорим о погоде.

It’s getting dark. — Темнеет.

It’s time to get up. — Пора вставать.

It was nice to talk to you. — Приятно было пообщаться.

Хотите научиться грамотно говорить по-английски? Тогда записывайтесь на курс практической грамматики.

Отрицательные предложения

Если предложение отрицательное, то мы ставим отрицательную частицу not после:

- вспомогательного глагола (auxiliary verb);

- модального глагола (modal verb).

| Подлежащее | Вспомогательный/Модальный глагол | Частица not | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sally | has | not | found | her keys. | Салли не нашла свои ключи. |

| My mum | does | not | love | soap operas. | Моя мама не любит мыльные оперы. |

| He | could | not | save | his reputation. | Он не мог спасти свою репутацию |

| I | will | not | be | yours. | Я не буду твоей. |

Если в предложении единственный глагол — to be, то ставим not после него.

| Подлежащее | Глагол to be | Частица not | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter | is | not | an engineer. | Питер не инженер. |

| I | was | not | at work yesterday. | Я не была вчера на работе. |

| Her friends | were | not | polite enough. | Ее друзья были недостаточно вежливы. |

Порядок слов в вопросах

Для начала скажем, что вопросы бывают двух основных типов:

- закрытые вопросы (вопросы с ответом «да/нет»);

- открытые вопросы (вопросы, на которые можно дать развернутый ответ).

Закрытые вопросы

Чтобы построить вопрос «да/нет», нужно поставить модальный или вспомогательный глагол в начало предложения. Получится следующая структура: вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое. Следующие примеры вам помогут понять, как утвердительное предложение преобразовать в вопросительное.

She goes to the gym on Mondays. — Она ходит в зал по понедельникам.

Does she go to the gym on Mondays? — Ходит ли она в зал по понедельникам?

He can speak English fluently. — Он умеет бегло говорить по-английски.

Can he speak English fluently? — Умеет ли он бегло говорить по-английски?

Simon has always loved Katy. — Саймон всегда любил Кэти.

Has Simon always loved Katy? — Всегда ли Саймон любил Кэти?

Обратите внимание! Если в предложении есть только глагол to be, то в Present Simple и Past Simple мы перенесем его в начало предложения.

She was at home all day yesterday. — Она была дома весь день.

Was she at home all day yesterday? — Она была дома весь день?

They’re tired. — Они устали.

Are they tired? — Они устали?

Открытые вопросы

В вопросах открытого типа порядок слов такой же, только в начало предложения необходимо добавить вопросительное слово. Тогда структура предложения будет следующая: вопросительное слово – вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое.

Перечислим вопросительные слова: what (что?, какой?), who (кто?), where (где?, куда?), why (почему?, зачем?), how (как?), when (когда?), which (который?), whose (чей?), whom (кого?, кому?).

He was at work on Monday. — В понедельник он весь день был на работе.

Where was he on Monday? — Где он был в понедельник?

She went to the cinema yesterday. — Она вчера ходила в кино.

Where did she go yesterday? — Куда она вчера ходила?

My father watches Netflix every day. — Мой отец каждый день смотрит Netflix.

How often does your father watch Netflix? — Как часто твой отец смотрит Netflix?

Вопросы к подлежащему

В английском есть такой тип вопросов, как вопросы к подлежащему. У них порядок слов такой же, как и в утвердительных предложениях, только в начале будет стоять вопросительное слово вместо подлежащего. Сравните:

Who do you love? — Кого ты любишь? (подлежащее you)

Who loves you? — Кто тебя любит? (подлежащее who)

Whose phone did she find two days ago? — Чей телефон она вчера нашла? (подлежащее she)

Whose phone is ringing? — Чей телефон звонит? (подлежащее whose phone)

What have you done? — Что ты наделал? (подлежащее you)

What happened? — Что случилось? (подлежащее what)

Обратите внимание! После вопросительных слов who и what необходимо использовать глагол в единственном числе.

Who lives in this mansion? — Кто живет в этом особняке?

What makes us human? — Что делает нас людьми?

Косвенные вопросы

Если вам нужно что-то узнать и вы хотите звучать более вежливо, то можете начать свой вопрос с таких фраз, как: Could you tell me… ? (Можете подсказать… ?), Can you please help… ? (Можете помочь… ?) Далее задавайте вопрос, но используйте прямой порядок слов.

Could you tell me where is the post office is? — Не могли бы вы мне подсказать, где находится почта?

Do you know what time does the store opens? — Вы знаете, во сколько открывается магазин?

Если в косвенный вопрос мы трансформируем вопрос типа «да/нет», то перед вопросительной частью нам понадобится частица «ли» — if или whether.

Do you like action films? — Тебе нравятся боевики?

I wonder if/whether you like action films. — Мне интересно узнать, нравятся ли тебе экшн-фильмы.

Другие члены предложения

Прилагательное в английском стоит перед существительным, а наречие обычно — в конце предложения.

Grace Kelly was a beautiful woman. — Грейс Келли была красивой женщиной.

Andy reads well. — Энди хорошо читает.

Обстоятельство, как правило, стоит в конце предложения. Оно отвечает на вопросы как?, где?, куда?, почему?, когда?

There was no rain last summer. — Прошлым летом не было дождя.

The town hall is in the city center. — Администрация находится в центре города.

Если в предложении несколько обстоятельств, то их надо ставить в следующем порядке:

| Подлежащее + сказуемое | Обстоятельство (как?) | Обстоятельство (где?) | Обстоятельство (когда?) | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fergie didn’t perform | very well | at the concert | two years ago. | Ферги не очень хорошо выступила на концерте два года назад. |

Чтобы подчеркнуть, когда или где что-то случилось, мы можем поставить обстоятельство места или времени в начало предложения:

Last Christmas I gave you my heart. But the very next day you gave it away. This year, to save me from tears, I’ll give it to someone special. — Прошлым Рождеством я подарил тебе свое сердце. Но уже на следующий день ты отдала его обратно. В этом году, чтобы больше не горевать, я подарю его кому-нибудь другому.

Если вы хотите преодолеть языковой барьер и начать свободно общаться с иностранцами, записывайтесь на разговорный курс английского.

Надеемся, эта статья была вам полезной и вы разобрались, как строить предложения в английском языке. Предлагаем пройти небольшой тест для закрепления темы.

Тест по теме «Порядок слов в английском предложении, часть 1»

© 2023 englex.ru, копирование материалов возможно только при указании прямой активной ссылки на первоисточник.

Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper

Порядок важен везде и всюду, тем более если мы говорим о построении предложения в английском. Почему?

Ответ на этот вопрос кроется в морфологии и словообразовании слов.

Если в русском языке определить часть речи и какую функцию она выполняет в предложении нам помогают окончания и суффиксы,

то в английском языке это просто так не прокатит. Возьмите к примеру окончание “s”, которое мы добавляем как к существительным

во множественном числе, так и к глаголам в настоящем времени с местоимениями третьего лица единственного числа.

Важно знать порядок построения и типы, чтобы уметь правильно составить предложения:

утвердительные, вопросительные, отрицательные, придаточные предложения и другие.

Разобраться в грамматике английского языка – задача не из простых, ведь в ней столько разных тем на разных уровнях,

но с командой Инглиш Шоу она больше не будет казаться вам непосильной.

Записывайтесь на бесплатный пробный урок в нашу онлайн-школу

и оцените преимущества изучения языка с опытным преподавателем, не выходя из дома!

Содержание

- Прямой порядок слов в утвердительных английских предложениях

- Порядок слов в вопросительных предложениях

- Как строятся отрицательные предложения в английском?

- Место наречий в английском предложении

- Порядок употребления прилагательных в предложении

- Порядок слов в сложном предложении

- Особые случаи построения английских предложений

Прямой порядок слов в утвердительных английских предложениях

Прежде чем начать говорить об особенностях построения утвердительных предложений нужно сказать,

что в грамматике английского языка выделяют две формы порядка слов в предложении: Direct Order — правильный порядок слов,

который характеризует повествовательное предложение и Indirect Order — непрямой, который используется для вопросов,

восклицательных предложений или императивов, то есть повелительного наклонения.

Теперь давайте вспомним, что же представляют из себя члены предложения и какие они бывают. Грамматическую основу составляют:

Подлежащее

— это часть речи, которая отвечает на вопросы «Кто?» или «Что?». Подлежащее — это тот, кто выполняет действие.

Оно может быть выражено существительным, местоимением, инфинитивом или герундием.

-

Diving is a very popular extreme sport activity.

Дайвинг является очень популярным экстремальным видом спорта. -

The squirrel is cracking nuts.

Белочка грызет орехи.

Сказуемое

— это глагол, описывающий состояние субъекта или действие.

Важно: в русском языке мы зачастую не употребляем глагол «быть», мы его просто опускаем. В английском же он жизненно необходим.

-

She is a student.

Она студент.

Так мы литературно передадим смысл предложения. Но если перевести дословно, то мы скажем:

Она является студентом. Можно провести параллель с русским словом «есть, являться, существовать».

Стоит отметить, что во многих романо-германских языках «быть» — это основополагающий глагол, который невозможно опустить в предложении.

Помимо грамматической основы предложения (подлежащее и сказуемое) существуют второстепенные члены предложения:

Дополнение

— это то, над кем/чем совершается действие. Оно выражается существительным или герундием.

-

Marta gave me a postcard.

Марта подарила мне открытку.

Определение

— отвечает на вопросы «Какой?», «Какая?», «Чей?» и так далее. Определение выражает признаки субъекта или объекта.

Определение, как правило, стоит перед существительным.

-

Rick didn’t like his third girlfriend.

Рику не нравилась его третья девушка. -

The scientist was studying an important issue.

Ученый изучал очень важный вопрос.

Обстоятельство

— отвечает на такие вопросы как: «Где?», «Когда?», «Как?», «Как часто?», и обычно выражено наречием.

В зависимости от контекста и вида обстоятельства они могут располагаться в конце, начале и в середине предложения.

Подводя некий итог, можно собрать всё в единую универсальную схему в утвердительном предложении:

Subject + Verb + Object + Adverb

Подлежащее + Сказуемое + Дополнение + Обстоятельство

Порядок слов в вопросительных предложениях

Когда мы задаем вопрос, то нарушается прямая последовательность «подлежащее – сказуемое»,

и в этом случае мы используем Indirect Order – обратный порядок слов. Для каждого из пяти основных типов вопросов используется

свой порядок слов, но всё же можно выделить основную закономерность.

Как возможно вы знаете из базового школьного курса по английскому, на первое место в general questions (общих вопросах)

мы ставим глагол-помощник, который у каждого времени свой.

-

Do you speak English?

Ты говоришь по-английски?

Данное правило является универсальным для большинства вопросов. В special questions (специальных вопросах)

мы только добавляем специальное вопросительное слово в начало, при этом сохраняя конструкцию общего вопроса.

-

How often do you speak English?

Как часто ты говоришь на английском?

Если же мы возьмем alternative questions (альтернативные вопросы), то здесь он начинается точно также как и общий,

только потом мы добавляем альтернативу с помощью союза or (или).

-

Do you go surfing or sup-surfing?

Ты занимаешься сёрфингом или сап-серфингом?

Подробнее про образование всех типов вопросов читайте в нашей статье:

«Типы вопросов в английском языке»

Как строятся отрицательные предложения в английском?

Так же, как и в вопросительных предложениях, в отрицательных необходим глагол помощник.

Он служит некой связующей нитью для отрицательной частички not.

Ставится он при этом между подлежащим и сказуемым.

-

I do not know the rules of the game.

Я не знаю правил этой игры. -

They did not clean their room yesterday.

Они не убрались в своей комнате вчера.

Место наречий в английском предложении

Наречие может занимать своё законное место в разных частях предложения.

В конце предложения обычно можно встретить обстоятельства образа действия, места и времени.

-

Kate is walking really fast.

Кейт идёт очень быстро. -

Tony has decorated his room today.

Тони украсил свою комнату сегодня.

В начале предложения можно встретить:

Соединительные наречия: then — тогда, next — затем

-

Then we headed for the train.

Затем мы отправились к поезду.

Вводные наречия выражения мнения: surprisingly — неожиданно, unfortunately — к сожалению

-

Unfortunately, I forgot to take my purse.

К сожалению, я забыла взять мою сумочку.

Наречия степени уверенности: maybe, perhaps — может быть

-

Perhaps the flight has been delayed.

Возможно, рейс был задержан.

Также некоторые обстоятельства используются в середине грамматической основы, например после подлежащего, вспомогательных глаголов или после глагола to be.

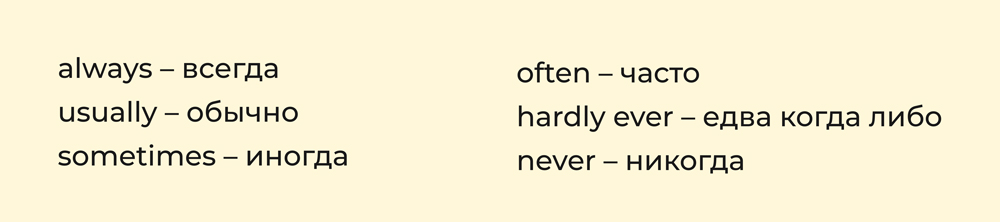

К этой группе относятся наречия частоты:

-

I always get up early in the morning.

Я всегда встаю рано утром. -

He is never late for work.

Он никогда не опаздывает на работу.

Любопытно, что sometimes в отличие от других наречий частоты, может стоять в любом месте в предложении.

С помощью такого приема мы можем легко привлечь внимание собеседника.

-

I go to the restaurant just sometimes.

Я хожу в ресторан только иногда.

Также это наречия, указывающие на законченность действия:

almost, nearly – почти

already – уже

just – только что

-

I have just done my homework.

Я только что закончила мою домашнюю работу.

Или на степень уверенности говорящего:

probably – наверное

confidently – уверенно

surely – наверняка

definitely – определенно точно

-

Her attitude has definitely changed for the better since she started this new job.

Её поведение определенно изменилось к лучшему с тех пор, как она начала новую работу.

Порядок употребления прилагательных в предложении

Далеко не секрет, что прилагательные ставятся перед существительными, в этом случае действует такая же система, как и в русском языке.

Но если прилагательных несколько, то употребляются они в определенной последовательности. А именно:

judgement – size – shape – colour – origin – material – purpose

оценка – размер – форма – цвет – происхождение – материал – цель

-

I adore your long, red, Chinese, silk curtains.

Я восхищаюсь твоими длинными, красными, китайскими, шелковыми шторами. -

What you need for your living room is a large oak dining table.

То, что тебе нужно для гостиной это большой дубовый обеденный стол.

После существительного используют определение, которое представляет из себя причастный оборот или конструкцию из нескольких слов.

-

My brother is fond of food made of soya.

Мой брат в восторге от еды из сои.

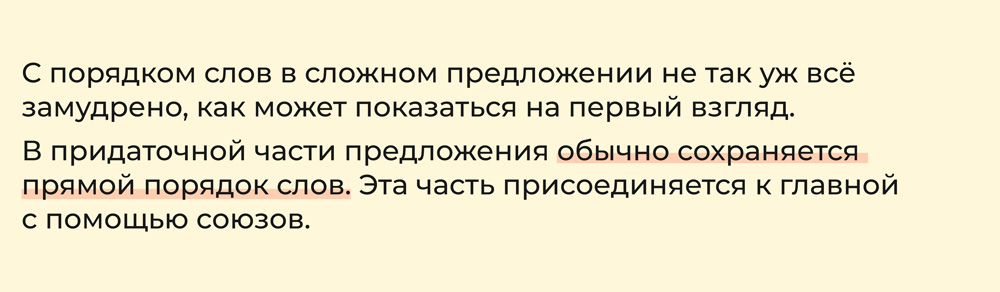

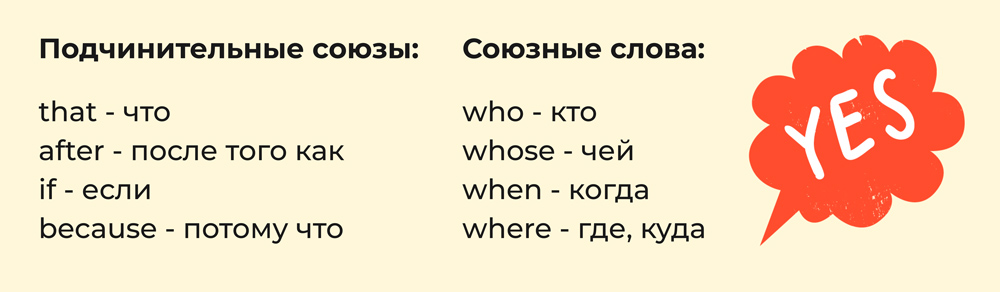

Порядок слов в сложном предложении

По видам сложные предложения бывают:

The compound sentence – сложносочиненное предложение, в котором простые предложения могут соединяться такими союзами как:

and — и

neither … nor — ни …, ни

as well as — так же как

not only … but also — не только … но и

but — но

-

A cold wind was blowing and a snowstorm began.

Дул холодный ветер, и начиналась метель. -

In her view, that relationship was neither substantial nor crucial.

По мнению оратора, эта взаимосвязь не является ни существенной, ни определяющей.

The complex sentence – сложноподчиненное предложение. Придаточное предложение присоединяется к главному предложению с помощью:

-

I went there when I was a child.

Я ходил туда, когда был ребенком. -

I’ve been meaning to ask you where you get your hair cut.

Я хотел спросить тебя, где ты постриглась.

Таким образом, схема сложного предложения будет выглядеть так:

Main clause + conjunction + Subordinate clause

Главная часть + союз + Придаточная часть

Особые случаи построения английских предложений

К особым случаям построения предложений относится повелительный залог, то есть приказания или повеления.

В этом случае на первом месте будет стоять либо глагол, либо вспомогательный глагол (в случае отрицания).

-

Close the window!

Закрой окно! -

Don’t touch my stuff!

Не трогай мои вещи!

Иногда добавляют обращение в начале:

-

You! Get away from here!

Ты! Убирайся отсюда!

Далее следует вспомнить про конструкции there is / there are. Их мы используем, когда хотим сказать о существовании чего-либо.

There обычно означает там, но в этих конструкциях не переводится. There is – мы употребляем с предметами в единственном числе,

а there are – во множественном. Схема предложений выглядит следующим образом:

There is/are + subject (подлежащее) + object (дополнение)

-

There is a glass on the table.

Вот стакан на столе. -

There are some changes in the schedule.

Есть некоторые изменения в расписании.

Однако, если есть два дополнения, то они ставятся по следующему принципу: сначала косвенное дополнение без предлога, затем прямое дополнение.

-

Steven lent me a pen.

Стивен одолжил мне ручку.

Либо если у вас есть желание поставить сначала прямое дополнение, то косвенное будет использоваться с предлогом to.

-

Marry sent a postcard to her boyfriend.

Мери отправила открытку своему бойфренду.

Таким образом, можно сделать следующий вывод:

Прямой порядок слов используется в утверждениях и отрицаниях.

Непрямой порядок используется в вопросах, повелительных предложениях, конструкциях there is / there are.

Если вы изучаете английский уже не первый год, то наверняка успели убедиться в его многообразии.

Известно, что ни один язык невозможно знать в совершенстве, и английский превосходит все языки в этом отношении, судя только по тому,

что каждый год в Оксфордском словаре прибавляется минимум по тысяче новых слов!

Именно поэтому преподаватели Инглиш Шоу непрестанно следят за всеми «новыми словечками» и языковыми трендами

и с радостью готовы поделиться с вами всеми лайфхаками изучения языка. А первое занятие для вас будет в подарок от нашей школы!

Ждём вас с нетерпением на наших уроках и до новых встреч!

Welcome to the ELB Guide to English Word Order and Sentence Structure. This article provides a complete introduction to sentence structure, parts of speech and different sentence types, adapted from the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences. I’ve prepared this in conjunction with a short 3-video course, currently in editing, to help share the lessons of the book to a wider audience.

You can use the headings below to quickly navigate the topics:

- Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

- Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

- Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

- Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

- Parts of Speech

- Nouns, Determiners and Adjectives

- Pronouns

- Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Adverbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Clauses, Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

There are lots of ways to break down sentences, for different purposes. This article covers the systems I’ve found help my students understand and form accurate sentences, but note these are not the only ways to explore English grammar.

I take three approaches to introducing English grammar:

- Studying overall patterns, grouping sentence components by their broad function (subject, verb, object, etc.)

- Studying different word types (the parts of speech), how their phrases are formed and their places in sentences

- Studying groupings of phrases and clauses, and how they connect in simple, compound and complex sentences

Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

English belongs to a group of just under half the world’s languages which follows a SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT order. This is the starting point for all our basic clauses (groups of words that form a complete grammatical idea). A standard declarative clause should include, in this order:

- Subject – who or what is doing the action (or has a condition demonstrated, for state verbs), e.g. a man, the church, two beagles

- Verb – what is done or what condition is discussed, e.g. to do, to talk, to be, to feel

- Additional information – everything else!

In the correct order, a subject and verb can communicate ideas with immediate sense with as little as two or three words.

- Gemma studies.

- It is hot.

Why does this order matter? We know what the grammatical units are because of their position in the sentence. We give words their position based on the function we want them to convey. If we change the order, we change the functioning of the sentence.

- Studies Gemma

- Hot is it

With the verb first, these ideas don’t make immediate sense and, depending on the verbs, may suggest to English speakers a subject is missing or a question is being formed with missing components.

- The alien studies Gemma. (uh oh!)

- Hot, is it? (a tag question)

If we don’t take those extra steps to complete the idea, though, the reversed order doesn’t work. With “studies Gemma”, we couldn’t easily say if we’re missing a subject, if studies is a verb or noun, or if it’s merely the wrong order.

The point being: using expected patterns immediately communicates what we want to say, without confusion.

Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

Understanding this basic pattern is useful for when we start breaking down more complicated sentences; you might have longer phrases in place of the subject or verb, but they should still use this order.

| Subject | Verb |

| Gemma | studies. |

| A group of happy people | have been quickly walking. |

After subjects and verbs, we can follow with different information. The other key components of sentence patterns are:

- Direct Object: directly affected by the verb (comes after verb)

- Indirect Objects: indirectly affected by the verb (typically comes between the verb and a direct object)

- Prepositional phrases: noun phrases providing extra information connected by prepositions, usually following any objects

- Time: describing when, usually coming last

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Gemma | studied | English | in the library | last week. | |

| Harold | gave | his friend | a new book | for her birthday | yesterday. |

The individual grammatical components can get more complicated, but that basic pattern stays the same.

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Our favourite student Gemma | has been studying | the structure of English | in the massive new library | for what feels like eons. | |

| Harold the butcher’s son | will have given | the daughter of the clockmaker | an expensive new book | for her coming-of-age festival | by this time next week. |

The phrases making up each grammatical unit follow their own, more specific rules for ordering words (covered below), but overall continue to fit into this same basic order of components:

Subject – Verb – Indirect Object – Direct Object – Prepositional Phrase – Time

Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

Subject-Verb-Object is a starting point that covers positive, declarative sentences. These are the most common clauses in English, used to describe factual events/conditions. The type of verb can also make a difference to these patterns, as we have action/doing verbs (for activities/events) and linking/being verbs (for conditions/states/feelings).

Here’s the basic patterns we’ve already looked at:

- Subject + Action Verb – Gemma studies.

- Subject + Action Verb + Object – Gemma studies English.

- Subject + Action Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object – Gemma gave Paul a book.

We might also complete a sentence with an adverb, instead of an object:

- Subject + Action Verb + Adverb – Gemma studies hard.

When we use linking verbs for states, senses, conditions, and other occurrences, the verb is followed by noun or adjective phrases which define the subject.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Noun Phrase – Gemma is a student.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Phrase – Gemma is very wise.

These patterns all form positive, declarative sentences. Another pattern to note is Questions, or interrogative sentences, where the first verb comes before the subject. This is done by adding an auxiliary verb (do/did) for the past simple and present simple, or moving the auxiliary verb forward if we already have one (to be for continuous tense, or to have for perfect tenses, or the modal verbs):

- Gemma studies English. –> Does Gemma study English?

- Gemma is very wise. –> Is Gemma very wise?

For more information on questions, see the section on verbs.

Finally, we can also form imperative sentences, when giving commands, which do not need a subject.

- Study English!

(Note it is also possible to form exclamatory sentences, which express heightened emotion, but these depend more on context and punctuation than grammatical components.)

Parts of Speech

General patterns offer overall structures for English sentences, while the broad grammatical units are formed of individual words and phrases. In English, we define different word types as parts of speech. Exactly how many we have depends on how people break them down. Here, we’ll look at nine, each of which is explained below. Either keep reading or click on the word types to go to the sections about their word order rules.

- Nouns – naming words that define someone or something, e.g. car, woman, cat

- Pronouns – words we use in place of nouns, e.g. he, she, it

- Verbs – doing or being words, describing an action, state or experience e.g. run, talk, be

- Adjectives – words that describe nouns or pronouns, e.g. cheerful, smelly, loud

- Adverbs – words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, sentences themselves – anything other nouns and pronouns, basically, e.g. quickly, curiously, weirdly

- Determiners – words that tell us about a noun’s quantity or if it’s specific, e.g. a, the, many

- Prepositions – words that show noun or noun phrase positions and relationships, e.g. above, behind, in, on

- Conjunctions – words that connect words, phrases or clauses e.g. and, but

- Interjections – words that express a single emotion, e.g. Hey! Ah! Oof!

For more articles and exercises on all of these, be sure to also check out ELB’s archive covering parts of speech.

Noun Phrases, Determiners and Adjectives

Subjects and objects are likely to be nouns or noun phrases, describing things. So sentences usually to start with a noun phrase followed by a verb.

- Nina ate.

However, a noun phrase may be formed of more than word.

We define nouns with determiners. These always come first in a noun phrase. They can be articles (a/an/the – telling us if the noun is specific or not), or can refer to quantities (e.g. some, much, many):

- a dog (one of many)

- the dog in the park

- many dogs

After determiners, we use adjectives to add description to the noun:

- The fluffy dog.

You can have multiple adjectives in a phrase, with orders of their own. You can check out my other article for a full analysis of adjective word order, considering type, material, size and other qualities – but a starting rule is that less definite adjectives go first – more specific qualities go last. Lead with things that are more opinion-based, finish with factual elements:

- It is a beautiful wooden chair. (opinion before fact.)

We can also form compound nouns, where more than one noun is used, e.g. “cat food”, “exam paper”. The earlier nouns describe the final noun: “cat food” is a type of food, for cats; an “exam paper” is a specific paper. With compound nouns you have a core noun (the last noun), what the thing is, and any nouns before it describe what type. So – description first, the actual thing last.

Finally, noun phrases may also include conjunctions joining lists of adjectives or nouns. These usually come between the last two items in a list, either between two nouns or noun phrases, or between the last two adjectives in a list:

- Julia and Lenny laughed all day.

- a long, quick and dangerous snake

Pronouns

We use pronouns in the place of nouns or noun phrases. For the most part, these fit into sentences the same way as nouns, in subject or object positions, but don’t form phrases, as they replace a whole noun phrase – so don’t use describing words or determiners with pronouns.

Pronouns suggest we already know what is being discussed. Their positions are the same as nouns, except with phrasal verbs, where pronouns often have fixed positions, between a verb and a particle (see below).

Verbs

Verb phrases should directly follow the subject, so in terms of parts of speech a verb should follow a noun phrase, without connecting words.

As with nouns and noun phrases, multiple words may make up the verb component. Verb phrases depend on your tenses, which follow particular forms – e.g. simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous. The specifics of verb phrases are covered elsewhere, for example the full verb forms for the tenses are available in The English Tenses Practical Grammar Guide. But in terms of structure, with standard, declarative clauses the ordering of verb phrases should not change from their typical tense forms. Other parts of speech do not interrupt verb phrases, except for adverbs.

The times that verb phrases do change their structure are for Questions and Negatives.

With Yes/No Questions, the first verb of a verb phrase comes before the subject.

- Neil is running. –> Is Neil running?

This requires an auxiliary verb – a verb that creates a grammatical function. Many tenses already have an auxiliary verb – to be in continuous tenses (“is running”), or to have in perfect tenses (have done). For these, to make a question we move that auxiliary in front of the subject. With the past and present simple tenses, for questions, we add do or did, and put that before the subject.

- Neil ran. –> Did Neil run?

We can also have questions that use question words, asking for information (who, what, when, where, why, which, how), which can include noun phrases. For these, the question word and any noun phrases it includes comes before the verb.

- Where did Neil Run?

- At what time of day did Neil Run?

To form negative statements, we add not after the first verb, if there is already an auxiliary, or if there is not auxiliary we add do not or did not first.

- Neil is running. –> Neil is not

- Neil ran. Neil did not

The not stays behind the subject with negative questions, unless we use contractions, where not is combined with the verb and shares its position.

- Is Neil not running?

- Did Neil not run?

- Didn’t Neil run?

Phrasal Verbs

Phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs, often with very specific meanings. They include at least a verb and a particle, which usually looks like a preposition but functions as part of the verb, e.g. “turn up“, “keep on“, “pass up“.

You can keep phrasal verb phrases all together, as with other verb phrases, but they are more flexible, as you can also move the particle after an object.

- Turn up the radio. / Turn the radio up.

This doesn’t affect the meaning, and there’s no real right or wrong here – except with pronouns. When using pronouns, the particle mostly comes after the object:

- Turn it up. NOT Turn up it.

For more on phrasal verbs, check out the ELB phrasal verbs master list.

Adverbs

Adverbs and adverbial phrases are really tricky in English word order because they can describe anything other than nouns. Their positions can be flexible and they appear in unexpected places. You might find them in the middle of verb phrases – or almost anywhere else in a sentence.

There are many different types of adverbs, with different purposes, which are usually broken down into degree, manner, frequency, place and time (and sometimes a few others). They may be single words or phrases. Adverbs and adverb phrases can be found either at the start of a clause, the end of a clause, or in a middle position, either directly before or after the word they modify.

- Graciously, Claire accepted the award for best student. (beginning position)

- Claire graciously accepted the award for best student. (middle position)

- Claire accepted the award for best student graciously. (end position)

Not all adverbs can go in all positions. This depends on which type they are, or specific adverb rules. One general tip, however, is that time, as with the general sentence patterns, should usually come last in a clause, or at the very front if moved for emphasis.

With verb phrases, adverbs often either follow the whole phrase or come before or after the first verb in a phrase (there are regional variations here).

For multiple adverbs, there can be a hierarchy in a similar way to adjectives, but you shouldn’t often use many adverbs together.

The largest section of the Word Order book discusses adverbs, with exercises.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, generally, demonstrate relationships between noun phrases (e.g. by, on, above). They mostly come before a noun phrase, hence the name pre-position, and tend to stick with the noun phrase they describe, so move with the phrase.

- They found him [in the cupboard].

- [In the cupboard,] they found him.

In standard sentence structure, prepositional phrases often follow verbs or other noun phrases, but they may also be used for defining information within a noun phrases itself:

- [The dog in sunglasses] is drinking water.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions connect lists in noun phrases (see nouns) or connect clauses, meaning they are found between complete clauses. They can also come at the start of a sentence that begins with a subordinate clause, when clauses are rearranged (see below), but that’s beyond the standard word order we’re discussing here. There’s more information about this in the article on different sentence types.

As conjunctions connect clauses, they come outside our sentence and word type patterns – if we have two clauses following subject-verb-object, the conjunction comes between them:

|

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

Conjunction |

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

|

He |

washed |

the car |

while |

she |

ate |

a pie. |

Interjections

These are words used to show an emotion, usually something surprising or alarming, often as an interruption – so they can come anywhere! They don’t normally connect to other words, as they are either used to get attention or to cut off another thought.

- Hey! Do you want to go swimming?

- OH NO! I forgot my homework.

Clauses and Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

While a phrase is any group of words that forms a single grammatical unit, a clause is when a group of words form a complete grammatical idea. This is possible when we follow the patterns at the start of this article, for example when we combine a subject and verb (or noun phrase and verb phrase).

A single clause can follow any of the patterns we’ve already discussed, using varieties of the word types covered; it can be as simple a two-word subject-verb combo, or it may include as many elements as you can think of:

- Eric sat.

- The boy spilt blue paint on Harriet in the classroom this morning.

As long as we have one main verb and one main subject, these are still single clauses. Complete with punctuation, such as a capital letter and full stop, and we have a complete sentence, a simple sentence. When we combine two or more clauses, we form compound or complex sentences, depending on the clauses relationships to each other. Each type is discussed below.

Simple Sentences

A sentence with one independent clause is what we call a simple sentence; it presents a single grammatically complete action, event or idea. But as we’ve seen, just because the sentence structure is called simple it does not mean the tenses, subjects or additional information are simple. It’s the presence of one main verb (or verb phrase) that keeps it simple.

Our additional information can include any number of objects, prepositional phrases and adverbials; and that subject and verb can be made up of long noun and verb phrases.

Compound Sentences

We use conjunctions to bring two or more clauses together to create a compound sentence. The clauses use the same basic order rules; just treat the conjunction as a new starting point. So after one block of subject-verb-object, we have a conjunction, then the next clause will use the same pattern, subject-verb-object.

- [Gemma worked hard] and [Paul copied her].

See conjunctions for another example.

A series of independent clauses can be put together this way, following the expected patterns, joined by conjunctions.

Compound sentences use co-ordinating conjunctions, such as and, but, for, yet, so, nor, and or, and do not connect the clauses in a dependent way. That means each clause makes sense on its own – if we removed the conjunction and created separate sentences, the overall meaning would remain the same.

With more than two clauses, you do not have to include conjunctions between each one, e.g. in a sequence of events:

- I walked into town, I visited the book shop and I bought a new textbook.

And when you have the same subject in multiple clauses, you don’t necessarily need to repeat it. This is worth noting, because you might see clauses with no immediate subject:

- [I walked into town], [visited the book shop] and [bought a new textbook].

Here, with “visited the book shop” and “bought a new textbook” we understand that the same subject applies, “I”. Similarly, when verb tenses are repeated, using the same auxiliary verb, you don’t have to repeat the auxiliary for every clause.

What about ordering the clauses? Independent clauses in compound sentences are often ordered according to time, when showing a listed sequence of actions (as in the example above), or they may be ordered to show cause and effect. When the timing is not important and we’re not showing cause and effect, the clauses of compound sentences can be moved around the conjunction flexibly. (Note: any shared elements such as the subject or auxiliary stay at the front.)

- Billy [owned a motorbike] and [liked to cook pasta].

- Billy [liked to cook pasta] and [owned a motorbike].

Complex Sentences

As well as independent clauses, we can have dependent clauses, which do not make complete sense on their own, and should be connected to an independent clause. While independent clauses can be formed of two words, the subject and verb, dependent clauses have an extra word that makes them incomplete – either a subordinating conjunction (e.g. because, when, since, if, after and although), or a relative pronoun, (e.g. that, who and which).

- Jim slept.

- While Jim slept,

Subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns create, respectively, a subordinate clause or a relative clause, and both indicate the clause is dependent on more information to form a complete grammatical idea, to be provided by an independent clause:

- While Jim slept, the clowns surrounded his house.

In terms of structure, the order of dependent clauses doesn’t change from the patterns discussed before – the word that comes at the front makes all the difference. We typically connect independent clauses and dependent clauses in a similar way to compound sentences, with one full clause following another, though we can reverse the order for emphasis, or to present a more logical order.

- Although she liked the movie, she was frustrated by the journey home.

(Note: when a dependent clause is placed at the beginning of a sentence, we use a comma, instead of another conjunction, to connect it to the next clause.)

Relative clauses, those using relative pronouns (such as who, that or which), can also come in different positions, as they often add defining information to a noun or take the place of a noun phrase itself.

- The woman who stole all the cheese was never seen again.

- Whoever stole all the cheese is going to be caught one day.

In this example, the relative clause could be treated, in terms of position, in the same way as a noun phrase, taking the place of an object or the subject:

- We will catch whoever stole the cheese.

For more information on this, check out the ELB guide to simple, compound and complex sentences.

That’s the end of my introduction to sentence structure and word order, but as noted throughout this article there are plenty more articles on this website for further information. And if you want a full discussion of these topics be sure to check out the bestselling guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook on this site and from all major retailers in paperback format.

Get the Complete Word Order Guide

This article is expanded upon in the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook and paperback.

If you found this useful, check out the complete book for more.