In linguistics, word order (also known as linear order) is the order of the syntactic constituents of a language. Word order typology studies it from a cross-linguistic perspective, and examines how different languages employ different orders. Correlations between orders found in different syntactic sub-domains are also of interest. The primary word orders that are of interest are

- the constituent order of a clause, namely the relative order of subject, object, and verb;

- the order of modifiers (adjectives, numerals, demonstratives, possessives, and adjuncts) in a noun phrase;

- the order of adverbials.

Some languages use relatively fixed word order, often relying on the order of constituents to convey grammatical information. Other languages—often those that convey grammatical information through inflection—allow more flexible word order, which can be used to encode pragmatic information, such as topicalisation or focus. However, even languages with flexible word order have a preferred or basic word order,[1] with other word orders considered «marked».[2]

Constituent word order is defined in terms of a finite verb (V) in combination with two arguments, namely the subject (S), and object (O).[3][4][5][6] Subject and object are here understood to be nouns, since pronouns often tend to display different word order properties.[7][8] Thus, a transitive sentence has six logically possible basic word orders:

- about half of the world’s languages deploy subject–object–verb order (SOV);

- about one-third of the world’s languages deploy subject–verb–object order (SVO);

- a smaller fraction of languages deploy verb–subject–object (VSO) order;

- the remaining three arrangements are rarer: verb–object–subject (VOS) is slightly more common than object–verb–subject (OVS), and object–subject–verb (OSV) is the rarest by a significant margin.[9]

Constituent word orders[edit]

These are all possible word orders for the subject, object, and verb in the order of most common to rarest (the examples use «she» as the subject, «loves» as the verb, and «him» as the object):

- SOV is the order used by the largest number of distinct languages; languages using it include Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Turkish, the Indo-Aryan languages and the Dravidian languages. Some, like Persian, Latin and Quechua, have SOV normal word order but conform less to the general tendencies of other such languages. A sentence glossing as «She him loves» would be grammatically correct in these languages.

- SVO languages include English, Spanish, Portuguese, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian,[10] the Chinese languages and Swahili, among others. «She loves him.»

- VSO languages include Classical Arabic, Biblical Hebrew, the Insular Celtic languages, and Hawaiian. «Loves she him.»

- VOS languages include Fijian and Malagasy. «Loves him she.»

- OVS languages include Hixkaryana. «Him loves she.»

- OSV languages include Xavante and Warao. «Him she loves.»

Sometimes patterns are more complex: some Germanic languages have SOV in subordinate clauses, but V2 word order in main clauses, SVO word order being the most common. Using the guidelines above, the unmarked word order is then SVO.

Many synthetic languages such as Latin, Greek, Persian, Romanian, Assyrian, Assamese, Russian, Turkish, Korean, Japanese, Finnish, Arabic and Basque have no strict word order; rather, the sentence structure is highly flexible and reflects the pragmatics of the utterance. However, also in languages of this kind there is usually a pragmatically neutral constituent order that is most commonly encountered in each language.

Topic-prominent languages organize sentences to emphasize their topic–comment structure. Nonetheless, there is often a preferred order; in Latin and Turkish, SOV is the most frequent outside of poetry, and in Finnish SVO is both the most frequent and obligatory when case marking fails to disambiguate argument roles. Just as languages may have different word orders in different contexts, so may they have both fixed and free word orders. For example, Russian has a relatively fixed SVO word order in transitive clauses, but a much freer SV / VS order in intransitive clauses.[citation needed] Cases like this can be addressed by encoding transitive and intransitive clauses separately, with the symbol «S» being restricted to the argument of an intransitive clause, and «A» for the actor/agent of a transitive clause. («O» for object may be replaced with «P» for «patient» as well.) Thus, Russian is fixed AVO but flexible SV/VS. In such an approach, the description of word order extends more easily to languages that do not meet the criteria in the preceding section. For example, Mayan languages have been described with the rather uncommon VOS word order. However, they are ergative–absolutive languages, and the more specific word order is intransitive VS, transitive VOA, where the S and O arguments both trigger the same type of agreement on the verb. Indeed, many languages that some thought had a VOS word order turn out to be ergative like Mayan.

Distribution of word order types[edit]

Every language falls under one of the six word order types; the unfixed type is somewhat disputed in the community, as the languages where it occurs have one of the dominant word orders but every word order type is grammatically correct.

The table below displays the word order surveyed by Dryer. The 2005 study[11] surveyed 1228 languages, and the updated 2013 study[8] investigated 1377 languages. Percentage was not reported in his studies.

| Word Order | Number (2005) | Percentage (2005) | Number (2013) | Percentage (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 497 | 40.5% | 565 | 41.0% |

| SVO | 435 | 35.4% | 488 | 35.4% |

| VSO | 85 | 6.9% | 95 | 6.9% |

| VOS | 26 | 2.1% | 25 | 1.8% |

| OVS | 9 | 0.7% | 11 | 0.8% |

| OSV | 4 | 0.3% | 4 | 0.3% |

| Unfixed | 172 | 14.0% | 189 | 13.7% |

Hammarström (2016)[12] calculated the constituent orders of 5252 languages in two ways. His first method, counting languages directly, yielded results similar to Dryer’s studies, indicating both SOV and SVO have almost equal distribution. However, when stratified by language families, the distribution showed that the majority of the families had SOV structure, meaning that a small number of families contain SVO structure.

| Word Order | No. of Languages | Percentage | No. of Families | Percentage[a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 2275 | 43.3% | 239 | 56.6% |

| SVO | 2117 | 40.3% | 55 | 13.0% |

| VSO | 503 | 9.5% | 27 | 6.3% |

| VOS | 174 | 3.3% | 15 | 3.5% |

| OVS | 40 | 0.7% | 3 | 0.7% |

| OSV | 19 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Unfixed | 124 | 2.3% | 26 | 6.1% |

Functions of constituent word order[edit]

Fixed word order is one out of many ways to ease the processing of sentence semantics and reducing ambiguity. One method of making the speech stream less open to ambiguity (complete removal of ambiguity is probably impossible) is a fixed order of arguments and other sentence constituents. This works because speech is inherently linear. Another method is to label the constituents in some way, for example with case marking, agreement, or another marker. Fixed word order reduces expressiveness but added marking increases information load in the speech stream, and for these reasons strict word order seldom occurs together with strict morphological marking, one counter-example being Persian.[1]

Observing discourse patterns, it is found that previously given information (topic) tends to precede new information (comment). Furthermore, acting participants (especially humans) are more likely to be talked about (to be topic) than things simply undergoing actions (like oranges being eaten). If acting participants are often topical, and topic tends to be expressed early in the sentence, this entails that acting participants have a tendency to be expressed early in the sentence. This tendency can then grammaticalize to a privileged position in the sentence, the subject.

The mentioned functions of word order can be seen to affect the frequencies of the various word order patterns: The vast majority of languages have an order in which S precedes O and V. Whether V precedes O or O precedes V, however, has been shown to be a very telling difference with wide consequences on phrasal word orders.[13]

Semantics of word order[edit]

In many languages, standard word order can be subverted in order to form questions or as a means of emphasis. In languages such as O’odham and Hungarian, which are discussed below, almost all possible permutations of a sentence are grammatical, but not all of them are used.[14] In languages such as English and German, word order is used as a means of turning declarative into interrogative sentences:

A: ‘Wen liebt Kate?’ / ‘Kate liebt wen?’ [Whom does Kate love? / Kate loves whom?] (OVS/SVO)

B: ‘Sie liebt Mark’ / ‘Mark ist der, den sie liebt’ [She loves Mark / It is Mark whom she loves.] (SVO/OSV)

C: ‘Liebt Kate Mark?’ [Does Kate love Mark?] (VSO)

In (A), the first sentence shows the word order used for wh-questions in English and German. The second sentence is an echo question; it would only be uttered after receiving an unsatisfactory or confusing answer to a question. One could replace the word wen [whom] (which indicates that this sentence is a question) with an identifier such as Mark: ‘Kate liebt Mark?’ [Kate loves Mark?]. In that case, since no change in word order occurs, it is only by means of stress and tone that we are able to identify the sentence as a question.

In (B), the first sentence is declarative and provides an answer to the first question in (A). The second sentence emphasizes that Kate does indeed love Mark, and not whomever else we might have assumed her to love. However, a sentence this verbose is unlikely to occur in everyday speech (or even in written language), be it in English or in German. Instead, one would most likely answer the echo question in (A) simply by restating: Mark!. This is the same for both languages.

In yes–no questions such as (C), English and German use subject-verb inversion. But, whereas English relies on do-support to form questions from verbs other than auxiliaries, German has no such restriction and uses inversion to form questions, even from lexical verbs.

Despite this, English, as opposed to German, has very strict word order. In German, word order can be used as a means to emphasize a constituent in an independent clause by moving it to the beginning of the sentence. This is a defining characteristic of German as a V2 (verb-second) language, where, in independent clauses, the finite verb always comes second and is preceded by one and only one constituent. In closed questions, V1 (verb-first) word order is used. And lastly, dependent clauses use verb-final word order. However, German cannot be called an SVO language since no actual constraints are imposed on the placement of the subject and object(s), even though a preference for a certain word-order over others can be observed (such as putting the subject after the finite verb in independent clauses unless it already precedes the verb[clarification needed]).

Phrase word orders and branching[edit]

The order of constituents in a phrase can vary as much as the order of constituents in a clause. Normally, the noun phrase and the adpositional phrase are investigated. Within the noun phrase, one investigates whether the following modifiers occur before and/or after the head noun.

- adjective (red house vs house red)

- determiner (this house vs house this)

- numeral (two houses vs houses two)

- possessor (my house vs house my)

- relative clause (the by me built house vs the house built by me)

Within the adpositional clause, one investigates whether the languages makes use of prepositions (in London), postpositions (London in), or both (normally with different adpositions at both sides) either separately (For whom? or Whom for?) or at the same time (from her away; Dutch example: met hem mee meaning together with him).

There are several common correlations between sentence-level word order and phrase-level constituent order. For example, SOV languages generally put modifiers before heads and use postpositions. VSO languages tend to place modifiers after their heads, and use prepositions. For SVO languages, either order is common.

For example, French (SVO) uses prepositions (dans la voiture, à gauche), and places adjectives after (une voiture spacieuse). However, a small class of adjectives generally go before their heads (une grande voiture). On the other hand, in English (also SVO) adjectives almost always go before nouns (a big car), and adverbs can go either way, but initially is more common (greatly improved). (English has a very small number of adjectives that go after the heads, such as extraordinaire, which kept its position when borrowed from French.) Russian places numerals after nouns to express approximation (шесть домов=six houses, домов шесть=circa six houses).

Pragmatic word order[edit]

Some languages do not have a fixed word order and often use a significant amount of morphological marking to disambiguate the roles of the arguments. However, the degree of marking alone does not indicate whether a language uses a fixed or free word order: some languages may use a fixed order even when they provide a high degree of marking, while others (such as some varieties of Datooga) may combine a free order with a lack of morphological distinction between arguments.

Typologically, there is a trend that high-animacy actors are more likely to be topical than low-animacy undergoers; this trend can come through even in languages with free word order, giving a statistical bias for SO order (or OS order in ergative systems; however, ergative systems do not always extend to the highest levels of animacy, sometimes giving way to an accusative system (see split ergativity)).[15]

Most languages with a high degree of morphological marking have rather flexible word orders, such as Polish, Hungarian, Portuguese, Latin, Albanian, and O’odham. In some languages, a general word order can be identified, but this is much harder in others.[16] When the word order is free, different choices of word order can be used to help identify the theme and the rheme.

Hungarian[edit]

Word order in Hungarian sentences is changed according to the speaker’s communicative intentions. Hungarian word order is not free in the sense that it must reflect the information structure of the sentence, distinguishing the emphatic part that carries new information (rheme) from the rest of the sentence that carries little or no new information (theme).

The position of focus in a Hungarian sentence is immediately before the verb, that is, nothing can separate the emphatic part of the sentence from the verb.

For «Kate ate a piece of cake«, the possibilities are:

- «Kati megevett egy szelet tortát.» (same word order as English) [«Kate ate a piece of cake.«]

- «Egy szelet tortát Kati evett meg.» (emphasis on agent [Kate]) [«A piece of cake Kate ate.«] (One of the pieces of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- «Kati evett meg egy szelet tortát.» (also emphasis on agent [Kate]) [«Kate ate a piece of cake.«] (Kate was the one eating one piece of cake.)

- «Kati egy szelet tortát evett meg.» (emphasis on object [cake]) [«Kate a piece of cake ate.»] (Kate ate a piece of cake – cf. not a piece of bread.)

- «Egy szelet tortát evett meg Kati.» (emphasis on number [a piece, i.e. only one piece]) [«A piece of cake ate Kate.»] (Only one piece of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- «Megevett egy szelet tortát Kati.» (emphasis on completeness of action) [«Ate a piece of cake Kate.»] (A piece of cake had been finished by Kate.)

- «Megevett Kati egy szelet tortát.» (emphasis on completeness of action) [«Ate Kate a piece of cake.«] (Kate finished with a piece of cake.)

The only freedom in Hungarian word order is that the order of parts outside the focus position and the verb may be freely changed without any change to the communicative focus of the sentence, as seen in sentences 2 and 3 as well as in sentences 6 and 7 above. These pairs of sentences have the same information structure, expressing the same communicative intention of the speaker, because the part immediately preceding the verb is left unchanged.

Note that the emphasis can be on the action (verb) itself, as seen in sentences 1, 6 and 7, or it can be on parts other than the action (verb), as seen in sentences 2, 3, 4 and 5. If the emphasis is not on the verb, and the verb has a co-verb (in the above example ‘meg’), then the co-verb is separated from the verb, and always follows the verb. Also note that the enclitic -t marks the direct object: ‘torta’ (cake) + ‘-t’ -> ‘tortát’.

Hindi-Urdu[edit]

Hindi-Urdu (Hindustani) is essentially a verb-final (SOV) language, with relatively free word order since in most cases postpositions mark quite explicitly the relationships of noun phrases with other constituents of the sentence.[17] Word order in Hindustani usually does not signal grammatical functions.[18] Constituents can be scrambled to express different information structural configurations, or for stylistic reasons. The first syntactic constituent in a sentence is usually the topic,[19][18] which may under certain conditions be marked by the particle «to» (तो / تو), similar in some respects to Japanese topic marker は (wa).[20][21][22][23] Some rules governing the position of words in a sentence are as follows:

- An adjective comes before the noun it modifies in its unmarked position. However, the possessive and reflexive pronominal adjectives can occur either to the left or to the right of the noun it describes.

- Negation must come either to the left or to the right of the verb it negates. For compound verbs or verbal construction using auxiliaries the negation can occur either to the left of the first verb, in-between the verbs or to the right of the second verb (the default position being to the left of the main verb when used with auxiliary and in-between the primary and the secondary verb when forming a compound verb).

- Adverbs usually precede the adjectives they qualify in their unmarked position, but when adverbs are constructed using the instrumental case postposition se (से /سے) (which qualifies verbs), their position in the sentence becomes free. However, since both the instrumental and the ablative case are marked by the same postposition «se» (से /سے), when both are present in a sentence then the quantity they modify cannot appear adjacent to each other[clarification needed].[24][18]

- «kyā » (क्या / کیا) «what» as the yes-no question marker occurs at the beginning or the end of a clause as its unmarked positions but it can be put anywhere in the sentence except the preverbal position, where instead it is interpreted as interrogative «what».

Some of all the possible word order permutations of the sentence «The girl received a gift from the boy on her birthday.» are shown below.

|

|

|

|

|

Portuguese[edit]

In Portuguese, clitic pronouns and commas allow many different orders:[citation needed]

- «Eu vou entregar a você amanhã.» [«I will deliver to you tomorrow.»] (same word order as English)

- «Entregarei a você amanhã.» [«{I} will deliver to you tomorrow.»]

- «Eu lhe entregarei amanhã.» [«I to you will deliver tomorrow.»]

- «Entregar-lhe-ei amanhã.» [«Deliver to you {I} will tomorrow.»] (mesoclisis)

- «A ti, eu entregarei amanhã.» [«To you I will deliver tomorrow.»]

- «A ti, entregarei amanhã.» [«To you deliver {I} will tomorrow.»]

- «Amanhã, entregar-te-ei» [«Tomorrow {I} will deliver to you»]

- «Poderia entregar, eu, a você amanhã?» [«Could deliver I to you tomorrow?]

Braces ({ }) are used above to indicate omitted subject pronouns, which may be implicit in Portuguese. Because of conjugation, the grammatical person is recovered.

Latin[edit]

In Latin, the endings of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and pronouns allow for extremely flexible order in most situations. Latin lacks articles.

The Subject, Verb, and Object can come in any order in a Latin sentence, although most often (especially in subordinate clauses) the verb comes last.[25] Pragmatic factors, such as topic and focus, play a large part in determining the order. Thus the following sentences each answer a different question:[26]

- «Romulus Romam condidit.» [«Romulus founded Rome»] (What did Romulus do?)

- «Hanc urbem condidit Romulus.» [«Romulus founded this city»] (Who founded this city?)

- «Condidit Romam Romulus.» [«Romulus founded Rome»] (What happened?)

Latin prose often follows the word order «Subject, Direct Object, Indirect Object, Adverb, Verb»,[27] but this is more of a guideline than a rule. Adjectives in most cases go before the noun they modify,[28] but some categories, such as those that determine or specify (e.g. Via Appia «Appian Way»), usually follow the noun. In Classical Latin poetry, lyricists followed word order very loosely to achieve a desired scansion.

Albanian[edit]

Due to the presence of grammatical cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and in some cases or dialects vocative and locative) applied to nouns, pronouns and adjectives, the Albanian language permits a large number of positional combination of words. In spoken language a word order differing from the most common S-V-O helps the speaker putting emphasis on a word, thus changing partially the message delivered. Here is an example:

- «Marku më dha një dhuratë (mua).» [«Mark (me) gave a present to me.»] (neutral narrating sentence.)

- «Marku (mua) më dha një dhuratë.» [«Mark to me (me) gave a present.»] (emphasis on the indirect object, probably to compare the result of the verb on different persons.)

- «Marku një dhuratë më dha (mua).» [«Mark a present (me) gave to me»] (meaning that Mark gave her only a present, and not something else or more presents.)

- «Marku një dhuratë (mua) më dha.» [«Mark a present to me (me) gave»] (meaning that Mark gave a present only to her.)

- «Më dha Marku një dhuratë (mua).» [«Gave Mark to me a present.»] (neutral sentence, but puts less emphasis on the subject.)

- «Më dha një dhuratë Marku (mua).» [«Gave a present to me Mark.»] (probably is the cause of an event being introduced later.)

- «Më dha (mua) Marku një dhurate.» [«Gave to me Mark a present.»] (same as above.)

- «Më dha një dhuratë mua Marku» [«(Me) gave a present to me Mark.»] (puts emphasis on the fact that the receiver is her and not someone else.)

- «Një dhuratë më dha Marku (mua)» [«A present gave Mark to me.»] (meaning it was a present and not something else.)

- «Një dhuratë Marku më dha (mua)» [«A present Mark gave to me.»] (puts emphasis on the fact that she got the present and someone else got something different.)

- «Një dhuratë (mua) më dha Marku.» [«A present to me gave Mark.»] (no particular emphasis, but can be used to list different actions from different subjects.)

- «Një dhuratë (mua) Marku më dha.» [«A present to me Mark (me) gave»] (remembers that at least a present was given to her by Mark.)

- «Mua më dha Marku një dhuratë.» [«To me (me) gave Mark a present.» (is used when Mark gave something else to others.)

- «Mua një dhuratë më dha Marku.» [«To me a present (me) gave Mark.»] (emphasis on «to me» and the fact that it was a present, only one present or it was something different from usual.)

- «Mua Marku një dhuratë më dha» [«To me Mark a present (me) gave.»] (Mark gave her only one present.)

- «Mua Marku më dha një dhuratë» [«To me Mark (me) gave a present.»] (puts emphasis on Mark. Probably the others didn’t give her present, they gave something else or the present wasn’t expected at all.)

In these examples, «(mua)» can be omitted when not in first position, causing a perceivable change in emphasis; the latter being of different intensity. «Më» is always followed by the verb. Thus, a sentence consisting of a subject, a verb and two objects (a direct and an indirect one), can be

expressed in six different ways without «mua», and in twenty-four different ways with «mua», adding up to thirty possible combinations.

O’odham (Papago-Pima)[edit]

O’odham is a language that is spoken in southern Arizona and Northern Sonora, Mexico. It has free word order, with only the auxiliary bound to one spot. Here is an example, in literal translation:[14]

- «Wakial ‘o g wipsilo ha-cecposid.» [Cowboy is the calves them branding.] (The cowboy is branding the calves.)

- «Wipsilo ‘o ha-cecposid g wakial.» [Calves is them branding the cowboy.]

- «Ha-cecposid ‘o g wakial g wipsilo.» [Them Branding is the cowboy the calves.]

- «Wipsilo ‘o g wakial ha-cecposid.» [Calves is the cowboy them branding.]

- «Ha-cecposid ‘o g wipsilo g wakial.» [Them branding is the calves the cowboy.]

- «Wakial ‘o ha-cecposid g wipsilo.» [Cowboy is them branding the calves.]

These examples are all grammatically-valid variations on the sentence «The cowboy is branding the calves,» but some are rarely found in natural speech, as is discussed in Grammaticality.

Other issues with word order[edit]

Language change[edit]

Languages change over time. When language change involves a shift in a language’s syntax, this is called syntactic change. An example of this is found in Old English, which at one point had flexible word order, before losing it over the course of its evolution.[29] In Old English, both of the following sentences would be considered grammatically correct:

- «Martianus hæfde his sunu ær befæst.» [Martianus had his son earlier established.] (Martianus had earlier established his son.)

- «Se wolde gelytlian þone lyfigendan hælend.» [He would diminish the living saviour.]

This flexibility continues into early Middle English, where it seems to drop out of usage.[30] Shakespeare’s plays use OV word order frequently, as can be seen from this example:

- «It was our selfe thou didst abuse.»[31]

A modern speaker of English would possibly recognise this as a grammatically comprehensible sentence, but nonetheless archaic. There are some verbs, however, that are entirely acceptable in this format:

- «Are they good?»[32]

This is acceptable to a modern English speaker and is not considered archaic. This is due to the verb «to be», which acts as both auxiliary and main verb. Similarly, other auxiliary and modal verbs allow for VSO word order («Must he perish?»). Non-auxiliary and non-modal verbs require insertion of an auxiliary to conform to modern usage («Did he buy the book?»). Shakespeare’s usage of word order is not indicative of English at the time, which had dropped OV order at least a century before.[33]

This variation between archaic and modern can also be shown in the change between VSO to SVO in Coptic, the language of the Christian Church in Egypt.[34]

Dialectal variation[edit]

There are some languages where a certain word order is preferred by one or more dialects, while others use a different order. One such case is Andean Spanish, spoken in Peru. While Spanish is classified as an SVO language,[35] the variation of Spanish spoken in Peru has been influenced by contact with Quechua and Aymara, both SOV languages.[36] This has had the effect of introducing OV (object-verb) word order into the clauses of some L1 Spanish speakers (moreso than would usually be expected), with more L2 speakers using similar constructions.

Poetry[edit]

Poetry and stories can use different word orders to emphasize certain aspects of the sentence. In English, this is called anastrophe. Here is an example:

«Kate loves Mark.»

«Mark, Kate loves.»

Here SVO is changed to OSV to emphasize the object.

Translation[edit]

Differences in word order complicate translation and language education – in addition to changing the individual words, the order must also be changed. The area in Linguistics that is concerned with translation and education is language acquisition. The reordering of words can run into problems, however, when transcribing stories. Rhyme scheme can change, as well as the meaning behind the words. This can be especially problematic when translating poetry.

See also[edit]

- Antisymmetry

- Information flow

- Language change

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hammarström included families with no data in his count (58 out of 424 = 13,7%), but did not include them in the list. This explains why the percentages do not sum to 100% in this column.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Comrie, Bernard. (1981). Language universals and linguistic typology: syntax and morphology (2nd ed). University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ^ Sakel, Jeanette (2015). Study Skills for Linguistics. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 9781317530107.

- ^ Hengeveld, Kees (1992). Non-verbal predication. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-013713-5.

- ^ Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1993). «Das Nomen – eine universale Kategorie?» [The noun – a universal category?]. STUF — Language Typology and Universals (in German). 46 (1–4). doi:10.1524/stuf.1993.46.14.187. S2CID 192204875.

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (November 2007). «Word Classes: Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00030.x. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2004), The Noun Phrase, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926964-5.

- ^ Greenberg, Joseph H. (1963). «Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements» (PDF). In Greenberg, Joseph H. (ed.). Universals of Human Language. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. pp. 73–113. doi:10.1515/9781503623217-005. ISBN 9781503623217. S2CID 2675113.

- ^ a b Dryer, Matthew S. (2013). «Order of Subject, Object and Verb». In Dryer, Matthew S.; Haspelmath, Martin (eds.). The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ^ Tomlin, Russel S. (1986). Basic Word Order: Functional Principles. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-415-72357-4.

- ^ Kordić, Snježana (2006) [1st pub. 1997]. Serbo-Croatian. Languages of the World/Materials ; 148. Munich & Newcastle: Lincom Europa. pp. 45–46. ISBN 3-89586-161-8. OCLC 37959860. OL 2863538W. Contents. Summary. [Grammar book].

- ^ Dryer, M. S. (2005). «Order of Subject, Object, and Verb». In Haspelmath, M. (ed.). The World Atlas of Language Structures.

- ^ Hammarström, H. (2016). «Linguistic diversity and language evolution». Journal of Language Evolution. 1 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1093/jole/lzw002.

- ^ Dryer, Matthew S. (1992). «The Greenbergian word order correlations». Language. 68 (1): 81–138. doi:10.1353/lan.1992.0028. JSTOR 416370. S2CID 9693254. Project MUSE 452860.

- ^ a b Hale, Kenneth L. (1992). «Basic word order in two «free word order» languages». Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. Typological Studies in Language. Vol. 22. p. 63. doi:10.1075/tsl.22.03hal. ISBN 978-90-272-2905-2.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard (1981). Language Universals and Linguistic Typology: Syntax and Morphology (2nd edn). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Rude, Noel (1992). «Word order and topicality in Nez Perce». Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. Typological Studies in Language. Vol. 22. p. 193. doi:10.1075/tsl.22.08rud. ISBN 978-90-272-2905-2.

- ^ Kachru, Yamuna (2006). Hindi. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 159–160. ISBN 90-272-3812-X.

- ^ a b c Mohanan, Tara (1994). «Case OCP: A Constraint on Word Order in Hindi». In Butt, Miriam; King, Tracy Holloway; Ramchand, Gillian (eds.). Theoretical Perspectives on Word Order in South Asian Languages. Center for the Study of Language (CSLI). pp. 185–216. ISBN 978-1-881526-49-0.

- ^ Gambhir, Surendra Kumar (1984). The East Indian speech community in Guyana: a sociolinguistic study with special reference to koine formation (Thesis). OCLC 654720956.[page needed]

- ^ Kuno 1981[full citation needed]

- ^ Kidwai 2000[full citation needed]

- ^ Patil, Umesh; Kentner, Gerrit; Gollrad, Anja; Kügler, Frank; Fery, Caroline; Vasishth, Shravan (17 November 2008). «Focus, Word Order and Intonation in Hindi». Journal of South Asian Linguistics. 1.

- ^ Vasishth, Shravan (2004). «Discourse Context and Word Order Preferences in Hindi». The Yearbook of South Asian Languages and Linguistics (2004). pp. 113–128. doi:10.1515/9783110179897.113. ISBN 978-3-11-020776-7.

- ^ Spencer, Andrew (2005). «Case in Hindi». The Proceedings of the LFG ’05 Conference (PDF). pp. 429–446.

- ^ Scrivner, Olga (June 2015). A Probabilistic Approach in Historical Linguistics. Word Order Change in Infinitival Clauses: from Latin to Old French (Thesis). p. 32. hdl:2022/20230.

- ^ Spevak, Olga (2010). Constituent Order in Classical Latin Prose, p. 1, quoting Weil (1844).

- ^ Devine, Andrew M. & Laurence D. Stephens (2006), Latin Word Order, p. 79.

- ^ Walker, Arthur T. (1918). «Some Facts of Latin Word-Order». The Classical Journal. 13 (9): 644–657. JSTOR 3288352.

- ^ Taylor, Ann; Pintzuk, Susan (1 December 2011). «The interaction of syntactic change and information status effects in the change from OV to VO in English». Catalan Journal of Linguistics. 10: 71. doi:10.5565/rev/catjl.61.

- ^ Trips, Carola (2002). From OV to VO in Early Middle English. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today. Vol. 60. doi:10.1075/la.60. ISBN 978-90-272-2781-2.

- ^ Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616, author. (4 February 2020). Henry V. ISBN 978-1-9821-0941-7. OCLC 1105937654. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1941). Much Ado about Nothing. Boston, USA: Ginn and Company. pp. 12, 16.

- ^ Crystal, David (2012). Think on my Words: Exploring Shakespeare’s Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-139-19699-4.

- ^ Loprieno, Antonio (2000). «From VSO to SVO? Word Order and Rear Extraposition in Coptic». Stability, Variation and Change of Word-Order Patterns over Time. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 213. pp. 23–39. doi:10.1075/cilt.213.05lop. ISBN 978-90-272-3720-0.

- ^ «Spanish». The Romance Languages. 2003. pp. 91–142. doi:10.4324/9780203426531-7. ISBN 978-0-203-42653-1.

- ^ Klee, Carol A.; Tight, Daniel G.; Caravedo, Rocio (1 December 2011). «Variation and change in Peruvian Spanish word order: language contact and dialect contact in Lima». Southwest Journal of Linguistics. 30 (2): 5–32. Gale A348978474.

Further reading[edit]

- A collection of papers on word order by a leading scholar, some downloadable

- Basic word order in English clearly illustrated with examples.

- Bernard Comrie, Language Universals and Linguistic Typology: Syntax and Morphology (1981) – this is the authoritative introduction to word order and related subjects.

- Order of Subject, Object, and Verb (PDF). A basic overview of word order variations across languages.

- Haugan, Jens, Old Norse Word Order and Information Structure. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. 2001. ISBN 82-471-5060-3

- Rijkhoff, Jan (2015). «Word Order». International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (PDF). pp. 644–656. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.53031-1. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5.

- Song, Jae Jung (2012), Word Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87214-0 & ISBN 978-0-521-69312-7

100

Subject + Verb + Object

100

Subject + BE + Past Participle isn’t the word order of passive voice.

200

Prepositions combined with verbs must be considered as __________ (one unit/two units).

one unit

200

Prepositional phrases can be at either the beginning or the end of the sentence.

300

Complete the sentence order: Subject + BE + __________ (Preposition/Preposition phrase).

Preposition phrase (by chance, at the front of, etc.)

300

Nouns + preposition is the correct word combination.

400

Choose the correct position of adverbs of frequency:

Before BE

or

After BE

After BE

400

Adverbs of frequency are before auxiliary verbs.

500

Choose the correct word combination.

Verb + preposition / Adverb + preposition

Verb + preposition

500

Putting a negative adverb of frequency in front of the subject makes your writing more informal.

Click to zoom

Normally, sentences in the English language take a simple form. However, there are times it would be a little complex. In these cases, the basic rules for how words appear in a sentence can help you.

Word order typically refers to the way the words in a sentence are arranged. In the English language, the order of words is important if you wish to accurately and effectively communicate your thoughts and ideas.

Although there are some exceptions to these rules, this article aims to outline some basic sentence structures that can be used as templates. Also, the article provides the rules for the ordering of adverbs and adjectives in English sentences.

Basic Sentence Structure and word order rules in English

For English sentences, the simple rule of thumb is that the subject should always come before the verb followed by the object. This rule is usually referred to as the SVO word order, and then most sentences must conform to this. However, it is essential to know that this rule only applies to sentences that have a subject, verb, and object.

For example

Subject + Verb + Object

He loves food

She killed the rat

Sentences are usually made of at least one clause. A clause is a string of words with a subject(noun) and a predicate (verb). A sentence with just one clause is referred to as a simple sentence, while those with more than one clause are referred to as compound sentences, complex sentences, or compound-complex sentences.

The following is an explanation and example of the most commonly used clause patterns in the English language.

Inversion

Inversion

The English word order is inverted in questions. The subject changes its place in a question. Also, English questions usually begin with a verb or a helping verb if the verb is complex.

For example

Verb + Subject + object

Can you finish the assignment?

Did you go to work?

Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive Verbs

Some sentences use verbs that require no object or nothing else to follow them. These verbs are generally referred to as intransitive verbs. With intransitive verbs, you can form the most basic sentences since all that is required is a subject (made of one noun) and a predicate (made of one verb).

For example

Subject + verb

John eats

Christine fights

Linking Verbs

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs are verbs that connect a subject to the quality of the subject. Sentences that use linking verbs usually contain a subject, the linking verb and a subject complement or predicate adjective in this order.

For example

Subject + verb + Subject complement/Predicate adjective

The dress was beautiful

Her voice was amazing

Transitive Verbs

Transitive Verbs

Transitive verbs are verbs that tell what the subject did to something else. Sentences that use transitive verbs usually contain a subject, the transitive verb, and a direct object, usually in this order.

For example

Subject + Verb + Direct object

The father slapped his son

The teacher questioned his students

Indirect Objects

Indirect Objects

Sentences with transitive verbs can have a mixture of direct and indirect objects. Indirect objects are usually the receiver of the action or the audience of the direct object.

For example

Subject + Verb + IndirectObject + DirectObject

He gave the man a good job.

The singer gave the crowd a spectacular concert.

The order of direct and indirect objects can also be reversed. However, for the reversal of the order, there needs to be the inclusion of the preposition “to” before the indirect object. The addition of the preposition transforms the indirect object into what is called a prepositional phrase.

For example

Subject + Verb + DirectObject + Preposition + IndirectObject

He gave a lot of money to the man

The singer gave a spectacular concert to the crowd.

Adverbials

Adverbials

Adverbs are phrases or words that modify or qualify a verb, adjective, or other adverbs. They typically provide information on the when, where, how, and why of an action. Adverbs are usually very difficult to place as they can be in different positions in a sentence. Changing the placement of an adverb in a sentence can change the meaning or emphasis of that sentence.

Therefore, adverbials should be placed as close as possible to the things they modify, generally before the verbs.

For example

He hastily went to work.

He hurriedly ate his food.

However, if the verb is transitive, then the adverb should come after the transitive verb.

For example

John sat uncomfortably in the examination exam.

She spoke quietly in the class

The adverb of place is usually placed before the adverb of time

For example

John goes to work every morning

They arrived at school very late

The adverb of time can also be placed at the beginning of a sentence

For example

On Sunday he is traveling home

Every evening James jogs around the block

When there is more than one verb in the sentence, the adverb should be placed after the first verb.

For example

Peter will never forget his first dog

She has always loved eating rice.

Adjectives

Adjectives

Adjectives commonly refer to words that are used to describe someone or something. Adjectives can appear almost anywhere in the sentence.

Adjectives can sometimes appear after the verb to be

For example

He is fat

She is big

Adjectives can also appear before a noun.

For example

A big house

A fat boy

However, some sentences can contain more than one adjective to describe something or someone. These adjectives have an order in which they can appear before a now. The order is

Opinion – size – physical quality – shape – condition – age – color – pattern – origin – material – type – purpose

If more than one adjective is expected to come before a noun in a sentence, then it should follow this order. This order feels intuitive for native English speakers. However, it can be a little difficult to unpack for non-native English speakers.

For example

The ugly old woman is back

The dirty red car parked outside your house

When more than one adjective comes after a verb, it is usually connected by and

For example

The room is dark and cold

Having said that, Susan is tall and big

Get an expert to perfect your paper

Подборка по базе: Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (3).docx, Документ Microsoft Word (2).docx, Microsoft Word Document.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx, Документ Microsoft Word.docx

Семинар 6 Combinability. Word Groups

KEY TERMS

Syntagmatics — linear (simultaneous) relationship of words in speech as distinct from associative (non-simultaneous) relationship of words in language (paradigmatics). Syntagmatic relations specify the combination of elements into complex forms and sentences.

Distribution — The set of elements with which an item can cooccur

Combinability — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

Valency — the potential ability of words to occur with other words

Context — the semantically complete passage of written speech sufficient to establish the meaning of a given word (phrase).

Clichе´ — an overused expression that is considered trite, boring

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Collocation — such a combination of words which conditions the realization of a certain meaning

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION AND EXERCISES

1. Syntagmatic relations and the concept of combinability of words. Define combinability.

Syntagmatic relation defines the relationship between words that co-occur in the same sentence. It focuses on two main parts: how the position and the word order affect the meaning of a sentence.

The syntagmatic relation explains:

• The word position and order.

• The relationship between words gives a particular meaning to the sentence.

The syntagmatic relation can also explain why specific words are often paired together (collocations)

Syntagmatic relations are linear relations between words

The adjective yellow:

1. color: a yellow dress;

2. envious, suspicious: a yellow look;

3. corrupt: the yellow press

TYPES OF SEMANTIC RELATIONS

Because syntagmatic relations have to do with the relationship between words, the syntagms can result in collocations and idioms.

Collocations

Collocations are word combinations that frequently occur together.

Some examples of collocations:

- Verb + noun: do homework, take a risk, catch a cold.

- Noun + noun: office hours, interest group, kitchen cabinet.

- Adjective + adverb: good enough, close together, crystal clear.

- Verb + preposition: protect from, angry at, advantage of.

- Adverb + verb: strongly suggest, deeply sorry, highly successful.

- Adjective + noun: handsome man, quick shower, fast food.

Idioms

Idioms are expressions that have a meaning other than their literal one.

Idioms are distinct from collocations:

- The word combination is not interchangeable (fixed expressions).

- The meaning of each component is not equal to the meaning of the idiom

It is difficult to find the meaning of an idiom based on the definition of the words alone. For example, red herring. If you define the idiom word by word, it means ‘red fish’, not ‘something that misleads’, which is the real meaning.

Because of this, idioms can’t be translated to or from another language because the word definition isn’t equivalent to the idiom interpretation.

Some examples of popular idioms:

- Break a leg.

- Miss the boat.

- Call it a day.

- It’s raining cats and dogs.

- Kill two birds with one stone.

Combinability (occurrence-range) — the ability of linguistic elements to combine in speech.

The combinability of words is as a rule determined by their meanings, not their forms. Therefore not every sequence of words may be regarded as a combination of words.

In the sentence Frankly, father, I have been a fool neither frankly, father nor father, I … are combinations of words since their meanings are detached and do not unite them, which is marked orally by intonation and often graphically by punctuation marks.

On the other hand, some words may be inserted between the components of a word-combination without breaking it.

Compare,

a) read books

b) read many books

c) read very many books.

In case (a) the combination read books is uninterrupted.In cases (b) and (c) it is interrupted, or discontinuous(read… books).

The combinability of words depends on their lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical meanings. It is owing to the lexical meanings of the corresponding lexemes that the word wise can be combined with the words man, act, saying and is hardly combinable with the words milk, area, outline.

The lexico-grammatical meanings of -er in singer (a noun) and -ly in beautifully (an adverb) do not go together and prevent these words from forming a combination, whereas beautiful singer and sing beautifully are regular word-combinations.

The combination * students sings is impossible owing to the grammatical meanings of the corresponding grammemes.

Thus one may speak of lexical, grammatical and lexico-grammatical combinability, or the combinability of lexemes, grammemes and parts of speech.

The mechanism of combinability is very complicated. One has to take into consideration not only the combinability of homogeneous units, e. g. the words of one lexeme with those of another lexeme. A lexeme is often not combinable with a whole class of lexemes or with certain grammemes.

For instance, the lexeme few, fewer, fewest is not combinable with a class of nouns called uncountables, such as milk, information, hatred, etc., or with members of ‘singular’ grammemes (i. e. grammemes containing the meaning of ‘singularity’, such as book, table, man, boy, etc.).

The ‘possessive case’ grammemes are rarely combined with verbs, barring the gerund. Some words are regularly combined with sentences, others are not.

It is convenient to distinguish right-hand and left-hand connections. In the combination my hand (when written down) the word my has a right-hand connection with the word hand and the latter has a left-hand connection with the word my.

With analytical forms inside and outside connections are also possible. In the combination has often written the verb has an inside connection with the adverb and the latter has an outside connection with the verb.

It will also be expedient to distinguish unilateral, bilateral and multilateral connections. By way of illustration we may say that the articles in English have unilateral right-hand connections with nouns: a book, the child. Such linking words as prepositions, conjunctions, link-verbs, and modal verbs are characterized by bilateral connections: love of life, John and Mary, this is John, he must come. Most verbs may have zero

(Come!), unilateral (birds fly), bilateral (I saw him) and multilateral (Yesterday I saw him there) connections. In other words, the combinability of verbs is variable.

One should also distinguish direct and indirect connections. In the combination Look at John the connection between look and at, between at and John are direct, whereas the connection between look and John is indirect, through the preposition at.

2. Lexical and grammatical valency. Valency and collocability. Relationships between valency and collocability. Distribution.

The appearance of words in a certain syntagmatic succession with particular logical, semantic, morphological and syntactic relations is called collocability or valency.

Valency is viewed as an aptness or potential of a word to have relations with other words in language. Valency can be grammatical and lexical.

Collocability is an actual use of words in particular word-groups in communication.

The range of the Lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs ‘lift’ and ‘raise’ are synonyms, only ‘to raise’ is collocated with the noun ‘question’.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf. English ‘pot plants’ vs. Russian ‘комнатные цветы’.

The interrelation of lexical valency and polysemy:

• the restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups, e.g. heavy, adj. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc., but one cannot say *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage;

• different meanings of a word may be described through its lexical valency, e.g. the different meanings of heavy, adj. may be described through the word-groups heavy weight / book / table; heavy snow / storm / rain; heavy drinker / eater; heavy sleep / disappointment / sorrow; heavy industry / tanks, and so on.

From this point of view word-groups may be regarded as the characteristic minimal lexical sets that operate as distinguishing clues for each of the multiple meanings of the word.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. Its range is delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to. This is not to imply that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is necessarily identical, e.g.:

• the verbs suggest and propose can be followed by a noun (to propose or suggest a plan / a resolution); however, it is only propose that can be followed by the infinitive of a verb (to propose to do smth.);

• the adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: Adj. + Prep. at +Noun(clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

• The individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its grammatical valency, e.g. keen + Nas in keen sight ‘sharp’; keen + on + Nas in keen on sports ‘fond of’; keen + V(inf)as in keen to know ‘eager’.

Lexical context determines lexically bound meaning; collocations with the polysemantic words are of primary importance, e.g. a dramatic change / increase / fall / improvement; dramatic events / scenery; dramatic society; a dramatic gesture.

In grammatical context the grammatical (syntactic) structure of the context serves to determine the meanings of a polysemantic word, e.g. 1) She will make a good teacher. 2) She will make some tea. 3) She will make him obey.

Distribution is understood as the whole complex of contexts in which the given lexical unit(word) can be used. Есть даже словари, по которым можно найти валентные слова для нужного нам слова — так и называются дистрибьюшн дикшенери

3. What is a word combination? Types of word combinations. Classifications of word-groups.

Word combination — a combination of two or more notional words serving to express one concept. It is produced, not reproduced in speech.

Types of word combinations:

- Semantically:

- free word groups (collocations) — a year ago, a girl of beauty, take lessons;

- set expressions (at last, point of view, take part).

- Morphologically (L.S. Barkhudarov):

- noun word combinations, e.g.: nice apples (BBC London Course);

- verb word combinations, e.g.: saw him (E. Blyton);

- adjective word combinations, e.g.: perfectly delightful (O. Wilde);

- adverb word combinations, e.g.: perfectly well (O, Wilde);

- pronoun word combinations, e.g.: something nice (BBC London Course).

- According to the number of the components:

- simple — the head and an adjunct, e.g.: told me (A. Ayckbourn)

- Complex, e.g.: terribly cold weather (O. Jespersen), where the adjunct cold is expanded by means of terribly.

Classifications of word-groups:

- through the order and arrangement of the components:

• a verbal — nominal group (to sew a dress);

• a verbal — prepositional — nominal group (look at something);

- by the criterion of distribution, which is the sum of contexts of the language unit usage:

• endocentric, i.e. having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky);

• exocentric, i.e. having no central member (become older, side by side);

- according to the headword:

• nominal (beautiful garden);

• verbal (to fly high);

• adjectival (lucky from birth);

- according to the syntactic pattern:

• predicative (Russian linguists do not consider them to be word-groups);

• non-predicative — according to the type of syntactic relations between the components:

(a) subordinative (modern technology);

(b) coordinative (husband and wife).

4. What is “a free word combination”? To what extent is what we call a free word combination actually free? What are the restrictions imposed on it?

A free word combination is a combination in which any element can be substituted by another.

The general meaning of an ordinary free word combination is derived from the conjoined meanings of its elements

Ex. To come to one’s sense –to change one’s mind;

To fall into a rage – to get angry.

Free word-combinations are word-groups that have a greater semantic and structural independence and freely composed by the speaker in his speech according to his purpose.

A free word combination or a free phrase permits substitution of any of its elements without any semantic change in the other components.

5. Clichе´s (traditional word combinations).

A cliché is an expression that is trite, worn-out, and overused. As a result, clichés have lost their original vitality, freshness, and significance in expressing meaning. A cliché is a phrase or idea that has become a “universal” device to describe abstract concepts such as time (Better Late Than Never), anger (madder than a wet hen), love (love is blind), and even hope (Tomorrow is Another Day). However, such expressions are too commonplace and unoriginal to leave any significant impression.

Of course, any expression that has become a cliché was original and innovative at one time. However, overuse of such an expression results in a loss of novelty, significance, and even original meaning. For example, the proverbial phrase “when it rains it pours” indicates the idea that difficult or inconvenient circumstances closely follow each other or take place all at the same time. This phrase originally referred to a weather pattern in which a dry spell would be followed by heavy, prolonged rain. However, the original meaning is distanced from the overuse of the phrase, making it a cliché.

Some common examples of cliché in everyday speech:

- My dog is dumb as a doorknob. (тупой как пробка)

- The laundry came out as fresh as a daisy.

- If you hide the toy it will be out of sight, out of mind. (с глаз долой, из сердца вон)

Examples of Movie Lines that Have Become Cliché:

- Luke, I am your father. (Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back)

- i am Groot. (Guardians of the Galaxy)

- I’ll be back. (The Terminator)

- Houston, we have a problem. (Apollo 13)

Some famous examples of cliché in creative writing:

- It was a dark and stormy night

- Once upon a time

- There I was

- All’s well that ends well

- They lived happily ever after

6. The sociolinguistic aspect of word combinations.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexicosemantic connections of a word with other word

Some researchers suggested that the functioning of a word in speech is determined by the environment in which it occurs, by its grammatical peculiarities (part of speech it belongs to, categories, functions in the sentence, etc.), and by the type and character of meaning included into the semantic structure of a word.

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combinations with other words. The words that surround a particular word in a sentence or paragraph are called the verbal context of that word.

7. Norms of lexical valency and collocability in different languages.

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical. This is only natural since every language has its syntagmatic norms and patterns of lexical valency. Words, habitually collocated, tend to constitute a cliché, e.g. bad mistake, high hopes, heavy sea (rain, snow), etc. The translator is obliged to seek similar cliches, traditional collocations in the target-language: грубая ошибка, большие надежды, бурное море, сильный дождь /снег/.

The key word in such collocations is usually preserved but the collocated one is rendered by a word of a somewhat different referential meaning in accordance with the valency norms of the target-language:

- trains run — поезда ходят;

- a fly stands on the ceiling — на потолке сидит муха;

- It was the worst earthquake on the African continent (D.W.) — Это было самое сильное землетрясение в Африке.

- Labour Party pretest followed sharply on the Tory deal with Spain (M.S.1973) — За сообщением о сделке консервативного правительства с Испанией немедленно последовал протест лейбористской партии.

Different collocability often calls for lexical and grammatical transformations in translation though each component of the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. the collocation «the most controversial Prime Minister» cannot be translated as «самый противоречивый премьер-министр».

«Britain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official visit one of the most controversial and youngest Prime Ministers in Europe» (The Times, 1970). «Завтра в Англию прибывает с официальным визитом один из самых молодых премьер-министров Европы, который вызывает самые противоречивые мнения».

«Sweden’s neutral faith ought not to be in doubt» (Ib.) «Верность Швеции нейтралитету не подлежит сомнению».

The collocation «documentary bombshell» is rather uncommon and individual, but evidently it does not violate English collocational patterns, while the corresponding Russian collocation — документальная бомба — impossible. Therefore its translation requires a number of transformations:

«A teacher who leaves a documentary bombshell lying around by negligence is as culpable as the top civil servant who leaves his classified secrets in a taxi» (The Daily Mirror, 1950) «Преподаватель, по небрежности оставивший на столе бумаги, которые могут вызвать большой скандал, не менее виновен, чем ответственный государственный служащий, забывший секретные документы в такси».

8. Using the data of various dictionaries compare the grammatical valency of the words worth and worthy; ensure, insure, assure; observance and observation; go and walk; influence and влияние; hold and держать.

| Worth & Worthy | |

| Worth is used to say that something has a value:

• Something that is worth a certain amount of money has that value; • Something that is worth doing or worth an effort, a visit, etc. is so attractive or rewarding that the effort etc. should be made. Valency:

|

Worthy:

• If someone or something is worthv of something, they deserve it because they have the qualities required; • If you say that a person is worthy of another person you are saying that you approve of them as a partner for that person. Valency:

|

| Ensure, insure, assure | ||

| Ensure means ‘make certain that something happens’.

Valency:

|

Insure — make sure

Valency:

|

Assure:

• to tell someone confidently that something is true, especially so that they do not worry; • to cause something to be certain. Valency:

|

| Observance & Observation | |

| Observance:

• the act of obeying a law or following a religious custom: religious observances such as fasting • a ceremony or action to celebrate a holiday or a religious or other important event: [ C ] Memorial Day observances [ U ] Financial markets will be closed Monday in observance of Labor Day. |

Observation:

• the act of observing something or someone; • the fact that you notice or see something; • a remark about something that you have noticed. Valency:

|

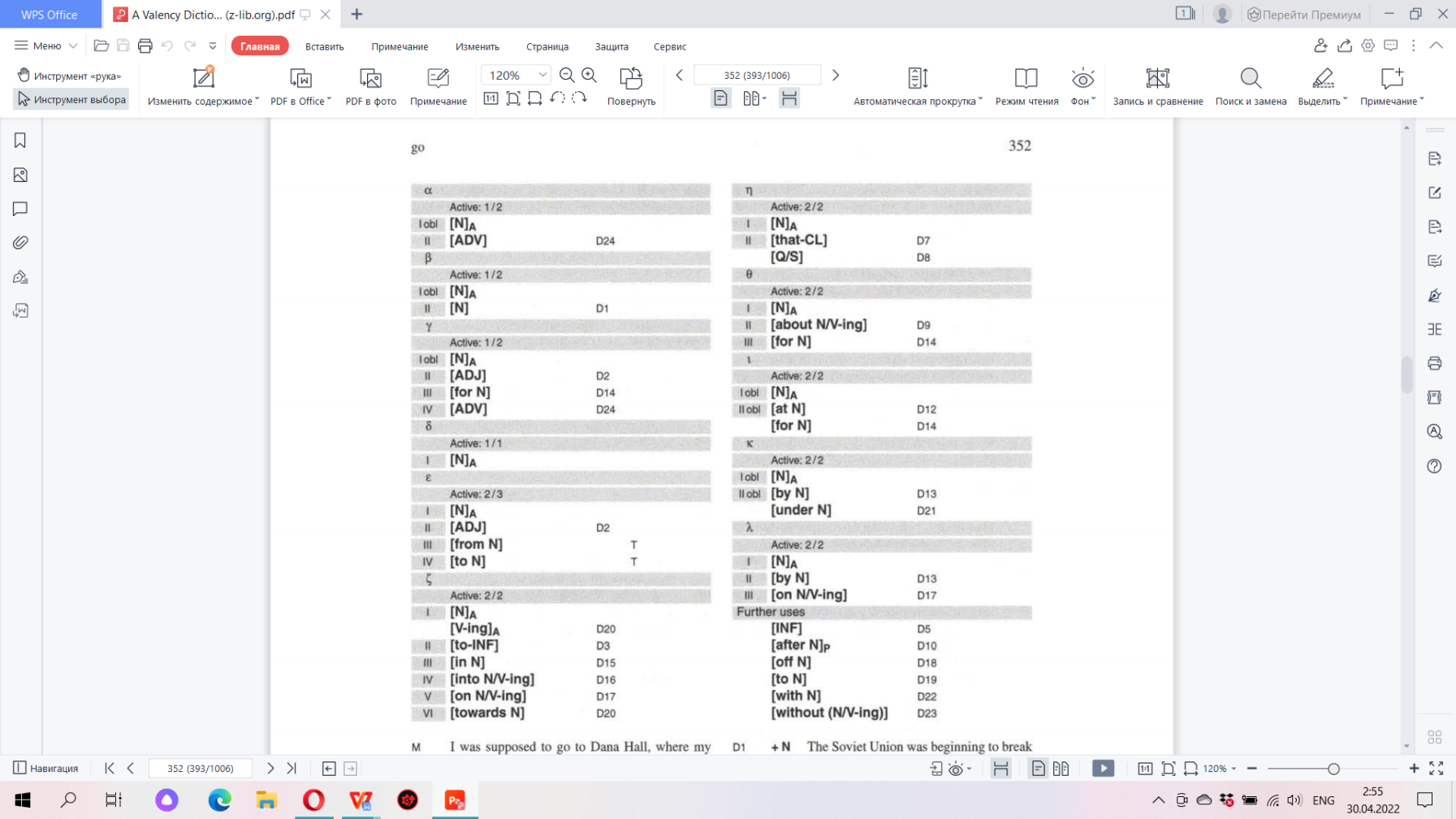

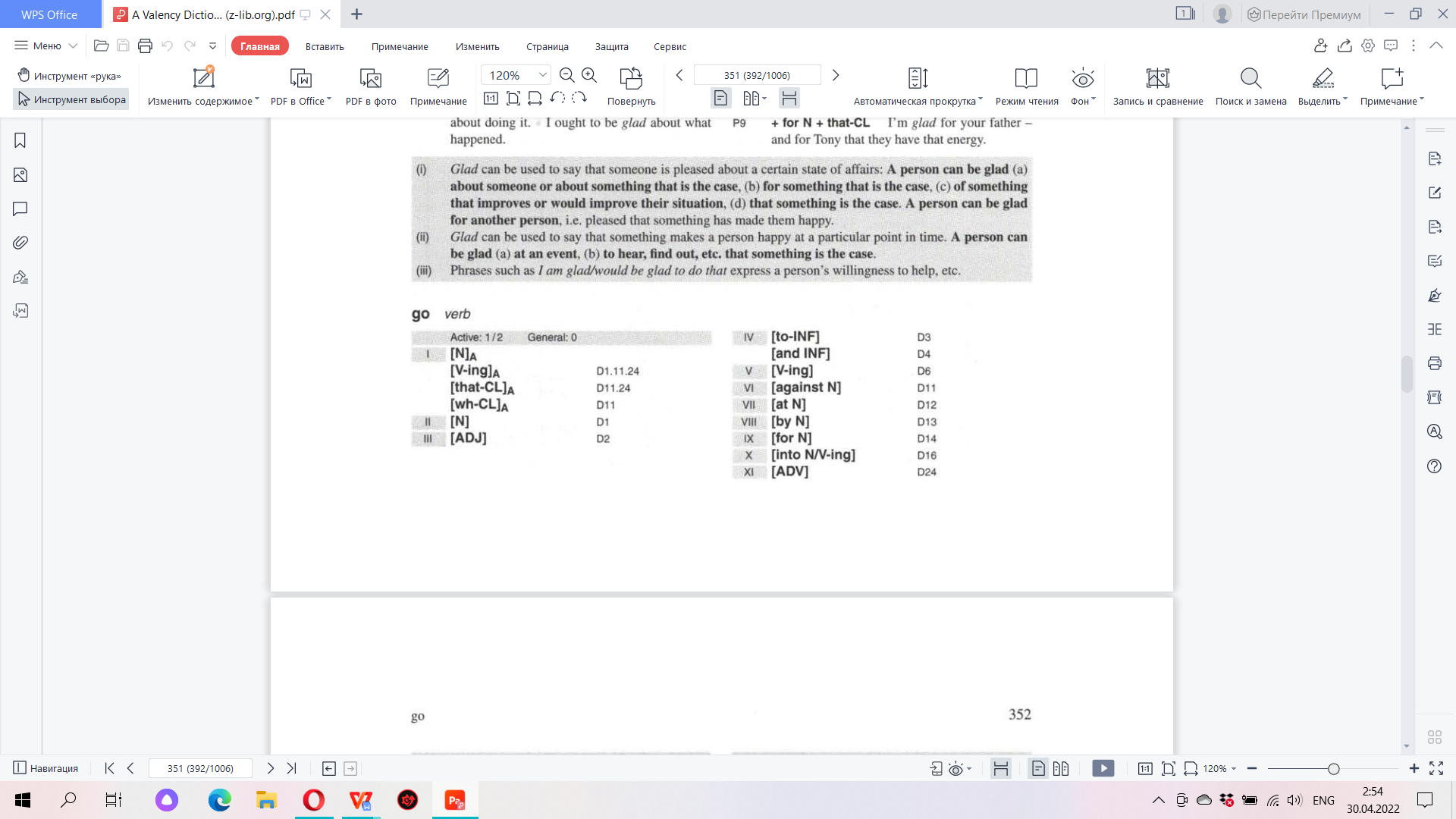

| Go & Walk | |

|

Walk can mean ‘move along on foot’:

• A person can walk an animal, i.e. exercise them by walking. • A person can walk another person somewhere , i.e. take them there, • A person can walk a particular distance or walk the streets. Valency:

|

| Influence & Влияние | |

| Influence:

• A person can have influence (a) over another person or a group, i.e. be able to directly guide the way they behave, (b) with a person, i.e. be able to influence them because they know them well. • Someone or something can have or be an influence on or upon something or someone, i.e. be able to affect their character or behaviour in some way Valency:

|

Влияние — Действие, оказываемое кем-, чем-либо на кого-, что-либо.

Сочетаемость:

|

| Hold & Держать | |

| Hold:

• to take and keep something in your hand or arms; • to support something; • to contain or be able to contain something; • to keep someone in a place so that they cannot leave. Valency:

|

Держать — взять в руки/рот/зубы и т.д. и не давать выпасть

Сочетаемость:

|

- Contrastive Analysis. Give words of the same root in Russian; compare their valency:

| Chance | Шанс |

|

|

| Situation | Ситуация |

|

|

| Partner | Партнёр |

|

|

| Surprise | Сюрприз |

|

|

| Risk | Риск |

|

|

| Instruction | Инструкция |

|

|

| Satisfaction | Сатисфакция |

|

|

| Business | Бизнес |

|

|

| Manager | Менеджер |

|

|

| Challenge | Челлендж |

|

|

10. From the lexemes in brackets choose the correct one to go with each of the synonyms given below:

- acute, keen, sharp (knife, mind, sight):

• acute mind;

• keen sight;

• sharp knife;

- abysmal, deep, profound (ignorance, river, sleep);

• abysmal ignorance;

• deep river;

• profound sleep;

- unconditional, unqualified (success, surrender):

• unconditional surrender;

• unqualified success;

- diminutive, miniature, petite, petty, small, tiny (camera, house, speck, spite, suffix, woman):

• diminutive suffix;

• miniature camera/house;

• petite woman;

• petty spite;

• small speck/camera/house;

• tiny house/camera/speck;

- brisk, nimble, quick, swift (mind, revenge, train, walk):

• brisk walk;

• nimble mind;

• quick train;

• swift revenge.

11. Collocate deletion: One word in each group does not make a strong word partnership with the word on Capitals. Which one is Odd One Out?

1) BRIGHT idea green

smell

child day room

2) CLEAR

attitude

need instruction alternative day conscience

3) LIGHT traffic

work

day entertainment suitcase rain green lunch

4) NEW experience job

food

potatoes baby situation year

5) HIGH season price opinion spirits

house

time priority

6) MAIN point reason effect entrance

speed

road meal course

7) STRONG possibility doubt smell influence

views

coffee language

advantage

situation relationship illness crime matter

- Write a short definition based on the clues you find in context for the italicized words in the sentence. Check your definitions with the dictionary.

| Sentence | Meaning |

| The method of reasoning from the particular to the general — the inductive method — has played an important role in science since the time of Francis Bacon. | The way of learning or investigating from the particular to the general that played an important role in the time of Francis Bacon |

| Most snakes are meat eaters, or carnivores. | Animals whose main diet is meat |

| A person on a reducing diet is expected to eschew most fatty or greasy foods. | deliberately avoid |

| After a hectic year in the city, he was glad to return to the peace and quiet of the country. | full of incessant or frantic activity. |

| Darius was speaking so quickly and waving his arms around so wildly, it was impossible to comprehend what he was trying to say. | grasp mentally; understand.to perceive |

| The babysitter tried rocking, feeding, chanting, and burping the crying baby, but nothing would appease him. | to calm down someone |

| It behooves young ladies and gentlemen not to use bad language unless they are very, very angry. | necessary |

| The Academy Award is an honor coveted by most Hollywood actors. | The dream about some achievements |

| In the George Orwell book 1984, the people’s lives are ruled by an omnipotent dictator named “Big Brother.” | The person who have a lot of power |

| After a good deal of coaxing, the father finally acceded to his children’s request. | to Agree with some request |

| He is devoid of human feelings. | Someone have the lack of something |

| This year, my garden yielded several baskets full of tomatoes. | produce or provide |

| It is important for a teacher to develop a rapport with his or her students. | good relationship |

Compounding

or word-composition

is

one

of the major and highly productive types of word-formation, one of

the potent means of replenishment of English word-stock. This type of

word formation was very productive in Old English and it hasn’t

lost its productivity till present time. More than one third of all

the new words in modern English are compound words. Compound words as

the term itself suggests are lexical units of complex structure.

Many

definitions offered by linguists (А.I.Smirnitsky, I.V.Аrnold,

О.D.Меshkov, H.Маrchаnd, О.Jesрersеn, R.V.Zаndvоrt) соme

to the following one: a

compound word is a lexical unit formed by joining together two or

more derivational bases and singled out in speech due to its

integrity.

The

derivational bases may be of different degrees of complexity as, e.g.

arm-chair,

prizefighter, fancy-dress-maker, forget-me-not, merry-go-round,

pay-as-you-earn,

etc. Notwithstanding the fact that many linguists devoted their

researches to word-composition, still some of the issues concerning

this type of word formation are open to debate. One of the

difficulties is the problem of distinguishing compound words from

word combinations (word-groups, phrases). Comparing such compound

words as

running water

‘water coming from a mains supply – Rus. водопровод’

a

dancing—girl

‘a professional dancer – Rus. танцовщица’ with the

word combinations running

water

‘water that runs – Rus. проточная вода’ and

a dancing girl

‘a girl who is dancing – Rus. танцующая девушка’

and many others, it is difficult to determine whether we deal with

compound words or word combinations.

The

most important property of compound words is their integrity (see

section 1 of chapter I) which is understood as impossibility to

insert other units of the language (morphemes, words) between the

components of a compound word. Integrity might be also considered

the basic criterion of distinguishing compound words from word

combinations and other language units. Compound words possess both

structural and semantic integrity.

Structural

integrity of compound words manifests itself in the fixed

order of

their components. The second IC (Immediate Constituent) is in

overwhelming majority of compound words the structural and semantic

centre, the onomasiological basis of the word. In compound words like

a

house-dog

and a

dog-house

and many others, it is the second component that determines the part

of speech, i.e. lexico-grammatical properties of the compound, and

its referent, or what actually the word denotes, while the first

component modifies the meaning of the second one:

a house-dog

– a

dog

trained to guard a house; a

dog-house

– a

house

for a dog.

For

some types of compound words the indication of integrity is the

reverse order of the components as compared with word combinations.

It is the case of the compounds with the second components expressed

by adjectives and participles, e.g.

oil-rich, man-made.

In the synonymous word combinations the word order is: rich

in oil, made by man.

There

are other criteria employed for distinguishing compound words from

word combinations taking into account various aspects of compound

words. The phonetic

(phonic) criterion rests

on the marked tendency in English to give compounds a heavy stress on

the first component. It is true that compound words in many cases are

given single, or the so-called unity stress; or two stresses – a

primary and a secondary one. Such stress patterns differ from the

stress patterns of word combinations where each notional word is

stressed. For instance, each of the words road

and

house

is stressed in a word combination, e.g. a

`house

by the `road

but when they make up a compound word a `roadhouse ‘a building on a

main road’ the stress pattern is changed, the word acquires a unity

stress on the first component or double stress (the primary and

secondary ones) as in the words `blood-vessel,

`washing-maֽِchine.

The phonic criterion will prove that `laughing

`boys

‘the boys who are laughing’ is a word combination (word group)

but `laughing-gas

‘gas used in dental surgery’ is a compound word. However, not

infrequent are the cases with the so-called level stress when each

component is equally stressed: `arm-`chair,

`snow-`white,

`icy-`cold.

Hence, the phonic criterion is not quite reliable.

The

structural integrity of a compound word differing from structural

separateness of a word combination is backed up by the morphological

(morphemic)

criterion.

A

sequence of components making up a

compound

word is a morphemic unity and it has a single paradigm. It means that

the grammatical inflections are added to the word as a whole but not

to its separate parts, e.g. earthquake

– earthquakes,

weekend – weekends.

In a word combination each of the component parts is morphemically

independent and may attract the grammatical inflections (сf.

age-long

and ages

ago).

This criterion, however, is limited for the English language because

of the scarcity of its grammatical morphemic means.

To

the syntactic

criterion

besides the above-mentioned fixed order of the components refers the

character of

syntactic

relations. The components of compound words cannot enter into the

syntactic

relations

of their own. Thus in the word combination (a

factory)

financed

by the government

each notional word may be modified by an attribute: a

factory generously

financed by the British

government

(the example is borrowed from [Мешков 1976: 182]). None of the

components of a compound word can be modified by an attribute:

*generously

government-financed.

Modifying a component of a compound word is only possible by

introducing one more component into the structure of a compound word:

Labour-government-financed.

However, syntactic parameters do not unambiguously solve the problem

of distinguishing a compound word from a word combination because the

collocability of the components of word combinations may be limited.

The

semantic

criterion presupposes

the semantic integrity of a compound word, close semantic links

between its components. According to this criterion the following

examples refer to compound words: daybreak,

blackmail,

killjoy

and

many others. But the semantic criterion seems to be the most

unreliable one as it is not always possible to objectively determine

to what extent the components are semantically linked together.

Besides it is impossible to draw a line between compound words and

phraseological units, idioms which are characterized by semantic

unity.

As

one more criterion of structural integrity of compound words might be

named the graphic

criterion.

The majority of compound words are spelled either solidly or with a

hyphen. But there is no consistency in English spelling in this

respect. The same words may be spelt either solidly, with a hyphen or

with a break. The spelling varies with different texts and even

dictionaries (e.g. airline,

air-line, air line).

There is statistic data concerning the variability of spelling, e.g.

complexes with the first components well-,

ill—

(e.g. ill-advised,

ill-affected,

well-dressed,

well-aimed)

in 34 % cases are spelt with a break, in 66% with a hyphen

[Харитончик 1992: 180]. The vacillations in spelling are

most frequent in ‘n + n’ pattern: war(-)time,

money(-)order, post(-)card,

etc. E. Pаrtridge in his book “Usage and Abusage” writes that a

compound word goes through three stages in its evolution: (1) two

separate words (cat

bird);

(2) a compound word spelt with a hyphen (cat-bird);

(3) a solidly spelt word (catbird).

Thus, solid spelling of compounds is manifestation of language

consciousness, the moment when the lexical unit is perceived as

having acquired a semantic unity. Solid or hyphenated spellings are

indications of compound words, although cases of a break between

components allow of various interpretations.

So

far not a single criterion is reliable enough to identify compound

words. Moreover, even a combination of criteria is not sufficient

enough to unequivocally decide whether the lexical unit is a compound

word or a word combination.

The

second aspect of the issue of identification of compound words and

determining the types of word-formation is the problem of delineation

between compounding and other types of word-formation resulting in

appearance of compound words. Such words as long-legged,

three-cornered,

schoolmasterish

are complex in their morphological structure but according to the

type of word formation they refer to suffixal derivatives. Their

derivational patterns are as follows: long-legged

~ (long

+ leg)

+-ed

~ (a + n) + sf , but not long

+ legged,

as there is no such a derivational base as *legged.

By analogy: three-cornered