A word list (or lexicon) is a list of a language’s lexicon (generally sorted by frequency of occurrence either by levels or as a ranked list) within some given text corpus, serving the purpose of vocabulary acquisition. A lexicon sorted by frequency «provides a rational basis for making sure that learners get the best return for their vocabulary learning effort» (Nation 1997), but is mainly intended for course writers, not directly for learners. Frequency lists are also made for lexicographical purposes, serving as a sort of checklist to ensure that common words are not left out. Some major pitfalls are the corpus content, the corpus register, and the definition of «word». While word counting is a thousand years old, with still gigantic analysis done by hand in the mid-20th century, natural language electronic processing of large corpora such as movie subtitles (SUBTLEX megastudy) has accelerated the research field.

In computational linguistics, a frequency list is a sorted list of words (word types) together with their frequency, where frequency here usually means the number of occurrences in a given corpus, from which the rank can be derived as the position in the list.

| Type | Occurrences | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| the | 3,789,654 | 1st |

| he | 2,098,762 | 2nd |

| […] | ||

| king | 57,897 | 1,356th |

| boy | 56,975 | 1,357th |

| […] | ||

| stringyfy | 5 | 34,589th |

| […] | ||

| transducionalify | 1 | 123,567th |

MethodologyEdit

FactorsEdit

Nation (Nation 1997) noted the incredible help provided by computing capabilities, making corpus analysis much easier. He cited several key issues which influence the construction of frequency lists:

- corpus representativeness

- word frequency and range

- treatment of word families

- treatment of idioms and fixed expressions

- range of information

- various other criteria

CorporaEdit

Traditional written corpusEdit

Most of currently available studies are based on written text corpus, more easily available and easy to process.

SUBTLEX movementEdit

However, New et al. 2007 proposed to tap into the large number of subtitles available online to analyse large numbers of speeches. Brysbaert & New 2009 made a long critical evaluation of this traditional textual analysis approach, and support a move toward speech analysis and analysis of film subtitles available online. This has recently been followed by a handful of follow-up studies,[1] providing valuable frequency count analysis for various languages. Indeed, the SUBTLEX movement completed in five years full studies for French (New et al. 2007), American English (Brysbaert & New 2009; Brysbaert, New & Keuleers 2012), Dutch (Keuleers & New 2010), Chinese (Cai & Brysbaert 2010), Spanish (Cuetos et al. 2011), Greek (Dimitropoulou et al. 2010), Vietnamese (Pham, Bolger & Baayen 2011), Brazil Portuguese (Tang 2012) and Portugal Portuguese (Soares et al. 2015), Albanian (Avdyli & Cuetos 2013), Polish (Mandera et al. 2014) and Catalan (2019[2]). SUBTLEX-IT (2015) provides raw data only.[1]

Lexical unitEdit

In any case, the basic «word» unit should be defined. For Latin scripts, words are usually one or several characters separated either by spaces or punctuation. But exceptions can arise, such as English «can’t», French «aujourd’hui», or idioms. It may also be preferable to group words of a word family under the representation of its base word. Thus, possible, impossible, possibility are words of the same word family, represented by the base word *possib*. For statistical purpose, all these words are summed up under the base word form *possib*, allowing the ranking of a concept and form occurrence. Moreover, other languages may present specific difficulties. Such is the case of Chinese, which does not use spaces between words, and where a specified chain of several characters can be interpreted as either a phrase of unique-character words, or as a multi-character word.

StatisticsEdit

It seems that Zipf’s law holds for frequency lists drawn from longer texts of any natural language. Frequency lists are a useful tool when building an electronic dictionary, which is a prerequisite for a wide range of applications in computational linguistics.

German linguists define the Häufigkeitsklasse (frequency class) of an item in the list using the base 2 logarithm of the ratio between its frequency and the frequency of the most frequent item. The most common item belongs to frequency class 0 (zero) and any item that is approximately half as frequent belongs in class 1. In the example list above, the misspelled word outragious has a ratio of 76/3789654 and belongs in class 16.

where is the floor function.

Frequency lists, together with semantic networks, are used to identify the least common, specialized terms to be replaced by their hypernyms in a process of semantic compression.

PedagogyEdit

Those lists are not intended to be given directly to students, but rather to serve as a guideline for teachers and textbook authors (Nation 1997). Paul Nation’s modern language teaching summary encourages first to «move from high frequency vocabulary and special purposes [thematic] vocabulary to low frequency vocabulary, then to teach learners strategies to sustain autonomous vocabulary expansion» (Nation 2006).

Effects of words frequencyEdit

Word frequency is known to have various effects (Brysbaert et al. 2011; Rudell 1993). Memorization is positively affected by higher word frequency, likely because the learner is subject to more exposures (Laufer 1997). Lexical access is positively influenced by high word frequency, a phenomenon called word frequency effect (Segui et al.). The effect of word frequency is related to the effect of age-of-acquisition, the age at which the word was learned.

LanguagesEdit

Below is a review of available resources.

EnglishEdit

Word counting dates back to Hellenistic time. Thorndike & Lorge, assisted by their colleagues, counted 18,000,000 running words to provide the first large-scale frequency list in 1944, before modern computers made such projects far easier (Nation 1997).

Traditional listsEdit

These all suffer from their age. In particular, words relating to technology, such as «blog,» which, in 2014, was #7665 in frequency[3] in the Corpus of Contemporary American English,[4] was first attested to in 1999,[5][6][7] and does not appear in any of these three lists.

- The Teachers Word Book of 30,000 words (Thorndike and Lorge, 1944)

The TWB contains 30,000 lemmas or ~13,000 word families (Goulden, Nation and Read, 1990). A corpus of 18 million written words was hand analysed. The size of its source corpus increased its usefulness, but its age, and language changes, have reduced its applicability (Nation 1997).

- The General Service List (West, 1953)

The GSL contains 2,000 headwords divided into two sets of 1,000 words. A corpus of 5 million written words was analyzed in the 1940s. The rate of occurrence (%) for different meanings, and parts of speech, of the headword are provided. Various criteria, other than frequence and range, were carefully applied to the corpus. Thus, despite its age, some errors, and its corpus being entirely written text, it is still an excellent database of word frequency, frequency of meanings, and reduction of noise (Nation 1997). This list was updated in 2013 by Dr. Charles Browne, Dr. Brent Culligan and Joseph Phillips as the New General Service List.

- The American Heritage Word Frequency Book (Carroll, Davies and Richman, 1971)

A corpus of 5 million running words, from written texts used in United States schools (various grades, various subject areas). Its value is in its focus on school teaching materials, and its tagging of words by the frequency of each word, in each of the school grade, and in each of the subject areas (Nation 1997).

- The Brown (Francis and Kucera, 1982) LOB and related corpora

These now contain 1 million words from a written corpus representing different dialects of English. These sources are used to produce frequency lists (Nation 1997).

FrenchEdit

- Traditional datasets

A review has been made by New & Pallier.

An attempt was made in the 1950s–60s with the Français fondamental. It includes the F.F.1 list with 1,500 high-frequency words, completed by a later F.F.2 list with 1,700 mid-frequency words, and the most used syntax rules.[8] It is claimed that 70 grammatical words constitute 50% of the communicatives sentence,[9] while 3,680 words make about 95~98% of coverage.[10] A list of 3,000 frequent words is available.[11]

The French Ministry of the Education also provide a ranked list of the 1,500 most frequent word families, provided by the lexicologue Étienne Brunet.[12] Jean Baudot made a study on the model of the American Brown study, entitled «Fréquences d’utilisation des mots en français écrit contemporain».[13]

More recently, the project Lexique3 provides 142,000 French words, with orthography, phonetic, syllabation, part of speech, gender, number of occurrence in the source corpus, frequency rank, associated lexemes, etc., available under an open license CC-by-sa-4.0.[14]

- Subtlex

This Lexique3 is a continuous study from which originate the Subtlex movement cited above. New et al. 2007 made a completely new counting based on online film subtitles.

SpanishEdit

There have been several studies of Spanish word frequency (Cuetos et al. 2011).[15]

ChineseEdit

Chinese corpora have long been studied from the perspective of frequency lists. The historical way to learn Chinese vocabulary is based on characters frequency (Allanic 2003). American sinologist John DeFrancis mentioned its importance for Chinese as a foreign language learning and teaching in Why Johnny Can’t Read Chinese (DeFrancis 1966). As a frequency toolkit, Da (Da 1998) and the Taiwanese Ministry of Education (TME 1997) provided large databases with frequency ranks for characters and words. The HSK list of 8,848 high and medium frequency words in the People’s Republic of China, and the Republic of China (Taiwan)’s TOP list of about 8,600 common traditional Chinese words are two other lists displaying common Chinese words and characters. Following the SUBTLEX movement, Cai & Brysbaert 2010 recently made a rich study of Chinese word and character frequencies.

OtherEdit

Most frequently used words in different languages based on Wikipedia or combined corpora.[16]

See alsoEdit

- Letter frequency

- Most common words in English

- Long tail

- Google Ngram Viewer – shows changes in word/phrase frequency (and relative frequency) over time

NotesEdit

- ^ a b «Crr » Subtitle Word Frequencies».

- ^ Boada, Roger; Guasch, Marc; Haro, Juan; Demestre, Josep; Ferré, Pilar (1 February 2020). «SUBTLEX-CAT: Subtitle word frequencies and contextual diversity for Catalan». Behavior Research Methods. 52 (1): 360–375. doi:10.3758/s13428-019-01233-1. ISSN 1554-3528. PMID 30895456. S2CID 84843788.

- ^ «Words and phrases: Frequency, genres, collocates, concordances, synonyms, and WordNet».

- ^ «Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA)».

- ^ «It’s the links, stupid». The Economist. 20 April 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ Merholz, Peter (1999). «Peterme.com». Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 1999-10-13. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ Kottke, Jason (26 August 2003). «kottke.org». Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ^ «Le français fondamental». Archived from the original on 2010-07-04.

- ^ Ouzoulias, André (2004), Comprendre et aider les enfants en difficulté scolaire: Le Vocabulaire fondamental, 70 mots essentiels (PDF), Retz — Citing V.A.C Henmon

- ^ «Generalities».

- ^ «PDF 3000 French words».

- ^ «Maitrise de la langue à l’école: Vocabulaire». Ministère de l’éducation nationale.

- ^ Baudot, J. (1992), Fréquences d’utilisation des mots en français écrit contemporain, Presses de L’Université, ISBN 978-2-7606-1563-2

- ^ «Lexique».

- ^ «Spanish word frequency lists». Vocabularywiki.pbworks.com.

- ^ Most frequently used words in different languages, ezglot

ReferencesEdit

Theoretical conceptsEdit

- Nation, P. (1997), «Vocabulary size, text coverage, and word lists», in Schmitt; McCarthy (eds.), Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 6–19, ISBN 978-0-521-58551-4

- Laufer, B. (1997), «What’s in a word that makes it hard or easy? Some intralexical factors that affect the learning of words.», Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 140–155, ISBN 9780521585514

- Nation, P. (2006), «Language Education — Vocabulary», Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Oxford: 494–499, doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00678-7, ISBN 9780080448541.

- Brysbaert, Marc; Buchmeier, Matthias; Conrad, Markus; Jacobs, Arthur M.; Bölte, Jens; Böhl, Andrea (2011). «The word frequency effect: a review of recent developments and implications for the choice of frequency estimates in German». Experimental Psychology. 58 (5): 412–424. doi:10.1027/1618-3169/a000123. PMID 21768069. database

- Rudell, A.P. (1993), «Frequency of word usage and perceived word difficulty : Ratings of Kucera and Francis words», Most, vol. 25, pp. 455–463

- Segui, J.; Mehler, Jacques; Frauenfelder, Uli; Morton, John (1982), «The word frequency effect and lexical access», Neuropsychologia, 20 (6): 615–627, doi:10.1016/0028-3932(82)90061-6, PMID 7162585, S2CID 39694258

- Meier, Helmut (1967), Deutsche Sprachstatistik, Hildesheim: Olms (frequency list of German words)

- DeFrancis, John (1966), Why Johnny can’t read Chinese (PDF)

- Allanic, Bernard (2003), The corpus of characters and their pedagogical aspect in ancient and contemporary China (fr: Les corpus de caractères et leur dimension pédagogique dans la Chine ancienne et contemporaine) (These de doctorat), Paris: INALCO

Written texts-based databasesEdit

- Da, Jun (1998), Jun Da: Chinese text computing, retrieved 2010-08-21.

- Taiwan Ministry of Education (1997), 八十六年常用語詞調查報告書, retrieved 2010-08-21.

- New, Boris; Pallier, Christophe, Manuel de Lexique 3 (in French) (3.01 ed.).

- Gimenes, Manuel; New, Boris (2016), «Worldlex: Twitter and blog word frequencies for 66 languages», Behavior Research Methods, 48 (3): 963–972, doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0621-0, ISSN 1554-3528, PMID 26170053.

SUBTLEX movementEdit

- New, B.; Brysbaert, M.; Veronis, J.; Pallier, C. (2007). «SUBTLEX-FR: The use of film subtitles to estimate word frequencies» (PDF). Applied Psycholinguistics. 28 (4): 661. doi:10.1017/s014271640707035x. hdl:1854/LU-599589. S2CID 145366468. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-24.

- Brysbaert, Marc; New, Boris (2009), «Moving beyond Kucera and Francis: a critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English» (PDF), Behavior Research Methods, 41 (4): 977–990, doi:10.3758/brm.41.4.977, PMID 19897807, S2CID 4792474

- Keuleers, E, M, B.; New, B. (2010), «SUBTLEX—NL: A new measure for Dutch word frequency based on film subtitles», Behavior Research Methods, 42 (3): 643–650, doi:10.3758/brm.42.3.643, PMID 20805586

- Cai, Q.; Brysbaert, M. (2010), «SUBTLEX-CH: Chinese Word and Character Frequencies Based on Film Subtitles», PLOS ONE, 5 (6): 8, Bibcode:2010PLoSO…510729C, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010729, PMC 2880003, PMID 20532192

- Cuetos, F.; Glez-nosti, Maria; Barbón, Analía; Brysbaert, Marc (2011), «SUBTLEX-ESP : Spanish word frequencies based on film subtitles» (PDF), Psicológica, 32: 133–143

- Dimitropoulou, M.; Duñabeitia, Jon Andoni; Avilés, Alberto; Corral, José; Carreiras, Manuel (2010), «SUBTLEX-GR: Subtitle-Based Word Frequencies as the Best Estimate of Reading Behavior: The Case of Greek», Frontiers in Psychology, 1 (December): 12, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00218, PMC 3153823, PMID 21833273

- Pham, H.; Bolger, P.; Baayen, R.H. (2011), «SUBTLEX-VIE : A Measure for Vietnamese Word and Character Frequencies on Film Subtitles», ACOL

- Brysbaert, M.; New, Boris; Keuleers, E. (2012), «SUBTLEX-US : Adding Part of Speech Information to the SUBTLEXus Word Frequencies» (PDF), Behavior Research Methods: 1–22 (databases)

- Mandera, P.; Keuleers, E.; Wodniecka, Z.; Brysbaert, M. (2014). «Subtlex-pl: subtitle-based word frequency estimates for Polish» (PDF). Behav Res Methods. 47 (2): 471–483. doi:10.3758/s13428-014-0489-4. PMID 24942246. S2CID 2334688.

- Tang, K. (2012), «A 61 million word corpus of Brazilian Portuguese film subtitles as a resource for linguistic research», UCL Work Pap Linguist (24): 208–214

- Avdyli, Rrezarta; Cuetos, Fernando (June 2013), «SUBTLEX- AL: Albanian word frequencies based on film subtitles», ILIRIA International Review, 3 (1): 285–292, doi:10.21113/iir.v3i1.112, ISSN 2365-8592

- Soares, Ana Paula; Machado, João; Costa, Ana; Iriarte, Álvaro; Simões, Alberto; de Almeida, José João; Comesaña, Montserrat; Perea, Manuel (April 2015), «On the advantages of word frequency and contextual diversity measures extracted from subtitles: The case of Portuguese», The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68 (4): 680–696, doi:10.1080/17470218.2014.964271, PMID 25263599, S2CID 5376519

Learn words with Flashcards and other activities

Other learning activities

Full list of words from this list:

-

absolution

the act of being formally forgiven

-

anarchy

a state of lawlessness and disorder

-

anthropology

science of the origins and social relationships of humans

-

age

how long something has existed

-

agriculture

the practice of cultivating the land or raising stock

-

archaeology

the branch of anthropology that studies prehistoric people

-

architecture

the discipline dealing with the design of fine buildings

-

archive

a depository containing historical records and documents

-

artifact

a man-made object

-

artisan

a skilled worker who practices some trade or handicraft

-

autobiography

a book or account of your own life

-

barter

exchange goods without involving money

-

boycott

refusal to have commercial dealings with some organization

-

census

a periodic count of the population

-

century

a period of 100 years

-

city state

a state consisting of a sovereign city

-

civilization

a society in an advanced state of social development

-

clergy

the entire class of religious officials

-

colony

a group of organisms of the same type living together

-

confrontation

discord resulting from a clash of ideas or opinions

-

constitution

the act of forming or establishing something

-

culture

all the knowledge and values shared by a society

-

chronological

relating to or arranged according to the order of time

-

curator

the custodian of a collection, as a museum or library

-

data

a collection of facts from which conclusions may be drawn

-

deity

a supernatural being worshipped as controlling the world

-

deism

the belief in God on the basis of reason alone

-

democracy

the orientation of those who favor government by the people

-

demographic

a statistic characterizing human populations

-

dictator

a ruler who is unconstrained by law

-

diplomacy

negotiation between nations

-

document

a representation of a person’s thinking with symbolic marks

-

documentary

a film presenting the facts about a person or event

-

domino effect

the consequence of one event setting off a chain of similar events (like a falling domino causing a whole row of upended dominos to fall)

-

domestic

of or relating to the home

-

dynasty

a sequence of powerful leaders in the same family

-

economics

science dealing with the circulation of goods and services

-

empire

the domain ruled by a single authoritative sovereign

-

enlightenment

education that results in the spread of knowledge

-

entrepreneur

someone who organizes a business venture

-

epoch

a period marked by distinctive character

-

era

a period marked by distinctive character

-

exile

the act of expelling a person from their native land

-

export

sell or transfer abroad

-

fossil

the remains of a plant or animal from a past geological age

-

heresy

a belief that rejects the orthodox tenets of a religion

-

hierarchy

a series of ordered groupings within a system

-

impeach

bring an accusation against

-

immigration

movement of people into a country or area

-

inflation

the act of filling something with air

-

initiative

readiness to embark on bold new ventures

-

import

bring in from abroad

-

irrigation

the act of supplying dry land with water by artificial means

-

isolationist

of or relating to isolationism

-

intolerable

incapable of being put up with

-

Judaical

of or relating to or characteristic of the Jews or their culture or religion

-

jury system

a legal system for determining the facts at issue in a law suit

-

legislative

relating to a lawmaking assembly

-

literacy

the ability to read and write

-

mass medium

a technology that publicly transmits to a large audience

-

malnutrition

a state of poor nourishment

-

migration

the movement of persons from one locality to another

-

millennium

a span of 1000 years

-

monotheistic

believing that there is only one god

-

monarchy

autocracy governed by a ruler who usually inherits authority

-

myth

a traditional story serving to explain a world view

-

nationalism

the doctrine that your country’s interests are superior

-

neglect

leave undone or leave out

-

neutrality

nonparticipation in a dispute or war

-

nomad

a member of a people who have no permanent home

-

paleontology

the earth science that studies fossil organisms

-

pardon

accept an excuse for

-

patriarch

the male head of family or tribe

-

perspective

a way of regarding situations or topics

-

poll

the counting of votes (as in an election)

-

prehistoric

belonging to or existing before recorded times

-

primary

of first rank or importance or value

-

propaganda

information that is spread to promote some cause

-

province

the territory in an administrative district of a nation

-

ratification

making something valid by formally confirming it

-

reformation

improvement in the condition of institutions or practices

-

refugee

an exile who flees for safety

-

republic

a form of government whose head of state is not a monarch

-

research

a seeking for knowledge

-

revolution

a single complete turn

-

rural

living in or characteristic of farming or country life

-

schism

division of a group into opposing factions

-

scribe

someone employed to make written copies of documents

-

secular

someone who is not a clergyman or a professional person

-

secondary

being of second rank or importance or value

-

sectionalism

excessive devotion to the interests of a particular region

-

segregation

the act of keeping apart

-

social contract

an agreement that results in the organization of society

-

socialism

a political theory advocating state ownership of industry

-

statistics

a branch of mathematics concerned with quantitative data

-

suffrage

a legal right to vote

-

tariff

a government tax on imports or exports

-

technology

the practical application of science to commerce or industry

-

theocracy

a political unit governed by a deity

-

totalitarianism

a form of government in which the ruler is unconstrained

-

tribe

a group of people with shared ancestry and customs

-

tribune

an ancient Roman official elected by the plebeians

-

tyranny

government in which the ruler is an absolute dictator

-

urban

relating to a city or densely populated area

-

veto

a vote that blocks a decision

-

Zealot

a member of an ancient Jewish sect in Judea in the first century who fought to the death against the Romans and who killed or persecuted Jews who collaborated with the Romans

Created on September 21, 2011

History, like many disciplines, has its own distinctive styles of writing. While learning to think about the past, history students must also learn to write history in a clear and convincing manner. Those who are already strong writers will relish this challenge but others may find it confronting.

This page contains several lists of ‘history words’ to provide you with a head start in writing history. You will encounter many of these words when reading history while others are useful descriptive words you can use in your own writing. These lists are not comprehensive or exhaustive but may prove useful for inexperienced writers.

If you are new to history, or have difficulty finding the right words, save or print off these lists and keep them to hand. If you would like to suggest words for these lists, please make contact with your ideas.

Sections or groups in society

| academia | People who work in schools and universities, teaching or undertaking research |

| agrarian | People involved in producing crops and livestock through farming |

| aristocracy | People who possess noble titles and privileges, often with wealth and power |

| artisans | People involved in the manufacture or repair of items, such as mechanics |

| bourgeoisie | People who own capital, such as land, factories and raw materials |

| capitalist | As for bourgeoisie (above), people who own capital and the means of production |

| clergy | People ordained by the church to carry out its functions, such as priests, monks and nuns |

| commercial | People involved in trade, such as importing and exporting, buying and selling |

| economic | People, institutions and activities that produce society’s wants and needs |

| establishment | The political, social and economic elites who wield power in a society |

| gender | Refers to the rights, roles and conditions of men and women in a society |

| industrial | The mass production of wants and needs, particularly on a large scale |

| intelligentsia | People who develop ideas, theories and policies in a society |

| middle class | The social classes who own some property and enjoy safe and stable standards of living |

| military | A state’s defence forces, such as the army, navy and air force |

| monarchy | The institution of hereditary royalty, led by a king, queen or emperor |

| nobility | People who possess noble titles, either from birth, royal grant or venality |

| peasantry | People who work the land, usually as tenant farmers and often in impoverished conditions |

| philosophes | Intellectuals and writers who engage in critical study of society, beliefs and ideas |

| political | The people, bodies and processes that govern and make decisions in a society |

| proletariat | People who work for wages in a society, particularly in the industrial sector |

| provincial | The areas of a nation outside major cities, such as lesser towns, rural areas or colonies |

| upper class | The upper levels of a society, such as royalty, aristocracy and the very wealthy |

| urban | The people, actions and conditions in large cities |

| village | A small agricultural community, usually in a rural area |

| working class | The lower levels of society, whose members must work to survive |

Political systems

| absolutism | Any political system where the ruler or government wields absolute power |

| anarchism | A political system that seeks to abolish the state and create a communal society |

| autocracy | A system where political power is concentrated in the hands of a single person |

| capitalism | An economic system where most companies, land and other resources are privately owned |

| colonialism | A system of claiming, settling, ruling and maintaining one or more colonies (see imperialism) |

| communism | A political-economic system with no state, minimal class differences and economic equality |

| constitutional monarchy | A political system with a monarch whose power is limited and shared with the people |

| democracy | A political system where the government or parts of it are selected by the people |

| divine right | A form of political authority where power is said to be ordained by God |

| fascism | A political system marked by authoritarian rule, nationalism, state and military power |

| feudalism | A medieval socio-political system with a hierarchy of kings, lords, knights and vassals |

| imperialism | A system where a powerful state conquers territories (colonies) for its own gain |

| Marxism | A system or world view based on material factors, inequalities of wealth and class struggle |

| mercantilism | An economic system designed to increase national power by increasing wealth and trade |

| militarism | A system where military needs are prioritised and the military exerts political influence |

| nationalism | An ideology urging loyalty to one’s own country; to put your country first |

| popular sovereignty | A form of political authority where power is derived from the consent of the people |

| socialism | A system where the government rules in the interests of the workers or common people |

| syndicalism | A form of socialism where the workers collectively control their factories or workplaces |

| theocracy | A system where government and laws are determined by religious leaders and teachings |

| totalitarianism | A political system where the power of the state often overrides the rights of individuals |

| welfare state | A system that provides necessities of life to the homeless, unemployed, sick or elderly |

Political concepts

| assembly | A body of people, elected or appointed to form government or make decisions |

| autocracy | A form of government where one person is responsible for decision making |

| constitution | A document defining systems of government and the limits of government power |

| democracy | A political system where government is formed by popular elections |

| divine right | The idea that governments and autocrats derive their power and authority from God |

| elections | The process of voting to select others, usually to form a representative government |

| executive | The branch of government responsible for leadership and day to day decision making |

| government | A system responsible for leadership, making decisions and making laws in a society |

| ideology | A system of ideas and beliefs that shapes one’s views about politics and government |

| legislature | An assembly that exists to pass new laws or review, amend or abolish existing laws |

| parliament | An elected legislature from which an executive government is also formed |

| participation | The involvement of ordinary people in selecting government and in political discourse |

| popular sovereignty | The idea that governments derive their power and authority from the consent of the people |

| representation | A political concept where some individuals act, speak or make decisions on behalf of others |

| sovereignty | The supreme authority of a government, the basis for its power and autonomy |

| state | ‘The state’ describes an organised society and the political system that governs it |

Economic concepts

| capital | The resources needed to produce things, such as land, raw materials and equipment |

| commerce | The business of buying and selling, particularly on a large scale |

| debt | Money owed to another party, usually because it has been previously borrowed |

| deficit | The shortfall that exists when spending is greater than income |

| exports | Resources or goods sold and shipped to another country, which boosts national income |

| finance | Describes the sections of an economy concerned with managing money, such as banking |

| imports | Resources or goods bought and shipped in from another country, depleting national income |

| industry | The production of raw materials and manufactured goods within an economy |

| inflation | An increase in prices for goods and services, reducing the purchasing power of money |

| labour | The people who provide work to enable production or delivery of services; the workers |

| laissez-faire | French for “let it be”; an economy free of trade regulations, tariffs or costs |

| manufacturing | The process of making or producing goods, particularly on a large scale |

| production | The process of making things, particularly things that have additional value |

| profit | Financial reward obtained from business or investment, where income exceeds costs |

| revenue | Money received for normal activities, such as sales (business) or taxation (government) |

| taxation | Money collected from individuals and groups by the government to fund the state |

| trade | The buying or selling of goods, usually in exchange for money |

Words for describing historical cause

| agitated | aroused | awakened | brought about | catalyst |

| developed | deteriorated | encouraged | exacerbated | fuelled |

| generated | incited | inflamed | instigated | kindled |

| led to | long term | motivated | popularised | propagandised |

| prompted | promoted | protested | provoked | radicalised |

| reformed | rocked | roused | set off | short term |

| solicited | sparked | spurred | stimulated | stirred up |

| transformed | triggered | urged | whipped up | worsened |

Words for describing historical effect or consequence

| boosted | catastrophic | consolidated | crippled | decimated |

| demoralised | depleted | disastrous | disbanded | disoriented |

| dispersed | dissolved | divided | drained | elevated |

| emboldened | enriched | exhausted | fatigued | hardened |

| heartened | improved | inspired | mobilised | prospered |

| punished | restored | sapped | scattered | separated |

| stimulated | strained | strengthened | stretched | unified |

| united | unsettled | uplifted | upset | wearied |

Words for describing historical continuity

| blocked | calmed | censored | clamped down | concealed |

| conservative | contained | curbed | deterred | dispersed |

| froze | halted | held back | limited | mollified |

| pacified | oppressed | overpowered | prohibited | quashed |

| quelled | reactionary | regressed | repressed | resisted |

| restored | restrained | restricted | smothered | stabilised |

| stemmed | stunted | subdued | suppressed | wound back |

Words for describing historical significance

| adverse | calamitous | catastrophic | destabilising | destructive |

| devastating | dire | disastrous | essential | expedient |

| far reaching | far sighted | fateful | forerunner | ground breaking |

| healing | important | innovative | meaningful | modernising |

| negative | ominous | opportune | profound | pivotal |

| positive | revolutionary | ruinous | serious | shaking |

| shattering | significant | spear heading | timely | trail blazing |

| transforming | tumultuous | unsettling | uprooting | vital |

Words for evaluating historical sources

| balanced | baseless | biased | convincing | credible |

| deceptive | dishonest | distorted | doubtful | dubious |

| emotive | exaggerated | fallacious | far fetched | flawed |

| honest | imbalanced | impossible | inflated | limited |

| misleading | one sided | overwrought | persuasive | phoney |

| plausible | propagandist | realistic | reasonable | selective |

| sensationalist | skewed | sound | spurious | unrealistic |

| unreliable | untenable | useful | valid | vivid |

Command words for history tasks and activities

| analyse | Examine and discuss the important structure or parts of something |

| annotate | Record written questions, comments or explanations on a document or visual source |

| annotated bibliography | A list of books that contains a note about the content and usefulness of each book |

| argue | Present a case, to express and explain a particular reason or theory |

| brainstorm | Gather and record thoughts and ideas spontaneously, without sorting or evaluating them |

| cite | Refer to an authority or trusted source, as evidence of your information or idea |

| compare | Examine two or more propositions and identify and discuss similarities between them |

| concept map | A visual chart or diagram, using shapes and lines to organise and connect topics or ideas |

| conclusion | The last paragraph in sustained writing, it restates the contention and ’rounds off’ the text |

| contrast | Examine two or more propositions and identify and discuss differences between them |

| critically analyse | Analyse something and offer views and judgements about the merit or value of its parts |

| define | Provide precise meanings and explanations about something |

| describe | Provide a detailed and graphic account of something |

| discuss | Provide a balanced commentary about something, mentioning arguments for and against |

| evaluate | Analyse something and form final conclusions about its value, credibility or merit |

| explain | Provide a clear, straightforward and detailed account of something |

| historiographical activity | A task requiring discussion of historians and their interpretations of a particular topic |

| interpret | Examine something to extract its meaning and express it in your own words |

| introduction | The first paragraph in sustained writing, offering a contention and an outline of the text |

| issue | A topic or question that is open to discussion, debate or dispute |

| justify | Provide clear reasons, grounds and evidence for a particular argument or conclusion |

| outline | Provide a basic overview of something, describing only its main features |

| paraphrase | To describe someone else’s words, statement or meaning, in your own words |

| review | Read or examine something and offer your own thoughts and judgements about it |

| signpost | Use phrases and sentences outlining the direction or structure your writing will take |

| summarise | Briefly describe the main points or attributes of something, without going into much detail |

Citation information

Title: “History words”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/history-words/

Date published: June 3, 2018

Date updated: December 24, 2022

Date accessed: April 12, 2023

Copyright: Content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

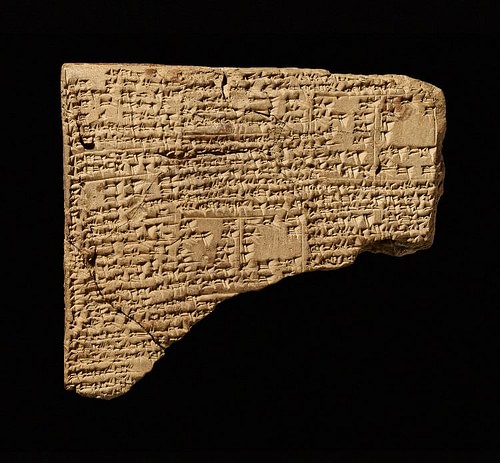

Lexical lists are compilations of cuneiform signs and word readings written on clay tablets throughout Mesopotamia. From the late 4th millennium BCE up to the 1st century CE, scribal communities copied, modified, and passed on these cuneiform lexical lists and preserved them for as knowledge for a variety of purposes. Just as today people pass on and embrace the knowledge of scientific discoveries, lexical lists were the knowledge and intellectual material of the day when cuneiform writing emerged in the 4th millennium BCE. Including unpublished lexical lists, over 15,000 tablets exist. For the duration of the cuneiform lexical tradition, the meaning, purpose, and significance between world lists was in flux and development.

Neo-Assyrian Cuneiform Lexical List The Trustees of the British Museum (Copyright)

Description of Lexical Lists

In the simplest form, lexical lists may be divided into two categories: sign lists and word lists. The first primarily presents an inventory of signs along with their proper use. The second organizes cuneiform by semantics, which is the branch of linguistics and logic concerned with meaning, and is typically written in a thematic organization. Of course, some contain elements of both sign lists and word lists, indicative that we must permit a certain amount of fluidity when attempting to define lexical lists. Over time and with greater cultural interactions, they were further added upon with two columns, and sometimes three, in different languages in order to operate as transmitters of language for future generations. Although this description makes lexical lists seem mundane and pointless, they, in reality, can be used to understand historical developments and reconstruct the cultural landscape and ideas of the ancient Near East.

Brief History of Lexical Lists

In c. 3200 BCE, archaic writing of cuneiform was developed. During this period, the technology of writing was novel. Niek Veldhuis comments on the historical significance of archaic lexical lists: «The invention of a writing system is to be seen in the context of the development of standardized mass production and organized labor» (27). Consequently, a new class of society emerged, namely the scribal class, and lexical lists became a tool for constructing social identity within early scribal communities.

YouTube

Follow us on YouTube!

Moving into the 3rd millennium BCE, cuneiform lexical lists spread unevenly, which prevents strong conclusions from being made. Up to the Old Akkadian and Ur III periods (c. 2230 – 2004 BCE), lexical lists were primarily based in single locations, though not spread across Mesopotamia. In the Old Akkadian and Ur III periods, «the lexical material is reduced to a trickle» (Veldhuis, 142). Thus, for the duration of the 3rd millennium BCE, we only have evidence that lexical lists were primarily tools of authority, power, and leadership, not teaching within scribal communities. Importantly, in both the archaic lexical lists and those within the third millennium, there is great conservativeness, with many of the same texts being copied and written, with minor adjustments.

In the 3rd millennium BCE lexical lists were primarily tools of authority & power, only the Old Babylonian period sees the establishment of a scribal curriculum.

At the dawning of the second millennium, the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000 – 1600 BCE), traditional texts from the archaic period and third millennium began to dwindle and new word lists and sign lists began to emerge. This period is extremely important in reconstructing the development of scribal practices and lexical lists because we see the establishment of an Old Babylonian scribal curriculum. Many of the texts from the archaic period became «teaching texts that introduced pupils to the invented tradition of a glorious Sumerian past» (Veldhuis, 218). Additionally, the new lexical lists, such as grammatical lists, found association with divinatory and mathematical literature rather than the scribal school. Third, we see the emergence of lexical lists oriented towards speculative philology, or the isolation of Sumerian symbols to translate them into Akkadian. This third category for usage of lexical lists is important because it marks the foundation of the social class of scholars. All in all, the developments during this period fit within the broader societal changes, namely the emergence of Babylonian elites.

Transitioning into the International period (c. 1600 – 1000 BCE), the late 2nd millennium, also known as the Late Bronze Age, Middle Babylonian, Kassite, Amarna, or Middle Assyrian periods, «saw an unprecedented spread of cuneiform writing and Babylonian written culture over the entire ancient Near East» (Veldhuis, 226). Reception of lexical lists during the period varied diversely because of different attitudes towards the cuneiform and the lexical tradition. During the International period, lexical lists began to splinter into various traditions, meaning that one could place two of the same lexical lists side by side and find variations. Most significant in terms of reception of lexical lists is Assyria’s, who reacted with conservatism and embraced their Babylonian cultural heritage.

Love History?

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Overlapping with the International period, the early history of Assur, the heart of ancient Assyria, treated the Babylonian cultural heritage like holy writ, thereby redefining the character of scribal practice. With the acquisition and high value of this intellectual tradition, lexical lists became the literary technology in the Middle Assyrian period, which justified and cemented Assyria into a respected and ancient tradition. The fluidity of lexical lists during this period decreased and became objectified, frozen in time as a sort of canon. They were considered so because, to a certain extent, lexical lists symbolized primordial knowledge and «came to play a role in the management of power and legitimation of a world empire» (Veldhuis, 391).

Babylonian Cuneiform Lexical List The Trustees of the British Museum (Copyright)

Finally, in the Neo- and Late Babylonian period, scholarship, and thereby lexical lists, became the property and responsibility of temples and elite families in charge. Many of these late lexical lists include dedication prayers, indicative that writing and education were closely associated with temples and political leadership. Additionally, unlike the Old Babylonian period, lexical traditions ceased becoming the primary focus of scholarship; rather they became integral to further other areas of scholarship, such as celestial sciences and horoscopy.

Unfortunately, many lexical lists which possibly existed in the 1st century CE are now absent because the scribes chose to write with a different cultural medium brought by Hellenization, namely writing on parchment or other surfaces rather than clay tablets.

Final Remarks

From the archaic period up to the 1st century CE, roughly 3,300 years, the tradition of lexical lists developed into a source of knowledge and a political legitimation tool. Yet, during this long period of time, lexical lists maintained an important position within the cultural landscape because they represented the increasingly valuable technology of writing, a technology which eventually became associated with primordial knowledge. Through a lengthy reception history, many of the lexical lists from the archaic period were still utilized in the 1st century CE, a remarkable time for any literature to be remembered and well-received. In a world that takes writing and reading for granted, though, we would do well to remember that scribal practice, writing, and reading are all technologies and potential mediums for social, political, and religious change.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

There are many word lists for general and academic English study. This page describes

the most important ones, first giving an

overview of the different types of word list, then presenting a

more detailed summary of individual lists.

The summary contains links to other pages on the site which have more detail of each list and (often) a complete copy of the list itself.

There is a companion page in this section which gives

information on why word lists are important (and tips on how to use them).

[Note: Links to other pages are in blue, links to other parts of this page are in red.]

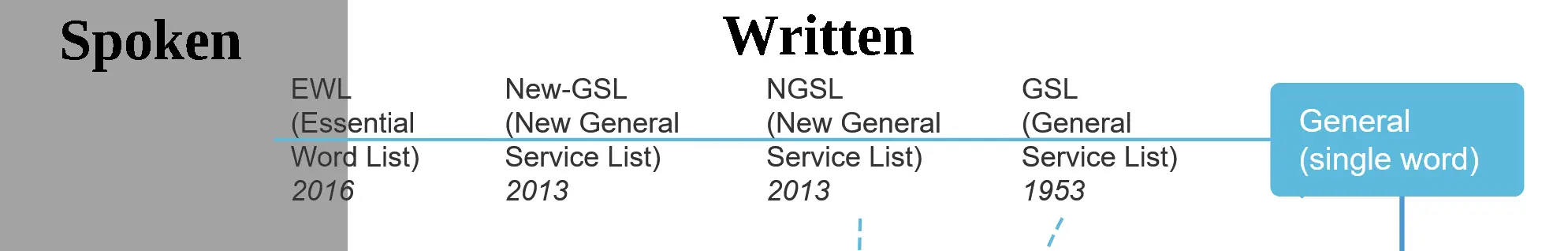

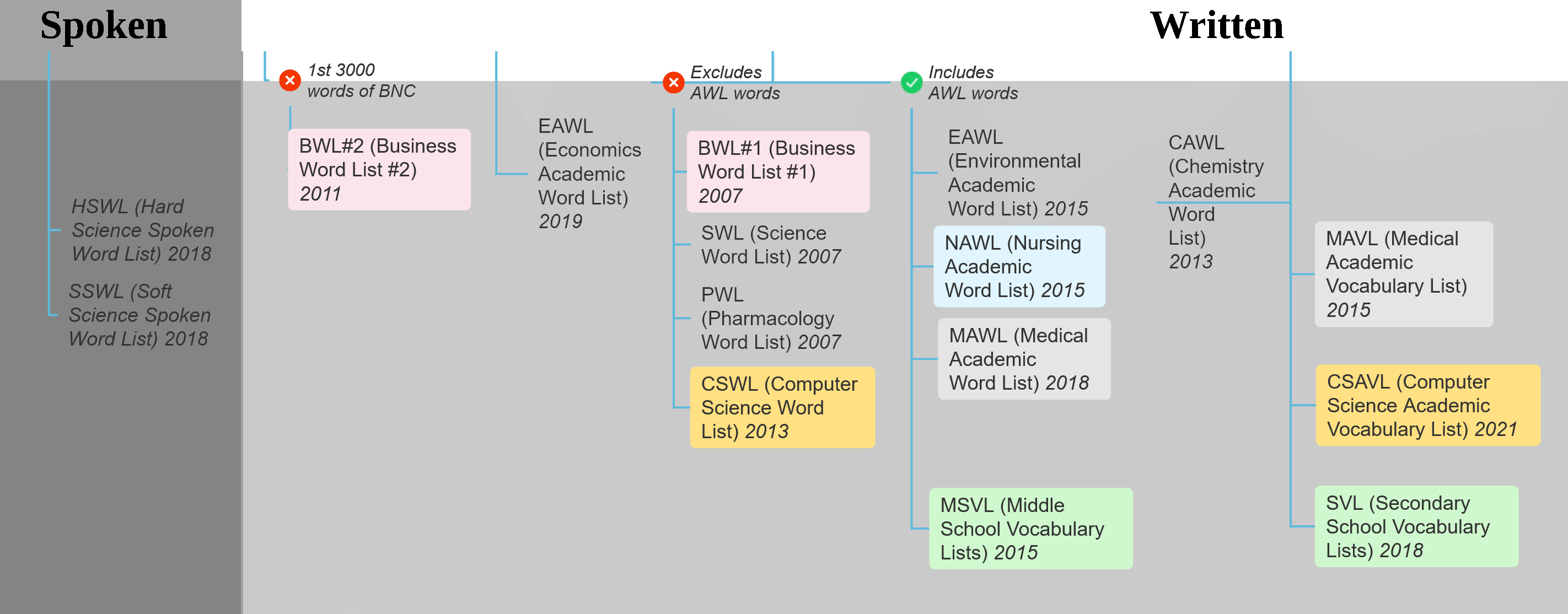

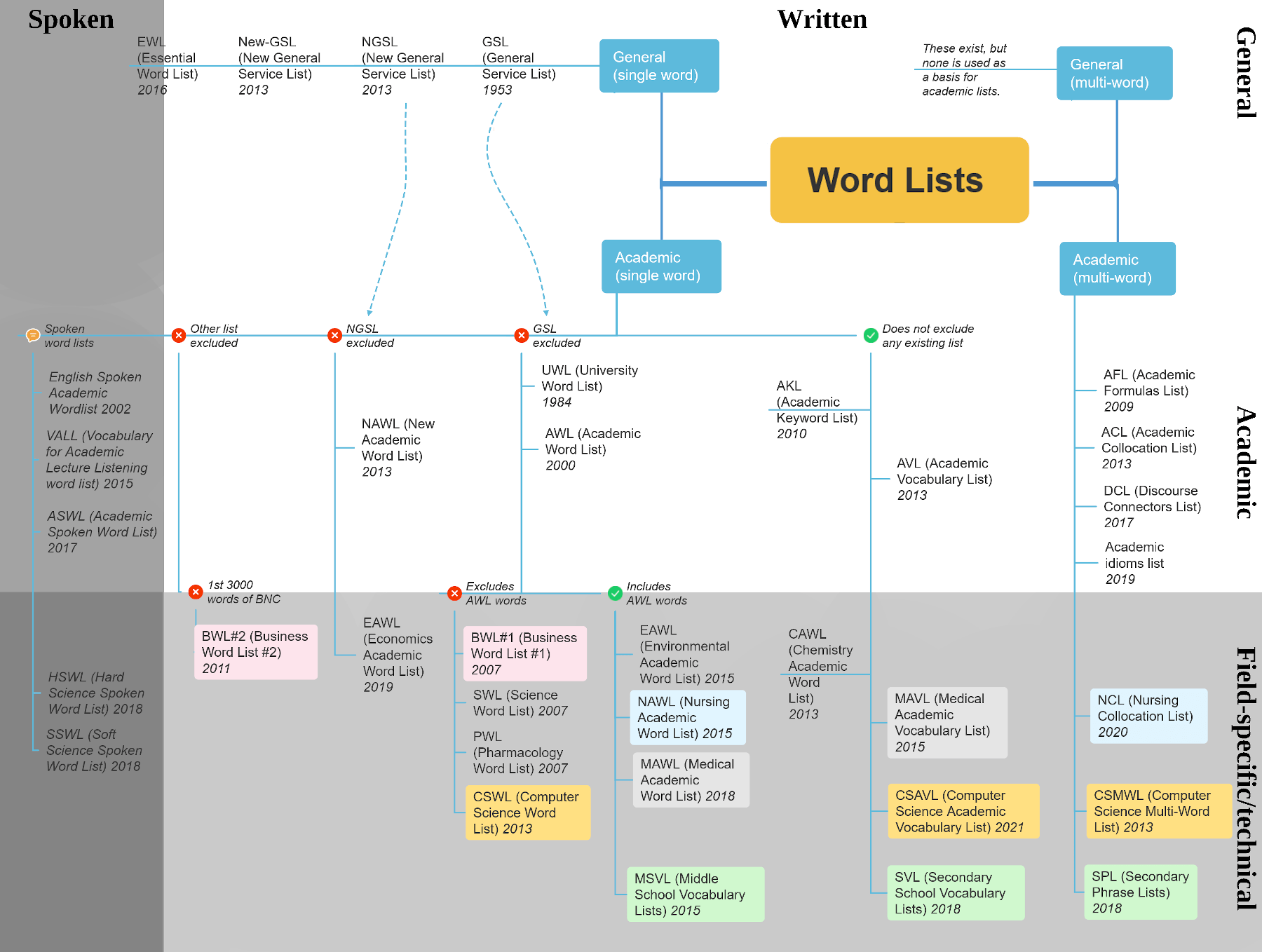

Types of word list

Word lists can be divided into three types, namely

general word lists and

academic word lists, although as will be explained below, academic lists can be sub-divided into

general academic lists and

field-specific (i.e. subject-specific) academic lists.

An additional way to classify word lists is those which contain only single words (the majority of the lists are this type), and

multi-word lists. A final way to classify lists is written vs. spoken. Most of the lists that exist are

for written English, though many of the multi-word lists include both a spoken and written component.

General word lists (single words)

Interest in word lists began with studies of core or general vocabulary, that is, words having high frequency across a wide range of

texts. The first general word list to have important use in language study was the

General Service List (GSL), created by Michael West in 1953.

This list has been used to design EFL materials and courses, and, despite its age, it is probably still the most widely used list of general vocabulary.

Originally consisting of 2000 words (called headwords) and their corresponding word families, it was revised in 1995 by Bauman and Culligan,

with an increase in the number of headwords from 2000 to 2284.

One criticism of the GSL is its inclusion of too many low frequency words, some of which are a product of its age (e.g. shilling, headdress, cart, servant) while

excluding more recent vocabulary (e.g. computer, television, Internet). A second criticism is that it uses word families. The assumption behind the use of

word families is that once one word is known, other members of the family can be easily recognised; however, this may not always be the case. Examples of

distantly related word family pairs in the GSL are: please/unpleasantly, part/particle and value/invaluable. Additionally, some word

forms are used more frequently than others, and the inclusion of less frequent forms adds an unnecessarily burden to the learning load of students.

These criticisms have led to the creation of two updated versions of the list, both devised in 2013, both called the New General Service List.

Both lists use inflected forms and variant spellings (called lemmas), rather than extended word families.

The first, abbreviated to

NGSL, was developed by Browne, Culligan and Phillips. It is a list of 2801 words which give over 90% coverage.

It was generated from a corpus of 273 million words, 100 times larger than that used for the GSL.

The second list, abbreviated to

new-GSL, was devised by Brezina and Gablasova from a corpus of over 12 billion words.

It consists of 2494 words and gives around 80% coverage.

General word lists (multi-word)

The above are all single word lists. There are several multi-word lists for general vocabulary, such as the

First 100 Spoken Collocations (First 100) by Shin and Nation (2008), and the Phrasal Expressions List (PHRASE List) by Martinez and Schmitt (2012). However,

since none of these is used as a basis for academic word lists, in contrast to the general lists given above, they are not explained here in detail.

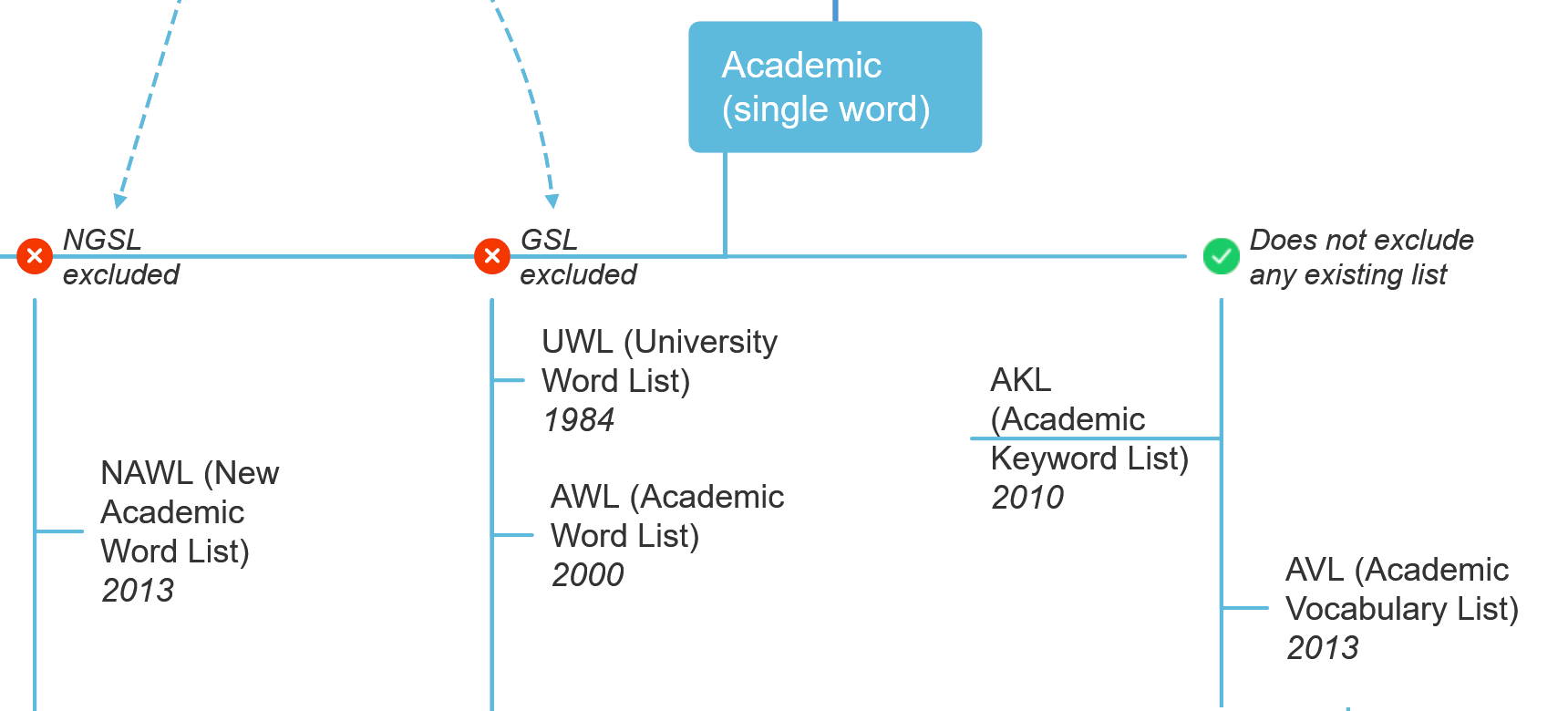

Academic word lists (single words)

Researchers have long been interested in defining and isolating academic vocabulary, and there have been many attempts to devise

lists which are of general use to students of academic English.

The first widely used academic word list was the

University Word List (UWL),

created in 1984 by Xue and Nation. It comprises 836 word families, divided into levels based on frequency.

It excludes words from the GSL, and gives 8.5% coverage of academic texts. It was developed by combining four existing lists.

A major update to the UWL came in 2000, when Averil Coxhead, of the University of Wellington, devised the

Academic Word List (AWL). This list

has been hugely influential and is perhaps the most widely known and used academic word list. Like the UWL, it comprises word families and is

divided into levels based on frequency. It gives similar coverage, around 10% of texts; however, it does so using far fewer word families, 570 in total.

Like the UWL, it excludes words from the GSL. It was devised in a more systematic way, using a corpus of texts from a range of academic disciplines.

Although the AWL is still widely used, it has received criticism in a number of areas. One criticism is that it is based on the

GSL, which is a very old list, dating from 1953. A second criticism is that, like the GSL, it uses word families, with the same problems as mentioned for

the GSL above.

In response to these criticisms, other academic word lists have been created. One of these is the

Academic Keyword List (AKL), developed by Paquot in 2010. This

consists of 930 words which appear more frequently in academic texts than non-academic ones, a tendency called keyness,

which leads to the name of the list.

A second list is the

New Academic Word List (NAWL) by

Browne, Culligan and Phillips. This list responds to the criticisms of the AWL by using lemmas rather than word families, and by basing itself on a more

updated general service list, the

NGSL, created by the authors at the same time, in 2013.

A third updated list is the

Academic Vocabulary List (AVL), developed by Gardner and Davies in 2013. This list, which is also lemma-based,

selects academic words by considering their ratio in academic versus non-academic texts, with words needing to occur 1.5 times as often in the

academic texts as in non-academic ones. This is similar to the approach used to devise the AKL (above), and in contrast to lists like the AWL and NAWL which

exclude an existing general service list. In addition, the authors considered the range of words in the academic disciplines used in their corpus,

the dispersion, and discipline measure, which required that words could not occur more than three times the expected frequency in any of

the disciplines. This approach has been influential in the development of other,

field-specific lists, as well as some

technical lists, as explained below.

There are several lists specifically for academic spoken English (as distinct from the spoken components of the multi-word lists, below).

These include the English Spoken Academic Wordlist, devised by Nesi in 2002,

the Academic Spoken Word List (ASWL), devised by Dang et al. in 2017, and

the Vocabulary for Academic Lecture Listening word list (VALL), devised by Thompson in 2015.

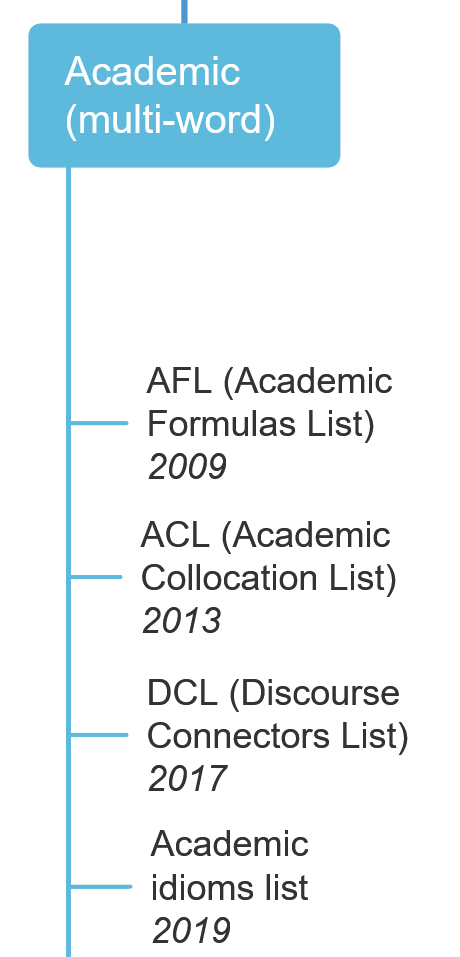

Academic word lists (multi-word)

Focusing exclusively on single words can lead learners to overlook valuable multi-word constructions which are commonly used in academic English.

For example, while use of the word thing is generally considered to be poor

academic style, it occurs in several phrases used by expert writers, such as

the same thing as and other things being equal.

Several multi-word lists have been developed for academic English. One is the

Academic Formulas List (AFL), devised by Simpson-Vlach and Ellis in 2009. This list

gives the most common formulaic sequences in academic English, i.e. recurring word sequences three to five words long.

There are three separate lists: one for formulas that are common in both academic spoken and written English (the ‘core’ AFL),

one for spoken English, and one for written English.

Another multi-word list is the

Academic Collocation List (ACL), developed by Ackermann and Chen in 2013. The ACL

contains 2469 of the most frequent and useful collocations which occur in written academic English.

A third list is the

Discourse Connectors List (DCL), devised by Rezvani Kalajahi, Neufeld and Abdullah in 2017. This list

classifies and describes 632 discourse connectors, ranking them by frequency in three different registers (academic, non-academic and spoken).

More recently, there is the

Academic idioms list, developed by Miller in 2019. This gives 170 idioms which are common in spoken academic

English, and 38 which are frequently used in written academic English.

Field-specific academic word lists (single words)

Academic word lists such as the AWL are designed to be used by students of all disciplines. Researchers have found, however, that the AWL and other lists

provide varied coverage in different subject areas. For example, the AWL provides 12.0% coverage of the Commerce sub-corpus used to derive the list,

but only 9.1% for the Science sub-corpus (with only 6.2% for Biology).

Additionally, words in the AWL (and similar lists) occur with different frequencies in different disciplines.

For example, words such as legal, policy, income, finance and legislate,

which all fall in the first (most frequent) sublist of the AWL, may be common in Business or Finance,

but are very infrequent in disciplines such as Chemistry.

Words also have different collocations and meanings across different subject areas. Examples are base, which has a special meaning in Chemistry,

and bug, which has a different meaning in Computer Science than in general English.

Researchers have therefore become increasingly interested in field-specific (i.e. subject-specific) academic lists, in disciplines ranging

from science to business to medicine. These are generally not

technical word lists, since they are intended to comprise academic (sub-technical) vocabulary.

However, not all of them set out to exclude technical words (some actually set out to include them), and even for those that do,

the line between academic and technical words is often blurred.

Broadly speaking, there are three approaches used by researchers when devising field-specific academic lists.

The first of these is to use the GSL and AWL as a starting point, and to devise a third list which supplements the other two. These lists

exclude GSL and AWL words, and, since they are based on word family lists, also comprise word families.

These lists usually replace the ‘A’ of ‘AWL’ with a subject specific letter.

Examples are the

SWL (Science Word List), the

BWL#1 (Business Word List #1), the

Pharmacology Word List and the

CSWL (Computer Science Word List).

The second approach is to assume that learners are already familiar with general vocabulary and to devise a second list which replaces

other academic lists such as the AWL or NAWL for specific subject areas. As such, these lists exclude the GSL (or NGSL), but do not

exclude any other lists such as the AWL.

These lists usually add the subject letter before ‘AWL’ to derive their name.

Examples are the

MAWL (Medical Academic Word List) and the

NAWL (Nursing Academic Word List), both of which exclude the GSL and are word family lists (like the GSL), and the

EAWL (Economics Academic Word List), which excludes the NGSL and is a lemma-based list (like the NGSL).

The third approach is to devise a single, completely independent list, which includes words based on ratio, dispersion, and other measures, in a similar

way the AVL. These lists, which are usually lemma-based, tend to use ‘AVL’ in their name, preceded by an abbreviation for the subject. Examples are the

MAVL (Medical Academic Vocabulary List) and the

CSAVL (Computer Science Academic Vocabulary List). The

Chemistry Academic Word List (CAWL), although it broadly uses

the same approach, uses word families, and also predates the creation of the AVL, and does not follow the same naming pattern.

There are two further lists which deserve mention here. Both have been developed using the same principles as the lists above; however, they

are intended for school-age rather than university students.

The first is the

Middle School Vocabulary Lists (MSVL). These are a series of five lists developed in 2015 by Greene and

Coxhead, along similar lines to Coxhead’s earlier AWL, i.e. by excluding the GSL and working with word families. However, this list is

intended not for students at or preparing for university, but middle school students, and covers technical rather than purely academic vocabulary.

The lists cover the following subjects: English, Health, Mathematics, Science, and Social Science/History.

Another is the

Secondary Schools Vocabulary Lists (SVL). Developed in 2018 by Green and Lambert, the SVL are a series of lists of

discipline-specific words for secondary school education, covering eight core subjects: Biology, Chemistry, Economics, English, Geology, History,

Mathematics, and Physics. The lists were devised using methods similar to those used to create the

AVL and the

MAVL, which are lemma-based lists which consider measures such as range and dispersion along with word frequency.

The lists also include word family versions, as well as collocation lists. The SVL are designed to help students in secondary schools improve their

disciplinary literacy.

There are at least two field-specific academic lists of spoken English, both devised by Dang in 2018. They are the Hard Science Spoken Word

List (HSWL), and the Soft Science Spoken Word List (SSWL).

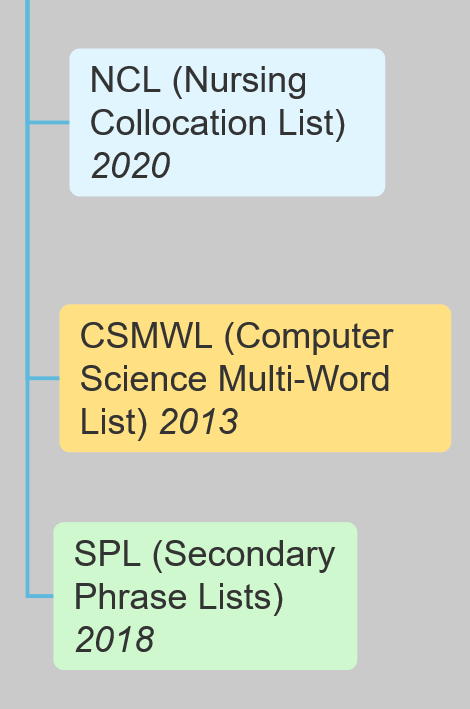

Technical word lists (multi-word)

There have been some attempts to create discipline-specific multi-word lists, using principles employed in the creation of academic lists.

One is the Computer Science Multi-Word List (CSMWL), created by Minshall at the same time as the

Computer Science Word List (CSWL). However, it comprises only 23 items.

Another example is the

Secondary Phrase Lists (SPL), developed in 2018 by Green and Lambert, who also developed the SVL (above).

This is a series of lists, for the same eight subjects as covered by the SVL, presenting noun-noun, adjective-noun, noun-verb, verb-noun and verb-adverb

collocations.

A third, more recent example is the

Nursing Collocation List (NCL), developed in 2020 by Mandić and

Dankić. It comprises 488 collocations which occur frequently in nursing journal articles.

Summary

The following image, and table below, provide an overview of the major word lists. Spoken word lists are only included in the table

(in italics). All word lists (except spoken ones) are explained in more detail later. Note: there is a higher resolution copy of the following image in the

infographics section.

| Single word | Multi-word | |

| General |

• GSL (General Service List) 1953 • NGSL (New General Service List) 2013 • New-GSL (New General Service List) 2013 |

These exist, but none are used as a basis for academic lists. |

| Academic |

• UWL (University Word List) 1984 • AWL (Academic Word List) 2000 • AKL (Academic Keyword List) 2010 • NAWL (New Academic Word List) 2013 • AVL (Academic Vocabulary List) 2013 • English Spoken Academic Wordlist 2002 • ASWL (Academic Spoken Word List) 2017 • VALL (Vocabulary for Academic Lecture Listening word list) 2015 |

• AFL (Academic Formulas List) 2009 • ACL (Academic Collocation List) 2013 • DCL (Discourse Connectors List) 2017 • Academic idioms list 2019 |

| Field-specific/ technical |

• SWL (Science Word List) 2007 • BWL#1 (Business Word List #1) 2007 • PWL (Pharmacology Word List) 2007 • MAWL (Medical Academic Word List) 2008 • AgroCorpus List 2009 • BEL (Basic Engineering List) 2009 • BWL#2 (Business Word List #2) 2011 • CSWL (Computer Science Academic Word List) 2013 • CAWL (Chemistry Academic Word List) 2013 • MAVL (Medical Academic Vocabulary List) 2015 • NAWL (Nursing Academic Word List) 2015 • EAWL (Environmental Academic Word List) 2015 • EAWL (Economics Academic Word List) 2019 • CSAVL (Computer Science Academic Vocabulary List) 2021 • MSVL (Middle School Vocabulary Lists) 2015 • SVL (Secondary School Vocabulary Lists) 2018 • HSWL (Hard Science Spoken Word List) 2018 • SSWL (Soft Science Spoken Word List) 2018 |

• CSMWL (Computer Science Multi-Word List) 2013 • SPL (Secondary Phrase Lists) 2018 • NCL (Nursing Collocation List) 2020 |

References

Granger, S., and Larsson, T. (2021), ‘Is core vocabulary a friend or foe of academic writing? Singleword vs multi-word uses of THING’, Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 52 (2021) 100999.

Hyland, K. and Tse, P. (2007). ‘Is There an “Academic Vocabulary”?’, TESOL QUARTERLY, Vol. 41, No. 2, June 2007.

Radmila Palinkašević, M.A. (2017), ‘Specialized Word Lists — Survey of the Literature — Research Perspective’, Research in Pedagogy, Vol. 7, Issue 2 (2017), pp. 221-238.

Therova, D. (2020), ‘Review of Academic Word Lists’, The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, Volume 24, Number 1.

Detailed summary of individual lists

Below is more detail about the lists above. The lists are sorted into the following categories:

- General (core) vocabulary single word lists (3 lists)

- Academic single word lists: general purpose (5 lists)

- Academic single word lists: field-specific (14 lists)

- Technical single word lists (2 lists)

- Academic multi-word lists (4 lists)

- Technical multi-word lists (3 lists)

General (core) vocabulary single word lists

The following gives a more detailed summary of the general word lists mentioned on this page. Blue links

are links to other pages (with even more detail, and, often, a copy of the full word list).

| Word list | About |

| General Service List (GSL) |

Author: West (1953) — Size: 2284 word families — Originally a list of the 2000 most frequent word families in English, covering around 80% of various types of texts. Further divided into the 1K (first 1000 words) and 2K (second 1000). Used as the basis for many graded readers and other ESL/EFL materials. The list was revised in 1995 by Bauman and Culligan, and their revision, which is the version most commonly used, contains 2284 words. — Examples: the, be, of, and, a, to, in, he, have, it |

| New General Service List (NGSL) |

Author: Browne, Culligan and Phillips (2013) — Size: 2801 words — The New General Service List (NGSL), an update of the GSL, is a list of 2801 words which comprise the most important high-frequency words in English, giving the highest possible coverage with the fewest possible words. Not to be confused with the new-GSL (below), also developed in 2013, the NGSL gives over 90% coverage of the corpus used. The NGSL was generated from a corpus of 273 million words, 100 times larger than that used for the GSL. Presents only inflected forms, not word families. Used as the basis for other lists, e.g. NAWL. Has yet to have the same influence as the GSL. — Examples: the, be, and, of, to, a, in, have, it, you |

| New-General Service List (new-GSL) |

Author: Brezina and Gablasova (2013) — Size: 2494 words — The new-General Service List (new-GSL), an update of the GSL, is a list of 2494 words drawn from four different corpora with a total size of 12 billion words. Not to be confused with the NGSL (above), also developed in 2013, the new-GSL gives around 80% coverage of the corpora used, similar to the GSL, though with fewer words overall, 2494 compared to approximately 4100 for the GSL. The 2494 words comprise a core list of 2122 words, which had a similar rank in all four corpora, plus 378 words which were common in the two more recent corpora. Like the NGSL, it uses lemmas i.e. inflected forms, not word families. Does not (yet) appear to have been used as the basis for other lists, and is yet to have the same influence as the GSL. — Examples: the, be, of, and, a, in, to, have, that, to |

Academic single word lists: general purpose

The following are the general academic word lists mentioned earlier.

| Word list | About |

| University Word List (UWL) |

Author: Xue and Nation (1984) — Size: 836 word families — One of the first widely used academic word lists, the UWL contains 836 word families divided into levels based on frequency. It excludes words from the GSL, and gives coverage of 8.5% of academic texts. Now largely replaced by the AWL. — Examples: alternative, analyze, approach, arbitrary, assess, assign, assume, compensate, complex, comply |

| Academic Word List (AWL) |

Author: Coxhead (2000) — Size: 570 word families — Perhaps the most widely known and used academic word list, the AWL is a list of 570 word families that are not included in the GSL but which appear frequently in academic texts, across a range of disciplines. Divided into 10 sublists based on frequency. It was designed to be an improvement on the UWL, and covers around 10% of words in academic texts: a similar amount to the UWL, but using far fewer word families. — Examples: analyse, approach, area, assess, assume, authority, available, benefit, concept, consist |

| Academic Keyword List (AKL) |

Author: Paquot (2010) — Size: 930 words — The Academic Keyword List (AKL) consists of 930 words which appear more frequently in academic texts than non-academic ones. This tendency is called keyness, which leads to the name of the list, since it identifies keywords in academic (vs. non-academic) texts (the AVL, below, uses a similar principle to select words). As such, the AKL does not exclude words from the GSL. 49.6% of words in the AKL appear in the GSL, 38.7% in the AWL, while 11.7% appear in neither list. — Example words: ability, absence, account, achievement, act, accept, account (for), absolute, above, according to |

| New Academic Word List (NAWL) |

Author: Browne, Culligan and Phillips (2013) — Size: 963 words — The New Academic Word List (NAWL) is a list of words that frequently appear in academic texts, but which are not contained in the New General Service List (NGSL) (by the same authors). The NGSL and NAWL in combination give 92% coverage of words (86% for the NGSL and 6% for the NAWL). The NAWL differs from the AWL in that it is more up-to-date, using the NGSL rather than the much older GSL as a basis. Additionally, it uses only inflected forms or variant spellings of words, rather than whole word families, meaning that although it has more headwords than the AWL (963 compared to 570), it has fewer word forms overall (2604 compared to 3112). — Example words: repertoire, obtain, distribution, parameter, aspect, dynamic, impact, domain, publish, denote. |

| Academic Vocabulary List (AVL) |

Author: Gardner and Davies (2013) — Size: 3015 words — The AVL is a list of 3015 academic words derived from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). The list excludes general high-frequency words as well as subject-specific (technical) words, though not by directly excluding any existing list. Key features of the list are ratio (words needed to occur 1.5 times as often in academic texts as in non-academic ones), range (words needed to occur frequently in at least seven of nine academic disciplines), dispersion (words needed to be evenly dispersed among the disciplines) and discipline measure (words could not occur more than three times the expected frequency in any of the disciplines). Like the NAWL and in contrast to the AWL, the AVL is based on words and inflected forms, not word families. — Example words: study, group, system, social, provide, however, research, level, result, include. |

Academic single word lists: field-specific

The following are the field-specific lists mentioned earlier.

| Word list | About |

| Science Word List (SWL) |

Author: Coxhead and Hirsh (2007) — Size: 318 word families — The Science Word List (SWL) provides a list of 318 word families which do not occur in the GSL or AWL but which occur with reasonable frequency and range in written science texts. The authors found that the GSL and AWL in combination give only 80% coverage of science texts, compared to 86.7% for Art, 88.8% for Commerce and 88.5% for Law. The 318 word families in the SWL make up for this shortfall, and provide an extra coverage of 3.79% of the science corpus used to derive the list. In comparison, the SWL gives only 0.61% coverage of an Arts corpus, 0.54% for Commerce and 0.34% for Law, demonstrating that it is a true science list. The SWL is divided into sublists based on frequency, in a similar way to the AWL. It contains 6 sublists, with the first 5 each containing 60 word families, and the last containing 18. — Example words: cell, species, acid, muscle, protein, molecule, nutrient, dense, laboratory, ion. |

| Business Word List #1 (BWL#1) |

Author: Konstantakis (2007) — Size: 560 word families — This is the first of two lists called Business Word List (BWL); the second is considered later. To compile the list, the author used a corpus of 33 popular Business English course books published between 1986 and 1996. The list consists of 560 word families, comprising 480 word families selected according to range (needed to occur in at least five of the text books), supplemented by a further 80 word families selected for frequency (needed to appear at least 10 times). The list excludes GSL and AWL words, and therefore provides a third, more specialised and business-oriented list for students. The BWL provided 2.79% coverage of the texts. A separate list of common abbreviations was compiled, which added a further 0.30% coverage. These two lists, together with the GSL and AWL, provided 93.47% coverage, although the author noted that, if proper names and nationalities were included (e.g. London, Mexican), the coverage reached 95.65%, which is above the 95% minimum comprehension threshold. The list is presented in alphabetical order, without frequencies. — Example words: above-mentioned, accessories, acid, adverse, aerospace, after-sales, agenda, aggressive, aircraft, airline. |

| Pharmacology Word List (PWL) |

Author: Fraser (2007) — Size: 601 word families — The PWL is intended to provide a list of words which are common in the field of pharmacology, but which are not contained in the GSL or AWL. The PWL gives around 13% coverage of pharmacology journal articles, and 15% coverage of pharmacology textbooks. — Example words: abbreviation, abnormality, abolish, absorb, abuse, accumbens, acetonitrile, acetate, acetylcholine, acid. |

| Medical Academic Word List (MAWL) |

Author: Wang, Liang, and Ge (2008) — Size: 623 word families — The Medical Academic Word List (MAWL) was developed from a study of a 1.09 million-word corpus of medical research articles from online resources. It contains 623 word families, and has a coverage of 12.24% of words in the corpus. The MAWL was developed in a similar way to the AWL (Academic Word List), by first eliminating words from the GSL (General Service List). In addition, members of the word family needed to occur in at least half of the 32 subject areas of the corpus, and occur at least 30 times in the corpus. It provides an alternative to the AWL for medical students. — Example words: cell, data, muscular, significant, clinic, analyze, respond, factor, method, protein. |

| AgroCorpus List |

Author: Martínez, Beck, and Panza (2009) — Size: 92 word families — The AgroCorpus List is a subset of the AWL, and consists of the word families that were found to be most frequent in an 826,416-word corpus of agriculture research articles. — Example words: environmental, accumulation, region, variation, chemical. |

| Basic Engineering List (BEL) |

Author: Ward (2009) — Size: 299 words — The Basic Engineering List (BEL), developed from a corpus of 250,000 words from 25 engineering textbooks, is intended to serve as a foundation for students in reading English language engineering textbooks. The list is purposely short and non-technical in nature, and focuses on word types rather than lemmas or families in order to encourage a focus on individual words. — Examples words: system, calculate, value, flow, process, column, factors. |

| Business Word List #2 (BWL#2) |

Author: Hsu (2011) — Size: 426 word families — This is the second of two lists called Business Word List (BWL); the first is considered above. This BWL gives 426 word families which occur frequently in business texts, but which are not general words. This list used a different approach to other specialist lists, by excluding the first 3000 word families from the BNC (British National Corpus), rather than excluding other word lists. The author used a corpus which consisted of business research articles across 20 business subject areas. The word families were chosen by range and frequency in the corpus and accounted for 5.66% of words. The words in the BWL are listed according to which 1000 word section of the BNC they appear in (BNC 4th 1000, BNC 5th 1000, etc.), then by frequency in the business corpus. Range (number of articles they occur in) is also given. As such, this BWL is more detailed than the first one. — Example words: asset, audit, statistic, review, transact, network, database, acquire, interact, construct |

| CSWL (Computer Science Word List) |