Subjects>Jobs & Education>Education

Wiki User

∙ 9y ago

Best Answer

Copy

English: «old» is German: «alt».

Wiki User

∙ 9y ago

This answer is:

Study guides

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is the German word for old?

Write your answer…

Submit

Still have questions?

Related questions

People also asked

| Old High German | |

|---|---|

| Region | Central Europe |

| Era | Early Middle Ages |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Writing system |

Runic, Latin |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | goh |

| ISO 639-3 | goh |

| Glottolog | oldh1241 |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Old High German (OHG; German: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 500/750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old High German is an umbrella term for the group of continental West Germanic dialects which underwent the set of consonantal changes called the Second Sound Shift.

At the start of this period, the main dialect areas belonged to largely independent tribal kingdoms, but by 788 the conquests of Charlemagne had brought all OHG dialect areas into a single polity. The period also saw the development of a stable linguistic border between German and Gallo-Romance, later French.

The surviving OHG texts were all written in monastic scriptoria and, as a result, the overwhelming majority of them are religious in nature or, when secular, belong to the Latinate literary culture of Christianity. The earliest written texts in Old High German, glosses and interlinear translations for Latin texts, appear in the latter half of the 8th century. The importance of the church in the production of texts and the extensive missionary activity of the period have left their mark on the OHG vocabulary, with many new loans and new coinages to represent the Latin vocabulary of the church.

OHG largely preserves the synthetic inflectional system inherited from its ancestral Germanic forms, but the end of the period is marked by sound changes which disrupt these patterns of inflection, leading to the more analytic grammar of Middle High German. In syntax, the most important change was the development of new periphrastic tenses to express the future and passive.

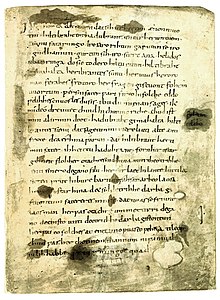

First page of the St. Gall Codex Abrogans (Stiftsbibliothek, cod. 911), the earliest text in Old High German

Periodisation[edit]

Old High German is generally dated, following Willhelm Scherer, from around 750 to around 1050.[1][2] The start of this period sees the beginning of the OHG written tradition, at first with only glosses, but with substantial translations and original compositions by the 9th century.[2] However the fact that the defining feature of Old High German, the Second Sound Shift, may have started as early as the 6th century and is complete by 750, means that some take the 6th century to be the start of the period.[a] Alternatively, terms such as Voralthochdeutsch («pre-OHG»)[3] or vorliterarisches Althochdeutsch («pre-literary OHG»)[4] are sometimes used for the period before 750.[b] Regardless of terminology, all recognize a distinction between a pre-literary period and the start of a continuous tradition of written texts around the middle of the 8th century.[5]

Differing approaches are taken, too, to the position of Langobardic. Langobardic is an Elbe Germanic and thus Upper German dialect, and it shows early evidence for the Second Sound Shift. For this reason, some scholars treat Langobardic as part of Old High German,[6] but with no surviving texts — just individual words and names in Latin texts — and the speakers starting to abandon the language by the 8th century,[7] others exclude Langobardic from discussion of OHG.[8] As Heidermanns observes, this exclusion is based solely on the external circumstances of preservation and not on the internal features of the language.[8]

The end of the period is less controversial. The sound changes reflected in spelling during the 11th century led to the remodelling of the entire system of noun and adjective declensions.[9] There is also a hundred-year «dearth of continuous texts» after the death of Notker Labeo in 1022.[5] The mid-11th century is widely accepted as marking the transition to Middle High German.[10]

Territory[edit]

The Old High German speaking area within the Holy Roman Empire in 962

Old High German comprises the dialects of these groups which underwent the Second Sound Shift during the 6th Century, namely all of Elbe Germanic and most of the Weser-Rhine Germanic dialects.

The Franks in the western part of Francia (Neustria and western Austrasia) gradually adopted Gallo-Romance by the beginning of the OHG period, with the linguistic boundary later stabilised approximately along the course of the Meuse and Moselle in the east, and the northern boundary probably a little further south than the current boundary between French and Dutch.[11] North of this line, the Franks retained their language, but it was not affected by the Second Sound Shift, which thus separated the Old Dutch varieties from the more easterly Franconian dialects which formed part of Old High German.[12]

In the south, the Lombards, who had settled in Northern Italy, maintained their dialect until their conquest by Charlemagne in 774. After this the Germanic-speaking population, who were by then almost certainly bilingual, gradually switched to the Romance language of the native population, so that Langobardic had died out by the end of the OHG period.[7]

At the beginning of the period, no Germanic language was spoken east of a line from Kieler Förde to the rivers Elbe and Saale, earlier Germanic speakers in the Northern part of the area having been displaced by the Slavs. This area did not become German-speaking until the German eastward expansion («Ostkolonisation») of the early 12th century, though there was some attempt at conquest and missionary work under the Ottonians.[13]

The Alemannic polity was conquered by Clovis I in 496, and in the last twenty years of the 8th century Charlemagne subdued the Saxons, the Frisians, the Bavarians, and the Lombards, bringing all continental Germanic-speaking peoples under Frankish rule. While this led to some degree of Frankish linguistic influence, the language of both the administration and the Church was Latin, and this unification did not therefore lead to any development of a supra-regional variety of Frankish nor a standardized Old High German; the individual dialects retained their identity.

Dialects[edit]

Map showing the main Old High German scriptoria and the areas of the Old High German «monastery dialects»

There was no standard or supra-regional variety of Old High German—every text is written in a particular dialect, or in some cases a mixture of dialects. Broadly speaking, the main dialect divisions of Old High German seem to have been similar to those of later periods—they are based on established territorial groupings and the effects of the Second Sound Shift, which have remained influential until the present day. But because the direct evidence for Old High German consists solely of manuscripts produced in a few major ecclesiastical centres, there is no isogloss information of the sort on which modern dialect maps are based. For this reason the dialects may be termed «monastery dialects» (German Klosterdialekte).[14]

The main dialects, with their bishoprics and monasteries:[15]

- Central German

- East Franconian: Fulda, Bamberg, Würzburg

- Middle Franconian: Trier, Echternach, Cologne

- Rhine Franconian: Lorsch, Speyer, Worms, Mainz, Frankfurt

- South Rhine Franconian: Wissembourg

- Upper German

- Alemannic: Murbach, Reichenau, Sankt Gallen, Strasbourg

- Bavarian: Freising, Passau, Regensburg, Augsburg, Ebersberg, Wessobrunn, Benediktbeuern, Tegernsee, Salzburg, Mondsee

In addition, there are two poorly attested dialects:

- Thuringian is attested only in four runic inscriptions and some possible glosses.[16]

- Langobardic was the dialect of the Lombards who invaded Northern Italy in the 6th century, and little evidence of it remains apart from names and individual words in Latin texts, and a few runic inscriptions. It declined after the conquest of the Lombard Kingdom by the Franks in 774. It is classified as Upper German on the basis of evidence of the Second Sound Shift.[17]

The continued existence of a West Frankish dialect in the Western, Romanized part of Francia is uncertain. Claims that this might have been the language of the Carolingian court or that it is attested in the Ludwigslied, whose presence in a French manuscript suggests bilingualism, are controversial.[15][16]

Literacy[edit]

Old High German literacy is a product of the monasteries, notably at St. Gallen, Reichenau Island and Fulda. Its origins lie in the establishment of the German church by Saint Boniface in the mid-8th century, and it was further encouraged during the Carolingian Renaissance in the 9th.

The dedication to the preservation of Old High German epic poetry among the scholars of the Carolingian Renaissance was significantly greater than could be suspected from the meagre survivals we have today (less than 200 lines in total between the Hildebrandslied and the Muspilli). Einhard tells how Charlemagne himself ordered that the epic lays should be collected for posterity.[18] It was the neglect or religious zeal of later generations that led to the loss of these records. Thus, it was Charlemagne’s weak successor, Louis the Pious, who destroyed his father’s collection of epic poetry on account of its pagan content.[19]

Rabanus Maurus, a student of Alcuin’s and abbot at Fulda from 822, was an important advocate of the cultivation of German literacy. Among his students were Walafrid Strabo and Otfrid of Weissenburg.

Towards the end of the Old High German period, Notker Labeo (d. 1022) was among the greatest stylists in the language, and developed a systematic orthography.[20]

Writing system[edit]

While there are a few runic inscriptions from the pre-OHG period,[21] all other OHG texts are written with the Latin alphabet, which, however, was ill-suited for representing some of the sounds of OHG. This led to considerable variations in spelling conventions, as individual scribes and scriptoria had to develop their own solutions to these problems.[22] Otfrid von Weissenburg, in one of the prefaces to his Evangelienbuch, offers comments on and examples of some of the issues which arise in adapting the Latin alphabet for German: «…sic etiam in multis dictis scriptio est propter litterarum aut congeriem aut incognitam sonoritatem difficilis.» («…so also, in many expressions, spelling is difficult because of the piling up of letters or their unfamiliar sound.»)[23] The careful orthographies of the OHG Isidor or Notker show a similar awareness.[22]

Phonology[edit]

The charts show the vowel and consonant systems of the East Franconian dialect in the 9th century. This is the dialect of the monastery of Fulda, and specifically of the Old High German Tatian. Dictionaries and grammars of OHG often use the spellings of the Tatian as a substitute for genuine standardised spellings, and these have the advantage of being recognizably close to the Middle High German forms of words, particularly with respect to the consonants.[24]

Vowels[edit]

Old High German had six phonemic short vowels and five phonemic long vowels. Both occurred in stressed and unstressed syllables. In addition, there were six diphthongs.[25]

| front | central | back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long |

| close | i | iː | u | uː | |

| mid | e, ɛ | eː | o | oː | |

| open | a | aː | |||

| Diphthongs | |||||

| ie | uo | ||||

| iu | io | ||||

| ei | ou |

Notes:

- Vowel length was indicated in the manuscripts inconsistently (though modern handbooks are consistent). Vowel letter doubling, a circumflex, or an acute accent was generally used to indicate a long vowel.[26]

- The short high and mid vowels may have been articulated lower than their long counterparts as in Modern German. This cannot be established from written sources.

- All back vowels likely had front-vowel allophones as a result of umlaut.[27] The front-vowel allophones likely became full phonemes in Middle High German. In the Old High German period, there existed [e] (possibly a mid-close vowel) from the umlaut of /a/ and /e/[clarification needed] but it probably was not phonemicized until the end of the period. Manuscripts occasionally distinguish two /e/ sounds. Generally, modern grammars and dictionaries use ⟨ë⟩ for the mid vowel and ⟨e⟩ for the mid-close vowel.

Reduction of unstressed vowels[edit]

By the mid 11th century the many different vowels found in unstressed syllables had almost all been reduced to ⟨e⟩ /ə/.[28]

Examples:

| Old High German | Middle High German | New High German | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| mahhôn | machen | machen | to make, do |

| taga | tage | Tage | days |

| demu | dem(e) | dem | to the |

(The New High German forms of these words are broadly the same as in Middle High German.)

Consonants[edit]

The main difference between Old High German and the West Germanic dialects from which it developed is that the former underwent the Second Sound Shift. The result of the sound change has been that the consonantal system of German is different from all other West Germanic languages, including English and Low German.

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal/Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | c, k /k/ g /ɡ/ | |||

| Affricate | pf /p͡f/ | z /t͡s/ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ng /ŋ/ | |||

| Fricative | f, v /f/ /v/ | th /θ/ | s, ȥ /s̠/, /s/ | h, ch /x/ | h | |

| Approximant | w, uu /w/ | j, i /j/ | ||||

| Liquid | r, l |

- There is wide variation in the consonant systems of the Old High German dialects, which arise mainly from the differing extent to which they are affected by the High German Sound Shift. Precise information about the articulation of consonants is impossible to establish.

- In the plosive and fricative series, if there are two consonants in a cell, the first is fortis and the second lenis. The voicing of lenis consonants varied between dialects.

- Old High German distinguished long and short consonants. Double-consonant spellings indicate not a preceding short vowel, as they do in Modern German, but true consonant gemination. Double consonants found in Old High German include pp, bb, tt, dd, ck (for /k:/), gg, ff, ss, hh, zz, mm, nn, ll, rr.

- /θ/ changes to /d/ in all dialects during the 9th century. The status in the Old High German Tatian (c. 830), as is reflected in modern Old High German dictionaries and glossaries, is that th is found in initial position and d in other positions.

- It is not clear whether Old High German /x/ had acquired a palatalized allophone [ç] after front vowels, as is the case in Modern German.

- A curly-tailed z (ȥ) is sometimes used in modern grammars and dictionaries to indicate the alveolar fricative that arose from Common Germanic t in the High German consonant shift. That distinguishes it from the alveolar affricate, which represented as z. The distinction has no counterpart in the original manuscripts, except in the Old High German Isidor, which uses tz for the affricate.

- The original Germanic fricative s was in writing usually clearly distinguished from the younger fricative z that evolved from the High German consonant shift. The sounds of both letters seem not to have merged before the 13th century. Since s later came to be pronounced /ʃ/ before other consonants (as in Stein /ʃtaɪn/, Speer /ʃpeːɐ/, Schmerz /ʃmɛrts/ (original smerz) or the southwestern pronunciation of words like Ast /aʃt/), it seems safe to assume that the actual pronunciation of Germanic s was somewhere between [s] and [ʃ], most likely about [s̠], in all Old High German until late Middle High German. A word like swaz, «whatever», would thus never have been [swas] but rather [s̠was], later (13th century) [ʃwas], [ʃvas].

Phonological developments[edit]

This list has the sound changes that transformed Common West Germanic into Old High German but not the Late OHG changes that affected Middle High German:

- /ɣ/, /β/ > /ɡ/, /b/ in all positions (/ð/ > /d/ already took place in West Germanic. Most but not all High German areas are subject to the change.

- PG *sibi «sieve» > OHG sib (cf. Old English sife), PG *gestra «yesterday» > OHG gestaron (cf. OE ġeostran, ġ being a fricative /ʝ/ )

- High German consonant shift: Inherited voiceless plosives are lenited into fricatives and affricates, and voiced fricatives are hardened into plosives and in some cases devoiced.

- Ungeminated post-vocalic /p/, /t/, /k/ spirantize intervocalically to /ff/, /ȥȥ/, /xx/ and elsewhere to /f/, /ȥ/, /x/. Cluster /tr/ is exempt. Compare Old English slǣpan to Old High German slāfan.

- Word-initially, after a resonant and when geminated, the same consonants affricatized to /pf/, /tȥ/ and /kx/, OE tam: OHG zam.

- Spread of /k/ > /kx/ is geographically very limited and is not reflected in Modern Standard German.

- /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ are devoiced.

- In Standard German, that applies to /d/ in all positions but to /b/ and /ɡ/ only when they are geminated. PG *brugjo > *bruggo > brucca, but *leugan > leggen.

- /eː/ (*ē²) and /oː/ are diphthongized into /ie/ and /uo/, respectively.

- Proto-Germanic /ai/ became /ei/ except before /r/, /h/, /w/ and word-finally, when it monophthongizes into ê, which is also the reflex of unstressed /ai/.

- Similarly, /au/ > /ô/ before /r/, /h/ and all dentals; otherwise, /au/ > /ou/. PG *dauþaz «death» > OHG tôd, but *haubudą «head» > houbit.

- /h/ refers there only to inherited /h/ from PIE *k, not to the result of the consonant shift /x/, which is sometimes written as h.

- Similarly, /au/ > /ô/ before /r/, /h/ and all dentals; otherwise, /au/ > /ou/. PG *dauþaz «death» > OHG tôd, but *haubudą «head» > houbit.

- /eu/ merges with /iu/ under i-umlaut and u-umlaut but elsewhere is /io/ (earlier /eo/). In Upper German varieties, it also becomes /iu/ before labials and velars.

- /θ/ fortifies to /d/ in all German dialects.

- Initial /w/ and /h/ before another consonant are dropped.

Morphology[edit]

Nouns[edit]

Verbs[edit]

Tense[edit]

Germanic had a simple two-tense system, with forms for a present and preterite. These were inherited by Old High German, but in addition OHG developed three periphrastic tenses: the perfect, pluperfect and future.

The periphrastic past tenses were formed by combining the present or preterite of an auxiliary verb (wësan, habēn) with the past participle. Initially the past participle retained its original function as an adjective and showed case and gender endings — for intransitive verbs the nominative, for transitive verbs the accusative.[29] For example:

After thie thö argangana warun ahtu taga (Tatian, 7,1)

«When eight days had passed», literally «After that then gone-by were eight days»

Latin: Et postquam consummati sunt dies octo (Luke 2:21)[30]phīgboum habeta sum giflanzotan (Tatian 102,2)

«There was a fig tree that some man had planted», literally «Fig-tree had certain (or someone) planted»Latin: arborem fici habebat quidam plantatam (Luke 13:6)[31][32]

In time, however, these endings fell out of use and the participle came to be seen no longer as an adjective but as part of the verb, as in Modern German. This development is taken to be arising from a need to render Medieval Latin forms,[33] but parallels in other Germanic languages (particularly Gothic, where the Biblical texts were translated from Greek, not Latin) raise the possibility that it was an independent development.[34][35]

Germanic also had no future tense, but again OHG created periphrastic forms, using an auxiliary verb skulan (Modern German sollen) and the infinitive, or werden and the present participle:

Thu scalt beran einan alawaltenden (Otfrid’s Evangelienbuch I, 5,23)

«You shall bear an almighty one»

Inti nu uuirdist thu suigenti’ (Tatian 2,9)

«And now you will start to fall silent»

Latin: Et ecce eris tacens (Luke 1:20)[36]

The present tense continued to be used alongside these new forms to indicate future time (as it still is in Modern German).

Conjugation[edit]

The following is a sample conjugation of a strong verb, nëman «to take».

| Indicative | Optative | Imperative | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | 1st sg | nimu | nëme | — |

| 2nd sg | nimis (-ist) | nëmēs (-ēst) | nim | |

| 3rd sg | nimit | nëme | — | |

| 1st pl | nëmemēs (-ēn) | nëmemēs (-ēn) | nëmamēs, -emēs (-ēn) | |

| 2nd pl | nëmet | nëmēt | nëmet | |

| 3rd pl | nëmant | nëmēn | — | |

| Past | 1st sg | nam | nāmi | — |

| 2nd sg | nāmi | nāmīs (-īst) | — | |

| 3rd sg | nam | nāmi | — | |

| 1st pl | nāmumēs (-un) | nāmīmēs (-īn) | — | |

| 2nd pl | nāmut | nāmīt | — | |

| 3rd pl | nāmun | nāmīn | — | |

| Gerund | Genitive | nëmannes | ||

| Dative | nëmanne | |||

| Participle | Present | nëmanti (-enti) | ||

| Past | ginoman |

Personal pronouns[37][edit]

| Number | Person | Gender | Nominative | Genitive | Dative | Accusative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | ih | mīn | mir | mih | |

| 2. | dū | dīn | dir | dih | ||

| 3. | Masculine | (h)er | (sīn) | imu, imo | inan, in | |

| Feminine | siu; sī, si | ira, iru | iro | sia | ||

| Neuter | iz | es, is | imu, imo | iz | ||

| Plural | 1. | wir | unsēr | uns | unsih | |

| 2. | ir | iuwēr | iu | iuwih | ||

| 3. | Masculine | sie | iro | im, in | sie | |

| Feminine | sio | iro | im, in | sio | ||

| Neuter | siu | iro | im, in | siu |

Syntax[edit]

Any description of OHG syntax faces a fundamental problem: texts translated from or based on a Latin original will be syntactically influenced by their source,[38] while the verse works may show patterns that are determined by the needs of rhyme and metre, or that represent literary archaisms.[39] Nonetheless, the basic word order rules are broadly those of Modern Standard German.[40]

Two differences from the modern language are the possibility of omitting a subject pronoun and lack of definite and indefinite articles. Both features are exemplified in the start of the 8th century Alemannic creed from St Gall:[41] kilaubu in got vater almahticun (Modern German, Ich glaube an Gott den allmächtigen Vater; English «I believe in God the almighty father»).[42]

By the end of the OHG period, however, use of a subject pronoun has become obligatory, while the definite article has developed from the original demonstrative pronoun (der, diu, daz)[43] and the numeral ein («one») has come into use as an indefinite article.[44] These developments are generally seen as mechanisms to compensate for the loss of morphological distinctions which resulted from the weakening of unstressed vowels in the endings of nouns and verbs (see above).[c][d]

Texts[edit]

The early part of the period saw considerable missionary activity, and by 800 the whole of the Frankish Empire had, in principle, been Christianized. All the manuscripts which contain Old High German texts were written in ecclesiastical scriptoria by scribes whose main task was writing in Latin rather than German. Consequently, the majority of Old High German texts are religious in nature and show strong influence of ecclesiastical Latin on the vocabulary. In fact, most surviving prose texts are translations of Latin originals. Even secular works such as the Hildebrandslied are often preserved only because they were written on spare sheets in religious codices.

The earliest Old High German text is generally taken to be the Abrogans, a Latin–Old High German glossary variously dated between 750 and 780, probably from Reichenau. The 8th century Merseburg Incantations are the only remnant of pre-Christian German literature. The earliest texts not dependent on Latin originals would seem to be the Hildebrandslied and the Wessobrunn Prayer, both recorded in manuscripts of the early 9th century, though the texts are assumed to derive from earlier copies.

The Bavarian Muspilli is the sole survivor of what must have been a vast oral tradition. Other important works are the Evangelienbuch (Gospel harmony) of Otfrid von Weissenburg, the short but splendid Ludwigslied and the 9th century Georgslied. The boundary to Early Middle High German (from c. 1050) is not clear-cut.

An example of Early Middle High German literature is the Annolied.

Example texts[edit]

The Lord’s Prayer is given in four Old High German dialects below. Because these are translations of a liturgical text, they are best not regarded as examples of idiomatic language, but they do show dialect variation very clearly.

| Latin version (From Tatian)[45] |

Alemannic, 8th century The St Gall Paternoster[46] |

South Rhine Franconian, 9th century Weissenburg Catechism[47] |

East Franconian, c. 830 Old High German Tatian[45] |

Bavarian, early 9th century Freisinger Paternoster[47] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pater noster, qui in caelis es, |

Fater unseer, thu pist in himile, |

Fater unsēr, thu in himilom bist, |

Fater unser, thū thār bist in himile, |

Fater unser, du pist in himilum. |

See also[edit]

- Old High German literature

- Middle High German

- Old High German declension

Notes[edit]

- ^ for example (Hutterer 1999, p. 307)

- ^ with tables showing the position taken in most of the standard works before 2000. (Roelcke 1998)

- ^ who discusses the problems with this view. (Salmons 2012, p. 162)

- ^ «but more indirectly that previously assumed.» (Fleischer & Schallert 2011, pp. 206–211)

Citations[edit]

- ^ Scherer 1878, p. 12.

- ^ a b Penzl 1986, p. 15.

- ^ Penzl 1986, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Wells 1987, p. 33.

- ^ Penzl 1986, p. 19.

- ^ a b Hutterer 1999, p. 338.

- ^ a b Braune & Heidermanns 2018, p. 7.

- ^ Wells 1987, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Roelcke 1998, pp. 804–811.

- ^ Wells 1987, p. 49.

- ^ Wells 1987, p. 43. Fn. 26

- ^ Peters 1985, p. 1211.

- ^ Wells 1987, pp. 44, 50–53.

- ^ a b Sonderegger 1980, p. 571.

- ^ a b Wells 1987, p. 432.

- ^ Hutterer 1999, pp. 336–341.

- ^ Vita Karoli Magni, 29: «He also had the old rude songs that celebrate the deeds and wars of the ancient kings written out for transmission to posterity.»

- ^ Parra Membrives 2002, p. 43.

- ^ von Raumer 1851, pp. 194–272.

- ^ Sonderegger 2003, p. 245.

- ^ a b Braune & Heidermanns 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Marchand 1992.

- ^ Braune, Helm & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 179.

- ^ Braune & Heidermanns 2018, p. 41.

- ^ Wright 1906, p. 2.

- ^ But see Fausto Cercignani (2022). The development of the Old High German umlauted vowels and the reflex of New High German /ɛ:/ in Present Standard German. Linguistik Online. 113/1: 45–57. Online

- ^ Braune & Heidermanns 2018, pp. 87–93.

- ^ Schrodt 2004, pp. 9–18.

- ^ Kuroda 1999, p. 90.

- ^ Kuroda 1999, p. 52.

- ^ Wright 1888.

- ^ Sonderegger 1979, p. 269.

- ^ Moser, Wellmann & Wolf 1981, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Morris 1991, pp. 161–167.

- ^ Sonderegger 1979, p. 271.

- ^ Braune & Heidermanns 2018, pp. 331–336.

- ^ Fleischer & Schallert 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Fleischer & Schallert 2011, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Schmidt 2013, p. 276.

- ^ Braune, Helm & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 12.

- ^ Salmons 2012, p. 161.

- ^ Braune & Heidermanns 2018, pp. 338–339.

- ^ Braune & Heidermanns 2018, p. 322.

- ^ a b Braune, Helm & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 56.

- ^ Braune, Helm & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 11.

- ^ a b Braune, Helm & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 34.

Sources[edit]

- Althaus, Hans Peter; Henne, Helmut; Weigand, Herbert Ernst, eds. (1980). Lexikon der Germanistischen Linguistik (in German) (2nd rev. ed.). Tübingen. ISBN 3-484-10396-5.

- Bostock, J. Knight (1976). King, K. C.; McLintock, D. R. (eds.). A Handbook on Old High German Literature (2nd ed.). Oxford. ISBN 0-19-815392-9.

- Braune, W.; Helm, K.; Ebbinghaus, E. A., eds. (1994). Althochdeutsches Lesebuch (in German) (17th ed.). Tübingen. ISBN 3-484-10707-3.

- Fleischer, Jürg; Schallert, Oliver (2011). Historische Syntax des Deutschen: eine Einführung (in German). Tübingen: Narr. ISBN 978-3-8233-6568-6.

- Hutterer, Claus Jürgen (1999). Die germanischen Sprachen. Ihre Geschichte in Grundzügen (in German). Wiesbaden: Albus. pp. 336–341. ISBN 3-928127-57-8.

- Keller, R. E. (1978). The German Language. London. ISBN 0-571-11159-9.

- Kuroda, Susumu (1999). Die historische Entwicklung der Perfektkonstruktionen im Deutschen (in German). Hamburg: Helmut Buske. ISBN 3-87548-189-5.

- Marchand, James (1992). «OHTFRID’S LETTER TO LIUDBERT». The Saint Pachomius Library. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Meineke, Eckhard; Schwerdt, Judith (2001). Einführung in das Althochdeutsche. UTB 2167 (in German). Paderborn: Schöningh. ISBN 3-8252-2167-9.

- Morris RL (1991). «The Rise of Periphrastic Tenses in German: The Case Against Latin Influence». In Antonsen EH, Hock HH (eds.). Stæfcraft. Studies in Germanic Linguistics. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins. ISBN 90-272-3576-7.

- Moser, Hans; Wellmann, Hans; Wolf, Norbert Richard (1981). Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. 1: Althochdeutsch — Mittelhochdeutsch (in German). Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer. ISBN 3-494-02133-3.

- Parra Membrives, Eva (2002). Literatura medieval alemana (in Spanish). Madrid: Síntesis. ISBN 978-847738997-2.

- Penzl, Herbert (1971). Lautsystem und Lautwandel in den althochdeutschen Dialekten (in German). Munich: Hueber.

- Penzl, Herbert (1986). Althochdeutsch: Eine Einführung in Dialekte und Vorgeschichte (in German). Bern: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-261-04058-0.

- Peters R (1985). «Soziokulturelle Voraussetzungen und Sprachraum des Mittleniederdeutschen». In Besch W, Reichmann O, Sonderegger S (eds.). Sprachgeschichte. Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und ihrer Erforschung (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 1211–1220. ISBN 3-11-009590-4.

- von Raumer, Rudolf (1851). Einwirkung des Christenthums auf die Althochdeutsche Sprache (in German). Berlin: S.G.Liesching.

- Roelcke T (1998). «Die Periodisierung der deutschen Sprachgeschichte». In Besch W, Betten A, Reichmann O, Sonderegger S (eds.). Sprachgeschichte (in German). Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 798–815. ISBN 3-11-011257-4.

- Salmons, Joseph (2012). A History of German. Oxford University. ISBN 978-0-19-969794-6.

- Scherer, Wilhelm (1878). Zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (in German) (2nd ed.). Berlin: Weidmann.

- Schmidt, Wilhelm (2013). Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (in German) (11th ed.). Stuttgart: Hirzel. ISBN 978-3-7776-2272-9.

- Sonderegger, S. (2003). Althochdeutsche Sprache und Literatur (in German) (3rd ed.). de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-004559-1.

- Sonderegger, Stefan (1979). Grundzüge deutscher Sprachgeschichte (in German). Vol. I. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017288-7.

- Sonderegger S (1980). «Althochdeutsch». In Althaus HP, Henne H, Weigand HE (eds.). Lexikon der Germanistischen Linguistik (in German). Vol. III (2nd ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. p. 571. ISBN 3-484-10391-4.

- Wells, C. J. (1987). German: A Linguistic History to 1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815809-2.

- Wright, Joseph (1888). An Old High-German Primer. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Grammars[edit]

- Braune, Wilhelm; Heidermanns, Frank (2018). Althochdeutsche Grammatik I: Laut- und Formenlehre. Sammlung kurzer Grammatiken germanischer Dialekte. A: Hauptreihe 5/1 (in German) (16th ed.). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-051510-7.

- Schrodt, Richard (2004). Althochdeutsche Grammatik II: Syntax (in German) (15th ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 978-3-484-10862-2.

- Wright, Joseph (1906). An Old High German Primer (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Online version

Dialects[edit]

- Franck, Johannes (1909). Altfränkische Grammatik (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Schatz, Josef (1907). Altbairische Grammatik (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

External links[edit]

- Althochdeutsche Texte im Internet (8.–10. Jahrhundert) — links to a range of online texts

- Modern English-Old High German dictionary

Vocabulary Old High German

by Roland Schuhmann

The vocabulary contains 1258 meaning-word pairs («entries»)

corresponding to core LWT meanings from the recipient language

Old High German. The corresponding text chapter was published in the

book Loanwords in the World’s Languages. The language page Old High German

contains a list of all loanwords arranged by

donor languoid.

- Meaning-word pairs

- Description

| Word form | LWT code | Meaning | Core list | Borrowed status | Source words |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Field descriptions

| Old High German | |

|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

south of the so-called » Benrath Line » |

| speaker | since about 1050 none |

| Linguistic classification |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639 -1 |

— |

| ISO 639 -2 |

goh |

| ISO 639-3 |

goh |

As Old High German or Old High German (abbreviated Ahd. ) Is the oldest written form of German that has been used between 750 and 1050. Your previous language level , Pre-Old High German , is only documented by a few runic inscriptions and proper names in Latin texts.

The word “German” appears for the first time in a document from the year 786 in the Middle Latin form theodiscus . In a church assembly in England the resolutions “ tam latine quam theodisce ” were read out, that is “both Latin and in the vernacular” (this vernacular was, of course, Old English ). The Old High German form of the word is only documented much later: In the copy of an ancient language textbook in Latin, probably made in the second quarter of the 9th century, there was an entry of a monk who apparently did not use the Latin word galeola (crockery in the shape of a helmet) understood. He must have asked a confrere the meaning of this word and added the meaning in the language of the people. For his note he used the Old High German early form » diutisce gellit » («in German ‘bowl'»).

Territorial delimitation and division

The West Germanic language area (excluding Old English ) in the early Middle Ages .

Legend:

Old High German is not a uniform language, as the term suggests, but the name for a group of West Germanic languages that were spoken south of the so-called » Benrath Line » (which today runs from Düsseldorf — Benrath approximately in a west-east direction). These dialects differ from the other West Germanic languages by the implementation of the second (or standard German) sound shift . The dialects north of the “Benrath Line”, that is, in the area of the north German lowlands and in the area of today’s Netherlands , did not carry out the second sound shift. To distinguish them from Old High German, these dialects are grouped under the name Old Saxon (also: Old Low German ). Middle and New Low German developed from Old Saxon . However, the Old Low Franconian , from which today’s Dutch later emerged, did not take part in the second sound shift, which means that this part of Franconian does not belong to Old High German.

Since Old High German was a group of closely related dialects and there was no uniform written language in the early Middle Ages , the text that has been handed down can be assigned to the individual Old High German languages, so that one often speaks more appropriately of (Old) South Rhine Franconian , Old Bavarian , Old Alemannic , etc. These West Germanic varieties with the second sound shift, however, show a different proximity to one another, which is the reason for the later differences between Upper , Middle and Low German . For example, Stefan Sonderegger writes that with regard to the spatial-linguistic-geographical structure, Old High German should be understood as follows:

«The oldest stages of the Middle and High Franconian, d. H. West Central German dialects one hand and the Alemannic and Bavarian, ie Upper German dialects on the other, and. in time ahd the first time tangible, but at the same time already dying language level of Lombard in northern Italy . The Ahd remains clearly separated. from the Old Saxon in the subsequent north, while a staggered transition can be determined to the Old Dutch-Old Lower Franconian and West Franconian in the northwest and west . »

— Sonderegger

Old high German traditions and written form

The Latin alphabet was adopted in Old High German for the German language. On the one hand, there were surpluses of graphemes such as <v> and <f> and, on the other hand, “uncovered” German phonemes such as diphthongs , affricates (such as / pf /, / ts /, / tʃ /), and consonants such as / ç / < ch> and / ʃ / <sch>, which did not exist in Latin. In Old High German, the grapheme <f> was mainly used for the phoneme / f /, so that here it is fihu (cattle), filu (a lot), fior (four), firwizan (to refer) and folch (people), while in Middle High German The grapheme <v> was predominantly used for the same phoneme, but here it is called vinsternis (darkness), vrouwe (woman), vriunt (friend) and vinden (to find). These uncertainties, which still affect spellings like «Vogel» or «Vogt», can be traced back to the grapheme excesses described in Latin.

The oldest surviving Old High German text is the Abrogans , a Latin-Old High German glossary. In general, the Old High German tradition consists largely of spiritual texts ( prayers , baptismal vows, Bible translation ); only a few secular poems ( Hildebrandslied , Ludwigslied ) or other language certificates (inscriptions, magic spells ) are found. The Würzburg mark description or the Strasbourg oath of 842 belong to public law, but these are only passed down in the form of a copy by a Romance-speaking copyist from the 10th and 11th centuries.

The so-called » Old High German Tatian » is a translation of the Gospel Harmony by the Syrian-Christian apologist Tatianus (2nd century) into Old High German. He is bilingual (Latin-German); the only surviving manuscript is now in St. Gallen. Alongside the Old High German Isidor, the Old High German Tatian is the second major translation achievement from the time of Charlemagne.

In connection with the political situation, the written form in general and the production of German-language texts in particular decreased in the 10th century; a renewed use of German-language writing and literature can be observed from around 1050. Since the written tradition of the 11th century differs significantly from the older tradition in phonetic terms, the language is called Middle High German from around 1050 onwards . Notker’s death in St. Gallen 1022 is often defined as the end point of Old High German text production .

Characteristics of language and grammar

Old High German is a synthetic language .

umlaut

The Old High German primary umlaut is typical of Old High German and important for the understanding of certain forms in later language levels of German (such as the weak verbs that are written back ) . The sounds / i / and / j / in the following syllable cause / a / to be changed to / e /.

Final syllables

Characteristic of the Old High German language are the endings, which are still full of vowels (see Latin ).

| Old High German | New High German |

|---|---|

| mahhôn | do |

| day | Days |

| demo | the |

| perga | mountains |

The weakening of the final syllables in Middle High German from 1050 is the main criterion for the delimitation of the two language levels.

Nouns

The noun has four cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative) and remnants of a fifth ( instrumental ) are still present. A distinction is made between a strong (vowelic) and a weak (consonantic) declination .

| number | case | masculine | feminine | neutral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Nom. | han o | tongue a | hërz a |

| Acc. | han on, -un | zung ūn | hërz a | |

| Date | han en, -in | zung ūn | hërz en, -in | |

| Gene. | ||||

| Plural | Nom. | han on, -un | zung ūn | hërz un, -on |

| Acc. | ||||

| Date | han ōm, -ōn | zung ōm, -ōn | hërz ōm, -ōn | |

| Gene. | han ōno | zung ōno | hërz ōno | |

| meaning | Rooster | tongue | heart |

Further examples of masculine nouns are stërno (star), namo (name), forasago (prophet), for feminine nouns quëna (woman), sunna (sun) and for neutral ouga (eye), ōra (ear).

Personal pronouns

| number | person | genus | Nominative | accusative | dative | Genitive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | ih | mih | me | mīn | |

| 2. | you | dih | to you | dīn | ||

| 3. | Masculine | (h) he | inan, in | imu, imo | (sīn) | |

| Feminine | siu; sī, si | sia | iro | ira, iru | ||

| neuter | iz | imu, imo | it is | |||

| Plural | 1. | we | unsih | us | our | |

| 2. | ir | iuwih | iu | iuwēr | ||

| 3. | Masculine | she | iro | in, in | ||

| Feminine | sio | |||||

| neuter | siu |

- The form of politeness corresponds to the 2nd person plural.

- Next to our and iuwer there are also unsar and iuwar , and next to iuwar and iuwih there are also iwar and iwih .

- In Otfrid also the genitive dual 1st person finds: Unker (or uncher , as Unkar or unchar shown).

Demonstrative pronouns

In the Old High German period, however, one still speaks of the demonstrative pronoun , because the specific article as a grammatical phenomenon did not develop from the demonstrative pronoun until late Old High German.

| case | Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | neutrally | Female | male | neutrally | Female | |

| Nominative | of the | daȥ | diu | dē, dea, dia, die | diu, (dei?) | deo, dio |

| accusative | the | dea, dia (the) | ||||

| dative | dëmu, -o | dëru, -o | the the | |||

| Genitive | of | dëra, (dëru, -o) | dëru | dëra |

Nominative and accusative are quite arbitrary in the plural and differ from dialect to dialect, so that an explicit separation of which of these forms expressly describes the accusative and which the nominative is not possible. In addition, on the basis of this list, one can already see a slow collapse of the various forms. While there are still many quite irregular forms in the nominative and accusative plural, the dative and genitive, both in the singular and in the plural, are relatively regular.

Verbs

A distinction is also made between strong (vowel) and weak conjugation in verbs. The number of weak verbs was always higher than that of strong verbs, but the second group was significantly more extensive in Old High German than it is today. In addition to these two groups, there are the past tense , verbs that have a present tense meaning with their original past tense form.

Strong verbs

In the case of strong verbs, in Old High German there is a change in the vowel in the basic morphem , which carries the lexical meaning of the word. The inflection (inflection) of the words is indicated by inflectional morphemes (endings). There are seven different ablaut series in Old High German, the seventh not being based on an ablaut , but rather on reduplication .

| Ablaut series | infinitive | Present | preterite | Plural | participle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. | a | ī + consonant (neither h nor w ) | ī | egg | i | i |

| I. | b | ī + h or w | ē | |||

| II. | a | io + consonant (neither h nor dental ) | iu | ou | u | O |

| II. | b | io + h or Dental | O | |||

| III. | a | i + nasal or consonant | i | a | u | u |

| III. | b | e + liquid or consonant | O | |||

| IV. | e + Nasal or Liquid | i | a | — | O | |

| V. | e + consonant | i | a | — | e | |

| VI. | a + consonant | a | uo | uo | a | |

| VII. | ā, a, ei, ou, uo or ō | ie | ie | like Inf. |

Examples in reconstructed and unified Old High German:

- Ablaut series Ia

- r ī tan — r ī tu — r ei t — r i tun — gir i tan (nhd. riding, driving)

- Ablaut series Ib

- z ī han — z ī hu — z ē h — z i gun — giz i gan (nhd. accuse, draw)

- Ablaut series II.a

- b io gan — b iu gu — b ou g — b u gun — gib o gan (nhd. bend)

- Ablaut series II.b

- b io tan — b iu tu — b ō t — b u tun — gib o tan (nhd. offer)

- Ablaut series III.a.

- b i ntan — b i ntu — b a nt — b u ntun — gib u ntan (nhd. to bind)

- Ablaut series III.b.

- w e rfan — w i rfu — w a rf — w u rfun — giw o rfan (nhd. throw)

- Ablaut series IV.

- n e man — n i mu — n a m — n ā mun — gin o man (nhd. to take)

- Ablaut series V.

- g e ban — g i bu — g a b — g ā bun — gig e ban (nhd. to give)

- Ablaut series VI.

- f a ran — f a ru — f uo r — f uo run — gif a ran (nhd. drive)

- Ablaut series VII.

- r ā tan — r ā tu — r ie t — r ie tun — gir ā tan (nhd. guess)

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | throw u | threw |

| 2. | you | throw is / throw is | litter i | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | throw it | threw | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | throw emēs (throw ēn ) | throw over (throw over ) | |

| 2. | ir | throw et | litter ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | throw ent | throw un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | throw e | litter i |

| 2. | you | throw ēs / throw ēst | wurf īs / wurf īst | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | throw e | litter i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | werf ēm (throw emēs ) | litter īm (litter īmēs ) | |

| 2. | ir | throw eT | throw īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | throw ēn | throw īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | throw | ||

| Plural | throw et | ||||

| participle | throw anti / throw enti | gi worf at |

Example: werfan — werfu — threw — wurfun — giworfan (nhd. Throw) according to the ablaut series III. b

Weak verbs

The weak verbs of Old High German can be morphologically and semantically divided into three groups via their endings:

Verbs with the ending -jan- with a causative meaning (to do something, to bring about) are elementary for understanding the weak verbs with back umlaut that are very common in Middle High German and are still partially present today , as the / j / in the ending is the primary umlaut described above effected in the present tense.

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | cell u | cell it a |

| 2. | you | cell is | cell it os | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | cell it | cell it a | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | cell umēs | cell it around | |

| 2. | ir | zell et | cell it ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | cell ent | cell it un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | zel e | zel it i |

| 2. | you | cell ēst | zel it īs | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | zel e | zel it i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | zel ēm | zel it īm | |

| 2. | ir | zel ēt | zel it īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | zel ēn | zel it īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | zel | ||

| Plural | zell et |

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | mahh om | mahh ot a |

| 2. | you | mahh os | mahh ot os | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | mahh ot | mahh ot a | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | mahh omēs | mahh ot um | |

| 2. | ir | mahh ot | mahh ot ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | mahh ont | mahh ot un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | mahh o | mahh ot i |

| 2. | you | mahh о̄s | mahh ot īs | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | mahh o | mahh ot i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | mahh о̄m | mahh ot īm | |

| 2. | ir | mahh о̄t | mahh ot īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | mahh о̄n | mahh ot īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | mahh o | ||

| Plural | mahh ot |

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | tell em | say et a |

| 2. | you | say it | say et os | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | say et | say et a | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | say emes | Tell et order | |

| 2. | ir | say et | say et ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | say ent | Tell et un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | say e | say et i |

| 2. | you | say ēs | say et īs | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | say e | say et i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | say ēm | say et im | |

| 2. | ir | say ēt | say et īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | say ēn | say et īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | say e | ||

| Plural | say et |

Special verbs

The Old High German verb sīn ‘ to be’ is referred to as the verb noun substantivum because it can stand on its own and describes the existence of something. It is one of the root verbs that have no connecting vowel between stem and inflection morphemes. These verbs are also known as athematic (without connective or subject vowels). The special thing about sīn is that its paradigm is suppletive, i.e. is formed from different verb stems ( idg. * H₁es- ‘exist’, * bʰueh₂- ‘grow, flourish’ and * h₂ues- ‘linger, live, stay overnight’). In the present subjunctive there is still the sīn, which goes back to * h₁es- (the indicative forms starting with b , on the other hand, go back to * bʰueh₂- ), but in the past tense it is given by the strong verb wesan (nhd. Was , would ; see also nhd. Essence ), which is formed after the fifth ablaut row.

| number | person | pronoun | indicative | conjunctive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | ih | bim, am | sī |

| 2. | you | are | sīs, sīst | |

| 3. | he, siu, ez | is | sī | |

| Plural | 1. | we | birum, birun | sīn |

| 2. | ir | birut | sīt | |

| 3. | she, sio, siu | sint | sīn |

Tense

In Germanic there were only two tenses: the past tense for the past and the present tense for the non-past (present, future). With the onset of writing and translations from Latin into German, the development of German equivalents for Latin tenses such as perfect , past perfect , future I and future II in Old High German began. At least approaches to having and being perfect can already be made out in Old High German. The development was continued in Middle High German .

pronunciation

The reconstruction of the pronunciation of Old High German is based on a comparison of the traditional texts with the pronunciation of today’s German, German dialects and related languages. This results in the following pronunciation rules:

- Vowels are always to be read briefly, unless they are expressly indicated as long vowels by an overline or circumflex . Only in New High German are vowels spoken long in open syllables .

- The diphthongs ei, ou, uo, ua, ie, ia, io and iu are spoken as diphthongs and are emphasized on the first component. It should be noted that the letter <v> sometimes has the sound value u.

- The stress is always on the root, even if any of the following syllables contain a long vowel.

- The sound values of most consonant letters correspond to those of today’s German. Since the final hardening only took place in Middle High German, <b>, <d> and <g> are spoken voiced differently than in modern German .

- The graph <th> was spoken in early Old High German as a voiced dental fricative [ð] (like <th> in English the ), but from around 830 onwards one can read [d].

- <c> — just like the more frequently occurring <k> — is spoken as [k], even when it appears in connection with <s> — i.e. as <sc>.

- <z> is ambiguous and partly stands for [ts], partly for the voiceless [s].

- <h> is initially spoken as [h], internally and finally as [x].

- <st> is also spoken in the wording [st] (not like today [ʃt]).

- <ng> is spoken [ng] (not [ŋ]).

- <qu> is spoken like in today’s German [kv].

- <uu> (which is often transcribed as <w>) is pronounced like the English half-vowel [ w ] ( water ).

See also

- Old high German literature

- German language history

literature

- Eberhard Gottlieb Graff : Old high German vocabulary or dictionary of the old high German language. I-VI. Berlin 1834–1842, reprint Hildesheim 1963.

- Hans Ferdinand Massmann : Complete alphabetical index to the old high German linguistic treasure of EG Graff. Berlin 1846, reprint Hildesheim 1963.

- Rolf Bergmann u. a. (Ed.): Old High German.

- Grammar. Glosses. Texts. Winter, Heidelberg 1987, ISBN 3-533-03877-7 .

- Words and names. Research history. Winter, Heidelberg 1987, ISBN 3-533-03940-4 .

- Wilhelm Braune : Old High German grammar. Halle / Saale 1886; 3rd edition ibid. 1925 (last edition; continued under Karl Helm, Walther Mitzka , Hans Eggers and Ingo Reiffenstein ) = collection of short grammars of Germanic dialects A, 5; newer edition z. B. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-484-10861-4 .

- Axel Lindqvist: Studies on word formation and choice of words in Old High German with special regard to the nominia actionis. In: [Paul and Braunes] contributions to the history of the German language and literature. Volume 60, 1936, pp. 1-132.

- Eckhard Meineke, Judith Schwerdt: Introduction to Old High German (= UTB 2167). Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2001, ISBN 3-8252-2167-9 .

- Horst Dieter Schlosser : Old High German Literature. 2nd edition, Berlin 2004.

- Richard Schrodt : Old High German Grammar II. Syntax. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-484-10862-2 .

- Rudolf Schützeichel : Old High German Dictionary. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1969; newer edition 1995, ISBN 3-484-10636-0 .

- Rudolf Schützeichel (Ed.): Old High German and Old Saxon Gloss Vocabulary. Edited with the participation of numerous scientists from home and abroad and on behalf of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. 12 volumes, Tübingen 2004.

- Stefan Sonderegger : Old High German Language and Literature. An introduction to the oldest German. Presentation and grammar. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin [a. a.] 1987, ISBN 3-11-004559-1 .

- Bergmann, Pauly, Moulin: Old and Middle High German. Workbook on the grammar of the older German language levels and on the history of the German language. 7th edition, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-20836-6 .

- Jochen Splett: Old High German Dictionary. Analysis of the word family structures of Old High German, at the same time laying the groundwork for a future structural history of the German vocabulary, I.1 – II. Berlin / New York 1993, ISBN 3-11-012462-9 .

- Taylor Starck, John C. Wells : Old High German Glossary Dictionary (including the glossary index started by Taylor Starck). Heidelberg (1972–) 1990.

- Elias Steinmeyer , Eduard Sievers : The old high German glosses. IV, Berlin 1879-1922; Reprinted Dublin and Zurich 1969.

- Rosemarie Lühr : The Beginnings of Old High German. In: NOWELE 66, 1 (2013), pp. 101–125. ( Full text )

- Andreas Nievergelt: Old High German in runic script. Cryptographic vernacular pen glosses . 2nd edition, Stuttgart 2018, ISBN 978-3-777-62640-6 .

Web links

- Online dictionary , Wikiling: Old High German (and other ancient languages)

- Old high German dictionary

- Old High German in the World Loanword Database

- Old High German in the International Dictionary Series. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014 ; accessed on March 17, 2016 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jochen A. Bär: A short history of the German language .

- ^ Map based on: Meineke, Eckhard and Schwerdt, Judith, Introduction to Old High German, Paderborn / Zurich 2001, p. 209.

- ↑ Stefan Sonderegger: Old High German Language and Literature , page 4

- ↑ Oscar Schade: Old German Dictionary . Halle, 1866, page 664.

- ↑ Adalbert Jeitteles: KA Hahns Old High German Grammar along with some reading pieces and a glossary 3rd edition, Prague, 1870, page 36 f.

- ↑ Otfrid von Weißenburg, Gospel Book, Book III, Chapter 22, Verse 32

- ↑ Adalbert Jeitteles: KA Hahn’s Old High German Grammar along with some reading pieces and a glossary 3rd edition. Prague 1870, page 37.

- ↑ Ludwig M. Eichinger : Inflection in the noun phrase. In: Dependenz und Valenz. 2nd half volume, Ed .: Vilmos Ágel u. a. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2006, p. 1059.

- ^ Rolf Bergmann, Claudine Moulin, Nikolaus Ruge: Old and Middle High German . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8252-3534-5 , pp. 171ff.

- ^ Rolf Bergmann, Claudine Moulin, Nikolaus Ruge: Old and Middle High German — Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, p. 173.

In old Germany,‘’Minnesingers» and‘’Spielleute» were the equivalent

to what we call buskers today.

В старой Германии« миннезингеры» и« менестрели» были равносильны тому,

что мы называем сегодня уличным исполнительном искусством.

Civil society in Germany has old democratic traditions.

В Германии гражданское общество имеет старые демократические традиции.

Old hates between Protestant Germany and Catholic France.

German publication Bild review was the most beautiful old world fairs outside Germany.

Немецкое издание Bild составило обзор самых красивых ярмарок Старого Света за пределами Германии.

In 2002 Prince Franz Wilhelm with Theodor Tantzen founded the Prinz von Preussen development company,

В 2002 году принц Франц Вильгельм вместе с Теодором Танценом основал инвестиционную компанию Prinz von Preussen,

The average gender pay gap of 23 per cent

is very unequally distributed between the new and the old Länder in Germany.

Средний показатель гендерного разрыва в оплате труда, составляющий 23%,

крайне неравномерно распределен между новыми и старыми землями в Германии.

All we have is a 17 year old picture from Hamburg, Germany.

I can get his old sprayer back from that Germany place.

In the old Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and Maoist China,

the police’ main job was not fighting crime.

В бывшем Советском Союзе, нацистской Германии, и маоистском Китае,

основной работой полиции была не борьба с преступностью.

The all-white tower in the old city of Ravensburg in Germany is called Mehlsack.

Белоснежная как мука башня в старинной части города Равенсбург в Германии называется Mehlsack.

The GDR had entered no reservations when ratifying the Covenant, so it was valid for the whole State,

with the reservations entered by the old Federal Republic of Germany.

ГДР, ратифицируя Пакт, не внесла никаких оговорок, и поэтому его положения действуют в отношении всего

государства с учетом оговорок, внесенных бывшей Федеративной Республикой Германией.

In Germany, approximately every fourth person is over 60 years old.

The Ostenfelder Bauernhaus(Nordhusumer Str.13)

is an old farmhouse and the

oldest

open-air museum in Germany.

Три тюрингенских крестьянских дома в Рудольштадте являются самым старым музеем под открытым небом в Германии.

Mr. Dirk Jarré, European Federation of Older People, Germany; NGO forum coordinator.

Г-н Дирк Ярре, Европейская федерация пожилых людей, Германия; координатор форума НПО.

Hamburg Airport is the oldest airport in Germany still in operation.

The Christmas market in Dresden is one of the oldest fairs in Germany.

The line was opened in 1854 and is one of the oldest railways in Germany.

Линия была открыта в 1854 году и является одной из старейших железных дорог в Германии.

Впервые был присужден в 1948 году и является старейшей немецкой наградой в области средств массовой информации.

The Ruprecht-Karls-University is one of the

oldest

European universities and the oldest in Germany.

It still stands today and is one of oldest stone bridges in Germany.

Это здание, сохранившееся до сего дня, является одним из старейших вокзальных зданий в Германии.

Ronald Zimmermann 51 years

old,

Germany Alicante School“It was a very good

decision to study here, very good host family, made me feel part of family and home.

Рональд Циммерман 51 год, Германия Аликанте“ Это было очень хорошее решение приехать сюда,

очень хорошая принимающая семья, где ч смог почувствовать себя как дома. Хорошие учителя и красивый город.

Think that old guy in

Germany

changed her?

Думаешь, тот старый немец изменил ее?

Pemper was 19 years

old

when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939.

Пемперу было 19 лет, когда фашистская Германия напала на Польшу в 1939 году.

When she was 6 years

old

she moved to Germany.

В возрасте шести лет она переехала в Англию.

The Vogelsberg is the two

oldest

nature park in Germany.

Фогельсберг это два самых старых природный парк в Германии.

Dubois began playing hockey when he was three years

old

in Germany while his father played in the DEL.

Дюбуа начал играть

в

хоккей в Германии, когда ему было три года,

в

то время его отец играл

в

Немецкой хоккейной лиге.

Results: 277582,

Time: 0.1939