How to teach vocabulary to EFL students

Teaching vocabulary is a vital part of any English language course. Many teachers are concerned about how to teach vocabulary. New words have to be introduced in such a way as to capture the students’ attention and place the words in their memories.

Students need to be aware of techniques for memorising large amounts of new vocabulary in order to progress in their language learning.

English vocabulary learning can often be seen as a laborious process of memorising lists of unrelated terms. However, there are many other much more successful and interesting ways to learn and teach vocabulary in the EFL classroom.

[wp_ad_camp_1]

Making new words memorable

If English vocabulary is taught in an uninteresting way such as by drilling, simple repetition and learning lists, then the words are likely to be forgotten.

Teachers need to teach vocabulary so that the words are learned in a memorable way, in order for them to stick in the long-term memory of the student.

Please see the Practice, presentation and production teaching method and the lesson plan suggestions for lesson and activity ideas. Our task-based learning page also contains useful tips on contextualising vocabulary and making it feel relevant and natural.

[wp_ad_camp_2]

Teaching active and passive vocabulary

When thinking about how to teach vocabulary, it is important to remember that learners need to have both active and passive vocabulary knowledge.

That is, students must vocabulary should consist of English words the learners will be expected to use themselves in original sentences, and those they will merely have to recognise when they hear them or see them written down by others.

Teaching passive vocabulary is important for comprehension – the issue of understanding another speaker needs the listener to have passive vocabulary, that is, enough knowledge of words used by others to comprehend their meaning. This is also called receptive knowledge of English.

Teaching active vocabulary is important for an advanced student in terms of their own creativity. This is because in order to create their own sentences, students need active vocabulary.

Active vocabulary contains the words a student can understand and manipulate in order to use for their own personal expression. This is called productive knowledge of English.

Methods for Teaching Vocabulary

Word cards and word association

Teachers can use devices for vocabulary teaching such as simple flash-cards or word-cards. The teacher writes the English language word on one side of the card and a sentence containing the word, its definition, its synonyms and pronunciation on the other. Word cards can be an excellent memory aid.

This is also a handy way for students to carry their new vocabulary around with them to look at whenever they have the opportunity.

Another successful method of teaching vocabulary is the word association technique. If words are stored individually, they are more difficult to remember as they have no context.

But if the words are stored together in commonly used phrases and sentences, they are more readily absorbed. Putting words with collocational partners in this way helps the students to relate connected words together.

[wp_ad_camp_3]

Visual techniques

Teaching vocabulary can become easier with the use of cards with pictures, diagrams and liberal colour coding for grammatical clarity.

In this way, words are remembered by their colour or position on a page or their association with other words, pictures or phrases.

Images can link to words; words can also be linked to other words, for example, a student might link the word ‘car’ with ‘garage’ and with ‘mechanic’.

This idea of engaging the other senses can also help with developing a kind of semantic map where words are listed which relate to each other, which creates a situation where one word reminds the student of another.

[wp_ad_camp_2]

Brainstorming

When teaching new vocabulary, the method of delivery needs to be fresh and interesting for the students or else they will not remember the words.

Ways in which to liven up the introduction of new English vocabulary could include brainstorming around an existing word in the students’ vocabulary knowledge.

This key word should be written up in the middle of the board and the new vocabulary relating to it can be written around it. Use colourful pens if writing on a whiteboard to emphasise different word types.

Matching columns

Once the new vocabulary has been taught, a useful way to test if students have understood the meanings of this new vocabulary is to ask them to match new words from one column with definitions from another column.

Testing comprehension is vital before moving onto new vocabulary. The new words are numbered in column one, and the definitions are mixed up and lettered in column two.

Students can also make up sentences using this technique, matching the beginning of the sentence or phrase from column 1 with the end of the sentence or phrase from column 2.

What is it to know a word?

Teachers need to ask what is it to know a word? There is more to teaching a word than simply translating it or even using it in a sentence as an example.

Knowing a word means knowing not only the meaning, but knowing the contexts in which that word is used, the words which are related to it and where to use the word. It also requires knowing hidden implications that could be connected with the word.

Idioms

Alongside chunks of language and fixed phrases and expressions, teachers should include in their vocabulary lessons these kinds of idioms of the English language.

Idioms are common features of every day language and are an important part of advanced language use and a major step towards fluency.

Idioms can be introduced to the ESL classroom through authentic reading materials such as informal text from magazines, low-brow newspapers, letters, comic strips, pop songs, dialogue from radio or television, popular films and soaps.

[wp_ad_camp_2]

Collocations

Grammatical collocations are when a noun, verb or adjective occur (usually) alongside a preposition. For example: ‘on purpose’, ‘by accident’, ‘in case’.

Lexical collocations are made up of combinations of lexical items such as nouns, adjectives, adverbs and verbs. Examples of lexical collocations are: dripping tap, hopelessly addicted, cook dinner, happy birthday, great expectations.

Lexical phrases are good for teachers to include in lessons as another way of improving the natural sound of the students in speaking the language.

Phrases such as ‘thanks very much’, ‘don’t mention it’, ‘have a nice day’, ‘sorry about that’, are all useful in conversation.

More idiomatic phrases such as ‘practise makes perfect’, ‘it’s a high mountain to climb’ or ‘it glides like a knife through butter’ are good for fluency and help with understanding commonly used similes.

In addition there are lots of idiomatic and phrasal verb collocations such as:

- putting something or someone off

- coming down with a cold

- giving up on something

- giving in to something

- feeling under the weather

- striking up a conversation

- bumping into someone

- getting out of something

- butting in on a conversation

- giving in to something or someone

- In telephone calls, we talk about ‘being put through’ and ‘cutting someone off’

- Sometimes single words in English have different meanings, for example, the words ‘drive’, ‘pool’, ‘stroke’, ‘bottom’, ‘fence’, ‘catch’, ‘strike’, ‘match’.

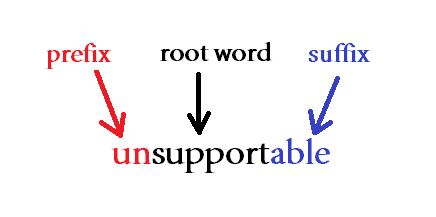

Prefixes and suffixes

Prefixes can make a word negative, for example, adding ‘un-’, ‘a-‘ or ‘dis-’. These inflections are vital for students’ understanding of words and can increase their vocabulary substantially simply by inflecting words they already know.

Suffixes work in this same vocabulary enhancing way, by adding endings such as ‘ing’, ‘less’ and ‘ly’.

Teaching the prefixes and suffixes appropriate to new vocabulary can help students to guess what a new word might mean by reference to words they already know. In this way, prefixes and suffixes can help to introduce new words easily.

For example, knowledge of the word ‘friend’ can help a student to guess the meanings of the words ‘friendly’, ‘friendship’, ‘unfriendly’ or ‘friendless’.

Teaching students the common prefixes and suffixes of the English language can help students to increase their vocabulary greatly by recognising these other derived words.

Connotations and Appropriateness

Teaching vocabulary involves teaching the connotations of a word and its appropriate usage. The connotations of a word are the feelings it strikes up such as positive or negative feelings, and more specific ones for certain words.

Related to this area of connotation is appropriateness, such as whether or not a certain English phrase is acceptable in polite conversation with a stranger, or if it would be a faux pas or even taboo. It can help students understand if a word is rare or old fashioned, if it is a funny word, or more commonly used in written text, formal or informal or only used in a certain dialect.

These issues are important in vocabulary teaching in order for the student to feel confident using the new vocabulary in new or challenging situations.

Polysemy and homonemy

When teaching vocabulary, there are subtle differences between similar English words that needs to be communicated to the students in order to avoid causing confusion.

Teaching polysemy enables the student to distinguish between the different meanings of a word with closely related meanings; teaching homonymy distinguishes between the different meanings of a word with distinct meanings.

Read more about homonyms in our English phonology section. Remember also to consider rhythm and intonation in English, both of which can make a huge difference to meaning or nuance and can be difficult for students to master.

Check out the the language guide, in particular the orthography, phonology and vocabulary sections, for more discussion on these kinds of confusing words.

Register

Register is the relationship between the content of a message, the receiver, and how the message is communicated. Knowledge of these things helps students to distinguish between levels of formality and the effects of certain topics on the listener.

Explore more about register, form and genre in the English orthography section.

Practice, presentation and production

The Practice, Presentation and Production teaching method is a popular and effective way in which to teach new vocabulary. Browse the site for more information on all areas of English language teaching, including this popular PPP technique.

Do you have any more tips on how to teach vocabulary to EFL students?

Share your ideas in the comments.

[wp_ad_camp_4]

1. Word Wall

To help your students get more engaged in vocabulary development, you need to nurture word consciousness. This means raising students’ awareness of, and interest in all sorts of words and their meanings.

A Word Wall can help you achieve this. This is a collection of words that are displayed in large visible letters on a wall, bulletin board, or other display surfaces in a classroom.

Source: ELL STRATEGIES & MISCONCEPTIONS

So, set this wall and encourage your students ‘to walk the wall’ and hang their favourite words, new or unknown, on it.

Then, invite their classmates to add sticky notes with pictures or graphics, synonyms, antonyms, or related words. Then, student partners walk along the wall to quiz each other on the words (Graves & Watts-Taffe,2008).

Use the Word Wall one or more times a week. You’ll help your students make connections between new and known words.

Since this is an ongoing activity during the whole year, you can keep observational notes of those students who are posting, responding to their words and those who are not adding words to the wall.

This will help you better understand what your students need to expand their vocabulary.

2. Word Box

Word Box is one of the strategies for teaching vocabulary. This is a weekly strategy that can help students retain and use words more effectively.

Students select words to submit to the word box on Friday. These are words they find interesting or ones they want to understand better. They either use the word in their own sentence or take the same sentence where this word was found.

Then, select five words to teach the following week.

Monday: Introduce the five words in context, explain them, then tack them to the Word Wall.

Tuesday: Ask students to create a non-linguistic representation of the words.

Wednesday: Discuss the meaning of the words allowing think-pair-shares.

Thursday: Ask students to write sentences using those words.

Friday: This is the day to assess students’ learning of the five words using this activity.

Ask one student to answer fill-ins for five words. Give students three cards that can hold up: green cards show they agree with the student’s answer, yellow they are unsure and red ones they disagree.

For assessing, use a checklist with the vocabulary running horizontally across the top margin and the class list running vertically down the side. (Adapted from Grant et al., 2015, p.195)

3. Vocabulary Notebooks

Ask your students to maintain vocabulary notebooks throughout the year where they write the meaning of the new words.

You can introduce a new word each week and work together with students to explore its meaning. Then, ask them to sketch a picture to illustrate the word and present their drawings to the class at the end of the week.

Another way to use vocabulary notebooks :

Students create a chart. The first column indicates the word, where it was found, and the sample sentence in which it appeared.

The other columns depend on your students’ needs.

You can include a column for meaning ( where students define the word or add a synonym), for word parts and related word forms (where they identify the parts and list any other words related to it), a picture, other occurrences (if they have seen or heard this word before, they describe where) and for practice or how they used this word. (Lubliner, 2005)

4. Semantic Mapping

These are maps or webs of words that can help visually display the meaning-based connections between a word or phrase and a set of related words or concepts.

Teach your students how to use semantic mapping. Pick a word you intend to explain, draw a map or web on the board ( or on Zoom whiteboard or any digital tool in case you’re teaching online) and put this word in the centre of the map. Then, ask students to add related words or phrases similar in meaning to the new word. (see the example below)

Source:weebly.com

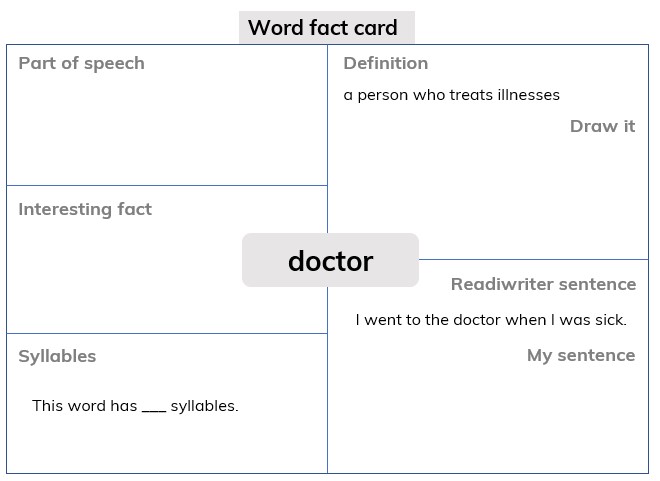

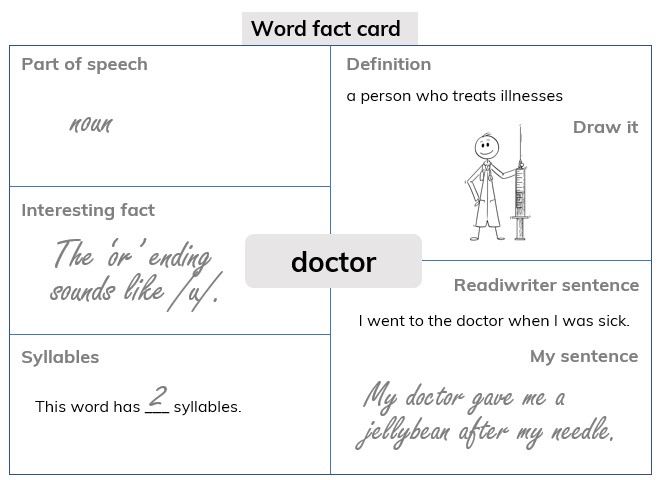

5. Word Cards

Word cards can help students review frequently learned words and so improve retention.

On one side of the card, students write the target word and its part of speech (whether it’s a verb, noun, adjective, etc.).

On the top half of the other side, they write the word’s definition (in English and/ or a translation). They also write an example and a description of its pronunciation. The bottom half of the card can be used for additional notes once they start using the word.

Ask students to add more information about the word each time they practise or observe it (sentences, collocations, etc.).

Yet, advise them not to add too much information in order to facilitate more reviewing the cards.

Devote regularly class time for students to bring their word cards to class. Involve them in activities such as describing the new words, quizzing one another, categorizing them according to subject or part of speech.

Also, show your students how to store and organize those cards. This is, for instance, by putting them into a box with the categories they select or ordering them in terms of difficulty. (Schmitt & Schmitt, 2005)

6. Word Learning Strategies

Our students often have only partial knowledge of the words they learn in the classroom. This is so since a word can have different meanings which they may not be familiar with.

Therefore, teaching students word learning strategies is important to help them become independent word learners. This is by teaching, modelling and providing a variety of strategies that serve different purposes.

Here are some examples of word-learning strategies.

a) Using word parts

Breaking words into meaningful parts facilitates decoding. So, studying words’ parts can help students guess the meaning of new words from context.

There are three basic ways that word parts are combined in English: prefixing, suffixing, and compounding.

Teach those parts. But, focus on the most occurrent ones.

Providing explanations about their use and meanings with illustration is necessary. Yet, it is still not enough.

You need to provide opportunities for students to experiment with word-building skills.

For instance, you can hand out a list of productive prefixes and have students compile a list of words using them. Then, ask them to compare the function of the prefixes in the various examples.

However, consider your students’ level since word parts are more useful to students with larger vocabularies. For instance, a student who doesn’t know the meaning of the adjective content cannot guess the word discontent.

Remember also that learning word parts is an ongoing process. So, encourage your students to continue experimenting with them. (Zimmerman, 2009a)

b) Asking questions about word

Knowing a word means knowing about its many aspects: its meaning(s), collocations, grammatical function, derivations, and register.

So, you can encourage your students to explore a new word’s meaning(s) by asking them to address detailed questions about those features and answer them.

Students will ask questions like these :

• Are there certain words that often occur before or after the word ? (collocation)

• Are there any grammatical patterns that occur with the word ? (grammar).

• Are there any familiar roots or affixes for this word ? (word parts)

• Is the word used by both men and women? (register/appropriateness)

• Is the word used in both speaking and writing?

(register/appropriateness)

• Could it be used to refer to people? Animals?Things? (meaning)

• Does it have any positive or negative connotations? (meaning) (Zimmerman,2009a)

c) Reflecting

When students learn new words it does not necessarily mean they’ll use them. Students may avoid using words in writing because they are unsure of the spelling. When they speak, they may not be willing to use certain words as they roughly understand them in context.

Encouraging students to self-assess their knowledge of each new word they learn can help them focus on areas needing practices. Here is an example of a self-assessment scale students can use.

Besides these 6 engaging strategies for teaching vocabulary, here are some essential tips to follow while using them :

1) Identify the potential list of words to be taught. Keep the number of words to a minimum (three to five words in one lesson) to ensure there is ample time for in-depth vocabulary instruction, yet enough time for students to practise them.

2) Expose students to multiple contexts in which the new words can be used. This will support them to develop a deeper understanding of these words and how they’re used flexibly.

You can do so by giving students frequent opportunities to hear the meaning of the words, read content where these words are included, and also use them in speaking and writing.

3) Encourage extensive reading because this gives students repeated or multiple exposures to words and is also one of the means by which students see vocabulary in rich contexts.

So, for rich vocabulary development, use a variety of strategies for teaching vocabulary and provide the necessary support and guided practice. Besides, assess vocabulary learning and encourage students to learn more words outside the classroom.

What other Strategies For Teaching Vocabulary would you suggest? I would love to hear from you.

References

Grant, K..B., Golden, S.E., & Wilson, N.S.(2015). Literacy Assessment and Instructional Strategies: Connecting to the Common Core. USA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2002). The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program. In A.E. Farstrup 1 S.J.Samuels (Eds.), what research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp.140-165). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2008). For the love of words: Fostering word consciousness in young readers. The Reading Teacher, 62 (3), 185-193.

Hulstijn, J. & Laufer, B.(2001). Some empirical evidence for the involvement load hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition. Language Learning 51/3:539-58.

Lubliner, SH.(2005). Getting into Words: Vocabulary Instruction That Strengthens Comprehension. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing.

Schmitt, D., & Schmitt, N.(2005). Focus on Vocabulary. New York: Longman.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009a). Word Knowledge: A vocabulary teacher’s handbook. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009b).(ed.). Inside Reading: The Academic Word List in Context. Four Levels. New York: Oxford University Press.

“Vocabulary size is a convenient proxy for a whole range of educational attainments and abilities – not just skill in reading, writing, listening, and speaking, but also general knowledge of science, history, and the arts.”

A wealth of words, by E. D. Hirsch Jr

Vocabulary is something we continue to learn and develop throughout our entire lives – an unconstrained skill. While some vocabulary is acquired implicitly through everyday interactions, it’s important to teach more complex and technical vocabulary explicitly. We can’t rely on fate, osmosis and exposure for students to learn the 50,000+ words they need to thrive in school and beyond.

Further, vocabulary is becoming more important in a world of digital dependency. Autocorrect may have a chance of picking up incorrect spelling, but it can’t be relied on to help you choose the word with the right meaning.

Teaching vocabulary is about context and repetition– what they need to know about the words they’re using, and using them multiple times.

But before we get onto that, here are some key things we have to understand to teach vocabulary:

The three tiers of vocabulary

For the past two decades, it has been acknowledged that there are three broad tiers of vocabulary. An awareness of these tiers is critical to assist teachers in selecting the right words to teach explicitly in their classrooms – from the first day of school to the last.

Tier 1

These are basic words of everyday language – high frequency words. With around 8000 word families in Tier 1, including words like ‘dog’, ‘good’, ‘phone’ and ‘happy’, these words do not generally require explicit teaching for the majority of students. However, explicit teaching is required to make the most of this level of vocabulary particularly for homophones and words with more than one meaning.

Tier 2

Tier 2 words are the words needed to understand and express complex ideas in an academic context. Tier 2 includes words like ‘formulate’, ‘specificity’, ‘calibrate’ and ‘hypothesis’. These words are useful across multiple topics and subject areas and effective use can reflect a mature understanding of academic language.

Tier 3

Tier 3 words aren’t used often and are normally reserved for specific topics or subjects – words like ‘orthography’, ‘morphology’ and ‘etymology’ in the field of linguistics, or ‘isosceles’, ‘circumference’ and ‘quantum’ for the world of mathematics and physics. Some of these words may also exist as a Tier 1 or 2 word but have a particular use and purpose as a Tier 2 word, such as ‘substitute’, ‘similarity’ and ‘expression’ in a mathematical context. These words must be taught explicitly in the context of their meaning and purpose in a particular unit of study.

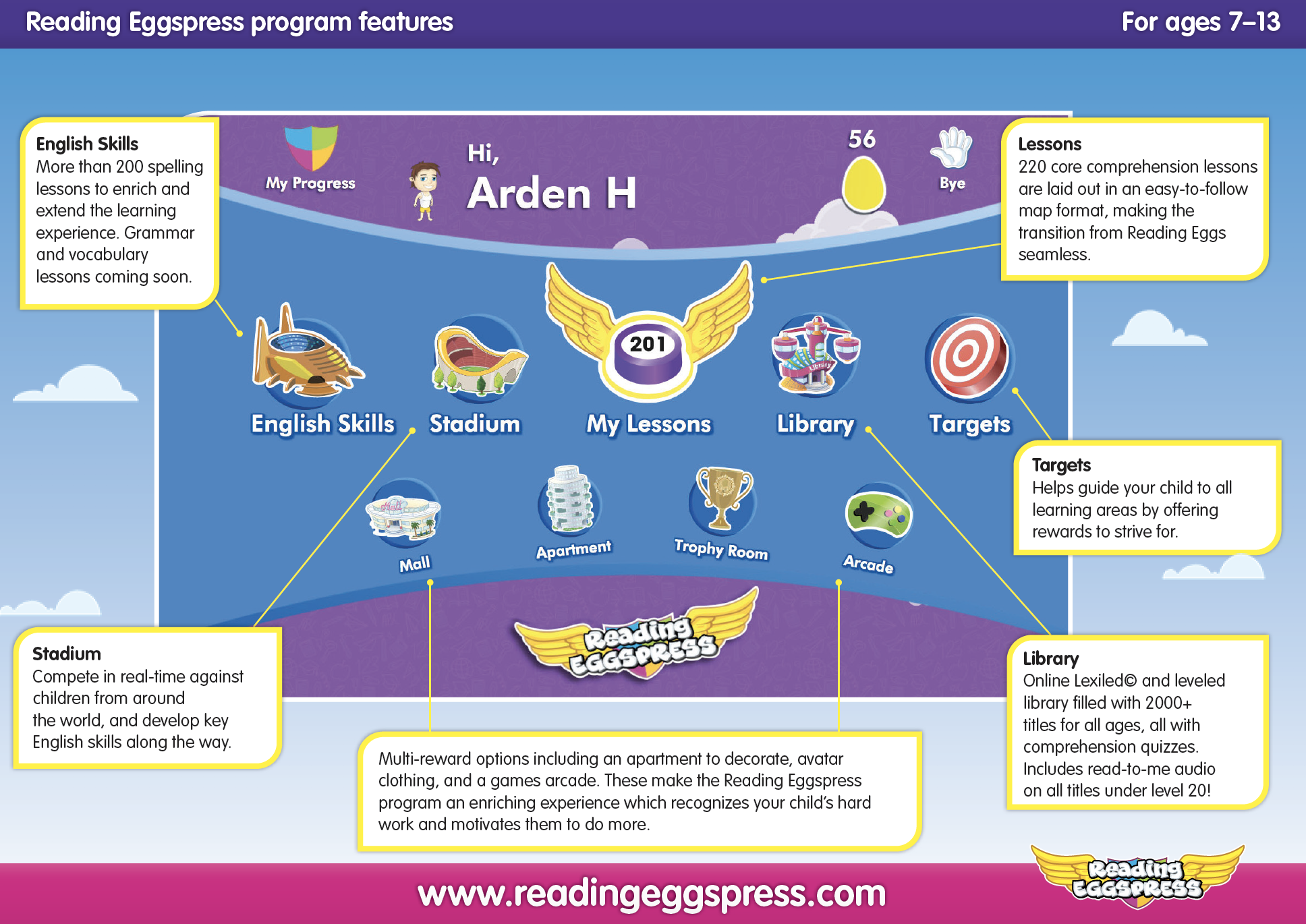

Did you know? The Reading Eggspress Vocabulary program focuses on the critical Tier 2 and academic vocabulary terms that students need to understand to be able access the increasingly difficult texts they encounter. The lessons are organised in a systematic and easy to follow format with technology that adapts to student responses.

Learn more about Reading Eggspress (part of Reading Eggs) vocabulary program here

Take me there

Vocabulary development by age

Students’ communication abilities, including their vocabulary, can vary immensely. However, there are certain milestones we can expect children to reach before starting formal schooling:

- 12 months: 2 words plus mummy/mommy and daddy (or equivalent in languages other than English)

- 18 months: 10-50 words

- 2 years: 300 words

- 5 years: 450 words

- 3 years: 1000 words

- 4 years: 2000 words

- 5 years: 5000 plus words

This early language acquisition is an essential platform for future learning. There is a huge body of evidence suggesting that deficient early vocabulary development is a strong marker for a continued difficulty in all aspects of schooling.

During the school years, vocabulary size must grow at a rapid pace in order to equip students for everyday, as well as academic, communication. By the age of 17, students are expected to know between 36 000 to 136 000 words.

So just what is it that allows some students to learn a staggering 100 000 more words than their peers?

Teaching vocabulary

Effective vocabulary instruction within the 6M Learning Framework includes opportunities to motivate, model, master, magnify and maintain vocabulary knowledge with meaningful feedback guiding the sequence of learning.

Motivate

Students need to understand the benefits of a rich vocabulary knowledge. As with all teaching, some students may be naturally curious, while others will need to be coaxed into the journey. Some tips and tools for enhancing motivation are:

- Take the time to demonstrate the value of a rich vocabulary knowledge

- Make word exploration an integral part of classroom culture

- Create a word-rich environment

- Find puns, jokes and other comedic devices to add engagement to word studies, especially those that humorously interchange multiple meanings

- Designate a word of the week with a challenge to use it creatively in that week’s work

Model

In an explicit approach to vocabulary instruction, teachers should model the skills and understanding required to develop a rich vocabulary knowledge.

Say the word carefully. Pronunciation is critical to allow students to make strong connections between written and spoken language. Use syllabification to assist in articulating each part of the word.

Write the word. There is a strong correlation between spelling and vocabulary. To allow students to access their vocabulary in both passive and active contexts, they must be equipped to spell new vocabulary.

Give a student-friendly definition. The concise nature of dictionaries means they require significant vocabulary knowledge to interpret. Simply providing students access to dictionaries and thesauruses will not necessarily give them the information they need to understand the meaning of the word. Provide a definition that is meaningful for students, their experiences and their existing vocabulary knowledge.

Give multiple meaningful examples. Use the word in sentences and contexts that are meaningful to students. But don’t stop at one! Provide a wide range of examples to allow everyone to connect and relate to the word.

Ask for student examples. It may be valuable to have students attempt to articulate their own examples of the word in context. By including this in the explicit teaching phase, there are opportunities to clarify understanding when words have multiple meanings and deal with any misconceptions.

Master

Provide opportunities for students to master an understanding of new vocabulary in context through hearing, saying, reading and writing.

Using words is the best way to remember them. The following methods can help learners to consolidate their vocabulary knowledge:

Show students how to recognise new words

The best way to help students to remember and retain the new words they’re introduced to is to connect it with an object in the real world. Pictures and flashcards are good, but real-world items are even better. This can get difficult with more abstract words, but by dedicating more time and thought, the image or object used, and your explanation of it, will help build students understanding.

Reinforce their remember new words

After a word has been introduced, we want students to see it at least 10 more times so it sticks. Activities like ‘fill in the blank’ and ‘word bingo’ help students make strong connections between the introduced words.

Have them use their new words

After new words have been introduced, students are ready to find the ways they can use these words to make meaning. Activities like using the word in a sentence, mind maps, fill in the blanks (with no options) develop students’ use of words as tools for meaning and communication.

Graphics organisers

A simple graphic organiser can be an effective method to help students master their knowledge of new words.

Magnify

Magnify vocabulary understanding through a word rich environment. Create a classroom where words are valued. Provide continued opportunities to explore words at a deep level.

- Explore word origins

Investigate the etymology of words and help students make connections within and between words. Understanding of common word parts helps learners to grasp meanings, even of words they have not encountered before.Create word families based on a particular etymological feature. For example, find words with ‘aqua’ or ‘hydra/o’ in their spelling – both referring to water. Predict the meanings of these words based on their smaller parts. - Explain the word’s connotation

This is the relationship between the word and the feelings about it, whether positive, neutral or negative. Understanding how words can be interpreted enables students to use them with greater precision.Try compiling a word scale. Place a word on one end of the scale and a word with opposite meaning or intensity at the other. For example, if students are struggling to use words instead of ‘said’, place the word ‘whisper’ at the lower end and ‘bellow’ at the higher end. Students work together to build the scale, searching for synonyms like ‘shout’, ‘yell’, ‘plead’, ‘intone’ and placing them at appropriate points on the scale. - Explaining where and when the word is or isn’t used

This can be anything from a word’s formality to its datedness. You might use ‘loo’ at home, ‘toilet’ in public or ‘lavatory’ at the Mayor’s Ball, and ‘ball’ would be outdated. This helps students understand how words can make people sound. Try demonstrating this by writing an inappropriately informal text to highlight the importance of word choice. Alternatively, write an overly formal text to convey a simple, friendly message. - Building the relationship from words to other words

This is how students understand what words have the same, similar, opposite or related meanings. Taking them through words synonyms, antonyms and words or concept that build off words helps them develop their lexical stores. Set aside time for word study. Provide graphic organisers to assist learners to make comparisons and build connections. - Showing what words occur together

This is called ‘collocation’ – it’s why we say ‘see the big picture’ instead of ‘see the tall picture’ or 10 apples is fewer than 15 apples rather than less. Collocation must occur in context, so shared reading is an excellent forum for this sort of word study. But also have a bit of fun by using synonyms to create ‘nearly but not quite’ versions of well-known sayings. - How affixes change meaning

Most words can be changed by adding affixes – prefixes before the word and suffixes after the word. But a rich vocabulary can be developed by understanding the purpose of prefixes and suffixes and how they impact part of speech and inform meaning.To help students get to grips with affixes and how they can change meaning, select a ‘friendly’ root word and explore all of the word building creations that are possible. For example, the word ‘social’ can be added to create: socialise, socially, unsocial, antisocial, unsociable, etc.

Maintain

Maintain learning through repeated practice and revision.

There are many great game ideas to help you find creative ways to revisit learning after one day, one week and one month.

Bonus strategies for teaching vocabulary

1. Word of the day

Create a daily roster for students to share a newly discovered or unusual word with the class. They can get creative with the definition too by acting it out, giving synonyms, or doing a Pictionary style drawing on the board.

2. Creative writing

Compile the week’s ‘words of the day’ and task students with writing a story that uses as many of them as possible. They’ll learn how to use their new vocabulary in context.

3. Class glossary

Build up a list of unfamiliar words the class encounters when reading a text or studying a topic. Each student can choose a word and create a glossary page for it, complete with a definition, pronunciation guide, sentence example, mnemonic (memory aid), and an image that sums up its meaning.

The challenges of teaching vocabulary

Explicit teaching of vocabulary is frequently overlooked in the busyness of the typical classroom.

Many teachers believe that vocabulary can be acquired without the need to provide targeted instruction. Others teachers are unaware of the need to teach vocabulary explicitly. Some lack the training or understanding of the skills involved. And some are simply overwhelmed by the competing voices of education priorities.

In a world where information is always available, some teachers simply provide access to the resources that students can use to build their vocabulary independently – such as dictionaries, thesauruses and online tools.

And while the end goal is autonomous and independent learners, students already struggling with a low vocabulary need significant support and explicit teaching to use these tools effectively.

The complexity of the English language presents homophones, homographs, polysemous words (words with multiple meanings) as well as the confusion of everyday words being used in idiomatic and figurative contexts.

It is essential for teachers to support students in their acquisition of a growing vocabulary. But to do so, they must themselves be equipped with a rich vocabulary and a deep understanding of the richness and value of words.

Looking to build your students’ vocabularies?

Reading Eggspress Lessons use a combination of teaching videos, engaging online activities and games with printable worksheets and assessment tests. The program includes a variety of instructional strategies including: word building, word sorts, word mapping, morphemic analysis, context reading, word consciousness and deep understanding and close reading of text.

Sources

The Three Tiers of Vocabulary Development – ASCD.org

Concept Development and Vocabulary – Education Victoria

Reading wars, Whole word VS. Phonics, whole language advocates vs. phonetics enthusiasts…

Who would imagine that learning to read could be such a controversial topic?

But sadly, it is!

And I use the word SADLY for a good reason: Because the ones that normally pay the consequences of this disagreement are our children!

In this article we will look at the differences between the whole word approach and the phonics approach, so you can learn the ins and outs of this hot debate and form your own opinion.

If your child is learning to read, this is a crucial topic for you to understand as a parent. The reading success of your child can depend very much upon the actual approach used to teach your child to read; and, as you will discover on this article, schools do not always use the most effective method.

When it comes to teaching children to read there are two main teaching methods.

These two main methods are the whole word approach (also called the “sight words” approach) and the phonetic or phonics approach.

Some prefer the whole word method, while others use the phonics approach.

There are also educators that use a mix of different approaches.

But, who is right?

The Whole Word Approach

The whole word approach relies on what are called “sight words”. This method basically consists of getting children to memorize lists of words and teaching them various strategies of figuring out the text from a series of clues. Using the whole word approach, English is being taught as an ideographic language, such as Chinese or Japanese.

One of the biggest arguments of whole word advocates is that teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables which have no actual meaning. Yet they fail to acknowledge that once the child is able to decode the word, they will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning. So, in practicality, this is a very weak argument, from our point of view.

Unlike Chinese, English is an alphabet-based language. This means the letters of the English alphabet are not ideograms (also called ideographs), like Chinese characters are.

An ideogram (or ideograph) is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or a concept. Simply put, ideograms are like logos.

So, in a way, you could say that in the Chinese language you need to teach children to memorize “logos” and the meaning of each of them.

It is not logic to think that English should be taught using an ideographic approach…

So, the very popular reading programs that use a whole word approach simply get children to memorize words using different strategies, but without teaching any proper decoding methodology.

Think of the example we used before of the logos and the Chinese language.

Besides, there is no scientific evidence to suggest that teaching your child to using the whole word approach is an effective method. However, there are large numbers of studies which have consistently stated that teaching children to read using phonics and phonemic awareness is a highly effective method.

The Whole-Word Approach in Schools…

So, is your child learning to read using sight words? Or maybe a mixture of phonetics and sight words? What is the standard approach in our education system?

Well, every country – and even every educator / school – is different.

However, in English speaking countries in general -with the exception of the UK, which has been encouraging schools to adopt a systematic synthetic phonics approach since 2011- reading instruction is normally more heavily weighted towards the teaching of sight words, emphasizing the learning of “word shapes”.

Despite all the evidence to suggest otherwise, the whole word method of teaching still dominates how reading is taught at schools.

Why? Well, our guess is that children can appear to make fast progress with the whole language approach, and that makes everybody happy…

That is until their progress stalls, which is what usually happens, because with this method many children do not learn the relationships between letters and sounds correctly.

Some children can finally understand the letter-sound relationships from the words they have learned, but unfortunately many children aren’t able to figure this out. So, they are left with only one strategy for learning to read: memory and continuous repetition.

This is a very poor strategy these children are left with, in our opinion.

On the other hand, the reading ability of children is normally exaggerated on whole word programs as the texts used are very repetitive and extremely predictable. The children know what to expect. So… They are basically guessing!

When children are presented with a less predictable text without pictures, they struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text with illustrations.

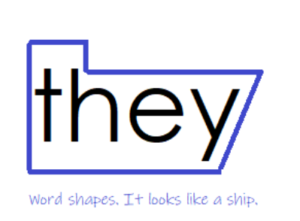

Another strategy used in whole word programs consists of focusing on word shapes.

Just have a look at this image. This is a “reading strategy” used on whole word programs.

Encouraging children to learn to read by looking at word shapes is completely madness! They are told to look at words as if they were “pictures”, focusing on the overhangs in the shapes of words! This does not apply for the English language!! Again, this is a method used for ideographic languages, such us Chinese or Japanese.

It does not make sense! There are just so many words with very similar shapes!

For example, look at this:

- hat vs. bat

- tree vs. free

- fall vs. tall vs hall

- hunt vs. hurt vs. hard

And the list goes on and on and on… Honestly, we could find thousands of words that have similar shape if we had the time to do this exercise!

The Whole- Word Method and Spelling

Even if a child has some early success learning to read using whole words programs, it gets him/her into the habit of ignoring the letters in words. This causes serious reading problems later on (when texts get more complicated), including spelling problems.

Another strategy that we are told to do on whole word programs is encouraging our children to look at the pictures in storybooks to “guess” or “predict” words.

-

Can they use the picture to help?

-

Can they look at the initial letter and predict what word would make sense that starts with that letter?

-

What word makes sense based on the context?

A little bit of history on the Whole-Word Approach

The main idea behind this theory is that if you see words enough number of times, you eventually store them in your memory as visual images.

They also embrace the idea that kids can naturally learn to read if they are exposed a lot of books.

Since the 1980s, these beliefs had strongly influenced the way children in North America and most English speaking countries are taught to read and write.

These ideas start to emerge in the 1970’s, and they become extremely popular for teaching reading in the 80’s and 90’s.

There is a strong focus on meaning, rather than sounds.

The Phonics Approach

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we find reading instruction based on phonemic awareness and phonics.

The phonics approach focuses on the sounds in words, which are represented by the letters (or groups of letters) in the alphabet.

There is a myriad of methods and systems within the phonics approach itself, but the the two main methodologies for teaching phonics are Synthetic and Analytic phonics.

Even though they both have the label “Phonics” attached to them, they are in fact quite different ways for teaching children to read.

However, for the sake of this article (and to keep things simple) we will just say that the main difference is that in the Synthetic Phonics approach skills are taught in a highly structured ‘systematic’ way.

Children start with very simple sounds and decoding regular words. Gradually, they are introduced to more complex sounds (such us letter combination sounds) and to irregularities and exceptions. Every step of the way is planned, and children only move to the next stage of phonics once they have mastered the previous one.

In the Analytic Phonics approach, reading instruction is less structured, and learning happens in a more ‘embedded’ fashion. Children are encouraged to analyze groups of whole words to identify similar sounds and letter patterns. Instruction relies a lot on the analysis of “families of words”.

For instance, the family of words ending up in -all, such us “tall, fall, mall, hall, small”, or the family of words ending up in -at, such “mat, cat, rat, bat, fat, pat”.

If you are interested in knowing more about the differences between analytics and synthetic phonics, you can check this video.ç

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/twDjIsFkhFM” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Is there a Winner in the Reading Wars?

What Research / Modern Science has to say…

The best way to put an end to this controversy and start making decisions that are RIGHT for our kids – and not based on personal preferences or ideology- is by looking at what research and scientific studies have to say.

However, you may think that if opinions on the topic are still so divided, then it must be that the results of these studies are somehow inconclusive.

Well, not really…

Look at these statements by the US National Reading

“Teaching children to manipulate phonemes in words was highly effective under a variety of teaching conditions with a variety of learners across a range of grade and age levels and that teaching phonemic awareness to children significantly improves their reading more than instruction that lacks any attention to Phonemic Awareness.”

“Conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.”

^* Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Excerpts from the meta-analysis of over 1,900 scientific studies.

Overwhelmingly research has found that phonemic awareness and phonics is a superior way for teaching children to read!

But wait there is more…

Modern Scientific Research on the Brain and How we learn to read

For a very long time many experts have embraced the idea that we store words in our memory in the same way we store visual memories, such us faces or objects. That belief is at the core of the whole word approach.

And, in fact, many reading experts still believe this is the cse.

However, modern scientific research proves otherwise…

But before I tell you how we actually store words in our memory, look at the following factors already pointing out at how visual memory -contrary to still popular belief – is NOT involved:

-

We can read mixed case letters without difficulties.

-

We can read words with different fonts, in print and cursive, and handwritting without difficulties.

-

Word recognition works faster than object recognition, indicating that we are using different storage and retrieval processes.

Let me tell you about the sound scientific evidence now…

Brain scans show that the parts of the brain activated while performing visual memory tasks are different than the parts of the brain activated while reading…

Moreover, scientists in the visual memory area (not related to reading research, therefore unbiased) have indicated that we don’t have the cognitive capacity to remember 30 – 90,000 words for immediate retrieval.

As reading instruction still assumes that we store words as visual images, students who struggle to remember words are many times presumed to have poor visual memory.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. There is only a small relationship between visual memory and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading.

However, there is a very strong relationship between HEARING skills and our capacity to store words for immediate retrieval while reading (fluent reading capacity).

To be more specific, children that have been trained to hear the actual sounds that form words (phonemic /phonological skills) and are capable to recognize and store those common strings of sounds and visually link them to the letters / words they know become fluent readers.

There is no evidence to suggest that visual memory has a role in word recognition /reading fluency once the letters and the connection between letters and sounds have been learned.

If there seems to be a winner on the ‘Reading Wars’, why do we keep arguing?

Phonics instruction cons…

These are the main arguments against phonics instruction:

- Children only read phonics books: This is one of the main pillars of a proper phonics system. Children should only attempt to read books that are in line with their level of phonics. Otherwise, it is overwhelming for them and can get confused, since they may be exposed to too many exceptions and irregularities. While this is true, that doesn’t mean that parents can’t read more difficult books to their children. And, in fact, they are encouraged to do so.

- Phonics doesn’t help with reading comprehension. Besides, teaching to read using phonics breaks up the words into letters and syllables, which have no actual meaning. However, once the child is able to decode the word, he/she will be able to actually read that entire word, pronounce it and understand its meaning.

- Children learn to read naturally, therefore they don’t need tedious phonics instruction. Whereas it is truth that some children can learn to read by themselves, most won’t be able to figure it out. Besides, there is no harm in receiving phonics instruction for those that are able to learn to decode by themselves.

- There are just too many exceptions and irregularities in English. While it is true that English is full of irregularities and exceptions, there are less of these than what we are led to believe. Besides, there are some rules, patterns and tips and tricks that apply to those “irregular” words that certainly do help in the process of learning to read.

So, saying that phonics has won the war is quite far from what happens in reality.

As we stated at the beginning of the article, there are different ways for teaching phonics.

What our schools have evolved to do to keep both sides of the war happy is establishing a “balanced literacy” strategy that combines both whole word and phonics principles.

What in practicality ends up happening is that there is only a little bit of phonics instruction here and there, rather than a proper curriculum based on phonics.

That is an ineffective method for teaching phonics, and certainly doesn’t work. And this is precisely the sort of evidence that whole word enthusiasts hold on to.

Final thoughts on the Reading Wars

The debate is still hot. This is bizarre as, in our opinion, based on the latest scientific evidence, the number one skill that we need to develop in our children is phonemic awareness.

This way we would have far fewer students with reading difficulties.

And, after having developed strong phonological / phonemic awareness skills, using a proper phonics approach (and not just a little bit of phonics instruction here and there) seems like the way to go.

Free Resources you may be interested in!

Phonemic Awareness Activity Worksheets

Nursery Rhymes Ebook

44+ English sounds chart

List of CVC Words

The theory and techniques for teaching vocabulary may not be as fun as the ideas that I’ll share in the next post or as perusing the books in the last post, yet this is the theory applicable to all ages and types of readers. It is the knowledge that will enable you to choose the right activities and strategies for your content and grade level.

PURPOSES FOR TEACHING VOCABULARY

In my experience, we teach vocabulary for a variety of reasons. It’s important to think about the vocabulary instruction in your teaching practice by considering why you are doing it. That will help you determine which theories and techniques you should use (or at least try).

Reasons include:

- Improving reading comprehension in general.

- Improving subject-specific mastery and performance.

- Improving writing and speaking skills.

- Test preparation (SAT, ACT, etc.).

- Deepening students’ ability to put their thoughts into the most appropriate word possible.

These techniques and theories are in no particular order.

This post is Part 2 of a four-part series on teaching vocabulary. If you would like to check out the rest of the series, visit the posts below

- Teaching Vocabulary: The books

- Theories & Techniques that work (and don’t) (this one)

- 21 Activities for Teaching Vocabulary

- Ideas for English Language Learners

EXPOSURE RATES MATTER

Students need to be exposed to the vocabulary over and over if they are to understand and use the words effortlessly. When stories or texts are repeated, students gain more word knowledge.

Research shows that students hearing stories more than once have a 12% gain over their peers who only heard the story one time when tested on the vocabulary in context.

Want to read the research? Look for the studies done by Biemiller and Boote (2006) and Coyne, Simmons, Kame`enui, and Stoolmiller (2004).

DEFINE THE WORDS WHILE YOU READ

It works better to share vocabulary in context, rather than just learning definitions. Giving students lists of words and having them look up the definitions is useless and ineffective. You’re shocked, aren’t you?

It’s also important to emphasize and practice pronunciation of new/unfamiliar words. Don’t assume that regular decoding skills will work with academic vocabulary. Practice saying the words.

Want to read the research? Look for the study done by Nash and Snowling (2006).

TIERED WORDS: VOCABULARY IN THE CORE

To decide whether or not a word from a story or lesson should be directly taught, consider:

- Is it unfamiliar but able to be understood?

- Is it necessary for comprehension?

- Does it appear in other contexts?

- Is it likely to show up again?

One particular model divides words into three categories, or tiers. This model was developed by Isabelle Beck in Bringing Words to Life.

- Tier One words are the words of everyday speech usually learned in the early grades. These are not necessary to teach explicitly (except for in ELL acquisition).

- Tier Two words are what the Common Core standards refer to as academic words. They are more to be read by students in texts that heard in conversations. They may be in informational or technical texts, or in literary works with sophisticated vocabulary. They often make language more precise (saying “wended their way” instead of “walked along,” for example). They are words that cross domains, so you may see them in a variety of disciplines.

- Tier Three words are the domain-specific words that you would only see in relation to a specific content area. They are the ones you see bolded in textbooks and/or listed in the glossary.

You can watch a video about this at Engage NY.

(Note: The words that she mentions in the beginning of the video that you would see only in certain areas are Tier Three words.)

ASK QUESTIONS

Students learn the vocabulary best when teachers actually integrate questioning and discussion into lessons, rather than just defining them.

Here are some example questions:

- What other words do you know that are similar to this word?

- How can we use this word in [insert other thing you’ve studied]?

- Do you recognize any of the parts of this word?

- If I said that [insert another word here] is the same or similar as this word, would that be true?

Want to read the research? Look for the study by Ard and Beverly (2004).

THE FOUR COMPONENTS

Michael Graves argues that there are four components of an effective vocabulary program:

- Teach individual words: Teach new words explicitly, meaning on purpose. Make sure students understand the definition. Make sure the definitions are in student-friendly vocabulary. It doesn’t help you to understand a word if you don’t know the words in the definition, either. Show the word in a variety of contexts. Have students generate their own definitions. Have them engage with the words interactively, playing with them. Vary the methods so you’re not teaching the same way for every word.

- Provide rich and varied language experiences: We need reading, listening, speaking, and writing experiences across multiple genres. Yes, there is math poetry. Read out loud to students. Encourage book clubs and reading challenges. The idea: create an environment saturated with words.

- Teach word-learning strategies: Teach students how to infer word meaning from context clues. Teach students how to infer meaning from morpheme clues. Teach students how and when to use a dictionary and a thesaurus. We can’t assume that students know the strategies they need to make sense of words.

- Foster word consciousness: Point out useful, beautiful, powerful, or painful lessons. Be playful with words.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

When testing students’ command of vocabulary, use a self-assessment that is non-judgmental, using prompts such as:

- I have never seen or heard the word before.

- I’ve seen or heard the word, but I don’t know what the word means.

- I vaguely know the meaning.

- I can associate the word with a concept or context.

- I know the word well.

- I can explain and use it in general or in writing.

- I can explain and use it with a full and precise meaning.

EASE METHOD

- Enunciate new words syllable-by-syllable and then blend the word.

- Associate the word with definitions and examples that students already know.

- Synthesize the words with other words and concepts that they have already studied and they have the opportunity to demonstrate deep knowledge of the new word.

- Emphasize new words in classroom discussion.

SIX STEP MODEL OF VOCABULARY INTRODUCTION

- Step one: The teacher explains a new word, going beyond reciting its definition (tap into prior knowledge of students, use imagery).

- Step two: Students restate or explain the new word in their own words (verbally and/or in writing).

- Step three: Ask students to create a non-linguistic representation of the word (a picture, or symbolic representation).

- Step four: Students engage in activities to deepen their knowledge of the new word (compare words, classify terms, write their own analogies and metaphors).

- Step five: Students discuss the new word (pair-share, elbow partners).

- Step six: Students periodically play games to review new vocabulary (Pyramid, Jeopardy, Telephone).

DICTIONARIES

Use dictionaries to work with words that already somewhat familiar. It is not helpful to have students try to look up words they can’t spell.

WHAT DOESN’T WORK

Kate Kinsella’s ideas of what doesn’t work include:

- Incidental teaching of words

2. Asking, “Does anybody know what _____ means?”

3. Copying same word several times

4. Having students “look it up” in a typical dictionary

5. Copying from dictionary or glossary

6. Having students use the word in a sentence after #3,4, or 5

7. Activities that do not require deep processing (word searches, fill-in-the-blank)

8. Rote memorization without context

9. Telling students to “use context clues” as a first or only strategy or asking students

to guess the meaning of the word

10. Passive reading as a primary strategy (SSR)

Watch a video of her teaching about vocab instruction and find related activities here.

IDEAS FOR TEACHING VOCABULARY

This article has focused on the theory of teaching vocabulary. Be sure to check out the third article in the series for loads of activities for teaching vocabulary in your classroom.

- Teaching Vocabulary: The books

- Theories & Techniques that work (and don’t) (this one)

- 21 Activities for Teaching Vocabulary (the one with loads of activities!!!)

- Ideas for English Language Learners

THE ULTIMATE METHOD FOR TEACHING ACADEMIC VOCABULARY

I think academic vocabulary is so important that I’ve spent decades perfecting a method of teaching it that works like a dream! It’s called the Concept Capsule method, and I’ve written an entire book about it.

Find out more here (and get a 50% discount for reading this article!).

Note: This content uses affiliate links, which means that if you order one of the things I recommend, I may geta a small commission.