Worksheets

Powerpoints

Video Lessons

Search

Filters

SELECTED FILTERS

Clear all filters

- English ESL Video Lessons

- Grammar Topics

- Word order

SORT BY

Most popular

TIME PERIOD

All-time

DianeGerritse

32899 uses

Kisdobos

17339 uses

kassandra

7659 uses

carina.plettenbacher

7296 uses

Alina_the_teacher

6687 uses

Kisdobos

4217 uses

katarinasubova

3381 uses

Monokini1

2790 uses

jtaylor929

2284 uses

Dankaness

1865 uses

Virgoletta

1822 uses

BOtani4ka

1798 uses

Next

17

Blog

FAQ

About us

Terms of use

Your Copyright

Можно ли использовать вопросительный порядок слов в утвердительных предложениях? Как построить предложение, если в нем нет подлежащего? Об этих и других нюансах читайте в нашей статье.

Прямой порядок слов в английских предложениях

Утвердительные предложения

В английском языке основной порядок слов можно описать формулой SVO: subject – verb – object (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение).

Mary reads many books. — Мэри читает много книг.

Подлежащее — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит в начале предложения (кто? — Mary).

Сказуемое — это глагол, который стоит после подлежащего (что делает? — reads).

Дополнение — это существительное или местоимение, которое стоит после глагола (что? — books).

В английском отсутствуют падежи, поэтому необходимо строго соблюдать основной порядок слов, так как часто это единственное, что указывает на связь между словами.

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| My mum | loves | soap operas. | Моя мама любит мыльные оперы. |

| Sally | found | her keys. | Салли нашла свои ключи. |

| I | remember | you. | Я помню тебя. |

Глагол to be в утвердительных предложениях

Как правило, английское предложение не обходится без сказуемого, выраженного глаголом. Так как в русском можно построить предложение без глагола, мы часто забываем о нем в английском. Например:

Mary is a teacher. — Мэри — учительница. (Мэри является учительницей.)

I’m scared. — Мне страшно. (Я являюсь напуганной.)

Life is unfair. — Жизнь несправедлива. (Жизнь является несправедливой.)

My younger brother is ten years old. — Моему младшему брату десять лет. (Моему младшему брату есть десять лет.)

His friends are from Spain. — Его друзья из Испании. (Его друзья происходят из Испании.)

The vase is on the table. — Ваза на столе. (Ваза находится/стоит на столе.)

Подведем итог, глагол to be в переводе на русский может означать:

- быть/есть/являться;

- находиться / пребывать (в каком-то месте или состоянии);

- существовать;

- происходить (из какой-то местности).

Если вы не уверены, нужен ли to be в вашем предложении в настоящем времени, то переведите предложение в прошедшее время: я на работе — я была на работе. Если в прошедшем времени появляется глагол-связка, то и в настоящем он необходим.

Предложения с there is / there are

Когда мы хотим сказать, что что-то где-то есть или чего-то где-то нет, то нам нужно придерживаться конструкции there + to be в начале предложения.

There is grass in the yard, there is wood on the grass. — На дворе — трава, на траве — дрова.

Если в таких типах предложений мы не используем конструкцию there is / there are, то по-английски подобные предложения будут звучать менее естественно:

There are a lot of people in the room. — В комнате много людей. (естественно)

A lot of people are in the room. — Много людей находится в комнате. (менее естественно)

Обратите внимание, предложения с there is / there are, как правило, переводятся на русский с конца предложения.

Еще конструкция there is / there are нужна, чтобы соблюсти основной порядок слов — SVO (подлежащее – сказуемое – дополнение):

| Подлежащее | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|

| There | is | too much sugar in my tea. | В моем чае слишком много сахара. |

Более подробно о конструкции there is / there are можно прочитать в статье «Грамматика английского языка для начинающих, часть 3».

Местоимение it

Мы, как носители русского языка, в английских предложениях забываем не только про сказуемое, но и про подлежащее. Особенно сложно понять, как перевести на английский подобные предложения: Темнеет. Пора вставать. Приятно было пообщаться. В английском языке во всех этих предложениях должно стоять подлежащее, роль которого будет играть вводное местоимение it. Особенно важно его не забыть, если мы говорим о погоде.

It’s getting dark. — Темнеет.

It’s time to get up. — Пора вставать.

It was nice to talk to you. — Приятно было пообщаться.

Хотите научиться грамотно говорить по-английски? Тогда записывайтесь на курс практической грамматики.

Отрицательные предложения

Если предложение отрицательное, то мы ставим отрицательную частицу not после:

- вспомогательного глагола (auxiliary verb);

- модального глагола (modal verb).

| Подлежащее | Вспомогательный/Модальный глагол | Частица not | Сказуемое | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sally | has | not | found | her keys. | Салли не нашла свои ключи. |

| My mum | does | not | love | soap operas. | Моя мама не любит мыльные оперы. |

| He | could | not | save | his reputation. | Он не мог спасти свою репутацию |

| I | will | not | be | yours. | Я не буду твоей. |

Если в предложении единственный глагол — to be, то ставим not после него.

| Подлежащее | Глагол to be | Частица not | Дополнение | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter | is | not | an engineer. | Питер не инженер. |

| I | was | not | at work yesterday. | Я не была вчера на работе. |

| Her friends | were | not | polite enough. | Ее друзья были недостаточно вежливы. |

Порядок слов в вопросах

Для начала скажем, что вопросы бывают двух основных типов:

- закрытые вопросы (вопросы с ответом «да/нет»);

- открытые вопросы (вопросы, на которые можно дать развернутый ответ).

Закрытые вопросы

Чтобы построить вопрос «да/нет», нужно поставить модальный или вспомогательный глагол в начало предложения. Получится следующая структура: вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое. Следующие примеры вам помогут понять, как утвердительное предложение преобразовать в вопросительное.

She goes to the gym on Mondays. — Она ходит в зал по понедельникам.

Does she go to the gym on Mondays? — Ходит ли она в зал по понедельникам?

He can speak English fluently. — Он умеет бегло говорить по-английски.

Can he speak English fluently? — Умеет ли он бегло говорить по-английски?

Simon has always loved Katy. — Саймон всегда любил Кэти.

Has Simon always loved Katy? — Всегда ли Саймон любил Кэти?

Обратите внимание! Если в предложении есть только глагол to be, то в Present Simple и Past Simple мы перенесем его в начало предложения.

She was at home all day yesterday. — Она была дома весь день.

Was she at home all day yesterday? — Она была дома весь день?

They’re tired. — Они устали.

Are they tired? — Они устали?

Открытые вопросы

В вопросах открытого типа порядок слов такой же, только в начало предложения необходимо добавить вопросительное слово. Тогда структура предложения будет следующая: вопросительное слово – вспомогательный/модальный глагол – подлежащее – сказуемое.

Перечислим вопросительные слова: what (что?, какой?), who (кто?), where (где?, куда?), why (почему?, зачем?), how (как?), when (когда?), which (который?), whose (чей?), whom (кого?, кому?).

He was at work on Monday. — В понедельник он весь день был на работе.

Where was he on Monday? — Где он был в понедельник?

She went to the cinema yesterday. — Она вчера ходила в кино.

Where did she go yesterday? — Куда она вчера ходила?

My father watches Netflix every day. — Мой отец каждый день смотрит Netflix.

How often does your father watch Netflix? — Как часто твой отец смотрит Netflix?

Вопросы к подлежащему

В английском есть такой тип вопросов, как вопросы к подлежащему. У них порядок слов такой же, как и в утвердительных предложениях, только в начале будет стоять вопросительное слово вместо подлежащего. Сравните:

Who do you love? — Кого ты любишь? (подлежащее you)

Who loves you? — Кто тебя любит? (подлежащее who)

Whose phone did she find two days ago? — Чей телефон она вчера нашла? (подлежащее she)

Whose phone is ringing? — Чей телефон звонит? (подлежащее whose phone)

What have you done? — Что ты наделал? (подлежащее you)

What happened? — Что случилось? (подлежащее what)

Обратите внимание! После вопросительных слов who и what необходимо использовать глагол в единственном числе.

Who lives in this mansion? — Кто живет в этом особняке?

What makes us human? — Что делает нас людьми?

Косвенные вопросы

Если вам нужно что-то узнать и вы хотите звучать более вежливо, то можете начать свой вопрос с таких фраз, как: Could you tell me… ? (Можете подсказать… ?), Can you please help… ? (Можете помочь… ?) Далее задавайте вопрос, но используйте прямой порядок слов.

Could you tell me where is the post office is? — Не могли бы вы мне подсказать, где находится почта?

Do you know what time does the store opens? — Вы знаете, во сколько открывается магазин?

Если в косвенный вопрос мы трансформируем вопрос типа «да/нет», то перед вопросительной частью нам понадобится частица «ли» — if или whether.

Do you like action films? — Тебе нравятся боевики?

I wonder if/whether you like action films. — Мне интересно узнать, нравятся ли тебе экшн-фильмы.

Другие члены предложения

Прилагательное в английском стоит перед существительным, а наречие обычно — в конце предложения.

Grace Kelly was a beautiful woman. — Грейс Келли была красивой женщиной.

Andy reads well. — Энди хорошо читает.

Обстоятельство, как правило, стоит в конце предложения. Оно отвечает на вопросы как?, где?, куда?, почему?, когда?

There was no rain last summer. — Прошлым летом не было дождя.

The town hall is in the city center. — Администрация находится в центре города.

Если в предложении несколько обстоятельств, то их надо ставить в следующем порядке:

| Подлежащее + сказуемое | Обстоятельство (как?) | Обстоятельство (где?) | Обстоятельство (когда?) | Перевод |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fergie didn’t perform | very well | at the concert | two years ago. | Ферги не очень хорошо выступила на концерте два года назад. |

Чтобы подчеркнуть, когда или где что-то случилось, мы можем поставить обстоятельство места или времени в начало предложения:

Last Christmas I gave you my heart. But the very next day you gave it away. This year, to save me from tears, I’ll give it to someone special. — Прошлым Рождеством я подарил тебе свое сердце. Но уже на следующий день ты отдала его обратно. В этом году, чтобы больше не горевать, я подарю его кому-нибудь другому.

Если вы хотите преодолеть языковой барьер и начать свободно общаться с иностранцами, записывайтесь на разговорный курс английского.

Надеемся, эта статья была вам полезной и вы разобрались, как строить предложения в английском языке. Предлагаем пройти небольшой тест для закрепления темы.

Тест по теме «Порядок слов в английском предложении, часть 1»

© 2023 englex.ru, копирование материалов возможно только при указании прямой активной ссылки на первоисточник.

Correct word order has a significant role in teaching a foreign language. Many learners automatically order the words in a sentence as in their native language. However, since different languages have various sentence structures, ESL teachers should be very attentive in dealing with this topic. Despite its difficulty, it can be taught in fun and entertaining ways to primary school children. Here we present activities that will definitely come in handy to practise word order with your kids.

Rainbow sentences

One of the fascinating ways of practising word order with kids is definitely with Rainbow order. Distribute the mixed parts of the sentence to your students and ask them to put the words in the correct order according to rainbow colours (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). To make it more fun, you can also play the rainbow song. Children really enjoy doing this activity.

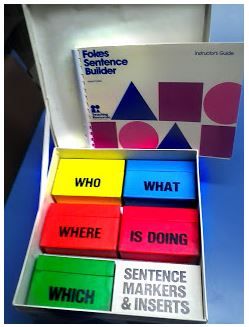

Question cards

Use question cards to introduce the rules of word order to your students, such as Who/what, what happens, where, when, etc. Provide with an example (Bob goes to school every day.) and get your students to put the mixed words in the correct order.

Expanding the phrase

Write a word on the board. Ask your students to take in turns and add extra words to make it into a longer and longer sentence. It must be a logically coherent sentence. Students cannot remove words, but they can change the order while adding new words. My kids really enjoy this activity, especially when I ask them to use their imagination and expand the phrase in a funny way.

Cat

- A black cat

- A big black cat

- Tom saw a big black cat

- Tom saw a big black cat in the forest

- Tom saw a big black cat in the forest last night

Removing words from a sentence

This activity is considered to be the opposite of the previous one. Here you provide your students with a long sentence and ask them to take turns and to remove words so that it always remains a sentence.

- Kate doesn’t like cartoons because they are loud, so she doesn’t watch them.

- Kate doesn’t like cartoons because they are loud, so she doesn’t watch.

- Kate doesn’t like cartoons because they are loud.

- Kate doesn’t like cartoons.

Brainstorming sentences

Ask your students to work in pairs or in groups. Choose a topic that the students are familiar with (weather, animals, food, jobs, etc) and get them to make up as many correct and long sentences as possible.

Example: Animals

Group A: Crocodiles are very dangerous animals.

Group B: Many people are afraid of spiders and not mice.

Group A: It is very difficult to survive crocodile’s attack because they attack very quickly.

Group B: Last summer, when we were staying in a forest, we suddenly saw a wolf near our tents.

Gringle

This is a guessing game. Choose a player, who will think of a verb his/her classmates must guess what verb this student is thinking of. The verb is replaced by a nonsense word such as “gringle”. The students then ask questions, like this:

— Can you gringle at night?

— Who gringles more — girls or boys

— Do you use a special object to gringle?

— When do you usually gringle?

— Is gringling a fun or a serious action?

Why do people gringle?This game is a magnificent tool for practising word order in interrogative sentences with your kids. With the help of numerous questions, they revise different types of questions, such as General and Special ones.

This was the list of the activities that I usually use with my kids to practise word order. I am sure you are aware of some other fascinating ways as well. Share them in the comments below.

3.2.1 Word order in a sentence in English is fairly strict compared to other languages. We often use SVOPT word order in a sentence:

This is the order in which English native speakers want to get their information. We generally want to know:

3.2.2 It is possible to put the time phrase first in the sentence, if you want to emphasise that piece of information:

However, it is better to start with the subject so that we establish WHO is doing the action first. We also get time information from the verb tense. For example, by using the past tense verb ‘ate’ we understand immediately that the action happened in finished time, in the past. This time information is sufficient until we get final confirmation of the exact time at the end of the sentence: ‘last night’.

3.2.3 However, changing the word order in other ways is not permitted in English. For example, the following sentences would be incorrect:

They just sound like jumbled up sentences, rather than English. It may be that the person listening can work out what you are saying because all the keywords are present and they are able to ‘unjumble’ them in their mind as you speak, but it makes a lot of extra work for your listener, who is rather expecting to hear the information presented in SVOPT order.

3.2.4 Not every verb has an object, so sometimes this part of SVOPT will be blank. They are called intransitive verbs. For example:

The verb ‘go’ does not have an object. It is intransitive, so the O part of SVOPT is blank.

3.2.5 Similarly, we do not need to include every part of SVOPT word order in every sentence. It is the order that is important and should be followed:

3.2.6 We can easily turn a SVOPT sentence into a compound sentence but using a conjunction such as:

Jenny ate a sandwich in the kitchen last night…

Exercises

Ex. 3.2.1 Writing Write 10 sentences with SVOPT word order. You don’t need to include an object each time:

Ex. 3.2.2 Writing Complete the worksheets: make-a-sentence-with-svopt-word-order-1-4.

Ex. 3.2.3 Writing Complete the worksheets: sentence-building-with-svopt-word-order-1-2.

Ex. 3.2.4 Writing Complete the worksheet: practice-with-svopt-r-word-order.

WORD ORDER IN AFFIRMATIVE SENTENCES.

The most common order of words in sentences is as follows:

Subject /S/ +Predicate /P/ +Object /Ob/

Sally speaks English.

In English the place /P/ is usually mentioned before the time/T/. E.g. I go to the supermarket every Saturday.

Advers of frequency such as always, never, sometimes, often, etc generally go before the verb. E.g Susan often goes to do shopping.

However, with the verb to be they go after the verb. E.g. She is often late.

If there is an indirect object /In Ob/ in the sentences the word order is as follows.

|

S |

P |

In Ob |

Ob |

P |

T |

|

I |

will tell |

you |

the story |

at school |

tomorrow. |

WORD ORDER IN INTERROGATIVE SENTENCES.

The word order in interrogative sentences is:

|

Question word |

Auxiliary verb |

Subject |

Predicate |

Object |

Place |

Time |

|

What |

are |

you |

telling |

me |

at school |

tomorrow? |

WORD ORDER IN NEGATIVE SENTENCES.

The word order in negative sentences is the same as in affirmative sentences. In negative sentences we usually need an auxiliary verb.

|

S |

P |

In Ob |

Ob |

P |

T |

|

I |

will not tell |

you |

the story |

at school |

tomorrow. |

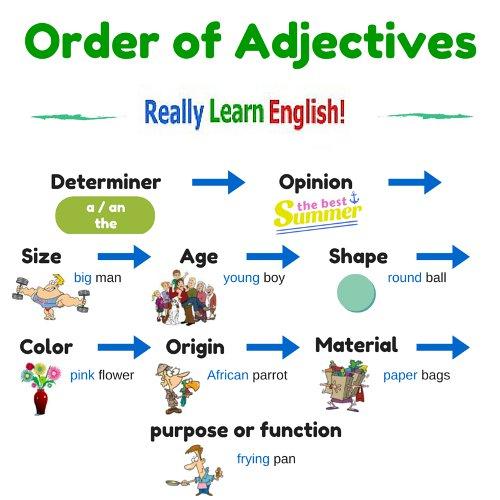

ADJECTIVE WORD ORDER

The general order of adjectives before a noun is the following:

|

Opinion |

Size |

Age |

Shape |

Color |

Origin |

Material |

Purpose |

Noun |

|

Ugly |

small |

old |

thin |

red |

Italian |

cotton |

sleeping |

bag |

Welcome to the ELB Guide to English Word Order and Sentence Structure. This article provides a complete introduction to sentence structure, parts of speech and different sentence types, adapted from the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences. I’ve prepared this in conjunction with a short 3-video course, currently in editing, to help share the lessons of the book to a wider audience.

You can use the headings below to quickly navigate the topics:

- Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

- Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

- Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

- Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

- Parts of Speech

- Nouns, Determiners and Adjectives

- Pronouns

- Verbs

- Phrasal Verbs

- Adverbs

- Prepositions

- Conjunctions

- Interjections

- Clauses, Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

Different Ways to Analyse English Structure

There are lots of ways to break down sentences, for different purposes. This article covers the systems I’ve found help my students understand and form accurate sentences, but note these are not the only ways to explore English grammar.

I take three approaches to introducing English grammar:

- Studying overall patterns, grouping sentence components by their broad function (subject, verb, object, etc.)

- Studying different word types (the parts of speech), how their phrases are formed and their places in sentences

- Studying groupings of phrases and clauses, and how they connect in simple, compound and complex sentences

Subject-Verb-Object: Sentence Patterns

English belongs to a group of just under half the world’s languages which follows a SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT order. This is the starting point for all our basic clauses (groups of words that form a complete grammatical idea). A standard declarative clause should include, in this order:

- Subject – who or what is doing the action (or has a condition demonstrated, for state verbs), e.g. a man, the church, two beagles

- Verb – what is done or what condition is discussed, e.g. to do, to talk, to be, to feel

- Additional information – everything else!

In the correct order, a subject and verb can communicate ideas with immediate sense with as little as two or three words.

- Gemma studies.

- It is hot.

Why does this order matter? We know what the grammatical units are because of their position in the sentence. We give words their position based on the function we want them to convey. If we change the order, we change the functioning of the sentence.

- Studies Gemma

- Hot is it

With the verb first, these ideas don’t make immediate sense and, depending on the verbs, may suggest to English speakers a subject is missing or a question is being formed with missing components.

- The alien studies Gemma. (uh oh!)

- Hot, is it? (a tag question)

If we don’t take those extra steps to complete the idea, though, the reversed order doesn’t work. With “studies Gemma”, we couldn’t easily say if we’re missing a subject, if studies is a verb or noun, or if it’s merely the wrong order.

The point being: using expected patterns immediately communicates what we want to say, without confusion.

Adding Additional Information: Objects, Prepositional Phrases and Time

Understanding this basic pattern is useful for when we start breaking down more complicated sentences; you might have longer phrases in place of the subject or verb, but they should still use this order.

| Subject | Verb |

| Gemma | studies. |

| A group of happy people | have been quickly walking. |

After subjects and verbs, we can follow with different information. The other key components of sentence patterns are:

- Direct Object: directly affected by the verb (comes after verb)

- Indirect Objects: indirectly affected by the verb (typically comes between the verb and a direct object)

- Prepositional phrases: noun phrases providing extra information connected by prepositions, usually following any objects

- Time: describing when, usually coming last

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Gemma | studied | English | in the library | last week. | |

| Harold | gave | his friend | a new book | for her birthday | yesterday. |

The individual grammatical components can get more complicated, but that basic pattern stays the same.

| Subject | Verb | Indirect Object | Direct Object | Preposition Phrase | Time |

| Our favourite student Gemma | has been studying | the structure of English | in the massive new library | for what feels like eons. | |

| Harold the butcher’s son | will have given | the daughter of the clockmaker | an expensive new book | for her coming-of-age festival | by this time next week. |

The phrases making up each grammatical unit follow their own, more specific rules for ordering words (covered below), but overall continue to fit into this same basic order of components:

Subject – Verb – Indirect Object – Direct Object – Prepositional Phrase – Time

Alternative Sentence Patterns: Different Sentence Types

Subject-Verb-Object is a starting point that covers positive, declarative sentences. These are the most common clauses in English, used to describe factual events/conditions. The type of verb can also make a difference to these patterns, as we have action/doing verbs (for activities/events) and linking/being verbs (for conditions/states/feelings).

Here’s the basic patterns we’ve already looked at:

- Subject + Action Verb – Gemma studies.

- Subject + Action Verb + Object – Gemma studies English.

- Subject + Action Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object – Gemma gave Paul a book.

We might also complete a sentence with an adverb, instead of an object:

- Subject + Action Verb + Adverb – Gemma studies hard.

When we use linking verbs for states, senses, conditions, and other occurrences, the verb is followed by noun or adjective phrases which define the subject.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Noun Phrase – Gemma is a student.

- Subject + Linking Verb + Adjective Phrase – Gemma is very wise.

These patterns all form positive, declarative sentences. Another pattern to note is Questions, or interrogative sentences, where the first verb comes before the subject. This is done by adding an auxiliary verb (do/did) for the past simple and present simple, or moving the auxiliary verb forward if we already have one (to be for continuous tense, or to have for perfect tenses, or the modal verbs):

- Gemma studies English. –> Does Gemma study English?

- Gemma is very wise. –> Is Gemma very wise?

For more information on questions, see the section on verbs.

Finally, we can also form imperative sentences, when giving commands, which do not need a subject.

- Study English!

(Note it is also possible to form exclamatory sentences, which express heightened emotion, but these depend more on context and punctuation than grammatical components.)

Parts of Speech

General patterns offer overall structures for English sentences, while the broad grammatical units are formed of individual words and phrases. In English, we define different word types as parts of speech. Exactly how many we have depends on how people break them down. Here, we’ll look at nine, each of which is explained below. Either keep reading or click on the word types to go to the sections about their word order rules.

- Nouns – naming words that define someone or something, e.g. car, woman, cat

- Pronouns – words we use in place of nouns, e.g. he, she, it

- Verbs – doing or being words, describing an action, state or experience e.g. run, talk, be

- Adjectives – words that describe nouns or pronouns, e.g. cheerful, smelly, loud

- Adverbs – words that describe verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, sentences themselves – anything other nouns and pronouns, basically, e.g. quickly, curiously, weirdly

- Determiners – words that tell us about a noun’s quantity or if it’s specific, e.g. a, the, many

- Prepositions – words that show noun or noun phrase positions and relationships, e.g. above, behind, in, on

- Conjunctions – words that connect words, phrases or clauses e.g. and, but

- Interjections – words that express a single emotion, e.g. Hey! Ah! Oof!

For more articles and exercises on all of these, be sure to also check out ELB’s archive covering parts of speech.

Noun Phrases, Determiners and Adjectives

Subjects and objects are likely to be nouns or noun phrases, describing things. So sentences usually to start with a noun phrase followed by a verb.

- Nina ate.

However, a noun phrase may be formed of more than word.

We define nouns with determiners. These always come first in a noun phrase. They can be articles (a/an/the – telling us if the noun is specific or not), or can refer to quantities (e.g. some, much, many):

- a dog (one of many)

- the dog in the park

- many dogs

After determiners, we use adjectives to add description to the noun:

- The fluffy dog.

You can have multiple adjectives in a phrase, with orders of their own. You can check out my other article for a full analysis of adjective word order, considering type, material, size and other qualities – but a starting rule is that less definite adjectives go first – more specific qualities go last. Lead with things that are more opinion-based, finish with factual elements:

- It is a beautiful wooden chair. (opinion before fact.)

We can also form compound nouns, where more than one noun is used, e.g. “cat food”, “exam paper”. The earlier nouns describe the final noun: “cat food” is a type of food, for cats; an “exam paper” is a specific paper. With compound nouns you have a core noun (the last noun), what the thing is, and any nouns before it describe what type. So – description first, the actual thing last.

Finally, noun phrases may also include conjunctions joining lists of adjectives or nouns. These usually come between the last two items in a list, either between two nouns or noun phrases, or between the last two adjectives in a list:

- Julia and Lenny laughed all day.

- a long, quick and dangerous snake

Pronouns

We use pronouns in the place of nouns or noun phrases. For the most part, these fit into sentences the same way as nouns, in subject or object positions, but don’t form phrases, as they replace a whole noun phrase – so don’t use describing words or determiners with pronouns.

Pronouns suggest we already know what is being discussed. Their positions are the same as nouns, except with phrasal verbs, where pronouns often have fixed positions, between a verb and a particle (see below).

Verbs

Verb phrases should directly follow the subject, so in terms of parts of speech a verb should follow a noun phrase, without connecting words.

As with nouns and noun phrases, multiple words may make up the verb component. Verb phrases depend on your tenses, which follow particular forms – e.g. simple, continuous, perfect and perfect continuous. The specifics of verb phrases are covered elsewhere, for example the full verb forms for the tenses are available in The English Tenses Practical Grammar Guide. But in terms of structure, with standard, declarative clauses the ordering of verb phrases should not change from their typical tense forms. Other parts of speech do not interrupt verb phrases, except for adverbs.

The times that verb phrases do change their structure are for Questions and Negatives.

With Yes/No Questions, the first verb of a verb phrase comes before the subject.

- Neil is running. –> Is Neil running?

This requires an auxiliary verb – a verb that creates a grammatical function. Many tenses already have an auxiliary verb – to be in continuous tenses (“is running”), or to have in perfect tenses (have done). For these, to make a question we move that auxiliary in front of the subject. With the past and present simple tenses, for questions, we add do or did, and put that before the subject.

- Neil ran. –> Did Neil run?

We can also have questions that use question words, asking for information (who, what, when, where, why, which, how), which can include noun phrases. For these, the question word and any noun phrases it includes comes before the verb.

- Where did Neil Run?

- At what time of day did Neil Run?

To form negative statements, we add not after the first verb, if there is already an auxiliary, or if there is not auxiliary we add do not or did not first.

- Neil is running. –> Neil is not

- Neil ran. Neil did not

The not stays behind the subject with negative questions, unless we use contractions, where not is combined with the verb and shares its position.

- Is Neil not running?

- Did Neil not run?

- Didn’t Neil run?

Phrasal Verbs

Phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs, often with very specific meanings. They include at least a verb and a particle, which usually looks like a preposition but functions as part of the verb, e.g. “turn up“, “keep on“, “pass up“.

You can keep phrasal verb phrases all together, as with other verb phrases, but they are more flexible, as you can also move the particle after an object.

- Turn up the radio. / Turn the radio up.

This doesn’t affect the meaning, and there’s no real right or wrong here – except with pronouns. When using pronouns, the particle mostly comes after the object:

- Turn it up. NOT Turn up it.

For more on phrasal verbs, check out the ELB phrasal verbs master list.

Adverbs

Adverbs and adverbial phrases are really tricky in English word order because they can describe anything other than nouns. Their positions can be flexible and they appear in unexpected places. You might find them in the middle of verb phrases – or almost anywhere else in a sentence.

There are many different types of adverbs, with different purposes, which are usually broken down into degree, manner, frequency, place and time (and sometimes a few others). They may be single words or phrases. Adverbs and adverb phrases can be found either at the start of a clause, the end of a clause, or in a middle position, either directly before or after the word they modify.

- Graciously, Claire accepted the award for best student. (beginning position)

- Claire graciously accepted the award for best student. (middle position)

- Claire accepted the award for best student graciously. (end position)

Not all adverbs can go in all positions. This depends on which type they are, or specific adverb rules. One general tip, however, is that time, as with the general sentence patterns, should usually come last in a clause, or at the very front if moved for emphasis.

With verb phrases, adverbs often either follow the whole phrase or come before or after the first verb in a phrase (there are regional variations here).

For multiple adverbs, there can be a hierarchy in a similar way to adjectives, but you shouldn’t often use many adverbs together.

The largest section of the Word Order book discusses adverbs, with exercises.

Prepositions

Prepositions are words that, generally, demonstrate relationships between noun phrases (e.g. by, on, above). They mostly come before a noun phrase, hence the name pre-position, and tend to stick with the noun phrase they describe, so move with the phrase.

- They found him [in the cupboard].

- [In the cupboard,] they found him.

In standard sentence structure, prepositional phrases often follow verbs or other noun phrases, but they may also be used for defining information within a noun phrases itself:

- [The dog in sunglasses] is drinking water.

Conjunctions

Conjunctions connect lists in noun phrases (see nouns) or connect clauses, meaning they are found between complete clauses. They can also come at the start of a sentence that begins with a subordinate clause, when clauses are rearranged (see below), but that’s beyond the standard word order we’re discussing here. There’s more information about this in the article on different sentence types.

As conjunctions connect clauses, they come outside our sentence and word type patterns – if we have two clauses following subject-verb-object, the conjunction comes between them:

|

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

Conjunction |

Subject |

Verb |

Object |

|

He |

washed |

the car |

while |

she |

ate |

a pie. |

Interjections

These are words used to show an emotion, usually something surprising or alarming, often as an interruption – so they can come anywhere! They don’t normally connect to other words, as they are either used to get attention or to cut off another thought.

- Hey! Do you want to go swimming?

- OH NO! I forgot my homework.

Clauses and Simple, Compound and Complex Sentences

While a phrase is any group of words that forms a single grammatical unit, a clause is when a group of words form a complete grammatical idea. This is possible when we follow the patterns at the start of this article, for example when we combine a subject and verb (or noun phrase and verb phrase).

A single clause can follow any of the patterns we’ve already discussed, using varieties of the word types covered; it can be as simple a two-word subject-verb combo, or it may include as many elements as you can think of:

- Eric sat.

- The boy spilt blue paint on Harriet in the classroom this morning.

As long as we have one main verb and one main subject, these are still single clauses. Complete with punctuation, such as a capital letter and full stop, and we have a complete sentence, a simple sentence. When we combine two or more clauses, we form compound or complex sentences, depending on the clauses relationships to each other. Each type is discussed below.

Simple Sentences

A sentence with one independent clause is what we call a simple sentence; it presents a single grammatically complete action, event or idea. But as we’ve seen, just because the sentence structure is called simple it does not mean the tenses, subjects or additional information are simple. It’s the presence of one main verb (or verb phrase) that keeps it simple.

Our additional information can include any number of objects, prepositional phrases and adverbials; and that subject and verb can be made up of long noun and verb phrases.

Compound Sentences

We use conjunctions to bring two or more clauses together to create a compound sentence. The clauses use the same basic order rules; just treat the conjunction as a new starting point. So after one block of subject-verb-object, we have a conjunction, then the next clause will use the same pattern, subject-verb-object.

- [Gemma worked hard] and [Paul copied her].

See conjunctions for another example.

A series of independent clauses can be put together this way, following the expected patterns, joined by conjunctions.

Compound sentences use co-ordinating conjunctions, such as and, but, for, yet, so, nor, and or, and do not connect the clauses in a dependent way. That means each clause makes sense on its own – if we removed the conjunction and created separate sentences, the overall meaning would remain the same.

With more than two clauses, you do not have to include conjunctions between each one, e.g. in a sequence of events:

- I walked into town, I visited the book shop and I bought a new textbook.

And when you have the same subject in multiple clauses, you don’t necessarily need to repeat it. This is worth noting, because you might see clauses with no immediate subject:

- [I walked into town], [visited the book shop] and [bought a new textbook].

Here, with “visited the book shop” and “bought a new textbook” we understand that the same subject applies, “I”. Similarly, when verb tenses are repeated, using the same auxiliary verb, you don’t have to repeat the auxiliary for every clause.

What about ordering the clauses? Independent clauses in compound sentences are often ordered according to time, when showing a listed sequence of actions (as in the example above), or they may be ordered to show cause and effect. When the timing is not important and we’re not showing cause and effect, the clauses of compound sentences can be moved around the conjunction flexibly. (Note: any shared elements such as the subject or auxiliary stay at the front.)

- Billy [owned a motorbike] and [liked to cook pasta].

- Billy [liked to cook pasta] and [owned a motorbike].

Complex Sentences

As well as independent clauses, we can have dependent clauses, which do not make complete sense on their own, and should be connected to an independent clause. While independent clauses can be formed of two words, the subject and verb, dependent clauses have an extra word that makes them incomplete – either a subordinating conjunction (e.g. because, when, since, if, after and although), or a relative pronoun, (e.g. that, who and which).

- Jim slept.

- While Jim slept,

Subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns create, respectively, a subordinate clause or a relative clause, and both indicate the clause is dependent on more information to form a complete grammatical idea, to be provided by an independent clause:

- While Jim slept, the clowns surrounded his house.

In terms of structure, the order of dependent clauses doesn’t change from the patterns discussed before – the word that comes at the front makes all the difference. We typically connect independent clauses and dependent clauses in a similar way to compound sentences, with one full clause following another, though we can reverse the order for emphasis, or to present a more logical order.

- Although she liked the movie, she was frustrated by the journey home.

(Note: when a dependent clause is placed at the beginning of a sentence, we use a comma, instead of another conjunction, to connect it to the next clause.)

Relative clauses, those using relative pronouns (such as who, that or which), can also come in different positions, as they often add defining information to a noun or take the place of a noun phrase itself.

- The woman who stole all the cheese was never seen again.

- Whoever stole all the cheese is going to be caught one day.

In this example, the relative clause could be treated, in terms of position, in the same way as a noun phrase, taking the place of an object or the subject:

- We will catch whoever stole the cheese.

For more information on this, check out the ELB guide to simple, compound and complex sentences.

That’s the end of my introduction to sentence structure and word order, but as noted throughout this article there are plenty more articles on this website for further information. And if you want a full discussion of these topics be sure to check out the bestselling guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook on this site and from all major retailers in paperback format.

Get the Complete Word Order Guide

This article is expanded upon in the bestselling grammar guide, Word Order in English Sentences, available in eBook and paperback.

If you found this useful, check out the complete book for more.

Grade Levels: 3-5, 6-8, K-3

In the BrainPOP ELL movie, We Planned the Trip (L2U5L4), Ben is packing for a beach vacation. He and Moby have to leave very early the next morning. Will they make it to the bus on time? In this lesson plan, adaptable for grades K-8, students practice correct word order through collaborative, hands-on, interactive activities.

Students will:

- Match sentence halves and then arrange them in sequential order of the movie.

- Build sentences with multiple adjectives in a group activity.

- Collaborate with classmates manipulating words and phrases to construct sentences with the correct order.

Vocabulary:

Word order, subject, verb, indirect object, direct object, adjective, adverb of frequency

Preparation:

For Activity 1, Match-a-Sentence, write the following phrases from the movie on strips of paper. Fold the strips and put them in a container.

We’re going on vacation

in the morning.

We planned the trip

last winter.

We’re returning

on Saturday night.

Our bus leaves tomorrow

at seven o’clock in the morning.

I bought a suitcase

for you.

I bought you

a big suitcase.

It’s usually sunny

at the beach.

Please give the blue, striped towel

to me.

I gave you my sweater

last week.

I’ll see you in the morning,

at 6:45.

For Activity 2, Build-a-Sentence Roundtable, make enough copies of the Order of Adjectives Chart for each group of students. You will need at least one chart for each group. On each page, write in a different noun in the Noun column of the blank table. Leave the rest of the columns blank. Choose nouns that can be described with multiple adjectives, such as: table, hat, painting, horse, book, building, etc.

For Activity 3, Wizards of Word Order, prepare cards with the following words/phrases. Color code the cards (make all words of the same sentence the same color, but give each sentence a different color).

We / always / meet / at the bus stop / after school.

My cousin / is / never / sick.

I / baked / a / big / round / chocolate / cake / for you.

She / gave / him / a ride / home / on Tuesday.

Lesson Procedure:

- Match-a-Sentence. After watching the movie We Planned the Trip (L2U5L4), have students take a sentence strip (see Preparation) out of the container. Explain to students that each phrase goes with one other phrase to create a complete sentence from the movie. The object of the game is to find the student holding the other phrase. When students find their match, instruct them to say the sentence aloud and then to identify another way to say the same sentence by putting the words in a different order. Provide an example, such as:

Original sentence: Ben gave Moby his sweater.

Alternative: Ben gave his sweater to Moby.When students are ready, have them arrange themselves to stand in order of the sequence of events in the movie. To facilitate discussion, put a bank of sequence expressions on the board, such as first, second, third, then, next, last, before that, after that. If they are not sure of the order, then show the movie again. Then have them share their original and alternative sentences, in the correct order. NOTE: The correct order is listed in the Preparation section of this lesson plan.

- Build-a-Sentence Roundtable. To review the order of adjectives before doing this activity, cue up the Grammar section of the movie We Planned the Trip (L2U5L4), to the part titled “Word Order (Adjectives).” The order is as follows:

opinion (example: interesting book)

size (example: big dog)

age (example: old man)

shape (example: square table)

color (example: blue eyes)

origin (example: French cheese)

material (example: metal box)

purpose/qualifier (example: cookie tray)Divide the class into groups of 4-8 students, and distribute one of the Order of Adjectives Chart charts to each group. Each group chooses any five nouns to fill in the NOUN column. Then in a Roundtable activity, students pass the page around, each adding one adjective to the blank table, in any appropriate column. When they can’t think of any more adjectives, then have each group read out their sentences using this structure: It’s a favorite, big old, blue, cotton sweater. Alternatively, give the same nouns to the class, to compare their finished sentences.

- Wizards of Word Order. Distribute the color-coded word cards to students (see Preparation). Call up students with the same color cards to the front of the classroom. Challenge them to form a sentence by putting the words in the correct order.

As an extra challenge, invite small groups to create and then cut up sentences that include adverbs of frequency, adjectives, time expressions, and/or prepositions of time. Have them swap their sentences with another small group and challenge each other to reconstruct the sentences with the words in the correct order.