1

(be) a bad choice of words

неудачно выразиться

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > (be) a bad choice of words

2

a bad choice of words

Общая лексика: неудачно выразиться

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > a bad choice of words

3

a cautious choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > a cautious choice of words

4

be meticulous in the choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > be meticulous in the choice of words

5

be unhappy in choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > be unhappy in choice of words

6

be wary in the choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > be wary in the choice of words

7

cautious choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > cautious choice of words

8

to be meticulous in the choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > to be meticulous in the choice of words

9

to be trouble in the choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > to be trouble in the choice of words

10

to be unhappy in (one’s) choice of words

неудачно выбирать слова

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > to be unhappy in (one’s) choice of words

11

to be wary in the choice of words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > to be wary in the choice of words

12

to be unhappy in choice of words

Общая лексика: неудачно выбирать слова

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > to be unhappy in choice of words

13

(a) neat choice of words

удачное выражение/удачный выбор слов

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > (a) neat choice of words

14

(an) unhappy choice of words

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > (an) unhappy choice of words

15

he is very scrupulous in the choice of his words

Универсальный англо-русский словарь > he is very scrupulous in the choice of his words

16

about

I [ə’baut]

adv

1) приблизительно, почти, около

2) собираться, быть готовым

She had her coat on and was about to leave. — Она была уже в пальто и собиралась выходить.

The train is about to start. — Поезд сейчас тронется.

•

CHOICE OF WORDS:

(1.) Русские наречия степени около, приблизительно, примерно, почти передаются с некоторым различием в значении английскими наречиями about, around, nearly, almost. Когда речь идет о движении в пространстве или во времени или о том, что поддается измерению, about обозначает: a little more or less than больше или меньше обозначенного предмета или предела; it is about six сейчас около шести/приблизительно шесть — может значить без нескольких минут шесть или несколько минут седьмого. Almost указывает на то, что предел или предмет не достигнут, но, что до этого остается очень мало времени или расстояния: almost/about — very close to the point очень близко к желаемому. Nearly также указывает на некоторое расстояние от желаемого предела: nearly/about/not quite/not yet completely — указывает на то, что желаемый предел не достигнут. Ho almost обычно обозначает более близкую точку во времени или пространстве, чем nearly: it is about/almost/nearly six o’clock (lunch, time, two miles away, bed time) сейчас около шест /почти шесть/скоро шесть (скоро время ленча, около двух миль отсюда, пора идти спать) ср. he is about sixty ему примерно шестьдесят/около шестидесяти; he is nearly sixty ему к шестидесяти/скоро шестьдесят. Nearly дальше от обозначенной точки времени или пространства, чем almost. (2.) Наречия и наречные обороты приблизительности about, around, almost, nearly, more than, less than обычно стоят перед определяемым словом: he counted more than ten policemen in the crowd он насчитал более десяти полицейских в толпе. Наречные обороты or more, or less, or so обычно стоят после определяемого слова: he stayed there for a week or so (or more, or less).

II [ə’baut]

prp

употребляется при обозначении:

1) направления речи, мысли — о, об, относительно, насчёт, про

— book about smth, smb

— read about smth, smb

2) движения в пределах ограниченного пространства — по, везде, кругом, неподалёку

— walk about the room

— run about the garden

3) при себе, с собой

4) насчёт, о

5) в

•

CHOICE OF WORDS:

В значении 1. наряду с about могут употребляться предлоги on, of, concerning с одними и теми же существительными или глаголами. Однако они различаются стилистически и передают разные ситуации: about и of употребляются в бытовых ситуациях при сообщениях общего характера и обычно сочетаются с глаголами и существительными нейтральной лексики: to speak about/of money, to talk abou/oft the vacations, to think about/of the children. Предлоги concerning и on отличается от about и of более формальным характером, и сочетаются со словами более официального стиля: to deliver a report on ecology зачитать доклад по вопросам экологии; research concerning behavioural patterns исследование, касающееся поведенческих моделей. Предлог on предполагает обдуманный, формальный характер информации, более или менее академическую форму изложения и употребляется глаголами и существительными типа report, research, lecture: a book (a lecture, a film) on art книга (лекция, фильм) по искусству; to speak on literature говорить на литературные темы. Поэтому on не употребляется с глаголами ярко выраженной бытовой семантики типа to chat, to quarrel, etc.

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > about

17

accept

[ək’sept]

v

1) принимать, брать

He refused to accept favors from strangers. — Он отказался принимать одолжения от чужих ему людей.

He applied for the job and was accepted. — Он подал заявление на эту должность и был принят.

— accept a present

— accept smth from smb

2) удовлетворяться, соглашаться (с чем-либо, на что-либо), допускать (что-либо), принимать (что-либо), признавать (что-либо)

The report may be accepted conditionally. — Отчет может быть принят при некоторых условиях.

He accepted everything she said. — Он принимал все, что она говорила, на веру.

He couldn’t accept the situation. — Он не мог примириться с таким положением дел.

Don’t accept her story for the fact. — Не принимайте ее слов за истину.

— accept smb’s terms

— accept the price

— accept the offer

— accept smb’s explanation

— accept a cheque

— accept smb’s proposal

— accept the statement as a promise

•

CHOICE OF WORDS:

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > accept

18

ache

I [eɪk]

n

I have aches and pains all over. — У меня все тело болит.

Poor posture can cause neck ache, headaches and breathing problems. — Неправильная осанка может вызывать боли в шее, головные боли и осложнения с дыханием.

CHOICE OF WORDS:

(1). Русскому слову боль во всех остальных случаях, кроме вышеперечисленных, соответствует английское существительное pain или прилагательное painful, которые обозначают физическое или психическое страдание или болезненное ощущение в какой-либо части тела: to have a sharp (dull) pain in one’s arm (one’s leg, one’s side) почувствовать острую (тупую) боль в руке (ноге, боку); I have pain in the back или my back is still painful у меня все еще болит спина/у меня сохраняются боли в спине; my legs are stiff but not painful у меня затекли ноги, но боли нет. (2.) See ill, adj

USAGE:

Существительное ache редко употребляется самостоятельно. Оно обычно является частью сложного слова и, как правило, употребляется в сочетаниях: I have toothache (earache, stomachache, backache) у меня болит зуб (ухо, живот, спина). В этих сочетаниях существительное с компонентом ache употребляется без артикля, за исключением сочетания to have a headache.

II [eɪk]

v

1) болеть, испытывать боль

My ear (stomach, tooth) aches. — У меня болит ухо (живот, зуб).

It made my head ache. — У меня от этого разболелась голова.

He ached all over. — У него все болело.

— one’s head aches

2) сострадать, переживать о чём-либо

My heart aches at the sight of him/it makes my heart ache to see him. — Когда я вижу его, у меня сердце разрывается/у меня душа болит.

•

CHOICE OF WORDS:

Русскому глаголу болеть/болит соответствуют английские глаголы to ache и to hurt. Глагол to ache употребляется для обозначения длительной тупой, главным образом, физической боли, глагол to hurt указывает на боль, вызванную какой-либо внешней или внутренней причиной, не конкретизируя ее характера: my eyes hurt when I look at a bright light у меня болят глаза, когда я смотрю на яркий свет/мне больно смотреть на яркий свет, ср., my eyes ache all the time, I probably need stronger glasses у меня все время болят глаза, вероятно, мне нужны более сильные очки; let my hand go, you are hurting me отпусти мою руку, ты мне делаешь больно; don’t touch here, it hurts не трогай, мне больно

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > ache

19

as

I [æzˌ əz]

adv

1) (употребляется с прилагательными и наречиями для выражения подобия) такой же; так же, как

He hasn’t known me as long as you do. — Он знает меня не так давно, как вы/меньше, чем вы.

2) в такой же степени, как; так, как и

He looks as ill as he sounded on the phone. — На вид он столь же болен, как и казался, когда говорил по телефону.

— as much as you like

•

USAGE:

(1.) Русские сочетания такой же, столь же передаются наречием в обороте подобия (первое as в обороте as… as). В предложении оно может быть опущено (хотя и подразумевается), и в этих случаях остается неударный предлог (второе as): he is deaf as his grandfather он (такой же) глухой, как и его дед. (2.) Наречный оборот as.. as употребляется только с прилагательными или наречиями. Во всех других случаях подобие передается предлогом like: to swim like a fish плавать как рыба; to behave like a child вести себя как ребенок; to draw like a real artist рисовать как настоящий художник

II [æzˌ əz]

prp

(в русском языке часто передается формой творительного падежа) как, в качестве

I say it as your (a) friend. — Я говорю это вам как друг.

I respect him as a writer and as a man. — Я уважаю его как писателя и как человека.

— such as

— dressed as a policeman

— accept smb as an equal

— work as a teacher

CHOICE OF WORDS:

Следует обратить внимание на различие предложных оборотов с as и like с существительными, обозначающими род занятий: he worked as a teacher он работал учителем (и был учителем), ср. he speaks like a teacher он разговаривает как учитель (он не учитель, но у него манеры учителя).

III [æzˌ əz]

1) когда; в то время, как

He came in as I was speaking. — Он вошел в то время, когда я выступал.

He greeted us as he came in. — Он поздоровался с нами, когда вошел.

He came in as I was speaking. — Он вошел в то время, когда я выступал.

He is going to see Mary — said Tom as he observed Ned getting into his car. — Он едет к Мэри — сказал Том, наблюдая за тем как Нед усаживался в машину.

He greeted us as he came in. — Он поздоровался с нами, когда вошел.

As time passed things seemed to get worse. — По мере того как шло время, положение дел кажется, ухудшалось.

By listening to the women as they talked and by chance remarks from which he could deduce much that was left unsaid, Philip learned how little there was in common between the poor and the classes above them. They did not envy their betters. — Слушая женщин, когда они разговаривали, и из случайных замечаний, по которым он делал заключение о том, что сказано не было, Филипп узнал, как мало общего было между бедными и теми, кто принадлежал к классу людей повыше.

2) (обыкновенно стоит в начале сложного предложения) так как, потому что, поскольку

As he was not at home I left a message. — Так как его не было дома, я оставил ему записку.

I didn’t come as I busy. — Я не пришел, так как был занят.

As I am here, I’d better tell you every thing. — Раз я уже здесь, я лучше расскажу тебе все.

Covered with dust as he was, he didn’t want to come in. — Он не хотел входить, так как был весь в пыли.

As he was not at home I left a message. — Так как его не было дома, я оставил ему записку.

As to/for me I shan’t do that. — Что касается меня, лично я этого делать не буду.

I am late as it is. — Я и так опаздываю.

— as you know

— everything was done as arranged

— as it is

— as for me

3) так, как

•

CHOICE OF WORDS:

(1.) Придаточные предложения времени, указывающие на два одновременных действия или события, могут вводиться союзами as в значении 1., when и while. Выбор союза и различные формы времени глагола в этих случаях связаны с характером действия или события: (а.) если описываются два действия разной длительности, возможно употребление любого из трех союзов, при этом более длительное действие выражается формой Continuous, более короткое — формой Indefinite: as/when/while I was walking down the street I noticed a car at the entrance to the theatre когда я шел по улице, я заметил машину у подъезда театра; (б) если оба действия длительны, придаточное времени вводится союзами when/while, а глаголы главного и придаточного предложений обычно употребляются в форме Continuous: when/while she was cooking lunch I was looking through the papers пока/в то время как/когда она готовила ленч, я просматривал газеты. Если в этих случаях используется союз as, то глаголы употребляются в форме Indefinite: as I grow older I get less optimistic по мере того как я старею/расту, я теряю оптимизм; (в) если описаны два одновременных коротких действия, то придаточное времени вводится союзом as. Глаголы в главном и придаточном предложениях употребляются в форме Indefinite: he greeted everybody as he came in он вошел и поздоровался со всеми (когда он вошел, то…); I thought so as you started talking я так и подумал, когда вы начали выступать; I remembered her name as I left уже выходя (когда я почти вышел), я вспомнил, как ее зовут. В этих случаях союз when будет обозначать уже полностью законченное действие: я вспомнил, когда уже вышел. While в этом случае будет подчеркивать длительность, незавершенность действия: я вспомнил, когда выходил. (2.) Значение подобия такой как, так как передается в английском языке при помощи as и like. Like — предлог, образующий предложную группу с последующим существительным или местоимением: like me, she enjoys music как и я, она любит музыку; he cried like a child он плакал как ребенок. As — союз, вводящий придаточное предложение: she enjoys music just as I do. В разговорном языке like часто используется как союз вместо as: nobody understands him like (as) his mother does никто не понимает его так, как его мать. (3.) See after, cj; USAGE (1.). (4.) See until, cj

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > as

20

assess

[ə’ses]

v

оценивать, давать оценку размера чего-либо, давать оценку уровня чего-либо (ущерба, налога, штрафа, полезности); судить о полезности, качестве, размере чего-либо; определять величину чего-либо, определять сумму (налога, штрафа, ущерба)

The article will help people assess the recent changes in the tax policy. — Статья поможет оценить последние изменения в налоговой политике.

The value of this property was assessed at one million dollars. — Эта собственность была оценена в миллион долларов.

Also, the study did not assess the capabilities of other methods. — Кроме того, исследование не оценивало возможности других методов.

It is difficult to assess the damage caused by the fire as yet. — Пока трудно судить о размерах ущерба от пожара.

This test provides a good way to assess applicants’ suitability. — Этот тест дает хорошие результаты при определении пригодности претендентов на работу.

— assess a tax on land

— assess the damage

CHOICE OF WORDS:

see CHOICE OF WORDS, appraise, v

English-Russian combinatory dictionary > assess

The words a writer chooses are the building materials from which he or she constructs any given piece of writing—from a poem to a speech to a thesis on thermonuclear dynamics. Strong, carefully chosen words (also known as diction) ensure that the finished work is cohesive and imparts the meaning or information the author intended. Weak word choice creates confusion and dooms a writer’s work either to fall short of expectations or fail to make its point entirely.

Factors That Influence Good Word Choice

When selecting words to achieve the maximum desired effect, a writer must take a number of factors into consideration:

- Meaning: Words can be chosen for either their denotative meaning, which is the definition you’d find in a dictionary or the connotative meaning, which is the emotions, circumstances, or descriptive variations the word evokes.

- Specificity: Words that are concrete rather than abstract are more powerful in certain types of writing, specifically academic works and works of nonfiction. However, abstract words can be powerful tools when creating poetry, fiction, or persuasive rhetoric.

- Audience: Whether the writer seeks to engage, amuse, entertain, inform, or even incite anger, the audience is the person or persons for whom a piece of work is intended.

- Level of Diction: The level of diction an author chooses directly relates to the intended audience. Diction is classified into four levels of language:

- Formal which denotes serious discourse

- Informal which denotes relaxed but polite conversation

- Colloquial which denotes language in everyday usage

- Slang which denotes new, often highly informal words and phrases that evolve as a result sociolinguistic constructs such as age, class, wealth status, ethnicity, nationality, and regional dialects.

- Tone: Tone is an author’s attitude toward a topic. When employed effectively, tone—be it contempt, awe, agreement, or outrage—is a powerful tool that writers use to achieve a desired goal or purpose.

- Style: Word choice is an essential element in the style of any writer. While his or her audience may play a role in the stylistic choices a writer makes, style is the unique voice that sets one writer apart from another.

The Appropriate Words for a Given Audience

To be effective, a writer must choose words based on a number of factors that relate directly to the audience for whom a piece of work is intended. For example, the language chosen for a dissertation on advanced algebra would not only contain jargon specific to that field of study; the writer would also have the expectation that the intended reader possessed an advanced level of understanding in the given subject matter that at a minimum equaled, or potentially outpaced his or her own.

On the other hand, an author writing a children’s book would choose age-appropriate words that kids could understand and relate to. Likewise, while a contemporary playwright is likely to use slang and colloquialism to connect with the audience, an art historian would likely use more formal language to describe a piece of work about which he or she is writing, especially if the intended audience is a peer or academic group.

«Choosing words that are too difficult, too technical, or too easy for your receiver can be a communication barrier. If words are too difficult or too technical, the receiver may not understand them; if words are too simple, the reader could become bored or be insulted. In either case, the message falls short of meeting its goals . . . Word choice is also a consideration when communicating with receivers for whom English is not the primary language [who] may not be familiar with colloquial English.»

(From «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

Word Selection for Composition

Word choice is an essential element for any student learning to write effectively. Appropriate word choice allows students to display their knowledge, not just about English, but with regard to any given field of study from science and mathematics to civics and history.

Fast Facts: Six Principles of Word Choice for Composition

- Choose understandable words.

- Use specific, precise words.

- Choose strong words.

- Emphasize positive words.

- Avoid overused words.

- Avoid obsolete words.

(Adapted from «Business Communication, 8th Edition,» by A.C. Krizan, Patricia Merrier, Joyce P. Logan, and Karen Williams. South-Western Cengage, 2011)

The challenge for teachers of composition is to help students understand the reasoning behind the specific word choices they’ve made and then letting the students know whether or not those choices work. Simply telling a student something doesn’t make sense or is awkwardly phrased won’t help that student become a better writer. If a student’s word choice is weak, inaccurate, or clichéd, a good teacher will not only explain how they went wrong but ask the student to rethink his or her choices based on the given feedback.

Word Choice for Literature

Arguably, choosing effective words when writing literature is more complicated than choosing words for composition writing. First, a writer must consider the constraints for the chosen discipline in which they are writing. Since literary pursuits as such as poetry and fiction can be broken down into an almost endless variety of niches, genres, and subgenres, this alone can be daunting. In addition, writers must also be able to distinguish themselves from other writers by selecting a vocabulary that creates and sustains a style that is authentic to their own voice.

When writing for a literary audience, individual taste is yet another huge determining factor with regard to which writer a reader considers a «good» and who they may find intolerable. That’s because «good» is subjective. For example, William Faulker and Ernest Hemmingway were both considered giants of 20th-century American literature, and yet their styles of writing could not be more different. Someone who adores Faulkner’s languorous stream-of-consciousness style may disdain Hemmingway’s spare, staccato, unembellished prose, and vice versa.

All strong writers have something in common: they understand the value of word choice in writing. Strong word choice uses vocabulary and language to maximum effect, creating clear moods and images and making your stories and poems more powerful and vivid.

The meaning of “word choice” may seem self-explanatory, but to truly transform your style and writing, we need to dissect the elements of choosing the right word. This article will explore what word choice is, and offer some examples of effective word choice, before giving you 5 word choice exercises to try for yourself.

Word Choice Definition: The Four Elements of Word Choice

The definition of word choice extends far beyond the simplicity of “choosing the right words.” Choosing the right word takes into consideration many different factors, and finding the word that packs the most punch requires both a great vocabulary and a great understanding of the nuances in English.

Choosing the right word involves the following four considerations, with word choice examples.

1. Meaning

Words can be chosen for one of two meanings: the denotative meaning or the connotative meaning. Denotation refers to the word’s basic, literal dictionary definition and usage. By contrast, connotation refers to how the word is being used in its given context: which of that word’s many uses, associations, and connections are being employed.

A word’s denotative meaning is its literal dictionary definition, while its connotative meaning is the web of uses and associations it carries in context.

We play with denotations and connotations all the time in colloquial English. As a simple example, when someone says “greaaaaaat” sarcastically, we know that what they’re referring to isn’t “great” at all. In context, the word “great” connotes its opposite: something so bad that calling it “great” is intentionally ridiculous. When we use words connotatively, we’re letting context drive the meaning of the sentence.

The rich web of connotations in language are crucial to all writing, and perhaps especially so to poetry, as in the following lines from Derek Walcott’s Nobel-prize-winning epic poem Omeros:

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

Sugar cane isn’t, literally, made of “feathered lances,” which would literally denote “long metal spears adorned with bird feathers”; but feathered connotes “branching out,” the way sugar cane does, and lances connotes something tall, straight, and pointy, as sugar cane is. Together, those two words create a powerfully true visual image of sugar cane—in addition to establishing the martial language (“spears,” “marching”) used elsewhere in the passage.

Whether in poetry or prose, strong word choice can unlock images, emotions, and more in the reader, and the associations and connotations that words bring with them play a crucial role in this.

2. Specificity

Use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description.

In the sprawling English language, one word can have dozens of synonyms. That’s why it’s important to use words that are both correct in meaning and specific in description. Words like “good,” “average,” and “awful” are far less descriptive and specific than words like “liberating” (not just good but good and freeing), “C student” (not just average but academically average), and “despicable” (not just awful but morally awful). These latter words pack more meaning than their blander counterparts.

Since more precise words give the reader added context, specificity also opens the door for more poetic opportunities. Take the short poem “[You Fit Into Me]” by Margaret Atwood.

You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

A fish hook

An open eye

The first stanza feels almost romantic until we read the second stanza. By clarifying her language, Atwood creates a simple yet highly emotive duality.

This is also why writers like Stephen King advocate against the use of adverbs (adjectives that modify verbs or other adjectives, like “very”). If your language is precise, you don’t need adverbs to modify the verbs or adjectives, as those words are already doing enough work. Consider the following comparison:

Weak description with adverbs: He cooks quite badly; the food is almost always extremely overdone.

Strong description, no adverbs: He incinerates food.

Of course, non-specific words are sometimes the best word, too! These words are often colloquially used, so they’re great for writing description, writing through a first-person narrative, or for transitional passages of prose.

3. Audience

Good word choice takes the reader into consideration. You probably wouldn’t use words like “lugubrious” or “luculent” in a young adult novel, nor would you use words like “silly” or “wonky” in a legal document.

This is another way of saying that word choice conveys not only direct meaning, but also a web of associations and feelings that contribute to building the reader’s world. What world does the word “wonky” help build for your reader, and what world does the word “seditious” help build? Depending on the overall environment you’re working to create for the reader, either word could be perfect—or way out of place.

4. Style

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing.

Consider your word choice to be the fingerprint of your writing. Every writer uses words differently, and as those words come to form poems, stories, and books, your unique grasp on the English language will be recognizable by all your readers.

Style isn’t something you can point to, but rather a way of describing how a writer writes. Ernest Hemingway, for example, is known for his terse, no-nonsense, to-the-point styles of description. Virginia Woolf, by contrast, is known for writing that’s poetic, intense, and melodramatic, and James Joyce for his lofty, superfluous writing style.

Here’s a paragraph from Joyce:

Had Pyrrhus not fallen by a beldam’s hand in Argos or Julius Caesar not been knifed to death. They are not to be thought away. Time has branded them and fettered they are lodged in the room of the infinite possibilities they have ousted.

And here’s one from Hemingway:

Bill had gone into the bar. He was standing talking with Brett, who was sitting on a high stool, her legs crossed. She had no stockings on.

Style is best observed and developed through a portfolio of writing. As you write more and form an identity as a writer, the bits of style in your writing will form constellations.

Check Out Our Online Writing Courses!

The Literary Essay

with Jonathan J.G. McClure

April 12th, 2023

Explore the literary essay — from the conventional to the experimental, the journalistic to essays in verse — while writing and workshopping your own.

Getting Started Marketing Your Work

with Gloria Kempton

April 12th, 2023

Solve the mystery of marketing and get your work out there in front of readers in this 4-week online class taught by Instructor Gloria Kempton.

Word Choice in Writing: The Importance of Verbs

Before we offer some word choice exercises to expand your writing horizons, we first want to mention the importance of verbs. Verbs, as you may recall, are the “action” of the sentence—they describe what the subject of the sentence actually does. Unless you are intentionally breaking grammar rules, all sentences must have a verb, otherwise they don’t communicate much to the reader.

Because verbs are the most important part of the sentence, they are something you must focus on when expanding the reaches of your word choice. Verbs are the most widely variegated units of language; the more “things” you can do in the world, the more verbs there are to describe them, making them great vehicles for both figurative language and vivid description.

Consider the following three sentences:

- The road runs through the hills.

- The road curves through the hills.

- The road meanders through the hills.

Which sentence is the most descriptive? Though each of them has the same subject, object, and number of words, the third sentence creates the clearest image. The reader can visualize a road curving left and right through a hilly terrain, whereas the first two sentences require more thought to see clearly.

Finally, this resource on verb usage does a great job at highlighting how to invent and expand your verb choice.

Word Choice in Writing: Economy and Concision

Strong word choice means that every word you write packs a punch. As we’ve seen with adverbs above, you may find that your writing becomes more concise and economical—delivering more impact per word. Above all, you may find that you omit needless words.

Omit needless words is, in fact, a general order issued by Strunk and White in their classic Elements of Style. As they explain it:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

It’s worth repeating that this doesn’t mean your writing becomes clipped or terse, but simply that “every word tell.” As our word choice improves—as we omit needless words and express ourselves more precisely—our writing becomes richer, whether we write in long or short sentences.

As an example, here’s the opening sentence of a random personal essay from a high school test preparation handbook:

The world is filled with a numerous amount of student athletes that could somewhere down the road have a bright future.

Most words in this sentence are needless. It could be edited down to:

Many student athletes could have a bright future.

Now let’s take some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Can you remove a single word without sacrificing an enormous richness of meaning?

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In strong writing, every single word is chosen for maximum impact. This is the true meaning of concise or economical writing.

5 Word Choice Exercises to Sharpen Your Writing

With our word choice definition in mind, as well as our discussions of verb use and concision, let’s explore the following exercises to put theory into practice. As you play around with words in the following word choice exercises, be sure to consider meaning, specificity, style, and (if applicable) audience.

1. Build Moods With Word Choice

Writers fine-tune their words because the right vocabulary will build lush, emotive worlds. As you expand your word choice and consider the weight of each word, focus on targeting precise emotions in your descriptions and figurative language.

This kind of point is best illustrated through word choice examples. An example of magnificent language is the poem “In Defense of Small Towns” by Oliver de la Paz. The poem’s ambivalent feelings toward small hometowns presents itself through the mood of the writing.

The poem is filled with tense descriptions, like “animal deaths and toughened hay” and “breeches speared with oil and diesel,” which present the small town as stoic and masculine. This, reinforced by the terse stanzas and the rare “chances for forgiveness,” offers us a bleak view of the town; yet it’s still a town where everything is important, from “the outline of every leaf” to the weightless flight of cattail seeds.

The writing’s terse, heavy mood exists because of the poem’s juxtaposition of masculine and feminine words. The challenge of building a mood produces this poem’s gravity and sincerity.

Try to write a poem, or even a sentence, that evokes a particular mood through words that bring that word to mind. Here’s an example:

- What mood do you want to evoke? flighty

- What words feel like they evoke that mood? not sure, whatever, maybe, perhaps, tomorrow, sometimes, sigh

- Try it in a sentence: “Maybe tomorrow we could see about looking at the lab results.” She sighed. “Perhaps.”

2. Invent New Words and Terms

A common question writers ask is, What is one way to revise for word choice? One trick to try is to make up new language in your revisions.

If you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

In the same way that unusual verbs highlight the action and style of your story, inventing words that don’t exist can also create powerful diction. Of course, your writing shouldn’t overflow with made-up words and pretentious portmanteaus, but if you create language at a crucial moment, you might be able to highlight something that our current language can’t.

A great example of an invented word is the phrase “wine-dark sea.” Understanding this invention requires a bit of history; in short, Homer describes the sea as “οἶνοψ πόντος”, or “wine-faced.” “Wine-dark,” then, is a poetic translation, a kind of kenning for the sea’s mystery.

Why “wine-dark” specifically? Perhaps because, like the sea, wine changes us; maybe the eyes of the sea are dark, as eyes often darken with wine; perhaps the sea is like a face, an inversion, a reflection of the self. In its endlessness, we see what we normally cannot.

Thus, “wine-dark” is a poetic combination of words that leads to intensive literary analysis. For a less historical example, I’m currently working on my poetry thesis, with pop culture monsters being the central theme of the poems. In one poem, I describe love as being “frankensteined.” By using this monstrous made-up verb in place of “stitched,” the poem’s attitude toward love is much clearer.

Try inventing a word or phrase whose meaning will be as clear to the reader as “wine-dark sea.” Here’s an example:

- What do you want to describe? feeling sorry for yourself because you’ve been stressed out for a long time

- What are some words that this feeling brings up? self-pity, sympathy, sadness, stress, compassion, busyness, love, anxiety, pity party, feeling sorry for yourself

- What are some fun ways to combine these words? sadxiety, stresslove

- Try it in a sentence: As all-nighter wore on, my anxiety softened into sadxiety: still edgy, but soft in the middle.

3. Only Use Words of Certain Etymologies

One of the reasons that the English language is so large and inconsistent is that it borrows words from every language. When you dig back into the history of loanwords, the English language is incredibly interesting!

(For example, many of our legal terms, such as judge, jury, and plaintiff, come from French. When the Normans [old French-speakers from Northern France] conquered England, their language became the language of power and nobility, so we retained many of our legal terms from when the French ruled the British Isles.)

Nerdy linguistics aside, etymologies also make for a fun word choice exercise. Try forcing yourself to write a poem or a story only using words of certain etymologies and avoiding others. For example, if you’re only allowed to use nouns and verbs that we borrowed from the French, then you can’t use Anglo-Saxon nouns like “cow,” “swine,” or “chicken,” but you can use French loanwords like “beef,” “pork,” and “poultry.”

Experiment with word etymologies and see how they affect the mood of your writing. You might find this to be an impactful facet of your word choice. You can Google “__ etymology” for any word to see its origin, and “__ synonym” to see synonyms.

Try writing a sentence only with roots from a single origin. (You can ignore common words like “the,” “a,” “of,” and so on.)

- What do you want to write? The apple rolled off the table.

- Try a first etymology: German: The apple wobbled off the bench.

- Try a second: Latin: The russet fruit rolled off the table.

4. Write in E-Prime

E-Prime Writing describes a writing style where you only write using the active voice. By eschewing all forms of the verb “to be”—using words such as “is,” “am,” “are,” “was,” and other “being” verbs—your writing should feel more clear, active, and precise!

E-Prime not only removes the passive voice (“The bottle was picked up by James”), but it gets at the reality that many sentences using to be are weakly constructed, even if they’re technically in the active voice.

Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

Try writing a paragraph in E-Prime:

- What do you want to write? Of course, E-Prime writing isn’t the best type of writing for every project. The above paragraph is written in E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would be tricky. The intent of E-Prime writing is to make all of your subjects active and to make your verbs more impactful. While this is a fun word choice exercise and a great way to create memorable language, it probably isn’t sustainable for a long writing project.

- Converted to E-Prime: Of course, E-Prime writing won’t best suit every project. The above paragraph uses E-Prime, but stretching it out across this entire article would carry challenges. E-Prime writing endeavors to make all of your subjects active, and your verbs more impactful. While this word choice exercise can bring enjoyment and create memorable language, you probably can’t sustain it over a long writing project.

5. Write Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry, also known as Found Poetry, is a visual creative writing project. You take a page from a published source and create a poem by blacking out other words until your circled words create a new poem. The challenge is that you’re limited to the words on a page, so you need a charged use of both space and language to make a compelling blackout poem.

Blackout poetry bottoms out our list of great word choice exercises because it forces you to consider the elements of word choice. With blackout poems, certain words might be read connotatively rather than denotatively, or you might change the meaning and specificity of a word by using other words nearby. Language is at its most fluid and interpretive in blackout poems!

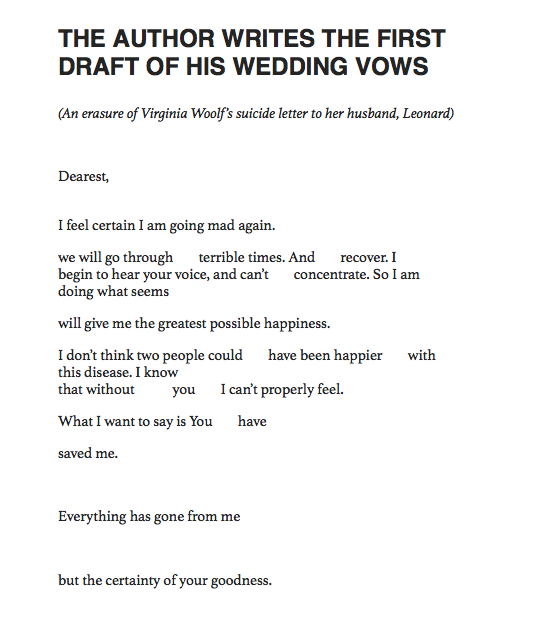

For a great word choice example using blackout poetry, read “The Author Writes the First Draft of His Wedding Vows” by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib. Here it is visually:

Source: https://decreation.tumblr.com/post/620222983530807296/from-the-crown-aint-worth-much-by-hanif

Pick a favorite poem of your own and make something completely new out of it using blackout poetry.

How to Expand Your Vocabulary

Vocabulary is a last topic in word choice. The more words in your arsenal, the better. Great word choice doesn’t rely on a large vocabulary, but knowing more words will always help! So, how do you expand your vocabulary?

The simplest way to expand your vocabulary is by reading.

The simplest answer, and the one you’ll hear the most often, is by reading. The more literature you consume, the more examples you’ll see of great words using the four elements of word choice.

Of course, there are also some great programs for expanding your vocabulary as well. If you’re looking to use words like “lachrymose” in a sentence, take a look at the following vocab builders:

- Dictionary.com’s Word-of-the-Day

- Vocabulary.com Games

- Merriam Webster’s Vocab Quizzes

Improve Your Word Choice With Writers.com’s Online Writing Courses

Looking for more writing exercises? Need more help choosing the right words? The instructors at Writers.com are masters of the craft. Take a look at our upcoming course offerings and join our community!

Definitions of choice of words

-

noun

the manner in which something is expressed in words

DISCLAIMER: These example sentences appear in various news sources and books to reflect the usage of the word ‘choice of words’.

Views expressed in the examples do not represent the opinion of Vocabulary.com or its editors.

Send us feedback

EDITOR’S CHOICE

Look up choice of words for the last time

Close your vocabulary gaps with personalized learning that focuses on teaching the

words you need to know.

Sign up now (it’s free!)

Whether you’re a teacher or a learner, Vocabulary.com can put you or your class on the path to systematic vocabulary improvement.

Get started

Also found in: Thesaurus.

ThesaurusAntonymsRelated WordsSynonymsLegend:

Based on WordNet 3.0, Farlex clipart collection. © 2003-2012 Princeton University, Farlex Inc.

Mentioned in

?

- accent

- by word of mouth

- cacology

- choice

- diction

- expression

- formulation

- gender

- in a word

- judicious

- judiciously

- judiciousness

- language

- mot juste

- parlance

- phrase

- phraseology

- phrasing

- so to speak

References in classic literature

?

She was only fair in Latin or French grammar, but when it came to translation, her freedom, her choice of words, and her sympathetic understanding of the spirit of the text made her the delight of her teachers and the despair of her rivals.

His manner became palpably anxious; and his choice of words was more carefully selected than ever.

«About a week after you had gone away ma’am,» she said, with extreme severity of manner, and with excessive carefulness in her choice of words, «the Person you mention had the impudence to send a letter to you.

His sudden composure, and his sudden nicety in the choice of words, tried her courage far more severely than it had been tried by his violence of the moment before.

Mr Verloc, thinking of Mr Vladimir, did not hesitate in the choice of words.

‘whom you are pleased to call, in a choice of words in which I am not experienced, my brother’s instruments?’

Do not make such vague general statements as ‘He has good choice of words,’ but cite a list of characteristic words or skilful expressions.

No; but also hunters, farmers, grooms, and butchers, though they express their affection in their choice of life and not in their choice of words. The writer wonders what the coachman or the hunter values in riding, in horses and dogs.

Dela Rosa, a former national police chief, said his earlier remark was only a case of wrong choice of words.

Summary: The choice of words in the tweet by Buckingham Palace (Twitter handle: @RoyalFamily) to announce the royal arrival was nothing short of majestic.

Summary: California [USA], May 2 (ANI): Google has built a new AI that uses your selfie and combines it with your choice of words to create your unique portrait, overlaid with poetry.

In a statement that emphasises that IK’s choice of words was unbecoming of a prime minister, Bilawal appears to be stooping to the same low standards to get back at him.

Dictionary browser

?

- ▲

- chocolate pudding

- chocolate root

- chocolate sauce

- chocolate soldier

- chocolate syrup

- chocolate tree

- chocolate truffle

- chocolate-box

- chocolate-brown

- chocolate-colored

- chocolate-coloured

- chocolatier

- Chocorua Mount

- chocs

- Choctaw

- Choctawhatchee River

- Choctaws

- Chode

- Choeronycteris

- Choeronycteris mexicana

- chog

- Chogset

- Chogyal

- choice

- choice morsel

- choice of words

- choiceful

- choicely

- choiceness

- Choices

- choicest

- choir

- choir loft

- Choir organ

- choir school

- Choir screen

- Choir service

- choirboy

- choirgirl

- choirman

- choirmaster

- choir-screen

- choirstall

- Choiseul

- choke

- choke back

- choke chain

- choke coil

- choke collar

- Choke damp

- choke down

- ▼

Full browser

?

- ▲

- Choice axiom

- Choice Band

- Choice Based Art Education

- Choice Based Credit System

- Choice Based Lettings

- choice between (of) two evils, a

- choice between 2 evils

- choice between two evils

- choice bit of calico

- choice chamber

- Choice Dividend

- Choice for Enlightened Living Foundation

- Choice In Dying

- Choice in Supports for Independent Living

- Choice Is Yours

- Choice market

- choice morsel

- choice morsel

- choice of 2 evils

- Choice of Arm

- Choice of Hercules

- Choice of Hercules

- Choice of Hercules

- Choice of law clause

- choice of path of placement

- choice of path of placement

- choice of path of placement

- choice of path of placement

- choice of path of placement

- choice of two evils

- choice of words

- Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Act

- Choice Quality Review Organizations

- Choice Reaction Time Test

- Choice Relation Framework

- Choice Relation Table

- Choice voting

- Choice, Ask, Recommend, Encourage

- Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis

- Choice-Based Conjoint Model

- Choice-Based Conjoint/Hierarchical Bayes

- Choice-Based Credit System

- Choice-Based Lettings Scheme

- Choice-of-law clause

- Choiceful

- choicely

- choicely

- choicely

- choicely

- choicely

- choicely

- choiceness

- choiceness

- choiceness

- choiceness

- choiceness

- choiceness

- choicer

- choicer

- choicer

- choicer

- ▼