Types of word-groups.

Words in English may be classified according to

different principles:

1) Word-groups

may be described according to the order & arrangement of the

component members, e.g.

to see a house, a cloud – is adverbial nominal group.

2) according to

the criterion of distribution, word-groups are: endocentric &

exocentric. The word-group which has the same linguistic distribution

as one of its members is called endocentric, e.g.

i saw a red flower = I saw a flower.

The word-group is called exocentric if the distribution of the

word-group is different from either of its members, e.g.

side-by-side.

3) according to

their head-word, word-group may be: nominal, adjectival, verbal,

adverbial & so on, e.g.

a pretty girl – nominal word-group; to work hard – verbal group.

4) according to

their syntactic pattern, word-groups are: predicative &

non-predicative. Predicative word-groups have Subject-predicative

relations between the component members, e.g.

John works.

Non-predicative word-groups are subdivided into, according to the

type of semantic relations between its components:

-

Subordinative (a redflower);

-

Coordinative (day & night — сутки).

5) word-groups

may be described according to the degree of motivation & the

degree of semantic & structural cohesion of members. The degree

of structural & semantic cohesion of word-groups may vary. The

component members of some word-group possess great semantic &

structural independence, e.g. the leg of

a chair. Their cooccurence is governed

by their vallency & collocability & the rules of logic. Such

word-groups are clearly motivated. Word-groups of this type are

defined as free or variable word-groups (переменные),

e.g. a smart girl, a tall boy,

etc. They are habitually studied in Syntax. Other word-groups are

less variable & they are _____ semi-motivated, e.g.

to take a look, to give a smile, a point of view, old chap.

Some others are functionally & semantically

inseparable & actually non-motivated, e.g.

red tape – бюрократия;

to take the bull by the horus.

Such words are called stable word-groups or set-phrases

(expressions), phraseological units. They are studied in Phraseology.

Соседние файлы в папке Lecture9

- #

- #

- #

LECTURE 12.

WORD-GROUPS AND PHRASEOLOGICAL UNITS

1. Lexical and Grammatical Valency

2. Structure and Classification of Word-Groups

3. Types of Meaning of Word-Groups

4. Motivation in Word-Groups

1. Lexical and grammatical valency

The aptness of a word to appear in various combinations is described as its lexical valency or collocability. The noun job, for example, is often combined with such adjectives as backbreaking, difficult, hard; full-time, part-time, summer, cushy, easy; demanding; menial, etc. The noun myth may be a component of a number of word-groups, e.g. to create a myth, to dispel a myth, to explode a myth, myths and legends, etc. Lexical valency acquires special importance in case of polysemy as through the lexical valency different meanings of a polysemantic word can be distinguished, for instance, cf.: heavy table (safe, luggage); heavy snow (rain, storm); heavy drinker (eater); heavy sleep (sorrow, disappointment); heavy industry (tanks).

The range of the lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock. Though the verbs lift and raise are usually treated as synonyms, it is only the latter that is collocated with the noun question.

The restrictions of lexical valency of words may also manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word groups. For example, the adjective heavy in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’ is combined with the words food, meals, supper. But it cannot be used with the words cheese or sausage (the words with more or less the same component of meaning) implying that the cheese or the sausage is difficult to digest.

Words habitually collocated in speech tend to constitute a cliche, for instance, the noun arms and the noun race. Thus, arms race is a cliche.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different, cf.: in English pot flowers – in Russian комнатные цветы.

Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. The minimal grammatical context in which words are used when brought together to form word-groups is usually described as the pattern of the word-groups. For instance, the verb to offer can be followed by the infinitive (to offer to do smth.) and the noun (to offer a cup of tea). The verb to suggest can be followed by the gerund (to suggest doing smth.) and the noun (to suggest an idea). The grammatical valency of these verbs is different.

The adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different grammatical valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern: adjective + preposition ‘at’ + noun (clever at mathematics), whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

The grammatical valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical, cf.: in English to influence a person, a decision, a choice (verb + noun) — in Russian влиять на человека, на решение, на выбор (verb + preposition + noun).

2. Structure and classification of word groups

The term ‘syntactic structure (formula)’ implies the description of the order and arrangement of member-words in word-groups as parts of speech. For instance, the syntactic structure of the word-groups a clever man, a red flower may be described as made up of an adjective and a noun, i.e. A + N; of the word-groups to take books, to build houses — as a verb and a noun, i.e. V + N.

The structure of word-groups may also be described in relation to the head-word. In this case it is usual to speak of the pattern but not of formulas. For example, the patterns of the verbal groups to take books, to build houses are to take + N, to build + N. The term ‘syntactic pattern’ implies the description of the structure of the word-group in which a given word is used as its head.

According to the syntactic pattern word-groups may be classified into predicative and non-predicative. Predicative word-groups have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence, e.g. he went, John works. All other word-groups are called non-predicative. Non-predicative word-groups may be subdivided into subordinative (e.g. red flower, a man of wisdom) and coordinative (e.g. women and children, do or die).

Structurally, all word-groups can be classified by the criterion of distribution into two extensive classes: endocentric and exocentric.

Endocentric word-groups are those that have one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group, i.e. the distribution

The meaning of word-groups can be divided into: 1) lexical and 2) structural (grammatical) components of the whole word-group and the distribution of its central member are identical. For instance, in the word-groups red flower, kind to people, the head-words are the noun flower and the adjective kind correspondingly. These word-groups are distributionally identical with their central components. According to their central members word-groups may be classified into: nominal groups or phrases (e.g. redflower), adjectival groups (e.g. kind to people), verbal groups (e.g. to speak well), etc.

Exocentric word-groups are those that have no central component and the distribution of the whole word-group is different from either of its members. For instance, the distribution of the word-group side by side is not identical with the distribution of its component-members, i.e. the component-members are not syntactically substitutable for the whole word-group.

3. Types of meaning of word-groups

The meaning of word-groups can be divided into: 1) lexical and 2) structural (grammatical) components).

1. The lexical meaning of the word-group may be defined as the combined lexical meaning of the component words. Thus, the lexical meaning of the word-group red flower may be described denotationally as the combined meaning of the words red and flower. However, the term ‘combined lexical meaning’ is not to imply that the meaning of the word-group is a mere additive result of all the lexical meanings of the component members. The lexical meaning of the word-group predominates over the lexical meanings of its constituents.

2. The structural meaning of the word-group is the meaning conveyed mainly by the pattern of arrangement of its constituents. For example, such word-groups as school grammar (школьная грамматика) and grammar school (грамматическая школа) are semantically different because of the difference in the pattern of arrangement of the component words. The structural meaning is the meaning expressed by the pattern of the word-group but not either by the word school or the word grammar. It follows that it is necessary to distinguish between the structural meaning of a given type of a word-group as such and the lexical meaning of its constituents.

The lexical and structural components of meaning in word-groups are interdependent and inseparable. For instance, the structural pattern of the word-groups all day long, all night long, all week long in ordinary usage and the word-group all the sun long is identical. The generalized meaning of the pattern may be described as ‘a unit of time’. Replacing day, night, week by another noun – the sun the structural meaning of the pattern does not change. The group all the sun long functions semantically as a unit of time. But the noun sun included in the group, continues to carry the semantic value, i.e. the lexical meaning that it has in word-groups of other structural patterns, e.g. the sun rays, African sun.

Thus, the meaning of the word-group is derived from the combined lexical meanings of its constituents and is inseparable from the meaning of the pattern of their arrangement.

4. Motivation in word-groups

Semantically all word-groups can be classified into motivated and non-motivated.

A word-group is lexically motivated if the combined lexical meaning of the group is deducible from the meanings of its components, e.g. red flower, heavy weight, teach a lesson.

If the combined lexical meaning of a word-group is not deducible from the lexical meanings of its constituent components, such a word-group is lexically non-motivated, e.g. red tape (‘official bureaucratic methods’), take place (‘occur’).

The degree of motivation can be different. Between the extremes о complete motivation and lack of motivation there are innumerable intermediate cases. For example, the degree of lexical motivation in the nominal group black market is higher than in black death, but lower than in black dress, though none of the groups can be considered completely non-motivated. This is also true of other words-groups, e.g old man and old boy both of which may be regarded as lexically motivated though the degree of motivation in old man is noticeably higher.

It should be noted that seemingly identical word-groups are sometimes found to be motivated or non-motivated depending on their semantic interpretation. Thus, apple sauce is lexically motivated where it means ‘a sauce made of apples’ but when used to denote ‘nonsense’ it is clearly non-motivated.

Completely non-motivated or partially motivated word-groups are described as phraseological units or idioms.

Изображение слайда

2

Слайд 2: Word-groups vs. phraseological units

Words put together to form lexical units make phrases or word-groups.

The largest two-facet lexical unit comprising more than one word is the word-group observed on the syntagmatic level of analysis. The degree of structural and semantic cohesion of word-groups may vary.

Functionally and semantically inseparable word-groups like at least, point of view, by means of, take place are phraseological units.

Semantically and structurally more independent word-groups a week ago, man of wisdom, take lessons, kind to people are defined as free or variable word-groups or phrases

Изображение слайда

3

Слайд 3: Valency of words

The two main linguistic factors to be considered in uniting words into word-groups are:

1) the lexical valency of words

2) the syntactic valency of words.

Изображение слайда

4

Слайд 4: Lexical valency

Words are used in certain lexical contexts, i.e. in combination with other words.

The noun question is often combined with such adjectives as vital, pressing, urgent, disputable, delicate, etc.

This noun is a component of a number of other word-groups, e.g. to raise a question, a question of great importance, a question of the agenda, a question of the day, and many others.

Lexical valency is the possibility of lexical-semantic connections of a word with other words.

Lexical collocability is the realisation in speech of the potential connections of a word with other words.

Изображение слайда

Lexical valency acquires special importance in case of polysemy as through the lexical valency different meanings of a polysemantic word can be distinguished, e.g.

heavy weight (safe, table, etc.),

heavy snow (storm, rain, etc.),

heavy drinker (eater, etc.),

heavy sleep (disappointment, sorrow, etc.),

heavy industry (tanks, etc.), and so on.

These word-groups are called collocations or such combinations of words which condition the realization of a certain meaning

Изображение слайда

The range of the lexical valency of words is linguistically restricted by the inner structure of the English word-stock.

Though the verbs lift and raise are treated as synonyms, only raise is collocated with the noun question.

The verb take may be interpreted as ‘grasp’, ’seize’, ‘catch’, etc. but only take is found in collocations with the nouns examination, measures, precautions, etc.,

only catch in catch smb. napping

and grasp in grasp the truth.

Изображение слайда

The restrictions of lexical valency of words may manifest themselves in the lexical meanings of the polysemantic members of word-groups.

The adjective heavy, e.g., is combined with the words food, meals, supper, etc. in the meaning ‘rich and difficult to digest’.

But not all the words with the same component of meaning can be combined with this adjective *heavy cheese or *heavy sausage.

The lexical valency of correlated words in different languages is different: pot flowers – комнатные цветы

Изображение слайда

8

Слайд 8: Syntactic valency —

the aptness of a word to appear in different syntactic structures.

The minimal syntactic context in which words are used when brought together to form word-groups is described as the pattern of the word-groups.

E.g., the verb to offer can be followed by the infinitive ( to offer to do smth ) and the noun ( to offer a cup of tea ).

The verb to suggest can be followed by the gerund ( to suggest doing smth ) and the noun ( to suggest an idea ). The syntactic valency of these verbs is different.

Изображение слайда

The adjectives clever and intelligent are seen to possess different syntactic valency as clever can be used in word-groups having the pattern:

Adjective-Preposition at+Noun : clever at mathematics, whereas intelligent can never be found in exactly the same word-group pattern.

The syntactic valency of correlated words in different languages is not identical, in English to influence a person, a decision, a choice ( verb +noun ) — in Russian влиять на человека, на решение, на выбор ( verb+ preposition+noun ).

Изображение слайда

T he individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its syntactic valency:

Keen + N: keen sight, hearing, etc.

Keen + on + N : keen on sports, tennis, etc.

Keen + V( inf ): keen to know, to find out, etc.

Thus word-groups may be regarded as minimal syntactic (or syntagmatic) structures that operate as distinguishing clues for different meanings of a polysemantic word.

Изображение слайда

11

Слайд 11: INTERDEPENDENCE OF STRUCTURE AND MEANING IN WORD-GROUPS

Syntactic structure and pattern of word-groups is the description of the order and arrangement of member-words in word-groups as parts of speech.

The syntactic structure of the word-group an old woman, a blue dress, clever man, red flower is an adjective and a noun, i.e. A+N ;

The syntactic structure of the word-groups wash a car, read books, take books, build houses – as a verb and a noun, i.e. V+N.

The syntactic structure of the word-groups a touch of the sun, a matter of importance — as a preposition and a noun, i.e. N+prp+N.

Изображение слайда

12

Слайд 12: Structural formulas:

V+N: ( to build houses ),

V+prp+N: ( to rely on somebody ),

V+N+prp+N: ( to hold something against somebody ),

V+N+V(inf.): ( to make somebody work ),

V+ V(inf.): ( to get to know ), and so on.

Изображение слайда

13

Слайд 13: Syntactic structure of word-groups

Word-groups may be described through the order and arrangement of the component members:

To see sth – verbal-nominal group;

To see to sth – ( If you see to something that needs attention, you deal with it ) verbal-prepositional-nominal, etc.

Изображение слайда

Word-groups may be classified according to their headwords into:

Nominal: red flower ;

Adjectival: kind to people ;

Verbal: to speak well, etc.

The head is not necessarily the component that occurs first in the word-group: great bravery, bravery in the struggle the noun bravery is the head whether followed or preceded by other words.

Изображение слайда

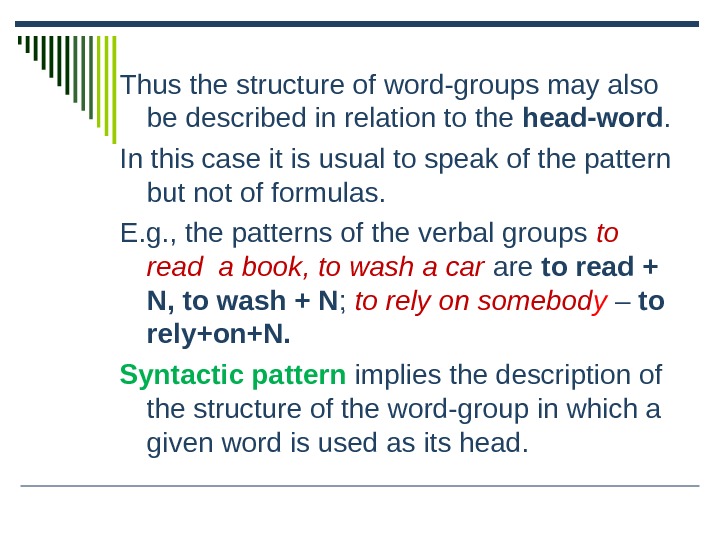

Thus the structure of word-groups may also be described in relation to the head-word.

In this case it is usual to speak of the pattern but not of formulas.

E.g., the patterns of the verbal groups to read a book, to wash a car are to read + N, to wash + N ; to rely on somebod y – to rely+on+N.

Syntactic pattern implies the description of the structure of the word-group in which a given word is used as its head.

Изображение слайда

16

Слайд 16: The interdependence of the pattern and meaning of head-words can be easily perceived by comparing word-groups of different patterns in which the same head-word is used

Three patterns with the verb ‘get’ as the head-word represent three different meanings of this verb:

get+ N ( get a letter, information, money, etc.);

get+ to +N ( get to Moscow, to the Institute, etc.);

get+N+V (inf.) ( get somebody to come, to do the work, etc.).

Изображение слайда

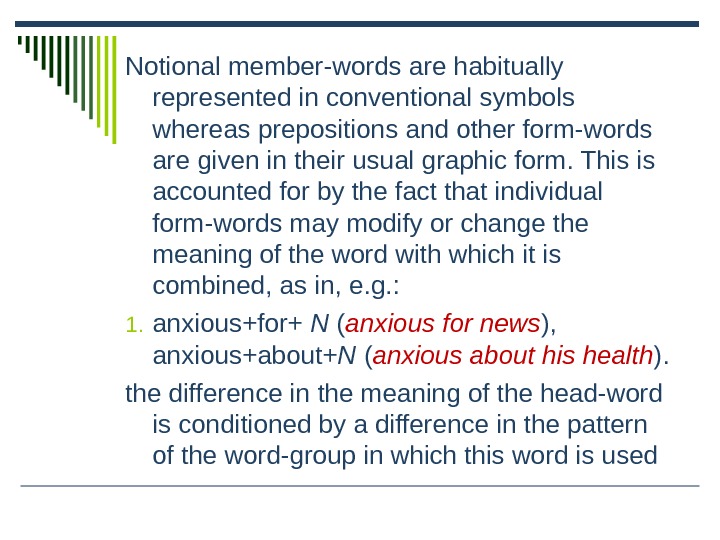

Notional member-words are habitually represented in conventional symbols whereas prepositions and other form-words are given in their usual graphic form. This is accounted for by the fact that individual form-words may modify or change the meaning of the word with which it is combined, as in, e.g.:

anxious+for+ N ( anxious for news ), anxious+about+ N ( anxious about his health ).

the difference in the meaning of the head-word is conditioned by a difference in the pattern of the word-group in which this word is used

Изображение слайда

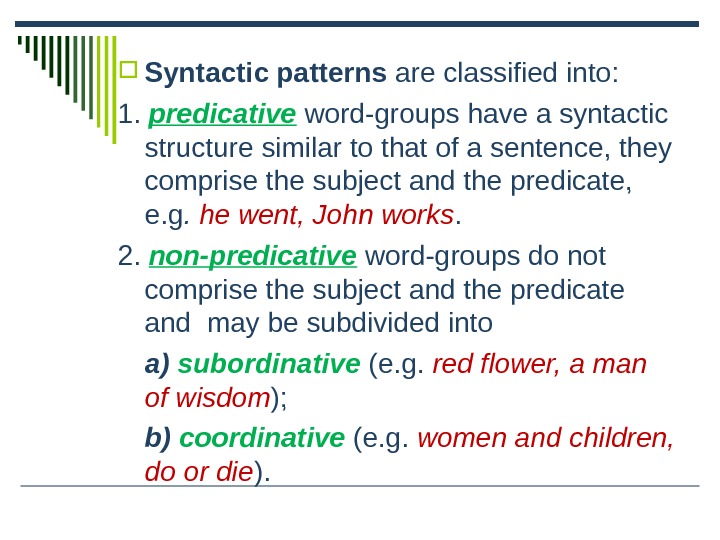

Syntactic patterns are classified into:

1. predicative word-groups have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence, they comprise the subject and the predicate, e.g. he went, John works.

2. non-predicative word-groups do not comprise the subject and the predicate and may be subdivided into

a) subordinat ive (e.g. red flower, a man of wisdom );

b) coordinative (e.g. women and children, do or die ).

Изображение слайда

19

Слайд 19: Classification of word-groups

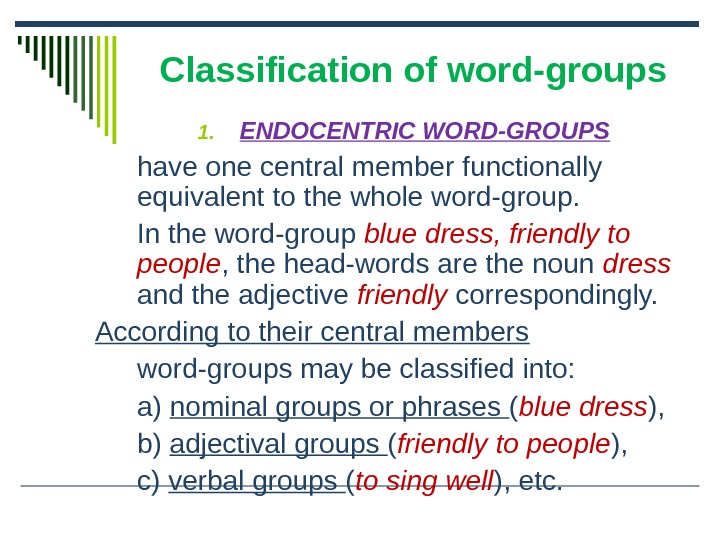

ENDOCENTRIC WORD-GROUPS

have one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group.

In the word-group blue dress, friendly to people, the head-words are the noun dress and the adjective friendly correspondingly.

According to their central members

word-groups may be classified into:

a) nominal groups or phrases ( blue dress ),

b) adjectival groups ( friendly to people ),

c) verbal groups ( to sing well ), etc.

Изображение слайда

2. EXOCENTRIC WORD-GROUPS

have no central component and the distribution of the whole word-group is different from either of its members.

For instance, the distribution of the word-groups side by side, at first, grow smaller is not identical with the distribution of their component-members, i.e. the component-members are not syntactically substitutable for the whole word-group.

Изображение слайда

21

Слайд 21: TYPES OF MEANING OF WORD-GROUPS

The lexical meaning –

the combined lexical meaning of the component words, e.g. a blind man may be described denotationally as the combined meaning of the words blind and man.

In most cases the lexical meanings of the word-group predominates over the lexical meanings of its components, e.g. blind alley, blind date.

Polysemantic words are used in word-groups only in one of their meanings. These meanings of the component words in such word-groups are mutually interdependent and inseparable. Semantic inseparability of word-groups treats them as self-contained lexical units.

Изображение слайда

The structural meaning

of the word-group is the meaning conveyed mainly by the pattern of arrangement of its components, e.g., such word-groups as school grammar and grammar school are semantically different because of the difference in the pattern of arrangement of the component words.

The structural meaning is the meaning expressed by the pattern of the word-group.

Изображение слайда

Interrelation of lexical and structural meaning in word-groups

The lexical and structural components of meaning in word-groups are interdependent and inseparable. The structural pattern in all the day long, all the night long, all the week long in ordinary usage and the word-group all the sun long is identical. The generalised meaning of the pattern ‘a unit of time’.

Replacing day, night, week by another noun the sun structural meaning of the pattern does not change. The group all the sun long functions semantically as a unit of time. But the noun sun included in the group continues to carry the semantic value or the lexical meaning that it has in word-groups of other structural patterns (cf. the sun rays, African sun, etc.).

Изображение слайда

It follows that the meaning of the word-group is derived from the combined lexical meanings of its constituents and is inseparable from the meaning of the pattern of their arrangement.

a factory hand − ‘ a factory worker’

a hand bag − ‘ a bag carried in the hand’.

Though the word hand makes part of both its lexical meaning and the role it plays in the structure of word-groups is different which accounts for the difference in the lexical and structural meaning of the word-groups under discussion.

Thus, the meaning of the word-group is derived from the combined lexical meanings of its constituents and is inseparable from the meaning of the pattern of their arrangement.

Изображение слайда

25

Слайд 25: Polysemantic and monosemantic patterns

Word-groups represented by different structural formulas are as a rule semantically different because of the difference in the grammatical component of meaning.

Structurally identical patterns, e.g. heavy+ N, may be representative of different meanings of the adjective heavy which is perceived in the word-groups heavy rain (snow, storm), heavy smoker (drinker), heavy weight (table), etc. all of which have the same pattern — heavy +N.

Изображение слайда

Structurally simple patterns are as a rule polysemantic, i.e. representative of several meanings of a polysemantic head-word, whereas structurally complex patterns are monosemantic and condition just one meaning of the head-member.

The simplest verbal structure V+N and the corresponding pattern are as a rule polysemantic (compare, e.g. take +N (take tea, coffee); take the bus, the tram, take measures, precautions, etc.), whereas a more complex pattern, e.g. take+to+ N is monosemantic (e.g. take to sports ).

Изображение слайда

27

Слайд 27: MOTIVATION IN WORD-GROUPS

A word-group is lexically-motivated if the combined lexical meaning of the group is deducible from the meaning of its components, e.g. red flower, heavy weight, take lessons.

If the combined lexical meaning of a word-group is not deducible from the lexical meanings of its constituent components, such a word-group is lexically non-motivated, e.g. red tape (official bureaucratic methods) take place (occur).

Изображение слайда

The degree of motivation can be different. Between the extremes of complete motivation and lack of motivation there are innumerable intermediate cases.

E.g., the degree of lexical motivation in the nominal group black market is higher than in black death, but lower than in black dress, though none of the groups can be considered completely non-motivated.

Изображение слайда

Completely motivated word-groups are correlated with certain structural types of compound words.

Verbal groups having the structure V+N, e.g. to read books, to love music, etc., are habitually correlated with the compounds of the pattern N+(V+er) (book-reader, music-lover);

adjectival groups such as A + prp+N (e.g. rich in oil, shy before girls ) are correlated with the compounds of the pattern N+A, e.g. oil-rich, girl-shy.

Изображение слайда

Seemingly identical word-groups are sometimes found to be motivated or non-motivated depending on their semantic interrelation. Thus, apple sauce is lexically motivated when it means ‘a sauce made of apples’ but when used to denote ‘nonsense’ it is clearly non-motivated.

Completely non-motivated or partially motivated word-groups are called phraseological units or idioms.

Изображение слайда

31

Слайд 31: Summary and Conclusions

1. Words put together to form lexical units make up phrases or word-groups. The main factors active in bringing words together are lexical and syntactic valency of the components of word-groups.

Изображение слайда

2. Lexical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in various collocations. All the words of the language possess a certain norm of lexical valency. Restrictions of lexical valency are to be accounted for by the inner structure of the vocabulary of the English language.

Изображение слайда

Lexical valency of polysemantic words is observed in various collocations in which these words are used. Different meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its lexical valency.

Изображение слайда

Syntactic valency is the aptness of a word to appear in various syntactic structures. All words possess a certain norm of syntactic valency. Restrictions of syntactic valency are to be accounted for by the grammatical structure of the language. The range of syntactic valency of each individual word is essentially delimited by the part of speech the word belongs to and also by the specific norm of syntactic valency peculiar to individual words of Modern English.

Изображение слайда

The syntactic valency of a polysemantic word may be observed in the different structures in which the word is used. Individual meanings of a polysemantic word may be described through its syntactic valency.

Изображение слайда

Structurally, word-groups may be classified by the criterion of distribution into endocentric and exocentric.

Endocentric word-groups can be classified according to the head-word into nominal, adjectival, verbal and adverbial groups or phrases.

Изображение слайда

Semantically all word-groups may be classified into motivated and non-motivated. Non-motivated word-groups are usually described as phraseological units.

Изображение слайда

Зыкова И.В. Практический курс английской лексикологии. М.: Академия, 2006. – С. 121-124.

Гинзбург Р.З. Лексикология английского языка. М.: Высшая школа, 1979. – С. 64-74.

Антрушина Г.Б., Афанасьева О.В., Морозова Н.Н. Лексикология английского языка. М.: Дрофа, 2006. – С. 225- 256.

Изображение слайда

39

Последний слайд презентации: WORD-GROUPS Lecture 12: WORD-GROUPS

Изображение слайда

- Размер: 211 Кб

- Количество слайдов: 39

Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation

Free Word-groups and Phraseological units

Done by: Ivanova Ksenija

Group: 701(2)

Ishim, 2013

Content

-

Introduction________________________________________Page№3

-

Phraseological Units and word-groups___________________Page№4

-

Classification of Phraseological units____________________Page№6

-

The etymological classification of phraseological units____________Page№8

-

How to Distinguish Phraseological Units

from Free Word-Groups___________________________________Page№9

-

Сonclusion_________________________________________Page№11

-

Bibliography_______________________________________Page№12

Introduction

Phraseology is a scholarly approach to language which developed in the twentieth century [1]. It took its start when Charles Bally’s notion of locutions phraseologiques entered Russian lexicologyand lexicography in the 1930s and 1940s and was subsequently developed in the former Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries. From the late 1960s on it established itself in (East) German linguistics but was also sporadically approached in English linguistics. The earliest English adaptations of phraseology are by Weinreich (1969) within the approach of transformational grammar), Arnold (1973), and Lipka (1992) [2].

In Great Britain as well as other Western European countries, phraseology has steadily been developed over the last twenty years. The activities of the European Society of Phraseology and the European Association for Lexicography with their regular conventions and publications attest to the prolific European interest in phraseology. Bibliographies of recent studies on English and general phraseology are included in Welte (1990) and specially collected in Cowie & Howarth (1996) whose bibliography is reproduced and continued on the internet and provides a rich source of the most recent publications in the field [3].

Phraseological Units and Word-group

Phraseology is a branch of lexicology studying phraseological units (set expressions, praseologisms, or idioms (in foreign linguistics).

Phraseological units differ from free word-groups semantically and structurally:

1) they convey a single concept and their meaning is idiomatic, i.e. it is not a mere total of the meanings of their components

2) they are characterized by structural invariability (no word can be substituted for any component of a phraseological unit without destroying its sense (to have a bee in one’s bonnet (not cap or hat).

3) they are not created in speech but used as ready-made units.

A word-group is the largest two-facet lexical unit comprising more than one word but expressing one global concept.

The lexical meaning of the word groups is the combined lexical meaning of the component words. The meaning of the word groups is motivated by the meanings of the component members and is supported by the structural pattern. But it’s not a mere sum total of all these meanings! Polysemantic words are used in word groups only in 1 of their meanings. These meanings of the component words in such word groups are mutually interdependent and inseparable (blind man – «a human being unable to see», blind type – «the copy isn’t readable).

Word groups possess not only the lexical meaning, but also the meaning conveyed mainly by the pattern of arrangement of their constituents. The structural pattern of word groups is the carrier of a certain semantic component not necessarily dependent on the actual lexical meaning of its members (school grammar – «grammar which is taught in school», grammar school – «a type of school»). We have to distinguish between the structural meaning of a given type of word groups as such and the lexical meaning of its constituents.

Words put together to form lexical units make phrases or word-groups. One must recall that lexicology deals with words, word-forming morphemes and word-groups.

The degree of structural and semantic cohesion of word-groups may vary. Some word-groups, e.g. at least, point of view, by means, to take place, etc. seem to be functionally and semantically inseparable. They are usually described as set phrases, word-equivalents or phraseological units and are studied by the branch of lexicology which is known as phraseology. In other word-groups such as to take lessons, kind to people, a week ago, the component-members seem to possess greater semantic and structural independence. Word-groups of this type are defined as free word-groups or phrases and are studied in syntax.

Structurally word-groups can be considered in different ways. Word-groups may be described as for the order and arrangement of the component-members. E.g., the word-group to read a book can be classified as a verbal-nominal group, to look at smb. – as a verbal-prepositional-nominal group, etc.

By the criterion of distribution all word-groups may be divided into two big classes: according to their head-words and according to their syntactical patterns.

Word-groups may be classified according to their head-words into:

nominal groups – red flower;

adjective groups – kind to people;

verbal groups – to speak well.

The head is not necessarily the component that occurs first.

Word-groups are classified according to their syntactical pattern into predicative and non-predicative groups. Such word-groups as he went, Bob walks that have a syntactic structure similar to that of a sentence are termed as predicative, all others are non-predicative ones.

Non-predicative word-groups are divided into subordinative and coordinative depending on the type of syntactic relations between the components. E.g., a red flower, a man of freedom are subordinative non-predicative word-groups, red and freedom being dependent words, while day and night, do and die are coordinative non-predicative word-groups [4].

Classification of Phraseological units

Phraseological units are classified in accordance with several criteria.

In the classification proposed by acad. Vinogradov Phraseological units are classified according to the semantic principle, and namely to the degree of motivation of meaning, i.e. the relationship between the meaning of the whole unit and the meaning of its components. Three groups are distinguished: phraseological fusions (сращения), phraseological unities (единства), phraseological combinations (сочетания).

1. Phraseological fusions are non-motivated. The meaning of the whole is not deduced from the meanings of the components: to kiss the hare’s foot (опаздывать), to kick the bucket (сыграть в ящик), the king’s picture (фальшивая монета)

2. Phraseological unities are motivated through the image expressed in the whole construction, the metaphores on which they are based are transparent: to turn over a new leaf, to dance on a tight rope.

3. Phraseological combinations are motivated; one of their components is used in its direct meaning while the other can be used figuratively: bosom friend, to get in touch with.

Prof. Smirnitsky classifies phraseological units according to the functional principle. Two groups are distinguished: phraseological units and idioms.

Phraseological units are neutral, non-metaphorical when compared to idioms: get up, fall asleep, to take to drinking. Idioms are metaphoric, stylistically coloured: to take the bull by the horns, to beat about the bush, to bark up the wrong tree.

Structurally prof. Smirnitsky distinguishes one-summit (one-member) and many-summit (two-member, three-member, etc.) phraseological units, depending on the number of notional words: against the grain (не по душе), to carry the day (выйти победителем), to have all one’s eggs in one basket.

Prof. Amosova classifies phraseological units according to the type of context. Phraseological units are marked by fixed (permanent) context, which can’t be changed: French leave (but not Spanish or Russian). Two groups are singled out: phrasemes and idioms.

1. Prasemes consist of two components one of which is praseologically bound, the second serves as the determining context: green eye (ревнивый взгляд), green hand (неопытный работник), green years (юные годы), green wound (незажившая рана), etc.

2. Idioms are characterized by idiomaticity: their meaning is created by the whole group and is not a mere combination of the meanings of its components: red tape (бюрократическая волокита), mare’s nest (нонсенс), to pin one’s heart on one’s sleeve (не скрывать своих чувств).

Prof. Koonin’s classification is based on the function of the phraseological unit in communication. Phraseological units are classified into: nominative, nominative-communicative, interjectional, communicative.

1. Nominative phraseological units are units denoting objects, phenomena, actions, states, qualities. They can be:

a) substantive – a snake in the grass (змея подколодная), a bitter pill to swallow;

b) adjectival – long in the tooth (старый);

c) adverbial – out of a blue sky, as quick as a flash;

d) prepositional – with an eye to (с намерением), at the head of.

2. Nominative-communicative units contain a verb: to dance on a volcano, to set the Thames on fire (сделать что-то необычное), to know which side one’s bread is buttered, to make (someone) turn (over) in his grave, to put the hat on smb’s misery (в довершение всех его бед).

3. Interjectional phraseological units express the speaker’s emotions and attitude to things: A pretty kettle of fish! (хорошенькое дельце), Good God! God damn it! Like hell!

4. Communicative phraseological units are represented by provebs (An hour in the morning is worth two in the evening; Never say “never”) and sayings. Sayings, unlike provebs, are not evaluative and didactic: That’s another pair of shoes! It’s a small world.

In dictionaries of idioms the traditional and oldest principle for classifying phraseological units – the thematic principle – is used.

The etymological classification of phraseological units

According to their origin phraseological units are divided into native and borrowed.

Native phraseological units are connected with British realia, traditions, history:

By bell book and candle (jocular) – бесповоротно. This unit originates from the text of the form of excommunication (отлучение от церкви) which ends with the following words: Doe to the book, quench the candle, ring the book!

To carry coal to Newcastle (parallells: Ехать в Тулу со своим самоваром, везти сов в Афины, везти пряности в Иран)

According to Cocker – по всем правилам, точно. E. Cocker is the author of a well-known book on arithmetics.

To native phraseological units also belong familiar quotations came from works of English literature. A lot of them were borrowed from works by Shakespeare: a fool’s paradise (“Romeo and Juliet”), the green-eyed monster (“Othello”), murder will out – шила в мешке не утаишь (“Macbeth”), etc.

A great number of native phraseological units originate from professional terminologies or jargons: one’s last card, the game is up/over lay one’s cards on the table hold all the aces (terms of gambling).

Borrowed phraseological units come from several sources.

A number of units were borrowed from the Bible and were fully assimilated: to cast pearl before swine, the root of all evil, a woolf in sheep’s clothing, to beat swords into plough-shares.

A great amount of units were taken from ancient mythology and literature: the apple of discord, the golden age, the thread of Ariadne, at the greek calends ( до греческих календ, никогда), etc, They are international in their character.

A lot of phraseologisms were borrowed from different languages – let’s return to our muttons (revenons à nos moutons), blood and iron (принцип политики Бисмарка – Blut und Eisen), blue blood, to lose face (кит. tiu lien) and from the other variants of the English language (AmE) – a green light, bark up the wrong tree, to look like a million dollars, time is money (B. Franklin “Advice to a Young Tradesman”).

How to Distinguish Phraseological Units from Free Word-Groups

The task of distinguishing between free word-groups and phraseological units is further complicated by the existence of a great number of marginal cases, the so-called semi-fixed or semi-free word-groups, also called non-phraseological word-groups which share with phraseological units their structural stability but lack their semantic unity and figurativeness (e. g. to go to school, to go by bus, to commit suicide). There are two major criteria for distinguishing between phraseological units and free word-groups: semantic and structural.

The semantic shift affecting phraseological units does not consist in a mere change of meanings of each separate constituent part of the unit. The meanings of the constituents merge to produce an entirely new meaning: e. g. to have a bee in one’s bonnet means «to have an obsession about something; to be eccentric or even a little mad». The humorous metaphoric comparison with a person who is distracted by a bee continually buzzing under his cap has become erased and half-forgotten, and the speakers using the expression hardly think of bees or bonnets but accept it in its transferred sense: «obsessed, eccentric».

In the traditional approach, phraseological units have been defined as word-groups conveying a single concept (whereas in free word-groups each meaningful component stands for a separate concept). The structural criterion brings forth pronounced distinctive features characterising phraseological units and contrasting them to free word-groups. Structural invariability is an essential feature of phraseological units, though, as we shall see, some of them possess it to a lesser degree than others.

Structural invariability of phraseological units finds expression in a number of restrictions:

1) restriction in substitution. As a rule, no word can be substituted for any meaningful component of a phraseological unit without destroying its sense.

2) The second type of restriction is the restriction in introducing any additional components into the structure of a phraseological unit. In a free word-group such changes can be made without affecting the general meaning of the utterance.

3) The third type of structural restrictions in phraseological units is grammatical invariability. Yet again, as in the case of restriction in introducing additional components, there are exceptions to the rule and these are probably even more numerous. One can build a castle in the air, but also castles.

Conclusion

The Phraseological units are closely connected with people’s mentality .The present day English can’t be considered full of value without idiomatic usage, as the use of idioms is the first sign of a certain language’s developing. Idiomatic sentences enrich a language and the knowledge of idioms signal that the speaker knows the language on the level of a native speaker. The belles-lettres investigated by us revealed a great number of idiomatic sentences used by prominent writers in their works to make their language more expressive and colourful. This research proposes practical hints for teachers wishing to diverse their lessons with idioms.

So idioms are integral part of language which make our speech more colourful and authentically native.

Bibliography

1.Knappe, Gabriele. (2004) Idioms and Fixed Expressions in English Language Study before 1800. Peter Lang;

2.Weinreich, Uriel (1969) Problems in the Analysis of Idioms. In J. Puhvel (ed.), Substance and Structure of Language, 23-81. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press;

3.Arnold, I.V. (1973) The English Word Moscow: Higher School Publishing House;

4.Internet site: http://www.roman.by/r-177452.html

5.Amоsоvа N. N. (1963) Basic course in English phraseology L;

6. Koonin А.V.( 1972) Phraseology of modern English. M.;

7. Vinogradov V.V. (1977) The chief types of Phraseological units in the Russian Language. – M.;

8. Zikova I.V.( 2005) А Practical Course in English Lexicology. М;

|

0 |

Free Word-groups and Phraseological units