From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In Russia, the Word of the Year (Russian: Слово года) poll is carried out since 2007 by the Expert Council of the Centre for Creative Development of the Russian Language headed by Russian-American philologist Mikhail Epstein.

2015[edit]

In December 2015, Epstein reported in his blog «Snob» the following results.[1]

- Word of the year: БЕЖЕНЦЫ (Refugees), in reference to the refugee from Middle East.

- Phrase of the year:: НЕМЦОВ МОСТ (Nemtsov’s Bridge), a suggestion to rename the bridge where Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov was assassinated.

- Anti-language: ОБАМА — ЧМО (Obama chmo, «Obama the schmuck»)

- Neololgism: БЕССМЕРТНЫЙ БАРАК (Immortal Barrack, by Андрей Десницкий). The term was coined in an analogy to the «Immortal Regiment». The latter was an annual action to commemorate the nameless heroes perished in Great Partiotic War. The «Immortal Barrack» action was suggested to commemorate the perished in Stalinist Gulag labor camps.

2016[edit]

In December 2016, Epstein reported in his blog «Snob» the following results.

- Word of the year: БРЕКСИТ (BREXIT), in reference to Brexit.

- Phrase of the year:: ОЧЕРЕДЬ НА СЕРОВА/АЙВАЗОВСКОГО (Queue to Serov and Aivazovsky exhibitions, famous Russian artists of the 19th c.; there were huge queues to their exhibitions at Moscow Tretiakov gallery).

- Anti-language: «Денег нет, но вы держитесь» (“There is no money for you, but you should stand firm» (Dmitry Medvedev’s response to someone complaining about pensions in Crimea))

- Neololgism: 1.ЗЛОВЦО (Evil word). 2.НЕУЕЗЖАНТ Non–leaver – the one who has the opportunity to emigrate but prefers to stay in Russia.

2017[edit]

In December 2017, Epstein reported in his blog «Snob» the following results.

- Word of the year: РЕНОВАЦИЯ (renovation), in reference to the program on new housing in Moscow.

- Phrase of the year:: ОН ВАМ НЕ ДИМОН (He is not Dimon for you, in reference to the title of A. Navalnyi’s film on Dmitriy (Dimon) Medvedev)

- Anti-language: Иностранный агент (Foreign agent)

- Neololgism: 1.ГОП-ПОЛИТИКА, ГОП-ЖУРНАЛИСТИКА, ГОП-РЕЛИГИЯ (hoo–hoo–politics, hoo–hoo–journalism, hoo–hoo–religion, from Russian «gop-«, «gopota» referring to «hoodlum» and «hooliganism» in various aspects of social life). 2. ДОМОГАНТ (harasser, in reference to sex–scandals in the USA)

Previous years[edit]

- 2007 — гламур («glamour»)

- 2008 — кризис («crisis», Great Recession)

- 2009 — перезагрузка («reset», Russian reset)

- 2010 — огнеборцы («firefighters», 2010 Russian wildfires)

- 2011 — полиция[2] («police»)

- 2012 — Болотная[3] (Bolotnaya Square)

- 2013 — госдура[4] (Gosdura, a pun with Gosduma, a Russian acronym for State Duma, dura is the feminine for durak, «fool»)

- 2014 — крымнаш[5] (Krymnash, a contraction of «Крым наш», «Crimea is Ours»)

- 2015 — беженцы («refugees», European migrant crisis)

- 2016 — Брексит («Brexit»)

- 2017 — реновация (program of renovation of housing in Moscow)

- 2018 — Новичок («Novichok» )

References[edit]

- ^ «СЛОВО ГОДА-2015. ИТОГИ ВЫБОРОВ», Mikhail Epstein, December 12, 2015

- ^ В России выбрали слово года › MR7.ru

- ^ В России провели неофициальный конкурс «Слово года-2012» | Новости переводов

- ^ Слово года-2013. Главные итоги – Михаил Эпштейн – Блог – Сноб

- ^ Российские лингвисты объявили «крымнаш» словом года — Новости (Культура, общество, конкурс, русский) — sibnovosti.ru

- Russian-language «Word of the Year 2015»: «СЛОВО ГОДА-2015. ИТОГИ ВЫБОРОВ»

- Russian-language «Word of the Year 2016»: «Куда движется язык? Слова и лейтмотивы 2016 года»

- Russian-language «Word of the Year 2017»: «СЛОВО-2017. Вербальный портрет года»

Русский опрос

В Россия, Опрос «Слово года» (Русский : Слово года) проводится с 2007 года Экспертным советом Центра творческого развития русского языка под руководством русско-американского филолога Михаила Эпштейна..

Содержание

- 1 2015

- 2 2016

- 3 2017

- 4 Предыдущие годы

- 5 Ссылки

2015

В декабре 2015 года Эпштейн сообщил в своем блоге: « Сноб »следующие результаты.

- Слово года: БЕЖЕНЦЫ (Беженцы), в ссылка на беженца с Ближнего Востока.

- Фраза года :: НЕМЦОВ МОСТ (Мост Немцова ), предложение переименовать мост, на котором лидер российской оппозиции Борис Немцов был убит.

- Антиязыковая: ОБАМА — ЧМО (Обама чмо, «Обама-придурок»)

- Неологизм: БЕССМЕРТНЫЙ БАРАК (Бессмертный казарм, Андрей Десницкий). Термин был придуман по аналогии с «Бессмертный полк ». Последний был ежегодной акцией, посвященной памяти безымянных героев, погибших в Великой Отечественной войне. Акция «Бессмертный барак» была предложена в память о погибших в сталинских ГУЛАГе трудовых лагерях.

2016

В декабре 2016 года Эпштейн сообщил в своем блог «Сноб» следующие результаты.

- Слово года: БРЕКСИТ (BREXIT) в отношении Brexit.

- Фраза года: ОЧЕРЕДЬ НА СЕРОВА / АЙВАЗОВСКОГО (Очередь к Серову и Айвазовскому выставок, известные русские художники XIX века, на их выставки в Москве огромные очереди Третьяковская галерея ).

- Антиязык: «Денег нет, но вы держитесь» («Денег на вас нет., но стой твердо »(ответ Дмитрия Медведева на жалобы на пенсии в Крыму)

- Неологизм: 1.ЗЛОВЦО (Злое слово). 2.НЕУЕЗЖАНТ Неизвестный — тот, кто имеет возможность эмигрировать, но предпочитает оставаться в России.

2017

В декабре 2017 года Эпштейн сообщил в своем блоге «Сноб» следующие результаты.

- Слово года: РЕНОВАЦИЯ (реновация), применительно к программе строительства нового жилья в Москве.

- Фраза года :: ОН ВАМ НЕ ДИМОН (, по названию фильма А. Навального о Дмитрии (Димоне) Медведеве))

- Антиязыковый: Иностранный агент (Иностранный агент )

- Неологизм: 1.ГОП-ПОЛИТИКА, ГОП-ЖУРНАЛИСТИКА, ГОП-РЕЛИГИЯ (от русского «гоп-», «гопота», имея в виду «хулиган » и «хулиганство» в различных аспектах общественной жизни).). 2. ДОМОГАНТ (преследователь, применительно к секс-скандалам в США)

Предыдущие годы

- 2007 — гламур («гламур»)

- 2008 — кризис («кризис», Великий Recession )

- 2009 — перезагрузка («перезагрузка», российская перезагрузка )

- 2010 — огнеборцы («пожарные», 2010, российские лесные пожары )

- 2011 — полиция («полиция»)

- 2012 — Болотная (Болотная площадь )

- 2013 — госдура (Госдура, каламбур с Госдумой, русское сокращение от Государственная Дума, dura — женский род от durak, «дурак»)

- 2014 — крымнаш (сокращение от «Крым наш», «Крым наш «)

- 2015 — беженцы (« беженцы », Европейский миграционный кризис )

- 2016 — Брексит (« Brexit »)

- 2017 — реновация (программа реновации жилья в Москве)

- 2018 — Новичок («Новичок «)

Список литературы

- Русскоязычный » Слово года 2015 »: « СЛОВО ГОДА-2015. ИТОГИ ВЫБОРОВ »

- Русскоязычное« Слово года 2016 »: « Куда движется язык? Слова и лейтмотивы 2016 года »

- Русскоязычное «Слово года 2017» : «СЛОВО-2017. Вербальный портрет года »

В России , то Слово года ( России : Слово года ) Опрос проводится с 2007 года экспертным советом Центра творческого развития русского языка во главе русско-американского филолога Михаила Эпштейна .

2015 г.

В декабре 2015 года Эпштейн сообщил в своем блоге «Сноб» следующие результаты.

- Слово года: БЕЖЕНЦЫ (Беженцы) в отношении беженцев с Ближнего Востока .

- Фраза года :: НЕМЦОВ МОСТ ( Мост Немцова ), предложение переименовать мост, на котором был убит лидер российской оппозиции Борис Немцов .

- Антиязыковые: ОБАМА — ЧМО ( Обама чмо, «Обама-придурок»)

- Неологизм: БЕССМЕРТНЫЙ БАРАК (Immortal Barrack, Андрей Десницкий). Термин был придуман по аналогии с « Бессмертным полком ». Последний был ежегодной акцией, посвященной памяти безымянных героев, погибших в Великой Отечественной войне . Акция «Бессмертный барак» была предложена в память о погибших в лагерях сталинского ГУЛАГа .

2016 г.

В декабре 2016 года Эпштейн сообщил в своем блоге «Сноб» следующие результаты.

- Слово года: БРЕКСИТ (BREXIT), по поводу Brexit .

- Фраза года: ОЧЕРЕДЬ НА СЕРОВА / АЙВАЗОВСКОГО (Очередь на выставки Серова и Айвазовского , известных русских художников XIX века; на их выставки в Московской Третьяковской галерее стояли огромные очереди ).

- Антиязычный: «Денег нет, но вы держитесь» («Денег на вас нет, но вы должны стоять твердо» ( ответ Дмитрия Медведева на жалобы на пенсии в Крыму))

- Неологизм: 1.ЗЛОВЦО. 2.НЕУЕЗЖАНТ Не выезжающий — тот, кто имеет возможность эмигрировать, но предпочитает оставаться в России.

2017 г.

В декабре 2017 года Эпштейн сообщил в своем блоге «Сноб» следующие результаты.

- Слово года: РЕНОВАЦИЯ (реновация), применительно к программе строительства нового жилья в Москве.

- Фраза года :: ОН ВАМ НЕ ДИМОН ( Он для вас не Димон , отсылка к названию фильма А. Навального о Дмитрии (Димоне) Медведеве)

- Антиязыковый: Иностранный агент ( Иностранный агент )

- Неологизм: 1.ГОП-ПОЛИТИКА, ГОП-ЖУРНАЛИСТИКА, ГОП-РЕЛИГИЯ ( ху-ху-политика, ху-ху-журналистика, ху-ху-религия , от русского «гоп-», «гопота», относящееся к « хулигану » и «хулиганство» в различных сферах общественной жизни). 2. ДОМОГАНТ (преследователь, по поводу секс-скандалов в США).

Предыдущие годы

- 2007 — гламур («гламур»)

- 2008 — кризис («кризис», Великая рецессия )

- 2009 — перезагрузка («сброс», русский сброс )

- 2010 — огнеборцы («пожарные», 2010 Русские пожары )

- 2011 — полиция («полиция»)

- 2012 — Болотная ( Болотная площадь )

- 2013 — госдура ( Госдура , каламбур с Госдума, русское сокращение от Государственной Думы , dura — женский род от durak , «дурак»)

- 2014 — крымнаш (сокращение от «Крым наш», « Крым наш »)

- 2015 — беженцы («беженцы», европейский миграционный кризис )

- 2016 — Брексит («Брексит»)

- 2017 — реновация (программа реновации жилья в Москве)

- 2018 — Новичок (« Новичок »)

Ссылки

- Русскоязычное «Слово года 2015»: «СЛОВО ГОДА-2015. ИТОГИ ВЫБОРОВ»

- Русскоязычное «Слово года 2016»: «Куда движется язык? Слова и лейтмотивы 2016 года»

- Русскоязычное «Слово года 2017»: «СЛОВО-2017. Вербальный портрет года»

Акция «Слово года» (Word of the year) проводится в разных странах с конца прошлого века. Первой выбирать своё слово года начала Германия, именно там в 1971 году прошла первая в мире акция Wort des Jahres (нем. Слово года). Но мы сегодня поговорим про англоязычную версию акции и разберём слова, которые становились фаворитами в течение последних нескольких лет.

Какой-то единой акции для всего английского языка не существует, каждый год несколько организаций параллельно предлагают свою версию слова года. В англоязычном мире первопроходцем этой акции стало Американское диалектическое общество (American Dialect Society), которое начало выбирать слово года с 1991 года. Они продолжают составлять свои списки слов года и по сей день. За это время к акции присоединились и другие влиятельные организации — Collins English Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Oxford University Press, Macquarie Dictionary и другие. Есть свои версии для британского, американского и австралийского английского. Слова года — это маркеры реальности, по которым можно получить представление от времени, в котором мы живём. Мы посмотрим на слова года за последние 5 лет, разберемся, что они значат, как их использовать и что они говорят о нашей реальности.

Выбор American Dialect Society

2015: singular they

Очень важное слово для современного англоязычного мира. Казалось бы, they люди узнают в первые же недели изучения английского, зачем выделять его сейчас? Дело в том, что в последние годы у этого местоимения появилось новое значение: так самоопределяют себя небинарные люди (те, чья идентичность не укладывается в рамки строго женского или мужского пола). Используя they, можно обратиться к человеку, когда вы сомневаетесь насчёт его гендера и не хотите обидеть. Это местоимение к 2020 году стало широко употребительным, наверняка вы уже хотя бы раз сталкивались с ним, люди часто пишут, например, в соцсетях, какое обращение для них предпочтительно и часто это именно they.

2016: dumpster fire

Отличное выражение для отвратительных ситуаций. Возьмите на заметку, может пригодиться. Dumpster fire — это критическая ситуация, катастрофа. Тот день, в который всё пошло не так и обрушилось на вас хаосом. Иногда используется в немного другом значении: так можно сказать про очень сложное дело, за которое никто не хочет браться.

2017: fake news

Актуальное слово, которое хорошо отражает современную медийную повестку. Вы могли слышать это выражение и в русском языке. О том, что понимать под фейковыми новостями, всё ещё ведётся дискуссия. Больше всех недоволен fake news президент США Дональд Трамп, при этом именно к его твитам социальная сеть Twitter делает особую пометку, призывающую пользователей тщательнее проверять то, что пишет президент. Fake в переводе с английского означает «фальшивка»: старая-добрая газетная утка перекочевала в интернет и с распространением соцсетей, информационным бумом и мощным потоком непроверенных данных начала портить жизнь всем. Некоторые медиа сознательно распространяют фейковые новости, всегда проверяйте дважды и делайте свои выводы.

2018: tender age shelter

Сочетание, которое имеет прямую связь с американским политическим контекстом, но тем, кто все эти годы следил за тем, что происходит в Америке во время президентского срока Трампа, могут быть с ним знакомы. Это жутковатый эвфемизм, который придумало американское правительство для приютов, где удерживали детей мексиканских иммигрантов,

разлученных с семьей на границе Мексики и США. После того как Трамп принял в отношении мигрантов политику «нулевой терпимости» в таких приютах оказалось более 2500 детей. Tender age переводится с английского как «юный/нежный возраст», и, как отметил журналист The Guardian, от этого эвфемизма веет оруэлловским Большим Братом.

2019: (my) pronouns

Вернёмся немного назад к слову 2015 года they. Мы говорили, что к 2020 году оно стало гораздо более употребительным, а для людей стало важно указывать в соцсетях предпочтительные местоимения. С английского pronoun переводится как «местоимение». А (my) pronouns — это как раз то выражение, с помощью которого тысячи людей в соцсетях манифестируют свой гендер и предпочтительные местоимения. Например, вы можете увидеть в инстаграм-профиле описание “pronouns: she/her”.

Выбор Collins English Dictionary (британский)

2015: binge-watch

Спорим, это слово вы точно знаете? Всем любителям проводить вечера за сериалами посвящается. Binge переводится с английского как «взапой», когда вы делаете что-то и не можете остановиться. Выражение binge-watch стало популярным после того как стриминговый сервис Netflix начал выпускать свои сериалы сразу целыми сезонами в один день. Это разрушало привычную схему, когда сериал выходил постепенно и новую серию нужно было ждать каждую неделю. Теперь зритель получал возможность посмотреть весь сезон целиком и многие пользовались этой возможностью, устраивая себе вечера (а то и ночи) запойного просмотра.

2016: Brexit

Brexit для британцев действительно стало главным словом 2016, а медийные дискуссии об этом не утихают до сих пор, хотя прошёл уже не один год. Референдум состаялся в 2016 году, а из состава Евросоюза Великобритания официально вышла только зимой 2020. Слово Brexit появилось из слияния двух слов — «British» и «exit», что означает британский выход. Кстати, в тот же период в английском появилось несколько новых слов, связанных с Брекзитом, например, Breturn («British» + «return», использовали противники Брекзита, желавшие в вернуться в Евросоюз), Brexshit (ну тут вы и сами всё поняли), Leaver и Remainer (про сторонников идеи уйти или остаться в ЕС).

2017: Fake news

В 2017 году фейковые новости волновали не только американцев. Британский словарь тоже тогда выбрал словом года именно fake news.

2018: Single-use

Single-use переводится на русский как «одноразовый», обычно так говорят про товары, которые сделаны из пластика и выбрасываются после того, как их один раз использовали. Люди стали больше интересоваться тем, как одноразовый пластик влияет на экологию — количество запросов по слову single-use увеличилось в 4 раза с 2013 года. На фоне всё усиливающегося беспокойства по поводу изменения климата и других экологических проблем, Collins English Dictionary выбрали single-use словом 2018 года.

2019: Climate strike

Последним на сегодняшний день опубликованным словом года стала «забастовка за климат». Да-да, то самое, которое стало популярным после выступлений шведской экоактивистки Греты Тунберг. В конце 2018 года она решила каждую пятницу пропускать учёбы в школе, чтобы протестовать у здания парламента. Это привлекло внимание общества не только к самой Грете, но и к климатическим проблемам и волна акций в защиту экологии прокатилась по разным странам.

Выбор Merriam-Webster

2015: -ism

Вы удивитесь, но иногда словом года может стать… не слово! В 2015 году Merriam-Webster выбрали словом года суффикс -ism. Команда лингвистов основывалась на 7 самых частых поисковых запросов в электронном словаре заканчивались на этот суффикс. Больше всего людей в 2015 интересовало значение слов socialism (социализм), fascism (фашизм), racism (расизм), feminism (феминизм), communism (коммунизм), capitalism (капитализм), terrorism (терроризм).

2016: surreal

Surreal переводится как «сюрреалистичный» и в 2016 году количество запросов по этому слову тоже многократно возросло. Эксперты Merriam-Webster связывают это с несколькими событиями того года, которые вызвали у людей ощущение нереальности происходящего: теракты в Брюсселе и Ницце, и особенно результаты выборов в США 2016 года, после которых президентский пост занял Дональд Трамп.

2017: feminism

К 2017 году из всех слов с суффиксом -ism, которые были популярны у пользователей в 2015, в фавориты вышло слово феминизм. В сравнении с 2016 годом это слово начали искать на 70% чаще. Эксперты отмечают, что интерес людей к этому слову был связан не только с прошедшими в разных городах женскими маршами, но и с популярной культурой. В 2017 вышел сериал «Рассказ служанки» и фильм «Чудо-женщина», после которых люди стали чаще запрашивать feminism.

2018: Justice

В 2018 году больше всего людям хотелось правосудия и справедливости. У этого слова стало на 74% больше запросов, чем в 2018. При этом, слово justice в английском в статьях на соответстующие темы может означать ещё и судью, и сокращённый вариант для написания Министерство юстиции США (the Department of Justice).

2019: They

Местоимение they привлекло внимание словаря Merriam-Webster на 4 года позже, чем Американское Диалектическое Общество. К 2019 году местоимение для гендерно-небинарных персон стало сложно игнорировать, потому что оно уже активно используется в медиа и общественном дискурсе.

Выбор Oxford English Dictionary

2015: 😂

В 2015 году словом года впервые стал смайлик. Официально он называется “лицо со слезами радости”. Конечно, к 2015 году эмодзи редко кого-то можно было удивить, они начали появляться ещё в конце 1990-х. Но эксперты отмечают, что само слово «эмодзи» в 2015 году стало гораздо более популярным. А смайлик, который плачет от смеха, в 2015 году использовался больше других — 20% от использования всех эмодзи в Великобритании (по сравнению с 4% в 2014 году) и 17% в США (в 2014 — 9%).

2016: post-truth

Прежде чем в 2017 людей начали волновать фейковые новости, их волновала «постправда». В 2016 году происходили два события, из которых до сих пор черпают самые красноречивые примеры политики постправды — выборы в США и референдум о выходе из ЕС в Великобритании. Мы живем в обществе постправды, об этом много говорят, но что это действительно значит? Это ситуация, когда люди опираются на аргументы, построенные на эмоциях, а не на фактах. На этом же строятся и фейковые новости, они вызывают мгновенную эмоциональную реакцию, там нет скучной статистики, они не взывают к вашему критическому мышлению. Когда вы в последний раз действительно перепроверяли информацию из медиа? Политики и медиа часто пользуются тем, что в бесконечном потоке информации люди устали отделять зерна от плевел. Так мы оказываемся в ситуации постправды, когда факт сам по себе имеет меньшее значение, чем эмоции, которые он вызывает. Так многие политики продолжают придерживаться заведомо ложных аргументов даже после разоблачения.

2017: youthquake

Youthquake в 2017 стали вбивать в поисковые запросы в 5 раз чаще, чем в предыдущем году. Это необычное слово состоит из двух частей: youth (переводится как «молодость», «юность») и quake («дрожь», иногда сокращение от «землетрясение»). По определению словаря, это серьёзные культурные, политические или социальные изменения, произошедшие под влиянием молодых людей. Само слово совсем не новое: его придумала редактор Vogue Диана Вриланд, и youthquake было в широком употреблении в 1960-х, но тогда обычно упоминалось в контексте моды и культуры. В 2017 году слово снова стало использоваться в медиа, но в контексте политической активности молодёжи — активного участия в выборах, поддержки кандидатов в социальных медиа преимущественно молодой аудиторией.

2018: toxic

Прилагательное «токсичный» стало словом года и с тех пор прочно закрепилось в языке и, похоже, не собирается никуда уходить. Уверены, вы уже не раз встречались с ним и в русском языке. В буквальном смысле toxic означает «ядовитый», «отравляющий». В 2018 году произошло резонансное событие — в Великобритании были отравлены бывший сотрудник ГРУ Сергей Скрипаль и его дочь Юлия. Об этом много писали медиа, и слово стало чаще появляться в поиске. Кроме того, в последние несколько лет слово toxic стали активнее использовать в переносном смысле, что увеличило количество запросов в словаре по этому слову на 45%. Самыми частыми сочетаниями стали toxic chemical (токсичный химикат), toxic masculinity (токсичная маскулинность), toxic substance (отравляющее вещество), toxic gas (токсичный газ), toxic environment (токсичная среда — обычно так говорят про работу), toxic relationship (токсичные отношения).

2019: climate emergency

Здесь Оксфордский словарь практически солидарен с Collins English Dictionary и выбирает словом года climate emergency — чрезвычайная климатическая ситуация. Словарь определяет значение этого выражения так: «ситуация, в которой необходимо срочное действие, чтобы снизить или приостановить климатические изменения и избежать потенциально необратимого вреда окружающей среде». Само слово «климат» стало гораздо более заметным в медийном дискурсе, а генеральный секретарь ООН Антониу Гутерреш назвал климатические изменения — одной из главных проблем нашего времени. Так выражение climate emergency в 2019 году стали использовать в 100 раз чаще, чем в предыдущем году.

Слово года — это акция не только про лингвистические изменения, новые или популярные слова, но и про существенные для культуры явления. Поэтому если вы учите английский язык и хотите лучше понимать, что волнует современных британцев и американцев, стоит получше в них разобраться. В Glossika вы сможете учить английский язык, опираясь на современную лексику и выражения, которые записаны носителями языка и звучать естественно.

1 day left of 2015 and I think it’s time to talk about Russian word of the year.

There are four nominations: «The word of the year», «The phrase of the year», «Anti-language», «The modernism of the year»

Russian word of the year 2016

The noun «беженцы» (refugees) became the word of the year 2016.

It is interesting to know top 5 of words in еры category.

- «санкции/антисанкции» ( sanctions/anti-sanctions)

- «война» (war)

- «терроризм» (terrorism)

- обращение-мем «Карл» ( mem Carl)

The phrase of the year

In this nomination the phrase «Немцов мост» (the bridge of Nemtsov) won. This phrase became the second name of the Большой Москворецкий мост ( on of the central bridges in Moscow) where Boris Nemtsov was killed.

Top 5 of phrases in this category:

- образование ИГИЛ (formation of ISIS)

- «атмосфера ненависти» (the atmosphere of hate)

- «Бессмертный полк» (the Immortal Regiment)

- «Минские договоренности» ( Minsk agreements)

«Anti-language»

In this nomination the dirty-phrase «Обама чмо» won.

This phrase became the symbol of attitude of Russian people towards everything foreign.

Top 5 words/phrases in this category were:

- «ватник» (cotton wadded jacket)

- «вашингтонский обком» (Washington «obkom» — obkom- is the abbreviation of Regional Committee during the Soviet times)

- «иноагент» (abbreviation of «иностранный агент» foreign agent)

- «наши западные партнеры» (our western partners)

The main word- neologism of the year was invented by the writer Andrey Desnitsky) and this phrase is «бессмертный барак» ( The Immortal Barracks)

Source: https://tvrain.ru/words2016/

Last week, the independent television station TVRain (Dozhd) published a list of the 2016 Russian words of the year. Some of them come from major news stories and cultural trends, while the others are related to derivative memes and random social media fights. RuNet Echo has explained many of the words and trends in previous posts (scroll to the bottom of the page for the full list), but here are a few of the words that have been undeservingly neglected. Like many words in Russian, they can be explained but not quite translated.

Море китов (The Sea of Whales)

In May, the newspaper Novaya Gazeta published a piece by Galina Mursaliyeva about “death groups” on the Russian social network VKontakte. Mursaliyeva was able to trace a spate of teen suicides to certain online groups that are notable for their depressing aesthetic—in particular, images of whales that are supposedly going to kill themselves because they do not want to grow old. Mursaliyeva accused administrators of these groups of recruiting depressed children and pushing them to suicide by depriving them of sleep and describing how exactly they should take their own lives. She also advised parents of teenagers to closely monitor their online activity.

Mursaliyeva’s article was harshly criticized by some of her colleagues for making the psychological state of teenagers worse by putting them under surveillance. In December, the Irkutsk Investigative Committee published instructions for parents that contained many of Mursaliyeva’s “red flags” for suicide-related online activity.

Аэропорт Внуково (Vnukovo Airport)

Beginning in June 2016, GPS navigators started going crazy when they came close to the Kremlin, where the Russian president lives in Moscow. They displayed the location of the Kremlin as “Vnukovo Airport,” which is 37 kilometers away. Internet users figured out the glitch pretty soon: the FSO (Federal Protective Service) was meddling with GPS devices to prevent drones from flying around the Kremlin (another, less convincing, explanation has something to do with a potential rocket attack on the Kremlin and a new world war). The fallout from the security measure infuriated Muscovites, who were left with enormous Uber bills, wrong fitness tracker stats, and, worst of all, an inability to catch Pokemons.

Бирюлевская саранча (Locust from Biryulyovo)

This one is an example of a very local conflict that went viral on social media. Patriarshiye Prudi is a nice residential area in the center of Moscow that became a pedestrian zone in 2016. Patriki had always been a place that attracted lots of rif raf, but this year the situation got much worse. But well-to-do local citizens were not about to suffer in silence: they flooded Facebook and some urban magazines with posts and columns criticizing “the locust from Biryolyovo,” referring to one of the least pleasant parts of Moscow. Despite being mocked on Twitter and Facebook, they managed to pull some strings and get their way. Currently, every shop and bar in Patriki must close by 11 pm, so the aforementioned “locust” has nothing to do but go back to Biryulyovo.

Монеточка (Monetochka)

Monetochka became a Russian Internet sensation at the very beginning of 2016. At the time, Monetochka, whose real name is Liza, was a high school student from Yekaterinburg. She sang witty little songs with plenty of references to fashion, RuNet culture, politics, and her schoolmates. Here’s one of her videos with a song about the online life of a modern Russian schoolgirl.

Liza currently lives in Moscow, where she is a student at the All-Russian State Institute of Cinematography. She still performs at some parties, but the hype is over—at least for now.

ЛСДУЗ and ЙФЯУ9

These two unpronounceable combinations of letters and numbers became popular after Alexey Navalny, a Russian opposition politician and anti-corruption activist, found them in Rosreestr (Federal Agency for State Registration, Cadastre, and Cartography) records. Navalny pointed out that the names of the owners of several luxury real estate holdings that used to belong to the sons of Russian Attorney General Yuri Chayka had changed to ЛСДУЗ and ЙФЯУ9. Navally assumed that this was done in an attempt to protect the privacy of Artyom and Igor Chayka, reminding his readers that information about property belonging to high officials’ relatives has disappeared from Rosreestr records.

Readers of Navally’s popular blog made some pretty funny comics and collages describing the situation, and Meduza, an independent media outlet based in Riga, Latvia, launched a game that showed everyone how their names would look in Rosreyestr.

“What’s your son’s name?”

“ЛСДУЗ ЙФЯУ9″

Somewhere in the depths of the Russian General Prosecutors Office

Source: various social media websites

Dozhd’s 2016 Words of the Year that have been previously explained by Runet Echo:

Rusiano (Русиано), Vaper (Вейпер), and “There Is Just No Money, But Hang in There” (Денег нет, но вы держитесь)

Zabivaka the Wolf (Забивака)

Pokemon GO

#IAmNotAfraidToSay (#ЯНеБоюсьСказать)

How was the swim? (Как поплавали?)

FindFace

Neural Networks (Нейросети)

Wearing Louboutin Shoes (На Лабутенах)

Telegony (Телегония)

The number one cause for suicide is untreated depression. Depression is treatable and suicide is preventable. You can get help from confidential support lines for the suicidal and those in emotional crisis. Visit Befrienders.org to find a suicide prevention helpline in your country.

In this age of misinformation—of “fake news,” conspiracy theories, Twitter trolls, and deepfakes—gaslighting has emerged as a word for our time.

A driver of disorientation and mistrust, gaslighting is “the act or practice of grossly misleading someone especially for one’s own advantage.” 2022 saw a 1740% increase in lookups for gaslighting, with high interest throughout the year.

Its origins are colorful: the term comes from the title of a 1938 play and the movie based on that play, the plot of which involves a man attempting to make his wife believe that she is going insane. His mysterious activities in the attic cause the house’s gas lights to dim, but he insists to his wife that the lights are not dimming and that she can’t trust her own perceptions.

When gaslighting was first used in the mid 20th century it referred to a kind of deception like that in the movie. We define this use as:

: psychological manipulation of a person usually over an extended period of time that causes the victim to question the validity of their own thoughts, perception of reality, or memories and typically leads to confusion, loss of confidence and self-esteem, uncertainty of one’s emotional or mental stability, and a dependency on the perpetrator

But in recent years, we have seen the meaning of gaslighting refer also to something simpler and broader: “the act or practice of grossly misleading someone, especially for a personal advantage.” In this use, the word is at home with other terms relating to modern forms of deception and manipulation, such as fake news, deepfake, and artificial intelligence.

The idea of a deliberate conspiracy to mislead has made gaslighting useful in describing lies that are part of a larger plan. Unlike lying, which tends to be between individuals, and fraud, which tends to involve organizations, gaslighting applies in both personal and political contexts. It’s at home in formal and technical writing as well as in colloquial use:

Patients who have felt that their symptoms were inappropriately dismissed as minor or primarily psychological by doctors are using the term “medical gaslighting” to describe their experiences and sharing their stories.— The New York Times, 28 March 2022

The “I’m sorry you feel that way” approach, along with avoiding an argument in lieu of admitting fault, is good old fashioned gaslighting. — Psychology Today, 29 March 2022

My Committee’s investigation leaves no doubt that, in the words of one company official, Big Oil is ‘gaslighting’ the public. These companies claim they are part of the solution to climate change, but internal documents reveal that they are continuing with business as usual. — Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney, Chairwoman of the Committee on Oversight and Reform, 14 September 2022

After their fight awkwardly cleared the daybed, the two parted ways and Genevieve caught Victoria up on the unexpected blowout. “He told me I’m gaslighting him. I’ve never even been told that in my life,” Gen said. “Yeah that’s a big word to use… He doesn’t know what that means. He’s just using a buzzword, he’s stupid. He’s dumb,” Victoria replied. — Nicole Gallucci, Decider (decider.com), 2 November 2022

English has plenty of ways to say “lie,” from neutral terms like falsehood and untruth to the straightforward deceitfulness and the formally euphemistic prevarication and dissemble, to the innocuous-sounding fib. And the Cold War brought us the espionage-tinged disinformation.

In recent years, with the vast increase in channels and technologies used to mislead, gaslighting has become the favored word for the perception of deception. This is why (trust us!) it has earned its place as our Word of the Year.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, countries including the U.S. and United Kingdom placed sanctions on Russian oligarchs and their families. Lookups for oligarch spiked 621% in early March 2022.

In its Greek roots oligarchy literally means “rule by the few.” In English the word can carry the same meaning, but it also has a meaning specific to Russia and other countries that succeeded the Soviet Union:

: one of a class of individuals who through private acquisition of state assets amassed great wealth that is stored especially in foreign accounts and properties and who typically maintain close links to the highest government circles

Throughout 2022 we have seen stories about various authorities seizing the yachts owned by these rich Russian allies of President Putin.

The war in Ukraine has also driven spikes in lookups for sanction, Armageddon, and conscript.

The World Health Organization uses Greek letters (alpha, beta, gamma, delta) to designate variants of the COVID virus. In November 2021, it used omicron, the 15th letter of the Greek alphabet, to name the most recent version of the virus. That variant became one of the most widespread forms of COVID in 2022.

Major spikes in lookups accompanied a surge in cases in early January, and following reports in November that the omicron booster was not significantly more effective than the older vaccines.

Endemic, used to describe a disease that is constantly present in a particular place, increased 874% in January.

Photo: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Lookups for codify increased 193% for the year in 2022, driven by the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade on June 24th.

Codify refers to a process by which Congress can make laws; the word literally means “to make a code” with code here essentially a synonym of “law.” Code ultimately comes from the Latin word codex, meaning “trunk of a tree,” referring to documents on wooden tablets.

There were several notable spikes in lookups of codify:

May 3 (leak of the draft of the Dobbs v. Jackson decision): 5347%

June 24 (the decision announcement): 1293%

June 30 (President Biden’s endorsement of ending the filibuster in order to codify the right to abortion): 8304%

We also saw spikes in other lookups connected to this story: abortion lookups were higher in June, and both take for granted and mercurial, used to describe Chief Justice John Roberts, were higher in May.

The acronym LGBTQIA adds some letters to the older and more familiar abbreviations LGBT and LGBTQ, with the full abbreviation standing for “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (one’s sexual or gender identity), intersex, and asexual/aromantic/agender.”

The abbreviation was looked up frequently (up 1178%) during the entire month of June, Pride month, when the rights, equality, and culture of LGBTQ people are celebrated around the world. Lookups also spiked in late November after the shooting at a gay nightclub in Colorado Springs. With LGBTQ and the longer acronym both used in news stories about the event, interest in the difference between the two was apparent. Overall, LGBTQIA saw an 800% increase over 2021.

In June, when a Google engineer claimed the company’s AI chatbot had developed a human-like consciousness, lookups of sentient increased 480%. The claim was vigorously denied by Google, and the engineer was placed on paid leave, but the question of how human-like AI is, or will be, became a topic of much interest.

Loamy

2022 was also the year that many people discovered the joy in puzzling out five-letter words: both Wordle (in which the puzzler has six tries to identify one word) and Quordle (nine guesses to identify four words) sent people to the dictionary, with numerous seldom-searched-for words tapped out on keyboards everywhere. When loamy (“consisting of loam, a soil consisting of a friable mixture of varying proportions of clay, silt, and sand”) was a Quordle answer on August 29th, the entry surged 4.5 million percent. In May, the Quordle answer voilà inspired a lookup spike of 2.5 million percent.

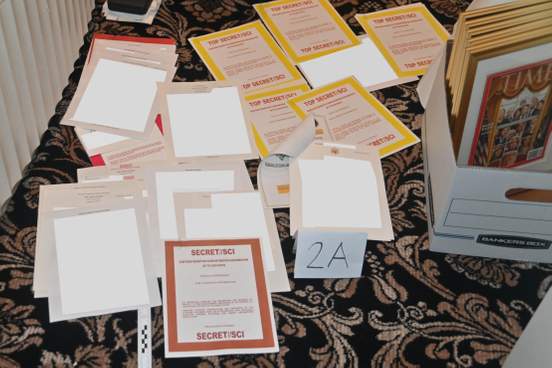

Photo: United States Department of Justice

When the FBI executed a search warrant at former president Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home in early August, the event was labeled by some as a “raid,” sending lookups of raid up 970%. The relevant meaning of raid, “a sudden invasion by officers of the law,” was used to suggest that the search was unfair. In late August the Justice Department responded to that charge by releasing a redacted affidavit, sending lookups of redact and redacted up 1000%.

For the remainder of the year, this story created additional spikes in lookups. The large quantity of documents—33 boxes’ worth—was often called a “trove” by journalists, a trove being a valuable collection, or more generally a large amount of something collected. Trove was up 344% for the year. Defenders of the former president accused the government of behaving like a banana republic—that is, like a small and despotically run country, driving a lookup increase of of 3750%.

The death of Queen Elizabeth II was the end of an era, and the focus of international attention and fascination. The public’s interest in the monarchy is often connected with the ceremonies and rituals of the institution, including coronations, royal weddings—and funerals. Among the most looked-up terms following the Queen’s death was pomp and circumstance, as images of processions and pageantry were broadcast around the world. Monarch itself was also looked up frequently.

Announcements of the Queen’s death acknowledged the new King and his wife, Camilla, referred to by her proper title of Queen Consort, and that term quickly shot to the top of lookups. Since England had not had a king since 1952, it’s understandable that this title was unfamiliar. Camilla is not the successor to the Queen, but is instead the wife of the reigning king. A parallel title for the husband of a reigning queen, prince consort, was the title held by the late Prince Philip.

Another royal milestone sent people to the dictionary in May and June to look up jubilee, meaning “a special anniversary.” The term described the official celebrations for Queen Elizabeth’s unprecedented 70th anniversary on the throne.

The Oxford Corpus lists many vivid examples of goblin mode, including “Goblin mode is like when you wake up at 2am and shuffle into the kitchen wearing nothing but a long t-shirt to make a weird snack, like melted cheese on saltines”, as quoted in The Guardian newspaper. More recently, an opinion piece in The Times stated that “too many of us… have gone ‘goblin mode’ in response to a difficult year.”

Speaking at a special event to announce this year’s approach to selecting the Oxford Word of the Year, Ben Zimmer, American linguist and lexicographer, said: “Goblin Mode really does speak to the times and the zeitgeist, and it is certainly a 2022 expression. People are looking at social norms in new ways. It gives people the license to ditch social norms and embrace new ones.”

Since the launch of the people’s choice vote, ‘goblin mode’ has captured the attention of many communities online, having been a runaway favourite on social media and within online publications, such as PC Gamer, which urged followers to “put aside [their] petty differences and vote for ‘goblin mode’.”

Casper Grathwohl, President, Oxford Languages, says:

“We were hoping the public would enjoy being brought into the process, but this level of engagement with the campaign caught us totally by surprise. The strength of the response highlights how important our vocabulary is to understanding who we are and processing what’s happening to the world around us. Given the year we’ve just experienced, ‘Goblin mode’ resonates with all of us who are feeling a little overwhelmed at this point. It’s a relief to acknowledge that we’re not always the idealized, curated selves that we’re encouraged to present on our Instagram and TikTok feeds. This has been demonstrated by the dramatic rise of platforms like BeReal where users share images of their unedited selves, often capturing self-indulgent moments in goblin mode. People are embracing their inner goblin, and voters choosing ‘goblin mode’ as the Word of the Year tells us the concept is likely here to stay.”