What is word order in poetry?

“Word order” simply refers to the order in which words are arranged in the poem. Does the poet use a conventional sentence structure, or does he invert the order of words so that the subject comes after the verb, for example? The first line, “We real cool,” has no verb.

What is normal word order?

The standard word order in English is: Subject + Verb + Object. To determine the proper sequence of words, you need to understand what the subject, verb and object(s) are.

What is the most common word order?

SOV

How do you use the word order?

We use in order to with an infinitive form of a verb to express the purpose of something. It introduces a subordinate clause. It is more common in writing than in speaking: [main clause]Mrs Weaver had to work full-time [subordinate clause]in order to earn a living for herself and her family of five children.

What is the effect of putting the words in correct order?

If we put words incorrectly phrases are not able to understand by the readers. Using approriate and correct words are important. Also, addressing your intended readers in an appropriate manner with accuracy and free from errors or gramatically correct.

What is word order strategy?

A word-order convention can be thought of as a perceptual strategy that a speakerhearer can use in order to comprehend a sentence (cf. Bever, 1970a; 1970b; Slobin & Bever, 1982). Such a strategy would be useful for English where the SVO order is, in fact, prevalent.

What’s another way of saying in order to?

What is another word for in order to?

| to | so as to |

|---|---|

| as a means to | for the purpose of |

| that one may | that it would be possible to |

| with the aim of | in order to achieve |

| so as to achieve | for |

What means conducive?

: tending to promote or assist an atmosphere conducive to education.

How do you say first step in different ways?

other words for first step

- dawn.

- kickoff.

- opening.

- outset.

- dawning.

- foundation.

- origin.

- spring.

What is another name for basic?

What is another word for basic?

| essential | fundamental |

|---|---|

| vital | elementary |

| crucial | elemental |

| important | indispensable |

| principal | cardinal |

What is the first step called?

commencement, start, beginning.

What is another word for step?

Step Synonyms – WordHippo Thesaurus….What is another word for step?

| footstep | pace |

|---|---|

| stride | stepping |

| tread | footfall |

| stamp | stomp |

| plod |

What word rhymes with step?

- syllable: beppe, cep, dep, depp, deppe, dscs slep, epp, hep, hepp, heppe, jeppe, kepp, kleppe, knepp, lep, lepp, pep, prep, rep, repp, schep, schepp, schlep, schlepp, schnepp, schweppe, sep, sepp, shep, shepp, shlep, shlepp, sprep, step-, stepp, steppe, strep, treppe, vgrep, yep, zepp.

- syllables:

- syllables:

What is the one word for to move with high steps?

The Crossword Solver found 20 answers to the move with high steps crossword clue….

| move with high steps | |

|---|---|

| Moving with high speed. (5) | |

| RAPID | |

| High-step | |

| STRUT |

What do you call the step-by-step?

step-by-step

- gradational,

- gradual,

- incremental,

- phased,

- piecemeal.

Is it step by step or step by step?

If you do something step by step, you do it by progressing gradually from one stage to the next. I am not rushing things and I’m taking it step by step.

What are steps?

1 : a movement made by lifting one foot and putting it down in another spot. 2 : a rest or place for the foot in going up or down : stair. 3 : a combination of foot and body movements in a repeated pattern a dance step. 4 : manner of walking a lively step.

How do you spell steps?

Correct spelling for the English word “steps” is [stˈɛps], [stˈɛps], [s_t_ˈɛ_p_s] (IPA phonetic alphabet).

What is the full form of step?

STEP. structured test and evaluation process, 14. Government. STEP. Standard for Exchange of Product Model Data (iso 10303)

What is the full meaning of step?

Safety Training And Evaluation Process. Governmental » US Government. Rate it: STEP. Science And Technology Entry Program.

What do you call the last step?

1 aftermost, at the end, hindmost, rearmost.

Is a culmination?

The culmination is the end point or final stage of something you’ve been working toward or something that’s been building up. A culmination isn’t just the conclusion. It’s the climax of the story, the final crowning achievement, the end result of years of research.

What is the space between stairs called?

Spandrel

What is a curtail step?

noun. the step or steps at the foot of a flight of stairs, widened at one or both ends and terminated with a scroll.

-

#1

Hi All,

You could help me very much, if you could tell me, whether, in a poem,

the (as I think, unusual) word order in the following verse would be acceptable:

колонна величественная белого света

(instead of «величественная колонна белого света»).

Or, maybe, even in a poem, you couldn’t say it at all??!!!

Thanks so much in anticipation

Why Not?

-

#2

колонна величественная белого света

(instead of «величественная колонна белого света»).

Or, maybe, even in a poem, you couldn’t say it at all??!!!

Word order in Russian poetry is extremely flexible. Your version is quite acceptable.

-

#3

Yes, I agree. You can play with word order, even more than in English.

I connected with Margaret Atwood’s poem “Bored” on a somewhat personal level based on what I gathered from it–she is reminiscing back to when she was a young girl and would do what she thought then were boring and monotonous tasks with her father, and she could not wait to “get the hell out of there to anywhere else”. However, now she realizes that those were the good times and she should have treasured those innocent moments when she was still naive to the world.

Throughout the poem, Atwood uses several different types of diction. The majority of the poem is written with informal diction, even a bit colloquially, because she is reflecting back on her younger self and is using the type of language she would have used at that age in a rather conversational manner. There is, however, a portion in the middle of the poem where she is using very vivid language to describe the things she saw on the boat with her father where the diction gets a bit more formal–“Myopia. The worn gunwales, the intricate twill of the seat cover. The acid crumbs of loam, the granular pink rock, its igneous veins, the sea-fans of dry moss, the blackish and then the greying bristles on the back of his neck…Such minutiae.” The diction almost took on a scientific jargon while describing the loam and rocks which certainly gave the words a more denotative meaning than connotative, which is unusual in poetry. There were even two words that I had to look up to find the meaning of: myopia (nearsightedness) and minutiae (the small, precise, or trivial details of something).

While many poets take on a persona while writing, I like to this that Atwood is writing on a more personal level about herself because she described this poem as one of the ones she wrote about her father and his death. I think that writing this from experience makes the overall tone of ruefulness even more powerful because reading it through the first time, I thought the regret was just from not appreciating her naivety but after reading the “Considerations for Critical Thinking and Writing”, I realized is was more so about wishing she had cherished the seemingly boring moments with her father more than she had because you never know when any moment could be your last.

-

Index

- Basic Syntax

- Word Order

- Prose Style

- Poetic Style

- Syntax Overview

Poetic Style

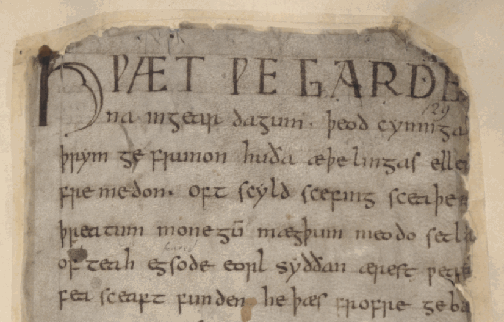

Almost all surviving Old English poetry is

alliterative, meaning it creates rhythm using a pattern of

stressed syllables that begin with the same sound.

To adhere to the alliteration and meter, word order is often more fluid in poetry compared to prose

and poets employ a number of rhetorical

devices such as appositives:

repitition of identity using a different phrase;

and kennings: compound words which use figurative language to describe an object.

These can make sentence structures confusing if you are unfamiliar with them so we will cover them here.

Also, it is worth noting that although Old English poetry is written identically to prose in

manuscripts,

editors often break poetry into lines and half-lines to make it easier for a modern reader — who may be

unfamiliar with the meter — to understand. So while the opening to Beowulf looks like this in the

manuscript:

Modern editions of the poem often break up the text to look like this:

Hwæt we Gardena in

gear dagum

þeod cyninga þrym gefrunon

hu þa aðelingas ellen fremedon

To understand why, we need to examine the meter of Old English verse. It is important to remember that

Old English poetry is generally agreed to be composed for oral recitation, rather than simply to be

read.

Alliteration and Stress

Alliteration is the repetition of a sound at the beginning of a syllable and stress is

the emphasis placed on a syllable. The primary stress generally falls on the first syllable of a word, unless it starts with a

prefix like ‘ge‘, as prefixes are always unstressed.

A line of poetry in Old English consists of two half-lines seperated by a natural pause known as a

caesura, and each half-line has two stressed

syllables.

The first

heavily stressed syllable in the first half-line alliterates with the first heavily stressed syllable of

the second half-line. Unaccented syllables are irrelevant to the metrical pattern. For example,

in the line: ‘Oft him anhaga are gebideð — Often the loner finds grace for himself‘, ‘oft — often‘,

‘anhaga — loner‘ and ‘are — grace‘ alliterate and there is a short pause between

‘anhaga‘ and ‘are‘.

Oft

him

anhaga

are

gebideð

As can be seen above, alliteration is based on sound, not letter.

Vowels and diphthongs alliterate with each other. So stressed syllables

beginning in ‘o‘, like ‘oft‘ can alliterate with stressed syllables beginning

with any other vowel, like ‘anhaga‘.

However consonant clusters alliterate only with

themselves.

For example, ‘sp-‘, ‘st-‘

or ‘sc-‘ alliterate only

with another syllable beginning with ‘sp-‘, ‘st-‘

or ‘sc-‘. They do not alliterate with each other or other words beginning with

‘s-‘.

Stodon

stædefæste

stihte

hie

Byrhtnoð

Because alliteration and meter are integral to surviving Old English verse, it can explain some

awkward or strange sentences you run across. However, there are some other features you should be aware

of.

Kennings and Appositives

Kennings are compound words which use more figurative language in place of nouns. For

example, referring to blood as

‘heaþoswata —

battle sweat‘

or referring to the sky as ‘heofones hwealf — heaven’s vault‘. By substituting nouns with more

figurative language, poets increased the number of words that could be used to alliterate.

Also, the fact they are compound words lends itself to the rhythms of Old English meter.

Appositives are nouns or noun phrases that follow or come before a noun, and specify

who or what

something is. For example, ‘Him se yldesta andswarode,

werodes wisa, word-hord onleac — To him the senior one answered, leader of the troop,

unlocked his word-hoard‘. The phrases ‘the senior one’ and ‘leader of the troop’ both refer to

the same subject — in this case Beowulf — even though they

are separated by the verb. This kind of variation is a common feature of oral poetry but can

read awkwardly to a modern English reader. You can find an example of kennings and appositives in the

below excerpt from Beowulf: ‘Hæfde se goda Geata leoda

cempan gecorone þara þe he cenoste

findan mihte fiftyna sum

sundwudu sohte secg wisade

lagucræftig mon landgemyrcu —

The worthy one had, from the Geatish peoples, chosen champions, those who were the boldest he could

find;

fifteen together, they sought the sea-wood, he led the warriors, that sea-skilled man, to the

boundary of the shore‘.

Hæfde se goda Geata leoda

cempan gecorone þara þe he cenoste

findan mihte fiftyna sum

sundwudu sohte secg wisade

lagucræftig mon landgemyrcu

While the other rules of word order still generally apply to poetry, word order is often more fluid

in order to conform to the stylistic features found in surviving Old English

verse, so it is important to be aware of them.

Return to Prose Style

Continue to Syntax

Overview

Poetry has licence to manipulate ‘reality’ (for example in metaphor or allegory) and also to distort language into artificial and deliberate patterns which you would be much less likely to find in everyday speech. This is the origin of the idea of ‘poetic licence’. One of poetry’s licences is its licence to vary the expected or conventional order of words in a sentence, without these unusual orders being considered ‘wrong’ or ‘ungrammatical’.

Gregory Roscow (in his great book, Syntax and Style in Chaucer’s Poetry, to which this post is greatly indebted, and which you should all read) quotes from Geoffrey of Vinsauf’s early thirteenth-century Poetria Nova, a guide for poets writing Latin verse: ‘Juxtaposition of related words coveys the sense more readily, but their moderate separation sounds better to the ear and has greater elegance.’ It is easier to understand words when they are close together in a conventional order, but it can be more eloquent and musical to separate elements of a sentence.

Geoffrey’s advice was for poets composing in Latin, but poets also used inverted word orders in English (especially if they were seeking to write in an elevated style). Roscow’s book shows which sorts of manipulations of word order are found in English poetry before Chaucer, and which ones may well be Chaucer’s own innovation. These manipulations can make lines difficult to parse and understand. In Book I of Troilus, the narrating voice describes how the God of Love does not spare Troilus from the pain of unrequited love:

In him ne deyned sparen blood royal

The fyr of love, (i.e. ‘the fire of love didn’t

deign to spare his royal blood’, when

translated in ‘normal’ word order)

The subject of the sentence (the fyr of love) is postponed until after the verb and the object. Chaucer does this partly to meet the demands of rhyme, metre and line-length, and partly as a principle of style. Inverted word orders such as this make Chaucer’s poetry seem noticeably different from everyday language, more complex, elaborate, poetic. It’s a useful thing to be able to spot for commentary or close-reading. Be careful to consider, though, whether the words have been inverted for grammatical reasons (for example questions or imperatives).

One of the types of word order Roscow discusses is front-shifting (the moving of a sentence or clause component to the front of a sentence or clause, when we would normally expect it later on). Here’s the description of Troilus on his horse outside Criseyde’s window for the first time in Book II:

This Troilus sat on his baye stede,

Al armed, save his heed, ful richely,

And wounded was his hors, and gan to blede,

You can see that the third line reads wounded was his hors not his hors was wounded. Chaucer probably does this here because of the demands of metre, but nonetheless this potentially produces some very useful ‘by-products’ for us to interpret. The front-loading of wounded emphasises both that word and the switch of focus from armour to injury. It also makes us wait for just a fraction to find out who or what is wounded. Is it somehow a disappointment to find out that it is Troilus’s horse, rather than Troilus himself, who is wounded?

Roscow also discusses syntactical discontinuity (that is, the separating of words and phrases which would usually be found close together in sentences). Here’s the narrating voice’s continuation of the events leading up to Troilus’s death in Book V:

The wrathe, as I began yow for to seye,

Of Troilus, the Grekes boughten dere;

For thousandes his hondes maden deye,

(i.e. ‘as I began to tell you, the Greeks paid

dearly for the wrath of Troilus, because his

hands made thousands die’, when

translated in ‘normal’ word order)

At this significant moment at the end of his poem, Chaucer makes use of much discontinuity, even splitting the noun phrase the wrathe of Troilus, as well as front-shifting wrathe and thousandes for emphasis. All this allows Chaucer to create his passage of high style, even though the vocabulary is relatively familiar.

Further Reading:

G H Roscow, Syntax and Style in Chaucer’s Poetry (D S Brewer, 1970)