Globally, English is one of the most spoken and popular languages. Many English speakers believe that other cultures will understand the English words they use, without realizing that some of the words in English have different connotations or meanings in different languages. Many of these English words are the same in spelling, for example in German, Dutch, Polish, Spanish, Sweden and many other languages, but they have different meanings.

Other words sound like English words with a slight difference in pronunciation, such as taxi, which in Korean is taek-si (pronounced taek-shi).

False friends

The words may be similar due to them coming from the same language family or due to loan words. In some cases they are ”false friends” meaning the words stand for something else from what you know.

- In English “to use the voice,” means to say something “aloud.” In Dutch, aloud means “ancient”

- The English word “angel” means a supernatural being often represented with wings. Angel in German translates to ”fishing rod” and ”sting” in Dutch.

- You mean something not specific or whatever when you say “any.” But in Catalan, it is equivalent to “year” although others use the word “curs.”

- The arm is an upper body extremity but for the Dutch it is the term used when they mean “bad.” But the English term ”bad” is equivalent to ”bath” in Dutch.

- Bank could be an institution where people deposit their money, something or someone you trust or the sloping land close to a body of water. For the Dutch, ”bank” means cough.

- An outlying building in a farm is called ”barn,” which is the term for ”children” in Dutch. On the other hand the English word ”bat” refers to a flying mammal or a club used to hit a ball. In Polish, the word means, ”whip.”

- Beer in English means a ”bear” in Dutch, while they use the term ”big” to refer to a ”baby pig.”

- “Car in a motorized vehicle, but for the French, it means ”because.” A chariot for the English speakers is a horse-drawn vehicle or a carriage, but the French use this term to mean something smaller, like a ”trolley.”

- You use the term ”chips” when you mean ”French fries” while the French use ”Crisps” when they say chips.

- Donkey in Spanish is ”burro” whereas for the Italian, it means ”butter.”

- The English word ”gift” means ”poison” in German and Norwegian and ”married” in Swedish.

- “Home” is where you live, but it means ”mold” in Finnish and ”man” in Catalan.

- “Panna” is cream in English and in Italian, but means ”put” in Finnish. In Polish, they use the term it indicate “a single woman.”

- The Spanish term for frog is “rana,” but rana means, ”wound” in Romanian and Bulgarian.

- “Sugar” is something sweet and it’s a sweet term used by Romanians for a baby aged 0-12 months. But the speakers of Basque use the term to mean ”flame.”

- Tuna is a large fish that is a Japanese favorite when making sashimi. The term means ”cactus” in Spanish or a ”ton” in Czech.

- “Fart” is a vulgar English word that means expelling intestinal gas. But it means ”good luck” in Polish and ”speed” in Swedish. In French, though, ”pet” is the translation of ”fart” (yes, the foul-smelling variety).

- Cake in Icelandic is ”kaka” but it is an ”older sister” in Bulgarian. “Kind” means ”child” in German but ”sheep” in Icelandic.

- You’re likely to say ”prego” when you’re in Italy instead of the usual ”thank you” but it means something very mundane in Portuguese. In Portugal, it is the term they use for ”nail.”

- ”Privet” is a type of evergreen shrub or small tree that you can use as a border wall. But in Russian, privet, which means ”greetings,” is informally used to say ”hello.”

- Watercress is a salad green that is called ”berros” in Spanish. The Portuguese however has a very different meaning to berros. To them, it means scream.

- When you hear the Swedes say ”bra,” they mean ”good,” instead of a type of women’s underwear.

- “But” is a conjunction in English, whereas the Polish use the term to indicate ”shoe.”

- This one is a bit similar. The term ”cap” is the Romanian word for ”head.” We say ”door” when we mean the opening to gain access into a room or the panel that opens and closes an entrance. Door in Dutch is almost similar, as it means ”through.”

- ”Fast” in German means almost, while ”elf” means the number eleven. ”Grad” is the German term for ”degree” but means a ”city” in Bosnian.

- Make sure you remember this. When is Spain, “largo” means ”long” but it means ”wide” in Portuguese.

- The meaning of ”pasta” is very different in Polish and Italian. In Italian it is the term for ”noodles,” while in Polish, it means ”toothpaste.” When you’re in Norway, “sau” means sheep while in Germany, it means sow (female pig). “Pig” is ”gris” in Swedish while in Spanish, gris means ”gray.”

- “Glass” is something shiny, hard and brittle in English, but it turns to soft, cold, sweet and gooey ”ice cream” when you’re in Sweden.

- The Italians use the word ”vela” when they mean, ”sail.” In Spain though it means ”candle.”

- The number six in Spanish is ”seis” and for the Finnish, they say this when they mean, ”stop!”

- The big, blue ”sky” means ”gravy” in Swedish, while ”roof” means ”robbery” in Dutch.

- When a Swedish says, ”kiss,” it means ”pee” instead of caressing with the lips.

- “Carp” is a fish beloved in Japan and it is a type of freshwater fish found in Asia and Europe. But in Romanian, the carp is called ”crap.” Hmm…

- Trombone is a musical instrument. It is the instrument of choice for some of the famous artists such as Joseph Alessi, J.J. Johnson, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey and Frank Rosolino. But in French, it is something very ordinary – a paper clip.

- “Awesome” in German is “hammer.”

- “Barf” means ”snow” in Urdu, Hindi and Farsi.

Be careful with your words

Words can hurt other people if you are not careful. English speakers who love to travel should take time to learn the culture and read about the quirks and characteristics of the main language spoken in their destination. They should know that some words in a foreign language might sound like English but stand for something different in another language.

If you are in Wales, do not feel slighted when you hear a Welsh-speaking native say ”moron” while you’re in the market. The person might be trying to sell you some ”carrots.”

In English, you can say you ”won” something and feel proud or happy. In South Korea, it is their national currency. When a house is said to be ”won” in Polish, it means that it is ”nice smelling.” Russia has a different interpretation, however. In Russian, using the word ”won” means describing something that ”stinks.”

The Spanish term ”oficina” translates into ”office” in English. But for the Portuguese, an ”oficina” is only a ”workshop,” such as a mechanic’s shop.

The term ”schlimm” sounds like ”slim” in English. In the Netherlands, this stands for being smart or successful. But in Germany, which is 467.3 kilometers away from the Netherlands by car via A44, (roughly a five-hour drive), schlimm means ”unsuccessful and dim-witted!

English speakers understand that ”slut” is a derogatory word. But for the Swedish, this means ”finished” or the ”end,” something that you’d say when you want your relationship with your Swedish boyfriend or girlfriend is over. So when you’re in Sweden, you’ll see signs such as ”slutspurt” that means a final sale or ”slutstation” when you’ve reached a train line’s end.

If you’re an urbanite, it is difficult to enjoy fresh air unless you go to the countryside. “Air” in Malay (sounds like a-yah), which is an official language in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei, it means ”water.” When you mean the ”air” you breathe, you use the word ”udara.”

In English and in German, the word ”dick” is derogatory. It means ”fat” or ”thick” in German.

You might think that the Spanish appetizer ”tapas” is universally understood when you’re in South America because you are so used to seeing tapas bars in the U.S., UK, Canada, Mexico and Ireland (or their own version of it). However, in Brazil, where Portuguese is an official language, ”tapas” means ”slap” rather than a delicious snack. If you want to have tapas-like snacks to go with your beer, the right term to use is ”petiscos” or ”tira-gostos.” Now you know the right term to use when you’re in Brazil. If you go to Mexico, you can order ”botanas” and ask for some ”picada” in Argentina or ”cicchetti” if you happen to be in Venice. In South Korea, tapas-like appetizers are called ”anju.”

Sounds like…

In Portuguese, the word ”peidei” that sounds like ”payday” means, ”I farted.”

Salsa is a wonderful, graceful and thrilling dance style, but in South Korea, when you hear the word ”seolsa,” which sounds like ”salsa” it refers to ”diarrhea.”

Speaking of diarrhea, in Japanese, the term they use is ”geri,” which sounds like the name ”Gary.”

”Dai,” an Italian word, is pronounced like the English word ”die.” The literal translation of this is ”from” but it is colloquially used by the Italians to mean, ”Come on!”

The English term ”retard” could either mean delay or move slowly. It could also mean moron or imbecile. In French, ”retardé” translates to delay as well.

There is an English term called a ”smoking jacket” which is a mid-length jacket for men that is often made of quilted satin or velvet. The French however call a ”tuxedo,” which is a semi-formal evening suit, ”smoking.”

“Horny” is an English term that is mostly associated to feelings of being aroused or turned on. Literally, it means something with horn-like projections, many horns or made of horns, such as ”horny coral” or ”horny toad.” But ”horní” in Czech simply means ”upper.”

In Spanish, ”gato” means ”cat” but ”gateux” is ”cake” in French.

Eagle is a soaring bird. In Germany, the word ”igel” that has a similar pronunciation to ”eagle” actually means ”hedgehog.”

Something else

The term ”thongs” is usually associated with sexy swimwear or underwear. When you’re in Australia though, thongs refer to rubber flip-flops.

In Polish, the month of April is ”Kwiecień” while in Czech, the similarly sounding term, ”Květen” is for the month of May.

For English speakers a ”preservative” is a chemical compound that prevents decomposition of something. But be careful when you say the word while in France, as this means ”condom” for the French. It means the same thing in many different languages in Europe as well, such as:

- Prezervativ (Albanian)

- Preservative (Italian)

- Prezervatīvs (Latvian)

- Prezervatyvas (Lithuanian)

- Prezerwatywa (Polish)

- Preservative (Portuguese)

- Prezervativ (Romanian)

- Prezervativ (Russian)

- Prezervatyv (Ukranian)

‘In Spanish, ”si” means yes, but ”no” in Swahili. “No” is ”yes” in Czech (a shortened version of “ano.” “La” is ”no” in Arabic.

”Entrée” is a French term that translates to ”appetizer.” In American English though, term is used to indicate the ”main course.”

“Mama” in Russian and in several other different languages means ”mother.” However, in Georgian, ”mama” is the term for ”father.”

Languages are definitely fascinating and interesting, but there is enough reason to learn a few things about it to avoid a faux pas when you are in another country, because English words could mean differently. Ensure that your English documents are translated accurately in different languages by getting in touch with a translator from Day Translations, Inc. Our translators are not only native speakers; they are also subject matter experts. Give us a call at 1-800-969-6853 or send us an email at contact@daytranslations.com for a quick quote. Our translators are located world-wide and we are open every single day of the year. We can serve you any time, wherever you are located.

Image Copyright: almoond / 123RF Stock Photo

The foreign words are the words which are adopted from the foreign languages. There are a lot of words and phrases taken from many other languages. The following table includes 60 most common foreign words and their meanings. The foreign words and phrases listed here are taken from Latin and French languages.

Home

About

Blog

Contact Us

Log In

Sign Up

Follow Us

Our Apps

Home>Words that start with M>meaning

How to Say Meaning in Different LanguagesAdvertisement

Categories:

General

Linguistics

Please find below many ways to say meaning in different languages. This is the translation of the word «meaning» to over 100 other languages.

Saying meaning in European Languages

Saying meaning in Asian Languages

Saying meaning in Middle-Eastern Languages

Saying meaning in African Languages

Saying meaning in Austronesian Languages

Saying meaning in Other Foreign Languages

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

Saying Meaning in European Languages

| Language | Ways to say meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Albanian | kuptim | Edit |

| Basque | esanahia | Edit |

| Belarusian | сэнс | Edit |

| Bosnian | značenje | Edit |

| Bulgarian | значение | Edit |

| Catalan | significat | Edit |

| Corsican | significatu | Edit |

| Croatian | značenje | Edit |

| Czech | význam | Edit |

| Danish | betyder | Edit |

| Dutch | betekenis | Edit |

| Estonian | tähendus | Edit |

| Finnish | merkitys | Edit |

| French | sens | Edit |

| Frisian | betsjutting | Edit |

| Galician | significado | Edit |

| German | Bedeutung | Edit |

| Greek | έννοια [énnoia] |

Edit |

| Hungarian | jelentés | Edit |

| Icelandic | Merkingu | Edit |

| Irish | rud a chiallaíonn | Edit |

| Italian | senso | Edit |

| Latvian | nozīme | Edit |

| Lithuanian | reikšmė | Edit |

| Luxembourgish | Bedeitung | Edit |

| Macedonian | што значи | Edit |

| Maltese | li jfisser | Edit |

| Norwegian | betydning | Edit |

| Polish | znaczenie | Edit |

| Portuguese | significado | Edit |

| Romanian | sens | Edit |

| Russian | имея в виду [imeya v vidu] |

Edit |

| Scots Gaelic | a ’ciallachadh | Edit |

| Serbian | значење [znachenje] |

Edit |

| Slovak | zmysel | Edit |

| Slovenian | kar pomeni, | Edit |

| Spanish | sentido | Edit |

| Swedish | menande | Edit |

| Tatar | мәгънәсе | Edit |

| Ukrainian | сенс [sens] |

Edit |

| Welsh | golygu | Edit |

| Yiddish | טייַטש | Edit |

Saying Meaning in Asian Languages

| Language | Ways to say meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Armenian | իմաստ | Edit |

| Azerbaijani | məna | Edit |

| Bengali | অর্থ | Edit |

| Chinese Simplified | 含义 [hányì] |

Edit |

| Chinese Traditional | 含義 [hányì] |

Edit |

| Georgian | რაც იმას ნიშნავს, | Edit |

| Gujarati | જેનો અર્થ થાય છે | Edit |

| Hindi | अर्थ | Edit |

| Hmong | lub ntsiab lus | Edit |

| Japanese | 意味 | Edit |

| Kannada | ಅರ್ಥ | Edit |

| Kazakh | мағына | Edit |

| Khmer | មានន័យថា | Edit |

| Korean | 의미 [uimi] |

Edit |

| Kyrgyz | мааниси | Edit |

| Lao | ຊຶ່ງຫມາຍຄວາມວ່າ | Edit |

| Malayalam | അര്ത്ഥം | Edit |

| Marathi | अर्थ | Edit |

| Mongolian | гэсэн утгатай | Edit |

| Myanmar (Burmese) | အဓိပ်ပါယျ | Edit |

| Nepali | अर्थ | Edit |

| Odia | ଅର୍ଥ | Edit |

| Pashto | معنی | Edit |

| Punjabi | ਮਤਲਬ | Edit |

| Sindhi | مطلب | Edit |

| Sinhala | අර්ථය | Edit |

| Tajik | маъно | Edit |

| Tamil | அதாவது | Edit |

| Telugu | అర్థం | Edit |

| Thai | ความหมาย | Edit |

| Turkish | anlam | Edit |

| Turkmen | manysy | Edit |

| Urdu | معنی | Edit |

| Uyghur | مەنىسى | Edit |

| Uzbek | ma’no | Edit |

| Vietnamese | Ý nghĩa | Edit |

Too many ads and languages?

Sign up to remove ads and customize your list of languages

Sign Up

Saying Meaning in Middle-Eastern Languages

| Language | Ways to say meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Arabic | المعنى [almaenaa] |

Edit |

| Hebrew | מַשְׁמָעוּת | Edit |

| Kurdish (Kurmanji) | mane | Edit |

| Persian | معنی | Edit |

Saying Meaning in African Languages

| Language | Ways to say meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | wat beteken | Edit |

| Amharic | ትርጉም | Edit |

| Chichewa | kutanthauza | Edit |

| Hausa | ma’ana | Edit |

| Igbo | nke pụtara | Edit |

| Kinyarwanda | ibisobanuro | Edit |

| Sesotho | e bolelang | Edit |

| Shona | zvinoreva | Edit |

| Somali | taasoo la micno ah | Edit |

| Swahili | maana | Edit |

| Xhosa | intsingiselo | Edit |

| Yoruba | itumo | Edit |

| Zulu | okusho | Edit |

Saying Meaning in Austronesian Languages

| Language | Ways to say meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Cebuano | nagkahulogang | Edit |

| Filipino | ibig sabihin | Edit |

| Hawaiian | manaʻo | Edit |

| Indonesian | berarti | Edit |

| Javanese | artine | Edit |

| Malagasy | izay midika hoe | Edit |

| Malay | yang bermaksud | Edit |

| Maori | tikanga | Edit |

| Samoan | uiga | Edit |

| Sundanese | hartosna | Edit |

Saying Meaning in Other Foreign Languages

| Language | Ways to say meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Esperanto | signifas | Edit |

| Haitian Creole | sa vle di | Edit |

| Latin | idest | Edit |

Dictionary Entries near meaning

- meal

- mealtime

- mean

- meaning

- meaningful

- meaningful way

- meaningless

Cite this Entry

«Meaning in Different Languages.» In Different Languages, https://www.indifferentlanguages.com/words/meaning. Accessed 13 Apr 2023.

Copy

Copied

Browse Words Alphabetically

Here is a list of 30 English words that have a different meaning in a foreign language.

1-5

1. The English word ‘fart’ means speed in Norwegian. Also ‘smell’ means impact. Example

2. The term for clarified butter is ‘ghee’ in English (which is derived from Hindi), which means sh*t in Kurdish.

3. The word ‘kiss’ means pee in Swedish.

4. The English word ‘preservative’ means condom in French (pronounced preservatif).

5. ‘Lol’ actually means ‘fun’ in Dutch. “We hebben lol” translates to “we are having fun.”

6-10

6. The English word ‘Crap’ means Carp (type of a fish) in Romanian. They sell fish-egg salad there and it looks like this.

7. ‘Lul’ as in ‘lulz’ means penis in Dutch.

8. ‘Sean Bean’ (the actor) means old woman in Irish although in fairness the pronunciation is different.

9. The English derogatory word ‘Slut’ means finish/close/end in Swedish, Norwegian and Danish. Example

10. ‘Brat’ means ‘brother’ in Russian (брат).

11-15

11. The English word ‘gift’ means poison in in German.

12. In Italian ‘dai’ sounds exactly like ‘die’ to English speakers and it means something like “come on!”

13. ‘Trombone’ means paperclip in French.

14. ‘Cut’ sounds like ‘kut’ in Dutch, which means c**t.

15. The word ‘retard’ means late In French. One might say “Désolé, je suis en retard!” when you’re running late for something.

16-20

16. ‘Puxe’ read as push in Portuguese means pull.

17. The word ‘smoking’ in French means tuxedo.

18. ‘Vader’ means father in Dutch.

19. The English word ‘f**k’ sounds like ‘phoque’ in French, which means a seal.

20. ‘Bra’ is Swedish means good.

21-25

21. English word ‘The Ace’ as in deck of cards or someone who is really good at something translates to ‘Das Ass’ in German.

22. The English word ‘fart’ means ‘pet’ in French.

23. Nah (as in no) sounds like “Nai” (Ναι) which means ‘yes’ in Greek.

24. English word ‘pig’ sounds like the Danish (also Dutch) word ‘pik’, which means d*ck.

25. The English word “Bite” means d*ck in French. Fortunately, it really sounds different (“bee-teuh”), so you don’t need to care that much.

26-30

26. The Finnish word for ‘bag’ is ‘pussi.’ If you want to buy a paper bag for your groceries, you politely ask for a paperipussi. Sometimes the stores advertise their new, larger bag types. That’s when you buy a megapussi.

27. The English word ‘manure’ is called ‘mist’ in German.

28. Common English named ‘Gary’ means ‘diarrhea’ in Japanese. If you said “I’m Gary” (ゲリです。), it would sound like “I have diarrhea.”

29. English word ‘louder’ in Hindi roughly means penis (Lau-da, to be precise).

30. In Hebrew ‘me’ means who, ‘who’ means he, ‘he’ means she and ‘dog’ means fish.

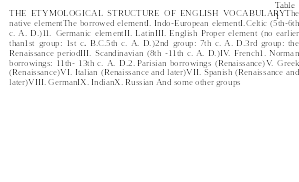

Lecture №2. Foreign Elements in Modern English. International Words

The term source of borrowing should be distinguished from the term origin of borrowing. The first should be applied to the language from which the loan word was taken into English. The second, on the other hand, refers to the language to which the word may be traced. Thus, the word paperhas French as its source of borrowing and Greek as its origin. It may be observed that several of the terms for items used in writing show their origin in words denoting the raw material. Papyros is the name of a plant; cf. book“the beech tree” (boards of which were used for writing).

Alongside loan words, we distinguish loan translation and semantic loans. Translation loans are words or expressions formed from the elements existing in the English language according to the patterns of the source language. They are not taken into the vocabulary of another language more or less in the same phonemic shape in which they have been functioning in their own language, but undergo the process of translation. It is quite obvious that it is only compound words (i. e. words of two or more stems) which can be subjected to such an operation, each stem being translated separately: masterpiece (from Germ. Meisterstück), wonder child (from Germ. Wunderkind), first dancer (from Ital. prima-ballerina), the moment of truth (from Sp. el momento de la verdad), collective farm (from Rus. колхоз), five-year plan (from Rus. пятилетка). The Russian колхоз was borrowed twice, by way of translation-loan (collective farm) and by way of direct borrowing (kolkhoz). The case is not unique. During the 2nd World War the German word Blitzkrieg was also borrowed into English in two different forms: the translation-loan lightning-war and the direct borrowings blitzkrieg and blitz: Eng. chain-smoker Ger. Kettenraucher; Eng. wall newspaper Rus. стенная газета; Ukr. настінна газета; Eng. (it) goes without saying Fr (cela) vasans dire; Eng. summit conference Ger. Gipfet Konferenz conference au sommet.

The term semantic loan, is used to denote the development in an English word of a new meaning due to the influence of a related word in another language, e.g. the compound word shock brigade which existed in the English language with the meaning «аварийна бригада» acquired a new meaning «ударная бригада» which it borrowed from the Russian language. Eng. pioneer — explorer; one who is among the first in new fields of activity; Rus пионер – a member of the Young Pioneers’ Organization. Each time two nations come into close contact, certain borrowings are a natural consequence. The nature of the contact may be different. It may be wars, invasions or conquests when foreign words are in effect imposed upon the reluctant conquered nation. There are also periods of peace when the process of borrowing is due to trade and international cultural relations. These latter circumstances are certainly more favourable for stimulating the borrowing process, for during invasions and occupations the natural psychological reaction of the oppressed nation is to reject and condemn the language of the oppressor. In this respect the linguistic heritage of the Norman Conquest seems exceptional, especially if compared to the influence of the Mongol-Tartar Yoke on the Russian language. The Mongol-Tartar Yoke also represented a long period of cruel oppression, yet the imprint left by it on the Russian vocabulary is comparatively insignificant.

The difference in the consequences of these evidently similar historical events is usually explained by the divergence in the level of civilisation of the two conflicting nations. Russian civilisation and also the level of its language development at the time of the Mongol-Tartar invasion were superior to those of the invaders. That is why the Russian language successfully resisted the influence of a less developed language system. On the other hand, the Norman culture of the lithe, was certainly superior to that of the Saxons. The result was that an immense number of French words forced their way into English vocabulary. Yet, linguistically speaking, this seeming defeat turned into a victory. Instead of being smashed and broken by the powerful intrusion of the foreign element, the English language managed to preserve its essential structure and vastly enriched its expressive resources with the new borrowings.

Sometimes the borrowing process is to fill a gap in vocabulary. When the Saxons borrowed Latin words for butter, plum, beet, they did it because their own vocabularies lacked words for these new objects. For the same reason the words potato and tomato were borrowed by English from Spanish when these vegetables were first brought to England by the Spaniards. But there is also a great number of words which are borrowed for other reasons. There may be a word (or even several words) which expresses some particular concept, so that there is no gap in the vocabulary and there does not seem to be any need for borrowing. Yet, one more word is borrowed which means almost the same, – almost, but not exactly. It is borrowed because it represents the same concept in some new aspect, supplies a new shade of meaning or a different emotional colouring. This type of borrowing enlarges groups of synonyms and greatly provides to enrich the expressive resources of the vocabulary. That is how the Latin cordial was added to the native friendly, the French desire to wish, the Latin admire and the French adore to like and love.

English vocabulary, which is one of the most extensive amongst the world’s languages contains an immense number of words of foreign origin. Explanations for this should be sought in the history of the language which is closely connected with the history of the nation speaking the language. In order to have a better understanding of the problem, it will be necessary to go through a brief survey of certain historical facts, relating to different epochs.

The first century B. C. Most of the territory, known to us as Europe was occupied by the Roman Empire. Among the inhabitants of the continent were Germanic tribes, «barbarians» as the arrogant Romans called them. Theirs was really a rather primitive stage of development, especially if compared with the high civilisation and refinement of Rome. They were primitive cattle-breeders and knew almost nothing about land cultivation. Their tribal languages contained only Indo-European and Germanic elements. After a number of wars between the Germanic tribes and the Romans these two opposing peoples came into peaceful contact. Trade was carried on, and the Germanic people gained knowledge of new and useful things. The first among them were new things to eat. They were to use the Latin words to name them. It was also to the Romans that the Germanic tribes owed the knowledge of some new fruits and vegetables of which they had no idea before, and the Latin names of these fruits and vegetables entered their vocabularies reflecting this new knowledge: cherry (Lat. cerasum), pear (Lat. pirum), plum (Lat. prunus), pea (Lat. pisum), beet (Lat. beta), pepper (Lat. piper). Some more examples of Latin borrowings of this period are: cup (Lat. cuppa), kitchen (Lat. coquina), mill (Lat. molina), port (Lat. portus), wine (Lat. vinum). The fact that all these borrowings occurred is in itself significant. It was certainly important that the Germanic tribal languages gained a considerable number of new words and were thus enriched. What was even more significant was that all these Latin words were destined to become the earliest group of borrowings in the future English language which was – much later – built on the basis of the Germanic tribal languages.

The fifth century A. D. Several of the Germanic tribes (the most numerous amongst them being the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes) migrated across the sea now known as the English Channel to the British Isles. There they were confronted by the Celts, the original inhabitants of the Isles. The Celts desperately defended their lands against the invaders, but they were no match for the military-minded Teutons and gradually yielded most of their territory. They retreated to the North and South-West (moden Scotland, Wales and Cornwall). Through their numerous contacts with the defeated Celts, the conquerors got to know and assimilated a number of Celtic words (Modern English bald, down, glen, druid, bard, cradle). Especially numerous among the Celtic borrowings were place names, names of rivers, bills, etc. The Germanic tribes occupied the land, but the names of many parts and features of their territory remained Celtic. For instance, the names of the rivers Avon, Exe, Esk, Usk, Ux originate from Celtic words meaning «river» and «water». Even the name of the English capital originates from Celtic Llyn + dun in which llyn is another Celtic word for «river» and dun stands for «a fortified hill», the meaning of the whole being «fortress on the hill over the river». Some Latin words entered the Anglo-Saxon languages through Celtic, among them such widely-used words as street (Lat. strata via) and wall (Lat. vallum).

The seventh century A. D. This century was significant for the christianisation of England. Latin was the official language of the Christian church, and consequently the spread of Christianity was accompanied by a new period of Latin borrowings. These no longer came from spoken Latin as they did eight centuries earlier, but from church Latin. Also, these new Latin borrowings were very different in meaning from the earlier ones. They mostly indicated persons, objects and ideas associated with church and religious rituals. E. g. priest (Lai. presbyter), bishop (Lai. episcopus), monk (Lat. monachus), nun (Lai. nonna), candle (Lai. candela). Additionally, in a class of their own were educational terms. It was quite natural that these were also Latin borrowings, for the first schools in England were church schools, and the first teachers priests and monks. So, the word school is a Latin borrowing (Lat. schola, of Greek origin) and so are such words as scholar (Lai. scholar(-is) and magister (Lat. ma-gister).

From the end of the 8th c. to the middle of the lithe. England underwent several Scandinavian invasions which inevitably left their trace on English vocabulary. Here are some examples of early Scandinavian borrowings: call, v., take, v., cast, v., die, v., law, п., husband, n. (hus+bondi, i. e. «inhabitant of the house»), window n. (vindauga, i. e. «the eye of the wind»), loose, adj., low, adj., weak, adj. Some of the words of this group are easily recognisable as Scandinavian borrowings by the initial sk- combination. E.g. sky, skin, ski, skirt. Certain English words changed their meanings under the influence of Scandinavian words of the same root. So, the Оld English bread which meant «piece» acquired its modern meaning by association with the Scandinavian brand. The О. E. dream which meant «joy» assimilated the meaning of the Scandinavian draumr (with the Germ. Traum «dream» and the Russian дрёма).

1066. With the famous Battle of Hastings, when the English were defeated by the Normans under William the Conqueror, we come to the eventful epoch of the Norman Conquest. The epoch can well be called eventful not only in national, social, political and human terms, but also in linguistic terms. England became a bi-lingual country, and the impact on the English vocabulary made over this two-hundred-years period is immense: French words from the Norman dialect penetrated every aspect of social life. Here is a very brief list of examples of Norman French borrowings.

Administrative words: state, government, parliament, council, power.

Legal terms: court, judge, justice, crime, prison.

Military terms: army, war, soldier, officer, battle, enemy.

Educational terms: pupil, lesson, library, science, pen, pencil.

Everyday life was not unaffected by the powerful influence of French words. Numerous terms of everyday life were also borrowed from French in this period: e. g. table, plate, saucer, dinner, supper, river, autumn, uncle, etc.

The Renaissance Period. In England, as in all European countries, this period was marked by significant developments in science, art and culture and, also, by a revival of interest in the ancient civilisations of Greece and Rome and their languages. Hence, they occurred a considerable number of Latin and Greek borrowings. In contrast to the earliest Latin borrowings (1st c. B. C), the Renaissance ones were rarely concrete names. They were mostly abstract words (e. g. major, minor, intelligent, permanent, to elect, to create). There were naturally numerous scientific and artistic terms (datum, status, phenomenon, philosophy, method, music). The same is true of Greek Renaissance borrowings (e. g. atom, cycle, ethics). The Renaissance was a period of extensive cultural contacts between the major European states. Therefore, it was only natural that new words also entered the English vocabulary from other European languages. The most significant once more were French borrowings. This time they came from the Parisian dialect of French and are known as Parisian borrowings: routine, police, machine, ballet, scene, technique etc. Italian also contributed a considerable number of words to English, e. g. piano, violin, opera, alarm, colonel. Latin Loans are classified into the subgroups:

Early Latin Loans. Those are the words which came into English through the language of Anglo-Saxon tribes. The tribes had been in contact with Roman civilization and had adopted several Latin words denoting objects belonging to that civilization long before the invasion of Angles, Saxons and Jutes into Britain (cup, kitchen, wine).

Later Latin Borrowings. To this group belong the words which penetrated the English vocabulary in the sixth and seventh centuries, when the people of England when converted to Christianity (priest, bishop, nun, candle).

The third period of Latin includes words which came into English due to two historical events: the Norman conquest in 1066 and the Renaissance or the Revival of Learning. Some words came into English through French but some were taken directly from Latin (major, minor, intelligent, permanent).

The Latest Stratum of Latin Words. The words of this period are mainly abstract and scientific words (nylon, molecular, phenomenon, vacuum).

Norman-French Borrowings may be subdivided into subgroups:

Early loans – 12th – 15th century.

Later loans – beginning from the 16th century.

T

he Early French borrowings are simple short words, naturalized in accordance with the English language system (state, power, war, pen, river). Later French borrowings can

be identified by their peculiarities of form and pronunciation (police, ballet, scene) (table 1). There are certain structural features which enable us to identify some words as borrowings and even to determine the source language.

Lexical correlations are defined as lexical units from different languages which are phonetically and semantically related. The number of Ukrainian-English lexical correlations is about 6870. The history of the Slavonic-German ties resulted in the following correlations: beat – бити, widow – вдова, call – голос, young – юний, day – день etc. Some Ukrainian-English lexical correlations have common Indo-European back-ground: garden – город, murder – мордувати, soot – сажа. Beside Ukrainian – English lexical correlations the Ukrainian language contains borrowings from modern English period: брифінг – briefing; хіт парад – hit parade; диск – жокей – disk – jockey; кітч, халтура – kitch; ескапізм – escapism; масс-медія – mass media; естеблішмент – establishment; серіал – serial.

INTERNATIONAL WORDS

Expanding global contacts result in the considerable growth of international vocabulary. All languages depend for their changes upon the cultural and social matrix in which they operate and various contacts between nations are part of this matrix reflected in vocabulary. International words play an especially prominent part in various terminological systems including the vocabulary of science, industry and art. The etymological sources of this vocabulary reflect the history of world culture. Thus, for example, the mankind’s cultural debt to Italy is reflected in the great number of Italian words connected with architecture, painting and especially music that are borrowed into most European languages: allegro, aria, barcarole, baritone (and other names for voices), concert, opera (and other names for pieces of music), piano and many more. The rate of change in technology, political, social and artistic life has been greatly accelerated in the 20th century and so has the rate of growth of international word stock. A few examples of comparatively new words due to the progress of science will suffice to illustrate the importance of international vocabulary: algorithm, antenna, antibiotic, cybernetics, gene, genetic code, microelectronics, etc. All these show sufficient likeness in English, French, Russian and several other languages. The international word stock is also growing due to the influx of exotic borrowed words like anaconda, bungalow, kraal etc. These come from many different sources. International words should not be mixed with words of the common Indo-European stock that also comprise a sort of common fund of the European languages. This layer is of great importance for the foreign language teacher not only because many words denoting abstract notions are international but also because he must know the most efficient ways of showing the points of similarity and difference between such words as control – контроль; general – генерал; industry – индустрия or magazine – магазин, etc. usually called ‘translator’s false friends’. The treatment of international words at English lessons would be one-sided if the teacher did not draw his pupils’ attention to the spread of the English vocabulary into other languages. We find numerous English words in the field of sport: football, match, tennis, time. A large number of English words are to be found in the vocabulary pertaining to clothes: sweater, nylon, tweed, etc. Cinema and different forms of entertainment are also a source of many international words of English origin: film, club, jazz. At least some of the Russian words borrowed into English and many other languages and thus international should also be mentioned: balalaika, czar, Kremlin, soviet, sputnik, vodka. To sum up this brief treatment of loan words it is necessary to stress that in studying loan words a linguist cannot be content with establishing the source, the date of penetration, the semantic sphere to which the word belonged and the circumstances of the process of borrowing. All these are very important, but one should also be concerned with the changes the new language system into which the loan word penetrates causes in the word itself, and, on the other hand, look for the changes occasioned by the newcomer in the English vocabulary, when in finding its way into the new language it pushed some of its lexical neighbours aside. In the discussion above we have tried to show the importance of the problem of conformity with the patterns typical of the receiving language and its semantic needs.

So, international words are defined as “words of identical origin that occur in several languages as a result of simultaneous or successive borrowings from one ultimate source” (I. V. Arnold). International words reflect the history of word culture, they convey notions which are significant in communication. New inventions, political institutions, leisure activities, science, technological advances have all generated new lexemes and continue to do so: sputnik, television, antenna, gene, cybernetics, bungalow, anaconda, coffee, chocolate, grapefruit, etc. The English language contributed a considerable number of international words to world languages, e.g. the sports terms: football, baseball, cricket, golf. International words are mainly borrowings.

12