Asked

6 years, 3 months ago

Viewed

62k times

I have been in quiet spaces and heard the wind coming long before it gets to where I am. It is almost like a presence that is there at the edge of perception.

asked Dec 30, 2016 at 4:23

2

Psithurism

The sound of wind in the trees and rustling of leaves.

(The Free Dictionary)

answered Dec 30, 2016 at 5:09

Elliott FrischElliott Frisch

6,7541 gold badge23 silver badges39 bronze badges

Howl verb

If the wind howls, it blows with a long loud sound

Sigh verb

If the wind sighs, it makes a long soft low sound

Sough verb

If the wind soughs, it makes a soft noise like a sigh

Macmillan

Glorfindel

14.4k15 gold badges66 silver badges58 bronze badges

answered Dec 30, 2016 at 4:32

freeling10freeling10

1,5169 silver badges12 bronze badges

Add your answer:

Earn +

20

pts

Q: What is it called when a word sounds like the sound it makes?

Write your answer…

Made with 💙 in St. Louis

Copyright ©2023 Infospace Holdings LLC, A System1 Company. All Rights Reserved. The material on this site can not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with prior written permission of Answers.

Would you like this sound words list as a free PDF poster with pictures? Click here to get it.

We hear different sounds all the time. But how do we actually say them as words?

There are many different words for sounds. Let’s look at 42 sound words in English (plus some useful idioms with sound words).

Remember English Prepositions Forever!

Download free!

1. Sounds of things hitting things

Thud

The sound of something heavy falling and hitting the ground.

I don’t know why she’s dropping a brick from a high chair.

But it does make a fun sound.

Whack

The sound of a short, heavy hit.

This can also be used as a verb:

“She whacked him in the head with the pillow.”

Slap

The sound of someone hitting something (or someone) with an open hand.

You’ll hear this word a lot in idioms:

A slap in the face is used when someone has done something bad to you (given you something you don’t want or not given you something that you do want, for example), usually unfairly.

“I did all of the work for the project and then Sam gets the promotion — not fair. What a slap in the face!”

A slap on the wrist is when someone gets punished — but very, very lightly. Much less than they deserve:

“You heard about Hexon Oil? They polluted every lake in the country and only got a $2000 fine. It was barely a slap on the wrist, really.”

A slap-up meal is basically a massive meal — the kind of meal you have when you really don’t want to think about your weight or your health. Just enjoy it!

“I’ve sold the house! I’m taking you all out for a slap-up meal at Mrs Miggins’ pie shop!”

A slapdash job or slapdash work is work done really badly. I remember waiting in a cafe at Sofia airport, and these Austrian guys found it quite funny that there was just one plug socket in the whole cafe. And it was halfway up the wall. The designer definitely did a slapdash job:

“Don’t get that builder. He did such a slapdash job on our house that the roof fell in.”

Knock

OK, so “knock” is the sound that you make when you arrive at your friend’s house and hit their door with your hand.

There’s also the phrase “don’t knock it.”

It basically means “don’t criticise it.”

“Banana and crisp sandwiches are actually really good! Don’t knock it till you’ve tried it!”

Rattle

Stay away! It’s a rattlesnake. And it’s rattling its tail.

As a verb, “rattle” can also mean “disturb.”

Think about classic action heroes.

They can fall out of planes, jump off the edges of mountains, survive car crashes, helicopter crashes and bike crashes; they can be forced to swim underwater for five minutes and then run 200 metres over burning coals.

And after that, they’re just fine, right?

That’s because nothing rattles them. Nothing!

Splat

The sound of something wet hitting something else.

Like when you throw eggs or rotten tomatoes at the visiting politician.

Or a water balloon at your friend.

Clunk

This is one of those words that sounds like it sounds, if you know what I mean.

It’s a heavy, dull sound.

Clang

A noisy, metallic sound.

Clink

This is like clang’s baby brother.

It’s a small, sharp sound — usually made when metal or glass touches something.

Patter

A light tapping sound.

We usually use it to describe rain:

“I love sleeping through storms, don’t you! The patter of rain on the roof and knowing you’re safe and sound in bed.”

When I was a kid (and for too long afterwards — she still does this when I visit) my mother would greet me when I came downstairs in the morning with:

“You’re awake! I thought I heard the patter of tiny feet!”

“Mum — I’m 37 years old.”

Clatter

Clang is noisy and unpleasant, right?

Now imagine lots of clangs. That’s clatter.

Smash

The sound of something breaking into a million pieces. Usually violently.

“Smashing” can also mean “excellent”:

“She did such a smashing job that we hired her full time.”

Slam

We usually use this to describe closing a door very loudly.

But we can use it for other similar situations.

You can slam the phone down (if you’re using a non-mobile phone, like the retro kid you are).

You can also slam a glass on the table. (Think tequila shots.)

If someone slams the door in your face, they basically decide not to help you or give you information that you need.

“I called the helpline about it, but they refused to help. Completely slammed the door in my face.”

You can also just “slam” something. It means “give a very, very negative review.”

“The New York Times completely slammed his new book. But I thought it was pretty good.”

2. Mechanical sounds

Honk

When I lived in Istanbul, I would play a game.

I would try to count to five without hearing a single car honk its horn.

I never got past three seconds.

Also — it was a terrible game. But I was bored.

Whir

A continuous sound — usually quiet, often calming.

Tick

We almost always think of clocks and watches when we hear the word “tick.”

It’s that tiny, short sound.

So it wouldn’t surprise you to hear that we can use the phrase “time is ticking” to mean “hurry up!”

“Let’s get started! Time’s ticking.”

If you’re a bit angry (not furious — just a bit), then you can say that you’re “ticked off.”

“To be honest, I’m a bit ticked off. I didn’t expect you to tell everyone about what I told you. It was private.”

“In a tick” can also mean “in a minute,” “in a second,” “in a moment” or just “soon.”

“Take a seat. I’ll be with you in a tick.”

Click

A small, sharp sound.

Think about a light switch.

Or this annoying guy and his annoying pen.

When you click with someone, you immediately get on well. You start talking and it feels as if you’ve always been friends.

“I’ve been friends with Gudrun for 20 years. We clicked as soon as we met.”

Bang

A loud noise! Usually sudden.

This is most closely associated with guns. But the building site next to my house also produces a lot of bangs.

If you go out with a bang, you finish or leave something in a super-dramatic way.

“Wow! His last day of work and he throws coffee in the boss’s face! Talk about going out with a bang!”

When someone bangs on about something, they talk for ages about it while successfully boring the life out of whoever has the bad luck to listen to them.

“If you could just stop banging on about your new computer for a minute, I’d like to talk to you about what happened last weekend.”

Buzz

The sound of something vibrating.

When we talk about the buzz of a place, we’re talking about that special energy it has.

Some cities (like Vienna) have a real buzz, while some cities (like Swindon) don’t.

“What I miss about Istanbul most is the buzz. And the food. But mostly the buzz.”

You can also buzz someone in when you’re at home, and someone wants to get into the building. It saves you from having to walk all the way downstairs to let them in.

“Hey! I’m outside your flat now. Can you buzz me in?”

Finally, you can give someone a buzz. It just means “give them a quick call.”

“Let’s have that drink on Friday. Just give me a buzz, and I’ll let you know where I am.”

3. Electronic sounds

Ping

This is the sound of a very small bell.

Think of a typewriter or a hotel reception desk.

Blip

A ping will last for a long time (piiiinnnggggg). But a blip is very, very short.

Think of a radar in those films with too many submarines in.

Beep

A blip sounds quite nice, but a beep can get very annoying very quickly.

I don’t know how people working as supermarket cashiers don’t go crazy. Do they still hear the beeps when they go to sleep at night?

4. Organic sounds

Snap

A sudden breaking sound — think of the sound of wood breaking.

I guess because it’s quite an unpredictable sound, we can also use “snap” as a verb to mean “suddenly get angry.” When you snap, it’s probably a result of lots of things building up.

“It was when her kid put his school tie in the toaster that she finally snapped.”

It also has a second meaning.

Have you ever tried to talk to someone, and instead of saying “Hi!” or “Good to see you!” or “Nice hair,” they just angrily shout at you — completely unpredictable and sudden?

Then they snapped at you.

“I wouldn’t talk to him right now, if I were you. I just asked him if he was OK, and he snapped at me.”

You can also just say “snap” when someone else has something that you have. It could be a plan, an interest, or something physical, like a T-shirt.

“No way! Snap! I’ve got the exact same phone.”

Finally, there’s a snap election.

It’s a general election that the prime minister or president suddenly announces — usually because they think they’ll win. All of a sudden, we’re voting. Again!

“She said she wouldn’t call a snap election. Then she did.”

Crack

It’s like a loud snap.

If you want to celebrate, you can do so in style — by cracking open a bottle of champagne:

“You got the job?! Awesome — let’s crack open a bottle, yeah?”

If you drink too much of it, you might find EVERYTHING funny and just crack up all the time. It means suddenly start laughing. A lot. Until your face hurts.

“I told him my idea, and he just cracked up. I didn’t think it was that funny.”

Crackle

Lots of small cracks.

Fire and fireworks crackle. And not much else.

Pop

A tiny, little, mini explosion sound.

Because it’s such a short sound, we use it in phrasal verbs to describe something quick.

You can pop out (go outside — but only for a bit):

“I’m just popping out for some fresh air. See you in a few minutes.”

Or you can pop in somewhere (visit — but only for a bit):

“When you’re in town, why not pop in for a coffee?”

Sizzle

The sound of food cooking.

Rustle

There are basically only two things that rustle.

Leaves (especially dry, autumn leaves) and paper.

To rustle something up means to make a quick meal — like a sandwich or some toast.

“You haven’t eaten? Give me two minutes — I’ll rustle something up.”

Rumble

A continuous, deep sound.

Think of thunder.

Or your stomach when you’re really hungry.

5. Water sounds

Fizz

That nice sound of bubbles popping. Think about sparkling water or champagne.

Squelch

You just need to say this word to understand what it means.

Go on, say it. Feels good, doesn’t it?

It’s basically the sound of walking in mud.

Gurgle

This is the sound of bubbles being created.

Imagine lying down in the green grass next to a beautiful stream.

What can you hear?

The gurgle of the stream of course.

And the lion. Look out for the lion.

Glug

If gurgle is a series of sounds, then glug is a single one of those sounds.

Think of how you sound when you’re drinking water quickly.

Drip

“Drip” looks like “drop,” right?

Well, “drip” is the sound that a drop makes when it hits something.

Splash

The sound of something hitting water (or any liquid).

Think of the sound of kids in the bath.

Or the sound at the end of a water slide.

If you feel like spending a little more money than you should, then you splash out.

“Yeah, it’s a bit pricey. But it’s my birthday. I’m gonna splash out.”

Trickle

This is the sound of liquid flowing very slowly.

Squeal

Don’t step on the rat’s tail. He’ll squeal really loudly.

Also, it’s not nice. Leave the rat alone, you monster.

Squeak

A squeak is a small, high-pitched sound.

Think of the sound of a mouse.

Or an old bed.

Or a door that needs oil.

I once had a pair of shoes that squeaked a lot.

You can also use the phrase “a squeak out of someone” to describe any sound coming out of their mouth at all. It’s usually used in the negative.

“Right. He’s coming. I don’t want to hear a squeak out of either of you until he’s gone. I’ll do the talking.”

Hiss

OK. Repeat after me:

“Ssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss.”

Good — you’ve just made a hiss.

Swish

This is another word that sounds like it sounds. (These words are called onomatopoeia, by the way.)

It’s a bit like a mixture between a hiss and a rustle.

Creak

When you open that old, heavy wooden door.

Or decide to take your kids to a playground that was built in the ‘50s.

Then expect to hear a lot of loud, high-pitched sounds of wood and metal rubbing together.

A lot of creaks.

Scrape

The sound of something hard or sharp rubbing against something else.

We use this a lot as a verb.

You might have to scrape ice off your car on winter mornings.

Or scrape the pancake off the pan after you’ve burned it.

Or scrape chewing gum off the table. Seriously, why do people do that?

There’s also the idiom “to scrape the bottom of the barrel.”

We use it when we’ve almost completely run out of options, and all we have are the worst choices.

“Is this the best we can do? We’re really scraping the bottom of the barrel here. I mean some of them don’t even have faces.”

Congratulations! You now know 42 sound words in English (plus some new idioms).

So let’s practice:

- Have you splashed out on something recently (like a slap-up meal or clothes)?

- What ticks you off the most?

- Can you remember cracking up over something that wasn’t funny? What was it?

Answer in the comments!

Did you like this post? Then be awesome and share by clicking the blue button below.

Onomatopoeia

(sound-imitation,

echoism)

is the naming of an action or thing by a more or less exact

reproduction of a natural sound associated with it (babble,

crow, twitter).

Words coined by this

interesting type of word-building are made by imitating different

kinds of sounds that may be produced by animals, birds, insects,

human beings and inanimate objects.

It is of some interest that

sounds produced by the same kind of animal are frequently represented

by quite different sound groups in different languages. For instance,

English dogs bark

(cf.

the Rus.

лаять,

UA.

гавкати)

or howl

(cf. the

Rus. выть,

UA. вити).

The

English cock cries cock-a-doodle-doo

(cf. the

Rus. ку—ка—ре—ку,

UA.

ку-ка-рі-ку).

In England

ducks quack

and frogs

croak (cf.

the Rus. крякать

UA.

крякати

said about

ducks and Rus.

квакать,

UA.

квакати,

said about

frogs). It is only English and Russian/Ukrainian cats who seem

capable of mutual understanding when they meet, for English cats mew

or miaow

(meow). The

same can be said about cows: they moo

(but also

low).

Some names of animals and

especially of birds and insects are also produced by sound-imitation:

crow, cuckoo, humming-bird, whip-poor-will, cricket.

The following desperate letter contains a great number of

sound-imitation words reproducing sounds made by modern machinery:

The Baltimore &

Ohio R. R.

Co.,

Pittsburg, Pa.

Gentlemen:

Why is it that your switch engine has to ding and fizz and spit and

pant and grate and grind and puff and bump and chug and hoot and toot

and whistle and wheeze and howl and clang and growl and thump and

clash and boom and jolt and screech and snarl and snort and slam and

throb and soar and rattle and hiss and yell and smoke and shriek all

night long when I come home from a hard day at the boiler works and

have to keep the dog quiet and the baby quiet so my wife can squawk

at me for snoring in my sleep?

Yours

(From Language

and Humour by

G. G. Pocheptsov.)

The

great majority of motivated words in present-day language are

motivated by reference to other words in the language, to the

morphemes that go to compose them and to their arrangement.

Therefore, even if one hears the noun wage-earner

for

the first time, one understands it, knowing the meaning of the words

wage

and

earn

and

the structural pattern

noun

stem +

verbal

stem+

—er

as

in bread-winner,

skyscraper, strike-breaker.

Sound

imitating or onomatopoeic words are on the contrary motivated with

reference to extra-linguistic reality, they are echoes of

natural sounds (e. g. lullaby,

twang, whiz.) Sound

imitation

(onomatopoeia

or echoism)

is consequently the naming of an action or thing by a more or less

exact reproduction of a sound associated with it. For instance words

naming sounds and movement of water: babble,

blob, bubble, flush, gurgle, gush, splash, etc.

The

term onomatopoeia is from Greek onoma

‘name,

word’ and poiein

‘to

make →

‘the

making of words (in imitation of sounds)’.

It

would, however, be wrong to think that onomatopoeic words reflect the

real sounds directly, irrespective of the laws of the language,

because the same sounds are represented differently in different

languages.

Onomatopoeic words adopt the phonetic features of English

and fall into the combinations peculiar to it. This becomes obvious

when one compares onomatopoeic words crow

and

twitter

and

the words flow

and

glitter

with

which they are rhymed in the following poem:

The cock is crowing,

The stream is flowing.

The small birds twitter,

The lake does glitter,

The

green fields sleep in the sun (Wordsworth).

The

majority of onomatopoeic words used to name sounds or movements are

verbs easily turned into nouns: bang,

boom, bump, hum, rustle, smack, thud, etc.

They are very expressive and

sometimes it is difficult to tell a noun from an interjection.

Consider the following:

Thum

—

crash!

“Six

o’clock, Nurse,” —

crash!

as

the door shut again. Whoever it was had given me the shock of my life

(M. Dickens).

Sound-imitative

words form a considerable part of interjections:

bang!

hush! pooh!

Semantically,

according to the source of sound, onomatopoeic words fall into a few

very definite groups. Many verbs denote sounds produced by human

beings in the process of communication or in expressing their

feelings:

babble,

chatter, giggle, grunt, grumble, murmur, mutter, titter, whine,

whisper,

etc.

Then

there are sounds produced by animals, birds and insects:

buzz,

cackle, croak, crow, hiss, honk, howl, moo, mew, neigh, purr, roar

etc.

Some

birds are named after the sound they make, these are the

crow, the cuckoo, the whippoor-will and

a few others. Besides the verbs imitating the sound of water such as

bubble

or

splash,

there

are others imitating the noise of metallic things: clink,

tinkle, or

forceful motion: clash,

crash, whack, whip, whisk, etc.

The

combining possibilities of onomatopoeic words are limited by usage.

Thus, a contented cat purrs,

while

a similarly sounding verb whirr

is

used about wings. A gun bangs

and

a bow twangs.

R. Southey’s poem “How

Does the Water Come Down at Lodore” is a classical example of the

stylistic possibilities offered by onomatopoeia: the words in it

sound an echo of what the poet sees and describes.

Here it comes sparkling,

And

there it flies darkling …

Eddying and whisking,

Spouting

and frisking, …

And

whizzing and hissing, …

And

rattling and battling, …

And

guggling and struggling, …

And bubbling and troubling

and doubling,

And rushing and flushing

and brushing and gushing,

And

flapping and rapping and clapping and slapping …

And thumping and pumping

and bumping and jumping,

And

dashing and flashing and splashing and clashing …

And at once and all o’er,

with a mighty uproar,

And this way the water

comes down at Lodore.

Once

being coined, onomatopoeic words lend themselves easily to further

word-building and to semantic development. They readily develop

figurative meanings. Croak,

for

instance, means “to make a deep harsh sound”. In its direct

meaning the verb is used about frogs or ravens. Metaphorically it may

be used about a hoarse human voice. A further transfer makes the verb

synonymous to such expressions as “to protest dismally”, “to

grumble dourly”, “to predict evil”.

There is a hypothesis that

sound-imitation as a way of word-formation should be viewed as

something much wider than just the production of words by the

imitation of purely acoustic phenomena. Some scholars suggest that

words may imitate through their sound form certain unacoustic

features and qualities of inanimate objects, actions and processes or

that the meaning of the word can be regarded as the immediate

relation of the sound group to the object. If a young chicken or

kitten is described as fluffy

there

seems to be something in the sound of the adjective that conveys the

softness and the downy quality of its plumage or its fur. Such verbs

as to

glance, to glide, to slide, to slip are

supposed to convey by their very sound the nature of the smooth, easy

movement over a slippery surface. The sound form of the words

shimmer,

glimmer, glitter seems

to reproduce the wavering, tremulous nature of the faint light. The

sound of the verbs to

rush, to dash, to flash may

be said to reflect the brevity, swiftness and energetic nature of

their corresponding actions. The word thrill

has

something in the quality of its sound that very aptly conveys the

tremulous, tingling sensation it expresses.

Some scholars have given serious consideration to this theory.

However, it has not yet been properly developed.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

A sign in a shop window in Italy proclaims these silent clocks make «No Tic Tac» [sic], in imitation of the sound of a clock.

Onomatopoeia[note 1] is the use or creation of a word that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Such a word itself is also called an onomatopoeia. Common onomatopoeias include animal noises such as oink, meow (or miaow), roar, and chirp. Onomatopoeia can differ between languages: it conforms to some extent to the broader linguistic system;[6][7] hence the sound of a clock may be expressed as tick tock in English, tic tac in Spanish and Italian (shown in the picture), dī dā in Mandarin, kachi kachi in Japanese, or tik-tik in Hindi.

The English term comes from the Ancient Greek compound onomatopoeia, ‘name-making’, composed of onomato— ‘name’ and —poeia ‘making’. Thus, words that imitate sounds can be said to be onomatopoeic or onomatopoetic.[8]

Uses

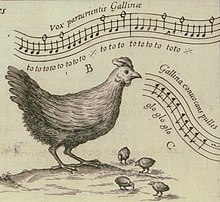

According to Musurgia Universalis (1650), the hen makes «to to too», while chicks make «glo glo glo».

In the case of a frog croaking, the spelling may vary because different frog species around the world make different sounds: Ancient Greek brekekekex koax koax (only in Aristophanes’ comic play The Frogs) probably for marsh frogs; English ribbit for species of frog found in North America; English verb croak for the common frog.[9]

Some other very common English-language examples are hiccup, zoom, bang, beep, moo, and splash. Machines and their sounds are also often described with onomatopoeia: honk or beep-beep for the horn of an automobile, and vroom or brum for the engine. In speaking of a mishap involving an audible arcing of electricity, the word zap is often used (and its use has been extended to describe non-auditory effects of interference).

Human sounds sometimes provide instances of onomatopoeia, as when mwah is used to represent a kiss.[10]

For animal sounds, words like quack (duck), moo (cow), bark or woof (dog), roar (lion), meow/miaow or purr (cat), cluck (chicken) and baa (sheep) are typically used in English (both as nouns and as verbs).

Some languages flexibly integrate onomatopoeic words into their structure. This may evolve into a new word, up to the point that the process is no longer recognized as onomatopoeia. One example is the English word bleat for sheep noise: in medieval times it was pronounced approximately as blairt (but without an R-component), or blet with the vowel drawled, which more closely resembles a sheep noise than the modern pronunciation.

An example of the opposite case is cuckoo, which, due to continuous familiarity with the bird noise down the centuries, has kept approximately the same pronunciation as in Anglo-Saxon times and its vowels have not changed as they have in the word furrow.

Verba dicendi (‘words of saying’) are a method of integrating onomatopoeic words and ideophones into grammar.

Sometimes, things are named from the sounds they make. In English, for example, there is the universal fastener which is named for the sound it makes: the zip (in the UK) or zipper (in the U.S.) Many birds are named after their calls, such as the bobwhite quail, the weero, the morepork, the killdeer, chickadees and jays, the cuckoo, the chiffchaff, the whooping crane, the whip-poor-will, and the kookaburra. In Tamil and Malayalam, the word for crow is kaakaa. This practice is especially common in certain languages such as Māori, and so in names of animals borrowed from these languages.

Cross-cultural differences

Although a particular sound is heard similarly by people of different cultures, it is often expressed through the use of different consonant strings in different languages. For example, the snip of a pair of scissors is cri-cri in Italian,[11] riqui-riqui in Spanish,[11] terre-terre[11] or treque-treque[citation needed] in Portuguese, krits-krits in modern Greek,[11] cëk-cëk in Albanian,[citation needed] and katr-katr in Hindi.[citation needed] Similarly, the «honk» of a car’s horn is ba-ba (Han: 叭叭) in Mandarin, tut-tut in French, pu-pu in Japanese, bbang-bbang in Korean, bært-bært in Norwegian, fom-fom in Portuguese and bim-bim in Vietnamese.[citation needed]

Onomatopoeic effect without onomatopoeic words

An onomatopoeic effect can also be produced in a phrase or word string with the help of alliteration and consonance alone, without using any onomatopoeic words. The most famous example is the phrase «furrow followed free» in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The words «followed» and «free» are not onomatopoeic in themselves, but in conjunction with «furrow» they reproduce the sound of ripples following in the wake of a speeding ship. Similarly, alliteration has been used in the line «as the surf surged up the sun swept shore …» to recreate the sound of breaking waves in the poem «I, She and the Sea».

Comics and advertising

A sound effect of breaking a door

Comic strips and comic books make extensive use of onomatopoeia. Popular culture historian Tim DeForest noted the impact of writer-artist Roy Crane (1901–1977), the creator of Captain Easy and Buz Sawyer:

- It was Crane who pioneered the use of onomatopoeic sound effects in comics, adding «bam,» «pow» and «wham» to what had previously been an almost entirely visual vocabulary. Crane had fun with this, tossing in an occasional «ker-splash» or «lickety-wop» along with what would become the more standard effects. Words as well as images became vehicles for carrying along his increasingly fast-paced storylines.[12]

In 2002, DC Comics introduced a villain named Onomatopoeia, an athlete, martial artist, and weapons expert, who often speaks pure sounds.[clarification needed]

Advertising uses onomatopoeia for mnemonic purposes, so that consumers will remember their products, as in Alka-Seltzer’s «Plop, plop, fizz, fizz. Oh, what a relief it is!» jingle, recorded in two different versions (big band and rock) by Sammy Davis, Jr.

Rice Krispies (US and UK) and Rice Bubbles (AU)[clarification needed] make a «snap, crackle, pop» when one pours on milk. During the 1930s, the illustrator Vernon Grant developed Snap, Crackle and Pop as gnome-like mascots for the Kellogg Company.

Sounds appear in road safety advertisements: «clunk click, every trip» (click the seatbelt on after clunking the car door closed; UK campaign) or «click, clack, front and back» (click, clack of connecting the seat belts; AU campaign) or «click it or ticket» (click of the connecting seat belt, with the implied penalty of a traffic ticket for not using a seat belt; US DOT (Department of Transportation) campaign).

The sound of the container opening and closing gives Tic Tac its name.

Manner imitation

In many of the world’s languages, onomatopoeic-like words are used to describe phenomena beyond the purely auditive. Japanese often uses such words to describe feelings or figurative expressions about objects or concepts. For instance, Japanese barabara is used to reflect an object’s state of disarray or separation, and shiiin is the onomatopoetic form of absolute silence (used at the time an English speaker might expect to hear the sound of crickets chirping or a pin dropping in a silent room, or someone coughing). In Albanian, tartarec is used to describe someone who is hasty. It is used in English as well with terms like bling, which describes the glinting of light on things like gold, chrome or precious stones. In Japanese, kirakira is used for glittery things.

Examples in media

- James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) coined the onomatopoeic tattarrattat for a knock on the door.[13] It is listed as the longest palindromic word in The Oxford English Dictionary.[14]

- Whaam! (1963) by Roy Lichtenstein is an early example of pop art, featuring a reproduction of comic book art that depicts a fighter aircraft striking another with rockets with dazzling red and yellow explosions.

- In the 1960s TV series Batman, comic book style onomatopoeic words such as wham!, pow!, biff!, crunch! and zounds! appear onscreen during fight scenes.

- Ubisoft’s XIII employed the use of comic book onomatopoeic words such as bam!, boom! and noooo! during gameplay for gunshots, explosions and kills, respectively. The comic-book style is apparent throughout the game and is a core theme, and the game is an adaptation of a comic book of the same name.

- The chorus of American popular songwriter John Prine’s song «Onomatopoeia» incorporates onomatopoeic words: «Bang! went the pistol», «Crash! went the window», «Ouch! went the son of a gun».

- The marble game KerPlunk has an onomatopoeic word for a title, from the sound of marbles dropping when one too many sticks has been removed.

- The Nickelodeon cartoon’s title KaBlam! is implied to be onomatopoeic to a crash.

- Each episode of the TV series Harper’s Island is given an onomatopoeic name which imitates the sound made in that episode when a character dies. For example, in the episode titled «Bang» a character is shot and fatally wounded, with the «Bang» mimicking the sound of the gunshot.

- Mad Magazine cartoonist Don Martin, already popular for his exaggerated artwork, often employed creative comic-book style onomatopoeic sound effects in his drawings (for example, thwizzit is the sound of a sheet of paper being yanked from a typewriter). Fans have compiled The Don Martin Dictionary, cataloging each sound and its meaning.

Cross-linguistic examples

In linguistics

A key component of language is its arbitrariness and what a word can represent,[clarification needed] as a word is a sound created by humans with attached meaning to said sound.[15] No one can determine the meaning of a word purely by how it sounds. However, in onomatopoeic words, these sounds are much less arbitrary; they are connected in their imitation of other objects or sounds in nature. Vocal sounds in the imitation of natural sounds doesn’t necessarily gain meaning, but can gain symbolic meaning.[clarification needed][16] An example of this sound symbolism in the English language is the use of words starting with sn-. Some of these words symbolize concepts related to the nose (sneeze, snot, snore). This does not mean that all words with that sound relate to the nose, but at some level we recognize a sort of symbolism associated with the sound itself. Onomatopoeia, while a facet of language, is also in a sense outside of the confines of language.[17]

In linguistics, onomatopoeia is described as the connection, or symbolism, of a sound that is interpreted and reproduced within the context of a language, usually out of mimicry of a sound.[18] It is a figure of speech, in a sense. Considered a vague term on its own, there are a few varying defining factors in classifying onomatopoeia. In one manner, it is defined simply as the imitation of some kind of non-vocal sound using the vocal sounds of a language, like the hum of a bee being imitated with a «buzz» sound. In another sense, it is described as the phenomena of making a new word entirely.

Onomatopoeia works in the sense of symbolizing an idea in a phonological context, not necessarily constituting a direct meaningful word in the process.[19] The symbolic properties of a sound in a word, or a phoneme, is related to a sound in an environment, and are restricted in part by a language’s own phonetic inventory, hence why many languages can have distinct onomatopoeia for the same natural sound. Depending on a language’s connection to a sound’s meaning, that language’s onomatopoeia inventory can differ proportionally. For example, a language like English generally holds little symbolic representation when it comes to sounds, which is the reason English tends to have a smaller representation of sound mimicry then a language like Japanese that overall has a much higher amount of symbolism related to the sounds of the language.

Evolution of language

In ancient Greek philosophy, onomatopoeia was used as evidence for how natural a language was: it was theorized that language itself was derived from natural sounds in the world around us. Symbolism in sounds was seen as deriving from this.[20] Some linguists hold that onomatopoeia may have been the first form of human language.[17]

Role in early language acquisition

When first exposed to sound and communication, humans are biologically inclined to mimic the sounds they hear, whether they are actual pieces of language or other natural sounds.[21] Early on in development, an infant will vary his/her utterances between sounds that are well established within the phonetic range of the language(s) most heavily spoken in their environment, which may be called «tame» onomatopoeia, and the full range of sounds that the vocal tract can produce, or «wild» onomatopoeia.[19] As one begins to acquire one’s first language, the proportion of «wild» onomatopoeia reduces in favor of sounds which are congruent with those of the language they are acquiring.

During the native language acquisition period, it has been documented that infants may react strongly to the more wild-speech features to which they are exposed, compared to more tame and familiar speech features. But the results of such tests are inconclusive.

In the context of language acquisition, sound symbolism has been shown to play an important role.[16] The association of foreign words to subjects and how they relate to general objects, such as the association of the words takete and baluma with either a round or angular shape, has been tested to see how languages symbolize sounds.

In other languages

Japanese

The Japanese language has a large inventory of ideophone words that are symbolic sounds. These are used in contexts ranging from day to day conversation to serious news.[22] These words fall into four categories:

- Giseigo: mimics humans and animals. (e.g. wanwan for a dog’s bark)

- Giongo: mimics general noises in nature or inanimate objects. (e.g. zaazaa for rain on a roof)

- Gitaigo: describes states of the external world

- Gijōgo: describes psychological states or bodily feelings.

The two former correspond directly to the concept of onomatopoeia, while the two latter are similar to onomatopoeia in that they are intended to represent a concept mimetically and performatively rather than referentially, but different from onomatopoeia in that they aren’t just imitative of sounds. For example, shiinto represents something being silent, just as how an anglophone might say «clatter, crash, bang!» to represent something being noisy. That «representative» or «performative» aspect is the similarity to onomatopoeia.

Sometimes Japanese onomatopoeia produces reduplicated words.[20]

Hebrew

As in Japanese, onomatopoeia in Hebrew sometimes produces reduplicated verbs:[23]: 208

-

- שקשק shikshék «to make noise, rustle».[23]: 207

- רשרש rishrésh «to make noise, rustle».[23]: 208

Malay

There is a documented correlation within the Malay language of onomatopoeia that begin with the sound bu- and the implication of something that is rounded, as well as with the sound of -lok within a word conveying curvature in such words like lok, kelok and telok (‘locomotive’, ‘cove’, and ‘curve’ respectively).[24]

Arabic

The Qur’an, written in Arabic, documents instances of onomatopoeia.[17] Of about 77,701 words, there are nine words that are onomatopoeic: three are animal sounds (e.g., «mooing»), two are sounds of nature (e.g.; «thunder»), and four that are human sounds (e.g., «whisper» or «groan»).

Albanian

There is wide array of objects and animals in the Albanian language that have been named after the sound they produce. Such onomatopoeic words are shkrepse (matches), named after the distinct sound of friction and ignition of the match head; take-tuke (ashtray) mimicking the sound it makes when placed on a table; shi (rain) resembling the continuous sound of pouring rain; kukumjaçkë (Little owl) after its «cuckoo» hoot; furçë (brush) for its rustling sound; shapka (slippers and flip-flops); pordhë (loud flatulence) and fëndë (silent flatulence).

Hindi-Urdu

In Hindi and Urdu, onomatopoeic words like bak-bak, churh-churh are used to indicate silly talk. Other examples of onomatopoeic words being used to represent actions are fatafat (to do something fast), dhak-dhak (to represent fear with the sound of fast beating heart), tip-tip (to signify a leaky tap) etc. Movement of animals or objects is also sometimes represented with onomatopoeic words like bhin-bhin (for a housefly) and sar-sarahat (the sound of a cloth being dragged on or off a piece of furniture). khusr-phusr refers to whispering. bhaunk means bark.

See also

- Anguish Languish

- Japanese sound symbolism

- List of animal sounds

- List of onomatopoeias

- Sound mimesis in various cultures

- Sound symbolism

- Vocal learning

Notes

- ^ ;[1][2] from the Greek ὀνοματοποιία;[3] ὄνομα for «name»[4] and ποιέω for «I make»,[5] adjectival form: «onomatopoeic» or «onomatopoetic»; also onomatopœia

References

Citations

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- ^ Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2

- ^ ὀνοματοποιία, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ὄνομα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ ποιέω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle, Hugh Bredin, The Johns Hopkins University, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ Definition of Onomatopoeia, Retrieved November 14, 2013

- ^ onomatopoeia at merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Basic Reading of Sound Words-Onomatopoeia, Yale University, retrieved October 11, 2013

- ^ «English Oxford Living Dictionaries». Archived from the original on December 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Earl R. (1998). A Grammar of Iconism. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780838637647.

- ^ DeForest, Tim (2004). Storytelling in the Pulps, Comics, and Radio: How Technology Changed Popular Fiction in America. McFarland. ISBN 9780786419029.

- ^ James Joyce (1982). Ulysses. Editions Artisan Devereaux. pp. 434–. ISBN 978-1-936694-38-9.

… I was just beginning to yawn with nerves thinking he was trying to make a fool of me when I knew his tattarrattat at the door he must …

- ^ O.A. Booty (January 1, 2002). Funny Side of English. Pustak Mahal. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-81-223-0799-3.

The longest palindromic word in English has twelve letters: tattarrattat. This word, appearing in the Oxford English Dictionary, was invented by James Joyce and used in his book Ulysses (1922), and is an imitation of the sound of someone [farting].

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (January 1, 2011). «The anatomy of onomatopoeia». PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ a b RHODES, R (1994). «Aural Images». In J. Ohala, L. Hinton & J. Nichols (Eds.) Sound Symbolism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Seyedi, Hosein; Baghoojari, ELham Akhlaghi (May 2013). «The Study of Onomatopoeia in the Muslims’ Holy Write: Qur’an» (PDF). Language in India. 13 (5): 16–24.

- ^ Bredin, Hugh (August 1, 1996). «Onomatopoeia as a Figure and a Linguistic Principle». New Literary History. 27 (3): 555–569. doi:10.1353/nlh.1996.0031. ISSN 1080-661X. S2CID 143481219.

- ^ a b Laing, C. E. (September 15, 2014). «A phonological analysis of onomatopoeia in early word production». First Language. 34 (5): 387–405. doi:10.1177/0142723714550110. S2CID 147624168.

- ^ a b Osaka, Naoyuki (1990). «Multidimensional Analysis of Onomatopoeia – A note to make sensory scale from word». Studia phonologica. 24: 25–33. hdl:2433/52479. NAID 120000892973.

- ^ Assaneo, María Florencia; Nichols, Juan Ignacio; Trevisan, Marcos Alberto (December 14, 2011). «The Anatomy of Onomatopoeia». PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28317. Bibcode:2011PLoSO…628317A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028317. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3237459. PMID 22194825.

- ^ Inose, Hiroko. «Translating Japanese Onomatopoeia and Mimetic Words.» N.p., n.d. Web.

- ^ a b c Zuckermann, Ghil’ad (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695 [1]

- ^ WILKINSON, R. J. (January 1, 1936). «Onomatopoeia in Malay». Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 14 (3 (126)): 72–88. JSTOR 41559855.

General references

- Crystal, David (1997). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55967-7.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). Greek Grammar. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. p. 680. ISBN 0-674-36250-0.

External links

- Derek Abbott’s Animal Noise Page

- Over 300 Examples of Onomatopoeia

- BBC Radio 4 show discussing animal noises

- Tutorial on Drawing Onomatopoeia for Comics and Cartoons (using fonts)

- WrittenSound, onomatopoeic word list

- Examples of Onomatopoeia

Nasal E [ẽ] always blocks the palatalization,

1. be it alone as in: entender with a T, and not with a TCH: [ẽtẽ’de(h)], [ĩttẽ’de(h)]; dental with a D, and not with a J: [dẽ’taʊ̯];

2. or in a diphthong: vendem [‘vẽdẽj̃], vintém [vĩ’tẽj̃]

The general rules for palatalization:

1). All graphemes ti (ty), di are palatalized (tio, adiar, Paraty).

2) t, d before consonants are palatalized, more often than not with a helping vowel [ɪ] right after it: ritmo, admissão, adjetivo, admirar, advogado: ritmo [‘hɪʧimʊ];

yes you can even hear [ʧɪsun’ɐ̃mi] for tsunami.

3) final -te, -de are palatalized:

a) in singular, unless speaking slowly and emphatically, the final vowel may be silent: noite [nojʧ(ɪ)]

b) in plural, unless speaking slowly and emphatically, —tes can become [ts] (the consonant in pizza), —des becomes [ds]: den[ts] perfeitos, cida[ds] portuguesas…

4) unstressed initial de-, te- before a vowel may be palatalized, but it depends on a dialect (and on a speaker), and on the word: initial te- before a is normally palatalized: teatro with tchi [ʧi] sounds more neutral than the pronunciation with [te-] which sounds more regional; with other initial te- it’s more complicated, the palatalization is less common: tesoura with [te] sounds a bit more neutral than the one with [ʧi] which sounds more Carioca.

5) de (of) is normally [ʤi] or even just [ʤ], being different than dê (subjunctive and imperative of DAR).

Only in very formal spelling pronunciation it is pronounced as [de], as popularized by a TV host Silvio Santos: um milhão [de] reais (in spelling pronunciation: um milhão dê reais).

The only exception is DE REPENTE (suddenly) pronounced DÊRREPENTCH(I) [but it’s because many people think it spelled as a one word: derrepente!!!, see the rule 6))

6) the prefix de- is complicated, it depends on a dialect (and on a speaker), and on the word: depois with [ʤi-]

is typical of São Paulo, the neutral Brazilian Portuguese »depois» is with [de-], with demais is the opposite [de-] sounds regional ([de’majs] would sound as dê mais = give (some) more, so it’s normally avoided)

7) the prefix des- is complicated, the more southern or the more formal pronunciation is, the [des-, dez-] is more common, but it depends on a word. Rio Portuguese favors the palatalization, but it still depends on the word, the speed of speech or the speaker himself/herself. For des- you can hear [dez-/ des-, ʤiz-, ʤis-, or -dz/-ds-].

(The answer to your question: why there are no palatalizations in entender?

It’s because there are no final -te (or -tes), and -de (or —des) in this word, nor -te-/-de- before a vowel, nor initial de— or des-).

Sometimes, you might want to describe a crying sound that someone makes rather than use a word that’s similar to “crying.” In this case, we use cry onomatopoeia, and in this article, we’ll explore some of the best options for it.

Which Words Best Describe A Crying Sound?

There are many words that are used to describe a crying sound. Some of the best include “boohoo,” “blubber,” “sob sob,” and “waah.” Most of these are known as onomatopoeia, which is a word created from the sound it makes.

In this article, we’ll look at the following words:

- Boohoo

- Blubber

- Sob sob

- Waah

- Bawl

- Sniff Sniff

Boohoo

We’ll start with the most common choice and one of the better forms of cry onomatopoeia out there. “Boohoo” is a very popular choice when you want to describe the sound of someone crying, so let’s look further into it.

The word “boohoo” can be defined, and it’s included in The Cambridge Dictionary to mean “the sound of noisy crying like a child’s.” This is a good way of seeing what we mean about onomatopoeia.

The definition of the word “boohoo” includes that it is a replication of a sound. That means that it’s common for young children to physically make a noise like “boohoo” when they’re crying – which is incidentally the entire origin of the word.

You may also see the word written as “boo hoo” to separate the two sounds even further by including a space.

- Boohoo! If you want to cry about it, go for it!

- Oh, boohoo! It must suck to have all this money!

- Boohoo! I can’t believe you’re sulking about this.

- Boohoo! She left me!

As you can see from the examples of it being used, “boohoo” (and most crying onomatopoeia words) are mostly used sarcastically to insult someone. You might also see someone use it when they want to address a sad situation that’s happened to them.

It’s worth noting that someone doesn’t have to be physically crying to reply “boohoo” to them. Even if they’re simply moaning about something that they don’t like, “boohoo” might be a good choice. Either way, it’s seen as rude, so be careful!

Blubber

Next, we’ll look at “blubber” as a word you can use that means someone is crying. While not strictly an onomatopoeia word like “boohoo,” it still resembles a sound that people make when they’re crying.

According to The Cambridge Dictionary, “blubber” can be defined as “to cry in a noisy way like a child.”

The “noisy” part of the definition is what we want to pay attention to when we’re talking about it as an onomatopoeic word. It works well because you can almost hear someone “blubber” when they’re crying, especially a child you believe to be inconsolable.

Let’s go through some examples when you might be able to use the word “blubber.” Before we do, though, it’s important to know that “blubber” is also considered a verb, meaning it has varying forms.

- Oh, quit your blubbing! It’s not that bad!

- Stop blubbering like a buffoon and help me!

- Keep your blubbing to yourself and get over it.

- You’re a blubbering mess!

As you can see, it’s common to use “blubber” in the verb form to say that someone is “blubbing” or “blubbering.” Generally, when we simply say “blubber,” we’re talking about it in the present tense.

It’s also worth noting that “blubber” can also mean “fat,” so be careful who you use it on as they might take it the wrong way if you don’t use the correct verb form!

Sob Sob

“Sob sob” is a great example of cry onomatopoeia that covers another sound that people make when they cry. This one doesn’t have to relate as much to the noise children make either, as adults are capable of “sobbing” too.

The definition of “sob,” according to The Cambridge Dictionary, is “to cry noisily, taking in deep breaths.” It’s the noise that most people make when they’re crying. When we add a second “sob,” it turns into onomatopoeia to describe the sound of it.

One “sob” on its own is used as a verb. However, the phrase “sob sob” is used as a repetitive form of cry onomatopoeia, which we can use again to make a sarcastic comment about someone either complaining or crying about something menial or trivial.

- Oh, sob sob. Get over it and move on!

- Sob sob! You couldn’t cry anymore if you tried!

- Sob sob to you! Your life must be so hard to deal with!

- Stop with all your sob sobs! We don’t want to hear it!

As you can see, generally, we use “sob sob” or other forms of onomatopoeia when we’re trying to insult someone. We want to take away from the gravity of the thing that’s upset them by using a rude word to inform them that they’re ridiculous.

Usually, we want to say “there are worse things that could happen” as a way to remind them that whatever is upsetting them isn’t the end of the world.

Waah

“Waah” is a very common word that people use to talk about the sound someone makes when crying. It can also be spelled in varying ways based on who is using it.

“Waah” is the only word on this list that doesn’t have a dictionary listing. It works well because it copies the noise people make when they’re crying. It can be spelled many ways, like “waah,” “waa,” “wah wah,” “wah-wah,” “waaaa,” and “wah.”

It’s up to you how many “A” letters you include in the word, as well as whether you want the “H” at the end. The spelling doesn’t directly impact the meaning; however, it’s widely accepted that the more “A”s you use, the more you’re trying to insult the person you’re talking to.

- Wah wah! You can’t stop crying about it, can you?

- Oh, waaah! Get over yourself!

- Waah! You want to talk about your little problems some more?

- Waa! I can’t believe this happened!

As you can see, we’re still using this to insult people, and it’s typically a rude thing to do. However, in the final example, you can see someone using the word to address their own situation.

It’s possible to use any of these words to show someone that you’re sad about something happening. Generally, we’ll write words like this in text messages over anything else.

Bawl

Next, let’s look at “bawl.” This is another verb in the list but also works as a way to show the sound someone makes when they’re crying.

The definition of “bawl,” according to The Cambridge Dictionary, is “to cry or shout loudly.” We use it when we want to say that someone is upset about something and wants their feelings heard.

Generally, this one isn’t as insulting as some of the others on the list. It can simply be used to describe the action of someone crying.

- He’s bawling in the corner over there.

- I can’t stop bawling over the recent news!

- You’ve been bawling for thirty-five minutes!

- Will you please stop bawling your eyes out?

Because it’s a verb, we can use it in varying forms. In this case, we’re using the present participle “bawling,” as it’s the most common form you’ll come across.

Sniff Sniff

The final word we want to go over is using “sniff sniff” as cry onomatopoeia. We can use this to talk about a quieter cry, mostly where someone is sniffing about something. Generally, the news isn’t as devastating, but it can still be sad.

According to The Cambridge Dictionary, “sniff” means “to take air in quickly through your nose, usually to stop the liquid inside the nose from flowing out.” We typically “sniff” to stop our noses from running while we cry.

We’ll include a few examples of when you might see “sniff sniff” in a sentence to help you understand its usage.

- Sniff sniff, I don’t suppose you heard the news?

- Sniff sniff! You need to stop crying.

- Oh, sniff sniff! Pull yourself together.,

- Sniff sniff, have you heard?

As you can see, we might insult someone when we say it, but we might also be drawing attention to something fairly sad. Usually, “sniff sniff” isn’t used in the more devastating scenarios, but in places where we’re only kind of sad.

What Is The Best Way To Describe A Baby Crying Sound In Words?

Finally, we’ll quickly cover what the best way to describe a baby crying might be. We’ve already covered a few of the best sounds for it.

“Boohoo” and “blubber” are the best ways to describe a baby crying. Both of their definitions talk about the noise a child makes, which closely relates to how babies sound when they cry. “Boohoo” is the best cry onomatopoeia for it, while “blubber” is the best verb.

It’s up to you which one you want to use in what case. Generally, if you use “boohoo” to talk about a baby, it might not be received well, if you say the following:

- Boohoo! The baby’s crying.

This example can come across as rude or insensitive if you’re not careful with who you say it to!

Martin holds a Master’s degree in Finance and International Business. He has six years of experience in professional communication with clients, executives, and colleagues. Furthermore, he has teaching experience from Aarhus University. Martin has been featured as an expert in communication and teaching on Forbes and Shopify. Read more about Martin here.