Each

sentence can be spoken of in different aspects. A syntactic aspect

implies the sentence analysis in terms of parts of the sentence

(sentence subject, predicate, object, attribute, adverbial modifier).

Syntax reveals the relation of sentence parts to each other. A

semantic aspect implies the relation of sentence components to the

elements of the real situation named by the sentence. This can be

done in terms of case grammar139or reference theory,140or by singling out the agent, object and other semantic roles. A

third aspect is pragmatic, or communicative. It implies the relation

of the sentence to its users. The speaker makes up a sentence so as

to stress logically this or that part of the information conveyed by

the sentence. Therefore, this type of sentence structure is called

information (communicative) structure, and this type of sentence

analysis is referred to as actual division of the sentence,141or functional sentence perspective.142

Normally,

each sentence develops from a known piece of information, called the

theme,

to a new one, called the rheme.

The rhematic component is the information center of the sentence. It

is logically stressed. It can be easily singled out in speech by

contrasting it to some other word: The

early bird catches the worm, not the trap. The early bird catches the

worm, not the late one. The

rhematic word usually answers a special question: e.g., Whom

does the early bird catch? — The early bird catches the

worm.

What kind of bird catches the worm? – The early

bird catches the worm.

In addition to the methods of contrasting and questioning, there are

some other signals for the rhematic component. They include:

-

the

indefinite article of the sentence subject: A

little evil

is often necessary for obtaining a great good. -

a

long extended part of the sentence; compare: Many

people

saw it. – People saw

it. -

negation:

Not

he

who has much is rich, but he who gives much. -

intensifiers

(only,

even, just, such as, etc.):

Only

the educated

are free. (Cf.

The educated are free.) -

some

special constructions (there

is; it is… (who); passive

constructions with the by-agent

expressed):

It is human

nature

to think wisely and to act foolishly.

The

sentence communicative structure is different in English and in

Russian. In Russian it is more rigid, which compensates a loose word

order of the sentence. English fixed word order, on the other hand,

is compensated by a free, to some extent, functional sentence

perspective. In Russian neutral style, the theme precedes the rheme,

which means that a logically stressed part of the sentence is in the

final position. In English, the rheme can be interrupted by the theme

or even precede the theme: There

is an

unknown word

in the text. (T-R-T)

– В тексте

есть незнакомое

слово.

(T-R).

§2. Word order change due to the functional sentence perspective

When

the English and Russian functional sentence perspectives do not

coincide, a word order change is applied in translation.

Thus,

the rhematic subject in English usually takes the initial position,

whereas in Russian it should be placed at the end of the sentence: A

faint perfume of jasmine

came through the open window. (O.Wilde) – Сквозь

открытое

окно

доносился

легкий

аромат

жасмина.

A

waitress

came to their table. – К

их

столику

подошла

официантка.

This

transformation is evident in comparing the structures with the

subjects introduced by the definite and indefinite articles. A

sentence that has the definite article with the subject has the same

word order: The

woman entered the house. – Женщина

вошла

в

дом.

On

the other hand, a word order change takes place in a similar sentence

if its subject is determined by the indefinite article: A

woman entered the house. – В

дом

вошла

женщина.

To

emphasize the rhematic subject of the sentence, the construction it

is … that (who)

can be used in English. For example, It

is not by means of any tricks or devices that the remarkable effect

of Milton’s verse is produced. – Удивительный

эффект

стихов

Мильтона

объясняется

вовсе

не

какими—то

особыми

ухищрениями.143The

rhematic component is positioned at the end of the Russian sentence.

Another

example: It

was the Russian-born American physicist Vladimir Zworykin who made

the first electronic television in the 1920s. – Именно

Владимир

Зворыкин,

американский

физик

русского

происхождения,

создал

электронный

телевизор

в

20-х

годах

XX столетия.

In

Russian, the emphasis on the semantic center of the sentence is made

either with the help of the intensifier (именно),

or else the meaning can be rendered through a change of word order:

Электронный

телевизор

в

20-х

годах

XX столетия

создал

Владимир

Зворыкин,

американский

физик

русского

происхождения.

Thematic

components in Russian are shifted to the initial position, which

often happens with objects and adverbial modifiers: It

was early for

that.

– Для

этого

еще

было

рано.

A

typical case is the sentence introduced by there

is/are.

Here the subject is rhematic and the adverbial modifier of place is

thematic. Therefore, the construction is normally translated into

Russian with the adverbial in the initial position: There

is a book on the table. – На

столе

лежит

книга.

Compare

this sentence with one of a thematic subject: The

book is on the table. – Книга

лежит

на

столе.

If

there is no adverbial modifier of place in the English sentence (to

start the translation), the sentence beginning with there

is

is rendered in Russian by the verb существует:

There are three kinds of solid body. – Существует

три

вида

твердого

тела.

Adverbial

modifiers of place and time are usually mirrored in translation.

Being thematic, they are positioned in the beginning of the Russian

sentence, and in English they take the final position: Вчера

в

Москве

состоялась

встреча

президента

России

с

президентом

Франции.

– A meeting of the Russian president and the French president was

held in

Moscow yesterday.

A

rhematic component expressing the agent of the action in the passive

construction cannot be placed as the initial subject of the

translated sentence: The

telephone was invented by

A. Bell.

corresponds

to Телефон

изобрел

А.

Белл.

(not

to А.

Белл

изобрел

телефон.)

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Tamara I. Leontieva Lectures on Translation Theory Department of Cross-cultural Communication and Translation Study Foreign Languages Center Vladivostok State University of Economics 2008

STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRANSLATION 1. An Overview of Grammar Transformations 2. Translation of Phrase Epithets and Attributive Clusters (or: Collocations). 3. Complex Transformations. 4. Communicative Structure of the English and Russian Sentences. Word Order Change due to the Functional Sentence Perspective.

An Overview of Grammar Transformations — 1 Rule: For an equivalent translation do not mirror the grammar forms of the ST! Choose between the parallel forms and various grammar transformations. E. g. : 1. Translation of infinitive forms: perfect, active and passive, indefinite and continuous. The train seems to arrive at 5 vs The train seems to have arrived at 5.

An Overview of Grammar Transformations — 2 2. Translation of continuative infinitive: a) Parliament was dissolved not to meet again for 11 years. b) He came home to find his wife gone. 3. Substitution of parts of speech: a) Ben’s illness was public knowledge. b) His style of writing is reminiscent of Melville’s.

An Overview of Grammar Transformations — 3 Sentences with the verb-predicate in the Passive voice are more frequent in English than in Russian. Why? a) Almost complete absence of cases in the English language, hence the impossibility to express the object of the action by one of the case form. b) The Passive voice in English is used not only with transitive, but also with nontransitive.

An Overview of Grammar Transformations — 4 1. Мы были приглашены на официальный прием. Нас пригласили на официальный прием. —> We have been invited to a public reception. 2. The room was not lived in. — В комнате никто не жил (non-transitive verb). 3. Double Passive: The treaty is reported to have been signed. Cooбщают, что договор уже подписан обеими сторонами.

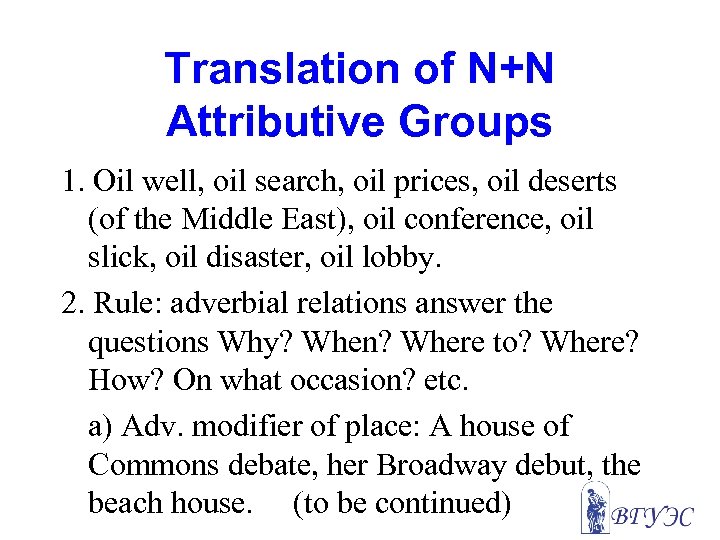

Translation of N+N Attributive Groups 1. Oil well, oil search, oil prices, oil deserts (of the Middle East), oil conference, oil slick, oil disaster, oil lobby. 2. Rule: adverbial relations answer the questions Why? When? Where to? Where? How? On what occasion? etc. a) Adv. modifier of place: A house of Commons debate, her Broadway debut, the beach house. (to be continued)

Translation of N+N Attributive Groups — 2 b) Adv. modifier of time: the Boer War title, holiday snaps. c) Adv. modifier of cause: inflation fears, cholera death. d) Object: dam builders, price explosion, earthquake prediction. e) Translation synonymous to Possessive case: pilot error, the Radley house.

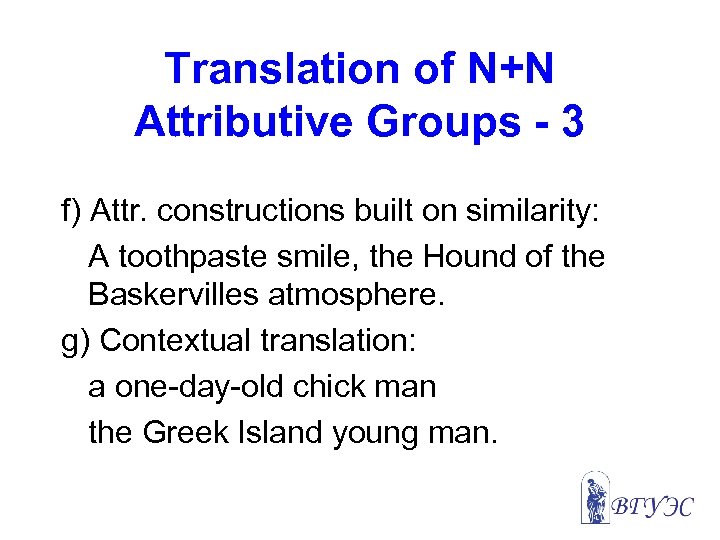

Translation of N+N Attributive Groups — 3 f) Attr. constructions built on similarity: A toothpaste smile, the Hound of the Baskervilles atmosphere. g) Contextual translation: a one-day-old chick man the Greek Island young man.

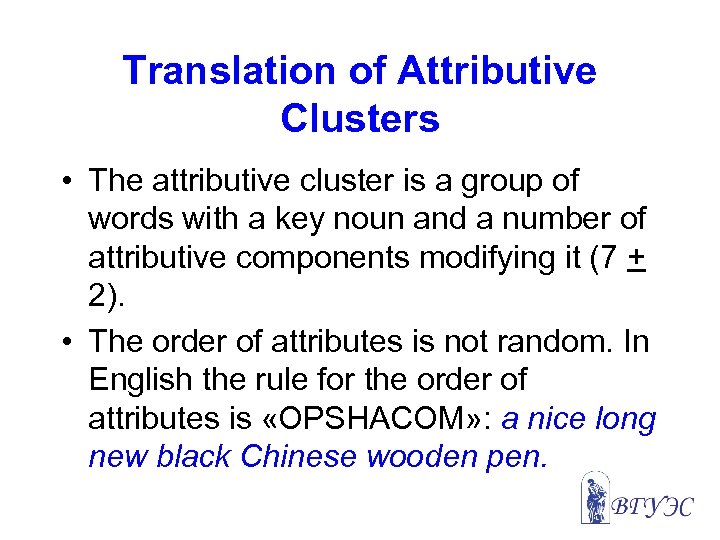

Translation of Attributive Clusters • The attributive cluster is a group of words with a key noun and a number of attributive components modifying it (7 + 2). • The order of attributes is not random. In English the rule for the order of attributes is «OPSHACOM» : a nice long new black Chinese wooden pen.

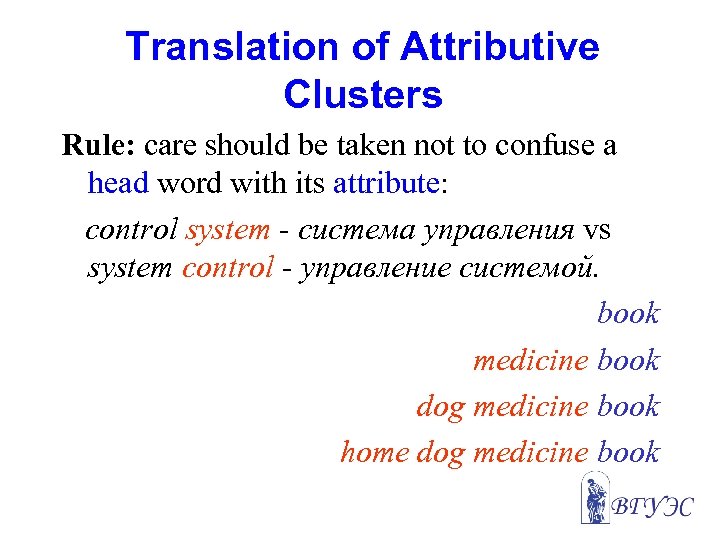

Translation of Attributive Clusters Rule: care should be taken not to confuse a head word with its attribute: control system — система управления vs system control — управление системой. book medicine book dog medicine book home dog medicine book

Translation of Attributive Clusters — 2 Translate carefully! The poll tax the poll tax states governors conference NB! Usually the translation starts with the final word of such a multi-member attributive group.

Complex Transformations 1. He is a three-time loser at marriage. Он был три раза неудачно женат. 2. May I trouble you to pass the salt? Передайте соль, пожалуйста.

Complex Transformations — 2 3. I don’t think you’re right. Думаю (боюсь), вы не правы. 4. But he turned out badly, he drank, then took to drugs. Но из него ничего хорошего не вышло – он начал пить, потом пристрастился к наркотикам.

Communicative Structure of the English and Russian Sentence Rule: Each sentence develops from a known piece of information called theme to a new one called the rheme and the sentence analysis in this case is referred to as functional sentence perspective. In the Russian sentence the rheme is placed at the end, in English it is mainly initial or elsewhere.

The Location of the Rheme 1. A boy entered the room. 2. He went to London. 3. He delivered a lecture yesterday. 1. В комнату вошел мальчик. 2. Он поехал в Лондон. 3. Вчера он читал лекцию.

Determiners of the Rheme in the English Sentence 1. The indefinite article: A waitress came to their table. 2. «No» with the subject: No machinery is needed to perform this test. 3. Intensifying words (or phrases): Only the educated are free.

Determiners of the Rheme in the English Sentence — 2 4. Inverted constructions: There is a book on the desk. 5. «By-agent» in the passive construction: The telephone was invented by Bell.

Home assignment — 1 Proshina Z. G. Theory of translation. 1. Pp. 40 -42: Grammar transformations. 2. Pp. 121 -124: Translating attributive clusters. 3. Pp. 44 -46: Complex transformations. 4. Pp. 125 -128: Functional sentence perspective and translation. Read and make notes. Be able to explain them.

Home assignment -2 1. Read: Романова С. П. , Коралова А. Л. Пособие по переводу. С. 91 -96. Make copies. Be able to discuss the material. 2. Read: Казакова Т. А. Практические основы перевода. С. 210 -223. Pay special attention to Pp. 222 -223.

Данное исследование находится в русле проблем истории формирования религиозного стиля русского языка. Предметом рассмотрения являются имена существительных религиозной семантики на -ств/о/, зафиксированные в отечественных лексикографических произведениях гражданской печати XVIII в., наиболее полно описывающих конфессиональную лексику: «Церковном словаре» протоиерея Петра Алексеева (1773–1794 гг.), «Кратком словаре славянском» игумена Евгения (Романова) (1784 г.) и «Словаре Академiи Россiйской» (1789–1794 гг.). Охарактеризованы словообразовательные и семантические особенности религионимов-субстантивов на -ств/о/, описаны их лексико-грамматические разряды и тематические группы, в рамках этих групп выявлены новообразования XVIII века. Установлены и проанализированы словообразовательные параллели имен существительных религиозной семантики на -ств/о/, возникшие в русском языке связи с активным развитием различных словообразовательных моделей. Показано, что, несмотря на ощутимую конкуренцию, обусловленную наличием синонимичных дериватов, религионимы-субстантивы на -ств/о/ широко представлены в словарной системе русского языка XVIII в., образуя особый лексический пласт конфессиональной лексики. Отмечено, что данный класс слов, как и в целом русский религиозный стиль, находился в XVIII в. в состоянии активного формирования.

Рецензенты:

В.П.Кочетков, канд. филол. наук, профессор;

Элизабет Стэнсиу (языковой редактор), магистр гум. наук, волонтер Корпуса мира

Прошина З.Г.

П 78 ТЕОРИЯ ПЕРЕВОДА (с английского языка на русский и с русского языка на английский): Уч. на англ. яз. – Владивосток: Изд-во Дальневост. ун-та, 2008 (3-е изд., перераб.), 2002 (2-е изд., испр. и перераб.), 1999 (1-е изд.)

ISBN 5-7444-0957-2

Учебник по теории перевода предназначен для студентов переводческих отделений. Созданный на основе типовой программы по переводу, он раскрывает такие разделы, как общая и частная теория перевода; последняя основывается на сопоставлении английского и русского языков.

Может быть рекомендован студентам, преподавателям, переводчикам-практикам и всем тем, кто интересуется вопросами изучения иностранных языков и перевода.

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ 7

PART I. GENERAL ISSUES OF TRANSLATION 8

CHAPTER 1. What Is Translation? 8

§ 1. TRANSLATION STUDIES 8

§ 2. SEMIOTIC APPROACH 9

§ 3. COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH 10

§ 4. DIALECTICS OF TRANSLATION 12

§ 5. TRANSLATION INVARIANT 13

§ 6. UNIT OF TRANSLATION 14

Chapter 2. TYPES OF TRANSLATION 15

§ 1. CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA 15

§ 2. MACHINE TRANSLATION 16

§ 3. TRANSLATION AND INTERPRETING 18

§ 4. FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATION 22

Chapter 3. EVALUATIVE CLASSIFICATION OF TRANSLATION 22

§ 1. ADEQUATE AND EQUIVALENT TRANSLATION 22

§ 2. LITERAL TRANSLATION 24

§ 3. FREE TRANSLATION 26

§ 4. THE CONCEPT OF ‘UNTRANSLATABILITY’ 27

CHAPTER 4. Translation Equivalence 29

§ 1. TYPES OF EQUIVALENCE 29

§ 2. PRAGMATIC LEVEL 30

§ 3. SITUATIONAL LEVEL 31

§ 4. SEMANTIC PARAPHRASE 31

§ 5. TRANSFORMATIONAL EQUIVALENCE 32

§ 6. LEXICAL AND GRAMMATICAL EQUIVALENCE 33

§ 7. THE LEVELS OF EQUIVALENCE HIERARCHY 33

CHAPTER 5. Ways of Achieving Equivalence 34

§ 1. TYPES OF TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES 34

§ 2. TRANSLATION TRANSCRIPTION 35

§ 3. TRANSLITERATION 37

§ 4. CАLQUE TRANSLATION 40

§ 5. GRAMMAR TRANSFORMATIONS 41

§ 6. LEXICAL TRANSFORMATIONS 43

§ 7. COMPLEX TRANSFORMATIONS 45

CHAPTER 6. Translation Models 47

§ 1. TRANSLATION PROCESS 47

§ 2. SITUATIONAL MODEL OF TRANSLATION 48

§ 3. TRANSFORMATIONAL MODEL OF TRANSLATION 50

§ 4. SEMANTIC MODEL OF TRANSLATION 51

§ 5. PSYCHOLINGUISTIC MODEL OF TRANSLATION 52

PART II. HISTORY OF TRANSLATION 246

Chapter 1. WESTERN TRADITIONS OF TRANSLATION 247

§ 1. TRANSLATION DURING ANTIQUITY 247

§ 2. TRANSLATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES 248

§ 3. RENAISSANCE TRANSLATION 249

§ 4. ENLIGHTENMENT TRANSLATION (17-18th c.) 252

§ 5. TRANSLATION IN THE 19TH CENTURY 254

§ 6. TRANSLATION IN THE 20TH CENTURY 257

Chapter 2. HISTORY OF RUSSIAN TRANSLATION 258

§ 1. OLD RUSSIAN CULTURE AND TRANSLATION 258

§2. TRANSLATION IN THE 18TH CENTURY 260

§ 3. RUSSIAN TRANSLATION IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE 19TH CENTURY 264

§4. TRANSLATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 19TH CENTURY 268

§5. TRANSLATION AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY 270

§6. TRANSLATION IN THE 20TH CENTURY 271

PART III. GRAMMAR PROBLEMS OF TRANSLATION 54

Chapter 1. FORMAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SOURCE TEXT AND TARGET TEXT 54

Source language and target language texts differ formally due to a number of reasons of both objective and subjective character. Objective reasons are caused by the divergence in the language systems and speech models. Subjective reasons can be attributed to the speaker’s choice of a language form. 54

Chapter 2. TRANSLATING FINITE VERB FORMS 56

§1. TRANSLATING TENSE AND ASPECT FORMS 56

§2. TRANSLATING PASSIVE VOICE FORMS 59

§3. TRANSLATING THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD FORMS 61

Chapter 3. TRANSLATING NON-FINITE VERB FORMS 63

§1. TRANSLATING THE INFINITIVE 63

§2. TRANSLATING THE GERUND 66

§3. TRANSLATING THE PARTICIPLE 68

§4. TRANSLATING ABSOLUTE CONSTRUCTIONS 70

Chapter 4. TRANSLATING CAUSATIVE CONSTRUCTIONS 74

§1. TYPES OF CAUSATIVE CONSTRUCTIONS 74

§2. CONSTRUCTIONS WITH CAUSAL VERBS 75

§3. CONSTRUCTIONS WITH THE VERBS TO HAVE, TO GET 76

§4. CAUSATIVE CONSTRUCTIONS WITH NON-CAUSAL VERBS 78

Chapter 5. TRANSLATING PRONOUNS 78

§1. TRANSLATING PERSONAL PRONOUNS 78

§2. TRANSLATING POSSESSIVE PRONOUNS 81

§3. TRANSLATING RELATIVE PRONOUNS 83

§4. TRANSLATING THE PRONOUN ONE 83

§5. TRANSLATING THE PRONOUNS КАЖДЫЙ / ВСЕ 85

§6. TRANSLATING PARTITIVE PRONOUNS SOME / ANY 85

§7. TRANSLATING DEMONSTRATIVE PRONOUNS 86

Chapter 6. TRANSLATING THE ARTICLE 88

§1. TRANSLATING THE INDEFINITE ARTICLE 88

§2. TRANSLATING THE DEFINITE ARTICLE 91

§3. TRANSLATING THE ZERO ARTICLE 92

Chapter 7. TRANSLATING ATTRIBUTIVE CLUSTERS 94

§1. FEATURES OF THE ATTRIBUTIVE PHRASE 94

§2. TRANSLATING THE ATTRIBUTIVE CLUSTER. 95

Chapter 8. SYNTACTIC CHANGES IN TRANSLATION 98

§1. COMMUNICATIVE STRUCTURE OF THE ENGLISH AND RUSSIAN SENTENCE 98

§2. WORD ORDER CHANGE DUE TO THE FUNCTIONAL SENTENCE PERSPECTIVE 99

§3. SENTENCE PARTITIONING AND INTEGRATION 101

Chapter 9. DIFFERENCE IN ENGLISH AND RUSSIAN PUNCTUATION 103

§1. PRINCIPLES OF PUNCTUATION IN ENGLISH AND RUSSIAN 103

§2. DIFFERENCES IN COMMA USAGE 104

§3. USING THE DASH 106

§4. USING QUOTATION MARKS 107

§5. USING THE COLON AND SEMICOLON 108

§6. USING THE ELLIPSES 108

PART IV. SEMANTIC PROBLEMS OF TRANSLATION 110

Chapter 1. WORD CHOICE IN TRANSLATION 110

§1. TYPES OF TRANSLATION EQUIVALENTS 110

§2. INTERACTION OF WORD SEMANTIC STRUCTURES 111

§3. WORD CONNOTATION IN TRANSLATION 112

§4. INTRALINGUISTIC MEANING 114

§5. CONTEXUALLY-BOUND WORDS 115

Chapter 2. TRANSLATING REALIA 117

§1. CULTURE-BOUND AND EQUIVALENT-LACKING WORDS 117

§2. TYPES OF CULTURE-BOUND WORDS 118

§3. WAYS OF TRANSLATING CULTURE-BOUND WORDS 120

§4. TRANSLATING PEOPLE’S NAMES 121

§5. TRANSLATING GEOGRAPHICAL TERMS 124

§6. TRANSLATING PUBLISHED EDITIONS 126

§7. TRANSLATING ERGONYMS 127

Chapter 3. TRANSLATING TERMS 127

§1. TRANSLATION FACTORS 127

§2. TRANSLATION TECHNIQUE 130

§3. TERMS IN FICTION AND MAGAZINES 132

Chapter 4. TRANSLATOR’S FALSE FRIENDS 133

Chapter 5. PHRASEOLOGICAL AND METAPHORICAL TRANSLATION 137

§1. METAPHOR AND THE PHRASEOLOGICAL UNIT 137

§2. INTERLINGUAL METAPHORIC TRANSFORMATIONS 138

§3. WAYS OF TRANSLATING IDIOMS 139

§4. CHALLENGES IN TRANSLATING IDIOMS 142

Chapter 6. METONYMICAL TRANSLATION 143

§1. DEFINITIONS 143

§2. LEXICAL METONYMIC TRANSFORMATION 145

§3. PREDICATE TRANSLATION 145

§4. SYNTACTIC METONYMIC TRANSFORMATIONS 147

Chapter 7. ANTONYMIC TRANSLATION 149

§1. DEFINITION 149

§2. CONVERSIVE TRANSFORMATION 149

§3. SHIFTING NEGATIVE MODALITY 150

§4. REASONS FOR ANTONYMIC TRANSLATION 151

Chapter 8. DIFFERENCES IN RUSSIAN AND ENGLISH WORD COMBINABILITY 152

§1. REASONS FOR DIFFERENCES IN WORD COMBINABILITY 152

§2. TRANSLATION OF ADVERBIAL VERBS 154

§3. TRANSLATING CONDENSED SYNONYMS 156

Chapter 9. TRANSLATING NEW COINAGES: DIFFERENCES IN RUSSIAN AND ENGLISH WORD BUILDING 157

§1. COMPOUNDS 157

§2. CONVERSION 159

§3. AFFIXATION 162

§4. ABBREVIATION 164

PART V. PRAGMATIC PROBLEMS OF TRANSLATION 168

Chapter 1. TRANSLATION PRAGMATICS 168

§1. CONCEPT OF PRAGMATICS 168

§2. TEXT PRAGMATICS 169

§3. AUTHOR’S COMMUNICATIVE INTENTION 171

§4. COMMUNICATIVE EFFECT UPON THE RECEPTOR 175

§5. TRANSLATOR’S IMPACT 178

Chapter 2. SPEECH FUNCTIONS AND TRANSLATION 179

§1. LANGUAGE AND SPEECH FUNCTIONS 179

§2. INTERPERSONAL FUNCTION AND MODALITY IN TRANSLATION. 180

§3. EXPRESSIVE FUNCTION IN TRANSLATION 186

§4. PHATIC FUNCTION IN TRANSLATION 190

§5. CONATIVE FUNCTION IN TRANSLATION 194

Chapter 3. FUNCTIONAL STYLES AND TRANSLATION 197

§1. FUNCTIONAL STYLE, REGISTER: DEFINITION 197

§2. TRANSLATING SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL STYLE 198

§3. TRANSLATING BUREAUCRATIC STYLE 202

§4. TRANSLATING JOURNALISTIC (PUBLICISTIC) STYLE 206

Chapter 4. RENDERING STYLISTIC DEVICES IN TRANSLATION 211

§1. TRANSLATION OF METAPHORS AND SIMILES 211

§2. TRANSLATION OF EPITHETS 214

§3. TRANSLATION OF PERIPHRASE 215

§4. TRANSLATION OF PUNS 217

§5. TRANSLATION OF ALLUSIONS AND QUOTATIONS 220

Chapter 5. TRANSLATION NORMS AND QUALITY CONTROL OF A TRANSLATION 220

§1. NORMS OF TRANSLATION 221

§2. QUALITY CONTROL OF THE TRANSLATION. 225

Chapter 6. TRANSLATION ETIQUETTE 228

§1. PROFESSIONAL ETHICS, ETIQUETTE, AND PROTOCOL 229

§2. CODE OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT 229

§3. PROTOCOL CEREMONIES 232

APPENDIX 1. 235

Russian-English Transliteration Chart 235

APPENDIX 2. 236

Russian-English-Chinese Transliteration Chart 236

Учебное издание 244

Зоя Григорьевна Прошина 244