Last Update: Jan 03, 2023

This is a question our experts keep getting from time to time. Now, we have got the complete detailed explanation and answer for everyone, who is interested!

Asked by: Jamir Rolfson

Score: 4.7/5

(58 votes)

Etymology. The English word Germany derives from the Latin Germania, which came into use after Julius Caesar adopted it for the peoples east of the Rhine.

What is the origin of Germany?

The concept of Germany as a distinct region in Central Europe can be traced to Roman commander Julius Caesar, who referred to the unconquered area east of the Rhine as Germania, thus distinguishing it from Gaul (France).

Where are Germans from originally?

Ancient history

The German ethnicity emerged among early Germanic peoples of Central Europe, particularly the Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringii, Alemanni and Baiuvarii.

What was Germany called before Germany?

Before it was called Germany, it was called Germania. In the years A.D. 900 – 1806, Germany was part of the Holy Roman Empire. From 1949 to 1990, Germany was made up of two countries called the Federal Republic of Germany (inf.

Why do we call Germany and not Deutschland?

Many countries have a name that they call themselves (known as an endonym) but are called different names by other countries (known as an exonym). … Germany, for example, was called Germany by its inhabitants long before the country was united and began to call itself Deutschland.

44 related questions found

How did we get Germany from Deutschland?

The root of the name is from the Gauls, who called the tribe across the river the Germani, which might have meant “neighbor” or maybe “men of the forest.” English borrowed the name in turn and anglicized the ending to get Germany.

Why is Germany called Fatherland?

Motherland was defined as «the land of one’s mother or parents,» and fatherland as «the native land of one’s fathers or ancestors.» … The Latin word for fatherland is «patria.» One more explanation: Fatherland was a nationalistic term used in Nazi Germany to unite Germany in the culture and traditions of ancient Germany.

What was Germany called in 1700?

The Kingdom of Prussia emerged as the leading state of the Empire. Frederick III (1688–1701) became King Frederick I of Prussia in 1701.

What is the religion of Germany?

Christianity is the dominant religion in Germany while Islam is the biggest minority religion. There are a number more faiths, however, that together account for the religions of around 3-4% of the population. Further religions practiced in Germany include: Judaism.

Who lived in Germany before the Romans?

During the Gallic Wars of the 1st century BC, the Roman general Julius Caesar encountered peoples originating from beyond the Rhine. He referred to these people as Germani and their lands beyond the Rhine as Germania.

Who is the most famous person from Germany?

Top 10 Famous German People

- Ludwig van Beethoven. Ludwig van Beethoven-by Joseph Karl Stieler- Wikimedia Commons. …

- Adolf Hitler. Adolf Hitler- Wikimedia Commons. …

- Irma Grese. Irma Grese- Wikimedia Commons. …

- Albert Einstein. …

- Angela Merkel. …

- Otto von Bismark. …

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. …

- Hugo Boss.

Are Germans Slavic?

No, Germans are not Slavic. They are a Germanic people. German belongs to the West Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family.

What percent of Germany is black?

A UN team that recently examined racism in Germany estimated there to be many as one million people with “African roots” in Germany, more than 1% of the population.

Is Germany a safe country?

Is Germany safe? Well, Germany ranks 22nd, one of the most peaceful among 163 countries in the world, according to the Global Peace Index 2019 rankings. It also ranks 20th according to the Societal Safety and Security domain.

When did the Germans destroy Rome?

The Sack of Rome on 24 August 410 AD was undertaken by the Visigoths led by their king, Alaric. At that time, Rome was no longer the capital of the Western Roman Empire, having been replaced in that position first by Mediolanum in 286 and then by Ravenna in 402.

What food is Germany known for?

Top 10 Traditional German Foods

- Brot & Brötchen. …

- Käsespätzle. …

- Currywurst. …

- Kartoffelpuffer & Bratkartoffeln. …

- Rouladen. …

- Schnitzel. …

- Eintopf. …

- Sauerbraten.

Is Germany a Catholic or Protestant country?

The majority of Germany’s Christians are registered as either Catholic (22.6 million) or Protestant (20.7 million). The Protestant Church has its roots in Lutheranism and other denominations that rose out of the 16th-century religious reform movement.

Which language is mostly spoken in Germany?

The official language of Germany is German, with over 95% of the population speaking German as their first language. Minority languages include Sorbian, spoken by 0.09% in the east of Germany and North Frisian spoken in Nordfriesland by around 10,000 people, or 0.01%, who also speak German.

Who ruled Germany in 1700?

The main development in Germany during the 18th century was the rise of Prussia. In the 17th century, the Hohenzollern family ruled both Brandenburg and East Prussia. In 1701 the ruler of both was Elector Frederick III. In that year he crowned himself King of Prussia.

How old is Germany?

The nation-state now known as Germany was first unified in 1871 as a modern federal state, the German Empire. In the first half of the 20th century, two devastating World Wars, of which Germany was responsible for, left the country occupied by the victorious Allied powers.

Why is Germany so rich?

1. The important role of industry. In Germany the share of industry in gross value added is 22.9 per cent, making it the highest among the G7 countries. The strongest sectors are vehicle construction, electrical industry, engineering and chemical industry.

Why is Germany so powerful?

German power rests primarily on the country’s economic strength. In terms of gross domestic product (GDP), Germany ranks fourth in the world, behind the United States, China, and Japan, and ahead of France and the United Kingdom. … Germany has strong economic, social, and political ties with all its neighbors.

Is Germany feminine or masculine?

With a score of 66 Germany is considered a Masculine society. Performance is highly valued and early required as the school system separates children into different types of schools at the age of ten.

Etymology. The English word Germany derives from the Latin Germania, which came into use after Julius Caesar adopted it for the peoples east of the Rhine.

Contents

- 1 Are Germans from Germania?

- 2 Where did the Germans come from?

- 3 Are Germanic tribes from Germany?

- 4 Why isn’t Germany called Germania?

- 5 Is Germanic Europe Germany?

- 6 What was Germany before it was called Germany?

- 7 What race is Germany?

- 8 Who founded Germany?

- 9 Who first settled Germany?

- 10 Who lived in Germania?

- 11 Is German a race or ethnicity?

- 12 What language did German come from?

- 13 When did Germania become Germany?

- 14 When did Germany become Germany?

- 15 When did Germany come into existence?

- 16 Where is Germania?

- 17 Were there Vikings in Germany?

- 18 What is the difference between German and Germanic?

- 19 Are Germans Slavic?

- 20 What percentage of Germany is black?

Are Germans from Germania?

In modern German, the ancient Germani are referred to as Germanen and Germania as Germanien, as distinct from modern Germans (Deutsche) and modern Germany (Deutschland). The direct equivalents in English are, however, “Germans” for Germani and “Germany” for Germania, although the Latin “Germania” is also used.

Where did the Germans come from?

“Germans are a Germanic (or Teutonic) people that are indigenous to Central Europe… Germanic tribes have inhabited Central Europe since at least Roman times, but it was not until the early Middle Ages that a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge.”

Are Germanic tribes from Germany?

The origins of the Germanic peoples are obscure. During the late Bronze Age, they are believed to have inhabited southern Sweden, the Danish peninsula, and northern Germany between the Ems River on the west, the Oder River on the east, and the Harz Mountains on the south.

Why isn’t Germany called Germania?

Names from Germania

The name Germany and the other similar-sounding names above are all derived from the Latin Germania, of the 3rd century BC, a word simply describing fertile land behind the limes.

Is Germanic Europe Germany?

Most people with German ancestors will have, of course, Germanic Europe. AncestryDNA® test results show heritage from “Germanic Europe,” primarily located in Germany and Switzerland.

What was Germany before it was called Germany?

Germania

Before it was called Germany, it was called Germania. In the years A.D. 900 – 1806, Germany was part of the Holy Roman Empire. From 1949 to 1990, Germany was made up of two countries called the Federal Republic of Germany (inf. West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (inf.

What race is Germany?

Ethnic groups:

German 87.2%, Turkish 1.8%, Polish 1%, Syrian 1%, other 9% (2017 est.)

Who founded Germany?

Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck: a brief guide to the ‘founder of modern Germany’

Who first settled Germany?

The first people to inhabit the region we now call Germany were Celts. Gradually they were displaced by Germanic tribes moving down from the north, but their exact origins are unknown.

Who lived in Germania?

Germania was a Roman name originally given to tribe of people who lived along the Rhine River. They were a Teutonic people, who were first mentioned in the 4th century BC. The Gauls changed it from a name for a people to the name for the territory.

Is German a race or ethnicity?

By tradition, Germanness has always been an ethnic identity, based on shared descent or “blood”. But today Germany is becoming a multi-ethnic society like other Western countries.

What language did German come from?

German belongs to the West Germanic group of the Indo-European language family, along with English, Frisian, and Dutch (Netherlandic, Flemish). The recorded history of Germanic languages begins with their speakers’ first contact with the Romans, in the 1st century bce.

When did Germania become Germany?

These individuals were considered Germanic speakers. In order to differentiate between the regions and the people, English speakers began to refer to the country as Germany, which originates from the Roman term Germania. The first recorded use this word by English speakers dates back to 1520 AD.

When did Germany become Germany?

January 18th, 1871

The first date is when Germany was recognized as a region, on February 2nd, 962 AD. The second date is January 18th, 1871 when Germany became a unified state. Finally, October 3rd, 1990 was when East Germany and West Germany were united to form the present Federal Republic of Germany.

When did Germany come into existence?

January 18, 1871

The German Empire was founded on January 18, 1871, in the aftermath of three successful wars by the North German state of Prussia. Within a seven-year period Denmark, the Habsburg monarchy, and France were vanquished in short, decisive conflicts.

Where is Germania?

Germania is an ancient land extending east of Rhine and north of the upper and middle Danube, covering the area of modern Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Austria.

Were there Vikings in Germany?

The Norse sea-faring raiders we today call Vikings did not come from Germany, but rather its Northern European neighbors in Scandinavia; Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Vikings did settle within the borders of modern-day Northern Germany, with Hedeby and Sliasthorp likely being the most influential ones.

What is the difference between German and Germanic?

No, Germanic refers to a group of languages. German refers specifically to the German language.

Are Germans Slavic?

In Eastern Germany, around 20% of Germans have historic Slavic paternal ancestry, as revealed in Y-DNA testing. Similarly, in Germany, around 20% of the foreign surnames are of Slavic origin.

What percentage of Germany is black?

about one percent

As a result, Blacks comprise only about one percent of the German population. The presence of fewer Black people has not, however, meant less white racism. In fact, Germany has a long history of anti-Black racism.

Annabelle Dickerson is a travel guide and writer who has been to over 60 countries. She’s always on the lookout for new experiences, and loves nothing more than exploring a new destination. Annabelle has a passion for helping others experience the world, and believes that travel is one of the best ways to learn about other cultures.

The Germanic Europe DNA region is located in the most northwestern part of Western Europe and is adjacent to Eastern Europe and Russia a distinct DNA region. Germanic Europe is bordered by France to the west Sweden to the north Poland and Slovakia to the east and Croatia and Italy to the south.

Most written evidence of the early Celts comes from Greco-Roman writers who often grouped the Celts as barbarian tribes. … 500 due to Romanization and the migration of Germanic tribes Celtic culture had mostly become restricted to Ireland western and northern Britain and Brittany.

What are the 3 Germanic tribes?

Tacitus relates that according to their ancient songs the Germans were descended from the three sons of Mannus the son of the god Tuisto the son of Earth. Hence they were divided into three groups—the Ingaevones the Herminones and the Istaevones—but the basis for this grouping is unknown.

Are Germans Slavic?

No Germans are not Slavic. They are a Germanic people. German belongs to the West Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family.

What was Germany called in Roman times?

Germania

Germania (/dʒɜːrˈmeɪniə/ jur-MAY-nee-ə Latin: [ɡɛrˈmaːnia]) also called Magna Germania (English: Great Germania) Germania Libera (English: Free Germania) or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of the same name was a large historical region in north-central Europe during the Roman era …

Is jawohl a bad word?

“Jawohl” is a normal German word used as a strong affirmative. It doesn’t have a specifically Nazi background but one of its main uses has always been in the military including the Wehrmacht.

How do you respond to jawohl?

“Jawohl” is more of an acknowledgement (“I have understood and will comply with your request”) than an answer to a yes/no question “Sind Sie ein Einzelkind?” would be answered with “Ja” or “Nein”. Thus in my experience in a military context the question of an opposite of “Jawohl” rarely arises.

Is Herr still used?

It used to be the case that the name of professions was used as a honorific together with Herr (or Frau) e. g. Herr Schriftsteller (“Mr. Professional Writer”) Herr Installateur (“Mr. Plumber”) and so forth. This is generally outdated.

What do you call a German wife?

Frau is German for woman and wife and regardless of whether a woman is a married or not is also a title corresponding to English “Mrs”.

How do u say Happy Birthday in German?

In almost all circumstance a simple Happy Birthday (Alles Gute zum Geburtstag) works but if you want to be extra fancy you can try: Ganz herzliche Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag (All good wishes on your birthday)

What does fräulein mean in German?

Definition of fräulein

See also what is the ethnographic present

1 capitalized : an unmarried German woman —used as a title equivalent to Miss. 2 : a German governess.

How do you say dog in German?

The word for dog in German is quite simple and short which is rather surprising considering what language we are talking about. It is (der) Hund. It is pronounced [hʊnt] in the IPA transcription. It has the same origin as the English hound and the plural form is Hunde.

How do you say BOI in German?

jungeMann Junker Jüngling Bursche.

How do you say Germany in German?

Why is Germany so rich?

Undisputably wealthy it is Europe’s largest national economy and the continent’s leading manufacturer exporting vehicles machinery chemicals and electronics among other products. … Stripping out private debt the net wealth in Germany was €4 131 billion.

Why does Deutsch mean German?

The word “Deutsch” is a German word that derives from the Indo-European root word *þeudō (þ is pronounced as a voiceless th). … Therefore the word Deutsch refers to the vernaculars spoken in the Germanic region that were not the the lingua franca Latin.

Which nationality is Deutsch?

Deutsch or Deutsche may refer to: Deutsch or (das) Deutsche: The German language in Germany and other places. Deutsche: Germans as a weak masculine feminine or plural demonyma. Deutsch (word) originally referring to the Germanic vernaculars of the Early Middle Ages.

Explaining the Many Names of Germany/Deutschland/Allemagne etc.

Why do we say DEUTSCHLAND instead of GERMANY? #askagerman Series Pt. 1 | Feli from Germany

How to know a word’s gender | Super Easy German (70)

Origin and History of the Germans

Coordinates: 51°N 9°E / 51°N 9°E

|

Federal Republic of Germany Bundesrepublik Deutschland (German) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Deutschlandlied[a] «Song of Germany» |

|

|

Location of Germany (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

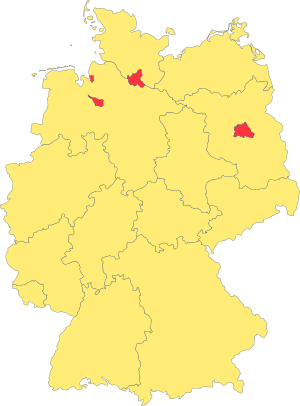

Berlin[b] 52°31′N 13°23′E / 52.517°N 13.383°E |

| Official languages | German[c] |

| Demonym(s) | German |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic[4] |

|

• President |

Frank-Walter Steinmeier |

|

• Chancellor |

Olaf Scholz |

| Legislature | Bundestag, Bundesrat[d] |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

357,592 km2 (138,067 sq mi)[5] (63rd) |

|

• Water (%) |

1.27 (2015)[6] |

| Population | |

|

• Q3 2022 estimate |

|

|

• Density |

232/km2 (600.9/sq mi) (58th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2020) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 9th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +49 |

| ISO 3166 code | DE |

| Internet TLD | .de |

Germany,[e] officially the Federal Republic of Germany,[f] is a country in Central Europe. It is the second-most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between the Baltic and North seas to the north, and the Alps to the south. Its 16 constituent states are bordered by Denmark to the north, Poland and the Czech Republic to the east, Austria and Switzerland to the south, and France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands to the west. The nation’s capital and most populous city is Berlin and its main financial centre is Frankfurt; the largest urban area is the Ruhr.

Various Germanic tribes have inhabited the northern parts of modern Germany since classical antiquity. A region named Germania was documented before AD 100. In 962, the Kingdom of Germany formed the bulk of the Holy Roman Empire. During the 16th century, northern German regions became the centre of the Protestant Reformation. Following the Napoleonic Wars and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the German Confederation was formed in 1815.

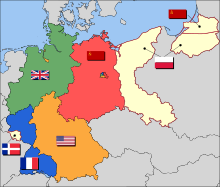

Formal unification of Germany into the modern nation-state was commenced on 18 August 1866 with the North German Confederation Treaty establishing the Prussia-led North German Confederation later transformed in 1871 into the German Empire. After World War I and the German Revolution of 1918–1919, the Empire was in turn transformed into the semi-presidential Weimar Republic. The Nazi seizure of power in 1933 led to the establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship, World War II, and the Holocaust. After the end of World War II in Europe and a period of Allied occupation, in 1949, Germany as a whole was organized into two separate polities with limited sovereignty: the Federal Republic of Germany, generally known as West Germany, and the German Democratic Republic, East Germany, while Berlin de jure continued its Four Power status. The Federal Republic of Germany was a founding member of the European Economic Community and the European Union, while the German Democratic Republic was a communist Eastern Bloc state and member of the Warsaw Pact. After the fall of communist led-government in East Germany, German reunification saw the former East German states join the Federal Republic of Germany on 3 October 1990—becoming a federal parliamentary republic.

Germany is a great power with a strong economy; it has the largest economy in Europe, the world’s fourth-largest economy by nominal GDP and the fifth-largest by PPP. As a global power in industrial, scientific and technological sectors, it is both the world’s third-largest exporter and importer. As a developed country it offers social security, a universal health care system and a tuition-free university education. Germany is a member of the United Nations, the European Union, NATO, the Council of Europe, the G7, the G20 and the OECD. It has the third-greatest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Etymology

The English word Germany derives from the Latin Germania, which came into use after Julius Caesar adopted it for the peoples east of the Rhine.[12] The German term Deutschland, originally diutisciu land (‘the German lands’) is derived from deutsch (cf. Dutch), descended from Old High German diutisc ‘of the people’ (from diot or diota ‘people’), originally used to distinguish the language of the common people from Latin and its Romance descendants. This in turn descends from Proto-Germanic *þiudiskaz ‘of the people’ (see also the Latinised form Theodiscus), derived from *þeudō, descended from Proto-Indo-European *tewtéh₂- ‘people’, from which the word Teutons also originates.[13]

History

Pre-human ancestors, the Danuvius guggenmosi, who were present in Germany over 11 million years ago, are theorized to be among the earliest ones to walk on two legs.[14] Ancient humans were present in Germany at least 600,000 years ago.[15] The first non-modern human fossil (the Neanderthal) was discovered in the Neander Valley.[16] Similarly dated evidence of modern humans has been found in the Swabian Jura, including 42,000-year-old flutes which are the oldest musical instruments ever found,[17] the 40,000-year-old Lion Man,[18] and the 35,000-year-old Venus of Hohle Fels.[19] The Nebra sky disk, created during the European Bronze Age, has been attributed to a German site.[20]

Germanic tribes and The Frankish Empire

The Germanic peoples are thought to date from the Nordic Bronze Age, early Iron Age, or the Jastorf culture.[21][22] From southern Scandinavia and northern Germany, they expanded south, east, and west, coming into contact with the Celtic, Iranian, Baltic, and Slavic tribes.[23]

Under Augustus, the Roman Empire began to invade lands inhabited by the Germanic tribes, creating a short-lived Roman province of Germania between the Rhine and Elbe rivers. In 9 AD, three Roman legions were defeated by Arminius.[24] By 100 AD, when Tacitus wrote Germania, Germanic tribes had settled along the Rhine and the Danube (the Limes Germanicus), occupying most of modern Germany. However, Baden-Württemberg, southern Bavaria, southern Hesse and the western Rhineland had been incorporated into Roman provinces.[25][26][27] Around 260, Germanic peoples broke into Roman-controlled lands.[28] After the invasion of the Huns in 375, and with the decline of Rome from 395, Germanic tribes moved farther southwest: the Franks established the Frankish Kingdom and pushed east to subjugate Saxony and Bavaria, and areas of what is today eastern Germany were inhabited by Western Slavic tribes.[25]

East Francia and The Holy Roman Empire

Charlemagne founded the Carolingian Empire in 800; it was divided in 843.[29] The eastern successor kingdom of East Francia stretched from the Rhine in the west to the Elbe river in the east and from the North Sea to the Alps.[29] Subsequently, the Holy Roman Empire emerged from it. The Ottonian rulers (919–1024) consolidated several major duchies.[30] In 996, Gregory V became the first German Pope, appointed by his cousin Otto III, whom he shortly after crowned Holy Roman Emperor. The Holy Roman Empire absorbed northern Italy and Burgundy under the Salian emperors (1024–1125), although the emperors lost power through the Investiture Controversy.[31]

Under the Hohenstaufen emperors (1138–1254), German princes encouraged German settlement to the south and east (Ostsiedlung).[32] Members of the Hanseatic League, mostly north German towns, prospered in the expansion of trade.[33] The population declined starting with the Great Famine in 1315, followed by the Black Death of 1348–50.[34] The Golden Bull issued in 1356 provided the constitutional structure of the Empire and codified the election of the emperor by seven prince-electors.[35]

Johannes Gutenberg introduced moveable-type printing to Europe, laying the basis for the democratization of knowledge.[36] In 1517, Martin Luther incited the Protestant Reformation and his translation of the Bible began the standardization of the language; the 1555 Peace of Augsburg tolerated the «Evangelical» faith (Lutheranism), but also decreed that the faith of the prince was to be the faith of his subjects (cuius regio, eius religio).[37] From the Cologne War through the Thirty Years’ Wars (1618–1648), religious conflict devastated German lands and significantly reduced the population.[38][39]

The Peace of Westphalia ended religious warfare among the Imperial Estates;[38] their mostly German-speaking rulers were able to choose Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism, or the Reformed faith as their official religion.[40] The legal system initiated by a series of Imperial Reforms (approximately 1495–1555) provided for considerable local autonomy and a stronger Imperial Diet.[41] The House of Habsburg held the imperial crown from 1438 until the death of Charles VI in 1740. Following the War of the Austrian Succession and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Charles VI’s daughter Maria Theresa ruled as empress consort when her husband, Francis I, became emperor.[42][43]

From 1740, dualism between the Austrian Habsburg monarchy and the Kingdom of Prussia dominated German history. In 1772, 1793, and 1795, Prussia and Austria, along with the Russian Empire, agreed to the Partitions of Poland.[44][45] During the period of the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic era and the subsequent final meeting of the Imperial Diet, most of the Free Imperial Cities were annexed by dynastic territories; the ecclesiastical territories were secularised and annexed. In 1806 the Imperium was dissolved; France, Russia, Prussia and the Habsburgs (Austria) competed for hegemony in the German states during the Napoleonic Wars.[46]

German Confederation and Empire

Following the fall of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna founded the German Confederation, a loose league of 39 sovereign states. The appointment of the emperor of Austria as the permanent president reflected the Congress’s rejection of Prussia’s rising influence. Disagreement within restoration politics partly led to the rise of liberal movements, followed by new measures of repression by Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich.[47][48] The Zollverein, a tariff union, furthered economic unity.[49] In light of revolutionary movements in Europe, intellectuals and commoners started the revolutions of 1848 in the German states, raising the German question. King Frederick William IV of Prussia was offered the title of emperor, but with a loss of power; he rejected the crown and the proposed constitution, a temporary setback for the movement.[50]

King William I appointed Otto von Bismarck as the minister president of Prussia in 1862. Bismarck successfully concluded the war with Denmark in 1864; the subsequent decisive Prussian victory in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 enabled him to create the North German Confederation which excluded Austria. After the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War, the German princes proclaimed the founding of the German Empire in 1871. Prussia was the dominant constituent state of the new empire; the King of Prussia ruled as its Kaiser, and Berlin became its capital.[51][52]

In the Gründerzeit period following the unification of Germany, Bismarck’s foreign policy as chancellor of Germany secured Germany’s position as a great nation by forging alliances and avoiding war.[52] However, under Wilhelm II, Germany took an imperialistic course, leading to friction with neighbouring countries.[53] A dual alliance was created with the multinational realm of Austria-Hungary; the Triple Alliance of 1882 included Italy. Britain, France and Russia also concluded alliances to protect against Habsburg interference with Russian interests in the Balkans or German interference against France.[54] At the Berlin Conference in 1884, Germany claimed several colonies including German East Africa, German South West Africa, Togoland, and Kamerun.[55] Later, Germany further expanded its colonial empire to include holdings in the Pacific and China.[56] The colonial government in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), from 1904 to 1907, carried out the annihilation of the local Herero and Namaqua peoples as punishment for an uprising;[57][58] this was the 20th century’s first genocide.[58]

The assassination of Austria’s crown prince on 28 June 1914 provided the pretext for Austria-Hungary to attack Serbia and trigger World War I. After four years of warfare, in which approximately two million German soldiers were killed,[59] a general armistice ended the fighting. In the German Revolution (November 1918), Emperor Wilhelm II and the ruling princes abdicated their positions, and Germany was declared a federal republic. Germany’s new leadership signed the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, accepting defeat by the Allies. Germans perceived the treaty as humiliating, which was seen by historians as influential in the rise of Adolf Hitler.[60] Germany lost around 13% of its European territory and ceded all of its colonial possessions in Africa and the Pacific.[61]

Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany

On 11 August 1919, President Friedrich Ebert signed the democratic Weimar Constitution.[62] In the subsequent struggle for power, communists seized power in Bavaria, but conservative elements elsewhere attempted to overthrow the Republic in the Kapp Putsch. Street fighting in the major industrial centres, the occupation of the Ruhr by Belgian and French troops, and a period of hyperinflation followed. A debt restructuring plan and the creation of a new currency in 1924 ushered in the Golden Twenties, an era of artistic innovation and liberal cultural life.[63][64][65]

The worldwide Great Depression hit Germany in 1929. Chancellor Heinrich Brüning’s government pursued a policy of fiscal austerity and deflation which caused unemployment of nearly 30% by 1932.[66] The Nazi Party led by Adolf Hitler became the largest party in the Reichstag after a special election in 1932 and Hindenburg appointed Hitler as chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933.[67] After the Reichstag fire, a decree abrogated basic civil rights and the first Nazi concentration camp opened.[68][69] On 23 March 1933, the Enabling Act gave Hitler unrestricted legislative power, overriding the constitution,[70] and marked the beginning of Nazi Germany. His government established a centralised totalitarian state, withdrew from the League of Nations, and dramatically increased the country’s rearmament.[71] A government-sponsored programme for economic renewal focused on public works, the most famous of which was the Autobahn.[72]

In 1935, the regime withdrew from the Treaty of Versailles and introduced the Nuremberg Laws which targeted Jews and other minorities.[73] Germany also reacquired control of the Saarland in 1935,[74] remilitarised the Rhineland in 1936, annexed Austria in 1938, annexed the Sudetenland in 1938 with the Munich Agreement, and in violation of the agreement occupied Czechoslovakia in March 1939.[75] Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) saw the burning of synagogues, the destruction of Jewish businesses, and mass arrests of Jewish people.[76]

In August 1939, Hitler’s government negotiated the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact that divided Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence.[77] On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, beginning World War II in Europe;[78] Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September.[79] In the spring of 1940, Germany conquered Denmark and Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, forcing the French government to sign an armistice. The British repelled German air attacks in the Battle of Britain in the same year. In 1941, German troops invaded Yugoslavia, Greece and the Soviet Union. By 1942, Germany and its allies controlled most of continental Europe and North Africa, but following the Soviet victory at the Battle of Stalingrad, the Allied reconquest of North Africa and invasion of Italy in 1943, German forces suffered repeated military defeats. In 1944, the Soviets pushed into Eastern Europe; the Western allies landed in France and entered Germany despite a final German counteroffensive. Following Hitler’s suicide during the Battle of Berlin, Germany signed the surrender document on 8 May 1945, ending World War II in Europe[78][80] and Nazi Germany. Following the end of the war, surviving Nazi officials were tried for war crimes at the Nuremberg trials.[81][82]

In what later became known as the Holocaust, the German government persecuted minorities, including interning them in concentration and death camps across Europe. In total 17 million people were systematically murdered, including 6 million Jews, at least 130,000 Romani, 275,000 disabled people, thousands of Jehovah’s Witnesses, thousands of homosexuals, and hundreds of thousands of political and religious opponents.[83] Nazi policies in German-occupied countries resulted in the deaths of an estimated 2.7 million Poles,[84] 1.3 million Ukrainians, 1 million Belarusians and 3.5 million Soviet prisoners of war.[85][81] German military casualties have been estimated at 5.3 million,[86] and around 900,000 German civilians died.[87] Around 12 million ethnic Germans were expelled from across Eastern Europe, and Germany lost roughly one-quarter of its pre-war territory.[88]

East and West Germany

After Nazi Germany surrendered, the Allies partitioned Berlin and Germany’s remaining territory into four occupation zones. The western sectors, controlled by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, were merged on 23 May 1949 to form the Federal Republic of Germany (German: Bundesrepublik Deutschland); on 7 October 1949, the Soviet Zone became the German Democratic Republic (GDR) (German: Deutsche Demokratische Republik; DDR). They were informally known as West Germany and East Germany.[90] East Germany selected East Berlin as its capital, while West Germany chose Bonn as a provisional capital, to emphasise its stance that the two-state solution was temporary.[91]

West Germany was established as a federal parliamentary republic with a «social market economy». Starting in 1948 West Germany became a major recipient of reconstruction aid under the American Marshall Plan.[92] Konrad Adenauer was elected the first federal chancellor of Germany in 1949. The country enjoyed prolonged economic growth (Wirtschaftswunder) beginning in the early 1950s.[93] West Germany joined NATO in 1955 and was a founding member of the European Economic Community.[94]

East Germany was an Eastern Bloc state under political and military control by the Soviet Union via occupation forces and the Warsaw Pact. Although East Germany claimed to be a democracy, political power was exercised solely by leading members (Politbüro) of the communist-controlled Socialist Unity Party of Germany, supported by the Stasi, an immense secret service.[95] While East German propaganda was based on the benefits of the GDR’s social programmes and the alleged threat of a West German invasion, many of its citizens looked to the West for freedom and prosperity.[96] The Berlin Wall, built in 1961, prevented East German citizens from escaping to West Germany, becoming a symbol of the Cold War.[97]

Tensions between East and West Germany were reduced in the late 1960s by Chancellor Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik.[98] In 1989, Hungary decided to dismantle the Iron Curtain and open its border with Austria, causing the emigration of thousands of East Germans to West Germany via Hungary and Austria. This had devastating effects on the GDR, where regular mass demonstrations received increasing support. In an effort to help retain East Germany as a state, the East German authorities eased border restrictions, but this actually led to an acceleration of the Wende reform process culminating in the Two Plus Four Treaty under which Germany regained full sovereignty. This permitted German reunification on 3 October 1990, with the accession of the five re-established states of the former GDR.[99] The fall of the Wall in 1989 became a symbol of the Fall of Communism, the Dissolution of the Soviet Union, German reunification and Die Wende.[100]

Reunified Germany and the European Union

United Germany was considered the enlarged continuation of West Germany so it retained its memberships in international organisations.[101] Based on the Berlin/Bonn Act (1994), Berlin again became the capital of Germany, while Bonn obtained the unique status of a Bundesstadt (federal city) retaining some federal ministries.[102] The relocation of the government was completed in 1999, and modernisation of the East German economy was scheduled to last until 2019.[103][104]

Since reunification, Germany has taken a more active role in the European Union, signing the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and the Lisbon Treaty in 2007,[105] and co-founding the Eurozone.[106] Germany sent a peacekeeping force to secure stability in the Balkans and sent German troops to Afghanistan as part of a NATO effort to provide security in that country after the ousting of the Taliban.[107][108]

In the 2005 elections, Angela Merkel became the first female chancellor. In 2009 the German government approved a €50 billion stimulus plan.[109] Among the major German political projects of the early 21st century are the advancement of European integration, the energy transition (Energiewende) for a sustainable energy supply, the debt brake for balanced budgets, measures to increase the fertility rate (pronatalism), and high-tech strategies for the transition of the German economy, summarised as Industry 4.0.[110] During the 2015 European migrant crisis, the country took in over a million refugees and migrants.[111]

Geography

Germany is the seventh-largest country in Europe;[4] bordering Denmark to the north, Poland and the Czech Republic to the east, Austria to the southeast, and Switzerland to the south-southwest. France, Luxembourg and Belgium are situated to the west, with the Netherlands to the northwest. Germany is also bordered by the North Sea and, at the north-northeast, by the Baltic Sea. German territory covers 357,022 km2 (137,847 sq mi), consisting of 348,672 km2 (134,623 sq mi) of land and 8,350 km2 (3,224 sq mi) of water.

Elevation ranges from the mountains of the Alps (highest point: the Zugspitze at 2,963 metres or 9,721 feet) in the south to the shores of the North Sea (Nordsee) in the northwest and the Baltic Sea (Ostsee) in the northeast. The forested uplands of central Germany and the lowlands of northern Germany (lowest point: in the municipality Neuendorf-Sachsenbande, Wilstermarsch at 3.54 metres or 11.6 feet below sea level[112]) are traversed by such major rivers as the Rhine, Danube and Elbe. Significant natural resources include iron ore, coal, potash, timber, lignite, uranium, copper, natural gas, salt, and nickel.[4]

Climate

Most of Germany has a temperate climate, ranging from oceanic in the north and west to continental in the east and southeast. Winters range from the cold in the Southern Alps to cool and are generally overcast with limited precipitation, while summers can vary from hot and dry to cool and rainy. The northern regions have prevailing westerly winds that bring in moist air from the North Sea, moderating the temperature and increasing precipitation. Conversely, the southeast regions have more extreme temperatures.[113]

From February 2019 – 2020, average monthly temperatures in Germany ranged from a low of 3.3 °C (37.9 °F) in January 2020 to a high of 19.8 °C (67.6 °F) in June 2019.[114] Average monthly precipitation ranged from 30 litres per square metre in February and April 2019 to 125 litres per square metre in February 2020.[115] Average monthly hours of sunshine ranged from 45 in November 2019 to 300 in June 2019.[116]

Biodiversity

The territory of Germany can be divided into five terrestrial ecoregions: Atlantic mixed forests, Baltic mixed forests, Central European mixed forests, Western European broadleaf forests, and Alps conifer and mixed forests.[117] As of 2016 51% of Germany’s land area is devoted to agriculture, while 30% is forested and 14% is covered by settlements or infrastructure.[118]

Plants and animals include those generally common to Central Europe. According to the National Forest Inventory, beeches, oaks, and other deciduous trees constitute just over 40% of the forests; roughly 60% are conifers, particularly spruce and pine.[119] There are many species of ferns, flowers, fungi, and mosses. Wild animals include roe deer, wild boar, mouflon (a subspecies of wild sheep), fox, badger, hare, and small numbers of the Eurasian beaver.[120] The blue cornflower was once a German national symbol.[121]

The 16 national parks in Germany include the Jasmund National Park, the Vorpommern Lagoon Area National Park, the Müritz National Park, the Wadden Sea National Parks, the Harz National Park, the Hainich National Park, the Black Forest National Park, the Saxon Switzerland National Park, the Bavarian Forest National Park and the Berchtesgaden National Park.[122] In addition, there are 17 Biosphere Reserves,[123] and 105 nature parks.[124] More than 400 zoos and animal parks operate in Germany.[125] The Berlin Zoo, which opened in 1844, is the oldest in Germany, and claims the most comprehensive collection of species in the world.[126]

Politics

Germany is a federal, parliamentary, representative democratic republic. Federal legislative power is vested in the parliament consisting of the Bundestag (Federal Diet) and Bundesrat (Federal Council), which together form the legislative body. The Bundestag is elected through direct elections using the mixed-member proportional representation system. The members of the Bundesrat represent and are appointed by the governments of the sixteen federated states.[4] The German political system operates under a framework laid out in the 1949 constitution known as the Grundgesetz (Basic Law). Amendments generally require a two-thirds majority of both the Bundestag and the Bundesrat; the fundamental principles of the constitution, as expressed in the articles guaranteeing human dignity, the separation of powers, the federal structure, and the rule of law, are valid in perpetuity.[127]

The president, currently Frank-Walter Steinmeier, is the head of state and invested primarily with representative responsibilities and powers. He is elected by the Bundesversammlung (federal convention), an institution consisting of the members of the Bundestag and an equal number of state delegates.[4] The second-highest official in the German order of precedence is the Bundestagspräsident (President of the Bundestag), who is elected by the Bundestag and responsible for overseeing the daily sessions of the body.[128] The third-highest official and the head of government is the chancellor, who is appointed by the Bundespräsident after being elected by the party or coalition with the most seats in the Bundestag.[4] The chancellor, currently Olaf Scholz, is the head of government and exercises executive power through his Cabinet.[4]

Since 1949, the party system has been dominated by the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party of Germany. So far every chancellor has been a member of one of these parties. However, the smaller liberal Free Democratic Party and the Alliance 90/The Greens have also been junior partners in coalition governments. Since 2007, the democratic socialist party The Left has been a staple in the German Bundestag, though they have never been part of the federal government. In the 2017 German federal election, the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany gained enough votes to attain representation in the parliament for the first time.[129][130]

Constituent states

Germany is a federation and comprises sixteen constituent states which are collectively referred to as Länder.[131] Each state (Land) has its own constitution,[132] and is largely autonomous in regard to its internal organisation.[131] As of 2017 Germany is divided into 401 districts (Kreise) at a municipal level; these consist of 294 rural districts and 107 urban districts.[133]

| State | Capital | Area (km2)[134] | Population (2018)[135] | Nominal GDP billions EUR (2015)[136] | Nominal GDP per capita EUR (2015)[136] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | Stuttgart | 35,751 | 11,069,533 | 461 | 42,800 |

| Bavaria | Munich | 70,550 | 13,076,721 | 550 | 43,100 |

| Berlin | Berlin | 892 | 3,644,826 | 125 | 35,700 |

| Brandenburg | Potsdam | 29,654 | 2,511,917 | 66 | 26,500 |

| Bremen | Bremen | 420 | 682,986 | 32 | 47,600 |

| Hamburg | Hamburg | 755 | 1,841,179 | 110 | 61,800 |

| Hesse | Wiesbaden | 21,115 | 6,265,809 | 264 | 43,100 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | Schwerin | 23,214 | 1,609,675 | 40 | 25,000 |

| Lower Saxony | Hanover | 47,593 | 7,982,448 | 259 | 32,900 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | Düsseldorf | 34,113 | 17,932,651 | 646 | 36,500 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | Mainz | 19,854 | 4,084,844 | 132 | 32,800 |

| Saarland | Saarbrücken | 2,569 | 990,509 | 35 | 35,400 |

| Saxony | Dresden | 18,416 | 4,077,937 | 113 | 27,800 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | Magdeburg | 20,452 | 2,208,321 | 57 | 25,200 |

| Schleswig-Holstein | Kiel | 15,802 | 2,896,712 | 86 | 31,200 |

| Thuringia | Erfurt | 16,202 | 2,143,145 | 57 | 26,400 |

| Germany | Berlin | 357,386 | 83,019,213 | 3025 | 37,100 |

Law

Germany has a civil law system based on Roman law with some references to Germanic law.[137] The Bundesverfassungsgericht (Federal Constitutional Court) is the German Supreme Court responsible for constitutional matters, with power of judicial review.[138] Germany’s supreme court system is specialised: for civil and criminal cases, the highest court of appeal is the inquisitorial Federal Court of Justice, and for other affairs the courts are the Federal Labour Court, the Federal Social Court, the Federal Fiscal Court and the Federal Administrative Court.[139]

Criminal and private laws are codified on the national level in the Strafgesetzbuch and the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch respectively. The German penal system seeks the rehabilitation of the criminal and the protection of the public.[140] Except for petty crimes, which are tried before a single professional judge, and serious political crimes, all charges are tried before mixed tribunals on which lay judges (Schöffen) sit side by side with professional judges.[141][142]

Germany has a low murder rate with 1.18 murders per 100,000 as of 2016.[143] In 2018, the overall crime rate fell to its lowest since 1992.[144]

Foreign relations

Germany has a network of 227 diplomatic missions abroad[145] and maintains relations with more than 190 countries.[146] Germany is a member of NATO, the OECD, the G7, the G20, the World Bank and the IMF. It has played an influential role in the European Union since its inception and has maintained a strong alliance with France and all neighbouring countries since 1990. Germany promotes the creation of a more unified European political, economic and security apparatus.[147][148][149] The governments of Germany and the United States are close political allies.[150] Cultural ties and economic interests have crafted a bond between the two countries resulting in Atlanticism.[151] After 1990, Germany and Russia worked together to establish a «strategic partnership» in which energy development became one of the most important factors. As a result of the cooperation, Germany imported most of its natural gas and crude oil from Russia.[152][153]

The development policy of Germany is an independent area of foreign policy. It is formulated by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and carried out by the implementing organisations. The German government sees development policy as a joint responsibility of the international community.[154] It was the world’s second-biggest aid donor in 2019 after the United States.[155]

Military

Germany’s military, the Bundeswehr (Federal Defence), is organised into the Heer (Army and special forces KSK), Marine (Navy), Luftwaffe (Air Force), Zentraler Sanitätsdienst der Bundeswehr (Joint Medical Service), Streitkräftebasis (Joint Support Service) and Cyber- und Informationsraum (Cyber and Information Domain Service) branches. In absolute terms, German military expenditure is the eighth-highest in the world.[156] In 2018, military spending was at $49.5 billion, about 1.2% of the country’s GDP, well below the NATO target of 2%.[157][158] However, in response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced that German military expenditure would be increased past the NATO target of 2%, along with a one-time 2022 infusion of 100 billion euros, representing almost double the 53 billion euro military budget for 2021.[159][160]

As of January 2020, the Bundeswehr has a strength of 184,001 active soldiers and 80,947 civilians.[161] Reservists are available to the armed forces and participate in defence exercises and deployments abroad.[162] Until 2011, military service was compulsory for men at age 18, but this has been officially suspended and replaced with a voluntary service.[163][164] Since 2001 women may serve in all functions of service without restriction.[165] According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Germany was the fourth-largest exporter of major arms in the world from 2014 to 2018.[166]

In peacetime, the Bundeswehr is commanded by the Minister of Defence. In state of defence, the Chancellor would become commander-in-chief of the Bundeswehr.[167] The role of the Bundeswehr is described in the Constitution of Germany as defensive only. But after a ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court in 1994, the term «defence» has been defined to not only include protection of the borders of Germany, but also crisis reaction and conflict prevention, or more broadly as guarding the security of Germany anywhere in the world. As of 2017, the German military has about 3,600 troops stationed in foreign countries as part of international peacekeeping forces, including about 1,200 supporting operations against Daesh, 980 in the NATO-led Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan, and 800 in Kosovo.[168][169]

Economy

Germany has a social market economy with a highly skilled labour force, a low level of corruption, and a high level of innovation.[4][171][172] It is the world’s third-largest exporter and third-largest importer,[4] and has the largest economy in Europe, which is also the world’s fourth-largest economy by nominal GDP,[173] and the fifth-largest by PPP.[174] Its GDP per capita measured in purchasing power standards amounts to 121% of the EU27 average (100%).[175] The service sector contributes approximately 69% of the total GDP, industry 31%, and agriculture 1% as of 2017.[4] The unemployment rate published by Eurostat amounts to 3.2% as of January 2020, which is the fourth-lowest in the EU.[176]

Germany is part of the European single market which represents more than 450 million consumers.[177] In 2017, the country accounted for 28% of the Eurozone economy according to the International Monetary Fund.[178] Germany introduced the common European currency, the euro, in 2002.[179] Its monetary policy is set by the European Central Bank, which is headquartered in Frankfurt.[180][170]

Being home to the modern car, the automotive industry in Germany is regarded as one of the most competitive and innovative in the world,[181] and is the sixth-largest by production as of 2021. The top ten exports of Germany are vehicles, machinery, chemical goods, electronic products, electrical equipments, pharmaceuticals, transport equipments, basic metals, food products, and rubber and plastics.[182]

Of the world’s 500 largest stock-market-listed companies measured by revenue in 2019, the Fortune Global 500, 29 are headquartered in Germany.[183] 30 major Germany-based companies are included in the DAX, the German stock market index which is operated by Frankfurt Stock Exchange.[184] Well-known international brands include Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volkswagen, Audi, Siemens, Allianz, Adidas, Porsche, Bosch and Deutsche Telekom.[185] Berlin is a hub for startup companies and has become the leading location for venture capital funded firms in the European Union.[186] Germany is recognised for its large portion of specialised small and medium enterprises, known as the Mittelstand model.[187] These companies represent 48% global market leaders in their segments, labelled hidden champions.[188]

Research and development efforts form an integral part of the German economy.[189] In 2018 Germany ranked fourth globally in terms of number of science and engineering research papers published.[190] Research institutions in Germany include the Max Planck Society, the Helmholtz Association, and the Fraunhofer Society and the Leibniz Association.[191] Germany is the largest contributor to the European Space Agency.[192]

Infrastructure

With its central position in Europe, Germany is a transport hub for the continent.[193] Its road network is among the densest in Europe.[194] The motorway (Autobahn) is widely known for having no general federally mandated speed limit for some classes of vehicles.[195] The Intercity Express or ICE train network serves major German cities as well as destinations in neighbouring countries with speeds up to 300 km/h (190 mph).[196] The largest German airports are Frankfurt Airport and Munich Airport.[197] The Port of Hamburg is one of the top twenty largest container ports in the world.[198]

In 2015, Germany was the world’s seventh-largest consumer of energy.[199] The government and the nuclear power industry agreed to phase out all nuclear power plants by 2021.[200] It meets the country’s power demands using 40% renewable sources, and it has been called an «early leader» in solar and offshore wind.[201][202] Germany is committed to the Paris Agreement and several other treaties promoting biodiversity, low emission standards, and water management.[203][204][205] The country’s household recycling rate is among the highest in the world—at around 65%.[206] The country’s greenhouse gas emissions per capita were the ninth-highest in the EU in 2018, but these numbers have been trending downward.[207][208] The German energy transition (Energiewende) is the recognised move to a sustainable economy by means of energy efficiency and renewable energy.[209][202]

Tourism

Germany is the ninth-most visited country in the world as of 2017, with 37.4 million visits.[210] Domestic and international travel and tourism combined directly contribute over €105.3 billion to German GDP. Including indirect and induced impacts, the industry supports 4.2 million jobs.[211]

Germany’s most visited and popular landmarks include Cologne Cathedral, the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, the Dresden Frauenkirche, Neuschwanstein Castle, Heidelberg Castle, the Wartburg, and Sanssouci Palace.[212] The Europa-Park near Freiburg is Europe’s second-most popular theme park resort.[213]

Demographics

With a population of 80.2 million according to the 2011 German Census,[214] rising to 83.7 million as of 2022,[215] Germany is the most populous country in the European Union, the second-most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the nineteenth-most populous country in the world. Its population density stands at 227 inhabitants per square kilometre (588 per square mile). The fertility rate of 1.57 children born per woman (2022 estimates) is below the replacement rate of 2.1 and is one of the lowest fertility rates in the world.[4] Since the 1970s, Germany’s death rate has exceeded its birth rate. However, Germany is witnessing increased birth rates and migration rates since the beginning of the 2010s. Germany has the third oldest population in the world, with an average age of 47.4 years.[4]

Four sizeable groups of people are referred to as «national minorities» because their ancestors have lived in their respective regions for centuries:[216] There is a Danish minority in the northernmost state of Schleswig-Holstein;[216] the Sorbs, a Slavic population, are in the Lusatia region of Saxony and Brandenburg; the Roma and Sinti live throughout the country; and the Frisians are concentrated in Schleswig-Holstein’s western coast and in the north-western part of Lower Saxony.[216]

After the United States, Germany is the second-most popular immigration destination in the world. The majority of migrants live in western Germany, in particular in urban areas. Of the country’s residents, 18.6 million people (22.5%) were of immigrant or partially immigrant descent in 2016 (including persons descending or partially descending from ethnic German repatriates).[217] In 2015, the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs listed Germany as host to the second-highest number of international migrants worldwide, about 5% or 12 million of all 244 million migrants.[218] As of 2019, Germany ranks seventh amongst EU countries in terms of the percentage of migrants in the country’s population, at 13.1%.[219]

Germany has a number of large cities. There are 11 officially recognised metropolitan regions. The country’s largest city is Berlin, while its largest urban area is the Ruhr.[220]

Largest cities or towns in Germany Statistical offices in Germany (31 December 2018) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||

Berlin  Hamburg |

1 | Berlin | Berlin | 3,644,826 | 11 | Bremen | Bremen | 569,352 |  Munich  Cologne |

| 2 | Hamburg | Hamburg | 1,841,179 | 12 | Dresden | Saxony | 554,649 | ||

| 3 | Munich | Bavaria | 1,471,508 | 13 | Hanover | Lower Saxony | 538,068 | ||

| 4 | Cologne | North Rhine-Westphalia | 1,085,664 | 14 | Nuremberg | Bavaria | 518,365 | ||

| 5 | Frankfurt | Hesse | 753,056 | 15 | Duisburg | North Rhine-Westphalia | 498,590 | ||

| 6 | Stuttgart | Baden-Württemberg | 634,830 | 16 | Bochum | North Rhine-Westphalia | 364,628 | ||

| 7 | Düsseldorf | North Rhine-Westphalia | 619,294 | 17 | Wuppertal | North Rhine-Westphalia | 354,382 | ||

| 8 | Leipzig | Saxony | 587,857 | 18 | Bielefeld | North Rhine-Westphalia | 333,786 | ||

| 9 | Dortmund | North Rhine-Westphalia | 587,010 | 19 | Bonn | North Rhine-Westphalia | 327,258 | ||

| 10 | Essen | North Rhine-Westphalia | 583,109 | 20 | Münster | North Rhine-Westphalia | 314,319 |

Religion

Christianity was introduced to the area of modern Germany by 300 AD and became fully Christianized by the time of Charlemagne in the eighth and ninth century. After the Reformation started by Martin Luther in the early 16th century, many people left the Catholic Church and became Protestant, mainly Lutheran and Calvinist.[221]

According to the 2011 census, Christianity was the largest religion in Germany, with 66.8% of respondents identifying as Christian, of which 3.8% were not church members.[222] 31.7% declared themselves as Protestants, including members of the Evangelical Church in Germany (which encompasses Lutheran, Reformed, and administrative or confessional unions of both traditions) and the free churches (Evangelische Freikirchen); 31.2% declared themselves as Roman Catholics, and Orthodox believers constituted 1.3%. According to data from 2016, the Catholic Church and the Evangelical Church claimed 28.5% and 27.5%, respectively, of the population.[223][224] Islam is the second-largest religion in the country.[225]

In the 2011 census, 1.9% of respondents (1.52 million people) gave their religion as Islam, but this figure is deemed unreliable because a disproportionate number of adherents of this faith (and other religions, such as Judaism) are likely to have made use of their right not to answer the question.[226] Most of the Muslims are Sunnis and Alevites from Turkey, but there are a small number of Shi’ites, Ahmadiyyas and other denominations. Other religions comprise less than one percent of Germany’s population.[225]

A study in 2018 estimated that 38% of the population are not members of any religious organization or denomination,[227] though up to a third may still consider themselves religious. Irreligion in Germany is strongest in the former East Germany, which used to be predominantly Protestant before the enforcement of state atheism, and in major metropolitan areas.[228][229]

Languages

German is the official and predominant spoken language in Germany.[230] It is one of 24 official and working languages of the European Union, and one of the three procedural languages of the European Commission.[231] German is the most widely spoken first language in the European Union, with around 100 million native speakers.[232]

Recognised native minority languages in Germany are Danish, Low German, Low Rhenish, Sorbian, Romani, North Frisian and Saterland Frisian; they are officially protected by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. The most used immigrant languages are Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, Polish, Greek, Serbo-Croatian, Bulgarian and other Balkan languages, as well as Russian. Germans are typically multilingual: 67% of German citizens claim to be able to communicate in at least one foreign language and 27% in at least two.[230]

Education

Heidelberg University is Germany’s oldest institution of higher learning and generally counted among its most renowned.

Responsibility for educational supervision in Germany is primarily organised within the individual states. Optional kindergarten education is provided for all children between three and six years old, after which school attendance is compulsory for at least nine years depending on the state. Primary education usually lasts for four to six years.[233] Secondary schooling is divided into tracks based on whether students pursue academic or vocational education.[234] A system of apprenticeship called Duale Ausbildung leads to a skilled qualification which is almost comparable to an academic degree. It allows students in vocational training to learn in a company as well as in a state-run trade school.[233] This model is well regarded and reproduced all around the world.[235]

Most of the German universities are public institutions, and students traditionally study without fee payment.[236] The general requirement for attending university is the Abitur. According to an OECD report in 2014, Germany is the world’s third leading destination for international study.[237] The established universities in Germany include some of the oldest in the world, with Heidelberg University (established in 1386) being the oldest.[238] The Humboldt University of Berlin, founded in 1810 by the liberal educational reformer Wilhelm von Humboldt, became the academic model for many Western universities.[239][240] In the contemporary era Germany has developed eleven Universities of Excellence.

Health

The Hospital of the Holy Spirit in Lübeck, established in 1286, is a precursor to modern hospitals.[241]

Germany’s system of hospitals, called Krankenhäuser, dates from medieval times, and today, Germany has the world’s oldest universal health care system, dating from Bismarck’s social legislation of the 1880s.[242] Since the 1880s, reforms and provisions have ensured a balanced health care system. The population is covered by a health insurance plan provided by statute, with criteria allowing some groups to opt for a private health insurance contract. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Germany’s health care system was 77% government-funded and 23% privately funded as of 2013.[243] In 2014, Germany spent 11.3% of its GDP on health care.[244]

Germany ranked 21st in the world in 2019 in life expectancy with 78.7 years for men and 84.8 years for women according to the WHO, and it had a very low infant mortality rate (4 per 1,000 live births). In 2019, the principal cause of death was cardiovascular disease, at 37%.[245] Obesity in Germany has been increasingly cited as a major health issue. A 2014 study showed that 52 percent of the adult German population was overweight or obese.[246]

Culture

Culture in German states has been shaped by major intellectual and popular currents in Europe, both religious and secular. Historically, Germany has been called Das Land der Dichter und Denker (‘the land of poets and thinkers’),[247] because of the major role its scientists, writers and philosophers have played in the development of Western thought.[248] A global opinion poll for the BBC revealed that Germany is recognised for having the most positive influence in the world in 2013 and 2014.[249][250]

Germany is well known for such folk festival traditions as the Oktoberfest and Christmas customs, which include Advent wreaths, Christmas pageants, Christmas trees, Stollen cakes, and other practices.[251][252] As of 2016 UNESCO inscribed 41 properties in Germany on the World Heritage List.[253] There are a number of public holidays in Germany determined by each state; 3 October has been a national day of Germany since 1990, celebrated as the Tag der Deutschen Einheit (German Unity Day).[254]

Music

German classical music includes works by some of the world’s most well-known composers. Dieterich Buxtehude, Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Händel were influential composers of the Baroque period. Ludwig van Beethoven was a crucial figure in the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras. Carl Maria von Weber, Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms were significant Romantic composers. Richard Wagner was known for his operas. Richard Strauss was a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. Karlheinz Stockhausen and Wolfgang Rihm are important composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries.[255]

As of 2013, Germany was the second-largest music market in Europe, and fourth-largest in the world.[256] German popular music of the 20th and 21st centuries includes the movements of Neue Deutsche Welle, pop, Ostrock, heavy metal/rock, punk, pop rock, indie, Volksmusik (folk music), schlager pop and German hip hop. German electronic music gained global influence, with Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream pioneering in this genre.[257] DJs and artists of the techno and house music scenes of Germany have become well known (e.g. Paul van Dyk, Felix Jaehn, Paul Kalkbrenner, Robin Schulz and Scooter).[258]

Art, design and architecture

German painters have influenced Western art. Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Younger, Matthias Grünewald and Lucas Cranach the Elder were important German artists of the Renaissance, Johann Baptist Zimmermann of the Baroque, Caspar David Friedrich and Carl Spitzweg of Romanticism, Max Liebermann of Impressionism and Max Ernst of Surrealism. Several German art groups formed in the 20th century; Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) influenced the development of expressionism in Munich and Berlin. The New Objectivity arose in response to expressionism during the Weimar Republic. After World War II, broad trends in German art include neo-expressionism and the New Leipzig School.[259]

German designers became early leaders of modern product design.[260] The Berlin Fashion Week and the fashion trade fair Bread & Butter are held twice a year.[261]

Architectural contributions from Germany include the Carolingian and Ottonian styles, which were precursors of Romanesque. Brick Gothic is a distinctive medieval style that evolved in Germany. Also in Renaissance and Baroque art, regional and typically German elements evolved (e.g. Weser Renaissance).[259] Vernacular architecture in Germany is often identified by its timber framing (Fachwerk) traditions and varies across regions, and among carpentry styles.[262] When industrialisation spread across Europe, classicism and a distinctive style of historicism developed in Germany, sometimes referred to as Gründerzeit style. Expressionist architecture developed in the 1910s in Germany and influenced Art Deco and other modern styles. Germany was particularly important in the early modernist movement: it is the home of Werkbund initiated by Hermann Muthesius (New Objectivity), and of the Bauhaus movement founded by Walter Gropius.[259] Ludwig Mies van der Rohe became one of the world’s most renowned architects in the second half of the 20th century; he conceived of the glass façade skyscraper.[263] Renowned contemporary architects and offices include Pritzker Prize winners Gottfried Böhm and Frei Otto.[264]

Literature and philosophy

German literature can be traced back to the Middle Ages and the works of writers such as Walther von der Vogelweide and Wolfram von Eschenbach. Well-known German authors include Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Theodor Fontane. The collections of folk tales published by the Brothers Grimm popularised German folklore on an international level.[265] The Grimms also gathered and codified regional variants of the German language, grounding their work in historical principles; their Deutsches Wörterbuch, or German Dictionary, sometimes called the Grimm dictionary, was begun in 1838 and the first volumes published in 1854.[266]

Influential authors of the 20th century include Gerhart Hauptmann, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass.[267] The German book market is the third-largest in the world, after the United States and China.[268] The Frankfurt Book Fair is the most important in the world for international deals and trading, with a tradition spanning over 500 years.[269] The Leipzig Book Fair also retains a major position in Europe.[270]

German philosophy is historically significant: Gottfried Leibniz’s contributions to rationalism; the enlightenment philosophy by Immanuel Kant; the establishment of classical German idealism by Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling; Arthur Schopenhauer’s composition of metaphysical pessimism; the formulation of communist theory by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels; Friedrich Nietzsche’s development of perspectivism; Gottlob Frege’s contributions to the dawn of analytic philosophy; Martin Heidegger’s works on Being; Oswald Spengler’s historical philosophy; the development of the Frankfurt School has been particularly influential.[271]

Media

The largest internationally operating media companies in Germany are the Bertelsmann enterprise, Axel Springer SE and ProSiebenSat.1 Media. Germany’s television market is the largest in Europe, with some 38 million TV households.[272] Around 90% of German households have cable or satellite TV, with a variety of free-to-view public and commercial channels.[273] There are more than 300 public and private radio stations in Germany; Germany’s national radio network is the Deutschlandradio and the public Deutsche Welle is the main German radio and television broadcaster in foreign languages.[273] Germany’s print market of newspapers and magazines is the largest in Europe.[273] The papers with the highest circulation are Bild, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Die Welt.[273] The largest magazines include ADAC Motorwelt and Der Spiegel.[273] Germany has a large video gaming market, with over 34 million players nationwide.[274]

German cinema has made major technical and artistic contributions to film. The first works of the Skladanowsky Brothers were shown to an audience in 1895. The renowned Babelsberg Studio in Potsdam was established in 1912, thus being the first large-scale film studio in the world. Early German cinema was particularly influential with German expressionists such as Robert Wiene and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. Director Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is referred to as the first major science-fiction film. After 1945, many of the films of the immediate post-war period can be characterised as Trümmerfilm (rubble film). East German film was dominated by state-owned film studio DEFA, while the dominant genre in West Germany was the Heimatfilm («homeland film»).[275] During the 1970s and 1980s, New German Cinema directors such as Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder brought West German auteur cinema to critical acclaim.

The Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film («Oscar») went to the German production The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel) in 1979, to Nowhere in Africa (Nirgendwo in Afrika) in 2002, and to The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen) in 2007. Various Germans won an Oscar for their performances in other films. The annual European Film Awards ceremony is held every other year in Berlin, home of the European Film Academy. The Berlin International Film Festival, known as «Berlinale», awarding the «Golden Bear» and held annually since 1951, is one of the world’s leading film festivals. The «Lolas» are annually awarded in Berlin, at the German Film Awards.[276]

Cuisine

German cuisine varies from region to region and often neighbouring regions share some culinary similarities (e.g. the southern regions of Bavaria and Swabia share some traditions with Switzerland and Austria). International varieties such as pizza, sushi, Chinese food, Greek food, Indian cuisine and doner kebab are also popular.

Bread is a significant part of German cuisine and German bakeries produce about 600 main types of bread and 1,200 types of pastries and rolls (Brötchen).[277] German cheeses account for about 22% of all cheese produced in Europe.[278] In 2012 over 99% of all meat produced in Germany was either pork, chicken or beef. Germans produce their ubiquitous sausages in almost 1,500 varieties, including Bratwursts and Weisswursts.[279] The national alcoholic drink is beer.[280] German beer consumption per person stands at 110 litres (24 imp gal; 29 US gal) in 2013 and remains among the highest in the world.[281] German beer purity regulations date back to the 16th century.[282] Wine has become popular in many parts of the country, especially close to German wine regions.[283] In 2019, Germany was the ninth-largest wine producer in the world.[284]

The 2018 Michelin Guide awarded eleven restaurants in Germany three stars, giving the country a cumulative total of 300 stars.[285]

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Germany. With more than 7 million official members, the German Football Association (Deutscher Fußball-Bund) is the largest single-sport organisation worldwide,[286] and the German top league, the Bundesliga, attracts the second-highest average attendance of all professional sports leagues in the world.[287] The German men’s national football team won the FIFA World Cup in 1954, 1974, 1990, and 2014,[288] the UEFA European Championship in 1972, 1980 and 1996,[289] and the FIFA Confederations Cup in 2017.[290]

Germany is one of the leading motor sports countries in the world. Constructors like BMW and Mercedes are prominent manufacturers in motor sport. Porsche has won the 24 Hours of Le Mans race 19 times, and Audi 13 times (as of 2017).[291] The driver Michael Schumacher has set many motor sport records during his career, having won seven Formula One World Drivers’ Championships.[292] Sebastian Vettel is also among the most successful Formula One drivers of all time.[293]

Historically, German athletes have been successful contenders in the Olympic Games, ranking third in an all-time Olympic Games medal count (when combining East and West German medals).[294] In 1936 Berlin hosted the Summer Games and the Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Munich hosted the Summer Games of 1972.[295][296]

See also

- Index of Germany-related articles

- Outline of Germany

Notes

- ^ From 1952 to 1990, the entire «Deutschlandlied» was the national anthem, but only the third verse was sung on official occasions. Since 1991, the third verse alone has been the national anthem.[1]

- ^ Berlin is the sole constitutional capital and de jure seat of government, but the former provisional capital of the Federal Republic of Germany, Bonn, has the special title of «federal city» (Bundesstadt) and is the primary seat of six ministries.[2]

- ^ Danish, Low German, Sorbian, Romani, and Frisian are recognised by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[3]