I always refer to Caltech’s small size as being very similar to the size effect that exists in materials — there are special properties that exist when you are extremely small

If one were to reduce the story of the California Institute of Technology to numbers, it would be difficult to know where to start.

It is 123 years old, boasts 57 recipients of the US National Medal of Science and 32 Nobel laureates among its faculty and alumni (including five on the current staff).

It is the world’s number one university – and has been for the past three years of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings – and has just 300 professorial staff.

In short, it is tiny, and it is exceptionally good at what it does.

Ares Rosakis, chair of the Division of Engineering and Applied Science, describes Caltech as “a unique species among universities…a very interesting phenomenon”. “Very interesting” may be something of an understatement.

Caltech’s neat and unassuming campus sits in a quiet residential neighbourhood in Pasadena, in the shadow of the San Gabriel Mountains.

Although it is only 15 miles away from Hollywood, the Tinseltown razzmatazz seems a world away.

But Caltech can lay claim to its own galaxy of stars. Among a long and illustrious list of former faculty is Charles Richter, inventor of the scale that quantifies the magnitude of earthquakes (handy in Southern California) and Theodore von Kármán, the first head of what is now Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He nurtured the pioneering “rocket boys” who risked ridicule in the 1930s as they brought space rockets from the pages of science fiction comics into the real world. The heavy hitters on the current staff include Mike Brown, the man who “killed Pluto” (when his work led to its being downgraded to a dwarf planet), and John Schwarz, who in December 2013 was named a joint winner of the $3 million (£1.8 million) 2014 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics.

It is clear that Caltech is a special place, but how has it achieved this success? Rosakis’ first answer focuses on its size.

“I always refer to this small size as being very similar to the size effect that exists in materials – there are special properties that exist when you are extremely small,” he explains in his airy office, the winter sun streaming through a bank of windows on to a chalkboard filled with mathematical formulae.

Working alongside the 300 professorial faculty are about 600 research scholars and, at the last count, 1,204 graduate students and just 977 undergraduates. The private not-for-profit university’s freshman “class of 2017” consists of a mere 249 students.

While diminutive scale may be a disadvantage for some institutions, for Caltech, it is at the heart of its being, and perhaps the single most important aspect of its extraordinary global success.

Crucially, it means that Caltech is obliged to be interdisciplinary in its “mode of operation – whether we like it or not”, observes Rosakis.

“I have 77 faculty in engineering and applied science. MIT [the Massachusetts Institute of Technology] has 490. How can I compete with an excellent place like MIT? We have to have engineers interact with all of the sciences and vice versa – it is a matter of survival. We don’t have the breadth to do things in a big way unless they interact.”

If Caltech’s size demands that its faculty work across traditional disciplinary boundaries to survive, it also makes such interaction exceptionally easy and natural.

While it may sound like a cliché, at Caltech exciting interdisciplinary ideas really are generated over a cup of coffee in the campus cafe, according to faculty.

Fiona Harrison, Benjamin M. Rosen professor of physics and astronomy, has worked with colleagues in aeronautical engineering, applied physics and many other disciplines.

“You run into them at the coffee shop and start a conversation, and it turns out you are both thinking about some similar technology – and so this cross-fertilisation is natural to the culture, to the fabric of the place,” she says.

“There are arguments that there are some things that you have to be big to do. But ultimately there’s a feeling that there’s something unique about this environment and you don’t want to destroy that.”

Of course, this does mean that hard choices must be made and some areas of research will remain out of bounds in order to focus resources.

But, says Harrison, “at Caltech we have a saying – if the field’s been around for a while then Caltech shouldn’t do it, because we should be inventing the next fields”.

The interdisciplinary culture was demonstrated in late 2013 when the Division of Biology (founded in 1928 by the Nobel prizewinning geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan) was transformed into a new Division of Biology and Biological Engineering.

The change came after what division chair Steve Mayo describes as the faculty-led “organic drift” of the Division of Engineering and Applied Science’s bioengineering department into synthetic biology – looking more at manipulating biological materials.

“We felt it was better to connect that activity to biology and to emphasise the underlying biological emphasis of the engineering activity,” says Mayo, who is Bren professor of biology and chemistry.

Freed from the administrative barriers that they might face elsewhere, he adds, the researchers in his division “can interact in ways that lead to unique things happening”.

Another crucial factor in Caltech’s success that is also fundamentally related to its size is its extremely selective academic recruitment strategy, Mayo suggests.

“We don’t hire that many faculty each year. In many cases we have faculty searches in a particular area where it may take us several years to find the appropriate person to bring in.

“We’ve been extremely careful about how we hire faculty, and we are fully committed to the success of those faculty once they are here.”

Rosakis is much more blunt: “I cannot make mistakes when I hire. I really cannot. We have 16 faculty members in Information Science and Technology – Carnegie Mellon [University in Pittsburgh, a highly ranked research institution] has 200. If I make one hire or two hires that are wrong, I have a huge setback.

“If you ask me what is more important, to get $100 million into my division or to hire 10 faculty members who are the best, I would say to hire those 10 faculty members.

“Our main purpose of achieving excellence is attracting the best human talent. If we have the best human talent, then the $100 million will come, because they will be winners in writing grants, they will excite philanthropic donors to give Caltech funding and they will increase the visibility of the whole institute.”

What this means is that decision-makers at Caltech spend “an enormous amount of time making sure that we identify the best available and have the resources to attract them”, Rosakis continues.

“We take our hiring to be our first priority. We hire people and we give them everything they need to succeed. Other places would hire three or four people for the same position and let them compete. We trust that we have made a good choice, and we give them enough gold so that they cannot say that they failed [for lack of] material resources.”

Harrison, who came to Caltech as a postdoc and joined the faculty two years later, emphasises the willingness of the institute to put faith in young researchers.

No one comes here saying, ‘I want to start a company.’ They come because they want to benefit from the great, open, interdisciplinary environment — to do fundamental work

“We’ve all heard the ‘publish or perish’ mantra, but Caltech invests in young people. It said to me: ‘OK, you can take a risk.’ ”

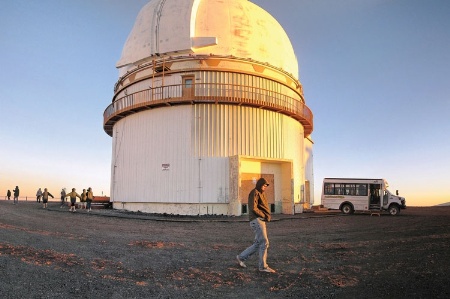

Harrison’s risk paid off. Having developed its instrumentation, she is now principal investigator for Nasa’s NuSTAR Explorer Mission (nuclear spectroscopic telescope array) – which has deployed orbiting telescopes using high-energy X-rays to study black holes. She also chaired the faculty search committee that selected Caltech’s next president, physicist and current University of Chicago provost Thomas F. Rosenbaum, who will take up the post in July.

Money, of course, is also crucial, and one of the few things about Caltech that is not small in scale is its endowment – currently valued at about $1.8 billion.

Caltech’s most prominent benefactors are Gordon Moore – co-founder of the chip manufacturer Intel, who received his PhD from Caltech in 1954 – and his wife, Betty.

In 2001, they gave $600 million (half from the couple’s foundation, and half from them personally). “Moore gave a large sum, and it was a very unusual gift because he said he wanted a good fraction of it to go to innovative research – to doing the things that the government will not fund,” says Harrison. “If you want to create a new field and there’s no place to apply for funding, you can do it at Caltech.”

But it is not just about money – attitude is also key.

“I never heard ‘Well, you better just write papers’, and I think that attitude really pervades at Caltech – an element of accepting risk for big pay-off,” Harrison says.

“It is more important to do something that’s new than just to crank out the papers. It is not about the numbers or the citation index, it’s about looking beyond that and looking at what is new and truly different. Maybe that comes from a certain amount of self-confidence that the institution has. I think many places are very conscious of being judged by the outside, but Caltech doesn’t have that.”

This self-confidence has also allowed Caltech to resist rising pressure from governments and funders to place much more emphasis on the application of research for clear, visible economic impact, at the expense of fundamental, curiosity-driven exploration.

For a science and technology institution, it can be a delicate balance – but at Caltech the focus is resolutely blue-sky first.

Mayo explains: “No one comes to Caltech saying, ‘I want to start a company.’ They come because they want to benefit from the great, open, interdisciplinary environment – to do fundamental work. If they happen to have breakthroughs or discoveries with an application, then commercialisation is a side benefit.

“There’s an unfortunate trend in the funding of science and engineering that focuses on ‘what are we going to get out of this in terms of application’ as opposed to ‘let’s enable the broad-based fundamental activity that has been demonstrated historically to lead to the kind of technological breakthroughs that become the dominant technologies in the world’.”

So although the focus is on fundamental research, Caltech is perfectly happy to allow the fruits of that labour to be exploited.

“It is often the case that breakthroughs at the basic level have profound implications for technologies that affect real people,” says Mayo. “So certainly at Caltech we do not shy away from pursuing those applications.”

As breakthroughs evolve into applications, Caltech is careful to create firewalls between blue-sky research and commercial activity, but it has a strong environment to facilitate technology transfer, primarily through off-campus spin-off companies.

“Caltech is very open and makes setting up such companies relatively easy compared with other academic institutions,” Mayo explains. “There’s an explicit attempt to make that transition as painless as possible, unlike many institutions that either have barriers put in place on purpose or have bureaucratic impediments to the transfer of technology.”

The breaking-down of barriers – both disciplinary and bureaucratic – is a recurring theme, and it was central to luring Markus Meister to Caltech after 20 years at Harvard University – that, and a purpose-built, state-of-the-art laboratory and office with one of the best views on campus.

“The biggest difference [between Caltech and Harvard] is that this is a small institution organised in a very simple way,” says Meister, who earned his PhD at Caltech in 1987 and is now Lawrence A. Hanson, Jr. professor of biology. “It is way easier to get things done than at Harvard.”

Within months of his arrival in July 2012, Meister had set in motion plans for a new graduate programme in neurobiology, and recruitment for it is already under way.

“Within a few months of starting to talk about it, it was approved and in the catalogue and ready to go,” he says. “Starting a new PhD programme at Harvard University would be a three-year project by the time you get all the interest-holders informed and on your side and move obstacles out of the way.

“I have found this past year somehow a lot more effective in how I use my time. When you have a good idea and get people convinced, the step from there to actually seeing it happen is very short. Really staying lean and keeping the bureaucracy shallow is a huge value.”

He marvels at the fact that at Caltech he can pick up the phone to the provost, get through and receive quick answers.

“There are fewer people involved in any given decision, and the ones who make the decisions you can actually get on the phone – and it still feels like it is driven by the faculty.”

Caltech’s Institute Academic Council is where many of the key decisions – faculty promotions, salaries, new hires, funding priorities – are made. It consists of the chairs of Caltech’s six academic divisions and the provost and president, who meet for a full day once a month.

All senior administrators remain research-active (“you will not be respected by your faculty if you are considered an empty suit,” says Rosakis) and all are closely involved in each division’s activities.

The structure is simple, flat and flexible. “I would describe the boundaries between divisions as semi-permeable membranes,” says Rosakis. And this prevents the development of silos. “It is one thing to be interdisciplinary intellectually and another thing to be interdisciplinary in terms of resources,” he says. “Resources cross boundaries here – this is usually when people become protective – and that is very important.”

The factors driving Caltech’s extraordinary success thus seem quite simple: it stays deliberately small, resolutely interdisciplinary, exceptionally selective when hiring, and maintains a flat, flexible management system.

But with imitators emerging around the world, and a drive among developing nations to develop world-class institutions quickly, is it a formula that can be replicated?

“I don’t think we have any real secrets,” says Mayo. “The challenge would be getting this sort of system implemented somewhere else. Caltech exists in the way it does probably in many respects as a fluke of history. Its culture has evolved over decades. If you wanted to set up something new and hire several hundred faculty in order to put a new institution together, it is going to be really hard to find 300 excellent faculty who are going to work in a new environment.”

Harrison concurs. “My sense is that the Caltech culture is something that you get after you’ve been here for a while. I’ve known a number of people who leave for Harvard or MIT and they end up coming back because there is something different about the culture. I don’t know if you could instil it from the top down,” she says.

“You can walk into your division chair’s office and say ‘I have this great idea’ or ‘I want to switch fields and here’s why’, and typically the attitude of the administration is to support that. In most universities the faculty think they run the place, but here it may be closer to the truth.”

Honour bound: why Caltech takes its students on trust

The fact that student exams at Caltech are regularly taken at home, and are never supervised, or proctored, is emblematic of a teaching environment based on an extraordinary degree of trust.

Caltech’s “Honor Code” is short and simple: “No member of the Caltech community shall take unfair advantage of any other member of the Caltech community.” But as the institution points out in its undergraduate literature, this statement has far-reaching implications. “It means, for instance, that Caltech students are routinely given 24-hour access to labs, workshops, and other facilities on campus…that collaboration on homework and other assignments is not just encouraged, it’s practically essential for success.” And it means that students are trusted absolutely not to cheat on exams.

“The expectation is that students will follow the rules without being proctored. Proctoring is not part of the repertoire – many of the finals are take-home,” says Markus Meister, Lawrence A. Hanson, Jr. professor of biology at Caltech.

Meister was himself a Caltech student 30 years ago, and he remembers the huge degree of trust placed in him and his fellow students.

“I took a lot of take-home exams – it is a challenge to complete stuff in three hours and usually you don’t finish, so you draw a line and say ‘this is where I got to in three hours’ and then you continue. The teaching fellow might only give you credit for what you did in the three hours.”

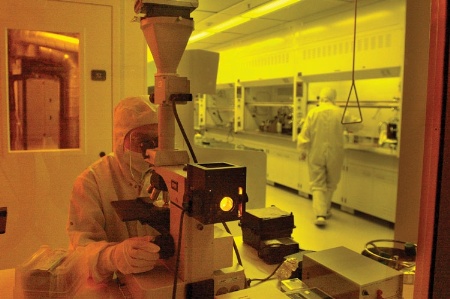

Caltech boasts an intimate teaching environment – there is a student to faculty ratio of just 3:1, and undergraduates, including first-years, regularly spend their summers working in university laboratories under a fellowship scheme.

Meister believes that cheats simply cannot prosper in an environment that includes such small-group teaching and close collaboration with colleagues because they would rapidly be exposed.

As the university says: “The Honor Code confers the power to freely choose responsible actions. Caltech students value this freedom highly and guard it fiercely, which is why the system actually works.”

number one

noun

uk

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 audio

/ˌnʌm.bə ˈwʌn/ us

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 audio

/ˌnʌm.bɚ ˈwʌn/

number one noun

(YOURSELF)

[ U ] informal (US also numero uno)

yourself and no one else:

I’m going to look out for number one (= take care of myself only).

SMART Vocabulary: related words and phrases

number one noun

(THE BEST)

SMART Vocabulary: related words and phrases

number one noun

(TOILET)

(Definition of number one from the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus © Cambridge University Press)

number one | American Dictionary

number one

us

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 audio

/ˈnʌm·bər ˈwʌn/

She’s still number one in tennis.

(Definition of number one from the Cambridge Academic Content Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

number one | Business English

number one

uk

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 audio

us

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5 audio

(Definition of number one from the Cambridge Business English Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

The alma mater, meaning «nourishing mother» in Latin, is one of the most enduring symbols of the university. The phrase was first used to describe the University of Bologna, Italy, founded in 1088.

A university (from Latin universitas ‘a whole’) is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the designation is reserved for colleges that have a graduate school.

The word university is derived from the Latin universitas magistrorum et scholarium, which roughly means «community of teachers and scholars».[1]

The first universities in Europe were established by Catholic Church monks.[2][3][4][5][6] The University of Bologna (Università di Bologna), Italy, which was founded in 1088, is the first university in the sense of:

- Being a high degree-awarding institute.

- Having independence from the ecclesiastic schools, although conducted by both clergy and non-clergy.

- Using the word universitas (which was coined at its foundation).

- Issuing secular and non-secular degrees: grammar, rhetoric, logic, theology, canon law, notarial law.[7][8][9][10][11]

History[edit]

Definition[edit]

The original Latin word universitas refers in general to «a number of persons associated into one body, a society, company, community, guild, corporation, etc».[12] At the time of the emergence of urban town life and medieval guilds, specialized «associations of students and teachers with collective legal rights usually guaranteed by charters issued by princes, prelates, or the towns in which they were located» came to be denominated by this general term. Like other guilds, they were self-regulating and determined the qualifications of their members.[13]

In modern usage the word has come to mean «An institution of higher education offering tuition in mainly non-vocational subjects and typically having the power to confer degrees,»[14] with the earlier emphasis on its corporate organization considered as applying historically to Medieval universities.[15]

The original Latin word referred to degree-awarding institutions of learning in Western and Central Europe, where this form of legal organisation was prevalent and from where the institution spread around the world.[citation needed]

Academic freedom[edit]

An important idea in the definition of a university is the notion of academic freedom. The first documentary evidence of this comes from early in the life of the University of Bologna, which adopted an academic charter, the Constitutio Habita,[16] in 1155 or 1158,[17] which guaranteed the right of a traveling scholar to unhindered passage in the interests of education. Today this is claimed as the origin of «academic freedom».[18] This is now widely recognised internationally – on 18 September 1988, 430 university rectors signed the Magna Charta Universitatum,[19] marking the 900th anniversary of Bologna’s foundation. The number of universities signing the Magna Charta Universitatum continues to grow, drawing from all parts of the world.

Antecedents[edit]

Moroccan higher-learning institution Al-Qarawiyin (founded in 859 A.D.) was transformed into a university under the supervision of the ministry of education in 1963.[20]

An early institution often called a university is the Harran University, founded in the late 8th century.[21] Scholars occasionally call the University of al-Qarawiyyin (name given in 1963), founded as a mosque by Fatima al-Fihri in 859, a university,[22][23][24][25] although Jacques Verger writes that this is done out of scholarly convenience.[26] Several scholars consider that al-Qarawiyyin was founded[27][28] and run[20][29][30][31][32] as a madrasa until after World War II. They date the transformation of the madrasa of al-Qarawiyyin into a university to its modern reorganization in 1963.[33][34][20] In the wake of these reforms, al-Qarawiyyin was officially renamed «University of Al Quaraouiyine» two years later.[33]

Some scholars, including George Makdisi, have argued that early medieval universities were influenced by the madrasas in Al-Andalus, the Emirate of Sicily, and the Middle East during the Crusades.[35][36][37] Norman Daniel, however, views this argument as overstated.[38] Roy Lowe and Yoshihito Yasuhara have recently drawn on the well-documented influences of scholarship from the Islamic world on the universities of Western Europe to call for a reconsideration of the development of higher education, turning away from a concern with local institutional structures to a broader consideration within a global context.[39]

Medieval Europe[edit]

The modern university is generally regarded as a formal institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian tradition.[40][41]

European higher education took place for hundreds of years in cathedral schools or monastic schools (scholae monasticae), in which monks and nuns taught classes; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the 6th century.[42]

In Europe, young men proceeded to university when they had completed their study of the trivium – the preparatory arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic or logic–and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

The earliest universities were developed under the aegis of the Latin Church by papal bull as studia generalia and perhaps from cathedral schools. It is possible, however, that the development of cathedral schools into universities was quite rare, with the University of Paris being an exception.[43] Later they were also founded by kings (University of Naples Federico II, Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Kraków) or municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period, most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by The residence of a religious community.[44] Pope Gregory VII was critical in promoting and regulating the concept of modern university as his 1079 Papal Decree ordered the regulated establishment of cathedral schools that transformed themselves into the first European universities.[45]

The first universities in Europe with a form of corporate/guild structure were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Paris (c. 1150, later associated with the Sorbonne), and the University of Oxford (1167).

The University of Bologna began as a law school teaching the ius gentium or Roman law of peoples which was in demand across Europe for those defending the right of incipient nations against empire and church. Bologna’s special claim to Alma Mater Studiorum[clarification needed] is based on its autonomy, its awarding of degrees, and other structural arrangements, making it the oldest continuously operating institution[17] independent of kings, emperors or any kind of direct religious authority.[46][47]

The conventional date of 1088, or 1087 according to some,[48] records when Irnerius commences teaching Emperor Justinian’s 6th-century codification of Roman law, the Corpus Iuris Civilis, recently discovered at Pisa. Lay students arrived in the city from many lands entering into a contract to gain this knowledge, organising themselves into ‘Nationes’, divided between that of the Cismontanes and that of the Ultramontanes. The students «had all the power … and dominated the masters».[49][50]

All over Europe rulers and city governments began to create universities to satisfy a European thirst for knowledge, and the belief that society would benefit from the scholarly expertise generated from these institutions. Princes and leaders of city governments perceived the potential benefits of having a scholarly expertise develop with the ability to address difficult problems and achieve desired ends. The emergence of humanism was essential to this understanding of the possible utility of universities as well as the revival of interest in knowledge gained from ancient Greek texts.[51]

The recovery of Aristotle’s works – more than 3000 pages of it would eventually be translated – fuelled a spirit of inquiry into natural processes that had already begun to emerge in the 12th century. Some scholars believe that these works represented one of the most important document discoveries in Western intellectual history.[52] Richard Dales, for instance, calls the discovery of Aristotle’s works «a turning point in the history of Western thought.»[53] After Aristotle re-emerged, a community of scholars, primarily communicating in Latin, accelerated the process and practice of attempting to reconcile the thoughts of Greek antiquity, and especially ideas related to understanding the natural world, with those of the church. The efforts of this «scholasticism» were focused on applying Aristotelian logic and thoughts about natural processes to biblical passages and attempting to prove the viability of those passages through reason. This became the primary mission of lecturers, and the expectation of students.

The university culture developed differently in northern Europe than it did in the south, although the northern (primarily Germany, France and Great Britain) and southern universities (primarily Italy) did have many elements in common. Latin was the language of the university, used for all texts, lectures, disputations and examinations. Professors lectured on the books of Aristotle for logic, natural philosophy, and metaphysics; while Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna were used for medicine. Outside of these commonalities, great differences separated north and south, primarily in subject matter. Italian universities focused on law and medicine, while the northern universities focused on the arts and theology. There were distinct differences in the quality of instruction in these areas which were congruent with their focus, so scholars would travel north or south based on their interests and means. There was also a difference in the types of degrees awarded at these universities. English, French and German universities usually awarded bachelor’s degrees, with the exception of degrees in theology, for which the doctorate was more common. Italian universities awarded primarily doctorates. The distinction can be attributed to the intent of the degree holder after graduation – in the north the focus tended to be on acquiring teaching positions, while in the south students often went on to professional positions.[54] The structure of northern universities tended to be modeled after the system of faculty governance developed at the University of Paris. Southern universities tended to be patterned after the student-controlled model begun at the University of Bologna.[55] Among the southern universities, a further distinction has been noted between those of northern Italy, which followed the pattern of Bologna as a «self-regulating, independent corporation of scholars» and those of southern Italy and Iberia, which were «founded by royal and imperial charter to serve the needs of government.»[56]

Early modern universities[edit]

During the Early Modern period (approximately late 15th century to 1800), the universities of Europe would see a tremendous amount of growth, productivity and innovative research. At the end of the Middle Ages, about 400 years after the first European university was founded, there were 29 universities spread throughout Europe. In the 15th century, 28 new ones were created, with another 18 added between 1500 and 1625.[59] This pace continued until by the end of the 18th century there were approximately 143 universities in Europe, with the highest concentrations in the German Empire (34), Italian countries (26), France (25), and Spain (23) – this was close to a 500% increase over the number of universities toward the end of the Middle Ages. This number does not include the numerous universities that disappeared, or institutions that merged with other universities during this time.[60] The identification of a university was not necessarily obvious during the Early Modern period, as the term is applied to a burgeoning number of institutions. In fact, the term «university» was not always used to designate a higher education institution. In Mediterranean countries, the term studium generale was still often used, while «Academy» was common in Northern European countries.[61]

The propagation of universities was not necessarily a steady progression, as the 17th century was rife with events that adversely affected university expansion. Many wars, and especially the Thirty Years’ War, disrupted the university landscape throughout Europe at different times. War, plague, famine, regicide, and changes in religious power and structure often adversely affected the societies that provided support for universities. Internal strife within the universities themselves, such as student brawling and absentee professors, acted to destabilize these institutions as well. Universities were also reluctant to give up older curricula, and the continued reliance on the works of Aristotle defied contemporary advancements in science and the arts.[62] This era was also affected by the rise of the nation-state. As universities increasingly came under state control, or formed under the auspices of the state, the faculty governance model (begun by the University of Paris) became more and more prominent. Although the older student-controlled universities still existed, they slowly started to move toward this structural organization. Control of universities still tended to be independent, although university leadership was increasingly appointed by the state.[63]

Although the structural model provided by the University of Paris, where student members are controlled by faculty «masters», provided a standard for universities, the application of this model took at least three different forms. There were universities that had a system of faculties whose teaching addressed a very specific curriculum; this model tended to train specialists. There was a collegiate or tutorial model based on the system at University of Oxford where teaching and organization was decentralized and knowledge was more of a generalist nature. There were also universities that combined these models, using the collegiate model but having a centralized organization.[64]

Early Modern universities initially continued the curriculum and research of the Middle Ages: natural philosophy, logic, medicine, theology, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, law, grammar and rhetoric. Aristotle was prevalent throughout the curriculum, while medicine also depended on Galen and Arabic scholarship. The importance of humanism for changing this state-of-affairs cannot be underestimated.[65] Once humanist professors joined the university faculty, they began to transform the study of grammar and rhetoric through the studia humanitatis. Humanist professors focused on the ability of students to write and speak with distinction, to translate and interpret classical texts, and to live honorable lives.[66] Other scholars within the university were affected by the humanist approaches to learning and their linguistic expertise in relation to ancient texts, as well as the ideology that advocated the ultimate importance of those texts.[67] Professors of medicine such as Niccolò Leoniceno, Thomas Linacre and William Cop were often trained in and taught from a humanist perspective as well as translated important ancient medical texts. The critical mindset imparted by humanism was imperative for changes in universities and scholarship. For instance, Andreas Vesalius was educated in a humanist fashion before producing a translation of Galen, whose ideas he verified through his own dissections. In law, Andreas Alciatus infused the Corpus Juris with a humanist perspective, while Jacques Cujas humanist writings were paramount to his reputation as a jurist. Philipp Melanchthon cited the works of Erasmus as a highly influential guide for connecting theology back to original texts, which was important for the reform at Protestant universities.[68] Galileo Galilei, who taught at the Universities of Pisa and Padua, and Martin Luther, who taught at the University of Wittenberg (as did Melanchthon), also had humanist training. The task of the humanists was to slowly permeate the university; to increase the humanist presence in professorships and chairs, syllabi and textbooks so that published works would demonstrate the humanistic ideal of science and scholarship.[69]

Although the initial focus of the humanist scholars in the university was the discovery, exposition and insertion of ancient texts and languages into the university, and the ideas of those texts into society generally, their influence was ultimately quite progressive. The emergence of classical texts brought new ideas and led to a more creative university climate (as the notable list of scholars above attests to). A focus on knowledge coming from self, from the human, has a direct implication for new forms of scholarship and instruction, and was the foundation for what is commonly known as the humanities. This disposition toward knowledge manifested in not simply the translation and propagation of ancient texts, but also their adaptation and expansion. For instance, Vesalius was imperative for advocating the use of Galen, but he also invigorated this text with experimentation, disagreements and further research.[70] The propagation of these texts, especially within the universities, was greatly aided by the emergence of the printing press and the beginning of the use of the vernacular, which allowed for the printing of relatively large texts at reasonable prices.[71]

Examining the influence of humanism on scholars in medicine, mathematics, astronomy and physics may suggest that humanism and universities were a strong impetus for the scientific revolution. Although the connection between humanism and the scientific discovery may very well have begun within the confines of the university, the connection has been commonly perceived as having been severed by the changing nature of science during the Scientific Revolution. Historians such as Richard S. Westfall have argued that the overt traditionalism of universities inhibited attempts to re-conceptualize nature and knowledge and caused an indelible tension between universities and scientists.[72] This resistance to changes in science may have been a significant factor in driving many scientists away from the university and toward private benefactors, usually in princely courts, and associations with newly forming scientific societies.[73]

Other historians find incongruity in the proposition that the very place where the vast number of the scholars that influenced the scientific revolution received their education should also be the place that inhibits their research and the advancement of science. In fact, more than 80% of the European scientists between 1450 and 1650 included in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography were university trained, of which approximately 45% held university posts.[74] It was the case that the academic foundations remaining from the Middle Ages were stable, and they did provide for an environment that fostered considerable growth and development. There was considerable reluctance on the part of universities to relinquish the symmetry and comprehensiveness provided by the Aristotelian system, which was effective as a coherent system for understanding and interpreting the world. However, university professors still have some autonomy, at least in the sciences, to choose epistemological foundations and methods. For instance, Melanchthon and his disciples at University of Wittenberg were instrumental for integrating Copernican mathematical constructs into astronomical debate and instruction.[75] Another example was the short-lived but fairly rapid adoption of Cartesian epistemology and methodology in European universities, and the debates surrounding that adoption, which led to more mechanistic approaches to scientific problems as well as demonstrated an openness to change. There are many examples which belie the commonly perceived intransigence of universities.[76] Although universities may have been slow to accept new sciences and methodologies as they emerged, when they did accept new ideas it helped to convey legitimacy and respectability, and supported the scientific changes through providing a stable environment for instruction and material resources.[77]

Regardless of the way the tension between universities, individual scientists, and the scientific revolution itself is perceived, there was a discernible impact on the way that university education was constructed. Aristotelian epistemology provided a coherent framework not simply for knowledge and knowledge construction, but also for the training of scholars within the higher education setting. The creation of new scientific constructs during the scientific revolution, and the epistemological challenges that were inherent within this creation, initiated the idea of both the autonomy of science and the hierarchy of the disciplines. Instead of entering higher education to become a «general scholar» immersed in becoming proficient in the entire curriculum, there emerged a type of scholar that put science first and viewed it as a vocation in itself. The divergence between those focused on science and those still entrenched in the idea of a general scholar exacerbated the epistemological tensions that were already beginning to emerge.[78]

The epistemological tensions between scientists and universities were also heightened by the economic realities of research during this time, as individual scientists, associations and universities were vying for limited resources. There was also competition from the formation of new colleges funded by private benefactors and designed to provide free education to the public, or established by local governments to provide a knowledge-hungry populace with an alternative to traditional universities.[79] Even when universities supported new scientific endeavors, and the university provided foundational training and authority for the research and conclusions, they could not compete with the resources available through private benefactors.[80]

By the end of the early modern period, the structure and orientation of higher education had changed in ways that are eminently recognizable for the modern context. Aristotle was no longer a force providing the epistemological and methodological focus for universities and a more mechanistic orientation was emerging. The hierarchical place of theological knowledge had for the most part been displaced and the humanities had become a fixture, and a new openness was beginning to take hold in the construction and dissemination of knowledge that were to become imperative for the formation of the modern state.

Modern universities[edit]

Modern universities constitute a guild or quasi-guild system. This facet of the university system did not change due to its peripheral standing in an industrialized economy; as commerce developed between towns in Europe during the Middle Ages, though other guilds stood in the way of developing commerce and therefore were eventually abolished, the scholars guild did not. According to historian Elliot Krause, «The university and scholars’ guilds held onto their power over membership, training, and workplace because early capitalism was not interested in it.»[81]

By the 18th century, universities published their own research journals and by the 19th century, the German and the French university models had arisen. The German, or Humboldtian model, was conceived by Wilhelm von Humboldt and based on Friedrich Schleiermacher’s liberal ideas pertaining to the importance of freedom, seminars, and laboratories in universities.[citation needed] The French university model involved strict discipline and control over every aspect of the university.

Until the 19th century, religion played a significant role in university curriculum; however, the role of religion in research universities decreased during that century. By the end of the 19th century, the German university model had spread around the world. Universities concentrated on science in the 19th and 20th centuries and became increasingly accessible to the masses. In the United States, the Johns Hopkins University was the first to adopt the (German) research university model and pioneered the adoption of that model by most American universities. When Johns Hopkins was founded in 1876, «nearly the entire faculty had studied in Germany.»[82] In Britain, the move from Industrial Revolution to modernity saw the arrival of new civic universities with an emphasis on science and engineering, a movement initiated in 1960 by Sir Keith Murray (chairman of the University Grants Committee) and Sir Samuel Curran, with the formation of the University of Strathclyde.[83] The British also established universities worldwide, and higher education became available to the masses not only in Europe.

In 1963, the Robbins Report on universities in the United Kingdom concluded that such institutions should have four main «objectives essential to any properly balanced system: instruction in skills; the promotion of the general powers of the mind so as to produce not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women; to maintain research in balance with teaching, since teaching should not be separated from the advancement of learning and the search for truth; and to transmit a common culture and common standards of citizenship.»[84]

In the early 21st century, concerns were raised over the increasing managerialisation and standardisation of universities worldwide. Neo-liberal management models have in this sense been critiqued for creating «corporate universities (where) power is transferred from faculty to managers, economic justifications dominate, and the familiar ‘bottom line’ eclipses pedagogical or intellectual concerns».[85] Academics’ understanding of time, pedagogical pleasure, vocation, and collegiality have been cited as possible ways of alleviating such problems.[86]

National universities[edit]

A national university is generally a university created or run by a national state but at the same time represents a state autonomic institution which functions as a completely independent body inside of the same state. Some national universities are closely associated with national cultural, religious or political aspirations, for instance the National University of Ireland, which formed partly from the Catholic University of Ireland which was created almost immediately and specifically in answer to the non-denominational universities which had been set up in Ireland in 1850. In the years leading up to the Easter Rising, and in no small part a result of the Gaelic Romantic revivalists, the NUI collected a large amount of information on the Irish language and Irish culture.[citation needed] Reforms in Argentina were the result of the University Revolution of 1918 and its posterior reforms by incorporating values that sought for a more equal and laic[further explanation needed] higher education system.

Intergovernmental universities[edit]

Universities created by bilateral or multilateral treaties between states are intergovernmental. An example is the Academy of European Law, which offers training in European law to lawyers, judges, barristers, solicitors, in-house counsel and academics. EUCLID (Pôle Universitaire Euclide, Euclid University) is chartered as a university and umbrella organization dedicated to sustainable development in signatory countries, and the United Nations University engages in efforts to resolve the pressing global problems that are of concern to the United Nations, its peoples and member states. The European University Institute, a post-graduate university specialized in the social sciences, is officially an intergovernmental organization, set up by the member states of the European Union.

Organization[edit]

Although each institution is organized differently, nearly all universities have a board of trustees; a president, chancellor, or rector; at least one vice president, vice-chancellor, or vice-rector; and deans of various divisions. Universities are generally divided into a number of academic departments, schools or faculties. Public university systems are ruled over by government-run higher education boards[citation needed]. They review financial requests and budget proposals and then allocate funds for each university in the system. They also approve new programs of instruction and cancel or make changes in existing programs. In addition, they plan for the further coordinated growth and development of the various institutions of higher education in the state or country. However, many public universities in the world have a considerable degree of financial, research and pedagogical autonomy. Private universities are privately funded and generally have broader independence from state policies. However, they may have less independence from business corporations depending on the source of their finances.

Around the world[edit]

The funding and organization of universities varies widely between different countries around the world. In some countries universities are predominantly funded by the state, while in others funding may come from donors or from fees which students attending the university must pay. In some countries the vast majority of students attend university in their local town, while in other countries universities attract students from all over the world, and may provide university accommodation for their students.[87]

Classification[edit]

The definition of a university varies widely, even within some countries. Where there is clarification, it is usually set by a government agency. For example:

In Australia, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) is Australia’s independent national regulator of the higher education sector. Students rights within university are also protected by the Education Services for Overseas Students Act (ESOS).

In the United States there is no nationally standardized definition for the term university, although the term has traditionally been used to designate research institutions and was once reserved for doctorate-granting research institutions. Some states, such as Massachusetts, will only grant a school «university status» if it grants at least two doctoral degrees.[88]

In the United Kingdom, the Privy Council is responsible for approving the use of the word university in the name of an institution, under the terms of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992.[89]

In India, a new designation deemed universities has been created for institutions of higher education that are not universities, but work at a very high standard in a specific area of study («An Institution of Higher Education, other than universities, working at a very high standard in specific area of study, can be declared by the Central Government on the advice of the University Grants Commission as an Institution (Deemed-to-be-university). Institutions that are ‘deemed-to-be-university’ enjoy the academic status and the privileges of a university.[90] Through this provision many schools that are commercial in nature and have been established just to exploit the demand for higher education have sprung up.[91]

In Canada, college generally refers to a two-year, non-degree-granting institution, while university connotes a four-year, degree-granting institution. Universities may be sub-classified (as in the Macleans rankings) into large research universities with many PhD-granting programs and medical schools (for example, McGill University); «comprehensive» universities that have some PhDs but are not geared toward research (such as Waterloo); and smaller, primarily undergraduate universities (such as St. Francis Xavier).

In Germany, universities are institutions of higher education which have the power to confer bachelor, master and PhD degrees. They are explicitly recognised as such by law and cannot be founded without government approval. The term Universität (i.e. the German term for university) is protected by law and any use without official approval is a criminal offense. Most of them are public institutions, though a few private universities exist. Such universities are always research universities. Apart from these universities, Germany has other institutions of higher education (Hochschule, Fachhochschule). Fachhochschule means a higher education institution which is similar to the former polytechnics in the British education system, the English term used for these German institutions is usually ‘university of applied sciences’. They can confer master’s degrees but no PhDs. They are similar to the model of teaching universities with less research and the research undertaken being highly practical. Hochschule can refer to various kinds of institutions, often specialised in a certain field (e.g. music, fine arts, business). They might or might not have the power to award PhD degrees, depending on the respective government legislation. If they award PhD degrees, their rank is considered equivalent to that of universities proper (Universität), if not, their rank is equivalent to universities of applied sciences.

Colloquial usage[edit]

Colloquially, the term university may be used to describe a phase in one’s life: «When I was at university…» (in the United States and Ireland, college is often used instead: «When I was in college…»). In Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, Nigeria, the Netherlands, Spain and the German-speaking countries, university is often contracted to uni. In Ghana, New Zealand, Bangladesh and in South Africa it is sometimes called «varsity» (although this has become uncommon in New Zealand in recent years). «Varsity» was also common usage in the UK in the 19th century.[citation needed]

Cost[edit]

In many countries, students are required to pay tuition fees.

Many students look to get ‘student grants’ to cover the cost of university. In 2016, the average outstanding student loan balance per borrower in the United States was US$30,000.[92] In many U.S. states, costs are anticipated to rise for students as a result of decreased state funding given to public universities.[93] Many universities in the United States offer students the opportunity to apply for financial scholarships to help pay for tuition based on academic achievement.

There are several major exceptions on tuition fees. In many European countries, it is possible to study without tuition fees. Public universities in Nordic countries were entirely without tuition fees until around 2005. Denmark, Sweden and Finland then moved to put in place tuition fees for foreign students. Citizens of EU and EEA member states and citizens from Switzerland remain exempted from tuition fees, and the amounts of public grants granted to promising foreign students were increased to offset some of the impact.[94] The situation in Germany is similar; public universities usually do not charge tuition fees apart from a small administrative fee. For degrees of a postgraduate professional level sometimes tuition fees are levied. Private universities, however, almost always charge tuition fees.

See also[edit]

- Alternative university

- Alumni

- Ancient higher-learning institutions

- Catholic university

- College and university rankings

- Corporate university

- International university

- Land-grant university

- Liberal arts college

- List of academic disciplines

- Lists of universities and colleges

- Pontifical university

- Research university

- School and university in literature

- Science tourism

- UnCollege

- University student retention

- University system

- Urban university

References[edit]

- ^ «Universities» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ Den Heijer, Alexandra (2011). Managing the University Campus: Information to Support Real Estate Decisions. Academische Uitgeverij Eburon. ISBN 9789059724877.

Many of the medieval universities in Western Europe were born under the aegis of the Catholic Church, usually as cathedral schools or by papal bull as Studia Generali.

- ^ A. Lamport, Mark (2015). Encyclopedia of Christian Education. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 484. ISBN 9780810884939.

All the great European universities-Oxford, to Paris, to Cologne, to Prague, to Bologna—were established with close ties to the Church.

- ^ B M. Leonard, Thomas (2013). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Routledge. p. 1369. ISBN 9781135205157.

Europe established schools in association with their cathedrals to educate priests, and from these emerged eventually the first universities of Europe, which began forming in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

- ^ Gavroglu, Kostas (2015). Sciences in the Universities of Europe, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Academic Landscapes. Springer. p. 302. ISBN 9789401796361.

- ^ GA. Dawson, Patricia (2015). First Peoples of the Americas and the European Age of Exploration. Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 9781502606853.

- ^ «The University from the 12th to the 20th century — University of Bologna». www.unibo.it. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Top Universities Archived 17 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine World University Rankings Retrieved 6 January 2010

- ^ Paul L. Gaston (2010). The Challenge of Bologna. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-57922-366-3. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Hunt Janin: «The university in medieval life, 1179–1499», McFarland, 2008, ISBN 0-7864-3462-7, p. 55f.

- ^ de Ridder-Symoens, Hilde: A History of the University in Europe: Volume 1, Universities in the Middle Ages Archived 13 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. 47–55

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1966) [1879], A Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- ^ Marcia L. Colish, Medieval Foundations of the Western Intellectual Tradition, 400-1400, (New Haven: Yale Univ. Pr., 1997), p. 267.

- ^ «university, n.», OED Online (3rd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, archived from the original on 30 April 2021, retrieved 27 August 2013

- ^ «university, n.», OED Online (3rd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, archived from the original on 30 April 2021, retrieved 27 August 2013,

…In the Middle Ages: a body of teachers and students engaged in giving and receiving instruction in the higher branches of study … and regarded as a scholastic guild or corporation.

Compare «University», Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989,The whole body of teachers and scholars engaged, at a particular place, in giving and receiving instruction in the higher branches of learning; such persons associated together as a society or corporate body, with definite organization and acknowledged powers and privileges (esp. that of conferring degrees), and forming an institution for the promotion of education in the higher or more important branches of learning….

- ^ Malagola, C. (1888), Statuti delle Università e dei Collegi dello Studio Bolognese. Bologna: Zanichelli.

- ^ a b Rüegg, W. (2003). «Chapter 1: Themes». In De Ridder-Symoens, H. (ed.). A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4–34. ISBN 0-521-54113-1.

- ^ Watson, P. (2005), Ideas. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, page 373

- ^ «Magna Charta delle Università Europee». .unibo.it. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Belhachmi, Zakia: «Gender, Education, and Feminist Knowledge in al-Maghrib (North Africa) – 1950–70», Journal of Middle Eastern and North African Intellectual and Cultural Studies, Vol. 2–3, 2003, pp. 55–82 (65):

The Adjustments of Original Institutions of the Higher Learning: the Madrasah. Significantly, the institutional adjustments of the madrasahs affected both the structure and the content of these institutions. In terms of structure, the adjustments were twofold: the reorganization of the available original madaris and the creation of new institutions. This resulted in two different types of Islamic teaching institutions in al-Maghrib. The first type was derived from the fusion of old madaris with new universities. For example, Morocco transformed Al-Qarawiyin (859 A.D.) into a university under the supervision of the ministry of education in 1963.

- ^ Frew, Donald (1999). «Harran: Last Refuge of Classical Paganism». The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 13 (9): 17–29. doi:10.1558/pome.v13i9.17.

- ^ Verger, Jacques: «Patterns», in: Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de (ed.): A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54113-8, pp. 35–76 (35)

- ^ Esposito, John (2003). The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-1951-2559-7.

- ^ Joseph, S, and Najmabadi, A. Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures: Economics, education, mobility, and space. Brill, 2003, p. 314.

- ^ Swartley, Keith. Encountering the World of Islam. Authentic, 2005, p. 74.

- ^ A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 2003, 35

- ^ Petersen, Andrew: Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, 1996, ISBN 978-0-415-06084-4, p. 87 (entry «Fez»):

The Quaraouiyine Mosque, founded in 859, is the most famous mosque of Morocco and attracted continuous investment by Muslim rulers.

- ^ Lulat, Y. G.-M.: A History Of African Higher Education From Antiquity To The Present: A Critical Synthesis Studies in Higher Education, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 978-0-313-32061-3, p. 70:

As for the nature of its curriculum, it was typical of other major madrasahs such as al-Azhar and Al Quaraouiyine, though many of the texts used at the institution came from Muslim Spain…Al Quaraouiyine began its life as a small mosque constructed in 859 C.E. by means of an endowment bequeathed by a wealthy woman of much piety, Fatima bint Muhammed al-Fahri.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin: Encyclopedia of African History, Vol. 2, Fitzroy Dearborn, 2005, ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6, p. 1025:

Higher education has always been an integral part of Morocco, going back to the ninth century when the Karaouine Mosque was established. The madrasa, known today as Al Qayrawaniyan University, became part of the state university system in 1947.

They consider institutions like al-Qarawiyyin to be higher education colleges of Islamic law where other subjects were only of secondary importance.

- ^ Pedersen, J.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R.: «Madrasa», in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd edition, Brill, 2010:

Madrasa, in modern usage, the name of an institution of learning where the Islamic sciences are taught, i.e. a college for higher studies, as opposed to an elementary school of traditional type (kuttab); in medieval usage, essentially a college of law in which the other Islamic sciences, including literary and philosophical ones, were ancillary subjects only.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (ed.): Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, A–K, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7, p. 457 (entry «madrasa»):

A madrasa is a college of Islamic law. The madrasa was an educational institution in which Islamic law (fiqh) was taught according to one or more Sunni rites: Maliki, Shafi’i, Hanafi, or Hanbali. It was supported by an endowment or charitable trust (waqf) that provided for at least one chair for one professor of law, income for other faculty or staff, scholarships for students, and funds for the maintenance of the building. Madrasas contained lodgings for the professor and some of his students. Subjects other than law were frequently taught in madrasas, and even Sufi seances were held in them, but there could be no madrasa without law as technically the major subject.

- ^ Makdisi, George: «Madrasa and University in the Middle Ages», Studia Islamica, No. 32 (1970), pp. 255–264 (255f.):

In studying an institution which is foreign and remote in point of time, as is the case of the medieval madrasa, one runs the double risk of attributing to it characteristics borrowed from one’s own institutions and one’s own times. Thus gratuitous transfers may be made from one culture to the other, and the time factor may be ignored or dismissed as being without significance. One cannot therefore be too careful in attempting a comparative study of these two institutions: the madrasa and the university. But in spite of the pitfalls inherent in such a study, albeit sketchy, the results which may be obtained are well worth the risks involved. In any case, one cannot avoid making comparisons when certain unwarranted statements have already been made and seem to be currently accepted without question. The most unwarranted of these statements is the one which makes of the «madrasa» a «university».

- ^ a b Lulat, Y. G.-M.: A History Of African Higher Education From Antiquity To The Present: A Critical Synthesis, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 978-0-313-32061-3, pp. 154–157

- ^ Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar: Historical Dictionary of Morocco, 2nd ed., Scarecrow Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8108-5341-6, p. 348

al-qarawiyin is the oldest university in Morocco. It was founded as a mosque in Fès in the middle of the ninth century. It has been a destination for students and scholars of Islamic sciences and Arabic studies throughout the history of Morocco. There were also other religious schools like the madras of ibn yusuf and other schools in the sus. This system of basic education called al-ta’lim al-aSil was funded by the sultans of Morocco and many famous traditional families. After independence, al-qarawiyin maintained its reputation, but it seemed important to transform it into a university that would prepare graduates for a modern country while maintaining an emphasis on Islamic studies. Hence, al-qarawiyin university was founded in February 1963 and, while the dean’s residence was kept in Fès, the new university initially had four colleges located in major regions of the country known for their religious influences and madrasas. These colleges were kuliyat al-shari’s in Fès, kuliyat uSul al-din in Tétouan, kuliyat al-lugha al-‘arabiya in Marrakech (all founded in 1963), and kuliyat al-shari’a in Ait Melloul near Agadir, which was founded in 1979.

- ^ Nuria Sanz, Sjur Bergan (1 January 2006). The heritage of European universities, Volume 548. Council of Europe. p. 28. ISBN 9789287161215. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015.

- ^ Makdisi, George (April–June 1989). «Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West». Journal of the American Oriental Society. 109 (2): 175–182 [175–77]. doi:10.2307/604423. JSTOR 604423.; Makdisi, John A. (June 1999). «The Islamic Origins of the Common Law». North Carolina Law Review. 77 (5): 1635–1739.

- ^ Goddard, Hugh (2000). A History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Edinburgh University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7486-1009-9.

- ^ Daniel, Norman (1984). «Review of «The Rise of Colleges. Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West by George Makdisi»«. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 104 (3): 586–8. doi:10.2307/601679. JSTOR 601679.

Professor Makdisi argues that there is a missing link in the development of Western scholasticism, and that Arab influences explain the «dramatically abrupt» appearance of the «sic et non» method. Many medievalists will think the case overstated, and doubt that there is much to explain.

- ^ Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2013), «The origins of higher learning: time for a new historiography?», in Feingold, Mordecai (ed.), History of Universities, vol. 27, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–19, ISBN 9780199685844, archived from the original on 5 September 2015

- ^ Rüegg, Walter: «Foreword. The University as a European Institution», in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX

- ^ Verger, Jacques. “The Universities and Scholasticism,” in The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume V c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 257.

- ^ Riché, Pierre (1978): «Education and Culture in the Barbarian West: From the Sixth through the Eighth Century», Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 0-87249-376-8, pp. 126-7, 282-98

- ^ Gordon Leff, Paris and Oxford Universities in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. An Institutional and Intellectual History, Wiley, 1968.

- ^ Johnson, P. (2000). The Renaissance : a short history. Modern Library chronicles (Modern Library ed.). New York: Modern Library, p. 9.

- ^ Thomas Oestreich (1913). «Pope St. Gregory VII». In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Makdisi, G. (1981), Rise of Colleges: Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Daun, H. and Arjmand, R. (2005), Islamic Education, pp 377-388 in J. Zajda, editor, International Handbook of Globalisation, Education and Policy Research. Netherlands: Springer.

- ^ Huff, T. (2003), The Rise of Early Modern Science. Cambridge University Press, p. 122

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Uses of the University. Harvard University Press. pp. 16 and 145. ISBN 978-0674005327.

- ^ Rüegg, W. (2003), Mythologies and Historiography of the Beginnings, pp 4-34 in H. De Ridder-Symoens, editor, A History of the University in Europe; Vol 1, Cambridge University Press.p. 12

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). «The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation». Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 2.

- ^ Rubenstein, R. E. (2003). Aristotle’s children: how Christians, Muslims, and Jews rediscovered ancient wisdom and illuminated the dark ages (1st ed.). Orlando, Florida: Harcourt, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Dales, R. C. (1990). Medieval discussions of the eternity of the world (Vol. 18). Brill Archive, p. 144.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). «The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation». Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 2-8.

- ^ Scott, J. C. (2006). «The mission of the university: Medieval to Postmodern transformations». Journal of Higher Education. 77 (1): 6. doi:10.1353/jhe.2006.0007. S2CID 144337137.

- ^ Pryds, Darleen (2000), «Studia as Royal Offices: Mediterranean Universities of Medieval Europe», in Courtenay, William J.; Miethke, Jürgen; Priest, David B. (eds.), Universities and Schooling in Medieval Society, Education and Society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, vol. 10, Leiden: Brill, pp. 84–85, ISBN 9004113517

- ^ «University League Tables 2021». www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ «The best UK universities 2021 – rankings». the Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation. Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 1-3.

- ^ Frijhoff, W. (1996). Patterns. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in early modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, p. 75.

- ^ Frijhoff, W. (1996). Patterns. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in early modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, p. 47.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation. Renaissance Quarterly, 57, p. 23.

- ^ Scott, J. C. (2006). «The mission of the university: Medieval to Postmodern transformations». Journal of Higher Education. 77 (1): 10–13. doi:10.1353/jhe.2006.0007. S2CID 144337137.

- ^ Frijhoff, W. (1996). Patterns. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in early modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, p. 65.

- ^ Ruegg, W. (1992). Epilogue: the rise of humanism. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in the Middle Ages, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2002). The universities of the Italian renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 223.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2002). The universities of the Italian renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 197.

- ^ Ruegg, W. (1996). Themes. In H. D. Ridder-Symoens (Ed.), Universities in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1800, A history of the university in Europe. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, pp. 33-39.

- ^ Grendler, P. F. (2004). The universities of the Renaissance and Reformation. Renaissance Quarterly, 57, pp. 12-13.

- ^ Bylebyl, J. J. (2009). Disputation and description in the renaissance pulse controversy. In A. Wear, R. K. French, & I. M. Lonie (Eds.), The medical renaissance of the sixteenth century (1st ed., pp. 223-245). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Füssel, S. (2005). Gutenberg and the Impact of Printing (English ed.). Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Pub., p. 145.

- ^ Westfall, R. S. (1977). The construction of modern science: mechanisms and mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 105.

- ^ Ornstein, M. (1928). The role of scientific societies in the seventeenth century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Gascoigne, J. (1990). A reappraisal of the role of the universities in the Scientific Revolution. In D. C. Lindberg & R. S. Westman (Eds.), Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution, pp. 208-209.

- ^ Westman, R. S. (1975). «The Melanchthon circle:, rheticus, and the Wittenberg interpretation of the Copernicantheory». Isis. 66 (2): 164–193. doi:10.1086/351431. S2CID 144116078.

- ^ Gascoigne, J. (1990). A reappraisal of the role of the universities in the Scientific Revolution. In D. C. Lindberg & R. S. Westman (Eds.), Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution, pp. 210-229.

- ^ Gascoigne, J. (1990). A reappraisal of the role of the universities in the Scientific Revolution. In D. C. Lindberg & R. S. Westman (Eds.), Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution, pp. 245-248.

- ^ Feingold, M. (1991). Tradition vs novelty: universities and scientific societies in the early modern period. In P. Barker & R. Ariew (Eds.), Revolution and continuity: essays in the history and philosophy of early modern science, Studies in philosophy and the history of philosophy. Washington, D.C: Catholic University of America Press, pp. 53-54.

- ^ Feingold, M. (1991). Tradition vs novelty: universities and scientific societies in the early modern period. In P. Barker & R. Ariew (Eds.), Revolution and continuity: essays in the history and philosophy of early modern science, Studies in philosophy and the history of philosophy. Washington, D.C: Catholic University of America Press, pp. 46-50.

- ^ See; Baldwin, M (1995). «The snakestone experiments: an early modern medical debate». Isis. 86 (3): 394–418. doi:10.1086/357237. PMID 7591659. S2CID 6122500.

- ^ Krause, Elliot (1996). Death of Guilds:Professions, States, and The Advance of Capitalism, 1930 to The Present}. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

- ^ Menand, Louis; Reitter, Paul; Wellmon, Chad (2017). «General Introduction». The Rise of the Research University: A Sourcebook. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780226414850. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ «Oxford Dictionary of National Biography». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/69524. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Anderson, Robert (March 2010). «The ‘Idea of a University’ today». History & Policy. United Kingdom: History & Policy. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Maggie Berg & Barbara Seeber. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy, p. x. Toronto: Toronto University Press. 2016.

- ^ Maggie Berg & Barbara Seeber. The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy. Toronto: Toronto University Press. 2016. (passim)

- ^ «Basic Classification Technical Details». Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- ^ «Massachusetts Board of Education: Degree-granting regulations for independent institutions of higher education» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ «Higher Education». Privy Council Office. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ «Deemed University». mhrd.gov.in. MHRD. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015.

- ^ — Peter Drucker. «‘Deemed’ status distributed freely during Arjun Singh’s tenure — LearnHub News». Learnhub.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ «Students are graduating with $30,000 in loans». 18 October 2016. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ «Students at Public Universities, Colleges Will Bear the Burden of Reduced Funding for Higher Education». Time. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ «Studieavgifter i högskolan» Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine SOU 2006:7 (in Swedish)

Further reading[edit]

- Aronowitz, Stanley (2000). The Knowledge Factory: Dismantling the Corporate University and Creating True Higher Learning. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-3122-3.

- Barrow, Clyde W. (1990). Universities and the Capitalist State: Corporate Liberalism and the Reconstruction of American Higher Education, 1894–1928. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-12400-7.

- Diamond, Sigmund (1992). Compromised Campus: The Collaboration of Universities with the Intelligence Community, 1945–1955. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505382-1.

- Pedersen, Olaf (1997). The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59431-8.

- Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de, ed. (1992). A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages. Rüegg, Walter (general ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36105-7.

- Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de, ed. (1996). A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 2: Universities in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800). Rüegg, Walter (general ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36106-4.

- Rüegg, Walter, ed. (2004). A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 3: Universities in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (1800–1945). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36107-1.

- Segre, Michael (2015). Higher Education and the Growth of Knowledge: A Historical Outline of Aims and Tensions. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-73566-7.

External links[edit]