1. Word Wall

To help your students get more engaged in vocabulary development, you need to nurture word consciousness. This means raising students’ awareness of, and interest in all sorts of words and their meanings.

A Word Wall can help you achieve this. This is a collection of words that are displayed in large visible letters on a wall, bulletin board, or other display surfaces in a classroom.

Source: ELL STRATEGIES & MISCONCEPTIONS

So, set this wall and encourage your students ‘to walk the wall’ and hang their favourite words, new or unknown, on it.

Then, invite their classmates to add sticky notes with pictures or graphics, synonyms, antonyms, or related words. Then, student partners walk along the wall to quiz each other on the words (Graves & Watts-Taffe,2008).

Use the Word Wall one or more times a week. You’ll help your students make connections between new and known words.

Since this is an ongoing activity during the whole year, you can keep observational notes of those students who are posting, responding to their words and those who are not adding words to the wall.

This will help you better understand what your students need to expand their vocabulary.

2. Word Box

Word Box is one of the strategies for teaching vocabulary. This is a weekly strategy that can help students retain and use words more effectively.

Students select words to submit to the word box on Friday. These are words they find interesting or ones they want to understand better. They either use the word in their own sentence or take the same sentence where this word was found.

Then, select five words to teach the following week.

Monday: Introduce the five words in context, explain them, then tack them to the Word Wall.

Tuesday: Ask students to create a non-linguistic representation of the words.

Wednesday: Discuss the meaning of the words allowing think-pair-shares.

Thursday: Ask students to write sentences using those words.

Friday: This is the day to assess students’ learning of the five words using this activity.

Ask one student to answer fill-ins for five words. Give students three cards that can hold up: green cards show they agree with the student’s answer, yellow they are unsure and red ones they disagree.

For assessing, use a checklist with the vocabulary running horizontally across the top margin and the class list running vertically down the side. (Adapted from Grant et al., 2015, p.195)

3. Vocabulary Notebooks

Ask your students to maintain vocabulary notebooks throughout the year where they write the meaning of the new words.

You can introduce a new word each week and work together with students to explore its meaning. Then, ask them to sketch a picture to illustrate the word and present their drawings to the class at the end of the week.

Another way to use vocabulary notebooks :

Students create a chart. The first column indicates the word, where it was found, and the sample sentence in which it appeared.

The other columns depend on your students’ needs.

You can include a column for meaning ( where students define the word or add a synonym), for word parts and related word forms (where they identify the parts and list any other words related to it), a picture, other occurrences (if they have seen or heard this word before, they describe where) and for practice or how they used this word. (Lubliner, 2005)

4. Semantic Mapping

These are maps or webs of words that can help visually display the meaning-based connections between a word or phrase and a set of related words or concepts.

Teach your students how to use semantic mapping. Pick a word you intend to explain, draw a map or web on the board ( or on Zoom whiteboard or any digital tool in case you’re teaching online) and put this word in the centre of the map. Then, ask students to add related words or phrases similar in meaning to the new word. (see the example below)

Source:weebly.com

5. Word Cards

Word cards can help students review frequently learned words and so improve retention.

On one side of the card, students write the target word and its part of speech (whether it’s a verb, noun, adjective, etc.).

On the top half of the other side, they write the word’s definition (in English and/ or a translation). They also write an example and a description of its pronunciation. The bottom half of the card can be used for additional notes once they start using the word.

Ask students to add more information about the word each time they practise or observe it (sentences, collocations, etc.).

Yet, advise them not to add too much information in order to facilitate more reviewing the cards.

Devote regularly class time for students to bring their word cards to class. Involve them in activities such as describing the new words, quizzing one another, categorizing them according to subject or part of speech.

Also, show your students how to store and organize those cards. This is, for instance, by putting them into a box with the categories they select or ordering them in terms of difficulty. (Schmitt & Schmitt, 2005)

6. Word Learning Strategies

Our students often have only partial knowledge of the words they learn in the classroom. This is so since a word can have different meanings which they may not be familiar with.

Therefore, teaching students word learning strategies is important to help them become independent word learners. This is by teaching, modelling and providing a variety of strategies that serve different purposes.

Here are some examples of word-learning strategies.

a) Using word parts

Breaking words into meaningful parts facilitates decoding. So, studying words’ parts can help students guess the meaning of new words from context.

There are three basic ways that word parts are combined in English: prefixing, suffixing, and compounding.

Teach those parts. But, focus on the most occurrent ones.

Providing explanations about their use and meanings with illustration is necessary. Yet, it is still not enough.

You need to provide opportunities for students to experiment with word-building skills.

For instance, you can hand out a list of productive prefixes and have students compile a list of words using them. Then, ask them to compare the function of the prefixes in the various examples.

However, consider your students’ level since word parts are more useful to students with larger vocabularies. For instance, a student who doesn’t know the meaning of the adjective content cannot guess the word discontent.

Remember also that learning word parts is an ongoing process. So, encourage your students to continue experimenting with them. (Zimmerman, 2009a)

b) Asking questions about word

Knowing a word means knowing about its many aspects: its meaning(s), collocations, grammatical function, derivations, and register.

So, you can encourage your students to explore a new word’s meaning(s) by asking them to address detailed questions about those features and answer them.

Students will ask questions like these :

• Are there certain words that often occur before or after the word ? (collocation)

• Are there any grammatical patterns that occur with the word ? (grammar).

• Are there any familiar roots or affixes for this word ? (word parts)

• Is the word used by both men and women? (register/appropriateness)

• Is the word used in both speaking and writing?

(register/appropriateness)

• Could it be used to refer to people? Animals?Things? (meaning)

• Does it have any positive or negative connotations? (meaning) (Zimmerman,2009a)

c) Reflecting

When students learn new words it does not necessarily mean they’ll use them. Students may avoid using words in writing because they are unsure of the spelling. When they speak, they may not be willing to use certain words as they roughly understand them in context.

Encouraging students to self-assess their knowledge of each new word they learn can help them focus on areas needing practices. Here is an example of a self-assessment scale students can use.

Besides these 6 engaging strategies for teaching vocabulary, here are some essential tips to follow while using them :

1) Identify the potential list of words to be taught. Keep the number of words to a minimum (three to five words in one lesson) to ensure there is ample time for in-depth vocabulary instruction, yet enough time for students to practise them.

2) Expose students to multiple contexts in which the new words can be used. This will support them to develop a deeper understanding of these words and how they’re used flexibly.

You can do so by giving students frequent opportunities to hear the meaning of the words, read content where these words are included, and also use them in speaking and writing.

3) Encourage extensive reading because this gives students repeated or multiple exposures to words and is also one of the means by which students see vocabulary in rich contexts.

So, for rich vocabulary development, use a variety of strategies for teaching vocabulary and provide the necessary support and guided practice. Besides, assess vocabulary learning and encourage students to learn more words outside the classroom.

What other Strategies For Teaching Vocabulary would you suggest? I would love to hear from you.

References

Grant, K..B., Golden, S.E., & Wilson, N.S.(2015). Literacy Assessment and Instructional Strategies: Connecting to the Common Core. USA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2002). The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program. In A.E. Farstrup 1 S.J.Samuels (Eds.), what research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp.140-165). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Graves, M.F., & Watts-Taffe, S.M. (2008). For the love of words: Fostering word consciousness in young readers. The Reading Teacher, 62 (3), 185-193.

Hulstijn, J. & Laufer, B.(2001). Some empirical evidence for the involvement load hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition. Language Learning 51/3:539-58.

Lubliner, SH.(2005). Getting into Words: Vocabulary Instruction That Strengthens Comprehension. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing.

Schmitt, D., & Schmitt, N.(2005). Focus on Vocabulary. New York: Longman.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009a). Word Knowledge: A vocabulary teacher’s handbook. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zimmerman, Cheryl. B.(2009b).(ed.). Inside Reading: The Academic Word List in Context. Four Levels. New York: Oxford University Press.

The Importance of Vocabulary Development

According to Steven Stahl (2005), “Vocabulary knowledge is knowledge; the knowledge of a word not only implies a definition, but also implies how that word fits into the world.” We continue to develop vocabulary throughout our lives. Words are powerful. Words open up possibilities, and of course, that’s what we want for all of our students.

Key Concepts

Differences in Early Vocabulary Development

We know that young children acquire vocabulary indirectly, first by listening when others speak or read to them, and then by using words to talk to others. As children begin to read and write, they acquire more words through understanding what they are reading and then incorporate those words into their speaking and writing.

Vocabulary knowledge varies greatly among learners. The word knowledge gap between groups of children begins before they enter school. Why do some students have a richer, fuller vocabulary than some of their classmates?

- Language rich home with lots of verbal stimulation

- Wide background experiences

- Read to at home and at school

- Read a lot independently

- Early development of word consciousness

Why do some students have a limited, inadequate vocabulary compared to most of their classmates?

- Speaking/vocabulary not encouraged at home

- Limited experiences outside of home

- Limited exposure to books

- Reluctant reader

- Second language—English language learners

Children who have been encouraged by their parents to ask questions and to learn about things and ideas come to school with oral vocabularies many times larger than children from disadvantaged homes. Without intervention this gap grows ever larger as students proceed through school (Hart and Risley, 1995).

How Vocabulary Affects Reading Development

From the research, we know that vocabulary supports reading development and increases comprehension. Students with low vocabulary scores tend to have low comprehension and students with satisfactory or high vocabulary scores tend to have satisfactory or high comprehension scores.

The report of the National Reading Panel states that the complex process of comprehension is critical to the development of children’s reading skills and cannot be understood without a clear understanding of the role that vocabulary development and instruction play in understanding what is read (NRP, 2000).

Chall’s classic 1990 study showed that students with low vocabulary development were able to maintain their overall reading test scores at expected levels through grade four, but their mean scores for word recognition and word meaning began to slip as words became more abstract, technical, and literary. Declines in word recognition and word meaning continued, and by grade seven, word meaning scores had fallen to almost three years below grade level, and mean reading comprehension was almost a year below. Jeanne Chall coined the term “the fourth-grade slump” to describe this pattern in developing readers (Chall, Jacobs, and Baldwin, 1990).

Incidental and Intentional Vocabulary Learning

How do we close the gap for students who have limited or inadequate vocabularies? The National Reading Panel (2000) concluded that there is no single research-based method for developing vocabulary and closing the gap. From its analysis, the panel recommended using a variety of indirect (incidental) and direct (intentional) methods of vocabulary instruction.

Incidental Vocabulary Learning

Most students acquire vocabulary incidentally through indirect exposure to words at home and at school—by listening and talking, by listening to books read aloud to them, and by reading widely on their own.

The amount of reading is important to long-term vocabulary development (Cunningham and Stanovich, 1998). Extensive reading provides students with repeated or multiple exposures to words and is also one of the means by which students see vocabulary in rich contexts (Kamil and Hiebert, 2005).

Intentional Vocabulary Learning

Students need to be explicitly taught methods for intentional vocabulary learning. According to Michael Graves (2000), effective intentional vocabulary instruction includes:

- Teaching specific words (rich, robust instruction) to support understanding of texts containing those words.

- Teaching word-learning strategies that students can use independently.

- Promoting the development of word consciousness and using word play activities to motivate and engage students in learning new words.

Research-Supported Vocabulary-Learning Strategies

Students need a wide range of independent word-learning strategies. Vocabulary instruction should aim to engage students in actively thinking about word meanings, the relationships among words, and how we can use words in different situations. This type of rich, deep instruction is most likely to influence comprehension (Graves, 2006; McKeown and Beck, 2004).

Student-Friendly Definitions

The meaning of a new word should be explained to students rather than just providing a dictionary definition for the word—which may be difficult for students to understand. According to Isabel Beck, two basic principles should be followed in developing student-friendly explanations or definitions (Beck et al., 2013):

- Characterize the word and how it is typically used.

- Explain the meaning using everyday language—language that is accessible and meaningful to the student.

Sometimes a word’s natural context (in text or literature) is not informative or helpful for deriving word meanings (Beck et al., 2013). It is useful to intentionally create and develop instructional contexts that provide strong clues to a word’s meaning. These are usually created by teachers, but they can sometimes be found in commercial reading programs.

Defining Words Within Context

Research shows that when words and easy-to-understand explanations are introduced in context, knowledge of those words increases (Biemiller and Boote, 2006) and word meanings are better learned (Stahl and Fairbanks, 1986). When an unfamiliar word is likely to affect comprehension, the most effective time to introduce the word’s meaning may be at the moment the word is met in the text.

Using Context Clues

Research by Nagy and Scott (2000) showed that students use contextual analysis to infer the meaning of a word by looking closely at surrounding text. Since students encounter such an enormous number of words as they read, some researchers believe that even a small improvement in the ability to use context clues has the potential to produce substantial, long-term vocabulary growth (Nagy, Herman, and Anderson, 1985; Nagy, Anderson, and Herman, 1987; Swanborn and de Glopper, 1999).

Sketching the Words

Sketching the Words

For many students, it is easier to remember a word’s meaning by making a quick sketch that connects the word to something personally meaningful to the student. The student applies each target word to a new, familiar context. The student does not have to spend a lot of time making a great drawing. The important thing is that the sketch makes sense and helps the student connect with the meaning of the word.

Applying the Target Words

Applying the target words provides another context for learning word meanings. When students are challenged to apply the target words to their own experiences, they have another opportunity to understand the meaning of each word at a personal level. This allows for deep processing of the meaning of each word.

Analyzing Word Parts

Analyzing Word Parts

The ability to analyze word parts also helps when students are faced with unknown vocabulary. If students know the meanings of root words and affixes, they are more likely to understand a word containing these word parts. Explicit instruction in word parts includes teaching meanings of word parts and disassembling and reassembling words to derive meaning (Baumann et al., 2002; Baumann, Edwards, Boland, Olejnik, and Kame’enui, 2003; Graves, 2004).

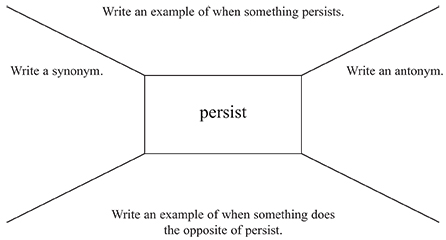

Semantic Mapping

Semantic Mapping

Semantic maps help students develop connections among words and increase learning of vocabulary words (Baumann et al., 2003; Heimlich and Pittleman, 1986). For example, by writing an example, a non-example, a synonym, and an antonym, students must deeply process the word persist.

Word Consciousness

Word consciousness is an interest in and awareness of words (Anderson and Nagy, 1992; Graves and Watts-Taffe, 2002). Students who are word conscious are aware of the words around them—those they read and hear and those they write and speak (Graves and Watts-Taffe, 2002). Word-conscious students use words skillfully. They are aware of the subtleties of word meaning. They are curious about language, and they enjoy playing with words and investigating the origins and histories of words.

Teachers need to take word-consciousness into account throughout their instructional day—not just during vocabulary lessons (Scott and Nagy, 2004). It is important to build a classroom “rich in words” (Beck et al., 2002). Students should have access to resources such as dictionaries, thesauruses, word walls, crossword puzzles, Scrabble® and other word games, literature, poetry books, joke books, and word-play activities.

Teachers can promote the development of word consciousness in many ways:

- Language categories: Students learn to make finer distinctions in their word choices if they understand the relationships among words, such as synonyms, antonyms, and homographs.

- Figurative language: The ability to deal with figures of speech is also a part of word-consciousness (Scott and Nagy 2004). The most common figures of speech are similes, metaphors, and idioms.

Once language categories and figurative language have been taught, students should be encouraged to watch for examples of these in all content areas.

Teaching Words and Vocabulary-Learning Strategies With Read Naturally Programs

Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades

Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades

These intentional vocabulary learning strategies can be efficiently and effectively implemented using Read Naturally’s program Take Aim! at Vocabulary. Take Aim is appropriate for students who can read at least at a fourth grade level. Take Aim is available in two formats:

- The semi-independent format provides differentiated instruction for students working mostly independently.

- The small-group format is designed for small-group instruction—up to six students.

Each Take Aim level teaches 288 carefully selected target words in the context of engaging, non-fiction stories. The target words are systematically taught using the research-based strategies described above. The intensive and focused lesson design helps students learn the target words and internalize the skills and strategies necessary for independently learning unknown words.

Learn more about how Take Aim teaches vocabulary and word-learning strategies:

- Take Aim at Vocabulary product page

- Take Aim samples

- Research basis for Take Aim at Vocabulary

Splat-O-Nym: Vocabulary Word Game for iPad

Learn more about the Splat-O-Nym app:

- Splat-O-Nym product page

- Research basis for Splat-O-Nym

Other Programs That Support Vocabulary Development

These other Read Naturally programs do not focus on vocabulary but include activities that support vocabulary development:

Bibliography

Anderson, R. C., & Nagy, W. E. (1992). “The vocabulary conundrum,” American Educator, Vol. 16, pp. 14-18, 44-47.

Baumann, J. F., Edwards, E. C., Boland, E., Olejnik, S., & Kame’enui, E. (2003). “Vocabulary tricks: effects of instruction in morphology and context on fifth grade students’ ability to derive and infer word meanings,” American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 447–494.

Baumann, J. F., Edwards, E. C., Font, G., Tereshinski, C. A., Kame’enui, E. J., & Olejnik, S. (2002). “Teaching morphemic and contextual analysis to fifth-grade students.” Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 37, pp. 150–176.

Baumann, J. F., Kame’enui, E. J., & Ash, G. E. (2003). “Research on vocabulary instruction: Voltaire redux,” in J. Flood, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, and J. M. Jensen (eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts, 2nd ed., Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, pp. 752–785.

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life. Robust vocabulary instruction, New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life. Robust vocabulary instruction, 2nd ed., New York: Guilford Press.

Biemiller, A. & Boote, C. (2006). “An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in the primary grades,” Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 44–62.

Chall, J. S., Jacobs, V. A., & Baldwin, L. E. (1990). The reading crisis: Why poor children fall behind, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cunningham, A. E. & Stanovich, K. E. (1998). “What reading does for the mind,” American Educator, Vol. 22, pp. 8–15.

Graves, M. F. (2000). “A vocabulary program to complement and bolster a middle-grade comprehension program,” in B. M. Taylor, M. F. Graves, and P. Van Den Broek (eds.), Reading for meaning: Fostering comprehension in the middle grades, New York: Teachers College Press.

Graves, M. F. (2004). “Teaching prefixes: As good as it gets?,” in J. Baumann & E. Kame’enui (eds.), Vocabulary instruction, research to practice, New York: Guilford Press, pp. 81–99.

Graves, M. F. (2006). The vocabulary book, New York: Teachers College Press, International Reading Association, National Council of Teachers of English.

Graves, M. F. & Watts-Taffe, S. M. (2002). “The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program,” in A. E. Farstrup and S. J. Samuels (eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction, Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Hart, B. & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children, Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Heimlich, J. E. & Pittleman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications, Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Kamil, M. L. & Hiebert, E. H. (2005). “Teaching and learning vocabulary: Perspectives and persistent issues,” in E. H. Hiebert and M. L. Kamil (eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

McKeown, M. G. & Beck, I. L. (2004). “Direct and rich vocabulary instruction,” in J. Baumann & E. Kame’enui (eds.), Vocabulary instruction, research to practice, New York: Guilford Press, pp. 13–27.

Nagy, W. E., Anderson, R. C., & Herman, P. A. (1987). “Learning word meanings from context during normal reading,” American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 24, pp. 237-270.

Nagy, W. E., Herman, P. A. & Anderson, R. C. (1985). “Learning words from context,” Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 233–253.

Nagy, W. E. & Scott, J. A. (2000). “Vocabulary processes,” in M. L. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, and R. Barr (eds.), Handbook of reading research, Vol. 3, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769), Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 13–14.

Scott, J. & Nagy, W. (2004). “Developing word consciousness,” in J. Baumann & E. Kame’enui (eds.), Vocabulary instruction, research to practice, New York: Guilford Press, pp. 201–215.

Stahl, S. A. (2005). “Four problems with teaching word meanings (and what to do to make vocabulary an integral part of instruction),” in E. H. Hiebert and M. L. Kamil (eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Stahl, S. A. & Fairbanks, M. M. (1986). “The effects of vocabulary instruction: A model-based meta analysis,” Review of Educational Research, Vol. 56, pp. 72–110.

Swanborn, M. S. & de Glopper, K. (1999). “Incidental word learning while reading: A meta-analysis,” Review of Educational Research, Vol. 69, pp. 261-285.

Listen to the interview with Angela Peery:

Sponsored by Google for Education’s Applied Digital Skills and fastIEP

I’ve been an educator for 36 years, and if there’s one thing I think every educator can agree on, it’s that increasing the number of words our students know is a good thing. Period.

This is supported by decades of research:

- A rich vocabulary supports content knowledge in all disciplines. Conceptual understanding, along with both general and specific word knowledge, impacts learning at every age level, starting with oral language development in preschool. When older students know the meaning of specific words and are able to put related words together during a unit of study, they can connect to new content more readily and remember more (Marzano & Simms, 2013).

- Word knowledge is key for reading comprehension. Kindergarten students’ word knowledge predicts reading comprehension in second grade (Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomblin, 1999; Roth, Speece, & Cooper, 2002), and this persists through fourth grade (Wagner, Muse, & Tannenbaum, 2007). Even more surprisingly, Cunningham and Stanovich (1997) find that first-grade students’ vocabulary knowledge predicts their reading comprehension level much later, in the eleventh grade.

- Students who are deficient in vocabulary face numerous obstacles, including having much lower reading comprehension. Their reading range is thus limited, their writing lacks specificity and voice, and their spoken language lacks range of word choice. They risk reading less (both in volume and frequency), not understanding content-area texts or concepts well, writing lackluster essays and reports, and not being able to express themselves as well verbally.

This is why all teachers should address vocabulary instruction head-on.

But what words should be taught? In English language arts/reading classrooms, explicit vocabulary instruction should focus on general academic words (Beck, McKeown & Kucan, 2013). These words cut across disciplines and help students speak, read, and write well in all the academic settings in which they’ll find themselves. In every discipline, there are also domain-specific terms students need to understand and learn.

8 Vocabulary-Building Strategies

Good vocabulary instruction can and should happen throughout the school day. This can happen through incidental learning, when students talk with and listen to others, watch videos, play games, and read independently, through explicit instruction, which are more structured activities, or with the help of digital tools.

The strategies that follow, most of which require very little preparation time, come from three of my books, shown below:

Amazon | Bookshop Amazon Amazon | Bookshop

Strategy 1: Informal Conversations

One of the most powerful things teachers (and adults in the home) can do is to have rich conversations with children. Recent research on conversational turns (LENA, 2017) indicates that the more turns a young child takes in conversation with an adult, the more they grow their vocabulary and verbal acuity in general.

So asking questions of a student, receiving their responses, adding information, and asking them to reflect or add more information—in other words, keeping the conversation going—is important in vocabulary development. This idea has great potential for non-instructional segments of the preschool elementary day like snack time, lining up to go to lunch, and restroom breaks. It also has potential for older students.

Strategy 2: Anchored Word Learning

Anchored Word Learning (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2002) is ideal to use with elementary students where read-alouds are typically part of the daily routine. It can also be used in the upper grades, especially with complex text that is being read aloud and discussed together as a whole class.

For young children, picture books provide excellent sources of higher-level, sophisticated words that are important for expanding vocabulary. They expose students to words they would not typically read within leveled books or on their own. For older children, excerpts from novels, nonfiction texts of various types, and content-area texts can all be used for anchored word learning.

Isabel Beck suggests selecting three general academic words each time the teacher reads aloud a picture book or trade book; these should not be esoteric or archaic terms, but words likely to come up in other academic texts. Older students may be able to handle more words during a read-aloud and class discussion, but teachers are cautioned not to select too many words for one lesson. Three to five words is usually sufficient.

Prior to reading, teachers need to complete three simple preparation steps:

- Select a read-aloud. Choose from books by favorite authors, recommended books, new books, old favorites, picture books, trade books, and content-area texts that impart critical information.

- Identify three to five words for direct instruction. Select words which will expand students’ vocabulary and will likely appear in varied contexts—or focus on words critically important to the content being taught. “Nice to know” words don’t have a place here. The idea is to teach important words that are likely to appear in various contexts or words you really want students to know.

- Mark the words in the text with a sticky note or with a highlighter and annotations if the text is on paper.

Once this preparation is complete, follow these steps with students:

- Read the entire text aloud. Don’t stop in the first reading to discuss the words at length. Students need to hear complex texts being read aloud fluently—especially a first reading—so they can start to process the story itself or the complicated ideas present in many nonfiction and content-specific texts.

- After reading the text through once, go back and bring attention to each targeted word. You may want to reread the sentences and/or paragraphs in which each word appears.

- Have students say each word aloud.

- Write each word so it’s visible to students. You may want to have students write the words down as well (or use their fingers and “write” the words in the air or in the palms of their hands). With younger students, spell the word as you write it. Call attention to any interesting spelling feature, such as double letters, silent E, prefixes, etc.

- Provide a student-friendly definition of each word. You may want to repeat this several times.

- Provide examples for each word beyond the context of the text. Encourage children to provide examples of their own so they personalize the word, relating it to their own context. This is a great time to use think-pair-share or turn-and-talk.

- If desired, post these words on your academic word wall. If you’re an ELA/reading teacher, you may want to have a section of the word wall dedicated to words from read-alouds.

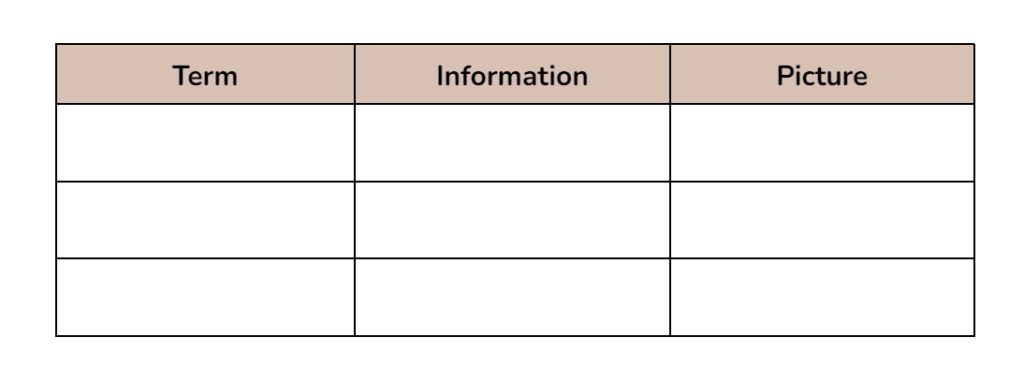

Strategy 3: TIP Chart

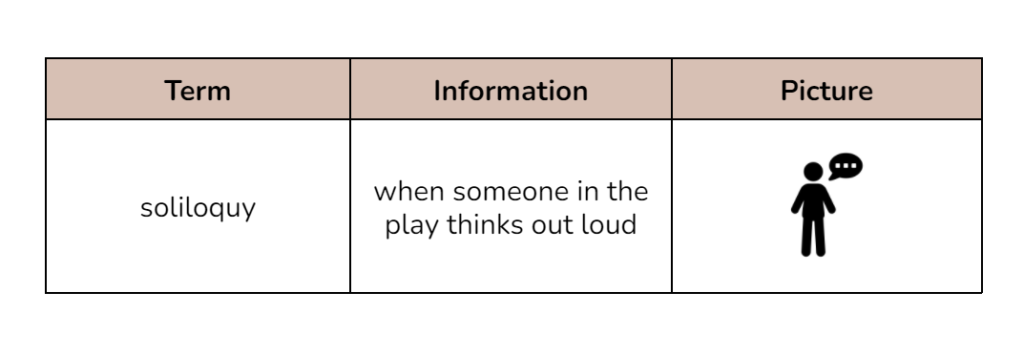

This adaptation of a word wall features a visual in addition to a brief definition. TIP stands for term, information, and picture. Basically, a TIP Chart (Rollins, 2014) is a three-column poster displayed so students can quickly use it to remind them of the meaning of an important content-area (tier three) word. In essence, it’s a vocabulary anchor chart.

Unlike the well-known Frayer Model, the TIP Chart is useful for words that are fairly straightforward in meaning—not ones with heavy conceptual weight. Once completed, the TIP Chart serves as an “at a glance” reference for important disciplinary terms; this purpose must be kept in mind if the strategy is to be most beneficial.

TIP charts are displayed prominently for the whole class to see, but students can also keep personal TIP charts in their notebooks or digital files as well. The teacher can first model how to create the chart, and later, students can be involved in deciding what information to record and what picture to draw to go with each word.

The best time to use the strategy is when beginning a new chunk of instruction, like a chapter or unit. With the chart ready, announce the first word and call students’ attention to the importance of this word in the current segment of instruction. Write the word in column one. Then share the formal and full definition, which ideally would also be printed in the text or on a screen or board in the classroom. Along with students, from this full definition, develop a short, student-friendly definition or a brief list that you write in the middle column. Do not write the full, formal definition in column two. Lastly, provide or co-create a simple visual in column three.

So, for the term soliloquy in my 9th grade English class, I would first give the formal definition: A long, usually serious speech that a character in a play makes to an audience and that reveals the character’s thoughts. We might talk for a minute about the fact that playwrights use soliloquies so the audience understands what a character is thinking. So, in the middle column, we might write the student-friendly, casual definition: When someone in the play thinks out loud. And, to emphasize the fact that this kind of speech is usually given with the character standing alone on the stage, I might then draw a single stick figure with lines or a speech bubble emanating from its face to indicate that he or she is speaking.

The TIP Chart in my class might look something like this:

Here’s a social studies example. For the term “monopoly,” the full definition might be “the exclusive possession or control of the supply or trade in a commodity or service.” It is assumed that the teacher is also teaching the term “commodity” along with “monopoly.” In column two for “monopoly,” the teacher may write “control of a product or service.” In the third column, he or she might draw a large square that surrounds smaller squares, thus showing the dominance of the one provider. Students might also suggest something that symbolizes a monopoly to them, like an iPhone surrounded by other types of cell phones, but the iPhone appears much larger or more prominent, or the other phones are crossed out.

Teachers can gradually do less in whole-class fashion with TIP charts and encourage students to create their own in hard-copy notebooks or digital notebooks using Google Docs, LiveBinders, or OneNote. Students might preview the first part of each chapter or unit (in any class) and try to complete a personal TIP chart to be kept in their organizational system. They could also collaborate with other students to create TIP charts, so that if any individual is confused about a word, they can get ideas from others. This is a portable strategy students can use with any content area and any textbook from elementary school well into college.

Strategy 4: Save the Last Word for Me

Save the Last Word for Me (Beers, 2003) is an ideal strategy to promote peer conversation, increase engagement, and promote deeper processing about vocabulary and content. Although it’s usually applied to conversations about literature, its clearly defined structure is perfect for reviewing vocabulary and gaining deeper understanding of specific terms.

It is fairly typical for teachers to provide guided review activities before a unit test, midterm, or final exam. Let’s say the instructional unit includes about 25 terms which students must recognize and understand how to use correctly within context. Save the Last Word for Me serves as an engaging vehicle for students to practice doing so in preparation for an assessment.

The steps for employing this strategy are as follows; the first three need to be completed ahead of time:

- Print multiple sets of cards with a target word on one side and the definition on the reverse side (one set for each group of students).

- Print the directions for the activity (see below).

- Place the printed directions and terms in a plastic bag or manila envelope for each group of students.

- Divide students into groups of three to five. It’s important that groups are small so each student has an opportunity to discuss. The goal is for students to review and deepen understanding about concepts and specific terms, so making sure they clarify their thinking aloud is important.

To begin, one student draws a card from the deck and another student defines the term. Moving around the circle, each student adds to the definition, refining and adding examples along the way. The person who draws the cards gets the “last word” and can add to the definition or revise it before students agree upon a definition. You may want to model the process in whole-class fashion first or by having a small group model the process as the rest of the class watches.

Sometimes, if the bank of terms is large, I suggest simply printing one master deck of cards and place five or six cards in each bag. After a few minutes, signal the groups to trade bags of terms and, in so doing, each group gets new terms to review.

While Save the Last Word for Me is low-tech, sometimes simpler is better. It delivers by supporting interaction and engagement, deeper conversations, and higher-level processing.

Student Directions for Save the Last Word for Me

- One student selects a card from the deck and says the term aloud with the other group members.

- On a piece of paper, each student jots down what they know about the term. (This can also be “in your head” and each person takes about 30 seconds to think about what they know about the meaning.)

- When everyone is finished, each person takes a turn sharing their reflections/responses. As each participant shares their thoughts, other students can share thoughts and responses.

- The student who drew the card gets the last word by sharing their reflections/reactions or by stating a fresh view if the responses of others have altered their original thinking.

- If students are unsure or need clarification, they refer to the text, notes, and/or handouts for clarification.

- Another student draws a new card, and the process is repeated.

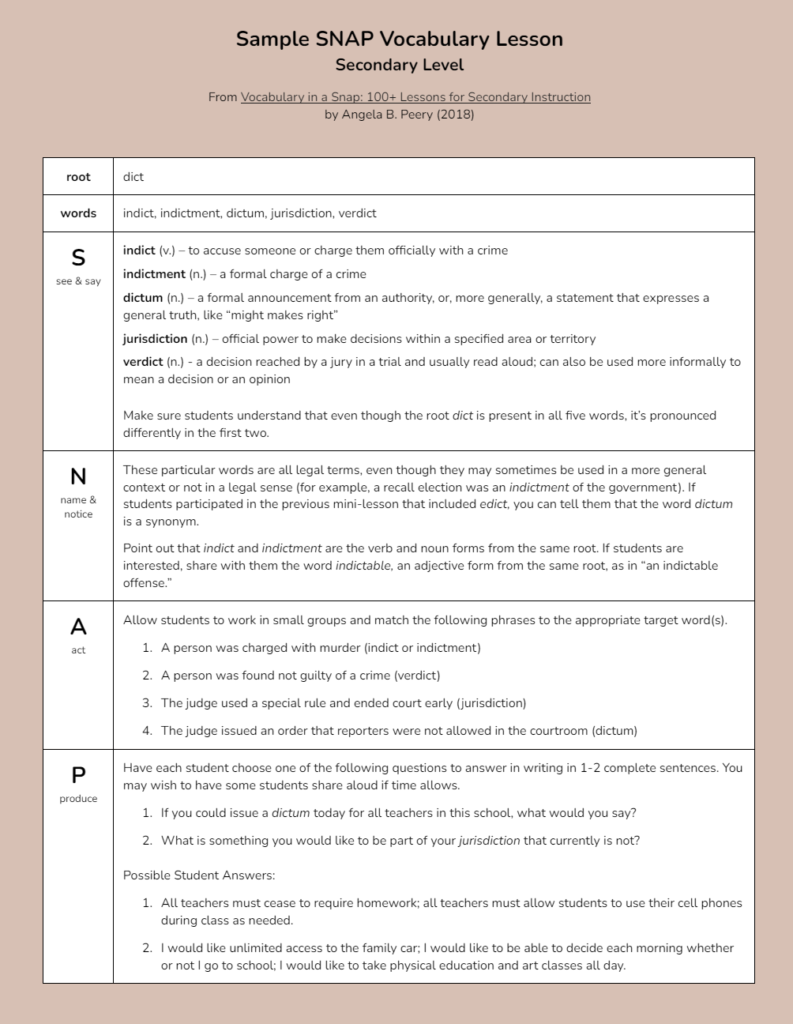

Strategy 5: SNAP Minilessons

Setting aside specific time daily, weekly, or periodically to explicitly teach general academic vocabulary through minilessons (of 5 to 15 minutes each) is another way you can provide explicit instruction.

Each minilesson in my books contains four core components or steps, which the acronym SNAP in the title represents:

S: Seeing and saying each word

N: Naming a category or group each word belongs to or noticing connections to related words or word families

A: Acting on the words (engaging in a brief task or conversation about the words)

P: Producing an individual, original application of the words

The example below is intended for secondary students.

Strategy 6: Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy

The primary purpose of the Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy (VSS) (Haggard, 1986) is to help students generate a list of words to be learned based on their prior knowledge and experience with reading and texts. This strategy can stimulate word growth and independence as students read texts and select vocabulary which they deem important to understanding the content.

VSS includes the following steps:

- Selecting words

- Defining words

- Finalizing word lists

- Extending word knowledge

The strategy can be used to support general word learning from one’s environment or to support vocabulary learning from assigned and self-selected texts.

A colleague of mine routinely used this strategy to support general word learning with college freshmen. Every week, students “collected” three words from their environment (watching, listening, and reading) that they thought important to learn. For each word, students included the following information

- An accurate definition

- Where they heard or read the word including a bit of the context

- A justification for why they thought the word was important to learn

Words were shared and discussed in class at an established time each week. Students also recorded their words in personal vocabulary notebooks. VSS engaged students in lively discussions and specifically raised word consciousness, a critical goal of word learning.

Another way VSS can be implemented is to specifically support word acquisition from content-area text. To support content learning, students can work in cooperative groups and read a chapter from a textbook (or any text). As they read, they identify words they think should be studied and mastered. During class discussion, groups then share their words and why they think the terms are important to mastering content. Additional steps can include developing a class list that contains one word from each group, creating TIP charts with the words, and having students teach minilessons focused on the words to each other.

Strategy 7: Word Talks

Word talks were derived from a similar strategy called book talks, in which students give a brief (less than five minutes) presentation about a book they recommend to their peers for independent reading. Word talks are similar in that they require a student to give a brief presentation on one or several words that they feel are important for their peers to know. This strategy is, like some others in this chapter, excellent for general academic words, not highly specialized, domain-specific words. Also, it can be easily combined with the Vocabulary Self-Collection strategy discussed earlier.

Some teachers who use word talks schedule a certain day a week or a certain day per month on which several students get up and do their word talks. Other teachers schedule a rotation so that a few times a week, one student is doing a word talk that day. Because the word talks consist of a student teaching their peers, it’s important to make time for this, because students tend to find the periods in which their classmates are leading discussion much more memorable than when the teacher is; students often have a way of saying something that “clicks” with their peers just because it’s said in a kid-friendly way.

What kind of words should students share in word talks? Many students share from their independent reading and their media and technology use. Teachers can ask students to provide a rationale for each word chosen if they like, but they can also allow students to share any word that might be interesting. I find myself thinking of the character Sam in the Netflix series Atypical as a high school student. He would have certainly loved to share words related to penguins and Antarctica in word talks.

In a word talk in one of my high school classes, a student selected the following words to share: ascent, descent, decompression, and recompression. Can you tell what the student was learning to do outside of school? Scuba diving. This student was studying for her initial scuba certification and thought these words would be good to share because although they have scuba-specific meanings, they also have application to non-scuba situations.

Word talks are great opportunities for some students to showcase their interests and expertise, but most importantly, they make clear that continual word learning is important.

Strategy 8: Digital Tools for Independent Practice

The following websites/programs offer support for you as a teacher as well as independent practice activities for students:

Flocabulary

This robust program includes hip-hop type videos to help students learn new terminology.

Freerice

This site has an addictive vocabulary game with five difficulty levels, with levels one and two being appropriate for students in grades three and up.

Vocabador

This game allows students to study SAT vocabulary words, choose an avatar, and “get into the ring” to play against other virtual wrestlers.

There’s nothing negative that comes about when anyone grows their vocabulary—and for students, there are many, many positives. By adding even a few of these strategies to your repertoire, you’ll help students build vocabularies that will support them no matter what path they choose to pursue.

References

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Beers, K. (2003). When kids can’t read, what teachers can do: A guide for teachers 6–12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Zhang, X., & Tomblin, J. B. (1999). Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(4), 331–361.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 934–945.

Haggard, M. R. (1986). The vocabulary self-collection strategy: Using student interest and world knowledge to enhance vocabulary growth. Journal of Reading, 29(7), 634–642.

LENA. 2017. Proving the Power of Talk: 10 Years of Research on the Impact of Language on Young Children. Available at https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3975639/Research_Summary.pdf?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lena.org%2F.

Marzano, R. J., & Simms, J. A. (2013). Vocabulary for the Common Core. Bloomington, IN: Marzano Research.

Rollins, S. P. (2014). Learning in the fast lane: 8 ways to put all students on the road to academic success. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wagner, R. K., Muse, A. E., & Tannenbaum, K. R. (Eds.). (2007). Vocabulary acquisition: Implications for reading comprehension. New York: Guilford Press.

Come back for more.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

The theory and techniques for teaching vocabulary may not be as fun as the ideas that I’ll share in the next post or as perusing the books in the last post, yet this is the theory applicable to all ages and types of readers. It is the knowledge that will enable you to choose the right activities and strategies for your content and grade level.

PURPOSES FOR TEACHING VOCABULARY

In my experience, we teach vocabulary for a variety of reasons. It’s important to think about the vocabulary instruction in your teaching practice by considering why you are doing it. That will help you determine which theories and techniques you should use (or at least try).

Reasons include:

- Improving reading comprehension in general.

- Improving subject-specific mastery and performance.

- Improving writing and speaking skills.

- Test preparation (SAT, ACT, etc.).

- Deepening students’ ability to put their thoughts into the most appropriate word possible.

These techniques and theories are in no particular order.

This post is Part 2 of a four-part series on teaching vocabulary. If you would like to check out the rest of the series, visit the posts below

- Teaching Vocabulary: The books

- Theories & Techniques that work (and don’t) (this one)

- 21 Activities for Teaching Vocabulary

- Ideas for English Language Learners

EXPOSURE RATES MATTER

Students need to be exposed to the vocabulary over and over if they are to understand and use the words effortlessly. When stories or texts are repeated, students gain more word knowledge.

Research shows that students hearing stories more than once have a 12% gain over their peers who only heard the story one time when tested on the vocabulary in context.

Want to read the research? Look for the studies done by Biemiller and Boote (2006) and Coyne, Simmons, Kame`enui, and Stoolmiller (2004).

DEFINE THE WORDS WHILE YOU READ

It works better to share vocabulary in context, rather than just learning definitions. Giving students lists of words and having them look up the definitions is useless and ineffective. You’re shocked, aren’t you?

It’s also important to emphasize and practice pronunciation of new/unfamiliar words. Don’t assume that regular decoding skills will work with academic vocabulary. Practice saying the words.

Want to read the research? Look for the study done by Nash and Snowling (2006).

TIERED WORDS: VOCABULARY IN THE CORE

To decide whether or not a word from a story or lesson should be directly taught, consider:

- Is it unfamiliar but able to be understood?

- Is it necessary for comprehension?

- Does it appear in other contexts?

- Is it likely to show up again?

One particular model divides words into three categories, or tiers. This model was developed by Isabelle Beck in Bringing Words to Life.

- Tier One words are the words of everyday speech usually learned in the early grades. These are not necessary to teach explicitly (except for in ELL acquisition).

- Tier Two words are what the Common Core standards refer to as academic words. They are more to be read by students in texts that heard in conversations. They may be in informational or technical texts, or in literary works with sophisticated vocabulary. They often make language more precise (saying “wended their way” instead of “walked along,” for example). They are words that cross domains, so you may see them in a variety of disciplines.

- Tier Three words are the domain-specific words that you would only see in relation to a specific content area. They are the ones you see bolded in textbooks and/or listed in the glossary.

You can watch a video about this at Engage NY.

(Note: The words that she mentions in the beginning of the video that you would see only in certain areas are Tier Three words.)

ASK QUESTIONS

Students learn the vocabulary best when teachers actually integrate questioning and discussion into lessons, rather than just defining them.

Here are some example questions:

- What other words do you know that are similar to this word?

- How can we use this word in [insert other thing you’ve studied]?

- Do you recognize any of the parts of this word?

- If I said that [insert another word here] is the same or similar as this word, would that be true?

Want to read the research? Look for the study by Ard and Beverly (2004).

THE FOUR COMPONENTS

Michael Graves argues that there are four components of an effective vocabulary program:

- Teach individual words: Teach new words explicitly, meaning on purpose. Make sure students understand the definition. Make sure the definitions are in student-friendly vocabulary. It doesn’t help you to understand a word if you don’t know the words in the definition, either. Show the word in a variety of contexts. Have students generate their own definitions. Have them engage with the words interactively, playing with them. Vary the methods so you’re not teaching the same way for every word.

- Provide rich and varied language experiences: We need reading, listening, speaking, and writing experiences across multiple genres. Yes, there is math poetry. Read out loud to students. Encourage book clubs and reading challenges. The idea: create an environment saturated with words.

- Teach word-learning strategies: Teach students how to infer word meaning from context clues. Teach students how to infer meaning from morpheme clues. Teach students how and when to use a dictionary and a thesaurus. We can’t assume that students know the strategies they need to make sense of words.

- Foster word consciousness: Point out useful, beautiful, powerful, or painful lessons. Be playful with words.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

When testing students’ command of vocabulary, use a self-assessment that is non-judgmental, using prompts such as:

- I have never seen or heard the word before.

- I’ve seen or heard the word, but I don’t know what the word means.

- I vaguely know the meaning.

- I can associate the word with a concept or context.

- I know the word well.

- I can explain and use it in general or in writing.

- I can explain and use it with a full and precise meaning.

EASE METHOD

- Enunciate new words syllable-by-syllable and then blend the word.

- Associate the word with definitions and examples that students already know.

- Synthesize the words with other words and concepts that they have already studied and they have the opportunity to demonstrate deep knowledge of the new word.

- Emphasize new words in classroom discussion.

SIX STEP MODEL OF VOCABULARY INTRODUCTION

- Step one: The teacher explains a new word, going beyond reciting its definition (tap into prior knowledge of students, use imagery).

- Step two: Students restate or explain the new word in their own words (verbally and/or in writing).

- Step three: Ask students to create a non-linguistic representation of the word (a picture, or symbolic representation).

- Step four: Students engage in activities to deepen their knowledge of the new word (compare words, classify terms, write their own analogies and metaphors).

- Step five: Students discuss the new word (pair-share, elbow partners).

- Step six: Students periodically play games to review new vocabulary (Pyramid, Jeopardy, Telephone).

DICTIONARIES

Use dictionaries to work with words that already somewhat familiar. It is not helpful to have students try to look up words they can’t spell.

WHAT DOESN’T WORK

Kate Kinsella’s ideas of what doesn’t work include:

- Incidental teaching of words

2. Asking, “Does anybody know what _____ means?”

3. Copying same word several times

4. Having students “look it up” in a typical dictionary

5. Copying from dictionary or glossary

6. Having students use the word in a sentence after #3,4, or 5

7. Activities that do not require deep processing (word searches, fill-in-the-blank)

8. Rote memorization without context

9. Telling students to “use context clues” as a first or only strategy or asking students

to guess the meaning of the word

10. Passive reading as a primary strategy (SSR)

Watch a video of her teaching about vocab instruction and find related activities here.

IDEAS FOR TEACHING VOCABULARY

This article has focused on the theory of teaching vocabulary. Be sure to check out the third article in the series for loads of activities for teaching vocabulary in your classroom.

- Teaching Vocabulary: The books

- Theories & Techniques that work (and don’t) (this one)

- 21 Activities for Teaching Vocabulary (the one with loads of activities!!!)

- Ideas for English Language Learners

THE ULTIMATE METHOD FOR TEACHING ACADEMIC VOCABULARY

I think academic vocabulary is so important that I’ve spent decades perfecting a method of teaching it that works like a dream! It’s called the Concept Capsule method, and I’ve written an entire book about it.

Find out more here (and get a 50% discount for reading this article!).

Note: This content uses affiliate links, which means that if you order one of the things I recommend, I may geta a small commission.

Undoubtedly, you remember the teaching strategies your instructors used for vocabulary: you would copy down definitions into notebooks and then for homework rewrite each word for what felt like a million times.

We can probably all agree that passive learning is not an effective teaching strategy to instruct vocabulary. Students need multiple exposures to a word before they can fully understand it. They also need to learn new words in context by reading. Teachers can emphasize active processing by having students connect new meanings to words they already know. The more exposures students have to a word, the better chance that they will remember it.

Here are five vocabulary instruction strategies to use with elementary students.

1. Word Detective

The most valuable thing that you can do to increase your students’ vocabulary is to encourage them to read. Wide reading is the main pathway for word acquisition. This activity enables students to see words in different contexts, therefore deepening their knowledge. It requires students to find new words as they encounter them in their daily reading. Here’s how word detective works:

- The teacher gives students a list of key words to search for.

- Students are to write each target word and its sentence on a sticky note, then place it on their desk each time they encounter a keyword.

- At the end of each school day, devote a few minutes to reading each sticky note.

- You can even make a game out it by assigning each word a point.

2. Semantic Maps

A semantic map is a graphic organizer that helps students visually organize the relationship between pieces of information. Researchers have identified this strategy as a great way to increase students’ grasp of vocabulary words. Sematic mapping can be used as a prereading activity to active prior knowledge, or to introduce key words. As a post-reading activity, it can be used to enhance understanding by adding new concepts to the map. Here’s how it works:

- The teacher decides on a key word and writes it on the front board.

- Students then read the key word and are asked to think about other words that come to mind when they read the word. Students then make a list of all of the words.

- Students share the recorded words, then as a class the words are categorized.

- Once category names are assigned, a class map is created and discussed.

- Students are then encouraged to suggest additional categories for the map or add to the old ones.

- Any new words that relate to the topic are added to the map as students read through the text.

3. Word Wizard

Cooperative learning is an effective way for students to learn and process information. The jigsaw learning technique is a quick and effective way for students to work with their peers while learning key vocabulary words. For this activity, each student is responsible for learning three new words and teaching those words to their group. Here’s how it works:

- The teacher divides students into groups. Each student in the group is responsible for learning three new words in the chapter.

- Each “word wizard” is instructed to write the definition of the word in his/her own words as well as draw an illustration of the word.

- After each “word wizard” has completed their task, it is their job to come back to their group and teach their peers what they have learned.

- Each group member can copy the new words that they learn from each member in their notebooks.

4. Concept Cube

A concept cube is a great strategy to employ word parts. Students receive a paper divided into six equal squares. On each of the squares students are instructed to write down one of the following:

- Vocabulary word

- Antonym

- Synonym

- Category it belongs to

- Essential characteristics

- Example

Students then cut, fold and tape the paper to make a cube. Then, with a partner, they roll their cube and must tell the relationship of the word that lands on top to the original vocabulary word.

5. Word Connect

A Venn diagram is a great way for students to compare similarities and differences within words. It also provides students with new exposures to words, which helps them solidify what they have learned. For this activity, students are directed to connect two words that are written in the center of a Venn diagram. Their task is to connect the two words by writing down each words definition on the Venn diagram, then explaining the reason for the connection.

Implementing a variety of approaches will help prevent boredom. Experiment with different strategies and techniques to determine which ones work the best for your students.

Sketching the Words

Sketching the Words Analyzing Word Parts

Analyzing Word Parts Semantic Mapping

Semantic Mapping Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades

Take Aim at Vocabulary: Build Vocabulary in the Middle Grades