Most words convey several

concepts and thus possess the corresponding number of meanings. A

word having several meanings is called

polysemantic,

and the

ability of words to have more than one meaning is described by the

term polysemy.

Most English words are

polysemantic.

It should be noted that the wealth of expressive resources of a

language largely depends on the degree to which polysemy has

developed in the language.

The number of sound

combinations that human speech organs can produce is limited.

Therefore at a certain stage of language development the production

of new words by morphological means becomes limited, and polysemy

becomes increasingly important in providing the means for enriching

the vocabulary. The process of

enriching the vocabulary does not consist merely in adding new words

to it, but, also, in the constant development of polysemy.

The system of meanings of

any polysemantic word develops gradually, mostly over the centuries,

as more and more new meanings are either added to old ones, or oust

some of them.

So the

complicated processes of polysemy

development involve both the appearance of new meanings and the loss

of old ones. Yet,

the general tendency with English vocabulary at the modern stage of

its history is to increase the total number of its meanings and in

this way to provide for a quantitative and qualitative growth of the

language’s expressive resources.

Thus, stone

has the

following meanings:

1)

hard compact

nonmetallic material of which rocks are made, a small lump of rock;

2)

pebble;

3)

the woody

central part of such fruits as the peach and plum, that contains the

seed;

4)

Jewellery,

short for gemstone;

5)

a unit of

weight, used esp. to Brit, a unit of weight, used esp. to express

human body weight, equal to 14

pounds or

6.350

kilograms;

6)

a calculous

concretion in the body, as in the kidney, gallbladder, or urinary

bladder; a disease arising from such a concretion.

My brother-in-law, he says

gallstones hurt worse than anything. Except maybe kidney stones.

(King)

The bank became low again,

and Miro crossed the brook by running lightly on the moss-covered

stones.

(Card)

“Here,” she said, and

took off a slim silver necklace with an intricately carved pale jade

stone the

size of a grape. (Hamilton)

Smoke curled lazily from the

brown and gray rock chimney made of rounded river stones.

(Foster)

Ukrainian

земля

is also

polysemantic:

1) третя від Сонця планета;

2) верхній шар земної кори;

3) речовина темно-бурого кольору, що

входить до складу земної кори;

4) суша (на відміну від водного простору);

5) країна, край, держава.

Polysemy

is very characteristic of the English vocabulary due to the

monosyllabic character of English words and the predominance of root

words. The greater the frequency of the word, the greater the number

of meanings that constitute its semantic structure. Frequency −

combinability

− polysemy

are closely connected. A special formula known as Zipf’s

law has

been worked out to express the correlation between frequency, word

length and polysemy: the shorter the word, the higher its frequency

of use; the higher the frequency, the wider its combinability,

i.e. the more

word combinations it enters; the wider its combinability, the more

meanings are realized in these contexts.

The word in one of its

meanings is termed a lexico-semantic

variant of

this word. The problem in polysemy is that of interrelation of

different lexico-semantic variants. There may be no single semantic

component common to all lexico-semantic variants but every variant

has something in common with at least one of the others.

All the lexico-semantic

variants of a word taken together form its semantic

structure

or semantic

paradigm.

The word

face, for

example, according to the dictionary data has the following semantic

structure:

1. The

front part of the head: He

fell on his face.

2. Look,

expression: a

sad face, smiling faces, she is a good judge of faces.

3. Surface,

facade: face

of a

clock, face of a building, He laid his cards face down.

4. Impudence,

boldness, courage: put

a good/brave/boldface on smth, put a new face on smth, the face of

it, have the face to do,

save one’s

face.

5. Style

of typecast for printing: bold-face

type.

Meaning is direct

when it nominates the referent without the help of a context, in

isolation; meaning is figurative

when the referent is named and at the same time characterized through

its similarity with other objects, Cf.

-

direct meaning

figurative meaning

tough

meathead

foot

face

tough

politicianhead

of a cabbagefoot

of a mountainput a new face on smth.

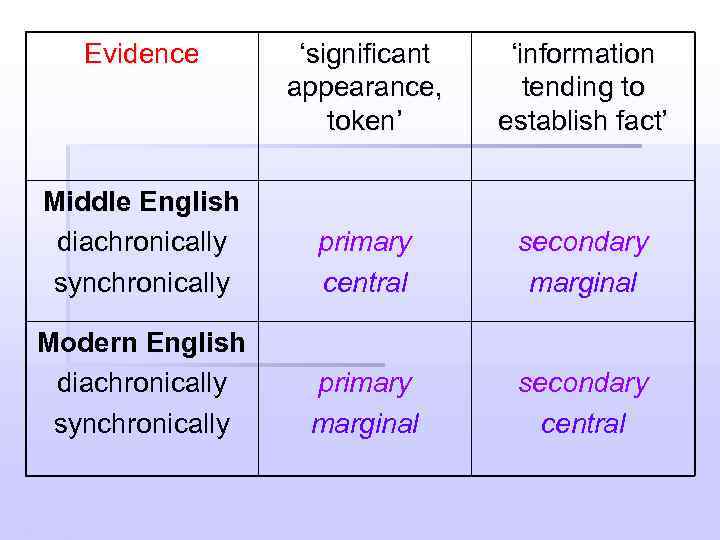

Differentiation between the

terms primary/secondary

main/derived

meanings

is connected with two approaches to polysemy: diachrpnic

and synchronic.

If viewed diachronically,

polysemy is understood as the growth and development (or change) in

the semantic structure of the word.

primary meaning

→

secondary

meanings

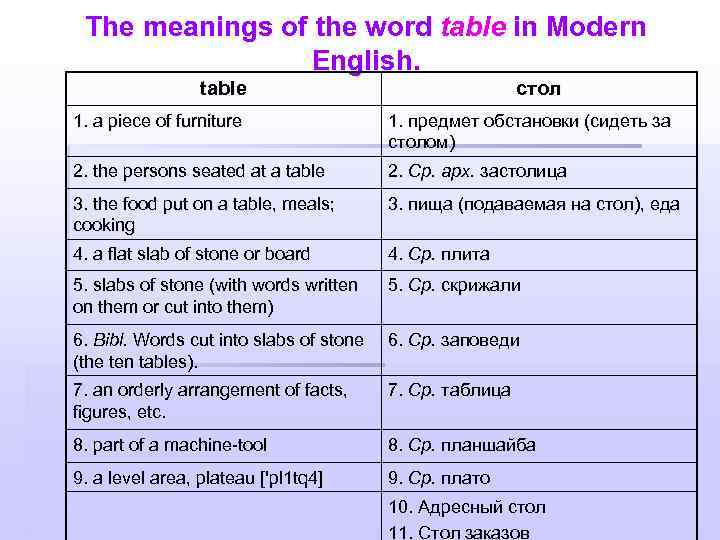

table

―

Old Eng “a flat slab of stone or wood”.→

derived

from the primary meaning

Synchronically

polysemy is understood as the coexistence of various meanings of the

same word at a certain historical period of the development of the

English language. In that case the problem of interrelation and

interdependence of individual meanings making up the semantic

structure of the word must be investigated from different points of

view, that of main/derived, central/peripheric meanings.

An objective criterion of

determining the main or central meaning is the frequency of its

occurance in speech. Thus, the main meaning of the word table

in Modern

English is “a piece of furniture”.

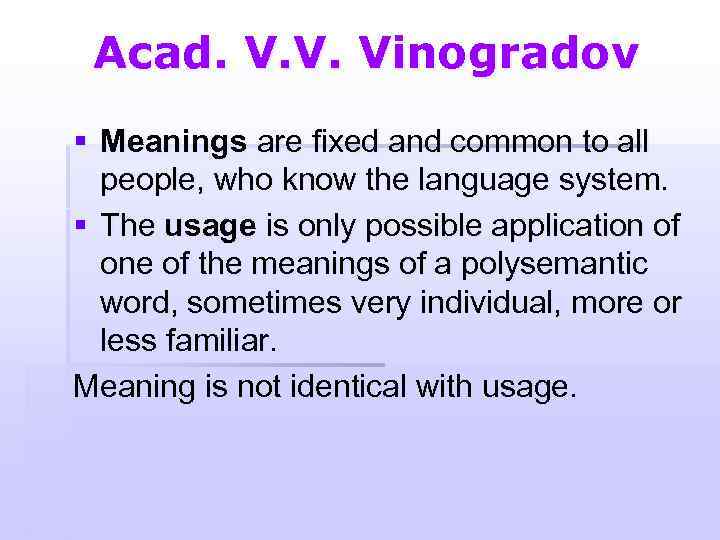

Polysemy is a phenomenon of

language, not of speech. As a rule the contextual meaning represents

only one of the possible lexico-semantic variants of the word. So

polysemy does not interfere with the communicative function of the

language because the situation and the context cancel all the

unwanted meanings, as in the following sentences:

The steak is tough.

This is a tough problem.

Prof. Holborn is a tough examiner.

When analysing the semantic

structure of a polysemantic word, it is necessary to

distinguish between two levels of analysis.

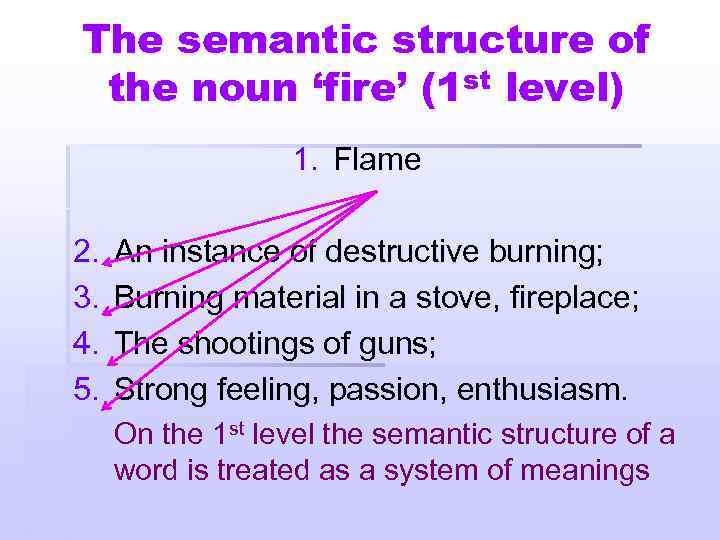

On the first level, the

semantic structure of a word is treated as a system of meanings.

For example, the semantic structure of the noun fire

could be

roughly presented by this scheme (only the most frequent meanings are

given):

Figure 2

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

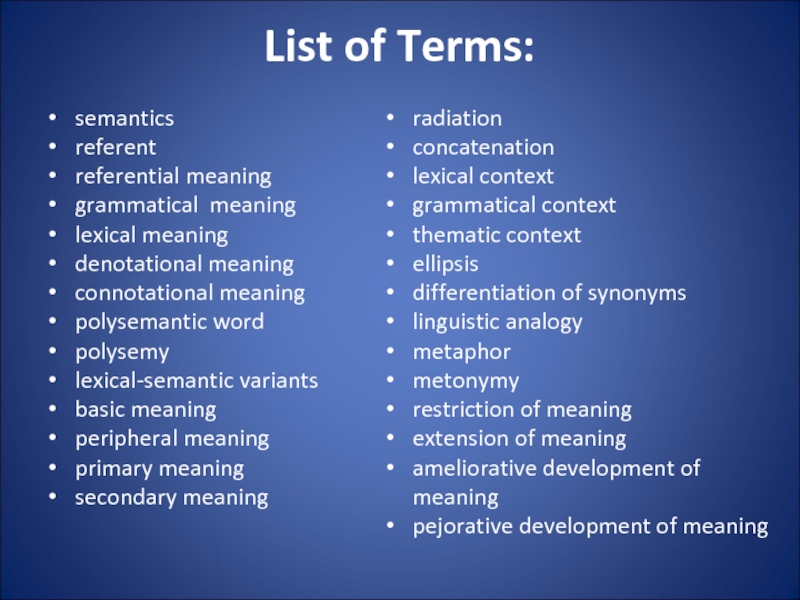

Слайд 1Lecture 3

Semantic Structure of the Word

and Its Changes

Слайд 2Plan:

Semantics / semasiology. Different approaches to word-meaning.

Types

of word-meaning.

Polysemy. Semantic structure of words.

Meaning and context.

Change of word-meaning: the causes, nature and results.

Слайд 3List of Terms:

semantics

referent

referential meaning

grammatical meaning

lexical meaning

denotational meaning

connotational

meaning

polysemantic word

polysemy

lexical-semantic variants

basic meaning

peripheral meaning

primary meaning

secondary meaning

radiation

concatenation

lexical

context

grammatical context

thematic context

ellipsis

differentiation of synonyms

linguistic analogy

metaphor

metonymy

restriction of meaning

extension of meaning

ameliorative development of meaning

pejorative development of meaning

Слайд 4

It is meaning that makes language

useful.

George A. Miller,

The science of

word, 1991

Слайд 5

1. Semantics / semasiology. Different approaches to

word-meaning

Слайд 6

The function of the word

as a unit of communication is possible

by its possessing a meaning.

Among the word’s various characteristics meaning is the most important.

Слайд 7

«The Meaning of Meaning» (1923) by C.K.

Ogden and I.A. Richards – about 20

definitions of meaning

Слайд 8Meaning of a linguistic unit, or linguistic

meaning, is studied by semantics

(from Greek

– semanticos ‘significant’)

Слайд 9

This linguistic study was pointed

out in 1897 by M. Breal

Слайд 10

Semasiology is a synonym for

‘semantics’

(from Gk. semasia ‘meaning’

+ logos ‘learning’)

Слайд 11Different Approaches to Word Meaning:

ideational (or conceptual)

referential

functional

Слайд 12

The ideational theory can be

considered the earliest theory of meaning.

It states that meaning originates in the mind in the form of ideas, and words are just symbols of them.

Слайд 13A difficulty:

not clear why communication and

understanding are possible if linguistic expressions stand

for individual personal ideas.

Слайд 14Meaning:

a concept with specific structure.

Слайд 15

Do people speaking different languages have different

conceptual systems?

If people speaking different languages

have the same conceptual systems why are identical concepts expressed by correlative words having different lexical meanings?

Слайд 16

finger ‘one of 10 movable parts of

joints at the end of each human

hand, or one of 8 such parts as opposed to the thumbs‘

and

палец ‘подвижная конечная часть кисти руки, стопы ноги или лапы животного’

Слайд 17

Referential theory is based

on interdependence of things, their concepts and

names.

Слайд 18

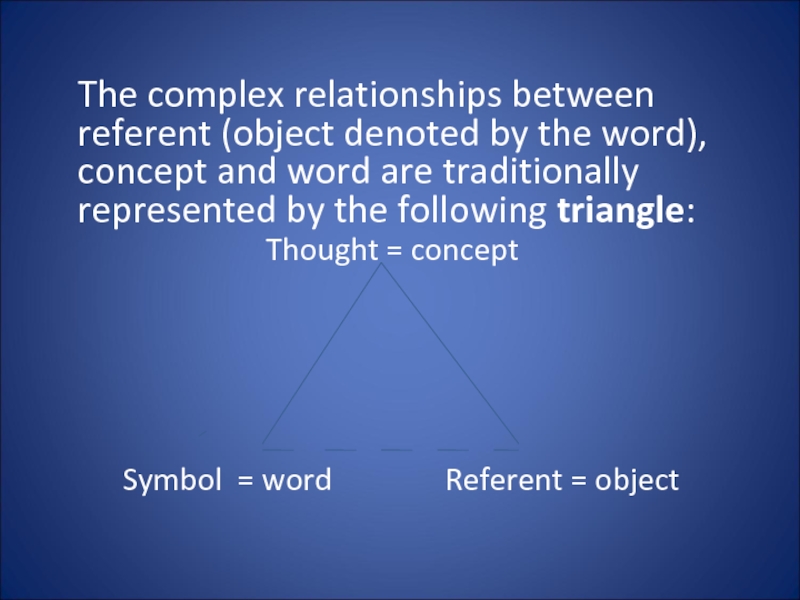

The complex relationships between referent

(object denoted by the word), concept and

word are traditionally represented by the following triangle:

Thought = concept

Symbol = word Referent = object

Слайд 19

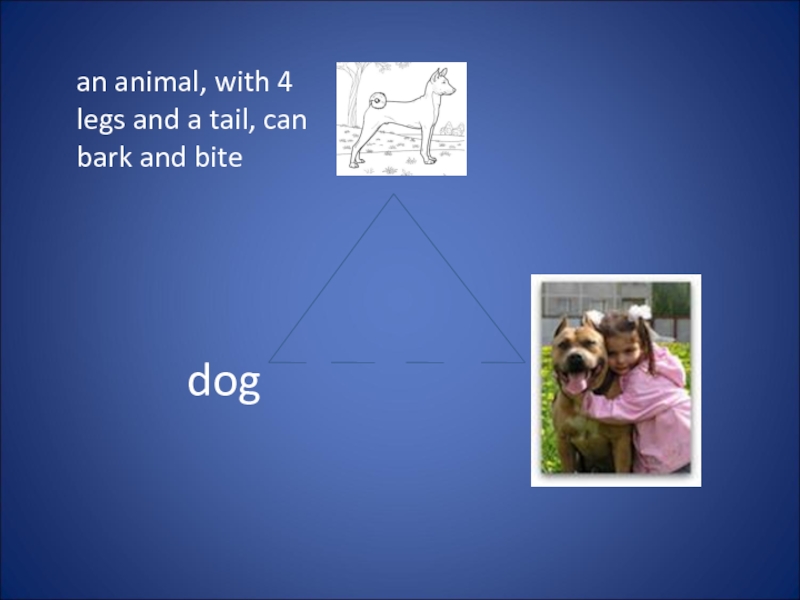

an animal, with 4

legs and a

tail, can bark and bite

dog

Слайд 20Meaning concept

different words having

different meanings may be used to express

the same concept

Слайд 21Concept of dying

die

pass away

kick the

bucket

join the majority, etc

Слайд 22Meaning symbol

In different languages:

a

word with the same meaning have different

sound forms (dog, собака)

words with the same sound forms have different meaning (лук, look)

Слайд 23Meaning referent

to denote one

and the same object we can give

it different names

Слайд 24A horse

in various contexts:

horse,

animal,

creature,

it,

etc.

Слайд 25Word meaning:

the interrelation of

all three components of the semantic triangle:

symbol, concept and referent, though meaning is not equivalent to any of them.

Слайд 26

Functionalists study word meaning by

analysis of the way the word is

used in certain contexts.

Слайд 27

The meaning of a

word is its use in language.

Слайд 28cloud and cloudy

have different meanings because

in speech they function differently and occupy

different positions in relation to other words.

Слайд 29Meaning:

a component of the word

through which a concept is communicated

Слайд 31According to the conception of word meaning

as a specific structure:

functional meaning: part of

speech meaning (nouns usually denote «thingness», adjectives – qualities and states)

grammatical: found in identical sets of individual forms of different words (she goes/works/reads, etc.)

lexical: the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit highly individual and recurs in all the forms of a word (the meaning of the verb to work ‘to engage in physical or mental activity’ that is expressed in all its forms: works, work, worked, working, will work)

Слайд 32Lexical Meaning:

denotational

connotational

Слайд 33

Denotational lexical meaning provides correct reference of

a word to an individual object or

a concept.

It makes communication possible and is explicitly revealed in the dictionary definition (chair ‘a seat for one person typically having four legs and a back’).

Слайд 35

Connotational lexical meaning is an

emotional colouring of the word. Unlike denotational

meaning, connotations are optional.

Слайд 36Connotations:

Emotive charge may be inherent in word

meaning (like in attractive, repulsive) or may

be created by prefixes and suffixes (like in piggy, useful, useless).

It’s always objective because it doesn’t depend on a person’s perception.

Слайд 37

2. Stylistic reference refers the word to

a certain style:

neutral words

colloquial

bookish, or literary words

Eg. father – dad – parent .

Слайд 38

3. Evaluative connotations express approval or disapproval

(charming, disgusting).

4. Intensifying connotations are expressive and

emphatic (magnificent, gorgeous)

Слайд 39

Denotative component

Lonely = alone, without company

To glare

= to look

Connotative component

+ melancholy, sad

(emotive con.)

+ 1) steadily, lastingly (con. of duration)

+ 2) in anger, rage (emotive con.)

Слайд 40

3. Polysemy. Semantic structure of words. Meaning

and context

Слайд 41

A polysemantic word is a word having

more than one meaning.

Polysemy is the ability

of words to have more than one meaning.

Слайд 42

Most English words

are polysemantic.

A well-developed polysemy

is a great advantage in a language.

Слайд 43Monosemantic Words:

terms (synonym, bronchitis, molecule),

pronouns (this,

my, both),

numerals, etc.

Слайд 44The main causes of polysemy:

a large number

of:

1) monosyllabic words;

2) words of

long duration (that existed for centuries).

Слайд 45The sources of polysemy:

1) the process of

meaning change (meaning specialization: is used in

more concrete spheres);

2) figurative language (metaphor and metonymy);

3) homonymy;

4) borrowing of meanings from other languages.

Слайд 46blanket

a woolen covering used on beds,

a covering

for keeping a house warm,

a covering

of any kind (a blanket of snow),

covering in most cases (used attributively), e.g. we can say: a blanket insurance policy.

Слайд 47

Meanings of a polysemantic word

are organized in a semantic structure

Слайд 48Lexical-semantic variant

one of the meanings of

a polysemantic word used in speech

Слайд 49A Word’s Semantic Structure Is Studied:

Diachronically (in

the process of its historical development): the

historical development and change of meaning becomes central. Focus: the process of acquiring new meanings.

Synchronically (at a certain period of time): a co-existence of different meanings in the semantic structure of the word at a certain period of language development. Focus: value of each individual meaning and frequency of its occurrence.

Слайд 50

The meaning first registered in the language

is called primary.

Other meanings are secondary,

or derived, and are placed after the primary one.

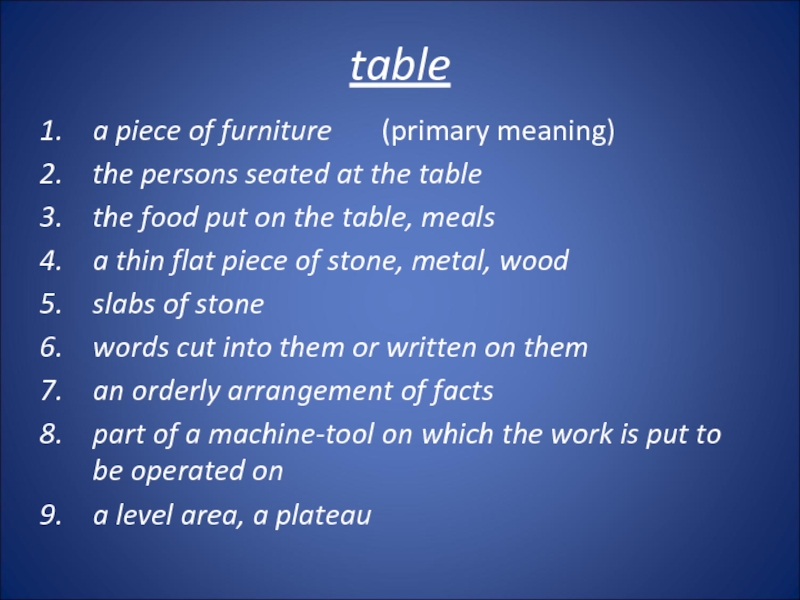

Слайд 51table

a piece of furniture

(primary meaning)

the persons seated at the

table

the food put on the table, meals

a thin flat piece of stone, metal, wood

slabs of stone

words cut into them or written on them

an orderly arrangement of facts

part of a machine-tool on which the work is put to be operated on

a level area, a plateau

Слайд 52

The meaning that first occurs to our

mind, or is understood without a special

context is called the basic or main meaning.

Other meanings are called peripheral or minor.

Слайд 53Fire

1. flame (main meaning)

2. an instance of destructive burning

e.g. a forest fire

4. the shooting of guns

e.g. to open fire

3. burning material in a stone, fireplace

e.g. a camp fire

5. strong feeling, passion

e.g. speech lacking fire

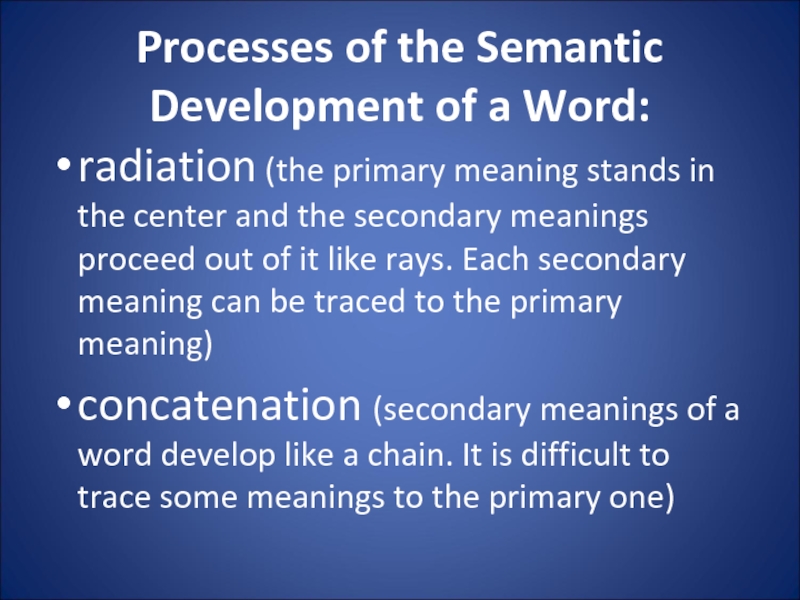

Слайд 54Processes of the Semantic Development of a

Word:

radiation (the primary meaning stands in the

center and the secondary meanings proceed out of it like rays. Each secondary meaning can be traced to the primary meaning)

concatenation (secondary meanings of a word develop like a chain. It is difficult to trace some meanings to the primary one)

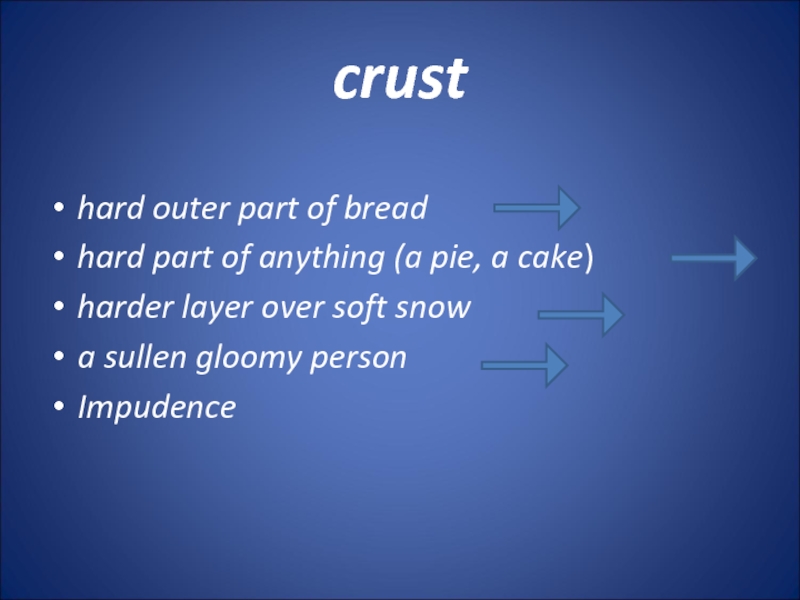

Слайд 55crust

hard outer part of bread

hard

part of anything (a pie, a cake)

harder

layer over soft snow

a sullen gloomy person

Impudence

Слайд 56

Polysemy exists not in speech but

in the language.

It’s easy to identify

the main meaning of a separate word. Other meanings are revealed in context.

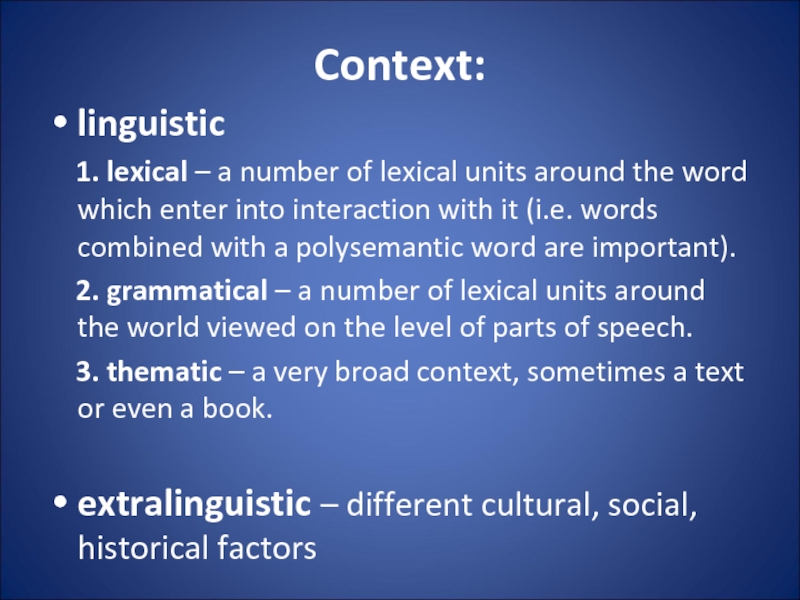

Слайд 57Context:

linguistic

1. lexical – a

number of lexical units around the word

which enter into interaction with it (i.e. words combined with a polysemantic word are important).

2. grammatical – a number of lexical units around the world viewed on the level of parts of speech.

3. thematic – a very broad context, sometimes a text or even a book.

extralinguistic – different cultural, social, historical factors

Слайд 58

4. Change of word-meaning: the causes, nature

and results

Слайд 59

The meaning of a word can

change in a course of time.

Слайд 60Causes of Change of

Word-meaning:

1. Extralinguistic (various

changes in the life of a speech

community, in economic and social structure, in ideas, scientific concepts)

e.g. “car” meant ‘a four-wheeled wagon’; now – ‘a motor-car’, ‘a railway carriage’ (in the USA)

“paper” is not connected anymore with “papyrus” – the plant from which it formerly was made.

2. Linguistic (factors acting within the language system)

Слайд 61Linguistic Causes:

1. ellipsis – in a phrase

made up of two words one of

these is omitted and its meaning is transferred to its partner.

e.g. “to starve” in O.E. = ‘to die’ + the word “hunger”. In the 16th c. “to starve” = ‘to die of hunger’.

e.g. daily = daily newspaper

Слайд 62Linguistic Causes:

2. differentiation (discrimination) of synonyms

– when a new word is borrowed

it may become a perfect synonym for the existing one. They have to be differentiated; otherwise one of them will die.

e.g. “land” in O.E. = both ‘solid part of earth’s surface’ and ‘the territory of the nation’. In the middle E. period the word “country” was borrowed as its synonym; ‘the territory of a nation’ came to be denoted mainly by “country”.

Слайд 63Linguistic Causes:

3. linguistic analogy – if one

of the members of the synonymic set

acquires a new meaning, other members of this set change their meaning too.

e.g. “to catch” acquired the meaning ‘to understand’; its synonyms “to grasp” and “to get” acquired this meaning too.

Слайд 64

The nature of semantic changes

is based on the secondary application of

the word form to name a different yet related concept.

Conditions to any semantic change: some connection between the old meaning and the new.

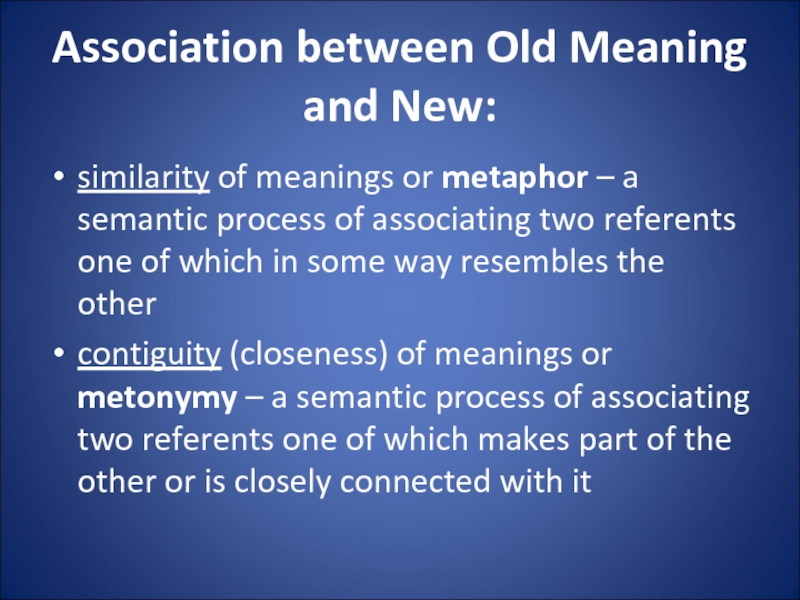

Слайд 65Association between Old Meaning and New:

similarity of

meanings or metaphor – a semantic process

of associating two referents one of which in some way resembles the other

contiguity (closeness) of meanings or metonymy – a semantic process of associating two referents one of which makes part of the other or is closely connected with it

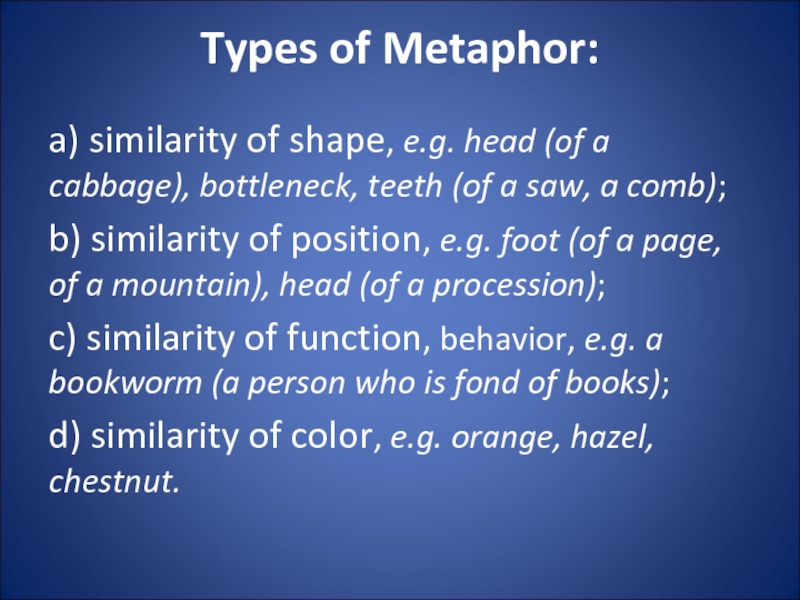

Слайд 66Types of Metaphor:

a) similarity of shape, e.g.

head (of a cabbage), bottleneck, teeth (of

a saw, a comb);

b) similarity of position, e.g. foot (of a page, of a mountain), head (of a procession);

c) similarity of function, behavior, e.g. a bookworm (a person who is fond of books);

d) similarity of color, e.g. orange, hazel, chestnut.

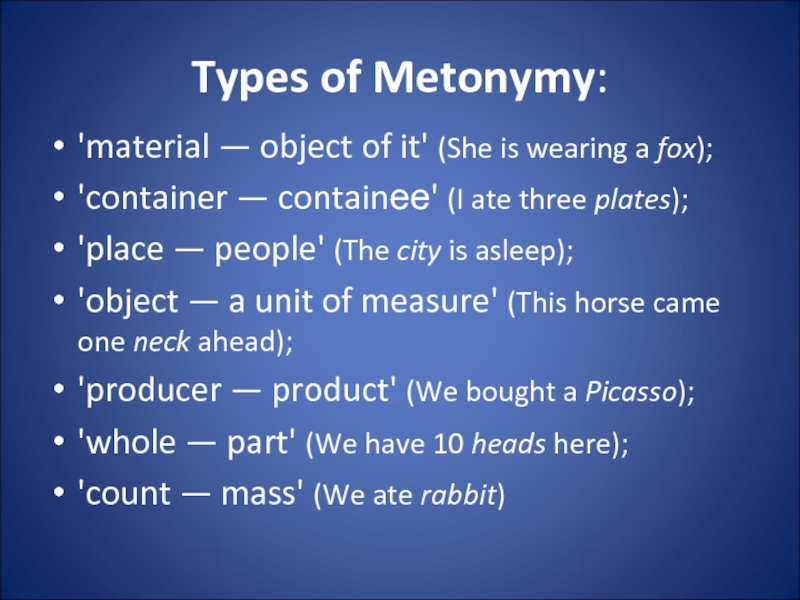

Слайд 67Types of Metonymy:

‘material — object of it’

(She is wearing a fox);

‘container — containее’

(I ate three plates);

‘place — people’ (The city is asleep);

‘object — a unit of measure’ (This horse came one neck ahead);

‘producer — product’ (We bought a Picasso);

‘whole — part’ (We have 10 heads here);

‘count — mass’ (We ate rabbit)

Слайд 68Results of Semantic Change:

changes in the denotational

component

changes in the connotational meaning

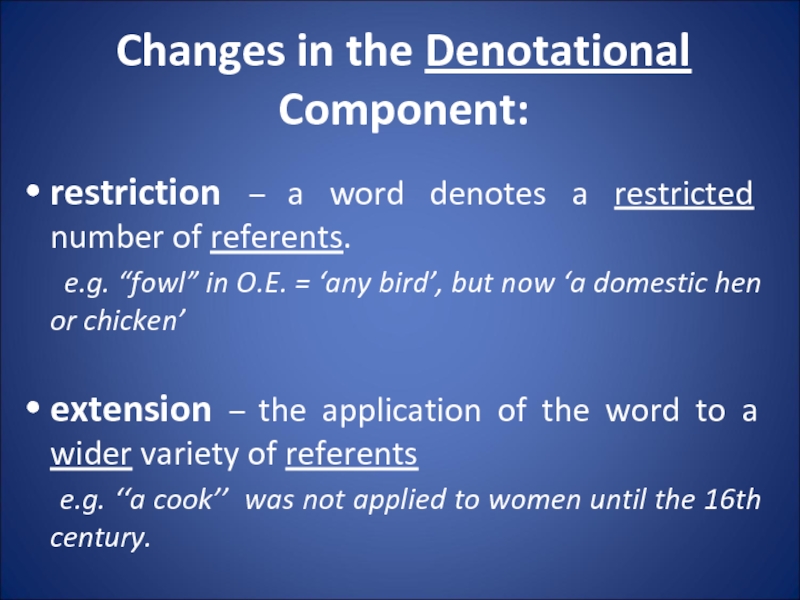

Слайд 69Changes in the Denotational Component:

restriction – a

word denotes a restricted number of referents.

e.g. “fowl” in O.E. = ‘any bird’, but now ‘a domestic hen or chicken’

extension – the application of the word to a wider variety of referents

e.g. ‘‘a cook’’ was not applied to women until the 16th century.

Слайд 70

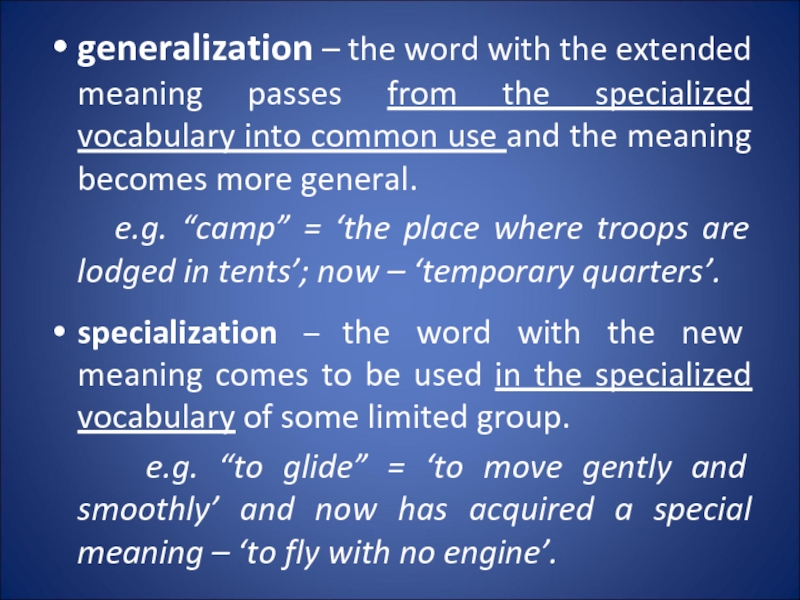

generalization – the word with the extended

meaning passes from the specialized vocabulary into

common use and the meaning becomes more general.

e.g. “camp” = ‘the place where troops are lodged in tents’; now – ‘temporary quarters’.

specialization – the word with the new meaning comes to be used in the specialized vocabulary of some limited group.

e.g. “to glide” = ‘to move gently and smoothly’ and now has acquired a special meaning – ‘to fly with no engine’.

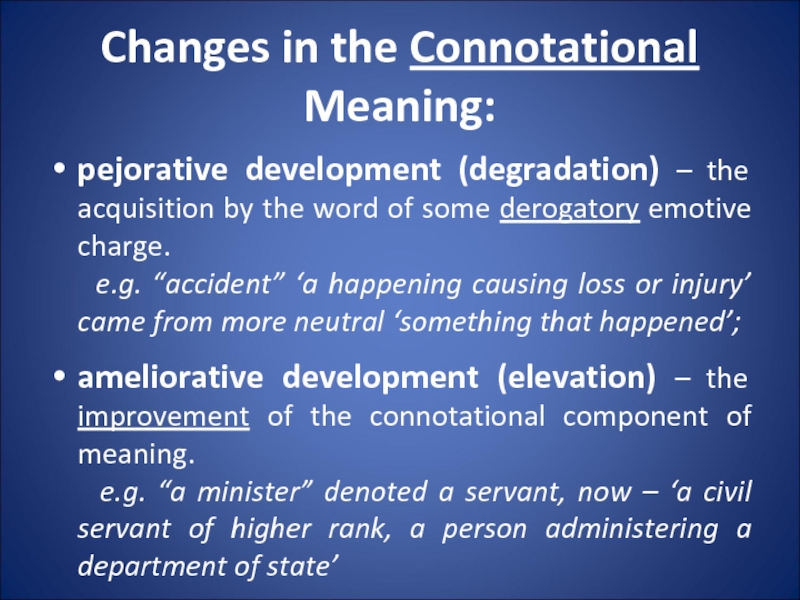

Слайд 71Changes in the Connotational Meaning:

pejorative development (degradation)

– the acquisition by the word of

some derogatory emotive charge.

e.g. “accident” ‘a happening causing loss or injury’ came from more neutral ‘something that happened’;

ameliorative development (elevation) – the improvement of the connotational component of meaning.

e.g. “a minister” denoted a servant, now – ‘a civil servant of higher rank, a person administering a department of state’

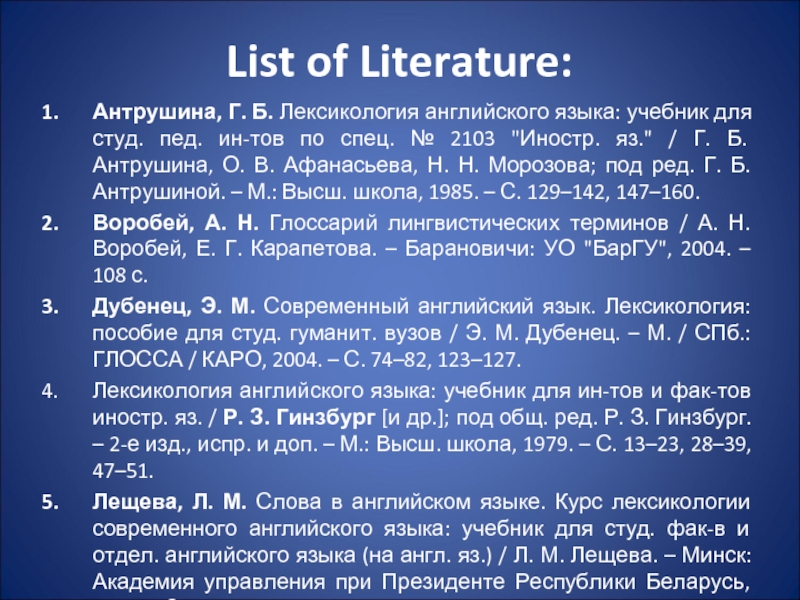

Слайд 72List of Literature:

Антрушина, Г. Б. Лексикология английского

языка: учебник для студ. пед. ин-тов по

спец. № 2103 «Иностр. яз.» / Г. Б. Антрушина, О. В. Афанасьева, Н. Н. Морозова; под ред. Г. Б. Антрушиной. – М.: Высш. школа, 1985. – С. 129–142, 147–160.

Воробей, А. Н. Глоссарий лингвистических терминов / А. Н. Воробей, Е. Г. Карапетова. – Барановичи: УО «БарГУ», 2004. – 108 с.

Дубенец, Э. М. Современный английский язык. Лексикология: пособие для студ. гуманит. вузов / Э. М. Дубенец. – М. / СПб.: ГЛОССА / КАРО, 2004. – С. 74–82, 123–127.

Лексикология английского языка: учебник для ин-тов и фак-тов иностр. яз. / Р. З. Гинзбург [и др.]; под общ. ред. Р. З. Гинзбург. – 2-е изд., испр. и доп. – М.: Высш. школа, 1979. – С. 13–23, 28–39, 47–51.

Лещева, Л. М. Слова в английском языке. Курс лексикологии современного английского языка: учебник для студ. фак-в и отдел. английского языка (на англ. яз.) / Л. М. Лещева. – Минск: Академия управления при Президенте Республики Беларусь, 2001. – С. 36–56.

Contents

Reference

Introduction

1. Word Meaning

1.1 Different Approaches to Meaning. Functional Approach

1.1.1 Referential approach

1.2 Types of Meaning. Grammatical Meaning

1.2.1 Lexical Meaning

1.2.2 Denotational and Connotational Meaning

1.3 Semantic Structure of polysemantic words

1.4 Types of Semantic Components

2. The meaning and Polysemy

2.1 Two approaches to the study of polysemy

2.1.1 Synchronic and Diachronic

2.2 Meaning and Context

2.3 The Lexical context

2.4 Grammatical Context

2.5 The development of new meanings of polysemantic words

Conclusion

Appendix to the course paper

Bibliography

Reference

The theme of the course paper is polysemy. The work consists of introduction where the choice of the theme is substantiated and the aim of the work with its dismemberment for intercommunicated complex of tasks are defined which are subject to decision for opening of the theme. There are two chapters in the main part. It observes the word meaning, the word — the basic unit of language which unites the form and the meaning. Also it contains approaches to meaning: the functional approach supports that a linguistic study of meaning is the investigation of the relation of sign to sign only; the referential approach seeks to formulate the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words and things or concepts they denote. Types of the meaning: grammatical, lexical, connotational and denotational meanings. Grammatical meaning is the element of plurality, tense endings, possessive case and so on. Lexical meaning is the same semantic component which several words have. Connotational and denotational meaning — the lexical meaning is not homogeneous either and may be analysed as including denotational that component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible and connotational component which consist of emotive charge that is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms a part of the connotational component of meaning and stylistic reference.part of all words consists of specified words, which are connected with science, technical, medical terms etc. — they have only one meaning. But the rest of the words have two or more meanings. The choice of the necessary word in a sentence depends on the context. Also there are grammatical and lexical contexts which are considered. The object of researching is the word, its meanings, context and developing of polysemantic words meanings. The aim of the work is to investigate word meanings in speech, the role of context for solution of polysemy in the text and to prove the importance of word meaning and its researching.

polysemy english language polysemantic

Polysemy decorates the speech, literature texts, but complicates a task for foreigners, who study another language, in our case, the English language, a task of translation. A context in this situation gives a lot, it helps to understand what the sentence, the text means in order to make professional translation in a literal way. It is all about the second chapter.the paper contains the conclusion where theoretical and practical conclusions are given in account in logical succession; and appendix.

Introduction

Do you need a dog?», asked Tom holding a puppy in his hands. No, answered John- I have, and, not turning around lifted the arm with a dog in it, a tool for getting tacks out of the wood.

There are plenty of languages in the world. There are a lot of words in the language, and almost every (except scientific) word has 2 and more meanings. And at the same time context appeared. Because only with help of the context we know which of the meanings is more suitable in that situation or text where we are or have. That is why it is necessary to study the polysemy and more important to know so many meanings of one word as it is possible.definition Lexicology deals with words, word — forming morphemes (derivational affixes) and word-groups or phrases. All these linguistic units may be said to have meaning of some kind: they are all significant and therefore must be investigated both as to form and meaning. The branch of lexicology that is devoted to the study of meaning is known as Semasiology. Words, however, play such a crucial part in the structure of language that when we speak of Semasiology without any qualification, we usually refer to the study of word-meaning proper, although it is in fact very common to explore the semantics of other elements, such as suffixes, prefixes, etc.is one of the most controversial terms in the theory of language. At first sight the understanding of this term seems to present no difficulty at all — it is freely used in teaching, interpreting and translation. The scientific definition of meaning however just as the definition of some other basic linguistic terms, such as word, sentence, etc., has been the issue of interminable discussions. Since there is no universally accepted definition of meaning we shall confine ourselves to a brief survey of the problem as it is viewed in modern linguistics both in our country and elsewhere.

1. Word Meaning

Word meaning. If is it necessary to discuss the meaning, first of all we must say some words about the word. What is this?

The word may be described as the basic unit of language. Uniting meaning and form, it is composed of one or more morphemes, each consisting of one or more spoken sounds or their written representation. The combinations of morphemes within words are subject to certain linking conditions.definition of a word is one of the most difficult in linguistics because the simplest word has many aspects. All attempts to characterize the word are necessarily specific for each domain of science and are therefore considered one-sided by the representatives of all the other domains and criticized for incompleteness. The variants of definitions were so numerous that some authors collecting them produced works of impressive scope and bulk.Hobbes (1588-1679), one of the great English philosophers, revealed a materialistic approach to the problem of nomination when he wrote that words are not mere sounds but names of matter. Three centuries later the great Russian physiologist I. P. Pavlov (1849-1936) examined the word in connection with his studies of the second signal system, and defined it as a universal signal that can be substitute any other signal from the environment in evoking a response in a human organism.runs as follows: a word is a sequence of graphemes which can occur between spaces, or the representation of such a sequence on morphemic level.semantic-phonological approach may be illustrated by A. H. Gardiners definition:

A word is an articulate sound-symbol in its aspect of denoting something which is spoken about. eminent French linguist A. Meillet combines the semantic, phonological and grammatical criteria and gives the following definition of the word:

A word is defined by the association of a particular meaning with a particular group of sounds capable of a particular grammatical employment.

Still, the main point can be summarized:

The word is the fundamental unit of language. It is a dialectal unity of form and content.

The linguistic science at present is not able to put forward a definition of meaning which is conclusive. However, there are certain facts of which we can be reasonably sure, and one of them is that the very function of the word as a unit of communication is made possible by its possessing a meaning. Therefore, among the word’s various characteristics, meaning is certainly the most important.speaking, meaning can be more or less described as a component of the word through which a concept (mental phenomena) is communicated. Meaning endows the word with the ability of denoting real objects, qualities, actions and abstract notions. The relationships between referent» (object, etc. denoted by the word), concept and word» are traditionally represented by the following triangle:

By the «symbol» here is meant the word; thought or reference is concept. The dotted line suggests that there is no immediate relation between word» and referent: it is established only through the concept. /Antrushina English Lexicology p.130/the other hand, there is a hypothesis that concepts can only find their realization through words. It seems that thought is dormant till the word wakens it up. It is only when we hear a spoken word or read a printed word that the corresponding concept springs into mind. The mechanism by which concepts (i. e. mental phenomena) are converted into words (i. e. linguistic phenomena) and the reverse process by which a heard or a printed word is converted into a kind of mental picture are not yet understood or described.branch of linguistics which specializes in the study of meaning is called semantics. As with many terms, the term «semantics» is ambiguous for it can stand, as well, for the expressive aspect of language in general and for the meaning of one particular word in all its varied aspects and nuances (i. e. the semantics of a word = the meaning (s) of a word).unit which most people would think of as one word may carry a number of meanings, by association with certain contexts. Thus pipe can be any tubular object, a musical instrument or a piece of apparatus for smoking; a hand can be on a clock or watch as well as at the end of the arm. Multiple meaning or polysemy is of considerable linguistic importance, and the process of extension is a concern of historical linguistics. Most of the time, we are able to distinguish the intended meaning by the usual process of mental adjustment to context and register: we dont expect to find tobacco pipes in the school recorder band. The literary language, however, again refuses to give us comfortable divisions of meaning beyond which imagination need not stray. It often forces us to accept polysemy not as a feature from which we select but as one in which we meet the writers intention without restriction.writer may indeed call in the aid of context to distinguish the meanings of polysemantic words; but his intention is not necessarily to elucidate a single meaning but rather to emphasize the uncertainties of daily usage and to point from this to an ironical comment on the human predicament.may allow a writer to work on two levels concurrently, apparently relating one set of events while really indicating something different. We move here towards metaphor, which must be a separate concern, but it is interesting to see how a chosen image can be maintained by word-choice appropriate to the register in which we should normally expect to find it, while the metaphorical relation to hidden meaning is deferred. For example, George Herbert sustains the image of God as the landlord in the poem Redemption by use of legal terms which are in perfect register-agreement with the opening statement:been tenant long to a rich Lordthriving, I resolved to be bold,make a suite into him, to affordnew small-rented lease, and cancel tholdheaven at his manor I him sought:told me there that he was lately gonesome land, which he had dearly boughtsince on earth, to take possession.writer may not confine himself to any normal register but rather create his own by choices that would seem odd or questionable in that context in everyday use. It is useful, though without attempting to draw any impassable line, to distinguish between two ways in which a writers selection of a single word may seem admirable. We will assume that there is no syntagmatic deviation and that the choice is paradigmatic within a context that is free from apparent ambiguity. Of course, the associations and figurative applications of words may still operate even when there is no obvious polysemy.the first way, there is no deviation; the achievement is in tackling the problem of synonymous words. It may well be argued that there are no perfect synonyms, since choice must be conditioned by register, dialect and emotive association. However, the problem of word-selection is difficult and is not much aided by the brief definitions of a dictionary or the listings of a thesaurus. One of the most effective ways of finding out what a word means in current usage is by asking people whether they would readily use it in a given sentence.

1.1 Different Approaches to Meaning. Functional Approach

functional approach supports that a linguistic study of meaning is the investigation of the relation of sign to sign only. In other words, they hold the view that the meaning of a linguistic unit may be studied only through its relation to other linguistic units and not thorough its relation to either concept or referent. The meaning of the words move and movement is different because they function in speech differently.comparing the contexts in which we find these words we cannot fail to observe that they hold different positions in relation to other words. (To) move, e. g., can be succeed by a noun (move the chair) preceded by a pronoun (we move). The position occupied by the word movement is different: it may be followed by a preposition (movement of smth.) preceded by an adjective (slow movement) and so on. As the distribution of the two words is different, we are entitled to the conclusion that not only do they belong to different classes of words, but that their meanings are different too. /R. S. Ginsburg p.28/, meaning may be scanned as the function of distribution. It follows that in the functional approach (1) semantic investigation is confined to the analysis of the difference or sameness of meaning; (2) meaning is understood essentially as the function or the use of linguistic signs. As a matter of fact, this line of semantic investigation is the primary concern, implied or expressed, of all structural linguists.

1.1.1 Referential approach

The referential approach seeks to formulate the essence of meaning by establishing the interdependence between words and things or concepts they denote.essential feature of this approach is that it distinguishes between the three components closely connected with meaning: the sound-form, and the actual referent, i. e. that part or that aspect of reality to which the linguistic sign refers. The best known referential model of meaning is the so-called basic triangle (as it was mentioned above) which, with some variations, underlies the semantic systems of all the adherents of this school of thought. In a simplified form the triangle may be represented as shown above, second page, the concept is on the top of the triangle, sound-form [d v] is the left corner and referent is the right corner. As can be seen from the diagram the sound-form of the linguistic sign, e. g. [d v], is connected with our concept of the bird which it denotes and through it with the referent, i. e. the actual bird. The common feature of any referential approach is the implication that meaning is in some form or other connected with the referent.

1.2 Types of Meaning. Grammatical Meaning

We notice, e. g., that words-forms, such as girls, winters, joys, tables, etc. though denoting widely different objects of reality have something in common. This common element is the grammatical meaning of plurality which can be found in all of them.grammatical meaning may be defined as the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, as, e. g., the tense meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girls, boys, nights etc).a broad sense it may be argued that linguists who make a distinction between lexical and grammatical meaning are in fact, making a distinction between the functional meaning which operates at various levels as the interrelation of various linguistic units and referential (conceptual) meaning as the interrelation of linguistic units and referents (or concepts).modern linguistic science it is commonly held that some elements of grammatical meaning can be identified by the position if the linguistic unit in relation to other linguistic units, i. e. by its distribution. Word-forms speaks, reads, writes have one and the same grammatical meaning as they can all be found in identical distribution, e. g. only after the pronouns he, she, it and before adverbs like well, badly, to-day etc. it follows that a certain component of the meaning of the word is described when you identify it as a part of speech, since different parts of speech are distributionally different.

1.2.1 Lexical Meaning

Comparing word-forms of one and the same word we observe that besides grammatical meaning, there is another component of meaning to be found in them. Unlike the grammatical meaning this component is identical in all the forms of the word thus e. g. the word-forms go, goes, went, going, gone possess different grammatical meanings of tense, person and so on, but in each of these forms we find one and the same semantic component denoting the process of movement. This is the lexical meaning of the word which may be described as the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, i. e. recurrent in all the forms of this word. /Ginsburg p.30/difference between the lexical and the grammatical components of meaning is not to be sought in the different of the concepts underlying the two types of meaning but rather in the way they are conveyed the concept of plurality, e. g., may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the world plurality, it may also be expressed in the forms of various words irrespective of their lexical meaning, e. g. boys, girls, balls, joys, etc. The concept of relation may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the word relation and also by any of the prepositions, e. g. in, on, behind, under, etc.follows that by lexical meaning we designate the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions, while by grammatical meaning we designate the meaning proper to sets of word-forms common to all words of a certain class. Both the lexical and the grammatical meaning make up the word-meaning as neither can exist without order.can be also observed in the semantic analysis of correlated words in different languages. E. g. the Russian word «сведения» is not semantically identical with the English equivalent information because unlike the Russian «сведения» the English word doesnt possess the grammatical meaning f plurality which is part of the semantic structure of the Russian word.

1.2.2 Denotational and Connotational Meaning

Lexical meaning is not homogenous and includes denotational and connotational components. The functions of words are to denote things, concepts and so on. Users of a language cannot have any knowledge or thought of the objects or phenomena of the real world around them unless this knowledge is ultimately embodied in words which have essentially the same meaning for all speakers of that language. This is the denotational meaning, i. e. that component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. There is no doubt that a physicist knows more about the atom than a singer does, or that a cooker possesses a much deeper knowledge of how to prepare for example shrimps than a person who cannot cook professionally. Nevertheless they use the words atom, shrimps, etc. and understand each other.second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component, i. e. the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word.charge is one of the objective semantic features proper to words as linguistic units and forms a part of the connotational component of meaning. The emotive charge varies in different word-classes. In some of them, in interjection, e. g., the emotive element prevails, whereas in conjunctions the emotive charge is as a rule practically non-existence.differ not only in their emotive charge but also in their stylistic reference and subdivided into literary, neutral and colloquial layers.greater part of the literary layer of Modern English vocabulary are words of general use, possessing no specific stylistic reference and known as neutral words. Against the background of neutral words we can distinguish two major subgroups — standard colloquial words and literary or bookish words. Parent, father, dad. In comparison with the word father which is stylistically neutral, dad stands out as colloquial and parent is felt as bookish. Or chum-friend, rot-nonsense, etc.

1.3 Semantic Structure of polysemantic words

It is generally known that most words convey several concepts and thus possess the corresponding number of meanings. A word having several meanings is called polysemantic, and the ability of words to have more than one meaning is described by the term polysemy.

Polysemy is certainly not an anomaly. Most English words are polysemantic. It should be noted that the wealth of expressive resources of a language largely depends on the degree to which polysemy has developed in the language. Sometimes people who are not very well informed in linguistic matters claim that a language is lacking in words if the need arises for the same word to be applied to several different phenomena. In actual fact, it is exactly the opposite: if each word is found to be capable of conveying at least two concepts instead of one, the expressive potential of the whole vocabulary increases twofold. Hence, a well-developed polysemy is a great advantage in a language.the other hand, it should be pointed out that the number of sound combinations that human speech organs can produce is limited. Therefore at a certain stage of language development the production of new words by morphological means is limited as well, and polysemy becomes increasingly important for enriching the vocabulary. From this, it should be clear that the process of enriching the vocabulary does not consist merely in adding new words to it, but, also, in the constant development of polysemy.system of meanings of any polysemantic word develops gradually, mostly over the centuries, as more and more new meanings are added to old ones, or oust some of them. So the complicated processes of polysemy development involve both the appearance of new meanings and the loss of old ones. Yet, the general tendency with English vocabulary at the modern stage of its history is to increase the total number of its meanings and in this way to provide for a quantitative and qualitative growth of the language’s expressive resources.analysing the semantic structure of a polysemantic word, it is necessary to distinguish between two levels of analysis. On the first level, the semantic structure of a word is treated as a system of meanings. For example, the semantic structure of the noun fire» could be roughly presented by this scheme (only the most frequent meanings are given):

I

The above scheme suggests that meaning (I) holds a kind of dominance over the other meanings conveying the concept in the most general way whereas meanings (II) — (V) are associated with special circumstances, aspects and instances of the same phenomenon.(I) (generally referred to as the main meaning) presents the centre of the semantic structure of the word holding it together. It is mainly through meaning (I) that meanings (II) — (V) (they are called secondary meanings) can be associated with one another, some of them exclusively through meaning (I) — the main meaning, as, for instance, meanings (IV) and (V).

It would hardly be possible to establish any logical associations between some of the meanings of the noun bar except through the main meaning:

Bar, n

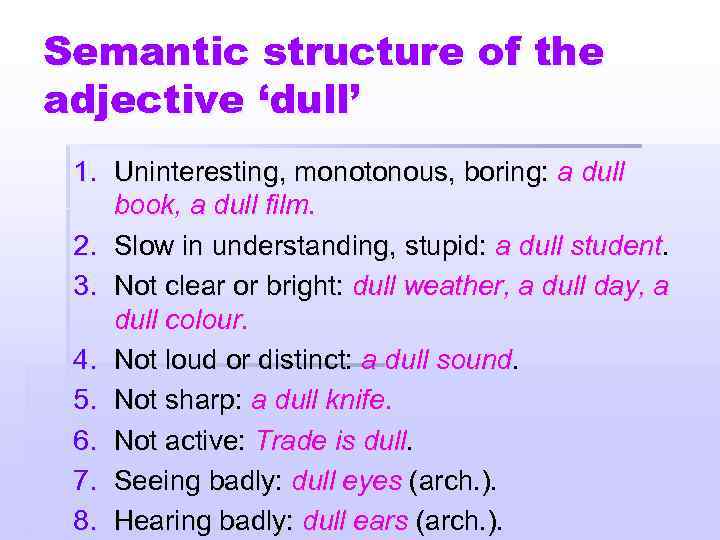

Meaning’s (II) and (III) have no logical links with one another whereas each separately is easily associated with meaning (I): meaning (II) through the traditional barrier dividing a court-room into two parts; meaning (III) through the counter serving as a kind of barrier between the customers of a pub and the barman., it is not in every polysemantic word that such a centre can be found. Some semantic structures are arranged on a different principle. In the following list of meanings of the adjective dull» one can hardly hope to find a generalized meaning covering and holding together the rest of the semantic structure., adj.

- A dull book, a dull film — uninteresting, monotonous, boring.

- A dull student — slow in understanding, stupid.

- Dull weather, a dull day, a dull colour — not clear or bright.

- A dull sound — not loud or distinct.

- A dull knife — not sharp.

- Trade is dull — not active.

- Dull eyes (arch.) — seeing badly.

- Dull ears (arch.) — hearing badly.

There is something that all these seemingly miscellaneous meanings have in common, and that is the implication of deficiency, be it of colour (m. III), wits (m. II), interest (m. I), sharpness (m. V), etc. The implication of insufficient quality, of something lacking, can be clearly distinguished in each separate meaning., adj.

- Uninteresting — deficient in interest or excitement.

- . Stupid — deficient in intellect.

- Not bright — deficient in light or colour.

- Not loud — deficient in sound.

- Not sharp — deficient in sharpness.

- Not active — deficient in activity.

- Seeing badly — deficient in eyesight.

- Hearing badly — deficient in hearing.

The transformed scheme of the semantic structure of dull» clearly shows that the centre holding together the complex semantic structure of this word is not one of the meanings but a certain component that can be easily singled out within each separate meaning.the second level of analysis of the semantic structure of a word: each separate meaning is a subject to structural analysis in which it may be represented as sets of semantic components.scheme of the semantic structure of dull» shows that the semantic structure of a word is not a mere system of meanings, for each separate meaning is subject to further subdivision and possesses an inner structure of its own., the semantic structure of a word should be investigated at both these levels:

) of different meanings,

) of semantic components within each separate meaning. For a monosemantic word (i. e. a word with one meaning) the first level is naturally excluded.

1.4 Types of Semantic Components

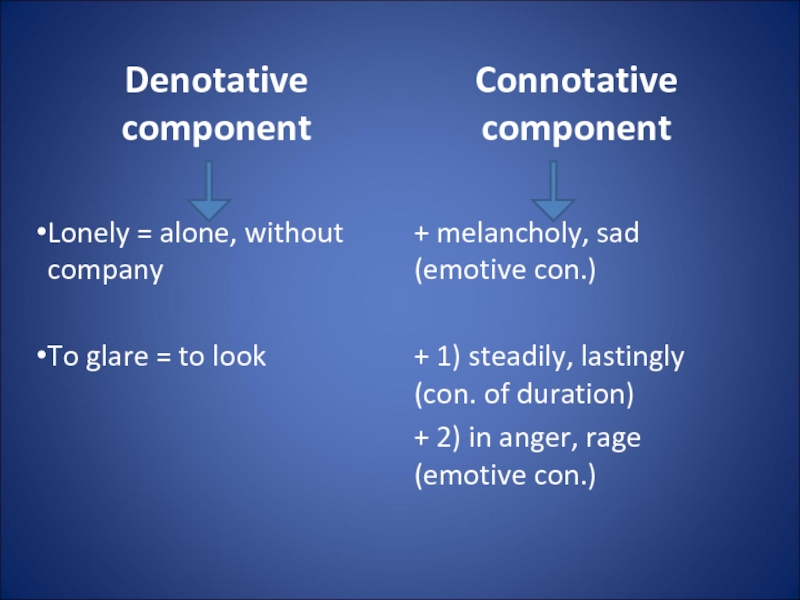

The leading semantic component in the semantic structure of a word is usually termed denotative component (also, the term referential component may be used). The denotative component expresses the conceptual content of a word.following list presents denotative components of some English adjectives and verbs:

Denotative components

lonely, adj. — alone, without company …, adj. — widely known, adj. — widely knownglare, v. — to lookglance, v. — to lookshiver, v. — to trembleshudder, v. — to trembleis quite obvious that the definitions given in the right column only partially and incompletely describe the meanings of their corresponding words. They do not give a more or less full picture of the meaning of a word. To do it, it is necessary to include in the scheme of analysis additional semantic components which are termed connotations or connotative components.

The above examples show how by singling out denotative and connotative components one can get a sufficiently clear picture of what the word really means. The schemes presenting the semantic structures of glare, shiver, shudder also show that a meaning can have two or more connotative components.given examples do not exhaust all the types of connotations but present only a few: emotive, evaluative connotations, and also connotations of duration and of cause.

2. The meaning and Polysemy

We became more profound in studying of meaning. We discussed the concept of meaning, different types of word-meanings and the changes they undergo in the course of the historic development of the English language. Analysing the semantic structure of the word we can see that words as the rule dont have only single meaning. They are called monosemantic words, i. e. words have only one meaning are few in their amount, they are from science, scientific terms. But all the rest of English words are polysemantic, it means they dont have only one single meaning, they possess more than one meaning. The real number of meanings of the commonly used words ranges from five to about a hundred. In fact, the commoner the word the more meanings it has.word polysemy» means plurality of meanings it exists only in the language, not in speech.meanings of a polysemantic word may come together due to the proximity of notions which they express. E. g. the word blanket has the following meanings: a woolen covering used on beds, a covering for keeping a horse warm, a covering of any kind /a blanket of snow/, covering all or most cases /used attributively/, e. g. we can say a blanket insurance policy.are some words in the language which are monosemantic, such as most terms, /synonym, molecule, bronchitis/, some pronouns /this, my, both/, numerals.are two processes of the semantic development of a word: radiation and concatenation. In cases of radiation the primary meaning stands in the centre and the secondary meanings proceed out of it like rays. Each secondary meaning can be traced to the primary meaning. E. g. in the word face» the primary meaning denotes the front part of the human head Connected with the front position the meanings: the front part of a watch, the front part of a building, the front part of a playing card were formed. Connected with the word face» itself the meanings: expression of the face, outward appearance are formed.cases of concatenation secondary meanings of a word develop like a chain. In such cases it is difficult to trace some meanings to the primary one. E. g. in the word crust the primary meaning hard outer part of bread» developed a secondary meaning hard part of anything /a pie, a cake/, then the meaning harder layer over soft snow was developed, then a sullen gloomy person, then impudence were developed. Here the last meanings have nothing to do with the primary ones. In such cases homonyms appear in the language. It is called the split of polysemy.most cases in the semantic development of a word both ways of semantic development are combined.

.1 Two approaches to the study of polysemy

2.1.1 Synchronic and Diachronic

There are two principle approaches in linguistic science to the study of language material: synchronic & diachronic. With regard to Special lexicology the synchronic approach is concerned with the vocabulary of a language as it exists at a given time. Its Special Descriptive lexicology that deals with the vocabulary & vocabulary units of a particular language at a certain time.diachronic approach in terms of Special lexicology deals with the changes in the development of vocabulary in the coarse of time. It is Special Historical lexicology that deals with the evaluation of the vocabulary units of a language as the time goes by.two approaches shouldnt be set one against the other. In fact, they are interconnected & interrelated because every linguistic structure & system exists in a state of constant development so that the synchronic state of a language system is a result of a long process of linguistic evaluation, of its historical development. Closely connected with the Historical lexicology is Contrastive & Comparative lexicology whose aims are to study the correlation between the vocabularies of two or more languages & find out the correspondences between the vocabulary units of the languages under comparison. Lexicology studies various lexical units. They are: morphemes, words, variable word-groups & phraseological units. We proceed from the assumption that the word is the basic unit of the language system, the largest on morphological & the smallest on syntactic plane of linguistic analyses. The word is a structural & semantic entity within the language system. The word as well as any linguistic sign is a two-faced unit possessing both form & content or, to be more exact, sound-form & meaning.. g. boy — бой

When used in actual speech the word undergoes certain modification & functions in one of its forms. The system showing a word in all its word-forms is called a paradigm. The lexical meaning of a word is the same throughout the paradigm. The grammatical meaning varies from one form to another. Therefore when we speak on any word as used in actual speech we use the term word» conventionally because what is manifested in the utterances is not a word as a whole but one of its forms which is identified as belonging to the definite paradigm. Words as a whole are to be found in the dictionary (showing the paradigm n — noun, v — verb, etc). There are two approaches to the paradigm: as a system of forms of one word revealing the differences & the relationships between them.

e. g. to see — saw — seen — seeing

( different forms have different relations )

In abstraction from concrete words the paradigm is treated as a pattern on which every word of one part of speech models its forms, thus serving to distinguish one part of speech from another.

-s —s -s -ed -ing

nouns, of-phrases verbs

the grammatical forms of words there are lexical varieties which are called variants» of words. Words seldom possess only one meaning, but used in speech each word reveals only that meaning which is required.. g. to learn at school to make a dresslearn about smth. ?smbd. to make smbd. do smth.are lexico-semantic variants.are also phonetic & morphological variants.. g. often can be pronounced in two ways, though the sound-form is slightly changed, the meaning remains unchangeable. We can build the forms of the word to dream» in different ways:dream — dreamt — dreamt

dreamed-dreamedare morphological variants. The meaning is the same but the model is different.

Like words-forms variants of words are identified in the process of communication as making up one & the same word. Thus, within the language system the word exists as a system & unity of all its forms & variants.

2.2 Meaning and Context

Its important that there is sometimes a chance of misunderstanding when a polysemantic word is used in a certain meaning but accepted by a listener or reader in another.is common knowledge that context prevents from any misunderstanding of meanings. For instance, the adjective dull, if used out of context, would mean different things to different people or nothing at all. It is only in combination with other words that it reveals its actual meaning: a dull pupil, a dull play, dull weather, etc. Sometimes, however, such a minimum context fails to reveal the meaning of the word, and it may be correctly interpreted only through a second-degree context as in the following example: The man was large, but his wife was even fatter. The word fatter» here serves as a kind of indicator pointing that large describes a stout man and not a big one.research in semantics is largely based on the assumption that one of the more promising methods of investigating the semantic structure of a word is by studying the word’s linear relationships with other words in typical contexts, i. e. its combinability or collocability.

Scholars have established that the semantics of words which regularly appear in common contexts are correlated and, therefore, one of the words within such a pair can be studied through the other.are so intimately correlated that each of them casts, as it were, a kind of permanent reflection on the meaning of its neighbor. If the verb to compose» is frequently used with the object music, so it is natural to expect that certain musical associations linger in the meaning of the verb to composed., also, how closely the negative evaluative connotation of the adjective notorious is linked with the negative connotation of the nouns with which it is regularly associated: a notorious criminal, thief, gangster», gambler, gossip, liar, miser, etc.this leads us to the conclusion that context is a good and reliable key to the meaning of the word.s a common error to see a different meaning in every new set of combinations. For instance: an angry man, an angry letter. Is the adjective angry used in the same meaning in both these contexts or in two different meanings? Some people will say «two» and argue that, on the one hand, the combinability is different (man» — -name of person; letter» — name of object) and, on the other hand, a letter cannot experience anger. True, it cannot; but it can very well convey the anger of the person who wrote it. As to the combinability, the main point is that a word can realize the same meaning in different sets of combinability. For instance, in the pairs merry children, merry laughter, merry faces, merry songs» the adjective merry conveys the same concept of high spirits.task of distinguishing between the different meanings of a word and the different variations of combinability is actually a question of singling out the different denotations within the semantic structure of the word.

1) a sad woman,

2) a sad voice,

3) a sad story,

4) a sad scoundrel (= an incorrigible scoundrel)

5) a sad night (= a dark, black night, arch. poet.)the first three contexts have the common denotation of sorrow whereas in the fourth and fifth contexts the denotations are different. So, in these five contexts we can identify three meanings of sad.

2.3 The Lexical context

In lexical contexts of primary importance are the lexical groups combined with the polysemantic word under consideration. This can be shown by analysing different lexical contexts in which polysemantic words, e. g. heavy or come, are used. The adjective heavy in isolation is understood as meaning of great weight, weighty (heavy cargo, heavy book, etc.). When combined with the lexical group of words denoting natural phenomena such as wind, storm, snow, etc., it means striking, falling with force, abundant as can be seen from the contexts, e. g. heavy rain, wind, snow etc. In combination with the words industry, arms, artillery and the like, heavy has the meaning the larger kind of something as in heavy artillery, etc.word come in isolation has primarily the meaning to arrive, move toward, etc. When we join it the lexical group of prepositions we have more meanings we can imagine, even one preposition, for example in, and we have nine meanings; come in: a) to enter, b) sport to get finish, c) to become fashionable, d) to be found as useful, etc. it acquires the meaning synonymous with the meaning of the verb to be found (to be found somewhere, at finish, in fashion, as useful etc.).can be easily observed that the main factor in bringing out this or that individual meaning of the words heavy and to come is the lexical group with which the word in question is combined.meanings determined by lexical contexts are sometimes referred to as lexically bound meanings which implies that such meanings are to be found only in certain lexical contexts. / Ginsburg p.56/

2.4 Grammatical Context

In grammatical contexts it is the grammatical structure of the context that serves to determine various individual meanings of a polysemantic word. One of the meanings of the verb make, e. g. to force, is found only in the grammatical context possessing the structure to make smb to do smth or in simpler terms this particular meaning occurs only if the verb make is followed by a noun and the infinitive of some other verb (to make smb laugh, go, write, etc.). Another meaning of this verb to become, to turn out to be is observed in the contexts of a different structure, e. g. make followed by an adjective and a noun (to make a good wife, a good teacher, etc.).a number of contexts, however, we find that both the lexical and grammatical aspects should be taken into consideration. The grammatical structure of the context although indicative of the difference between the meaning of the word in this structure and the meaning of the same word in a different grammatical structure may be insufficient to indicate in which of its individual meaning of the word in question is used. If we compare the contexts of different grammatical structures, e. g. to take+noun and to take to+noun, we can safely assume that they represent different meanings of the verb to take, but it is only when we specify the lexical context, i. e. the lexical group with which the verb is combined in the structure to take+noun (to take tea; books; the bus) that we can say that the context determines the meaning. /Ginsburg p.57/

2.5 The development of new meanings of polysemantic words

The systems of meanings of polysemantic words evolve gradually. The older a word is, the better developed is its semantic structure. The normal pattern of a words semantic development is from monosemy to a simple semantic structure encompassing only two or three meanings, with a further movement to an increasingly more complex semantic structure.are two causes of development of new meanings. First is the historical one: different kinds of changes in a nations social life, in its culture, knowledge, technology, arts lead to gaps appearing in the vocabulary which beg to be filled. Newly created objects, new concepts and phenomena must be named: word-building and borrowing foreign ones. New meanings can also be developed due to linguistic factors — the second cause. Linguistically speaking, the development of new meanings, and also a complete change of meaning, may be caused through the influence of other words, mostly of synonyms.process of development of a new meaning (or a change of meaning) is traditionally termed transference. Some scholars mistakenly use the term transference of meaning» which is a serious mistake. It is very important to note that in any case of semantic change it is not the meaning but the word that is being transferred from one referent into another (from a horse-drawn vehicle into a railway car). The result of such a transference is the appearance of new meaning.are two types of transference based on resemblance and contiguity.type of transference is also referred to as linguistic metaphor. A new meaning appears as a result of associating two objects (phenomena, qualities, etc) due to their outward similarity. The noun eye, for instance, has for one of its meanings hole in the end of a needle which also developed through transference based on resemblance.meanings formed through this type of transference are frequently found in the informal strata of the vocabulary, especially in slang. A red-headed boy is almost certain to be nicknamed carrot or ginner by his schoolmates, and the one who is given to spying and sneaking gets the derogatory nickname of rat. Both these meanings are metaphorical, though, of course, the children using them are quite unconscious of this fact.type is linguistic metonymy. The association is based upon subtle psychological links between different objects and phenomena, sometimes traced and identified with much difficulty. The two objects may be associated together because they often appear in common situations, and so the image of one is easily accompanied by the image of the other; or they may be associated on the principle of cause and effect, of common function, of some material and an object which is made of it, etc. The Old English adjective glad meant bright, shining» (it was applied to the sun, to gold and precious stones, to shining armour, etc.). the later (and more modern) meaning joyful» developed on the basis of the usual association (which is reflected in most languages) of light with joy.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of polysemy exists not in the speech but in the language.problem of polysemy is mainly the problem of interrelation and interdependence of the various meanings of the same word. Polysemy viewed diachronically is a historical change in the semantic structure of the word resulting in new meanings being added to the ones already existing and in the rearrangement of these meanings on its semantic structure.viewed synchronically is understood as coexistence of the various meanings of the same word at a certain historical period and the arrangement of these meanings in the semantic structure of the word.the present work there was viewed polysemy, meaning of the word, some words about the notion word, because it is really very important to know what the word is. It is impossible to speak about the role of the meaning without understanding the word, the basic unit of language that unites meaning and form. The context was observed. Attention should be paid to it.is a sentence, it must be translated, for example from English to Russian, theoretically if that who translates is not a professional translator it is not necessary to know the types of context, and in general and to professional translator too. During the whole studying a student is taught by teachers to understand the sentence and then to translate it with the contexts help. He chooses the necessary meaning intuitively. But the observing context types explains a lot, for example the choice of the necessary meaning. Sometimes you dont know all the meanings of translated word, and…you guess by context. Context is the minimal stretch of speech necessary to find out individual meanings. Linguistic contexts comprise lexical and grammatical contexts and are contrasted to extra-linguistic contexts. In extra-linguistic contexts the meaning of the experiment is determined not only by linguistic factor but also by the actual situation in which the word is used.most interesting moment is the development of new meanings of polysemantic words, the causes and the process.meaning incurs to alter in the course of the historical development of language. Changes of lexical meaning may be viewed by a diachronic semantic analysis of many commonly used English words.the origins of semantic altering one may distill on the factors bringing about this change and try to discover why the word altered its meaning. Analysing the nature of semantic change one may search for to clarify the process of this change and describe how diversified changes of meaning were brought about.is certainly not an anomaly. Most English words are polysemantic. It should be commented that the wealth of representative resources of a language largely depends on the extent to which polysemy has developed in the language.uninformed in linguistic people claim that a language is lacking in words if the need arises for the same word to be laid on to several different phenomena. In real fact it is exactly the opposite: if each word is found to be capable of conveying at least two concepts instead of one, the expressive potential of the whole vocabulary increases twofold. Hence, well-developed polysemy is a great advantage in a language.

Appendix to the course paper

Polysemy in the speech

I n 1) разрешение, позволение 2) отпуск 3) воен. увольнение 4) отъезд уход, прощание;

Leave II v 1) покидать 2) уезжать, переезжать 3) оставлять 4) покидать, бросать 5) оставлять после смерти (жену, детей и т.д.) 6) оставлять завещание, наследство 7) предоставлять

Leave III v покрываться листвой;

Mean I a 1) скупой, скаредный 2) низкий, подлый, нечестный 3) посредственный, скупой, слабый 4) убогий, бедный, жалкий 5) низкого происхождения 6) разг. придирчивый, недоброжелательный 7) амер. трудный, неподдающийся

Mean II 1. n 1) середина;

) мат. среднее число 2. а средний; mean line мат.

биссектриса; mean water нормальный уровень воды à in the mean time — тем временем; между тем;

Mean III v 1) намереваться; иметь ввиду; to mean business разг. а) браться (за что-л.) серьезно, решительно; б) говорить всерьез;

) думать, подразумевать;

) предназначаться;

) означать, предвещать;

значить, означать, иметь значение Context n 1) контекст 2) ситуация, связь, фон; обстановка.

Pink I 1. n 1) розовый цвет 2) бот. Гвоздика 3) (the pink) верх, высшая степень; in the pink — в прекрасном состоянии (о здоровье); the pink of perfection — верх совершенства 4) красный камзол охотника на лисицу 6) умеренный радикал;

2. а 1) розовый 2) либеральничающий;

Pink II v 1) протыкать, прокалывать 2) украшать дырочками, фестонами, зубцами;

Pink III v работать с детонацией (о двигателе);

Pink IV n молодой лосось Levee I n 1) ист. дневной прием при дворе с присутствием одних мужчин 2) ист. амер. прием (у главы у главы госуд.) 3) прием гостей Levee II амер.1. n 1) дамба, гать 2) набережная 3) пристань 4) береговой (намывной) вал реки 2. v воздвигать дамбы The choice of the necessary meaning depends on the context.

The darkness whirled and roared. I have lost something. It is gone. What was it? It was terribly important, I must remember it. He began to struggle, reaching for consciousness, and a long way off heard himself groan. — n темнота, мрак, тьма, неведение.

Whirl — v вертеться, кружиться, произноситься.

Roar — v реветь, орать, гудеть, рычать; храпеть (о больной лошади); прокричать, проорать.

Lose — v 1) терять, лишаться, утрачивать (свойство, качество) 2) упустить, не воспользоваться 3) проигрывать 4) пропустить, опоздать 5) вызывать потерю, стоить (чего-либо) лишать (чего-либо).

Go — v 1) идти, ходить, быть в движении 2) ехать, путешествовать 3) пролегать, тянуться 4) отправляться 5) уезжать, уходить 6) быть в действии, работать, ходить (о часах, механизме) 7) быть в обращении, переходить из уст в уста

) быть принятым, получить признание (о плане, проекте) 18) расходоваться, тратиться 19) переходить в собственность 20) рухнуть, сломаться 21) потерпеть крах 22) уничтожаться, отменяться 23) регулярно ходить в школу 24) быть присужденным 25) стать (кем-либо)

Terribly — внушающее, ужасно, страшно, громадно.

Important — важный, значительный, существенный, напыщенный, важничающий.

Remember — помнить, вспоминать, дарить, завещать, давать на чай, передавать привет.

Begin — начинать (ся), браться за что-либо, брать начало от чего-либо

Struggle — биться, отбиваться, бороться, делать усилия, стараться изо всех сил, пробиваться

Reach — протягивать, вытягивать, доставать, дотягиваться, доезжать до, достигать, доходить, трогать, оказывать влияние передавать, подавать, застать, настигнуть, простираться, составлять (сумму)

Hear — слышать, слушать, внимать, выслушивать, услышать (узнать), получить известие.

Groan — тяжелый вздох, стон, скрип, треск

Перевод.

Мрак кружился и гудел.» Я потерял что-то. Это ушло. Что это было? Это было ужасно важно. Я должен вспомнить это». Он старался изо всех сил вспомнить, ухватить сознание, но лишь вздох отчаяния пробился к его сознанию.

Bibliography

1.Арнольд И.В. «Лексикология современного английского языка»

2.Литвин А.А. «Многозначность в английском языке и речи»

3.R. S. Ginsburg A course in modern English Lexicology

4.Ворно Е.Ф., Кащеева М.А. «Лексикология английского языка

.Антрушина Г.Б. Лексикология английского языка»`

6.F. R. Palmer Semantics. A new outline

.John Lyons Language and linguistic

8.Дубенец Э.М. «Современный английский язык. Лексикология»

9.E. M. Mednikova Seminars in English Lexicology

.A.I. Smirnitskiy Lexicology of English Language

11.Berezin Lectures on Linguistics

.Александрова О.В. «Хрестоматия по английской филологии»

.Минаева «Слово в языке и речи»

.Сборник научных трудов. Выпуск 333. «Формальная и семантическая организация текста»

Теги:

Polysemy in english language

Диплом

Английский

Просмотров: 40682

Найти в Wikkipedia статьи с фразой: Polysemy in english language

Polysemous English words — Wall Street English. There are many English words that are pronounced and spelled exactly the same, but have completely different meanings. … But you get a double benefit, as marketers would say: several new English words at once to replenish the vocabulary for the price of one.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the English word with the most meanings is set. It has 430 values. Here we will look at common examples of the meanings of ambiguous English words.

What words in English have multiple meanings?

And in order to read articles in English on your own and not feel discomfort, come to study at Skyeng.

- Run: 645 values …

- Set: 430 values …

- Go: 368 values …

- Take: 343 values …

- Stand: 334 values …

- Get: 289 values …

- Turn: 288 values …

- Put: 268 values

Why does one word have many meanings in English?

The English language is notable for the fact that a large number of words are polysemous. The linguistic name for this phenomenon is ‘polysemy’: from the Greek words ‘poly’ — ‘many’ and ‘sema’ — ‘meaning’. This very polysemy leads to our mistakes, misunderstanding and misinterpretation. … Their different meanings do not surprise us at all.

What’s the longest word in the English language?

The longest word found in the main dictionaries of the English language is pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, which means lung disease from the inhalation of very small silica particles of volcanic ash; from a medical point of view, the disease is similar to that of silicosis.

What are unambiguous example words?

In modern Russian, there are words that have the same lexical meaning: bandage, appendicitis, birch, felt-tip pen, satin, etc. Such words are called unambiguous or monosemantic (gr.

What word in Russian has the most meanings?

Polysemous words can be among words belonging to any part of speech, except for numbers. Most polysemous words are observed among verbs. The word «go» can be called «champion» in terms of ambiguity. It has more than 40 meanings, and the verb «pull» has more than 20.

How to determine the meaning of a polysemantic word?

A word that has several lexical meanings is polysemantic. One meaning is direct, the rest are portable. A striking example of a polysemantic word is a key (spanner, treble, spring, key from the lock). Any independent part of speech can be polysemantic: a noun, an adjective, a verb, etc.

What are words with two meanings called?

Words that have two or more meanings are called polysemous. Words that answer the same question and have a similar meaning are called synonyms. Words that answer the same question, but have the opposite meaning, are called antonyms.

What are grade 2 polysemous words?

Polysemous words are words that have two or more lexical meanings. Explanatory dictionary — a dictionary that provides an explanation of the lexical meaning of a word.

Why are there so many synonyms in English?

Why are there so many synonyms in English?