Presentation on theme: «Word, Language, and Thought»— Presentation transcript:

1

Word, Language, and Thought

Félix Fénéon Word, Language, and Thought Per Aage Brandt Cwru

2

Language as a system? Ferdinand de Saussure distinguished in language the system (la langue) and the use (la parole). The system, main subject of linguistics, would be a network of words defining the specific ‘language’ – like French, Wolof, etc. However, words do not form a finite network So what can we do to define linguistics?

3

The stratification of structure in language

Morphemes apply to all strata in language: (From P. Aa. Brandt, « Analytique, sémiotique et ontologie dans le projet glossématique »).

4

Morphemes define a language

WORDS comprise two parts: lexemes and morphemes, and can be either the lexeme only or the morpheme only. Lexemes, open class, express CATEGORIES Morphemes, closed class, express SCHEMAS

5

Lexematic CATEGORIES Animal –> horse –> mare …

Tool –> hammer –> gavel … Furniture –> table –> console … Categories have central prototypes and often have peripheral hybrid tokens (cf. telephones) Categories inform terminologies but not closed network, so they cannot define languages.

6

Morphematic SCHEMAS Morphemes are the expressions of conceptual schemas that organize thinking by language. Examples: From and To –

7

Another example: quantifiers

All / some / no(ne)

8

Linguistic structure can be seen as an array of structures, all related to words

The spiral of language

9

Enunciation is one of these structures, or ‘components’

I say to you that X = Sa –> Sé –> Ref(R)

10

“In a café on Rue Fontaine, Vautour, Lenoir, and Atanis exchanged a few bullets regarding their wives, who were not present.” F. Fénéon Syntax –

11

“In a café on Rue Fontaine, Vautour, Lenoir, and Atanis exchanged a few bullets regarding their wives, who were not present.” Félix Fénéon, Nouvelles en trois lignes (1906, 2015). SEMANTIC SCHEMATISATION OF SITUATION WITH EXCHANGE

12

Sentence semantics and discourse semantics

What the sentence means is represented as a categorized schema of a scenario (such as the scenario of the shooting in the café). What the text by Fénéon means is represented as an encyclopedic, discurisve semantic network of cultural meanings implied by the sentence in context.

13

Conclusion A language is a vocabulary with typical unfoldings in the five components of any language: All words can have properties that determine structure in all five components: text – performance thought grammar imagination

Can we think about something without knowing its name? Does the language we speak change how we see the world? The relationship between thought and language might be a complicated one. Psychologists often attribute varying degrees of importance to the role of language in the development of cognition and vice versa. In this explanation, we will compare how different theories conceptualise this relationship.

- First, we will discuss language and thought in psychology.

- We will delve into the relationship between language and thought, highlighting the theories of language and thought as we go along.

- Finally, we will discuss some of the famous theorists involved in the relationship between language and thought, namely Piaget, Chomsky, and Vygotsky, whilst also covering the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

Language and Thought Psychology

Language is one of the systems through which we communicate, and it typically involves communicating through sounds and written communication with the use of symbols, but it can also involve our bodies (body language, how we smile, move, and approach people are all forms up for interpretation in the game of language).

Language is often closely related to the culture that uses it and reflects culturally relevant ideas.

Many languages have words that are not present at all in others.

For example, there is no English equivalent to the German word schadenfreude, which refers to the experience of pleasure caused by witnessing another person’s adversity.

As we also tend to think using language, Sapir-Whorf theorised that the language we use will affect how we see and think of the world. However, Piaget highlights that children develop schemas before they are capable of speaking, suggesting that cognitive processes do not depend on language.

Relationship Between Language and Thought

Different theories propose different relationships between language and thought. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development argues that children’s ability to use language and the content of their speech depends on their stage of cognitive development.

In contrast, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis proposes that the language we use to communicate determines how we think of the world around us, affecting cognitive processes like memory and perception.

Theories of Language and Thought

The two main theories representing different perspectives on language and thought you should know about are Piaget’s theory and the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

Piaget’s stage theory of cognitive development

According to Piaget’s theory, language is preceded by and depends on thought. Before children can use words correctly they need to first develop an understanding of the concepts behind them.

This occurs through the development of schemas, a process which precedes language development.

Schemas refer to mental frameworks that guide children’s behaviour and expectations.

According to this view, to communicate their dislike of broccoli, a child needs to first develop a schema about not liking it. Having developed the schema and expectations about how broccoli tastes the child can express their dislike.

Children can be taught phrases like «no broccoli» before they ever see or try it but they won’t be able to use it in a meaningful way until they understand what the phrase means.

The stage of a child’s cognitive development will also limit their ability to communicate meaningfully. In this way, language depends on thoughts.

For example, a child who is not yet able to mentally represent the perspective of another person will not be able to talk about it or account for it when they talk to others.

Let’s take a look at how the linguistic abilities of a child correspond to their stage of cognitive development.

| Stage of development | Age | Language development |

| Sensorimotor stage — children explore the world through their senses and motor movements. | 0-2 years | Children are able to imitate sounds and vocalise their demands. |

| Preoperational stage — children begin to think symbolically, form ideas and represent images mentally. Children may not be able to reason logically and see beyond their egocentric perspective. | 2-7 years | Children begin to use private speech, which according to Piaget reflects their egocentrism. They still lack the ability to maintain a two-way conversation and take the perspective of the other person they communicate with. |

| Concrete operational stage — children start to recognise the perspectives of others but may still struggle with some logical thought and abstract ideas. | 7-11 years | Children start to adopt the perspectives of others in conversations. The conversations they engage in are limited to discussing concrete things. Children recognise how events are placed in time and space. |

| Formal operational stage — children are able to reason hypothetically, and logically, think abstractly and solve problems in a systematic manner. | 12+ years | Children can discuss abstract ideas and see different perspectives. |

Evaluation of the theories of language and thought

While Piaget’s theory appears to make sense and has some face validity, it generally lacks empirical support. This is due to the difficulties of studying cognitive and thought processes like schema development in pre-linguistic children.

The concept of universal stages of cognitive development has also been widely criticised. Some studies have found that children can attain many of these developmental milestones earlier than proposed by Piaget.

Differences in cognitive development have also been found across cultures, suggesting that Piaget’s idea of cognitive development was culturally biased (Mangan, 1978).

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

The central idea behind the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that our native language affects how we think about the world. The words we use to create narratives about the world influence how we represent it internally.

According to this view, we can only hold mental representations of the concepts we can name. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis supports the idea of linguistic determinism.

Linguistic determinism is the idea that the language we use determines and constrains how we think about the world. The weaker version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has been termed linguistic relativity, this idea proposes that while language may not completely determine our thoughts it can influence them to some extent.

Whorf supported his claims with research on native American cultures. He proposed that differences in language can change how a culture understands the concept of time or how it perceives natural phenomena.

Whorf argued that the Native American Hopi culture lacks an understanding of the concept of time. He attributed this to the lack of terminology that places events in time in their language. According to his theory, the lack of linguistic expression of time changed the way this culture thought of and understood time.

He also pointed to the fact that the Inuit language has a lot more words for snow than the English language, suggesting that the Inuit culture perceives snow differently from Europeans and is able to distinguish between different types of snow.

Evaluation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

The original examples in support of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis have been refuted. It was found that the Hopi language does have a way of expressing time. Moreover, the number of Inuit word’s for snow has been shown to be largely exaggerated by Whorf as the true number is around 4.

However, later psycholinguistics research has found some evidence of differences in memory and perception across speakers of different languages, supporting linguistic relativism.

Studies have found that our native language can influence how we remember past events as well as how good we are at recognising differences between colours.

Fausey and Broditsky (2011) investigated the memory of intentional and accidental events in English and Spanish speakers. Both groups remembered the person responsible for intentional actions equally well. However, English speakers had a much better memory of the agent behind the accidental action compared to Spanish speakers.

The difference in memory found in the study of Fausey and Broditsky (2011) was attributed to linguistic differences between English and Spanish. In Spanish accidents are typically described with non-agentive language. For example, Spanish speakers would use the expression «A pen broke» instead of «A man broke the pen» to describe a pen accidentally breaking.

Winawer et al. (2006) investigated the ability of English and Russian speakers to discriminate between different shades of blue. The different shades have distinct names in the Russian language, but not in the English language.

Russian speakers were much better at discriminating between the colours. This effect was attributed to how the Russian language categorises the shades of blue.

Other Theories of Language and Thought

Other developmental conceptualisations of language include the theories of Chomsky and Vygotsky. Chomsky focuses on how children acquire linguistic abilities at such a young age. Vygotsky’s theory highlights how language drives further cognitive development in children.

Language and Thought Chomsky

Chomsky proposed that language acquisition is an innate ability. Children are already born with the ability to acquire the rules that govern languages. Grammatical rules are common to all languages even though they might differ across them.

An innate ability to acquire grammatical structures of a language allows children to quickly learn the language, even based on the limited linguistic input they receive in infancy.

Language and Thought Vygotsky

According to Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development, in early development speech and thought are independent. The two processes merge when speech is internalised. In Vygotsky’s theory, language is considered to be a cultural tool that plays a key role in development.

-

Firstly, verbal guidance from adults supports children’s learning and development. Language allows adults to share their knowledge and communicate with the child.

-

Secondly, when language becomes internalised and develops into inner speech, it allows children to guide themselves when making decisions, problem-solving or regulating their behaviour.

Language and Thought — Key Takeaways

- Piaget’s theory proposes that language is preceded by thought during development. Moreover, children’s ability to use language is constrained by their stage of cognitive development.

- The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis proposes that the language we use determines how we think of the world around us, affecting cognitive processes like memory and perception.

- Whorf used examples from Native American culture to support his claims.

- The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has received some empirical support. Studies have found that our native language can influence how we remember past events as well as how good we are at recognising differences between colours.

- Chomsky proposed that the ability to acquire language is innate.

- According to Vygotsky, language plays a key role in development. Language can be used to provide children with verbal guidance. Later, when children internalise it, language helps them solve problems and regulate their behaviour.

This article proposes a new account of the general architecture of language, based on the word and on the processual unity of Saussurean parole and langue in the dynamical cognitive reality of language. Language is process, usage, text, and a capacity, a competence. A

literary example, from Félix Fénéon, is offered. It is argued that words have properties affecting every substructure in language and additionally constitute the threshold between language and thought.

Keywords:

Félix Fénéon;

Word;

cognitive linguistics;

discourse semantics;

enunciation;

semantic schemas;

stemmatic syntax

Document Type: Research Article

Affiliations:

Department of Cognitive Science, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA

Publication date:

02 January 2018

Post Views: 21,327

Language is all around us. It allows me to write this article, and you to read it. Our ability to communicate using language is what makes us human; our words harness so much more power than we often realise. As I tap on my keyboard, I connect letter to letter, then word to word, sentence to sentence. Your eyes will see this article through a screen, and your brain will take these observations and transform them into thoughts. This process is what gives language a meaning.

With this ability, we humans are able to transmit our ideas across vast reaches of space and time. We can transmit knowledge between minds. I can put a bizarre new idea in your mind right now. Imagine… a kangaroo tap dancing in a bakery. That’s a thought you probably haven’t had before. But now, using language, I’ve made you think it.

Of course, there isn’t just one language in the world. In fact, there are about 7000 and they all differ in many ways. They may have different sounds, vocabularies and, most importantly, different structures. This raises the age-long question: does the language we speak shape the way we think? The Japanese writer Haruki Murakami said ‘Learning another language is like becoming another person’. This suggests language forms our reality by influencing the way we interpret things. However, some would disagree, claiming that it’s the way we think that forms our language, not vice versa. This confusion introduces us to the dilemma of reflectionism versus determinism; two linguistic approaches to understanding how language and thoughts are connected.

If language controls thought…

The idea that the language we learn to speak and hear controls the way we think is called linguistic determinism. It’s most commonly known as the Sapir-Whorf theory, named after the American linguist Edward Sapir and his student Benjamin Lee Whorf. In 1929, Sapir argued that humans are ‘at the mercy of the particular language which has become the medium of expression for their society’. Essentially, the words we’re surrounded by become our own thoughts by influencing our interpretations without choice.

Meanwhile, Whorf had not set out to make himself a big name in the field of linguistics. Originally, he had been an inspector for a fire insurance company. However, he noticed a surprising safety hazard in his line of work – and it all came down to language. When people read the word ’empty’ on the gasoline drums, Whorf noticed they were much less careful about handling them, even though the vapor inside was just as dangerous as the full drums. This demonstrated to Whorf how language directly affected what people thought, and inspired him to further study this topic.

Linguistic relativity is something we will discuss in line with determinism. It follows the same principle that language controls thought, but it’s not quite as extreme. Relativity is the idea that people who speak different languages perceive and think about the world quite differently. This is different to determinism as it doesn’t commit to the harsh claim that our language must constrain our thoughts.

Lost in translation

‘Lost in translation’ is an idiom you may be familiar with and it’s an excellent way to summarize relativity. A work loses its meaning from the interpretation of its original language when translated into another.

The importance of the ‘loss’ varies, of course. Many consider literary writing to be the most significant issue. We can note how one poet felt about the translation of his poems from the original Spanish into other languages. Pablo Neruda said that translations of his poems into English and French can’t correspond to Spanish in the placement, color or weight of the words. He continues to explain that although all the correct meaning can be translated, his “poetry escapes”. He protests “it says the same thing one has written. But it is obvious that if I had been a French poet, I would not have said what I did in that poem, because the value of words is so different”.

Another good example of linguistic relativity is how grammatical gender affects interpretation. For decades, researchers have been contemplating whether gendered language (i.e. masculine and feminine) influences the way we think about things. Whorf believed that distinctions unique to a language morph a certain way of acting and perceiving the world. According to his theory, speaking a different language inherently changes one’s perceptions and behaviors. Whilst modern cognitive science has dismissed this as a rather extreme view, the question is still asked as to how much influence a language really has over a speaker’s thought process. Included below are some of the studies surrounding this:

Is the difference linguistic, or cultural?

In a 2002 study, native Spanish and German speakers with an understanding of English were asked to describe random objects using English adjectives. The researchers chose objects with one assigned grammatical gender in Spanish and with the opposite gender in German. The participants clearly chose adjectives more stereotypically associated with the assigned grammatical gender. For example, the Spanish word for “bridge” is masculine: el puente, but the German word is feminine: die Brücke. The Spanish speakers described bridges with commonly masculine words such as “big” and “strong”. Meanwhile, the German speakers chose to describe bridges with typically feminine words like “beautiful” and “elegant”. Surely this suggests the nature of their spoken language affects how they perceive things?

However, can this difference truly be down to the grammatical gender in the participants’ native tongue? Perhaps it could actually be a cultural difference? Is it possible German bridges are built differently than Spanish bridges, resulting in these description differences? Opposers to determinism could say that maybe the gendered prefix is the result of a difference in cultural perception, and not its cause. It seems this could potentially undermine Sapir and Whorf’s entire theory…

In an attempt to rule out the cultural influence, the same researchers carried out a second study. This time, they taught native English speakers about a fictitious language called Gumbuzi, replete with its own list of feminine and masculine nouns. The researchers then showed participants objects like bridges and tables and chairs. They were looking to see whether participants began to characterize these things with their newly devised genders. And it turns out, they did. The lack of cultural influence proves this experiment is useful in showing how gendered language can influence our thoughts.

If language reflects thought…

Linguistic reflectionism is the opposing view in this debate. It supposes that language simply reflects the opinions of its users, so the thoughts of a society will shape its language. From this perspective, we can describe language as simply the ‘dress of thought’. This theory often links with Universalism; the idea that we all share common ways of thinking, and the same thought can be expressed in a number of different ways.

Remember our ‘lost in translation’ argument from earlier? Well, whilst Pablo Neruda does believe creative meaning is lost between languages, he also willingly admits that literal meaning is all still there. “it says the same thing one has written”. This may seem too obvious, you might initially come to regard it as inconsequential. However, from a linguistic point of view, these two forms of meaning are indeed significant, especially when arguing from a reflectionist standpoint. Universalists believe any thoughts we have are expressible in any language, and are translatable to others too. Therefore, according to reflectionism, any individuals who think their writing is untranslatable simply have too much attachment to their words.

Pinker’s Instinct

Stephen Pinker’s ‘The Language Instinct’ is one of the most infamous modern linguistic texts, and a great starting point for anyone wanting to learn more about the subject. In his book, Pinker attempts to divide the world of language into the right and the wrong, and has his fair share to say on our determinism debate. He writes about determinism: “It is wrong. It is all wrong.” and that those believing in the wackier versions of this idea apparently have minds so open, their brains fall out.

So Pinker is clearly against determinism, but what are his reasons for this? He begins by pointing out that many of Sapir and Whorf’s earlier studies were flawed. For example, Whorf conducted various analyses of the languages used by tribes, but never did he actually visit these tribes himself. Therefore, Pinker believes Wharf’s knowledge of the languages and communication in question is extremely limited.

Eskimos in the Snow

Next, Pinker draws on some of the specific research Wharf conducted. One study which many determinism supporters found particularly gripping was on the language of Eskimos. Findings tell us that whilst English has only one word for ‘snow’, Eskimos have numerous. According to Wharf, this difference in language reflects the Eskimos’ acute experience with the wintry landscape. It is said that because these native peoples have a greater number of words for snow than exist in the English language, they must think more sophisticatedly about it.

However, Pinker points out the flaw in Whorf’s logic; Whorf may explain the Eskimos’ sophisticated mental concepts of snow with the number of words they have for it, but he fails to provide any evidence for any sophisticated mental phenomena proving language correlates to thought. So it seems Whorf simply expects us to take his word for it, with no cognitive proof to back him up.

Can language affect the timeline?

Another of Whorf’s well-known studies is on the Hopi people of Arizona. He observed that they had no grammatical distinctions for future and past and no way to count periods of time. Therefore, he concluded that the Hopi people could not conceive of time as a linear flow of the past, present and future in the same way we would in English. For example, ‘Tomorrow is another day’ would have no meaning for them. However, not only was Pinker correct in his claims that Whorf’s lack of communication with the tribe affects his judgement, he also questioned how Whorf could be so sure they didn’t mentally conceive of time. Again, there was no cognitive evidence. Whorf’s claims seemed to be somewhat… empty.

That was up until 1983, when a researcher named Ekkehart Malotki published Hopi Time, a volume detailing his research on the Hopi and their language. Throughout his works, Malotki proceeds to incinerate Whorf’s ideas of the Hopi’s lack of timeline, proving they were actually able to measure time. Therefore, Whorf’s ideas of language constraining thought were, in this case at least, merely false speculation.

Rethinking Relativity

After Malotki had completely disproved Whorf’s evidence for determinism, people began to mistrust linguistic relativity too. However, we haven’t yet looked into the arguments for relativity, some of which are much more recent and therefore have stronger evidence to support them.

Rewinding back to Whorf’s earlier realization of how people treated gasoline drums less cautiously when they were labeled ’empty’, it’s fair to admit his idea wasn’t completely wrong. Describing words can definitely have an effect on how people perceive things. Marketing and sales are an excellent example of this. Let’s imagine you want to sell some old clothes. You now have a choice. You could either market it as either ‘used’, or ‘vintage’. Certainly, people will be willing to pay more for ‘vintage clothes’ than just ‘used clothes’, despite them being the same thing. This shows how language affects the way we think and interpret. The same ritual can be applied to any product, whether it’s describing groceries, cars, or holidays, hence why an essential part of any business is its marketing team, who carefully select the correct language to appeal to their target audience.

Language and sense of direction

Could you accurately point to the north from where you’re sitting right now? Could any human reliably point to the north? As it turns out, some can. Whilst English speakers only talk about directions using left and right, Kuuk Thaayorre speakers use a very different method: the cardinal compass directions. They speak of north, south, east and west when giving directions. This seems quite disorientating to you and me, but not to the Kuuk Thaayorre. In fact, their language for direction means they must be aware of their orientation at all times, just to hold a conversation. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Psycholinguistics have proved that speakers of Kuuk Thaayorre are extremely good at keeping track of where they are in foreign places – even better than the locals.

And, unlike Whorf, these researchers have legitimate empirical data for both the psychological half of the claim and the linguistic half. This may seem like incredibly strong evidence for linguistic relativity; surely such a difference, which seemingly boils down to language, proves that their words are affecting their way of thinking. However, disputes remain: how can we be absolutely sure that it’s their language that causes the psychological phenomena? Perhaps there’s a third factor determining both language and thought: culture – but how can we measure where one ends and the other begins?

Political Correctness

It was actually Sapir-Whorf’s determinism theory which spurred the introduction of Political Correctness (PC) into the USA in the 1970s. PC refers to the belief that we shouldn’t use language that discriminates against any minority group, such as sexist, racist or ableist terms. It was based on the idea that if language controls thought, removing the discriminatory language would remove people’s discriminatory thoughts. There’s no denying the movement has been somewhat influential; of course, the language changes which have occurred reflect changes in attitudes to more than just the language. Words which were once acceptable to hear on TV in the 70s, such as ‘coon’ or ‘nigger’, probably now horrify you to read even in this context, showing that your thoughts on racism as a topic have changed, rather than only your language.

On the other hand, supporters of reflectionism dismiss this PC process. They believe that even if we change the language we use, discriminatory thoughts will always prevail. Instead, we must focus on changing society’s attitudes first, and then language change will follow. Applying this to the example above, Reflectionists would claim that although these terms are no longer used on TV, that’s not to say racist attitudes have gone away. Racist language reflects racist thoughts, so it will re-emerge through other terms in the future, unless we address people’s way of thinking.

A Euphemism Treadmill

This idea of re-emerging thoughts and language is supported by the Euphemism Treadmill; a theory posed by Stephen Pinker to support linguistic reflectionism. The concept explains how words that are used to replace offensive terms over time become offensive themselves.

When running on a treadmill, you reenact the movement of running forwards, when in reality you’re staying in one spot. Similarly, replacing discriminatory words with new ones may feel like society is moving forward, when actually our attitudes aren’t progressing at all. We end up stuck in a cycle, like the track of a treadmill going round and round.

One good example of a euphemism treadmill in action is the changes of ableist language. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, ‘idiot’ and ‘imbecile’ were both medical terms to describe patients with intellectual disabilities. However, once these became labeled as derogatory, the word ‘retarded’ was introduced as a ‘kinder’ alternative. But ‘retard’ has since become just as offensive, and was once again replaced with words like ‘special needs’. As you can see, the cycle has continued, and will continue; supposedly, until we change our attitudes towards the subject.

Language is not enough!

Reflectionism arguments against political correctness have often been criticized for dismissing the value of trying to shape or change language. Surely it’s better to attempt to prevent racist, ableist, or sexist language than to do nothing about it at all?

Some more modern examples where the PC language seems to be making a difference is in the area of sexism. Policemen are now police officers, the chairman is now a chairperson, and when we’re unsure of someone’s gender, we refer to ‘them’ rather than ‘him’. However, Norman Fairclough, who supports reflectionism, argued that changing language isn’t enough, we must also change society. For example, he says, there’s no point arguing about the word chairman being sexist, if you’re missing the point that women are underrepresented on the committee. Linguist Deborah Cameron agrees with this and calls non-sexist language policies “lip service” & “cosmetic change” because they fail to alone reduce women’s oppression. So maybe a change in language is simply disguising society’s discriminatory thoughts, not changing them.

Cultural Significance in Linguistic Anthropology

I’ve given you a few examples of how language can shape the way we think, and it does so in a variety of ways. Language can have big effects, like the Kuuk Thaayorre people’s ability to know their cardinal directions because of the language they use for direction.

Language can also have really deep effects – that’s what we saw with the euphemism treadmill. It shows us how we can attempt to control discrimination in society using language. Of course, it’s not only down to language, but also society’s ways of thinking which contribute to this issue. This one argument has acted as a stepping stone to the whole debate about how we can reduce inequality in society.

Language can also have behavioral effects. What we saw in the case of the empty gasoline drums was that describing words can influence how people act. The same goes for the language chosen for advertising. All the time, we are targeted through different forms of media, and each advert is crafted with language to tempt us into buying. These may seem like tiny, insignificant uses of language, but they can really impact how we behave and make decisions on a daily basis.

Language can have really broad effects. The case of grammatical gender might seem a little silly, but at the same time, grammatical gender applies to all nouns. That means language can shape how you’re thinking about anything that can be named by a noun. And that’s a lot of stuff.

Lastly, I’ve given you an example of how languages can shape things that have personal weight for those who write. Works like poetry, which are written with the cultural meaning of the words in their original language, can seem untranslatable according to the poet.

Final thoughts

The relationship between language and thoughts is unbelievably complex. With culture weighing in as another factor, it’s not always simple to draw the line where one ends and the next begins. The beauty of linguistic diversity is that it reveals to us just how ingenious and flexible the human mind is. Human minds have invented not one cognitive universe, but 7,000 – each with their own relationships to language and thoughts.

But where does this leave us with the Reflectionism/Determinism debate? As of now, the jury is still out. As new research comes in, so do objections to existing findings. That said, scientists are finding cleverer ways of looking for a clear link between language and thought. So, for this curious little pocket of human nature, one day we’ll hopefully get the answers we’re looking for.

Learning Objectives

- Explain the relationship between language and thinking

What Do You Think?: The Meaning of Language

Think about what you know of other languages; perhaps you even speak multiple languages. Imagine for a moment that your closest friend fluently speaks more than one language. Do you think that friend thinks differently, depending on which language is being spoken? You may know a few words that are not translatable from their original language into English. For example, the Portuguese word saudade originated during the 15th century, when Portuguese sailors left home to explore the seas and travel to Africa or Asia. Those left behind described the emptiness and fondness they felt as saudade (Figure 1). The word came to express many meanings, including loss, nostalgia, yearning, warm memories, and hope. There is no single word in English that includes all of those emotions in a single description. Do words such as saudade indicate that different languages produce different patterns of thought in people? What do you think??

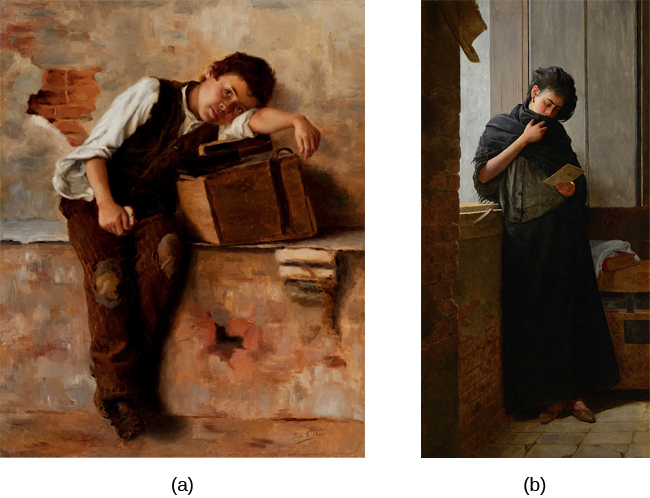

Figure 1. These two works of art depict saudade. (a) Saudade de Nápoles, which is translated into “missing Naples,” was painted by Bertha Worms in 1895. (b) Almeida Júnior painted Saudade in 1899.

Language may indeed influence the way that we think, an idea known as linguistic determinism. One recent demonstration of this phenomenon involved differences in the way that English and Mandarin Chinese speakers talk and think about time. English speakers tend to talk about time using terms that describe changes along a horizontal dimension, for example, saying something like “I’m running behind schedule” or “Don’t get ahead of yourself.” While Mandarin Chinese speakers also describe time in horizontal terms, it is not uncommon to also use terms associated with a vertical arrangement. For example, the past might be described as being “up” and the future as being “down.” It turns out that these differences in language translate into differences in performance on cognitive tests designed to measure how quickly an individual can recognize temporal relationships. Specifically, when given a series of tasks with vertical priming, Mandarin Chinese speakers were faster at recognizing temporal relationships between months. Indeed, Boroditsky (2001) sees these results as suggesting that “habits in language encourage habits in thought” (p. 12).

Language does not completely determine our thoughts—our thoughts are far too flexible for that—but habitual uses of language can influence our habit of thought and action. For instance, some linguistic practice seems to be associated even with cultural values and social institution. Pronoun drop is the case in point. Pronouns such as “I” and “you” are used to represent the speaker and listener of a speech in English. In an English sentence, these pronouns cannot be dropped if they are used as the subject of a sentence. So, for instance, “I went to the movie last night” is fine, but “Went to the movie last night” is not in standard English. However, in other languages such as Japanese, pronouns can be, and in fact often are, dropped from sentences. It turned out that people living in those countries where pronoun drop languages are spoken tend to have more collectivistic values (e.g., employees having greater loyalty toward their employers) than those who use non–pronoun drop languages such as English (Kashima & Kashima, 1998). It was argued that the explicit reference to “you” and “I” may remind speakers the distinction between the self and other, and the differentiation between individuals. Such a linguistic practice may act as a constant reminder of the cultural value, which, in turn, may encourage people to perform the linguistic practice.

One group of researchers who wanted to investigate how language influences thought compared how English speakers and the Dani people of Papua New Guinea think and speak about color. The Dani have two words for color: one word for light and one word for dark. In contrast, the English language has 11 color words. Researchers hypothesized that the number of color terms could limit the ways that the Dani people conceptualized color. However, the Dani were able to distinguish colors with the same ability as English speakers, despite having fewer words at their disposal (Berlin & Kay, 1969). A recent review of research aimed at determining how language might affect something like color perception suggests that language can influence perceptual phenomena, especially in the left hemisphere of the brain. You may recall from earlier chapters that the left hemisphere is associated with language for most people. However, the right (less linguistic hemisphere) of the brain is less affected by linguistic influences on perception (Regier & Kay, 2009)

Link to Learning

Learn more about language, language acquisition, and especially the connection between language and thought in the following CrashCourse video:

You can view the transcript for “Language: Crash Course Psychology #16” here (opens in new window).

Try It

Glossary

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis: the hypothesis that the language that people use determines their thoughts

Contribute!

Did you have an idea for improving this content? We’d love your input.

Improve this pageLearn More

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Thought and language» redirects here. For the book, see Lev Vygotsky.

The study of how language influences thought has a long history in a variety of fields. There are two bodies of thought forming around this debate. One body of thought stems from linguistics and is known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. There is a strong and a weak version of the hypothesis which argue for more or less influence of language on thought. The strong version, linguistic determinism, argues that without language there is and can be no thought while the weak version, linguistic relativity, supports the idea that there are some influences from language on thought.[1] And on the opposing side, there are ‘language of thought’ theories (LOTH) which believe that public language is inessential to private thought (though the possibility remains that private thought when infused with inessential language diverges in predilection, emphasis, tone, or subsequent recollection). LOTH theories address the debate of whether thought is possible without language which is related to the question of whether language evolved for thought. These ideas are difficult to study because it proves challenging to parse the effects of culture versus thought versus language in all academic fields.

The main use of language is to transfer thoughts from one mind, to another mind. The bits of linguistic information that enter into one person’s mind, from another, cause people to entertain a new thought with profound effects on his world knowledge, inferencing, and subsequent behavior. Language neither creates nor distorts conceptual life.[dubious – discuss][citation needed] Thought comes first, while language is an expression. There are certain limitations among language, and humans cannot express all that they think.[2]

Language of thought[edit]

Language of thought theories rely on the belief that mental representation has linguistic structure. Thoughts are «sentences in the head», meaning they take place within a mental language. Two theories work in support of the language of thought theory. Causal syntactic theory of mental practices hypothesizes that mental processes are causal processes defined over the syntax of mental representations. Representational theory of mind hypothesizes that propositional attitudes are relations between subjects and mental representations. In tandem, these theories explain how the brain can produce rational thought and behavior. All three of these theories were inspired by the development of modern logical inference. They were also inspired by Alan Turing’s work on causal processes that require formal procedures within physical machines.[3]

LOTH hinges on the belief that the mind works like a computer, always in computational processes. The theory believes that mental representation has both a combinatorial syntax and compositional semantics. The claim is that mental representations possess combinatorial syntax and compositional semantic—that is, mental representations are sentences in a mental language. Alan Turing’s work on physical machines implementation of causal processes that require formal procedures was modeled after these beliefs.[3]

Another prominent linguist, Steven Pinker, developed this idea of a mental language in his book The Language Instinct (1994). Pinker refers to this mental language as mentalese. In the glossary of his book, Pinker defines mentalese as a hypothetical language used specifically for thought. This hypothetical language houses mental representations of concepts such as the meaning of words and sentences.[4]

Scientific hypotheses[edit]

- The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis in linguistics states that the grammatical structure of a mother language influences the way we perceive the world. The hypothesis has been largely abandoned by linguists as it has found very limited experimental support, at least in its strong form, linguistic determinism. For instance, a study showing that speakers of languages lacking a subjunctive mood such as Chinese experience difficulty with hypothetical problems has been discredited. Another study did show that subjects in memory tests are more likely to remember a given color if their mother language includes a word for that color; however, these findings do not necessarily support this hypothesis specifically. Other studies concerning the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis can be found in the «studies» section below.

- Chomsky’s independent theory, founded by Noam Chomsky, considers language as one aspect of cognition. Chomsky’s theory states that a number of cognitive systems exist, which seem to possess distinct specific properties. These cognitive systems lay the groundwork for cognitive capacities, like language faculty.[3]

- Piaget’s cognitive determinism exhibits the belief that infants integrate experience into progressively higher-level representations. He calls this belief constructivism, which supports that infants progress from simple to sophisticated models of the world through a change mechanism that allows an infant to build on their lower-level representations to create higher-level ones. This view opposes nativist theories about cognition being composed of innate knowledge and abilities.

- Vygotsky’s theory on cognitive development, known as Vygotsky’s theory of interchanging roles, supports the idea that social and individual development stems from the processes of dialectical interaction and function unification. Lev Vygotsky believed that before two years of age, both speech and thought develop in differing ways along with differing functions. The idea that relationship between thought and speech is ever-changing, supports Vygotsky’s claims. Vygotsky’s theory claims that thought and speech have different roots. And at the age of two, a child’s thought and speech collide, and the relationship between thought and speech shifts. Thought then becomes verbal and speech then becomes rational.[3]

- According to the theory behind cognitive therapy, founded by Aaron T. Beck, our emotions and behavior are caused by our internal dialogue. We can change ourselves by learning to challenge and refute our own thoughts, especially a number of specific mistaken thought patterns called «cognitive distortions». Cognitive therapy has been found to be effective by empirical studies.

- In behavioral economics, according to experiments said to support the theoretical availability heuristic, people believe events that are more vividly described are more probable than those that are not. Simple experiments that asked people to imagine something led them to believe it to be more likely. The mere exposure effect may also be relevant to propagandistic repetition like the Big Lie. According to prospect theory, people make different economic choices based on how the matter is framed.

Studies concerning the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis[edit]

Counting[edit]

Different cultures use numbers in different ways. The Munduruku culture for example, has number words only up to five. In addition, they refer to the number 5 as «a hand» and the number 10 as «two hands». Numbers above 10 are usually referred to as «many».

Perhaps the most different counting system from that of modern Western civilisation is the «one-two-many» system used by the Pirahã people. In this system, quantities larger than two are referred to simply as «many». In larger quantities, «one» can also mean a small amount and «many» a larger amount. Research was conducted in the Pirahã culture using various matching tasks. These are non-linguistic tasks that were analyzed to see if their counting system or more importantly their language affected their cognitive abilities. The results showed that they perform quite differently from, for example, an English speaking person who has a language with words for numbers more than two. For example, they were able to represent numbers 1 and 2 accurately using their fingers but as the quantities grew larger (up to 10), their accuracy diminished. This phenomenon is also called the «analog estimation», as numbers get bigger the estimation grows.[5] Their declined performance is an example of how a language can affect thought and great evidence to support the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.

Orientation[edit]

Language also seems to shape how people from different cultures orient themselves in space. For instance, many Australian Aboriginal Nations, such as the Kuuk Thaayorre, exclusively use cardinal-direction terms – north, south, east and west — and never define space relative to the observer. Instead of using terms like «left,» «right,» «back» and «forward,» speakers from such cultures would say, «There is a spider on your northeast leg,» or «Pass the ball to the south southwest.» In fact, instead of «hello,» the greeting in such cultures is, «Where are you going?» and sometimes even «Where are you coming from?» Such a greeting would be followed by a directional answer: «To the northeast in the middle distance.» The consequence of using such language is that the speakers need to be constantly oriented in space, otherwise they would not be able to express themselves properly, or even get past a greeting. Speakers of languages that rely on absolute reference frames have a greater navigational ability and spatial knowledge compared to speakers of languages that use relative reference frames. In comparison with English users, speakers of languages such as Kuuk Thaayorre are also much better at staying oriented even in unfamiliar spaces, and there is strong evidence that their language is what enables them to do this.[6]

Color[edit]

Language may influence color processing. Having more names for different colors, or different shades of colors, makes it easier both for children and for adults to recognize them.[7] Research has found that all languages have names for black and white and that the colors defined by each language follow a certain pattern (i.e. a language with three colors also defines red, one with four defines green OR yellow, one with six defines blue, then brown, then other colors).[8]

Other schools of thought[edit]

- General semantics is a school of thought founded by engineer Alfred Korzybski in the 1930s and later popularized by S.I. Hayakawa and others, which attempted to make language more precise and objective. It makes many basic observations of the English language, particularly pointing out problems of abstraction and definition. General semantics is presented as both a theoretical and a practical system whose adoption can reliably alter human behavior in the direction of greater sanity. It is considered to be a branch of natural science and includes methods for the stimulation of the activities of the human cerebral cortex, which is generally judged by experimentation. In this theory, semantics refers to the total response to events and actions, not just the words. The neurological, emotional, cognitive, semantic, and behavioral reactions to events determines the semantic response of a situation. This reaction can be referred to as semantic response, evaluative response, or total response.[9]

- E-prime is a constructed language identical to the English language but lacking all forms of «to be». Its proponents claim that dogmatic thinking seems to rely on «to be» language constructs, and so by removing it we may discourage dogmatism.

- Neuro-linguistic programming, founded by Richard Bandler and John Grinder, claims that language «patterns» and other things can affect thought and behavior. It takes ideas from General Semantics and hypnosis, especially that of the famous therapist Milton Erickson. Many do not consider it a credible study, and it has no empirical scientific support.

- Advocates of non-sexist language including some feminists say that the English language perpetuates biases against women, such as using male-gendered terms such as «he» and «man» as generic. Many authors including those who write textbooks now conspicuously avoid that practice, in the case of the previous examples using words like «he or she» or «they» and «human race».

- Various other schools of persuasion directly suggest using language in certain ways to change the minds of others, including oratory, advertising, debate, sales, and rhetoric. The ancient sophists discussed and listed many figures of speech such as enthymeme and euphemism. The modern public relations term for adding persuasive elements to the interpretation of and commentary on news is called spin.

Popular culture[edit]

The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is the premise of the 2016 science fiction film Arrival. The protagonist explains that «the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is the theory that the language you speak determines how you think».[10]

See also[edit]

- Embodied cognition

- Image schema

- Inner voice

- Kant and the Platypus: Essays on Language and Cognition by Umberto Eco

- Lev Vygotsky

- Origin of language

- Philosophy of language

References[edit]

- ^ Kaplan, Abby (2016). Women Talk More than Men: … And Other Myths about Language Explained. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316027141.011. ISBN 978-1-316-02714-1.

- ^ Gleitman, Lila (2005). «Language and thought» (PDF). Cambridge Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning.

- ^ a b c d Birjandi, Parvis. «A Review of the Language-Thought Debate: Multivariant Perspectives». Islamic Azad University (Science and Research Branch) – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Pinker (2007). The Language Instinct (1994/2007). New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

- ^ Gordon, P., (2004). Numerical Cognition Without Words: Evidence from Amazonia. Science. 306, pp.496-499.

- ^ Boroditsky, L. (2009, June 12). How Does Our Language Shape the Way We Think? . Edge.org. Retrieved March 18, 2013, from http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/boroditsky09/boroditsky09_index.html.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L. (2011). Psychology Second Edition. New York: Worth Publishers. pp. 360–362. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ Berlin, Brent; Kay, Paul (1969). Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Ward, K. (2012). General Semantics. Retrieved March 31, 2013, from http://www.trans4mind.com/personal_development/KenGenSemantics.htm.

- ^ «The science behind the movie ‘Arrival’«. Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-04-23.