Word-meaning is made up of

various components described as meaning types. There are several

types of meaning.

Lexical

meaning is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its

forms and distributions.

The most significant features of the lexical meaning of the word are:

the word’s interrelationship with the denoted objects and phenomena

of the world; the word’s interrelationship with the conceptual

matter that appears in people’s mind on perceiving a language unit;

the word’s interrelationship with the other words in a context so

lexical meaning possesses several aspects.

According

to D.

Crystal,

lexical

items are viewed upon as signs within the sign system of the language

vocabulary

so

signification

is that aspect of the word’s meaning which stresses the sign

function of the word, in other words, it is the relation between sign

and thing or sign and concept.

Denotation

involves the relationship between a linguistic unit (a lexical item)

and the non-linguistic entities to which it refers. Denotational

meaning is the part of lexical meaning that makes communication

possible. Denotational

meaning conceptualises

and classifies our experience and names objects so that our knowledge

of reality is embodied in words having essentially the same meaning

for all speakers of the language. Denotational meaning can be

segmented into semes

(seme is a minimal unit of the matter).

This procedure is known as componential analysis which seeks to set

up minimal semantic oppositions in order to arrive at meaning

differentiating features.

When words are used in their

factual direct meanings denotation and signification coincide

Connotational

meaning comprises the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the

word that are closely connected and even interdependent. In

other words, connotation is supplementary emotive, evaluative,

expressive and stylistic shade which is added to the word’s

denotational meaning and which serves to express the emotional

content of the word — that is its capacity to evoke or directly

express emotion.

The

list and specification of connotational meanings varies with

different linguistic schools and individual scholars and includes

such entries as pragmatic

(directed at the perlocutionary effect of utterance), associative

(connected, through individual psychological or linguistic

associations, with related and non-related notions), ideological,

or conceptual (revealing

political, social, ideological preferences of the user), evaluative

(stating the value of the indicated notion), emotive

(revealing the emotional layer of cognition and perception),

expressive

(aiming at creating the image of the object in question), stylistic

(indicating «the register», or the situation of the

communication).

Let’s

illustrate four

main components of connotational meaning: emotive,

evaluative, expressive (intensifying), stylistic.

Emotive

meaning or charge is associated with emotions.

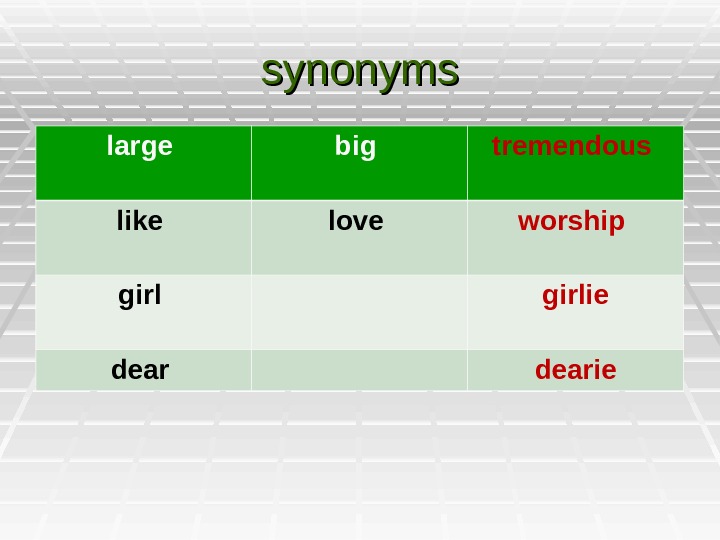

In the following sets of words with the same denotational meaning to

like, to love, to worship; big, large, tremendous; girl, girlie;

dear, dearie — to

worship, tremendous, girlie, dearie

have

heavier emotive charge than others members of sets. We shouldn’t

confuse the emotive

charge

with emotive

implications:

what is thought and felt when the word hospital

is used by an architect who built it, a doctor or a nurse working

there, the invalid staying there after an operation.

Evaluative

meaning expresses approval or disapproval, e.g.,

magic

has

attractive connotation while its synonym witchcraft

has sinister accentuation.

Expressive

component serves to

emphasise

the subjective attitude to the content of the utterance or the person

addressed, e.g.,

magnificent,

splendid, superb

may be viewed as exaggerations.

Stylistically

words

can be subdivided into literary

(bookish), neutral and colloquial layers (parent

— father — dad).

Literary

words can be subdivided into general literary words (harmony,

calamity);

scientific terms; poetic words and archaisms (albeit

— although);

barbarisms and foreign words (bon

mot — a clever or witty saying, bouquet). The

colloquial words may be subdivided into common colloquial (dad);

slang (gag

for a joke);

professionalisms (lab); jargonisms (a

sucker — a person who is easily deceived);

vulgarisms (shut

up);

dialectical words (lass);

colloquial coinages (allrightnik).

The

above-mentioned meanings are classified as connotational not only

because they supply additional (and not the logical / denotational)

information, but also because, for the most part, they are observed

not all at once and not in all words either. Some of them are more

important for the act of communication than the others. Very often

they overlap (частично совпадают). So, all words

possessing an emotive meaning are also evaluative (rascal,

ducky),

though this rule is not reversed, as we can find non-emotive,

intellectual evaluation (good,

bad).

Also, almost all emotive words are also expressive, while there are

hundreds of expressive words which cannot be treated as emotive

(take, for example the so-called expressive verbs, which not only

denote some action or process but also create their image, as in to

gulp — to swallow in big lumps, in a hurry; to sprint — to run fast).

The number, importance and the

overlapping character of connotational meanings incorporated into the

semantic structure of a word, are brought forth by the context, i. e.

a concrete speech act that identifies and actualizes each one. More

than that: each context does not only specify the existing semantic

(both denotational and connotational) possibilities of a word, but

also is capable of adding new ones, or deviating rather considerably

from what is registered in the dictionary. Because of that all

contextual meanings of a word can never be exhausted or

comprehensively enumerated.

Grammatical

meaning is the component of meaning recurrent in identical forms of

individual forms of different words.

On the one hand, grammatical meaning unites words in such large

groups as parts of speech, e.g., the grammatical meaning of

substuntivity

for

nouns, the grammatical meaning of process

for

verbs, and so on. On the other hand, it is the property of identical

sets of word-forms. It may be defined as the indication in certain

grammatical categories, e.g., such word-forms as tables,

books

manifest the grammatical meaning of plurality. Grammatical meaning

may also de defined as the realization of a concept or a notion by

means of a definite language system, e.g., the word forms go,

goes, went, gone, going

express one and the same concept, that of the process of movement,

which is restricted in their lexical meaning. It follows that by

lexical meaning we understand the meaning proper to the linguistic

unit in all its forms, by grammatical meaning we understand the

meaning proper to the sets of word-forms common to all words of a

certain class, e.g., the word takes

has the same lexical meaning as took,

taken,

but its grammatical meaning is that which is shared by works,

stands;

the same is true about grammatical meaning of the following examples:

boys, girls; boy’s, girl’s; helped, met; better, smaller.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Скачать материал

Скачать материал

- Сейчас обучается 396 человек из 63 регионов

Описание презентации по отдельным слайдам:

-

1 слайд

Aspects of Lexical Meaning

Lecture -

2 слайд

ASPECTS OF LEXICAL MEANING

THE DENOTATIONAL ASPECT

THE CONNOTATIONAL ASPECT

THE PRAGMATIC ASPECT

COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS -

3 слайд

1. THE DENOTATIONAL ASPECT

The denotational aspect of lexical meaning is the part of lexical meaning which establishes correlation between the name and the object, phenomenon, process or characteristic feature of concrete reality (or thought), which is denoted by the given word.

e.g. booklet — ‘a small thin book that gives information about something’ -

4 слайд

Through the denotational aspect of meaning the bulk of information is conveyed in the process of communication.

The denotational aspect of lexical meaning:

expresses the notional content of a word.

is the component of the lexical meaning that makes communication possible. -

5 слайд

2. THE CONNOTATIONAL ASPECT

The connotational aspect of lexical meaning is the part of meaning which reflects the attitude of the speaker towards what he speaks about. Connotation conveys additional information in the process of communication.

-

6 слайд

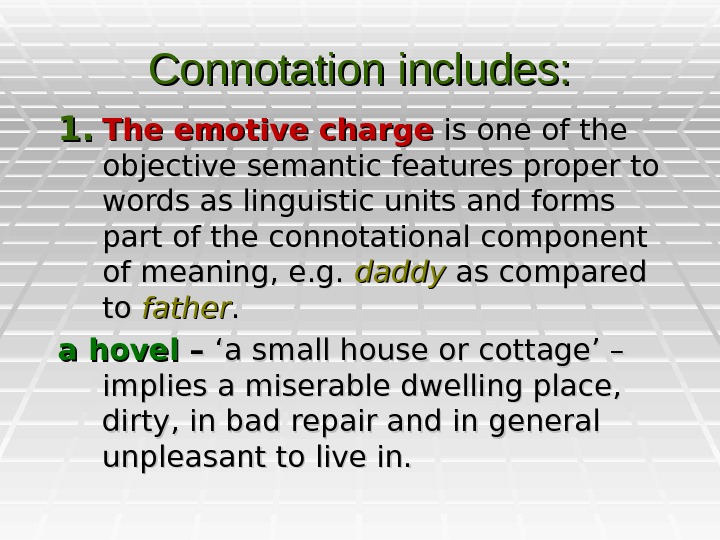

Connotation includes:

The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotational component of meaning, e.g. daddy as compared to father.

a hovel – ‘a small house or cottage’ – implies a miserable dwelling place, dirty, in bad repair and in general unpleasant to live in. -

-

8 слайд

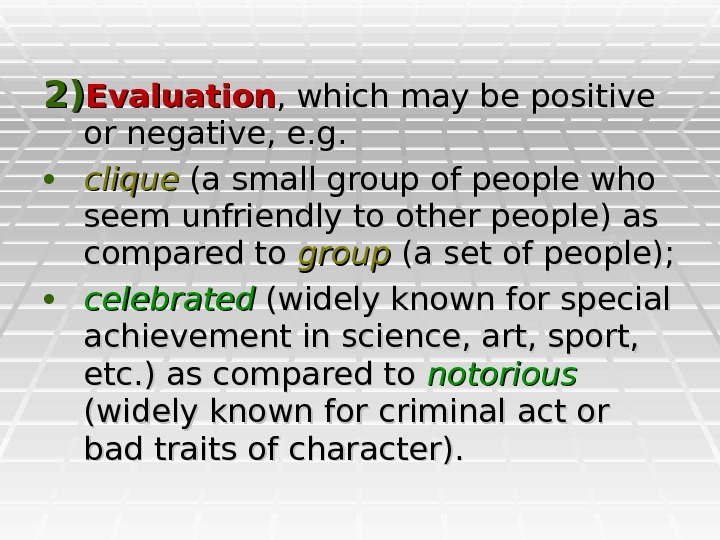

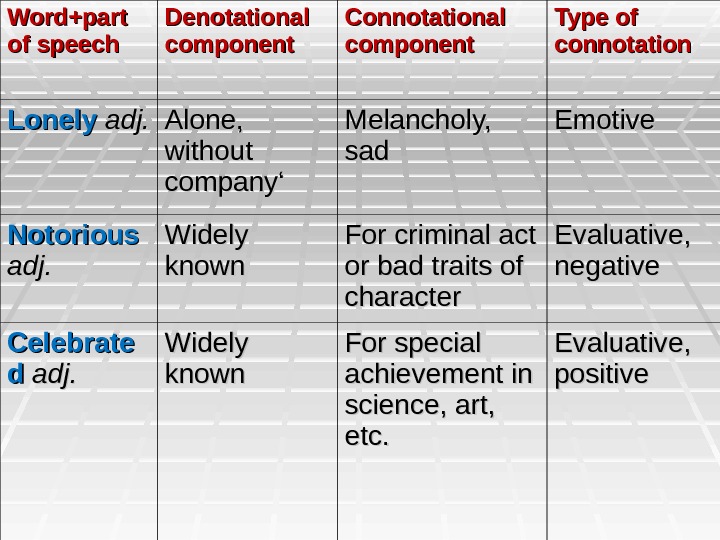

Evaluation, which may be positive or negative, e.g.

clique (a small group of people who seem unfriendly to other people) as compared to group (a set of people);

celebrated (widely known for special achievement in science, art, sport, etc.) as compared to notorious (widely known for criminal act or bad traits of character). -

9 слайд

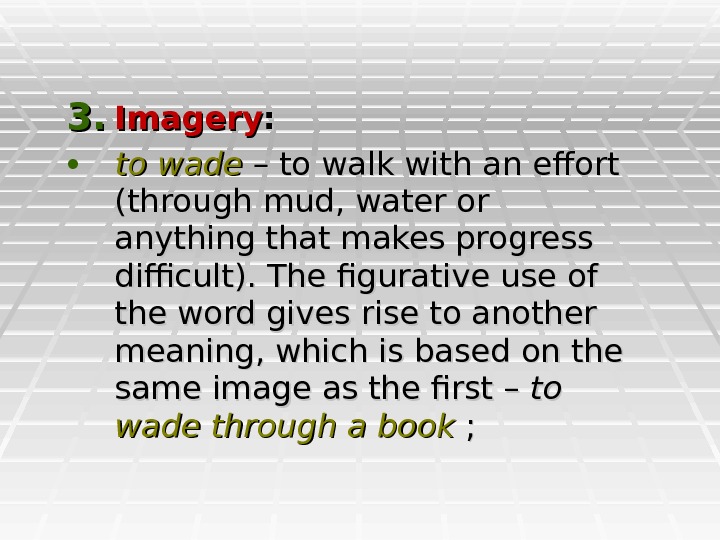

Imagery:

to wade – to walk with an effort (through mud, water or anything that makes progress difficult). The figurative use of the word gives rise to another meaning, which is based on the same image as the first – to wade through a book ; -

10 слайд

intensity/expressiveness, e.g. to adore – to worship – to love – to like;

connotation of cause, duration etc. -

-

-

-

14 слайд

Thus, a meaning can have two or more connotational components.

The given examples present only a few: emotive, evaluative connotations, and also connotations of duration and of cause. -

15 слайд

3. Examples of different types of Connotation

I. The connotation of degree or intensity

to surprise — to astonish — to amaze — to astound;

to satisfy — to please — to content — to gratify — to delight — to exalt;

to shout — to yell — to bellow — to roar; to like — to admire — to love — to adore — to worship -

16 слайд

II. Connotation of duration

to stare — to glare — to gaze — to glance — to peep — to peer;

to flash (brief) — to blaze (lasting);

to shudder (brief) — to shiver (lasting);

to say (brief) — to speak, to talk (lasting). -

17 слайд

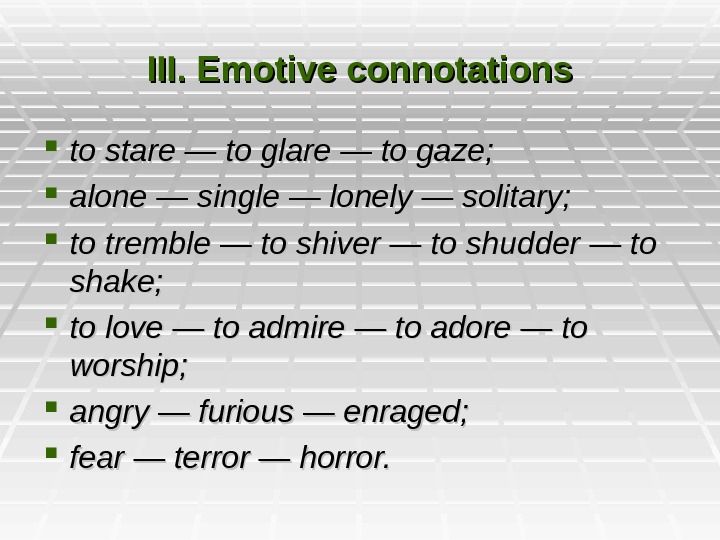

III. Emotive connotations

to stare — to glare — to gaze;

alone — single — lonely — solitary;

to tremble — to shiver — to shudder — to shake;

to love — to admire — to adore — to worship;

angry — furious — enraged;

fear — terror — horror. -

18 слайд

IV. The evaluative connotation

well-known — famous — notorious — celebrated;

to produce — to create — to manufacture — to fabricate;

to sparkle — to glitter;

A.His (her) eyes sparkled with amusement, merriment, good humour, high spirits, happiness, etc. (positive emotions).

B.His (her) eyes glittered with anger, rage, hatred,

malice, etc. (negative emotions). -

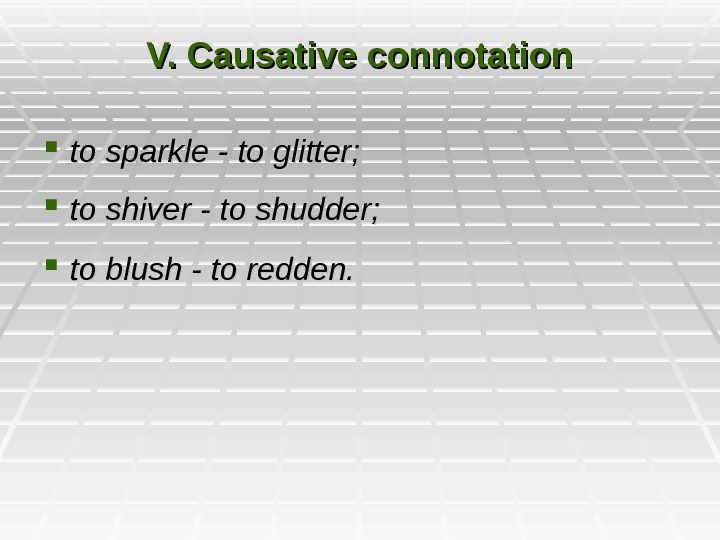

19 слайд

V. Causative connotation

to sparkle — to glitter;to shiver — to shudder;

to blush — to redden.

-

20 слайд

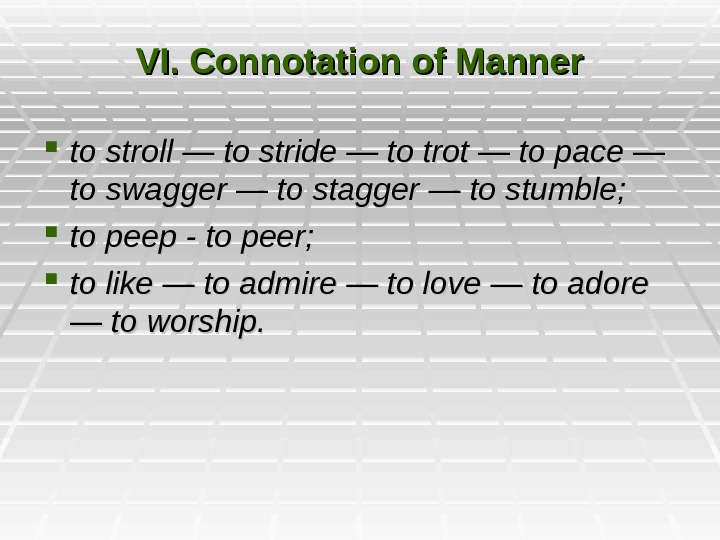

VI. Connotation of Manner

to stroll — to stride — to trot — to pace — to swagger — to stagger — to stumble;

to peep — to peer;

to like — to admire — to love — to adore — to worship. -

21 слайд

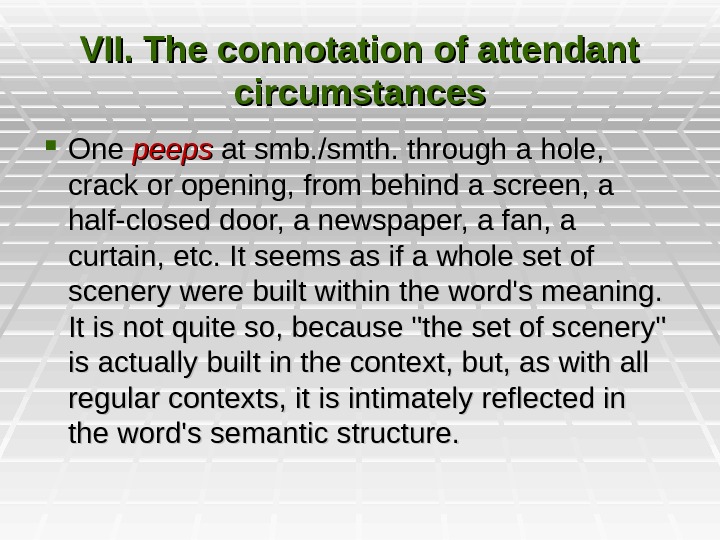

VII. The connotation of attendant circumstances

One peeps at smb./smth. through a hole, crack or opening, from behind a screen, a half-closed door, a newspaper, a fan, a curtain, etc. It seems as if a whole set of scenery were built within the word’s meaning. It is not quite so, because «the set of scenery» is actually built in the context, but, as with all regular contexts, it is intimately reflected in the word’s semantic structure. -

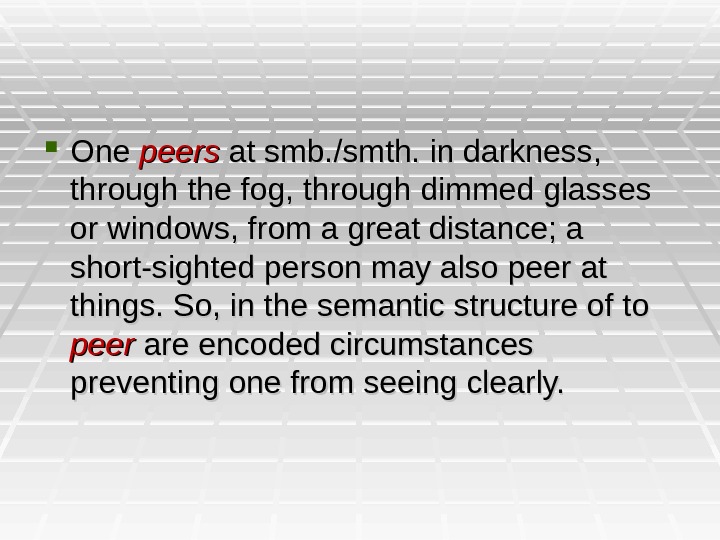

22 слайд

One peers at smb./smth. in darkness, through the fog, through dimmed glasses or windows, from a great distance; a short-sighted person may also peer at things. So, in the semantic structure of to peer are encoded circumstances preventing one from seeing clearly.

-

23 слайд

VII. Connotation of attendant features

Pretty – handsome – beautiful;

special types of human beauty:

beautiful is mostly associated with classical features and a perfect figure;

handsome with a tall stature, a certain robustness and fine proportions,

pretty with small delicate features and a fresh complexion. -

24 слайд

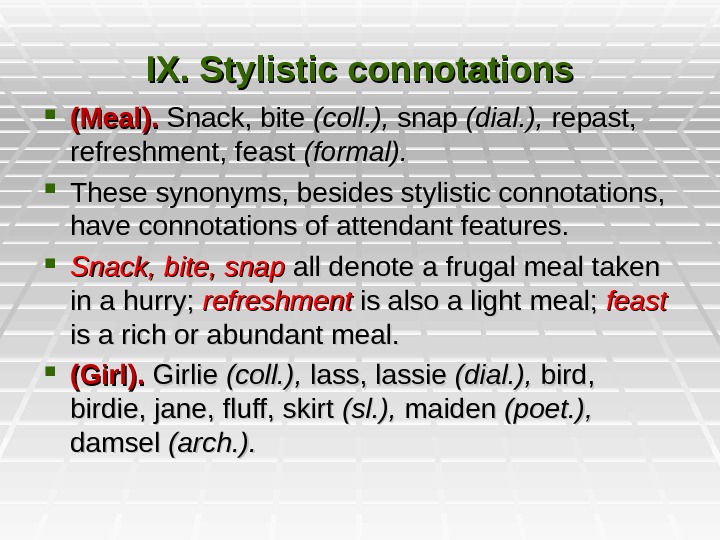

IX. Stylistic connotations

(Meal). Snack, bite (coll.), snap (dial.), repast, refreshment, feast (formal).

These synonyms, besides stylistic connotations, have connotations of attendant features.

Snack, bite, snap all denote a frugal meal taken in a hurry; refreshment is also a light meal; feast is a rich or abundant meal.

(Girl). Girlie (coll.), lass, lassie (dial.), bird, birdie, jane, fluff, skirt (sl.), maiden (poet.), damsel (arch.). -

25 слайд

Anecdote

J a n e: Would you be insulted if that good-looking stranger offered you some champagne?

J o a n: Yes, but I’d probably swallow the insult. -

26 слайд

3. THE PRAGMATIC ASPECT

The pragmatic aspect is the part of lexical meaning that conveys information on the situation of communication. Like the connotational aspect, the pragmatic aspect falls into four closely linked together subsections. -

27 слайд

1. Information on the ‘time and space’ relationship of the participants

Some information which specifies different parameters of communication may be conveyed not only with the help of grammatical means (tense forms, personal pronouns, etc), but through the meaning of the word.

E.g. come and go can indicate the location of the speaker who is usually taken as the zero point in the description of the situation of communication -

28 слайд

The time element is fixed indirectly. Indirect reference to time implies that the frequency of occurrence of words may change with time and in extreme cases words may be out of use or become obsolete.

E.g.the word behold – ‘take notice, see (smth unusual)’ as well as the noun beholder – ‘spectator’ are out of use now but were widely used in the 17th century. -

29 слайд

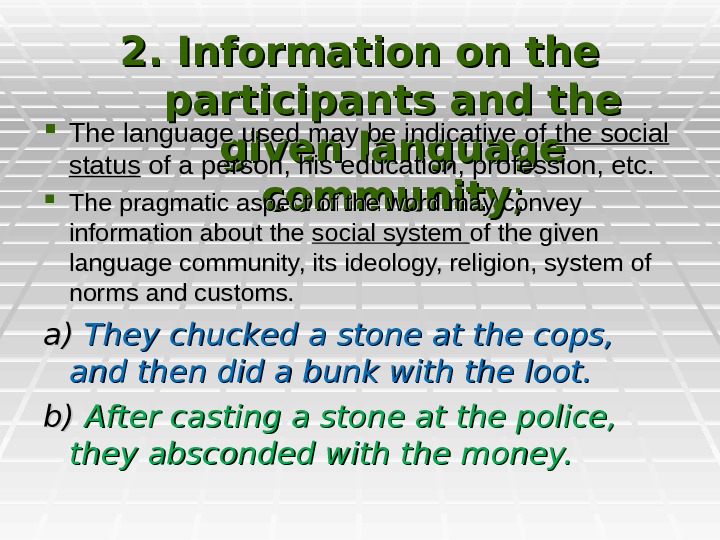

2. Information on the participants and the given language community;

The language used may be indicative of the social status of a person, his education, profession, etc.

The pragmatic aspect of the word may convey information about the social system of the given language community, its ideology, religion, system of norms and customs.

a) They chucked a stone at the cops, and then did a bunk with the loot.

b) After casting a stone at the police, they absconded with the money. -

30 слайд

3. Information on the tenor of discourse

The tenors of discourse reflect how the addresser (the speaker or the writer) interacts with the addressee (the listener or reader).

Tenors are based on social or family roles of the participants of communication.

1. Don’t interrupt when your mother is speaking (family roles).

2. There is an awful man in the front row, who butts in whenever you pause (social roles). -

31 слайд

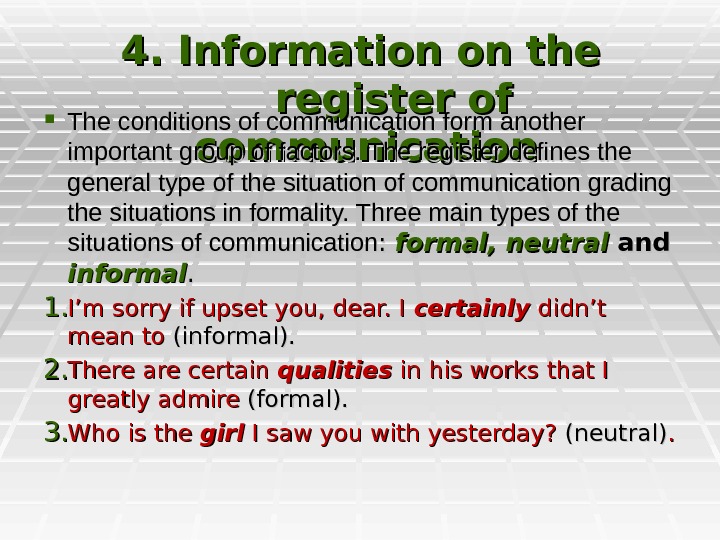

4. Information on the register of communication

The conditions of communication form another important group of factors. The register defines the general type of the situation of communication grading the situations in formality. Three main types of the situations of communication: formal, neutral and informal.

I’m sorry if upset you, dear. I certainly didn’t mean to (informal).

There are certain qualities in his works that I greatly admire (formal).

Who is the girl I saw you with yesterday? (neutral). -

32 слайд

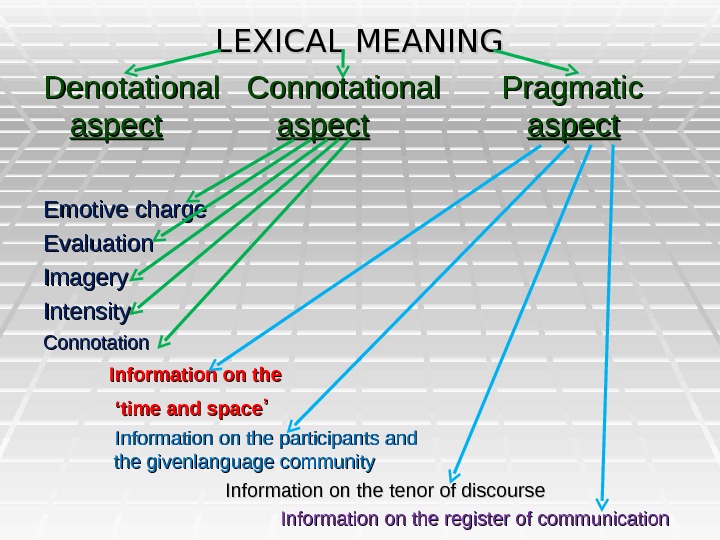

LEXICAL MEANING

Denotational Connotational Pragmatic aspect aspect aspectEmotive charge

Evaluation

Imagery

Intensity

Connotation

Information on the

‘time and space’

Information on the participants and

the givenlanguage community

Information on the tenor of discourse

Information on the register of communication -

33 слайд

IV. Componential analysis = semantic decomposition

rests upon the thesis that the sense of every lexeme can be analyzed in terms of a set of more general sense components or semantic features, some or all of which will be common to several different lexemes in the vocabulary.

-

34 слайд

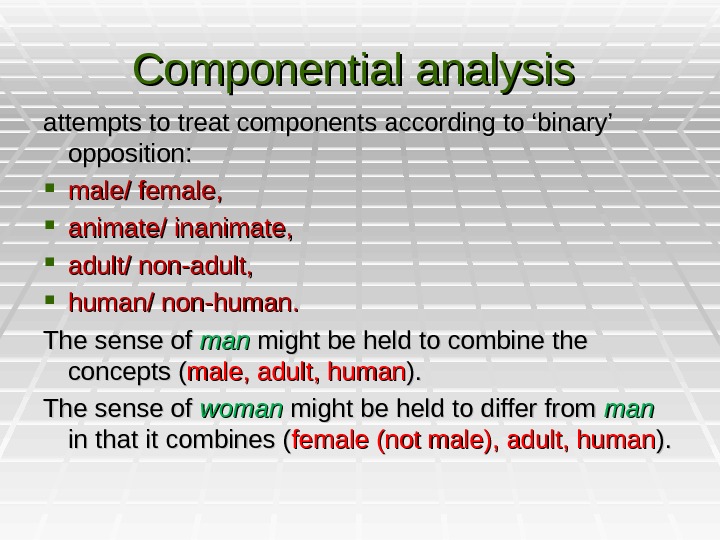

Componential analysis

attempts to treat components according to ‘binary’ opposition:

male/ female,

animate/ inanimate,

adult/ non-adult,

human/ non-human.

The sense of man might be held to combine the concepts (male, adult, human).

The sense of woman might be held to differ from man in that it combines (female (not male), adult, human). -

35 слайд

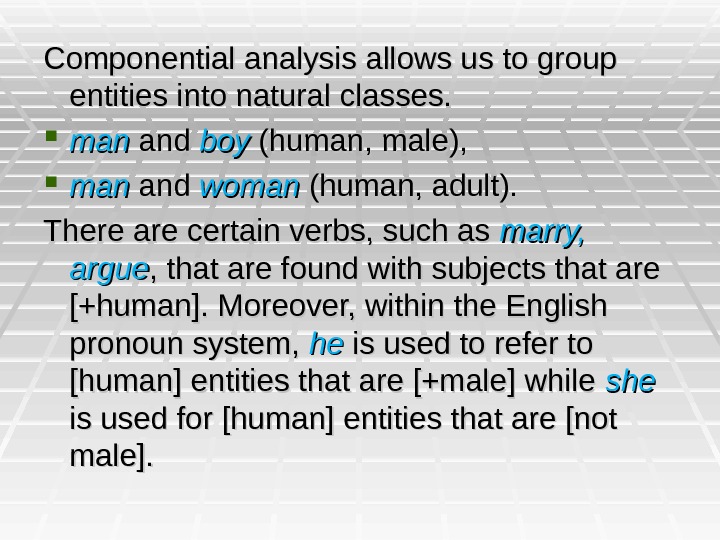

Componential analysis allows us to group entities into natural classes.

man and boy (human, male),

man and woman (human, adult).

There are certain verbs, such as marry, argue, that are found with subjects that are [+human]. Moreover, within the English pronoun system, he is used to refer to [human] entities that are [+male] while she is used for [human] entities that are [not male]. -

36 слайд

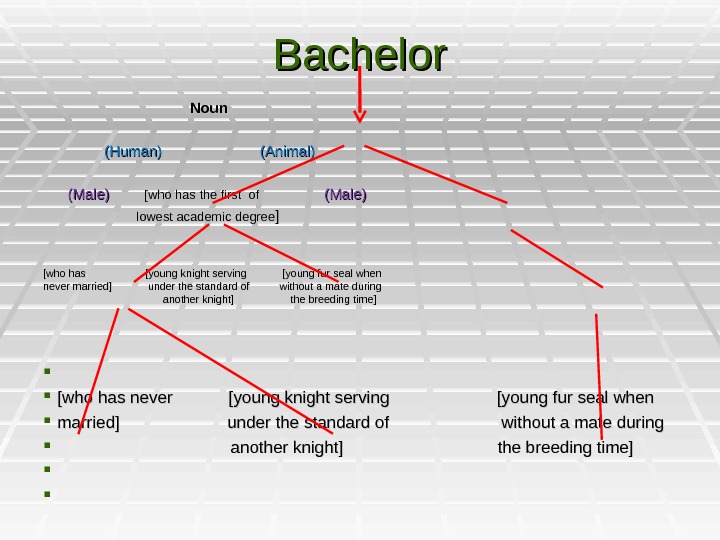

Componential analysis of the word ‘bachelor’

According to the dictionary it has 4 meanings:a man who has never married (холостяк);

a young knight (рыцарь);

someone with a first degree (бакалавр);

a young male unmated fur seal (морской котик) during the mating season. -

37 слайд

Bachelor

Noun

(Human) (Animal)

(Male) [who has the first of (Male)

lowest academic degree][who has [young knight serving [young fur seal when

never married] under the standard of without a mate during

another knight] the breeding time][who has never [young knight serving [young fur seal when

married] under the standard of without a mate during

another knight] the breeding time] -

38 слайд

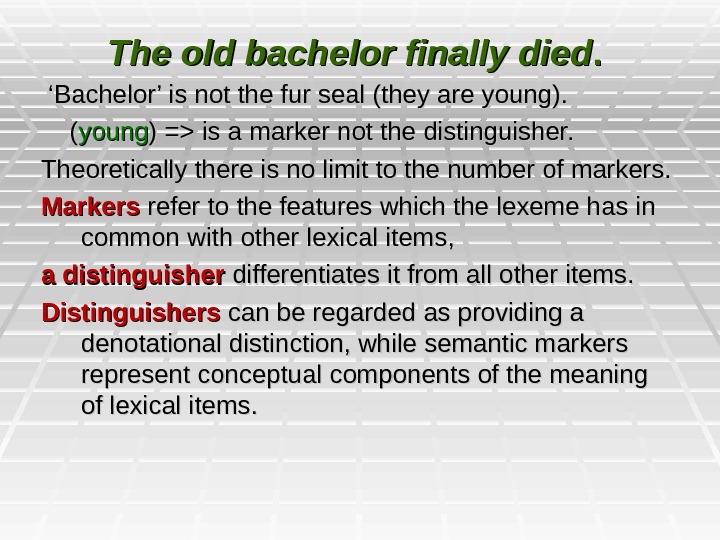

The old bachelor finally died.

‘Bachelor’ is not the fur seal (they are young).

(young) => is a marker not the distinguisher.

Theoretically there is no limit to the number of markers.

Markers refer to the features which the lexeme has in common with other lexical items,

a distinguisher differentiates it from all other items.

Distinguishers can be regarded as providing a denotational distinction, while semantic markers represent conceptual components of the meaning of lexical items. -

39 слайд

Componential analysis

gives its most important results in the study of verb meaning, it is an attractive way of handling semantic relations. It is currently combined with other linguistic procedures used for the investigation of meaning. -

40 слайд

References:

Зыкова И.В. Практический курс английской лексикологии. М.: Академия, 2006. – С.- 18-21.

Гинзбург Р.З. Лексикология английского языка. М.: Высшая школа, 1979. – С.- 20-22.

Бабич Н.Г. Лексикология английского языка. Екатеринбург-Москва. 2006. – С.- 61- 62.

Антрушина Г.Б., Афанасьева О.В., Морозова Н.Н. Лексикология английского языка. М.; Дрофа, 2006. С. — 136-142.

Найдите материал к любому уроку, указав свой предмет (категорию), класс, учебник и тему:

6 210 150 материалов в базе

- Выберите категорию:

- Выберите учебник и тему

- Выберите класс:

-

Тип материала:

-

Все материалы

-

Статьи

-

Научные работы

-

Видеоуроки

-

Презентации

-

Конспекты

-

Тесты

-

Рабочие программы

-

Другие методич. материалы

-

Найти материалы

Другие материалы

- 31.12.2020

- 3012

- 0

- 31.12.2020

- 3821

- 2

- 31.12.2020

- 4360

- 0

- 31.12.2020

- 5233

- 10

- 31.12.2020

- 4100

- 1

- 31.12.2020

- 3975

- 1

- 31.12.2020

- 5041

- 1

- 31.12.2020

- 4291

- 41

Вам будут интересны эти курсы:

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Основы местного самоуправления и муниципальной службы»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация и предоставление туристских услуг»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Организация практики студентов в соответствии с требованиями ФГОС юридических направлений подготовки»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Разработка бизнес-плана и анализ инвестиционных проектов»

-

Курс повышения квалификации «Источники финансов»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация системы менеджмента транспортных услуг в туризме»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Политология: взаимодействие с органами государственной власти и управления, негосударственными и международными организациями»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Теория и методика музейного дела и охраны исторических памятников»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Организация процесса страхования (перестрахования)»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Информационная поддержка бизнес-процессов в организации»

-

Курс профессиональной переподготовки «Гражданско-правовые дисциплины: теория и методика преподавания в образовательной организации»

- Размер: 782 Кб

- Количество слайдов: 40

SEMASIOLOGY1. ASPECTS OF LEXICAL MEANING1. Denotational Aspect.

2. Connotational Aspect. 3. Pragmatic Aspect.

1. DENOTATIONAL ASPECT

In the general framework of lexical meaning several aspects can

be singled out. They are: the denotational aspect, the

connotational aspect and the pragmatic aspect. The denotational

aspect of lexical meaning is the part of lexical meaning which

establishes correlation between the name and the object,

phenomenon, process or characteristic feature of concrete reality

(or thought as such), which is denoted by the given word. The term

denotational is derived from the English word to denote which means

be a sign of or stand as a name or symbol for. For instance, the

denotational meaning of booklet is a small thin book that gives

information about something. It is through the denotational aspect

of meaning that the bulk of information is conveyed in the process

of communication. The denotational aspect of lexical meaning

expresses the notional content of a word. The denotational aspect

is the component of the lexical meaning that makes communication

possible.

2. CONNOTATIONAL ASPECT

The connotational aspect of lexical meaning is the part of

meaning which reflects the attitude of the speaker towards what he

speaks about. Connotation conveys additional information in the

process of communication. Connotation includes:

the emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features

proper to words as linguistic units that forms part of the

connotational component of meaning, for example, daddy as compared

to father.

evaluation, which may be positive or negative, for instance,

clique (a small group of people who seem unfriendly to other

people) as compared to group (a set of people);

imagery, for example, to wade to walk with an effort (through

mud, water or anything that makes progress difficult). The

figurative use of the word gives rise to another meaning, which is

based on the same image as the first to wade through a book;

intensity / expressiveness, for instance, to adore to love;

The correlation of denotational and connotational components of

some words is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The correlation of denotational and connotational

components Word+part of speech lonely, adj. notorious, adj.

celebrated, adj. to glare, adj. Denotational component alone,

without company widely known widely known Connotational component

melancholy, sad for criminal act or bad traits of character for

special achievement in science, art, etc. 1. steadily, lastingly

Type of connotation

emotive connotation

to look

to glance, v. to stare, v. to gaze, v. to shiver, v.

to look to look to look to tremble

evaluative connotation, negative evaluative connotation,

positive connotation of duration 2. in anger, rage, etc emotive

connotation; connotation of cause briefly, passingly connotation of

duration steadily, lastingly in emotive connotation; surprise,

curiosity, etc. connotation of cause steadily, lastingly in emotive

connotation tenderness, admiration 1. lastingly connotation of

duration

to shudder, v.

to tremble

2. usu with the cold 1. briefly 2.with horror, disgust, etc.

connotation of cause connotation of duration connotation of

cause; emotive connotation

The above examples show how by singling out denotational and

connotational components we can get a sufficiently clear picture of

what the word really means. The schemes presenting the correlation

of two components of the words also show that a meaning can have

two or more connotational components. The given examples do not

exhaust all the types of connotations but present only a few:

emotive, evaluative connotations, and also connotations of

duration, cause, etc.

3. PRAGMATIC ASPECT

The pragmatic aspect is the part of lexical meaning that conveys

information on the situation of communication. Like the

connotational aspect, the pragmatic aspect falls into four closely

linked together subsections. 1) Information on the time and space

relationship of the participants. Some information which specifies

different parameters of communication may be conveyed not only with

the help of grammatical means (tense forms, personal pronouns,

etc), but through the meaning of the word. For example, the words

come and go can indicate the location of the speaker who is usually

taken as the zero point in the description of the situation of

communication. The time element when related through the pragmatic

aspect of meaning is fixed indirectly. Indirect reference to time

implies that the frequency of occurrence of words may change with

time and in extreme cases words may be out of use or become

obsolete. Thus, the word behold take notice, see (smth. unusual)

as

well as the noun beholder spectator are out of use now but were

widely used in the 17th century.

2) Information on the participants and the given language

community. The language used may be indicative of the social status

of a person, his education, profession, etc. The pragmatic aspect

of the word also may convey information about the social system of

the given language community, its ideology, religion, system of

norms and customs. Let us consider the following sentences: a) They

chucked a stone at the cops, and then did a bunk with the loot. b)

After casting a stone at the police, they absconded with the money.

Sentence A could be said by two criminals talking casually about

the crime afterwards. Sentence B might be said by the chief

inspector in making his official report.

3) Information on the tenor of discourse. The tenors of

discourse reflect how the addresser (the speaker or the writer)

interacts with the addressee (the listener or reader). Tenors are

based on social or family role of the participants of

communication. There may be situation of a mother talking to her

small child, or about her children, or a teacher talking to

students, or friends talking to each other.

4) Information on the register of communication. The conditions

of communication form another important group of factors. The

register defines the general type of the situation of communication

grading the situations in formality. Three main types of the

situations of communication are usually singled out: formal,

neutral and informal. Thus, the pragmatic aspect of meaning refers

words like cordial, fraternal, anticipate, aid to formal register

while units like cut it out, to be kidding, stuff, hi are to be

used in the informal register. The structure of lexical meaning see

in diagram 3.

Diagram 3. Structure of the lexical meaning

LEXICAL MEANING

Denotational aspect

Connotational aspect

Pragmatic aspect

Emotive charge Expressiveness

Evaluation Imagery

Information on the time and space Relationship of the

participants

Information on the participants and the given language

community

Information on the tenor of discourse

Information on the register of communication References: 1. .. .

.: , 2006. .- 18-21. 2. .. . .: , 1979. .- 20-22. 3. .. . -. 2006.

.- 61- 62. 4. .., .., .. . .; , 2006. . — 136-142.

1. Word Meaning Lecture # 6

Grigoryeva M.

2. Word Meaning

Approaches to word meaning

Meaning and Notion (понятие)

Types of word meaning

Types of morpheme meaning

Motivation

3.

Each word has two aspects:

the outer aspect

( its sound form)

cat

the inner aspect

(its meaning)

long-legged, fury animal with sharp teeth

4.

Sound and meaning do not always

constitute a constant unit even in the same

language

EX a temple

a part of a human head

a large church

5. Semantics (Semasiology)

Is a branch of lexicology which studies the

meaning of words and word equivalents

6. Approaches to Word Meaning

The Referential (analytical) approach

The Functional (contextual) approach

Operational (information-oriented)

approach

7. The Referential (analytical) approach

formulates the essence of meaning by

establishing the interdependence between

words and things or concepts they denote

distinguishes between three components closely

connected with meaning:

the sound-form of the linguistic sign,

the concept

the actual referent

8. Basic Triangle

concept – flower

concept (thought,

reference) – the

thought of the object that

singles out its essential

features

referent – object

denoted by the word, part

of reality

sound-form (symbol,

sign) – linguistic sign

sound-form

[rәuz]

referent

9. Meaning and Sound-form

are not identical

different

EX. dove — [dΛv] English

[golub’] Russian

[taube] German

sound-forms

convey one

and

the same meaning

10. Meaning and Sound-form

nearly identical sound-forms have different

meanings in different languages

EX. [kot] English – a small bed for a child

[kot] Russian – a male cat

identical sound-forms have different

meanings (homonyms)

EX. knight [nait]

night [nait]

11. Meaning and Sound-form

even considerable changes in sound-form

do not affect the meaning

EX Old English lufian [luvian] – love [l Λ v]

12. Meaning and Concept

concept is a category of human cognition

concept is abstract and reflects the most

common and typical features of different

objects and phenomena in the world

concept is almost the same for the whole

humanity in one and the same period of its

historical development

meanings of words are different in

different languages

13. Meaning and Concept

identical concepts may have different semantic

structures in different languages

EX. concept “a building for human habitation” –

English

Russian

HOUSE

ДОМ

+ in Russian ДОМ

“fixed residence of family or household

In English

HOME

14. Meaning and Referent

one and the same object (referent) may be

denoted by more than one word of a different

meaning

cat

pussy

animal

tiger

15. Functional Approach

studies the functions of a word in speech

meaning of a word is studied through relations of it with

other linguistic units

EX. to move (we move, move a chair)

movement (movement of smth, slow movement)

The distriution ( the position of the word in relation to

others) of the verb to move and a noun movement is

different as they belong to different classes of words and

their meanings are different

16. Operational approach

is centered on defining meaning through its role in

the process of communication

EX John came at 6

Beside the direct meaning the sentence may imply that:

He was late

He failed to keep his promise

He was punctual as usual

He came but he didn’t want to

The implication depends on the concrete situation

17. Lexical Meaning and Notion

Notion denotes

the reflection in the

mind of real

objects

Notion is a unit of

thinking

Lexical meaning is

the realization of a

notion by means of

a definite language

system

Word is a language

unit

18. Lexical Meaning and Notion

Notions are

international

especially with the

nations of the

same cultural level

Meanings are

nationally limited

EX GO (E) —- ИДТИ(R)

“To move”

BUT !!!

To GO by bus (E)

ЕХАТЬ (R)

EX Man -мужчина, человек

Она – хороший человек (R)

She is a good person (E)

19.

Types of Meaning

types of

meaning

grammatical

meaning

lexico-grammatical

meaning

lexical meaning

denotational

connotational

20. Grammatical Meaning

component of meaning recurrent in

identical sets of individual forms of

different words

EX. girls, winters, toys, tables –

grammatical meaning of plurality

asked, thought, walked –

meaning of past tense

21. Lexico-grammatical meaning (part –of- speech meaning)

is revealed in the classification of lexical items

into major word classes (N, V, Adj, Adv) and

minor ones (artc, prep, conj)

words of one lexico-grammatical class have the

same paradigm

22. Lexical Meaning

is the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit

in all its forms and distributions

EX . Go – goes — went

lexical meaning – process of movement

23. Aspects of Lexical meaning

The denotational aspect

The connotational aspect

The pragmatic aspect

24. Denotational Meaning

“denote” – to be a sign of, stand as a symbol for”

establishes the correlation between the name

and the object

makes communication possible

EX booklet

“a small thin book that gives info about smth”

25. Connotational Meaning

reflects the attitude of the speaker

towards what he speaks about

it is optional – a word either has it or not

Connotation includes:

The emotive charge EX Daddy (for father)

Intensity

EX to adore (for to love)

Imagery

EX to wade “to walk with an effort”

to wade through a book

26. The pragmatic aspect

associations concern the situation in which the

word is uttered,

the social circumstances (formal, informal, etc.),

social relationships between the interlocutors

(polite, rough, etc.), t

the type and purpose of communication (poetic,

official, etc.)

EX horse (neutral)

steed (poetic)

nag (slang)

gee-gee (baby language)

27. Types of Morpheme Meaning

lexical

differential

functional

distributional

28. Lexical Meaning in Morphemes

root-morphemes that are homonymous to

words possess lexical meaning

EX. boy – boyhood – boyish

affixes have lexical meaning of a more

generalized character

EX. –er “agent, doer of an action”

29. Lexical Meaning in Morphemes

has denotational and connotational

components

EX. –ly, -like, -ish –

denotational meaning of similiarity

womanly, womanlike, womanish

connotational component –

-ly (positive evaluation), -ish (deragotary)

женственный женоподобный

30. Differential Meaning

a semantic component that serves to

distinguish one word from all others

containing identical morphemes

EX. cranberry, blackberry, gooseberry

31. Functional Meaning

found only in derivational affixes

a semantic component which serves to

refer the word to the certain part of speech

EX. just, adj. – justice, n.

32. Distributional Meaning

the meaning of the order and the arrangement of

morphemes making up the word

found in words containing more than one

morpheme

different arrangement of the same morphemes

would make the word meaningless

EX. sing- + -er =singer,

-er + sing- = ?

33. Motivation

denotes the relationship between the phonetic

or morphemic composition and structural pattern

of the word on the one hand, and its meaning on

the other

can be

phonetical

morphological

semantic

34. Phonetical Motivation

when there is a certain similarity between

the sounds that make up the word and

those produced by animals, objects, etc.

EX. sizzle, boom, splash, cuckoo

35. Morphological Motivation

when there is a direct connection between the

structure of a word and its meaning

EX. finger-ring – ring-finger,

A direct connection between the lexical meaning

of the component morphemes

EX think –rethink “thinking again”

36. Semantic Motivation

based on co-existence of direct and figurative

meanings of the same word

EX a watchdog –

”a dog kept for watching property”

a watchdog –

“a watchful human guardian” (semantic motivation)

Content

Introduction

Chapter 1. The word as the basic unit of language

Chapter 2. The meaning of the word

2.1 Grammatical meaning of the word

2.2 Lexical meaning of the word

2.2.1 Parf-of-Speech Meaning

2.2.2 Denotational and Connotational meaning of the word

2.2.3 Emotive Charge

2.2.4 Stylistic Reference

2.2.5 Emotive Charge and Stylistic Reference

Chapter 3. Word meaning and motivation

Chapter 4. Word meaning and meaning in morphemes

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

word language meaning speech

The word is one of the fundamental units of language. It is a dialectal unity of form and content. Its content or meaning is not identical to notion, but it may reflect human notion and is considered as the form of their existence. So the definition of a word is one of the most difficult in linguistics, because the simplest word has many different aspects: a sound form, its morphological structure, it may occur in different word-forms and have various meanings.

E. Sapir takes into consideration the syntactic and semantic aspects when he calls the word “one of the smallest completely satisfying bits of isolated “meaning”, into which the sentence resolves itself.” Sapir also points out one more, very important characteristic of the word, its indivisibility: “It cannot be cut into without a disturbance of meaning, one or two other or both of the several parts remaining as a helpless waif on our hands.”

A unit which most people would think of as ‘one word’ may carry a number of meanings, by association with certain contexts. Thus pipe can be any tubular object, a musical instrument or a piece of apparatus for smoking; a hand can be on a clock or watch as well as at the end of the arm. Most of the time, we are able to distinguish the intended meaning by the usual process of mental adjustment to context and register.

Word meaning is not homogeneous, but it is made up of various components, which are described as types of meaning. There are 2 types of meaning to be found in words and word forms:

1) the grammatical meaning;

2) the lexical meaning.

As the world’s global language, English has played a very important role in bringing people from different countries closer and closer, thus yielding great mutual understanding. The author argues that the mastering of the grammatical features of English words together with that of their semantic structures helps to make the communication in English successful. The study on English words in terms of grammar and semantics is, therefore, hoped to be of great value to teachers and learners of English as well as translators into and out of English. In this essay, English words are discussed in terms of their meaning, which poses several problems for the teachers, learners and translators.

Chapter 1. The word as the basic unit of language

The word may be described as the basic unit of language. Uniting meaning and form, it is composed of one or more morphemes, each consisting of one or more spoken sounds or their written representation. The combinations of morphemes within words are subject to certain linking conditions. When a derivational suffix is added a new word is formed, thus, “listen” and “listener” are different words.

When used in sentences together with other words they are syntactically organized. But if we look at the language “speech”, it becomes apparent that words are not neatly segmented as they are by spaces in graphological realization. The pauses in speech do not consistently correspond with word-endings; many languages, including English, do not make it clear to a foreign listener where the utterance is divided into words.

The definition of a word is one of the most difficult in linguistics because the simplest word has many aspects. The variants of definitions were so numerous that some authors collecting them produced works of impressive scope and bulk.

A few examples will suffice to show that any definition is conditioned by the aims and interests of its author.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), one of the great English philosophers, revealed a materialistic approach to the problem of nomination when he wrote that words are not mere sounds but names of matter. Three centuries later the great Russian physiologist I.P. Pavlov (1849-1936) examined the word in connection with his studies of the second signal system, and defined it as a universal signal that can be substitute any other signal from the environment in evoking a response in a human organism. One of the latest developments of science and engineering is machine translation. It also deals with words and requires a rigorous definition for them. It runs as follows: a word is a sequence of graphemes which can occur between spaces, or the representation of such a sequence on morphemic level.

Within the scope of linguistics the word has been defined syntactically, semantically, phonologically and by combining various approaches.

According to John Lyons “One of the characteristics of the word is that it tends to be internally stable (in terms of the order of the component morphemes), but positionally mobile (permutable with other words in the same sentence)”.

A purely semantic treatment will be found in Stephen Ulmann’s explanation: with him connected discourse, if analyzed from the semantic point of view, “will fall into a certain number of meaningful segments which are ultimately compose of meaningful units. These meaningful units are called words.”

The semantic-phonological approach may be illustrated by A.H. Gardiner’s definition: “A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of denoting something which is spoken about.”

The eminent French linguist A. Meillet combines the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria and gives the following definition of the word: “A word is defined by the association of a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment.”

This formula can be accepted with some modifications adding that a word is the smallest significant unit of a given language capable of functioning alone and characterized by positional mobility within a sentence, morphological uninterruptability and semantic integrity. All these criteria are necessary because they permit us to create basis for the oppositions between the word and the phrase, the word and the phoneme, and the word and the morpheme: their common feature is that they are all units of the language, their difference lies in the fact that the phoneme is not significant, and a morpheme cannot be used as a complete utterance.

The weak point of all the above definitions is that they do not establish the relationship between language and thought, which is formulated if we treat the word as a dialectical unity of form and content, in which the form is the spoken or written expression which calls up specific meaning, whereas the content is the meaning rendering the emotion or the concept in the mind of the speaker which he intends to convey to the listener.

Still, the main point can be summarized: “The word is the fundamental unit of language. It is a dialectal unity of form and content.”

Its content or meaning is not identical to notion, but it may reflect human notions, and in this sense may be considered as the form of their existence. Concepts fixed in the meaning of words are formed as generalized and approximately correct reflections of reality, therefore in signifying them words reflect reality in their content.

Chapter 2. The meaning of the word

2.1 Grammatical meaning of the word

Every word has two aspects: the outer aspect (its sound form) and the inner aspect (its meaning). Sound and meaning do not always constitute a constant unit even in the same language.

It is more or less universally recognised that word-meaning is not homogeneous but is made up of various components the combination and the interrelation of which determine to a great extent the inner facet of the word. These components are usually described as types of meaning. The two main types of meaning that are readily observed are the grammatical and the lexical meanings to be found in words and word-forms.

We notice, e.g., that word-forms, such as girls, winters, joys, tables etc. though denoting widely different objects of reality have something in common. This common element is the grammatical meaning of plurality which can be found in all of them.

Thus grammatical meaning may be defined ,as the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, as, e.g., the tense meaning in the word-forms of verbs (asked, thought, walked, etc.) or the case meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girl’s, boy’s, night’s etc.).

In a broad sense it may be argued that linguists who make a distinction between lexical and grammatical meaning are, in fact, making a distinction between the functional (linguistic) meaning which operates at various levels as the interrelation of various linguistic units and referential (conceptual) meaning as the interrelation of linguistic units and referents (or concepts).

In modern linguistic science it is commonly held that some elements of grammatical meaning can be identified by the position of the linguistic unit in relation to other linguistic units, i.e. by its distribution. Word-forms speaks, reads, writes have one and the same grammatical meaning as they can all be found in identical distribution, e.g. only after the pronouns he, she, it and before adverbs like well, badly, to-day, etc.

It follows that a certain component of the meaning of a word is described when you identify it as a part of speech, since different parts of speech are distributionally different (cf. my work and I work).

2.2 Lexical meaning of the word

Comparing word-forms of one and the same word we observe that besides grammatical meaning, there is another component of meaning to be found in them. Unlike the grammatical meaning this component is identical in all the forms of the word. Thus, e.g. the word-forms go, goes, went, going, gone possess different grammatical meanings of tense, person and so on, but in each of these forms we find one and the same semantic component denoting the process of movement. This is the lexical meaning of the word which may be described as the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, i.e. recurrent in all the forms of this word.

The difference between the lexical and the grammatical components of meaning is not to be sought in the difference of the concepts underlying the two types of meaning, but rather in the way they are conveyed. The concept of plurality, e.g., may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the world plurality; it may also be expressed in the forms of various words irrespective of their lexical meaning, e.g. boys, girls, joys etc. The concept of relation may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the word relation and also by any of the prepositions, e.g. in, on, behind etc.

It follows that by lexical meaning we designate the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions, while by grammatical meaning we designate the meaning proper to sets of word-forms common to all words of a certain class. Both the lexical and the grammatical meaning make up the word-meaning as neither can exist without the other. That can be also observed in the semantic analysis of correlated words in different languages. E.g. the Russian word сведения is not semantically identical with the English equivalent information because unlike the Russian сведения the English word does not possess the grammatical meaning of plurality which is part of the semantic structure of the Russian word.

2.2.1 Part-of-Speech Meaning

It is usual to classify lexical items into major word-classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) and minor word-classes (articles, prepositions, conjunctions, etc.).

All members of a major word-class share a distinguishing semantic component which though very abstract may be viewed as the lexical component of part-of-speech meaning. For example, the meaning of “thingness” or substantiality may be found in all the nouns e.g. table, love, sugar, though they possess different grammatical meanings of number, case, etc. It should be noted, however, that the grammatical aspect of the part-of-speech meanings is conveyed as a rule by a set of forms. If we describe the word as a noun we mean to say that it is bound to possess a set of forms expressing the grammatical meaning of number (table — tables), case (boy, boy’s) and so on. A verb is understood to possess sets of forms expressing, e.g., tense meaning (worked — works), mood meaning (work! — (I) work) etc.

The part-of-speech meaning of the words that possess only one form, e.g. prepositions, some adverbs, etc., is observed only in their distribution (to come in (here, there)).

One of the levels at which grammatical meaning operates is that of minor word classes like articles, pronouns, etc.

Members of these word classes are generally listed in dictionaries just as other vocabulary items, that belong to major word-classes of lexical items proper (e.g. nouns, verbs, etc.).

One criterion for distinguishing these grammatical items from lexical items is in terms of closed and open sets. Grammatical items form closed sets of units usually of small membership (e.g. the set of modern English pronouns, articles, etc.). New items are practically never added.

Lexical items proper belong to open sets which have indeterminately large membership; new lexical items which are constantly coined to fulfil the needs of the speech community are added to these open sets.

The interrelation of the lexical and the grammatical meaning and the role played by each varies in different word-classes and even in different groups of words within one and the same class. In some parts of speech the prevailing component is the grammatical type of meaning. The lexical meaning of prepositions for example is, as a rule, relatively vague (one of the students, the roof of the house). The lexical meaning of some prepositions, however, may be comparatively distinct (in/on, under the table). In verbs the lexical meaning usually comes to the fore although in some of them, the verb to be, e.g., the grammatical meaning of a linking element prevails (he works as a teacher and he is a teacher).

2.2.2 Denotational and Connotational meaning of the word

Proceeding with the semantic analysis we observe that lexical meaning is not homogenous either and may be analysed as including denotational and connotational components.

As was mentioned above one of the functions of words is to denote things, concepts and so on. Users of a language cannot have any knowledge or thought of the objects or phenomena of the real world around them unless this knowledge is ultimately embodied in words which have essentially the same meaning for all speakers of that language. This is the denotational meaning, i.e. that component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. There is no doubt that a physicist knows more about the atom than a singer does, or that an arctic explorer possesses a much deeper knowledge of what arctic ice is like than a man who has never been in the North. Nevertheless they use the words atom, Arctic, etc. and understand each other.

The second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component, i.e. the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word.

2.2.3 Emotive Charge

Words contain an element of emotive evaluation as part of the connotational meaning; e.g. a hovel denotes ‘a small house or cottage’ and besides implies that it is a miserable dwelling place, dirty, in bad repair and in general unpleasant to live in. When examining synonyms large, big, tremendous and like, love, worship or words such as girl, girlie; dear, dearie we cannot fail to observe the difference in the emotive charge of the members of these sets. The emotive charge of the words tremendous, worship and girlie is heavier than that of the words large, like and girl. This does not depend on the “feeling” of the individual speaker but is true for all speakers of English. The emotive charge varies in different word-classes. In some of them, in interjections, e.g., the emotive element prevails, whereas in conjunctions the emotive charge is as a rule practically non-existent.

The emotive charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms part of the connotational component of meaning. It should not be confused with emotive implications that the words may acquire in speech. The emotive implication of the word is to a great extent subjective as it greatly depends of the personal experience of the speaker, the mental imagery the word evokes in him. Words seemingly devoid of any emotional element may possess in the case of individual speakers strong emotive implications as may be illustrated, e.g. by the word hospital. What is thought and felt when the word hospital is used will be different in the case of an architect who built it, the invalid staying there after an operation, or the man living across the road.

2.2.4 Stylistic Reference

Words differ not only in their emotive charge but also in their stylistic reference. Stylistically words can be roughly subdivided into literary, neutral and colloquial layers.1

The greater part of the literаrу layer of Modern English vocabulary are words of general use, possessing no specific stylistic reference and known as neutral words. Against the background of neutral words we can distinguish two major subgroups – standard colloquial words and literary or bookish words. This may be best illustrated by comparing words almost identical in their denotational meaning, e. g., ‘parent — father — dad’. In comparison with the word father which is stylistically neutral, dad stands out as colloquial and parent is felt as bookish. The stylistic reference of standard colloquial words is clearly observed when we compare them with their neutral synonyms, e.g. chum — friend, rot — nonsense, etc. This is also true of literary or bookish words, such as, e.g., to presume (to suppose), to anticipate (to expect) and others.

Literary (bookish) words are not stylistically homogeneous. Besides general-literary (bookish) words, e.g. harmony, calamity, alacrity, etc., we may single out various specific subgroups, namely: 1) terms or scientific words such as, e g., renaissance, genocide, teletype, etc.; 2) poetic words and archaisms such as, e.g., whilome — ‘formerly’, aught — ‘anything’, ere — ‘before’, albeit — ‘although’, fare — ‘walk’, etc., tarry — ‘remain’, nay — ‘no’; 3) barbarisms and foreign words, such as, e.g., bon mot — ‘a clever or witty saying’, apropos, faux pas, bouquet, etc. The colloquial words may be subdivided into:

1) Common colloquial words.

2) Slang, i.e. words which are often regarded as a violation of the norms of Standard English, e.g. governor for ‘father’, missus for ‘wife’, a gag for ‘a joke’, dotty for ‘insane’.

3) Professionalisms, i.e. words used in narrow groups bound by the same occupation, such as, e.g., lab for ‘laboratory’, a buster for ‘a bomb’ etc.

4) Jargonisms, i.e. words marked by their use within a particular social group and bearing a secret and cryptic character, e.g. a sucker – ‘a person who is easily deceived’, a squiffer – ‘a concertina’.

5) Vulgarisms, i.e. coarse words that are not generally used in public, e.g. bloody, hell, damn, shut up, etc.

6) Dialectical words, e.g. lass, kirk, etc.

7) Colloquial coinages, e.g. newspaperdom, allrightnik, etc.

2.2.5 Emotive Charge and Stylistic Reference

Stylistic reference and emotive charge of words are closely connected and to a certain degree interdependent. As a rule stylistically coloured words, i.e. words belonging to all stylistic layers except the neutral style are observed to possess a considerable emotive charge. That can be proved by comparing stylistically labelled words with their neutral synonyms. The colloquial words daddy, mammy are more emotional than the neutral father, mother; the slang words mum, bob are undoubtedly more expressive than their neutral counterparts silent, shilling, the poetic yon and steed carry a noticeably heavier emotive charge than their neutral synonyms there and horse. Words of neutral style, however, may also differ in the degree of emotive charge. We see, e.g., that the words large, big, tremendous, though equally neutral as to their stylistic reference are not identical as far as their emotive charge is concerned.

Chapter 3. Word meaning and motivation

From what was said about the distributional meaning in morphemes it follows that there are cases when we can observe a direct connection between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning. This relationship between morphemic structure and meaning is termed morphological motivation.

The main criterion in morphological motivation is the relationship between morphemes. Hence all one-morpheme words, e.g. sing, tell, eat, are by definition non-motivated. In words composed of more than one morpheme the carrier of the word-meaning is the combined meaning of the component morphemes and the meaning of the structural pattern of the word. This can be illustrated by the semantic analysis of different words composed of phonemically identical morphemes with identical lexical meaning. The words finger-ring and ring-finger, e.g., contain two morphemes, the combined lexical meaning of which is the same; the difference in the meaning of these words can be accounted for by the difference in the arrangement of the component morphemes.

If we can observe a direct connection between the structural pattern of the word and its meaning, we say that this word is motivated. Consequently words such as singer, rewrite, eatable, etc., are described as motivated. If the connection between the structure of the lexical unit and its meaning is completely arbitrary and conventional, we speak of non-motivated or idiomatic words, e.g. matter, repeat.

It should be noted in passing that morphological motivation is “relative”, i.e. the degree of motivation may be different. Between the extremes of complete motivation and lack of motivation, there exist various grades of partial motivation. The word endless, e.g., is completely motivated as both the lexical meaning of the component morphemes and the meaning of the pattern is perfectly transparent. The word cranberry is only partially motivated because of the absence of the lexical meaning in the morpheme cran-.

One more point should be noted in connection with the problem in question. A synchronic approach to morphological motivation presupposes historical changeability of structural patterns and the ensuing degree of motivation. Some English place-names may serve as an illustration. Such place-names as Newtowns and Wildwoods are lexically and structurally motivated and may be easily analysed into component morphemes. Other place-names, e.g. Essex, Norfolk, Sutton, are non-motivated. To the average English speaker these names are non-analysable lexical units like sing or tell. However, upon examination the student of language history will perceive their components to be East+Saxon, North+Folk and South+Town which shows that in earlier days they .were just as completely motivated as Newtowns or Wildwoods are in Modern English.

Motivation is usually thought of as proceeding from form or structure to meaning. Morphological motivation as discussed above implies a direct connection between the morphological structure of the word and its meaning. Some linguists, however, argue that words can be motivated in more than one way and suggest another type of motivation which may be described as a direct connection between the phonetical structure of the word and its meaning. It is argued that speech sounds may suggest spatial and visual dimensions, shape, size, etc. Experiments carried out by a group of linguists showed that back open vowels are suggestive of big size, heavy weight, dark colour, etc. The experiments were repeated many times and the results were always the same. Native speakers of English were asked to listen to pairs of antonyms from an unfamiliar (or non-existent) language unrelated to English, e.g. ching – chung and then to try to find the English equivalents, e.g. light – heavy, big – small, etc.), which foreign word translates which English word. About 90 per cent of English speakers felt that ching is the equivalent of the English light (small) and chung of its antonym heavy (large).

It is also pointed out that this type of phonetical motivation may be observed in the phonemic structure of some newly coined words. For example, the small transmitter that specialises in high frequencies is called ‘a tweeter’, the transmitter for low frequences ‘a woofer’.

Another type of phonetical motivation is represented by such words as swish, sizzle, boom, splash, etc. These words may be defined as phonetically motivated because the soundclusters [swi∫, sizl, bum, splæ∫] are a direct imitation of the sounds these words denote. It is also suggested that sounds themselves may be emotionally expressive which accounts for the phonetical motivation in certain words. Initial [f] and [p], e.g., are felt as expressing scorn, contempt, disapproval or disgust which can be illustrated by the words pooh! fie! fiddle-sticks, flim-flam and the like. The sound-cluster [iŋ] is imitative of sound or swift movement as can be seen in words ring, sing, swing, fling, etc. Thus, phonetically such words may be considered motivated.

This hypothesis seems to require verification. This of course is not to deny that there are some words which involve phonetical symbolism: these are the onomatopoeic, imitative or echoic words such as the English cuckoo, splash and whisper: And even these are not completely motivated but seem to be conventional to quite a large extent (cf. кукареку and cock-a-doodle-doo). In any case words like these constitute only a small and untypical minority in the language. As to symbolic value of certain sounds, this too is disproved by the fact that identical sounds and sound-clusters may be found in words of widely different meaning, e.g. initial [p] and [f], are found in words expressing contempt and disapproval (fie, pooh) and also in such words as ploughs fine, and others. The sound-cluster [in] which is supposed to be imitative of sound or swift movement (ring, swing) is also observed in semantically different words, e.g. thing, king, and others.

The term motivation is also used by a number of linguists to denote the relationship between the central and the coexisting meaning or meanings of a word which are understood as a metaphorical extension of the central meaning. Metaphorical extension may be viewed as generalisation of the denotational meaning of a word permitting it to include new referents which are in some way like the original class of referents. Similarity of various aspects and/or functions of different classes of referents may account for the semantic motivation of a number of minor meanings. For example, a woman who has given birth is called a mother; by extension, any act that gives birth is associated with being a mother, e.g. in Necessity is the mother of invention. The same principle can be observed in other meanings: a mother looks after a child, so that we can say She became a mother to her orphan nephew, or Romulus and Remus were supposedly mothered by a wolf. Such metaphoric extension may be observed in the so-called trite metaphors, such as burn with anger, break smb’s heart, jump at a chance, etc.

If metaphorical extension is observed in the relationship of the central and a minor word meaning it is often observed in the relationship between its synonymic or antonymic meanings. Thus, a few years ago the phrases a meeting at the summit, a summit meeting appeared in the newspapers.

Cartoonists portrayed the participants of such summit meetings sitting on mountain tops. Now when lesser diplomats confer the talks are called foothill meetings. In this way both summit and its antonym foothill undergo the process of metaphorical extension.

Chapter 4. Word meaning and meaning in morphemes

In modern linguistics it is more or less universally recognised that the smallest two-facet language unit possessing both sound-form and meaning is the morpheme. Yet, whereas the phono-morphological structure of language has been subjected to a thorough linguistic analysis, the problem of types of meaning and semantic peculiarities of morphemes has not been properly investigated. A few points of interest, however, may be mentioned in connection with some recent observations in “this field.

It is generally assumed that one of the semantic features of some morphemes which distinguishes them from words is that they do not possess grammatical meaning. Comparing the word man, e.g., and the morpheme man-(in manful, manly, etc.) we see that we cannot find in this morpheme the grammatical meaning of case and number observed in the word man. Morphemes are consequently regarded as devoid of grammatical meaning.

Many English words consist of a single root-morpheme, so when we say that most morphemes possess lexical meaning we imply mainly the root-morphemes in such words. It may be easily observed that the lexical meaning of the word boy and the lexical meaning of the root-morpheme boy — in such words as boyhood, boyish and others is very much the same.

Just as in words lexical meaning in morphemes may also be analysed into denotational and connotational components. The connotational component of meaning may be found not only in root-morphemes but in affixational morphemes as well. Endearing and diminutive suffixes, e.g. -ette (kitchenette), -ie(y) (dearie, girlie), -ling (duckling), clearly bear a heavy emotive charge. Comparing the derivational morphemes with the same denotational meaning we see that they sometimes differ in connotation only. The morphemes, e.g. -ly, -like, -ish, have the denotational meaning of similarity in the words womanly, womanlike, womanish, the connotational component, however, differs and ranges from the positive evaluation in —ly (womanly) to the derogatory in -ish (womanish): Stylistic reference may also be found in morphemes of different types. The stylistic value of such derivational morphemes as, e.g. -ine (chlorine), -oid (rhomboid), -escence (effervescence) is clearly perceived to be bookish or scientific.

The lexical meaning of the affixal morphemes is, as a rule, of a more generalising character. The suffix —er, e.g. carries the meaning ‘the agent, the doer of the action’, the suffix—less denotes lack or absence of something. It should also be noted that the root-morphemes do not “possess the part-of-speech meaning (cf. manly, manliness, to man); in derivational morphemes the lexical and the part-of-speech meaning may be so blended as to be almost inseparable. In the derivational morphemes —er and —less discussed above the lexical meaning is just as clearly perceived as their part-of-speech meaning. In some morphemes, however, for instance -ment or -ous (as in movement or laborious), it is the part-of-speech meaning that prevails, the lexical meaning is but vaguely felt.

In some cases the functional meaning predominates. The morpheme —ice in the word justice, e.g., seems to serve principally to transfer the part-of-speech meaning of the morpheme just – into another class and namely that of noun. It follows that some morphemes possess only the functional meaning, i.e. they are the carriers of part-of-speech meaning.

Besides the types of meaning proper both to words and morphemes the latter may possess specific meanings of their own, namely the differential and the distributional meanings. Differential meaning is the semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes. In words consisting of two or more morphemes, one of the constituent morphemes always has differential meaning. In such words as, e. g., bookshelf, the morpheme —shelf serves to distinguish the word from other words containing the morpheme book-, e.g. from bookcase, book-counter and so on. In other compound words, e.g. notebook, the morpheme note— will be seen to possess the differential meaning which distinguishes notebook from exercisebook, copybook, etc. It should be clearly understood that denotational and differential meanings are not mutually exclusive. Naturally the morpheme —shelf in bookshelf possesses denotational meaning which is the dominant component of meaning. There are cases, however, when it is difficult or even impossible to assign any denotational meaning to the morpheme, e.g. cran— in cranberry, yet it clearly bears a relationship to the meaning of the word as a whole through the differential component (cranberry and blackberry, gooseberry) which in this particular case comes to the fore. One of the disputable points of morphological analysis is whether such words as deceive, receive, perceive consist of two component morphemes. If we assume, however, that the morpheme —ceive may be singled out it follows that the meaning of the morphemes re-, per, de— is exclusively differential, as, at least synchronically, there is no denotational meaning proper to them.

Distributional meaning is the meaning of the order and arrangement of morphemes making up the word. It is found in all words containing more than one morpheme. The word singer, e.g., is composed of two morphemes sing— and —er both of which possess the denotational meaning and namely ‘to make musical sounds’ (sing-) and ‘the doer of the action’ (-er). There is one more element of meaning, however, that enables us to understand the word and that is the pattern of arrangement of the component morphemes. A different arrangement of the same morphemes, e.g. *ersing, would make the word meaningless. Compare also boyishness and *nessishboy in which a different pattern of arrangement of the three morphemes boy-ish-ness turns it into a meaningless string of sounds.

Conclusion

So in this work word-meaning is viewed as closely connected but not identical with either the sound-form of the word or with its referent. Proceeding from the basic assumption of the objectivity of language and from the understanding of linguistic units as two-facet entities we regard meaning as the inner facet of the word, inseparable from its outer facet which is indispensable to the existence of meaning and to intercommunication.

The two main types of word-meaning are the grammatical and the lexical meanings found in all words. The interrelation of these two types of meaning may be different in different groups of words. Lexical meaning is viewed as possessing denotational and connotational components. The denotational component is actually what makes communication possible. The connotational component comprises the stylistic reference and the emotive charge proper to the word as a linguistic unit in the given language system. The subjective emotive implications acquired by words in speech lie outside the semantic structure of words as they may vary from speaker to speaker but are not proper to words as units of language.

Lexical meaning with its denotational and connotational components may be found in morphemes of different types. The denotational meaning in affixal morphemes may be rather vague and abstract, the lexical meaning and the part-of-speech meaning tending to blend.

It is suggested that in addition to lexical meaning morphemes may contain specific types of meaning: differential, functional and distributional.

We pointed out different motivations. Morphological motivation implies a direct connection between the lexical meaning of the component morphemes, the pattern of their arrangement and the meaning of the word. The degree of morphological motivation may be different varying from the extreme of complete motivation to lack of motivation. Phonetical motivation implies a direct connection between the phonetic structure of the word and its meaning. Phonetical motivation is not universally recognised in modern linguistic science. Semantic motivation implies a direct connection between the central and marginal meanings of the word. This connection may be regarded as a metaphoric extension of the central meaning based on the similarity of different classes of referents denoted by the word.

Bibliography

1. Арнольд И. В. Лексикология современного английского языка: Учеб. для ин-тов и фак. иностр. яз. -3-е изд., перераб. и доп. -М.: Высш. шк., 1986. -295 с.

2. Атрушина Г. Б., Афанасьева О. В., Морозова Н. Н. Лексикология английского языка: Учеб. пособие для студентов. — М.: Дрофа, 1999. — 288с.

3. Виноградов В.В. Лексикология и лексикография: Избранные труды. М., 1977.

4. Звягинцев В.А. Семасиология. – M.: 1957, с. 350.

5. Зенков Г.С., Сапожникова И.А. Введение в языкознание: Учеб. пособие для студентов дистанционного обучения КГНУ — Б.: ИИМОП КГНУ, 1998.- 218 с.

6. Лексикология английского языка: Учебник для ин-тов и фак. иностр. яз./Р.Гинзбург, С. С. Хидекель, Г. Ю. Князева и А. А. Санкин. — 2-е изд., испр. и доп. — М.: Высш. школа, 1979. — 269 с.

7. Медникова Э. М. Значение слова и методы его описания. М., 1974.

8. Смирницкий А. И. Лексикология английского языка. М., 1956,

9. Chapman R. “Linguistics and literture”, 1973.

10. Galperin I.R. Stylistics. — M..: 1971, 367 p.

11. Gardiner A.H. The Definition of the Word and the Sentence // The British Journal of Psychology. 1922. XII. P. 355

12. Lyons, John. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Univ. Press, 1969.

Размещено на

Теги:

Тypes of word meaning

Курсовая работа (теория)

Английский

Просмотров: 48477

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Тypes of word meaning