Word order is very important in English, because the language is no longer inflected. That is, individual words do not have endings to show which parts of speech they represent. Nevertheless this word order is not invariable. It is well-known that English is a language that strictly follows the syntax rules, in spite of this, exceptions do frequently occur.

Although English exhibits a relatively fixed word order in comparison to many other languages, the English word order is not as rigid as it is held: in many cases, speakers can choose between different constituent orderings or constructional alternations as exemplified in the following sentence pairs: John gave the book to Fred vs. John gave Fred the book, Which newspapers do we maintain strict editorial control over? vs. Over which newspapers do we maintain strict editorial control?, John picked up the book vs. John picked the book up, the President’s speech vs. the speech of the President.

So as it was already mentioned English stylistics allows a sort of flexibility in arranging words in a sentence, as a rule it is mostly common for literary works, both prose and poetry. The reason for this is that changes to conventional syntax are often used to create dramatic, poetic, or comic effect.

For instance, poets and song lyricists often change syntactic order to create rhythmic effects:

E.g. «I’ll sing to him, each spring to him

And long for the day when I’ll cling to him,

Bewitched, bothered and bewildered am I.»

According to Keenan ’s opinion the word order is prominent for its semantic and pragmatic roles. A standard view of the relationship between semantics and pragmatics would be something like the following: Semantics is primarily concerned with meanings that are relatively stable out of context, and analyzable in terms of the logical conditions under which they would be true. Pragmatics, by contrast is related both to the message’s indirect meaning beyond what is written, and to the reader’s interpretation, deriving from the context.

Finally, semantic roles are simpler than pragmatic ones. Semantic relations represent consistent common recognition of the objective world by the whole language community, while pragmatic role involves individual writers’ subjective, contingent knowledge, assumption, attitude, etc. Semantic relations can be seen as the essential, notional part of word order units, whereas pragmatic roles are not part of units, they are the packaging or the way of using units.

The semantically optimal order is homogeneous from the general point of view; while the criteria for ‘basic order’ are diverse in the literature. The reason for this is the fact that literature is a noble art that changes neck-to-neck with its basic instrument – the language which is constantly developing. The literary style has a tendency to be diversified; the writers’ aim is to achieve some elevated effect on the reader that is why they do not follow strict syntax rules. In this manner they make their works unique, vivid and outstanding.

Generally speaking, the role of word order is to transmit the message so as it could be easily perceived by the reader.

What concerns the word order in different writing styles, its primary role is to emphasize some particular message carried by the sentence and to produce a colorful and deep effect on the reader.

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 268 человек из 64 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Word Meaning

Lecture # 6

Grigoryeva M. -

2 слайд

Word Meaning

Approaches to word meaning

Meaning and Notion (понятие)

Types of word meaning

Types of morpheme meaning

Motivation

-

3 слайд

Each word has two aspects:

the outer aspect

( its sound form)

catthe inner aspect

(its meaning)

long-legged, fury animal with sharp teeth

and claws -

4 слайд

Sound and meaning do not always constitute a constant unit even in the same language

EX a temple

a part of a human head

a large church -

5 слайд

Semantics (Semasiology)

Is a branch of lexicology which studies the

meaning of words and word equivalents -

6 слайд

Approaches to Word Meaning

The Referential (analytical) approachThe Functional (contextual) approach

Operational (information-oriented) approach

-

7 слайд

The Referential (analytical) approach

formulates the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words and things or concepts they denotedistinguishes between three components closely connected with meaning:

the sound-form of the linguistic sign,

the concept

the actual referent -

8 слайд

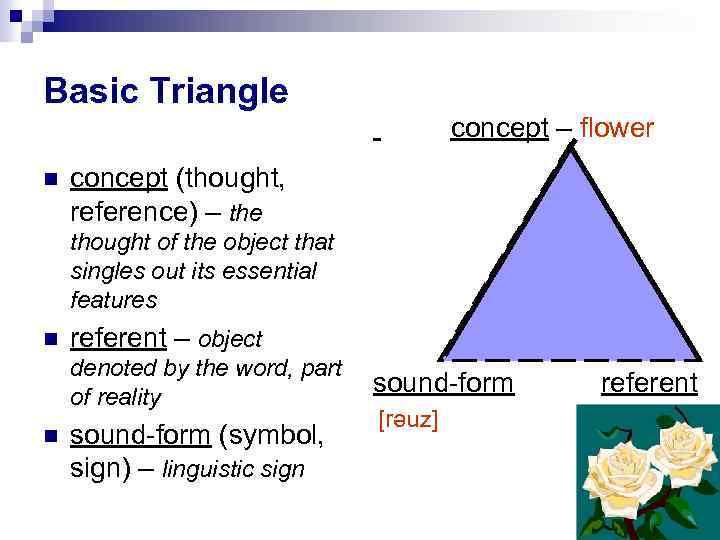

Basic Triangle

concept (thought, reference) – the thought of the object that singles out its essential features

referent – object denoted by the word, part of reality

sound-form (symbol, sign) – linguistic sign

concept – flowersound-form referent

[rәuz] -

9 слайд

In what way does meaning correlate with

each element of the triangle ?In what relation does meaning stand to

each of them? -

10 слайд

Meaning and Sound-form

are not identical

different

EX. dove — [dΛv] English sound-forms

[golub’] Russian BUT

[taube] German

the same meaning -

11 слайд

Meaning and Sound-form

nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages

EX. [kot] Russian – a male cat

[kot] English – a small bed for a childidentical sound-forms have different meanings (‘homonyms)

EX. knight [nait]

night [nait] -

12 слайд

Meaning and Sound-form

even considerable changes in sound-form do not affect the meaningEX Old English lufian [luvian] – love [l Λ v]

-

13 слайд

Meaning and Concept

concept is a category of human cognitionconcept is abstract and reflects the most common and typical features of different objects and phenomena in the world

meanings of words are different in different languages

-

14 слайд

Meaning and Concept

identical concepts may have different semantic structures in different languagesEX. concept “a building for human habitation” –

English Russian

HOUSE ДОМ+ in Russian ДОМ

“fixed residence of family or household”

In English HOME -

15 слайд

Meaning and Referent

one and the same object (referent) may be denoted by more than one word of a different meaning

cat

pussy

animal

tiger -

16 слайд

Meaning

is not identical with any of the three points of the triangle –

the sound form,

the concept

the referentBUT

is closely connected with them. -

17 слайд

Functional Approach

studies the functions of a word in speech

meaning of a word is studied through relations of it with other linguistic units

EX. to move (we move, move a chair)

movement (movement of smth, slow movement)The distriution ( the position of the word in relation to

others) of the verb to move and a noun movement is

different as they belong to different classes of words and

their meanings are different -

18 слайд

Operational approach

is centered on defining meaning through its role in

the process of communicationEX John came at 6

Beside the direct meaning the sentence may imply that:

He was late

He failed to keep his promise

He was punctual as usual

He came but he didn’t want toThe implication depends on the concrete situation

-

19 слайд

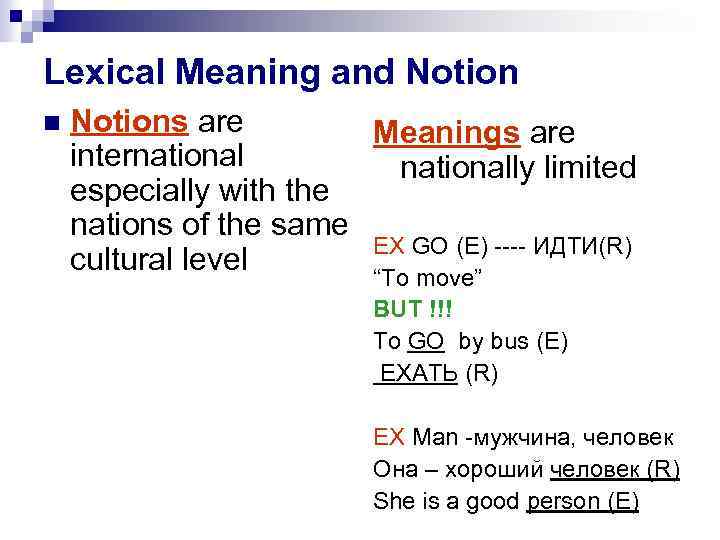

Lexical Meaning and Notion

Notion denotes the reflection in the mind of real objectsNotion is a unit of thinking

Lexical meaning is the realization of a notion by means of a definite language system

Word is a language unit -

20 слайд

Lexical Meaning and Notion

Notions are international especially with the nations of the same cultural levelMeanings are nationally limited

EX GO (E) —- ИДТИ(R)

“To move”

BUT !!!

To GO by bus (E)

ЕХАТЬ (R)EX Man -мужчина, человек

Она – хороший человек (R)

She is a good person (E) -

21 слайд

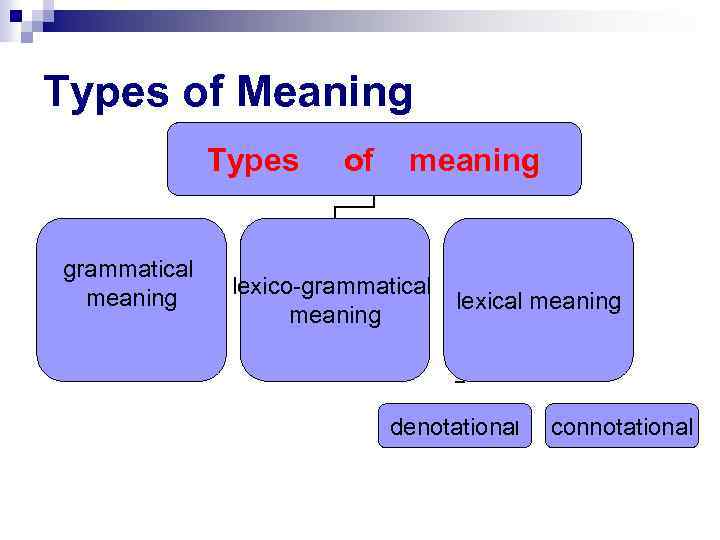

Types of Meaning

Types of meaninggrammatical

meaninglexico-grammatical

meaning

lexical meaning

denotational

connotational -

22 слайд

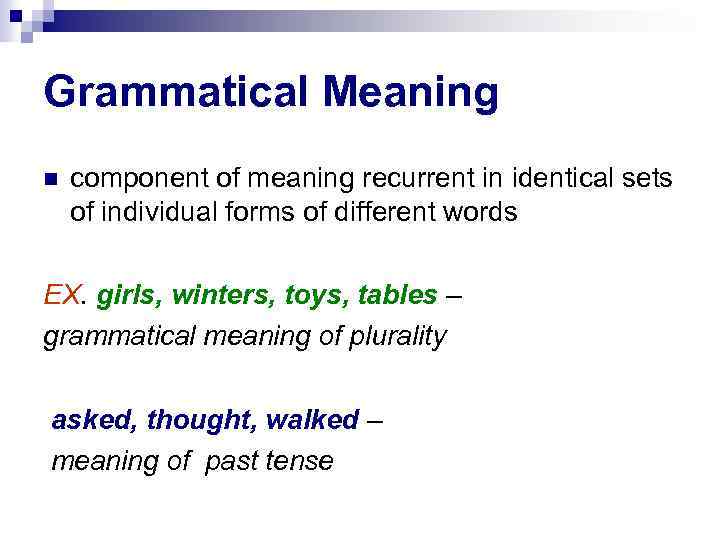

Grammatical Meaning

component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different wordsEX. girls, winters, toys, tables –

grammatical meaning of pluralityasked, thought, walked –

meaning of past tense -

23 слайд

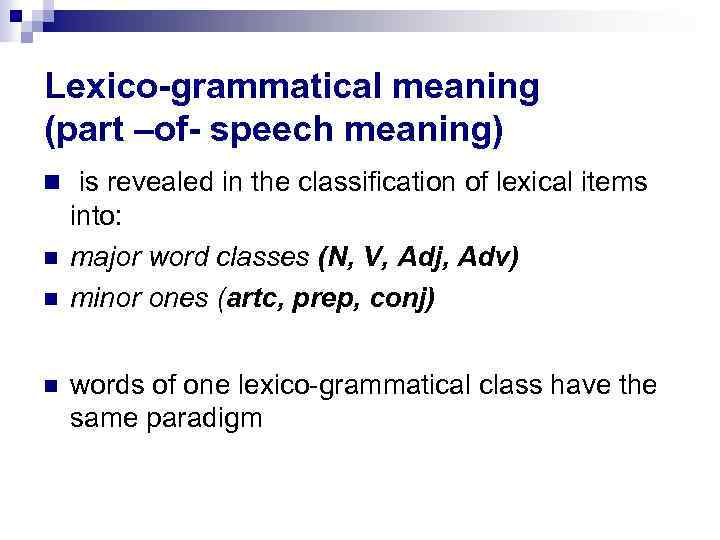

Lexico-grammatical meaning

(part –of- speech meaning)

is revealed in the classification of lexical items into:

major word classes (N, V, Adj, Adv)

minor ones (artc, prep, conj)words of one lexico-grammatical class have the same paradigm

-

24 слайд

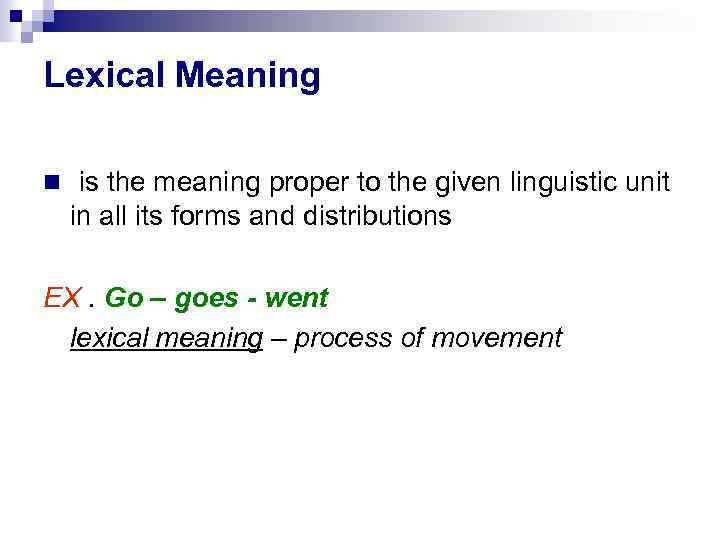

Lexical Meaning

is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributionsEX . Go – goes — went

lexical meaning – process of movement -

25 слайд

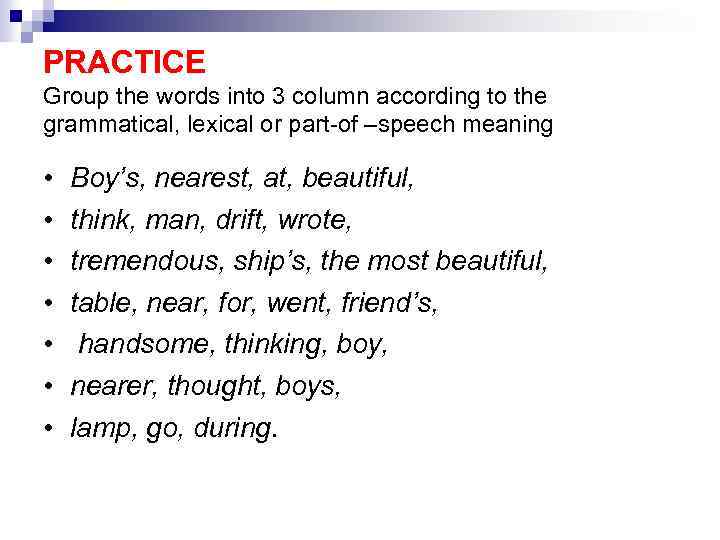

PRACTICE

Group the words into 3 column according to the grammatical, lexical or part-of –speech meaning

Boy’s, nearest, at, beautiful,

think, man, drift, wrote,

tremendous, ship’s, the most beautiful,

table, near, for, went, friend’s,

handsome, thinking, boy,

nearer, thought, boys,

lamp, go, during. -

26 слайд

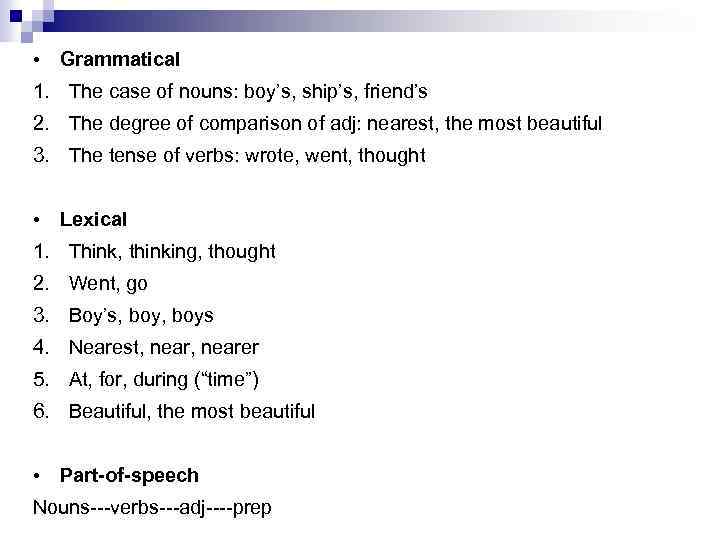

Grammatical

The case of nouns: boy’s, ship’s, friend’s

The degree of comparison of adj: nearest, the most beautiful

The tense of verbs: wrote, went, thoughtLexical

Think, thinking, thought

Went, go

Boy’s, boy, boys

Nearest, near, nearer

At, for, during (“time”)

Beautiful, the most beautifulPart-of-speech

Nouns—verbs—adj—-prep -

27 слайд

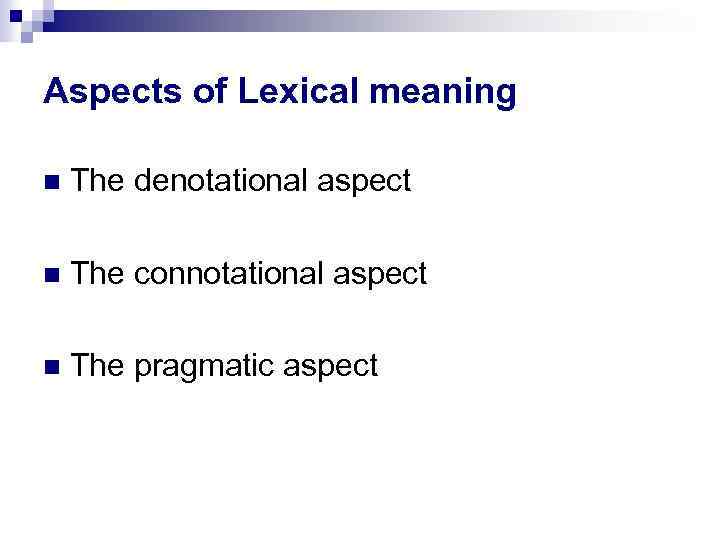

Aspects of Lexical meaning

The denotational aspectThe connotational aspect

The pragmatic aspect

-

28 слайд

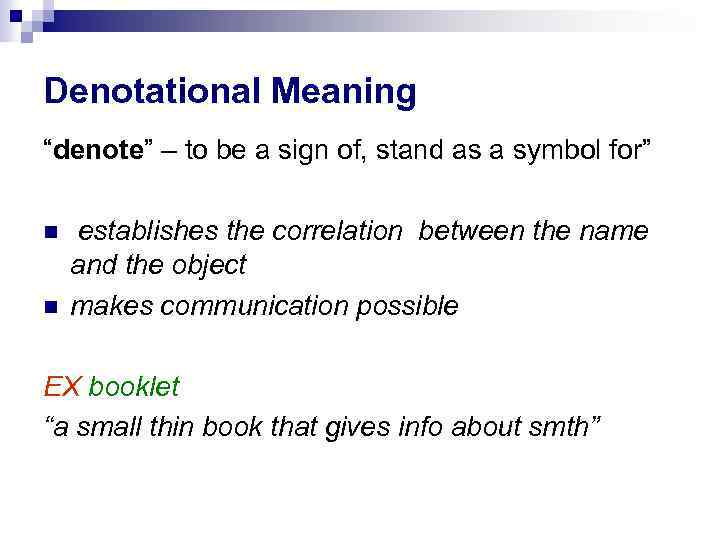

Denotational Meaning

“denote” – to be a sign of, stand as a symbol for”establishes the correlation between the name and the object

makes communication possibleEX booklet

“a small thin book that gives info about smth” -

29 слайд

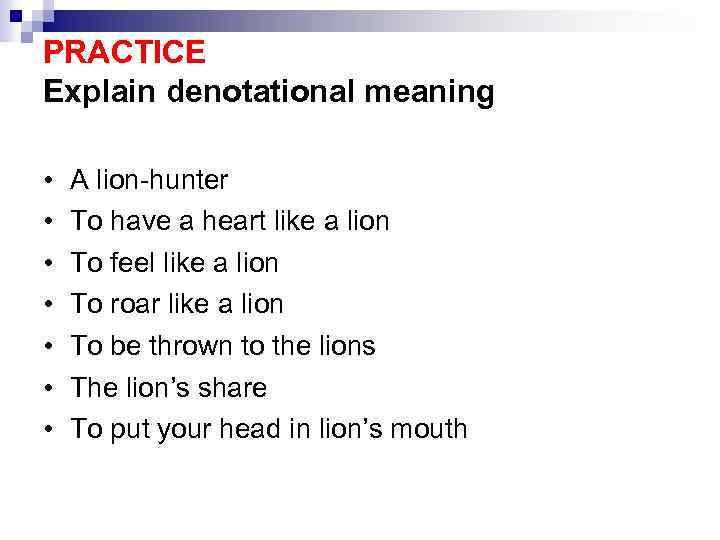

PRACTICE

Explain denotational meaningA lion-hunter

To have a heart like a lion

To feel like a lion

To roar like a lion

To be thrown to the lions

The lion’s share

To put your head in lion’s mouth -

30 слайд

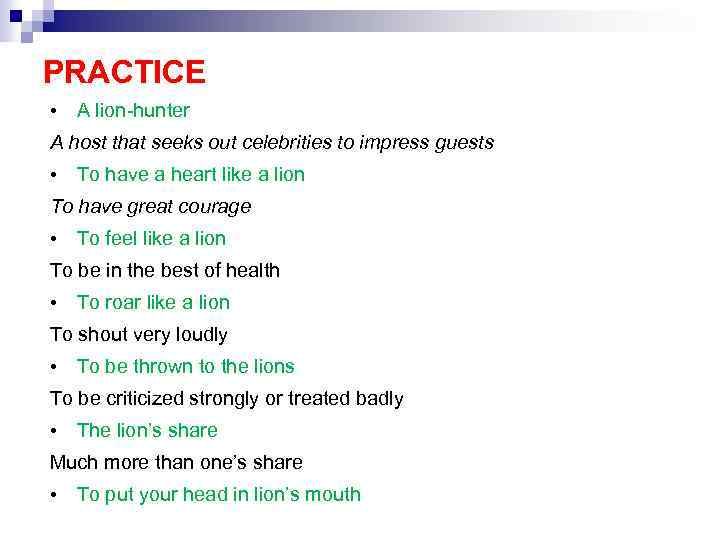

PRACTICE

A lion-hunter

A host that seeks out celebrities to impress guests

To have a heart like a lion

To have great courage

To feel like a lion

To be in the best of health

To roar like a lion

To shout very loudly

To be thrown to the lions

To be criticized strongly or treated badly

The lion’s share

Much more than one’s share

To put your head in lion’s mouth -

31 слайд

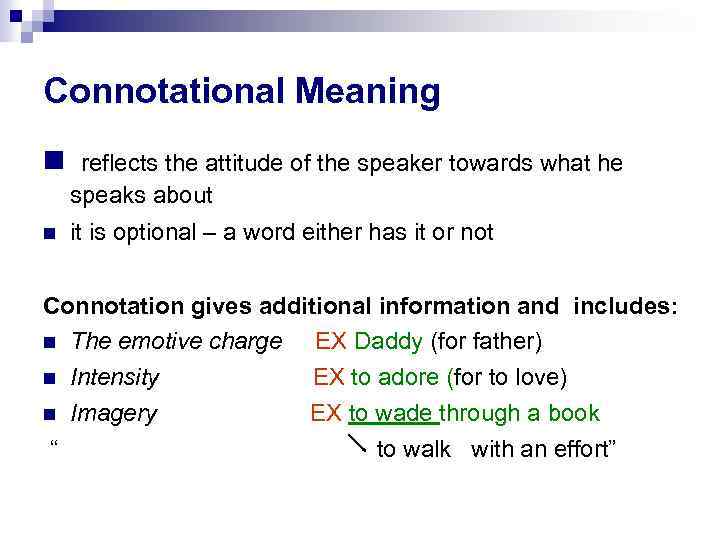

Connotational Meaning

reflects the attitude of the speaker towards what he speaks about

it is optional – a word either has it or notConnotation gives additional information and includes:

The emotive charge EX Daddy (for father)

Intensity EX to adore (for to love)

Imagery EX to wade through a book

“ to walk with an effort” -

32 слайд

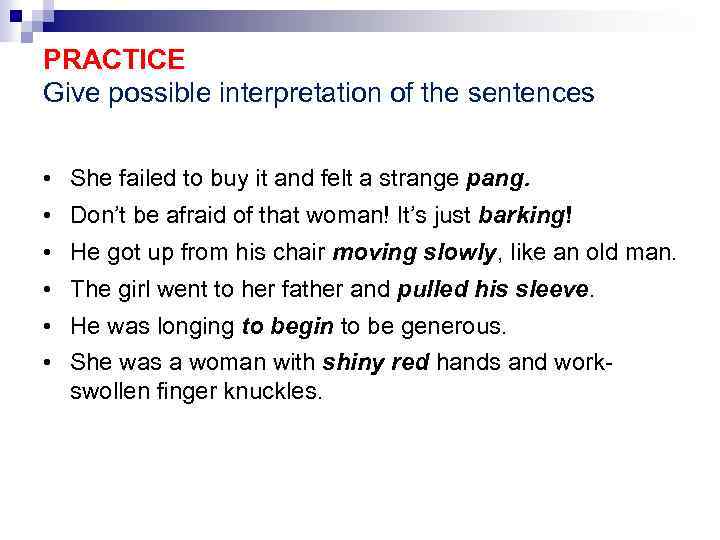

PRACTICE

Give possible interpretation of the sentencesShe failed to buy it and felt a strange pang.

Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking!

He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man.

The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve.

He was longing to begin to be generous.

She was a woman with shiny red hands and work-swollen finger knuckles. -

33 слайд

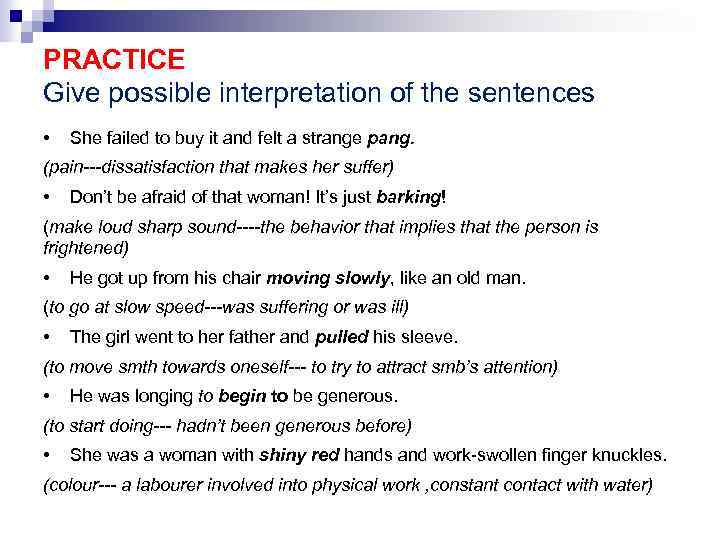

PRACTICE

Give possible interpretation of the sentences

She failed to buy it and felt a strange pang.

(pain—dissatisfaction that makes her suffer)

Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking!

(make loud sharp sound—-the behavior that implies that the person is frightened)

He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man.

(to go at slow speed—was suffering or was ill)

The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve.

(to move smth towards oneself— to try to attract smb’s attention)

He was longing to begin to be generous.

(to start doing— hadn’t been generous before)

She was a woman with shiny red hands and work-swollen finger knuckles.

(colour— a labourer involved into physical work ,constant contact with water) -

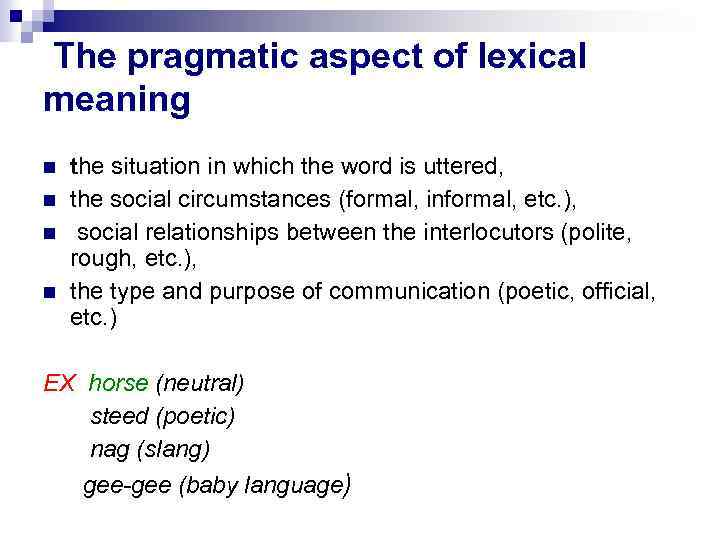

34 слайд

The pragmatic aspect of lexical meaning

the situation in which the word is uttered,

the social circumstances (formal, informal, etc.),

social relationships between the interlocutors (polite, rough, etc.),

the type and purpose of communication (poetic, official, etc.)EX horse (neutral)

steed (poetic)

nag (slang)

gee-gee (baby language) -

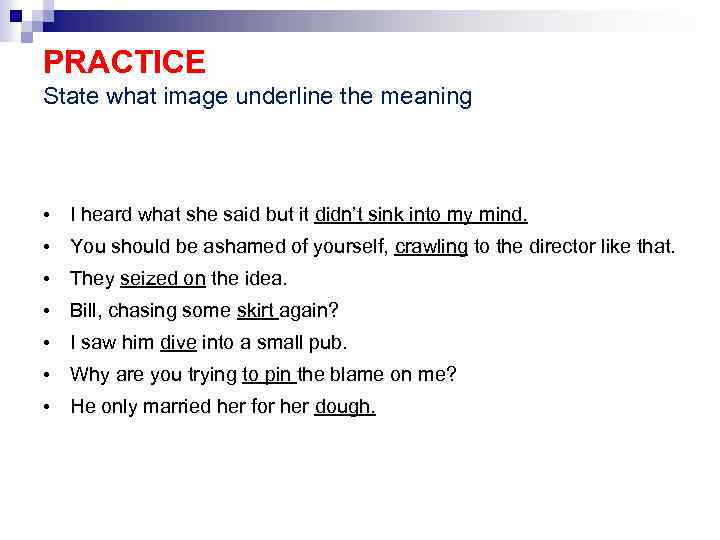

35 слайд

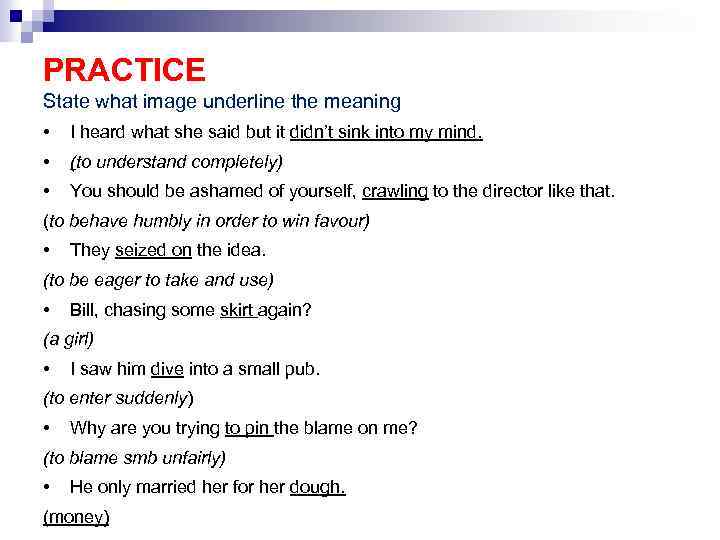

PRACTICE

State what image underline the meaningI heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind.

You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that.

They seized on the idea.

Bill, chasing some skirt again?

I saw him dive into a small pub.

Why are you trying to pin the blame on me?

He only married her for her dough. -

36 слайд

PRACTICE

State what image underline the meaning

I heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind.

(to understand completely)

You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that.

(to behave humbly in order to win favour)

They seized on the idea.

(to be eager to take and use)

Bill, chasing some skirt again?

(a girl)

I saw him dive into a small pub.

(to enter suddenly)

Why are you trying to pin the blame on me?

(to blame smb unfairly)

He only married her for her dough.

(money) -

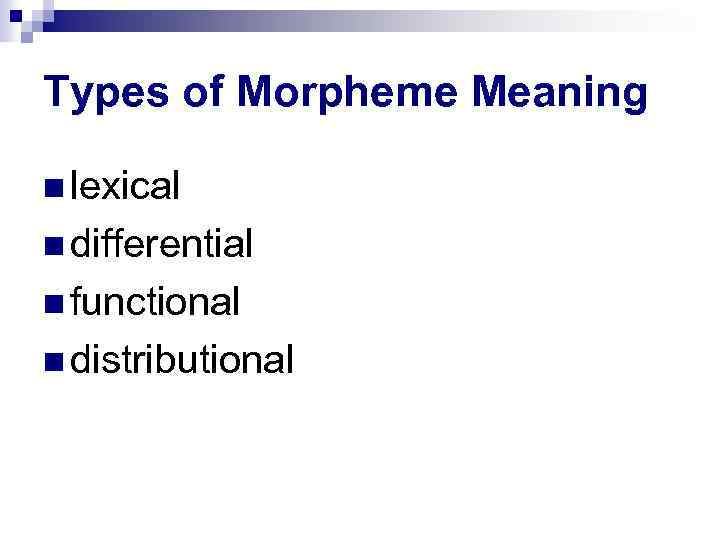

37 слайд

Types of Morpheme Meaning

lexical

differential

functional

distributional -

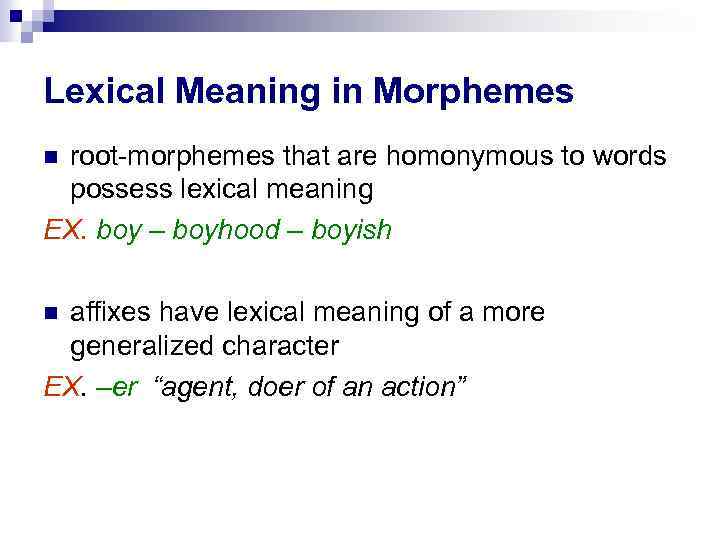

38 слайд

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes

root-morphemes that are homonymous to words possess lexical meaning

EX. boy – boyhood – boyishaffixes have lexical meaning of a more generalized character

EX. –er “agent, doer of an action” -

39 слайд

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes

has denotational and connotational components

EX. –ly, -like, -ish –

denotational meaning of similiarity

womanly , womanishconnotational component –

-ly (positive evaluation), -ish (deragotary) женственный — женоподобный -

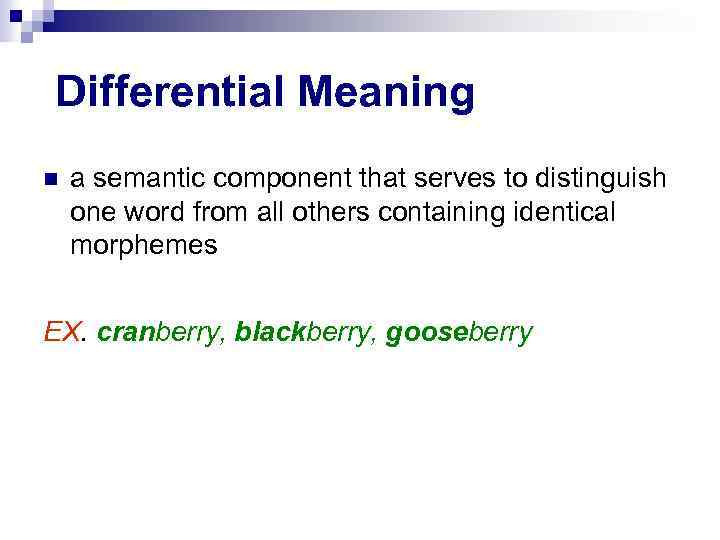

40 слайд

Differential Meaning

a semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemesEX. cranberry, blackberry, gooseberry

-

41 слайд

Functional Meaning

found only in derivational affixes

a semantic component which serves to

refer the word to the certain part of speechEX. just, adj. – justice, n.

-

42 слайд

Distributional Meaning

the meaning of the order and the arrangement of morphemes making up the word

found in words containing more than one morpheme

different arrangement of the same morphemes would make the word meaningless

EX. sing- + -er =singer,

-er + sing- = ? -

43 слайд

Motivation

denotes the relationship between the phonetic or morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word on the one hand, and its meaning on the othercan be phonetical

morphological

semantic -

44 слайд

Phonetical Motivation

when there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the word and those produced by animals, objects, etc.EX. sizzle, boom, splash, cuckoo

-

45 слайд

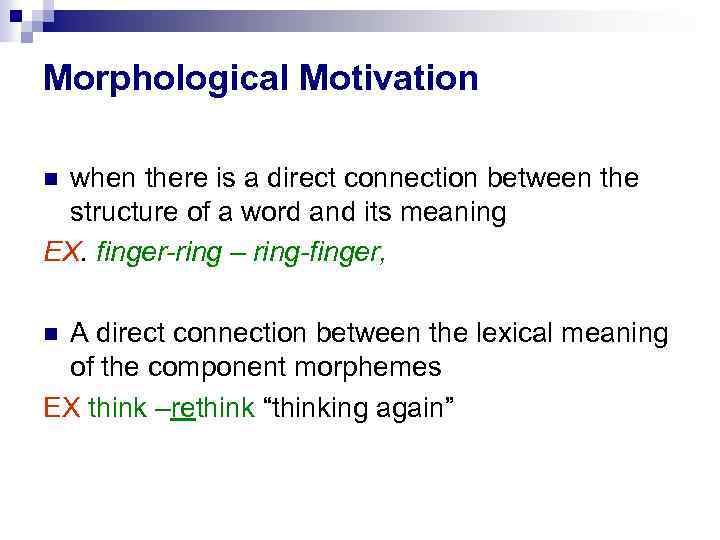

Morphological Motivation

when there is a direct connection between the structure of a word and its meaning

EX. finger-ring – ring-finger,A direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component morphemes

EX think –rethink “thinking again” -

46 слайд

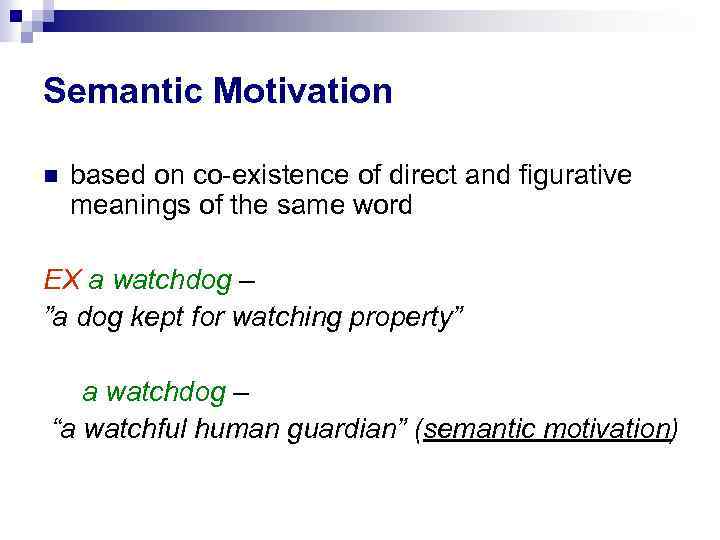

Semantic Motivation

based on co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same wordEX a watchdog –

”a dog kept for watching property”a watchdog –

“a watchful human guardian” (semantic motivation) -

-

48 слайд

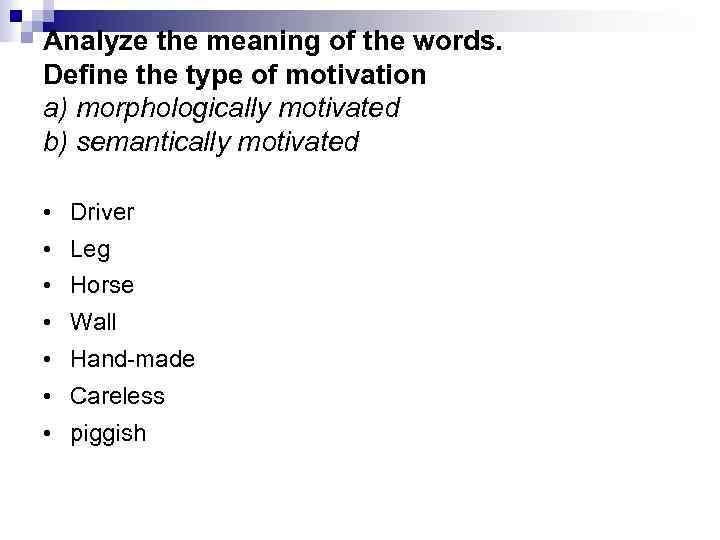

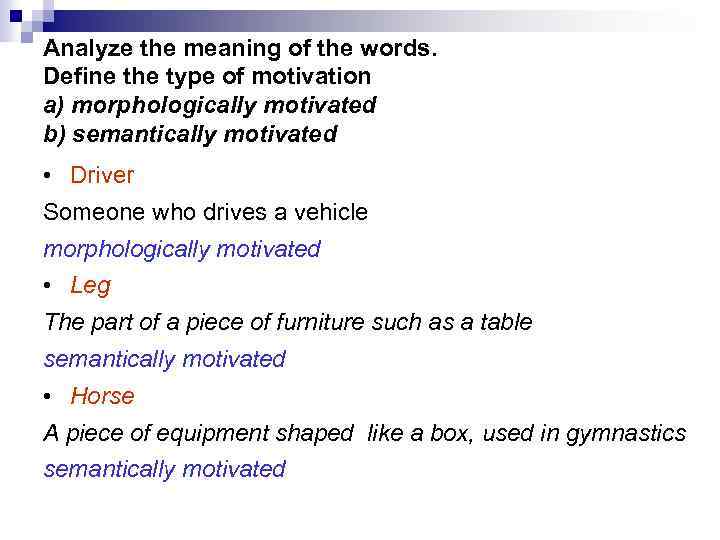

Analyze the meaning of the words.

Define the type of motivation

a) morphologically motivated

b) semantically motivatedDriver

Leg

Horse

Wall

Hand-made

Careless

piggish -

49 слайд

Analyze the meaning of the words.

Define the type of motivation

a) morphologically motivated

b) semantically motivated

Driver

Someone who drives a vehicle

morphologically motivated

Leg

The part of a piece of furniture such as a table

semantically motivated

Horse

A piece of equipment shaped like a box, used in gymnastics

semantically motivated -

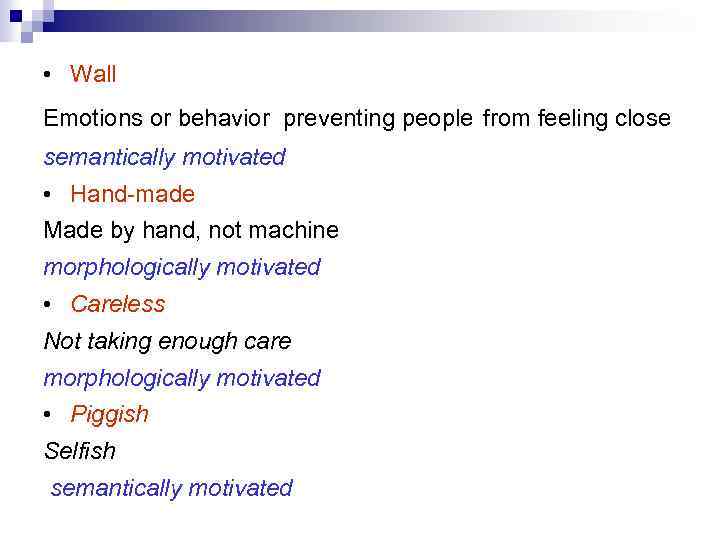

50 слайд

Wall

Emotions or behavior preventing people from feeling close

semantically motivated

Hand-made

Made by hand, not machine

morphologically motivated

Careless

Not taking enough care

morphologically motivated

Piggish

Selfish

semantically motivated -

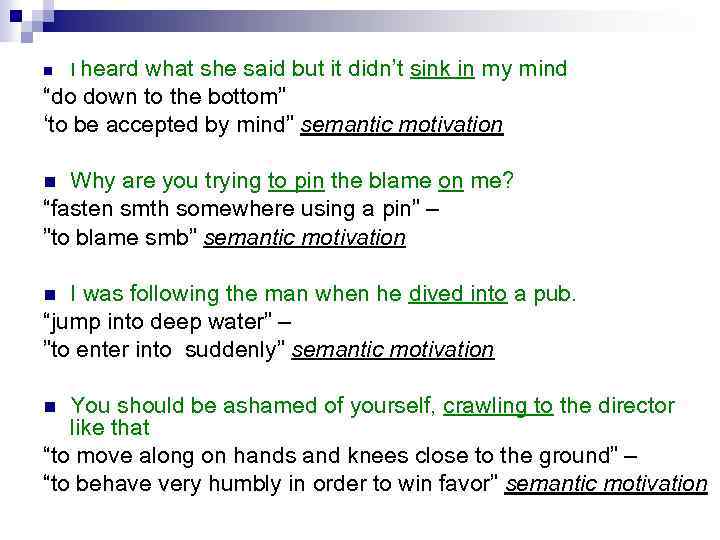

51 слайд

I heard what she said but it didn’t sink in my mind

“do down to the bottom”

‘to be accepted by mind” semantic motivationWhy are you trying to pin the blame on me?

“fasten smth somewhere using a pin” –

”to blame smb” semantic motivationI was following the man when he dived into a pub.

“jump into deep water” –

”to enter into suddenly” semantic motivationYou should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that

“to move along on hands and knees close to the ground” –

“to behave very humbly in order to win favor” semantic motivation

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 210 150 материалов в базе

-

Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 22.10.2020

- 141

- 0

- 21.09.2020

- 530

- 1

- 18.09.2020

- 256

- 0

- 11.09.2020

- 191

- 1

- 21.08.2020

- 197

- 0

- 18.08.2020

- 123

- 0

- 03.07.2020

- 94

- 0

- 06.06.2020

- 73

- 0

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Формирование компетенций межкультурной коммуникации в условиях реализации ФГОС»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Клиническая психология: теория и методика преподавания в образовательной организации»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Введение в сетевые технологии»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «История и философия науки в условиях реализации ФГОС ВО»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Основы построения коммуникаций в организации»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация практики студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС медицинских направлений подготовки»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Правовое регулирование рекламной и PR-деятельности»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация маркетинга в туризме»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Источники финансов»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Техническая диагностика и контроль технического состояния автотранспортных средств»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Осуществление и координация продаж»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Технический контроль и техническая подготовка сварочного процесса»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Управление качеством»

Word Meaning Lecture # 6 Grigoryeva M.

Word Meaning Approaches to word meaning Meaning and Notion (понятие) Types of word meaning Types of morpheme meaning Motivation

Each word has two aspects: the outer aspect ( its sound form) cat the inner aspect (its meaning) long-legged, fury animal with sharp teeth and claws

Sound and meaning do not always constitute a constant unit even in the same language EX a temple a part of a human head a large church

Semantics (Semasiology) Is a branch of lexicology which studies the meaning of words and word equivalents

Approaches to Word Meaning The Referential (analytical) approach The Functional (contextual) approach Operational (information-oriented) approach

The Referential (analytical) approach formulates the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words and things or concepts they denote distinguishes between three components closely connected with meaning: the sound-form of the linguistic sign, the concept the actual referent

Basic Triangle concept – flower concept (thought, reference) – the thought of the object that singles out its essential features referent – object denoted by the word, part of reality sound-form (symbol, sign) – linguistic sign sound-form [rәuz] referent

In what way does meaning correlate with each element of the triangle ? • In what relation does meaning stand to each of them? •

Meaning and Sound-form are not identical different EX. dove — [dΛv] English [golub’] Russian [taube] German sound-forms BUT the same meaning

Meaning and Sound-form nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages EX. [kot] Russian – a male cat [kot] English – a small bed for a child identical sound-forms have different meanings (‘homonyms) EX. knight [nait]

Meaning and Sound-form even considerable changes in sound-form do not affect the meaning EX Old English lufian [luvian] – love [l Λ v]

Meaning and Concept concept is a category of human cognition concept is abstract and reflects the most common and typical features of different objects and phenomena in the world meanings of words are different in different languages

Meaning and Concept identical concepts may have different semantic structures in different languages EX. concept “a building for human habitation” – English Russian HOUSE ДОМ + in Russian ДОМ “fixed residence of family or household” In English HOME

Meaning and Referent one and the same object (referent) may be denoted by more than one word of a different meaning cat pussy animal tiger

Meaning is not identical with any of the three points of the triangle – the sound form, the concept the referent BUT is closely connected with them.

Functional Approach studies the functions of a word in speech meaning of a word is studied through relations of it with other linguistic units EX. to move (we move, move a chair) movement (movement of smth, slow movement) The distriution ( the position of the word in relation to others) of the verb to move and a noun movement is different as they belong to different classes of words and their meanings are different

Operational approach is centered on defining meaning through its role in the process of communication EX John came at 6 Beside the direct meaning the sentence may imply that: He was late He failed to keep his promise He was punctual as usual He came but he didn’t want to The implication depends on the concrete situation

Lexical Meaning and Notion denotes the Lexical meaning is reflection in the realization of a mind of real objects notion by means of a definite language system Notion is a unit of Word is a language thinking unit

Lexical Meaning and Notions are Meanings are internationally limited especially with the nations of the same EX GO (E) —- ИДТИ(R) cultural level “To move” BUT !!! To GO by bus (E) ЕХАТЬ (R) EX Man -мужчина, человек Она – хороший человек (R) She is a good person (E)

Types of Meaning Types grammatical meaning of meaning lexico-grammatical meaning lexical meaning denotational connotational

Grammatical Meaning component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words EX. girls, winters, toys, tables – grammatical meaning of plurality asked, thought, walked – meaning of past tense

Lexico-grammatical meaning (part –of- speech meaning) is revealed in the classification of lexical items into: major word classes (N, V, Adj, Adv) minor ones (artc, prep, conj) words of one lexico-grammatical class have the same paradigm

Lexical Meaning is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions EX. Go – goes — went lexical meaning – process of movement

PRACTICE Group the words into 3 column according to the grammatical, lexical or part-of –speech meaning • • Boy’s, nearest, at, beautiful, think, man, drift, wrote, tremendous, ship’s, the most beautiful, table, near, for, went, friend’s, handsome, thinking, boy, nearer, thought, boys, lamp, go, during.

• Grammatical 1. The case of nouns: boy’s, ship’s, friend’s 2. The degree of comparison of adj: nearest, the most beautiful 3. The tense of verbs: wrote, went, thought • Lexical 1. Think, thinking, thought 2. Went, go 3. Boy’s, boys 4. Nearest, nearer 5. At, for, during (“time”) 6. Beautiful, the most beautiful • Part-of-speech Nouns—verbs—adj—-prep

Aspects of Lexical meaning The denotational aspect The connotational aspect The pragmatic aspect

Denotational Meaning “denote” – to be a sign of, stand as a symbol for” establishes the correlation between the name and the object makes communication possible EX booklet “a small thin book that gives info about smth”

PRACTICE Explain denotational meaning • • A lion-hunter To have a heart like a lion To feel like a lion To roar like a lion To be thrown to the lions The lion’s share To put your head in lion’s mouth

PRACTICE • A lion-hunter A host that seeks out celebrities to impress guests • To have a heart like a lion To have great courage • To feel like a lion To be in the best of health • To roar like a lion To shout very loudly • To be thrown to the lions To be criticized strongly or treated badly • The lion’s share Much more than one’s share • To put your head in lion’s mouth

Connotational Meaning reflects the attitude of the speaker towards what he speaks about it is optional – a word either has it or not Connotation gives additional information and includes: The emotive charge EX Daddy (for father) Intensity EX to adore (for to love) Imagery EX to wade through a book “ to walk with an effort”

PRACTICE Give possible interpretation of the sentences • She failed to buy it and felt a strange pang. • Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking! • He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man. • The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve. • He was longing to begin to be generous. • She was a woman with shiny red hands and workswollen finger knuckles.

PRACTICE Give possible interpretation of the sentences • She failed to buy it and felt a strange pang. (pain—dissatisfaction that makes her suffer) • Don’t be afraid of that woman! It’s just barking! (make loud sharp sound—-the behavior that implies that the person is frightened) • He got up from his chair moving slowly, like an old man. (to go at slow speed—was suffering or was ill) • The girl went to her father and pulled his sleeve. (to move smth towards oneself— to try to attract smb’s attention) • He was longing to begin to be generous. (to start doing— hadn’t been generous before) • She was a woman with shiny red hands and work-swollen finger knuckles. (colour— a labourer involved into physical work , constant contact with water)

The pragmatic aspect of lexical meaning the situation in which the word is uttered, the social circumstances (formal, informal, etc. ), social relationships between the interlocutors (polite, rough, etc. ), the type and purpose of communication (poetic, official, etc. ) EX horse (neutral) steed (poetic) nag (slang) gee-gee (baby language)

PRACTICE State what image underline the meaning • I heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind. • You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that. • They seized on the idea. • Bill, chasing some skirt again? • I saw him dive into a small pub. • Why are you trying to pin the blame on me? • He only married her for her dough.

PRACTICE State what image underline the meaning • I heard what she said but it didn’t sink into my mind. • (to understand completely) • You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that. (to behave humbly in order to win favour) • They seized on the idea. (to be eager to take and use) • Bill, chasing some skirt again? (a girl) • I saw him dive into a small pub. (to enter suddenly) • Why are you trying to pin the blame on me? (to blame smb unfairly) • He only married her for her dough. (money)

Types of Morpheme Meaning lexical differential functional distributional

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes root-morphemes that are homonymous to words possess lexical meaning EX. boy – boyhood – boyish affixes have lexical meaning of a more generalized character EX. –er “agent, doer of an action”

Lexical Meaning in Morphemes has denotational and connotational components EX. –ly, -like, -ish – denotational meaning of similiarity womanly , womanish connotational component – -ly (positive evaluation), -ish (deragotary) женственный женоподобный

Differential Meaning a semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes EX. cranberry, blackberry, gooseberry

Functional Meaning found only in derivational affixes a semantic component which serves to refer the word to the certain part of speech EX. just, adj. – justice, n.

Distributional Meaning the meaning of the order and the arrangement of morphemes making up the word found in words containing more than one morpheme different arrangement of the same morphemes would make the word meaningless EX. sing- + -er =singer, -er + sing- = ?

Motivation denotes the relationship between the phonetic or morphemic composition and structural pattern of the word on the one hand, and its meaning on the other can be phonetical morphological semantic

Phonetical Motivation when there is a certain similarity between the sounds that make up the word and those produced by animals, objects, etc. EX. sizzle, boom, splash, cuckoo

Morphological Motivation when there is a direct connection between the structure of a word and its meaning EX. finger-ring – ring-finger, A direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component morphemes EX think –rethink “thinking again”

Semantic Motivation based on co-existence of direct and figurative meanings of the same word EX a watchdog – ”a dog kept for watching property” a watchdog – “a watchful human guardian” (semantic motivation)

• PRACTICE

Analyze the meaning of the words. Define the type of motivation a) morphologically motivated b) semantically motivated • Driver • Leg • Horse • Wall • Hand-made • Careless • piggish

Analyze the meaning of the words. Define the type of motivation a) morphologically motivated b) semantically motivated • Driver Someone who drives a vehicle morphologically motivated • Leg The part of a piece of furniture such as a table semantically motivated • Horse A piece of equipment shaped like a box, used in gymnastics semantically motivated

• Wall Emotions or behavior preventing people from feeling close semantically motivated • Hand-made Made by hand, not machine morphologically motivated • Careless Not taking enough care morphologically motivated • Piggish Selfish semantically motivated

what she said but it didn’t sink in my mind “do down to the bottom” ‘to be accepted by mind” semantic motivation I heard Why are you trying to pin the blame on me? “fasten smth somewhere using a pin” – ”to blame smb” semantic motivation I was following the man when he dived into a pub. “jump into deep water” – ”to enter into suddenly” semantic motivation You should be ashamed of yourself, crawling to the director like that “to move along on hands and knees close to the ground” – “to behave very humbly in order to win favor” semantic motivation

In linguistics, word order (also known as linear order) is the order of the syntactic constituents of a language. Word order typology studies it from a cross-linguistic perspective, and examines how different languages employ different orders. Correlations between orders found in different syntactic sub-domains are also of interest. The primary word orders that are of interest are

- the constituent order of a clause, namely the relative order of subject, object, and verb;

- the order of modifiers (adjectives, numerals, demonstratives, possessives, and adjuncts) in a noun phrase;

- the order of adverbials.

Some languages use relatively fixed word order, often relying on the order of constituents to convey grammatical information. Other languages—often those that convey grammatical information through inflection—allow more flexible word order, which can be used to encode pragmatic information, such as topicalisation or focus. However, even languages with flexible word order have a preferred or basic word order,[1] with other word orders considered «marked».[2]

Constituent word order is defined in terms of a finite verb (V) in combination with two arguments, namely the subject (S), and object (O).[3][4][5][6] Subject and object are here understood to be nouns, since pronouns often tend to display different word order properties.[7][8] Thus, a transitive sentence has six logically possible basic word orders:

- about half of the world’s languages deploy subject–object–verb order (SOV);

- about one-third of the world’s languages deploy subject–verb–object order (SVO);

- a smaller fraction of languages deploy verb–subject–object (VSO) order;

- the remaining three arrangements are rarer: verb–object–subject (VOS) is slightly more common than object–verb–subject (OVS), and object–subject–verb (OSV) is the rarest by a significant margin.[9]

Constituent word orders[edit]

These are all possible word orders for the subject, object, and verb in the order of most common to rarest (the examples use «she» as the subject, «loves» as the verb, and «him» as the object):

- SOV is the order used by the largest number of distinct languages; languages using it include Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Turkish, the Indo-Aryan languages and the Dravidian languages. Some, like Persian, Latin and Quechua, have SOV normal word order but conform less to the general tendencies of other such languages. A sentence glossing as «She him loves» would be grammatically correct in these languages.

- SVO languages include English, Spanish, Portuguese, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian,[10] the Chinese languages and Swahili, among others. «She loves him.»

- VSO languages include Classical Arabic, Biblical Hebrew, the Insular Celtic languages, and Hawaiian. «Loves she him.»

- VOS languages include Fijian and Malagasy. «Loves him she.»

- OVS languages include Hixkaryana. «Him loves she.»

- OSV languages include Xavante and Warao. «Him she loves.»

Sometimes patterns are more complex: some Germanic languages have SOV in subordinate clauses, but V2 word order in main clauses, SVO word order being the most common. Using the guidelines above, the unmarked word order is then SVO.

Many synthetic languages such as Latin, Greek, Persian, Romanian, Assyrian, Assamese, Russian, Turkish, Korean, Japanese, Finnish, Arabic and Basque have no strict word order; rather, the sentence structure is highly flexible and reflects the pragmatics of the utterance. However, also in languages of this kind there is usually a pragmatically neutral constituent order that is most commonly encountered in each language.

Topic-prominent languages organize sentences to emphasize their topic–comment structure. Nonetheless, there is often a preferred order; in Latin and Turkish, SOV is the most frequent outside of poetry, and in Finnish SVO is both the most frequent and obligatory when case marking fails to disambiguate argument roles. Just as languages may have different word orders in different contexts, so may they have both fixed and free word orders. For example, Russian has a relatively fixed SVO word order in transitive clauses, but a much freer SV / VS order in intransitive clauses.[citation needed] Cases like this can be addressed by encoding transitive and intransitive clauses separately, with the symbol «S» being restricted to the argument of an intransitive clause, and «A» for the actor/agent of a transitive clause. («O» for object may be replaced with «P» for «patient» as well.) Thus, Russian is fixed AVO but flexible SV/VS. In such an approach, the description of word order extends more easily to languages that do not meet the criteria in the preceding section. For example, Mayan languages have been described with the rather uncommon VOS word order. However, they are ergative–absolutive languages, and the more specific word order is intransitive VS, transitive VOA, where the S and O arguments both trigger the same type of agreement on the verb. Indeed, many languages that some thought had a VOS word order turn out to be ergative like Mayan.

Distribution of word order types[edit]

Every language falls under one of the six word order types; the unfixed type is somewhat disputed in the community, as the languages where it occurs have one of the dominant word orders but every word order type is grammatically correct.

The table below displays the word order surveyed by Dryer. The 2005 study[11] surveyed 1228 languages, and the updated 2013 study[8] investigated 1377 languages. Percentage was not reported in his studies.

| Word Order | Number (2005) | Percentage (2005) | Number (2013) | Percentage (2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 497 | 40.5% | 565 | 41.0% |

| SVO | 435 | 35.4% | 488 | 35.4% |

| VSO | 85 | 6.9% | 95 | 6.9% |

| VOS | 26 | 2.1% | 25 | 1.8% |

| OVS | 9 | 0.7% | 11 | 0.8% |

| OSV | 4 | 0.3% | 4 | 0.3% |

| Unfixed | 172 | 14.0% | 189 | 13.7% |

Hammarström (2016)[12] calculated the constituent orders of 5252 languages in two ways. His first method, counting languages directly, yielded results similar to Dryer’s studies, indicating both SOV and SVO have almost equal distribution. However, when stratified by language families, the distribution showed that the majority of the families had SOV structure, meaning that a small number of families contain SVO structure.

| Word Order | No. of Languages | Percentage | No. of Families | Percentage[a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOV | 2275 | 43.3% | 239 | 56.6% |

| SVO | 2117 | 40.3% | 55 | 13.0% |

| VSO | 503 | 9.5% | 27 | 6.3% |

| VOS | 174 | 3.3% | 15 | 3.5% |

| OVS | 40 | 0.7% | 3 | 0.7% |

| OSV | 19 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Unfixed | 124 | 2.3% | 26 | 6.1% |

Functions of constituent word order[edit]

Fixed word order is one out of many ways to ease the processing of sentence semantics and reducing ambiguity. One method of making the speech stream less open to ambiguity (complete removal of ambiguity is probably impossible) is a fixed order of arguments and other sentence constituents. This works because speech is inherently linear. Another method is to label the constituents in some way, for example with case marking, agreement, or another marker. Fixed word order reduces expressiveness but added marking increases information load in the speech stream, and for these reasons strict word order seldom occurs together with strict morphological marking, one counter-example being Persian.[1]

Observing discourse patterns, it is found that previously given information (topic) tends to precede new information (comment). Furthermore, acting participants (especially humans) are more likely to be talked about (to be topic) than things simply undergoing actions (like oranges being eaten). If acting participants are often topical, and topic tends to be expressed early in the sentence, this entails that acting participants have a tendency to be expressed early in the sentence. This tendency can then grammaticalize to a privileged position in the sentence, the subject.

The mentioned functions of word order can be seen to affect the frequencies of the various word order patterns: The vast majority of languages have an order in which S precedes O and V. Whether V precedes O or O precedes V, however, has been shown to be a very telling difference with wide consequences on phrasal word orders.[13]

Semantics of word order[edit]

In many languages, standard word order can be subverted in order to form questions or as a means of emphasis. In languages such as O’odham and Hungarian, which are discussed below, almost all possible permutations of a sentence are grammatical, but not all of them are used.[14] In languages such as English and German, word order is used as a means of turning declarative into interrogative sentences:

A: ‘Wen liebt Kate?’ / ‘Kate liebt wen?’ [Whom does Kate love? / Kate loves whom?] (OVS/SVO)

B: ‘Sie liebt Mark’ / ‘Mark ist der, den sie liebt’ [She loves Mark / It is Mark whom she loves.] (SVO/OSV)

C: ‘Liebt Kate Mark?’ [Does Kate love Mark?] (VSO)

In (A), the first sentence shows the word order used for wh-questions in English and German. The second sentence is an echo question; it would only be uttered after receiving an unsatisfactory or confusing answer to a question. One could replace the word wen [whom] (which indicates that this sentence is a question) with an identifier such as Mark: ‘Kate liebt Mark?’ [Kate loves Mark?]. In that case, since no change in word order occurs, it is only by means of stress and tone that we are able to identify the sentence as a question.

In (B), the first sentence is declarative and provides an answer to the first question in (A). The second sentence emphasizes that Kate does indeed love Mark, and not whomever else we might have assumed her to love. However, a sentence this verbose is unlikely to occur in everyday speech (or even in written language), be it in English or in German. Instead, one would most likely answer the echo question in (A) simply by restating: Mark!. This is the same for both languages.

In yes–no questions such as (C), English and German use subject-verb inversion. But, whereas English relies on do-support to form questions from verbs other than auxiliaries, German has no such restriction and uses inversion to form questions, even from lexical verbs.

Despite this, English, as opposed to German, has very strict word order. In German, word order can be used as a means to emphasize a constituent in an independent clause by moving it to the beginning of the sentence. This is a defining characteristic of German as a V2 (verb-second) language, where, in independent clauses, the finite verb always comes second and is preceded by one and only one constituent. In closed questions, V1 (verb-first) word order is used. And lastly, dependent clauses use verb-final word order. However, German cannot be called an SVO language since no actual constraints are imposed on the placement of the subject and object(s), even though a preference for a certain word-order over others can be observed (such as putting the subject after the finite verb in independent clauses unless it already precedes the verb[clarification needed]).

Phrase word orders and branching[edit]

The order of constituents in a phrase can vary as much as the order of constituents in a clause. Normally, the noun phrase and the adpositional phrase are investigated. Within the noun phrase, one investigates whether the following modifiers occur before and/or after the head noun.

- adjective (red house vs house red)

- determiner (this house vs house this)

- numeral (two houses vs houses two)

- possessor (my house vs house my)

- relative clause (the by me built house vs the house built by me)

Within the adpositional clause, one investigates whether the languages makes use of prepositions (in London), postpositions (London in), or both (normally with different adpositions at both sides) either separately (For whom? or Whom for?) or at the same time (from her away; Dutch example: met hem mee meaning together with him).

There are several common correlations between sentence-level word order and phrase-level constituent order. For example, SOV languages generally put modifiers before heads and use postpositions. VSO languages tend to place modifiers after their heads, and use prepositions. For SVO languages, either order is common.

For example, French (SVO) uses prepositions (dans la voiture, à gauche), and places adjectives after (une voiture spacieuse). However, a small class of adjectives generally go before their heads (une grande voiture). On the other hand, in English (also SVO) adjectives almost always go before nouns (a big car), and adverbs can go either way, but initially is more common (greatly improved). (English has a very small number of adjectives that go after the heads, such as extraordinaire, which kept its position when borrowed from French.) Russian places numerals after nouns to express approximation (шесть домов=six houses, домов шесть=circa six houses).

Pragmatic word order[edit]

Some languages do not have a fixed word order and often use a significant amount of morphological marking to disambiguate the roles of the arguments. However, the degree of marking alone does not indicate whether a language uses a fixed or free word order: some languages may use a fixed order even when they provide a high degree of marking, while others (such as some varieties of Datooga) may combine a free order with a lack of morphological distinction between arguments.

Typologically, there is a trend that high-animacy actors are more likely to be topical than low-animacy undergoers; this trend can come through even in languages with free word order, giving a statistical bias for SO order (or OS order in ergative systems; however, ergative systems do not always extend to the highest levels of animacy, sometimes giving way to an accusative system (see split ergativity)).[15]

Most languages with a high degree of morphological marking have rather flexible word orders, such as Polish, Hungarian, Portuguese, Latin, Albanian, and O’odham. In some languages, a general word order can be identified, but this is much harder in others.[16] When the word order is free, different choices of word order can be used to help identify the theme and the rheme.

Hungarian[edit]

Word order in Hungarian sentences is changed according to the speaker’s communicative intentions. Hungarian word order is not free in the sense that it must reflect the information structure of the sentence, distinguishing the emphatic part that carries new information (rheme) from the rest of the sentence that carries little or no new information (theme).

The position of focus in a Hungarian sentence is immediately before the verb, that is, nothing can separate the emphatic part of the sentence from the verb.

For «Kate ate a piece of cake«, the possibilities are:

- «Kati megevett egy szelet tortát.» (same word order as English) [«Kate ate a piece of cake.«]

- «Egy szelet tortát Kati evett meg.» (emphasis on agent [Kate]) [«A piece of cake Kate ate.«] (One of the pieces of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- «Kati evett meg egy szelet tortát.» (also emphasis on agent [Kate]) [«Kate ate a piece of cake.«] (Kate was the one eating one piece of cake.)

- «Kati egy szelet tortát evett meg.» (emphasis on object [cake]) [«Kate a piece of cake ate.»] (Kate ate a piece of cake – cf. not a piece of bread.)

- «Egy szelet tortát evett meg Kati.» (emphasis on number [a piece, i.e. only one piece]) [«A piece of cake ate Kate.»] (Only one piece of cake was eaten by Kate.)

- «Megevett egy szelet tortát Kati.» (emphasis on completeness of action) [«Ate a piece of cake Kate.»] (A piece of cake had been finished by Kate.)

- «Megevett Kati egy szelet tortát.» (emphasis on completeness of action) [«Ate Kate a piece of cake.«] (Kate finished with a piece of cake.)

The only freedom in Hungarian word order is that the order of parts outside the focus position and the verb may be freely changed without any change to the communicative focus of the sentence, as seen in sentences 2 and 3 as well as in sentences 6 and 7 above. These pairs of sentences have the same information structure, expressing the same communicative intention of the speaker, because the part immediately preceding the verb is left unchanged.

Note that the emphasis can be on the action (verb) itself, as seen in sentences 1, 6 and 7, or it can be on parts other than the action (verb), as seen in sentences 2, 3, 4 and 5. If the emphasis is not on the verb, and the verb has a co-verb (in the above example ‘meg’), then the co-verb is separated from the verb, and always follows the verb. Also note that the enclitic -t marks the direct object: ‘torta’ (cake) + ‘-t’ -> ‘tortát’.

Hindi-Urdu[edit]

Hindi-Urdu (Hindustani) is essentially a verb-final (SOV) language, with relatively free word order since in most cases postpositions mark quite explicitly the relationships of noun phrases with other constituents of the sentence.[17] Word order in Hindustani usually does not signal grammatical functions.[18] Constituents can be scrambled to express different information structural configurations, or for stylistic reasons. The first syntactic constituent in a sentence is usually the topic,[19][18] which may under certain conditions be marked by the particle «to» (तो / تو), similar in some respects to Japanese topic marker は (wa).[20][21][22][23] Some rules governing the position of words in a sentence are as follows:

- An adjective comes before the noun it modifies in its unmarked position. However, the possessive and reflexive pronominal adjectives can occur either to the left or to the right of the noun it describes.

- Negation must come either to the left or to the right of the verb it negates. For compound verbs or verbal construction using auxiliaries the negation can occur either to the left of the first verb, in-between the verbs or to the right of the second verb (the default position being to the left of the main verb when used with auxiliary and in-between the primary and the secondary verb when forming a compound verb).

- Adverbs usually precede the adjectives they qualify in their unmarked position, but when adverbs are constructed using the instrumental case postposition se (से /سے) (which qualifies verbs), their position in the sentence becomes free. However, since both the instrumental and the ablative case are marked by the same postposition «se» (से /سے), when both are present in a sentence then the quantity they modify cannot appear adjacent to each other[clarification needed].[24][18]

- «kyā » (क्या / کیا) «what» as the yes-no question marker occurs at the beginning or the end of a clause as its unmarked positions but it can be put anywhere in the sentence except the preverbal position, where instead it is interpreted as interrogative «what».

Some of all the possible word order permutations of the sentence «The girl received a gift from the boy on her birthday.» are shown below.

|

|

|

|

|

Portuguese[edit]

In Portuguese, clitic pronouns and commas allow many different orders:[citation needed]

- «Eu vou entregar a você amanhã.» [«I will deliver to you tomorrow.»] (same word order as English)

- «Entregarei a você amanhã.» [«{I} will deliver to you tomorrow.»]

- «Eu lhe entregarei amanhã.» [«I to you will deliver tomorrow.»]

- «Entregar-lhe-ei amanhã.» [«Deliver to you {I} will tomorrow.»] (mesoclisis)

- «A ti, eu entregarei amanhã.» [«To you I will deliver tomorrow.»]

- «A ti, entregarei amanhã.» [«To you deliver {I} will tomorrow.»]

- «Amanhã, entregar-te-ei» [«Tomorrow {I} will deliver to you»]

- «Poderia entregar, eu, a você amanhã?» [«Could deliver I to you tomorrow?]

Braces ({ }) are used above to indicate omitted subject pronouns, which may be implicit in Portuguese. Because of conjugation, the grammatical person is recovered.

Latin[edit]

In Latin, the endings of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and pronouns allow for extremely flexible order in most situations. Latin lacks articles.

The Subject, Verb, and Object can come in any order in a Latin sentence, although most often (especially in subordinate clauses) the verb comes last.[25] Pragmatic factors, such as topic and focus, play a large part in determining the order. Thus the following sentences each answer a different question:[26]

- «Romulus Romam condidit.» [«Romulus founded Rome»] (What did Romulus do?)

- «Hanc urbem condidit Romulus.» [«Romulus founded this city»] (Who founded this city?)

- «Condidit Romam Romulus.» [«Romulus founded Rome»] (What happened?)

Latin prose often follows the word order «Subject, Direct Object, Indirect Object, Adverb, Verb»,[27] but this is more of a guideline than a rule. Adjectives in most cases go before the noun they modify,[28] but some categories, such as those that determine or specify (e.g. Via Appia «Appian Way»), usually follow the noun. In Classical Latin poetry, lyricists followed word order very loosely to achieve a desired scansion.

Albanian[edit]

Due to the presence of grammatical cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative, and in some cases or dialects vocative and locative) applied to nouns, pronouns and adjectives, the Albanian language permits a large number of positional combination of words. In spoken language a word order differing from the most common S-V-O helps the speaker putting emphasis on a word, thus changing partially the message delivered. Here is an example:

- «Marku më dha një dhuratë (mua).» [«Mark (me) gave a present to me.»] (neutral narrating sentence.)

- «Marku (mua) më dha një dhuratë.» [«Mark to me (me) gave a present.»] (emphasis on the indirect object, probably to compare the result of the verb on different persons.)

- «Marku një dhuratë më dha (mua).» [«Mark a present (me) gave to me»] (meaning that Mark gave her only a present, and not something else or more presents.)

- «Marku një dhuratë (mua) më dha.» [«Mark a present to me (me) gave»] (meaning that Mark gave a present only to her.)

- «Më dha Marku një dhuratë (mua).» [«Gave Mark to me a present.»] (neutral sentence, but puts less emphasis on the subject.)

- «Më dha një dhuratë Marku (mua).» [«Gave a present to me Mark.»] (probably is the cause of an event being introduced later.)

- «Më dha (mua) Marku një dhurate.» [«Gave to me Mark a present.»] (same as above.)

- «Më dha një dhuratë mua Marku» [«(Me) gave a present to me Mark.»] (puts emphasis on the fact that the receiver is her and not someone else.)

- «Një dhuratë më dha Marku (mua)» [«A present gave Mark to me.»] (meaning it was a present and not something else.)

- «Një dhuratë Marku më dha (mua)» [«A present Mark gave to me.»] (puts emphasis on the fact that she got the present and someone else got something different.)

- «Një dhuratë (mua) më dha Marku.» [«A present to me gave Mark.»] (no particular emphasis, but can be used to list different actions from different subjects.)

- «Një dhuratë (mua) Marku më dha.» [«A present to me Mark (me) gave»] (remembers that at least a present was given to her by Mark.)

- «Mua më dha Marku një dhuratë.» [«To me (me) gave Mark a present.» (is used when Mark gave something else to others.)

- «Mua një dhuratë më dha Marku.» [«To me a present (me) gave Mark.»] (emphasis on «to me» and the fact that it was a present, only one present or it was something different from usual.)

- «Mua Marku një dhuratë më dha» [«To me Mark a present (me) gave.»] (Mark gave her only one present.)

- «Mua Marku më dha një dhuratë» [«To me Mark (me) gave a present.»] (puts emphasis on Mark. Probably the others didn’t give her present, they gave something else or the present wasn’t expected at all.)

In these examples, «(mua)» can be omitted when not in first position, causing a perceivable change in emphasis; the latter being of different intensity. «Më» is always followed by the verb. Thus, a sentence consisting of a subject, a verb and two objects (a direct and an indirect one), can be

expressed in six different ways without «mua», and in twenty-four different ways with «mua», adding up to thirty possible combinations.

O’odham (Papago-Pima)[edit]

O’odham is a language that is spoken in southern Arizona and Northern Sonora, Mexico. It has free word order, with only the auxiliary bound to one spot. Here is an example, in literal translation:[14]

- «Wakial ‘o g wipsilo ha-cecposid.» [Cowboy is the calves them branding.] (The cowboy is branding the calves.)

- «Wipsilo ‘o ha-cecposid g wakial.» [Calves is them branding the cowboy.]

- «Ha-cecposid ‘o g wakial g wipsilo.» [Them Branding is the cowboy the calves.]

- «Wipsilo ‘o g wakial ha-cecposid.» [Calves is the cowboy them branding.]

- «Ha-cecposid ‘o g wipsilo g wakial.» [Them branding is the calves the cowboy.]

- «Wakial ‘o ha-cecposid g wipsilo.» [Cowboy is them branding the calves.]

These examples are all grammatically-valid variations on the sentence «The cowboy is branding the calves,» but some are rarely found in natural speech, as is discussed in Grammaticality.

Other issues with word order[edit]

Language change[edit]

Languages change over time. When language change involves a shift in a language’s syntax, this is called syntactic change. An example of this is found in Old English, which at one point had flexible word order, before losing it over the course of its evolution.[29] In Old English, both of the following sentences would be considered grammatically correct:

- «Martianus hæfde his sunu ær befæst.» [Martianus had his son earlier established.] (Martianus had earlier established his son.)

- «Se wolde gelytlian þone lyfigendan hælend.» [He would diminish the living saviour.]

This flexibility continues into early Middle English, where it seems to drop out of usage.[30] Shakespeare’s plays use OV word order frequently, as can be seen from this example:

- «It was our selfe thou didst abuse.»[31]

A modern speaker of English would possibly recognise this as a grammatically comprehensible sentence, but nonetheless archaic. There are some verbs, however, that are entirely acceptable in this format:

- «Are they good?»[32]

This is acceptable to a modern English speaker and is not considered archaic. This is due to the verb «to be», which acts as both auxiliary and main verb. Similarly, other auxiliary and modal verbs allow for VSO word order («Must he perish?»). Non-auxiliary and non-modal verbs require insertion of an auxiliary to conform to modern usage («Did he buy the book?»). Shakespeare’s usage of word order is not indicative of English at the time, which had dropped OV order at least a century before.[33]

This variation between archaic and modern can also be shown in the change between VSO to SVO in Coptic, the language of the Christian Church in Egypt.[34]

Dialectal variation[edit]

There are some languages where a certain word order is preferred by one or more dialects, while others use a different order. One such case is Andean Spanish, spoken in Peru. While Spanish is classified as an SVO language,[35] the variation of Spanish spoken in Peru has been influenced by contact with Quechua and Aymara, both SOV languages.[36] This has had the effect of introducing OV (object-verb) word order into the clauses of some L1 Spanish speakers (moreso than would usually be expected), with more L2 speakers using similar constructions.

Poetry[edit]

Poetry and stories can use different word orders to emphasize certain aspects of the sentence. In English, this is called anastrophe. Here is an example:

«Kate loves Mark.»

«Mark, Kate loves.»

Here SVO is changed to OSV to emphasize the object.

Translation[edit]

Differences in word order complicate translation and language education – in addition to changing the individual words, the order must also be changed. The area in Linguistics that is concerned with translation and education is language acquisition. The reordering of words can run into problems, however, when transcribing stories. Rhyme scheme can change, as well as the meaning behind the words. This can be especially problematic when translating poetry.

See also[edit]

- Antisymmetry

- Information flow

- Language change

Notes[edit]

- ^ Hammarström included families with no data in his count (58 out of 424 = 13,7%), but did not include them in the list. This explains why the percentages do not sum to 100% in this column.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Comrie, Bernard. (1981). Language universals and linguistic typology: syntax and morphology (2nd ed). University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ^ Sakel, Jeanette (2015). Study Skills for Linguistics. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 9781317530107.

- ^ Hengeveld, Kees (1992). Non-verbal predication. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-013713-5.

- ^ Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1993). «Das Nomen – eine universale Kategorie?» [The noun – a universal category?]. STUF — Language Typology and Universals (in German). 46 (1–4). doi:10.1524/stuf.1993.46.14.187. S2CID 192204875.

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (November 2007). «Word Classes: Word Classes». Language and Linguistics Compass. 1 (6): 709–726. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00030.x. S2CID 5404720.

- ^ Rijkhoff, Jan (2004), The Noun Phrase, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926964-5.

- ^ Greenberg, Joseph H. (1963). «Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements» (PDF). In Greenberg, Joseph H. (ed.). Universals of Human Language. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. pp. 73–113. doi:10.1515/9781503623217-005. ISBN 9781503623217. S2CID 2675113.

- ^ a b Dryer, Matthew S. (2013). «Order of Subject, Object and Verb». In Dryer, Matthew S.; Haspelmath, Martin (eds.). The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ^ Tomlin, Russel S. (1986). Basic Word Order: Functional Principles. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-415-72357-4.

- ^ Kordić, Snježana (2006) [1st pub. 1997]. Serbo-Croatian. Languages of the World/Materials ; 148. Munich & Newcastle: Lincom Europa. pp. 45–46. ISBN 3-89586-161-8. OCLC 37959860. OL 2863538W. Contents. Summary. [Grammar book].

- ^ Dryer, M. S. (2005). «Order of Subject, Object, and Verb». In Haspelmath, M. (ed.). The World Atlas of Language Structures.

- ^ Hammarström, H. (2016). «Linguistic diversity and language evolution». Journal of Language Evolution. 1 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1093/jole/lzw002.

- ^ Dryer, Matthew S. (1992). «The Greenbergian word order correlations». Language. 68 (1): 81–138. doi:10.1353/lan.1992.0028. JSTOR 416370. S2CID 9693254. Project MUSE 452860.

- ^ a b Hale, Kenneth L. (1992). «Basic word order in two «free word order» languages». Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. Typological Studies in Language. Vol. 22. p. 63. doi:10.1075/tsl.22.03hal. ISBN 978-90-272-2905-2.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard (1981). Language Universals and Linguistic Typology: Syntax and Morphology (2nd edn). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Rude, Noel (1992). «Word order and topicality in Nez Perce». Pragmatics of Word Order Flexibility. Typological Studies in Language. Vol. 22. p. 193. doi:10.1075/tsl.22.08rud. ISBN 978-90-272-2905-2.

- ^ Kachru, Yamuna (2006). Hindi. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 159–160. ISBN 90-272-3812-X.

- ^ a b c Mohanan, Tara (1994). «Case OCP: A Constraint on Word Order in Hindi». In Butt, Miriam; King, Tracy Holloway; Ramchand, Gillian (eds.). Theoretical Perspectives on Word Order in South Asian Languages. Center for the Study of Language (CSLI). pp. 185–216. ISBN 978-1-881526-49-0.

- ^ Gambhir, Surendra Kumar (1984). The East Indian speech community in Guyana: a sociolinguistic study with special reference to koine formation (Thesis). OCLC 654720956.[page needed]

- ^ Kuno 1981[full citation needed]

- ^ Kidwai 2000[full citation needed]

- ^ Patil, Umesh; Kentner, Gerrit; Gollrad, Anja; Kügler, Frank; Fery, Caroline; Vasishth, Shravan (17 November 2008). «Focus, Word Order and Intonation in Hindi». Journal of South Asian Linguistics. 1.

- ^ Vasishth, Shravan (2004). «Discourse Context and Word Order Preferences in Hindi». The Yearbook of South Asian Languages and Linguistics (2004). pp. 113–128. doi:10.1515/9783110179897.113. ISBN 978-3-11-020776-7.

- ^ Spencer, Andrew (2005). «Case in Hindi». The Proceedings of the LFG ’05 Conference (PDF). pp. 429–446.

- ^ Scrivner, Olga (June 2015). A Probabilistic Approach in Historical Linguistics. Word Order Change in Infinitival Clauses: from Latin to Old French (Thesis). p. 32. hdl:2022/20230.

- ^ Spevak, Olga (2010). Constituent Order in Classical Latin Prose, p. 1, quoting Weil (1844).

- ^ Devine, Andrew M. & Laurence D. Stephens (2006), Latin Word Order, p. 79.

- ^ Walker, Arthur T. (1918). «Some Facts of Latin Word-Order». The Classical Journal. 13 (9): 644–657. JSTOR 3288352.

- ^ Taylor, Ann; Pintzuk, Susan (1 December 2011). «The interaction of syntactic change and information status effects in the change from OV to VO in English». Catalan Journal of Linguistics. 10: 71. doi:10.5565/rev/catjl.61.

- ^ Trips, Carola (2002). From OV to VO in Early Middle English. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today. Vol. 60. doi:10.1075/la.60. ISBN 978-90-272-2781-2.

- ^ Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616, author. (4 February 2020). Henry V. ISBN 978-1-9821-0941-7. OCLC 1105937654. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1941). Much Ado about Nothing. Boston, USA: Ginn and Company. pp. 12, 16.

- ^ Crystal, David (2012). Think on my Words: Exploring Shakespeare’s Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-139-19699-4.

- ^ Loprieno, Antonio (2000). «From VSO to SVO? Word Order and Rear Extraposition in Coptic». Stability, Variation and Change of Word-Order Patterns over Time. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 213. pp. 23–39. doi:10.1075/cilt.213.05lop. ISBN 978-90-272-3720-0.

- ^ «Spanish». The Romance Languages. 2003. pp. 91–142. doi:10.4324/9780203426531-7. ISBN 978-0-203-42653-1.

- ^ Klee, Carol A.; Tight, Daniel G.; Caravedo, Rocio (1 December 2011). «Variation and change in Peruvian Spanish word order: language contact and dialect contact in Lima». Southwest Journal of Linguistics. 30 (2): 5–32. Gale A348978474.

Further reading[edit]

- A collection of papers on word order by a leading scholar, some downloadable

- Basic word order in English clearly illustrated with examples.

- Bernard Comrie, Language Universals and Linguistic Typology: Syntax and Morphology (1981) – this is the authoritative introduction to word order and related subjects.

- Order of Subject, Object, and Verb (PDF). A basic overview of word order variations across languages.

- Haugan, Jens, Old Norse Word Order and Information Structure. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. 2001. ISBN 82-471-5060-3

- Rijkhoff, Jan (2015). «Word Order». International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (PDF). pp. 644–656. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.53031-1. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5.

- Song, Jae Jung (2012), Word Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87214-0 & ISBN 978-0-521-69312-7

In English, the word order is strict. That means we can’t place parts of the sentence wherever we want, but we should follow some certain rules when making sentences. These rules apply not only to formal language but also to everyday spoken English. So, we should learn and always follow them.

Direct word order and inversion

When the sentence is positive (affirmative), the word order is direct. That means the verb follows the subject.

Examples

Caroline is a local celebrity. Caroline = subject, is = verb

We work remotely. We = subject, work = verb

You have been learning Spanish for two years. You= subject, have been learning = verb

In questions (interrogative sentences) the subject and the verb swap places. We call it indirect word order, or inversion.

Examples

Am I right? WRONG I am right?

How old are they? WRONG How old they are?

What day is it today? WRONG What day it is today?

If there is an auxiliary verb, its first word will precede the subject.

Examples

Are you sleeping?

Have you read my message?

Will you help me, please?

Has anyone been looking for me?

Will he have finished the job by 5 o’clock?

Direct and indirect objects

The object normally goes right after the verb. We don’t put any other words between them.

I like my job very much. WRONG like very much my job

He meets his friends every Friday. WRONG meets every Friday his friends

In the examples above, the object is direct. A direct object answers the question «whom» or «what» and there is no preposition after the verb. If we can’t put the object without a preposition (talk to smb, agree with smb, rely on smb), the object is indirect.

I’m not satisfied with my test score.

Let’s talk about the new project.

Now, if we have two objects, one is indirect and the other is direct, then the direct object has the priority to go first.

The professor explained the concept to the students. WRONG to the student the concept

He said nothing about those errors. WRONG about those errors nothing

If there are two direct objects and one of them is a pronoun, the pronoun goes behind the verb.

Could you show me the way, please? WRONG the way me

They wished her luck. WRONG luck her

Place and time

Expressions of time and place usually go together after the verb and the object (if there is one). We first indicate the place (where, where to) and then the time (when, how often, how long).

Examples

We go {to the theatre} {every month}. where=to the theatre, how often=every month

There were lots of people {in the park} {on Sunday}. where=in the park, when=on Sunday

Jim will give me a lift {to the station} {after the meeting}. where to=to the station, when=after the meeting

lt is often possible to put time at the beginning of the sentence.

At this time tomorrow, we’ll be going to the airport.

Sometimes I want to be alone.

Summary

Let’s briefly sum up the rules:

- Positive sentence: subject + verb. Question sentence: verb + subject

- Do not split the verb and the object

- Direct objects go before the indirect objects

- If one of two direct objects is a pronoun, it goes first

- Place goes before time

![Meaning and Sound-formare not identical

different

EX. dove - [dΛv]... Meaning and Sound-formare not identical

different

EX. dove - [dΛv]...](https://documents.infourok.ru/2d0c9b9d-1c12-4da2-8c1e-80496902c301/slide_10.jpg)

![Meaning and Sound-form are not identical different EX. dove - [dΛv] English [golub’] Russian Meaning and Sound-form are not identical different EX. dove - [dΛv] English [golub’] Russian](https://present5.com/presentation/54919015_285694613/image-10.jpg)

![Meaning and Sound-form nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages EX. [kot] Meaning and Sound-form nearly identical sound-forms have different meanings in different languages EX. [kot]](https://present5.com/presentation/54919015_285694613/image-11.jpg)