Home

About

Blog

Contact Us

Log In

Sign Up

Follow Us

Our Apps

Home>Words that start with L>language>English to Czech translation

How to Say Language in CzechAdvertisement

Categories:

General

If you want to know how to say language in Czech, you will find the translation here. We hope this will help you to understand Czech better.

Here is the translation and the Czech word for language:

Jazyk

Edit

Language in all languages

Dictionary Entries near language

- landslide

- landslip

- lane

- language

- language skills

- languid

- languish

Cite this Entry

«Language in Czech.» In Different Languages, https://www.indifferentlanguages.com/words/language/czech. Accessed 14 Apr 2023.

Copy

Copied

Check out other translations to the Czech language:

- dye

- enigma

- gain experience

- hoist

- nodule

- perfumery

- prevalence

- starting

- watch

- wish

Browse Words Alphabetically

| Czech | |

|---|---|

| čeština, český jazyk | |

| Native to | Czech Republic |

| Ethnicity | Czechs |

|

Native speakers |

10.7 million (2015)[1] |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Writing system |

|

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

|

|

Recognised minority |

|

| Regulated by | Institute of the Czech Language (of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | cs |

| ISO 639-2 | cze (B) ces (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ces |

| Glottolog | czec1258 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-da < 53-AAA-b...-d |

| IETF | cs[4] |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Czech (; Czech čeština [ˈtʃɛʃcɪna]), historically also Bohemian[5] (;[6] lingua Bohemica in Latin), is a West Slavic language of the Czech–Slovak group, written in Latin script.[5] Spoken by over 10 million people, it serves as the official language of the Czech Republic. Czech is closely related to Slovak, to the point of high mutual intelligibility, as well as to Polish to a lesser degree.[7] Czech is a fusional language with a rich system of morphology and relatively flexible word order. Its vocabulary has been extensively influenced by Latin and German.

The Czech–Slovak group developed within West Slavic in the high medieval period, and the standardization of Czech and Slovak within the Czech–Slovak dialect continuum emerged in the early modern period. In the later 18th to mid-19th century, the modern written standard became codified in the context of the Czech National Revival. The main non-standard variety, known as Common Czech, is based on the vernacular of Prague, but is now spoken as an interdialect throughout most of the Czech Republic. The Moravian dialects spoken in the eastern part of the country are also classified as Czech, although some of their eastern variants are closer to Slovak.

Czech has a moderately-sized phoneme inventory, comprising ten monophthongs, three diphthongs and 25 consonants (divided into «hard», «neutral» and «soft» categories). Words may contain complicated consonant clusters or lack vowels altogether. Czech has a raised alveolar trill, which is known to occur as a phoneme in only a few other languages, represented by the grapheme ř.

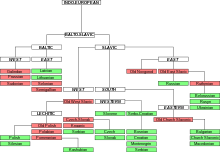

Classification[edit]

Classification of Czech within the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. Czech and Slovak make up a «Czech–Slovak» subgroup.

Czech is a member of the West Slavic sub-branch of the Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. This branch includes Polish, Kashubian, Upper and Lower Sorbian and Slovak. Slovak is the most closely related language to Czech, followed by Polish and Silesian.[8]

The West Slavic languages are spoken in Central Europe. Czech is distinguished from other West Slavic languages by a more-restricted distinction between «hard» and «soft» consonants (see Phonology below).[8]

History[edit]

Medieval/Old Czech[edit]

The term «Old Czech» is applied to the period predating the 16th century, with the earliest records of the high medieval period also classified as «early Old Czech», but the term «Medieval Czech» is also used. The function of the written language was initially performed by Old Slavonic written in Glagolitic, later by Latin written in Latin script.

Around the 7th century, the Slavic expansion reached Central Europe, settling on the eastern fringes of the Frankish Empire. The West Slavic polity of Great Moravia formed by the 9th century. The Christianization of Bohemia took place during the 9th and 10th centuries. The diversification of the Czech-Slovak group within West Slavic began around that time, marked among other things by its use of the voiced velar fricative consonant (/ɣ/)[9] and consistent stress on the first syllable.[10]

The Bohemian (Czech) language is first recorded in writing in glosses and short notes during the 12th to 13th centuries. Literary works written in Czech appear in the late 13th and early 14th century and administrative documents first appear towards the late 14th century. The first complete Bible translation, the Leskovec-Dresden Bible, also dates to this period.[11] Old Czech texts, including poetry and cookbooks, were also produced outside universities.[12]

Literary activity becomes widespread in the early 15th century in the context of the Bohemian Reformation. Jan Hus contributed significantly to the standardization of Czech orthography, advocated for widespread literacy among Czech commoners (particularly in religion) and made early efforts to model written Czech after the spoken language.[11]

Early Modern Czech[edit]

There was no standardization distinguishing between Czech and Slovak prior to the 15th century. In the 16th century, the division between Czech and Slovak becomes apparent, marking the confessional division between Lutheran Protestants in Slovakia using Czech orthography and Catholics, especially Slovak Jesuits, beginning to use a separate Slovak orthography based on Western Slovak dialects.[13][14]

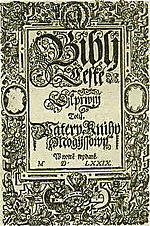

The publication of the Kralice Bible between 1579 and 1593 (the first complete Czech translation of the Bible from the original languages) became very important for standardization of the Czech language in the following centuries as it was used as a model for the standard language.[15]

In 1615, the Bohemian diet tried to declare Czech to be the only official language of the kingdom. After the Bohemian Revolt (of predominantly Protestant aristocracy) which was defeated by the Habsburgs in 1620, the Protestant intellectuals had to leave the country. This emigration together with other consequences of the Thirty Years’ War had a negative impact on the further use of the Czech language. In 1627, Czech and German became official languages of the Kingdom of Bohemia and in the 18th century German became dominant in Bohemia and Moravia, especially among the upper classes.[16]

Modern Czech[edit]

Josef Dobrovský, whose writing played a key role in reviving Czech as a written language.

The modern standard Czech language originates in standardization efforts of the 18th century.[17] By then the language had developed a literary tradition, and since then it has changed little; journals from that period have no substantial differences from modern standard Czech, and contemporary Czechs can understand them with little difficulty.[18] Sometime before the 18th century, the Czech language abandoned a distinction between phonemic /l/ and /ʎ/ which survives in Slovak.[19]

With the beginning of the national revival of the mid-18th century, Czech historians began to emphasize their people’s accomplishments from the 15th through the 17th centuries, rebelling against the Counter-Reformation (the Habsburg re-catholization efforts which had denigrated Czech and other non-Latin languages).[20] Czech philologists studied sixteenth-century texts, advocating the return of the language to high culture.[21] This period is known as the Czech National Revival[22] (or Renaissance).[21]

During the national revival, in 1809 linguist and historian Josef Dobrovský released a German-language grammar of Old Czech entitled Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprache (Comprehensive Doctrine of the Bohemian Language). Dobrovský had intended his book to be descriptive, and did not think Czech had a realistic chance of returning as a major language. However, Josef Jungmann and other revivalists used Dobrovský’s book to advocate for a Czech linguistic revival.[22] Changes during this time included spelling reform (notably, í in place of the former j and j in place of g), the use of t (rather than ti) to end infinitive verbs and the non-capitalization of nouns (which had been a late borrowing from German).[19] These changes differentiated Czech from Slovak.[23] Modern scholars disagree about whether the conservative revivalists were motivated by nationalism or considered contemporary spoken Czech unsuitable for formal, widespread use.[22]

Adherence to historical patterns was later relaxed and standard Czech adopted a number of features from Common Czech (a widespread, informally used interdialectal variety), such as leaving some proper nouns undeclined. This has resulted in a relatively high level of homogeneity among all varieties of the language.[24]

Geographic distribution[edit]

Czech is spoken by about 10 million residents of the Czech Republic.[16][25] A Eurobarometer survey conducted from January to March 2012 found that the first language of 98 percent of Czech citizens was Czech, the third-highest proportion of a population in the European Union (behind Greece and Hungary).[26]

As the official language of the Czech Republic (a member of the European Union since 2004), Czech is one of the EU’s official languages and the 2012 Eurobarometer survey found that Czech was the foreign language most often used in Slovakia.[26] Economist Jonathan van Parys collected data on language knowledge in Europe for the 2012 European Day of Languages. The five countries with the greatest use of Czech were the Czech Republic (98.77 percent), Slovakia (24.86 percent), Portugal (1.93 percent), Poland (0.98 percent) and Germany (0.47 percent).[27]

Czech speakers in Slovakia primarily live in cities. Since it is a recognized minority language in Slovakia, Slovak citizens who speak only Czech may communicate with the government in their language to the extent that Slovak speakers in the Czech Republic may do so.[28]

United States[edit]

Immigration of Czechs from Europe to the United States occurred primarily from 1848 to 1914. Czech is a Less Commonly Taught Language in U.S. schools, and is taught at Czech heritage centers. Large communities of Czech Americans live in the states of Texas, Nebraska and Wisconsin.[29] In the 2000 United States Census, Czech was reported as the commonest language spoken at home (besides English) in Valley, Butler and Saunders Counties, Nebraska and Republic County, Kansas. With the exception of Spanish (the non-English language most commonly spoken at home nationwide), Czech was the most common home language in more than a dozen additional counties in Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, North Dakota and Minnesota.[30] As of 2009, 70,500 Americans spoke Czech as their first language (49th place nationwide, after Turkish and before Swedish).[31]

Phonology[edit]

Vowels[edit]

Standard Czech contains ten basic vowel phonemes, and three diphthongs. The vowels are /a/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/, /o/, and /u/, and their long counterparts /aː/, /ɛː/, /iː/, /oː/ and /uː/. The diphthongs are /ou̯/, /au̯/ and /ɛu̯/; the last two are found only in loanwords such as auto «car» and euro «euro».[32]

In Czech orthography, the vowels are spelled as follows:

- Short: a, e/ě, i/y, o, u

- Long: á, é, í/ý, ó, ú/ů

- Diphthongs: ou, au, eu

The letter ⟨ě⟩ indicates that the previous consonant is palatalised (e.g. něco /ɲɛt͡so/). After a labial it represents /jɛ/ (e.g. běs /bjɛs/); but ⟨mě⟩ is pronounced /mɲɛ/, cf. měkký (/mɲɛkiː/).[33]

Consonants[edit]

The consonant phonemes of Czech and their equivalent letters in Czech orthography are as follows:[34]

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɲ ⟨ň⟩ | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | c ⟨ť⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | ɟ ⟨ď⟩ | (ɡ) ⟨g⟩ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s ⟨c⟩ | t͡ʃ ⟨č⟩ | ||||

| voiced | (d͡z) | (d͡ʒ) | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨š⟩ | x ⟨ch⟩ | ||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ | z ⟨z⟩ | ʒ ⟨ž⟩ | ɦ ⟨h⟩ | |||

| Trill | plain | r ⟨r⟩ | |||||

| fricative | r̝ ⟨ř⟩ | ||||||

| Approximant | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨j⟩ |

Czech consonants are categorized as «hard», «neutral», or «soft»:

- Hard: /d/, /ɡ/, /ɦ/, /k/, /n/, /r/, /t/, /x/

- Neutral: /b/, /f/, /l/, /m/, /p/, /s/, /v/, /z/

- Soft: /c/, /ɟ/, /j/, /ɲ/, /r̝/, /ʃ/, /t͡s/, /t͡ʃ/, /ʒ/

Hard consonants may not be followed by i or í in writing, or soft ones by y or ý (except in loanwords such as kilogram).[35] Neutral consonants may take either character. Hard consonants are sometimes known as «strong», and soft ones as «weak».[36] This distinction is also relevant to the declension patterns of nouns, which vary according to whether the final consonant of the noun stem is hard or soft.[37]

Voiced consonants with unvoiced counterparts are unvoiced at the end of a word before a pause, and in consonant clusters voicing assimilation occurs, which matches voicing to the following consonant. The unvoiced counterpart of /ɦ/ is /x/.[38]

The phoneme represented by the letter ř (capital Ř) is very rare among languages and often claimed to be unique to Czech, though it also occurs in some dialects of Kashubian, and formerly occurred in Polish.[39] It represents the raised alveolar non-sonorant trill (IPA: [r̝]), a sound somewhere between Czech r and ž (example: «řeka» (river) (help·info)),[40] and is present in Dvořák. In unvoiced environments, /r̝/ is realized as its voiceless allophone [r̝̊], a sound somewhere between Czech r and š.[41]

The consonants /r/, /l/, and /m/ can be syllabic, acting as syllable nuclei in place of a vowel. Strč prst skrz krk («Stick [your] finger through [your] throat») is a well-known Czech tongue twister using syllabic consonants but no vowels.[42]

Stress[edit]

Each word has primary stress on its first syllable, except for enclitics (minor, monosyllabic, unstressed syllables). In all words of more than two syllables, every odd-numbered syllable receives secondary stress. Stress is unrelated to vowel length; both long and short vowels can be stressed or unstressed.[43] Vowels are never reduced in tone (e.g. to schwa sounds) when unstressed.[44] When a noun is preceded by a monosyllabic preposition, the stress usually moves to the preposition, e.g. do Prahy «to Prague».[45]

Grammar[edit]

Czech grammar, like that of other Slavic languages, is fusional; its nouns, verbs, and adjectives are inflected by phonological processes to modify their meanings and grammatical functions, and the easily separable affixes characteristic of agglutinative languages are limited.[46]

Czech inflects for case, gender and number in nouns and tense, aspect, mood, person and subject number and gender in verbs.[47]

Parts of speech include adjectives, adverbs, numbers, interrogative words, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections.[48] Adverbs are primarily formed from adjectives by taking the final ý or í of the base form and replacing it with e, ě, y, or o.[49] Negative statements are formed by adding the affix ne- to the main verb of a clause,[50] with one exception: je (he, she or it is) becomes není.[51]

Sentence and clause structure[edit]

A Czech-language sign at the entrance to a children’s playground

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | já | my |

| 2. | ty vy (formal) |

vy |

| 3. | on (masculine) ona (feminine) ono (neuter) |

oni (masculine animate) ony (masculine inanimate, feminine) ona (neuter) |

Because Czech uses grammatical case to convey word function in a sentence (instead of relying on word order, as English does), its word order is flexible. As a pro-drop language, in Czech an intransitive sentence can consist of only a verb; information about its subject is encoded in the verb.[52] Enclitics (primarily auxiliary verbs and pronouns) appear in the second syntactic slot of a sentence, after the first stressed unit. The first slot can contain a subject or object, a main form of a verb, an adverb, or a conjunction (except for the light conjunctions a, «and», i, «and even» or ale, «but»).[53]

Czech syntax has a subject–verb–object sentence structure. In practice, however, word order is flexible and used to distinguish topic and focus, with the topic or theme (known referents) preceding the focus or rheme (new information) in a sentence; Czech has therefore been described as a topic-prominent language.[54] Although Czech has a periphrastic passive construction (like English), in colloquial style, word-order changes frequently replace the passive voice. For example, to change «Peter killed Paul» to «Paul was killed by Peter» the order of subject and object is inverted: Petr zabil Pavla («Peter killed Paul») becomes «Paul, Peter killed» (Pavla zabil Petr). Pavla is in the accusative case, the grammatical object of the verb.[55]

A word at the end of a clause is typically emphasized, unless an upward intonation indicates that the sentence is a question:[56]

- Pes jí bagetu. – The dog eats the baguette (rather than eating something else).

- Bagetu jí pes. – The dog eats the baguette (rather than someone else doing so).

- Pes bagetu jí. – The dog eats the baguette (rather than doing something else to it).

- Jí pes bagetu? – Does the dog eat the baguette? (emphasis ambiguous)

In parts of Bohemia (including Prague), questions such as Jí pes bagetu? without an interrogative word (such as co, «what» or kdo, «who») are intoned in a slow rise from low to high, quickly dropping to low on the last word or phrase.[57]

In modern Czech syntax, adjectives precede nouns,[58] with few exceptions.[59] Relative clauses are introduced by relativizers such as the adjective který, analogous to the English relative pronouns «which», «that» and «who»/»whom». As with other adjectives, it agrees with its associated noun in gender, number and case. Relative clauses follow the noun they modify. The following is a glossed example:[60]

universit-u,

university-SG.ACC,

I want to visit the university that John attends.

Declension[edit]

In Czech, nouns and adjectives are declined into one of seven grammatical cases which indicate their function in a sentence, two numbers (singular and plural) and three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter). The masculine gender is further divided into animate and inanimate classes.

Case[edit]

A street named after Božena Němcová with her name declined in the genitive case (a sign probably from the time of the Protectorate).

A nominative–accusative language, Czech marks subject nouns of transitive and intransitive verbs in the nominative case, which is the form found in dictionaries, and direct objects of transitive verbs are declined in the accusative case.[61] The vocative case is used to address people.[62] The remaining cases (genitive, dative, locative and instrumental) indicate semantic relationships, such as noun adjuncts (genitive), indirect objects (dative), or agents in passive constructions (instrumental).[63] Additionally prepositions and some verbs require their complements to be declined in a certain case.[61] The locative case is only used after prepositions.[64] An adjective’s case agrees with that of the noun it modifies. When Czech children learn their language’s declension patterns, the cases are referred to by number:[65]

Some prepositions require the nouns they modify to take a particular case. The cases assigned by each preposition are based on the physical (or metaphorical) direction, or location, conveyed by it. For example, od (from, away from) and z (out of, off) assign the genitive case. Other prepositions take one of several cases, with their meaning dependent on the case; na means «onto» or «for» with the accusative case, but «on» with the locative.[66]

This is a glossed example of a sentence using several cases:

I carried the box into the house with my friend.

Gender[edit]

Czech distinguishes three genders—masculine, feminine, and neuter—and the masculine gender is subdivided into animate and inanimate. With few exceptions, feminine nouns in the nominative case end in -a, -e, or a consonant; neuter nouns in -o, -e, or -í, and masculine nouns in a consonant.[67] Adjectives, participles, most pronouns, and the numbers «one» and «two» are marked for gender and agree with the gender of the noun they modify or refer to.[68] Past tense verbs are also marked for gender, agreeing with the gender of the subject, e.g. dělal (he did, or made); dělala (she did, or made) and dělalo (it did, or made).[69] Gender also plays a semantic role; most nouns that describe people and animals, including personal names, have separate masculine and feminine forms which are normally formed by adding a suffix to the stem, for example Čech (Czech man) has the feminine form Češka (Czech woman).[70]

Nouns of different genders follow different declension patterns. Examples of declension patterns for noun phrases of various genders follow:

| Case | Noun/adjective | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big dog (m. anim. sg.) | Black backpack (m. inanim. sg.) | Small cat (f. sg.) | Hard wood (n. sg.) | |

| Nom. | velký pes (big dog) |

černý batoh (black backpack) |

malá kočka (small cat) |

tvrdé dřevo (hard wood) |

| Gen. | bez velkého psa (without the big dog) |

bez černého batohu (without the black backpack) |

bez malé kočky (without the small cat) |

bez tvrdého dřeva (without the hard wood) |

| Dat. | k velkému psovi (to the big dog) |

ke černému batohu (to the black backpack) |

k malé kočce (to the small cat) |

ke tvrdému dřevu (to the hard wood) |

| Acc. | vidím velkého psa (I see the big dog) |

vidím černý batoh (I see the black backpack) |

vidím malou kočku (I see the small cat) |

vidím tvrdé dřevo (I see the hard wood) |

| Voc. | velký pse! (big dog!) |

černý batohu! (black backpack!) |

malá kočko! (small cat!) |

tvrdé dřevo! (hard wood!) |

| Loc. | o velkém psovi (about the big dog) |

o černém batohu (about the black backpack) |

o malé kočce (about the small cat) |

o tvrdém dřevě (about the hard wood) |

| Inst. | s velkým psem (with the big dog) |

s černým batohem (with the black backpack) |

s malou kočkou (with the small cat) |

s tvrdým dřevem (with the hard wood) |

Number[edit]

Nouns are also inflected for number, distinguishing between singular and plural. Typical of a Slavic language, Czech cardinal numbers one through four allow the nouns and adjectives they modify to take any case, but numbers over five require subject and direct object noun phrases to be declined in the genitive plural instead of the nominative or accusative, and when used as subjects these phrases take singular verbs. For example:[71]

| English | Czech |

|---|---|

| one Czech crown was… | jedna koruna česká byla… |

| two Czech crowns were… | dvě koruny české byly… |

| three Czech crowns were… | tři koruny české byly… |

| four Czech crowns were… | čtyři koruny české byly… |

| five Czech crowns were… | pět korun českých bylo… |

Numbers decline for case, and the numbers one and two are also inflected for gender. Numbers one through five are shown below as examples. The number one has declension patterns identical to those of the demonstrative pronoun ten.[72][73]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | jeden (masc) jedna (fem) jedno (neut) |

dva (masc) dvě (fem, neut) |

tři | čtyři | pět |

| Genitive | jednoho (masc) jedné (fem) jednoho (neut) |

dvou | tří or třech | čtyř or čtyřech | pěti |

| Dative | jednomu (masc) jedné (fem) jednomu (neut) |

dvěma | třem | čtyřem | pěti |

| Accusative | jednoho (masc an.) jeden (masc in.) jednu (fem) jedno (neut) |

dva (masc) dvě (fem, neut) |

tři | čtyři | pět |

| Locative | jednom (masc) jedné (fem) jednom (neut) |

dvou | třech | čtyřech | pěti |

| Instrumental | jedním (masc) jednou (fem) jedním (neut) |

dvěma | třemi | čtyřmi | pěti |

Although Czech’s grammatical numbers are singular and plural, several residuals of dual forms remain, such as the words dva («two») and oba («both»), which decline the same way. Some nouns for paired body parts use a historical dual form to express plural in some cases: ruka (hand)—ruce (nominative); noha (leg)—nohama (instrumental), nohou (genitive/locative); oko (eye)—oči, and ucho (ear)—uši. While two of these nouns are neuter in their singular forms, all plural forms are considered feminine; their gender is relevant to their associated adjectives and verbs.[74] These forms are plural semantically, used for any non-singular count, as in mezi čtyřma očima (face to face, lit. among four eyes). The plural number paradigms of these nouns are a mixture of historical dual and plural forms. For example, nohy (legs; nominative/accusative) is a standard plural form of this type of noun.[75]

Verb conjugation[edit]

Czech verbs agree with their subjects in person (first, second or third), number (singular or plural), and in constructions involving participles, which includes the past tense, also in gender. They are conjugated for tense (past, present or future) and mood (indicative, imperative or conditional). For example, the conjugated verb mluvíme (we speak) is in the present tense and first-person plural; it is distinguished from other conjugations of the infinitive mluvit by its ending, -íme.[76] The infinitive form of Czech verbs ends in -t (archaically, -ti or -ci). It is the form found in dictionaries and the form that follows auxiliary verbs (for example, můžu tě slyšet—»I can hear you»).[77]

Aspect[edit]

Typical of Slavic languages, Czech marks its verbs for one of two grammatical aspects: perfective and imperfective. Most verbs are part of inflected aspect pairs—for example, koupit (perfective) and kupovat (imperfective). Although the verbs’ meaning is similar, in perfective verbs the action is completed and in imperfective verbs it is ongoing or repeated. This is distinct from past and present tense.[78] Any verb of either aspect can be conjugated into either the past or present tense,[76] but the future tense is only used with imperfective verbs.[79] Aspect describes the state of the action at the time specified by the tense.[78]

The verbs of most aspect pairs differ in one of two ways: by prefix or by suffix. In prefix pairs, the perfective verb has an added prefix—for example, the imperfective psát (to write, to be writing) compared with the perfective napsat (to write down). The most common prefixes are na-, o-, po-, s-, u-, vy-, z- and za-.[80] In suffix pairs, a different infinitive ending is added to the perfective stem; for example, the perfective verbs koupit (to buy) and prodat (to sell) have the imperfective forms kupovat and prodávat.[81] Imperfective verbs may undergo further morphology to make other imperfective verbs (iterative and frequentative forms), denoting repeated or regular action. The verb jít (to go) has the iterative form chodit (to go regularly) and the frequentative form chodívat (to go occasionally; to tend to go).[82]

Many verbs have only one aspect, and verbs describing continual states of being—být (to be), chtít (to want), moct (to be able to), ležet (to lie down, to be lying down)—have no perfective form. Conversely, verbs describing immediate states of change—for example, otěhotnět (to become pregnant) and nadchnout se (to become enthusiastic)—have no imperfective aspect.[83]

Tense[edit]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | budu | budeme |

| 2. | budeš | budete |

| 3. | bude | budou |

The present tense in Czech is formed by adding an ending that agrees with the person and number of the subject at the end of the verb stem. As Czech is a null-subject language, the subject pronoun can be omitted unless it is needed for clarity.[84] The past tense is formed using a participle which ends in -l and a further ending which agrees with the gender and number of the subject. For the first and second persons, the auxiliary verb být conjugated in the present tense is added.[85]

In some contexts, the present tense of perfective verbs (which differs from the English present perfect) implies future action; in others, it connotes habitual action.[86] The perfective present is used to refer to completion of actions in the future and is distinguished from the imperfective future tense, which refers to actions that will be ongoing in the future. The future tense is regularly formed using the future conjugation of být (as shown in the table on the left) and the infinitive of an imperfective verb, for example, budu jíst—»I will eat» or «I will be eating».[79] Where budu has a noun or adjective complement it means «I will be», for example, budu šťastný (I will be happy).[79] Some verbs of movement form their future tense by adding the prefix po- to the present tense forms instead, e.g. jedu («I go») > pojedu («I will go»).[87]

Mood[edit]

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | koupil/a bych | koupili/y bychom |

| 2. | koupil/a bys | koupili/y byste |

| 3. | koupil/a/o by | koupili/y/a by |

Czech verbs have three grammatical moods: indicative, imperative and conditional.[88] The imperative mood is formed by adding specific endings for each of three person–number categories: -Ø/-i/-ej for second-person singular, -te/-ete/-ejte for second-person plural and -me/-eme/-ejme for first-person plural.[89] Imperatives are usually expressed using perfective verbs if positive and imperfective verbs if negative.[90] The conditional mood is formed with a conditional auxiliary verb after the participle ending in -l which is used to form the past tense. This mood indicates hypothetical events and can also be used to express wishes.[91]

Verb classes[edit]

Most Czech verbs fall into one of five classes, which determine their conjugation patterns. The future tense of být would be classified as a Class I verb because of its endings. Examples of the present tense of each class and some common irregular verbs follow in the tables below:[92]

|

|

Orthography[edit]

The handwritten Czech alphabet, without a Q, W and X

Czech has one of the most phonemic orthographies of all European languages. Its alphabet contains 42 graphemes, most of which correspond to individual phonemes,[93] and only contains only one digraph: ch, which follows h in the alphabet.[94] The characters q, w and x appear only in foreign words.[95] The háček (ˇ) is used with certain letters to form new characters: š, ž, and č, as well as ň, ě, ř, ť, and ď (the latter five uncommon outside Czech). The last two letters are sometimes written with a comma above (ʼ, an abbreviated háček) because of their height.[96] Czech orthography has influenced the orthographies of other Balto-Slavic languages and some of its characters have been adopted for transliteration of Cyrillic.[97]

Czech orthography neatly reflects vowel length; long vowels are indicated by an acute accent or, occasionally with ů, a ring. Long u is usually written ú at the beginning of a word or morpheme (úroda, neúrodný) and ů elsewhere,[98] except for loanwords (skútr) or onomatopoeia (bú).[99] Long vowels and ě are not considered separate letters in the alphabetical order.[100] The character ó exists only in loanwords and onomatopoeia.[101]

Czech typographical features not associated with phonetics generally resemble those of most European languages that use the Latin script, including English. Proper nouns, honorifics, and the first letters of quotations are capitalized, and punctuation is typical of other Latin European languages. Ordinal numbers (1st) use a point, as in German (1.). The Czech language uses a decimal comma instead of a decimal point. When writing a long number, spaces between every three digits, including those in decimal places, may be used for better orientation in handwritten texts. The number 1,234,567.89101 may be written as 1234567,89101 or 1 234 567,891 01.[102] In proper noun phrases (except personal and settlement names), only the first word and proper nouns inside such phrases are capitalized (Pražský hrad, Prague Castle).[103][104]

Varieties[edit]

Josef Jungmann, whose Czech–German dictionary laid the foundations for modern Standard Czech

The modern literary standard and prestige variety, known as «Standard Czech» (spisovná čeština) is based on the standardization during the Czech National Revival in the 1830s, significantly influenced by Josef Jungmann’s Czech–German dictionary published during 1834–1839. Jungmann used vocabulary of the Bible of Kralice (1579–1613) period and of the language used by his contemporaries. He borrowed words not present in Czech from other Slavic languages or created neologisms.[105] Standard Czech is the formal register of the language which is used in official documents, formal literature, newspaper articles, education and occasionally public speeches.[106] It is codified by the Czech Language Institute, who publish occasional reforms to the codification. The most recent reform took place in 1993.[107] The term hovorová čeština (lit. «Colloquial Czech») is sometimes used to refer to the spoken variety of standard Czech.[108]

The most widely spoken vernacular form of the language is called «Common Czech» (obecná čeština), an interdialect influenced by spoken Standard Czech and the Central Bohemian dialects of the Prague region. Other Bohemian regional dialects have become marginalized, while Moravian dialects remain more widespread and diverse, with a political movement for Moravian linguistic revival active since the 1990s.

These varieties of the language (Standard Czech, spoken/colloquial Standard Czech, Common Czech, and regional dialects) form a stylistic continuum, in which contact between varieties of a similar prestige influences change within them.[109]

Common Czech[edit]

Dialects of Czech, Moravian, Lach, and Cieszyn Silesian spoken in the Czech Republic. The border areas, where German was formerly spoken, are now mixed.

The main Czech vernacular, spoken primarily in Bohemia including the capital Prague, is known as Common Czech (obecná čeština). This is an academic distinction; most Czechs are unaware of the term or associate it with deformed or «incorrect» Czech.[110] Compared to Standard Czech, Common Czech is characterized by simpler inflection patterns and differences in sound distribution.[111]

Common Czech is distinguished from spoken/colloquial Standard Czech (hovorová čeština), which is a stylistic variety within standard Czech.[112][113] Tomasz Kamusella defines the spoken variety of Standard Czech as a compromise between Common Czech and the written standard,[114] while Miroslav Komárek calls Common Czech an intersection of spoken Standard Czech and regional dialects.[115]

Common Czech has become ubiquitous in most parts of the Czech Republic since the later 20th century. It is usually defined as an interdialect used in common speech in Bohemia and western parts of Moravia (by about two thirds of all inhabitants of the Czech Republic). Common Czech is not codified, but some of its elements have become adopted in the written standard. Since the second half of the 20th century, Common Czech elements have also been spreading to regions previously unaffected, as a consequence of media influence. Standard Czech is still the norm for politicians, businesspeople and other Czechs in formal situations, but Common Czech is gaining ground in journalism and the mass media.[111] The colloquial form of Standard Czech finds limited use in daily communication due to the expansion of the Common Czech interdialect.[112] It is sometimes defined as a theoretical construct rather than an actual tool of colloquial communication, since in casual contexts, the non-standard interdialect is preferred.[112]

Common Czech phonology is based on that of the Central Bohemian dialect group, which has a slightly different set of vowel phonemes to Standard Czech.[115] The phoneme /ɛː/ is peripheral and usually merges with /iː/, e.g. in malý město (small town), plamínek (little flame) and lítat (to fly), and a second native diphthong /ɛɪ̯/ occurs, usually in places where Standard Czech has /iː/, e.g. malej dům (small house), mlejn (mill), plejtvat (to waste), bejt (to be).[116] In addition, a prothetic v- is added to most words beginning o-, such as votevřít vokno (to open the window).[117]

Non-standard morphological features that are more or less common among all Common Czech speakers include:[117]

- unified plural endings of adjectives: malý lidi (small people), malý ženy (small women), malý města (small towns) – standard: malí lidé, malé ženy, malá města;

- unified instrumental ending -ma in plural: s těma dobrejma lidma, ženama, chlapama, městama (with the good people, women, guys, towns) – standard: s těmi dobrými lidmi, ženami, chlapy, městy. In essence, this form resembles the form of the dual, which was once a productive form, but now is almost extinct and retained in a lexically specific set of words. In Common Czech the ending became productive again around the 17th century, but used as a substitute for a regular plural form.[118]

- omission of the syllabic -l in the masculine ending of past tense verbs: řek (he said), moh (he could), pích (he pricked) – standard: řekl, mohl, píchl.

- tendency of merging the locative singular masculine/neuter for adjectives with the instrumental by changing the locative ending -ém to -ým and then shortening the vowel: mladém (standard locative), mladým (standard instrumental) > mladým (Common Czech locative), mladym (Common Czech instrumental) > mladym (Common Czech locative/instrumental with shortening).[119]

Examples of declension (Standard Czech is added in italics for comparison):

| Masculine animate |

Masculine inanimate |

Feminine | Neuter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg. | Nominative | mladej člověk mladý člověk |

mladej stát mladý stát |

mladá žena mladá žena |

mladý zvíře mladé zvíře |

| Genitive | mladýho člověka mladého člověka |

mladýho státu mladého státu |

mladý ženy mladé ženy |

mladýho zvířete mladého zvířete |

|

| Dative | mladýmu člověkovi mladému člověku |

mladýmu státu mladému státu |

mladý ženě mladé ženě |

mladýmu zvířeti mladému zvířeti |

|

| Accusative | mladýho člověka mladého člověka |

mladej stát mladý stát |

mladou ženu mladou ženu |

mladý zvíře mladé zvíře |

|

| Vocative | mladej člověče! mladý člověče! |

mladej státe! mladý státe! |

mladá ženo! mladá ženo! |

mladý zvíře! mladé zvíře! |

|

| Locative | mladým člověkovi mladém člověkovi |

mladým státě mladém státě |

mladý ženě mladé ženě |

mladým zvířeti mladém zvířeti |

|

| Instrumental | mladym člověkem mladým člověkem |

mladym státem mladým státem |

mladou ženou mladou ženou |

mladym zvířetem mladým zvířetem |

|

| Pl. | Nominative | mladý lidi mladí lidé |

mladý státy mladé státy |

mladý ženy mladé ženy |

mladý zvířata mladá zvířata |

| Genitive | mladejch lidí mladých lidí |

mladejch států mladých států |

mladejch žen mladých žen |

mladejch zvířat mladých zvířat |

|

| Dative | mladejm lidem mladým lidem |

mladejm státům mladým státům |

mladejm ženám mladým ženám |

mladejm zvířatům mladým zvířatům |

|

| Accusative | mladý lidi mladé lidi |

mladý státy mladé státy |

mladý ženy mladé ženy |

mladý zvířata mladá zvířata |

|

| Vocative | mladý lidi! mladí lidé! |

mladý státy! mladé státy! |

mladý ženy! mladé ženy! |

mladý zvířata! mladá zvířata! |

|

| Locative | mladejch lidech mladých lidech |

mladejch státech mladých státech |

mladejch ženách mladých ženách |

mladejch zvířatech mladých zvířatech |

|

| Instrumental | mladejma lidma mladými lidmi |

mladejma státama mladými státy |

mladejma ženama mladými ženami |

mladejma zvířatama mladými zvířaty |

mladý člověk – young man/person, mladí lidé – young people, mladý stát – young state, mladá žena – young woman, mladé zvíře – young animal

Bohemian dialects[edit]

A headstone in Český Krumlov from 1591. The inscription features the distinctive Bohemian diphthong /ɛɪ̯/, spelled ⟨ey⟩.

Apart from the Common Czech vernacular, there remain a variety of other Bohemian dialects, mostly in marginal rural areas. Dialect use began to weaken in the second half of the 20th century, and by the early 1990s regional dialect use was stigmatized, associated with the shrinking lower class and used in literature or other media for comedic effect. Increased travel and media availability to dialect-speaking populations has encouraged them to shift to (or add to their own dialect) Standard Czech.[120]

The Czech Statistical Office in 2003 recognized the following Bohemian dialects:[121]

- Nářečí středočeská (Central Bohemian dialects)

- Nářečí jihozápadočeská (Southwestern Bohemian dialects)

-

- Podskupina chodská (Chod subgroup)

- Podskupina doudlebská (Doudleby subgroup)

- Nářečí severovýchodočeská (Northeastern Bohemian dialects)

-

- Podskupina podkrknošská (Krkonoše subgroup)

Moravian dialects[edit]

Traditional territory of the main dialect groups of Moravia and Czech Silesia. Green: Central Moravian, Red: East Moravian, Yellow: Lach (Silesian), Pink: Cieszyn Silesian, Orange: Bohemian–Moravian transitional dialects, Purple: Mixed areas

The Czech dialects spoken in Moravia and Silesia are known as Moravian (moravština). In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, «Bohemian-Moravian-Slovak» was a language citizens could register as speaking (with German, Polish and several others).[122] In the 2011 census, where respondents could optionally specify up to two first languages,[123] 62,908 Czech citizens specified Moravian as their first language and 45,561 specified both Moravian and Czech.[124]

Beginning in the sixteenth century, some varieties of Czech resembled Slovak;[13] the southeastern Moravian dialects, in particular, are sometimes considered dialects of Slovak rather than Czech. These dialects form a continuum between the Czech and Slovak languages,[125] using the same declension patterns for nouns and pronouns and the same verb conjugations as Slovak.[126]

The Czech Statistical Office in 2003 recognized the following Moravian dialects:[121]

- Nářečí českomoravská (Bohemian–Moravian dialects)

- Nářečí středomoravská (Central Moravian dialects)

-

- Podskupina tišnovská (Tišnov subgroup)

- Nářečí východomoravská (Eastern Moravian dialects)

-

- Podskupina slovácká (Moravian Slovak subgroup)

- Podskupina valašská (Moravian Wallachian subgroup)

- Nářečí slezská (Silesian dialects)

Sample[edit]

In a 1964 textbook on Czech dialectology, Břetislav Koudela used the following sentence to highlight phonetic differences between dialects:[127]

| Standard Czech: | Dej mouku ze mlýna na vozík. |

| Common Czech: | Dej mouku ze mlejna na vozejk. |

| Central Moravian: | Dé móko ze mléna na vozék. |

| Eastern Moravian: | Daj múku ze młýna na vozík. |

| Silesian: | Daj muku ze młyna na vozik. |

| Slovak: | Daj múku z mlyna na vozík. |

| English: | Put the flour from the mill into the cart. |

Mutual intelligibility with Slovak[edit]

Czech and Slovak have been considered mutually intelligible; speakers of either language can communicate with greater ease than those of any other pair of West Slavic languages.[128] Following the 1993 dissolution of Czechoslovakia, mutual intelligibility declined for younger speakers, probably because Czech speakers began to experience less exposure to Slovak and vice versa.[129] A 2015 study involving participants with a mean age of around 23 nonetheless concluded that there remained a high degree of mutual intelligibility between the two languages.[128] Grammatically, both languages share a common syntax.[13]

One study showed that Czech and Slovak lexicons differed by 80 percent, but this high percentage was found to stem primarily from differing orthographies and slight inconsistencies in morphological formation;[130] Slovak morphology is more regular (when changing from the nominative to the locative case, Praha becomes Praze in Czech and Prahe in Slovak). The two lexicons are generally considered similar, with most differences found in colloquial vocabulary and some scientific terminology. Slovak has slightly more borrowed words than Czech.[13]

The similarities between Czech and Slovak led to the languages being considered a single language by a group of 19th-century scholars who called themselves «Czechoslavs» (Čechoslované), believing that the peoples were connected in a way which excluded German Bohemians and (to a lesser extent) Hungarians and other Slavs.[131] During the First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938), although «Czechoslovak» was designated as the republic’s official language, both Czech and Slovak written standards were used. Standard written Slovak was partially modeled on literary Czech, and Czech was preferred for some official functions in the Slovak half of the republic. Czech influence on Slovak was protested by Slovak scholars, and when Slovakia broke off from Czechoslovakia in 1938 as the Slovak State (which then aligned with Nazi Germany in World War II), literary Slovak was deliberately distanced from Czech. When the Axis powers lost the war and Czechoslovakia reformed, Slovak developed somewhat on its own (with Czech influence); during the Prague Spring of 1968, Slovak gained independence from (and equality with) Czech,[13] due to the transformation of Czechoslovakia from a unitary state to a federation. Since the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, «Czechoslovak» has referred to improvised pidgins of the languages which have arisen from the decrease in mutual intelligibility.[132]

Vocabulary[edit]

Czech vocabulary derives primarily from Slavic, Baltic and other Indo-European roots. Although most verbs have Balto-Slavic origins, pronouns, prepositions and some verbs have wider, Indo-European roots.[133] Some loanwords have been restructured by folk etymology to resemble native Czech words (e.g. hřbitov, «graveyard» and listina, «list»).[134]

Most Czech loanwords originated in one of two time periods. Earlier loanwords, primarily from German,[135] Greek and Latin,[136] arrived before the Czech National Revival. More recent loanwords derive primarily from English and French,[135] and also from Hebrew, Arabic and Persian. Many Russian loanwords, principally animal names and naval terms, also exist in Czech.[137]

Although older German loanwords were colloquial, recent borrowings from other languages are associated with high culture.[135] During the nineteenth century, words with Greek and Latin roots were rejected in favor of those based on older Czech words and common Slavic roots; «music» is muzyka in Polish and музыка (muzyka) in Russian, but in Czech it is hudba.[136] Some Czech words have been borrowed as loanwords into English and other languages—for example, robot (from robota, «labor»)[138] and polka (from polka, «Polish woman» or from «půlka» «half»).[139]

Example text[edit]

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Czech:

- Všichni lidé rodí se svobodní a sobě rovní co do důstojnosti a práv. Jsou nadáni rozumem a svědomím a mají spolu jednat v duchu bratrství.[140]

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[141]

See also[edit]

- Czech Centers

- Czech name

- Czech Sign Language

- Swadesh list of Slavic words

Notes[edit]

- ^ Czech at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e «Full list». Council of Europe.

- ^ Ministry of Interior of Poland: Act of 6 January 2005 on national and ethnic minorities and on the regional languages

- ^ IANA language subtag registry, retrieved October 15, 2018

- ^ a b «Czech language». www.britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- ^ Swan, Oscar E. (2002). A grammar of contemporary Polish. Bloomington, Ind.: Slavica. p. 5. ISBN 0893572969. OCLC 50064627.

- ^ a b Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 54–56

- ^ Liberman & Trubetskoi 2001, p. 112

- ^ Liberman & Trubetskoi 2001, p. 153

- ^ a b Sussex & Cubberley 2011, pp. 98–99

- ^ Piotrowski 2012, p. 95

- ^ a b c d e Berger, Tilman. «Slovaks in Czechia – Czechs in Slovakia» (PDF). University of Tübingen. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2008). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Springer. pp. 134–135.

- ^ Michálek, Emanuel. «O jazyce Kralické bible». Naše řeč (in Czech). Czech Language Institute. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ a b Cerna & Machalek 2007, p. 26

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, p. 92

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, p. 95

- ^ a b Maxwell 2009, p. 106

- ^ Agnew 1994, p. 250

- ^ a b Agnew 1994, pp. 251–252

- ^ a b c Wilson 2009, p. 18

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, p. 96

- ^ Chloupek & Nekvapil 1993, pp. 93–95

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 2

- ^ a b «Europeans and Their Languages» (PDF). Eurobarometer. June 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-06-22. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ^ van Parys, Jonathan (2012). «Language knowledge in the European Union». Language Knowledge. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Škrobák, Zdeněk. «Language Policy of Slovak Republic» (PDF). Annual of Language & Politics and Politics of Identity. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Hrouda, Simone J. «Czech Language Programs and Czech as a Heritage Language in the United States» (PDF). University of California, Berkeley. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ «Chapter 8: Language» (PDF). Census.gov. 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ «Languages of the U.S.A» (PDF). U.S. English. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ^ Dankovičová 1999, p. 72

- ^ Campbell, George L.; Gareth King (1984). Compendium of the world’s languages. Routledge.

- ^ Dankovičová 1999, pp. 70–72

- ^ «Psaní i – y po písmenu c». Czech Language Institute. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 11

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 20–21

- ^ Dankovičová 1999, p. 73

- ^ Nichols, Joanna (2018). Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. p. 1607.

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 6

- ^ Dankovičová 1999, p. 71

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 5

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 12

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 9

- ^ «Sound Patterns of Czech». Charles University Institute of Phonetics. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Qualls 2012, pp. 6–8

- ^ Qualls 2012, p. 5

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. v–viii

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 61–63

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 212

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 134

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 74

- ^ Short 2009, p. 324.

- ^ Anderman, Gunilla M.; Rogers, Margaret (2008). Incorporating Corpora: The Linguist and the Translator. Multilingual Matters. pp. 135–136.

- ^ Short 2009, p. 325.

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 10–11

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 10

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 48

- ^ Uhlířová, Ludmila. «SLOVOSLED NOMINÁLNÍ SKUPINY». Nový encyklopedický slovník češtiny. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 271

- ^ a b Naughton 2005, p. 196

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 201

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 197–199

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 199

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 25

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 201–205

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 22–24

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 51

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 141

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 238

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 114

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 83

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 117

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 40

- ^ Komárek 2012, p. 238

- ^ a b Naughton 2005, p. 131

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 7

- ^ a b Naughton 2005, p. 146

- ^ a b c Naughton 2005, p. 151

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 147

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 147–148

- ^ Lukeš, Dominik (2001). «Gramatická terminologie ve vyučování – Terminologie a platonický svět gramatických idejí». DominikLukeš.net. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 149

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 134

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 140–142

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 150

- ^ Karlík, Petr; Migdalski, Krzysztof. «FUTURUM (budoucí čas)». Nový encyklopedický slovník češtiny. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Rothstein & Thieroff 2010, p. 359

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 157

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 159

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 152–154

- ^ Naughton 2005, pp. 136–140

- ^ Neustupný, J.V.; Nekvápil, Jiří. Kaplan, Robert B.; Baldauf, Richard B. Jr. (eds.). Language Planning and Policy in Europe. pp. 78–79.

- ^ Pansofia 1993, p. 11

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 1

- ^ Harkins 1952, pp. 6–8

- ^ Berger, Tilman. «Religion and diacritics: The case of Czech orthography». In Baddeley, Susan; Voeste, Anja (eds.). Orthographies in Early Modern Europe. p. 255.

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 7

- ^ Pansofia 1993, p. 26

- ^ Hajičová 1986, p. 31

- ^ Harkins 1952, p. 8

- ^ Členění čísel, Internetová jazyková příručka, ÚJČ AVČR

- ^ Naughton 2005, p. 11

- ^ Pansofia 1993, p. 34

- ^ Naughton, James. «CZECH LITERATURE, 1774 TO 1918». Oxford University. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Tahal 2010, p. 245

- ^ Tahal 2010, p. 252

- ^ Hoffmanová, Jana. «HOVOROVÝ STYL». Nový encyklopedický slovník češtiny. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ Koudela 1964, p. 136

- ^ Wilson 2009, p. 21

- ^ a b Daneš, František (2003). «The present-day situation of Czech». Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c Balowska, Grażyna (2006). «Problematyka czeszczyzny potocznej nieliterackiej (tzw. obecná čeština) na łamach czasopisma «Naše řeč» w latach dziewięćdziesiątych» (PDF). Bohemistyka (in Polish). Opole (1). ISSN 1642-9893. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-05.

- ^ Štěpán, Josef (2015). «Hovorová spisovná čeština» (PDF). Bohemistyka (in Czech). Prague (2). ISSN 1642-9893. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-10.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2008). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Springer. p. 506. ISBN 9780230583474.

- ^ a b Komárek 2012, p. 117

- ^ Komárek 2012, p. 116

- ^ a b Tahal 2010, pp. 245–253

- ^ Komárek 2012, pp. 179–180

- ^ Cummins, George M. (2005). «Literary Czech, Common Czech, and the Instrumental Plural». Journal of Slavic Linguistics. Slavica Publishers. 13 (2): 271–297. JSTOR 24599659.

- ^ Eckert 1993, pp. 143–144

- ^ a b «Map of Czech Dialects». Český statistický úřad (Czech Statistical Office). 2003. Archived from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Kortmann & van der Auwera 2011, p. 714

- ^ Zvoníček, Jiří (30 March 2021). «Sčítání lidu a moravská národnost. Přihlásíte se k ní?». Kroměřížský Deník. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ «Tab. 614b Obyvatelstvo podle věku, mateřského jazyka a pohlaví (Population by Age, Mother Tongue, and Gender)» (in Czech). Český statistický úřad (Czech Statistical Office). March 26, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Kortmann & van der Auwera 2011, p. 516

- ^ Šustek, Zbyšek (1998). «Otázka kodifikace spisovného moravského jazyka (The question of codifying a written Moravian language)» (in Czech). University of Tartu. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ Koudela 1964, p. 173

- ^ a b Golubović, Jelena; Gooskens, Charlotte (2015). «Mutual intelligibility between West and South Slavic languages». Russian Linguistics. 39 (3): 351–373. doi:10.1007/s11185-015-9150-9.

- ^ Short 2009, p. 306.

- ^ Esposito 2011, p. 82

- ^ Maxwell 2009, pp. 101–105

- ^ Nábělková, Mira (January 2007). «Closely-related languages in contact: Czech, Slovak, «Czechoslovak»«. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Mann 1957, p. 159

- ^ Mann 1957, p. 160

- ^ a b c Mathesius 2013, p. 20

- ^ a b Sussex & Cubberley 2011, p. 101

- ^ Mann 1957, pp. 159–160

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «robot (n.)». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «polka (n.)». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ «Universal Declaration of Human Rights». unicode.org.

- ^ «Universal Declaration of Human Rights». un.org.

References[edit]

- Agnew, Hugh LeCaine (1994). Origins of the Czech National Renascence. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-8549-5.

- Dankovičová, Jana (1999). «Czech». Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (9th ed.). International Phonetic Association/Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63751-0.

- Cerna, Iva; Machalek, Jolana (2007). Beginner’s Czech. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1156-9.

- Chloupek, Jan; Nekvapil, Jiří (1993). Studies in Functional Stylistics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-1545-1.

- Eckert, Eva (1993). Varieties of Czech: Studies in Czech Sociolinguistics. Editions Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-5183-490-1.

- Esposito, Anna (2011). Analysis of Verbal and Nonverbal Communication and Enactment: The Processing Issues. Springer Press. ISBN 978-3-642-25774-2.

- Hajičová, Eva (1986). Prague Studies in Mathematical Linguistics (9th ed.). John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-1527-7.

- Harkins, William Edward (1952). A Modern Czech Grammar. King’s Crown Press (Columbia University). ISBN 978-0-231-09937-0.

- Komárek, Miroslav (2012). Dějiny českého jazyka (in Czech). Brno: Host. ISBN 978-80-7294-591-7.

- Kortmann, Bernd; van der Auwera, Johan (2011). The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide (World of Linguistics). Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022025-4.

- Koudela, Břetislav; et al. (1964). Vývoj českého jazyka a dialektologie (in Czech). Československé státní pedagogické nakladatelství.

- Liberman, Anatoly; Trubetskoi, Nikolai S. (2001). N.S. Trubetzkoy: Studies in General Linguistics and Language Structure. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2299-3.

- Mann, Stuart Edward (1957). Czech Historical Grammar. Helmut Buske Verlag. ISBN 978-3-87118-261-7.

- Mathesius, Vilém (2013). A Functional Analysis of Present Day English on a General Linguistic Basis. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-3077-4.

- Maxwell, Alexander (2009). Choosing Slovakia: Slavic Hungary, the Czechoslovak Language and Accidental Nationalism. Tauris Academic Studies. ISBN 978-1-84885-074-3.

- Naughton, James (2005). Czech: An Essential Grammar. Routledge Press. ISBN 978-0-415-28785-2.

- Pansofia (1993). Pravidla českého pravopisu (in Czech). Ústav pro jazyk český AV ČR. ISBN 978-80-901373-6-3.

- Piotrowski, Michael (2012). Natural Language Processing for Historical Texts. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60845-946-9.

- Qualls, Eduard J. (2012). The Qualls Concise English Grammar. Danaan Press. ISBN 978-1-890000-09-7.

- Rothstein, Björn; Thieroff, Rolf (2010). Mood in the Languages of Europe. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-0587-2.

- Short, David (2009). «Czech and Slovak». In Bernard Comrie (ed.). The World’s Major Languages (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 305–330.

- Scheer, Tobias (2004). A Lateral Theory of Phonology: What is CVCV, and why Should it Be?, Part 1. Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017871-5.

- Stankiewicz, Edward (1986). The Slavic Languages: Unity in Diversity. Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-009904-1.

- Sussex, Rolan; Cubberley, Paul (2011). The Slavic Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. ISBN 978-0-521-29448-5.

- Tahal, Karel (2010). A grammar of Czech as a foreign language. Factum.

- Wilson, James (2009). Moravians in Prague: A Sociolinguistic Study of Dialect Contact in the Czech. Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-3-631-58694-5.

External links[edit]

Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Czech.

Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Czech

- Ústav pro jazyk český – Czech Language Institute, the regulatory body for the Czech language (in Czech)

- Czech National Corpus

- Czech Monolingual Online Dictionary

- Online Translation Dictionaries

- Czech Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary’s Swadesh-list appendix)

- Online Czech Grammar and Exercises

Czenglish. Have you ever heard this term? It’s been a hot topic lately, mostly due to the vigorous power of the internet and social media. Nowadays, everybody loves YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and…influencers!

Although you won’t find a lot of similarities between Czech and English (with the exception of words derived from Latin), English is seeping into the Czech language more and more.

By the way, the phenomenon of English words used in Czech is not as new as it might seem! I was watching a Czech comedy from 1938 a couple of days ago, and one of the first scenes is a perfect example of Czenglish used in real life: Já changuju subject? Ty changuješ subject! (“I am changing the subject? You are changing the subject!”). We like using English words. We adopt them, lovingly decline and conjugate them, adjust the pronunciation to our liking, and make them our own.

Yup, it’s very convenient to speak more languages because (besides other, more prominent and useful advantages) it gives you the option to pick your favorite words and use them as you please! I am guilty of using English words in Czech convos, and it makes my grandma very confused at times!

There are also words that you probably consider English…which are actually Czech!

Let’s get into it! In this article, we’ll look at Czech words you’ve been using without realizing it, Czenglish, and Czech words of English origin.

I’ll make sure I never make this mistake again.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Czenglish

- Czenglish Examples

- Loanwords vs. Czenglish: List of English Words in the Czech Language

- Foreign Brands, Titles, and Names in Czech

- Czech Words in English: Did You Know?

- How CzechClass101.com Can Help You Learn Czech in a Fun Way

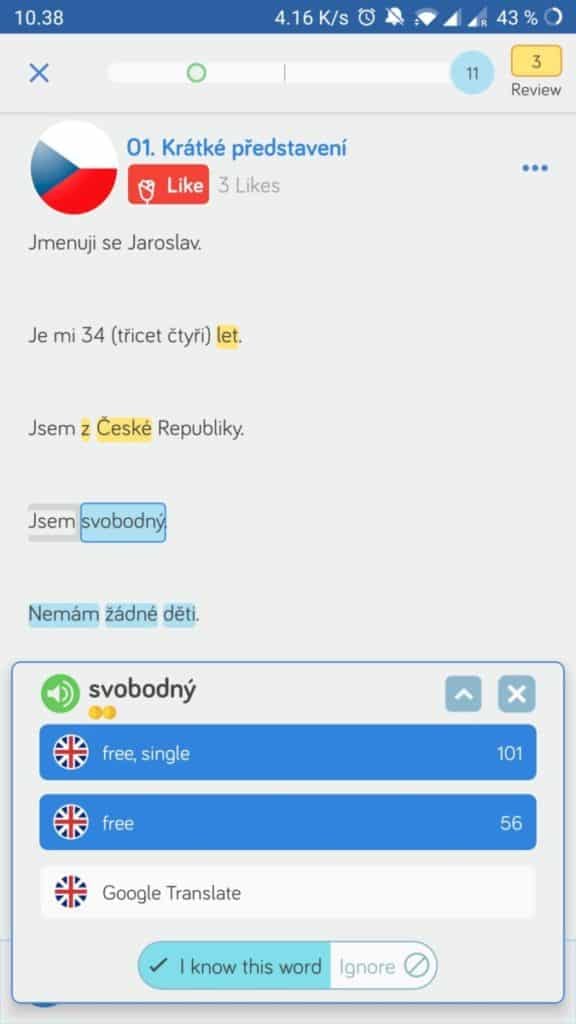

Introduction to Czenglish

The term ‘Czenglish’ was first introduced in 1989 by Don Sparling, a Canadian professor at the Masaryk University in Brno (1977-2009), who’s also the author of English or Czenglish?

So, what is the definition of Czenglish?

- ➢ Czenglish is a version of the English language spoken by Czech learners of English. It is heavily influenced by Czech vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, or syntax.

Czenglish mistakes might include a wide variety of “abominations,” such as:

Incorrect pronunciation

For example:

- /θ/ is often pronounced as [s], [t], or [f].

- “Thing” in Czech sounds more like “sink,” “tink,” or “fink.”

- /ð/ is often pronounced as [d].

- “They” is pronounced “dey.”

- /r/ has the typical rolling rumble to it.

Voiced consonants pronounced as unvoiced

Voiced consonants (B, D, G, J, L, M, N, Ng, R, Sz, Th as in “they,” V, W, Y, and Z) are made by vibrating the vocal cords. Unvoiced consonants…yes, you guessed it! Your vocal cords can take a break while pronouncing these: Ch, F, K, P, S, Sh, T, and Th (as in “thing”).

Czech natives, however, often pronounce them incorrectly. Which is no biK deal, but it sounds funny. I’m sure you’ve hearT a lot of Dose. Am I rrrright?

Omission of articles

It’s no wonder Czechs make this mistake, as there are no articles in the Czech language. Most Czech natives find them…redundant. Why bother, when it’s just a few letters (or even a single one)? Another thing you might encounter while talking to Czechs is the use of “some” in place of an indefinite article.

Literal translations

This is a big one. And given the stark difference between the Czech and English word order, there’s a good chance you’ll get lost in translation quite often.

Czenglish Examples

This part should be easy to write since I’m the “uncrowned queen of Czenglish” and sometimes it’s hard for my mouth to keep up with my mind, so…here it goes.

- “Basic school”

Got it? Basic school is the literal translation of základní škola (“elementary school”). I’ve heard this one way too many times to ever forget it. Základní means “basic” in Czech.

- “She said me that my English is great!”

Řekla mi, že moje angličtina je skvělá!

While in English, you might say “She said to me that my English is great,” omitting prepositions is very common in word-for-word translations. It can lead to some very funny situations…

- “I am watching on TV.”

Dívám se na televizi.

Generally speaking, the Czech language uses prepositions where English doesn’t, and vice-versa. Na means “on.”

- “Riding on bike”

Jet na kole.

This is a perfect example of preposition errors in literal translations.

- “I can English.”

Umím anglicky.

Mluvit means “to speak.” In Czech, we don’t say: Umím mluvit anglicky.

- A: “Hey, I don’t like it.” / B: “Me too.”

A: “Hele, nelíbí se mi to.” / B: “Mně taky.”

Shrug. That’s how Czech works, folks!

- Using the word “please” instead of “ask”

Oh my gosh, this mistake can actually be pretty embarrassing because “to please” has a very different meaning in English, and it’s similar to the Czech potěšit (“to make happy”). Not cute.

Poprosit (“to ask”) is derived from the word prosím (“please”), and for the average Czech, it totally makes sense to “please you to do something.”

To give you an example, the sentence Poprosil mě, abych něco řekl (“He asked me to say something”) would be incorrectly translated as “He pleased me to say something” (Potěšil mě, abych něco řekl).

I suppose you’ll want to avoid such mistakes in Czech! That’s why you should check out our list of 100 Core Czech Words and Key Czech Phrases!

Some Czenglish words sound adorable.

Loanwords vs. Czenglish: List of English Words in the Czech Language

Loanwords are “borrowed” from English without significant changes and tend to be easily understood by native English speakers.

This phenomenon has grown in popularity due to YouTube and social media, and we often use social media-related terms without changing them. However, we apply declension and conjugation in order to make them work in a Czech sentence.

We do use heavily altered (or even pure Czech) words when talking about technology, though. Check them out here.

Young Czechs use a lot of English words, mostly due to social media and influencers.

Here are some commonly used English words in Czech:

- Blog / blogging / blogovat (“to blog”)

- the noun is declined as masculine inanimate

- Lobbing

- masculine inanimate

- Barman (“bartender”)

- masculine animate

- This one only works in masculine, though. We like to be super-specific with grammatical gender, so the feminine version is barmanka.

- Blok (“block”), blokovat (“to block”)

- masculine inanimate

- Sendvič (“sandwich”)

- masculine animate

- Galon (“gallon”)

- masculine inanimate

- Klub (“club” as in “facility”)

- masculine inanimate

- Svetr (“sweater” or “jumper”)

- masculine inanimate

- Followers / followeři

- masculine animate

- Views

- not declined

- Stories (as in “Insta stories”)

- not declined

- Intro

- neuter

- Trailer (as in a movie trailer)

- masculine inanimate

- Internet

- masculine inanimate

- Web (pronounced with a “v”)

- masculine inanimate

- Chat (when referring to an online conversation)

- masculine inanimate

- Email

- masculine inanimate

- Smartphone

- masculine inanimate

- Spoiler

- masculine inanimate

- Korporát (“corporate”)

- Brainstorming

- masculine inanimate

- Mainstream

- masculine inanimate

- Steak

- masculine inanimate

- Filet (“fillet”)

- masculine inanimate

- Cheesecake

- masculine inanimate

- Cupcake

- masculine inanimate

- Cookie

- neuter

- Brownie

- neuter

- Manager

- masculine animate

- Management / Marketing

- masculine inanimate

- Business

- masculine inanimate

Please note:

- ➢ All loanwords, even those that remain unchanged, are pronounced the Czenglish way and you might not recognize them when you hear them…

Just sayin’.

You might have noticed that a lot of these borrowed words are office- or work-related. But you’ll still need to know some Czech vocabulary to talk about your workplace!

Foreign Brands, Titles, and Names in Czech

There is one thing that technically doesn’t belong to Czenglish, but I get asked about it A LOT.

Angela MerkelOVÁ

Sigourney WeaverOVÁ

Anna BoleynOVÁ

In Czech and other Slavic languages, the suffix -ová is added to the last names of all females. Back in the day, it literally meant “belonging to…,” and somehow, it never went away. Are you wincing now?

Lately, more women choose to go by their husband’s last name without the -ová, which means they have to literally lie to the authorities when applying for their new documents. You have to confirm that you’re either going to move abroad or have married a foreigner in order to be allowed to choose your own name. I’m not kidding.

There’s one advantage to this whole “belonging to” thing: it makes it clear whether a person is male or female immediately.

Now back to Czenglish!

Do we translate foreign titles? Yup. Some of them. Any rules? No.

Look:

- Star Wars – Hvězdné války (literal translation, same meaning)

- Pretty Woman – Pretty woman

- Misson: Impossible – Mission: Impossible

- Inception – Počátek (literal translation is “beginning,” but vnuknutí [meaning “suggestion”] would be more accurate)

However, titles are created based on specific instructions from Hollywood headquarters before the creators have seen the actual movie, which definitely makes the job harder.

Hvězdné války – Yoda.

P.S.: We also omit the ‘90210’ from Beverly Hills, 90210 and pronounce Nike as Nik.

By the way, if you’re going to the movies in the Czech Republic, check out our specialized movie vocab list first!

Czech Words in English: Did You Know?

There are words you probably consider English, but…

Bohemisms or Czechisms are words derived from the Czech language, and many of them originate in Latin. Let’s look at a couple of English words from Czech you’ve heard at least once before:

Robot

This word was first coined by the Czech playwright, novelist, and journalist Karel Čapek (1880-1938), who introduced it in his 1920 sci-fi play, R.U.R., or Rossum’s Universal Robots. It’s derived from the old Slavonic word robota, which literally means “forced labor.”

Čapek first named these creatures laboři, but didn’t really like it. At the suggestion of his brother, artist and author Josef Čapek, he later opted for roboti (“robots”).

Robot or labor?

In case you’re interested: The play is pretty awesome, and there’s an English version as well. It’s pretty ironic that R.U.R. was his least favorite work.

By the way, Čapek was close friends with the first Czechoslovak president, a passionate democrat (although he wasn’t directly involved in politics), and strictly against totalitarian regimes. Some of his works were considered “subversive,” and as such, were hated by the rising Nazi party. He died of the flu in December 1938.

Polka

This popular folk dance (and the word used to describe it) originated in the mid-nineteenth century. It’s drawn from the word půlka (“half”), and refers to the short half-steps and rhythm of the dance.

The word became widely popular in the major European languages in the early 1840s.

How CzechClass101.com Can Help You Learn Czech in a Fun Way

That’s it, guys! I hope you enjoyed this article and learned something new! Did any of the words we listed surprise you?

If you’re taking your Czech learning seriously, you could grab a Czech grammar book or learn online (the latter of which is way more convenient).

CzechClass101.com will make learning Czech easy, exciting, and fun. With us, it’s not about endless memorizing or thick textbooks. Learn Czech with us and make progress faster than you could imagine!

What can you find here?

- English-to-Czech translation and pronunciation tips/tricks

- Over 630 audio and video lessons

- Vocabulary learning tools

- Spaced repetition flashcards

- Detailed PDF lesson notes

Sign up now—it’s free!

The official language of the Czech Republic (and, of course, its capital), is Czech. You will not find many foreigners speaking the language, which is only spoken in Czechia and is very difficult to learn. Nevertheless, you do not need to worry about not being able to understand and make yourself understood during your visit to Prague, because you can easily communicate in English there.

Czechs (including, of course, Praguers) are a nation belonging to the West Slavic ethnic group. The official language of Prague is thus Czech (“čeština” in Czech). It is a West Slavic language (influenced a lot by Latin and German), very difficult to learn, and used officially nowhere else in the World. The Czech language is very similar to the Slovakian language (used in the neighbouring Slovakian Republic). Many words are adopted from English into the modern Czech language.

History of the Czech Language

The Czech language developed from common West Slavic at the end of the 1st millennium. It was only in the 14th century when the language started to be used in literature and official communication. The king of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV had the Bible translated to Czech around this time.

At the turn of the 14th and 15th century, the famous religious reformer Jan Hus started to advocate a reformation of the Czech language, which resulted in using diacritic marks in the future. After the defeat of the Czech uprising of the estates (the historical period of 1618-1620, during which the social class of estates fought against the Hapsburg reign), the Czech language was in decline until the end of the 18th century, when the Czech National Revival started, upgrading the language and strongly supporting its use.

The modern Czech language is very rich, interesting, and complicated. Czech grammaffur is fusional: its nouns, verbs, and adjectives are inflected by phonological processes to modify their meanings and grammatical functions. Nouns and adjectives are declined in seven different grammatical cases.

Languages Spoken in Prague

Since Prague is multi-cultural and many expatriates from various countries live here, you can hear a lot of different languages in the Czech Republic’s capital. There are almost 200 thousand foreigners living in Prague. The largest group is of the Ukrainian origin, and many people come from Slovakia, Russia, and Vietnam (surprisingly), too.

Even though only about one fifth of all Czechs speak a foreign language at an advanced level, it is much better in Prague. Most often, Czechs have a good command of English, with the second most “popular” foreign language being German and the third one Russian. French, Italian, and Spanish are not widely spoken by the locals.

English in Prague

In Prague, a great number of native citizens speak English at least a bit. And at the tourist hotspots, restaurants in the centre, hotels, and gift shops, knowledge of the English language is taken for granted. Of course, all the tourist spot attendants speak English very well, and cab drivers, waiters, hotel concierges, and people working at the airport do too. You will also find information, instructions, rules, and other writings in English in many places. On the other hand, do not expect much English from the Czech police officers or bus drivers.

Of course, knowledge of the English language gets better with higher education, however older people in the Czech Republic quite often do not speak English at all. Russian and German are more common in their case, due to the periods of Czech history when Germany and Russia (the former Soviet Union) had a large influence on the Czech Republic.

Learn Some Czech